- 1Cellular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 2Department of Botany, San Diego Natural History Museum, San Diego, CA, United States

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease involve regulated forms of cell death, including oxytosis/ferroptosis, which are driven by oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Targeting these regulated cell death pathways offers novel therapeutic opportunities. Wyethia is a small genus of flowering plants native to North America, traditionally used by Indigenous populations for medicinal purposes. Its ethnobotanical relevance and phytochemical diversity prompted investigation into its neuroprotective potential. This study examined eight Wyethia species for anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities. We evaluated protection against oxytosis/ferroptosis (induced by glutamate, erastin, and RSL3) in HT22 neuronal cells, energy loss using an ischemia assay in HT22 cells, and LPS-induced inflammation in BV2 microglial cells. W. ovata, W. helenioides, W. amplexicaulis and W. glabra exhibited strong neuroprotection (EC50 < 25 μg/mL), with W. ovata also demonstrating potent anti-inflammatory activity (EC50 = 15.2 μg/mL). Antioxidant assays (DPPH, lipid peroxidation) and measurement of total phenolic content (TPC) analysis revealed a correlation between high phenolic content and antioxidant activity, with W. ovata and W. amplexicaulis showing the highest TPC values (120–140 mg GAE/g). However, W. invenusta displayed strong neuroprotective effects despite low TPC, suggesting that other bioactive compounds such as terpenoids, or alkaloids may contribute to its activity. This highlights the complexity of phytochemical profiles and the potential presence of potent constituents beyond phenolics. These findings position Wyethia as a promising source of dual-action neuroprotective agents that target both oxytosis/ferroptosis and inflammation, warranting further phytochemical investigation.

1 Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are characterized by progressive neuronal loss, leading to cognitive and motor impairments (Moya-Alvarado et al., 2016). An increasing number of studies indicate that iron-dependent oxidative cell death pathways, particularly oxytosis/ferroptosis, play a significant role in driving neurodegeneration in AD (Zhao et al., 2023; Zeng and Jin, 2025; Currais et al., 2025). These pathways are distinguished by mitochondrial dysfunction, lipid peroxidation (LPO) and glutathione (GSH) depletion, which together amplify neuroinflammation and synaptic toxicity (Tönnies and Trushina, 2017; Misrani et al., 2021).

In AD, dysregulated iron metabolism and impaired cystine/glutamate antiporter (xc−) activity exacerbate GSH depletion, rendering neurons vulnerable to oxytotic/ferroptotic death through uncontrolled lipid peroxidation (Soriano-Castell et al., 2021a; Sutanto et al., 2025). This vulnerability is compounded by overproduction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), which not only damages cellular components but also promotes amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation, thereby perpetuating a vicious cycle of oxidative damage and neuroinflammation (Wang et al., 2023; Alkhalifa et al., 2025). Oxytosis/ferroptosis represents a form of regulated cell death that includes the iron-dependent accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides and the failure of antioxidant defenses (Chen et al., 2021). Glutamate and erastin induce this cell death pathway by inhibiting cystine uptake via the cystine/glutamate antiporter, leading to glutathione depletion (Soriano-Castell et al., 2021a). RSL3 triggers oxytosis/ferroptosis by directly inhibiting glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), resulting in lethal lipid peroxidation. Given the mechanistic specificity of oxytosis/ferroptosis, therapeutic strategies that restore GSH levels, boost antioxidant defenses, modulate lipid peroxidation, or chelate iron are gaining traction for their potential to provide effective neuroprotection against the multifactorial pathologies of AD (Maher et al., 2020a; Sun et al., 2025).

Medicinal plants with the ability to regulate oxidative cell death pathways such as oxytosis/ferroptosis are gaining attention as promising neuroprotective agents (Maher et al., 2020a). Among these, species rich in polyphenols and flavonoids such as Centella asiatica, and Curcuma longa (turmeric) have been reported to inhibit microglial activation, scavenge ROS, and suppress LPO (Lee et al., 2017; Maher et al., 2020b; Hambali et al., 2024). For example, Curcuma longa extracts (containing curcuminoids and synergistic compounds) inhibit Aβ aggregation and tau phosphorylation in preclinical models (da Costa et al., 2018; Oliveira and Pieniz, 2024). However, many plant species with therapeutic potential remain underexplored, highlighting the need to investigate novel botanical sources of bioactive compounds.

The genus Wyethia (Asteraceae family), native to western North America, encompasses species traditionally used by Indigenous peoples for medicinal purposes. These include treatments for respiratory, gastrointestinal and dermatological ailments (Moore and Bohs, 2003). These plants, colloquially termed mule’s ears, contain phenolic acids, flavonoids, and sesquiterpene lactones, phytochemicals linked to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in related Asteraceae species (Borgo et al., 2024). This ethnobotanical knowledge aligns with modern findings linking these phytochemicals to antioxidant and neuroprotective activities, thereby bridging traditional practice and laboratory investigation. Wyethia angustifolia and W. helenioides produce flavonoids, including quercetin derivatives, which are linked to ROS scavenging and NF-κB inhibition (McCormick et al., 1986). These phytochemicals may function through distinct mechanisms to disrupt oxytosis/ferroptosis at multiple points. These include iron chelation to inhibit LOX-driven lipid peroxidation, preservation of glutathione (GSH) via stabilization of the cystine/glutamate antiporter (xc−), and direct scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to prevent mitochondrial and membrane damage. Despite the rich ethnobotanical history of Wyethia, the potential of its species to modulate oxytosis/ferroptosis, and neuroinflammation in AD-relevant cell types remains largely unexplored. Traditional preparations of these plants often utilize leaves or roots, although detailed documentation of extraction methods is limited. In this study, dichloromethane extracts were used to target bioactive compounds with similar polarity.

In this context, we evaluated select Wyethia extracts for their ability to mitigate oxytosis/ferroptosis in HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells and for their anti-inflammatory effects in BV2 microglial cells. We also assessed their antioxidant capacity along with effects on GSH levels and lipid peroxidation to elucidate the mechanisms underlying their neuroprotective potential. Notably, several Wyethia extracts significantly protected HT22 cells against ferroptotic cell death, reduced oxidative stress by preserving GSH and lowering lipid peroxidation, and suppressed neuroinflammatory responses in BV2 cells. By addressing multiple age-associated toxicities relevant to AD, these findings highlight Wyethia species as promising botanical candidates for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, this study reaffirms the critical importance of herbarium collections as an excellent source of material for ethnopharmacological research. Herbarium specimens offer significant technical advantages over traditional field collection, including comprehensive historical documentation and accessibility, which were previously demonstrated in our work with the San Diego Natural History Museum. These advantages enable more robust and reproducible investigations, particularly when exploring traditional knowledge in botanical drug discovery.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant collection and extraction

Eight species of Wyethia were obtained from authenticated specimens stored in the SD Herbarium at the San Diego Natural History Museum (SDNHM). These species were selected for study due to their ecological significance, the limited prior research on their neuroprotective activity and phytochemical properties, and their traditional use by indigenous peoples for treating various ailments, highlighting their potential relevance to understanding plant adaptation and medicinal applications. The leaves of these plants were utilized for the study. The identification and verification of the specimens were primarily conducted by Jon Rebman, SDNHM Curator of Botany. Descriptive information for the eight Wyethia taxa, including the accession number, species name, common name, and collector ID is described in Table 1. Permission for sampling these herbarium specimens for research purposes was granted by Rebman, the curator in charge of this collection.

Mature leaves from dried plant specimens were carefully collected from herbarium samples with sufficient material. The extraction process followed the same methods previously described (Maher et al., 2020b). Briefly, the dried leaves were crushed, and dichloromethane (DCM) extracts were prepared by weighing 100 mg of plant material and dissolving it in 1 mL of DCM. DCM has historically been used in our laboratory for the initial broad-scale screening of herbarium specimens due to its effectiveness in extracting lipophilic compounds such as flavonoids, sesquiterpene lactones and other non-polar constituents, which we have found are strongly associated with neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities (Borgo et al., 2024). Preliminary extractions were also conducted using aqueous solvent to mimic traditional preparations, but these extracts showed minimal neuroprotective activity in our assays. Based on these findings, and to focus on bioactive lipophilic compounds, DCM was selected as the solvent for the detailed analysis. The mixture was shaken overnight using a mechanical shaker and then left to stand at room temperature. The next day, the solution was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the resulting filtrate was concentrated to dryness using a rotary evaporator. Any residual DCM was completely evaporated in a fume hood overnight. Once fully dried, the extract was weighed to determine the yield (Table 2). The dried extract was then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 50 mg/mL. Insoluble materials were removed by high-speed centrifugation and discarded. The final samples were stored at −80 °C for future use.

Table 2. EC50 values of Wyethia species extracts for neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities in HT22 and BV2 cells.

2.2 Cell culture condition

HT22 mouse hippocampal neuronal cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, United States) and incubated at 37 °C in a 10% CO2 atmosphere. Mouse BV2 microglial cells were cultured in low-glucose DMEM with 10% FCS and incubated under the same conditions.

2.3 Neuroprotection assays

2.3.1 Oxytosis/ferroptosis assay

For the oxytosis/ferroptosis assay, HT22 cells (5 × 103) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium, and cells were treated with 5 mM glutamate, 500 nM erastin, or 250 nM RSL3, along with extracts at concentrations ranging from 0.5–50 μg/mL. After 24 h of treatment, cell viability was assessed using the MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay (Liang et al., 2022), which measures mitochondrial metabolic activity as an indicator of cell viability. In the absence of neuroprotective compounds, more than 90% of the cells die under these conditions. Prior to adding the MTT reagent, the plates were examined microscopically to confirm that any observed effects were not due to interactions between the extracts and the assay chemistry.

2.3.2 Protection against energy loss (in vitro ischemia assay)

HT22 cells were seeded into 96-well plates as described in the oxytosis/ferroptosis assay. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium, and the cells were treated with 15 µM Iodoacetic acid (IAA), which induces 90%–95% cell death. After 2 h, the medium was aspirated and replaced with fresh medium containing the plant extracts at concentrations ranging from 0.5–50 μg/mL. After 24 h of treatment, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. The results were further confirmed by visual inspection of the wells.

2.3.3 Anti-inflammatory assay

The anti-inflammatory assay was performed as described (Fischer et al., 2019). Briefly, mouse BV2 microglial cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 in 35 mm tissue culture dishes and incubated overnight. The following day, cells were treated with 50 ng/mL bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) alone or in combination with plant extracts at concentrations ranging from 5 to 50 μg/mL. After 24 h of incubation, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 1 min at room temperature to remove floating cells. A 100 µL aliquot of the supernatant was then mixed with 100 µL of Griess reagent in a 96-well plate. Following a 10-min incubation at room temperature, absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader.

2.3.4 Total glutathione (GSH) measurement

The total GSH assay was conducted according to the method previously outlined (Liang et al., 2022). Briefly, HT22 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105 in 35 mm tissue culture dishes and incubated overnight. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and the indicated concentrations of glutamate (5 mM) and plant extracts were added. Following the 24 h treatments, cells were scraped into ice-cold PBS and mixed with 10% sulfosalicylic acid. The samples were kept on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube containing 24 µL of triethanolamine: PBS (1:1). Total GSH levels were determined using a recycling assay based on the reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) with glutathione reductase and NADPH. GSH levels were normalized to protein content, which was recovered from the acid-precipitated pellet by treatment with 0.2 N NaOH at 37 °C overnight and quantified using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, United States).

2.3.5 DPPH free radical scavenging assay

The DPPH free radical scavenging assay was conducted to evaluate the antioxidant activity of selected Wyethia species using the method described (Pringle et al., 2021). Briefly, 5 μL of the sample was mixed with 120 μL of Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) and 120 μL of DPPH solution (0.1 mM in absolute ethanol) in a 96-well microtiter plate. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark to prevent light-induced degradation. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 513 nm.

2.3.6 Lipid peroxidation assay

A cell-free assay to measure inhibition of lipid peroxidation was performed using the method described previously (Soriano-Castell et al., 2021a). A mixture of STY-BODIPY (1.5 μM) and egg-PC liposomes (1 mM) was prepared in TBS (pH 7.4) and dispensed into an opaque 96-well plate. The plant extracts were then added to the well at a final concentration of 25 μg/mL. The plate was incubated for 30 min and subsequently mixed vigorously for 5 min. Autoxidation was initiated by adding V-70 (750 μM), followed by another 5 min of mixing. Fluorescence measurements were taken every 15 min at 37 °C using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader with excitation/emission wavelengths set at 488/518 nm. The raw fluorescence data were converted to oxidized STY-BODIPY concentration ([ox-STY-BODIPY]) by normalizing the saturated fluorescence values of the control to the initial concentration of reduced STY-BODIPY (1.5 μM).

2.3.7 Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content was quantified using a modified version of the Folin–Ciocalteu (F-C) colorimetric assay as outlined (Kovačević et al., 2023). Samples and standards were pipetted into a 96-well plate, followed by the addition of ultrapure water (milliQ® water, Merck, NJ, United States) and the F-C reagent, which was diluted 1:1 with water. After a 5-min incubation period, a saturated sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution (7.5% w/v) was added. The plate was then incubated for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader. The results were calculated by interpolating the data against a gallic acid standard curve (0–100 μg/mL). The total phenolic content (TPC) was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg GAE/g extract) and reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data from at least three independent experiments were normalized, pooled, and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10). Statistical tests applied are indicated in the figure legends, and a significance threshold of P < 0.05 was used. The half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50 values) were determined from sigmoidal dose-response curves generated using GraphPad Prism 10.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of the screening process and initial species evaluation

Eight Wyethia species were initially screened for their protective effects against oxytosis/ferroptosis using HT22 cells. Those extracts exhibiting significant protection (EC50 < 50 μg/mL) were further evaluated in the in vitro ischemia assay, also in HT22 cells. All Wyethia species that demonstrated significant protection in the oxytosis/ferroptosis assay were tested for anti-inflammatory activity in BV2 microglial cells, a widely used model for studying neuroinflammation. These cells retain essential microglial functions such as phagocytosis and the ability to respond to inflammatory stimuli by secreting nitric oxide (NO) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Tawbeh et al., 2023).

To achieve a more comprehensive characterization, all eight Wyethia species were also subjected to a series of biochemical assays. The DPPH free radical scavenging assay was used to assess antioxidant activity, the cell-free lipid peroxidation assay evaluated lipid oxidation resistance, and total phenolic content was measured to estimate polyphenolic composition. This integrative approach enabled a thorough exploration of potential correlations between protective effects and biochemical properties across all species, regardless of their performance in the initial oxytosis/ferroptosis screening.

3.2 Cytotoxicity and neuroprotection in oxytosis/ferroptosis models

To ensure the safety and effective dosing of Wyethia extracts, cytotoxicity assays were performed on HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells. This testing identifies concentrations that do not harm cell viability, providing a baseline for subsequent neuroprotection experiments. Most Wyethia species exhibited no significant cytotoxicity at the tested concentrations of 5, 12.5, 25 and 50 μg/mL (LD50 > 50 μg/mL), except for W. ovata, which showed a toxicity EC50 of 6.2 μg/mL, indicating high cytotoxicity (Table 2). These findings highlight substantial variability in cytotoxic profiles among Wyethia species, which is critical for optimizing therapeutic dosing in models of oxytosis/ferroptosis.

3.3 Neuroprotective effects of Wyethia extracts in oxidative stress models

To evaluate the neuroprotective potential of Wyethia species against oxytosis/ferroptosis, we screened the non-toxic extracts against glutamate (5 mM), erastin (500 nM) and RSL3 (250 nM) at concentrations of 5, 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL. These compounds mimic oxidative stress-related neuronal death relevant to neurodegenerative diseases (Fei and Ding, 2024). Due to its cytotoxicity at concentrations above 5 μg/mL, W. ovata was additionally tested at lower concentrations (0.5, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μg/mL) in all neuroprotection assays. The results (Table 2) show that W. ovata demonstrated notable protective effects, with EC50 values of 2.2 μg/mL for glutamate, 3.3 μg/mL for erastin, and 2.5 μg/mL for RSL3. Among the non-toxic species, W. helenioides demonstrated the strongest neuroprotective effects, with EC50 values of 5.7 μg/mL for glutamate, 9.6 μg/mL for erastin, and 9.7 μg/mL for RSL3. Similarly, W. glabra, W. amplexicaulis and W. invenusta exhibited strong protection across multiple oxytotic/ferroptotic stressors, with EC50 values ranging from 10.3 to 23.3 μg/mL. In contrast, W. scabra, W. elata, and W. mollis showed little or no protective effects, as their EC50 values exceeded 50 μg/mL for most stressors. While variability in neuroprotective efficacy among Wyethia species was observed, several species demonstrated strong protective effects, thereby supporting our working hypothesis.

3.4 Protection against energy loss in iodoacetic acid-induced neurotoxicity

Iodoacetic acid (IAA) induces cell death by disrupting glycolysis and causing oxidative stress, making it a useful model to study energy metabolism-related neurotoxicity. Protection against IAA toxicity was also evaluated in HT22 cells (Table 2). Among the tested species, W. ovata exhibited the strongest protection, with an EC50 value of 3.4 μg/mL. W. glabra (EC50 = 10.1 μg/mL), W. helenioides (EC50 = 11.1 μg/mL) and W. amplexicaulis (EC50 = 11.8 μg/mL) also showed strong protective effects. W. invenusta (EC50 = 15.6 μg/mL) and W. mollis (EC50 = 33.3 μg/mL) displayed moderate protection, while W. scabra and W. elata were not tested in this assay due to lack of protection against oxytosis/ferroptosis. Taken together, these results demonstrate that several Wyethia species show strong protection against energy metabolism-associated oxidative neurotoxicity, supporting the hypothesis that their traditional uses reflect genuine biochemical activities related to oxidative stress pathways.

3.5 Anti-inflammatory activity of Wyethia extracts in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells

Neuroinflammation is a key contributor to neurodegenerative diseases, often mediated by activated microglia producing inflammatory molecules such as nitric oxide (NO). To assess the anti-inflammatory potential of Wyethia species, BV-2 microglial cells were stimulated with LPS (50 ng/mL) to induce nitric oxide (NO) production, a key marker of inflammation. The calculated EC50 values for each extract are summarized in Table 2. W. scabra and W. elata extracts were excluded from further anti-inflammatory evaluation because they did not demonstrate protective effects against oxytosis/ferroptosis in the HT22 cells.

As shown in Figure 1, LPS treatment significantly increased NO production compared to the untreated control. Most of the tested Wyethia extracts exhibited a dose-dependent reduction in NO levels, with significant reduction observed at higher concentrations (p < 0.05 compared to LPS control). Among the tested species, W. ovata, W. mollis and W. invenusta exhibited the strongest NO-suppressing effects, particularly at 25 and 50 μg/mL.

Figure 1. Inhibition of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Nitric Oxide Production by Wyethia species Extracts. Nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated cells was normalized to cell density and expressed as a percentage relative to LPS control. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests. Asterisks indicate significant differences between Wyethia extract-treated groups and the LPS control (50 ng/mL) (****p < 0.0001), while ‘ns’ denotes non-significant differences. Significance symbols at each concentration indicate that at least one extract showed a significant difference from the LPS control. Values represent the mean + SD, n = 3.

Importantly, MTT analysis confirmed that the observed reduction in NO level was not due to cytotoxicity (data not shown), as none of the tested Wyethia extracts caused significant cell death at the tested concentrations. Notably, W. ovata, which was toxic to HT22 cells did not exhibit cytotoxic effects in BV-2 cells and demonstrated strong anti-inflammatory activity. These findings suggest that select Wyethia species possess promising anti-inflammatory properties by modulating NO production in activated microglia without compromising cell viability.

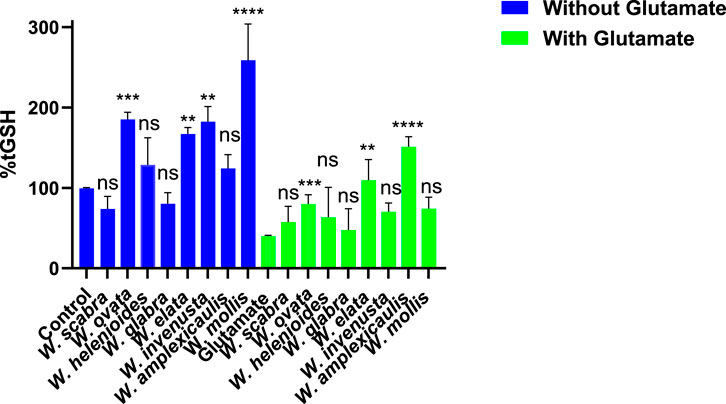

3.6 Intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in HT22 cells treated with Wyethia extracts

Glutathione (GSH) is a critical intracellular antioxidant that protects cells from oxidative damage and is a key factor in cellular defense mechanisms against oxytosis/ferroptosis, two forms of regulated cell death associated with neurodegeneration. Measuring GSH levels following treatment with Wyethia extracts provides insight into their potential to enhance antioxidant capacity and mitigate oxidative stress. As shown in Figure 2, treatment with Wyethia extracts alone resulted in variable effects on GSH levels. W. elata, W. invenusta, W. mollis and W. ovata significantly increased GSH levels compared to the control (p < 0.01 to p < 0.0001), with W. mollis showing the most pronounced increase (∼290% of control). In contrast, W. scabra, W. helenioides and W. glabra did not significantly alter GSH levels.

Figure 2. Effect of Wyethia species extracts (25 μg/mL, except W. ovata at 5 μg/mL) on intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels in HT22 cells in the presence and absence of glutamate (5 mM). Intracellular GSH levels were measured and expressed as percentage relative to the control. For the blue bars (without glutamate), each Wyethia extract’s GSH level was compared to the untreated control. For the green bars (with glutamate), GSH levels for each Wyethia extract were compared to glutamate-treated cells without extracts. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0005, **p < 0.01, and ns = not significant. Values represent mean ± SD, n = 3.

Glutamate treatment (5 mM) led to a substantial depletion of GSH (∼41% of control, p < 0.0001), confirming the expected reduction in GSH synthesis. Pre-treatment with Wyethia extracts provided varying degrees of protection. Notably, only W. amplexicaulis (p < 0.0001), W. ovata (p = 0.0005) and W. elata (p < 0.01) significantly maintained GSH levels in the presence of glutamate, while W. scabra, W. glabra, W. invenusta and W. mollis showed no significant effect compared to glutamate alone. These results suggest that Wyethia species, particularly W. amplexicaulis may enhance cellular antioxidant capacity by preserving intracellular GSH, which may contribute to their protective effects against oxidative stress.

3.7 Antioxidant activity measured by DPPH free radical scavenging assay

The direct antioxidant potential of Wyethia species extracts was evaluated using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay, which measures the ability of compounds to neutralize free radicals and thus indicates their capacity to counteract general oxidative stress. Vitamin C was included as positive controls for comparison. As shown in Figure 3, the radical scavenging activity varied among the Wyethia species and within species increased in a concentration-dependent manner. All tested Wyethia species exhibited dose-dependent DPPH radical scavenging activity. Among the tested species, W. ovata and W. mollis exhibited the highest DPPH scavenging activity, approaching levels comparable to Vitamin C, whereas W. scabra and W. elata displayed the weakest activity across all concentrations. Other species, including W. helenioides, W. invenusta, W. glabra, and W. amplexicaulis, demonstrated moderate scavenging activity, with significant increases at higher concentrations (p < 0.0001). These findings suggest that certain Wyethia species possess strong antioxidant properties, likely due to their ability to neutralize free radicals.

Figure 3. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Wyethia Species Extracts at Different Concentrations. The antioxidant activity of Wyethia species extracts was assessed using the DPPH radical scavenging assay and expressed as a percentage of DPPH radicals scavenged relative to the control. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests. Asterisks indicate concentrations at which at least one extract or the standard (Vitamin C) showed a significant difference compared to the control (****p < 0.0001). Values represent the mean + SD, n = 3.

3.8 Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by Wyethia extracts

Lipid peroxidation is a hallmark of oxytosis/ferroptosis, contributing to oxidative damage and cell death. The lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity of Wyethia species extracts was assessed using the oxidation of STY-BODIPY as a marker, with results expressed as the concentration of oxidized STY-BODIPY ([oxy-STY-BODIPY], µM) over time (Figure 4A) and as the area under the curve (AUC) relative to the control (DMSO) (Figure 4B). The kinetics of lipid peroxidation revealed distinct differences in the efficacy of Wyethia species extracts. The DMSO-treated control exhibited rapid and sustained lipid peroxidation, reaching the highest levels of [oxy-STY-BODIPY] (∼1.0 µM) over 150 min. In contrast, gossypol, a known lipid peroxidation inhibitor (Soriano-Castell et al., 2021a), maintained minimal oxidation levels throughout the assay, serving as a positive control.

![Graph A shows a line chart of [oxy-STY-BODIPY] concentration over time for different compounds, with DMSO peaking highest and Gossypol lowest. Graph B is a bar chart displaying LPO levels as a percentage of control, where all compounds significantly reduce LPO compared to DMSO, particularly W. scabra. Error bars indicate standard deviation.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1740121/fphar-16-1740121-HTML/image_m/fphar-16-1740121-g004.jpg)

Figure 4. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation by Wyethia species extracts: time-dependent kinetics and area under the curve (AUC). (A) Time-dependent inhibition of lipid peroxidation ([oxy-STY-BODIPY], µM) by Wyethia species extracts in comparison to gossypol (positive control) and DMSO (negative control). Lipid peroxidation was monitored over 150 min. (B) Quantification of lipid peroxidation inhibition as the area under the curve (AUC), expressed as a percentage of the DMSO control. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests; significant differences between DMSO control and extract-treated groups are indicated (****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0005). Values represent the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Among the Wyethia species tested, W. ovata, W. helenioides and W. amplexicaulis, demonstrated the strongest inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation, with a profile similar to gossypol. W. invenusta, and W. glabra also exhibited notable inhibition, although to a lesser extent. Conversely, W. scabra, W. elata and W. mollis showed weaker inhibition, with oxidation trends closer to the DMSO control.

The AUC analysis further confirmed these observations. Gossypol achieved near-complete inhibition of lipid peroxidation, with an AUC value close to zero. Among the Wyethia species, W. ovata, W. helenioides and W. amplexicaulis showed significant reductions in AUC compared to DMSO, indicating strong antioxidant activity (p < 0.001). In contrast, W. scabra W. elata and W. mollis had AUC values similar to DMSO, reflecting their weak inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation. Moderate reductions in AUC were observed for W. glabra and W. invenusta, consistent with their intermediate activity. These results indicate that certain Wyethia species, particularly W. helenioides, possess strong lipid peroxidation inhibitory properties, which may contribute to their protective effects against oxytosis/ferroptosis. The variability in activity among species suggests differences in their phytochemical composition and antioxidant mechanisms.

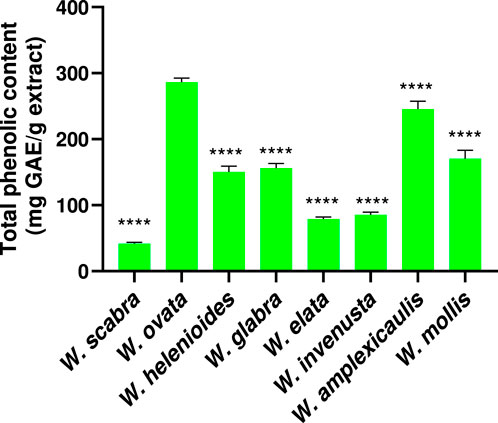

3.9 Total phenolic content of Wyethia species

Phenolic compounds are important plant-derived antioxidants, which can contribute to neuroprotection by mitigating oxidative stress involved in oxytosis/ferroptosis. To quantify these compounds, the total phenolic content (TPC) of the Wyethia species was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay with results expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE) per gram of extract. The results revealed considerable variation in TPC among the different Wyethia species (Figure 5). W. ovata exhibited the highest TPC, measuring approximately 286 mg GAE/g extract, followed by W. amplexicaulis (≈245 mg GAE/g extract) and W. mollis (≈170 mg GAE/g extract). Moderate levels were observed in W. glabra and W. helenioides with values ranging between 120 and 160 mg GAE/g extract, which were higher than those of W. elata and W. invenusta. In contrast, W. scabra had the lowest phenolic content, with less than 50 mg GAE/g extract.

Figure 5. Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay and expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE) per gram of extract. Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, with W. ovata used as the reference group. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to W. ovata (****p < 0.0001).

Taken together, the results of this study found that several extracts of Wyethia species exhibited robust antioxidant activity and significant neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in the experimental models used. To provide a comprehensive comparison, Table 3 summarizes the DPPH radical scavenging activity (EC50), ability to increase GSH levels under glutamate-induced stress, lipid peroxidation inhibition, total phenolic content, neuroprotection across multiple pathways (including glutamate, erastin, RSL3 and IAA), and anti-inflammatory activity for each extract. The table highlights the distinct biochemical profiles and activities observed among the different species. This overview facilitates identification of species with the most promising bioactivity profiles.

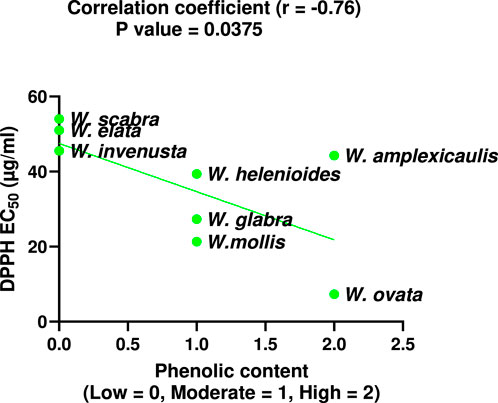

To further investigate the relationship between phenolic content and antioxidant capacity, a correlation analysis was performed. As shown in Figure 6, there is a strong, statistically significant negative correlation between total phenolic content and DPPH EC50 values across Wyethia species.

Figure 6. Correlation between total phenolic content and DPPH EC50 values for Wyethia species. Phenolic content was coded as Low = 0, Moderate = 1, High = 2. Lower DPPH EC50 values indicate higher antioxidant activity. A significant negative correlation was observed (Spearman r = −0.76, p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

This study demonstrated significant neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of multiple Wyethia species extracts in in vitro models of oxytosis/ferroptosis, energy loss and inflammation. By utilizing herbarium specimens, we efficiently screened a diverse range of species without the need for fresh collections, leveraging the unique advantages of preserved botanical materials. Herbarium samples have recently gained recognition as valuable resources for drug discovery, enabling access to rare or geographically restricted taxa with well-documented provenance. For instance, Maher et al. (2020b) successfully identified neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities in herbarium specimens of the genus Eriodictyon. Our work builds on this approach by demonstrating the bioactivity of Wyethia species, supporting their further investigation as candidates for therapeutic development in neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases. Herbarium specimens offer valuable botanical material for screening, with compound classes like flavonoids and phenolic acids generally stable over long periods. While some volatile or labile compounds may degrade, no significant phytochemical degradation was observed in herbarium specimens studied previously in our lab (Maher et al., 2020b). These findings support the reliability of herbarium samples for bioactivity assessment.

Selected Wyethia species, including W. ovata, W. glabra, W. helenioides, W. invenusta, and W. amplexicaulis demonstrated significant protection of HT22 cells from glutamate, erastin and RSL3 induced toxicity, which are models of oxytosis/ferroptosis. In addition, these species also provided significant protection against IAA-induced toxicity, which represents a distinct mechanism of cell death. The observed neuroprotection aligns with findings in previous studies on plant-derived polyphenols, which have been shown to mitigate oxidative stress by counteracting glutathione depletion and maintaining mitochondrial function (Fischer et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020; Taïlé et al., 2020). The ability of these Wyethia species to protect across multiple oxidative stressors is particularly compelling, as evidenced by their low EC50 values (2.2–23.3 μg/mL). This suggests that their protective effects may not be confined to a single mechanism but could reflect a broader capacity to stabilize redox homeostasis and preserve cellular energy production.

Interestingly, W. ovata exhibited a dose-dependent dual effect, providing neuroprotection at low concentrations, while showing cytotoxicity at higher doses in HT22 cells. This biphasic response may be explained by hormesis, a phenomenon where low doses of bioactive compounds induce adaptive protective responses, whereas higher doses cause toxicity. Sesquiterpene lactones, known constituents of Wyethia species, have been reported to exhibit such concentration-dependent dual activities (da Silva et al., 2021) This observation is critical in interpreting the neuroprotective data and suggests a narrow therapeutic window for certain extracts, which warrants further mechanistic investigation.

The anti-inflammatory activity of Wyethia extracts further supports their therapeutic potential, as several species effectively inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated BV-2 microglial cells. In particular, W. ovata, W. mollis, and W. amplexicaulis exhibited strong, dose-dependent inhibition of NO production without inducing cytotoxicity. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that plant-derived compounds can modulate inflammation by targeting key signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK, which regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators (Saleh et al., 2021; Kang et al., 2023; Nakadate et al., 2025). Given the role of chronic inflammation in neurodegeneration, these dual neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects underscore the therapeutic promise of Wyethia species.

Assessment of intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels revealed partial restoration with W. amplexicaulis, W. ovata, and W. elata. Preservation of GSH is significant, given that its depletion is a hallmark of oxytosis/ferroptosis and its restoration is a key neuroprotective strategy (Maher et al., 2020b). Interestingly, despite elevating GSH, W. elata did not protect cells from glutamate, erastin, or RSL3 toxicity, suggesting that GSH restoration alone may be insufficient for full neuroprotection. This discrepancy likely reflects differences in phytochemical profiles and indicates that additional mechanisms contribute to effective protection.

The DPPH radical scavenging results demonstrate strong antioxidant activity for W. ovata and W. mollis. This likely reflects their high phenolic content, known to donate hydrogen atoms to stabilize free radicals. Most other Wyethia species exhibited moderate scavenging activity in a dose-dependent manner, consistent with the typical behavior of plant-derived antioxidants in DPPH assays (Sagbo et al., 2017; Gulcin and Alwasel, 2023). Notably, W. scabra and W. elata, which displayed weak DPPH activity also showed little to no neuroprotective effects in the neuroprotection assays. This correlation suggests that direct radical scavenging may contribute significantly to the neuroprotective potential of Wyethia species. The lack of both antioxidant and neuroprotective activity in W. scabra and W. elata highlights the importance of free radical neutralization as a key mechanism in mitigating oxidative stress-related toxicity.

The lipid peroxidation data provide compelling evidence that specific Wyethia species also possess a strong ability to inhibit membrane lipid oxidation. Notably, W. ovata, W. helenioides, W. amplexicaulis, and W. invenusta showed strong suppression of STY-BODIPY oxidation, with profiles resembling the known lipid peroxidation inhibitor gossypol. These findings suggest that these species contain bioactive compounds capable of directly scavenging lipid radicals or disrupting chain reactions involved in oxidative membrane damage. Thus, the lipid peroxidation inhibitory capacity of these extracts likely plays a central role in their neuroprotective effects observed against glutamate, erastin and RSL3-induced cell death. The variation in activity among species ranging from strong inhibition with W. ovata to weak or negligible effects with W. scabra and W. elata, highlights interspecies differences in anti-lipid peroxidation properties, likely driven by distinct phytochemical profiles.

The differences observed between the DPPH radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibition assays likely reflect the distinct antioxidants each assay detects. DPPH mainly measures the ability to neutralize hydrophilic radicals, while lipid peroxidation assays assess the ability to neutralize lipophilic radicals. This likely explains why some extracts act strongly in one assay but weakly in the other as the effects will depend on the distinct array of compounds present in each extract. These differences further support the use of multiple assays for a full antioxidant profile. The observed variation in TPC across Wyethia species highlights differential polyphenol accumulation, with W. ovata and W. amplexicaulis exhibiting the highest TPC. While W. ovata displayed strong antioxidant activity in both DPPH and lipid peroxidation assays, W. amplexicaulis showed strong lipid peroxidation inhibition but moderate DPPH radical scavenging activity. Several other species, including W. helenioides, W. glabra, and W. mollis, demonstrated moderate TPC and varying levels of antioxidant capacity. These results support the multifunctional antioxidant role of phenolics described in the literature, as only W. ovata exhibited both high total phenolic content and potent antioxidant activity across all assays. This indicates that, in W. ovata, polyphenols likely serve as effective radical scavengers and inhibitors of lipid peroxidation, as previously reported (Aryal et al., 2019; Osman et al., 2020; Andrés et al., 2024). However, not all of the Wyethia species showed significant neuroprotection in the oxytosis/ferroptosis models indicating that polyphenol content alone is not a reliable predictor of neuroprotective activity. Notably, W. invenusta, despite an intermediate TPC, demonstrated significant neuroprotection, suggesting non-phenolic compounds (terpenoids, alkaloids) may drive its effects. For instance, oleanolic acid, a terpenoid found in some plants, correlates with antioxidant activity in other species, while sulfur-containing compounds could modulate oxytosis/ferroptosis by acting as precursors for glutathione synthesis or by directly inhibiting lipid peroxidation, thereby protecting cells from death (Osman et al., 2020; Ortiz-Mendoza et al., 2023). Indeed, sesquiterpene lactones are common in many Asteraceae plants and are characterized by reactive α-methylene-γ-lactone groups that interact with cellular proteins and modulate pathways relevant to antioxidants, NF-κB inhibitory, and cytotoxic activities (Matos et al., 2021). Although their presence in Wyethia species has not been extensively characterized, they could contribute to the observed bioactivity and toxicity patterns. These results suggest that, beyond polyphenols, other compound classes present in Wyethia extracts could play a significant role in the observed neuroprotective and antioxidant activities. Conversely, W. scabra and W. elata showed low TPC and limited neuroprotective activity. In W. elata, enhancement of GSH alone was insufficient to block oxytosis/ferroptosis consistent with its very weak inhibition of lipid peroxidation and lack of DPPH radical scavenging activity. Therefore, effective protection against oxytosis/ferroptosis may require the combined action of multiple pathways. These findings underscore TPC as an important, but not exclusive, determinant of the bioactivity of Wyethia.

Overall, the multifaceted protection observed likely arises from a complex interplay of antioxidant activity, glutathione preservation, and anti-inflammatory effects across species, highlighting their diverse chemical profiles. This diversity, coupled with the emerging relevance of oxytosis/ferroptosis and inflammation in neurodegeneration (Soriano-Castell et al., 2021b; Currais et al., 2025), positions Wyethia species as promising neuroprotective agents.

Given the complex nature of neurodegenerative diseases involving oxidative stress, oxytosis/ferroptosis, and inflammation, whole Wyethia extracts may provide advantages over isolated compounds for therapeutic use. The observed bioactivities suggest a plausible mechanism of action centered on multifaceted oxidative stress modulation through direct radical scavenging, inhibition of lipid peroxidation cascades and preservation of glutathione homeostasis. The diverse bioactive compounds in the extracts could work synergistically to enhance neuroprotective effects by targeting multiple convergent pathways. Minor constituents may further improve efficacy and bioavailability. Therefore, using whole extracts leverages natural phytochemical interactions, potentially offering more effective and safer strategies to combat neurodegeneration. Importantly, the methodological approach applied here, which prioritizes plants traditionally used by native peoples, is significantly facilitated by the utilization of herbarium samples. Herbarium collections provide invaluable, well-documented plant material that greatly enhances the feasibility and depth of ethnopharmacological studies, reinforcing the bridge between traditional knowledge and modern therapeutic discovery.

5 Conclusion

This study highlights the neuroprotective potential of selected Wyethia species mediated through multiple mechanisms including antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation inhibition, glutathione preservation, and anti-inflammatory effects. However, notable interspecies variability highlights the importance of comprehensive phytochemical profiling to identify the most promising candidates. The interspecies differences likely reflect unique phytochemical profiles and mechanisms of action. Importantly, this study underscores the value of an ethnopharmacological approach that integrates the use of medicinal plants historically employed by native peoples with modern extraction from well-documented herbarium specimens. This combination facilitates rigorous investigation of bioactive extracts, as exemplified by the positive anti-oxytotic/ferroptotic and anti-inflammatory effects observed here. This methodological framework, leveraging both traditional knowledge and herbarium resources, advances the identification and validation of promising neuroprotective botanical candidates, supporting future drug discovery efforts against neurodegenerative diseases. Future work will focus on bioassay-guided fractionation and LC-MS profiling to identify active compounds in the most effective extracts which was beyond the scope of this initial bioactivity-driven screening study. Future in vivo validation is also planned in order to establish therapeutic potential.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

IS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. DS-C: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JR: Resources, Writing – review and editing. PM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by NIA grant AG069206 to PM and a generous donation to Salk from Jim and Michelle Styring.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the invaluable support of the collections management staff and volunteers within the Department of Botany at the SDNHM.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alkhalifa, A. E., Alkhalifa, O., Durdanovic, I., Ibrahim, D. R., and Maragkou, S. (2025). Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: insights into pathophysiology and treatment. J. Dement. Alzheimers Dis. 2 (2), 17. doi:10.3390/jdad2020017

Andrés, C. M. C., Pérez de la Lastra, J. M., Juan, C. A., Plou, F. J., and Pérez-Lebeña, E. (2024). Antioxidant metabolism pathways in vitamins, polyphenols, and selenium: parallels and divergences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2600. doi:10.3390/ijms25052600

Aryal, S., Baniya, M. K., Danekhu, K., Kunwar, P., Gurung, R., and Koirala, N. (2019). Total phenolic content, flavonoid content and antioxidant potential of wild vegetables from Western Nepal. Plants 8 (4), 96. doi:10.3390/plants8040096

Borgo, J., Wagner, M. S., Laurella, L. C., Elso, O. G., Selener, M. G., Clavin, M., et al. (2024). Plant extracts and phytochemicals from the Asteraceae family with antiviral properties. Molecules 29 (4), 814. doi:10.3390/molecules29040814

Chen, K., Jiang, X., Wu, M., Cao, X., Bao, W., and Zhu, L. Q. (2021). Ferroptosis, a potential therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 5 (9), 704298. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.704298

Cui, X., Lin, Q., and Liang, Y. (2020). Plant-derived antioxidants protect the nervous system from aging by inhibiting oxidative stress. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 209. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2020.00209

Currais, A., Sanchez, K., Soriano-Castell, D., Dar, N. J., Evensen, K. G., Soriano, S., et al. (2025). Transcriptomic signatures of oxytosis/ferroptosis are enriched in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Biol. 23 (1), 132. doi:10.1186/s12915-025-02235-6

da Costa, I. M., de Moura Freire, M. A., de Paiva Cavalcanti, J. R. L., de Araújo, D. P., Norrara, B., Moreira Rosa, I. M. M., et al. (2018). Supplementation with Curcuma longa reverses neurotoxic and behavioral damage in models of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 17 (5), 406–421. doi:10.2174/0929867325666180117112610

da Silva, L. P., Borges, B. A., Veloso, M. P., Chagas-Paula, D. A., Gonçalves, R. V., and Novaes, R. D. (2021). Impact of sesquiterpene lactones on the skin and skin-related cells? A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo evidence. Life Sci. 265 (15), 118815. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118815

Fei, Y., and Ding, Y. (2024). The role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 1475934. doi:10.3389/fncel.2024.1475934

Fischer, W., Currais, A., Liang, Z., Pinto, A., and Maher, P. (2019). Old age-associated phenotypic screening for Alzheimer’s disease drug candidates identifies sterubin as a potent NeuroProtective compound from Yerba santa. Redox Biol. 21, 101089. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.101089

Gulcin, İ., and Alwasel, S. H. (2023). DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes 11 (8), 2248. doi:10.3390/pr11082248

Hambali, A., Jusril, N. A., Md Hashim, N. F., Abd Manan, N., Adam, S. K., Mehat, M. Z., et al. (2024). The standardized extract of Centella asiatica and its fractions exert antioxidative and anti-neuroinflammatory effects on microglial cells and regulate the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. J. Alzheimers Dis. 99 (s1), S119–S138. doi:10.3233/JAD-230875

Kang, E., Lee, J., Seo, S., Uddin, S., Lee, S., Han, S. B., et al. (2023). Regulation of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant responses by methanol extract of Mikania cordata (Burm. f.) B. L. Rob. leaves via the inactivation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and activation of Nrf2 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 168, 115746. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115746

Kovačević, T. K., Major, N., Sivec, M., Horvat, D., Krpan, M., Hruškar, M., et al. (2023). Phenolic content, amino acids, volatile compounds, antioxidant capacity, and their relationship in wild garlic (A. ursinum L.). Foods 12 (11), 2110. doi:10.3390/foods12112110

Lee, H. Y., Kim, S. W., Lee, G. H., Choi, M. K., Chung, H. W., Lee, Y. C., et al. (2017). Curcumin and Curcuma longa L. extract ameliorate lipid accumulation through the regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum Redox and ER stress. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 6513. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06872-y

Liang, Z., Soriano-Castell, D., Kepchia, D., Duggan, B. M., Currais, A., and Schubert, D. (2022). Cannabinol inhibits oxytosis/ferroptosis by directly targeting mitochondria independently of cannabinoid receptors. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 180, 33–51. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.01.001

Maher, P., Currais, A., and Schubert, D. (2020a). Using the oxytosis/ferroptosis pathway to understand and treat age-associated neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Chem. Biol. 27 (12), 1456–1471. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.10.010

Maher, P., Fischer, W., Liang, Z., Soriano-Castell, D., Pinto, A. F. M., Rebman, J., et al. (2020b). The value of herbarium collections to the discovery of novel treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, a case made with the genus eriodictyon. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 208. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00208

Matos, M. S., Anastácio, J. D., and Nunes Dos Santos, C. (2021). Sesquiterpene lactones: promising natural compounds to fight inflammation. Pharm 13 (7), 991. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13070991

McCormick, S., Robson, K., and Bohm, B. (1986). Flavonoids of Wyethia angustifolia and W. helenioides. Phytochem 25 (7), 1723–1726. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81244-3

Misrani, A., Tabassum, S., and Yang, L. (2021). Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 617588. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.617588

Moya-Alvarado, G., Gershoni-Emek, N., Perlson, E., and Bronfman, F. C. (2016). Neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). What can proteomics tell us about the Alzheimer’s brain? Mol. Cell Proteomics 15 (2), 409–425. doi:10.1074/mcp.R115.053330

Moore, A. J., and Bohs, L. (2003). An its phylogeny of balsamorhiza and wyethia (Asteraceae: Heliantheae). Am. J. Bot. 90 (11), 1653–1660. doi:10.3732/ajb.90.11.1653

Nakadate, K., Ito, N., Kawakami, K., and Yamazaki, N. (2025). Anti-inflammatory actions of plant-derived compounds and prevention of chronic diseases: from molecular mechanisms to applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 5206. doi:10.3390/ijms26115206

Oliveira, J. T., and Pieniz, S. (2024). Curcumin in Alzheimer’s disease and depression: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 67, e24220004. doi:10.1590/1678-4324-2024220004

Ortiz-Mendoza, N., San Miguel-Chávez, R., Martínez-Gordillo, M. J., Basurto-Peña, F. A., Palma-Tenango, M., and Aguirre-Hernández, E. (2023). Variation in terpenoid and flavonoid content in different samples of Salvia semiatrata collected from Oaxaca, Mexico, and its effects on antinociceptive activity. Metabolites 13 (7), 866. doi:10.3390/metabo13070866

Osman, M. A., Mahmoud, G. I., and Shoman, S. S. (2020). Correlation between total phenols content, antioxidant power and cytotoxicity. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 11 (3), 10640–10653. doi:10.33263/BRIAC113.1064010653

Pringle, N. A., Van De Venter, M., and Koekemoer, T. C. (2021). Comprehensive: in vitro antidiabetic screening of Aspalathus linearis using a target-directed screening platform and cellomics. Food Funct 12 (3), 1020–1038. doi:10.1039/d0fo02611e

Sagbo, I. J., Afolayan, A. J., and Bradley, G. (2017). Antioxidant, antibacterial and phytochemical properties of two medicinal plants against the wound infecting bacteria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 7 (9), 817–825. doi:10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.08.009

Saleh, H. A., Yousef, M. H., and Abdelnaser, A. (2021). The anti-inflammatory properties of phytochemicals and their effects on epigenetic mechanisms involved in TLR4/NF-κB-Mediated inflammation. Front. Immunol. 12, 606069. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.606069

Soriano-Castell, D., Liang, Z., Maher, P., and Currais, A. (2021a). Profiling the chemical nature of anti-oxytotic/ferroptotic compounds with phenotypic screening. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 177, 313–325. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.11.003

Soriano-Castell, D., Liang, Z., Maher, P., and Currais, A. (2021b). The search for anti-oxytotic/ferroptotic compounds in the plant world. Br. J. Pharmacol. 178 (18), 3611–3626. doi:10.1111/bph.15517

Sun, D., Wang, L., Wu, Y., Yu, Y., Yao, Y., Yang, H., et al. (2025). Lipid metabolism in ferroptosis: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential. Front. Immunol. 16, 1545339. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1545339

Sutanto, H., Pratiwi, L., and Fetarayani, D. (2025). Exploring ferroptosis in allergic inflammatory diseases: emerging mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Cell Biol. Int. 49 (7), 739–756. doi:10.1002/cbin.70026

Taïlé, J., Arcambal, A., Clerc, P., Gauvin-Bialecki, A., and Gonthier, M.-P. (2020). Medicinal plant polyphenols attenuate oxidative stress and improve inflammatory and vasoactive markers in cerebral endothelial cells during hyperglycemic condition. Antioxidants 9 (7), 573. doi:10.3390/antiox9070573

Tawbeh, A., Raas, Q., Tahri-Joutey, M., Keime, C., Kaiser, R., Trompier, D., et al. (2023). Immune response of BV-2 microglial cells is impacted by peroxisomal beta-oxidation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 16, 1299314. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2023.1299314

Tönnies, E., and Trushina, E. (2017). Oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 57 (4), 1105–1121. doi:10.3233/JAD-161088

Wang, C., Zong, S., Cui, X., Wang, X., Wu, S., Wang, L., et al. (2023). The effects of microglia-associated neuroinflammation on Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Immunol. 14, 1117172. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1117172

Zeng, H., and Jin, Z. (2025). The role of ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Mol. Med. Rep. 32 (1), 1–10. doi:10.3892/mmr.2025.13557

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neuroprotection, oxytosis/ferroptosis, polyphenols, Wyethia

Citation: Sagbo IJ, Soriano-Castell D, Rebman J and Maher P (2026) Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activity of Wyethia species: therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1740121. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1740121

Received: 05 November 2025; Accepted: 26 December 2025;

Published: 15 January 2026.

Edited by:

Bee Ling Tan, Management and Science University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Yang Zhu, National University of Singapore, SingaporeAnkul Singh S, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, India

Copyright © 2026 Sagbo, Soriano-Castell, Rebman and Maher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pamela Maher, cG1haGVyQHNhbGsuZWR1

Idowu Jonas Sagbo

Idowu Jonas Sagbo David Soriano-Castell

David Soriano-Castell Jon Rebman2

Jon Rebman2 Pamela Maher

Pamela Maher