- 1 School of Applied Biology, Shenzhen City Polytechnic, Shenzhen, China

- 2 School of Applied Biology, Shenzhen Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, China

- 3 School of Graduate Studies, Lingnan University, Tuen Mun, China

- 4 Guangzhou Municipal and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Molecular Target & Clinical Pharmacology, The NMPA and State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Tumors are considered to be among the most significant threats to human health. Immunotherapy, which is achieved through the body’s own immune response, shows great potential in the treatment of tumors. Nevertheless, the current low response rate in practical applications still needs to be overcome. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a minimally invasive treatment method that generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) through light irradiation of photosensitizers (PSs). It has been demonstrated that PDT is capable of not only efficiently eradicating tumors, but also effectively activating the immune system to recognize and destroy them. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the activation exhibits a persistent anti-tumor effect. It is evident that PDT demonstrates significant potential in the treatment of tumors, the inhibition of metastasis and the prevention of recurrence. This review summarizes the specific mechanisms of PDT-induced immune activation, including innate immunity and adaptive immunity, lists the relevant applications of organic and inorganic PSs in this field, and discusses the next challenges for PDT in tumor immunotherapy.

1 Introduction

Immunity can be defined as the body’s natural defense mechanism against foreign pathogens (Shen et al., 2025). In the presence of foreign substances within the body, macrophages are able to recognize non-self components and release signal molecules to activate effector cells (Joseph et al., 2025). This process ultimately results in the elimination of foreign substances and the induction of a therapeutic effect. The utilization of the immune system of the body to treat diseases has already shown unique advantages in various fields (Zhang et al., 2025; Yue et al., 2025; Akhtar et al., 2024; Chen S. et al., 2024; Bartosińska et al., 2025; Domka et al., 2023; Domka et al., 2024; Patil et al., 2023). In the domain of oncology, immunotherapy can reduce the occurrence of adverse effects when compared with alternative therapeutic modalities (Barjij and Meliani, 2025). Immunotherapy has also been identified as a leading treatment modality in the 21st century, with significant advancements being demonstrated in recent years. However, the prevailing single immunotherapy frequently exhibits inadequate therapeutic intensity, thus hindering its capacity to achieve complete disease eradication (Kah and Abrahamse, 2025). For instance, in the application of immune checkpoint blockade, a major branch of immunotherapy, the clinical non-response rate is relatively high due to individual differences (Aebisher et al., 2024a). Consequently, the exploration of novel solutions to bolster tumor immune responses may provide a renewed prospect for the efficacy of this therapeutic approach.

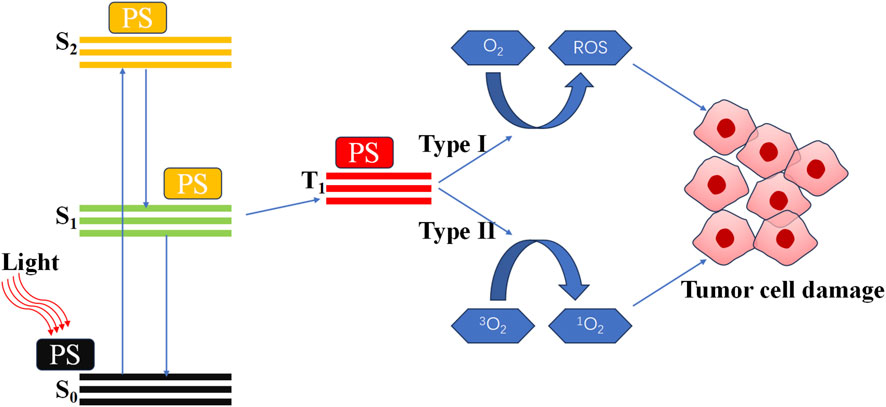

In vitro, stable and controllable non-destructive physical stimulation represents a highly effective method for activating the immune system (Adkins et al., 2014). These physical factors include light, sound, X-rays and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. Among these, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been identified as a highly effective solution to enhance immunotherapy (Hwang et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2010). PDT is a treatment modality that employs light activates photosensitizer (PS) to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Gore et al., 2025; Yang Y.-C. et al., 2023). The specific mechanism of PDT is illustrated in Figure 1 (Alvarez and Sevilla, 2024; Austin et al., 2025; Cai et al., 2025; Dobson et al., 2018). It was widely accepted that the therapeutic effect of PDT was a direct consequence of ROS. Excessive ROS can induce damage to DNA and proteins, thereby directly killing cancer cells (Wei et al., 2024; Agostinis et al., 2011). This constitutes the primary and most effective mechanism of PDT. And in the context of recurrent tumors and drug-resistant infections, PDT-induced immunotherapy has been shown to have significant potential (Xu et al., 2023; Gunaydin et al., 2021; He et al., 2023).

2 Photodynamic immunotherapy on tumor

Following the observation of tumor regression in cases of acute bacterial infection by William Bradley Coley, research into utilizing the body’s immune system to treat tumors has undergone significant expansion (Tsung and Norton, 2006). This approach is regarded as a non-invasive and effective means of preventing and treating tumors. However, during the application, it has been found that the differences in individual immune environments can lead to varying therapeutic effects. In certain instances, these disparities may even give rise to immunotherapy-resistant cases, thereby significantly hindering the advancement of immunotherapy. In order to enhance the immune response rate, researchers have initiated the exploration of combinations of immune and other alternative therapies. In certain studies, the combination of physical therapy, chemotherapy, gene therapy and immunotherapy has demonstrated synergistic effects and complementary advantages (Yang J.-K. et al., 2024). Specifically, the efficacy of physiotherapy and chemotherapy in reducing tumor volume, stimulating immunogenicity, promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines and antigens, and recruiting immune effector cells has been demonstrated (Kang et al., 2023; Huis et al., 2023). Among the aforementioned techniques, PDT is a non-invasive and controllable exogenous light stimulation technique that uses PS to produce ROS, thereby rapidly killing tumors (Cheng et al., 2022). In addition, PDT can stimulate immunomodulatory effects, which may enhance anti-tumor immunity and reduce the likelihood of metastasis and recurrence (Aebisher et al., 2024b).

Growing evidence shows that PDT has the capacity to activate both innate and adaptive immunity (Fang et al., 2025; Mazur et al., 2023; Rajan et al., 2024; Wahnou et al., 2023). An effective immune response can boost the elimination of tumors and the prevention of recurrence by maximizing local inflammatory responses and activating immune cells to destroy tumor tissues (Hua et al., 2021; Sorrin et al., 2020). Guided by the principles of cancer immunotherapy, an optimal PDT regimen should both destroy the primary tumor and induce immunogenic cell death (ICD). This activates the immune system to recognize and eliminate residual tumor cells, including distant metastases.

2.1 Immune activation induced by PDT

The anti-tumor effects of PDT are primarily attributable to three distinct mechanisms: ROS-induced cell death, damage to the tumor-associated vascular system and the initiation of tumor immune responses (Li M. et al., 2022). In this context, the immunogenicity of dead cancer cells has recently been identified as a pivotal factor in determining the efficacy of cancer therapy. Among these, ICD is a paradigm of highly effective cancer treatment, which triggers the activation of immune responses, resulting in strong and durable anticancer immunity specific for host cancer cells (Singh et al., 2024). A key feature of ICD is the emission of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). The ICD process involves the surface exposure and release of these molecules from dying cells. These released molecules serve as potent adjuvants, activating antigen-presenting cells. In turn, these cells phagocytose tumor debris, facilitate cross-presentation of antigens via major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) to CD8+ T cells, and thereby initiate a cellular immune response (Turubanova et al., 2019).

PDT has been demonstrated to be a strong inducer of innate immunity, which orchestrates significant anti-tumor effects. This innate activation is imperative for subsequently engaging the adaptive immune system (Jung et al., 2021). Key mechanisms include DAMP release by dendritic cells (DCs) to promote cross-presentation of tumor antigens to T lymphocytes (T cells), culminating in specific cytotoxic responses (Ding et al., 2025). Additionally, the resulting T cells can differentiate into memory cells, establishing long-term immunological protection against recurrence.

2.1.1 Activation of innate immunity

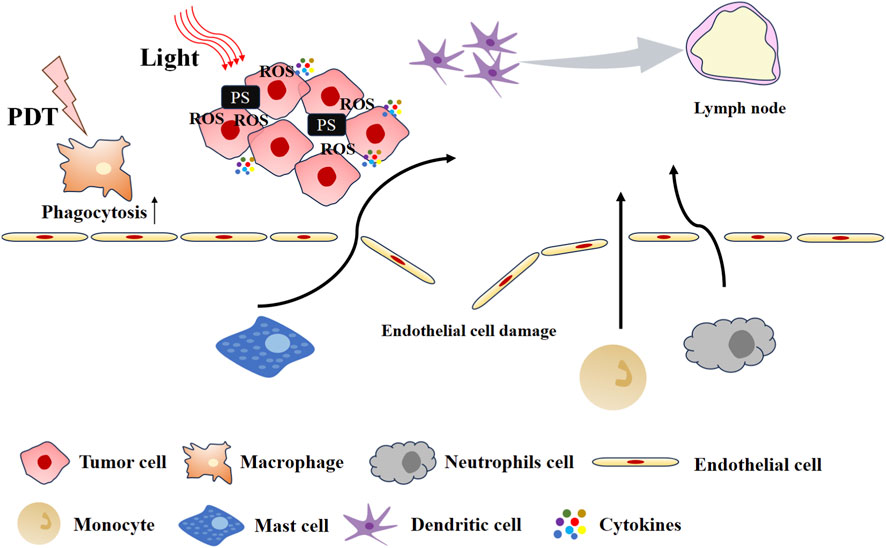

It is considered that PDT-induced acute inflammation is the initial step in PDT-enhanced anti-tumor immunity (Henderson et al., 2004). The inflammatory response induced by PDT is illustrated in Figure 2. The inflammatory response is accompanied by the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including interleukin (IL-6 and IL-8), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interferon (IFN), among others (Brackett and Gollnick, 2020; Vanden Berghe et al., 2006). Collectively, these factors promote the influx of innate immune cells into tumors, where they attack tumor cells. The upregulation of acute-phase proteins (APPs) in serum promotes the maturation and release of neutrophil progenitor cells from the bone marrow (Mušković et al., 2023). PDT-induced photodamage to tumor vasculature and complement system activation jointly drive neutrophil migration to and infiltration of the tumor site (Fingar, 1996). Following PDT, neutrophils are also observed in tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs), having entered through high endothelial venules (Kousis et al., 2007). Neutrophils exert anti-tumor effects both locally and systemically via two key mechanisms: direct destruction of tumor tissue and promotion of anti-tumor CD8+ T cell activation. In parallel, PDT also triggers other innate immune responses. For example, PDT induces high expression of HSP70 in tumor cells and activates the complement system, which together contribute to macrophage activation (Merchant and Korbelik, 2011). Additionally, the complement system is also activated to facilitate the dissolution of tumor cells.

2.1.2 Activation of adaptive immunity

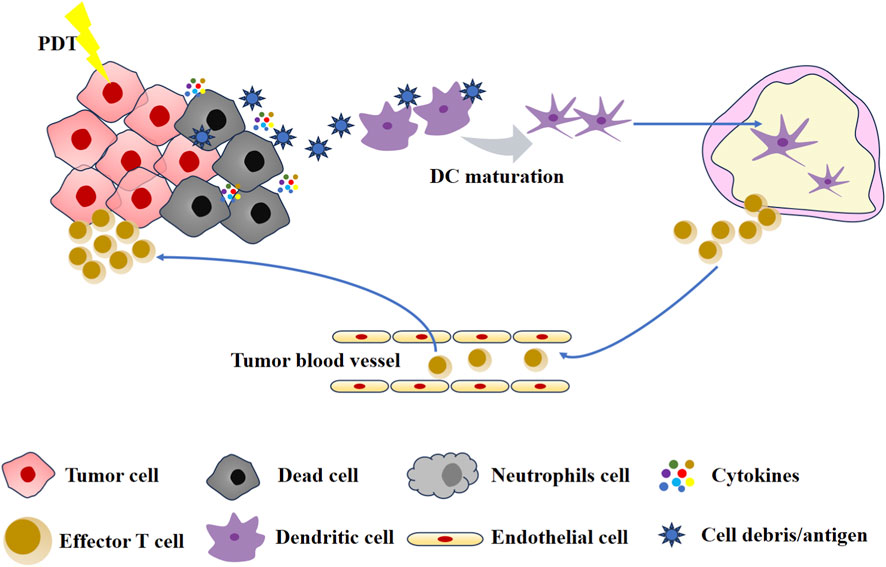

The adaptive immunity of PDT is attributable to ICD. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that PSs function as effective inducers of ICD (Du et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2024; Li Z. et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2025). The process stimulates the exposure of a considerable number of DAMPs. These DAMPs include calreticulin (CRT), high mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Barjij and Meliani, 2025). Subsequent to the release, the CRT migrates to the outer surface of the plasma membrane of dead tumor cells and is recognized by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) receptors on DCs (Garg et al., 2012). The outcome of this process is the maturation of DCs and the completion of the antigen presentation process. Following activation, DCs migrate to the lymph nodes, where they in turn activate T cells and B cells, thereby triggering an acquired immune response. Furthermore, it has been observed that extracellular ATP binds to purinergic receptors P2Y2 (P2Y2R) and P2X7 (P2X7R) on DCs (Agostinis et al., 2011). This leads to the recruitment of DCs, thereby promoting the formation of inflammasome and the secretion of inflammatory stimulators. Finally, activated DCs and T cells mediate patient-specific immune effects that result in the elimination of both primary and metastatic tumors (Mroz et al., 2011). The adaptive immunity induced by PDT is shown in Figure 3.

By stimulating a systemic immune response to eradicate tumors, PDT functions as an immunogenic modality (Relvas et al., 2023). This action, analogous to administering an in-situ vaccine, underlies the synergistic potential of combining PDT with immunotherapy to robustly amplify the host’s antitumor immunity. However, given the numerous factors that influence PDT, current combination therapy methods primarily concentrate on enhancing the efficiency of PDT. In accordance with the three elements of PDT including “light, PS and oxygen” the corresponding strategies are designed through regulating light fluence, PS dose and location, and improving molecular oxygen in the tissues. For example, PDT with high doses of PS and light energy usually induces “accidental” necrosis (Cramer et al., 2022; Kessel, 2020). Necrotic cells release injury-associated molecular patterns, and promote mature DCs and cytotoxic T cells (Donohoe et al., 2019). The impact of apoptosis on the immune system is characterized by a “silent” or “anti-inflammatory” response. It is only through the immunogenicity-induced process of apoptosis that immune activation is triggered (Garg and Agostinis, 2014).

Notably, tumor hypoxia compromises PDT efficacy by driving immunosuppression: it upregulates chemotactic cytokines (CCL22 and CCL28), recruits immunosuppressive cells like myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and reprograms macrophages and neutrophils toward tumor-promoting phenotypes, collectively fostering a pro-tumor microenvironment (Yang et al., 2021; Corzo et al., 2010). Critically, hypoxia also directly impairs the effector functions of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. Therefore, strategies to relieve tumor hypoxia are pivotal for enhancing PDT and its associated immunotherapy. A promising approach involves engineering nanomaterials capable of self-supplying oxygen. For example, Zhou et al. utilized catalase-loaded silica materials to decompose tumor H2O2 to produce oxygen, thereby alleviating hypoxia and eliciting a robust immune response characterized by M1 macrophage polarization, DC maturation, and CD8+ T cell infiltration (Xu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2025). This demonstrates the potential of combining PDT with oxygen-generating agents to induce potent antitumor immunity. Beyond enzyme-based systems, other inorganic nanomaterials with catalase-like activity, such as those composed of cerium (Ce), manganese (Mn), and platinum (Pt), have also been explored for in situ oxygen generation (Chen et al., 2023; Chudal et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2022). Furthermore, biohybrid strategies utilizing microorganisms have emerged. Certain microbes (e.g., Chlorella) harness photosynthesis within their thylakoid membranes, offering a novel biological method to elevate intratumoral O2 levels and potentiate PDT-mediated immunotherapy (Wang et al., 2021).

The immune efficacy of PDT is largely determined by the intracellular localization of the PS, which governs the mechanism of cell death and subsequent immune activation (Ji et al., 2022). Mitochondria-targeted PSs intensify mitochondrial oxidative stress, amplifying PDT-induced damage to promote antitumor immunity (Desai et al., 2024). Hydrophilic PSs often accumulate initially in lysosomes/endosomes, organelles integral to the autophagic and apoptotic death pathways engaged by PDT (Reiners et al., 2014; Plekhova et al., 2022). By contrast, the accumulation of amphiphilic or hydrophobic PSs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) markedly enhances therapeutic and immunogenic outcomes. This is because ER-localized ROS generation induces ER stress to stimulate the release of DAMPs including CRT, HMGB1, and heat shock proteins. Thus ROS production within the ER serves as a promising development strategy for effective ICD.

2.2 PSs in tumor photodynamic immunotherapy

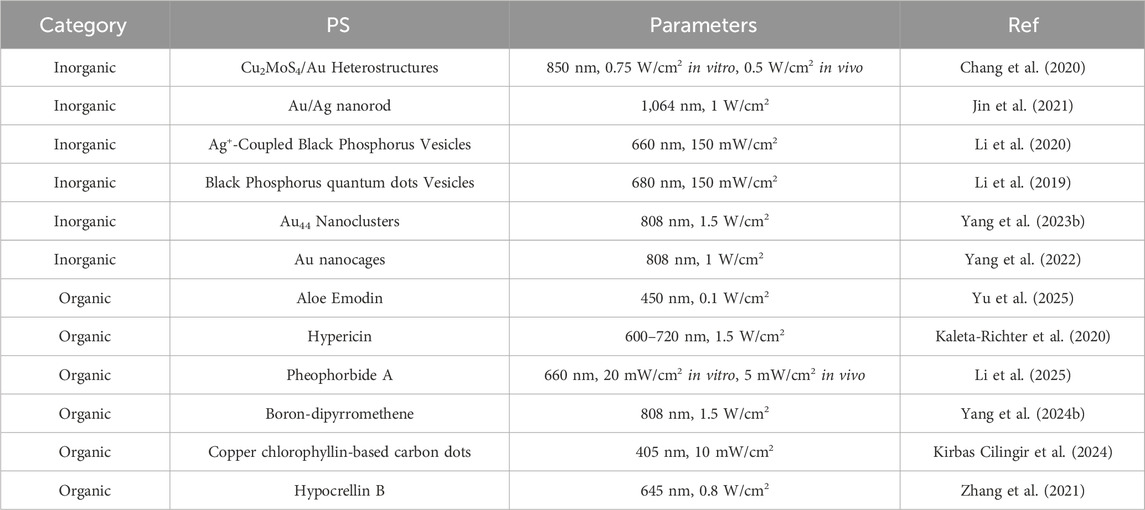

The efficiency of PDT is determined by three fundamental factors: light, PS and oxygen. The PS functions as an essential intermediate link between the other two elements, playing a pivotal role in the overall process (Zhang et al., 2022; Chen M. et al., 2024). It is important to note that not all PDT regimens are capable of producing immune effects, thus the selection of an appropriate PS constitutes the most critical step in PDT-assisted immunotherapy for tumor (Turubanova et al., 2021). Table 1 presents a selection of instances illustrating the application of PS for tumor immunotherapy.

2.2.1 Inorganic PSs

Inorganic PS primarily encompasses chalcogenides, black phosphorus, graphite and metal nanoparticles, which characteristically exhibit elevated light conversion efficiency and ROS production, thereby evoking considerable interest (Guo et al., 2023). It is evident that Au nanoparticles have become ideal candidates for PSs, owing to their strong surface plasmon resonance effect. Jin et al. designed an Au/Ag nanorod with the capability of adjusting its surface plasmon resonance band to the near-infrared II window (Jin et al., 2021). This adjustment is made possible through the precise control of the thickness of the Ag shell, thereby allowing the Au/Ag nanorod to elicit both PDT and photothermal effects when exposed to near-infrared II light. As demonstrated in the experimental section, the study revealed that exposure of Au/Ag nanorods to 1,064 nm irradiation resulted in the induction of ICD in tumor site. In addition, it has been demonstrated that this process facilitates the maturation of DCs and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, the process can induce an immune response in the body, thereby converting “cold” tumor into “hot” tumor and effectively inhibiting the growth of distant tumors in mice. This outcome is achieved through the combination of the Au/Ag nanorod with immune checkpoint inhibitors, thereby confirming that the treatment regimen triggered a strong immune memory effect.

In practical applications, some inorganic PS are difficult to degrade in vivo, thus research and development of biodegradable inorganic PS has attracted significant attention. Black phosphorus is an allotrope of phosphorus that can be prepared from white phosphorus or red phosphorus under conditions of high temperature and high pressure. The nanomaterials prepared from black phosphorus have adjustable band gaps and strong light absorption, thus being able to act as PSs or photothermal agents in PDT or PTT (Dong et al., 2022). Furthermore, the lone pair electrons on each phosphorus atom render black phosphorus more reactive to water and oxygen, and it is more readily biodegradable into non-toxic phosphate esters and phosphonic acid esters, making it safer. Li’s team initially constructed an Ag+ coupled black phosphorus vesicle (Li et al., 2020). In this combination, the strong charge coupling of Ag+ enhances the absorption of black phosphorus quantum dots in the near-infrared II region and is accompanied by a strong photoacoustic signal. This technology can be employed to facilitate accurate and in-depth biological tissue imaging, thereby providing a framework for guiding and monitoring the subsequent tumor treatment process. In tumor-bearing mouse models, the treatment with vesicles and 660 nm laser irradiation not only inhibited tumor growth in mice but also recruited immune cells for tumor immune responses. The enhanced immune effect of PDT was also verified in a mouse lung metastasis model.

Inorganic PSs are valued for their potent photodynamic properties and photostability, yet their inherent low biodegradability poses a significant barrier to clinical use. Persistent accumulation in tissues raises concerns about potential long-term toxicity (De Matteis, 2017). This has spurred the development of biodegradable or biocompatible material platforms as a clinically transformative direction. Furthermore, the biological fate and safety of these materials are profoundly influenced by their physicochemical properties, such as surface charge. Positively charged nanoparticles, for example, show enhanced mucosal interaction coupled with reduced retention, a profile that may improve safety (Wang D. et al., 2023). Consequently, achieving optimal biocompatibility through controlled degradation and tailored surface design is a paramount objective for the clinical development of next-generation inorganic PSs.

2.2.2 Organic PSs

The application of organic PSs is more extensive (Jia et al., 2023). As early as 2004, the first-generation PS porphyrin was reported to be capable of inducing ICD in mouse colon cancer cells through PDT and initiating the immune response in mice (Jalili et al., 2004). Subsequent to that, the field of PDT-induced tumor immunotherapy has undergone rapid development (Lu et al., 2023; Nasr Esfahani et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025; Zhao X. et al., 2024). For instance, Yu’s team demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the coordination ability of aloe-emodin with multivalent metal ions, specifically copper, to construct targeted nanoparticles (Yu et al., 2025). These nanoparticles were loaded with copper ions and aloe-emodin, thus offering a multifaceted approach to targeted drug delivery. The efficacy of these nanoparticles in activating antigen-presenting cells in tumor-bearing mice under 450 nm light excitation has been demonstrated. In addition, they have been demonstrated to activate T cells, promote the transformation of CD8+ T cells into central memory T cells, inhibit the activation of MDSCs, and promote the transformation of macrophages into M1. The induction of a strong adaptive immune response is of considerable therapeutic significance.

5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is a naturally occurring amino acid that has the capacity to synthesise protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) via the heme biosynthesis pathway (Wang L. et al., 2023). It has been established that heme biosynthesis is more active in tumor cells than in normal cells. Consequently, PpIX accumulates more in tumor cells, thus providing a natural advantage for the anti-tumor treatment of 5-ALA. In Zhao’s study, it was established that exosome release following 5-ALA treatment of skin squamous cell carcinoma, despite the absence of any cytotoxic effect on tumor cells, could induce the maturation of DCs and the secretion of IL-12, thereby enhancing anti-tumor immunity (Zhao et al., 2020).

In contrast to inorganic PSs, organic PSs demonstrate enhanced biocompatibility and synthetic tunability, key factors underpinning their clinical adoption (Lu et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2025). Notably, most PSs currently used in the clinic are small organic molecules or specific transition metal complexes, a preference attributable to their desirable pharmacokinetic and biophysical characteristics (Zhao D. et al., 2024). The field, however, faces enduring challenges, primarily the shallow penetration depth of light at typical PS excitation wavelengths (400–700 nm) and the hypoxic nature of tumors.

In response, there is a marked shift toward exploring natural products as novel PSs (Aziz et al., 2023). These agents offer the combined benefit of eliciting ICD via PDT and directly modulating the tumor immune microenvironment. A prominent case in point is hypericin, a naturally occurring ER-localizing PS. Upon light activation, it produces a sharp increase in ROS within the ER, culminating in significant ER stress and the induction of potent, immune-mediated antitumor effects (Xu et al., 2025). Complementing this, hypericin has been shown to decrease pro-tumor M2 macrophage populations, retard tumor growth, and boost infiltration of cytotoxic T cells into the tumor core (Buľková et al., 2023). Thereby, it helps establish a proinflammatory niche essential for activating adaptive immunity. The distinctive value of natural PSs thus lies in this dual functionality: competence in triggering ICD and an inherent capacity to remodel the immunosuppressive microenvironment, positioning them as promising and distinctive agents for the future of antitumor immunotherapy.

2.2.3 Advanced PSs

In addition to the above-mentioned PS, new types of PS are also being developed to cope with the complex microenvironment of tumor immunity. For instance, multifunctional natural microalgae and oncolytic viruses. Microalgae, a recently discovered photosensitizer, offers significant advantages and considerable development potential. Microalgae are abundant in natural photosynthetic pigments, including carotenoids and chlorophyll (Wang et al., 2025). These organisms have the capacity to directly produce ROS to induce tumor cell death in the presence of light with specific wavelengths (Zhou et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; An et al., 2024). It shows that microalgae is a more cost-effective and accessible alternative to synthetic photosensitizers because microalgae are amenable to cultivation, requiring only basic nitrogen and carbon sources, which further enhances their economic viability. In the context of tumor treatment, microalgae exhibit a distinctive advantage in hypoxic tumor regions. For instance, chlorophyll has the capacity to spontaneously generate oxygen under light excitation, thereby alleviating tumor hypoxia and significantly enhancing the efficacy of PDT killing tumor cells. Furthermore, microalgae have also been demonstrated to exhibit favorable biocompatibility and immunomodulatory functions (Pan et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2009; Kuznetsova et al., 2017). The polysaccharides and other immunologically active compounds contained therein have been shown to enhance the activity of key immune cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells to activate anti-tumor immune responses and counteract the immunosuppressive phenomena in the tumor microenvironment. These comprehensive characteristics underscore the potential for the development of microalgae as a multifunctional, cost-effective, and biocompatible photosensitizer in the combined strategy of tumor photodynamic therapy and immunomodulation, which is a highly promising avenue for further research.

Oncolytic viruses represent a highly versatile platform for cancer therapy, exhibiting a dual mechanism of action: direct oncolytic activity and the activation of anti-tumor immune responses (Bommareddy et al., 2018; Xi et al., 2024; Ji et al., 2024). Through the application of genetic engineering techniques, these viruses can be modified to express photosensitizer proteins, thus providing a targeted alternative to conventional photosensitizers. This combined strategy enhances overall anti-tumor efficacy by improving tumor-selective toxicity and modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME). The combination of oncolysis, immunostimulation and localized photodynamic action has the potential to create a new avenue for the development of more precise, potent and systemic anti-tumor therapies. In Shimizu’s research, an oncolytic herpes simplex virus G47-KR that can express the photosensitising protein Killer RED (KR) was constructed (Shimizu et al., 2023). G47-KR has been demonstrated to exhibit both the cytotoxic effect of an oncolytic virus and the capacity to release ROS through KR, a process that facilitates tumor cell killing and augments the infiltration of immune cells within the immune microenvironment.

These next-generation PSs constitute a significant advance for PDT-based immunotherapy. Their design mitigates historical drawbacks of low ROS efficiency in tumor and biocompatibility, thereby sustaining potent antitumor effects. A key gap remains in understanding their precise mechanisms of immune activation, especially within the complex and dynamic tumor immune microenvironment where PDT elicits immunotherapy gradually. Thus, clarifying the immune mechanisms of these materials will pave the way for precisely modulated immunotherapy capable of reversing immunosuppression and elevating response efficacy.

3 Development prospects of PDT-induced tumor immunotherapy

PDT-induced immunotherapy represents a promising paradigm in oncology, with demonstrated antitumor efficacy. However, its clinical translation faces a significant gap due to the dual challenges of restricted light penetration and tumor hypoxia. Innovative approaches, including advanced PSs employing photoconversion strategies, are in preclinical development but await clinical confirmation. The core issue of light delivery depth persists, especially for treating deep or disseminated disease. Concurrently, the field lacks a rational framework for PS design and a detailed understanding of immune activation mechanisms. Current reliance on complex natural product-derived PSs highlights the need for strategies to develop synthetically accessible and stable agents. Ultimately, the most critical barrier to widespread adoption is the absence of standardized treatment parameters and validated efficacy assessment criteria for PDT immunotherapy. Addressing this deficiency is imperative for transforming this promising approach into a robust and reliable clinical modality. Furthermore, current studies have challenged the prevailing view that PDT-triggered apoptosis and ER stress are crucial for ICD, suggesting that the key mechanism underlying the induction of ICD still requires further investigation (Thibaudeau et al., 2025).

A significant challenge in optimizing PDT-induced immunotherapy is the TME, which is a dynamic, immunosuppressive niche that plays a critical role in determining treatment response (He et al., 2025). The TME and tumor cells exist in a state of co-evolution, engaging in constant crosstalk via extracellular vesicles, cytokines, and paracrine factors. This interplay is a driving force behind tumor progression by regulating processes such as vascular behavior, cell metabolism, and metastatic spread (Badve and Gökmen-Polar, 2023; Yin et al., 2023; Aliazis et al., 2025). Consequently, therapeutic strategies that target only the tumor cells may inadvertently exacerbate pro-tumorigenic pathways within the TME, ultimately limiting efficacy and potentially promoting recurrence and metastasis. The development of multifunctional PSs or combination regimens offers a promising path forward. The objective of such approaches is threefold: firstly, to eradicate tumor cells via ROS; secondly, to reverse immunosuppression; and thirdly, to promote immune cell activation and establish durable antitumor memory. For instance, flavonoids and microalgae-based agents, when used in conjunction with photosensitizers, have demonstrated potential in reversing immunosuppressive cues and stimulating immune activation, though further mechanistic investigation is required.

PDT serves as a pivotal link between innate and adaptive immunity, effectively converting immunologically “cold” tumors into inflamed, immunogenic “hot” tumors. This immunomodulatory effect forms the cornerstone of its synergy with established cancer treatments, particularly immunotherapy. Substantial preclinical and clinical evidence demonstrates that PDT enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1), promoting sustained antitumor immunity and abscopal responses. Representative studies include the use of a targeted photosensitizer (IR700DX-6T) with epigenetic and immune therapy to overcome immunosuppression (Zhou et al., 2024), and the application of PDT to sensitize checkpoint-inhibitor-resistant pancreatic tumors to anti-PD-1 treatment (McMorrow et al., 2025). These findings illuminate viable paths to overcome primary and adaptive resistance.

Despite this promise, the majority of PDT-based combination regimens remain exploratory, underscoring an urgent need to expedite clinical translation. A fundamental challenge resides in the intricacy and heterogeneity of treatment responses, which are driven by dynamic tumor microenvironmental factors. Advancing this field will require biomarker-guided strategies, including monitoring immune infiltration, molecular signatures and epigenetic modifications, in order to predict efficacy, manage toxicity and select patients for precision combination therapies (Darvin et al., 2018). Consequently, the path to effective clinical integration of PDT with immunotherapy hinges on our ability to navigate this biological variability, underscoring the need for personalized approaches.

Author contributions

XC: Writing – original draft. AL: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. LL: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. CX: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This project is financially supported by Doctoral Research Initiation Project of Shenzhen Institute of Technology (2214010) and the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project of Shenzhen City Polytechnic (BS22026003). Furthermore, this project has also received funding from Guangdong Higher Vocational Colleges Industry-Education Integration Innovation Project (2025CJPT018) and Guangdong University Engineering Technology Research Center (2024GCZX016).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adkins, I., Fucikova, J., Garg, A. D., Agostinis, P., and Špíšek, R. (2014). Physical modalities inducing immunogenic tumor cell death for cancer immunotherapy. OncoImmunology 3, e968434. doi:10.4161/21624011.2014.968434

Aebisher, D., Przygórzewska, A., and Bartusik-Aebisher, D. (2024a). The latest look at PDT and immune checkpoints. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 46, 7239–7257. doi:10.3390/cimb46070430

Aebisher, D., Woźnicki, P., and Bartusik-Aebisher, D. (2024b). Photodynamic therapy and adaptive immunity induced by reactive oxygen species: recent reports. Cancers 16, 967. doi:10.3390/cancers16050967

Agostinis, P., Berg, K., Cengel, K. A., Foster, T. H., Girotti, A. W., Gollnick, S. O., et al. (2011). Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 61, 250–281. doi:10.3322/caac.20114

Akhtar, F., Misba, L., and Khan, A. U. (2024). The dual role of photodynamic therapy to treat cancer and microbial infection. Drug Discov. Today 29, 104099. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104099

Aliazis, K., Christofides, A., Shah, R., Yeo, Y. Y., Jiang, S., Charest, A., et al. (2025). The tumor microenvironment’s role in the response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Cancer 6, 924–937. doi:10.1038/s43018-025-00986-3

Alvarez, N., and Sevilla, A. (2024). Current advances in photodynamic therapy (PDT) and the future potential of PDT-combinatorial cancer therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 1023. doi:10.3390/ijms25021023

An, X., Zhong, D., Wu, W., Wang, R., Yang, L., Jiang, Q., et al. (2024). Doxorubicin-loaded microalgal delivery system for combined chemotherapy and enhanced photodynamic therapy of osteosarcoma. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 16, 6868–6878. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c16995

Austin, E., Wang, J. Y., Ozog, D. M., Zeitouni, N., Lim, H. W., and Jagdeo, J. (2025). Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J. Am. Acad. Dermatology. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

Aziz, B., Aziz, I., Khurshid, A., Raoufi, E., Esfahani, F. N., Jalilian, Z., et al. (2023). An overview of potential natural photosensitizers in cancer photodynamic therapy. Biomedicines 11, 224. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11010224

Badve, S. S., and Gökmen-Polar, Y. (2023). Targeting the tumor-tumor microenvironment crosstalk. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 27, 447–457. doi:10.1080/14728222.2023.2230362

Barjij, I., and Meliani, M. (2025). Immunogenic cell death as a target for combination therapies in solid tumors: a systematic review toward a new paradigm in immuno-oncology. Cureus 17, e85776. doi:10.7759/cureus.85776

Bartosińska, J., Kowalczuk, D., Szczepanik-Kułak, P., Kwaśny, M., and Krasowska, D. (2025). A review of photodynamic therapy for the treatment of viral skin diseases. Antivir. Ther. 30, 13596535251331728. doi:10.1177/13596535251331728

Bommareddy, P. K., Shettigar, M., and Kaufman, H. L. (2018). Integrating oncolytic viruses in combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 498–513. doi:10.1038/s41577-018-0014-6

Brackett, C. M., and Gollnick, S. O. (2020). Photodynamic therapy enhancement of anti-tumor immunity. Photochem. and Photobiological Sci. 10, 649–652. doi:10.1039/c0pp00354a

Buľková, V., Vargová, J., Babinčák, M., Jendželovský, R., Zdráhal, Z., Roudnický, P., et al. (2023). New findings on the action of hypericin in hypoxic cancer cells with a focus on the modulation of side population cells. Biomed. and Pharmacother. 163, 114829. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114829

Cai, Y. Y., Chai, T., Nguyen, W., Liu, J. Y., Xiao, E. H., Ran, X., et al. (2025). Phototherapy in cancer treatment: strategies and challenges. Signal Transduct. Tar 10, 115. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02140-y

Chan, G.C.-F., Chan, W. K., and Sze, D.M.-Y. (2009). The effects of β-glucan on human immune and cancer cells. J. Hematology and Oncology 2, 25. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-2-25

Chang, M., Hou, Z., Wang, M., Wang, M., Dang, P., Liu, J., et al. (2020). Cu2MoS4/Au heterostructures with enhanced Catalase-Like activity and photoconversion efficiency for primary/metastatic tumors eradication by phototherapy-induced immunotherapy. Small 16, 1907146. doi:10.1002/smll.201907146

Chen, X., Zhao, C., Liu, D., Lin, K., Lu, J., Zhao, S., et al. (2023). Intelligent Pd1. 7Bi@ CeO2 nanosystem with dual-enzyme-mimetic activities for cancer hypoxia relief and synergistic photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 15, 21804–21818. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c00056

Chen, S., Huang, B., Tian, J., and Zhang, W. (2024). Advancements of porphyrin-derived nanomaterials for antibacterial photodynamic therapy and biofilm eradication. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 13, e2401211. doi:10.1002/adhm.202401211

Chen, M., Zhu, Q., Zhang, Z., Chen, Q., and Yang, H. (2024). Recent advances in photosensitizer materials for light-mediated tumor therapy. Chem. – Asian J. 19, e202400268. doi:10.1002/asia.202400268

Chen, L., Lin, Y., Ding, S., Huang, M., and Jiang, L. (2025). Recent advances in clinically used and trialed photosensitizers for antitumor photodynamic therapy. Mol. Pharm. 22, 3530–3541. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5c00110

Cheng, X., Wei, Y., Jiang, X., Wang, C., Liu, M., Yan, J., et al. (2022). Insight into the prospects for tumor therapy based on photodynamic immunotherapy. Pharmaceuticals 15, 1359. doi:10.3390/ph15111359

Chudal, L., Pandey, N. K., Phan, J., Johnson, O., Li, X., and Chen, W. (2019). Investigation of PPIX-Lipo-MnO2 to enhance photodynamic therapy by improving tumor hypoxia. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 104, 109979. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.109979

Corzo, C. A., Condamine, T., Lu, L., Cotter, M. J., Youn, J.-I., Cheng, P., et al. (2010). HIF-1α regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2439–2453. doi:10.1084/jem.20100587

Cramer, G. M., Cengel, K. A., and Busch, T. M. (2022). Forging forward in photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 82, 534–536. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-4122

Darvin, P., Toor, S. M., Sasidharan Nair, V., and Elkord, E. (2018). Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp. and Mol. Med. 50, 1–11. doi:10.1038/s12276-018-0191-1

De Matteis, V. (2017). Exposure to inorganic nanoparticles: routes of entry, immune response, biodistribution and in vitro/in vivo toxicity evaluation. Toxics 5, 29. doi:10.3390/toxics5040029

Desai, V. M., Choudhary, M., Chowdhury, R., and Singhvi, G. (2024). Photodynamic therapy induced mitochondrial targeting strategies for cancer treatment: emerging trends and insights. Mol. Pharm. 21, 1591–1608. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.3c01185

Ding, Q., Chen, S., Hua, S., Yoo, J., Yoon, C., Li, Z., et al. (2025). Photoactivated nanovaccines. Chem. Soc. Rev. 54, 9807–9848. doi:10.1039/d5cs00608b

Dobson, J., de Queiroz, G. F., and Golding, J. P. (2018). Photodynamic therapy and diagnosis: principles and comparative aspects. Veterinary J. 233, 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.11.012

Domka, W., Bartusik-Aebisher, D., Mytych, W., Dynarowicz, K., and Aebisher, D. (2023). The use of photodynamic therapy for head, neck, and brain diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11867. doi:10.3390/ijms241411867

Domka, W., Bartusik-Aebisher, D., Mytych, W., Myśliwiec, A., Dynarowicz, K., Cieślar, G., et al. (2024). Photodynamic therapy for eye, ear, laryngeal area, and nasal and oral cavity diseases: a review. Cancers 16, 645. doi:10.3390/cancers16030645

Dong, W. J., Wang, H., Liu, H. L., Zhou, C. Q., Zhang, X. L., Wang, S., et al. (2022). Potential of black phosphorus in immune-based therapeutic strategies. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 3790097. doi:10.1155/2022/3790097

Donohoe, C., Senge, M. O., Arnaut, L. G., and Gomes-da-Silva, L. C. (2019). Cell death in photodynamic therapy: from oxidative stress to anti-tumor immunity. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 1872, 188308. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.07.003

Du, F., Chen, Z., Li, X., Hong, X., Wang, L., Cai, F., et al. (2025). Organelle-targeted photodynamic platforms: from ICD activation to tumor ablation. Chem. Communications 61, 12835–12847. doi:10.1039/d5cc03574k

Fang, K., Yuan, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Sun, S.-l., and Li, X. (2025). Regulation of immunogenic cell death and potential applications in cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 16, 1571212. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1571212

Fingar, V. H. (1996). Vascular effects of photodynamic therapy. J. Clin. Laser Med. and Surg. 14, 323–328. doi:10.1089/clm.1996.14.323

Garg, A. D., and Agostinis, P. (2014). ER stress, autophagy and immunogenic cell death in photodynamic therapy-induced anti-cancer immune responses. Photochem. and Photobiological Sci. 13, 474–487. doi:10.1039/c3pp50333j

Garg, A. D., Nowis, D., Golab, J., and Agostinis, P. (2010). Photodynamic therapy: illuminating the road from cell death towards anti-tumor immunity. Apoptosis 15, 1050–1071. doi:10.1007/s10495-010-0479-7

Garg, A. D., Krysko, D. V., Vandenabeele, P., and Agostinis, P. (2012). The emergence of phox-ER stress induced immunogenic apoptosis. Oncoimmunology 1, 786–788. doi:10.4161/onci.19750

Gore, S., Are, V., Chanchlani, B., Shishira, P. S., and Biswas, S. (2025). Multifunctional nanoplatforms for combined photothermal and photodynamic therapy: tumor-responsive strategies for enhanced precision. Int. J. Pharm. 684, 126131. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2025.126131

Gunaydin, G., Gedik, M. E., and Ayan, S. (2021). Photodynamic therapy—current limitations and novel approaches. Front. Chem. 9, 691697. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.691697

Guo, Z., Zhu, A. T., Fang, R. H., and Zhang, L. (2023). Recent developments in nanoparticle-based photo-immunotherapy for cancer treatment. Small Methods 7, e2300252. doi:10.1002/smtd.202300252

He, P. Y., Zhang, F., Xu, B., Wang, Y. P., Pu, W. G., Wang, H. Y., et al. (2023). Research progress of potential factors influencing photodynamic therapy for gastrointestinal cancer. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 41, 103271. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2022.103271

He, Z., Huang, Y., Wen, Y., Zou, Y., Nie, K., Liu, Z., et al. (2025). Tumor treatment by nano-photodynamic agents embedded in immune cell membrane-derived vesicles. Pharmaceutics 17, 481. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17040481

Henderson, B. W., Gollnick, S. O., Snyder, J. W., Busch, T. M., Kousis, P. C., Cheney, R. T., et al. (2004). Choice of oxygen-conserving treatment regimen determines the inflammatory response and outcome of photodynamic therapy of tumors. Cancer Res. 64, 2120–2126. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3513

Hua, J., Wu, P., Gan, L., Zhang, Z., He, J., Zhong, L., et al. (2021). Current strategies for tumor photodynamic therapy combined with immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 11, 738323. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.738323

Huis, R. V., Heuts, J., Heuts, J., Ma, S., Cruz, L. J., Ossendorp, F. A., et al. (2023). Current challenges and opportunities of photodynamic therapy against cancer. Pharmaceutics 15, 330. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15020330

Hwang, H. S., Shin, H., Han, J., and Na, K. (2018). Combination of photodynamic therapy (PDT) and anti-tumor immunity in cancer therapy. J. Pharm. Investigation 48, 143–151. doi:10.1007/s40005-017-0377-x

Jalili, A., Makowski, M., Świtaj, T., Nowis, D., Wilczyński, G. M., Wilczek, E., et al. (2004). Effective photoimmunotherapy of Murine Colon carcinoma induced by the combination of photodynamic therapy and dendritic cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4498–4508. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-04-0367

Ji, B., Wei, M., and Yang, B. (2022). Recent advances in nanomedicines for photodynamic therapy (PDT)-driven cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics 12, 434–458. doi:10.7150/thno.67300

Ji, F., Shi, C., Shu, Z., and Li, Z. (2024). Nanomaterials enhance pyroptosis-based tumor immunotherapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 19, 5545–5579. doi:10.2147/ijn.s457309

Jia, J., Wu, X., Long, G., Yu, J., He, W., Zhang, H., et al. (2023). Revolutionizing cancer treatment: nanotechnology-enabled photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy with advanced photosensitizers. Front. Immunol. 14, 3790097. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1219785

Jin, L., Shen, S., Huang, Y., Li, D., and Yang, X. (2021). Corn-like Au/Ag nanorod-mediated NIR-II photothermal/photodynamic therapy potentiates immune checkpoint antibody efficacy by reprogramming the cold tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials 268, 120582. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120582

Joseph, A. M., Al Aiyan, A., Kumari, R., George, A. J. T., and Kishore, U. (2025). Role of innate immunity in cancer. Adv. Experimental Medicine Biology 1476, 309–337. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-85340-1_13

Jung, A. C., Moinard-Butot, F., Thibaudeau, C., Gasser, G., and Gaiddon, C. (2021). Antitumor immune response triggered by metal-based photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy: where are we? Pharmaceutics 13, 1788. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13111788

Kah, G., and Abrahamse, H. (2025). Overcoming resistant cancerous tumors through combined photodynamic and immunotherapy (photoimmunotherapy). Front. Immunol. 16, 1633953. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1633953

Kaleta-Richter, M., Aebisher, D., Jaworska, D., Czuba, Z., Cieślar, G., and Kawczyk-Krupka, A. (2020). The influence of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy on Interleukin-8 and -10 secretion in Colon cancer cells. Integr. Cancer Ther. 19. 1534735420918931. doi:10.1177/1534735420918931

Kang, W., Liu, Y., and Wang, W. (2023). Light-responsive nanomedicine for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 13, 2346–2368. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.016

Kessel, D. (2020). Photodynamic therapy: apoptosis, paraptosis and beyond. Apoptosis 25, 611–615. doi:10.1007/s10495-020-01634-0

Kirbas Cilingir, E., Besbinar, O., Giro, L., Bartoli, M., Hueso, J. L., Mintz, K. J., et al. (2024). Small warriors of nature: novel red emissive Chlorophyllin carbon dots harnessing fenton-fueled ferroptosis for in vitro and in vivo cancer treatment. Small 20, e2309283. doi:10.1002/smll.202309283

Kousis, P. C., Henderson, B. W., Maier, P. G., and Gollnick, S. O. (2007). Photodynamic therapy enhancement of antitumor immunity is regulated by neutrophils. Cancer Research 67, 10501–10510. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1778

Kuznetsova, T. A., Ivanushko, L. A., Persiyanova, E. V., Shutikova, A. L., Ermakova, S. P., Khotimchenko, M. Y., et al. (2017). Evaluation of adjuvant effects of fucoidane from brown seaweed fucus evanescens and its structural analogues for the strengthening vaccines effectiveness. Biomeditsinskaia Khimiia 63, 553–558. doi:10.18097/PBMC20176306553

Lee, J. H., Yang, S. B., Park, S. J., Kweon, S., Ma, G., Seo, M., et al. (2025). Cell-penetrating peptide like anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 peptide conjugate-based self-assembled nanoparticles for immunogenic photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano 19, 2870–2889. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c16128

Li, Z., Hu, Y., Fu, Q., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Song, J., et al. (2019). NIR/ROS-Responsive black phosphorus QD vesicles as immunoadjuvant carrier for specific cancer photodynamic immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1905758. doi:10.1002/adfm.201905758

Li, Z., Fu, Q., Ye, J., Ge, X., Wang, J., Song, J., et al. (2020). Ag+-coupled black phosphorus vesicles with emerging NIR-II photoacoustic imaging performance for cancer immune-dynamic therapy and fast wound healing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22202–22209. doi:10.1002/anie.202009609

Li, M., Zhao, M., and Li, J. (2022). Near-infrared absorbing semiconducting polymer nanomedicines for cancer therapy. WIREs Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology 15, e1865. doi:10.1002/wnan.1865

Li, Z., Lai, X., Fu, S., Ren, L., Cai, H., Zhang, H., et al. (2022). Immunogenic cell death activates the tumor immune microenvironment to boost the immunotherapy efficiency. Adv. Sci. 9, e2201734. doi:10.1002/advs.202201734

Li, Z., Xu, J., Lin, H., Yu, S., Sun, J., Zhang, C., et al. (2025). Interleukin-15Rα-Sushi-Fc fusion protein Co-Hitchhikes Interleukin-15 and pheophorbide A for cancer photoimmunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 17, 615. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17050615

Liu, Z., Xie, Z., Li, W., Wu, X., Jiang, X., Li, G., et al. (2021). Photodynamic immunotherapy of cancers based on nanotechnology: recent advances and future challenges. J. Nanobiotechnology 19, 160. doi:10.1186/s12951-021-00903-7

Liu, J., Jiang, X., Li, Y., Yang, K., Weichselbaum, R. R., and Lin, W. (2024). Immunogenic bifunctional nanoparticle suppresses programmed cell death-ligand 1 in cancer and dendritic cells to enhance adaptive immunity and chemo-immunotherapy. ACS Nano 18, 5152–5166. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c12678

Lu, Y., Sun, W., Du, J., Fan, J., and Peng, X. (2023). Immuno-photodynamic therapy (IPDT): Organic photosensitizers and their application in cancer ablation. JACS Au 3, 682–699. doi:10.1021/jacsau.2c00591

Mazur, E., Kwiatkowska, D., and Reich, A. (2023). Photodynamic therapy in pigmented basal cell carcinoma—A review. Biomedicines 11, 3099. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11113099

McMorrow, R., de Bruijn, H. S., Farina, S., van Ardenne, R. J. L., Que, I., Mastroberardino, P. G., et al. (2025). Combination of bremachlorin PDT and immune checkpoint inhibitor Anti–PD-1 shows response in murine immunological T-cell–High and T-cell–Low PDAC models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 24, 605–617. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-23-0733

Merchant, S., and Korbelik, M. (2011). Heat shock protein 70 is acute phase reactant: response elicited by tumor treatment with photodynamic therapy. Cell Stress and Chaperones 16, 153–162. doi:10.1007/s12192-010-0227-5

Mroz, P., Hashmi, J. T., Huang, Y. Y., Lange, N., and Hamblin, M. R. (2011). Stimulation of anti-tumor immunity by photodynamic therapy. Expert Review Clinical Immunology 7, 75–91. doi:10.1586/eci.10.81

Mušković, M., Pokrajac, R., and Malatesti, N. (2023). Combination of two photosensitisers in anticancer, antimicrobial and upconversion photodynamic therapy. Pharmaceuticals 16, 613. doi:10.3390/ph16040613

Nasr Esfahani, F., Karimi, S., Jalilian, Z., Alavi, M., Aziz, B., Alhagh Charkhat Gorgich, E., et al. (2024). Functionalized and Theranostic lipidic and tocosomal drug delivery systems: potentials and limitations in cancer photodynamic therapy. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 14, 524–536. doi:10.34172/apb.2024.038

Pan, Q., Chen, M., Li, J., Wu, Y., Zhen, C., and Liang, B. (2013). Antitumor function and mechanism of phycoerythrin from Porphyra haitanensis. Biol. Research 46, 87–95. doi:10.4067/S0716-97602013000100013

Patil, S., mustaq, S., Hosmani, J., Khan, Z. A., Yadalam, P. K., Ahmed, Z. H., et al. (2023). Advancement in therapeutic strategies for immune-mediated oral diseases. Disease-a-Month 69, 101352. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2022.101352

Plekhova, N., Shevchenko, O., Korshunova, O., Stepanyugina, A., Tananaev, I., and Apanasevich, V. (2022). Development of novel tetrapyrrole structure photosensitizers for cancer photodynamic therapy. Bioengineering 9, 82. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9020082

Rajan, S. S., Chandran, R., and Abrahamse, H. (2024). Overcoming challenges in cancer treatment: nano-enabled photodynamic therapy as a viable solution. WIREs Nanomedicine Nanobiotechnology 16, e1942. doi:10.1002/wnan.1942

Reiners, J. J., Agostinis, P., Berg, K., Oleinick, N. L., and Kessel, D. H. (2014). Assessing autophagy in the context of photodynamic therapy. Autophagy 6, 17–18. doi:10.4161/auto.6.1.10220

Relvas, C. M., Santos, S. G., Oliveira, M. J., Magalhães, F. D., and Pinto, A. M. (2023). Nanomaterials for skin cancer photoimmunotherapy. Biomedicines 11, 1292. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11051292

Shen, M., Jiang, X., Peng, Q., Oyang, L., Ren, Z., Wang, J., et al. (2025). The cGAS‒STING pathway in cancer immunity: mechanisms, challenges, and therapeutic implications. J. Hematology and Oncology 18, 40–59. doi:10.1186/s13045-025-01691-5

Shimizu, K., Kahramanian, A., Jabbar, M. A. D. A., Turna Demir, F., Gokyer, D., Uthamacumaran, A., et al. (2023). Photodynamic augmentation of oncolytic virus therapy for central nervous system malignancies. Cancer Lett. 572, 216363. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216363

Singh, T., Bhattacharya, M., Mavi, A. K., Gulati, A., Sharma, N. K., Gaur, S., et al. (2024). Immunogenicity of cancer cells: an overview. Cell. Signal. 113, 110952. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110952

Sorrin, A. J., Kemal Ruhi, M., Ferlic, N. A., Karimnia, V., Polacheck, W. J., Celli, J. P., et al. (2020). Photodynamic therapy and the biophysics of the tumor microenvironment. Photochem. Photobiol. 96, 232–259. doi:10.1111/php.13209

Thibaudeau, C., Bour, C., Scarpi-luttenauer, M., Mesdom, P., Karges, J., Gandioso, A., et al. (2025). Inverse correlation between endoplasmic reticulum stress intensity and antitumor immune response with Ruthenium(II)-Based photosensitizers for the photodynamic therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Med. Chem. 68, 25126–25142. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c02147

Tsung, K., and Norton, J. A. (2006). Lessons from coley's toxin. Surg. Oncol. 15, 25–28. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2006.05.002

Turubanova, V. D., Balalaeva, I. V., Mishchenko, T. A., Catanzaro, E., Alzeibak, R., Peskova, N. N., et al. (2019). Immunogenic cell death induced by a new photodynamic therapy based on photosens and photodithazine. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, 350. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0826-3

Turubanova, V. D., Mishchenko, T. A., Balalaeva, I. V., Efimova, I., Peskova, N. N., Klapshina, L. G., et al. (2021). Novel porphyrazine-based photodynamic anti-cancer therapy induces immunogenic cell death. Sci. Rep. 11, 7205. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86354-4

Vanden Berghe, T., Kalai, M., Denecker, G., Meeus, A., Saelens, X., and Vandenabeele, P. (2006). Necrosis is associated with IL-6 production but apoptosis is not. Cell. Signalling 18, 328–3335. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.003

Wahnou, H., Youlyouz-Marfak, I., Liagre, B., Sol, V., Oudghiri, M., Duval, R. E., et al. (2023). Shining a light on prostate cancer: photodynamic therapy and combination approaches. Pharmaceutics 15, 1767. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15061767

Wang, H., Guo, Y., Wang, C., Jiang, X., Liu, H., Yuan, A., et al. (2021). Light-controlled oxygen production and collection for sustainable photodynamic therapy in tumor hypoxia. Biomaterials 269, 120621. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120621

Wang, D., Jiang, Q., Dong, Z., Meng, T., Hu, F., Wang, J., et al. (2023). Nanocarriers transport across the gastrointestinal barriers: the contribution to oral bioavailability via blood circulation and lymphatic pathway. Adv. Drug Delivery Reviews 203, 115130. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2023.115130

Wang, L., Chelakkot, V. S., Newhook, N., Tucker, S., and Hirasawa, K. (2023). Inflammatory cell death induced by 5-aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy initiates anticancer immunity. Front. Oncol. 13, 1156763. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1156763

Wang, R., Wang, Z., Zhang, M., Zhong, D., and Zhou, M. (2025). Application of photosensitive microalgae in targeted tumor therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 219, 115519. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2025.115519

Wei, D., Huang, Y., Wang, B., Ma, L., Karges, J., and Xiao, H. (2022). Photo-reduction with NIR light of nucleus-targeting PtIV nanoparticles for combined tumor-targeted chemotherapy and photodynamic immunotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201486. doi:10.1002/anie.202201486

Wei, Y., Li, R., Wang, Y., Fu, J., Liu, J., and Ma, X. (2024). Nanomedicines targeting tumor cells or tumor-associated macrophages for combinatorial cancer photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy: strategies and influencing factors. Int. J. Nanomedicine 19, 10129–10144. doi:10.2147/ijn.s466315

Xi, Y., Chen, L., Tang, J., Yu, B., Shen, W., and Niu, X. (2024). Amplifying “eat me signal” by immunogenic cell death for potentiating cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Reviews 321, 94–114. doi:10.1111/imr.13251

Xu, X., Lu, H., and Lee, R. (2020). Near infrared light triggered Photo/immuno-therapy toward cancers. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 488. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00488

Xu, M., Han, X., Xiong, H., Gao, Y., Xu, B., Zhu, G., et al. (2023). Cancer nanomedicine: emerging strategies and therapeutic potentials. Molecules 28, 5145. doi:10.3390/molecules28135145

Xu, C., Cai, X., and Du, L. (2025). A minireview on nanosized hypericin-based inducer of immune cell death under ROS-based therapies. Int. J. Nanomedicine 20, 14695–14705. doi:10.2147/IJN.S566489

Yang, M., Li, J., Gu, P., and Fan, X. (2021). The application of nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy: targeting tumor microenvironment. Bioact. Mater. 6, 1973–1987. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.12.010

Yang, X.-Y., Zhang, J.-G., Zhou, Q.-M., Yu, J.-N., Lu, Y.-F., Wang, X.-J., et al. (2022). Extracellular matrix modulating enzyme functionalized biomimetic Au nanoplatform-mediated enhanced tumor penetration and synergistic antitumor therapy for pancreatic cancer. J. Nanobiotechnology 20, 524. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01738-6

Yang, Y.-C., Zhu, Y., Sun, S.-J., Zhao, C.-J., Bai, Y., Wang, J., et al. (2023). ROS regulation in gliomas: implications for treatment strategies. Front. Immunol. 14, 1259797. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1259797

Yang, G., Pan, X., Feng, W., Yao, Q., Jiang, F., Du, F., et al. (2023b). Engineering Au44 nanoclusters for NIR-II luminescence imaging-guided photoactivatable cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano 17, 15605–15614. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c02370

Yang, J.-K., Kwon, H., and Kim, S. (2024). Recent advances in light-triggered cancer immunotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 12, 2650–2669. doi:10.1039/d3tb02842a

Yang, S., Hu, X., Yong, Z., Dou, Q., Quan, C., Cheng, H.-B., et al. (2024b). GSH-responsive bithiophene Aza-BODIPY@HMON nanoplatform for achieving triple-synergistic photoimmunotherapy. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 242, 114109. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2024.114109

Yin, S., Chen, Z., Chen, D., and Yan, D. (2023). Strategies targeting PD-L1 expression and associated opportunities for cancer combination therapy. Theranostics 13, 1520–1544. doi:10.7150/thno.80091

Yu, Z., Cao, L., Shen, Y., Chen, J., Li, H., Li, C., et al. (2025). Inducing cuproptosis with copper ion-loaded aloe Emodin self-assembled nanoparticles for enhanced tumor photodynamic immunotherapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 14, e2404612. doi:10.1002/adhm.202404612

Yue, B., Gao, W., Lovell, J. F., Jin, H., and Huang, J. (2025). The cGAS-STING pathway in cancer immunity: dual roles, therapeutic strategies, and clinical challenges. Essays Biochemistry 69, 1–13. doi:10.1042/EBC20253006

Zhang, Z., Li, D., Cao, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, F., Zhang, F., et al. (2021). Biodegradable hypocrellin B nanoparticles coated with neutrophil membranes for hepatocellular carcinoma photodynamics therapy effectively via JUNB/ROS signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 99, 107624. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107624

Zhang, M., Zhao, Y., Ma, H., Sun, Y., and Cao, J. (2022). How to improve photodynamic therapy-induced antitumor immunity for cancer treatment? Theranostics 12, 4629–4655. doi:10.7150/thno.72465

Zhang, F., Guo, Z., Li, Z., Luan, H., Yu, Y., Zhu, A. T., et al. (2024). Biohybrid microrobots locally and actively deliver drug-loaded nanoparticles to inhibit the progression of lung metastasis. Sci. Advances 10, 6157. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adn6157

Zhang, J., Zheng, Y., Xu, L., Gao, J., Ou, Z., Zhu, M., et al. (2025). Development of therapeutic cancer vaccines based on cancer immunity cycle. Front. Medicine 19, 553–599. doi:10.1007/s11684-025-1134-6

Zhao, Z., Zhang, H., Zeng, Q., Wang, P., Zhang, G., Ji, J., et al. (2020). Exosomes from 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy-treated squamous carcinoma cells promote dendritic cell maturation. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 30, 101746. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101746

Zhao, X., Du, J., Sun, W., Fan, J., and Peng, X. (2024). Regulating charge transfer in cyanine dyes: a universal methodology for enhancing cancer phototherapeutic efficacy. Accounts Chem. Res. 57, 2582–2593. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00399

Zhao, D., Wen, X., Wu, J., and Chen, F. (2024). Photoimmunotherapy for cancer treatment based on organic small molecules: recent strategies and future directions. Transl. Oncol. 49, 102086. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102086

Zhou, M., Yin, Y., Zhao, J., Zhou, M., Bai, Y., and Zhang, P. (2023). Applications of microalga-powered microrobots in targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials Sci. 11, 7512–7530. doi:10.1039/d3bm01095c

Zhou, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, B., Wang, P., Li, D., Cao, T., et al. (2024). Mitochondria-targeted photodynamic therapy triggers GSDME-mediated pyroptosis and sensitizes anti-PD-1 therapy in colorectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, e008054. doi:10.1136/jitc-2023-008054

Keywords: immunotherapy, mechanism, photodynamic therapy, photosensitiser, tumor

Citation: Cai X, Leung AWN, Lv L and Xu C (2026) A mini-review: photodynamic therapy-induced immune activation. Front. Pharmacol. 17:1746961. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2026.1746961

Received: 15 November 2025; Accepted: 06 January 2026;

Published: 21 January 2026.

Edited by:

Bing Yang, Tianjin Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Ge Hong, Institute of Biomedical Engineering (CAMS), ChinaXin Hu, National Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD), Japan

Copyright © 2026 Cai, Leung, Lv and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chuanshan Xu, eGNzaGFuQDE2My5jb20=; Le Lv, NjM1NzM4MDIzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Xiaowen Cai

Xiaowen Cai Albert Wing Nang Leung3

Albert Wing Nang Leung3 Chuanshan Xu

Chuanshan Xu