The rapid and unprecedented worldwide spread of the novel coronavirus, also termed as 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), has immensely strained the existing healthcare systems (HCSs) throughout the world (1). The frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) (doctors, nurses, paramedics, ambulance personnel) are occupied with the direct diagnosis, treatment, and care of the COVID-19 infected patients and hold the significant responsibility of flattening the pandemic growth curve and reducing the infection fatality rate. Though HCWs would have their Behavioral Immune System continuously active during this pandemic situation (2), excessive workload, the risk of nosocomial transmission, lack of essential resources and specific medical treatment, and frequent encounters with trauma and death have heightened their risk of psychological distress (3) and trauma (4); psychopathology, such as substance use (2); mood disorders, such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression (3); delusional episodes; suicidality (4); and even suicide (5, 6). An eventual rise in the need of mental health services by HCWs is probable as these mental health consequences may remain even after the pandemic remits (7, 8). As the medical professionals are the most significant assets in countering the pandemic, safeguarding the physically and emotionally exhausted (9) HCWs' mental health becomes significant. This opinion article briefly describes the psychopathology encountered by HCWs during the 2019-nCoV pandemic and the protective role “psychological antibodies” constituting the psychological immunity (PI) can have in guarding HCWs against these psychopathological symptoms. Particular attention is drawn toward the need for developing evidence-informed individual- and organizational-level PI-boosting interventions for HCWs.

COVID-19-Linked Psychopathology in HCWs

The medical personnel attending the COVID-19 patients report significantly higher symptoms of somatization, obsession, compulsion, anxiety, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism. Besides, they have significantly lower interpersonal sensitivity and overall poor mental health (10). HCWs also suffer emotional disturbances, such as anxiety and depression, excessive workload, physical and mental exhaustion, burnout, post-traumatic stress symptoms, loneliness, sleep disorders, and distress (3, 11–17). The fear of getting infected and having a sudden role reversal from a healthcare provider to a medical patient leads to the feelings of frustration and helplessness, adjustment issues, perceived stigma, and fear of discrimination (18). HCWs are performing duties outside of perceived skills, experiencing life threats, and witnessing co-worker's serious illness, injury, and death (19), all of which are specific factors that put them at a higher risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) a few months later (20). A timely systematic review and meta-analyses provided evidence that a considerable fraction of HCWs experienced significant levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia during the coronavirus pandemic (21). The frontline HCWs in the department of respiratory medicine, emergency, intensive care unit (ICU), and infectious disease have 2-fold chances of experiencing anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems compared with the non-clinical staff (15, 22, 23). The infection rate among medical staff (24), fear of infection to colleagues and family, protective measures, and medical violence further add to HCWs' psychological issues (25). These mental issues can potentially lead to medical treatment errors, patient mortality, substance abuse, and even suicidal ideation among HCWs. Thus, “Healing the Healer” (26) becomes crucial. In addition to these potential hazards that exceed the consequences of COVID-19 itself (27), the accumulated psychological pressure and the intense fear of death during the pandemic even pushed the already vulnerable medical professionals into committing suicide (5, 6). Though researchers (9, 17, 22) indicate a need for effective strategies, mental health informed interventions, and regular intensive training for HCWs, evidence-based evaluations and potential mental health interventions targeting frontline HCWs are relatively scarce (3, 28). Further, till date, neither any clinician-administered scale for measuring psychological distress or disorders in the COVID-19 context (29) nor any specific recommendations from the international bodies on the addressal of the mental health concerns during the pandemic are available (30). Identifying the personal resilience resources that mitigate stress can aid in the rapid design of evidence-informed individual- and organizational-level interventions for HCWs.

Psychological Antibodies and the Psychological Immune System

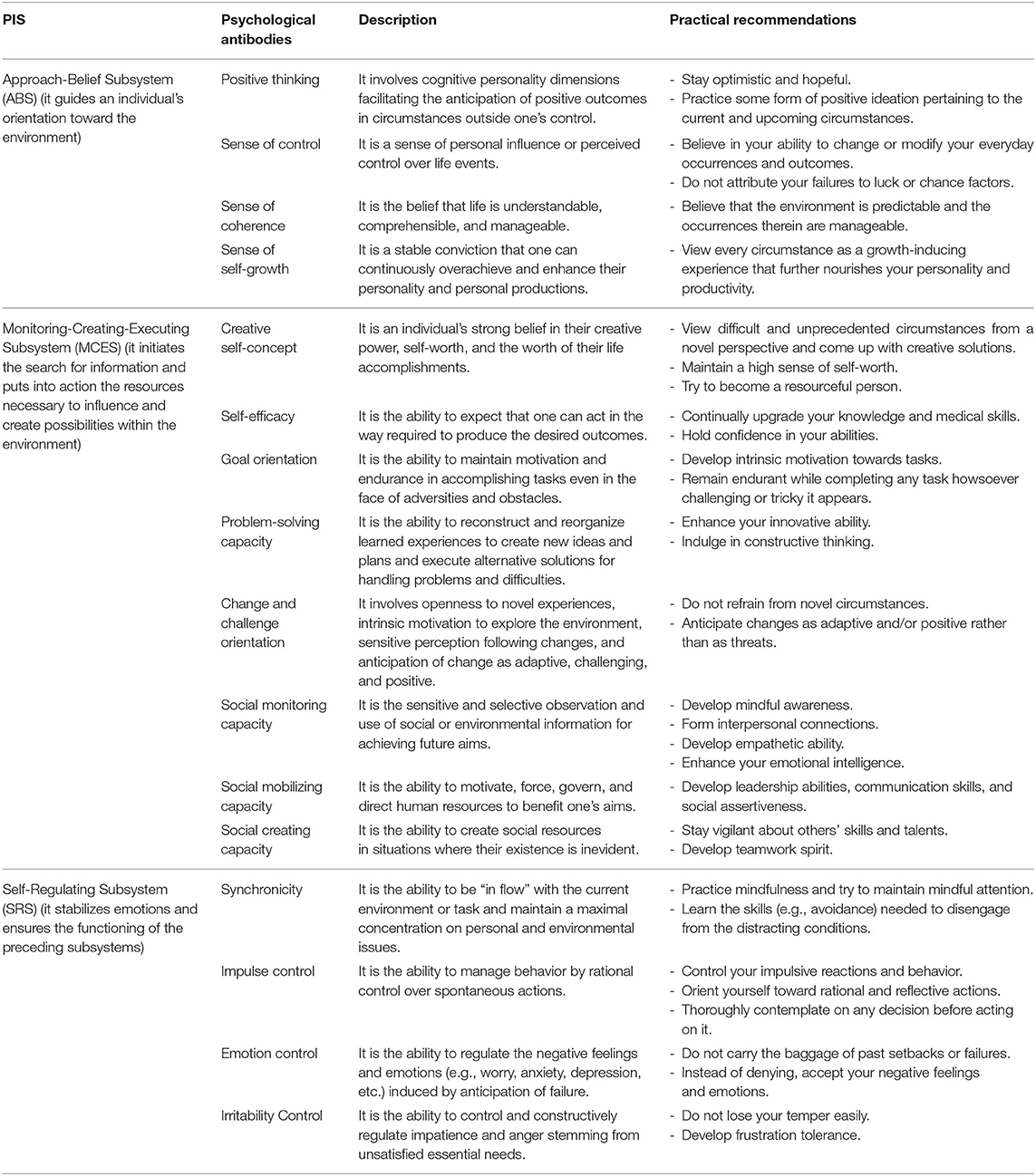

The concept of the Psychological Immune System (PIS) was proposed by Olah (31) to integrate the isolated but empirically correlated character strengths and stress-resistant resources of the personality into one comprehensive system. PIS is a multidimensional yet integrated unit of personal resilience resources and adaptive capacities, also referred to as “psychological antibodies” (32), that provide immunity against damage, stress (33), and traumatic events (34). Table 1 briefly describes the three subsystems entailed in the PIS and their respective psychological antibodies. During the coping process, these subsystems dynamically interact and regulate one another's functioning and guide the person to use flexible and self-developing coping strategies (35, 36).

Table 1. Subsystems of the psychological immune system, their respective antibodies, and practical recommendations for enhancing healthcare workers' psychological immunity.

Psychological Immunity: A Counter to COVID-19-Related Psychopathology

Prior studies assessing psychological immunity (PI) protective potentials (psychological antibodies) in high-stress occupation personnel, such as emergency nurses (37), medical professionals (32), and military soldiers (38), have yielded promising results. PI holds a strong positive correlation with life satisfaction and well-being dimensions (environmental mastery, purpose in life, personal growth, self-acceptance, positive relations, and autonomy) and a negative correlation with burnout (33). The antibodies, sense of control (SOC), sense of self-growth, synchronicity, impulse, emotion, and irritability control are strongly correlated with mental and physical health (33). Positive thinking, SOC, and sense of self-growth mediate the psychological adjustment–mental health linkage in instances of acute psychopathology (39). The personality resources comprising PIS significantly predict the level of satisfaction in gymnasts (40). Approach-Belief Subsystem (ABS) and Monitoring–Creating–Executing Subsystem (MCES) correlate positively with the hope of attaining goals, and the entire PIS correlates positively with life satisfaction and negatively with depression (41). There also exists a strong correlation between PI and life expectancy (42).

PI, and the psychological antibodies therein, can provide HCWs effective coping against stress and guard them against psychopathology. Positive thinking educational intervention and training via social media reduce nurses' job stress (43) and enhance their quality of work-life (44). It is plausible as positive thinking entails optimism and hopefulness, which influence the primary appraisal process and the perception of person-situation transactions. While low job control associates with increased sickness absence in hospital physicians (45), control over work and significant levels of autonomy bear a protective effect on mental health (46, 47). A study on female nurses found that SOC is a protective factor for depressive state, burnout, and job dissatisfaction and can be a health-promoting resource (48). A sense of self-growth promotes openness and assimilation of the new experiences and strongly motivates self-actualization and self-expansion. Personal growth has significant association with role boundary, role insufficiency, role ambiguity, and interpersonal, psychological, and physical strain (49). Thus, the HCSs shall maintain an increased workforce and ensure that their HCWs have well-defined duties, shorter working periods, flexible schedules, shift duties, regular breaks, and supervisor support. Studies with HCWs have shown that self-concept underlies the development of the professional self-concept (50). Hence possessing a high creative self-concept will enable HCWs to bear a positive outlook and success orientation toward most situations they encounter. Contrarily, a low level of self-efficacy in HCWs during the 2019-nCoV pandemic associates with heightened stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia (24) and is a risk factor for loneliness (51). A study on emergency room (ER) nurses found that goal orientation explains considerable variance in burnout and work engagement, with mastery-approach goal orientation being particularly beneficial (52). Health professionals using problem-solving-related strategies and positive re-assessment do not report any health problems and have a better emotional state than those employing other coping strategies (53). Challenge orientation negatively predicts burnout and secondary traumatic stress (compassion fatigue) in palliative care nurses (54). Thus, promoting this antibody can help reduce psychological distress and burnout in HCWs. Those with high social monitoring, mobilizing, and creating capacities have openness for contact with people, are socially assertive, and possess communication abilities. HCWs display reluctance to participate in the psychological interventions developed for them (55). Promoting these antibodies will benefit in inhibiting their hesitance to seek help or discuss their problems with a counselor or mental health professional. Synchronicity, impulse, emotion, and irritability control regulate emotions and prevent any emotional dysregulation or dissonance. The COVID-19 pandemic has made HCWs prone to emotional disturbances, vicarious trauma, and irritability (56, 57). Enhancing these antibodies, incredibly emotion and irritability control, in HCWs will enable them to use their frustration and anger constructively.

Table 1 provides some practical recommendations that can assist the HCWs in enhancing their PI and the intervention developers in designing effective PI-boosting interventions for HCWs. The medical workers with higher mental health problems report poor self-perceived physical health as well. Contrarily, the access to psychological aid (materials/ resources) is inversely related to the proportion of mental health problems (58). With this in view, researchers indicate the need for regular screening and timely addressal of psychological health concerns among HCWs, preferably through psychotherapeutic means (14, 59). As PI can be modified by psychotherapeutic interventions (34), developing evidence-informed, tiered, and tailored PI-boosting interventions will help protect the “protectors” from being victimized by the pandemic.

Author Contributions

YA, AJ, and TS conceptualized the theme and prepared the final manuscript draft. AJ wrote the first draft. TS and YA reviewed and commented on the initial draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, Pulla P, Smith P, Rada AG. Covid-19: how doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ. (2020) 368:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1090

2. McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Substance use and abuse associated with the behavioral immune system during COVID-19: the special case of healthcare workers and essential workers. Addict Behav. (2020) 110:106522. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106522

3. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

4. Pereira-sanchez V, Adiukwu F, Hayek S El, Bytyçi DG, Gonzalez-diaz JM, Kundadak GK, et al. Correspondence COVID-19 effect on mental health : patients and workforce. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e29–30. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30153-X

5. Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: from medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:23–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.032

6. Papoutsi E, Giannakoulis VG, Ntella V, Pappa S, Katsaounou P. Global burden of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. ERJ Open Res. (2020) 6:00195–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00195-2020

7. Scarisbrick DM, Miller LE, Iii JJM. Mental health practitioners ' immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic : observational questionnaire study. JMIR Mental Health. (2020) 7:e21237. doi: 10.2196/21237

8. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Euro Psychiatry 63:1–2. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35

9. Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Heal. (2020) 8:e790–8. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7

10. Xing J, Sun N, Xu J, Geng S, Li Y. Study of the mental health status of medical personnel dealing with new coronavirus pneumonia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233145

11. Cheung T, Fong TKH, Bressington D. COVID-19 under the SARS cloud: mental health nursing during the pandemic in Hong Kong. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs. (2020). doi: 10.1111/jpm.12639. [Epub ahead of print].

12. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and Panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. (2020) 49:1–3.

13. Liu Z, Han B, Jiang R, Huang Y, Ma C, Wen J, et al. Mental Health Status of Doctors and Nurses During COVID-19 Epidemic in China (2020). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3551329

14. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:228–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

15. Lin K, Yang BX, Luo D, Liu Q, Ma S, Huang R, et al. The mental health effects of COVID-19 on health care providers in China. Am J Psychiatry. (2020) 177:635–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20040374

16. Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacioglu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130

17. Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller SG. COVID-19-pandemie : Belastungen des medizinischen Personals Ein kurzer aktueller Review COVID-19 pandemic : stress experience of healthcare workers. Psychiatr Prax. (2020) 47:190–7. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551

18. Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080

19. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Assoc. (2020) 323:2133–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893

20. Schreiber M, Cates DS, Formanski S, King M. Maximizing the resilience of healthcare workers in multi-hazard events: lessons from the 2014-2015 ebola response in Africa. Mil Med. (2019) 184:114–20. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy400

21. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:901–7. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3594632

22. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936

23. Cai Q, Feng H, Huang J, Wang M, Wang Q, Lu X, et al. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.031

24. Spoorthy MS. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

25. Dai Y, Hu G, Xiong H, Qiu H, Yuan X, Yuan X, et al. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. MedRxiv. [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20030874

26. Wong AH, Pacella-LaBarbara ML, Ray JM, Ranney ML, Chang BP. Healing the healer: protecting emergency health care workers' mental health during COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med. (2020) 76:379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.041

27. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. (2020) 395:e37–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3

28. Ransing R, Adiukwu F, Pereira-sanchez V, Ramalho R, Orsolini L, Luiz A, et al. Mental health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic : a conceptual framework by early career psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102085. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102085

29. Ransing R, Ramalho R, Orsolini L, Adiukwu F, Gonzalez-Diaz JM, Larnaout A, et al. Can COVID-19 related mental health issues be measured? Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.049

30. Kar SK, Yasir Arafat SM, Kabir R, Sharma P, Saxena SK. Coping with mental health challenges during COVID-19. In: Saxena SK, editor. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Singapore: Springer Singapore. p. 199–213.

31. Oláh A. A megküzdés személyiségtényezöi: a pszichológiai immunrendszer és mérésének módszere. Kézirat. (Personality factors of coping: The Psychological Immune System and its Measurement) (Ph.D. dissertation), Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary (1996).

32. Dubey A, Shahi D. Psychological immunity and coping strategies: a study on medical professionals. Indian J Soc Sci Res. (2011) 8:36–47.

33. Oláh A. Psychological immunity: a new concept of coping and resilience. In: Coping & Resilience International Conference. Dubrovnik–Cavtat (2009).

34. Adrienn V, Emese J, Alexandra P, Éva B. The characteristics and changes of psychological immune competence of breast cancer patients receiving hypnosis, music or special attention. Mentalhig es Pszichoszomatika. (2019) 20:139–58. doi: 10.1556/0406.20.2019.009

36. Oláh A, Szabó T, Mészáros V, Pápai J. Ways of talent detection development in sports. In: Kurimay T, Faludi VR, editors. A Sport Pszichológiája. Fejezetek a Sportlélektan és Határterületeirol I. Kárpáti, Budapest: Oriold és Társai Kft. (2012).

37. Gombor A. Burnout in Hungarian and Swedish Emergency Nurses: Demographic Variables, Work-Related Factors, Social Support, Personality, and Life Satisfaction as Determinants of Burnout. (Ph.D. dissertation), University of Eötvös Lorand, Budapest, Hungary (2010). Available online at: http://www.pszichologia.phd.elte.hu/vedesek/2010/Burnout.pdf

38. Hullám I, Gyorffy Á, Végh J, Furész J. Psychological study of burdening effects of military activities in survival camp circumstances. Medicine. (2006) 5:615–43. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00149

39. Mirnics Z, Heincz O, Bagdy G, Surányi Z, Gonda X, Benko A, et al. The relationship between the big five personality dimensions and acute psychopathology: mediating and moderating effects of coping strategies. Psychiatr Danub. (2013) 25:379–88.

40. Bóna K. An exploration of the psychological immune system in Hungarian gymnasts, (Master's thesis), Sport and Exercise Psychology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland (2014). Accessed online at https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/44547/URN%3aNBN%3afi%3ajyu-201411063185.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

41. Voitkane S. Goal directedness in relation to life satisfaction, psychological immune system and depression in first-semester university students in Latvia. Balt J Psychol. (2004) 5:19–30. doi: 10.1037/e629932012-003

42. Oláh A, Nagy H, Tóth KG. Life expectancy and psychological immune competence in different cultures. Empir Text Cult Res. (2010) 4:102–8.

43. Kooshalshah SFR, Hidarnia A, Tavousi M, Shahmohamadi S, Aghdamizade S. Effect of positive thinking intervention on the nurses' job stress. Acta Med Mediterr. (2015) 31:1495–500.

44. Motamed-Jahromi M, Fereidouni Z, Dehghan A. Effectiveness of positive thinking training program on nurses' quality of work life through smartphone applications. Int Sch Res Not. (2017) 2017:4965816. doi: 10.1155/2017/4965816

45. Kivimäki M, Sutinen R, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Räsänen K, Töyry S, et al. Sickness absence in hospital physicians: 2 year follow up study on determinants. Occup Environ Med. (2001) 58:361–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.6.361

46. Stansfield S, Head J, Marmot M. Work Related Factors and Ill Health: The Whitehall II Study (2000). Contract Research Report. Available online at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/crr_pdf/2000/crr00266.pdf

47. Graham J, Ramirez AJ. Mental health of hospital consultants. J Psychosom Res. (1997) 43:227–31. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00016-0

48. Masanotti GM, Paolucci S, Abbafati E, Serratore C, Caricato M. Sense of coherence in nurses: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1861. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061861

49. Kumar A, Bhat PS, Ryali S. Study of quality of life among health workers and psychosocial factors influencing it. Ind Psychiatry J. (2018) 27:96–102. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_41_18

50. Sabanciogullari S, Dogan S. Professional self-concept in nurses and related factors: a sample from turkey. Int J Caring Serv. (2017) 10:1676–84.

51. Jiang N, Jia X, Qiu Z, Hu Y, Yang F, Wang H, et al. The Influence of Health Beliefs on Interpersonal Loneliness Among Front-Line Healthcare Workers During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China: A Cross-Sectional Study (2020). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3552645

52. Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Association of goal orientation with work engagement and burnout in emergency nurses. J Occup Health. (2015) 57:151–60. doi: 10.1539/joh.14-0069-OA

53. Koinis A, Giannou V, Drantaki V, Angelaina S, Stratou E, Saridi M. The impact of healthcare workers job environment on their mental-emotional health. Coping strategies: the case of a local general hospital. Heal Psychol Res. (2015) 3:12–13. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2015.1984

54. Frey R, Robinson J, Wong C, Gott M. Burnout, compassion fatigue and psychological capital: findings from a survey of nurses delivering palliative care. Appl Nurs Res. (2018) 43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.003

55. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e15–6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X

56. Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, Feng J, Qiao M, Jiang R. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:916–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007

57. Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. [Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. (2020) 38:192–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121094-20200219-00063

58. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

Keywords: psychological antibodies, COVID-19 pandemic, psychopathology, psychological immunity, frontline healthcare warriors

Citation: Jaiswal A, Singh T and Arya YK (2020) “Psychological Antibodies” to Safeguard Frontline Healthcare Warriors Mental Health Against COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Psychopathology. Front. Psychiatry 11:590160. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590160

Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020;

Published: 18 December 2020.

Edited by:

Carlo Lai, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Laura Orsolini, University of Hertfordshire, United KingdomCopyright © 2020 Jaiswal, Singh and Arya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tushar Singh, dHVzaGFyc2luZ2hhbGxkQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Aishwarya Jaiswal

Aishwarya Jaiswal Tushar Singh

Tushar Singh Yogesh Kumar Arya

Yogesh Kumar Arya