Abstract

Background:

Maternal infection or inflammatory stimulation during pregnancy can disrupt fetal brain development through immune activation, increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring, including schizophrenia. Using a maternal immune activation (MIA) model induced by polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)) during pregnancy, this study employed multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—including T2 structural imaging, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), arterial spin labeling (ASL), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)—to comprehensively assess offspring brain alterations across structure, white matter integrity, cerebral perfusion, and metabolite levels.

Methods:

Pregnant Wistar rats were randomly assigned to a Poly(I:C) model group or a saline control group. Adult male offspring underwent T2 structural imaging, DTI, ASL, and MRS. Voxel-based morphometry of T2 images evaluated structural changes; DTI quantified fractional anisotropy (FA) and diffusivity indices (mean diffusivity [MD], axial diffusivity [AD], radial diffusivity [RD]); ASL measured cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the prefrontal cortex and striatum; and MRS assessed metabolite levels in the prefrontal cortex. Group differences were analyzed (p<0.05).

Results:

Poly(I:C) offspring exhibited significant gray matter density reductions in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, cingulate cortex, and sensorimotor cortex, whereas the right posterior parietal cortex showed increased density and the left third ventricle was enlarged. DTI revealed elevated MD and RD in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, along with increased RD in the genu of the corpus callosum, indicating white matter microstructural damage and abnormalities in myelination. ASL demonstrated significantly increased CBF in the prefrontal cortex and striatum, reflecting abnormal regional perfusion. MRS showed a significant reduction in NAA/Cr in the prefrontal cortex, suggesting impaired neuronal function.

Conclusion:

Offspring rats exposed to maternal Poly(I:C) during pregnancy exhibited abnormalities across multiple domains, including brain structure, white matter microstructure, cerebral perfusion, and metabolism. This study provides additional evidence that maternal inflammation during pregnancy can interfere with offspring brain development and impair neurological function.

1 Introduction

In recent years, growing evidence from both epidemiological and animal studies has indicated that maternal immune activation (MIA) (1) during pregnancy—triggered by infection or inflammation—may disrupt fetal brain development and substantially increase the risk of schizophrenia (SZ) and other neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring (2). Researchers often use the Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C))-induced MIA model as a neurodevelopmental model for research on processes relevant to schizophrenia (3–5). The offspring of these dams display behavioral alterations relevant to the schizophrenia phenotype, as they relate to underlying cognitive and sensorimotor processes implicated in the disorder, including cognitive impairment (6), social deficits (7), and prepulse inhibition impairments (8). In addition, MIA has also been widely modeled using bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and the changes it exhibits are similar to those observed when using Poly(I:C) (9–12). The behavioral, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological alterations observed in these models across rats and mice suggest that the MIA model holds significant value for investigating neurodevelopmental mechanisms relevant to schizophrenia. To further elucidate disease pathophysiology, numerous studies have examined structural alterations in the brains of schizophrenia model rats.

In neuroimaging research, only a limited number of studies have employed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate structural brain alterations in Poly(I:C) rats. For example, Piontkewitz et al., using 7T MRI, reported significant volume reductions in several brain regions, including the hippocampus, striatum, and prefrontal cortex, as well as enlargement of the lateral ventricles in Poly(I:C) offspring (13). Similarly, Casquero-Veiga et al. observed volumetric alterations in Poly(I:C)-induced MIA female offspring, including increased gray matter volume in the hippocampus, pituitary gland, and cingulate cortex, reduced gray matter volume in certain thalamic nuclei, cerebellum, and brainstem, alongside enlargement of the lateral ventricles and fourth ventricle (14). Winter et al. (15) utilized ex vivo 7T MRI to demonstrate that adult male Wistar rats with Poly(I:C)-treated offspring had significantly enlarged lateral ventricles, which could be reliably detected by automated segmentation. Romero-Miguel et al. (16) reported ventricular enlargement and hippocampal reduction in the Poly(I:C) model. Liu et al. (17) used 9.4T MRI combined with DTI and MRE to find that Poly(I:C) offspring had enlarged ventricles, abnormally increased white matter diffusion markers (MD, AD, RD), and impaired cortical stiffness development from 4 weeks after birth. Although these studies provide valuable insights, and several research groups have already applied multimodal and whole-brain approaches in the MIA model, many MRI investigations still rely on single imaging modalities or focus on specific brain regions, thereby limiting fully integrative analyses across multiple modalities. This limitation continues to hinder a comprehensive understanding of brain alterations in the Poly(I:C) model.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a valuable tool for assessing the microstructural integrity of white matter (18, 19). Previous research has demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia frequently exhibit abnormalities in white matter tracts, including reduced anisotropy (20, 21). In Poly(I:C) rats, Liu et al. reported marked alterations in white matter diffusivity (17). Specifically, they found that with increasing age, Poly(I:C) model rats showed progressive elevations in mean diffusivity (MD) and radial diffusivity (RD) within the corpus callosum, internal capsule, and external capsule, suggesting abnormal myelination or altered cellular density. Di Biase et al. (22) found that male rats exposed to Poly(I:C) prenatally exhibited increased levels of extracellular free water in the corpus callosum and striatum in adulthood, suggesting that extracellular edema and inflammatory responses are involved in white matter changes. Wood et al. (23) did not observe significant differences in DTI during the early developmental stage (P21), suggesting that white matter abnormalities may gradually appear as development progresses. Missault et al. (24), using functional and structural imaging, found that although DTI indices did not change significantly, the default mode network sample region showed excessive synchronization, indicating that functional connectivity abnormalities may precede structural damage. These alterations are consistent with the white matter connectivity deficits commonly reported in schizophrenia, although further longitudinal and multimodal investigations are needed for confirmation.

With respect to functional and perfusion imaging, arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI provides a noninvasive method for assessing regional cerebral blood flow (25). Although extensive ASL studies have not yet been conducted in the MIA model, early prospective work has suggested that MIA can lead to abnormal cerebral perfusion. For example, an earlier study reported alterations in cerebral perfusion in a Poly(I:C)-treated rat model: Drazanova et al. (26) found that male rats exposed to prenatal Poly(I:C) exhibited hyperperfusion in cerebral circulation regions such as the circle of Willis, hippocampus, and cortical areas. Additionally, Rasile et al. (27) found that Poly(I:C) treatment led to impaired blood-brain barrier function in offspring rats. Thus, ASL offers valuable insights in MIA models for detecting regional alterations in CBF during development or adulthood that may correlate with long-term cognitive, behavioral, or neurometabolic impairments.

From a neurochemical perspective, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) enables quantification of neurotransmitters and metabolites in the brain (28). Previous studies have reported a significant positive correlation between N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels in the hippocampus of healthy rats and their performance in hippocampus-dependent spatial memory tasks. Conversely, reduced NAA levels are frequently observed in models of Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Psychiatric Disorders (29). A recent study employing MRS technology revealed that adolescent stress induced a significant decrease in NAA+NAAG levels in the dorsal striatum of MIA (LPS-induced) offspring (30). However, only a few MRS studies have examined the offspring of Poly(I:C)-exposed dams, and it remains unclear whether this model exhibits comparable neurochemical abnormalities.

In summary, while multimodal and whole-brain imaging studies of the MIA model are increasingly reported, many MRI studies of MIA rat models still focus on a single imaging modality or restricted brain regions, and relatively fewer have integrated multiple MRI modalities within the same cohort in vivo. To address this gap, the present study employs a multimodal MRI approach to assess brain alterations in the Poly(I:C) model. Using a cohort of Wistar rat offspring prenatally exposed to Poly(I:C), we conducted T2-weighted structural imaging, DTI, ASL, and MRS within the same group, thereby enabling an integrated assessment of changes in brain structure, white matter microstructure, regional perfusion, and neurochemical composition.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and drugs

All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (Approval Number: BUCM-2024040107-2017). Twelve pregnant female Wistar rats were used in this study. On gestational day 6 (GD6), the animals were purchased from Beijing Speifu Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All dams were consistent in gestational age, source, and body weight range. They were housed in the SPF-grade Laboratory Animal Center of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine under controlled environmental conditions: a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 50–60%, and a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08:00, off at 20:00). Food and water were provided ad libitum, and the housing environment was maintained in a quiet setting. Throughout the experimental process, efforts were made to minimize stress, and all abnormal behaviors and deaths were carefully recorded.

Some studies have indicated that LPS often leads to premature birth (31–33), while in this study, Poly(I:C) was used as the model agent. Before administration, the dry powder was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride injection solution preheated to 50 °C, prepared as a sterile stock solution at a concentration of 5 mg/mL, stored in a protected environment, and thoroughly mixed by vortexing.

2.2 Model preparation

2.2.1 Establishment of the MIA model

The Poly(I:C)-induced MIA model was employed as a neurodevelopmental model for studying processes relevant to schizophrenia. After a three-day adjustment period, on gestational GD9 (Critical Periods of Embryonic Development (34)), pregnant rats were randomly assigned to two groups: One group received an intravenous tail vein injection of Poly(I:C) dissolved in 0.9% saline (5 mg/mL) at a dose of 10 mg/kg, whereas the control group received an equivalent volume of saline. The female mice were weighed immediately before injection and again 7 days later. The day of delivery was designated as postnatal day 0 (PD0). Following the method of Fang et al. (35), blood was collected from the tail veins of all female mice approximately 3 hours post-injection. Serum was obtained by centrifuging at 1000×g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Serum samples were stored at -20 °C until they were analyzed. Serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18, and TNF-α) were measured using an ELISA kit (Jiangsu Jingmei) to validate maternal immune activation. Detailed data are available in the Supplementary Material.

2.2.2 Grouping

Offspring were weaned on PD21 and housed separately by sex. Male offspring were selected for subsequent experiments. Each cage contained 4–5 rats. To ensure data independence, rats within the same cage were sourced from different litters. Between PD101 and PD110, a series of behavioral tests was performed to evaluate the offspring, thereby confirming the successful establishment of the model. The specific details and procedures for behavioral testing have been published in our previous work (36). We conducted a series of behavioral tests during PD101–110 (proceed in order from low stress to high stress), including the open field test (PD101), Y-maze (PD103), Elevated Plus Maze (PD105), and Pre-pulse Inhibition (PD107-PD108). All behavioral experiments were conducted between 9:00 AM and 6:00 PM, with a one-day interval between each test (Detailed statistics can be found in the Supplementary Materials.). After completing all behavioral tests, the rats were transferred to the NMR experimental animal room. Following a 3-day acclimation period, 9 animals were randomly selected from each group—MIA offspring and saline offspring (Control group, CTL)—using a random number table method for MRI testing.

2.3 Data acquisition

All MRI experiments were performed on postnatal day 111 (PD111) using a 7.0 T small-animal MRI scanner (Bruker BioSpin, Germany) at the Small Animal In Vivo Imaging Laboratory of Capital Medical University. Rats were initially anesthetized in an induction chamber with 5% isoflurane in 95% oxygen, and anesthesia was subsequently maintained at 2% isoflurane in 98% oxygen delivered via a nose cone. Animals were positioned prone on a custom-made animal bed with the head fixed at the isocenter of the radiofrequency coil. Throughout the scanning session, respiration rate was continuously monitored and maintained at 40–60 breaths/min using a small-animal physiological monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY, USA), and rectal temperature was kept at 36.5–37.5 °C using a warm air heating system.

2.3.1 MRI data acquisition and VBM analysis

High-resolution T2-weighted structural images were acquired using a 2D multi-slice turbo spin-echo sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 4200 ms, echo time (TE) = 36 ms, flip angle = 180°, field of view (FOV) = 33 × 33 mm², matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 0.7 mm, no interslice gap, 35 contiguous coronal slices. These images served as an anatomical reference for voxel placement in spectroscopy and region-of-interest (ROI) analyses.

Voxel-based morphometry was conducted on 3D T2-weighted MPRAGE images processed with the spmAnimalIHEP4.1 toolbox (based on SPM12, MATLAB R2014a). Preprocessing steps included (1) spatial registration to a rat brain template using the DARTEL algorithm, (2) tissue segmentation to generate gray matter probability maps, (3) modulation to preserve local volume information, and (4) spatial smoothing with an 8-mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. Between-group differences in gray matter density were assessed using voxel-wise two-sample t-tests, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (cluster-level family-wise error corrected). Significant clusters were reported with MNI coordinates, cluster extent (Ke), and peak T-value. It should be noted that VBM provides measures of relative gray matter density rather than absolute regional volumes.

2.3.2 DTI sequence

Diffusion tensor imaging was performed using a single-shot spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence in 30 non-collinear directions with the following parameters: TR = 3750 ms, TE = 23 ms, FOV = 35 × 35 mm², matrix = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, 1.0 mm interslice gap, 12 coronal slices, b-values = 0 and 1000 s/mm², NEX = 1, total scan time is about 17 min 30 s. Automatic higher-order shimming was applied prior to each acquisition. Fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) maps were generated using ParaVision 5.1 software (Bruker). ROIs were manually delineated on the color-coded FA maps with reference to the Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlas (7th edition) in the following regions: hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA3, dentate gyrus), genu of the corpus callosum, and medial prefrontal cortex. Each ROI was measured three times, and the mean value was used for statistical analysis.

2.3.3 ASL imaging

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) was quantified using the flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique with the following parameters: TR = 18,000 ms, TE = 25 ms, FOV = 33 × 33 mm², matrix = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 2.0 mm, triple inversion recovery time = 22 ms. CBF maps were reconstructed in ParaVision 5.1. ROI-based CBF values were extracted from the prefrontal cortex and striatum using manual segmentation guided by the Paxinos and Watson atlas, with each region measured three times and averaged.

2.3.4 MRS acquisition

Single-voxel ¹H-MRS was performed in the bilateral prefrontal cortex using the point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence after acquisition of multiplanar T2-weighted scout images (TR = 4200 ms, TE = 36 ms, matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 0.7 mm, FOV = 33 × 33 mm²). A voxel of 3.0 × 3.0 × 3.0 mm³ was positioned over the bilateral PFC based on anatomical landmarks. Automated shimming and water suppression were performed prior to spectral acquisition. Spectra were acquired with TR = 2500 ms, TE = 136 ms, spectral width = 5000 Hz, and 256 averages. Post-processing was conducted in TopSpin 2.0 software, including Fourier transformation, baseline correction, and peak integration using the residual water signal at 4.7 ppm as chemical shift reference. Metabolite peaks of interest included N-acetylaspartate (NAA, 2.02 ppm), total creatine (Cr, 3.05 ppm), choline-containing compounds (Cho, 3.20 ppm), glutamate (Glu, 3.60–3.80 ppm), and myo-inositol (mI, 3.56 ppm). All metabolite concentrations were expressed as ratios relative to creatine.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Experimental data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 software, and results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk method, and homogeneity of variance was tested using the Levene method. For data conforming to a normal distribution with homogeneous variances, an independent samples t-test was used. For data with unequal variances, a corrected t-test (Welch’s t-test) was applied. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. In addition, to avoid false positives in multiple experiments, we used the Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR) correction method to adjust the p for multiple comparisons. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 VBM analysis

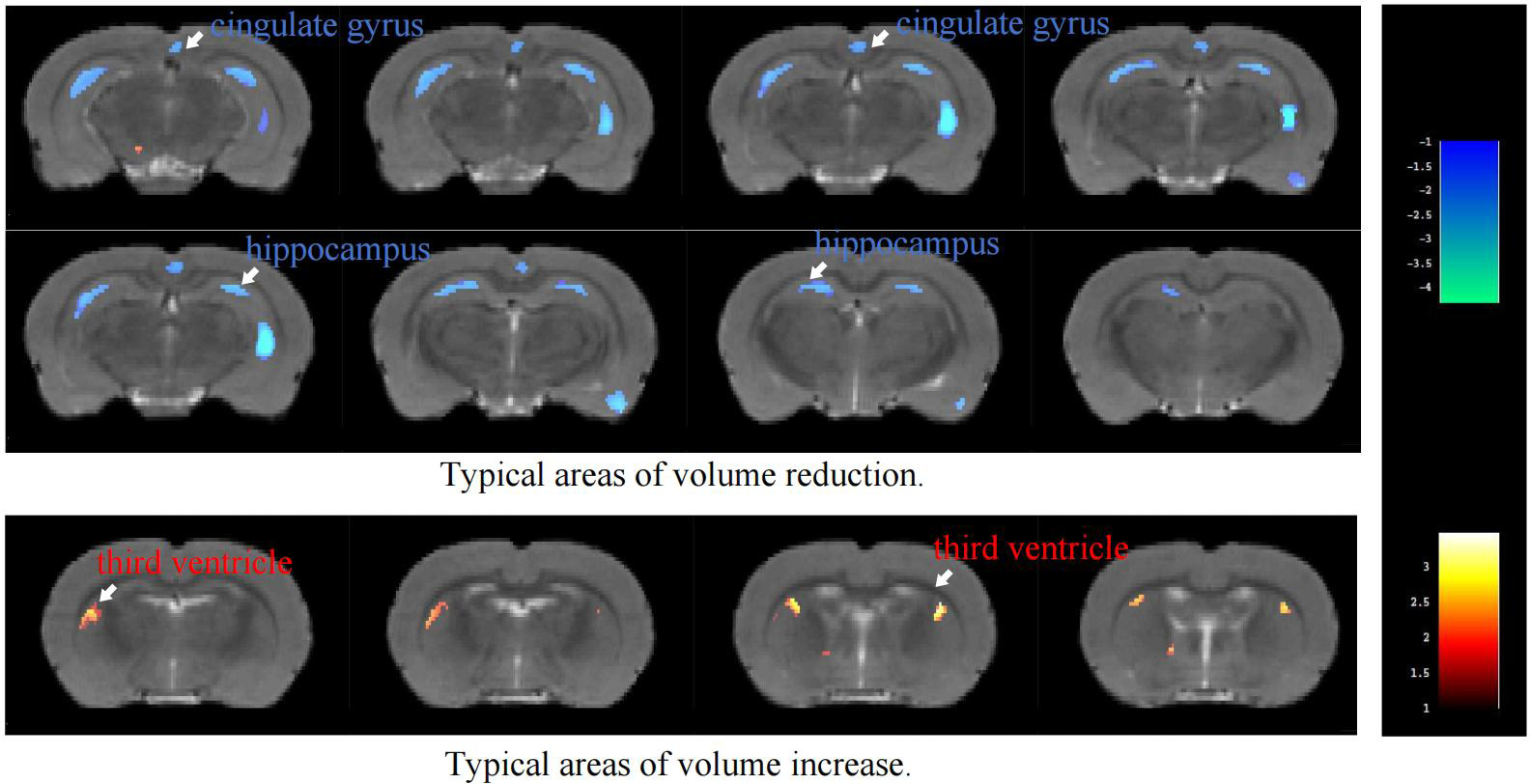

VBM analysis of T2-weighted imaging data revealed significant density alterations in multiple brain regions in the MIA group compared with the CTL group, as illustrated in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1. Compared with the CTL group, the MIA group showed pronounced density reductions (p<0.05) in several regions, including the bilateral striatum, corpus callosum, visual cortex, hippocampus, auditory cortex, cingulate cortex, sensory and motor cortices, as well as both prefrontal cortices. In contrast, among regions with increased density, significant changes were detected only in the right posterior parietal cortex and the left third ventricle.

Figure 1

Color-coded VBM overlay images are displayed on the MRI reference map, with warm colors indicating increases and cool colors indicating decreases.

Table 1

| Group | Cluster | ROI | Cluster size | MaxT | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIA vs CTL (Decrease) | 1 | Left Striatum | 59 | 3.586 | -2.8177 | 5.9317 | -0.3579 |

| Right Striatum | 2.3839 | 2.0158 | 9.0338 | -10.9179 | |||

| 2 | Right Corpus Callosum | 30 | 2.0989 | 5.423 | 6.415 | -7.0779 | |

| Left Corpus Callosum | 2.232 | -2.1364 | 4.8451 | -0.8379 | |||

| 3 | Right Visual Cortex | 184 | 3.685 | 5.1635 | 5.515 | -7.0779 | |

| Left Visual Cortex | 3.8242 | -5.5213 | 4.9396 | -7.5579 | |||

| 4 | Right Hippocampus | 73 | 2.8166 | 5.5548 | 6.9645 | -6.5979 | |

| Left Hippocampus | 2.3407 | -1.0242 | 5.1627 | -3.7179 | |||

| 5 | Right Auditory Cortex | 106 | 3.5349 | 7.2823 | 6.0527 | -5.1579 | |

| Left Auditory Cortex | 2.2824 | -7.1698 | 5.7592 | -4.6779 | |||

| 6 | Left Cingulate Gyrus | 63 | 2.6656 | -0.3998 | 4.6868 | -1.3179 | |

| Right Cingulate Gyrus | 2.931 | -0.123 | 4.7028 | -1.3179 | |||

| 7 | Left Somatosensory Cortex | 410 | 4.5739 | -4.6663 | 3.6151 | -1.7979 | |

| Right Somatosensory Cortex | 4.0076 | 3.7456 | 4.0169 | -0.8379 | |||

| 8 | Left Motor Cortex | 80 | 2.6003 | -1.0768 | 4.9651 | -9.9579 | |

| Right Motor Cortex | 3.5153 | 1.2223 | 3.6968 | -2.2779 | |||

| 9 | Left Prefrontal Cortex | 52 | 2.4375 | -0.1624 | 6.0595 | -8.5179 | |

| Right Prefrontal Cortex | 2.3664 | -0.024 | 6.0675 | -8.5179 | |||

| MIA vs CTL (Increase) | 1 | Right Posterior Parietal Cortex | 51 | 3.6166 | 4.9921 | 5.294 | -4.6779 |

| 2 | Left Third Ventricle | 50 | 2.3844 | -2.4132 | 5.9973 | -0.8379 |

VBM analysis of T2-weighted imaging in rats ROIs with significant changes.

Ke represents the total number of pixels with differences within the cluster, MaxT represents the t-value of the point with the maximum difference, and X, Y, Z are the coordinates of the point with the maximum difference.

3.2 DTI analysis

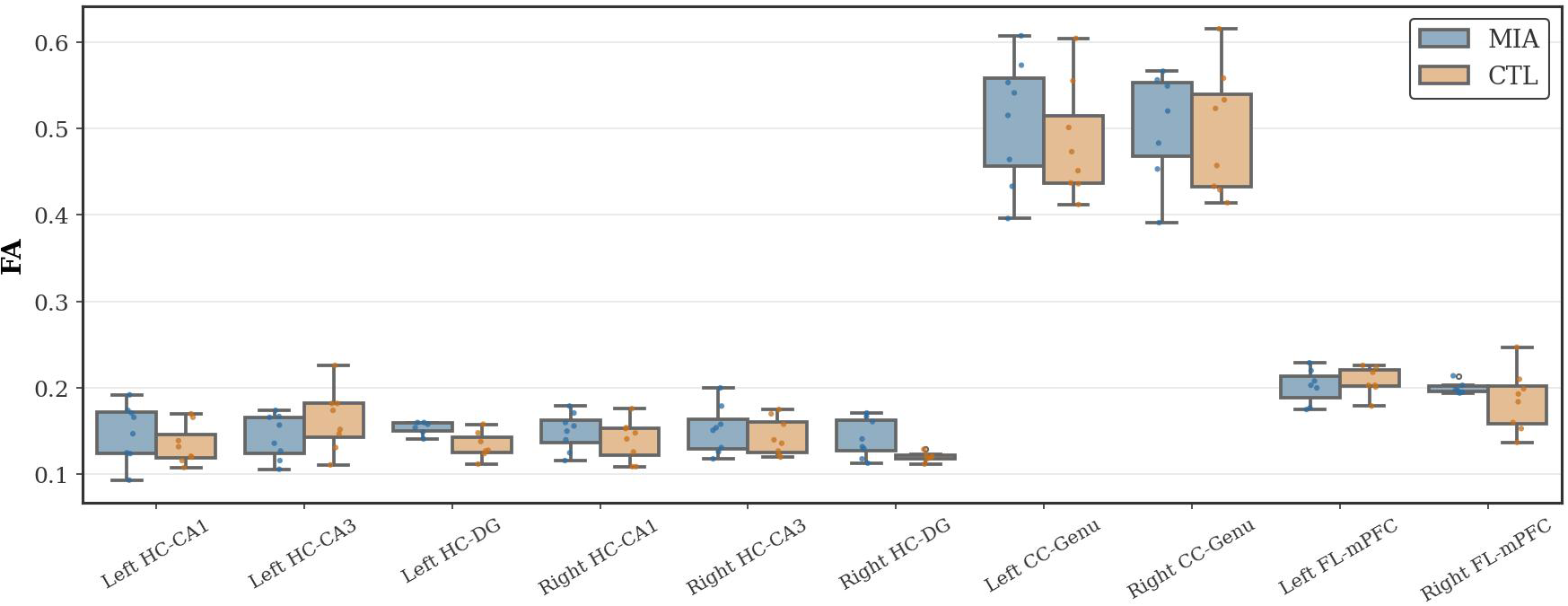

3.2.1 FA statistical results

Fractional anisotropy (FA), an indicator of white matter integrity, was analyzed. As Figure 2 shows, no significant differences in FA values were observed between the groups in the hippocampus, corpus callosum, or frontal lobe.

Figure 2

Changes in FA in the hippocampus (HC), corpus callosum (CC), and frontal lobe (FL) of rats in the CTL and MIA groups. “*” indicates p<0.05.

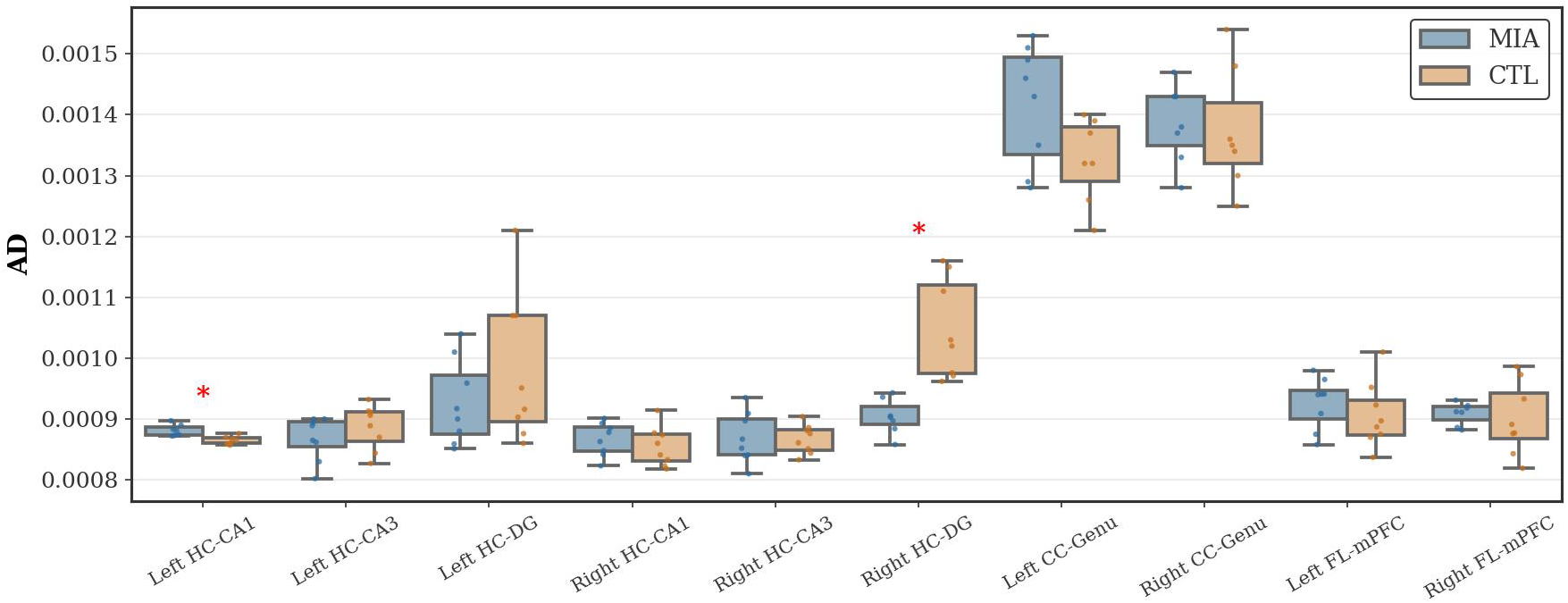

3.2.2 AD statistical results

As Figure 3 shows, in the hippocampal region, the MIA group showed a significant decrease in AD values in the left CA1 region of the hippocampus (p<0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.01, t-statistic = 3.76). In contrast, in the MIA group, the right dentate gyrus exhibited a significant increase in AD values compared with the CTL group (p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -2.28, t-statistic = 4.66), indicating altered microstructural integrity. No significant differences in AD values were observed between the groups in the corpus callosum or frontal lobe.

Figure 3

Changes in AD in the hippocampus, corpus callosum, and frontal lobe of rats in the CTL and MIA groups. “*” indicates p<0.05.

3.2.3 MD statistical results

As Figure 4 shows, in the hippocampal region, the MIA group showed a significant increase in MD values compared to the CTL group in the right dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -1.69, t-statistic = -3.37). No significant differences in MD values were observed between the groups in the frontal lobe or corpus callosum.

Figure 4

Changes in MD in the hippocampus, corpus callosum, and frontal lobe of rats in the CTL and MIA groups. “*” indicates p<0.05.

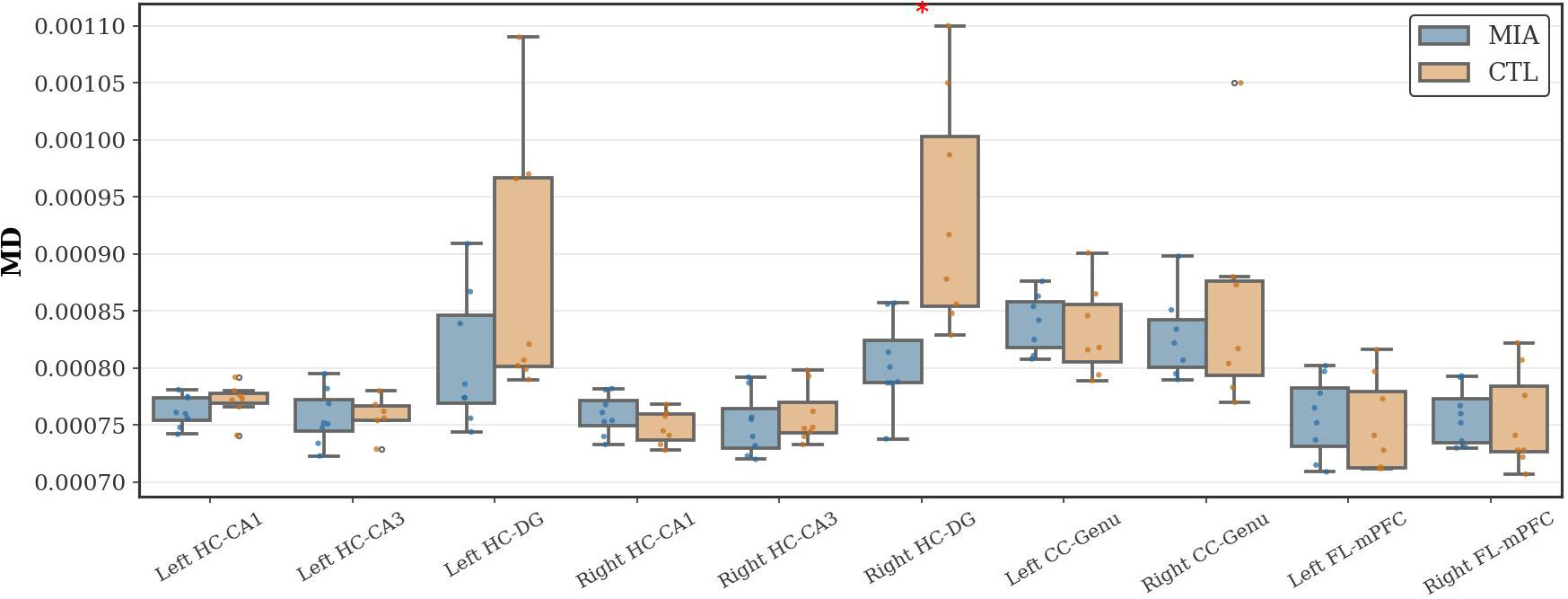

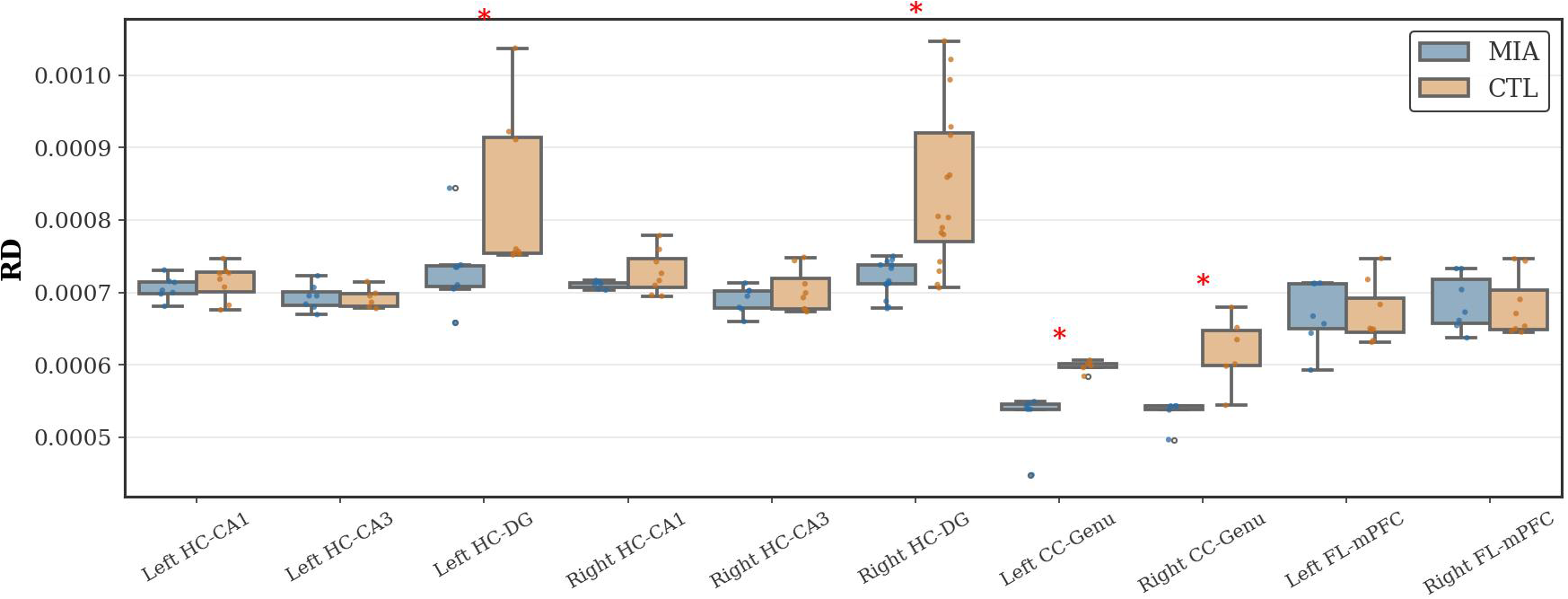

3.2.4 RD statistical results

As Figure 5 shows, in the hippocampal region, the MIA group exhibited significantly increased RD values compared to the CTL group in both the left and right dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Left: p<0.05, U-statistic = 5.0; Right: p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -1.64, t-statistic = -3.39). In the corpus callosum, compared to the CTL group, the MIA group showed significantly increased RD values in both the left and right genu of the corpus callosum (p<0.05, U-statistic = 0.0). No significant differences in RD values were observed between the groups in the frontal lobe.

Figure 5

Changes in RD in the hippocampus, corpus callosum, and frontal lobe of rats in the CTL and MIA groups. “*” indicates p<0.05.

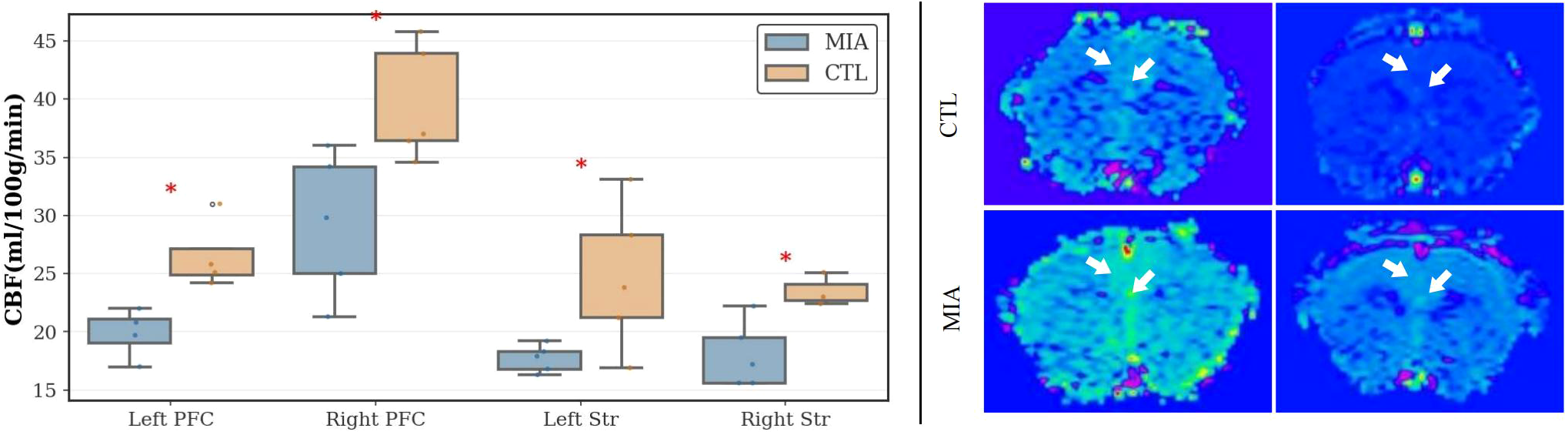

3.3 ASL analysis

As Figure 6 (left) and Figure 6 (right), in the prefrontal cortex, compared to the CTL group, the MIA group exhibited significantly increased CBF values in both the left and right frontal lobes (Left: p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -2.52, t-statistic = -2.90; Right: p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -1.80, t-statistic = -3.57). In the striatum, the MIA group showed significantly increased CBF values relative to the CTL group in both hemispheres (Left: p<0.05, Cohen’s d = -1.54, t-statistic = -2.44; Right: <0.05, Cohen’s d = -2.24, t-statistic = -3.06).

Figure 6

Left: Changes in CBF values in the left and right prefrontal cortex and left and right striatum of the two rat groups. “*” indicates p< 0.05. Right: Representative ASL MR images of rats. The top row represents the CTL group, and the bottom row represents the MIA group. Warm colors (yellow/green/red) indicate higher perfusion, while cool colors (blue) indicate lower perfusion.

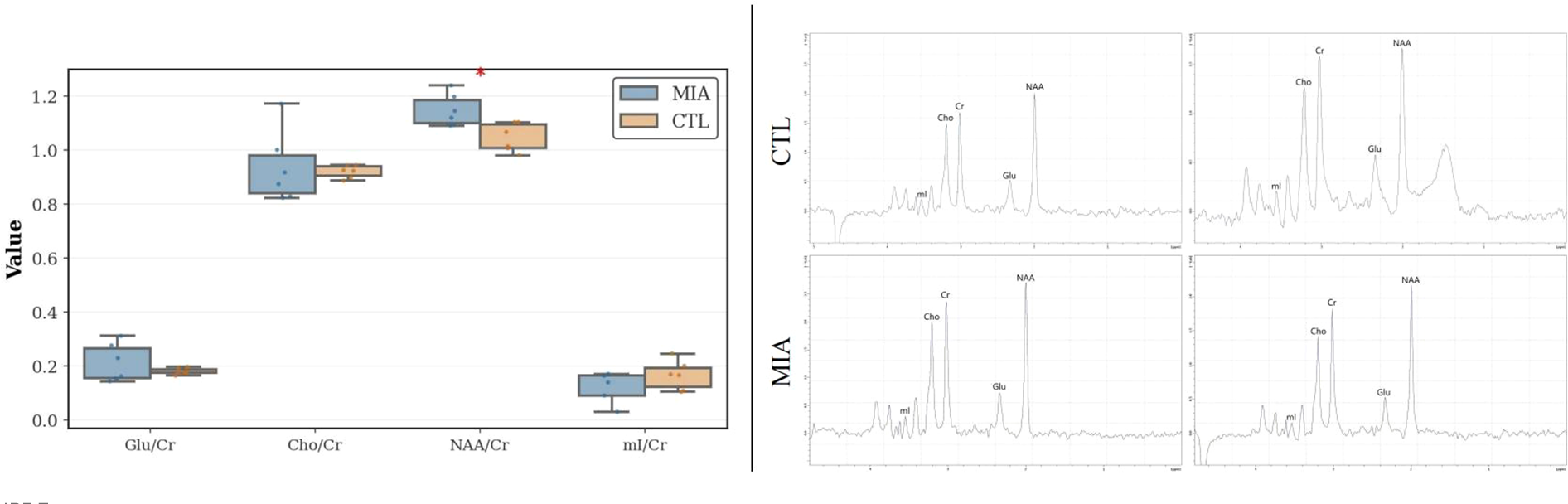

3.4 MRS analysis

As shown in Figure 7 (left and right), differential analysis revealed that, compared to the CTL group, the MIA group had a significantly reduced NAA/Cr ratio (p<0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.80, t-statistic = 3.11). No significant differences were observed for other ratios (mI/Cr, Cho/Cr, Glu/Cr) or in other inter-group comparisons.

Figure 7

Left: MRS analysis of changes in the two rat groups, showing variations in mI/Cr, Cho/Cr, Glu/Cr, and NAA/Cr ratios. Right: Representative MRS spectra of rats. The top row represents the CTL group, and the bottom row represents the MIA group.

4 Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate imaging alterations in brain regions of the prenatal Poly(I:C) rat model using multimodal MRI. Therefore, in the following discussion, we will address four aspects: T2 structural imaging, DTI white matter microstructure, ASL cerebral perfusion, and MRS neurometabolism. We will focus on comparing the similarities and differences between this study and existing animal model research, analyzing changes in brain regions and their potential causes, highlighting the correspondence among multimodal MRI results, and concluding with a summary of the study’s limitations.

4.1 T2 structural imaging

VBM analysis of T2-weighted images revealed that the MIA group exhibited significant reductions in gray matter density in multiple brain regions, including the bilateral striatum, corpus callosum, visual cortex, hippocampus, auditory cortex, cingulate cortex, sensory cortex, motor cortex, and prefrontal cortex. In contrast, increased gray matter density was observed in the right posterior parietal cortex, along with enlargement of the left third ventricle. These findings indicate widespread structural abnormalities in the Poly(I:C) model.

Previous studies using the Poly(I:C)-induced MIA rat model have reported structural alterations in several key brain regions. For example, reductions in hippocampal and striatal density have been associated with schizophrenia-like behavioral phenotypes (37). Piontkewitz et al. (13) observed significant reductions in hippocampal, striatal, and prefrontal volumes in enlargement of the ventricles by ventricular enlargement. Liu et al. (17) similarly noted markedly increased ventricular density, decreased gray matter density, and white matter microstructural disruption in offspring following Poly(I:C) exposure using 9.4T MRI combined with DTI and MRE. Romero-Miguel et al. (16) further validated these findings through MRI and metabolic analysis, both indicating that MIA induces extensive brain morphological alterations similar to those observed in schizophrenia. Haker et al. (37) identified through machine learning analysis that microstructural alterations in the male MIA model were concentrated in the prefrontal and corpus callosum, correlating with cognitive impairments. Casquero-Veiga et al. (14), applying VBM in female Poly(I:C) rats, observed significant gray matter elevation in the cingulate cortex, together with enlargement of the lateral and fourth ventricles. They also reported increased white matter density in the posterior cingulate cortex (within the posterior parietal region), suggesting potential abnormalities in this area. Overall, prior research has focused mainly on the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and ventricles, whereas regions such as the posterior parietal cortex have received relatively little attention.

In the present study, VBM revealed novel structural alterations not consistently highlighted in earlier reports (38, 39), namely gray matter reductions in the cingulate cortex and density increases in the right posterior parietal cortex. The posterior parietal hypertrophy contrasts with the atrophy typically observed in schizophrenia and may reflect compensatory remodeling or aberrant developmental processes. The cingulate cortex, a key region for emotional regulation and cognitive control, may contribute to the emotional and cognitive deficits observed in this model. These discrepancies with previous studies may partly result from methodological differences: (1) Administration of Poly I:C at 10 mg/kg on GD9 (compared to 4 mg/kg on GD15 (13, 16)) may cause more pronounced disruption of early neurogenesis; (2) Use of male offspring only (compared to female offspring in Casquero-Veiga et al. (14)); (3) The absence of prenatal omega-3 supplementation (present in Romero-Miguel et al. (16)); (4) Neurodevelopmental MIA versus pharmacological MK801 models (40).

In summary, this study confirms the presence of widespread structural abnormalities in the Poly(I:C) model and identifies novel alterations in the cingulate and posterior parietal cortices. These findings suggest that the model disrupts the development of emotion–cognition circuits, as well as sensory–motor regions. Importantly, the results highlight both consistencies with previous reports and new region-specific alterations, which may arise from methodological differences, model variations, or age-related factors.

4.2 DTI white matter microstructure

In the hippocampus, subregions CA1, CA3, and the dentate gyrus were selected as ROIs, forming the classic trisynaptic circuit (DG → CA3 → CA1) (41), which underlies hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (42). Abnormalities in this circuit are closely associated with memory deficits and information-processing impairments in schizophrenia. In the corpus callosum, the genu was chosen as an ROI because it connects the bilateral prefrontal cortices, with its integrity directly influencing prefrontal function. In the frontal lobe, the medial prefrontal cortex was selected as the ROI; medial prefrontal cortex dysfunction is a hallmark feature of schizophrenia.

DTI provides insight into the microstructural integrity of white matter tracts. Previous studies have shown that prenatal exposure to Poly(I:C) can disrupt myelination in the offspring’s brains, leading to white matter pathology in adulthood. For example, a longitudinal study reported that from 4 weeks of age, Poly(I:C) rats exhibited approximately 40% larger ventricular volumes than controls, alongside increased water diffusivity in major white matter tracts—including the corpus callosum, internal capsule, and external capsule—suggesting reduced myelin integrity. The study also observed elevated MD and RD in these tracts, with corresponding decreases in FA, reflecting the extent of white matter fiber tract damage (17). Some findings have been reported in other MIA studies. Di Biase et al. (22) demonstrated elevated extracellular free water in the corpus callosum and striatum of male offspring, with no significant reduction in myelin fatty acids, indicating that early white matter pathology is primarily characterized by extracellular inflammation/edema rather than inflammation-associated demyelination. Similarly, Singh et al. (43) observed impaired myelination and reduced D2 receptor binding in the corpus callosum following early-life Poly(I:C) exposure, linking microstructural injury to dopaminergic dysfunction. Wood et al. (23) and Missault et al. (24) further suggested that early-stage white matter abnormalities may emerge gradually, with functional network hypersynchrony preceding overt structural damage.

Consistent with these findings, we observed imaging evidence of myelin damage in the hippocampus and corpus callosum. Specifically, the Poly(I:C) group exhibited significantly elevated MD and RD in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, along with increased RD in the genu of the corpus callosum. Casquero-Veiga et al. similarly reported metabolic and morphological changes in female Poly(I:C) rats, supporting the impact of MIA on white matter integrity (14).

However, diffusion characteristics in frontal lobe white matter have shown inconsistent results in the literature (16). While some studies have reported increased FA in the frontal lobe of MIA rats, we observed no significant changes in the mPFC ROI, which may be due to differences in ROI selection, subject sex, or age at scanning.

Overall, our DTI results corroborate those of Liu et al. (17), demonstrating widespread white matter microstructural damage in Poly(I:C) offspring, particularly in hippocampus-related pathways critical for learning and memory and in the genu of the corpus callosum. Differences in white matter damage patterns across studies may stem from multiple factors: (1) variations in ROI selection and analysis methods, (2) differences in imaging time points (adolescence vs. adulthood), and (3) batch or strain differences in the animal model.

In summary, DTI provides new evidence of white matter myelin pathology in the Poly(I:C) model and, together with structural imaging, highlights abnormalities in the hippocampus–prefrontal circuitry.

4.3 ASL cerebral perfusion

Core cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are closely linked to hypoactivity in the prefrontal cortex (44). Additionally, the striatum, a central component of the basal ganglia, receives projections from the entire cerebral cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex (45). Therefore, we focused on measuring CBF in the prefrontal cortex and striatum.

ASL provides a noninvasive method to quantify CBF and assess brain functional states. Clinical studies indicate that individuals with schizophrenia often exhibit weakened functional connectivity within the prefrontal-striatal circuit, alongside increased regional glucose metabolism and blood flow in the striatum (40, 46). Research on cerebral perfusion in animal models of MIA remains limited. Drazanova et al. administered ASL to Poly(I:C)-treated rats and observed enlarged lateral ventricles in male offspring, along with increased perfusion in the circle of Willis, hippocampus, and sensorimotor cortex (26). These findings suggest that MIA may induce hyperperfusion in specific brain regions, potentially reflecting overactivation of dopaminergic or glutamatergic pathways.

In this study, CBF measurements revealed significantly higher perfusion in the bilateral prefrontal cortex and striatum of Poly(I:C) male offspring relative to controls, indicating localized perfusion abnormalities. Our results partially align with those of Drazanova et al., who observed ventricular enlargement and increased perfusion in major brain regions. Similarly, studies using the methylazoxymethanol (MAM) model have reported increased CBF across multiple brain regions, consistent with our findings (26).

Multimodal integration suggests that structural atrophy and elevated blood flow can coexist in the Poly(I:C) model. For instance, the prefrontal cortex showed reduced volume alongside increased local perfusion, suggesting that structurally compromised regions may maintain activity via compensatory hyperactivation. This pattern mirrors the inefficient compensatory hyperperfusion observed in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients during early disease stages (47), indicating that the MIA model recapitulates this pathological feature.

In summary, the ASL results provide evidence of functional overactivation in the Poly(I:C) model. Combined with structural and DTI findings, these results offer a more comprehensive understanding of brain alterations induced by MIA.

4.4 MRS neurometabolites

MRS enables quantitative assessment of brain metabolite levels, reflecting neuronal and glial function. In this study, we examined relative changes in NAA, Cho, Glu, and mI in the prefrontal cortex. The results showed a significant decrease in NAA/Cr in the Poly(I:C) group, whereas no significant differences were observed for Cho/Cr, Glu/Cr, or mI/Cr.

NAA is widely recognized as a biomarker reflecting neuronal integrity and mitochondrial function, with its reduction indicating neuronal injury, dysfunction, or loss (48). This finding is consistent with ¹H-MRS studies of clinical schizophrenia, which frequently report significantly reduced NAA levels in the prefrontal cortex, supporting the pathological hypothesis of abnormal metabolism and function in prefrontal neurons (49). Previous animal studies similarly support metabolic abnormalities in MIA models. For example, Vernon et al. conducted longitudinal MRS tracking in rats and found that gestational Poly(I:C) exposure led to significantly reduced glutathione and taurine levels in the prefrontal cortex of adult offspring rats (50). This finding is consistent with our observations. Recent studies have confirmed that reduced NAA/Cr ratios are among the most reproducible neurochemical signatures of schizophrenia-related pathology (51).

The absence of significant changes in other metabolites does not exclude their involvement in schizophrenia pathophysiology. For instance, Mei et al. (52) reported glial regulation of Glu, which may not have been detected in this study due to the timing of measurements (adulthood) or the limited sample size, potentially missing early inflammation-related changes such as elevated Cho or mI. Similarly, the lack of Glu differences does not invalidate the glutamate hypothesis (53), but may reflect a subclinical or early-stage model.

Overall, the reduction in NAA/Cr provides a robust metabolic marker, reinforcing the relevance of the Poly(I:C) model. Among the metabolites examined, the decline in NAA/Cr represents the most consistent evidence of neuronal compromise, while other metabolites merit further investigation in longitudinal studies with larger cohorts.

4.5 Multimodal analysis

Findings across multiple MRI modalities provide mutually supportive evidence of brain alterations in the Poly(I:C) model. In the prefrontal cortex—a hub for cognitive control and one of the regions most vulnerable to maternal immune activation (54)—we observed concurrent gray matter reduction (T2) and decreased NAA levels (MRS). Rather than representing independent abnormalities, these two findings may indicate a shared biological origin, involving impaired neuronal integrity and compromised energy metabolism, likely through disrupted synaptic development, altered glial–neuronal interactions (55), or impaired myelination (56).

Ventricular enlargement detected by structural MRI also fits into this framework. The surrounding white-matter regions exhibited elevated diffusivity on DTI, suggesting axonal or myelin degeneration. This spatial correspondence implies that ventricular expansion may partly result from periventricular tissue loss, reflecting a chronic neurodevelopmental trajectory rather than an isolated structural change (17).

Meanwhile, increased local perfusion, as identified by arterial spin labeling (ASL), provides complementary functional insight, indicating potential compensatory or pathological hyperactivation in structurally compromised regions.

These subtle differences, though minor in degree, representatively embody the characteristics of the MIA model and consistently involve the prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-striatum circuit, thereby facilitating behavioral phenotypes through stable neurobiological transformations (57).

Taken together, the complementary abnormalities across T2, DTI, ASL, and MRS imaging form a coherent picture of MIA-induced pathology: early immune-driven neurodevelopmental disruptions leading to long-term deficits in neuronal viability, myelin integrity, vascular function, and circuit-level activity. This integrated multimodal approach therefore provides a more complete framework for understanding how maternal inflammation shapes the interconnected structural, metabolic, and functional networks relevant to schizophrenia.

4.6 Study limitations

First, the limited sample size (nine rats per group) may increase the risk of incidental findings. In our study, our statistical results were based on group-level comparisons and did not indicate the presence of clearly distinguishable subtypes within the groups. Second, the cross-sectional design, with assessment at a single adult time point, precludes evaluation of dynamic developmental trajectories of brain changes. Third, manual segmentation of DTI ROIs, although precise, involves subjectivity that may affect reproducibility. Fourth, this study did not directly measure immune markers, inflammatory cytokines, or neurotransmitter levels, limiting mechanistic validation. Fifth, while four MRI modalities were included, additional approaches—such as functional connectivity—were not assessed, which could provide further insight. Sixth, inherent resolution limitations of MRI may preclude detection of microscopic pathological changes, necessitating complementary histological analyses or higher-field imaging techniques. Seventh, another limitation of this study is the relatively large thickness of the MRI slices, which may lead to a partial volume effect, especially in small structures of the rat brain, potentially affecting the accuracy of the results. Future research could use higher resolution (e.g., 0.5 mm slices) or ultra-high field MRI to mitigate this problem. Finally, a major limitation is that only male offspring were included. Although the decision was initially motivated by the greater stability of PPI deficits in males, this restriction significantly constrains the generalizability of our findings. Prior literature indicates robust sex differences in neurodevelopmental responses to maternal immune activation, suggesting that MIA-induced abnormalities may be sexually dimorphic. Future work should systematically include both male and female offspring to determine whether the multimodal MRI alterations observed here exhibit sex-specific patterns and to clarify how such differences may relate to the known sex disparities in schizophrenia.

Despite these limitations, the present findings offer valuable multimodal evidence of MIA-induced neurodevelopmental pathology and provide a foundation for more comprehensive, sex-inclusive, and mechanistically integrated future investigations.

5 Conclusion

This study systematically characterized brain pathological features in a Poly(I:C)-induced maternal immune activation (MIA) model, using multimodal MRI, including structural imaging, DTI, ASL, and MRS. We observed significant volume reductions, white matter microstructural damage, regional hyperperfusion, and neurometabolic abnormalities in key brain regions, highlighting pathological alterations within the prefrontal cortex–hippocampus–striatum circuit. Future studies employing larger and more diverse cohorts, longitudinal designs, molecular and behavioral biomarkers, and inclusion of both sexes will be essential to further elucidate the developmental trajectories, biological mechanisms, and clinical relevance of MIA-induced brain changes. Collectively, the present work contributes to a growing body of evidence positioning the MIA model as a valuable tool for investigating neurodevelopmental mechanisms relevant to schizophrenia and related psychiatric disorders.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Ethics Committee for Medical and Laboratory Animals, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YZ: Resources, Writing – original draft. YL: Resources, Writing – original draft. ZF: Software, Writing – original draft. WS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7222274), the Capital Health Development Research Fund (2022–2–7035), the 2025 Beijing Medical and Health Collaborative High-Quality Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine Project Fund (YC202401YW0804), and the New Drug Development Project of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (2025-YJKT-XYYF-05).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their contributions and all organizations that funded our research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fpsyt.2026.1782780.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1710696/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Patterson PH . Immune involvement in schizophrenia and autism: etiology, pathology and animal models. Behav Brain Res. (2009) 204:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.016

2

Aguilar-Valles A Rodrigue B Matta-Camacho E . Maternal immune activation and the development of dopaminergic neurotransmission of the offspring: relevance for schizophrenia and other psychoses. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:852. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00852

3

Donegan JJ Boley AM Glenn JP Carless MA Lodge DJ . Developmental alterations in the transcriptome of three distinct rodent models of schizophrenia. PloS One. (2020) 15:e0232200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232200

4

Gzieło K Piotrowska D Litwa E Popik P Nikiforuk A . Maternal immune activation affects socio-communicative behavior in adult rats. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:1918. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-28919-z

5

Patrich E Piontkewitz Y Peretz A Weiner I Attali B . Maternal immune activation produces neonatal excitability defects in offspring hippocampal neurons from pregnant rats treated with poly i:c. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:19106. doi: 10.1038/srep19106

6

Murray BG Davies DA Molder JJ Howland JG . Maternal immune activation during pregnancy in rats impairs working memory capacity of the offspring. Neurobiol Learn Memory. (2017) 141:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.04.005

7

Osborne AL Solowij N Babic I Huang XF Weston-Green K . Improved social interaction, recognition and working memory with cannabidiol treatment in a prenatal infection (poly i: C) rat model. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2017) 42:1447–57. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.40

8

Chamera K Trojan E Kotarska K Szuster-Guszczak M Bryniarska N Tylek K et al . Role of polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid-induced maternal immune activation and subsequent immune challenge in the behaviour and microglial cell trajectory in adult offspring: A study of the neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:1558. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041558

9

Kreitz S Zambon A Ronovsky M Budinsky L Helbich TH Sideromenos S et al . Maternal immune activation during pregnancy impacts on brain structure and function in the adult offspring. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 83:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.09.011

10

Griego E Cerna C Sollozo-Dupont I Fuenzalida M Galván EJ . Maternal immune activation alters temporal precision of spike generation of ca1 pyramidal neurons by unbalancing gabaergic inhibition intheoffspring. Brain Behav Immun. (2025) 123:211–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.09.012

11

Griego E Segura-Villalobos D Lamas M Galvan EJ . Maternal immune activation increases excitability via downregulation of a-type potassium channels and reduces dendritic complexity of hippocampal neurons of the offspring. Brain Behav Immun. (2022) 105:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.07.005

12

Bauman MD Van de Water J . Translational opportunities in the prenatal immune environment: Promises and limitations of the maternal immune activation model. Neurobiol Dis. (2020) 141:104864. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104864

13

Piontkewitz Y Arad M Weiner I . Abnormal trajectories of neurodevelopment and behavior following in utero insult in the rat. Biol Psychiatry. (2011) 70:842–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.007

14

Casquero-Veiga M Lamanna-Rama N Romero-Miguel D Rojas-Marquez H Alcaide J Beltran M et al . The poly i: C maternal immune stimulation model shows unique patterns of brain metabolism, morphometry, and plasticity in female rats. Front Behav Neurosci. (2023) 16:1022622. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.1022622

15

Winter R Akinola B Barroeta-Hlusicka E Meister S Pietzsch J Winter C et al . Comparison of manual and automated ventricle segmentation in the maternal immune stimulation rat model of schizophrenia. bioRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.06.10.144022

16

Romero-Miguel D Casquero-Veiga M Lamanna-Rama N Torres-Sánchez S MacDowell KS García-Partida JA et al . N-acetylcysteine during critical neurodevelopmental periods prevents behavioral and neurochemical deficits in the poly i: C rat model of schizophrenia. Trans Psychiatry. (2024) 14:14. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02652-7

17

Liu L Bongers A Bilston LE Jugé L . The combined use of dti and mr elastography for monitoring microstructural changes in the developing brain of a neurodevelopmental disorder model: Poly (i: C)-induced maternal immune-activated rats. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0280498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280498

18

Bao J Tu H Li Y Sun J Hu Z Zhang F et al . Diffusion tensor imaging revealed microstructural changes in normal-appearing white matter regions in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:837452. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.837452

19

Nelson MR Keeling EG Stokes AM Bergamino M . Exploring white matter microstructural alterations in mild cognitive impairment: a multimodal diffusion mri investigation utilizing diffusion kurtosis and free-water imaging. Front Neurosci. (2024) 18:1440653. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1440653

20

Carreira Figueiredo I Borgan F Pasternak O Turkheimer FE Howes OD . White-matter free-water diffusion mri in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2022) 47:1413–20. doi: 10.1038/s41386-022-01272-x

21

Mamah D Chen S Shimony JS Harms MP . Tract-based analyses of white matter in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, aging, and dementia using high spatial and directional resolution diffusion imaging: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1240502. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1240502

22

Di Biase MA Katabi G Piontkewitz Y Cetin-Karayumak S Weiner I Pasternak O . Increased extracellular free-water in adult male rats following in utero exposure to maternal immune activation. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 83:283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.09.010

23

Wood TC Edye ME Harte MK Neill JC Prinssen EP Vernon AC . Mapping the impact of exposure to maternal immune activation on juvenile wistar rat brain macro-and microstructure during early post-natal development. Brain Neurosci Adv. (2019) 3:2398212819883086. doi: 10.1177/2398212819883086

24

Missault S Anckaerts C Ahmadoun S Blockx I Barbier M Bielen K et al . Hypersynchronicity in the default mode-like network in a neurodevelopmental animal model with relevance for schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. (2019) 364:303–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.02.040

25

Alsop DC Detre JA Golay X Günther M Hendrikse J Hernandez-Garcia L et al . Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion mri for clinical applications: a consensus of the ismrm perfusion study group and the european consortium for asl in dementia. Magnet Resonance Med. (2015) 73:102–16. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25197

26

Drazanova E Ruda-Kucerova J Kratka L Horska K Demlova R Starcuk Z et al . Poly (i: C) model of schizophrenia in rats induces sex-dependent functional brain changes detected by mri that are not reversed by aripiprazole treatment. Brain Res Bull. (2018) 137:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.11.008

27

Rasile M Lauranzano E Faggiani E Ravanelli MM Colombo FS Mirabella F et al . Maternal immune activation leads to defective brain–blood vessels and intracerebral hemorrhages in male offspring. EMBO J. (2022) 41:e111192. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022111192

28

Kanagasabai K Palaniyappan L Théberge J . Precision of metabolite-selective mrs measurements of glutamate, gaba and glutathione: A review of human brain studies. NMR Biomed. (2024) 37:e5071. doi: 10.1002/nbm.5071

29

Duarte JM . Concentrations of glutamate and n-acetylaspartate detected by magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the rat hippocampus correlate with hippocampal-dependent spatial memory performance. Front Mol Neurosci. (2024) 17:1458070. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2024.1458070

30

Capellán R Orihuel J Marcos A Ucha M Moreno-Fernández M Casquero-Veiga M et al . Interaction between maternal immune activation and peripubertal stress in rats: impact on cocaine addiction-like behaviour, morphofunctional brain parameters and striatal transcriptome. Trans Psychiatry. (2023) 13:84. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02378-6

31

Reginatto MW Fontes KN Monteiro VR Silva NL Andrade CBV Gomes HR et al . Effect of sublethal prenatal endotoxaemia on murine placental transport systems and lipid homeostasis. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:706499. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.706499

32

Huo S Wu F Zhang J Wang X Li W Cui D et al . Porcine soluble cd83 alleviates lps-induced abortion in mice by promoting th2 cytokine production, treg cell generation and trophoblast invasion. Theriogenology. (2020) 157:149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.07.026

33

Lin X Peng Q Zhang J Li X Zhang W . Quercetin prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced experimental preterm labor in mice and increases offspring survival rate. Reprod Sci. (2020) 157:149–61. doi: 10.1007/s43032-019-00034-3

34

Guma E Bordeleau M González Ibáñez F Picard K Snook E Desrosiers-Grégoire G et al . Differential effects of early or late exposure to prenatal maternal immune activation on mouse embryonic neurodevelopment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2022) 119:e2114545119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2114545119

35

Fang Y Liu Y Wang Y Sun W . Mechanism of distan qingnao formula in improving negative symptoms of poly schizophrenia rats based on nf-κb/nlrp3 pathway. J Mol Diagn Ther. (2025) 17:1225. doi: 10.19930/j.cnki.jmdt.2025.07.055

36

Liu Y Hang X Zhang Y Fang Y Yuan S Zhang Y et al . Maternal immune activation induces sex dependent behavioral differences in a rat model of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1375999. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1375999

37

Haker R Helft C Natali Shamir E Shahar M Solomon H Omer N et al . Characterization of brain abnormalities in lactational neurodevelopmental poly i: C rat model of schizophrenia and depression using machine-learning and quantitative mri. J Magnet Resonance Imaging. (2025) 61:2281–91. doi: 10.1002/jmri.29634

38

Wu H Wang X Gao Y Lin F Song T Zou Y et al . Nmda receptor antagonism by repetitive mk801 administration induces schizophrenia-like structural changes in the rat brain as revealed by voxel based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroscience. (2016) 322:221–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.043

39

Romero-Miguel D Casquero-Veiga M Lamanna-Rama N Chávez-Valencia R Gómez-Rangel V Hadar R et al . Prenatal omega-3 fatty acids supplementation mitigates some schizophrenia-like deficits in offspring: A pet and mri study in a rat model. Trans Psychiatry. (2025) 15:436. doi: 10.1038/s41398-025-03612-z

40

Yang KC Yang BH Liu MN Liou YJ Chou YH . Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is associated with prefrontal–striatal functional hypoconnectivity and striatal dopaminergic abnormalities. J Psychopharmacol. (2024) 38:515–25. doi: 10.1177/02698811241257877

41

Longo L Lima T Bila MC Brogin J Faber J . A minimalist computational model of slice hippocampal circuitry based on neuronify for teaching neuroscience. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0319641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0319641

42

Rolls ET . Treves A. A theory of hippocampal function: new developments. Prog Neurobiol. (2024) 238:102636. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2024.102636

43

Singh B Dhuriya YK Patro N Thakur MK Khanna VK Patro IK . Early life exposure to poly i: C impairs striatal da-d2 receptor binding, myelination and associated behavioural abilities in rats. J Chem Neuroanat. (2021) 118:102035. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2021.102035

44

Dienel SJ Schoonover KE Lewis DA . Cognitive dysfunction and prefrontal cortical circuit alterations in schizophrenia: developmental trajectories. Biol Psychiatry. (2022) 92:450–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.03.002

45

Lanciego JL Luquin N Obeso JA . Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. (2012) 2:a009621. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009621

46

Grimaldi DA Patane' A Cattarinussi G Sambataro F . Functional connectivity of the striatum in psychosis: Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies and replication on an independent sample. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2025) 174:106179. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106179

47

Gangl N Conring F Federspiel A Wiest R Walther S Stegmayer K . Resting-state perfusion in motor and fronto-limbic areas is linked to diminished expression of emotion and speech in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia. (2023) 9:51. doi: 10.1038/s41537-023-00384-7

48

Song T Song X Zhu C Patrick R Skurla M Santangelo I et al . Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and metabolic alterations in the progression of alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis of in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Ageing Res Rev. (2021) 72:101503–. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101503

49

Whitehurst TS Osugo M Townsend L Shatalina E Vava R Onwordi EC et al . Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of n-acetyl aspartate in chronic schizophrenia, first episode of psychosis and high-risk of psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2020) 119:255–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.10.001

50

Vernon AC So PW Lythgoe DJ Chege W Cooper JD Williams SC et al . Longitudinal in vivo maturational changes of metabolites in the prefrontal cortex of rats exposed to polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid in utero. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2015) 25:2210–20. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.09.022

51

Yang YS Smucny J Zhang H Maddock RJ . Meta-analytic evidence of elevated choline, reduced n-acetylaspartate, and normal creatine in schizophrenia and their moderation by measurement quality, echo time, and medication status. NeuroImage: Clin. (2023) 39:103461. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103461

52

Mei YY Wu DC Zhou N . Astrocytic regulation of glutamate transmission in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00544

53

Merritt K McCutcheon RA Aleman A Ashley S Beck K Block W et al . Variability and magnitude of brain glutamate levels in schizophrenia: a meta and mega-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. (2023) 28:2039–48. doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-01991-7

54

Vlasova RM Iosif AM Ryan AM Funk LH Murai T Chen S et al . Maternal immune activation during pregnancy alters postnatal brain growth and cognitive development in nonhuman primate offspring. J Neurosci. (2021) 41:9971–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0378-21.2021

55

Richetto J Meyer U . Epigenetic modifications in schizophrenia and related disorders: molecular scars of environmental exposures and source of phenotypic variability. Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 89:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.03.008

56

Zhang XF Chen T Yan A Xiao J Wong NK . Poly(i:c) challenge alters brain expression of oligodendroglia-related genes of adult progeny in a mouse model of maternal immune activation. Front Mol Neurosci. (2020) 13:115. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.00115

57

Guma E Snook E Spring S Lerch JP Nieman BJ Devenyi GA et al . Subtle alterations in neonatal neurodevelopment following early or late exposure to prenatal maternal immune activation in mice. NeuroImage: Clin. (2021) 32:102868. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102868

Summary

Keywords

arterial spin labeling (ASL), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), maternal immune activation (MIA), Poly(I:C), schizophrenia

Citation

Wu B, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Feng Z and Sun W (2025) Exploratory MIA study: multimodal magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of rat offspring induced by maternal Poly(I:C) exposure during pregnancy. Front. Psychiatry 16:1710696. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1710696

Received

22 September 2025

Revised

28 November 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Corrected

30 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Lei An, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, China

Reviewed by

Ernesto Griego, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, United States

Marta Casquero-Veiga, Health Research Institute Foundation Jimenez Diaz (IIS-FJD), Spain

Eleanor Mawson, Cardiff University, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wu, Zhang, Liu, Feng and Sun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenjun Sun, doctorsunwenjun@126.com; Yijie Zhang, zhangyijie360@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.