- 1Guangzhou Municipal and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Molecular Target and Clinical Pharmacology, The NMPA and State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Guangdong Province Pharmacological Society, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

- 3Guangzhou United Family Hospital, Guangzhou, China

Background: Ensuring medication safety is a critical public health issue, particularly for widely used drugs like ulinastatin in critical care. Proactively identifying patients at high risk for adverse drug events is key to promoting safer medication practices and improving patient outcomes. This study focuses on developing a practical tool to stratify the risk of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes associated with ulinastatin use.

Methods: A multicenter, retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from 11,252 patients treated with ulinastatin between 2014 and 2017, 34 were excluded from the final statistical analysis due to missing critical data. Consequently, the cohort for all subsequent analyzes comprised 11,218 patients. The outcome of interest was the occurrence of a cardiopulmonary adverse event. We employed logistic regression to identify independent clinical risk factors and used these to construct a simple, points-based risk scoring system. The model’s performance in discriminating between high-risk and low-risk patients was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

Results: Among the cohort, 152 (1.35%) patients experienced a cardiopulmonary adverse outcome. Four factors were identified as independent predictors and incorporated into the risk model: low Ulinastatin dosage <300,000 U (OR (odds ratios) = 5.570, 95% CI (confidence intervals): 3.670–8.454, p < 0.001), duration of medication >1 day (OR = 2.165, 95% CI: 1.480–3.166, p < 0.001), concomitant medications (OR = 2.088, 95% CI: 1.414–3.083, p < 0.001), and treatment in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (OR = 3.737, 95% CI: 2.487–5.615, p < 0.001). The composite risk score demonstrated good predictive accuracy, with an AUC of 0.779 (95% CI: 0.741–0.817), significantly outperforming any single predictor.

Conclusion: We developed and validated a simple, clinically actionable risk stratification tool for cardiopulmonary adverse events in patients receiving ulinastatin. This model can help clinicians and healthcare systems identify high-risk individuals before treatment initiation, facilitating targeted monitoring, informed decision-making, and personalized dosing strategies. The implementation of such a tool represents a tangible step towards enhancing medication safety protocols and promoting safer prescribing behaviors in clinical practice.

Clinical Trial Registration: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=11439.

1 Introduction

Medication safety represents a cornerstone of public health and health promotion, particularly for drugs extensively utilized in critical care settings (Yao et al., 2020). Ulinastatin, a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor, is one such agent widely employed to manage inflammatory conditions including pancreatitis, severe pneumonia, and septic shock, and to mitigate inflammatory responses during major surgeries such as cardiopulmonary bypass (He et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020). As an adjunctive therapy, it has been shown to effectively reduce hospital length of stay, improve survival rates, and enhance prognostic outcomes (Chen et al., 2017; Teng et al., 2025). While its pharmacological profile, primarily mediated through the inhibition of hydrolase activity and modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, is well-recognized (Fukushima et al., 2021; Lagoo et al., 2018), the focus within public health must extend beyond efficacy to encompass the proactive management of associated risks.

The cardiopulmonary system, fundamental to human health and a primary target in systemic inflammatory responses, is particularly vulnerable (Raghuveer et al., 2020). Adverse outcomes affecting this system not only threaten survival but also profoundly impair long-term quality of life and functional capacity, placing a significant burden on healthcare systems and patients alike (Plesner et al., 2017). Although ulinastatin is generally considered protective towards cardiac and pulmonary tissues (He et al., 2015), its real-world safety profile necessitates rigorous, large-scale investigation. Clinical reports and pharmacovigilance data, such as that from the WHO (world health organization)’s VigiAccess database (Liang et al., 2024), confirm that cardiopulmonary adverse events, including atrial flutter, flushing, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and interstitial lung disease, constitute a notable proportion of reported issues associated with its use (Table 1), such as, cardiovascular disorders accounted for 8% of all adverse reactions associated with ulinastatin, with atrial flutter being the most frequently reported (14 cases). Vascular disorders constituted 4% of adverse events, among which flushing was the most common (7 cases). Similarly, respiratory disorders events, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, interstitial lung disease, were also observed in previous observations. This evidence underscores that even therapeutic agents with protective intentions can contribute to patient harm if risk factors are not adequately identified and managed.

Table 1. Selected cardiovascular adverse events and Respiratory adverse events reported for ulinastatin from VigiAccess.

Despite its widespread use, significant challenges remain in clinical practice regarding inappropriate administration and its impact on cardiopulmonary recovery, complication prevention, and specific patient populations. Improper use of ulinastatin may lead to adverse cardiopulmonary outcomes, which not only substantially impair patients’ quality of life but also pose serious threats to survival. This highlights a critical gap between the drug’s therapeutic potential and the optimization of its safe application. A key challenge in promoting safer medication use, therefore, lies in the transition from passive adverse event reporting to active, pre-emptive risk stratification. Current practice often lacks simple, actionable tools to identify individuals at heightened risk prior to treatment initiation. Factors such as inappropriate dosing, complex medication regimens, and patient care settings (e.g., the ICU) are potential modifiers of risk, yet their collective impact remains poorly quantified in routine practice.

Therefore, moving from a reactive to a preventive paradigm is essential. This study leverages a large, multicenter Phase IV clinical trial dataset to address this public health need. We aim to identify key clinical risk factors for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes following ulinastatin administration and, crucially, to integrate these factors into a validated, practical risk prediction model. The ultimate goal is to provide a decision-support tool that can guide clinicians in risk assessment before treatment, thereby fostering safer prescribing behaviors, enabling tailored patient monitoring, and contributing to the broader objective of optimizing medication safety outcomes in vulnerable populations.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources

This multicenter, retrospective study analyzed post-marketing data from patients treated with ulinastatin (manufactured by Guangdong Techpool Bio-pharma Co., Ltd., China) between August 2014 and June 2017 (Li et al., 2022). The study cohort comprised patients admitted to general wards and ICUs across nine participating hospitals in China. The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Approval No. B2014-056-01), which served as the lead center. All procedures were conducted in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine granted a waiver for the requirement of informed consent.

2.2 Study design

Excluded patients with missing data, this study enrolled 11,218 patients and the following data were collected: ulinastatin dosage (in 1 × 104 U units), history of cardiopulmonary diseases, ICU admission status, length of hospital stay, gender, concomitant medications, allergy history, and occurrence of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes. Based on the occurrence of such outcomes, the patients were categorized into two groups: those with cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes and those without. The cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes were ascertained from the Phase IV clinical trial database, to ensure consistency and accuracy in assessment, the terminology for all adverse outcomes was described in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (CTCAE v4.0). All outcomes were first evaluated by the attending physicians and subsequently reviewed by an independent expert panel to confirm their causality and relevance to ulinastatin. Subsequently, logistic regression analysis was employed to identify independent risk factors among the collected variables. Finally, these data were used to establish a risk scoring system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient selection flowchart and study overview. Of the 11,252 initially identified patients, 11,218 were included in the final analysis. Subsequently, 152 patients experienced cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes and were used to identify risk factors and develop a risk scoring system.

2.3 Dichotomous variables processing

Prior to regression analysis, all variables were assigned numerical values as follows: a history of cardiopulmonary disease was coded as 1, and its absence as 0; ICU admission as 1, and general ward admission as 0; allergy history as 1, and no allergy history as 0; male gender as 1, and female as 0; concomitant medication use as 1, and no concomitant medications as 0. Continuous variables were dichotomized based on clinical relevance: length of hospital stay greater than 7 days was assigned a value of 1 (≤7 days as 0), as most patients in the dataset had a hospital stay in 7 days. According to the prescribing information of ulinastatin (Lv et al., 2020), the recommended initial dose for adult patients with acute pancreatitis or chronic recurrent pancreatitis is 10 × 104 units per administration, diluted in 500 mL of 5% glucose injection or 0.9% sodium chloride injection for intravenous drip infusion over 1–2 h, administered 1–3 times daily. The dose may be gradually reduced as symptoms subside. For acute circulatory failure, the same dosage and dilution are recommended, with the option of slow intravenous injection under certain circumstances. The prescribed daily dose ranges between 10 × 104 and 30 × 104 units (Lyu et al., 2022). Based on the collected data, the average daily dose administered was 30 × 104 units. Therefore, a total daily dose of ≥30 × 104 units was assigned a value of 1, and <30 × 104 units as 0. Duration of medication >1 day was assigned a value of 1, and <1 day as 0. The variable ‘duration of medication >1 day’ was defined as the administration of ulinastatin on more than one calendar day, irrespective of the total infusion hours.

2.4 ROC curve

ROC curve analysis was constructed to evaluate the discriminatory performance of the predictive model by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity, true positive rate, TPR) against the false positive rate (1 – specificity, false positive rate, FPR) across all classification thresholds (Nahm, 2022; Lai et al., 2025). The ROC curve is formed with the FPR as the abscissa (x-axis) and the TPR as the ordinate (y-axis), wherein the coordinates (FPR, TPR) traversed across every conceivable threshold are joined to constitute the complete curve (Zhou et al., 2024). The overall performance was quantified by calculating the AUC, with an AUC of 1.0 indicating perfect discrimination and lower than 0.5 representing no discriminative capacity. The optimal cutoff value was identified based on the point on the curve closest to the top-left corner, maximizing both sensitivity and specificity.

2.5 Risk scoring system

A risk scoring system was developed to transform the multivariable logistic regression model into a simple (Chen et al., 2023), clinically applicable tool for predicting cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes. Initially, independent risk factors were identified through multivariable logistic regression, retaining variables with a significance level of p < 0.05. Each factor’s regression coefficient (β) was used to determine its relative weight (Lee et al., 2022). To construct the score, the β coefficient of each significant predictor was divided by a reference value (often the smallest β in the model), and rounded to the nearest integer to assign point values. For instance, a factor with β = 0.70 assigned 1 point, while another with β = 1.40 received 2 points. The points for all predictors were summed to calculate a total risk score for each patient. This score was then categorized into risk strata based on the observed incidence of the outcome in each score range. The total risk scores were then used to generate the ROC curve using SPSS software (version 25.0) (Wu et al., 2021). The discriminatory power of the risk scoring system was evaluated by comparing the area under the curve (AUC) with that of individual risk factors. Finally, risk stratification into high- and low-risk groups was performed to support clinical decision-making and guide intervention strategies.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 and Microsoft Excel. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test or t-test based on their distribution. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to calculate ORs and 95% CIs for identifying independent risk factors. A ROC curve was generated to evaluate the predictive performance of both the final multivariate model and the derived risk scoring system. The AUC was compared between the model and individual predictors. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients treated with ulinastatin

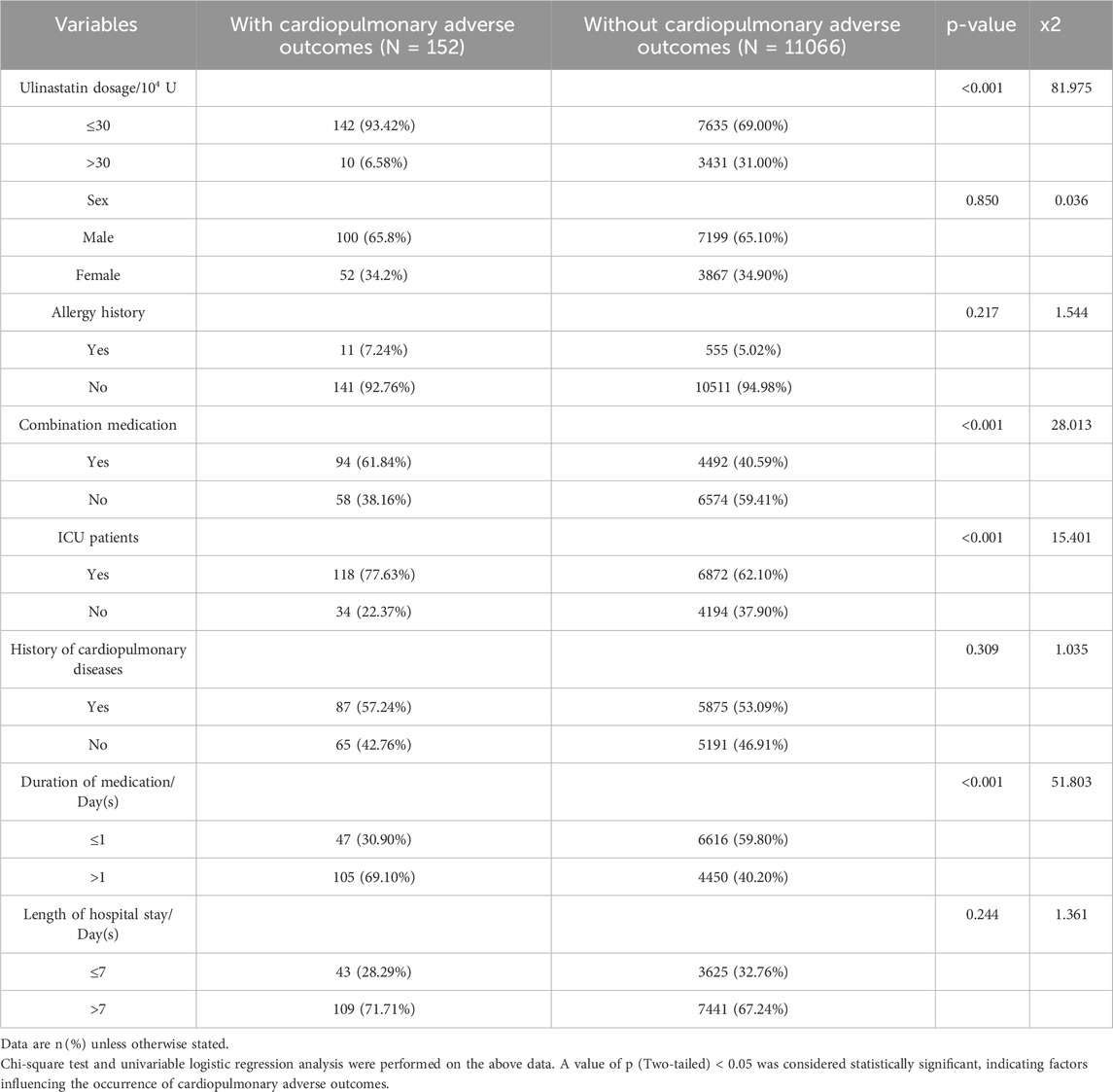

The analysis included a total of 11,218 patients treated with ulinastatin, after the exclusion of 34 individuals due to incomplete baseline information. Among this cohort, 152 patients (1.35%) experienced cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes (11,066 (98.65%) did not), establishing a clear patient safety endpoint for further investigation. The total dosage of ulinastatin administered ranged from 2 × 104 to 1.30 × 104 U, with a mean dose of 30.27 × 104 U. Univariate analysis aimed to identify clinical practices and patient profiles associated with this risk. It revealed significant associations with several identifiable factors. Specifically, a higher incidence of adverse outcomes was observed in patients receiving a total ulinastatin dosage of ≤30 × 104 U (93.42% vs. 69.00% in the general ward group; p < 0.001), those with concomitant medication use (61.84% vs. 40.59%; p < 0.001), ICU patients (77.63% vs. 62.10%; p < 0.001), and those with medication duration >1 day (69.10% vs. 40.20%; p < 0.001). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were found in sex (male: 65.8% vs. 65.10%; p = 0.850), allergy history (7.24% vs. 5.02%; p = 0.217), history of cardiopulmonary diseases (57.24% vs. 53.09%; p = 0.309), or length of hospital stay (>7 days: 71.71% vs. 67.24%; p = 0.244) between the two groups. The detailed distribution of all baseline characteristics is presented in Table 2.

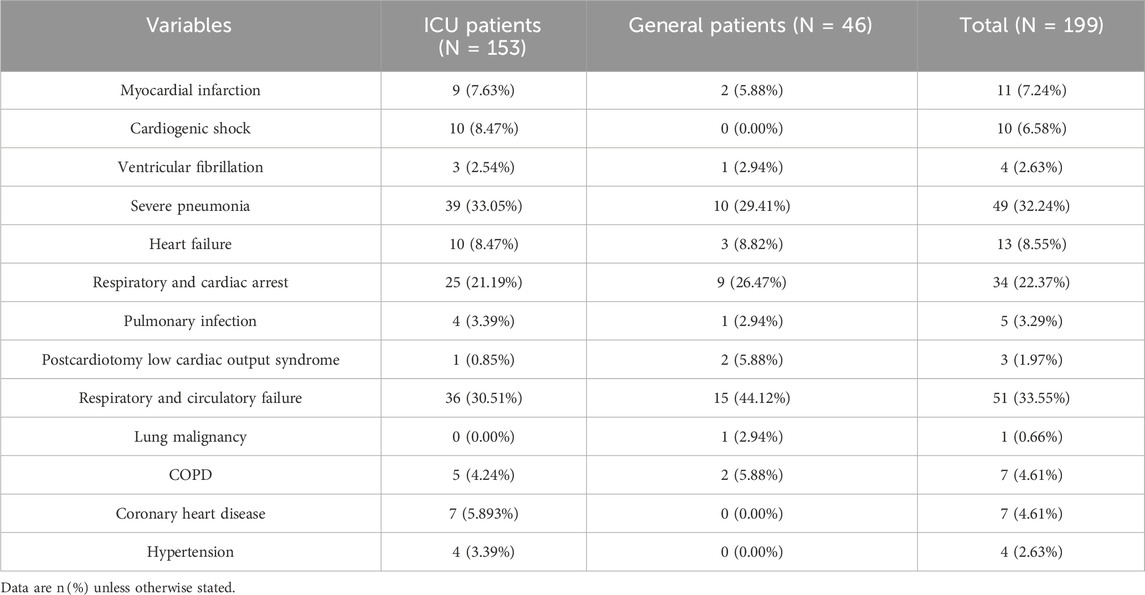

To further delineate the clinical burden of these events, we categorized the specific types of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes among the 152 affected patients. Among patients who experienced cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes, the top five conditions in the ICU setting were: severe pneumonia (39 cases, 33.05%), respiratory and circulatory failure (36 cases, 30.51%), respiratory and cardiac arrest (25 cases, 21.19%), cardiogenic shock and heart failure (each 10 cases, 8.47%), and myocardial infarction (9 cases, 7.63%). In the general ward group, the most frequent adverse outcomes were respiratory and circulatory failure (15 cases, 44.12%), severe pneumonia (10 cases, 29.41%), respiratory and cardiac arrest (9 cases, 26.47%), heart failure (3 cases, 8.82%), and myocardial infarction (2 cases, 5.88%). A complete breakdown of adverse outcome types is provided in Table 3, highlighting the severe nature of the events this study aims to help prevent.

Table 3. Analysis of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in 152 cases after ulinastatin administration.

3.2 Independent risk factors for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes after ulinastatin treatment

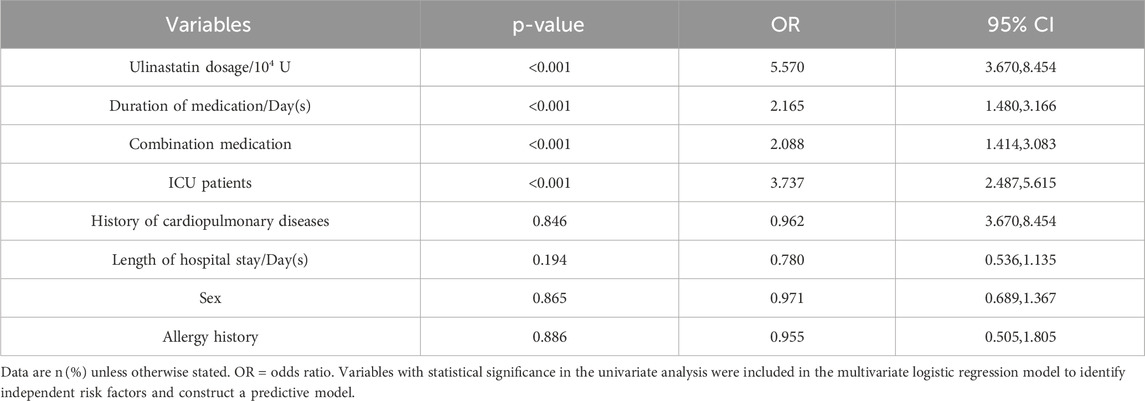

To identify independent and potentially modifiable predictors for preventive health strategies, all variables significant in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. These variables assessed included ulinastatin dosage, duration of medication/day(s), combination medication, ICU patients, history of cardiopulmonary diseases, length of hospital stay/day(s), sex, allergy history. The analysis revealed several independent predictors of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in patients receiving ulinastatin. A total ulinastatin dosage (low-dose) of ≤30 × 104 U was the strongest medication-related risk factor, associated with a more than five-fold increase in odds (OR = 5.570, 95% CI: 3.670–8.454, p < 0.001).

Admission to the ICU itself was the strongest overall predictor (OR = 3.737, 95% CI: 2.487–5.615, p < 0.001), highlighting a critical high-risk patient population. Prolonged medication duration (>1 day) was an independent risk factor (OR = 2.165, 95% CI: 1.480–3.166, p < 0.001). Concomitant medication use also significantly elevated the risk (OR = 2.088, 95% CI: 1.414–3.083, p < 0.001). In contrast, history of cardiopulmonary disease (OR = 0.962, 95% CI: 0.670–1.382, p = 0.846), length of hospital stay (OR = 0.780, 95% CI: 0.536–1.135, p = 0.194), sex (OR = 0.971, 95% CI: 0.689–1.367, p = 0.865), as well as allergy history (OR = 0.955, 95% CI: 0.505–1.805, p = 0.886) did not demonstrate statistically significant associations in the multivariable analysis (Detailed results are presented in Table 4). These results indicate that lower ulinastatin dosage (≤30 × 104 U), longer medication duration, concomitant medication use, and ICU admission are significant independent risk factors for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in patients treated with ulinastatin.

Table 4. Correlation between ulinastatin use and cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in 11218 patients.

3.3 Development of a clinically actionable risk scoring tool

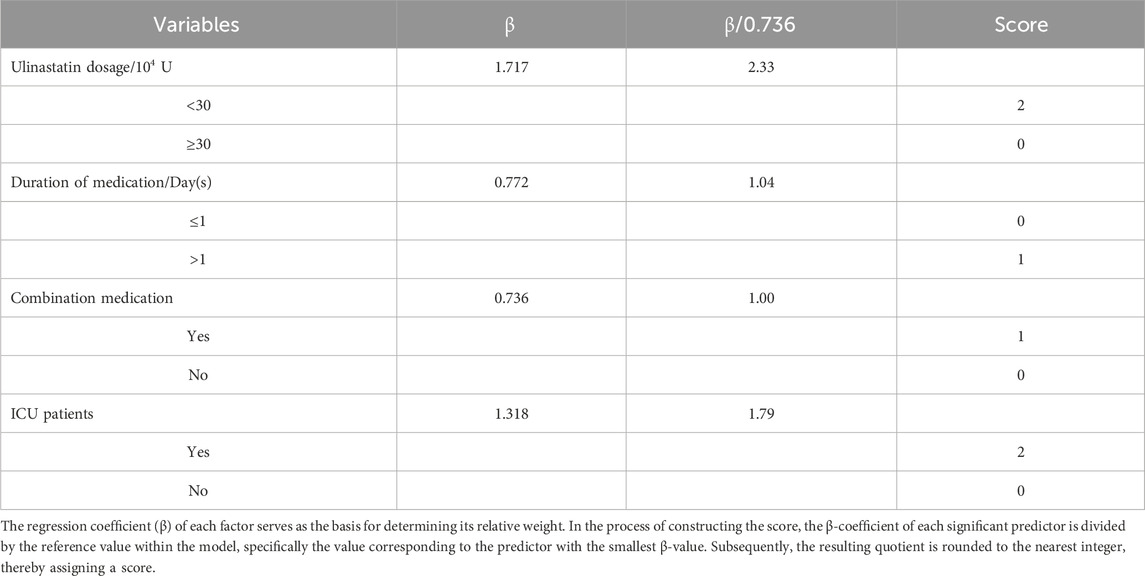

To translate the identified risk factors into a practical tool for preventive health screening, we developed a simple risk scoring system based on the regression coefficients (β) from the multivariable model. The goal was to create an intuitive score that could be easily calculated at the point of care to guide clinical behavior. The smallest β-value (0.736, for concomitant medication use) was used as the reference to standardize point assignments. The relative weight for each variable was calculated by dividing its β-coefficient by this reference value, followed by rounding to the nearest integer to assign practical point scores. The resulting points-based tool integrates the four independent risk factors as follows: ulinastatin dosage <30 × 104 U (β = 1.717, standardized value = 2.33, assigned 2 points) and ICU admission (β = 1.318, standardized value = 1.79, assigned 2 points) were the strongest predictors. Medication duration >1 day (β = 0.772, standardized value = 1.05, assigned 1 point) and concomitant medication use (β = 0.736, assigned 1 point) were also included in the scoring system. This yields a total risk score ranging from 0 to 6. The detailed derivation is shown in Table 5. This risk scoring system transforms complex statistical predictions into a readily applicable clinical tool. By allowing for the immediate stratification of patients into distinct risk categories based on routinely available data, it facilitates proactive, evidence-based decision-making. This directly supports the promotion of safer medication practices by enabling clinicians to identify high-risk patients prior to or during treatment, thereby targeting monitoring resources and guiding preventive strategies.

Table 5. Risk scoring system for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in patients administered ulinastatin.

3.4 Performance of the risk assessment system using ROC curve analysis

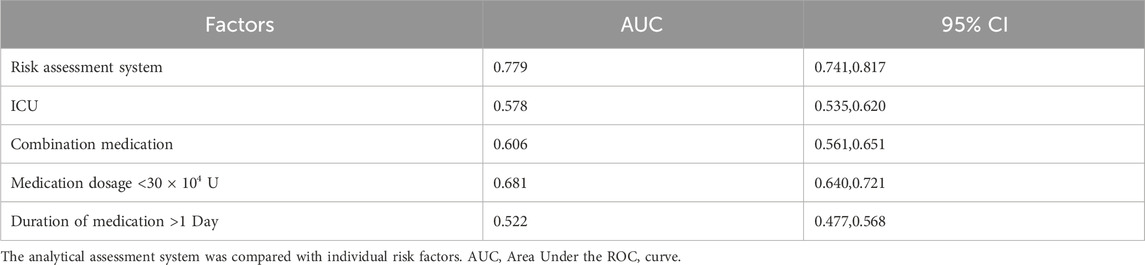

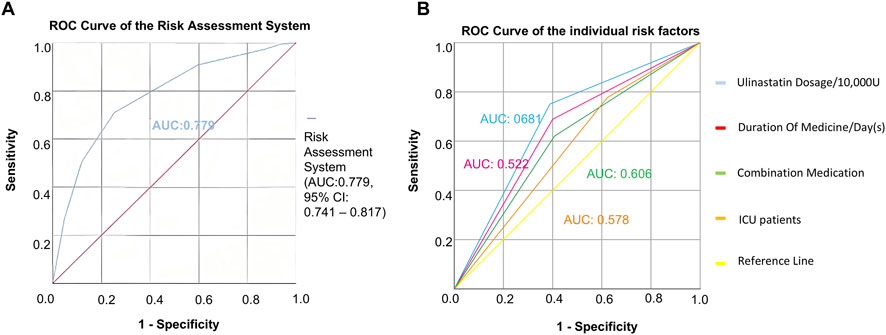

The predictive accuracy of the developed risk scoring system was evaluated using ROC curve analysis. Based on the scoring criteria established from multivariable regression, each of the 11,218 patients included in the study was assigned a total risk score ranging from 0 to 6. These scores were used as the test variable, with the actual occurrence of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes serving as the state variable. The resulting ROC curve (Figure 2A) demonstrated favorable discriminatory performance, with an AUC of 0.779 (95% CI: 0.741–0.817). This indicates that the risk scoring system has good overall accuracy in distinguishing between patients who experienced cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes and those who did not. An AUC value of 0.779 suggests that the model possesses clinically useful predictive ability, significantly exceeding random chance (AUC = 0.5) (Thomas et al., 2015). The narrow confidence interval further supports the robustness of this estimate. These findings confirm that the risk assessment system, incorporating four readily available clinical variables, serves as a reliable tool for stratifying patients according to their risk of developing cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes following ulinastatin administration.

Figure 2. Predictive performance of the risk assessment model. (A) ROC curve for the composite risk score. The area AUC was 0.779 (95% CI: 0.741–0.817). (B) Comparison of the ROC curves between the composite risk score and individual clinical predictors, demonstrating the superior discriminatory power of the integrated model.

3.5 Predictive performance of the risk assessment system for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes

To assess its prognostic utility, the performance of the newly developed risk assessment system was quantitatively evaluated against individual clinical predictors using ROC analysis. The composite risk score demonstrated significantly superior predictive accuracy, yielding an AUC of 0.779 (95% CI: 0.741–0.817). In contrast, the predictive capacities of the individual risk factors were considerably lower: ulinastatin dosage <30 × 104 U (AUC = 0.681, 95% CI: 0.640–0.721), combination medication use (AUC = 0.606, 95% CI: 0.561–0.651), ICU admission (AUC = 0.578, 95% CI: 0.535–0.620), and medication duration >1 day (AUC = 0.522, 95% CI: 0.477–0.568) (Table 6; Figure 2B). To transform the risk score into an actionable tool for clinical practice, an optimal cutoff value of ≥3.5 was established using Youden’s index, providing the optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity for identifying high-risk patients (Tang et al., 2024). As the total score is an integer, this cut-off is operationally applied such that a score of 0–3 is classified as low-risk, and a score of ≥4 is classified as high-risk. This threshold enables reliable stratification of patients into distinct risk categories, facilitating early identification of those who would benefit most from intensified monitoring and preventive care strategies. These findings affirm that integrating multiple predictors into a simple composite score provides a more robust foundation for clinical decision-making and resource allocation than relying on any single clinical indicator.

4 Discussion

Medication safety is a pivotal public health issue, and the safe application of immunomodulatory agents like ulinastatin in complex clinical settings represents a significant challenge and opportunity for health promotion. While ulinastatin, a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor, exerts its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects primarily by inhibiting excessive proteolytic activity (e.g., from trypsin and elastase), which in turn mitigates subsequent inflammatory cascade and organ injury. (Inoue et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2013), our findings underscore that its benefits are contingent upon appropriate clinical deployment. The identification of a low daily dose (<300,000 U) as the strongest modifiable risk factor for cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes (OR = 5.57) is a critical insight. This suggests that, in vulnerable populations, subtherapeutic dosing fails to provide adequate immunomodulatory coverage, potentially allowing uncontrolled inflammation to propagate organ injury. This is consistent with the drug’s short half-life (∼40 min) and the dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effects observed in preclinical models of lung injury (Xu et al., 2008). In clinical practice, it is plausible that clinicians tended to administer higher doses of ulinastatin to patients perceived as having more severe conditions or higher risk, while lower doses were used for patients with less severe presentations. This prescribing pattern could create a spurious association where the administered dose serves as a proxy for underlying disease severity. To address this concern, we analyzed dose as a continuous variable and observed a trend supporting the categorical findings. As the prescribing information for ulinastatin recommends a daily dose range of 10 × 104 to 30 × 104 units, we stratified patients by these dosage levels (e.g.,.above 10 × 104, 20 × 104, 30 × 104), and found a dose of 30 × 104 appeared to represent a threshold for a significantly lower risk of cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes. While these analytical approaches mitigate the concern to some extent, we fully acknowledge that residual confounding by unmeasured severity factors cannot be entirely ruled out. This highlights the need for future prospective, ideally randomized studies to definitively establish the causal effect of ulinastatin dosing. Beyond dosage, the other identified risk factors, ICU admission, prolonged therapy, and concomitant medications, collectively paint a picture of the complex, high-risk patient in whom clinical decision-making is most challenging. ICU admission serves as a proxy for severe immune dysregulation. Prolonged therapy often indicates persistent or difficult-to-control inflammation, and polypharmacy increases the risk of unforeseen drug interactions and compounded toxicities. Our study moves beyond merely identifying these risks by integrating them into a practical risk stratification tool. The robust performance of this tool (AUC = 0.779), which significantly outperformed any single predictor, validates the necessity of a holistic assessment over relying on isolated clinical cues.

The primary public health implication of our study lies in the translation of this risk score into actionable strategies for promoting safer medication use. A score at or above the cutoff of 4 effectively identifies patients who warrant a pre-emptive, intensified management protocol. This enables a shift from a reactive to a preventive model of care—a core principle of health promotion. For instance, high-risk patients could be flagged in the electronic health record (EHR) for automatic clinical decision support, triggering interventions such as first, protocol-driven dose optimization to avoid underdosing; second, enhanced monitoring (e.g., serial ECGs, biomarker assessment); and third, structured medication review by a clinical pharmacist to manage polypharmacy risks. This approach aligns with established health behavior models by providing a clear, easy-to-use tool that can guide and improve clinician behavior at the point of care.

We further propose that this risk model be integrated into hospital-based safety initiatives and professional training programs. Educating clinicians on these specific, modifiable risk factors and equipping them with a simple scoring system can foster a culture of safety and shared decision-making. This directly addresses the ‘how’ of health promotion in a clinical context, moving from knowledge to tangible practice.

In conclusion, this study transcends the conventional analysis of drug safety by developing and validating a practical tool for risk stratification. By pinpointing modifiable clinical practices and providing a means to identify at-risk individuals, our work offers a concrete strategy to enhance patient safety protocols. It provides a framework for optimizing clinical behavior, guiding resource allocation, and ultimately promoting healthier outcomes for patients receiving ulinastatin, thereby contributing meaningfully to the fields of medication safety and public health.

5 Conclusion

This study developed a validated risk prediction model for cardiopulmonary adverse events in patients receiving ulinastatin. The findings highlight that insufficient dosing is a critical, modifiable risk factor and provide a practical tool for preemptive risk stratification. Implementing this score can guide clinical decision-making, optimize medication safety, and promote healthier outcomes in vulnerable populations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (Approval No. B2014-056-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RH: Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – original draft. JD: Writing – review and editing, Investigation. QW: Writing – review and editing, Investigation. GL: Writing – review and editing, Methodology. RF: Writing – review and editing, Investigation. ZC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. YC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. X-YY: Writing – review and editing. JL: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. ZL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is supported by the Guangdong Provincial-Enterprise Joint Fund - General Project, YiFang joint Fund (2023A1515220207) and Scientific Research Project of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province (20251228).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:ICUs, intensive care units; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence intervals; AUC, area under the curve.

References

Chen, Q., Hu, C., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Zheng, H., et al. (2017). Safety and tolerability of high-dose ulinastatin after 2-hour intravenous infusion in adult healthy Chinese volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. Plos One 12, e0177425. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177425

Chen, Y., Han, H., Meng, X., Jin, H., Gao, D., Ma, L., et al. (2023). Development and validation of a scoring system for hemorrhage risk in brain arteriovenous malformations. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e231070. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1070

Fukushima, H., Oguchi, T., Sato, H., Nakadate, Y., Sato, T., Omiya, K., et al. (2021). Ulinastatin attenuates protamine-induced cardiotoxicity in rats by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor alpha. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol. 394, 373–381. doi:10.1007/s00210-020-01983-2

He, Q. L., Zhong, F., Ye, F., Wei, M., Liu, W. F., Li, M. N., et al. (2014). Does intraoperative ulinastatin improve postoperative clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 630835. doi:10.1155/2014/630835

He, S., Lin, K., Ma, R., Xu, R., and Xiao, Y. (2015). Effect of the urinary tryptin inhibitor ulinastatin on cardiopulmonary bypass-related inflammatory response and clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Ther. 37, 643–653. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.12.015

Inoue, K., Takano, H., Shimada, A., Yanagisawa, R., Sakurai, M., Yoshino, S., et al. (2005). Urinary trypsin inhibitor protects against systemic inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 673–680. doi:10.1124/mol.104.005967

Lagoo, J. Y., D'Souza, M. C., Kartha, A., and Kutappa, A. M. (2018). Role of ulinastatin, a trypsin inhibitor, in severe acute pancreatitis in critical care setting: a retrospective analysis. J. Crit. Care 45, 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.021

Lai, J., Cheng, C., Liang, T., Tang, L., Guo, X., and Liu, X. (2025). Development and multi-cohort validation of a machine learning-based simplified frailty assessment tool for clinical risk prediction. J. Transl. Med. 23, 921. doi:10.1186/s12967-025-06728-4

Lee, J. Y., Nam, B. H., Kim, M., Hwang, J., Kim, J. Y., Hyun, M., et al. (2022). A risk scoring system to predict progression to severe pneumonia in patients with Covid-19. Sci. Rep. 12, 5390. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-07610-9

Li, J., Li, M., Li, L., Ma, L., Cao, A., Wen, A., et al. (2022). Real-world safety of ulinastatin: a post-marketing surveillance of 11,252 patients in China. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 23, 51. doi:10.1186/s40360-022-00585-3

Liang, Q., Liao, X., Huang, Y., Zeng, J., Liang, C., He, Y., et al. (2024). Safety study on adverse events of zanubrutinib based on WHO-VigiAccess and FAERS databases. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 25, 1–8. doi:10.1080/14740338.2024.2416917

Liu, Y., Wang, Y. L., Zou, S. H., Sun, P. F., and Zhao, Q. (2020). Effect of high-dose ulinastatin on the cardiopulmonary bypass-induced inflammatory response in patients undergoing open-heart surgery. Chin. Med. J. Engl. 133, 1476–1478. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000832

Lv, H., Wei, X., Yi, X., Liu, J., Lu, P., Zhou, M., et al. (2020). High-dose ulinastatin to prevent late-onset acute renal failure after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ren. Fail 42, 137–145. doi:10.1080/0886022X.2020.1717530

Lyu, Y., Cao, M., Wei, C., Fang, H., and Lu, X. (2022). High-dose ulinastatin reduces postoperative bleeding and provides platelet-protective effects in patients undergoing heart valve replacement surgery. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 60, 463–468. doi:10.5414/CP204219

Nahm, F. S. (2022). Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 75, 25–36. doi:10.4097/kja.21209

Plesner, L. L., Dalsgaard, M., Schou, M., Køber, L., Vestbo, J., Kjøller, E., et al. (2017). The prognostic significance of lung function in stable heart failure outpatients. Clin. Cardiol. 40, 1145–1151. doi:10.1002/clc.22802

Raghuveer, G., Hartz, J., Lubans, D. R., Takken, T., Wiltz, J. L., Mietus-Snyder, M., et al. (2020). Cardiorespiratory fitness in youth: an important marker of health: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 142, e101–e118. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000866

Tang, J., Xu, Z., Ren, L., Xu, J., Chen, X., Jin, Y., et al. (2024). Association of serum Klotho with the severity and mortality among adults with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 408. doi:10.1186/s12944-024-02400-w

Teng, Y., Wang, J., Bo, Z., Wang, T., Yuan, Y., Gao, G., et al. (2025). Effects of different doses of ulinastatin on organ protection of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in rats. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 20, 156. doi:10.1186/s13019-025-03379-w

Thomas, D. M., Ivanescu, A. E., Martin, C. K., Heymsfield, S. B., Marshall, K., Bodrato, V. E., et al. (2015). Predicting successful long-term weight loss from short-term weight-loss outcomes: new insights from a dynamic energy balance model (the POUNDS Lost study). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 449–454. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.091520

Wu, B., Niu, Z., and Hu, F. (2021). Study on risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus and establishment of prediction model. Diabetes Metab. J. 45, 526–538. doi:10.4093/dmj.2020.0100

Xu, L., Ren, B., Li, M., Jiang, F., Zhanng, Z., and Hu, J. (2008). Ulinastatin suppresses systemic inflammatory response following lung ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Transpl. Proc. 40, 1310–1311. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.01.082

Xu, C. E., Zou, C. W., Zhang, M. Y., and Guo, L. (2013). Effects of high-dose ulinastatin on inflammatory response and pulmonary function in patients with type-A aortic dissection after cardiopulmonary bypass under deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 27, 479–484. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2012.11.001

Yao, Y. T., Fang, N. X., Liu, D. H., and Li, L. H. (2020). Ulinastatin reduces postoperative bleeding and red blood cell transfusion in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Baltim. 99, e19184. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019184

Keywords: adverse cardiopulmonary outcomes, phase IV study, post-marketing reevaluation, protease inhibitor, ulinastatin

Citation: Hua R, Zhang Y, Deng J, Wen Q, Li G, Fang R, Chen Z, Cao Y, Yu X-Y, Li J and Lin Z (2026) A risk prediction model for medication safety: assessing cardiopulmonary adverse outcomes in 11,252 patients treated with ulinastatin. Front. Pharmacol. 17:1746148. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2026.1746148

Received: 23 November 2025; Accepted: 09 January 2026;

Published: 21 January 2026.

Edited by:

Xiao Li, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Qida He, Xiamen University, ChinaLiqun Qu, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Copyright © 2026 Hua, Zhang, Deng, Wen, Li, Fang, Chen, Cao, Yu, Li and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhongxiao Lin, bHp4am9iQDE2My5jb20=; Jin Li, bWljaGFlbGh1bnRsZWVAZ21haWwuY29t; Xi-Yong Yu, eXV4eWNuQGFsaXl1bi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Rutong Hua1†

Rutong Hua1† Xi-Yong Yu

Xi-Yong Yu Jin Li

Jin Li Zhongxiao Lin

Zhongxiao Lin