- 1Disparities Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, United States

- 4Department of Health Policy, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Population aging in the US and its increase in racial/ethnic diversity has resulted in a growing body of literature aimed at measuring health disparities among minority older adults. Disparities in health outcomes are often evaluated using self-reported measures and, to attend to linguistic diversity, these measures are increasingly being used in languages for which they were not originally developed and validated. However, observed differences in self-reported measures cannot be used to infer disparities in theoretical attributes, such as late-life depression, unless there is evidence that individuals from different groups responded similarly to the measures—a property known as measurement invariance. Using data from the Positive Minds-Strong Bodies randomized controlled trial, which delivered evidence-based mental health and disability prevention services to a racially/ethnically diverse sample of minority older adults, we applied invariance tests to two common measures of anxiety and depression (the GAD-7 and the HSCL-25) and two measures of level of functioning (the Late-Life FDI and the WHODAS 2.0) comparing four different languages: English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese. We found that these measures were conceptualized similarly across languages. However, at the item-level symptom burden, we identified a non-negligible number of symptoms with some degree of differential item functioning. Spanish speakers reported more worry symptoms and less somatic symptoms for reasons unrelated to their psychological distress. Mandarin speakers reported more feelings of restlessness, and both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported no interest in things more often for reasons unrelated to their psychological distress. Mandarin and Cantonese speakers were also found to consistently report more difficulties performing physical activities for reasons unrelated to their level of functioning. In general, invariance tests have been insufficiently applied within psychological research, but they are particularly relevant as a prerequisite to accurately measure health disparities. Our results highlight the importance of conducting invariance testing, as we singled out several items that may require careful examination before considering their use to compare symptoms of psychological distress and level of functioning among ethnically and linguistically diverse older adult populations.

Introduction

Fueled by low fertility and increased life expectancy, the population aged 65 and over is projected to increase 150% worldwide by 2050 (1). Consistent with this pattern, the US population aged 65 and over is expected to double by 2050 and to become more ethnically diverse, with racial/ethnic minority older adults projected to make up 39.1% of the 65 years and over population compared to 20.7% in 2012 (2). Since late-life mental illnesses—particularly depression—and associated comorbidities (e.g., cognitive decline and disability) are common health problems in US older adults, population aging and its increase in racial/ethnic diversity has resulted in a growing body of literature aimed at measuring health disparities in these populations (3). These studies have revealed that racial/ethnic US minority older adults are at increased risk for severity, persistence and recurrence of psychiatric disorders (4–7) and at increased risk of functional limitations, impairment and disability (8).

Notwithstanding the importance of recognizing racial/ethnic health disparities among older adults, most research studies characterizing these populations make the underlying—yet testable—assumption that the instruments measuring health outcomes are interpreted similarly across cultures, a property known as measurement invariance. Measurement invariance evaluates the extent to which the items within an assessment instrument capture the same underlying construct either across distinct groups or time periods. Although researchers are often interested in cross-group or cross-time comparisons, it is not yet common to present evidence that those comparisons are based on comparable measures (9, 10). Moreover, psychological studies of measurement invariance comparing more than two groups are even less common. For example, from 126 invariance studies published between March 2013 and April 2014 in the APA's PsycNet database, Putnick and Bornstein (11) found that only 25% of invariance tests compared more than two groups.

Consider a simple example of potential consequences of measurement non-invariance. Suppose we wanted to compare Latinos and non-Latino English Speakers on distress by asking about heart pounding, crying easily, headaches, and feeling lonely. While these symptoms might be related to distress in both groups, the first two might be more easy for Latinos to admit than English Speakers for cultural reasons; moreover, in some samples there might be some instances of heart pounding and crying easily that are related to religious experiences rather than distress (12). As a result, if we compare Latinos and non-Latino English Speakers on a composite of these symptoms, the Latino group could incorrectly appear more distressed than the non-Latino White group because of symptom response styles, even though distress levels might actually be the same in both groups.

Since adequate statistical power to detect non-invariance depends upon the number of observations in each group being compared (13, 14), a major barrier to conducting invariance studies comparing more than two groups may be lack of adequate power. Invariance studies comparing many groups are thus particularly suitable for large-scale international surveys, which can include hundreds of thousands of observations. Cieciuch et al. (15), for example, evaluated invariance in a values scale using 274,447 respondents from 15 countries and six time periods (average group size = 3,049) from the European Social Survey (15). In contrast, psychological studies of invariance are often constrained by smaller samples. In the same review mentioned above, Putnick and Bornstein (11) also found a median total sample size of 725 observations. This would result in a relatively small group size (N ≈ 180) if, for example, the most prevalent US racial/ethnic groups were compared (English Speakers, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians). Given that racial/ethnic minorities have generally been underrepresented in randomized trials within psychiatry and psychology (16), sample sizes using data from randomized trials are in practice likely to be much smaller.

Despite sample size limitations, invariance testing of psychological constructs among racial/ethnic minorities is critical because health disparities are often measured using self-reported measures (17) and, to attend to linguistic diversity, these measures are increasingly being used in languages for which they were not originally developed and validated (18). Eliminating racial/ethnic health disparities has also become part of the national agenda (19). In addition, federal authorities have encouraged medical researchers to attend to diversity and inclusiveness in their work (3), creating numerous programs and policies intended to reduce disparities (20). However, racial/ethnic differences in self-reported measures cannot be used to infer disparities in theoretical attributes (e.g., late-life depression) and develop public health policies unless there is evidence that individuals from different groups responded similarly to the measures.

In the present study, we apply invariance tests to psychological measures in a sample of US minority older adults (60+ years old) using two common measures of anxiety and depression symptoms—the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale [GAD-7 (21)] and the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 [HSCL-25 (22, 23)]—and two measures of level of functioning—the Function Component of the Late Life Functioning and Disability Instrument [Late-Life FDI (24)] and the 12-item version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 [WHODAS 2.0 (25, 26)]. We examine the psychometric structure of the items that make up these measures when they were administered in four languages, using data from the Positive Minds-Strong Bodies (PMSB) randomized controlled trial (27). The PMSB trial was an evidence-based mental health and disability prevention intervention, which was delivered to a racially/ethnically diverse sample of 307 minority older adults in English (N = 66; 21.5%), Spanish (N = 138; 45.0%), Mandarin (N = 48; 15.6%), and Cantonese (N = 55; 17.9%).

Because the assessment instruments used to evaluate the effectiveness of PMSB were also applied in four languages based on participants' preference (27), invariance testing was performed comparing language groups. Almost all White and Black participants responded to the assessments in English (93.5 and 95.8%, respectively), almost all Latino participants responded in Spanish (95.6%) and almost all Asian participants responded in Mandarin or Cantonese (99.0%; see Table 1). Thus, analyzing language groups was almost equivalent to analyzing distinct races/ethnicities for Spanish, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, but not for English speakers. However, in contrast with previous studies comparing racial/ethnic groups assessed in the same language [e.g., Vyas et al. (7)], the PMSB trial included minority older adults that would have otherwise been excluded (i.e., non-English speakers). To remain consistent with the design of the intervention (and because of very small samples within the White and Black racial groups), invariance tests were implemented comparing languages instead of race/ethnicity groups.

Methods

Setting and Study Sample

Participants for the PMSB trial were recruited from clinical sites and community-based organizations in Massachusetts, New York, Florida and Puerto Rico between May 2015 and May 2018 (27). Research assistants approached potential participants in-person to administer a short screener after assessing their capacity to consent. A full screener was administered if participants were 60+ years old and spoke either English, Spanish, Mandarin or Cantonese. Eligible participants had screening measures indicative of mild to severe depressive or anxiety symptoms—scored five or more on either the Patient Health Questionnaire (28), the Geriatric Depression Scale (29) or the GAD-7 (21)—and reported some degree of mobility limitations—Short Physical Performance Battery scores between three and 11 (30). Participants disclosing serious suicide plans or attempts were referred to emergency health services and rescreened 30 days after; they were eligible if found to be non-suicidal, and ineligible otherwise.

From 1,057 individuals whom were fully screened, 307 were eligible and agreed to participate—and then randomized to the intervention or control groups and scheduled for a baseline interview (27). Additional interviews were administered two, six and 12 months after baseline using participants' preferred language (66 English, 138 Spanish, 48 Mandarin, and 55 Cantonese). For the present study, we used data from the baseline assessment (before any of the 307 eligible participants received the intervention). All assessments were structured in-person interviews by trained bilingual interviewers. The Institutional Review Boards of Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners HealthCare and New York University approved the study protocol.

Measures

Anxiety and Depression

GAD-7

The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-reported measure of probable cases of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (21). Respondents are asked how often, during the last 2 weeks, they were bothered by each symptom, with responses rated on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all and 3 = nearly every day). Total scores are calculated summing all items (range: 0–21), and higher scores represent worse symptoms. Previous studies in the general population have found a 1-factor model to be the preferable solution (31).

HSCL-25

The HSCL-25 is a 25-item screener of mood symptoms—ten anxiety symptoms and 15 depressive symptoms (22, 23). Respondents are asked how much they were bothered by each symptom in the last 4 weeks, with responses rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all and 4 = extremely). Total scores are computed averaging all items (range: 1–4), and higher scores represent worse symptoms. A 2-factor model comprising symptoms specific to anxiety and symptoms specific to depression has been found to be the preferable solution (32, 33).

Level of Functioning

Late-Life FDI

The Late-Life FDI is a 32-item self-reported measure assessing difficulty performing daily physical activities in older adults (24). Respondents are asked about difficulties performing an activity without help from someone else or the use of assisted devices, with responses rated on a 5-point scale (1 = cannot do and 5 = none). Total scores are calculated summing all items (range: 32–160), and scores approaching 32 indicate poor ability. A 3-factor solution has been found to explain most of the variance (24), with seven items representing upper extremity functioning, 14 items representing basic lower extremity functioning, and 11 items representing advanced lower extremity functioning.

WHODAS 2.0

The 12-item version of the WHODAS 2.0 is a brief generic instrument assessing level of functioning in six domains of life: Cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation (25, 26). Respondents are asked about functioning difficulties experienced in the last 30 days, with responses rated on a 5-point scale (1 = none and 5 = extreme or cannot do). Final scores are calculated summing all items (range: 12–60), with higher scores representing more difficulties.

Assessment Languages

Most measures included in the present study had been previously translated and psychometrically evaluated for use among Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese speakers. Although Mandarin and Cantonese translation-equivalents are orthographically identical—in fact, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences refers to Mandarin and Cantonese as two dialects of the same language (34)—they have many characteristics associated with distinct languages, and their spoken forms are mutually unintelligible (35, 36). Since all measures were collected via structured interviews by trained bilingual interviewers, in practice these measures were administered in four different languages, even though the written versions were the same in Mandarin and Cantonese.

Translations for Spanish speakers were available for the GAD-7 (37) and the WHODAS 2.0 (38, 39). Translations for Mandarin and Cantonese speakers were available for the GAD-7 (40), the HSCL-25 (41) and the WHODAS 2.0 (38, 39). Other translations (i.e., the HSCL-25 for Spanish speakers and the Late-Life FDI for Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese speakers) were performed using the English version, first by professional translators and then by bilingual PMSB staff. These translations were thoroughly reviewed and edited by supervising PMSB staff and back translated into English. A multicultural committee of clinicians and staff at partner agencies was convened afterwards to compare translations and back translations. When the back translations revealed ambiguities, a multinational panel of researchers knowledgeable about the measures were engaged to resolve them (27).

Statistical Analysis

We began by describing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, birthplace, marital status, suicidal behaviors, and chronic conditions) for the total sample and by language, using χ2 tests to assess significant group differences. We also presented descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and range) for our two measures of anxiety and depression (GAD-7 and HSCL-25) and our two measures of level of functioning (Late-Life FDI and WHODAS 2.0) in the total sample and by language, using two-tailed F-tests to assess significant group differences. We then tested measurement invariance using multiple group confirmatory factor analysis [CFA (42)]. In CFA, item response variation for each scale is modeled as a reflection of a latent factor representing a theoretical construct. In factor analysis terminology, we say the items load on a single factor.

Measurement Invariance Models

Based on a sequence of nested models, we tested three different levels of equivalence (43): Configural (equivalence of model form), metric (equivalence of factor loadings), and scalar (equivalence of item means). Since final scores of all analyzed measures are commonly used as a continuous scale, we treated the observed item responses as continuous variables. Additionally, we fitted separate models to each subscale of the HSCL-25 and the Late-Life FDI (i.e., anxiety and depression subscales for the HSCL-25, and upper extremity functioning, basic lower extremity functioning, and advanced lower extremity functioning for the Late-Life FDI) to make the one factor solution more plausible. Models were estimated using the robust maximum likelihood mean and variance adjusted estimator in Mplus 7.4 (44). To concretely illustrate each step, we focused on an example using the GAD-7 to compare anxiety symptoms between English, Spanish, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers. In this particular case, anxiety would be measured through seven continuously distributed items (e.g., feeling nervous, worrying too much) that load onto a latent factor that represents anxiety.

Configural invariance

Configural invariance assesses whether the unobserved factor (in our example the latent factor of anxiety) was related to item responses similarly across languages; that is, whether the factor structure is the same. Invariance at this level means that the basic organization of the latent construct is the same in all four languages, i.e., that the GAD-7 items load onto the same anxiety latent factor in all four languages. It is tested by evaluating overall model fit according to the criteria described below.

Metric invariance

Metric invariance assesses whether item factor loadings are similar across languages, suggesting that the latent variable is related to specific item translations to a similar degree. This model is nested within the configural model because it has the same structure but imposes equality constraints on the factor loadings. In our example, the loadings of the GAD-7 items (i.e., the loadings of the seven items on the anxiety construct) are set to be equivalent across language groups. Metric invariance holds if model fit is not worse compared to the configural model.

Scalar invariance

Scalar invariance assesses whether the item means are equivalent across languages after adjusting for possible group differences in the level of the latent variable (i.e., anxiety in our example). This model is nested within the metric model because it has the same structure but imposes equality constraints on the item intercepts, which reflect the adjusted item means. In our example, the item intercepts (means) of the seven items that load onto the anxiety construct are set to be equivalent across language groups. Scalar invariance holds if model fit is not worse compared to the metric model.

Partial invariance

If either metric or scalar invariance did not hold, we applied the concept of partial invariance (45) by identifying and setting free the factor loadings (partial metric invariance) and intercepts (partial scalar invariance) responsible for non-invariance. Metric non-invariance means that at least one loading is not equivalent across languages. In our example, non-invariance of a loading related to worrying too much would mean that this item is either more or less closely related to the latent construct of anxiety in one language than in the others. Scalar non-invariance indicates that at least one item intercept (mean) differs across languages. In our example, non-invariance of an item intercept for worrying too much would mean that speakers from one language are bothered either more or less by this symptom, but that is not related to increased or decreased levels of anxiety in that language group. Although it is recommended that a majority of the items be invariant (46), partial scalar invariance allows cross-language latent (not observed) mean differences to remain meaningful, provided that at least two of the items are invariant (47). In addition, the summed—or averaged—item responses of the invariant items can be used to compare groups (48).

When only partial scalar invariance was supported (such that only item responses from invariant items can be used to compare groups), we calculated an approximate measure of bias—and its 95% confidence interval—for each pair of languages. We defined Bias = ΔI+N – ΔI, where ΔI+N is the mean difference in invariant plus non-invariant items and ΔI is the mean difference in invariant items only. Consistent with previous literature, we considered |Bias| < 0.05 indicative of trivial bias, 0.05 ≤ |Bias| ≤ 0.10 indicative of moderate bias, and |Bias| > 0.10 indicative of substantial bias (49, 50).

Fit of Measurement Invariance Models

We assessed model fit using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values above 0.90 and 0.95 are considered adequate and good, respectively; RMSEA values below 0.08 and 0.05 are considered adequate and good, respectively (51, 52). Configural invariance held if configural model fit was either good or adequate. To compare fit between nested models (i.e., metric invariance model vs. configural invariance model and scalar invariance model vs. metric invariance model), we used the χ2 difference test (Δχ2), the difference in the CFI (ΔCFI) and the difference in the RMSEA (ΔRMSEA). Fit of the nested model was not worse compared to the less restricted model if either Δχ2 was not significant at the α = 0.05 level (53) or ΔCFI ≤ −0.01 (14) and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.01 (54). That is, fit of the metric invariance model was not worse compared to configural invariance model (i.e., metric invariance held) if either Δχ2 was not significant at the α = 0.05 level (p < 0.05) or ΔCFI ≤ −0.01 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.01. Analogously, fit of the scalar invariance model was not worse compared to the metric invariance model (i.e., scalar invariance held) if either Δχ2 was not significant at the α = 0.05 level (p < 0.05) or ΔCFI ≤ −0.01 and ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.01. The same model comparison fit criteria applied to partial invariance models.

Power to Detect Non-invariance

The number of observations included in measurement invariance tests is known to influence the power to detect non-invariance (13, 14). However, when it comes to invariance testing large samples are not necessarily the rule of thumb: Power to reject the hypothesis of invariance using Δχ2 increases as the sample size increases, which may lead to the erroneous conclusion that there is measurement non-invariance in large samples. Measurement invariance tests have thus shifted toward changes in alternative fit indices (such as ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA) because they are less sensitive to variations in sample size (14). To increase the likelihood that our sample size would not be associated with the level of measurement invariance achieved, we chose to use ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA (in addition to Δχ2) because these two model fit indices are less sensitive to sample size.

Results

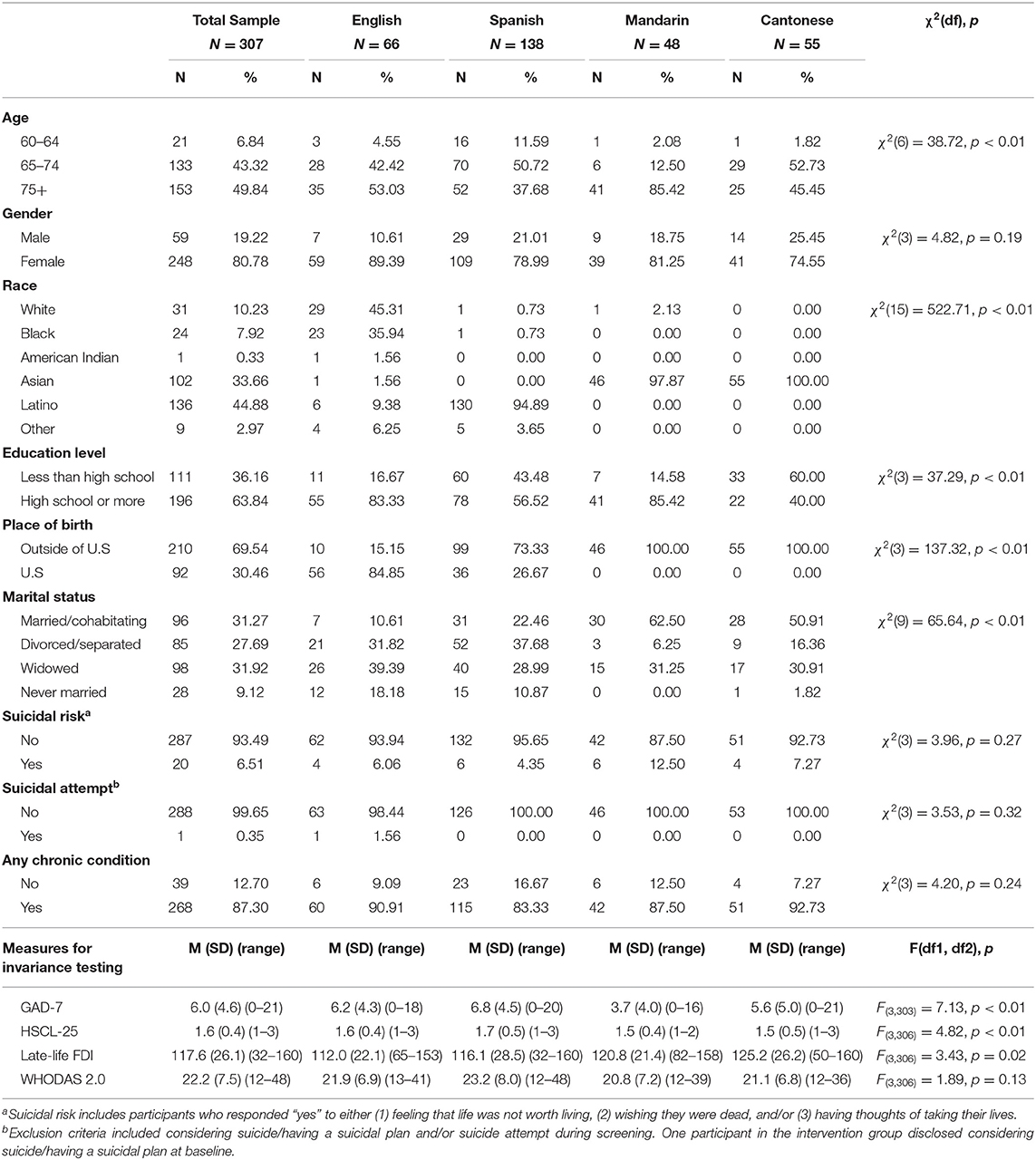

Table 1 presents the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics in the total sample and by language, including χ2 tests for significant group differences. Most participants were 75+ years old (49.8%), female (80.8%), Latino (44.9%), widowed (31.9%), had a high school degree or more (63.8%) and at least one chronic condition (87.3%). English speakers were more likely to self-identify as either White (45.3%) or Black (35.9%) and to be US born (84.9%). Spanish speakers were younger, less educated, and more likely to self-identify as Latino (94.9%) and to be foreign born (73.3%). Mandarin speakers were all foreign born and more likely to self-identify as Asian (97.9%) and to be married or cohabitating (62.5%). All Cantonese speakers self-identified as Asian and were foreign born.

In Table 1 we also present the distribution of the four measures used to test measurement invariance in the total sample and by language. Compared to English speakers, Mandarin speakers reported lower anxiety symptoms per the GAD-7 (p < 0.01) but Spanish and Cantonese speakers reported the same level of anxiety (p = 0.31 and p = 0.50, respectively). Regarding mood symptoms, Spanish speakers had higher HSCL-25 scores than English speakers (p = 0.03), while both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers presented the same level of mood symptoms than English speakers (p = 0.22 and p = 0.64, respectively). Level of functioning as measured by the Late-Life FDI was the same among Spanish speakers compared to English speakers (p = 0.29), but Mandarin and Cantonese speakers had both higher levels of functioning than English speakers (p = 0.03 and p < 0.01, respectively). There were no significant differences across language groups in level of functioning as measured by the WHODAS 2.0.

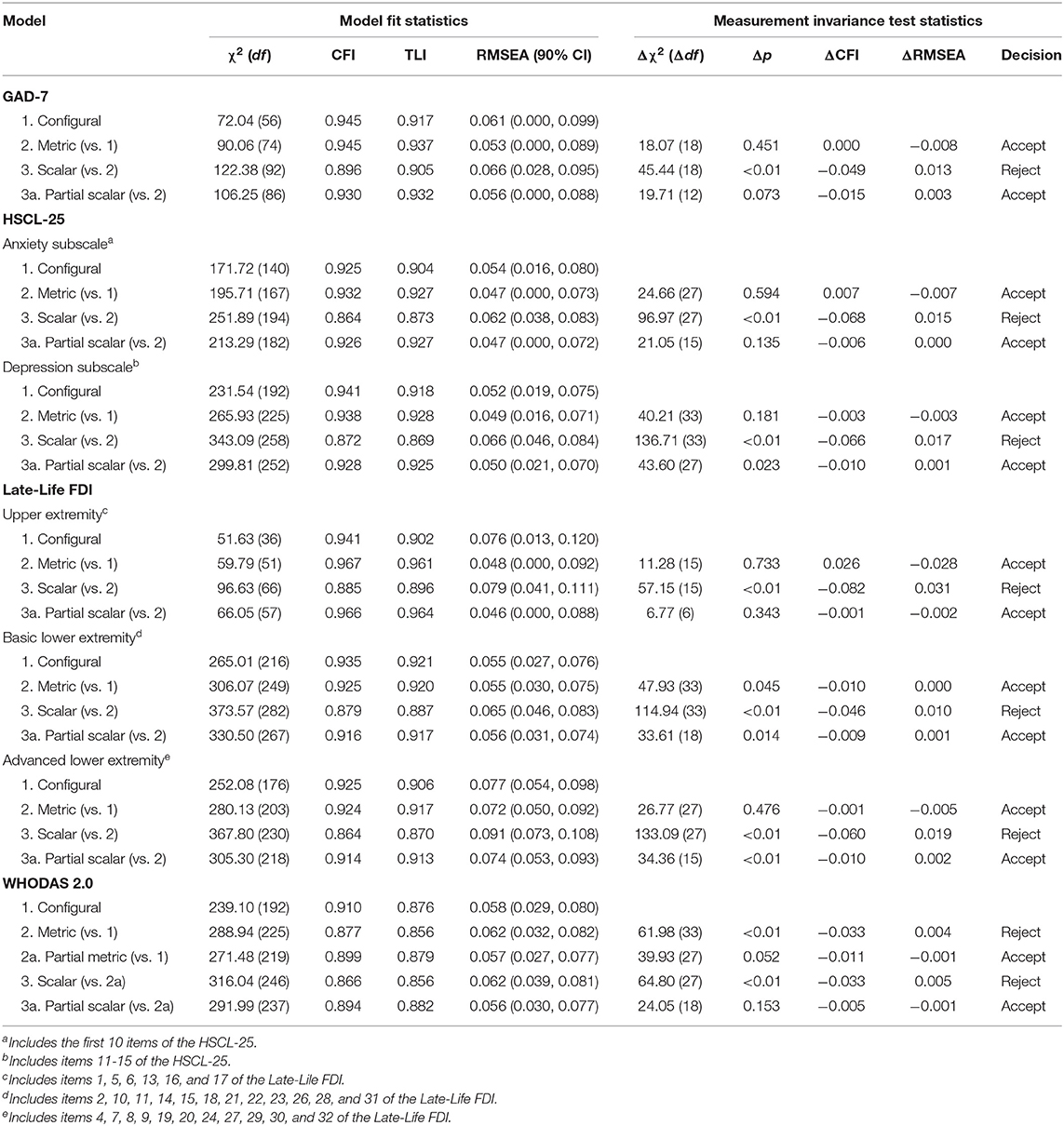

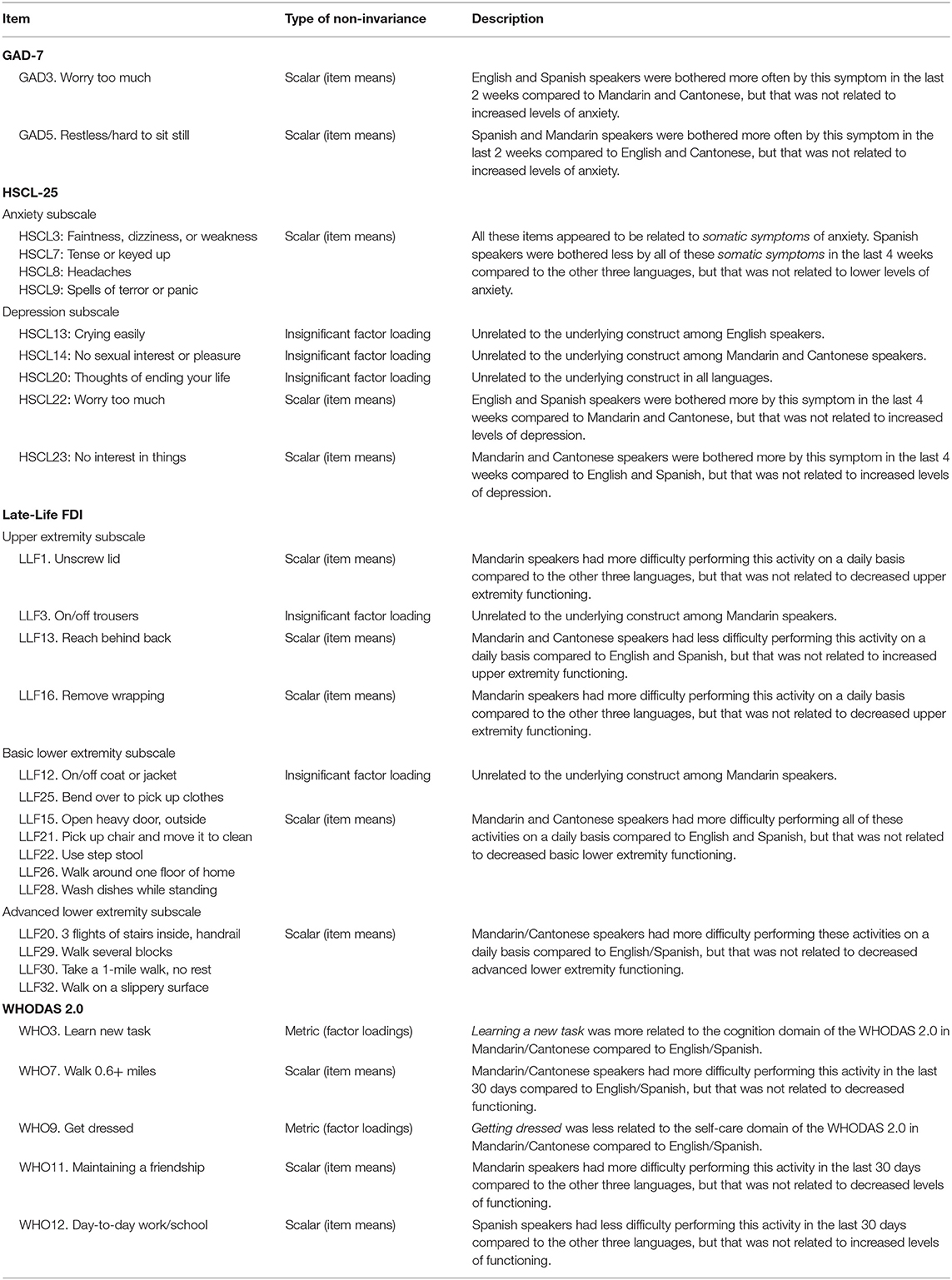

Measurement Invariance: GAD-7

Table 2 shows multiple group CFA results. A summary of the items that were found to have some degree of non-invariance is presented in Table 3. Regarding the GAD-7, configural model fit was adequate, indicating that the latent construct was conceptualized similarly across languages. There was evidence of similarity of factor loadings (metric invariance) but not of item intercepts. We investigated the source of scalar non-invariance by sequentially releasing (in a backward approach) item intercepts constraints and retesting the model. Partial scalar invariance was achieved after releasing the intercepts of two items. Adjusting for the latent variable, English and Spanish speakers reported being bothered more often by the symptom worry too much (i.e., higher item means) whereas Spanish and Mandarin speakers reported being bothered more often by the symptom restless/hard to sit still compared to respondents in other languages with the same level of anxiety.

Measurement Invariance: HSCL-25

Anxiety Subscale

In the anxiety subscale, configural model fit was adequate and fit of the metric model was not worse compared to the configural model, but fit of the scalar model was worse compared to the metric model. Partial scalar invariance was achieved after freeing the intercepts of four items related to somatic symptoms of anxiety (see Table 3). After adjusting for the latent variable, Spanish speakers reported being bothered less by these somatic symptoms (i.e., lower item means) compared to English, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers with the same level of anxiety.

Depression Subscale

Configural model fit was inadequate in the depression subscale (CFI = 0.817, TLI = 0.787, RMSEA = 0.068), and this model indicated that three items were unrelated to the underlying construct (see Table 3). Model fit improved after removing these items but was still inadequate (CFI = 0.877, TLI = 0.850, RMSEA = 0.070). In exploratory factor analysis (EFA) we found a very strong general factor (first to second eigenvalue ratio of 5.55–1.02) with a second factor clustering the four items related to somatic symptoms of depression: Low energy/slowed down, poor appetite, no interest in things and feeling everything is an effort. We modeled this clustering using a bifactor model, with one general depression factor and one somatic-symptoms factor uncorrelated with the general factor. This strategy isolates item response variation unaccounted for by the general depression factor. Configural model fit became adequate and there was evidence of metric invariance but not of scalar invariance. Partial scalar invariance was achieved by freeing the intercepts of two items: After adjusting for the latent variable, English and Spanish speakers reported being bothered more by the symptom worry too much whereas Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported being bothered more by the symptom no interest in things compared to respondents in other languages with the same level of depression.

Measurement Invariance: Late-Life FDI

Upper Extremity Functioning Factor

Configural model fit for this factor was inadequate (CFI = 0.900, TLI = 0.849, RMSEA = 0.089), and this model indicated that one item was unrelated to the underlying construct in Mandarin. After removing this item, fit of the configural model improved and became adequate. There was also evidence of metric invariance, and of partial scalar invariance after freeing the intercepts of three items. Adjusting for the latent variable, Mandarin speakers reported more difficulty performing the activities unscrew lid and remove wrapping whereas Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported less difficulty performing the activity reaching behind back compared to respondents in other languages with the same level of functioning.

Basic Lower Extremity Functioning Factor

Configural model fit for this factor was adequate per the CFI and RMSEA but not per the TLI (CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.056), and this model suggested that two items were unrelated to the underlying construct in Mandarin. Configural model fit was adequate after removing these two items, and there was evidence of equality of factor loadings but not of equality of item intercepts. Partial scalar invariance was achieved after freeing the intercepts of the five items. Adjusting for the latent variable, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported more difficulty performing the activities listed on these items (see Table 3) compared to English and Spanish speakers with the same level of functioning.

Advanced Lower Extremity Functioning Factor

Configural model fit for this factors was inadequate (CFI = 0.917, TLI = 0.896, RMSEA = 0.081). In EFA we found a very strong general factor (first to second eigenvalue ratio of 5.95–0.83) but two items related to walking clustered in a separate factor. We modeled this clustering using a bifactor model with one general advanced lower extremity factor and one walking-symptoms factor uncorrelated with the general factor. Configural model fit became adequate, fit of the metric model was not worse compared to the configural model, and partial scalar invariance held after freeing the intercepts of four items. Adjusting for the latent variable, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported more difficulty performing the activities listed on these items (see Table 3) compared to English and Spanish speakers with the same level of functioning.

Measurement Invariance: WHODAS 2.0

Configural model fit for the WHODAS 2.0 was inadequate (CFI = 0.739, TLI = 0.682, RMSEA = 0.092). In EFA, we found a very strong general factor (first to second to third eigenvalue ratio of 4.50 to 1.31 to 1.07), but four items clustered in two separate factors corresponding to two of the six disability domains: Mobility (stand for 30+ min and walk 0.6+ miles) and self-care (wash whole body and get dressed). We modeled this clustering using a bifactor model, with one general disability factor and six domain specific factors uncorrelated with the general factor. Configural model fit improved and although the TLI still indicated inadequate fit, we continued invariance testing using this bifactor model. Only partial metric and partial scalar invariance were achieved. Partial metric invariance held after allowing two factor loadings to be freely estimated, while partial scalar invariance held after allowing three item intercepts to be freely estimated. Compared to English and Spanish speakers, learn new task was more related to the cognition domain and get dressed was less related to the self-care domain among Mandarin and Cantonese speakers. In addition, after adjusting for the latent variable, Mandarin speakers reported more difficulty with walk 0.6+ miles and maintaining a friendship while Spanish speakers reported less difficulty with day-to-day school/work compared to respondents in other languages with the same level of functioning.

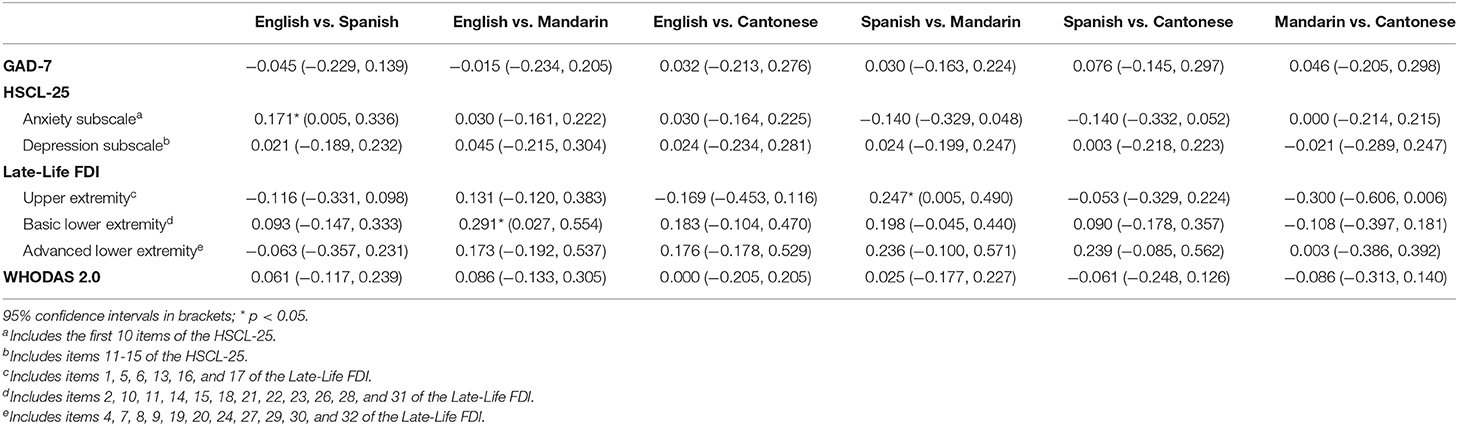

Bias From Removing Non-Invariant Items in Cross-Language Comparisons

Since only partial scalar invariance was supported for all measures, we calculated the bias from removing non-invariant items in cross-language comparisons (Table 4). Bias was either trivial or moderate, and there was significant substantial bias in only three out of 42 pairwise comparisons: Removing non-invariant items would underestimate (Bias > 0) mean differences between English and Spanish speakers in the anxiety subscale of the HSCL-25 (effect size = 0.27), mean differences between Spanish and Mandarin speakers in upper extremity functioning (effect size = 0.39), and mean differences between English and Mandarin speakers in basic lower extremity functioning (effect size = 0.30).

Discussion

Overview

Using a racially/ethnically diverse sample of US minority older adults, we applied invariance tests to common measures of anxiety, depression and level of functioning comparing four languages: English, Spanish, Mandarin, and Cantonese. We found that the underlying theoretical constructs were conceptualized comparably in all four languages, and that item response data had a similar psychometric structure across groups. However, item-means were only partially equivalent after adjusting for possible group differences in the level of the latent variable (i.e., speakers from certain language groups were bothered more or less often by some symptoms, but that was not related to increased or decreased levels of the theoretical construct). Since only item responses from invariant items can be used to compare language groups, we calculated the bias from omitting items that appeared to function differently, and found that omitting these items did not introduce substantial bias in cross-language comparisons. Nevertheless, we identified a non-negligible number of items that may require further study before their use to compare symptoms of anxiety, depression and level of functioning among linguistically diverse older adult populations: Two out of seven items in the GAD-7; nine out of 25 items in the HSCL-25; 15 out of 32 items in the Late-Life FDI; and five out of 12 items in the WHODAS 2.0.

Anxiety and Depression

English and Spanish speakers reported more worry symptoms in both the GAD-7 and the depression subscale of the HSCL-25 for reasons unrelated to anxiety and depression, which is consistent with prior literature comparing expression of psychological distress across cultures. In a diverse cohort of cancer patients 21–84 years old, Teresi et al. (55) found that Latinos, Blacks and Spanish speakers were posited to express greater worry in the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Anxiety item bank (55). Similarly, Varela et al. (56) found that US Hispanic youth reported more worry symptoms than US European American youth in the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (56). Since our study sample was made of older adults 60+ years old, our findings suggest then that Latinos (most of whom were assessed in Spanish) are more likely to express symptoms of worry for reasons unrelated to anxiety throughout their lifespan, and that measuring anxiety via worry symptoms among Latinos and Spanish speakers might not be warranted.

We also found that Spanish speakers (94.9% of whom self-identified as Latino) and Mandarin speakers (97.9% of whom self-identified as Asian) reported feeling more restless in the GAD-7 for reasons unrelated to anxiety. In the same cohort of cancer patients 21–84 years old, Teresi et al. (55) found that Latinos and Asians showed a higher probability of reporting feeling anxious in the PROMIS Anxiety item bank (55). Our results are thus consistent with this previous finding since restlessness is one of the most commonly reported symptoms of feeling anxious, highlighting the need to carefully examine whether feelings of restlessness are a true indicator of anxiety symptoms among Spanish and Mandarin speakers.

We encountered that Spanish speakers reported being bothered less on several somatic symptoms items of the HSCL-25 (faintness, dizziness or weakness; tense or keyed up; headaches; and spells of terror or panic) for reasons unrelated to anxiety. There is a common notion that Latinos report more somatic symptoms of psychological distress than English Speakers (57, 58), but recent evidence also suggests that Latino older adults might not somaticize their psychological distress. Letamendi et al. (59), for example, found that while many older Mexican-Americans experience clinically significant criteria for anxiety and depression, endorsement of physical symptoms of psychological distress was very low in the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 Spanish Version, a widely used tool to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and somatization (59). Similarly, Teresi and Golden (60) found that some of the somatic symptoms of the SHORT-Comprehensive and Assessment and Referral Evaluation Depression scale were relatively less severe indicators of depression for Latinos than for English Speakers (60). It is possible then that Latinos report either more or less somatic symptoms for reasons unrelated to psychological distress at different timepoints througout their lives. Regardless, it seems to be the case that Latinos tend to express somatic symtpoms of psychopathology differently compared to other cultures, and these differences in somatization could be primarily cultural rather than linguistic.

We also found that Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, most of whom self-identified as Asian, reported being bothered more by the symptom no interest in things in the HSCL-25 for reasons unrelated to depression. This finding is consistent with previous work by Zhao et al. (61) whom found that loss of interest items in five depression measures had low discriminating power to distinguish Chinese patients with varied levels of depression, and that these items were only associated with moderate but not severe depressive symtpoms (61). Prior research has argued that compared to Western cultures, Chinese older adults are more likely to place greater emphasis on meeting sociocultural demands—possibly because they perceive future time as more limited—and to adjust personal goals to make them consistent with their cultural values (62). It is possible then that Mandarin and Cantonese speakers interpreted no interest in things as a symtpom related to their own self, so they reported being bothered more by this symptom to reflect a shift toward prioritizing cultural values over personal goals, and not for reasons related to depressive symptoms.

Finally, we found that three items were unrelated to the underlying construct in the depression subscale of the HSCL-25: Crying easily in English, no sexual interest or pleasure in Mandarin and Cantonese, and thoughts of ending your life in all languages. Thus, we dropped these items and tested invariance using 12-items instead of 15. Regarding crying easily and thoughts of ending your life, we believe this result might be associated with specific characteristics of our sample. Almost 90% of the English speakers were female, who have been consistently found to report crying more frequently for reasons unrelated to psychological distress (63). Crying has also been found to be weakly associated with depression among US older adults (64). As noted in the section Methods, participants disclosing serious suicide plans or attempts were ineligible to participate in the study, and this was most likely the reason why thoughts of ending your life was unrelated to the underlying construct in all languages. In regard to no sexual interest or pleasure, our results support the claim that Asian populations are more reluctant to discuss sexual topics (65) and that they also suppress the expression of emotional/affective symptoms (66).

Level of Functioning

Mandarin and Cantonese speakers reported more difficulties performing physical activities in both the Late-Life FDI and the WHODAS 2.0 for reasons unrelated to their levels of functioning. We observed this result for basic/moderate tasks like unscrewing a lid, removing wrapping or washing dishes and for more strenuous activities like taking a one-mile walk without rest or walk on a slippery surface. A similar result was previously found in the physical function subscale of the EORTC QLC-30, a widely-used health-related quality of life instrument (67). In that study, participants from six East Asian countries (South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, China, Myanmar, and Hong Kong), most of whom responded to the EORTC QLC-30 in Chinese, tended to score relatively high on two items regarding their ability to take a short walk and needing to stay in bed compared to respondents from the UK (all of whom responded in English). Per the authors, differential item functioning was primarily cultural rather than linguistic, which they concluded from their observation that Singaporeans, whom were bilingual and could choose either the English or Chinese translation, had response patterns from the English version that appeared closer to those of the East Asian countries than to English speaking countries.

It has been argued that there are more negative views on aging in China compared to the US in several life domains, including physical and mental fitness (68, 69). These cross-country differences do not appear to be solely explained by biological changes related to aging [e.g., decreased ability to perform daily tasks as people get older (69)], so higher population aging rates in China compared to the US cannot completely account for these differences. Variations in other factors like individualism/collectivism seem to also explain these East-West differences (69). Individualism has been found to be associated with more positive views on aging (68), and it has also been found to be higher in the US compared to China (70). Mandarin speakers in our sample were older compared to other languages (85.42% were 75+ years old), but Cantonese speakers had age profiles similar to English and Spanish speakers, supporting the idea that age group differences might not completely explain the observed differences in reports of difficulties performing physical activities. In contrast, all Mandarin and Cantonese speakers were foreign born, making them more likely to have cultural values associated with higher collectivism and lower individualism, which can in turn make them more likely to have negative views on aging in relation to their functioning.

We also found that the item learn new task was more related to the WHODAS 2.0 cognition domain among Mandarin and Cantonese speakers. The possibility of some degree of culturally determined differential functioning in this item has been previously found among rural Chinese older populations in the preceding version of the WHODAS 2.0 (the WHODAS II; 26]. Spanish speakers in the present study also seemed to report less difficulties with day-to-day school/work for reasons unrelated to their level of functioning. In contrast, the study by Sousa et al. (26) using the WHODAS II found no cultural differences between Spanish and Chinese speaking countries for the item everyday activities (which was replaced by day-to-day school/work in the WHODAS 2.0), suggesting that more research within Latinos and Spanish speakers in relation to this item might be needed (26).

Conclusion and Limitations

Screening measures of anxiety, depression and level of functioning were found to be conceptualized similarly in a randomized trial sample of US minority older adults who were assessed in English, Spanish, Mandarin or Cantonese. However, at the item-level symptom burden, we identified symptoms with some degree of differential item functioning. Although our results were consistent with prior literature comparing expression of psychological symptoms across language and racial/ethnic groups (suggesting that the source of differential item functioning might be primarily cultural rather than linguistic), we singled out a non-negligible number of non-invariant items that may require careful examination before considering their use to compare symptoms of psychopathology among linguistically diverse older adult populations.

Our study has several limitations. Like prior studies using racial/ethnic diverse samples from randomized trials, we were constrained by small sample size in each language. A 2016 analytical review found that sample size and number of groups seem to be unrelated to the level of invariance achieved (11); however, that does not mean that our study could have not benefited from both an overall larger sample and a larger sample in each language group. Further, respondents in our sample all had mild to severe depression and anxiety symptoms and some degree of mobility limitations, so results may not generalize to older adults who have no psychological diagnoses and are functionally intact. We tested invariance comparing linguistic groups which, though most likely was equivalent to racial/ethnic group for Spanish, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, did not apply to English speakers whom included both White and Black older adults. Finally, although previous studies have documented differences in the expression of psychopathology between males and females, we did not examine whether there were differences in our results by gender since testing measurement invariance across both gender and language groups was not the aim of our study. In addition, we believe that we would have not had adequate power to test for differences in our results by gender given the low number of males in each language group, particularly among English (N = 7) and Mandarin speakers (N = 9).

Despite these limitations, our study expands invariance testing in self-reported health outcome measures within psychological research. Health disparities are often measured using data from self-reported measures (17). Thus, our findings emphasize the importance of performing invariance tests before claiming that racial/ethnic differences in health outcomes exist or do not exist. In particular, the results from the present study indicate that to objectively compare levels of psychopathology between linguistically diverse older adult populations, several symptoms with some degree of differential item functioning might need to be excluded. Our findings also highlight the need for additional cross-validation studies using larger samples of different racial/ethnic and language groups, which would allow more in-depth analyses of the type of differential item functioning and the potential risk of response bias among ethnically and linguistically diverse patients.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Institutional Review Boards of Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners HealthCare and New York University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MA, MC-G, and KA contributed to the conception and design of the study. MC-G organized the database and performed the statistical analysis. MC-G and MA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IH wrote sections of the manuscript. PS advised on statistical methods. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant No. R01AG046149. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders (NIA, NIMH) had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the partnering community organizations, research staff, and study participants, without whom this paper would not have been possible. Furthermore, we gratefully thank Sheri Markle, Lulu Wang, Larimar Fuentes, and Yuying Guo for their assistance with study data, and Isabel O'Malley for her contributions to the revisions and preparation of the manuscript.

References

1. He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P. An aging world: 2015. U.S. Census Bureau, International Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office (2016). p. 408.

2. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office (2014).

3. Okereke OI. Racial and ethnic diversity in studies of late-life mental health. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. (2014) 22:637. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.004

4. Guo M, Li S, Liu J, Sun F. Family relations, social connections, and mental health among Latino and Asian older adults. Res. Aging. (2015) 37:123–47. doi: 10.1177/0164027514523298

5. Lenze EJ, Schulz R, Martire LM, Zdaniuk B, Glass T, Kop WJ, et al. The course of functional decline in older people with persistently elevated depressive symptoms: longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. (2005) 53:569–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53202.x

6. Liang J, Xu X, Quiñones AR, Bennett JM, Ye W. Multiple trajectories of depressive symptoms in middle and late life: racial/ethnic variations. Psychol. Aging. (2011) 26:761. doi: 10.1037/a0023945

7. Vyas CM, Donneyong M, Mischoulon D, Chang G, Gibson H, Cook NR, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with late-life depression severity, symptom burden, and care. JAMA Netw. Open. (2020) 3:1–15. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1606

8. Melvin J, Hummer R, Elo I, Mehta N. Age patterns of racial/ethnic/nativity differences in disability and physical functioning in the United States. Demogr. Res. (2014) 31:497. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.17

9. Bieda A, Hirschfeld G, Schönfeld P, Brailovskaia J, Zhang XC, Margraf J. Universal happiness? Cross-cultural measurement invariance of scales assessing positive mental health. Psychol. Assess. (2017) 29:408. doi: 10.1037/pas0000353

10. Borsboom D. When does measurement invariance matter? Med. Care. (2006) 44:S176–81. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245143.08679.cc

11. Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. (2016) 41:71–90. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

12. Evangelidou S, NeMoyer A, Cruz-Gonzalez M, O'Malley I, Alegría M. Racial/ethnic differences in general physical symptoms and medically unexplained physical symptoms: investigating the role of education. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. (2020) 26:557–69. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000319

13. Meade AW, Johnson EC, Braddy PW. Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. J. Appl. Psychol. (2008) 93:568. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568

14. Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equation Model. (2002) 9:233–55. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

15. Cieciuch J, Davidov E, Algesheimer R, Schmidt P. Testing for approximate measurement invariance of human values in the European Social Survey. Soc. Methods Res. (2018) 47:665–86. doi: 10.1177/0049124117701478

16. Santiago CD, Miranda J. Progress in improving mental health services for racial-ethnic minority groups: a ten-year perspective. Psychiatr. Serv. (2014) 65:180–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200517

17. Beauchamp MK, Schmidt CT, Pedersen MM, Bean JF, Jette AM. Psychometric properties of the late-life function and disability instrument: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. (2014) 14:2–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-12

18. Wind TR, van der Aa N, de la Rie S, Knipscheer J. The assessment of psychopathology among traumatized refugees: measurement invariance of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 across five linguistic groups. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8(Supp. 2):1321357. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1321357

19. Ramírez M, Ford ME, Stewart ALA, Teresi J. Measurement issues in health disparities research. Health Serv. Res. (2005) 40(5 Pt 2):1640–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00450.x

20. Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, Chavira DA, Lau AS. Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: a systematic review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Serv. Res. (2018) 45:195–211. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0815-0

21. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

22. Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, Morris RJ, Newman H, Rosenfeld H. Psychiatric illness in family practice. J. Clin. Psychiatry. (1980) 41:6–10.

23. Winokur A, Winokur DF, Rickels K, Cox DS. Symptoms of emotional distress in a family planning service: stability over a four-week period. Br. J. Psychiatry. (1984) 144:395–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.4.395

24. Haley SM, Jette AM, Coster WJ, Kooyoomjian JT, Levenson S, Heeren T, et al. Late life function and disability instrument: II. Development and evaluation of the function component. J. Gerontol. Ser. A. (2002) 57:M217–22. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.M217

25. Federici S, Bracalenti M, Meloni F, Luciano JV. World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0: an international systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. (2017) 39:2347–80. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1223177

26. Sousa RM, Dewey ME, Acosta D, Jotheeswaran AT, Castro-Costa E, Ferri CP, et al. Measuring disability across cultures—the psychometric properties of the WHODAS II in older people from seven low-and middle-income countries. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. (2010) 19:1–7. doi: 10.1002/mpr.299

27. Alegría M, Frontera W, Cruz-Gonzalez M, Markle SL, Trinh-Shevrin C, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of a disability preventive intervention for minority and immigrant elders: the positive minds-strong bodies randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. (2019) 27:1299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.08.008

28. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. (2002) 32:509–15. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

29. de Craen AJ, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. (2003) 18:63–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.773

30. Freire AN, Guerra RO, Alvarado B, Guralnik JM, Zunzunegui MV. Validity and reliability of the short physical performance battery in two diverse older adult populations in Quebec and Brazil. J. Aging Health. (2012) 24:863–78. doi: 10.1177/0898264312438551

31. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

32. Al-Turkait FA, Ohaeri JU, El-Abbasi AH, Naguy A. Relationship between symptoms of anxiety and depression in a sample of Arab college students using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25. Psychopathology. (2011) 44:230–41. doi: 10.1159/000322797

33. Glaesmer H, Braehler E, Grande G, Hinz A, Petermann F, Romppel M. The German version of the Hopkins symptoms Checklist-25 (HSCL-25)—factorial structure, psychometric properties, and population-based norms. Compr. Psychiatry. (2014) 55:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.020

35. Tang C, van Heuven VJ. Mutual intelligibility of Chinese dialects experimentally tested. Lingua. (2009) 119:709–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2008.10.001

36. Cai ZG, Pickering MJ, Yan H, Branigan HP. Lexical and syntactic representations in closely related languages: Evidence from Cantonese-Mandarin bilinguals. J. Memory Lang. (2011) 65:431–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2011.05.003

37. Garcia-Campayo J, Zamorano E, Ruiz M, Pardo A, Perez-Paramo M, Lopez-Gomez V, et al. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorde-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. (2010) 8:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-8

38. World Health Organization. Chapter 2: WHODAS 2.0 development. In: Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disabiility Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Üstün T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J, editors. Geneva: WHO Press (2010). p. 11–7.

39. World Health Organization. Chapter 3: Psychometric properties of WHODAS 2.0. In: Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disabiility Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Üstün T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J, editors. Geneva: WHO Press (2010). p. 19–25.

40. He X, Li C, Qian J, Cui H, Wu W. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatient. Shangai Arch. Psychiatry. (2010) 22:200–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2010.04.002

42. Millsap RE, Yun-Tein J. Assessing factorial invariance in ordered-categorical measures. Multivariate Behav. Res. (2004) 39:479–515. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_4

43. Van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur. J. Dev. Psychology. (2012) 9:486–92. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.686740

45. Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthén B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull. (1989) 105:456–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

46. Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods. (2000) 3:4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002

47. Steenkamp JB, Baumgartner H. Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. J. Consum. Res. (1998) 25:78–90. doi: 10.1086/209528

48. Alvarez K, Wang Y, Alegria M, Ault-Brutus A, Ramanayake N, Yeh YH, et al. Psychometrics of shared decision making and communication as patient centered measures for two language groups. Psychol. Assess. (2016) 28:1074–86. doi: 10.1037/pas0000344

49. Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods. (2004) 9:466–91. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466

50. Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods. (2012) 17:354–73. doi: 10.1037/a0029315

51. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Model. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

52. McDonald RP, Marsh HW. Choosing a multivariate model: noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychol. Bull. (1990) 107:247–55. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.247

53. Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull. (1993) 114:552–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552

54. Rutkowski L, Svetina D. Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educ. Psychol. Meas. (2014) 74:31–57. doi: 10.1177/0013164413498257

55. Teresi JA, Ocepek-Welikson K, Kleinman M, Ramirez M, Kim G. Measurement equivalence of the patient reported outcomes measurement information system®(PROMIS®) anxiety short forms in ethnically diverse groups. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. (2016) 58:183–219.

56. Varela RE, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Biggs BK, Luis TM. Anxiety symptoms and fears in hispanic and European American children: cross-cultural measurement equivalence. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. (2008) 30:132–45. doi: 10.1007/s10862-007-9056-y

57. Escobar JI, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Karno M. Somatic symptom index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct: prevalence and epidemiological correlates in two large community samples. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. (1989) 177:140–46. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198903000-00003

58. Diefenbach GJ, Robison JT, Tolin DF, Blank K. Late-life anxiety disorders among Puerto Rican primary care patients: impact on well-being, functioning, and service utilization. J. Anxiety Disord. (2004) 18:841–58. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.10.005

59. Letamendi AM, Ayers CR, Ruberg JL, Singley DB, Wilson J, Chavira D, et al. Illness conceptualizations among older rural Mexican-Americans with anxiety and depression. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. (2013) 28:421–33. doi: 10.1007/s10823-013-9211-8

60. Teresi JA, Golden RR. Latent structure methods for estimating item bias, item validity and prevalence using cognitive and other geriatric screening measures. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. (1994) 8:S291–8.

61. Zhao Y, Chan W, Lo BC. Comparing five depression measures in depressed Chinese patients using item response theory: an examination of item properties, measurement precision and score comparability. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. (2017) 15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0631-y

63. Romans SE, Clarkson RF. Crying as a gendered indicator of depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. (2008) 196:237–43. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318166350f

64. Hastrup JL, Baker JG, Kraemer DL, Bornstein RF. Crying and depression among older adults. Gerontologist. (1986) 26:91–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.1.91

65. So HW, Cheung FM. Review of Chinese sex attitudes & applicability of sex therapy for Chinese couples with sexual dysfunction. J. Sex Res. (2005) 42:93–101. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552262

66. Zhu L. Depression symptom patterns and social correlates among Chinese Americans. Brain Sci. (2018) 8:16. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8010016

67. Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bottomley A, De Graeff A, Groenvold M, et al. The use of differential item functioning analyses to identify cultural differences in responses to the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual. Life Res. (2007) 16:115–29. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9120-1

68. North MS, Fiske ST. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: a cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. (2015) 141:993–1021. doi: 10.1037/a0039469

69. Voss P, Kornadt AE, Hess TM, Fung HH, Rothermund K. A world of difference? Domain-specific views on aging in China, the US, and Germany. Psychol. Aging. (2018) 33:595–606. doi: 10.1037/pag0000237

Keywords: minority older adults, linguistic minorities, measurement invariance, anxiety, depression, level of functioning

Citation: Cruz-Gonzalez M, Shrout PE, Alvarez K, Hostetter I and Alegría M (2021) Measurement Invariance of Screening Measures of Anxiety, Depression, and Level of Functioning in a US Sample of Minority Older Adults Assessed in Four Languages. Front. Psychiatry 12:579173. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.579173

Received: 01 July 2020; Accepted: 25 January 2021;

Published: 15 February 2021.

Edited by:

Anastasia Theodoridou, Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Milena Gandy, Macquarie University, AustraliaChristos Theleritis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Copyright © 2021 Cruz-Gonzalez, Shrout, Alvarez, Hostetter and Alegría. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margarita Alegría, bWFsZWdyaWFAbWdoLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Mario Cruz-Gonzalez

Mario Cruz-Gonzalez Patrick E. Shrout3

Patrick E. Shrout3 Kiara Alvarez

Kiara Alvarez Isaure Hostetter

Isaure Hostetter Margarita Alegría

Margarita Alegría