- 1Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Introduction: Cannabis was legalized in Canada in October 2018, regulating the production, distribution, sale, and possession of dried cannabis and cannabis oils. Additional products were legalized 1 year later, including edibles, concentrates, and topicals, with new lines of commercial products coming to market. Ontario is the most populous province in Canada and has the largest cannabis market with the highest number of in-person retail stores and the most cannabis products available online. This study aims to create a profile of products available to consumers three years after legalization by summarizing types of products, THC and CBD potency, plant type, and prices of product sub-categories.

Methods: We extracted data from the website of the Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS)—the public agency overseeing the only online store and sole wholesaler to all authorized in-person stores—in the first quarter of 2022 (January 19–March 23). We used descriptive analyses to summarize the data. A total of 1,771 available products were mapped by route of administration into inhalation (smoking, vaping, and concentrates), ingestible (edibles, beverages, oils, and capsules) and topical.

Results: Most inhalation products included ≥20%/g THC (dried flower: 94%; cartridges: 96%; resin: 100%) while ingestible products had similar proportions of THC and CBD content. Indica-dominant products tend to be more prominent in inhalation products while sativa-dominant products tend to be more prominent in ingestible products. The average sale price of cannabis was 9.30 $/g for dried flower, 5.79 $/0.1g for cartridges, 54.82 $/g for resin, 3.21 $/unit for soft chews, 1.37 $/ml for drops, 1.52 $/unit for capsules, and 39.94 $/product for topicals.

Discussion: In summary, a wide variety of cannabis products were available to Ontarians for different routes of administration and provides numerous indica-dominant, sativa-dominant, and hybrid/blend options. The current market for inhalation products however is geared towards the commercialization of high-THC products.

Introduction

Canada was the second nation globally to legally regulate the production, distribution, sale, and possession of dried cannabis and cannabis oils in October of 2018 (1). A “second wave” of legalization came into effect in October 2019, regulating edibles, high-potency concentrates, and topicals (2), with new lines of commercial products available by early 2020. One of the main goals of legalization was to provide safe, legal access to cannabis products (3), enabling the legal industry to compete with the illegal market. The legalization of non-medical cannabis in Canada occurred under the Cannabis Act, which regulates cannabis nationally, but under Canada’s constitutional division of powers, each of the 10 provinces and 3 territories developed their own laws and regulatory systems (1). Ontario, Canada’s most populous province and largest cannabis market, follows a hybrid model where a public agency is the sole wholesaler to all authorized in-person stores—all of which are private—and also provides direct access to the public through the only online store.

Purchasing behaviors of consumers are influenced by cannabis prices and availability in the illegal and legal markets (4). In the US, cannabis use is higher in states that have legalized cannabis, with dried cannabis being the most dominant form (5). It is too early to determine the impact of legalization in Canada as the legal market continues to evolve, but early evidence suggests increased use in adults, mixed effects in adolescent use and on driving under the influence of cannabis, increases in pediatric emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and decreases in arrests and convictions (6–13). Given the acute and long-term health risks associated with cannabis containing high levels of THC (14–17), documenting the potency of the cannabis products available in the legal market is of interest to public health.

One year post-legalization, a Canadian study found that the top 10% of cannabis users (those with the highest cumulative cannabis use) accounted for about two-thirds of cannabis consumption, with 40% of the cannabis consumed in the form of flower products (18). At that time, legal cannabis sales covered about 33% of Canada’s cannabis consumption (19). Two years post-legalization, there were a total of 1,183 legal cannabis stores in Canada (20). Three years post-legalization, Ontario had the highest number of in-person retail stores (n = 1,974) and the highest number of products available online (n = 1,685) among all the provinces and territories (21, 22). The legal market has expanded to an estimated 57% of sales as of the last quarter of 2021, making progressive gains in the displacement of the illegal market (23).

Our aim was to create a profile of the products available to adult consumers in Ontario—just over three years post-legalization—and report their THC and CBD potency, plant type (e.g., indica-dominant, sativa-dominant, hybrid), and price. To do so, we cataloged products listed on the website of the Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS), the public agency overseeing the only online store and sole wholesaler to all authorized in-person stores. We do not present sales data which are available elsewhere for approximately the same period (23).

Materials and methods

This is a cross-sectional study designed to produce a profile of the legal cannabis market in Ontario three years post-legalization. We extracted data from the OCS website to document the THC and CBD potency, plant type, and price of all products available to purchase by Ontario consumers over a span of two months (19 January–23 March 2022) (22). During data extraction, FT and YL manually entered information from each cannabis product into an Excel spreadsheet. Any unavailable or unlisted information was marked as “N/A”. We used descriptive statistics [counts, means (M), standard deviations (SD), and ranges] using Excel functions. FT used pivot tables, sorted columns alphabetically, and counted each product individually to determine counts of high potency products and plant types. We also mapped the product categories and subcategories provided in the OCS website by route of administration to provide a more meaningful consumer perspective.

Products on the OCS website are listed with a range of values for both THC and CBD content (in%/g or mg/unit), rather than a single THC or CBD value as it is presented on the label of the individual product purchased by consumers. By design, regulations placed THC limits per package on ingestible products (e.g., maximum of 10 mg of THC per package for edibles). Thus, we calculated the average for each product THC and CBD range and then averaged the THC and CBD potencies of all products by their sub-category. Also, the OCS labels products that contain 20%/g or greater THC as “very strong THC” levels (OCS (22)). We calculated the frequency and proportion of very strong THC products using the unit%/g from each product. As the OCS does not define “very strong CBD” levels, we labeled any product with an average value above 5%/g as very strong CBD. We then calculated the number of very strong THC and CBD products by product sub-category using pivot tables, alphabetical sorting, and manual counting. For plant type, we sorted alphabetically and manually counted all the products categorized as blend, hybrid, indica-dominant, or sativa-dominant for each of the sub-categories.

In terms of price, a single product often had multiple selling prices listed depending on the quantity available for purchase, so we calculated the average of the lowest and highest selling price for each product and then calculated the average price for each sub-category (in $/g, $/0.1g, $/ml, or $/unit). In addition, we calculated the minimum selling price and the maximum selling price for each sub-category. These average selling prices allow us to approximate an estimate of how much money a consumer would spend to purchase a particular product in bulk.

Our study cataloged all the products available in the OCS during the period of observation and most dried flower products were only available in one or two quantities while pre-roll products were available in 20 different quantities (ranging from 0.25 to 30g), making it difficult to report average prices for pre-determined quantities as previous studies have done (24–27). Thus, the lowest and highest price per gram of every product was used for clarity.

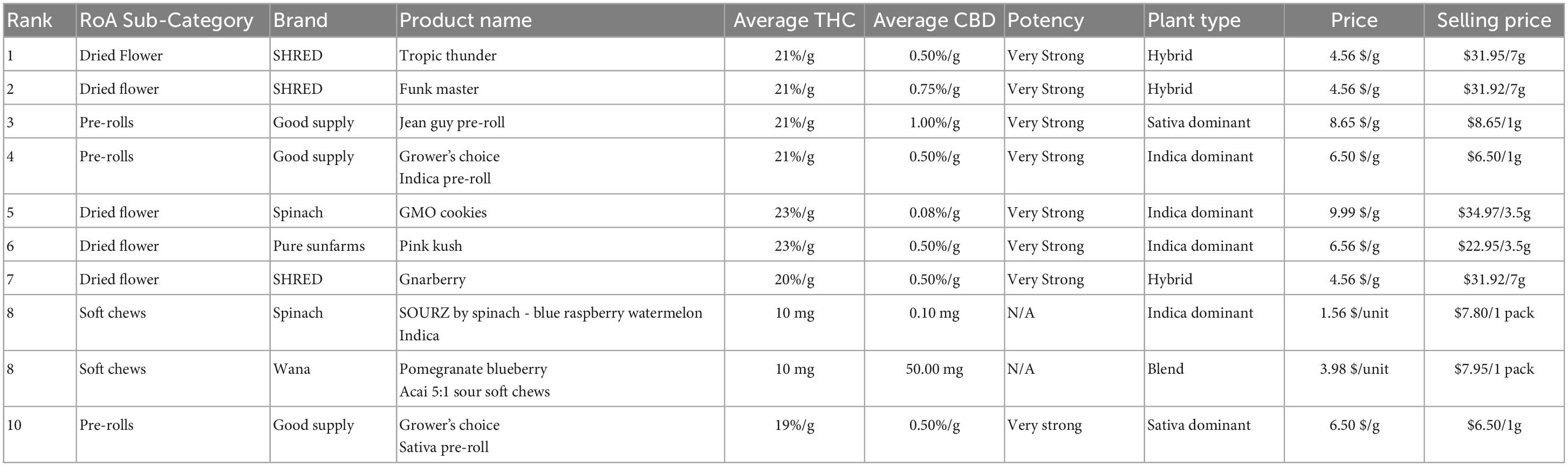

The top 10 cannabis products by units sold in Ontario retail stores were listed in the OCS’s January to March 2022 quarterly review (23). We used our Excel spreadsheet with the data extracted from the OCS website to provide more information about each of these ten products, including THC and CBD potency, plant type, and price.

Results

Product types and routes of administration

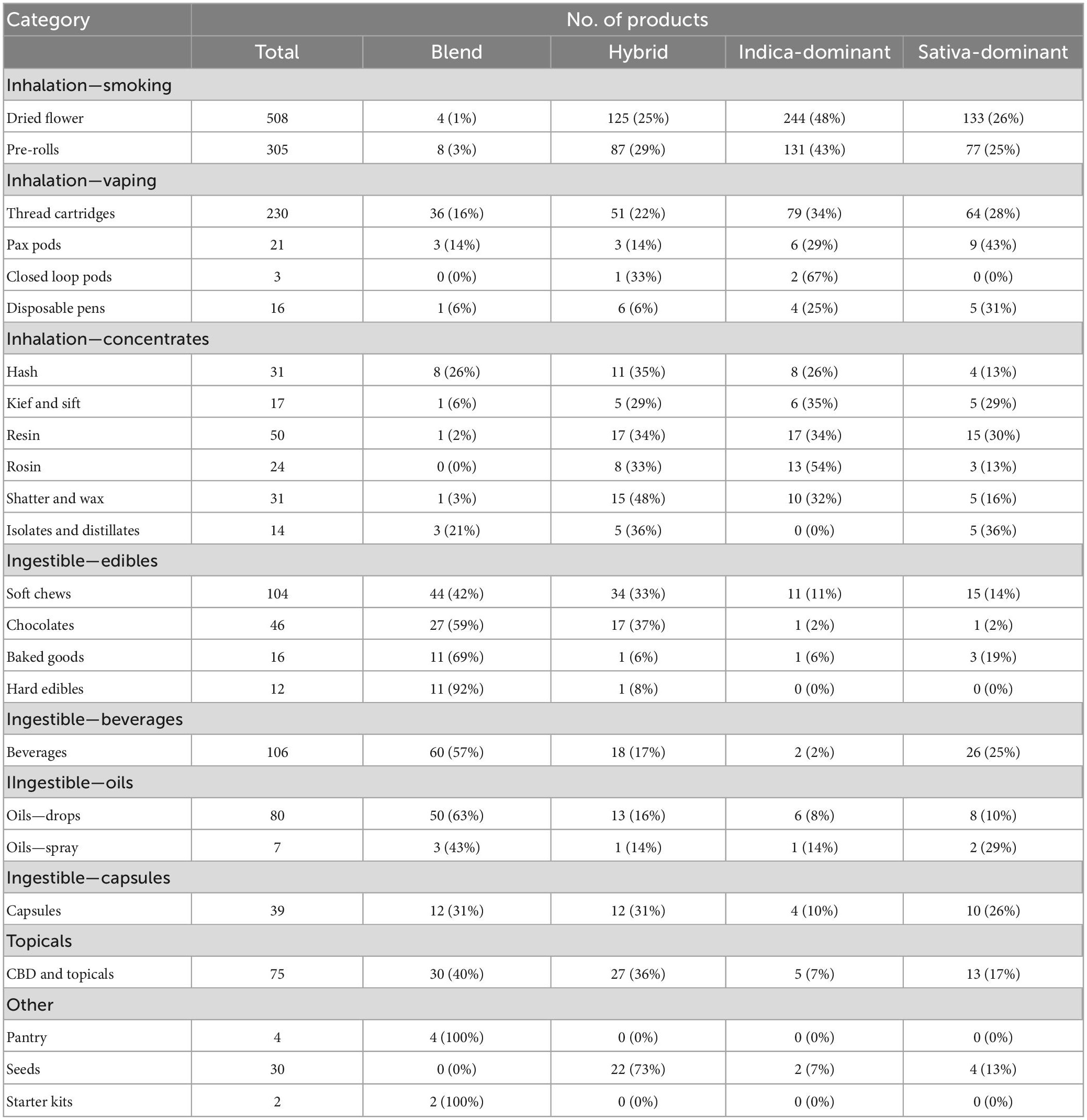

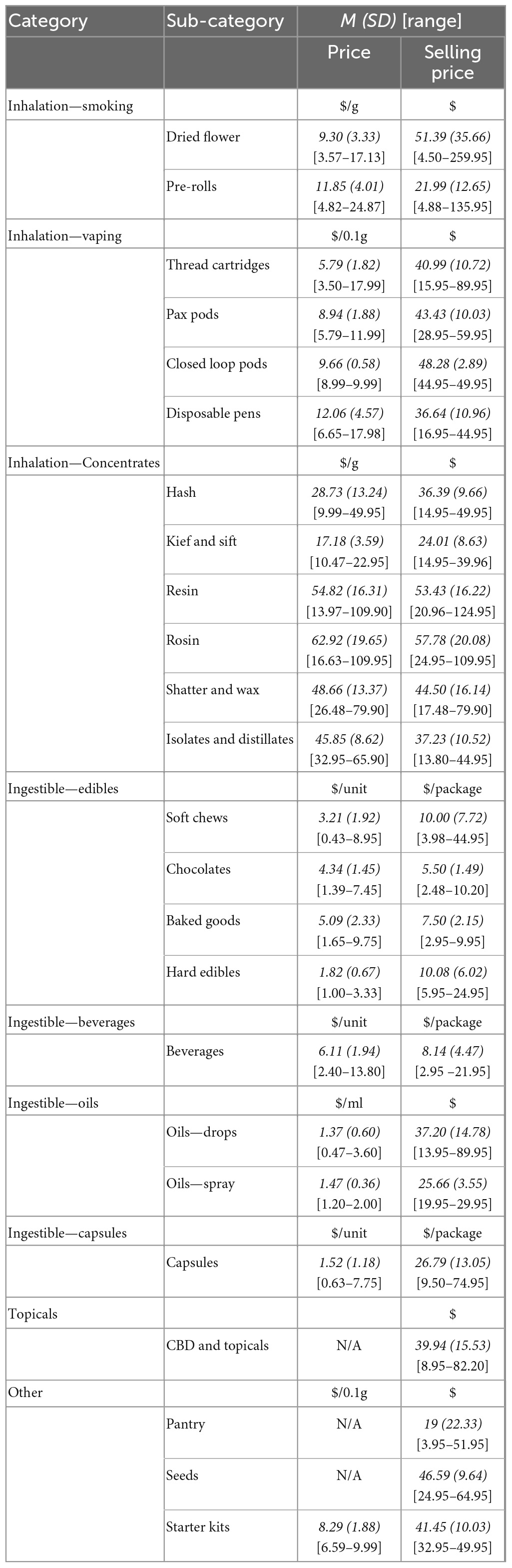

We mapped a total of 1,771 available products by route of administration into inhalation (smoking, vaping, and concentrates: n = 1,250), ingestible (edibles, beverages, oils, and capsules: n = 410), topical (n = 75), and other (pantry, seeds, and starter kits: n = 36) (Tables 1, 2). The sub-categories with the most products under each of the nine categories were: dried flower (n = 508), thread cartridges (n = 230), resin (n = 50), soft chews (n = 104), beverages (n = 106), oils-drops (n = 80), capsules (n = 39), and topicals (n = 75) (Table 2).

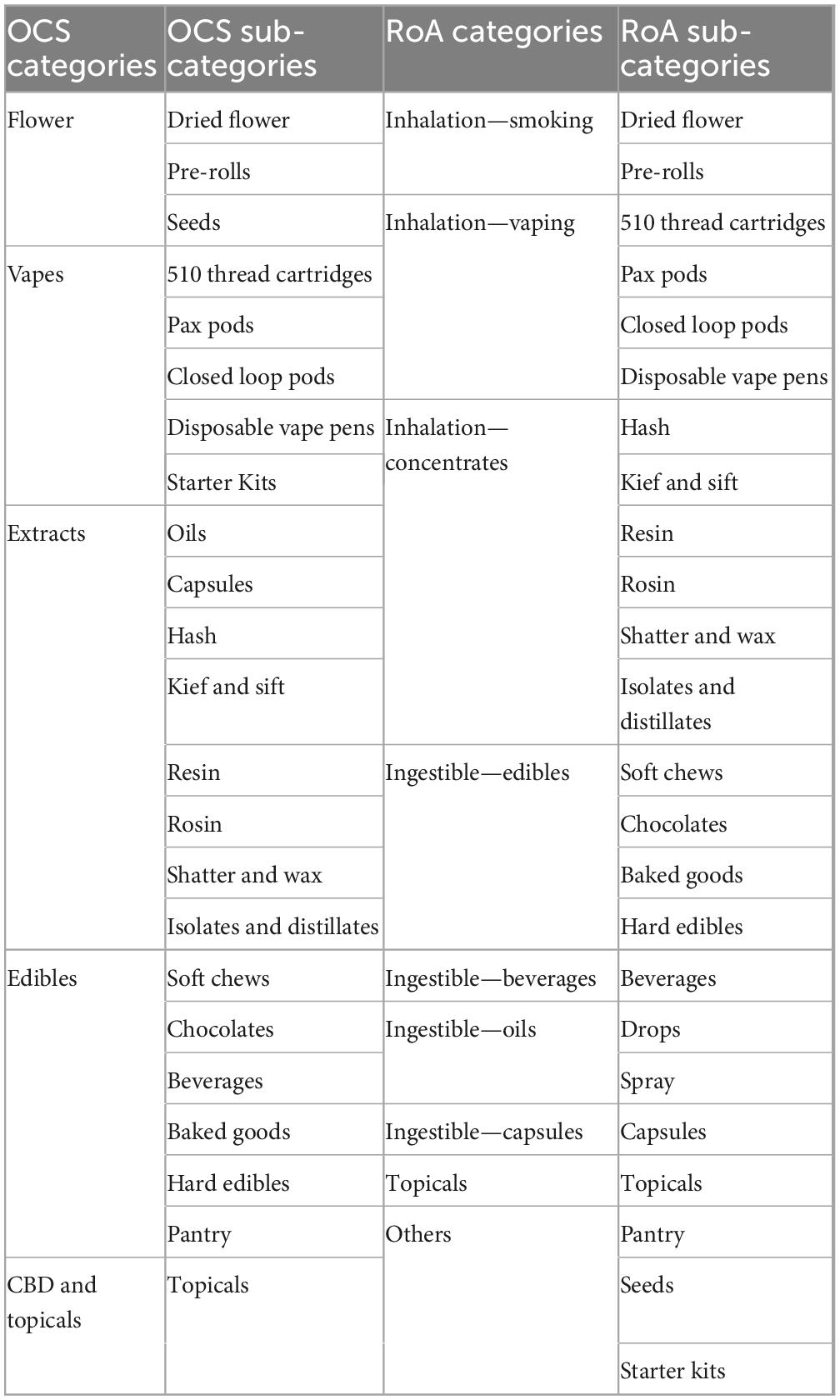

Table 1. Ontario cannabis store (OCS) product categories and sub-categories mapped by route of administration (RoA).

Table 2. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) potency by product type (first quarter of 2022).

THC and CBD potency

A large proportion of inhalation products were categorized as very strong THC products (percent of products with ≥20%/g THC and average THC): dried flower: 94%, 22%/g; thread cartridges: 96%, 74%/g; resin: 100%, 71%/g (Table 2). The trend of high-THC products continued across the inhalation sub-categories, with all sub-categories having over 64% of products being classified as having very strong THC levels and 100% for most concentrates and some vaping products. Apart from isolates and distillates and closed loop pods, all sub-categories had very strong levels of THC in over 88% of products. On the other hand, only 6% of dried flower and 5% of pre-rolls had CBD levels ≥5%/g. Except for isolates & distillates, all sub-categories had lower than 33% of products with very strong CBD levels. Topical products averaged 69 mg/product with a range of 0–500 mg.

No ingestible products exceeded the regulatory limit of THC per package (28). As such, ingestible products saw lower average THC values than inhalation products, including soft chews, beverages, and capsules at 4 mg/unit, and drops at 2%/g (Table 2). The average CBD content in ingestible products corresponded more closely to the THC levels within those products: soft chews: 4 mg/unit; beverages: 6 mg/unit; drops: 2%/g; capsules: 10 mg/unit; and topicals: 280 mg/product.

Plant type

The vast majority of products provided information on the plant type (i.e., blend, hybrid, indica-dominant, sativa-dominant) (Table 3); this information was missing for only 10 products (0.56%).

Relative to ingestible products, inhalation products tended to have a higher percentage of indica-dominant than sativa-dominant products (dried flower: 48% vs. 26%, cartridges: 34% vs. 28%, resin: 34% vs. 30%) while the opposite was true for ingestible products (soft chews: 11% vs. 14%, beverages: 2% vs. 25%, drops: 8% vs. 10%, capsules: 10% vs. 26%, and topicals: 7% vs. 17%).

Ingestible products had more hybrid and blend products available relative to inhalation products, with the majority of the ingestible sub-categories carrying mainly blend or hybrid products. All edibles sub-categories classified over 75% of products as either hybrid or blend, with less than 25% being classified as indica- or sativa-dominant.

Price

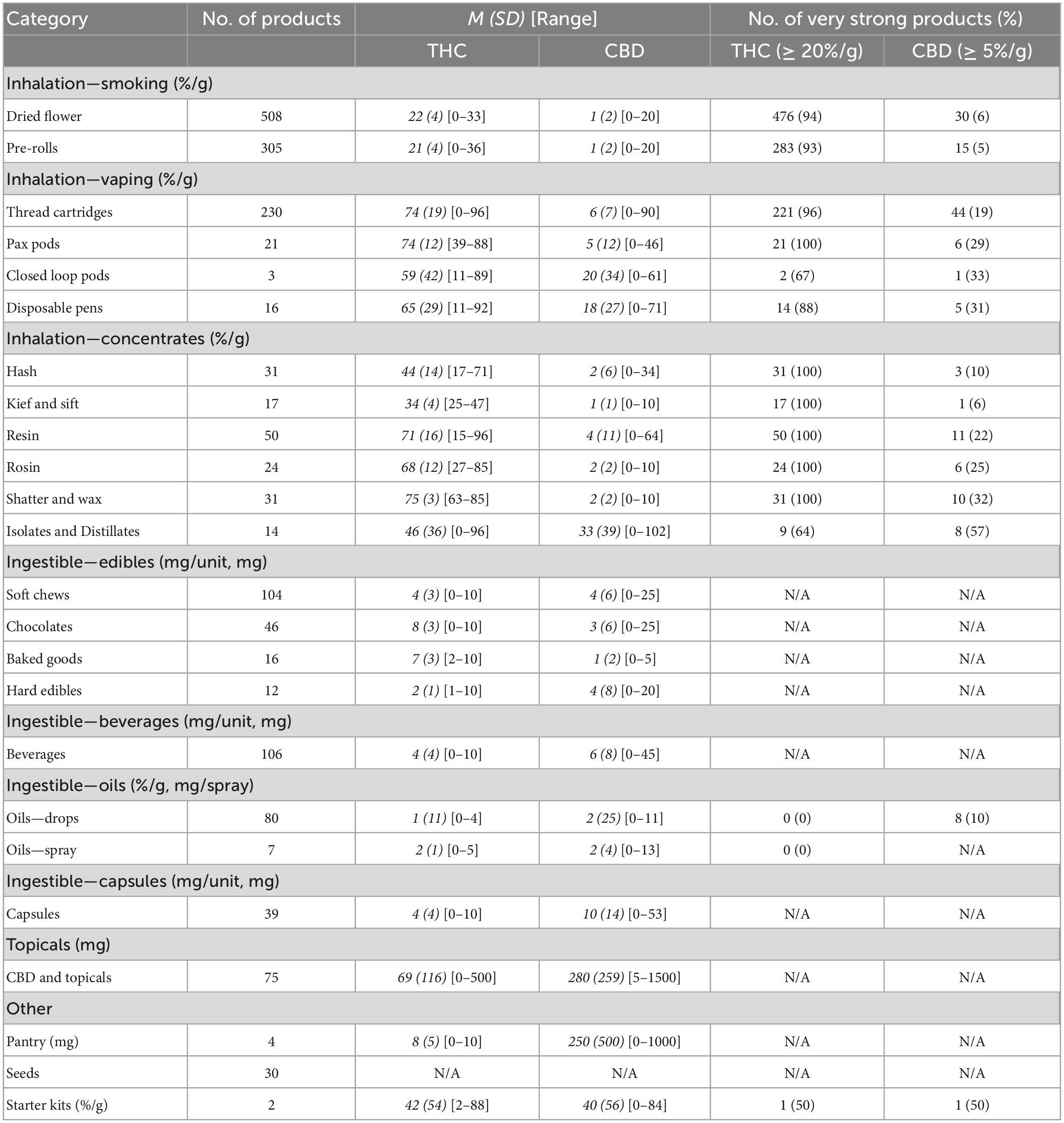

Typically, products were available at a lower selling price when purchasing higher amounts (Table 4). This enables consumers to buy more cannabis for a lower price per gram. For example, if a product’s lowest selling price was $39.95 for 4 g and its highest selling price was $129.95 for 14 g, the lowest price in $/g would be $9.99 for 4 g and $9.28 for 14 g. The consumer has the option to save $0.71/g by buying more cannabis. This was true in the vast majority of cases, but not in all cases.

The average selling price of cannabis products was $51.39 (4.50–259.95) for dried flower, $40.99 (15.95–89.95) for cartridges, $53.43 (20.96–124.95) for resin, $10.00/package (3.98–44.95) for soft chews, $37.20 (13.95–89.95) for drops, $26.79/package (9.50–74.95) for capsules, and $39.94 (8.95–82.20) for topicals.

The average price per unit of cannabis for the most numerous sub-categories was found to be 9.30 $/g (3.57–17.13) for dried flower, 5.79 $/0.1g (3.50–17.99) for cartridges, 54.82 $/g (13.97–109.90) for resin, 3.21 $/unit (0.43–8.95) for soft chews, 1.37 $/ml (0.47–3.60) for drops, and 1.52 $/unit (0.63–7.75) for capsules.

Many products in the flower and pre-roll sub-categories were sold at multiple price points due to the variety of quantities available for purchase. A product in the flower section could be available in multiple sizes, including 1, 3.5, 5, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 28, or 30 g. Similarly, products in the pre-roll section could be available in 0.25, 0.3, 0.32, 0.33, 0.35, 0.4, 0.42, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, or 1 g. For each of these sizes, a different number of pre-rolls may be available, ranging from 1 to 70. Thus, one product could have multiple price points due to being available in a variety of quantities.

Top 10 cannabis products by units sold

In the first quarter of 2022, the top ten cannabis products by units sold in Ontario retail stores were mainly inhalation products (Table 5). Eight of the 10 products fall under the dried flower (n = 5) and pre-roll (n = 3) sub-categories. Two of the top 10 products sold were ingestible and fall under the soft chews sub-category. All inhalation products had “very strong” THC levels with an average of 21%/g. Inhalation products had an average price of 6.49 $/g while ingestible products had an average price of 2.77 $/unit.

Table 5. Characteristics of top 10 cannabis products by units sold in Ontario retail stores (first quarter of 2022).

Discussion

This study describes the Ontario cannabis legal market three years after legalization by cataloging every cannabis product on offer to consumers rather than profiling a market based on a subset or a random selection of products. There was a large variety of products on offer to Ontario consumers with inhalation products being 2.5 times more numerous than ingestible products. The majority of inhalation products had very strong levels of THC. They also had a higher percentage of indica- than sativa-dominant products while ingestible products saw the opposite trend. The average price per unit of dried cannabis was $9.30/g, which is lower than self-reported data collected prior to legalization (29, 30).

Product variety included varying routes of administration, with 46% of items classified as smoking products, 16% as vaping, ∼10% each for edibles and concentrates, and between 2 and 6% each for beverages, oils, capsules, and topicals. The breakdown of product types resembled that for total sales during the same time period, which was 50% for dried flower, 18% pre-rolls, 16% vapes, 5% each of edibles and concentrates, and 2% each of oils and beverages (23). We also found that eight out of the top ten products sold in retail stores were smoking products. In the 3 years post-legalization, consumer preferences for particular types of cannabis products have shifted, although smoking continues to be the most common route of administration (31). From 2017 to 2022, the Canadian Cannabis Survey—a national survey implemented by the Government of Canada to monitor the effects of legalization—reported a decrease in smoking (94–70%) and vaping using vaporizers (14–10%), and an increase in vaping using vape pens (20–31%) and edibles (34–52%) (31, 32). From 2020 to 2022, of those who vaped cannabis, liquid cannabis oil/concentrate use increased (60–74%) and dried flower use decreased (65–49%) (31, 33). This shift in consumer preferences is generally seen as a positive consequence of legalization as lower-risk cannabis use guidelines recommend avoiding routes of administration that involve smoking combusted cannabis products (15). However, the guidelines also caution consumers about the risk of ingesting larger than anticipated doses associated with edibles, which have been linked with increased emergency room visits and hospitalizations, especially with pediatric populations (9, 10).

We observed that the current legal cannabis market for inhalation products is geared toward offering products with high THC potency with a lower availability of balanced THC-CBD or high-CBD options. The average THC potency in the current market is higher than the average potency of 10-13% reported by Health Canada prior to legalization (29), and higher still than the average 6–10% reported in the legal medical market that existed pre-legalization of non-medical cannabis (30). THC potency had already been increasing prior to legalization with a 212% increase from 1995 to 2015 (34). At the time of legalization in late 2018, the average THC potency of legal dried flower across a sample of legal retail stores in Ontario was 16% (31). As of early 2022, we observed that THC levels in dried cannabis on offer to Ontario consumers has an average of 22%. Consumers should be aware that high potency cannabis can have detrimental effects on mental health and addiction outcomes (16, 17, 35–37). Within this context, some have argued for imposing limits on THC in cannabis products, and others propose the use of excise tax based on THC levels to incentivize the use of less potent products (38). It is unknown to what degree THC levels impact consumer product choice; however, in various studies of consumer views on cannabis quality, the potency of cannabis was not mentioned as a marker (31, 39–41). In the latest Canadian Cannabis Survey, strength was ranked last among the factors that influence consumer purchases after price, safe supply, quality, convenience, proximity to retailer, and ability to purchase from a legal source (31). Public outreach around the safer use of cannabis should consider lower-risk cannabis use guidelines; one of the recommendations of which is the choice of lower-potency cannabis products (15). Given the availability of more potent cannabis, future experimental research into their health effects is needed as there is still uncertainty over whether consumers effectively self-titrate THC doses of higher potency products (42).

Despite strict regulations on testing requirements for cannabinoids and contaminants on cannabis products in the Canadian market, we are not aware of peer-reviewed, independent evaluations of the accuracy of product labels (43, 44). However, US studies have reported inconsistencies in cannabinoid labeling on commercial products (45–47). In addition, it has been shown that consumers have difficulties understanding and applying quantitative cannabinoid labeling and additional work should be devoted to improve the labeling of standard doses across routes of administration (48, 49).

The legal market offered a wide variety of products containing different plant types. Inhalation products had higher percentages of indica-dominant products relative to all other plant types, while ingestible products had higher percentages of sativa-dominant products. There were many offers of blend or hybrid options available in every product category. The taxonomical classification of cannabis into indica and sativa are mostly based on marketing considerations as they do not exist in nature due to historical cross-breeding and misuse of nomenclature (50, 51). However, cannabis users report differential subjective experiences between indica- and sativa-dominant products with greater preference for using indica in the evening while reporting feeling “relaxed, sleepy/tired” and sativa during the day while reporting feeling “alert/energized” (52). Overall, offered products appear consistent with consumer preferences for a variety of indica-dominant, sativa-dominant, and hybrid/blend products.

Previous studies of cannabis pricing have typically been done by survey research (24, 25), by selecting a subset of products (e.g., most popular, least, and most expensive) (26), or by calculating the average price of a random sample of products at each pre-determined purchase quantity (27). These studies have typically reported on the average price of dried flower and pre-rolls at set quantities (e.g., the average price at 1, 3.5, 7, 14, and 28 g). In our study, the average price per gram of dried flower for all products on offer was found to be $9.30 and the lowest price was $3.41 per gram. Sales during that period suggest that the majority of consumer purchases were made in the lower price range, with most of the purchases between $3.00 and 6.50 per gram making up 48% of in-person purchases and 63% of online purchases (23). Our calculations suggest that spending more money on larger quantities would provide consumers with a “better deal,” with the average selling price of dried flower products being $51.39. In line with 2022 self-reported data, consumers who had used recreational cannabis within the last 30 days spent an average of $65 ($46–$86) from legal sources per month, an increase from $55 in 2021 (31, 39). Participants who used cannabis for medical purposes spent an average of $75 in the past 30 days (31). For consumers that tend to spend above $50 a month on cannabis, buying dried flower products “in bulk” seems to be a reasonable approach for reducing the cost of cannabis per gram.

The average dried flower prices was lower than those reported in studies of the retail cannabis market in Canada pre-legalization and at the time of legalization (29, 30). Prior to legalization, the average self-reported price-per-gram of cannabis was $9.56, but this varied depending on the quantity purchased (24). In comparison to self-reported data collected several months post-legalization, the average price of legal dried flower has decreased slightly: 9.82 $/g in late 2018 versus 9.30 $/g in early 2022 (27). In comparison to self-reported legal cannabis prices in Canada from 2019, regardless of quantity, the average price of dried flower in 2022 is also lower, ranging from $23.16/1g to $9.95/3.5 g and $9.95/27.9 g in 2019 (25). Additionally, it was found that the price of dried flower from legal sources decreased post-legalization (25), consistent with our findings.

In a recent qualitative study from Canada, participants spoke of the benefits associated with the illegal cannabis market, including lower prices, incentives, discounts, and loyalties (41). The majority of participants in that study noted that legal cannabis is more expensive than illegal cannabis and that price was of highest importance when making purchasing decisions (41). This is in agreement with the Canadian Cannabis Survey in which 30% of participants in 2022 ranked price as the number one factor that influences purchases (31, 39). Users on social media platforms thought legal products were expensive in comparison to illegal cannabis and have also expressed concerns with difficulties with supply shortages in the legal market (53). Cannabis users have indicated that price, product quality, store location, and the inconvenience of purchasing from legal sources were key reasons for buying cannabis from the illicit market (54). However, if the average price per gram and average selling prices of the legal market continue to follow downward trends, then more Canadians may become motivated to purchase from legal sources (54). Recent Canadian research states that the divergence between legal and illegal cannabis markets is narrowing (25) and the legal share of the overall cannabis market is estimated to be 57% (23).

Conclusion

The Ontario legal market has a wide variety of cannabis products on offer to consumers. There is a wide array of products available for various consumer preferences in plant type, with numerous indica-dominant, sativa-dominant, and hybrid/blend options on offer. In line with lower-risk cannabis use guidelines (15), consumers would benefit from having access to more lower-potency, mixed THC-CBD ratios, and CBD-dominant products. Three years post-legalization, Canadian cannabis consumers have favorable perceptions of legal cannabis products in comparison to illegal products, apart from price (40).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SR and PD conceived, designed, and directed the study. FT extracted the data with support from YL. FT analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SR carried out substantial edits to the initial draft. All authors reviewed various drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

SR was supported by an Ontario HIV Treatment Network Innovator Award.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cannabis Act. Canada Justice Laws Website. (2018). Available online at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-24.5/page-1.html (accessed September 9, 2022).

2. Government of Canada. Regulations Amending the Cannabis Regulations (new classes of Cannabis): SOR/2019-206. (2019). Available online at: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2019/2019-06-26/html/sor-dors206-eng.html (accessed September 9, 2022).

3. Government of Canada. Health Canada. Government of Canada Launches Legislative Review of the Cannabis Act. (2022). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2022/09/government-of-canada-launches-legislative-review-of-the-cannabis-act.html (accessed September 9, 2022).

4. Wadsworth E. The Effect of Price and Retail Availability on the use of Illegal and Legal Non-Medical Cannabis in Canada and the United States. Ph D. thesis. Waterloo, ON: University of Waterloo (2021).

5. Goodman S, Wadsworth E, Leos-Toro C, Hammond D. Prevalence and forms of cannabis use in legal vs. illegal recreational cannabis markets. Int J Drug Policy. (2020) 76:102658. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102658

6. Myran D, Imtiaz S, Konikoff L, Douglas L, Elton-Marshall T. Changes in health harms due to cannabis following legalisation of non-medical cannabis in Canada in context of cannabis commercialisation: a scoping review. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2022) 42:277–98. doi: 10.1111/dar.13546

7. Rubin-Kahana D, Crépault J, Matheson J, Le Foll B. The impact of cannabis legalization for recreational purposes on youth: a narrative review of the Canadian experience. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:984485. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.984485.

8. Hall W, Stjepanoviæ D, Leung J. Cannabis Legalisation in Canada: A Brief History, Policy Rationale, Implementation, and Evidence on Early Impacts. Brisbane, QL: The University of Queensland (2022). doi: 10.14264/a494332

9. Myran D, Pugliese M, Tanuseputro P, Cantor N, Rhodes E, Taljaard M. The association between recreational cannabis legalization, commercialization and cannabis-attributable emergency department visits in Ontario, Canada: an interrupted time-series analysis. Addict Abingdon Engl. (2022) 117:1952–60. doi: 10.1111/add.15834

10. Myran D, Tanuseputro P, Auger N, Konikoff L, Talarico R, Finkelstein Y. Edible cannabis legalization and unintentional poisonings in children. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:757–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2207661

11. Government of Canada. Police-Reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2019. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (2020).

12. Government of Canada. Police-Reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2020. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (2021).

13. Government of Canada. Police-Reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2021. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (2022).

14. Pierre J. Risks of increasingly potent cannabis: the joint effects of potency and frequency. Curr Psychiatry. (2017) 16:15–20.

15. Fischer B, Robinson T, Bullen C, Curran V, Jutras-Aswad D, Medina-Mora M, et al. Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: a comprehensive evidence and recommendations update. Int J Drug Policy. (2022) 99:103381. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103381

16. Petrilli K, Ofori S, Hines L, Taylor G, Adams S, Freeman T. Association of cannabis potency with mental ill health and addiction: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. (2022) 9:736–50. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00161-4

17. Matheson J, Le Foll B. Cannabis legalization and acute harm from high potency cannabis products: a narrative review and recommendations for public health. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:591979. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591979

18. Callaghan R, Sanches M, Benny C, Stockwell T, Sherk A, Kish S. Who consumes most of the cannabis in Canada? Profiles of cannabis consumption by quantity. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2019) 205:107587. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107587

19. Armstrong M. Legal cannabis market shares during Canada’s first year of recreational legalisation. Int J Drug Policy. (2021) 88:103028. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103028

20. Myran D, Staykov E, Cantor N, Taljaard M, Quach B, Hawken S, et al. How has access to legal cannabis changed over time? An analysis of the cannabis retail market in Canada 2?years following the legalisation of recreational cannabis. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2021) 41:377–85. doi: 10.1111/dar.13351

21. Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario. Status of Current Cannabis Retail Store Applications. Toronto, ON: Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (2022).

23. Ontario Cannabis Store. Ontario Cannabis Store: A Quarterly Review. Toronto, ON: Ontario Cannabis Store (2022).

24. Wadsworth E, Driezen P, Goodman S, Hammond D. Differences in self-reported cannabis prices across purchase source and quantity purchased among Canadians. Addict Res Theory. (2019) 28:474–83. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2019.1689961

25. Wadsworth E, Driezen P, Pacula R, Hammond D. Cannabis flower prices and transitions to legal sources after legalization in Canada, 2019–2020. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2022) 231:109262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109262

26. Mahamad S, Hammond D. Retail price and availability of illicit cannabis in Canada. Addict Behav. (2019) 90:402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.001

27. Mahamad S, Wadsworth E, Rynard V, Goodman S, Hammond D. Availability, retail price and potency of legal and illegal cannabis in Canada after recreational cannabis legalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2020) 39:337–46. doi: 10.1111/dar.13069

28. Government of Canada. Final Regulations: Edible Cannabis, Cannabis Extracts, Cannabis Topicals. (2019). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/resources/final-regulations-edible-cannabis-extracts-topical-eng.pdf (accessed September 9, 2022).

29. McGilveray I. Pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids. Pain Res Manag. (2005) 10:15A–22A. doi: 10.1155/2005/242516

30. Lucas P. Regulating compassion: an overview of Canada’s federal medical cannabis policy and practice. Harm Reduct J. (2008) 5:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-5

31. Health Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2022: Summary. (2022). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2022-summary.html (accessed January 6, 2023).

32. Health Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2018: Summary. (2018). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-cannabis-survey-2018-summary.html (accessed October 30, 2022).

33. Health Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2020: Summary. (2020). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2020-summary.html (accessed October 30, 2022).

34. Stuyt E. The problem with the current high potency THC marijuana from the perspective of an addiction psychiatrist. Mo Med. (2018) 115:482–6.

35. Murray R, Quigley H, Quattrone D, Englund A, Di Forti M. Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: increasing risk for psychosis. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:195–204. doi: 10.1002/wps.20341

36. Di Forti M, Quattrone D, Freeman T, Tripoli G, Gayer-Anderson C, Quigley H, et al. The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): a multicentre case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6:427–36. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30048-3

37. Hines L, Freeman T, Gage S, Zammit S, Hickman M, Cannon M, et al. Association of high-potency cannabis use with mental health and substance use in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:1044–51. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1035

38. Transform Drug Policy Foundation. How to Regulate Cannabis: A Practical Guide. 3rd ed. Bristol: Transform Drug Policy Foundation (2022).

39. Health Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2021: Summary. Government of Canada. (2021). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2021-summary.html (accessed October 30, 2022).

40. Wadsworth E, Fataar F, Goodman S, Smith D, Renard J, Gabrys R, et al. Consumer perceptions of legal cannabis products in Canada, 2019–2021: a repeat cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:2048. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14492-z

41. Donnan J, Shogan O, Bishop L, Najafizada M. Drivers of purchase decisions for cannabis products among consumers in a legalized market: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:368. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12399-9

42. Leung J, Stjepanoviæ D, Dawson D, Hall W. Do cannabis users reduce their THC dosages when using more potent cannabis products? A review. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:630602. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.630602

43. Government of Canada. Guidance Document: Good Production Practices Guide for Cannabis. (2019). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/cannabis-regulations-licensed-producers/good-production-practices-guide/guidance-document.html#a5.3 (accessed January 11, 2023).

44. Botelho D, Boudreau A, Rackov A, Rehman A, Phillips B, Hay C, et al. Analysis of Illicit and Legal Cannabis Products for a Suite of Chemical and Microbial Contaminants: A Comparative Study. Fredericton, NB: New Brunswick Research and Productivity Council (RPC) (2021).

45. Gurley B, Murphy T, Gul W, Walker L, ElSohly M. Content versus label claims in cannabidiol (CBD)-containing products obtained from commercial outlets in the state of Mississippi. J Diet Suppl. (2020) 17:599–607. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2020.1766634

46. Mazzetti C, Ferri E, Pozzi M, Labra M. Quantification of the content of cannabidiol in commercially available e-liquids and studies on their thermal and photo-stability. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:3697.

47. Miller O, Elder E, Jones K, Gidal B. Analysis of cannabidiol (CBD) and THC in nonprescription consumer products: implications for patients and practitioners. Epilepsy Behav. (2022) 127:108514. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108514

48. Leos-Toro C, Fong G, Meyer S, Hammond D. Cannabis labelling and consumer understanding of THC levels and serving sizes. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 208:107843.

49. Hammond D. Communicating THC levels and “dose” to consumers: implications for product labelling and packaging of cannabis products in regulated markets. Int J Drug Policy. (2021) 91:102509. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.004

50. Micalizzi G, Vento F, Alibrando F, Donnarumma D, Dugo P, Mondello L. Cannabis sativa l.: a comprehensive review on the analytical methodologies for cannabinoids and terpenes characterization. J Chromatogr A. (2021) 1637:461864. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461864

51. Jin D, Henry P, Shan J, Chen J. Classification of cannabis strains in the Canadian market with discriminant analysis of principal components using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0253387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253387

52. Sholler D, Moran M, Dolan S, Borodovsky J, Alonso F, Vandrey R, et al. Use patterns, beliefs, experiences, and behavioral economic demand of indica and sativa Cannabis: a cross-sectional survey of cannabis users. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. (2022) 30:575–83. doi: 10.1037/pha0000462

53. Aversa J, Jacobson J, Hernandez T, Cleave E, Macdonald M, Dizonno S. The social media response to the rollout of legalized cannabis retail in Ontario, Canada. J Retail Consum Serv. (2021) 61:102580. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102580

Keywords: cannabis legalization, legal market, adult consumers, cannabis products, cannabis prices, cannabis potency, THC, CBD

Citation: Tassone F, Di Ciano P, Liu Y and Rueda S (2023) On offer to Ontario consumers three years after legalization: A profile of cannabis products, cannabinoid content, plant type, and prices. Front. Psychiatry 14:1111330. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1111330

Received: 29 November 2022; Accepted: 31 January 2023;

Published: 16 February 2023.

Edited by:

Yasser Khazaal, Université de Lausanne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Brian J. Piper, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, United StatesEzgi Aytaç, Konya Food & Agriculture University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Tassone, Di Ciano, Liu and Rueda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sergio Rueda,  cnVlZGFnZW50b0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

cnVlZGFnZW50b0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Felicia Tassone

Felicia Tassone Patricia Di Ciano

Patricia Di Ciano Yuxin Liu

Yuxin Liu Sergio Rueda

Sergio Rueda