Abstract

An important component of nonverbal communication is gesture performance, which is strongly impaired in 2/3 of patients with schizophrenia. Gesture deficits in schizophrenia are linked to poor social functioning and reduced quality of life. Therefore, interventions that can help alleviate these deficits in schizophrenia are crucial. Here, we describe an ongoing randomized, double-blind 3-arm, sham-controlled trial that combines two interventions to reduce gesture deficits in schizophrenia patients. The combined interventions are continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) and social cognitive remediation therapy (SCRT). We will randomize 72 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in three different groups of 24 patients. The first group will receive real cTBS and real SCRT, the second group will receive sham cTBS and real SCRT, and finally the third group will receive sham SCRT. Here, the sham treatments are, as per definition, inactive interventions that mimic as closely as possible the real treatments (similar to placebo). In addition, 24 age- and gender-matched controls with no interventions will be added for comparison. Measures of nonverbal communication, social cognition, and multimodal brain imaging will be applied at baseline and after intervention. The main research aim of this project will be to test whether the combination of cTBS and SCRT improves gesture performance and social functioning in schizophrenia patients more than standalone cTBS, SCRT or sham psychotherapy. We hypothesize that the patient group receiving the combined interventions will be superior in improving gesture performance.

Clinical Trial Registration:

[www.ClinicalTrials.gov], identifier [NCT04106427].

Introduction

Schizophrenia is characterized by negative (e.g., affective flattening, avolition, low social drive) and positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, agitation, delusions) (1–3), as well as, disorganized thinking (4), motor abnormalities (5–7), and impaired cognitive function (8, 9). Social cognition, which refers to psychological processes that allow for the decoding of the behaviors and intentions of others (10–12), is also impaired in schizophrenia (13). In fact, impaired nonverbal communication is a core characteristic of social cognition deficits in patients with schizophrenia. Impaired nonverbal communication in schizophrenia includes limited nonverbal social perception (14–16) and poor gesture performance (17–19). Most importantly, gesture deficits are directly associated with patients’ poor functional outcome (20). This association between gesturing and functioning is the main reason why we believe that establishing treatments, which alleviate gesture deficits are essential to improve patients’ overall functioning and quality of life (21). Such treatments can potentially facilitate societal participation. With the current trial, we want to determine whether combined brain stimulation and group therapy improve schizophrenia patients’ gesture skills and social functioning.

Gesture Deficits in Schizophrenia

Gestures are an integral feature of communication: they support language production and transmit information on their own (22). Gesture deficits are prevalent in approximately two-thirds of patients with schizophrenia (17, 18, 23). Accumulating evidence suggests that various domains of gesturing are impaired in schizophrenia, including use of gestures (17, 18, 24, 25) and gesture perception (26). In fact, individuals with schizophrenia often use incoherent and fewer gestures (17, 27, 28) and tend to interpret gestures negatively (29, 30).

Gesture deficits in patients are associated with core schizophrenia symptoms, e.g., negative symptoms (24, 27), frontal lobe dysfunction (17, 18), formal thought disorder (23, 31) and working memory impairments (15, 24). At a neural level, gesture processing involves the praxis network, which combines motor- and speech-related brain areas (32, 33). Neuroimaging demonstrated structural and functional alterations in the praxis network in schizophrenia patients with gesture deficits (34–38). Specifically, two areas of the praxis network are linked to gesture deficits in schizophrenia: the inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (39, 40). The IPL has been related to motor functioning, as well as cognitive and visuospatial processing (41–43). The IFG has been associated with motor functioning and language production (44).

Interventions Improving Gesture and Social Skills

Brain Stimulation

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has the potential to (re-)train distinct neural pathways and therefore rehabilitate specific functions in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders (45). Recent studies demonstrated rTMS efficacy across different domains in patients with schizophrenia. For example, rTMS over the supplementary motor area (SMA) ameliorated motor abnormalities (46, 47) and rTMS over the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) improved gesture performance (48). Different rTMS protocols can have different effects on brain function, depending on their frequency and type of stimulation (49).

Theta burst stimulation (TBS) is an innovative rTMS protocol, which requires less time than standard rTMS. There are two types of TBS: intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS), which mainly has facilitatory effects and continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS), which has inhibitory effects. A pilot study demonstrated that inhibitory cTBS over the right inferior parietal lobe (rIPL) improved gesture performance by comparing 3 rTMS protocols (including sham stimulation) in 20 patients (48). Due to interhemispheric rivalry, cTBS on the right IPL may induce a facilitatory effect on left IPL through transcallosal disinhibition (50). As such, inhibitory cTBS over the rIPL is a promising method to reduce gesture deficits in schizophrenia. We decided to use the same cTBS protocol for repetitive administration in a larger sample.

Social Cognitive Remediation Therapy

Social cognition is a main driver of recovery and functional outcomes (10, 51–53) and mediates the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning in schizophrenia (53). The MATRICS initiative (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) identified the most important cognitive domains in schizophrenia (10, 54). These consist of six neurocognitive domains: speed of processing (1), attention/vigilance (2), working memory (3), verbal learning (4), visual learning (5) and reasoning/problem solving (6) and five social-cognitive domains: emotion processing (1), social perception (2), theory of mind (3), social schemata/knowledge (4) and social attribution styles (5). Therapies focusing on both neurocognition and social cognition are suggested to be a promising approach to help patients with schizophrenia (55–57).

One of the few integrative cognitive remeditation therapies (CRT) covering all MATRICS domains is the Integrated Neurocognitive Therapy (INT) (58, 59). This CRT approach takes place in a group setting, including social interactive tasks and computerized neurocognitive exercises (using the Cogpack program). INT showed good feasibility with reduction of positive symptoms, negative symptoms and relapses, as well as, improvements in social cognition, neurocognition, and overall functioning in patients with schizophrenia (56, 60–62). The INT includes four modules, each addressing various cognitive domains: processing speed, attention, and perception of emotions (1); verbal and visual learning, memory, social perception, and theory of mind (2); reasoning, problem solving, and social schema (3); working memory and the ability to attribute appropriate meanings (4). INT focuses on the improvement of both social cognition and neurocognition, with more focus on the latter.

Social cognitive remediation therapy (SCRT) is an approach focusing mainly on social cognition in patients with schizophrenia (58, 63). As of today, two types of SCRTs are being developed: targeted and broad-based SCRTs. Targeted SCRTs address only the remediation of one specific social cognitive deficit (e.g., facial affect recognition) (64), whereas broad-based SCRTs address multiple social cognitive domains (65). Integrative broad-based SCRTs combine the improvement of social cognitive domains with other therapy techniques, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (66), cognitive remediation (67, 68) or social skills training (69–71). It is advisable to use an integrative approach involving both neurocognitive and social-cognitive domains, as these lead to greater generalization effects on functional outcome (53, 72, 73). In light of previous studies, we consider integrative broad-based SCRTs a promising treatment to reduce social cognitive impairments and enhance functioning in schizophrenia. Therefore, we decided to use this type of treatment approach for the current study.

Methods

Aims and Hypotheses

This study’s main goal is to determine the effects of combined cTBS over rIPL and SCRT on gesture performance and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia. In addition, we aim to investigate neurocognitive, social cognitive, motor, clinical and neural effects of both interventions as secondary outcome measures. As cTBS enhances neuroplasticity and improves use of neural resources (46, 74), we expect administration of cTBS to facilitate SCRT training effects. Additionally, we hypothesize that the expected improvement of gesture performance will have positive effects on functional outcome, as both have been reported to be linked in schizophrenia (20). At the neural level, we hypothesize that the brain activity of patients will converge to the brain activity of healthy controls after both interventions, especially within the praxis network (39, 40).

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) will include three patient groups (see Figure 1). First, group A will receive real cTBS and real SCRT. Second, group B will receive sham cTBS and real SCRT. Third, group C will receive no cTBS and sham SCRT. In this study, we will also include a fourth group consisting of healthy controls, who will be assessed twice without any intervention in between. We expect the combination of cTBS and SCRT to show positive effects on both primary and secondary outcomes in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. As such, we expect group A to have superior performance over group B and C in gesture performance and functional outcome after intervention (A > B > C).

FIGURE 1

Study Setup. We will randomize 72 schizophrenia patients in three different groups (24 patients per group). Group A will receive real cTBS and real SCRT. Group B will receive sham cTBS and real SCRT. Group C will receive no cTBS and sham SCRT. Both sham treatments are inactive interventions that mimic as closely as possible the real treatments. Group A and B will receive 10 cTBS sessions during the first two weeks of intervention. Additionally, Group A–C will receive 16 SCRT sessions for eight weeks. Outcomes will be measured during four different time points: baseline, after cTBS (week 2), after SCRT (week 8) and follow-up (week 32). We will also include a fourth group consisting of 24 healthy controls, who will be assessed twice (baseline and week 8) without any intervention in between.

Setting and Enrollment

Study Design

This will be a three-arm, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial of add-on brain stimulation and SCRT to improve nonverbal communication skills and overall functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. This single-site trial will be conducted at the University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Bern.

Study Population

Patients will be asked for participation at the outpatient departments of the University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Bern and will be screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID). Healthy participants will be recruited by word-of-mouth and flyers in public places (e.g., grocery stores, pharmacies, gyms) in Bern. Participants will be eligible for study entry if they meet the criteria listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age between 18 and 65 years |

| Right-handedness |

| Patients only: diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders according to DSM-5 |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Substance abuse or dependence other than nicotine |

| Past or current medical or neurological conditions associated with impaired or aberrant movement, such as brain tumors, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington disease, dystonia, or severe head trauma with subsequent loss of consciousness. |

| Epilepsy or other convulsions |

| History of any hearing problems or ringing in the ears |

| Standard exclusion criteria for MRI scanning and TMS, e.g., metal implants, claustrophobia |

| Women who are pregnant or breast feeding or intention to become pregnant during the study |

| Previous enrollment into the current study |

| Patients only: any TMS treatment in the past 3 months |

| Patients only: any cognitive remediation therapy in the past 2 years |

| Controls only: history of any psychiatric disorder or any first-degree relatives with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. |

Eligibility.

Interventions

Implementation of Real/Sham Continuous Theta Burst Stimulation

Patients will receive ten cTBS sessions in total during the first 2 weeks of intervention. Each session (sham and real cTBS) will last 17 min consisting of two 44 s stimulations over rIPL separated by a 15-min break. For each stimulation of 44 s, we will apply 801 pulses at 50 Hz over the right IPL at an intensity of 100% of the resting motor threshold. Hence, the entire session will consist of 1,602 pulses. Sham cTBS will be delivered with a placebo-coil without any magnetic emission.

Implementation of Real/Sham Social Cognitive Remediation Therapy

Real/sham SCRT will be conducted bi-weekly for 8 weeks, totaling 16 sessions of 90 min. Each group will consist of six to eight patients led by a head-therapist (VC) and a co-therapist (FW). INT-expert (DM) will train both therapists and supervises the course of the sessions.

For this trial, we will tailor an SCRT based on the INT manual (58, 59). This SCRT will include the entire social cognitive part of the original INT (consisting of a minimum of 30 sessions) and two INT neurocognitive modules. As such, we will use psychoeducation and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp) techniques. This intervention will have the main goal of improving gesture deficits in schizophrenia and will be separated in five blocks; each including neuro- and social cognitive MATRICS-domains (see Table 2). The first, third and fifth block will focus predominantly on using and interpreting nonverbal cues in social contexts. The second and fourth blocks will address memory and attention, both of which are essential for functioning in social interaction. Three sessions will be dedicated to each block, totaling 15 sessions overall. With each session, the content of the blocks will increase in complexity. A final 16th session will be added, in which the content delivered in all previous five blocks will be summarized.

TABLE 2

| Introductory session: Psychoeducation topics | Training session: Compensation and restitution sessions with interactive and computerized exercises |

Transfer session: Practicing coping strategies in daily life with homework |

|

|

Block 1:

Emotion perception and expression |

Six basic emotions: their function, their expression (e.g., gestures) and their effect on perception/attention |

Affect recognition and affect expression | Practicing newly learned affect recognition strategies with their regular environment |

|

Block 2:

Verbal/visual learning and memory |

Short term memory, long term memory and prospective memory | Mnemonic strategies (e.g., chunking, external memory aids such as calendars and post-its) | Practicing familiar and newly learned mnemonic strategies |

| Block 3: Social perception and theory of mind |

Key social stimuli and theory of mind | Observation of social encounters (e.g., with pictures, videos, and role play) and interpretation of social information | Practicing a more fact-oriented social perception (rather than assumptions-based) with their regular environment |

| Block 4: Working memory |

Selective attention, working memory and how to reduce distractibility | Cognitive flexibility, selective attention, ability to inhibit cognitive interference (e.g., with computer tasks) | Practicing newly learned attention-focusing strategies |

| Block 5: Social schema |

Norms and roles on social behavior and use of social knowledge | Social norms and behavioral sequences (e.g., with role play), recognition of own norm-deviating behavior and building strategies to change it if necessary, as well as coping with social stigma | Practicing newly learned social strategies in role play during group therapy and with their regular environment |

SCRT therapy contents a trained cognitive processes.

Each block will start with an introductory session, followed by a training session (i.e., compensation and restitution sessions), and a transfer session (see Table 2). During the introductory sessions, the MATRICS domains will be presented with a great focus on their everyday use and individual self-reference. The introductory sessions include psychoeducation on the respective neurocognitive and social domains. During the training sessions, we will determine patients’ strongest coping strategies, establish solution-oriented awareness, and train cognitive domains with various exercises (e.g., computerized cognitive tasks or role play exercises). The transfer sessions will work on the principle “rehearsal learning” (75, 76), meaning patients repeatedly apply the newly learned strategies in their daily life to restore social cognitive functions. The treatment goal will be to develop more coping strategies and enhance social skills to increase overall functioning. The therapists will follow a script for quality assurance and treatment fidelity.

Sham SCRT will consist of psychoeducation on sleep hygiene, exercise, stress, and music, as well as leisure activities, and mindfulness-based exercises (e.g., raisin meditation or walking meditation in a nearby park in Bern). Patients receiving this group therapy will also benefit from an interactive environment. The main difference with the real SCRT will be that sham SCRT will not include any (social) cognitive training, nor active transfer of skills into daily life.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Behavioral and Clinical Assessments

The primary outcome of this study will be hand gesture performance, which will be assessed with the Test of Upper Limb Apraxia (TULIA) (77). TULIA includes 48 items in two domains: Imitation (following demonstration) and pantomime (after verbal command). The test has three semantic categories of gestures: communicative (intransitive), object-related (transitive), or meaningless. Item ratings range from 0 to 5. If the participants make content errors (e.g., perseverations, substitutions), they will get 0–2 points per item. If the participants make spatial or temporal errors, they will get 3–4 points. Perfect performance equals 5 points, which is the maximum score per item. The highest TULIA total score is 240. A cutoff score will be used to measure gesture deficits in schizophrenia with < 210 TULIA total score (17). Gesture performance will be recorded on video and later evaluated by an independent examiner who is blinded to the groups or timing of the assessment. We will assess gesture performance using TULIA at four different time points (see Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Screening | Baseline | Week 2 tests | Week 8 tests | Follow-up | |

| TIME (week) | –4 to 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 32 |

| Enrollment | |||||

| Eligibility screening | X | ||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||

| Allocation | X | ||||

| Interventions | |||||

| Real and sham brain stimulation |

|

||||

| Real and sham group therapy |

|

||||

| Assessments | |||||

| Gesture tests | X | X | X | X | X |

| Clinical rating scales | X | X | X | X | |

| Community functioning | X | X | X | ||

| Neuroimaging | X | X | |||

Time-points of assessments.

Secondary outcomes will include additional nonverbal communication, cognitive, clinical, and functional assessments, as well as self-reports. Nonverbal communication will be tested with the Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (PONS) (78) assessing nonverbal social perception, and the modified postural knowledge task (79, 80) measuring gesture perception. Together, TULIA, PKT, and PONS assess nonverbal communication, as they include the production, the recognition, and the interpretation of gestures. History of symptoms and medication in patients will be assessed with The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) (81). Self-reports, clinical scales, motor scales, cognitive tests and functional assessments are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Assessments | References | |

| Self-reports | Brief Assessment of Gestures (BAG) | (95) |

| Self-report of negative symptoms (SNS) | (96) | |

| The satisfaction with therapy and therapist scale-revised (STTS-R) for group psychotherapy | (97) | |

| Psychopathology | Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) | (98) |

| Brief negative symptom scale (BNSS) | (99) | |

| Thought and language disorder (TALD) | (100) | |

| Frontal assessment battery (FAB) | (101) | |

| Bern psychopathology scale (BPS) | (102) | |

| Motor scales | Neurological evaluation scale (NES) | (103) |

| Bush Francis catatonia rating scale (BFCRS) | (104) | |

| Salpêtrière retardation rating scale (SRRS) | (105) | |

| Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) | (106) | |

| Abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) | (107) | |

| Behavioral tests | Postural knowledge test (PKT) | (79) |

| Profile of nonverbal sensitivity (PONS) | (78) | |

| Coin rotation | (108) | |

| Test of Upper Limb Apraxia (TULIA) | (77) | |

| Neuro- and social cognition | Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) | (109) |

| Digit span backward (DSB) | (110) | |

| Test of nonverbal Intelligence (TONI) | (111) | |

| EMOREC-B | (56) | |

| Hinting task (HT) | (112) | |

| EmBODY tool | (113) | |

| Functional assessments | Global assessment of functioning (GAF) | (88) |

| Social and occupational functioning assessment score (SOFAS) | (114) | |

| Personal and social performance (PSP) | (114) | |

| University of California, San Diego performance-based skills assessment brief (UPSA-b) | (115) | |

| Social level of functioning (SLOF) | (116) |

Primary and secondary outcomes.

FIGURE 2

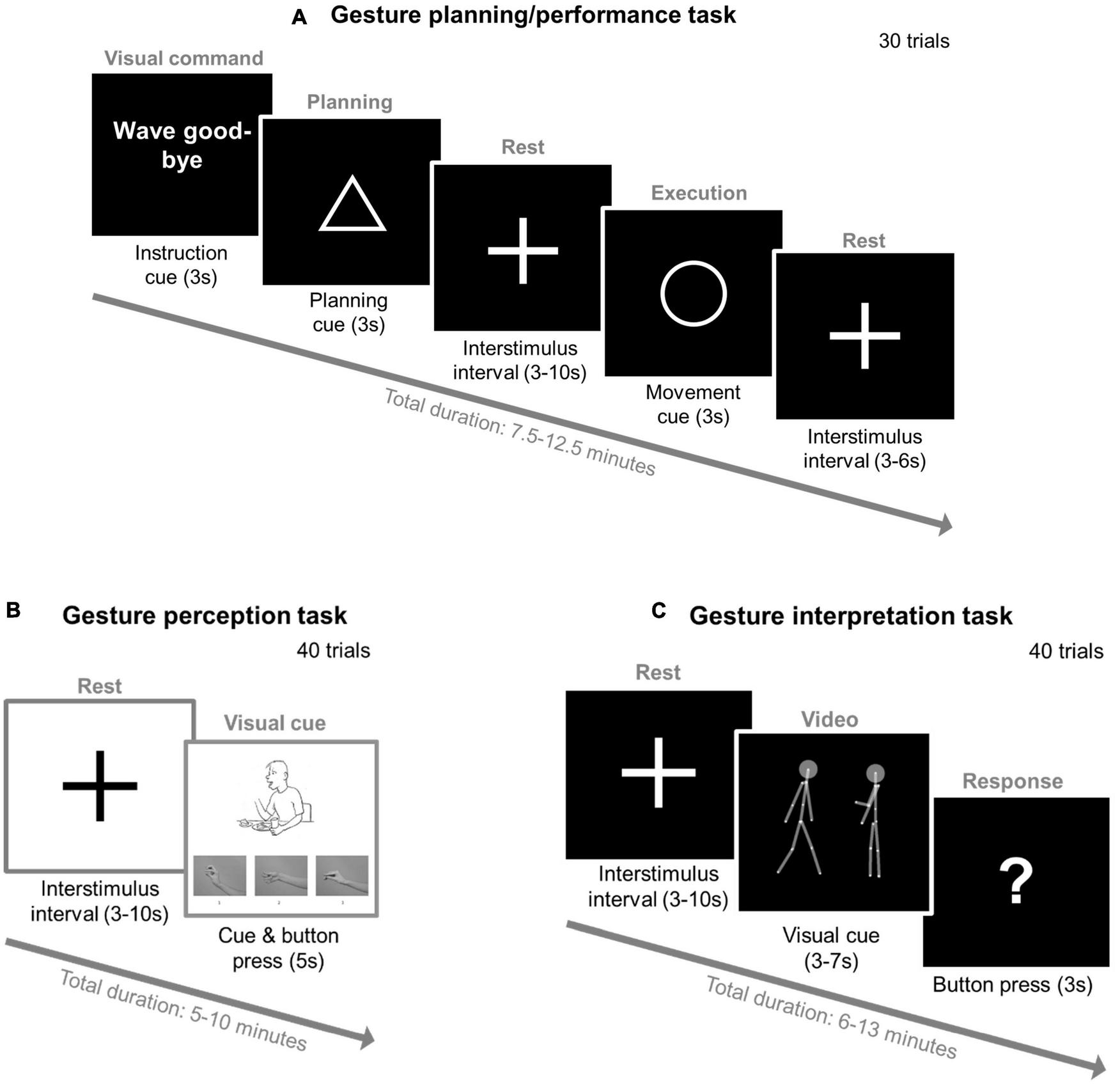

Three fMRI gesture tasks—experimental setup. (A) Gesture planning/performance task with the modified Test of Upper Limb Apraxia (TULIA). Participants will be presented with 20 hand gestures in a random order (e.g., wave good-bye) and 10 control sentences with no gesture performance expected (e.g., “the airline flight is delayed”). Each trial will start with an instruction (3 s), followed by a triangle (planning phase: 3 s), then a 3–10 s interstimulus interval with a fixation cross (3–10 s), a circle (execution phase: 3 s), another 3–6 s interstimulus interval, and then a new gesture of the next trial is presented. (B) Gesture perception task with the modified Postural knowledge task (PKT). Each trial will start with a fixation cross (3–10 s) followed by a picture (max. 5 s) where the hand of the presented figure will be removed. Participants’ task is to choose the correct hand gesture provided below using button presses of a hand pad inside the scanner (1, 2, and 3) and respond while the picture is still displayed. In the example provided the correct gesture is number two. (C) Gesture interpretation task with point-light displays (PLD). Each trial will start with a fixation cross (3–10 s) followed by a PLD video, after which a question mark will be displayed (3 s). The video will include two PLD figures: one on the right side and the other on the left side of the screen. During the video, one PLD will perform a gesture while the other PLD will either follow or imitate these performed gestures. Participants’ task will be to indicate with the button press of a hand pad which of the two PLD figures (left or right) is imitating or following the gestures of the other when the question mark will be displayed. The gray connecting lines and the two gray circles (i.e., PLDs’ heads) are a visual aid and will not be present in the actual experiment.

Outcomes will be measured during four different time points: baseline, after cTBS (week 2), after SCRT (week 8) and follow-up (week 32) (see Table 3). At baseline, week 8 and week 32, the primary and all secondary outcomes will be tested. At week 2, the primary and a few secondary outcomes (i.e., nonverbal communication and clinical assessments) will be measured. Additionally, at baseline and week 8, neuroimaging data will be acquired to test the neural effects of the treatments.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements

Neuroimaging will include structural T1, arterial spin labeling (ASL), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) resting state and fMRI tasks. MRI acquisition will be performed at a 3T SIEMENS MAGNETOM Prisma at the Swiss Institute for Translational and Entrepreneurial Medicine (SITEM), Bern, Switzerland. We will use a 20-channel radio-frequency head coil (Siemens, Germany) for all acquisitions.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Tasks

We will administer three different fMRI tasks to assess gesture planning/execution, perception, and interpretation (see Figure 2). First, gesture planning and performance will be assessed with an adapted version of the gesture task created by Stegmayer et al. (39) and Kroliczak and Frey (82). In an event related design, participants will be presented with 30 gestures in a random order: 10 meaningless (e.g., “raise your thumb and your index finger”), 10 meaningful gestures (e.g., “wave good-bye”) and 10 control sentences with no gesture performance expected (e.g., “the weather is bad”). Second, we will use the Postural Knowledge Task (PKT) (15, 26, 80) to assess participants’ gesture perception. Participants will be presented with pictures of people performing gestures (20 trials), while the hands executing those gestures are missing. Participants will be asked to choose the correct hand gesture from three choices provided. In the control condition (20 pictures), participants will be asked to indicate if the person performing the gesture is either male or female. Third, we will use the point-light-display (PLD) method to assess dynamic gesture perception. Here, human biological movements will be depicted by 12 point-light dots on the main joints of a human actor in the absence of any other visual characteristics (83–85). For our task, 40 videos of one PLD agent will be shown to perform different communicative gestures while the other PLD agent imitated/followed these performed gestures (26, 86). Participants’ task will be to identify which PLD was imitating/following the other.

Allocation and Randomization

Interventions will start in blocks as soon as 6–8 participants can be randomized to three groups: Group A, group B or group C (see Figure 1). Patients will not know which treatment they receive; they will be allocated to one of three treatment arms in a blinded manner.

Statistical Considerations and Plan

Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.15) in a repeated measures ANOVA with moderate-high correlation between time points (0.75), a power of 0.95 and an alpha = 0.05, we will need 72 patients (24 per group). In addition, a control group of 24 healthy subjects will be required. All four groups will be compared pre-to-post with an interval of 8 weeks (see Figure 1). The main effects of the combined interventions on the primary and secondary outcomes will be calculated in a repeated measures design including 3 main time points (Baseline, week 2, and week 8) and three patient groups (A, B, and C). With the latest SPSS and R versions, we also will run additional (partial) correlations, linear regressions, MANCOVAS using covariates (e.g., age, education, and medication).

Trial Status

Study recruitment started on the 17th December 2019. The first group started with both interventions on the 24th February 2020. The study was impacted by the federal measures against the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 2022, we recruited 65 patients and 36 healthy controls. We completed baseline assessments with 62 patients and 33 healthy controls. We finished week-8 assessments with 36 patients and 32 controls.

Discussion

Relevance of the Current Study

With this study, we will run one of the few prospective, sham-controlled RCTs addressing both gesture deficits and poor functioning in schizophrenia. Ameliorating functional outcome as a means of reintegrating patients into society has become one of the most central goals of psychiatric rehabilitation (87–89). Despite advances in antipsychotic medications and psychotherapies, functional recovery rates of schizophrenia patients have not increased substantially over the last 30 years (90, 91). Schizophrenia is not only a major burden for patients, but also a great economic strain for society, as patients with schizophrenia make heavy use of inpatient services and require financial support. It is urgent to develop psychiatric treatments that help patients to maintain interpersonal relationships and facilitate independent living. As gesture deficits in schizophrenia are highly correlated to overall functioning in daily life (20) and effective therapies reducing nonverbal communication deficits are lacking, it is clear that we need to establish interventions that tackle both (46, 92).

Advantages

The design of this RCT encompasses numerous advantages. The main strength of our study is the combination of two interventions; coupling brain stimulation with group therapy may exert cumulative therapeutic effects in gesturing and functioning in schizophrenia (20). Additionally, cTBS enhances neuroplasticity in schizophrenia patients (46, 74) and thus, may facilitate SCRT training effects. Thanks to the two comparators (sham cTBS and sham SCRT) we can evaluate the therapeutic effects of both interventions on behavioral, clinical, and neural levels. Also, we may find insights to predictors of treatment outcome. Further, the RCT design allows elimination of selection bias in treatment assignment and enables blinding from assessors and participants. Moreover, by collecting detailed demographic information over time, we will be able to correct for age, gender, education and antipsychotic medication dosage. Longitudinal data allows exploration of change in our patients, and thus, gives insight on the longevity of treatment effects. For example, our design may shed light on factors that are essential for the transfer of coping strategies. Most importantly, we are running one of the very few RCT on SCRT to involve acquisition of neuroimaging data before and after intervention. We can directly compare neural alterations to potential behavioral changes after the interventions. If this study proves to be successful it has the potential to be beneficial for other psychiatric disorders, which exhibit similar socio-cognitive dysfunctions such as depression (93, 94).

Limitations

This RCT entails a few limitations. First, we cannot eradicate the influence of medication; most patients suffering from schizophrenia are on antipsychotic treatment and other medication (e.g., blood pressure suppressants, antidepressants). However, for antipsychotic medication, we will control for Olanzapine equivalents in our statistical analyses. Second, we cannot eliminate gains linked to repeated test exposure as a result of retaking the same test under comparable conditions (i.e., retest effects). We counter these effects by randomizing the order of our test items for most of our assessments. Additionally, the time between most of our assessments makes training effects quite unlikely (i.e., 8 weeks, 32 weeks). Third, some of the data we collect are self-reports. Due to the subjective nature of self-reports, their psychometric aspects (e.g., reliability and validity) can be questionable or subject to biases (e.g., response bias). However, self-reports are necessary. For example, it is essential to compare patients’ subjective symptoms before and after intervention to find out if we are helping them. Fourth, another concern is the generalizability of the trial results. Participation in our study is only appropriate for a subgroup of schizophrenia patients, as it consists of 30 meetings in 3 months. As such, we can only include stable outpatients with good time management, commitment and tolerance to additional stress. This might cause the data collection to become arduous and dropout rates to be high.

Conclusion

In summary, this study explores the combination of cTBS and SCRT to improve gesture skills and social functioning in schizophrenia. This research project is of great importance as treatment options alleviating nonverbal communication deficits are clearly lacking. If this study proves to be successful, it has the potential to change the course of current treatment methods and greatly improve social functioning, as well as the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern (KEK). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

VC contributed to recruits participants, organizes the study procedures, conducts assessments, carries out both interventions, and drafted the manuscript. AP supervised the study procedures. DM trained the head therapist and co-therapists in SCRT and supervised the SCRT sessions. SW designed the study, obtained funding and ethics approval, wrote the study protocol, and registered the study at the clinical trials. All authors discussed and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant #184717 to SW).

Acknowledgments

We thank Florian Weiss (FW) and Florence Ibrahim for being our SCRT co-therapists. We thank Karl Verfaillie for providing us with the PLD videos.

Conflict of interest

SW was received honoraria from Mepha, Neurolite, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Sunovion. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ASL

arterial spin labeling

- BOLD

blood-oxygen-level-dependent imaging

- CBTp

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis

- cTBS:

continuous theta burst stimulation

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- IFG

inferior frontal gyrus

- iTBS

intermittent theta burst stimulation

- IPL

inferior parietal lobule

- MATRICS

Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PKT

postural knowledge test

- PLD

point-light-display

- PONS

profile of nonverbal sensitivity

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- rIPL

right inferior parietal lobule

- rTMS

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

- SCRT

social cognitive remediation therapy

- SMA

supplementary motor area

- TULIA

Test of upper limb apraxia.

References

1.

Dollfus S Lyne J . Negative symptoms: history of the concept and their position in diagnosis of schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. (2017) 186:3–7. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.024

2.

Carra G Crocamo C Angermeyer M Brugha T Toumi M Bebbington P . Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a longitudinal analysis using latent variable structural equation modelling.Schizophr Res. (2019) 204:58–64. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.08.018

3.

Mccutcheon RA Reis Marques T Howes OD . Schizophrenia-an overview.JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:201–10. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3360

4.

De Sousa P Sellwood W Griffiths M Bentall RP . Disorganisation, thought disorder and socio-cognitive functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders.Br J Psychiatry. (2019) 214:103–12. 10.1192/bjp.2018.160

5.

Walther S Strik W . Motor symptoms and schizophrenia.Neuropsychobiology. (2012) 66:77–92. 10.1159/000339456

6.

Walther S Mittal VA . Motor system pathology in psychosis.Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:97. 10.1007/s11920-017-0856-9

7.

Nadesalingam N Chapellier V Lefebvre S Pavlidou A Stegmayer K Alexaki D et al Motor abnormalities are associated with poor social and functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. (2022) 115:152307. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152307

8.

Tandon R Nasrallah HA Keshavan MS . Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4. Clinical features and conceptualization.Schizophr Res. (2009) 110:1–23. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.005

9.

Guo JY Ragland JD Carter CS . Memory and cognition in schizophrenia.Mol Psychiatry. (2019) 24:633–42. 10.1038/s41380-018-0231-1

10.

Nuechterlein KH Barch DM Gold JM Goldberg TE Green MF Heaton RK . Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. (2004) 72:29–39. 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007

11.

Frith CD Frith U . Social cognition in humans.Curr Biol. (2007) 17:R724–32. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.068

12.

Adolphs R . The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge.Annu Rev Psychol. (2009) 60:693–716. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514

13.

Green MF Horan WP Lee J . Social cognition in schizophrenia.Nat Rev Neurosci. (2015) 16:620–31. 10.1038/nrn4005

14.

Toomey R Schuldberg D Corrigan P Green MF . Nonverbal social perception and symptomatology in schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. (2002) 53:83–91. 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00177-3

15.

Walther S Stegmayer K Sulzbacher J Vanbellingen T Muri R Strik W et al Nonverbal social communication and gesture control in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:338–45. 10.1093/schbul/sbu222

16.

Chapellier V Pavlidou A Maderthaner L Von Känel S Walther S . The impact of poor nonverbal social perception on functional capacity in schizophrenia.Front Psychol. (2022) 13:804093. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.804093

17.

Walther S Vanbellingen T Muri R Strik W Bohlhalter S . Impaired gesture performance in schizophrenia: particular vulnerability of meaningless pantomimes.Neuropsychologia. (2013) 51:2674–8. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.08.017

18.

Walther S Vanbellingen T Muri R Strik W Bohlhalter S . Impaired pantomime in schizophrenia: association with frontal lobe function.Cortex. (2013) 49:520–7. 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.12.008

19.

Walther S Mittal VA Stegmayer K Bohlhalter S . Gesture deficits and apraxia in schizophrenia.Cortex. (2020) 133:65–75. 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.09.017

20.

Walther S Eisenhardt S Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T Muri R Strik W et al Gesture performance in schizophrenia predicts functional outcome after 6 months. Schizophr Bull. (2016) 42:1326–33. 10.1093/schbul/sbw124

21.

Walther S Mittal VA . Why we should take a closer look at gestures.Schizophr Bull. (2016) 42:259–61. 10.1093/schbul/sbv229

22.

Goldin-Meadow S Alibali MW . Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language.Annu Rev Psychol. (2013) 64:257–83. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143802

23.

Walther S Alexaki D Stegmayer K Vanbellingen T Bohlhalter S . Conceptual disorganization impairs hand gesture performance in schizophrenia.Schizophr Res. (2020) 215:467–8. 10.1016/j.schres.2019.09.001

24.

Matthews N Gold BJ Sekuler R Park S . Gesture imitation in schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:94–101. 10.1093/schbul/sbr062

25.

Lavelle M Dimic S Wildgrube C Mccabe R Priebe S . Non-verbal communication in meetings of psychiatrists and patients with schizophrenia.Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2015) 131:197–205. 10.1111/acps.12319

26.

Pavlidou A Chapellier V Maderthaner L Von Känel S Walther S . Using dynamic point light display stimuli to assess gesture deficits in schizophrenia.Schizophr Res Cogn. (2022) 28:100240. 10.1016/j.scog.2022.100240

27.

Lavelle M Healey PG Mccabe R . Is nonverbal communication disrupted in interactions involving patients with schizophrenia?Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:1150–8. 10.1093/schbul/sbs091

28.

Worswick E Dimic S Wildgrube C Priebe S . Negative Symptoms and avoidance of social interaction: a study of non-verbal behaviour.Psychopathology. (2018) 51:1–9. 10.1159/000484414

29.

Berndl K Von Cranach M Grusser OJ . Impairment of perception and recognition of faces, mimic expression and gestures in schizophrenic patients.Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. (1986) 235:282–91. 10.1007/BF00515915

30.

Bucci S Startup M Wynn P Heathcote A Baker A Lewin TJ . Referential delusions of communication and reality discrimination deficits in psychosis.Br J Clin Psychol. (2008) 47:323–34. 10.1348/014466508X280952

31.

Nagels A Kircher T Grosvald M Steines M Straube B . Evidence for gesture-speech mismatch detection impairments in schizophrenia.Psychiatry Res. (2019) 273:15–21. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.107

32.

Bohlhalter S Hattori N Wheaton L Fridman E Shamim EA Garraux G et al Gesture subtype-dependent left lateralization of praxis planning: an event-related fMRI study. Cereb Cortex. (2009) 19:1256–62. 10.1093/cercor/bhn168

33.

Hermsdorfer J Li Y Randerath J Roby-Brami A Goldenberg G . Tool use kinematics across different modes of execution. Implications for action representation and apraxia.Cortex. (2013) 49:184–99. 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.10.010

34.

Thakkar KN Peterman JS Park S . Altered brain activation during action imitation and observation in schizophrenia: a translational approach to investigating social dysfunction in schizophrenia.Am J Psychiatry. (2014) 171:539–48. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040498

35.

Stegmayer K Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T Federspiel A Moor J Wiest R et al Structural brain correlates of defective gesture performance in schizophrenia. Cortex. (2016) 78:125–37. 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.02.014

36.

Viher PV Stegmayer K Giezendanner S Federspiel A Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T et al Cerebral white matter structure is associated with DSM-5 schizophrenia symptom dimensions. NeuroImage Clin. (2016) 12:93–9. 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.06.013

37.

Viher PV Stegmayer K Kubicki M Karmacharya S Lyall AE Federspiel A et al The cortical signature of impaired gesturing: findings from schizophrenia. NeuroImage Clin. (2018) 17:213–21. 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.10.017

38.

Viher PV Abdulkadir A Savadijev P Stegmayer K Kubicki M Makris N et al Structural organization of the praxis network predicts gesture production: evidence from healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Cortex. (2020) 132:322–33. 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.05.023

39.

Stegmayer K Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T Federspiel A Wiest R Muri RM et al Limbic interference during social action planning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2018) 44:359–68. 10.1093/schbul/sbx059

40.

Wuthrich F Viher PV Stegmayer K Federspiel A Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T et al Dysbalanced resting-state functional connectivity within the praxis network is linked to gesture deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 46:905–15. 10.1093/schbul/sbaa008

41.

Fogassi L Luppino G . Motor functions of the parietal lobe.Curr Opin Neurobiol. (2005) 15:626–31. 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.015

42.

Gottlieb J . From thought to action: the parietal cortex as a bridge between perception, action, and cognition.Neuron. (2007) 53:9–16. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.009

43.

Goldenberg G . Apraxia and the parietal lobes.Neuropsychologia. (2009) 47:1449–59. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.014

44.

Binkofski F Buccino G . Motor functions of the broca’s region.Brain Lang. (2004) 89:362–9. 10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00358-4

45.

Chung CL Mak MK Hallett M . Transcranial magnetic stimulation promotes gait training in Parkinson disease.Ann Neurol. (2020) 88:933–45. 10.1002/ana.25881

46.

Lefebvre S Pavlidou A Walther S . What is the potential of neurostimulation in the treatment of motor symptoms in schizophrenia?Expert Rev Neurother. (2020) 20:697–706. 10.1080/14737175.2020.1775586

47.

Walther S Alexaki D Schoretsanits G Weiss F Vladimirova I Stegmayer K et al Inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat psychomotor slowing: a transdiagnostic, mechanism-based double-blind controlled trial. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 1:sgaa020. 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa020

48.

Walther S Kunz M Muller M Zurcher C Vladimirova I Bachofner H et al Single session transcranial magnetic stimulation ameliorates hand gesture deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 46:286–93. 10.1093/schbul/sbz078

49.

Lefaucheur JP . Transcranial magnetic stimulation.Handb Clin Neurol. (2019) 160:559–80. 10.1016/B978-0-444-64032-1.00037-0

50.

Vanbellingen T Pastore-Wapp M Kubel S Nyffeler T Schupfer AC Kiefer C et al Interhemispheric facilitation of gesturing: a combined theta burst stimulation and diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain Stimul. (2020) 13:457–63. 10.1016/j.brs.2019.12.013

51.

Couture SM Penn DL Roberts DL . The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review.Schizophr Bull. (2006) 32:S44–63. 10.1093/schbul/sbl029

52.

Mancuso F Horan WP Kern RS Green MF . Social cognition in psychosis: multidimensional structure, clinical correlates, and relationship with functional outcome.Schizophr Res. (2011) 125:143–51. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.007

53.

Schmidt SJ Mueller DR Roder V . Social cognition as a mediator variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: empirical review and new results by structural equation modeling.Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:S41–54. 10.1093/schbul/sbr079

54.

Green MF Nuechterlein KH . The MATRICS initiative: developing a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials.Schizophr Res. (2004) 72:1–3. 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.006

55.

Brown EC Tas C Brune M . Potential therapeutic avenues to tackle social cognition problems in schizophrenia.Expert Rev Neurother. (2012) 12:71–81. 10.1586/ern.11.183

56.

Mueller DR Schmidt SJ Roder V . One-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of integrated neurocognitive therapy for schizophrenia outpatients.Schizophr Bull. (2015) 41:604–16. 10.1093/schbul/sbu223

57.

Moritz S Klein JP Lysaker PH Mehl S . Metacognitive and cognitive-behavioral interventions for psychosis: new developments.Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2019) 21:309–17. 10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.3/smoritz

58.

Mueller DR Roder V . Integrated psychological therapy for schizophrenia patients.Expert Rev Neurother. (2007) 7:1–3. 10.1586/14737175.7.1.1

59.

Roder V Muller DR. INT – Integrierte Neurokognitive Therapie Bei Schizophren Erkrankten. Berlin: Springer (2013). 10.1007/978-3-642-21440-0

60.

Mueller DR Khalesi Z Benzing V Castiglione CI Roder V . Does integrated neurocognitive therapy (INT) reduce severe negative symptoms in schizophrenia outpatients?Schizophr Res. (2017) 188:92–7. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.037

61.

De Mare A Cantarella M Galeoto G . Effectiveness of integrated neurocognitive therapy on cognitive impairment and functional outcome for schizophrenia outpatients.Schizophr Res Treatment. (2018) 2018:2360697. 10.1155/2018/2360697

62.

Mueller DR Khalesi Z Roder V . Can cognitive remediation in groups prevent relapses? Results of a 1-year follow-up randomized controlled trial.J Nerv Ment Dis. (2020) 208:362–70. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001146

63.

Wolwer W Frommann N . Social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: generalization of effects of the training of affect recognition (TAR).Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:S63–70. 10.1093/schbul/sbr071

64.

Wolwer W Frommann N Halfmann S Piaszek A Streit M Gaebel W . Remediation of impairments in facial affect recognition in schizophrenia: efficacy and specificity of a new training program.Schizophr Res. (2005) 80:295–303. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.018

65.

Grant N Lawrence M Preti A Wykes T Cella M . Social cognition interventions for people with schizophrenia: a systematic review focussing on methodological quality and intervention modality.Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 56:55–64. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.06.001

66.

Dark F Harris M Gore-Jones V Newman E Whiteford H . Implementing cognitive remediation and social cognitive interaction training into standard psychosis care.BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:458. 10.1186/s12913-018-3240-5

67.

Wykes T Van Der Gaag M . Is it time to develop a new cognitive therapy for psychosis–cognitive remediation therapy (CRT)?Clin Psychol Rev. (2001) 21:1227–56. 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00104-0

68.

Cavallaro R Anselmetti S Poletti S Bechi M Ermoli E Cocchi F et al Computer-aided neurocognitive remediation as an enhancing strategy for schizophrenia rehabilitation. Psychiatry Res. (2009) 169:191–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.027

69.

Mulller DR Roder V Brenner HD . Effectiveness of integrated psychological therapy (IPT) for schizophrenia patients: a meta-analysis.Schizophr Res. (2004) 67:202–202.

70.

Roder V Muller DR Brenner HD . Integrated psychological therapy (IPT) for schizophrenia patients in different settings, patient sub samples and site conditions: a meta-analysis.Eur Psychiatry. (2004) 19:76s–7s.

71.

Kopelowicz A Liberman RP Zarate R . Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull. (2006) 32 Suppl 1:S12–23. 10.1093/schbul/sbl023

72.

Mcgurk SR Twamley EW Sitzer DI Mchugo GJ Mueser KT . A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia.Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164:1791–802. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906

73.

Eack SM Pogue-Geile MF Greenwald DP Hogarty SS Keshavan MS . Mechanisms of functional improvement in a 2-year trial of cognitive enhancement therapy for early schizophrenia.Psychol Med. (2011) 41:1253–61. 10.1017/S0033291710001765

74.

Goldsworthy MR Vallence AM Yang R Pitcher JB Ridding MC . Combined transcranial alternating current stimulation and continuous theta burst stimulation: a novel approach for neuroplasticity induction.Eur J Neurosci. (2016) 43:572–9. 10.1111/ejn.13142

75.

Kolb AY Kolb DA . Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential learning in higher education.Acad Manag Learn Edu. (2005) 4:193–212. 10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

76.

Beidas RS Cross W Dorsey S . Show me, don’t tell me: behavioral rehearsal as a training and analogue fidelity tool.Cogn Behav Pract. (2014) 21:1–11. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002

77.

Vanbellingen T Kersten B Van Hemelrijk B Van De Winckel A Bertschi M Muri R et al Comprehensive assessment of gesture production: a new test of upper limb apraxia (TULIA). Eur J Neurol. (2010) 17:59–66. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02741.x

78.

Rosenthal R Hall JA Di Matteo MR Rogers PL Archer D . Sensitivity toNonverbal Communication: The PONS Test. Baltimore, MD: John HopkinsUniversity Press.

79.

Mozaz M Roth LJG Anderson JM Crucian GP Heilman KM . Postural knowledge of transitive pantomimes and intransitive gestures.J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2002) 8:958–62. 10.1017/S1355617702870114

80.

Bohlhalter S Vanbellingen T Bertschi M Wurtz P Cazzoli D Nyffeler T et al Interference with gesture production by theta burst stimulation over left inferior frontal cortex. Clin Neurophysiol. (2011) 122:1197–202. 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.11.008

81.

Andreasen NC Flaum M Arndt S . The comprehensive assessment of symptoms and history (Cash) – an instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology.Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1992) 49:615–23. 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080023004

82.

Kroliczak G Frey SH . A common network in the left cerebral hemisphere represents planning of tool use pantomimes and familiar intransitive gestures at the hand-independent level.Cerebral Cortex. (2009) 19:2396–410. 10.1093/cercor/bhn261

83.

Johansson G . Visual perception of biological motion and a model for its analysis.Percept Psychophys. (1973) 14:201–11. 10.3758/BF03212378

84.

Pavlidou A Schnitzler A Lange J . Interactions between visual and motor areas during the recognition of plausible actions as revealed by magnetoencephalography.Hum Brain Mapp. (2014) 35:581–92. 10.1002/hbm.22207

85.

Pavlidou A Schnitzler A Lange J . Distinct spatio-temporal profiles of beta-oscillations within visual and sensorimotor areas during action recognition as revealed by MEG.Cortex. (2014) 54:106–16. 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.02.007

86.

Manera V Schouten B Becchio C Bara BG Verfaillie K . Inferring intentions from biological motion: a stimulus set of point-light communicative interactions.Behav Res Methods. (2010) 42:168–78. 10.3758/BRM.42.1.168

87.

Green MF Olivier B Crawley JN Penn DL Silverstein S . Social cognition in schizophrenia: recommendations from the measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia new approaches conference.Schizophr Bull. (2005) 31:882–7. 10.1093/schbul/sbi049

88.

Robertson DA Hargreaves A Kelleher EB Morris D Gill M Corvin A et al Social dysfunction in schizophrenia: an investigation of the GAF scale’s sensitivity to deficits in social cognition. Schizophr Res. (2013) 146:363–5. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.016

89.

Tandon R . Definition of psychotic disorders in the DSM-5 too radical, too conservative, or just right!Schizophr Res. (2013) 150:1–2. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.08.002

90.

Jaaskelainen E Juola P Hirvonen N Mcgrath JJ Saha S Isohanni M et al A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (2013) 39:1296–306. 10.1093/schbul/sbs130

91.

Shivashankar S Telfer S Arunagiriraj J Mckinnon M Jauhar S Krishnadas R et al Has the prevalence, clinical presentation and social functioning of schizophrenia changed over the last 25 years? Nithsdale schizophrenia survey revisited. Schizophr Res. (2013) 146:349–56. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.006

92.

Pavlidou A Walther S . Using virtual reality as a tool in the rehabilitation of movement abnormalities in schizophrenia.Front Psychol. (2021) 11:607312. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607312

93.

Suffel A Nagels A Steines M Kircher T Straube B . Feeling addressed! The neural processing of social communicative cues in patients with major depression.Hum Brain Mapp. (2020) 41:3541–54. 10.1002/hbm.25027

94.

Pavlidou A Viher PV Bachofner H Weiss F Stegmayer K Shankman SA et al Hand gesture performance is impaired in major depressive disorder: a matter of working memory performance? J Affect Disord. (2021) 292:81–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.055

95.

Nagels A Kircher T Steines M Grosvald M Straube B . A brief self-rating scale for the assessment of individual differences in gesture perception and production.Learn Individ Differ. (2015) 39:73–80. 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.03.008

96.

Dollfus S Mach C Morello R . Self-evaluation of negative symptoms: a novel tool to assess negative symptoms.Schizophr Bull. (2016) 42:571–8. 10.1093/schbul/sbv161

97.

Oei TPS Shuttlewood GJ . Development of a satisfaction with therapy and therapist scale.Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (1999) 33:748–53. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00628.x

98.

Kay SR Fiszbein A Opler LA . The positive and negative syndrome scale (Panss) for schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

99.

Kirkpatrick B Strauss GP Linh N Fischer BA Daniel DG Cienfuegos A et al The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. (2011) 37:300–5. 10.1093/schbul/sbq059

100.

Kircher T Krug A Stratmann M Ghazi S Schales C Frauenheim M et al A rating scale for the assessment of objective and subjective formal thought and language disorder (TALD). Schizophr Res. (2014) 160:216–21. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.024

101.

Dubois B Slachevsky A Litvan I Pillon B . The FAB – a frontal assessment battery at bedside.Neurology. (2000) 55:1621–6. 10.1212/WNL.55.11.1621

102.

Strik W Wopfner A Horn H Koschorke P Razavi N Walther S et al The bern psychopathology scale for the assessment of system-specific psychotic symptoms. Neuropsychobiology. (2010) 61:197–209. 10.1159/000297737

103.

Buchanan RW Heinrichs DW . The neurological evaluation scale (Nes) – a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia.Psychiatry Res. (1989) 27:335–50. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90148-0

104.

Bush G Fink M Petrides G Dowling F Francis A . Catatonia.1. Rating scale and standardized examination.Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1996) 93:129–36. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x

105.

Dantchev N Widlocher DJ . The measurement of retardation in depression.J Clin Psychiatry. (1998) 59:19–25.

106.

Fahn S Elton R . Members of the UPDRS development committee the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: FahnSMarsdenCDCalneDBGoldsteinMeditors. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. (Florham Park, NJ: McMellam Health Care Information) (1987). p. 153–63.

107.

Guy W. ”ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication (ADM). Rockville: MD: National Institute of Mental Health (1976). p. 76–338.

108.

Gebhardt S Hartling F Hanke M Mittendorf M Theisen FM Wolf-Ostermann K et al Prevalence of movement disorders in adolescent patients with schizophrenia and in relationship to predominantly atypical antipsychotic treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2006) 15:371–82. 10.1007/s00787-006-0544-5

109.

Green MF Penn DL Bentall R Carpenter WT Gaebel W Gur RC et al Social cognition in schizophrenia: an NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities. Schizophr Bull. (2008) 34:1211–20. 10.1093/schbul/sbm145

110.

Blackburn HL Benton AL . Revised administration and scoring of the digit span test.J Consult Psychol. (1957) 21:139–43. 10.1037/h0047235

111.

Brown L Sherbenou RJ Johnsen SK. Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (TONI). 3rd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed Inc (1997).

112.

Thaler NS Strauss GP Sutton GP Vertinski M Ringdahl EN Snyder JS et al Emotion perception abnormalities across sensory modalities in bipolar disorder with psychotic features and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2013) 147:287–92. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.001

113.

Nummenmaa L Glerean E Hari R Hietanen JK . Bodily maps of emotions.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:646–51. 10.1073/pnas.1321664111

114.

Morosini PL Magliano L Brambilla L Ugolini S Pioli R . Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV social and occupational functioning assessment scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning.Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2000) 101:323–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2000.tb10933.x

115.

Mausbach BT Depp CA Bowie CR Harvey PD Mcgrath JA Thronquist MH et al Sensitivity and specificity of the UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA-B) for identifying functional milestones in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2011) 132:165–70. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.022

116.

Schneider LC Struening EL . Slof – a behavioral rating-scale for assessing the mentally-Ill.Soc Work Res Abstr. (1983) 19:9–21. 10.1093/swra/19.3.9

Summary

Keywords

communication, social cognition, psychosis, theta burst stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, intervention, cognitive remediation, schizophrenia

Citation

Chapellier V, Pavlidou A, Mueller DR and Walther S (2022) Brain Stimulation and Group Therapy to Improve Gesture and Social Skills in Schizophrenia—The Study Protocol of a Randomized, Sham-Controlled, Three-Arm, Double-Blind Trial. Front. Psychiatry 13:909703. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.909703

Received

27 April 2022

Accepted

13 June 2022

Published

07 July 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Luca De Peri, Cantonal Sociopsychiatric Organization, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Stefano Barlati, University of Brescia, Italy; Daria Smirnova, Samara State Medical University, Russia

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Chapellier, Pavlidou, Mueller and Walther.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria Chapellier, victoria.chapellier@upd.unibe.ch

This article was submitted to Schizophrenia, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.