Abstract

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder associated with recurring seizures that in about one-third of individuals are resistant to conventional medications. Neuroinflammation and alterations in the endocannabinoid system are involved in epileptogenesis and represent attractive targets for therapeutic interventions. Randomized placebo-controlled trials have shown that cannabidiol (CBD), one of the main active principles found in the Cannabis plant, significantly reduces seizure frequency in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). The FDA’s approval of a purified formulation of CBD (Epidiolex®) in 2018 marks a significant advance in the management of patients affected by these disorders. This review is focused on the activity of CBD as a neuroinflammatory modulator and antiseizure agent. Experimental evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies indicates that CBD reduces neuronal excitability and seizure activity by a wide range of mechanisms including, but not limited to, modulation of endocannabinoid, adenosine, GPR55, and TRPV1 receptors. It has also been shown that CBD’s molecular actions trigger immunomodulatory effects and inhibit neuroinflammation through reduced concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neurotoxic factors in microglia. We discuss the evidence for CBD’s effects on neuroinflammation, and their implications for inhibition of epileptogenesis and seizure activity. We highlight how further elucidation of CBD’s mechanisms of action, and particularly its effects on neuroinflammation, could lead to a more rational, targeted utilization of this compound, guided by assessment of biomarkers predictive of clinical response. Improved understanding of CBD’s immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects could also facilitate the design of controlled studies to confirm the potential value of this compound in the treatment of types of epilepsy beyond those for which regulatory approval has been already obtained.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic disease that affects approximately 65 million people, or about 1% of the world’s population (Reddy and Golub, 2016). Around 80% of individuals with epilepsy live in low- and middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2019), resulting in significant socioeconomic burden for health services and society in general. Epilepsy has a major impact on the quality of life of individuals and their families, particularly when seizures are not fully controlled. In fact, most patients report having a poor quality of life due to the unpredictability of seizures, the risk of associated injuries, and the adverse effects of antiseizure medications (ASMs) (Moya et al., 2015; García-Galicia et al., 2014; García-Peñas, 2015; Luoni et al., 2011).

In the long term, the prognosis of epilepsy is mainly determined by the underlying etiology, which can be related to structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, and immune causes (Scheffer et al., 2018). Early onset seizures are often associated with structural abnormalities visible on neuroimaging, which can have genetic (e.g., cortical developmental malformations, tuberous sclerosis) or acquired causes (e,g., ischemic injuries, trauma, infections) (Ochoa-Gómez et al., 2017; Ramos-Lizana, 2017). A study of 4,595 children found that more than 60% of epilepsies with seizure onset between 1 and 3 years of age had a structural cause, with the most prevalent etiologies being hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and tuberous sclerosis (Ochoa-Gómez et al., 2017; Pesantez et al., 2018). In adolescents and adults, focal epilepsies due to structural etiologies have also been correlated with a worse prognosis and greater probability of drug resistance, particularly in patients with comorbid conditions such as mental disability or psychiatric disorders (López González et al., 2015).

Despite the large number of available ASMs, about 30% of individuals with epilepsy do not achieve complete seizure control with pharmacological treatment (Kwan et al., 2010). This group of patients accounts for 80% of the cost of managing epilepsy (Begley et al., 2000). The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defines drug resistant epilepsy as “as failure of adequate trials of two tolerated, appropriately chosen and used antiepileptic drug schedules (whether as monotherapies or in combination) to achieve sustained seizure freedom.” Sustained seizure freedom is defined as a period of 1 year without seizures or, for individuals with infrequent seizures, a period without seizures three times longer than the longest interictal interval prior to treatment (Kwan et al., 2010). Having drug resistant epilepsy does not imply intractability, because many of these patients may achieve seizure freedom with epilepsy surgery or with other treatment options such as neurostimulation or dietary therapies (López González et al., 2015). Moreover, some patients with drug-resistant epilepsy can achieve complete seizure control after trying additional ASMs, either as monotherapy or in combination. In these patients, the probability of achieving seizure freedom decreases progressively with increasing number of ASMs previously tried without success (Mula et al., 2019).

Cannabidiol (CBD) is among the latest ASMs introduced into the therapeutic armamentarium, and it has been found valuable in improving seizure control in individuals with pharmacoresistant epilepsy. The present article provides a concise overview of mechanisms leading to drug resistance in epilepsy, with a special focus on the role of neuroinflammation, and the influence of CBD on these mechanisms. Evidence of clinical benefit achieved with CBD in difficult-to-treat epilepsies will also be briefly reviewed, together with a discussion of future perspectives for a more rational and potentially broader use of this compound in the treatment of seizure disorders.

Epileptogenesis and neuroinflammation

The mechanisms of drug resistance are multifactorial and are influenced by the patient’s age, the etiology of epilepsy, and previous treatments. More than 65% of patients with refractory epilepsy have an early onset of seizures (Moya et al., 2015), with a higher incidence in childhood, especially during the first year of life, where they often present complex clinical features, with infantile spasms and focal seizures predominating over generalized seizures (Ochoa-Gómez et al., 2017; Wilmshurst et al., 2015). Uncontrolled seizure activity can also lead to cognitive disorders (Pesantez et al., 2018; Cilio et al., 2014; Koo and Kang, 2017), particularly in patients in developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs) in whom a high burden of seizure activity can adversely affect neurodevelopment (Scheffer et al., 2018). To understand refractory epilepsy and its possible therapeutic targets, it is important to review the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the process of epileptogenesis.

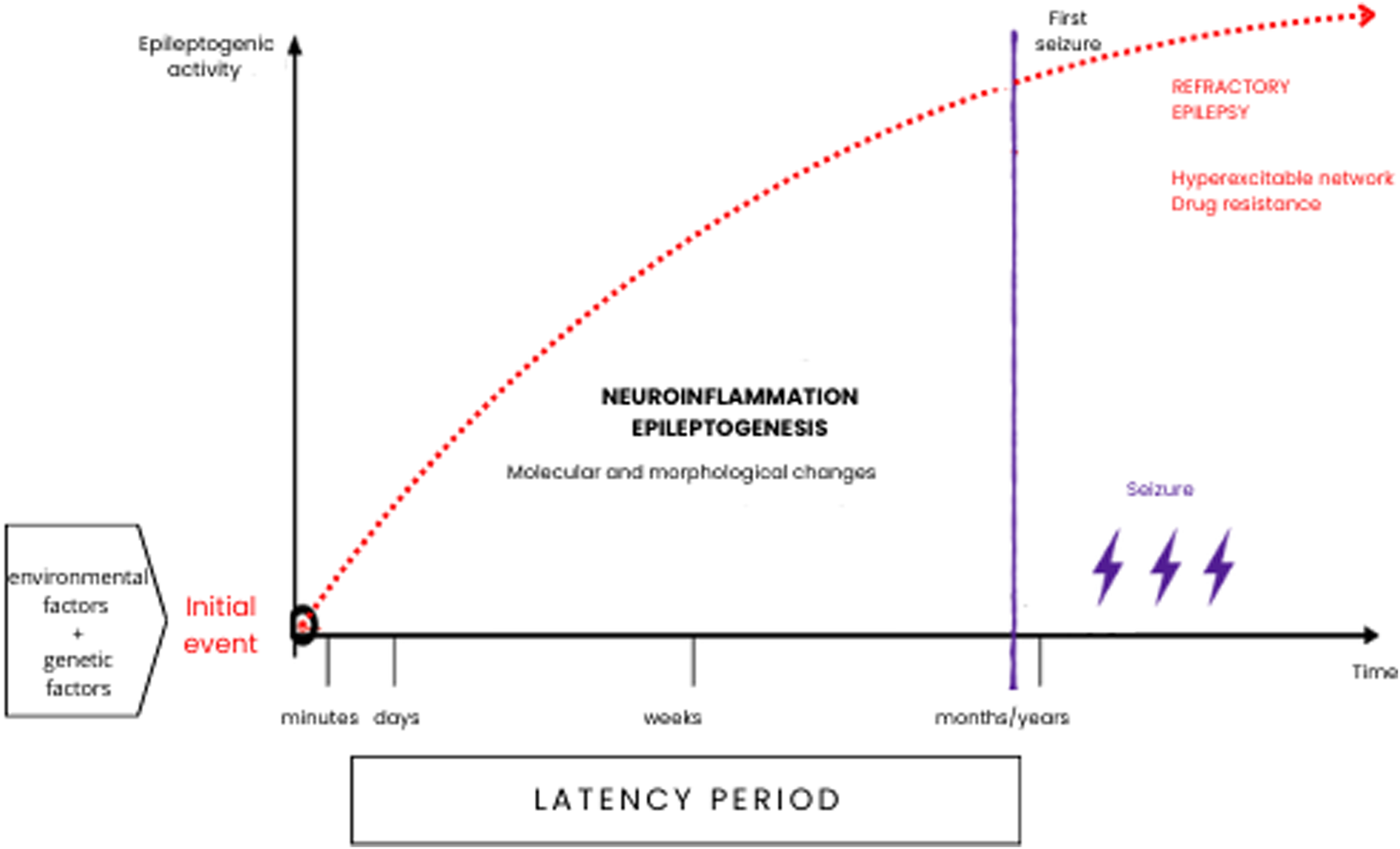

Long before the onset of the first seizure, there is a latent period, which can last for weeks, months or years during which neurobiological changes (epileptogenesis) gradually lead to the establishment of an epileptic condition (Figure 1). This period is characterized by a cascade of cellular and molecular events that can be triggered by various factors such as brain injury due to trauma, hypoxia, febrile seizures, infections, etc. Any of these factors, combined with a genetic predisposition, can trigger structural and/or functional changes that result in a hyperexcitable neuronal network capable of generating spontaneous epileptiform activity (Koepp et al., 2017; Rana and Musto, 2018), and subsequent onset of seizures and possible drug resistance (Suleymanova, 2021).

FIGURE 1

Epileptogenesis can occur throughout life and is a multifactorial process that, especially during infancy and early childhood. May have a genetic substrate, or it may be a secondary acquired process. Neuroinflammation and neuronal plasticity processes can cause morphological and molecular restructuring in neuronal circuits and play a fundamental role in the onset of seizure phenomena and drug resistance.

The process of epileptogenesis can be associated with a persistent inflammatory state in the neuronal microenvironment. This has been demonstrated in animal models of epilepsy where, after a critical insult, dendritic remodeling and synaptogenesis start to occur within 24 h. Microglial cells play a fundamental role in the initial proinflammatory response, releasing large amounts of cytokines detectable into the cerebrospinal fluid, such as interleukins IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), among others (Rana and Musto, 2018; Vezzani et al., 2015). These, in turn, stimulate the proliferation of astrocytes and increase the expression of IL-1β, which indirectly promotes the release of glutamate, decreasing its reuptake in the synaptic cleft and generating greater hyperexcitability, consequently activating mechanisms of excitotoxicity, necrosis, and apoptotic activity (Koepp et al., 2017; Rana and Musto, 2018; Pardo et al., 2014; Choi and Koh, 2008). Recent evidence suggests that neuroinflammatory processes play a crucial role in drug resistance, as proinflammatory cytokines can modulate neurotransmitter receptors and upregulate efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier, thereby reducing the efficacy of ASMs (Zabrodskaya et al., 2023; Vezzani et al., 2019).

Neuroinflammation is increasingly recognized as a shared mechanism that can contribute to the onset and persistence of seizures across multiple epilepsy syndromes. In animal models of infantile spasms and in several pediatric epileptic disorders, including Rasmussen encephalitis, infantile spasms, and FIRES, epileptogenic insults induce robust microglial activation, initiating sustained pro-inflammatory cascades and marked transcriptional changes. Beyond microglia, both neurons and astrocytes actively shape the inflammatory milieu through the release of cytokines, chemokines, and alarmins, thereby amplifying and perpetuating the neuroinflammatory response. These processes promote aberrant neurogenesis with mossy fiber sprouting, reactive gliosis, and alterations in the expression of GABAergic and glutamatergic receptors. Altogether, these neurobiological changes contribute to more severe and frequent seizures and are strongly associated with a higher level of refractoriness to antiseizure drug treatment (Pesantez et al., 2018; Pardo et al., 2014; Choi and Koh, 2008; Vezzani et al., 2019).

In temporal lobe epilepsy, increased levels of IL-1β and TNF-α have been reported, which could be associated with apoptotic cell death, excitotoxicity, necroptosis, and other regulated cell death pathways that contribute to the development of hippocampal sclerosis (Rana and Musto, 2018; Auvin et al., 2017; Vezzani et al., 2019). TNF-α increases the expression of AMPA receptors; promotes calcium uptake and amplifies glutamatergic transmission and number of glutamate receptors; it also induces endocytosis of GABA receptors, thereby reducing inhibition and promoting neurotoxicity and the maintenance of a hyperexcitable pathological network. This chronic hyperexcitability state also causes dynamic changes in the endocannabinoid system, mainly in the inhibitory homeostasis of CB1 receptors in the synaptic terminals of interneurons, causing prolonged disinhibition of the neural network (Rosenberg et al., 2015). In turn, IL-6 decreases long-term potentiation and neurogenesis in the hippocampus while increasing gliosis. All these conditions promote the maintenance of epilepsy and the onset of comorbidities. Sustained neuro inflammation has been linked to behavioral and cognitive comorbidities, including deficits in attention, memory, and emotional regulation, highlighting its systemic impact beyond seizure generation (Suleymanova, 2021; Rosenberg et al., 2017). Prolonged convulsive seizures, particularly convulsive status epilepticus, can also cause local biochemical and histological alterations around the primary seizure focus, which can lead to the appearance of new epileptogenic areas (secondary epileptogenesis). Altogether, these mechanistic insights provide a rationale for targeting glial signaling and endocannabinoid pathways early in the epileptogenic process.

The process of chronic neuroinflammation triggers cascades of immune responses, which may show clinical correlates. Evidence from human tissue supports this association: resected samples from focal structural epilepsies show marked glial activation and inflammatory signaling (Vezzani et al., 2015). Increased activation of IL-6 and MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) has been detected in patients with a history of epilepsy, compared to healthy controls. Additionally, increased pleocytosis without an active infectious process has also been reported in individuals who had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, suggesting a causal relationship between neuroinflammation and both the onset and the progression of epilepsy (Choi and Koh, 2008; Auvin et al., 2017).

The latency period preceding the onset of seizures represents an important therapeutic window, with neuroinflammation mechanisms and neural network hyperexcitability being attractive targets to prevent the development and progression of epilepsy (Vezzani et al., 2019). In a prospective study, Kotulska et al. (2021) used electroencephalography (EEG) to detect epileptiform abnormalities in infants with TSC before the onset of clinical or electrographic seizures. They found that the probability of achieving seizure freedom was greater among those infants with epileptiform EEG abnormalities who received vigabatrin treatment prior to the onset of clinical or electrographic seizures compared with those who started treatment after a first seizure (Kotulska et al., 2021). Of note, imaging studies in animal models of epileptogenesis have identified evidence of brain inflammation before seizure appearance (Koepp et al., 2017). The efficacy of immunotherapy and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in the treatment of infantile epileptic spasms syndrome could be due, at least in part to the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties of these compounds (Choi and Koh, 2008; Barker-Haliski et al., 2017).

Is brain inflammation a relevant target for the efficacy of CBD in epilepsy?

Although herbal remedies based on components of the Cannabis plant have been used in the treatment of seizures disorders since ancient times (Perucca, 2025), it is only in the last decade that adequate evidence of clinical efficacy has been obtained from randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials utilizing a pharmaceutical grade formulation of CBD (Epidiolex®) (Franco et al., 2021; Nabbout and Thiele, 2020). These trials showed that CBD is effective in improving seizure control when used as adjunctive therapy in patients with seizures associated with Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). The results of these trials ultimately led to the approval of Epidiolex® in the U.S, Europe and other countries for the treatment of seizures associated with these syndromes. Of note, many of the patients included in CBD trials were receiving concomitant treatment with clobazam. CBD inhibits the metabolic pathways of clobazam, leading to a 3.4 to 5-fold increase in the plasma concentration of the active metabolite N-desmethyl-clobazam (Nabbout and Thiele, 2020). While this interaction may contribute to the improved seizure control associated with CBD treatment and to some of its adverse effects, evidence has been if CBD does have an independent antiseizure effect (Bialer and Perucca, 2020).

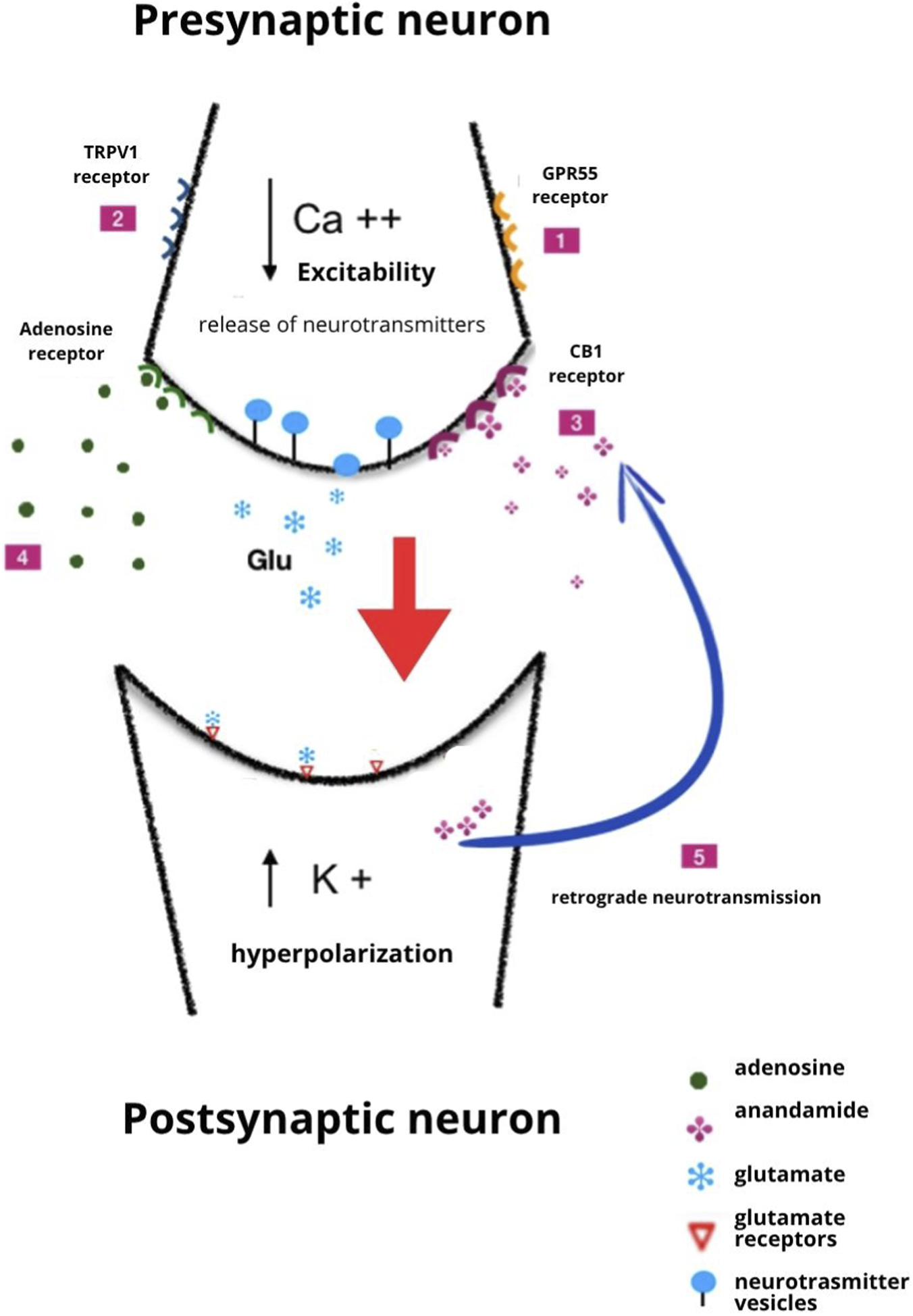

The mechanisms by which CBD inhibits seizure activity are probably multifactorial and incompletely understood. Some of those considered to be particularly relevant are shown in Figure 2, but many others could play a significant role. The difficulty in identifying the primary actions responsible for CBD antiseizure effects is related to the complexity of CBD pharmacology. A 2019 review listed 18 different mechanisms of action reported for CBD, and the list has become even longer in the last few years (Swenson, 2025).

FIGURE 2

Illustration of several potential mechanisms by which CBD exerts antiseizure activity. 1. Antagonist action at the GPR55 receptor; 2. Desensitization of the TRPV1 receptor; 3. Inhibition of the metabolism of anandamide; 4. Inhibition of adenosine reuptake; 5. Induction of retrograde neurotransmission and long-term depression. The mechanisms shown here are not exhaustive, and other actions can contribute to the effects of CBD. Of note, some of the mechanisms shown in the figure probably contribute to CBD’s immunomodulating and anti-inflammatory effects. Modified from Gray and Whalley (2020), licensed under CC BY-SA.

In addition to antiseizure activity, CBD possesses neuroprotective actions in a wide range of in vitro and in vivo experimental models. For example, in a rat model of transient global cerebral ischemia, CBD was effective in increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and in reducing ischemia-induced memory deficits, hippocampal CA1 neurodegeneration and deleterious changes in dendritic spine number and the length of dendritic arborization (Meyer et al., 2021). Similar results were obtained in a mouse model of brain ischemia induced by bilateral common carotid occlusion, where CBD reduced neuroinflammation and improved functional recovery (Mori et al., 2017). In a series of studies conducted in models of ischemic-hypoxic brain damage in newborn animals, CBD protected against tissue damage by modulating glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation (Pazos et al., 2012; Lafuente et al., 2016; Mohammed et al., 2017). In fact, modulation of inflammatory pathways in the central nervous system (CNS) is attracting considerable interest as one of the actions that could mediate CBD’s protecting effects against seizures (Cheung et al., 2019). This interest is justified not only by the studies discussed above linking neuroinflammation to epileptogenesis, epileptic activity and drug resistance, but also by evidence that dysfunction in endocannabinoid signaling can be implicated in epileptogenesis and brain inflammation (Cheung et al., 2019). Immunomodulating and anti-inflammatory effects of CBD in experimental models of injury to the brain or other organs have been demonstrated in many studies in addition to those mentioned above (Burstein, 2015; Yousaf et al., 2022). The protecting effects of CBD against brain inflammation take place at microglial level and lead to reduced concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neurotoxic factors in microglia (Yousaf et al., 2022). The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood and may vary across experimental conditions and models. Mechanisms considered to be potentially relevant for prevention or suppression of neuroinflammation include modulation of CB2 receptors (Yousaf et al., 2022; Pazos et al., 2013), potentiation of adenosine signalling (Yousaf et al., 2022; Car et al., 2006; Mecha et al., 2013), scavenging of free radicals (Yousaf et al., 2022), inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway and upregulation of the activation of the STAT3 transcription factor (Kozela et al., 2010; Dos-Santos-Pereira et al., 2020), modulation of the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway (Lima et al., 2020), modulation of nitric oxide synthetase (NOS) expression and activity (Hooshm et al., 2025), modulation of TRPV1 ion channels (Socała et al., 2024) and others (Burstein, 2015; Yousaf et al., 2022; Hartmann et al., 2023).

Several studies have explored the relationship between CBD effects on neuroinflammation and protection against epileptogenesis and seizure activity. In an elegant study in the mouse model of epileptogenesis induced by bilateral intra-hippocampal injection of pilocarpine, Lima et al. (2020) found that CBD (30, 60 or 90 mg/kg, i. p., administered 30 or 60 min before pilocarpine) increased the latency and reduced the severity of pilocarpine-induced behavioral seizures, and prevented postictal changes, such as neurodegeneration, microgliosis and astrocytosis. In parallel experiments, some of which included use of transgenic mice, the authors also provided evidence that the antiseizure and neuroprotective effects of CBD were mediated by modulation of the PI3K/mTOR signalling pathway, possibly secondary to CB1 receptor antagonism. In another study, different modes and timing of administration of artisanal CBD in a mouse model of seizures induced by i. p. Injection of kainate were used to determine CBD effects on seizures, microglial activation and aberrant seizure-related neurogenesis (Victor et al., 2022). Prolonged treatment with CBD had no major effects on seizures in that study, but it reduced histologically documented neuroinflammation in the hippocampus as well as the number of ectopic neurons in the hippocampus after a seizure. Based on these findings, the authors considered CBD as a potentially useful adjunctive treatment in interventions aimed at preventing epileptogenesis. Somewhat similar results have been reported recently in a genetic mouse model of CL2 disease (Dearborn et al., 2022). Animals treated with CBD orally for 6 months (100 mg/kg/day) showed decreased markers of astrocytosis and microgliosis, but no effects were seen on seizure frequency or neuron survival. Whether higher doses of CBD might have been effective to also reduce seizures and neurodegeneration is unclear. Overall, while evidence from animal studies does confirm an antagonistic action of CBD on neuroinflammation in seizure models, the role of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating mechanisms in mediating CDB’s antiseizure activity requires further evaluation.

Of note, evidence is now starting to emerge that CBD could be clinically beneficial in epileptic conditions where immune and inflammatory mechanisms are known to have a prominent role. Preliminary observations suggest that CBD can be valuable in the management of patients with refractory status epilepticus (Duda and Reinert, 2022), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) (Fetta et al., 2023), and Rasmussen syndrome (Prager et al., 2022). Additionally, a recent study in 8 adults with treatment resistant epilepsy (6 with focal epilepsy, one with idiopathic generalized epilepsy, and one with epilepsy undetermined whether focal or generalized) provided indirect evidence that CBD can reduce brain inflammation (Sharma and Szaflarski, 2024). Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging and thermometry (MRSI-t) was used as a biomarker of brain inflammation in these patients, based on the hypothesis that brain temperature elevation can serve as a surrogate marker for the biological processes associated with neuroinflammation. The study showed that patients had abnormally elevated peak temperatures within their seizure onset zone, and that these temperatures decreased significantly after 12 weeks of treatment with CBD (starting dose 5 mg/kg/day, maintenance dose not reported). CBD treatment was also associated with reduced seizure severity scores. While these results are consistent with the hypothesis of CBD reduces brain inflammation in patients with uncontrolled seizures, they should be interpreted cautiously because of many study limitations, including a small sample size, inclusion of patients with different types of epilepsy, lack of a randomized control group of patients with epilepsy not treated with CBD, and uncertainty about the validity of MRSI-t as a marker of neuroinflammation. Yet, the study highlights the potential value of assessing clinical biomarkers of brain inflammation, and their application in prospective clinical investigations on the mode of action of CBD.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The last decade has seen impressive advances in understanding the value of CBD in the management of epilepsy. High quality investigations in experimental models have demonstrated its antiseizure activity irrespective of use of concomitant medications (Devinsky et al., 2014; Friedman and Devinsky, 2015; Devinsky et al., 2024). Its clinical efficacy in the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and TSC has been established by randomized placebo-controlled trials, leading for the first time to international regulatory approval of pharmaceutical grade CBD (Franco et al., 2021; Nabbout and Thiele, 2020). Increasing evidence is also accumulating that CBD efficacy may extend to a wide range of other epileptic conditions, ranging from DEEs to other rare syndromes, as well as common focal and generalized epilepsies in children and adults (Pesántez Ríos et al., 2022; Pesántez Ríos et al., 2017; Kochen et al., 2023; Chemaly et al., 2025; Cerulli Irelli et al., 2025; Perulli et al., 2025; Hollander et al., 2025; Saranti et al., 2025; Reyes et al., 2025). Despite these advances, important unmet needs and questions remain to be addressed. Treatment with CBD remains based on a trial-and-error approach, and we do not have reliable measures to predict patients who will benefit from treatment. We also need more data on (and predictors of) the effect of CBD on epilepsy co-morbidities, which are particularly common in individuals with DEEs (Vasquez and Fine, 2025). We also need rigorous, well controlled studies to confirm the efficacy of CBD in a broader range of epileptic syndromes and disorders.

Further research on the mechanisms of action of CBD could provide valuable clues to address many of the unmet needs mentioned above. It would be important to determine to what extent CBD’s immunomodulating and anti-inflammatory actions in the CNS contribute to its therapeutic effects, and whether such contribution differs in relation to age, epilepsy syndrome, epilepsy etiology and other individual factors. Coupled with the development of biochemical, electrographic, and imaging biomarkers to reliably identify the presence of neuroinflammation (Aguilar-Castillo et al., 2024; Shoukair et al., 2025), this information could allow to predict which patients are more likely to benefit from CBD treatment. It could also be valuable in determining additional indications to be pursued in future regulatory trials, and in selecting patients to be enrolled in such trials. Further research is also indicated to determine CBD’s potential in preventing epileptogenesis through inhibition of neuroinflammation. The availability of in vivo biomarkers of neuroinflammation could be very useful in these studies and might guide patient selection should a clinical trial of epilepsy prevention (or disease modification) be designed.

Overall, there are many attractive perspectives for a more rational, targeted use of CBD in the future, both for approved indications and for off-label conditions where evidence-based use could be justified. One problem, particularly in Latin America and other resource-restricted settings, is that the availability of pharmaceutical grade CBD is limited, and its cost is prohibitive for some sectors of the population. Use of cheaper formulations of artisanal medical CBD could be valuable in these settings (Tzadok et al., 2022; Pietrafusa et al., 2019). Due to the increased interest of caregivers in the use of Cannabis-derived products for the treatment of epilepsy, a pilot study was conducted in Ecuador since 2015 to evaluate the value of low doses of pure CBD added to pre-existing ASMs in the treatment of patients with severe epilepsies. After at least 12 months of treatment, the study reported significant reduction in seizure frequency, duration and intensity, and many patients showed neurocognitive improvements (Pesántez Ríos et al., 2022; Pesántez Ríos et al., 2017). While these data are encouraging, when using non-pharmaceutical grade CBD, it is important to be aware that the quality of products in the market, many of which can be purchased online, can be extremely variable. Studies conducted in the U.S. and other countries have clearly shown for some products the actual CBD content may differ wildly from that stated in the label, and some products may even be contaminated by pollutants (Pavlovic et al., 2018; Gurley et al., 2020; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2025). If non-pharmaceutical grade of CBD is not accessible or affordable, physicians and caregivers should ensure that the alternative product used is obtained from verifiable sources and meets adequate quality standards in terms of CBD content, stability and purity.

Statements

Author contributions

GP: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. EP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. PS: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. RC: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. XP: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. SP: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. GP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

Part of this research was carried out during author GP’s doctoral training in the Neurosciences Program at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), Madrid, Spain. EP received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Eisai, GRIN Therapeutics, SK Life Science, Sun Pharma, Takeda, UCB Pharma and Xenon Pharma and royalties from Wiley and Elsevier, outside of the submitted work. PS has served on scientific advisory boards for Angelini Pharma, UCB, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Ethypharm, Biomarin, and has received speaker honoraria from Angelini Pharma, UCB, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer AV declared a past co-authorship with the author(s) PS to the handling editor.

The author PS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aguilar-Castillo M. J. Cabezudo-García P. García-Martín G. Lopez-Moreno Y. Estivill-Torrús G. Ciano-Petersen N. L. et al (2024). A systematic review of the predictive and diagnostic uses of neuroinflammation biomarkers for epileptogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25 (12), 6488. 10.3390/ijms25126488

2

Auvin S. Walker L. Gallentine W. Jozwiak S. Tombini M. Sills G. J. (2017). Prospective clinical trials to investigate clinical and molecular biomarkers. Epilepsia58, 20–26. 10.1111/epi.13782

3

Barker-Haliski M. L. Löscher W. White H. S. Galanopoulou A. S. (2017). Neuroinflammation in epileptogenesis: insights and translational perspectives from new models of epilepsy. Epilepsia58, 39–47. 10.1111/epi.13785

4

Begley C. E. Famulari M. Annegers J. F. Lairson D. R. Reynolds T. F. Coan S. et al (2000). The cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey data. Epilepsia41 (3), 342–351. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00166.x

5

Bialer M. Perucca E. (2020). Does cannabidiol have antiseizure activity independent of its interactions with clobazam? An appraisal of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Epilepsia61 (6), 1082–1089. 10.1111/epi.16542

6

Burstein S. (2015). Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: a review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorg Med. Chem.23 (7), 1377–1385. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.059

7

Carrier E. J. Auchampach J. A. Hillard C. J. (2006). Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter by cannabidiol: a mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.103 (20), 7895–7900. 10.1073/pnas.0511232103

8

Cerulli Irelli E. Mazzeo A. Caraballo R. H. Perulli M. Moloney P. B. Peña-Ceballos J. et al (2025). Expanding the therapeutic role of highly purified cannabidiol in monogenic epilepsies: a multicenter real-world study. Epilepsia66 (7), 2253–2267. 10.1111/epi.18378

9

Chemaly N. Kuchenbuch M. Losito E. Kaminska A. Coste-Zeitoun D. Barcia G. et al (2025). Assessing real world efficacy, safety, and 18-month retention rates of cannabidiol in individuals with drug resistant epilepsies. Eur. J. Neurol.32 (9), e70304. 10.1111/ene.70304

10

Cheung K. A. K. Peiris H. Wallace G. Holland O. J. Mitchell M. D. (2019). The interplay between the endocannabinoid system, epilepsy and cannabinoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20 (23), 6079. 10.3390/ijms20236079

11

Choi J. Koh S. (2008). Role of brain inflammation in epileptogenesis. Yonsei Med. J.49 (1), 1–18. 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.1.1

12

Cilio M. R. Thiele E. A. Devinsky O. (2014). The case for assessing cannabidiol in epilepsy. Epilepsia55 (6), 787–790. 10.1111/epi.12635

13

Dearborn J. T. Nelvagal H. R. Rensing N. R. Takahashi K. Hughes S. M. Wishart T. M. et al (2022). Effects of chronic cannabidiol in a mouse model of naturally occurring neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and spontaneous seizures. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 11286. 10.1038/s41598-022-15134-5

14

Devinsky O. Cilio M. R. Cross H. Fernandez-Ruiz J. French J. Hill C. et al (2014). Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia55 (6), 791–802. 10.1111/epi.12631

15

Devinsky O. Jones N. A. Cunningham M. O. Jayasekera B. A. P. Devore S. Whalley B. J. (2024). Cannabinoid treatments in epilepsy and seizure disorders. Physiol. Rev.104 (2), 591–649. 10.1152/physrev.00049.2021

16

Dos-Santos-Pereira M. Guimarães F. S. Del-Bel E. Raisman-Vozari R. Michel P. P. (2020). Cannabidiol prevents LPS-Induced microglial inflammation by inhibiting ROS/NF-κB-dependent signaling and glucose consumption. Glia68 (3), 561–573. 10.1002/glia.23738

17

Duda J. Reinert J. P. (2022). Cannabidiol in refractory status epilepticus: a review of clinical experiences. Seizure103, 115–119. 10.1016/j.seizure.2022.11.006

18

Fetta A. Crotti E. Campostrini E. Bergonzini L. Cesaroni C. A. Conti F. et al (2023). Cannabidiol in the acute phase of febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). Epilepsia Open8 (2), 685–691. 10.1002/epi4.12740

19

Franco V. Perucca E. (2019). Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of cannabidiol for epilepsy. Drugs79 (13), 1435–1454. 10.1007/s40265-019-01171-4

20

Franco V. Bialer M. Perucca E. (2021). Cannabidiol in the treatment of epilepsy: current evidence and perspectives for further research. Neuropharmacology185, 108442. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108442

21

Friedman D. Devinsky O. (2015). Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med.373, 1048–1058. 10.1056/NEJMra1407304

22

García-Galicia A. García-Carrasco M. Montiel-Jarquín Á. J. García-Cuautitla M. A. Barragán-Hervella R. G. Romero-Figueroa M. S. (2014). Validez y consistencia de las escalas ECAVIPEP y CAVE para evaluar la calidad de vida en pacientes pediátricos con epilepsia. Rev. Neurol.59 (7), 301–306. 10.33588/rn.5907.2014241

23

García-Peñas J. J. (2015). Fracaso escolar y epilepsia infantil. 60(Suppl. 1):63–68.

24

Gray R. A. Whalley B. J. (2020). The proposed mechanism of action of CBD in epilepsy. Epileptic Disord.22, 10–15. 10.1684/epd.2020.1135

25

Gurley B. J. Murphy T. P. Gul W. Walker L. A. ElSohly M. (2020). Content versus label claims in cannabidiol (CBD)-Containing products obtained from commercial outlets in the state of Mississippi. J. Diet. Suppl.17 (5), 599–607. 10.1080/19390211.2020.1766634

26

Hartmann A. Vila-Verde C. Guimarães F. S. Joca S. R. Lisboa S. F. (2023). The NLRP3 inflammasome in stress response: another target for the promiscuous cannabidiol. Curr. Neuropharmacol.21 (2), 284–308. 10.2174/1570159X20666220411101217

27

Hollander M. Mayer T. Klotz K. A. Knake S. von Podewils F. Kurlemann G. et al (2025). Use of cannabidiol for off-label treatment of patients with refractory focal, genetic generalised and other epilepsies. Neurol. Res. Pract.7 (1), 49. 10.1186/s42466-025-00408-w

28

Hooshmand S. A. A. Rameshrad M. Sahebkar A. Iranshahi M. (2025). The effects of cannabidiol on nitric oxide synthases: a narrative review on therapeutic implications for inflammation and oxidative stress in health and disease. J. Cannabis Res.7 (1), 71. 10.1186/s42238-025-00332-5

29

Kochen S. Villanueva M. Bayarres L. Daza-Restrepo A. Gonzalez Martinez S. Oddo S. (2023). Cannabidiol as an adjuvant treatment in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav.144, 109210. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109210

30

Koepp M. J. Årstad E. Bankstahl J. P. Dedeurwaerdere S. Friedman A. Potschka H. et al (2017). Neuroinflammation imaging markers for epileptogenesis. Epilepsia58, 11–19. 10.1111/epi.13778

31

Koo C. M. Kang H.-C. (2017). Could cannabidiol be a treatment option for intractable childhood and adolescent epilepsy. J. Epilepsy Res.7 (1), 16–20. 10.14581/jer.17003

32

Kotulska K. Kwiatkowski D. J. Curatolo P. Weschke B. Riney K. Jansen F. et al (2021). Prevention of epilepsy in infants with Tuberous Sclerosis complex in the EPISTOP trial. Ann. Neurol.89, 304–314. 10.1002/ana.25956

33

Kozela E. Pietr M. Juknat A. Rimmerman N. Levy R. Vogel Z. (2010). Cannabinoids Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol differentially inhibit the lipopolysaccharide-activated NF-kappaB and interferon-beta/STAT proinflammatory pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. J. Biol. Chem.285 (3), 1616–1626. 10.1074/jbc.M109.069294

34

Kwan P. Arzimanoglou A. Berg A. T. Brodie M. J. Allen Hauser W. Mathern G. et al (2010). Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia51 (6), 1069–1077. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x

35

Lafuente H. Pazos M. R. Alvarez A. Mohammed N. Santos M. Arizti M. et al (2016). Effects of cannabidiol and hypothermia on short-term brain damage in new-born piglets after acute hypoxia-ischemia. Front. Neurosci.10, 323. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00323

36

Lima I. V. A. Bellozi P. M. Q. Batista E. M. Vilela L. R. Brandão I. L. Ribeiro F. M. et al (2020). Cannabidiol anticonvulsant effect is mediated by the PI3Kγ pathway. Neuropharmacology176, 108156. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108156

37

López González F. J. Rodríguez Osorio X. Gil-Nagel Rein A. Carreño Martínez M. Serratosa Fernández J. Villanueva Haba V. et al (2015). Drug-resistant epilepsy: definition and treatment alternatives. Neurol30 (7), 439–446. 10.1016/j.nrl.2014.04.012

38

Luoni C. Bisulli F. Canevini M. P. De Sarro G. Fattore C. Galimberti C. A. et al (2011). Determinants of health-related quality of life in pharmacoresistant epilepsy: results from a large multicenter study of consecutively enrolled patients using validated quantitative assessments. Epilepsia52 (12), 2181–2191. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03325.x

39

Mecha M. Feliú A. Iñigo P. M. Mestre L. Carrillo-Salinas F. J. Guaza C. (2013). Cannabidiol provides long-lasting protection against the deleterious effects of inflammation in a viral model of multiple sclerosis: a role for A2A receptors. Neurobiol. Dis.59, 141–150. 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.06.016

40

Meyer E. Bonato J. M. Mori M. A. Mattos B. A. Guimarães F. S. Milani H. et al (2021). Cannabidiol confers neuroprotection in rats in a model of transient global cerebral ischemia: impact of hippocampal synaptic neuroplasticity. Mol. Neurobiol.58 (10), 5338–5355. 10.1007/s12035-021-02479-7

41

Mohammed N. Ceprian M. Jimenez L. Pazos M. R. Martínez-Orgado J. (2017). Neuroprotective effects of cannabidiol in hypoxic ischemic insult. The therapeutic window in newborn mice. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets16 (1), 102–108. 10.2174/1871527315666160927110305

42

Mori M. A. Meyer E. Soares L. M. Milani H. Guimarães F. S. de Oliveira R. M. W. (2017). Cannabidiol reduces neuroinflammation and promotes neuroplasticity and functional recovery after brain ischemia. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry.75, 94–105. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.11.005

43

Moya J. Gómez V. Devilat M. (2015). Calidad de Vida en Niños con Epilepsia Resistente. Rev. Chil. Epilepsia. (1), 12–25.

44

Mula M. Zaccara G. Galimberti C. A. Ferrò B. Canevini M. P. Mascia A. et al (2019). Validated outcome of treatment changes according to international league against epilepsy criteria in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsia60 (6), 1114–1123. 10.1111/epi.14685

45

Nabbout R. Thiele E. A. (2020). The role of cannabinoids in epilepsy treatment: a critical review of efficacy results from clinical trials. Epileptic Disord.22 (S1), S23–S28. 10.1684/epd.2019.1124

46

Ochoa-Gómez L. López-Pisón J. Lapresta Moros C. Fuertes Rodrigo C. Fernando Martínez R. Samper-Villagrasa P. et al (2017). Estudio de las epilepsias según la edad de inicio, controladas durante 3 años en una unidad de neuropediatría de referencia regional. An Pediatr86 (1), 11–19. 10.1016/j.anpedi.2016.05.002

47

Pardo C. A. Nabbout R. Galanopoulou A. S. (2014). Mechanisms of epileptogenesis in pediatric epileptic syndromes: Rasmussen encephalitis, infantile spasms, and febrile Infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). Neurotherapeutics11 (2), 297–310. 10.1007/s13311-014-0265-2

48

Pavlovic R. Nenna G. Calvi L. Panseri S. Borgonovo G. Giupponi L. et al (2018). Quality traits of “cannabidiol oils”: cannabinoids content, terpene fingerprint and oxidation stability of European commercially available preparations. Molecules23 (5), 1230. 10.3390/molecules23051230

49

Pazos M. R. Cinquina V. Gómez A. Layunta R. Santos M. Fernández-Ruiz J. et al (2012). Cannabidiol administration after hypoxia-ischemia to newborn rats reduces long-term brain injury and restores neurobehavioral function. Neuropharmacology63 (5), 776–783. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.034

50

Pazos M. R. Mohammed N. Lafuente H. Santos M. Martinez-Pinilla E. Moreno E. et al (2013). Mechanisms of cannabidiol neuroprotection in hypoxic-ischemic newborn pigs: role of 5HT(1A) and CB2 receptors. Neuropharmacology71, 282–291. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.027

51

Perucca E. (2025). Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy: hard evidence at last? J. Epilepsy Res.7, 61–76.

52

Perulli M. Bianchetti M. Pantalone G. Quintiliani M. Gambardella M. L. Picilli M. et al (2025). Real-world efficacy and safety of cannabidiol in developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsia Open, epi4.70149. 10.1002/epi4.70149

53

Pesantez R. G. Jimbo Sotomayor R. Sánchez Choez X. Valencia C. Curatolo P. Pesantez Cuesta G. (2018). Tuberous sclerosis in Ecuador. Case series report. Neurol. Argent.10 (2), 66–71. 10.1016/j.neuarg.2017.10.002

54

Pesántez Ríos G. Armijos-Acurio L. Jimbo-Sotomayor R. Pascual-Pascual S. I. Pesántez-Cuesta G. (2017). Cannabidiol: its use in refractory epilepsies. Rev. Neurol.65 (4), 157–160. 10.33588/rn.6504.2016573

55

Pesántez Ríos G. Armijos Acurio L. Jimbo Sotomayor R. Cueva V. Pesántez Ríos X. Navarrete Zambrano H. et al (2022). A pilot study on the use of low doses of CBD to control seizures in rare and severe forms of drug-resistant epilepsy. Life (Basel)12, 2065. 10.3390/life12122065

56

Pietrafusa N. Ferretti A. Trivisano M. de Palma L. Calabrese C. Carfì P. G. et al (2019). Purified cannabidiol for treatment of refractory epilepsies in pediatric patients with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Paediatr. Drugs21 (4), 283–290. 10.1007/s40272-019-00341-x

57

Prager C. Kühne F. Tietze A. Kaindl A. M. (2022). Is cannabidiol worth a trial in rasmussen encephalitis?Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol.37, 53–55. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2022.01.008

58

Ramos-Lizana J. (2017). Encefalopatías epilépticas. Rev. Neurol.64 (Suppl. 3), S45–S48.

59

Rana A. Musto A. E. (2018). The role of inflammation in the development of epilepsy. Neuroinflammation15, 144. 10.1186/s12974-018-1192-7

60

Reddy D. S. Golub V. M. (2016). The pharmacological basis of cannabis therapy for epilepsy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.357 (1), 45–55. 10.1124/jpet.115.230151

61

Reyes V. G. Espeche A. Fortini S. Gamboni B. Adi J. Semprino M. et al (2025). A multicenter study on the use of purified cannabidiol for children with treatment-resistant developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsy Behav.171, 110590. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2025.110590

62

Rosenberg E. C. Tsien R. W. Whalley B. J. Devinsky O. (2015). Cannabinoids and epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics12 (4), 747–768. 10.1007/s13311-015-0375-5

63

Rosenberg E. C. Louik J. Conway E. Devinsky O. Friedman D. (2017). Quality of life in childhood epilepsy in pediatric patients enrolled in a prospective, open-label clinical study with cannabidiol. Epilepsia58 (8), e96–e100. 10.1111/epi.13815

64

Saranti A. Dragoumi P. Pavlogiannis K. Pavlou E. Zafeiriou D. (2025). Efficacy and safety of cannabidiol in children with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies: a systematic review. Seizure133, 114–127. 10.1016/j.seizure.2025.10.001

65

Scheffer I. E. Berkovic S. Capovilla G. Connolly M. B. Guilhoto L. Hirsch E. et al (2018). ILAE cassification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. 58(4):512–521.

66

Sharma A. A. Szaflarski J. P. (2024). The longitudinal effects of cannabidiol on brain temperature in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav.151, 109606. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109606

67

Shoukair D. H. Majzoub R. E. Kassem M. Ismail A. Safadieh G. Kotaich J. et al (2025). Identification of neuro-inflammatory biomarkers through non-invasive advanced neuroimaging techniques in pharmaco-resistant epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav.171, 110641. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2025.110641

68

Socała K. Jakubiec M. Abram M. Mlost J. Starowicz K. Kamiński R. M. et al (2024). TRPV1 channel in the pathophysiology of epilepsy and its potential as a molecular target for the development of new antiseizure drug candidates. Prog. Neurobiol.240, 102634. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2024.102634

69

Suleymanova E. M. (2021). Behavioral comorbidities of epilepsy and neuroinflammation: evidence from experimental and clinical studies. Epilepsy Behav.117, 107869. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107869

70

Swenson K. (2025). Beyond the hype: a comprehensive exploration of CBD's biological impacts and mechanisms of action. J. Cannabis Res.7 (1), 24. 10.1186/s42238-025-00274-y

71

Tzadok M. Hamed N. Heimer G. Zohar-Dayan E. Rabinowicz S. Ben Zeev B. (2022). The long-term effectiveness and safety of cannabidiol-enriched oil in children with drug-resistant epilepsy. Pediatr. Neurol.136, 15–19. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.06.016

72

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2025). Warning letters for cannabis-derived products. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/warning-letters-cannabis-derived-products (Accessed November 4, 2025).

73

Vasquez A. Fine A. L. (2025). Management of developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Semin. Neurol.45 (2), 206–220. 10.1055/a-2534-3267

74

Vezzani A. Lang B. Aronica E. (2015). Immunity and inflammation in epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med.18 (2), a022699. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022699

75

Vezzani A. Balosso S. Ravizza T. (2019). Neuroinflammatory pathways as treatment targets and biomarkers in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol.15 (8), 459–472. 10.1038/s41582-019-0217-x

76

Victor T. R. Hage Z. Tsirka S. E. (2022). Prophylactic administration of cannabidiol reduces microglial inflammatory response to kainate-induced seizures and neurogenesis. Neuroscience500, 1–11. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.06.010

77

Wilmshurst J. M. Gaillard W. D. Vinayan K. P. Tsuchida T. N. Plouin P. Van Bogaert P. et al (2015). Summary of recommendations for the management of infantile seizures: task force report for the ILAE commission of pediatrics. Epilepsia56 (8), 1185–1197. 10.1111/epi.13057

78

World Health Organization (2019). Epilepsy: a public health imperative. Geneva.

79

Yousaf M. Chang D. Liu Y. Liu T. Zhou X. (2022). Neuroprotection of cannabidiol, its synthetic derivatives and combination preparations against microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Molecules27 (15), 4961. 10.3390/molecules27154961

80

Zabrodskaya Y. Paramonova N. Litovchenko A. Bazhanova E. Gerasimov A. Sitovskaya D. et al (2023). Neuroinflammatory dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier and basement membrane dysplasia play a role in the development of drug-resistant epilepsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (16), 12689. 10.3390/ijms241612689

Summary

Keywords

cannabidiol, drug-resistant epilepsy, epileptogenesis, Immunomodulation, neuroinflammation, seizures

Citation

Pesántez Ríos G, Perucca E, Striano P, Caraballo R, Pesántez Ríos X, Pascual-Pascual SI and Pesántez Cuesta G (2026) Epilepsy, neuroinflammation and cannabidiol What do we know thus far? . Front. Pharmacol. 16:1749260. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1749260

Received

18 November 2025

Revised

09 December 2025

Accepted

12 December 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Alberto Lazarowski, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Reviewed by

Annamaria Vezzani, Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research (IRCCS), Italy

Silvia Oddo, Hospital EL Cruce, Argentina

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Pesántez Ríos, Perucca, Striano, Caraballo, Pesántez Ríos, Pascual-Pascual and Pesántez Cuesta.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Galo Pesántez Cuesta, cnepilepsia@gmail.com

ORCID: Roberto Caraballo, orcid.org/0000-0003-0259-1046

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.