- 1M.D. Department of Gastroenterology, Jiaxing Second Hospital, Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

- 2Changsha Medical University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3M.D. Department of Gastroenterology, The Second People’s Hospital of Quzhou, Quzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 4M.D. Department of Education, International Word, Quzhou People′s Hospital, The Quzhou Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Quzhou, Zhejiang, China

Background: Patients with stage III–IV colorectal cancer (CRC) face poor prognosis due to metastases and limited treatment options. In China, cinobufacini capsules are widely used as a complementary medicine, but evidence for their clinical value remains insufficient.

Methods: Systematic searches were conducted across seven databases, including Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), WanFang Database, China Biological Medicine Database (CBM), PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science, from their inception to 30 June 2025. The primary outcome was disease control rate (DCR), and the secondary outcomes were objective response rate (ORR), CD4+ T cells, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA-125), and adverse reactions. This study strictly followed the PRISMA guidelines and used RevMan 5.3, Stata 15, and GRADEpro for data analysis.

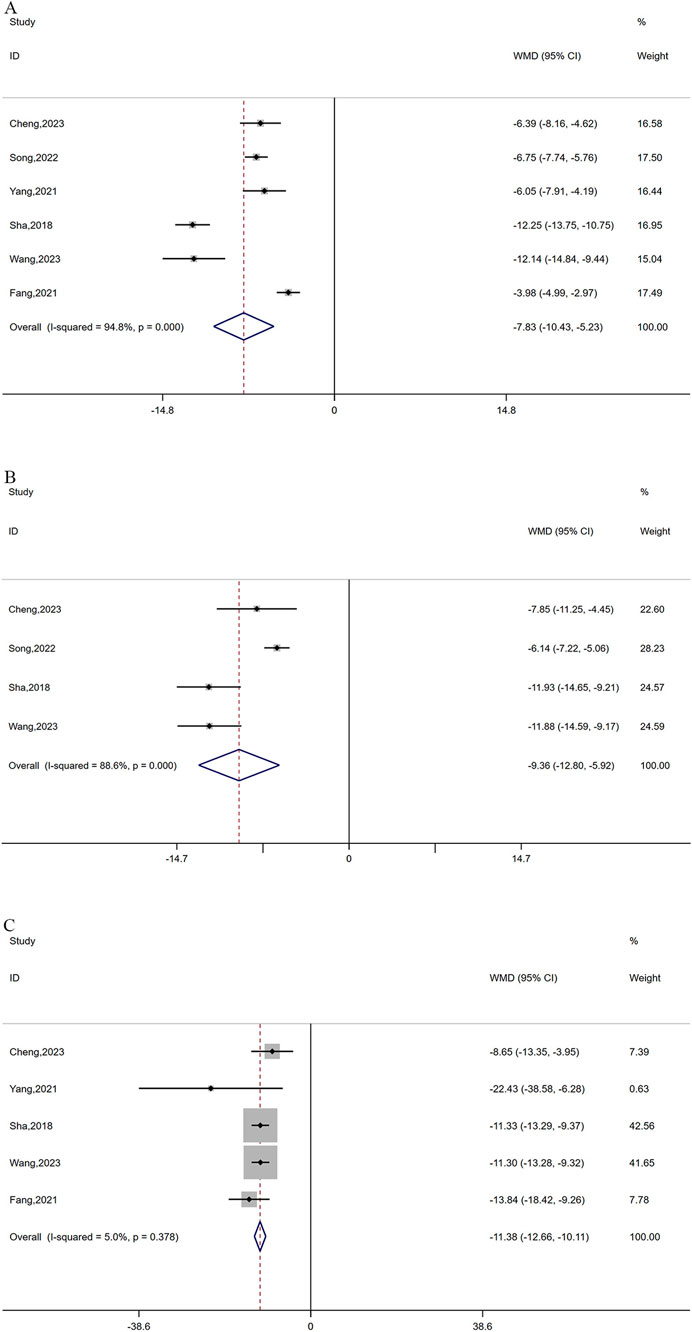

Results: The analysis showed that the combination therapy resulted in a higher DCR (RR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.10–1.25; P < 0.0001) and ORR (RR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.23–1.60; P < 0.0001), reduced CEA levels (WMD = −7.84, 95% CI: −10.43 to −5.23; P < 0.0001), CA-125 levels (WMD = −9.36, 95% CI: −12.80 to −5.92; P < 0.0001), and CA19-9 levels (WMD = −11.38, 95% CI: −12.66 to −10.11; P < 0.0001), as well as higher CD4+ T-cell levels (WMD = 2.74, 95% CI: 1.99–3.49; P < 0.0001). Additionally, the combination therapy could decrease the incidence of adverse reactions including leukocyte toxicity (RR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.48–0.71; P < 0.0001), gastrointestinal toxicity (RR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.62–0.99; P = 0.03), and myelosuppression (RR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.46–0.92; P = 0.01). The level of evidence was assessed as moderate for DCR and low for ORR.

Conclusion: Cinobufacini combined with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy may enhance short-term efficacy, immune function, and safety in advanced CRC. However, due to limitations of existing RCTs, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, and further large-scale, high-quality trials are required.

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related death, following lung cancer, accounting for approximately 9.4% of cancer mortality (Alese et al., 2023; Strickler et al., 2022). In 2023, there were approximately 153,020 newly diagnosed CRC patients in America alone, with an estimated death toll of 52,550 (Siegel et al., 2023). Among new cases of colorectal cancer, approximately 20% present with metastasis, and more than 60% of those under 50 years old are diagnosed at an advanced stage (Tumor–Node–Metastasis [TNM] stages III–IV) (Biller and Schrag, 2021; Fass et al., 2020). Furthermore, the prognosis of CRC varies significantly across different tumor stages (Hernandez Dominguez et al., 2023). Stage I patients have a 90% 5-year survival rate, while stage IV patients have a significantly lower rate of only 15.1% due to the limited treatment options and the burden of therapy-resistant, metastasis-competent cancer cells (Hernandez Dominguez et al., 2023; Weng and Goel, 2022; Shin et al., 2023). Given the high mortality and the trend of younger individuals being affected in CRC, early detection and intervention are increasingly recognized as critical components in the management of CRC (Patel et al., 2022). Owing to limited screening awareness and the insidious nature of CRC, many individuals are already at advanced stages when symptoms such as chronic abdominal pain, hematochezia, and anemia appear, thereby missing the opportunity for surgical intervention. For the majority of patients with advanced colorectal cancer, first-line treatment typically involves oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimens, including capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX), leucovorin (folinic acid), 5-fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), leucovorin (folinic acid), 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI), or leucovorin (folinic acid), 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) (Innocenti et al., 2021). These regimens could be used as monotherapy or in conjunction with targeted therapy or immunotherapy drugs tailored to the patient’s molecular subtypes, aiming to extend overall survival (Biller and Schrag, 2021; Feria and Times, 2024). However, oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, a cornerstone in the treatment of colorectal cancer, is commonly associated with hematological toxicities, gastrointestinal adverse events, and cumulative peripheral neurotoxicity (Biller and Schrag, 2021; Kokotis et al., 2016). These adverse reactions weaken the patient’s immune function, degrade their quality of life, and increase the risk of interrupting the continuity of treatment (Zraik and Heß-Busch, 2021). Complicating matters further, many advanced CRC patients also grapple with cachexia—a condition characterized by muscle wasting, weakness, and fatigue. This prevalent condition, observed in 50%–61% of CRC cases, independently reduces overall survival (OS) (Kasprzak, 2021). It is crucial to note that chemotherapy could exacerbate the symptoms of cachexia, creating a vicious cycle that further impacts the prognosis of patients (Ferrer et al., 2023). Therefore, there is a recognized need for additional treatments to prolong the survival outcomes and decrease the toxicity of chemotherapy for patients with advanced CRC.

Cinobufacini, also known as Huachansu in Chinese, is a single-herb traditional Chinese medicine preparation extracted from the dried skin of the toad Bufo gargarizans Cantor (family Bufonidae). It is formulated as an oral capsule, with bufadienolides (such as bufalin, cinobufagin, and resibufogenin) identified as the principal bioactive antitumor components (Zhan X. et al., 2020; Li R. et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2017). A randomized controlled study revealed that incorporating cinobufacini capsules (CC) into the first-line treatment for postoperative patients with stage II-III CRC could extend the average 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) by approximately 4 months (L et al., 2023). This treatment approach also resulted in a decrease in adverse reactions, including leukopenia, neutropenia, and diarrhea. Furthermore, supportive evidence from a recent breast cancer meta-analysis suggests that CC may have the effect of prolonging life and improving chemotherapy tolerance (Wu et al., 2025). Currently, cinobufacini capsules have been approved by the China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) as complementary agents in various cancers, including but not limited to liver cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and colorectal cancer; however, they are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency and are regarded as complementary or alternative medicine. In addition, with the growing research interest in cinobufacini in recent years, it is necessary to systematically evaluate its overall efficacy in colorectal cancer. Thus, this meta-analysis seeks to provide a comprehensive evaluation of cinobufacini capsules in treating advanced CRC, offering a new supplementary approach for patients in need.

2 Materials and methods

The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024529353). The registered outcomes were retained, with the only protocol modification being an extension of the literature search end date to 30 June 2025. Ethical approval was not required as this study used published data only.

2.1 Database searching

A comprehensive search strategy was employed to retrieve relevant studies from seven literature databases, including Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), WanFang Database, China Biological Medicine Database (CBM), PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, and Web of Science (WOS). The search period ranged from the inception of each database to 30 June 2025. The search terms listed in Table 1 were used for English databases, while the corresponding Chinese terminology was utilized when searching Chinese databases.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) design; patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed stage III or IV colorectal cancer; comparison between oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy alone and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy combined with oral cinobufacini capsules; and comparable baseline characteristics between treatment groups. Eligible studies were required to report at least one relevant clinical outcome, including disease control rate (DCR) or objective response rate (ORR), as well as immunological indices, tumor markers, or treatment-related adverse events.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they were duplicate publications, had incomplete or unclear data, or insufficiently described interventions. Non-randomized studies were excluded, as were studies involving patients without clearly defined stage III or IV colorectal cancer. Trials in which cinobufacini was administered via non-oral routes were also excluded.

2.4 Quality assessment and data extraction

Two qualified researchers independently extracted relevant data from studies that met the inclusion criteria, including authors, year of publication, sample size, tumor response criteria, interventions, duration, and outcomes. The risk of bias in these studies was assessed using the Cochrane collaboration tool, including evaluations of the study’s randomization process, implementation of blinding, integrity of trial data, selective reporting of results, and other biases. The studies were categorized as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements regarding data extraction and assessment of bias risk were resolved by the corresponding author.

2.5 Data analysis

The data extracted from the studies were analyzed using RevMan 5.3 and Stata 15 software. For dichotomous data, Risk Ratios (RR) were employed as measures of effect size, while continuous data were represented by weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardized mean difference (SMD). Each effect size was expressed as a 95% confidence interval (CI). A fixed-effects analysis model was utilized when heterogeneity was at or below 50% (I2 ≤ 50%), and a random-effects model was adopted for I2 > 50%. If there was significant heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was used to assess the stability of the results. If the studies included for the outcome indicator were ≥10, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Begg’s/Egger’s test. Meta-regression analysis was employed to assess the influence of various factors on the outcomes. The quality of evidence was assessed using GRADE software.

3 Results

3.1 Search results and study characteristics

As depicted in Figure 1, the literature search spanned several databases, including WOS, CNKI, WanFang, PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and CBM, resulting in a total of 267 records. After removing 138 duplicate entries, screening of titles and abstracts excluded 87 articles, leaving 42 for full-text review. Among these, thirty studies were further excluded for reasons including not being RCTs, not involving stage III-IV colorectal cancer, using non-oral drugs, or having unclear intervention descriptions. Finally, twelve studies (Yang and Peng, 2021; Zhong et al., 2019; Song, 2022; Cheng et al., 2023; Dong et al., 2017; Fang G. et al., 2021; Zhang, 2021; Wang, 2023; Shi et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2014; Zhou, 2023; Sha et al., 2018) with 954 cases were ultimately included in this meta-analysis. The general characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 2.

3.2 Risk of bias

While all included articles mentioned the use of randomization methods, only 6 (Cheng et al., 2023; Dong et al., 2017; Zhang, 2021; WANG, 2023; Shi et al., 2017; Zhou, 2023) articles provided detailed descriptions of their randomization procedures. The blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment in all included RCTs was unclear. However, all studies provided complete data, and no selective bias was discovered. Additionally, it was not possible to ascertain the presence of any other biases, which were therefore assessed as ‘unclear’ (Figures 2, 3).

3.3 Outcome measures

3.3.1 Disease control rate and objective response rate

Ten studies respectively reported DCR and ORR, including 810 cases. Statistical homogeneity was observed for both outcomes (I2 = 0%, P = 0.789, P = 0.949, respectively), and the fixed-effects model was applied. The combination of cinobufacini capsules and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy had a remarkable improvement in DCR (RR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.10–1.25, P < 0.0001; Figure 4A) and ORR (RR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.23–1.60, P < 0.0001; Figure 4B) compared to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy alone.

Figure 4. Forest plots of DCR (A) and ORR (B); Meta-regression analysis plots of DCR (C) and ORR (D).

Because only one study reported a treatment duration of 6 cycles, all studies were divided into 2 cycles (group 1) and ≥4 cycles (group 2) based on the treatment cycles. Subgroup analysis was performed to assess the impact of different treatment cycles of CC on DCR and ORR. Based on the findings, 2 cycles and ≥4 cycles of the combined treatment both enhanced the DCR (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04–1.26, P < 0.0001; RR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.30, P < 0.0001, respectively) and ORR (RR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.05–1.57, P < 0.0001; RR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.24–1.77, P < 0.0001, respectively). Additionally, meta-regression analysis showed that the treatment cycle did not affect DCR (P = 0.590) or ORR (P = 0.379). However, the results depicted in Figures 4C,D indicated a slight increase in tendency with an increased cycle number of cinobufacini capsules.

3.3.2 Tumor markers

A total of 6 studies reported CEA levels (Yang and Peng, 2021; Song, 2022; Cheng et al., 2023; Fang K. et al., 2021; Wang, 2023; Sha et al., 2018) and 4 studies (Song, 2022; Cheng et al., 2023; Wang, 2023; Sha et al., 2018) reported CA-125 levels between the treatment group and control group, with 506 and 324 patients, respectively. Because of the significant heterogeneity in CEA and CA-125 (I2 = 94.8% for CEA and 88.4% for CA-125, P ≤ 0.0001), a random-effects model was utilized. As depicted in Figures 5A,B, oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy combined with cinobufacin capsules can effectively reduce CEA (WMD = −7.84, 95% CI: 10.43 to −5.23, P < 0.0001) and CA-125 levels (WMD = −9.36, 95% CI: 12.80 to −5.92, P < 0.0001). Additionally, five studies (Yang and Peng, 2021; Cheng et al., 2023; Fang G. et al., 2021; Wang, 2023; Sha et al., 2018) with 406 patients reported CA19-9 levels, suggesting that combination therapy can lead to a reduction in CA19-9 levels (WMD = −11.38, 95% CI: 12.66 to −10.11, P < 0.0001; Figure 5C) with no observed heterogeneity (I2 = 5%, P = 0.378).

3.3.3 CD4 T cells

The expression levels of CD4 T cells (Song, 2022; Cheng et al., 2023; Wang, 2023; Sha et al., 2018) were reported in four studies, including 324 cases. A fixed-effects model was adopted based on low heterogeneity (I2 = 28%, P = 0.244). The results suggested that the combination therapy has a remarkable positive effect on increasing CD4 levels (WMD = 2.74, 95% CI: 1.99–3.49, P < 0.0001; Figure 6).

3.3.4 Adverse events

Five studies (Zhong et al., 2019; Song, 2022; Dong et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2014) with 390 patients reported leukocyte toxicity. As no heterogeneity was observed in this study (I2 = 0%, P = 0.820), a fixed-effects model was applied. The analysis revealed that combination therapy can effectively reduce leukocyte toxicity in patients with advanced CRC (RR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.48, 0.71, P < 0.0001; Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Forest plots of leukocyte toxicity (A), Myelosuppression (B), and gastrointestinal toxicity (C).

Myelosuppression was described in four studies (Yang and Peng, 2021; Zhang, 2021; Shi et al., 2017; Zhou, 2023) comprising 288 cases. No heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.955), and a fixed-effects model was finally applied. The analysis showed that compared with Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy alone, the combination therapy markedly decreased the occurrence of myelosuppression (RR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.46–0.92, P = 0.01; Figure 7B).

Adverse effects of gastrointestinal toxicity were reported in 6 references (Yang and Peng, 2021; Zhong et al., 2019; Song, 2022; Zhang, 2021; Lu et al., 2014; Zhou, 2023) including 470 cases. Owing to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 59%, P = 0.032), a random-effects model was employed. It was found that cinobufacini capsules plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy drastically reduced the number of patients with gastrointestinal toxicity when compared with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy alone. (RR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.62–0.99, P = 0.04; Figure 7C).

3.3.5 Sensitivity analysis

In this study, significant heterogeneity was observed in the levels of CEA and CA-125. After conducting sensitivity analyses, no source of heterogeneity was found, which indicated the reliability of the results (Figures 8A,B).

3.3.6 Publication bias

Publication bias of DCR and ORR was assessed through funnel plots and Begg’s/Egger’s tests. The funnel plot for DCR exhibited slight asymmetry, but both Begg’s test (z = 1.52, P = 0.152) and Egger’s test (t = 1.75, P = 0.118) indicated the absence of publication bias (Figures 9A–C). However, a potential publication bias was suggested by a minor imbalance on the ORR funnel plot. Begg’s test (z = - 1.16, P = 0.283) and Egger’s test (t = −1.80, P = 0.450) found no evidence of publication bias (Figures 9D–F).

Figure 9. Publication bias plots. Funnel plot (A); Begg plot (B); Egger plot (C) of DCR; Funnel plot (D); Begg plot (E); Egger plot (F) of ORR.

3.3.7 Quality of evidence

As illustrated in Table 3, when comparing the combination of cinobufacini capsules with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy alone, the quality of evidence was assessed as moderate for DCR and low for ORR. The GRADE evaluation did not include other secondary outcomes due to the limited number of studies available.

4 Discussion

The role of complementary therapies in improving treatment tolerance and clinical outcomes remains an important topic in the management of advanced colorectal cancer. In this context, the present meta-analysis examined the available randomized evidence regarding the addition of cinobufacini capsules to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. The findings indicate that combining cinobufacini with standard chemotherapy is associated with improved short-term response and a lower incidence of treatment-related adverse events, which may be particularly relevant for patients with stage III–IV disease who often experience cumulative toxicity.

Based on previous network meta-analyses (Tang et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022), the combination of oral or intravenous cinobufacini with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for CRC treatment has shown higher clinical efficacy, a significant reduction in adverse events, and improved immune function. However, the above studies did not focus on the effect of cinobufacini on advanced colorectal cancer. Our study incorporated the latest randomized controlled trials of cinobufacini in patients with stage III–IV CRC, suggesting that cinobufacini may reduce treatment-related toxicity while improving therapeutic efficacy.

Subgroup analysis of ORR and DCR indicated that patients receiving ≥4 cycles of the combined therapy appeared to have higher efficacy. However, this benefit was not statistically supported by exploratory meta-regression analyses, indicating that extended treatment cycles may not significantly enhance efficacy in advanced colorectal cancer. These discrepancies may be attributable to differences in baseline characteristics across studies, as well as the limited number of included studies and relatively small sample sizes. Additionally, sensitivity analyses did not identify any single study as the primary source of heterogeneity in CEA and CA-125 levels, suggesting that the variability likely reflects multifactorial clinical and methodological differences across studies. Moreover, the overall strength of evidence for DCR and ORR was rated as moderate and low, respectively, according to the GRADE approach. Our analysis also revealed that CC significantly reduces the incidence of adverse events, including leukocyte toxicity, myelosuppression, and gastrointestinal toxicity. Additionally, a phase 1 trial (Meng et al., 2009) indicated that cinobufacini, even at doses up to eight times higher than typically used in China, did not exhibit any dose-limiting toxicity, supporting the safety of CC for advanced CRC. Consequently, these findings suggest that CC combined with first-line treatment may improve clinical efficacy in stage III–IV colorectal cancer.

In traditional Chinese medicine theory, cinobufacini is believed to have the effects of clearing heat and detoxifying, reducing swelling, and resolving blood stasis (Qi et al., 2010). Recent pharmacological studies have shown that cinobufacini can promote tumor cell apoptosis, reverse multidrug resistance, and modulate the immune response (Zuo et al., 2024). A previous preclinical study reported that cinobufacini inhibited colon cancer invasion and metastasis by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and downregulating EMT-related genes, including MMP9, MMP2, N-cadherin, and Snail (Wang et al., 2020). Furthermore, Bufalin, the main active monomer in cinobufacini (Li M. et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023) demonstrates anti-tumor properties through various mechanisms. These mechanisms involve inhibiting angiogenesis through the SRC-3/HIF-1α and STAT3 pathways (Yuan et al., 2022; Fang K. et al., 2021) as well as inhibiting the JAK-STAT3 pathway and activating mitochondrial ROS-mediated caspase-3 to induce tumor cell apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2019). Moreover, bufalin suppresses CRC cell proliferation and metastasis by inhibiting the c-Kit/Slug signaling axis and the STAT3 pathway (Wang et al., 2023; Ding et al., 2022). In addition, bufalin can regulate the CD133/nuclear factor-κB/MDR1 and SRC-3/MIF pathways to mitigate chemotherapy resistance in CRC (Zhan Y. et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). Besides, other active ingredients isolated from the dried skin of Bufo gargarizans, including resibufogenin, telocinobufagin, and cinobufagin, have also demonstrated notable antitumor activity (Liang et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2022; Ha et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Hu and Luo, 2024). In the meantime, cionbufagin can significantly increase the population of CD4+CD8+ double-positive T cells, promote the phagocytosis and proliferation of macrophages, and regulate the levels of immune cytokines including interleukin-2, interleukin-4, interleukin-10, and interferon-γ (Zhao et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2015). Therefore, the elucidation of these mechanisms supported our conclusions at the molecular level.

The study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the RCTs included in this study had small sample sizes and were conducted only in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings and increase the risk of potential bias, including small-study effects that may lead to inflated pooled effect estimates. In addition, given the predominance of small-sample trials, the possibility that pooled effect estimates may be inflated cannot be completely excluded. Secondly, all of the studies exhibited some deficiencies in randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, resulting in a decrease in the overall quality of evidence. These methodological limitations may introduce performance, detection, and reporting bias, potentially leading to an overestimation of treatment effects, particularly for DCR and immune-related indicators. Moreover, the 12 RCTs included in this article did not report information on the primary site and molecular subtype of CRC. A previous study has shown that the median survival time for primary colorectal tumors located on the right side is approximately half that of those on the left (Venook et al., 2016), highlighting the significant impact of the primary location of CRC on treatment efficacy. Furthermore, various molecular subtypes including KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes, also play a crucial role in determining patient prognosis (Biller and Schrag, 2021). The absence of these crucial details hinders a comprehensive evaluation of cinobufacini’s efficacy in treating different molecular subtypes of advanced colorectal cancer. Furthermore, evidence regarding the long-term efficacy of CC is still limited. This is partly because most outcomes assessed in this meta-analysis, including disease control rate, objective response rate, tumor markers, and immune-related indicators, are surrogate or short-term endpoints, which do not allow definitive conclusions regarding overall survival or progression-free survival. Only one high-quality, randomized, phase II study in patients with stage II-III CRC reported a prolonged 3-year DFS after adjuvant cinobacillus treatment, suggesting a potential survival benefit.

Given the limited number and subpar quality of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) analyzed, it is imperative to conduct more RCTs with rigorously designed, long-term follow-up, clear molecular subtype, and multi-center participation to confirm the positive effects and enhance the evidence strength of cinobufacini for advanced colorectal cancer.

5 Conclusion

Overall, this meta-analysis suggests that cinobufacini capsules, when used as an adjunct to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, may offer potential benefits in patients with advanced colorectal cancer, particularly in improving short-term treatment response and tolerability. These findings support the possible role of cinobufacini as a complementary therapeutic option. However, the current evidence is limited by the generally low methodological quality of the available randomized controlled trials, potential bias risks, and the reliance on surrogate or short-term endpoints. Future well-designed, multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and clearly defined molecular subtypes are needed to determine the long-term clinical value of cinobufacini, including its impact on overall survival and progression-free survival.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. QG: Writing – original draft, Data curation. YQ: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software. DZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Supervision. JC: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The study was supported by Instructional Project of Quzhou (2020057), Instructional Project of Quzhou (2021005), Science and Technology Key Project of Quzhou (2022K48), Instructional Project of Quzhou (2019ASA90177), ‘New 115’ Talent Project of Quzhou, ‘551’ Health High-level Talents of Zhejiang Province, and ‘258’ Talent Project of Quzhou.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

DCR, disease control rate; ORR, objective response rate; RCTs, Randomized controlled trials; RR, relative risk; CRC, Colorectal cancer; SMD, standardized mean difference; WMD, weighted mean difference; C, control group; M/F, male/female; NA, not available; T, treatment group; XELOX, Xeloda + Oxaliplatin; FOLFOXIRI, Leucovorin+5-Fluorouracil + Oxaliplatin + Irinotecan; FOLFOX, Leucovorin+5-Fluorouracil + Oxaliplatin; PTX + OX, Raltitrexed + Oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI, 5-Fluorouracil + Oxaliplatin + Irinotecan; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; CI, Confidence interval; CNKI, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure; CBM, China Biological Medicine Database; NMPA, National Medical Products Administration; TNM, Tumor Node Metastasis; WOS, Web of Science; CC, Cinobufacini Capsule; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations and Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; WHO, World Health Organization; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors Outcome measures.

References

Alese, O. B., Wu, C., Chapin, W. J., Ulanja, M. B., Zheng-Lin, B., Amankwah, M., et al. (2023). Update on emerging therapies for advanced colorectal cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 43, e389574. doi:10.1200/EDBK_389574

Biller, L. H., and Schrag, D. (2021). Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. Jama 325 (7), 669–685. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.0106

Chen, J., Wang, H., Jia, L., He, J., Li, Y., Liu, H., et al. (2021). Bufalin targets the SRC-3/MIF pathway in chemoresistant cells to regulate M2 macrophage polarization in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 513, 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2021.05.008

Cheng, G., Han, J., Shan, L., Liu, X., Shi, W., and Ding, Y. (2023). Effects of Huachansu capsules combined with FOLFOXIRI scheme on immune function and tumor marker levels in patients with advanced rectal cancer. Med. Innovation China 20 (04), 34–38.

Ding, L., Yang, Y., Lu, Q., Qu, D., Chandrakesan, P., Feng, H., et al. (2022). Bufalin inhibits tumorigenesis, stemness, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer through a C-Kit/Slug signaling axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (21), 13354. doi:10.3390/ijms232113354

Dong, L., Li, H., Li, G., Lu, S., Wang, Y., and Li, Z. (2017). Clinical efficacy observation of cinobufacini capsules combined with XELOX regimen in the treatment of middle to late stage colorectal cancer. Strait Pharm. J. 29 (10), 169–171.

Fang, G., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhou, X., and Rao, H. (2021). Effects of Huachansu capsule combined with XELoX regimen on clinical symptoms and tumor markers in patients with rectal cancer. J. Hubei Univ. Chin. Med. 23 (06), 74–76.

Fang, K., Zhan, Y., Zhu, R., Wang, Y., Wu, C., Sun, M., et al. (2021). Bufalin suppresses tumour microenvironment-mediated angiogenesis by inhibiting the STAT3 signalling pathway. J. Transl. Med. 19 (1), 383. doi:10.1186/s12967-021-03058-z

Fass, O. Z., Poels, K. E., Qian, Y., Zhong, H., and Liang, P. S. (2020). Demographics predict stage III/IV colorectal cancer in individuals under age 50. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 54 (8), 714–719. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001374

Feria, A., and Times, M. (2024). Effectiveness of standard treatment for stage 4 colorectal cancer: traditional management with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 37 (2), 62–65. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1761420

Ferrer, M., Anthony, T. G., Ayres, J. S., Biffi, G., Brown, J. C., Caan, B. J., et al. (2023). Cachexia: a systemic consequence of progressive, unresolved disease. Cell 186 (9), 1824–1845. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.028

Han, Q., Ma, Y., Wang, H., Dai, Y., Chen, C., Liu, Y., et al. (2018). Resibufogenin suppresses colorectal cancer growth and metastasis through RIP3-mediated necroptosis. J. Transl. Med. 16 (1), 201. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1580-x

Hernandez Dominguez, O., Yilmaz, S., and Steele, S. R. (2023). Stage IV colorectal cancer management and treatment. J. Clin. Med. 12 (5), 2072. doi:10.3390/jcm12052072

Hu, Y., and Luo, M. (2024). Cinobufotalin regulates the USP36/c-Myc axis to suppress malignant phenotypes of colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Aging (Albany NY) 16 (6), 5526–5544. doi:10.18632/aging.205661

Innocenti, F., Sibley, A. B., Patil, S. A., Etheridge, A. S., Jiang, C., Ou, F. S., et al. (2021). Genomic analysis of germline variation associated with survival of patients with colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy plus biologics in CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). Clin. Cancer Res. 27 (1), 267–275. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2021

Jia, J., Li, J., Zheng, Q., and Li, D. (2022). A research update on the antitumor effects of active components of Chinese medicine ChanSu. Front. Oncol. 12, 1014637. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.1014637

Kasprzak, A. (2021). The role of tumor microenvironment cells in colorectal cancer (CRC) Cachexia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (4), 1565. doi:10.3390/ijms22041565

Kokotis, P., Schmelz, M., Kostouros, E., Karandreas, N., and Dimopoulos, M. A. (2016). Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: a long-term clinical and neurophysiologic Follow-Up study. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 15 (3), e133–e140. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2016.02.009

Li, S., Shen, D., Zuo, Q., Wang, S., Meng, L., Yu, J., et al. (2023). Efficacy and safety of Huachansu combined with adjuvant chemotherapy in resected colorectal cancer patients: a prospective, open-label, randomized phase II study. Med. Oncol. 40 (12), 358. doi:10.1007/s12032-023-02217-0

Li, X., Chen, C., Dai, Y., Huang, C., Han, Q., Jing, L., et al. (2019). Cinobufagin suppresses colorectal cancer angiogenesis by disrupting the endothelial mammalian target of rapamycin/hypoxia-inducible factor 1α axis. Cancer Sci. 110 (5), 1724–1734. doi:10.1111/cas.13988

Li, R., Wu, H., Wang, M., Zhou, A., Song, S., and Li, Q. (2022). An integrated strategy to delineate the chemical and dynamic metabolic profile of Huachansu tablets in rat plasma based on UPLC-ESI-QTOF/MS(E). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 218, 114866. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114866

Li, M., Qin, Y., Li, Z., Lan, J., Zhang, T., and Ding, Y. (2022). Comparative pharmacokinetics of cinobufacini capsule and injection by UPLC-MS/MS. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 944041. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.944041

Liang, S. T., Li, Y., Li, X. W., Wang, J. J., Tan, F. X., Han, Q. R., et al. (2016). Mechanism of colon cancer cell apoptosis induced by telocinobufagin: role of oxidative stress and apoptosis pathway. Nan Fang. Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 36 (7), 921–926.

Liu, S., Zhang, K., and Hu, X. (2022). Comparative efficacy and safety of Chinese medicine injections combined with capecitabine and oxaliplatin chemotherapies in treatment of colorectal cancer: a bayesian network meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1004259. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1004259

Lu, H., Lu, X., Shao, Q., Fu, W., and Zhang, L. (2014). A clinical study of 30 cases of advanced colorectal cancer treated with cinobufacini capsules combined with chemotherapy. Med. J. Commun. 28 (06), 647–8+51.

Meng, Z., Yang, P., Shen, Y., Bei, W., Zhang, Y., Ge, Y., et al. (2009). Pilot study of huachansu in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, or pancreatic cancer. Cancer 115 (22), 5309–5318. doi:10.1002/cncr.24602

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372, n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

Patel, S. G., Karlitz, J. J., Yen, T., Lieu, C. H., and Boland, C. R. (2022). The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 (3), 262–274. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00426-X

Qi, F., Li, A., Zhao, L., Xu, H., Inagaki, Y., Wang, D., et al. (2010). Cinobufacini, an aqueous extract from Bufo bufo gargarizans Cantor, induces apoptosis through a mitochondria-mediated pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Ethnopharmacology 128 (3), 654–661. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.02.022

Sha, X., Song, Z., Ding, J., and Zhang, J. (2018). Effects of Huachansu capsules combined with oxaliplatin on advanced colorectal cancer immunity, tumor markers, matrix metalloproteinases, and angiogenesis. J. Hainan Med. Univ. 24 (23), 2066–2069.

Shi, Y.-j., Li, Y., and Zhao, N. (2017). Efficacy of cinobufacini capsule combined with chemotherapy for stage III colorectal carcinoma after surgery. Chin. J. Clin. Oncol. Rehabilitation 24 (09), 1078–1081.

Shin, A. E., Giancotti, F. G., and Rustgi, A. K. (2023). Metastatic colorectal cancer: mechanisms and emerging therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 44 (4), 222–236. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2023.01.003

Siegel, R. L., Wagle, N. S., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A., and Jemal, A. (2023). Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73 (3), 233–254. doi:10.3322/caac.21772

Song, X. (2022). Effects of Huachansu capsules combined with FOLFOX chemotherapy in the treatment of colorectal cancer patients. Med. J. Chin. People's Health 34 (18), 31–3+40.

Strickler, J. H., Yoshino, T., Graham, R. P., Siena, S., and Bekaii-Saab, T. (2022). Diagnosis and treatment of ERBB2-Positive metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA Oncol. 8 (5), 760–769. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.8196

Tang, M., He, B., Zhai, J., and Wang, L. (2021). Oral Chinese patent medicine combined with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of colorectal cancer: a network meta-analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 20, 15347354211058169. doi:10.1177/15347354211058169

Venook, A. P., Niedzwiecki, D., Innocenti, F., Fruth, B., Greene, C., O'Neil, B. H., et al. (2016). Impact of primary (1°) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). Gastrointest. Color. Cancer.

Wang, Y. (2023). The efficacy of cinobufacini capsules combined with the XELOX chemotherapy regimen in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. Clin. Med. 43 (10), 102–105.

Wang, X. L., Zhao, G. H., Zhang, J., Shi, Q. Y., Guo, W. X., Tian, X. L., et al. (2011). Immunomodulatory effects of cinobufagin isolated from Chan Su on activation and cytokines secretion of immunocyte in vitro. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 13 (5), 383–392. doi:10.1080/10286020.2011.565746

Wang, J., Cai, H., Liu, Q., Xia, Y., Xing, L., Zuo, Q., et al. (2020). Cinobufacini inhibits Colon cancer invasion and metastasis via suppressing Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway and EMT. Am. J. Chin. Med. 48 (3), 703–718. doi:10.1142/S0192415X20500354

Wang, H., Chen, J., Li, S., Yang, J., Tang, D., Wu, W., et al. (2023). Bufalin reverses cancer-associated fibroblast-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis by inhibiting the STAT3 signaling pathway. Apoptosis 28 (3-4), 594–606. doi:10.1007/s10495-023-01819-3

Wei, X., Si, N., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Yang, J., Wang, H., et al. (2017). Evaluation of bufadienolides as the main antitumor components in Cinobufacin injection for liver and gastric cancer therapy. PLoS One 12 (1), e0169141. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169141

Weng, W., and Goel, A. (2022). Curcumin and colorectal cancer: an update and current perspective on this natural medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 80, 73–86. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.011

Wu, D., Zhou, W. Y., Lin, X. T., Fang, L., and Xie, C. M. (2019). Bufalin induces apoptosis via mitochondrial ROS-mediated caspase-3 activation in HCT-116 and SW620 human colon cancer cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 42 (4), 444–450. doi:10.1080/01480545.2018.1512611

Wu, Q., Xu, X., Liu, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, Q., and Zhang, D. (2025). Efficacy and safety of Huachansu capsule as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Ethnopharmacology 353 (Pt B), 120464. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2025.120464

Yang, Q., and Peng, S. (2021). Clinical effect and safety of XELOX regimen combined with Huachansu capsule in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Clin. Res. Pract. 6 (12), 36–38.

Yu, Y., Wang, H., Meng, X., Hao, L., Fu, Y., Fang, L., et al. (2015). Immunomodulatory effects of cinobufagin on murine lymphocytes and macrophages. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 835263. doi:10.1155/2015/835263

Yuan, Z., Liu, C., Sun, Y., Li, Y., Wu, H., Ma, S., et al. (2022). Bufalin exacerbates photodynamic therapy of colorectal cancer by targeting SRC-3/HIF-1α pathway. Int. J. Pharm. 624, 122018. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122018

Zhan, X., Wu, H., Wu, H., Wang, R., Luo, C., Gao, B., et al. (2020). Metabolites from Bufo gargarizans (cantor, 1842): a review of traditional uses, pharmacological activity, toxicity and quality control. J. Ethnopharmacology 246, 112178. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112178

Zhan, Y., Qiu, Y., Wang, H., Wang, Z., Xu, J., Fan, G., et al. (2020). Bufalin reverses multidrug resistance by regulating stemness through the CD133/nuclear factor-κB/MDR1 pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 111 (5), 1619–1630. doi:10.1111/cas.14345

Zhang, Z.-y. (2021). The influences of cinobufacin capsules combined with XELOX regimen for neoadjuvant chemotherapy on therapeutic effects and prognosis in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. China Mod. Med. 28 (21), 29–32.

Zhao, Y. Z., Wang, Y. L., and Yu, Y. (2024). Immunoenhancement effect of cinobufagin on macrophages and the cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression mouse model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 131, 111885. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111885

Zhong, L., He, J., Xu, Y., Jia, Y., and Lei, K. (2019). Clinical observation of cinobufacini capsules combined with CapeOX regimen in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Pract. Geriatr. 33 (11), 1123–1125.

Zhou, M. (2023). Effects of Huachansu capsules combined with Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin in treatment of patients with advanced rectal cancer. Med. J. Chin. People's Health 35 (08), 86–8+92.

Zhu, Z., Li, E., Liu, Y., Gao, Y., Sun, H., Ma, G., et al. (2012). Inhibition of Jak-STAT3 pathway enhances bufalin-induced apoptosis in colon cancer SW620 cells. World J. Surg. Oncol. 10, 228. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-10-228

Zraik, I. M., and Heß-Busch, Y. (2021). Management of chemotherapy side effects and their long-term sequelae. Urol. A 60 (7), 862–871.

Keywords: chemotherapy, cinobufacini capsules, colorectal cancer, meta-analysis, traditional Chinese medicine

Citation: Wang J, Gao Q, Que Y, Zheng D and Chen J (2026) Efficacy and safety of cinobufacini capsules combined with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer: a human systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 17:1709044. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2026.1709044

Received: 19 September 2025; Accepted: 15 January 2026;

Published: 30 January 2026.

Edited by:

Abdel Nasser B. Singab, Ain Shams University, EgyptReviewed by:

Leena Dhoble, University of Florida, United StatesMohd Rihan, USF Health, United States

Copyright © 2026 Wang, Gao, Que, Zheng and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianxin Chen, Y2p4ODEzN0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jian Wang

Jian Wang Qijia Gao2†

Qijia Gao2† Jianxin Chen

Jianxin Chen