- 1Grupo de Estudos em Neuroquímica e Neurobiologia de Moléculas Bioativas, Departamento de Química, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso (UFMT), Cuiaba, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- 2Grupo de Estudos em Terapia Mitocondrial, Instituto de Ciências Básicas da Saúde (ICBS), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

- 3Programa de Pós-Graduação em Alimentação, Nutrição e Saúde (PPGANS), Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

- 4Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Bioquímica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Dimethyl fumarate (DMF; C6H8O4) is an ester of fumaric acid widely used in clinical practice for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis and plaque psoriasis. Beyond its established immunomodulatory actions, DMF is increasingly recognized as a small molecule capable of reshaping cellular redox homeostasis and mitochondrial physiology. Mitochondria are double-membrane organelles that integrate energy metabolism, calcium buffering, and apoptosis regulation, while also generating reactive oxygen species that function as signaling mediators. Given their central role in neuronal survival and function, mitochondrial integrity is a critical determinant of neuroprotection. The aim of this review is to discuss the mechanistic aspects by which DMF influences mitochondrial physiology in central nervous system (CNS) cells, based on evidence from experimental models and patient-derived samples. Data consistently show that DMF activates the Nrf2 pathway, leading to increased expression of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., NQO-1, HO-1) and induction of mitochondrial biogenesis markers (e.g., PGC-1α, NRF1, TFAM). In neurons and oligodendrocytes, DMF enhances respiratory function and limits apoptosis by modulating BCL-2 family proteins and suppressing cytochrome c release. Disease-relevant studies further demonstrate frataxin upregulation in Friedreich’s ataxia and reduction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in C9orf72-related models. Conversely, in microglia, T cells, and vascular cells, DMF may impair mitochondrial respiration or increase apoptosis, particularly under inflammatory stress, suggesting a context-dependent effect. In conclusion, DMF exerts multifaceted and cell type–specific actions on mitochondria. Understanding these mechanisms may guide optimized therapeutic strategies and the identification of biomarkers for precision use in neurological disorders.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT | DMF modulates various biological phenomena related to mitochondrial physiology. This drug can increase or decrease mitochondrial activity, both effects being of pharmacological interest. Furthermore, DMF alters mitochondrial redox biology, potentially promoting or attenuating the production of reactive radical and non-radical species in these organelles. DMF also induces mitochondrial biogenesis (i.e., synthesis of new mitochondria) and mitophagy (i.e., degradation of mitochondria), depending on the context. However, it is known that DMF can act as a mitochondrial toxicant, promoting deleterious effects in healthy cells. Cell fate is modulated by DMF through a mitochondria-dependent action. Although much is known about the mechanisms of action by which DMF interferes with mitochondrial physiology, much remains to be discovered, which may allow this drug to be used in other clinical conditions in which mitochondria play a pathophysiological role. This figure was created by utilizing an image obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1 Introduction

Dimethyl fumarate (DMF) is an α,β-unsaturated ester of fumaric acid, with the molecular formula C6H8O4 and a molecular weight of 144.13 g/mol. Its electrophilic double bond makes it particularly reactive toward nucleophiles, allowing covalent modification of cysteine residues in proteins and glutathione through Michael addition reactions (Majkutewicz, 2022; Bresciani et al., 2023). Despite its pharmacological importance, DMF itself is poorly soluble in water and undergoes rapid hydrolysis in the small intestine, generating its active metabolite, monomethyl fumarate (MMF). Unlike DMF, MMF is detectable in plasma, reaching peak levels within 2–4 h of ingestion. Co-administration with food delays, but does not diminish, its absorption (Majkutewicz, 2022; Blair, 2018). MMF is partly protein-bound and is metabolized to fumaric acid, which enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle before elimination, mainly via exhaled CO2 (Bresciani et al., 2023; Blair, 2018). This chemical and pharmacokinetic profile underlies the suitability of DMF as an orally available therapeutic, paving the way for its diverse clinical applications.

Initially introduced in Germany in the 1950s for the treatment of psoriasis, DMF remains a first-line systemic therapy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (Blair, 2018). Its therapeutic spectrum expanded substantially with the 2013 approval of DMF as a first-line oral agent for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), where it demonstrated significant reductions in relapse frequency, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesions, and disability progression (Fox et al., 2014; Burness and Deeks, 2014). Importantly, interest in DMF has recently shifted beyond these indications. Preclinical and clinical investigations suggest benefits in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), as well as in systemic sclerosis, gut disorders, and cancer models (Majkutewicz, 2022; Bresciani et al., 2023; Manai et al., 2023). The breadth of these applications highlights the pleiotropic actions of DMF and its potential as a drug suitable for repurposing across disease contexts.

The core mechanism by which DMF exerts its effects is through activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway. By modifying cysteine residues in Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), DMF liberates Nrf2, enabling nuclear translocation and transcription of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1) (Bresciani et al., 2023; Fox et al., 2014; Burness and Deeks, 2014). These actions strengthen glutathione synthesis and enhance resistance to oxidative stress. In parallel, DMF suppresses the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Majkutewicz, 2022; Burness and Deeks, 2014; Gillard et al., 2015). This dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory profile is complemented by additional mechanisms: MMF serves as an agonist of the hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCAR2), modulating immune metabolism via the adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase/sirtuin 1 (AMPK/SIRT1) axis (Majkutewicz, 2022; Chen et al., 2014). DMF also succinates glycolytic enzymes such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), thereby shifting immune cell metabolism away from aerobic glycolysis (Majkutewicz, 2022; Kornberg et al., 2018). Furthermore, accumulating evidence links DMF to the regulation of autophagy and mitophagy, underscoring its potential to directly influence mitochondrial quality control (Bresciani et al., 2023). Taken together, these mechanisms illustrate how DMF operates at the crossroads of redox regulation, inflammatory control, and metabolic adaptation.

Pharmacokinetic studies confirm that systemic exposure to DMF itself is negligible due to rapid hydrolysis, while MMF displays dose-proportional kinetics and a half-life of approximately 2 h (Blair, 2018; Lategan et al., 2021). Plasma concentrations peak within 2–2.5 h, and administration with food can reduce gastrointestinal discomfort without affecting systemic exposure (Bresciani et al., 2023). Importantly, the metabolism of DMF and MMF is independent of cytochrome P450 enzymes, minimizing risks of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions (Blair, 2018; Xu et al., 2023). These features make DMF a predictable and relatively safe oral drug, with favorable absorption and elimination profiles supporting its long-term clinical use.

The pharmacological pleiotropy of DMF is expressed through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects. By engaging the Nrf2 pathway, DMF enhances cellular antioxidant defenses and glutathione biosynthesis. At the same time, inhibition of NF-κB rebalances cytokine signaling, promoting a shift from pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 responses toward anti-inflammatory Th2 phenotypes (Blair, 2018; Wu et al., 2017; Mansilla et al., 2019). Beyond immune modulation, DMF has clear implications for mitochondrial health. In vitro studies show that DMF and MMF preserve mitochondrial function by stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production while reducing oxidative injury in astrocytes and neurons (Burness and Deeks, 2014; Rosito et al., 2020). Such actions underscore the relevance of DMF as a modulator of mitochondrial physiology, particularly in disorders where redox imbalance and organelle dysfunction are central to pathogenesis.

Despite its efficacy, DMF therapy is not without challenges. The most common adverse effects are flushing and gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea, especially during early treatment (Blair, 2018; Liang et al., 2020). More concerning is lymphopenia, a reduction in circulating lymphocytes that increases susceptibility to opportunistic infections such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (Majkutewicz, 2022). Other events, including headache, fatigue, and reversible liver enzyme elevations, are generally manageable with careful monitoring (Liang et al., 2020). Thus, while DMF is generally well tolerated, long-term safety requires vigilance through laboratory and clinical follow-up.

Although DMF is well recognized as an immunomodulatory and antioxidant therapy, its broader role in mitochondrial physiology remains less defined. The purpose of this review is to critically examine how DMF influences mitochondrial physiology, including redox biology, bioenergetics, cell fate decisions, mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics (fusion and fission), and mitophagy. By integrating evidence across these processes, this review aims to clarify how DMF-mediated signaling converges on mitochondrial homeostasis, offering new insights into its translational potential for disorders driven by mitochondrial dysfunction. DMF-induced mitochondrial intoxication is also discussed in this work.

2 Overview of mitochondrial physiology

The double-membrane organelles mitochondria are the major source of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and take a role in several other metabolic pathways and biological phenomena necessary to the maintenance of the viability of animal and vegetal cells (Harrington et al., 2023). The oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system, which is responsible for the ATP production, is found in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and is composed of the electron transport chain (ETC.) components (Complex I–IV and the mobile elements coenzyme Q10/ubiquinone and cytochrome c) and of Complex V (ATP synthase/ATPase) (Figure 1) (Papa et al., 2012; Rasheed and Tarjan, 2018; Zorova et al., 2018; Kondadi et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Joubert and Puff, 2021; Harrington et al., 2023). Mitochondria can undergo structural and functional changes through events such as mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial fusion and fission, and mitophagy, as described below.

Figure 1. The oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS). The most important role of OXPHOS is to generate ATP. This system is formed by the electron transport chain (ETC.) and Complex V (also known as ATP synthase or ATPase). The ETC, in turn, is composed of Complexes I (NADH dehydrogenase), II (succinate dehydrogenase), III (coenzyme Q:cytochrome c-oxidoreductase or cytochrome bc1) and IV (cytochrome c oxidase). These complexes are responsible for maintaining, together with the action of mobile elements [such as coenzyme Q10/ubiquinone (CoQ) and cytochrome c (Cyt c)], the flow of electrons from various sources to oxygen gas, which, when reduced by Complex IV, generates water. Complex I receives electrons from the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Complex II receives electrons from succinate (S), which is derived from the Krebs cycle (also called the tricarboxylic acid cycle), generating fumarate (F) and reducing flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) into FADH2. CoQ receives electrons from the Complexes I and II and can also be reduced by electrons originated from the oxidation of fatty acids and glucose (through the work of the electron shuttles). Cyt c carries one electron at a time from Complex III to Complex IV. As electrons flow through the ETC, Complexes I, III, and IV pump protons (H+) into the intermembrane space (IMS), generating an electrochemical gradient across the IMM. Complex V uses the movement of H+ from the IMS to the mitochondrial matrix to generate ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi).

2.1 Mitochondrial biogenesis

Mitochondrial biogenesis (also called mitobiogenesis or mitogenesis), i.e., the synthesis of new mitochondria, can be stimulated by different endogenous agents, including adenosine monophosphate (AMP), oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), cyclic AMP (cAMP), and calcium ions (Ca2+), among other signals (Pfanner et al., 2019) (Figure 2). In that regard, mitochondrial biogenesis is part of the cellular adaptation to exercise, caloric restriction, temperature decline, and diseases, among other physiological contexts (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010; Wang et al., 2023). Increased AMP amounts, which can indicate low ATP levels due to decreased production and/or increased consumption, promote the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), that phosphorylates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a transcription coactivator that translocates to the cell nucleus and stimulates the expression of the nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2, respectively) (Jäger et al., 2007; Fernandez-Marcos and Auwerx, 2011). In the nucleus, NRF1 and NRF2 promote the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a protein that induces the transcription of specific targets in the mitochondria, as well as promotes mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication and condensation (Farge et al., 2014; Kukat et al., 2015). PGC-1α can be activated also by SIRT1, a deacetylase, which is upregulated by NAD+ (Gerhart-Hines et al., 2007; Rodgers et al., 2005). AMPK also upregulates SIRT1 by increasing the levels of NAD+ (Cantó et al., 2009; Fulco et al., 2008). On the other hand, Ca2+ modulate PGC-1α by a mechanism dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) and p38 protein kinase, also leading to mitochondrial biogenesis (Wright et al., 2007). The modulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by cAMP initiates with the activation of protein kinase A (PKA), followed by the phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), that leads to the expression of PGC-1α (Bouchez and Devin, 2019). Mitochondrial biogenesis alters the number, size and mass of the organelles, allowing bioenergetic improvements to respond to stressful conditions (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial biogenesis. The synthesis of new mitochondria is stimulated by several factors, including adenosine monophosphate (AMP), nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NAD+, oxidized form), and calcium ions (Ca2+), among others. These signaling agents activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK, that stimulates p38). In the next steps of each signaling pathway, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a transcription coactivator, is activated and translocates to the nucleus of the cell. Then, the transcription of nuclear respiratory factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2, respectively) is promoted, leading an upregulation in the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM). TFAM migrates to the mitochondria, in which is enhances the synthesis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and the transcription of proteins associated with the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system. The next steps conclude the synthesis of new mitochondria in the cells. Figure created by using an image obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

2.2 Mitochondrial fusion and fission

Mitochondrial fusion (combination of two separate mitochondria leading to the formation of a large organelle) and fission (mitochondrial fragmentation leading to the formation of separate organelles) lead to alterations in the number, form, and size of mitochondria (Shen et al., 2023) (Figure 3). Mitochondrial fusion initiates after the interaction of two mitochondria and the fusion of the OMM in an event that is coordinated by mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1 and MFN2, respectively), which are dependent of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) (Dorn, 2020). After the fusion of the OMM, the IMM of each mitochondria initiates their combination in a process dependent on optic atrophy 1 protein (OPA1), another GTPase (Tilokani et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2023). Cardiolipin, a phospholipid present at high concentrations in the IMM, cooperates with the OPA1-dependent fusion of the IMM (Ban et al., 2018). Mitochondrial fusion is stimulated, for example, when a mitochondrion begins to present dysfunctions (e.g., decreased ATP production, increased production of reactive species) or increase in the levels of markers of chemical damage (such as mtDNA damage and lipid peroxidation) (Chen et al., 2023). Thus, a healthy mitochondrion (which does not present high levels of markers of molecular damage, therefore) fuses with a dysfunctional one, distributing diverse molecular components and preventing the progression of organellar dysfunction (Chen et al., 2023).

Figure 3. Mitochondrial fusion and fission. In mitochondrial fusion, two mitochondria fuse generating one larger mitochondrion. This phenomenon is dependent on the proteins mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2) located in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). MFN proteins mediate the binding and docking of two mitochondria. The fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is mediated by optic atrophy 1 protein (OPA1) by a mechanism associated with cardiolipin. Mitochondrial fission, on other hand, is the event in which one mitochondrion undergoes fission generating two smaller mitochondria. Fission of one mitochondrion is started by an interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum, which causes begins to constrict the mitochondrion. This step is followed by the recruitment of dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) by mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1) to the OMM. Oligomerization of DRP1 leads to the formation of a ring-like structure around the mitochondrion. Other proteins, such as dynamin 2 (DNM2), are recruited to continue the fission of the mitochondrion.

On the other hand, mitochondrial fission leads to the separation of one mitochondrion in two mitochondria (Shen et al., 2023) (Figure 3). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cause the constriction of the mitochondrion by a mechanism involving nucleation and polymerization of actin at the contact sites between the organelles (de Brito and Scorrano, 2010; Friedman et al., 2011; Ji et al., 2015; Manor et al., 2015). After this step, mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1) recruits dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), which oligomerizes and forms a ring-shaped structure around the mitochondrion (Sun et al., 2024). GTP is cleaved and dynamin 2 (DNM2) is recruited to the constriction site, leading to the fission of the OMM (Sun et al., 2024). The fission of the IMM seems to be dependent on Ca2+ and cardiolipin and is mediated by DRP1 in a GTP-dependent manner (Paradies et al., 2019). Two smaller mitochondria are generated after the mitochondrial fission process is completed. Stimulating mitochondrial fission is important because less functional portions of a mitochondrion are eliminated, preventing them from remaining in the organelle, which would cause, among other effects, an increase in the production of reactive species and, consequently, in the levels of redox stress markers (Chen et al., 2023). Smaller and dysfunctional mitochondria, originating from mitochondrial fission, can be degraded in the phenomenon of mitophagy (Kraus et al., 2021).

2.3 Mitophagy

Mitochondrial fission may or not be followed by mitophagy, a phenomenon in which damaged mitochondria is digested by the cell (Wang et al., 2023) (Figure 4). Loss of MMP, mtDNA damage, augmented reactive species production, and accumulation of misfolded proteins, for example, trigger mitophagy by a mechanism associated with the accumulation of serine/threonine PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) in the OMM, followed by its transautophosphorylation at Ser228 (Gan et al., 2022). Then, PINK1 phosphorylates Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, and monomeric ubiquitin, which, in turn, promotes amplification of the activation of Parkin (Harper et al., 2018). Activated Parkin ubiquitinates proteins located in the OMM, including the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), mitochondrial Rho-GTPase 1 (Miro1), and proteins involved in the control of mitochondrial fusion, among others (Birsa et al., 2014; Tanaka et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2023). This event leads to phosphorylation of these proteins by PINK1 and to the amplification of the recruitment of Parkin to the mitochondria, causing an increase in the number of ubiquitin chains in the organelles (Harper et al., 2018). This sequence of chemical modifications allows the interaction of the mitochondria with the autophagy adapters, including sequestosome 1 (p62/SQSTM1), nuclear dot protein 52 (NDP52/CALCOCO2), and optineurin (OPTN), to cite a few (Matsumoto et al., 2011; Thurston et al., 2009; Wong and Holzbaur, 2015). The adapters mediate the interaction of ubiquitinated mitochondria with the phagophores by a mechanism related to microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) present in the membranes of these structures (Johansen and Lamark, 2020). The formation of the autophagosomes, which are double-membrane structures, leads to the fusion of the lysosomes with ubiquitinated mitochondria and the digestion of the organelles (Wang et al., 2023). Alternatively, mitophagy can be triggered by mechanisms independent on the PINK1/Parkin pathway (Wang et al., 2023).

Figure 4. Mitophagy. Mitochondrial dysfunction, i.e., loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP, ΔΨm), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, increased production of reactive species, and/or enhanced levels of misfolded proteins, leads to the accumulation of (PINK1) in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). PINK1 undergoes transautophosphorylation and also phosphorylates Parkin and monomeric forms of ubiquitin. The next steps include ubiquitination of several proteins located in the mitochondria, such as mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1 and MFN2, respectively), by Parkin. The growing ubiquitin chains in mitochondria interact with autophagy adapters, which mediate the binding of ubiquitinated mitochondria with LC3 located in the membrane of the phagophores. This interaction leads to the formation of the autophagosomes, that fuse with lysosomes that are responsible for digesting mitochondria. Figure created by using an image obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

2.4 Mitochondrial redox biology

In addition to being the most important source of ATP for animal cells, mitochondria constantly produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) through ETC (Masuda et al., 2024). Among the ROS, the most prominent are superoxide radical (O2−•), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (•OH) (Lambert and Brand, 2009; Murphy, 2009; Sies et al., 2022). Furthermore, there is data showing that mitochondria can generate reactive nitrogen species (RNS), such as nitric oxide (NO•) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), for example, (Lacza et al., 2009; De Armas et al., 2019). Mitochondrial ROS and RNS exert physiological roles in modulating signaling pathways associated with the control of bioenergetics, stress response, hypoxia adaptation, immune response, and cell death (Sena and Chandel, 2012; Sies et al., 2022; 2024). Elevated levels of ROS and/or RNS can not only cause mitochondrial dysfunction, but also widespread damage to cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (Sies et al., 2017; Cardozo et al., 2023). The antioxidant defenses present in mitochondria can be of the non-enzymatic (such as glutathione - GSH) and enzymatic types (Mailloux, 2018; Marí et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2024). The latter include the enzymes manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), catalase (CAT), different isoforms of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and peroxiredoxin (PRx) (Cao et al., 2007; Holley et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2019).

2.5 Mitochondria and cell death

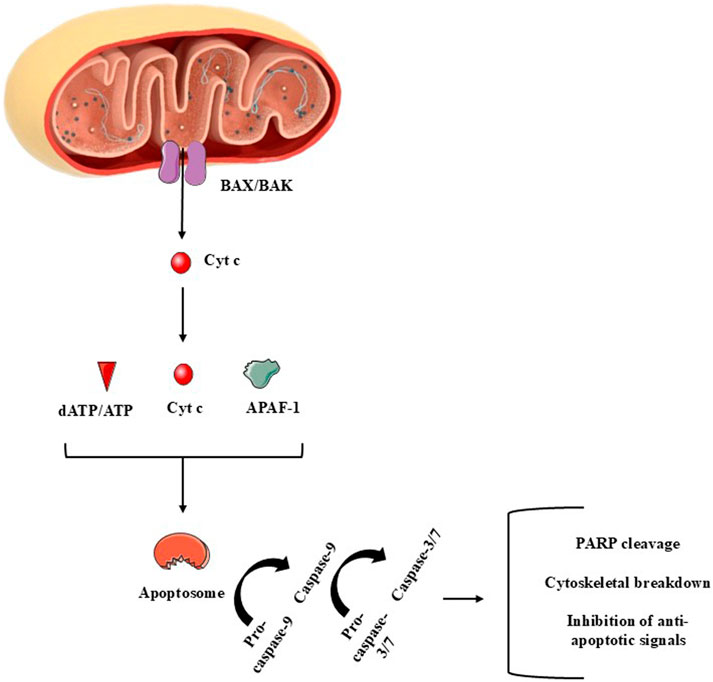

Mitochondria control cell death primarily by integrating stress signals into regulated changes in mitochondrial membrane integrity, metabolism, and signaling output. The central mitochondrial mechanism governing apoptosis is mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), a process tightly regulated by the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) protein family (Bock and Tait, 2020; Czabotar and Garcia-Saez, 2023; Glover et al., 2024). In response to genotoxic, metabolic, or oxidative stress, pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins activate the multidomain effectors BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX) and BCL2 homologous antagonist/killer (BAK), promoting their oligomerization within the outer mitochondrial membrane and formation of proteolipidic pores (Li et al., 2024; Vogler et al., 2025). MOMP enables the release of cytochrome c and other intermembrane space proteins, including second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/direct inhibitor of apoptosis-binding protein with low pI (SMAC/DIABLO, respectively), which together activate the apoptosome [apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (APAF1)/caspase-9 complex) and downstream executioner caspases-3 and -7 (Figure 5). While caspases orchestrate the biochemical dismantling of the cell, mitochondrial dysfunction following widespread MOMP (including loss of membrane potential, impaired OXPHOS, and ATP depletion) can itself drive caspase-independent cell death, underscoring mitochondria as the point of irreversible cellular collapse (Bock and Tait, 2020; Dho et al., 2025).

Figure 5. A summary of major components of the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic cell death (intrinsic apoptotic pathway). The release of cytochrome c (cyt c) to the cytoplasm is mediated by proteins such as BAX, among several others. In the cytoplasm, cyt c reacts with apoptotic peptidase activating factor-1 (APAF-1) and deoxy-ATP (dATP) or with ATP. Pro-caspase-9 is necessary to complete the apoptosome, that activates this initiator enzyme. Once activated, caspase-9 mediates the activation of caspase-3/7, which are called effector caspases due to the several apoptotic roles these enzymes perform during apoptosis. Figure created by using images obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Beyond canonical apoptosis, mitochondria modulate cell fate through quantitative control of MOMP. Sublethal or “minority” MOMP affects only a subset of mitochondria, generating limited caspase activity insufficient to cause immediate death (Liu et al., 2025). This partial mitochondrial permeabilization can induce DNA damage, cellular senescence, or stress-adaptive phenotypes, highlighting mitochondria as regulators of death signaling intensity rather than simple on/off switches (Hall-Younger and Tait, 2025).

Mitochondria also control inflammatory forms of cell death by releasing mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Following extensive membrane remodeling, mitochondrial DNA, cardiolipin, and ROS can escape into the cytosol, activating innate immune pathways such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS/STING, respectively), inflammasomes, and type I interferon signaling (Lin et al., 2022; Glover et al., 2024). Thus, mitochondrial permeabilization links cell death execution to inflammatory signaling.

Collectively, mitochondria govern cell death through coordinated regulation of membrane permeabilization, bioenergetic collapse, caspase activation, and immunogenic signaling, positioning them as central decision-making hubs in cellular fate control.

3 Brain vulnerability to redox stress: Implications for mitochondrial dysfunction and therapeutic modulation

The central nervous system (CNS) operates under uniquely demanding bioenergetic conditions, consuming nearly 20% of the oxygen (O2) originated from inspiration to sustain synaptic transmission, neurotransmitter cycling, and ion homeostasis. This high metabolic rate, coupled with limited antioxidant defenses, makes neurons particularly vulnerable to redox imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction (Cobley et al., 2018; Șerban et al., 2025). The major sources of ROS in the CNS are mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), peroxisomes, and enzyme systems such as NADPH oxidases (NOX), nitric oxide synthases (NOS), xanthine oxidase (XO), and cyclooxygenases (COX) (Lee et al., 2021; Üremiş and Üremiş, 2025). Within mitochondria, the ETC, particularly Complexes I and III, is a predominant site of O2−• generation. This O2−• is rapidly converted by superoxide dismutases (SODs) into H2O2, which can serve as a signaling molecule or, in the presence of transition metals, form •OH through Fenton chemistry (Șerban et al., 2025). NO•, generated by neuronal and inducible NOS (iNOS), is another critical redox mediator; however, excess NO• can react with O2−• to form ONOO−, a potent RNS (Üremiş and Üremiş, 2025; Ferrer-Sueta et al., 2018).

Despite constant exposure to ROS and RNS, CNS relies on an array of antioxidant defenses. Enzymatic systems include SOD isoforms [including copper/zinc-dependent superoxide dismutase (Cu/Zn-SOD) and Mn-SOD], CAT, GPx, and PRx, while non-enzymatic antioxidants include, among others, GSH, melatonin, vitamins C and E, and coenzyme Q10 (Șerban et al., 2025). The Nrf2 pathway orchestrates transcriptional responses to oxidative challenges by inducing antioxidant and detoxification genes (Trofin et al., 2025). However, the CNS exhibits relatively modest antioxidant capacity compared with peripheral tissues, contributing to its vulnerability (Cobley et al., 2018).

Multiple structural and metabolic features explain why the CNS is particularly sensitive to oxidative and nitrosative stress. First, neurons are post-mitotic cells with limited regenerative capacity, making accumulated oxidative damage irreversible (Șerban et al., 2025). Second, neuronal membranes are enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which are highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation, leading to toxic aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (Trofin et al., 2025). Third, the brain contains abundant redox-active metals (iron and copper), which catalyze ROS generation via Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions (Cobley et al., 2018). Fourth, excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate promote Ca2+ overload and excitotoxicity, further stimulating mitochondrial ROS production (Cobley et al., 2018; Trofin et al., 2025). The CNS is also impacted by both autoxidation reactions and neurotransmitter degradation, such as dopamine (Cobley et al., 2018; Umek et al., 2018). These reactions can generate both O2−• and/or H2O2, potentially causing molecular damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, depending on the context (Cobley et al., 2018; Meiser et al., 2013). Last but not least, glucose metabolism is intense in the CNS, favoring the formation and, sometimes, accumulation of derivatives such as methylglyoxal, a highly reactive aldehyde (Cobley et al., 2018). Collectively, these factors, among others, help to explain the redox vulnerability of the CNS.

Mitochondria occupy a pivotal position in CNS redox biology, simultaneously serving as powerhouses and redox regulators (Song et al., 2024). Beyond ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation, they regulate Ca2+ buffering, synthesize steroid hormones and neurotransmitter precursors, and govern cell fate decisions via apoptosis pathways (Lee et al., 2021; Song et al., 2024). Dysfunctional mitochondria not only impair bioenergetics but also amplify ROS and RNS production, creating a vicious cycle that exacerbates oxidative injury (Üremiş and Üremiş, 2025; Zorov et al., 2014). Mitochondria are the dominant, dynamically regulated source of ROS in neurons; Complexes I/III electron leak, redox-coupled shifts during Ca2+ uptake, and metabolic state transitions all tune H2O2 emission that can signal adaptively or tip into damage (Sies and Jones, 2020). Endoplasmic reticulum oxidative folding [which is dependent on protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and endoplasmic reticulum oxidase 1 (ERO1)], peroxisomal oxidases, and NADPH oxidases (e.g., NOX4 at multiple subcellular locales) provide additional ROS streams; inter-organelle contacts propagate redox cues (Shergalis et al., 2020). By contrast, RNS arise primarily from neuronal and glial NOS; NO• modulates synaptic function but, in the presence of O2−•, forms ONOO− that nitrates proteins and impairs respiration (Boczkowski et al., 1999; Brown and Borutaite, 2007). Moreover, mitochondrial-derived H2O2 and O2−• act as signaling molecules that modulate oxidative post-translational modifications (oxPTM) of cysteine residues, influencing redox-sensitive signaling cascades relevant to neuronal survival and plasticity (Sies, 2017).

When ROS and RNS exceed the buffering capacity of antioxidant defenses, oxidative and nitrosative stress arise, damaging proteins, lipids, and DNA (Halliwell, 2006). This imbalance activates pro-inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB signaling, in glial cells, perpetuating neuroinflammation and disrupting the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Trofin et al., 2025; Solleiro-Villavicencio and Rivas-Arancibia, 2018). Neuroinflammation, in turn, exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production, creating a self-sustaining loop (Lin et al., 2022; Peggion et al., 2024). Such processes are central to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, where oxidative damage contributes to amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation; Parkinson’s disease, where oxidative modification of α-synuclein promotes Lewy body formation; multiple sclerosis, where chronic inflammation and demyelination are coupled with mitochondrial stress; and ALS, where mutations in antioxidant enzymes such as SOD1 (that codes for Cu/Zn-SOD) exacerbate ROS accumulation (Șerban et al., 2025; Üremiş and Üremiş, 2025).

Despite recognition of oxidative stress as a unifying mechanism in CNS pathology, clinical trials with broad-spectrum antioxidants have yielded disappointing outcomes (Carvalho et al., 2017; Forman and Zhang, 2021). This failure highlights the dual role of ROS and RNS as both damaging agents and essential signaling molecules (Sies, 2017). Thus, indiscriminate suppression of reactive species may disrupt physiological signaling necessary for neuronal function. A more nuanced approach, targeting specific sources of pathological ROS/RNS (e.g., NOX2 in activated microglia) or restoring redox-sensitive signaling pathways (e.g., Nrf2 activation by dimethyl fumarate), is likely to offer greater therapeutic promise.

4 The effects of DMF on mitochondrial physiology

The mechanisms of action by which DMF affects mitochondrial physiology are not completely clear yet. Moreover, some research groups have reported that DMF failed to significantly modulate mitochondria-related parameters in certain cell types (Silva et al., 2020; Szczesny-Malysiak et al., 2020). Thus, in the present work, the debate is focused on the potential therapeutic targets (i.e., pharmacological candidates) whose modulation by DMF promotes benefits to mitochondria in CNS cells. Mechanistic works are of particular interest due to their importance in a clinical scenario.

4.1 Effects of DMF on mitochondrial function and redox biology in neurological models

The evidence summarized in Table 1 and in Figure 6 highlights the multifaceted actions of DMF on mitochondrial function and redox biology, with implications for neuroprotection and the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Early cellular studies, such as those in dopaminergic CATH. a neurons exposed to tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4, which undergoes autoxidation and enhances the rate of dopamine oxidation and the formation of quinone proteins, which are toxic to brain cells by a mitochondria-dependent manner (Berman and Hastings, 1999; Jana et al., 2011)] demonstrated that DMF enhances respiratory chain activity, particularly Complexes I and IV, while suppressing cytochrome c release (Choi et al., 2006). These findings suggest a dual role in preserving bioenergetic output and preventing apoptosis. The similarity of the effects of DMF with those of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) raises the possibility that its protective mechanism involves redox-sensitive signaling, possibly mediated by GSH metabolism. However, these results are limited by the acute exposure design, which may not fully capture the dynamics of chronic neurodegenerative processes. Moreover, it can be speculated that DMF promoted mitochondrial protection by a mechanism associated with the upregulation of NQO1, a quinone reductase that can metabolize toxic quinones into less reactive agents (Ross and Siegel, 2021). Nonetheless, future research should combine NQO1 knock down with quinone flux analysis to confirm this speculation.

Figure 6. A summary of the effects induced by dimethyl fumarate (DMF) on mitochondrial function and redox biology. DMF stimulates (green triangle) aconitase (an enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid cycle) and Complexes I, II, and IV activity and the flux of oxygen (O2) in the mitochondria of brain cells, probably leading to enhanced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. DMF also caused a decrease (red triangle) in the production of radical superoxide (O2−•) by mitochondria. Additional effects include increased mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number and upregulation of sirtuin 1 (Sirt1), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and cytoprotective enzymes [such as γ-glutamate-cysteine ligase, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1, and heme oxygenase-1 (γ-GCL, NQO1, and HO-1, respectively)]. However, whether Sirt1, Nrf2, and/or cytoprotective enzymes play a role in mitochondrial function and redox biology remains unclear. This figure was created by utilizing an image obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Studies using disease-relevant models further advance the understanding of the mechanisms induced by DMF. In Machado-Joseph disease (MJD) neuroblastoma cells, DMF improved O2 flux, ATP-linked respiration, and maximal uncoupled capacity while reducing mitochondrial superoxide production (Wu et al., 2022). These improvements were accompanied by upregulation of the Nrf2/NQO-1 pathway, reinforcing the notion that DMF acts as a pharmacological activator of antioxidant defenses. Yet, the comparison with the curcumin analog JM17, which exerted stronger antioxidant effects at lower concentrations, suggests that DMF may not be the most potent modulator of mitochondrial oxidative stress, highlighting the need for structure-activity studies to optimize therapeutic analogs.

Patient-derived iNeurons carrying C9orf72 mutations, a model of ALS and frontotemporal dementia, responded to DMF with reduced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) and upregulation of Nrf2 (Au et al., 2024). While these findings align with previous results, they leave unresolved whether Nrf2 activation is causal or correlative in mitochondrial protection. The absence of functional bioenergetic assessments in this study limits its interpretability, particularly since redox improvement does not always equate to enhanced mitochondrial output.

In fibroblasts from Friedreich’s ataxia patients, DMF not only increased Nrf2, NQO-1, and GSH-related enzymes but also induced frataxin expression (Petrillo et al., 2019). The restoration of frataxin, a key protein in mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster assembly (Campbell C. J. et al., 2021), suggests a unique disease-modifying potential of DMF in this context. Importantly, DJ-1 (Parkinsonism associated deglycase, also known as PARK7), another redox-sensitive protein whose levels are decreased in Friedreich’s Ataxia and contribute to a defective Nrf2-dependent signaling (Smith and Kosman, 2020), remained unaffected, indicating that protective scope stimulated by DMF may be selective rather than global across redox modulators. Nonetheless, the study lacked direct measurements of respiratory chain function, leaving unclear whether frataxin induction translates into functional mitochondrial recovery.

Animal models of Friedreich’s ataxia further support the benefits caused by DMF, with treatment increasing frataxin, aconitase activity, and respiratory chain components in multiple tissues (Hui et al., 2021). Interestingly, while some models showed increases in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number, others did not, suggesting a context-dependent regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Moreover, the failure to consistently modulate cytochrome c levels across tissues underscores that the effects promoted by DMF are not uniform. This variability raises important questions about tissue-specific responses, which may have therapeutic implications given the differential vulnerability of brain regions in neurodegenerative diseases.

In a model of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (Abcd1−/− mice), DMF exhibited a broader scope of action, not only upregulating Nrf2 and mitochondrial biogenesis-related genes (Sirt1, Ppargc1a, Nrf1, Tfam) but also increasing ATP production and attenuating inflammatory gene expression (Ranea-Robles et al., 2018). This dual effect on mitochondrial protection and inflammation is particularly relevant, as neurodegenerative disorders are increasingly recognized as disorders of immunometabolic dysfunction (Lonkar et al., 2025). However, it remains unclear whether mitochondrial preservation drives anti-inflammatory effects or whether both outcomes occur in parallel through independent signaling pathways.

Across acute toxicological insults and chronic degenerative milieus, DMF has been consistently associated with improvements in cellular redox balance and selected mitochondrial-related parameters, alongside modulatory effects on inflammatory gene networks. While activation of the Nrf2 pathway represents a well-characterized mechanism in several experimental settings, its direct involvement is not uniformly demonstrated across all models, and in many cases mitochondrial functional endpoints are only partially assessed. Accordingly, reported effects of DMF on mitochondrial homeostasis often rely on indirect redox-sensitive readouts or transcriptional changes rather than comprehensive bioenergetic or dynamic measurements. In this context, auxiliary pathways, including PGC-1α-, SIRT1-, and antioxidant enzyme–related networks (e.g., HO-1 and glutathione metabolism), may contribute to the observed phenotypes in a model- and tissue-dependent manner. The heterogeneity of experimental designs and outcome measures underscores the need for more integrative approaches to delineate whether these pathways operate in parallel, sequentially, or independently of canonical Nrf2 signaling.

4.2 Effects of DMF on mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy

Across neural and peripheral systems, DMF is recurrently associated with the activation of redox-sensitive transcriptional programs that include gene networks classically linked to mitochondrial biogenesis and, in specific contexts, to quality control (Figure 7; Table 2). Rather than uniformly inducing demonstrable expansion of mitochondrial mass, turnover, or function, these responses more consistently reflect engagement of upstream regulatory circuits (i.e., transcriptional or copy-number readouts), most notably those centered on Nrf2, that are commonly interpreted as preparatory or permissive for mitochondrial adaptation. This coherence, therefore, becomes appreciable only when disparate experimental models are interpreted along a shared interpretative framework, rather than a fully unified mechanism.

Figure 7. A summary of the effects induced by dimethyl fumarate (DMF) on mitochondrial biogenesis-related parameters. DMF stimulates (green triangle) peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α), that translocates to the nucleus of the cells and promotes nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) expression. NRF1, together with other regulatory agents, induces the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which in turn migrates to mitochondria and promotes mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) synthesis, indicating mitochondrial biogenesis. DMF also upregulated the expression of subunits of the Complexes of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) stimulation by DMF also plays an important role in the induction of mitochondrial biogenesis, although it is not yet completely understood. Please, read the text for details. This figure was created by utilizing images obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

For instance, in rat oligodendrocyte progenitors, DMF elicited a transient pro-oxidant pulse, characterized by increased mitochondrial O2−• production and reduced MMP, followed by induction of Nrf2, PGC-1α, TFAM, COX1, Mn-SOD, and HO-1 (De Nuccio et al., 2020). The fact that 4-HT (Mn-SOD mimetic) and ZnPP-IX (HO-1 inhibitor) attenuate cytoprotection suggests that low-level oxidative cues are not collateral stress but may function as instructional signals that engage redox-sensitive transcriptional regulators linked to mitochondrial adaptation, rather than unequivocal drivers of mitochondrial biogenesis per se. While this coordinated gene induction is compatible with activation of a biogenic program, the available data primarily substantiate transcriptional engagement rather than direct increases in mitochondrial content or sustained bioenergetic capacity. Such a signaling-based interpretation aligns with the established sensitivity of oligodendroglial cells to redox fluctuations during differentiation and myelin maintenance (Magalhães et al., 2017; Narine and Colognato, 2022).

When extended to human fibroblasts, mouse skeletal muscle and cerebellum, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBCMs) from patients with multiple sclerosis, DMF treatment is similarly associated with increased mtDNA copy number, coordinated induction of nuclear- and mitochondrial-encoded genes (including TFAM, MT-ND2/ND6, SDHA/B, MT-CYB, MT-CO1/2, ATP5B, and MT-ATP6), and enhanced O2 consumption (Hayashi et al., 2017). Collectively, these endpoints are frequently interpreted as evidence of mitochondrial biogenesis; however, in the absence of ultrastructural quantification (e.g., transmission electron microscopy - TEM) or direct assessment of mitochondrial protein synthesis, they are more conservatively viewed as reflecting transcriptional and genomic remodeling. Such changes may represent mitochondrial priming or compensatory gene-expression responses rather than unequivocal expansion of the mitochondrial network.

A similar pattern emerges in the monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)-induced spinal cord injury model, in which DMF increased PGC-1α, NRF1, TFAM, and mtDNA in an Nrf2-dependent manner (Gao et al., 2022). These findings indicate that the transcriptional architecture classically associated with mitochondrial biogenesis remains responsive, even under inflammatory and metabolic stress. Whether these transcriptional changes translate into sustained increases in mitochondrial content or functional throughput under physiological load, however, remains unresolved. Given that Nrf2 regulates HO-1, an enzyme implicated in both mitochondrial signaling (Hull et al., 2016; Navarro et al., 2017) and anti-inflammatory responses (Campbell N. K. et al., 2021), clarifying the role of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis becomes not merely an adjunct question but a necessary step in determining whether DMF’s effects are mechanistically unified across neural injury paradigms.

A similar integrative perspective bridges findings from aging-related paradigms, DMF increased mtDNA copy number, reduced damaged mtDNA, and activated SIRT1, Nrf2, and SOD2 across multiple brain regions (Sadovnikova et al., 2021). Rather than directly establishing de novo mitochondrial biogenesis, these outcomes support a role for DMF in reinforcing mitochondrial genome integrity and antioxidant defenses. Such effects are consistent with modulation of mitochondrial maintenance and fidelity, processes that may indirectly favor functional resilience without necessarily increasing mitochondrial abundance. Yet, without functional assays (e.g., respiration, coupling efficiency, and ROS yield), such structural and genomic improvements remain inferential; thus, morphological quantification and performance testing remain indispensable to confirm mitochondrial biogenesis.

Insights into mitochondrial turnover arise from dopaminergic injury models, where DMF upregulated Nrf2, PINK1, Parkin, BNIP3, Beclin-1, LC3A/B-II, and BCL-2 in the absence of NRF1 induction (Pinjala et al., 2024). This expression profile is compatible with preferential engagement of signaling nodes associated with mitophagy-related pathways rather than coordinated activation of canonical biogenic machinery, i.e., initial removal of dysfunctional mitochondria may precede or condition any subsequent biogenic response (mitochondrial re-population). However, without time-resolved analyses or direct measurements of mitophagic flux, these molecular changes are more appropriately interpreted as modulation of mitophagy-associated signaling rather than confirmation of enhanced mitochondrial turnover.

The dissociation between transcriptional or proteomic remodeling and functional recovery is particularly evident in severe stress models. In piglet cortex following in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA), DMF increased subunits of mitochondrial respiratory complexes and morphology-related proteins without restoring mitochondrial function (Piel et al., 2024). In contrast, porcine cardiac tissue from the same paradigm exhibited improvements in mitochondrial network organization and ultrastructural features. This dissociation underscores that proteomic enrichment of mitochondrial components does not necessarily equate to functional recovery, particularly under conditions of severe energetic collapse.

Translational complexity is further underscored by studies in Friedreich’s ataxia. In patient-derived cells, DMF increases frataxin expression and mtDNA content (Jasoliya et al., 2019), findings that are consistent with transcriptional or genomic modulation but insufficient to confirm induction of mitochondrial biogenesis or involvement of Nrf2 signaling. However, short-term in vivo treatment fails to reproduce these effects in YG8LR mice (Abeti et al., 2022), highlighting the influence of pharmacokinetics, tissue context, and temporal dynamics on the engagement of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial programs.

Taken together, these heterogeneous findings support an interpretative framework in which DMF preferentially engages transcriptional and signaling programs associated with mitochondrial biogenesis, antioxidant defense, and turnover in a context-dependent manner. Yet functional rescue remains variable across models, emphasizing that durable neurological benefit will depend on mechanistic clarification, exposure optimization, and adoption of rigorous flux-based methodologies capable of distinguishing molecular signatures from true mitochondrial recovery. Progression beyond priming toward fully realized mitochondrial remodeling appears variable and frequently unverified by direct functional or structural criteria, underscoring the need for integrative, flux-based validation strategies.

Considering the conceptual continuity that emerges across these diverse models, future research priorities can be articulated in an equally integrated manner. Multi-omics profiling should be coupled with ultrastructural analyses (e.g., TEM) to differentiate genuine mitochondrial biogenesis from transcriptional priming. Mechanistic causality should be tested through genetic (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 knockouts) or pharmacologic disruption of Nrf2, HO-1, and SIRT1, thereby elucidating whether the shared signatures observed across tissues indeed converge upon a unified regulatory axis. Moreover, defining DMF’s hormetic window through dose-time matrices quantifying ROS dynamics, MMP fluctuations, and downstream transcription would anchor mitochondrial adaptation within measurable signaling thresholds. Flux-level assays, including mt-Keima or mito-QC for mitophagy, MitoTimer for turnover, 35S-methionine or puromycin labeling for nascent mitochondrial translation, and TFAM-mtDNA occupancy (ChIP), should replace static proxies wherever possible. Complementary high-resolution respirometry under substrate-inhibitor titrations will further resolve how DMF remodels ATP production, proton leak, and redox balance.

Finally, in vivo studies must incorporate longitudinal designs, BBB-exposure measurements, and cell-type–resolved analyses, especially given the broad preclinical dose range (10–300 mg kg−1). Bayesian pharmacokinetic modeling, informed by fumarate hydrolysis and distribution kinetics, may refine dose–response extrapolation to humans. Comparative analyses of DMF, MMF, and next-generation fumarate esters may ultimately reveal whether mitochondrial benefits and tolerability can be decoupled or optimized for distinct diseases such as MS, PD, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and FA.

Building on the evidence that DMF reshapes mitochondrial quantity and quality through tightly regulated programs of biogenesis and turnover, a broader conceptual role for mitochondria emerges. Rather than acting as passive targets of stress, mitochondria function as integrative signaling hubs that decode redox, metabolic, and inflammatory cues into adaptive cellular decisions. Transient oxidative signals are not merely buffered but translated into coordinated transcriptional, structural, and quality-control adjustments that recalibrate mitochondrial performance under stress. Crucially, these adaptive programs position mitochondria at the crossroads between survival and death. The same organelle network that expands or renews itself to sustain bioenergetic and redox homeostasis also harbors the molecular machinery governing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, cytochrome c release, and caspase activation. Thus, mitochondrial remodeling and apoptotic control are not separable phenomena but interdependent layers of a unified stress-response architecture. Within this framework, mitochondrial signaling emerges not only as a determinant of cellular resilience, but also as a decisive regulator of intrinsic apoptotic pathways, directly linking adaptive mitochondrial states to the molecular execution of cell death.

4.3 Effects of DMF on mitochondria-associated anti-apoptotic effects

As observed across neural and peripheral models, DMF consistently attenuates mitochondria-dependent apoptosis by stabilizing mitochondrial function and reprogramming intrinsic death checkpoints. At the molecular level, this protection is reflected in preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential, rebalancing of BCL-2 family proteins, limitation of cytochrome c release, and suppression of downstream caspase activation. These effects position mitochondria not merely as targets of injury, but as active arbiters of whether stressed cells undergo recovery or engage the intrinsic apoptotic cascade (Figure 8; Table 3).

Figure 8. A summary of the mitochondria-related anti-apoptotic effects induced by dimethyl fumarate (DMF). The DMF-induced stimulation of B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2; green triangle), together with the observed downregulation of BCL2-associated X protein (BAX; red triangle), favors the maintenance of intramitochondrial cytochrome c (cyt c) levels and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Inhibition of cyt c release causes a decrease in the activation of caspases-9 and -3, which would mediate pro-apoptotic actions. The stimulation of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) and the decrease in superoxide radical (O2−•) production promoted by DMF may also play a role in its anti-apoptotic action, as it reduces the chances of oxidation of cardiolipin, a lipid that keeps cyt c associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane. Please, see the text for more details on the mechanisms of action related to the anti-apoptotic role of DMF. This figure was created by utilizing images obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

In 158N oligodendrocytes challenged with oxysterols, DMF stabilized MMP, curtailed O2−• and H2O2 production, limited poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and caspase-3 activation, and reduced nuclear fragmentation (Zarrouk et al., 2017; Sghaier et al., 2019). In human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ1-42, DMF stimulated Akt signaling, restrained cytochrome c release, downregulated BAX, and blocked caspases-9 and -3, despite minimal impact on stress kinases p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), underscoring pathway selectivity upstream of mitochondria (Rajput et al., 2020). These findings highlight selective modulation of mitochondrial checkpoints upstream of executioner caspases. In vivo, DMF lessened apoptotic signaling after spinal cord injury (SCI) (Cordaro et al., 2017), traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Gao et al., 2024), pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizures (Singh et al., 2019), rotenone toxicity (Khot et al., 2023), and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) (Shavakandi et al., 2022), with convergent decreases in BAX, cleaved caspase-3, AIF, and Fas ligand, and increases in BCL-2, collectively indicating modulation of intrinsic apoptotic thresholds.

Redox regulation emerges as a central modulatory theme. DMF stimulated antioxidant defenses (SOD, CAT, GPx-1, and Mn-SOD), restores cardiolipin, and reduces mitochondrial O2−• generation, thereby limiting MOMP and caspase engagement (Sghaier et al., 2019; Cordaro et al., 2017). The increase in cardiolipin is mechanistically notable because it anchors respiratory chain complexes and modulates cytochrome c mobilization, offering a direct route to constrain apoptosis (Li et al., 2025). Contextual variability remains evident, however, as DMF reduces the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and mitochondrial fragmentation in oxysterol-treated oligodendrocytes, a pattern compatible with suppression of autophagy- or mitophagy-associated signaling under acute oxidative stress (Sghaier et al., 2019). Such suppression could be protective during acute oxidative insults but might prove maladaptive if damaged mitochondria require clearance, highlighting the need for precise temporal mapping of mitophagy flux.

Nrf2 signaling repeatedly emerges as a central, though not exclusive, modulatory axis linking redox balance, inflammation, and mitochondrial survival. DMF-induced increases in Nrf2 and downstream effectors such as HO-1 and NQO-1 are accompanied by suppression of NF-κB-dependent cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and inflammatory mediators [myeloperoxidase (MPO)/iNOS] (Cordaro et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2024; Shavakandi et al., 2022). Inhibition of Nrf2 nuclear translocation abrogates several of these effects (Shavakandi et al., 2022), supporting a contributory role for this pathway. Nonetheless, Nrf2 signaling should be viewed as a central modulatory axis rather than a singular causal determinant of mitochondrial protection. Additional associations with TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) and lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) expression (Khot et al., 2023), as well as increased neurotrophic factor [brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3)] levels and benefits from DMF-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells (Cordaro et al., 2017; Babaei et al., 2023), further suggest coordinated modulation of metabolic, lysosomal, and survival pathways that converge on mitochondrial stability.

Despite these convergent trends, substantial heterogeneity persists across models with respect to dose (1–50 µM in vitro; 12.5–100 mg/kg in vivo), timing (pretreatment vs. post-injury), cell type (oligodendrocytes vs. dopaminergic-like vs. mixed brain regions), and outcome measures. For instance, in hippocampal PTZ experiments, executioner caspase activity was reduced without clear shifts in upstream BCL-2 family balance (Singh et al., 2019), whereas in others (SH-SY5Y cells) mitochondrial protection occurs independently of stress-kinase modulation (Rajput et al., 2020). These differences emphasize that DMF biases intrinsic apoptotic thresholds through multiple, context-dependent nodes rather than through a single invariant mechanism.

Collectively, the available evidence positions DMF as a potent modulator of mitochondria-associated apoptotic signaling in neural systems, acting through integrated redox, inflammatory, and intrinsic death-regulatory pathways. While the protective signature is compelling, precise delineation of causal mechanisms and temporal dynamics remains essential to optimize therapeutic translation in neurodegenerative and acute CNS injury settings.

Regarding future investigations, rigorous causality tests are needed, such as genetic Nrf2 (and Keap1) loss-of-function across neural subtypes, live-cell MOMP imaging and cardiolipin tracking, and true mitophagy-flux assays (e.g., mito-Keima) to define when DMF preserves or impairs mitochondrial quality control. Mechanistic dissection of TIGAR and LAMP2 as mediators rather than correlates, and of the role of Akt in blocking cytochrome c release, is warranted. Region-resolved in vivo studies combining neuroinflammation readouts with mitochondrial endpoints, alongside pharmacokinetics/brain penetration and dose–response mapping, will sharpen translational predictions. Finally, testing DMF with pro-mitophagic or neurotrophic co-therapies may reconcile protection with necessary mitochondrial turnover.

4.4 Impairing mitochondrial function with DMF as a therapeutic strategy in neurological disorders

DMF demonstrates how controlled mitochondrial dysfunction can be therapeutically harnessed to reshape immune cell fate. In RRMS, clinical benefit correlates with a mitochondria centric shift in T cell metabolism: routine dosing decreases relapse frequency while dampening oxidative phosphorylation (Gold et al., 2012; Liebmann et al., 2021). High resolution respirometry in patient derived CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes showed that DMF lowers basal and maximal respiratory capacity, collapses spare glycolytic reserve, and remodels cristae architecture, culminating in cytochrome c release and caspase −9 and −3 activation (Liebmann et al., 2021) (Figure 9; Table 4).

Figure 9. A summary of the mechanisms of action by which dimethyl fumarate (DMF) induces mitochondrial dysfunction of pharmacological interest. DMF induces a decrease (red triangle) in the activity of Complex I, in mitochondrial respiration, and in the glycolytic rate (please, see the text for details). Increased mitochondrial superoxide radical (O2−•) production and cytochrome c release, followed by activation of pro-apoptotic caspases, have been observed in different cell types. Changes in mitochondrial mass and architecture, such as organelle swelling, have also been reported in cells exposed to DMF. It remains to be clarified whether the decrease in mitochondrial respiration and changes in the mass and architecture of these organelles play a role in the induction of cell death in cells exposed to DMF. This figure was created by utilizing images obtained from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Paradoxically, DMF hyperpolarized mitochondria while shrinking organelle mass, implying a compensatory tightening of the proton gradient despite curtailed electron flux. This redox imbalanced state amplified O2−• production, yet it is readily reversed by GSH, NAC or mitoquinone mesylate (mitoQ). Rescue of redox poise not only reinstated oxidative phosphorylation but also blocked DMF induced lymphocyte quiescence, highlighting a critical role for redox and/or thiol dependent signaling (Zhang and Forman, 2012; Kukulage et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2024; Vašková et al., 2023). Besides, this data implicates mitochondrial oxidative damage as key mechanistic features of DMF toxicity in immune cells. Measuring GSH pools before therapy may therefore forecast patient sensitivity to DMF.

An analogous metabolic checkpoint operates in innate immunity. In LPS stimulated human microglial clone 3 cells, DMF suppressed iNOS and the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, aligning with its anti-inflammatory profile, while preventing the surge in both glycolytic flux and O2 consumption (Sangineto et al., 2024). This anti-inflammatory effect coincided with impaired mitochondrial respiration, reduced Complex I activity, and decreased reactive species production and lipid peroxidation markers, reflecting a broad dampening of mitochondrial bioenergetics. Notably, no compensatory activity was observed in Complexes II or V, suggesting a non-redundant impairment in mitochondrial electron transport chain function–effects that may be exploited to temper microglial overactivation in neurodegeneration.

Systems level evidence positions the transcription factor Nrf2 at the apex of this response. Beyond antioxidative gene induction, Nrf2 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis, fusion and mitophagy, thereby synchronizing organelle architecture with fluctuating energetic demand (Luchkova et al., 2024). Whether DMF signals through Nrf2 to orchestrate mitochondrial quality control alongside redox homeostasis remains a pressing mechanistic question.

Clinically, the lymphopenia occasionally observed during DMF therapy most likely reflects the same mitochondrial stress response that underpins efficacy (Dinoto et al., 2022). Stratification based on respiratory reserve, GSH/GSSG ratio or Nrf2 dependent gene signatures could predict benefit to risk ratios and guide adjunctive thiol supplementation. In neurodegenerative settings, carefully titrated DMF might recalibrate microglial metabolism without broad immunosuppression, offering neuroprotection through metabolic modulation.

In summary, DMF illustrates that calibrated impairment of mitochondrial bioenergetics can attenuate immune cells activation. In that regard, off-target effects on mitochondrial function merit careful consideration, since the redox-sensitive nature of mitochondria renders them particularly vulnerable to electrophilic stressors such as DMF, especially in non-pathological tissues. Future works should quantify drug induced shifts in mitochondrial GSH, delineate Nrf2 centric transcriptional circuits, and map complex specific respiratory changes across immune subsets, thereby refining the therapeutic window of DMF and inspiring novel mitochondria targeted interventions.

4.5 Mitochondria-associated cytotoxicity induced by DMF in brain cells

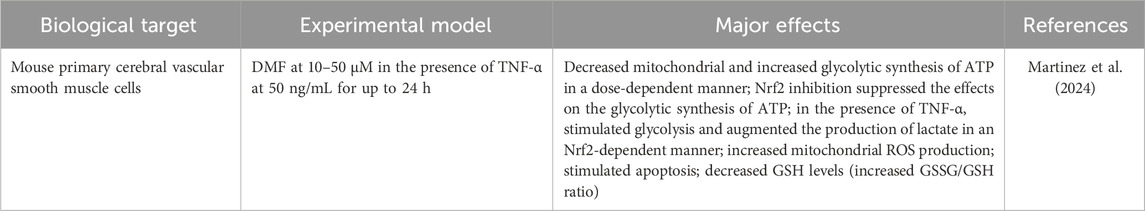

Martinez et al. (2024) reported the effects caused by DMF in mouse primary cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells, alone and with TNF-α, revealing a coordinated shift from mitochondrial to glycolytic ATP production, increased lactate output under inflammatory stimulus, heightened mitochondrial ROS, apoptosis, and glutathione depletion (higher GSSG/GSH) (Table 5). Notably, pharmacologic inhibition of Nrf2 blunts the glycolytic ATP increase, indicating that part of the metabolic rewiring is Nrf2-dependent. These findings align with an electrophile-driven mechanism in which DMF perturbs redox buffering, transiently activating Nrf2 yet simultaneously imposing mitochondrial impairment, manifesting as ROS elevation and apoptosis, particularly when inflammatory signaling is present. The convergence of redox imbalance (GSH consumption), mitochondrial dysfunction (impaired oxidative ATP synthesis, ROS production), and inflammatory cues (TNF-α-augmented glycolysis) supports a model of stress-adaptation failure, where Nrf2-mediated glycolytic compensation is insufficient to prevent cell death under combined insults.

Methodologically, the use of primary cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells strengthens physiological relevance for the neurovascular unit. Besides, translation requires caution, since exposure windows are acute, concentrations may exceed steady-state levels achieved in vivo, and outcomes were captured at the population level without single-cell resolution. The explicit link between mtROS and downstream apoptosis, while plausible, is correlative here and would benefit from targeted rescue experiments (e.g., mitochondria-directed antioxidants or genetic modulation of mitochondrial quality control).

Future work includes, for example, in vivo validation in neuroinflammation models to test cerebrovascular toxicity and barrier integrity, metabolomics/fluxomics to map the Nrf2-dependent rerouting of carbon and nitrogen metabolism, causal tests of mtROS using site-specific ROS modulators and redox-insensitive Nrf2 constructs, dissection of mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy as determinants of cell fate, and stratification of inflammatory contexts (e.g., TNF-α versus mixed cytokines) to define interaction surfaces with DMF.

Together, these results position DMF as a dual-edged electrophile, since it triggers Nrf2-linked glycolytic compensation yet concurrently compromises mitochondrial function and redox homeostasis, tipping cells toward apoptosis under inflammatory stress. This mechanistic tension (adaptation versus injury) should guide risk-benefit assessments for DMF in neurovascular settings.

4.6 Future directions

According to the data previously published by different research groups, it is possible to make the following suggestions as future directions in research related to DMF-induced effects on the mitochondrial physiology of CNS cells:

- Therapeutic window mapping by cell type and inflammatory state. Implement dose–time–inflammation matrices across neurons, astrocytes, oligodendroglia, microglia, and cerebrovascular cells, integrating OCR and extracellular acidification rate, ATP production routes, and apoptosis/mitophagy flux assays (PINK1/Parkin, BNIP3/LC3 turnover). Co-administration with redox modulators should be systematically tested to define rescue ranges and liabilities.

- Mechanistic dissection of Nrf2-centered mitochondrial remodeling. Test causality for Nrf2, NQO1, and downstream pathways (Sirt1-PGC-1α-NRF1-TFAM) using genetic perturbations and pharmacologic inhibitors; resolve whether DMF triggers bona fide mitochondrial biogenesis versus selective turnover (mitophagy) followed by compensatory replication. Include ultrastructural and network-level metrics (TEM, super-resolution, mito-network topology).

- Function over form: link proteomic shifts to electron-transfer capacity. Pair complex subunit abundance with Complex I–IV enzymology, supercomplex assembly, cardiolipin integrity, and ROS site mapping to explain dissociations between biogenetic signatures and respiratory outcomes in stress models.

- Disease-model validation and patient stratification. Extend positive signals (e.g., frataxin induction, reduced mtROS in C9orf72 iNeurons) into organoids and in vivo CNS models, incorporating pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics in brain and spinal cord. Evaluate gender, age, and disease-stage effects, and explore biomarkers (mtDNA copy number, NQO1 induction, TIGAR/LAMP2) to guide precision dosing.

- Immune–mitochondrial cross-talk. In microglia and T cells, delineate how the immunomodulation induced by DMF intersects with bioenergetics (glycolysis-OXPHOS coupling), and whether anti-inflammatory gains can be uncoupled from mitochondrial penalties via schedule or co-therapy optimization.

4.7 Conclusion

Clinical disappointments with generic scavengers (vitamins C/E) highlight a core lesson: CNS redox pathology is not a homogeneous excess of “free radicals” but a compartmental, pathway-specific breakdown involving mitochondria-immune crosstalk. Emerging directions (e.g., mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, Nrf2 activation, modulation of NOX/NOS, nano-delivery, and gene/epigenetic interventions) aim to restore networked redox homeostasis rather than merely quench radicals. Therapeutics that reprogram the Nrf2 axis and mitochondrial resilience should be evaluated with attention to subcellular targeting, patient-specific redox signatures, and inflammatory tone, a precision-redox framework that aligns with current artificial intelligence/multi-omics strategies. DMF exerts a bidirectional influence on mitochondria in CNS-related systems: it frequently activates Nrf2-dependent programs that favor redox resilience, biogenesis markers, and anti-apoptotic signaling in neurons and oligodendroglia, yet it can blunt respiration or promote apoptosis in immune and vascular cells or under heightened inflammation. The totality of evidence argues for a nuanced, context-aware deployment of DMF in neurological disorders, anchored in cell type-specific dosing, stringent functional readouts, and, where appropriate, adjunctive redox buffering to preserve mitochondrial benefits while minimizing liabilities.

Author contributions

MdO: Visualization, Project administration, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. MdO receives a “Bolsa de Produtividade em Pesquisa (Research Productivity Grant) 2-PQ2” fellow from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (protocol number 305775/2024-3). The author would like to thank Fundação de Amparo À Pesquisa no Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS -EDITAL FAPERGS 09/2023 PROGRAMA PESQUISADOR GAÚCHO -PqG) for supporting this work. Public funding agencies did not influence the interpretation of the data or the submission of this work.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author MdO declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abeti, R., Jasoliya, M., Al-Mahdawi, S., Pook, M., Gonzalez-Robles, C., Hui, C. K., et al. (2022). A drug combination rescues frataxin-dependent neural and cardiac pathophysiology in FA models. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 830650. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.830650

Au, W. H., Miller-Fleming, L., Sanchez-Martinez, A., Lee, J. A., Twyning, M. J., Prag, H. A., et al. (2024). Activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and motor phenotypes in C9orf72 ALS/FTD models. Life Sci. Alliance 7 (9), e202402853. doi:10.26508/lsa.202402853

Babaei, H., Kheirollah, A., Ranjbaran, M., Cheraghzadeh, M., Sarkaki, A., and Adelipour, M. (2023). Preconditioning adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with dimethyl fumarate promotes their therapeutic efficacy in the brain tissues of rats with Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 672, 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.06.045

Ban, T., Kohno, H., Ishihara, T., and Ishihara, N. (2018). Relationship between OPA1 and cardiolipin in mitochondrial inner-membrane fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1859 (9), 951–957. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.016

Berman, S. B., and Hastings, T. G. (1999). Dopamine oxidation alters mitochondrial respiration and induces permeability transition in brain mitochondria: implications for Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 73 (3), 1127–1137. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731127.x

Birsa, N., Norkett, R., Wauer, T., Mevissen, T. E., Wu, H. C., Foltynie, T., et al. (2014). Lysine 27 ubiquitination of the mitochondrial transport protein Miro is dependent on serine 65 of the Parkin ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 289 (21), 14569–14582. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.563031

Blair, H. A. (2018). Dimethyl fumarate: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Drugs 78 (1), 123–130. doi:10.1007/s40265-017-0854-6

Bock, F. J., and Tait, S. W. G. (2020). Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 85–100. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0173-8

Boczkowski, J., Lisdero, C. L., Lanone, S., Samb, A., Carreras, M. C., Boveris, A., et al. (1999). Endogenous peroxynitrite mediates mitochondrial dysfunction in rat diaphragm during endotoxemia. FASEB J. 13 (12), 1637–1646. doi:10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1637