Abstract

The consequences of violence differ depending on gender. This study explores the associations between exposure to violence and mental health outcomes in Ecuador, a country with high levels of violence yet limited research on its psychological effects. Using a nationally representative dataset and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to reduce confounding bias, we examine gender-specific patterns of psychological outcomes. The analysis reveals that men exposed to violence are significantly more likely to display externalizing behaviors, including a near doubling of alcohol use (+93.6%) and heightened impulsivity, supporting theories of substance-based coping and behavioral dysregulation. In contrast, women exposed to violence show marked increases in internalizing symptoms, including depressive affect (+35.7%), perceived stress, and loneliness, reflecting emotion-focused coping strategies and affective vulnerability. While these findings support established gendered theories of violence, such as the self-medication hypothesis and emotion-focused coping, they must be interpreted with caution. The associations observed reflect robust statistical links rather than definitive causal pathways. It remains possible that pre-existing psychological vulnerabilities or unmeasured third variables contribute to both the likelihood of experiencing violence and subsequent mental health outcomes. The results underscore the importance of gender-sensitive mental health interventions: substance use and impulsivity should be targeted among men, while women’s care must be integrated with social and economic support systems. By focusing on a Latin American context, this study adds to global knowledge on the gendered psychological consequences of violence and highlights the need for longitudinal and interdisciplinary approaches.

1 Introduction

1.1 Exposure to violence

Violence, particularly physical and sexual violence, constitutes a pervasive public health issue with deep and lasting psychological consequences. According to the World Health Organization (1), violence refers to the intentional threat or use of physical force or power against oneself, another person, or a group, which results in or has a high probability of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation. In line with WHO guidelines, violence encompasses multiple forms – physical, sexual, psychological, and economic – that may occur within intimate partnerships, families, workplaces, or wider community settings (2, 3). These violent acts may occur in private or public spaces – most notably in domestic relationships, the workplace, or the community (e.g. 4, 5).

It is important to emphasize that violence can take additional forms – such as coercive control, psychological harassment, sexual harassment, and sexual relations involving coercive manipulation – and that it occurs across multiple settings, ranging from the private sphere (couple and family relationships) to public environments (workplaces, transportation systems, and community spaces) (e.g., 4–7).

Although frequently interpreted as isolated or external events, such experiences of violence are also deeply embedded within broader social, cultural, and economic structures. They intersect not only with conditions of economic vulnerability, gender inequality, and limited institutional protection, but also with cultural norms, social hierarchies, and access to healthcare systems (see 2, 8–10). This broader framing acknowledges that while socio-economic dimensions are central, they coexist with cultural and institutional dynamics that jointly shape the prevalence and consequences of violence. This study situates its analysis primarily within the framework of intimate partner violence and gender-based violence more broadly, as these forms are particularly prevalent and clinically relevant in the Ecuadorian and Latin American context while also carrying specific implications for the emergence of psychological harm (3, 11, 12).

From a psychological standpoint, exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and gender-based violence more broadly may precipitate a wide array of mental health difficulties. These include, but are not limited to, anxiety disorders, major depression, post-violence stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders (13–15). Framing violence primarily within the context of IPV is particularly relevant in Latin American and Ecuadorian settings, where such forms of violence are highly prevalent and clinically salient (2, 12, 16).

Conceptually, it is important to distinguish between “violence” as an exposure and “trauma” in the clinical sense. While clinical trauma is typically defined in diagnostic systems by syndrome-level criteria (e.g., PTSD) this study adopts a broader, integrative notion of psychological harm, consistent with contemporary psychological research, to capture distress-related symptoms that do not necessarily meet diagnostic thresholds (13, 17, 18). In this framework, violence is conceptualized as a potentially traumatic event, whereas psychological harm refers to the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral difficulties that may emerge or intensify following such exposure. Clarifying this distinction is essential, as the remainder of the manuscript operationalizes violence as an environmental stressor while analyzing its consequences through non-diagnostic indicators of psychological functioning (e.g., stress, depressive symptoms, impulsivity). This perspective ensures that the study captures subclinical yet clinically meaningful psychological responses, better reflecting the lived experience of affected individuals.

Operationally, in the present study, “violence” is measured as a dichotomous indicator of having ever experienced at least one form of violence (physical, psychological, sexual, or economic) within the family or intimate-partner sphere, based on nationally representative survey data from Ecuador (16). This choice reflects both the structure of the available data and the intention to capture lifetime exposure to gendered forms of violence that are particularly salient in this country.

1.2 Why men and women do not react in the same way: an ecological and integrative perspective

The psychological impact of violence does not occur in a vacuum but emerges from the interaction between individual, relational, community, and societal factors. Beyond the Bioecological Theory of Human Development (19), which has inspired extensive research across multiple fields (e.g., (20)), the World Health Organization’s ecological model conceptualizes violence as the result of processes operating at multiple levels – including biological vulnerabilities, family dynamics, community resources, and wider socio-cultural norms – which together shape both the risk of violence exposure and the ways in which individuals respond to it (2, 3).

Within this framework, gendered reactions to violence can be understood as the product of at least three intertwined dimensions. At the individual level, biological sex and neuropsychological functioning influence stress reactivity, emotion regulation, and susceptibility to internalizing or externalizing symptoms (17, 21, 22). At the relational level, patterns of power, economic dependence, and coercive control shape how violence is experienced and disclosed within intimate relationships (4, 23, 24). At the community and societal levels, gender norms, stigma, and institutional responses determine whether victims have access to protection, justice, and mental health care (9, 11).

Our study is anchored in an integrative conceptual framework that combines the WHO ecological model with two complementary psychological perspectives: (a) the self-medication hypothesis, which posits that individuals may use psychoactive substances to manage dysphoria and trauma-related affect (25–27), and (b) models of emotion-focused coping and rumination, which highlight how repetitive negative thinking and affective regulation strategies contribute to internalizing symptomatology, particularly among women (28).

A growing body of research suggests that these multi-level processes contribute to systematic differences in how men and women express psychological suffering. Women are more frequently exposed to patterns of intimate partner violence and economic abuse that foster emotional withdrawal, rumination, and internalizing symptomatology (28, 29). Men, in contrast, are socialized into norms of emotional restraint and self-reliance that discourage help-seeking and legitimize substance use or aggression as acceptable outlets for distress (9, 21, 29–31).

In Latin America – and particularly in Ecuador – these mechanisms are embedded in a context characterized by high levels of gender-based violence, marked social inequalities, and limited institutional protection (11, 12, 16). The ecological model is therefore especially pertinent for understanding why, in a same violent environment, men and women may follow differentiated psychological trajectories, with women more prone to internalizing responses and men to externalizing patterns. The following subsections build on this integrative perspective to describe these gendered mechanisms in more detail.

1.3 Internalizing psychological responses among women

Women are more likely to exhibit internalizing emotional responses following exposure to violence, including heightened levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation (2, 29). These psychological effects must first be understood within the broader context of women’s social positioning, which often entails greater exposure to power asymmetries, economic dependence, and social isolation (8, 32). Structural gender inequalities therefore play a central role in shaping women’s vulnerability to depressive and anxious symptomatology. Only secondarily can neurobiological processes complement this explanation, helping to clarify why some women develop persistent affective symptoms when confronted with violence exposure (17).

In Ecuador, the situation is particularly alarming: according to the National Survey on Gender-Based Violence (16), approximately 77% of Ecuadorian women have experienced at least one form of violence (psychological, physical, sexual, or economic) throughout their lives. This rate is substantially higher than the averages reported in large-scale international surveys such as the OSCE-led study on violence against women, which found that across 12 Eastern and Southern European countries, 60% of women reported psychological violence, 21% physical violence, and 7% sexual violence by an intimate partner since age 15 (33). This broader international comparison underscores the severity of the problem in the Latin American context (2). For additional comparative context, national data from France indicate similarly high levels of psychological and economic abuse (32), suggesting that gender-based violence remains pervasive even in high-income settings.

Such vulnerabilities may be particularly salient in Latin American settings, where structural and interpersonal violence are prevalent and gender inequalities remain deeply entrenched. Patterns of violence are not evenly distributed; rural and indigenous women face disproportionately high exposure, compounded by weak institutional responses, limited legal recourse, and restricted access to social protection systems (12). Despite the high prevalence of violence against women in Ecuador, documented in national statistics (16), the mental health consequences of such experiences remain largely understudied. Few studies have addressed how women emotionally process and internalize violence in culturally specific ways, and how their coping strategies may be constrained by limited access to mental health care, financial autonomy, or social support. This lack of research represents a critical gap in clinical psychology, where the understanding of culturally embedded responses is essential for designing effective, gender-sensitive interventions.

1.4 Externalizing psychological responses among men

The empirical literature increasingly highlights the role of gender in shaping psychological responses to violence. In the case of men, exposure to violence – particularly intimate partner violence (IPV) or other interpersonal forms – has frequently been linked to externalizing behavioral patterns, including alcohol consumption, aggression, impulsivity, and risk-taking behaviors (29, 34, 35). However, beyond the clinical and behavioral dimensions, it is crucial to situate these responses within broader sociocultural dynamics. In Latin American contexts, cultural constructions of masculinity emphasize stoicism, emotional control, and the rejection of vulnerability (9). Such expectations discourage men from expressing psychological suffering or seeking professional help, thereby reinforcing reliance on alcohol or other substances as socially “acceptable” coping strategies. This cultural reinforcement is particularly salient in Ecuador, where alcohol consumption is both widespread and normalized among men (3).

These gender role expectations deepen the dynamic, as masculinity in Latin America – and particularly in Ecuador – is socially defined through ideals of strength, emotional restraint, and self-reliance, which discourage men from acknowledging psychological suffering (9). This cultural framing positions alcohol use as a legitimate outlet for distress, while simultaneously stigmatizing the pursuit of psychological care (36). The result is a social reinforcement loop in which violence-related distress is externalized through substance use and impulsivity rather than addressed through adaptive or therapeutic pathways. From a clinical psychology perspective, this underlines the difficulty of detecting men’s psychological suffering, as it is masked by behaviors socially coded as “normal” or even expected. Neurobiological findings can enrich this understanding by illustrating how stress and violence exposure modulate reward-related circuits, thereby increasing susceptibility to maladaptive coping strategies (22, 37). Nevertheless, (21, 38) emphasizes, biological predispositions alone cannot explain men’s coping patterns; they interact continuously with sociocultural norms that dictate what is considered acceptable male behavior when responding to violence. In the Ecuadorian setting, where alcohol consumption is widespread and normalized, these intertwined cultural and biological mechanisms complicate both the recognition and the treatment of violence-related psychopathology.

1.5 Objectives

This study seeks to fill an important research gap by examining the gender-differentiated psychological consequences of exposure to violence in Ecuador, a country marked by one of the highest prevalence rates of gender-based violence in Latin America and significant institutional and socioeconomic disparities (12, 16). Whereas prior research has extensively documented the health and social costs of violence in Western settings, much less is known about its psychological impact in non-Western contexts, particularly in Ecuador, where structural inequalities and limited access to mental health care exacerbate vulnerability.

By adopting a clinical psychology perspective and a gender-sensitive lens, this study aims to clarify how men and women differ in their emotional responses to violence. Specifically, it focuses on the externalizing patterns often observed in men, such as alcohol consumption, and the internalizing patterns more frequent among women, such as depressive symptoms and emotional distress. This dual focus not only contributes to theory-building in gendered violence exposure responses but also provides contextually grounded insights for clinical interventions in Ecuador.

Finally, guided by the ecological and gendered frameworks outlined above, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Among individuals living in Ecuador, men exposed to violence will show higher levels of externalizing symptoms (alcohol dependence, substance use, impulsivity), whereas women exposed to violence will show higher levels of internalizing symptoms (depressive symptoms, perceived stress, loneliness), compared to non-exposed individuals of the same gender.

2 Methods

2.1 Dataset representative of the Ecuadorian population

The target population for this research comprised Ecuadorian adults spanning an age range of 18 to 80 years, encompassing both sexes. The study is based on a national mental health survey whose protocol and questionnaire were originally designed and piloted in 2019, with the aim of capturing psychological, social, and behavioral variables in the Ecuadorian adult population.

A total of 16,074 individuals were recruited via various virtual channels, including email invitations distributed after webinars organized in observance of World Mental Health Day. Additional participants were reached through public announcements by governmental and educational institutions, with the explicit support of Ecuador’s Ministry of Public Health.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) being between 18 and 80 years of age, (b) residing in Ecuador at the time of the survey, (c) being able to read Spanish, and (d) providing informed consent. Individuals who did not meet the age criteria or who declined consent were not allowed to proceed with the questionnaire. The online platform was configured with compulsory-response items for the principal study variables, so that questionnaires could not be submitted with missing responses on the instruments included in the present analyses. As a result, no cases were excluded due to item-level missing data, and the final analytical sample comprised 16,074 unique respondents. In addition, access links were individualized and monitored by the research team and clinical psychologists from the Ministry of Public Health, which prevented duplicate submissions and ensured the integrity of the dataset.

2.2 Procedure

Ethical approval for this study was granted in August 2021 by the Research Ethics Committee on Human Subjects at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito (CEISH code: 2021-072E). Further endorsement was obtained from the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador. The research strictly adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (39). All research instruments and the resulting database were securely maintained on an institutional server at the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL), configured to ensure data protection and compliance with prevailing ethical and technical standards.

Data collection was implemented between October 2021 and February 2022 through a digital platform (ArcGIS system) specifically designed for this project. Data collection in the primary care and community settings was carried out and supervised by trained clinical psychologists from the Ministry of Public Health, who were responsible for verifying the correct administration of the questionnaire and the completeness of responses. This platform hosted a meticulously curated set of questionnaires, selected based on three rigorous criteria: conciseness, demonstrated psychometric robustness, and accessibility for research purposes. Upon initial access to the platform, all participants were comprehensively informed of the study’s objectives and subsequently provided digital informed consent.

The sample is predominantly composed of young adults, with an average age of 30.91 years (SD = 10.05). Gender distribution is relatively balanced, with 8,546 men (53.17%) and 7,528 women (46.83%). Regarding marital status, the majority (54.33%) reported being single, followed by 33.13% married, 6.91% separated, 5.21% divorced, and 0.43% other. Employment status was varied: full-time employees represented 55.98% of respondents, unemployed 27.68%, part-time employees 8.61%, and informal workers 7.73%.

A key focus of the study is the impact of violence. Among the participants, 866 individuals (5.39%) reported having experienced violence, whereas 15,208 (94.61%) did not report any violence exposure. Regarding suicidal ideation, the data indicate that 15.62% of respondents have felt that life has no meaning, 3.06% have thought about committing suicide, and 0.51% have attempted suicide. The vast majority (80.81%) reported no suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

2.3 Measurement

This section outlines the measurement of the key constructs used in our study.

Exposure to violence: Exposure to violence was assessed through a dichotomous item in which participants reported whether they had ever experienced violence.

Sociodemographic factors: Gender was recorded as male or female. Additional sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, marital status, employment situation, subjective social class, and sleep patterns, were collected to contextualize the analyses and serve as control variables where relevant.

Psychological and behavioral consequences of violence: Mental health and behavioral outcomes were assessed with validated international instruments frequently used in clinical psychology research:

-

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT): A 10-item scale developed by the World Health Organization to identify hazardous, harmful, or dependent alcohol use (25). Total scores range from 0 to 40. We used the Ecuadorian Spanish adaptation of AUDIT (40).

-

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10): A 10-item instrument measuring the perception of stress, rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress (41). We employed the Spanish version whose psychometric properties have been confirmed in Ecuadorian samples (42).

-

UCLA Loneliness Scale – Short version (UCLA-3): A 3-item measure assessing subjective feelings of loneliness, with scores from 0 to 9 (43).

-

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-7): Measures psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance; higher scores indicate greater inflexibility (44). Psychological inflexibility was assessed using the Spanish adaptation whose factorial structure and reliability have been documented in Ecuadorian and other Spanish-speaking populations (e.g., 40).

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A 9-item screening tool for depression assessing symptom frequency over the last two weeks (45). We used the Spanish version validated in Ecuadorian college students (46), which has shown good internal consistency and an appropriate hierarchical factor structure.

-

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11): Evaluates impulsivity, with higher scores reflecting greater impulsiveness (47). We relied on the Spanish version, which has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in Latin American samples (e.g., 48).

Substance use beyond alcohol: was measured using selected items from the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), which evaluates frequency of use across multiple substances (e.g. tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines or other stimulants, inhalants, tranquilizers or sleep medications, hallucinogens, opiates, and other substances not otherwise specified). We used the Spanish-language version following World Health Organization recommendations and previous applications in Latin American populations. Taken together, the use of these Spanish-language instruments (we used the Ecuadorian Spanish adaptation of AUDIT (40)) ensures the linguistic and cultural adequacy of the measures employed, thereby supporting the cross-cultural validity of the present findings.

2.4 Data processing

To strengthen causal inference in this observational study, we employed Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to estimate the association between violence exposure and psychological outcomes. This method allows us to approximate counterfactual conditions by pairing individuals exposed to violence (treatment group) with comparable individuals unexposed to violence (control group), based on observable covariates (49, 50). In our case, this is crucial given that violence is not randomly distributed across the population but shaped by sociodemographic and economic conditions. We focus specifically on estimating the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET), which captures the net psychological impact of violence among those exposed.

Although the observational design of this study precludes definitive causal inference, PSM enhances the robustness of our findings by reducing selection bias. PSM was conducted separately for men and women, using a nearest-neighbor algorithm (nn = 1). The propensity score was estimated through a probit model in which exposure to violence (yes/no) was regressed on a set of sociodemographic covariates: age, marital status, employment status, subjective social class, and sleep duration. These variables were selected a priori based on their documented association with both violence exposure and mental health outcomes.

To ensure adequate common support, observations with propensity scores outside the overlapping region between exposed and non-exposed participants were discarded before matching. We implemented 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement and used robust standard errors to estimate the ATET for each outcome.

Post-matching diagnostics indicated good covariate balance (standardized differences < 0.05, variance ratios ≈ 1.0), suggesting the comparability of treatment and control groups. This allows us to more reliably estimate the gender-specific psychological effects of violence (51).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

This study examines a range of psychological, social, and behavioral factors to explore the impact of violence on mental health outcomes. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for the key variables analyzed in this study. These descriptive statistics are not only informative in themselves but also provide essential context for interpreting gendered analyses of violence exposure presented in subsequent sections.

Table 1

| Number | Variable name | Mean | Std. Dev. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 30.9 | 10.05 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Subjective social class | 5.5 | 1.56 | 0.06* | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Fear of losing job- | 32.1 | 33.05 | 0.06* | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Sleep | 6.3 | 2.42 | 0.16* | 0.15* | −0.05* | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Tobacco | 0.4 | 0.86 | −0.01 | 0.02* | 0.04* | −0.04* | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Alcohol | 1.0 | 0.83 | −0.07* | 0.05* | 0.05* | −0.04* | 0.40* | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | Cannabis | 0.1 | 0.37 | −0.09* | 0.01 | 0.02* | −0.05* | 0.22* | 0.23* | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | Cocaine | 0.02 | 0.19 | −0.02* | −0.003 | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.15* | 0.12* | 0.40* | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Amphetamines or other stimulants | 0.02 | 0.23 | −0.02* | 0.003 | 0.02* | −0.03* | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.30* | 0.55* | 1 | |||||||||||

| 10 | Inhalants | 0.1 | 0.36 | −0.05* | −0.003 | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.08* | 0.09* | 0.17* | 0.34* | 0.30* | 1 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Tranquilizers or sleep medications | 0.2 | 0.58 | −0.01 | 0.004 | 0.07* | −0.14* | 0.11* | 0.10* | 0.18* | 0.22* | 0.26* | 0.13* | 1 | |||||||||

| 12 | Hallucinogens | 0.02 | 0.19 | −0.04* | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02* | 0.13* | 0.09* | 0.42* | 0.69* | 0.59* | 0.37* | 0.25* | 1 | ||||||||

| 13 | Opiates | 0.01 | 0.18 | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.12* | 0.09* | 0.35* | 0.66* | 0.57* | 0.33* | 0.25* | 0.71* | 1 | |||||||

| 14 | Other substances not otherwise specified | 0.04 | 0.33 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.02* | −0.04* | 0.04* | 0.04* | 0.19* | 0.32* | 0.28* | 0.19* | 0.23* | 0.36* | 0.38* | 1 | ||||||

| 15 | AUDIT | 4.1 | 4.93 | −0.12* | 0.01 | 0.04* | −0.07* | 0.37* | 0.62* | 0.22* | 0.15* | 0.09* | 0.12* | 0.11* | 0.11* | 0.09* | 0.05* | 1 | |||||

| 16 | Perceived stress PSS |

14.8 | 7.45 | −0.31* | −0.07* | 0.13* | −0.37* | 0.04* | 0.07* | 0.11* | 0.05* | 0.07* | 0.05* | 0.23* | 0.06* | 0.05* | 0.09* | 0.15* | 1 | ||||

| 17 | Loneliness UCLA | 2.9 | 2.49 | −0.22* | −0.05* | 0.09* | −0.25* | 0.07* | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.07* | 0.08* | 0.05* | 0.19* | 0.07* | 0.07* | 0.10* | 0.19* | 0.58* | 1 | |||

| 18 | Cognitive inflexibility AAQ | 17.4 | 10.59 | −0.29* | −0.06* | 0.12* | −0.29* | 0.05* | 0.11* | 0.13* | 0.06* | 0.09* | 0.05* | 0.24* | 0.07* | 0.06* | 0.11* | 0.19* | 0.71* | 0.72* | 1 | ||

| 19 | PHQ | 5.7 | 6.55 | −0.31* | −0.06* | 0.12* | −0.36* | 0.08* | 0.13* | 0.16* | 0.09* | 0.11* | 0.06* | 0.29* | 0.11* | 0.10* | 0.12* | 0.20* | 0.67* | 0.67* | 0.78* | 1 | |

| 20 | BIS | 62.3 | 9.93 | −0.25* | −0.06* | 0.10* | −0.28* | 0.11* | 0.14* | 0.16* | 0.09* | 0.08* | 0.08* | 0.17* | 0.09* | 0.07* | 0.09* | 0.22* | 0.58* | 0.47* | 0.55* | 0.57* | 1 |

Mean and correlation matrix.

*p<0.05.

The sample was composed of 16,073 adults with a relatively young profile (M = 30.91, SD = 10.05) and a balanced gender distribution. Most respondents located themselves in the middle socioeconomic tier (M = 5.46, SD = 1.56). These baseline indicators highlight the diversity of demographic backgrounds in the dataset and provide a foundation for examining psychological outcomes related to violence.

Substance use behaviors, assessed using the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), revealed consistent patterns of comorbidity: individuals reporting one form of substance use were significantly more likely to report others. Alcohol consumption, assessed by the AUDIT, emerged as the most prevalent and showed positive associations with multiple substance categories, confirming its central role in maladaptive coping strategies within the Ecuadorian context. In terms of psychological functioning, mean scores on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS = 14.79, SD = 7.45), the UCLA Loneliness Scale (M = 2.91, SD = 2.49), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 = 5.68, SD = 6.55) indicated moderate but clinically relevant levels of stress, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Cognitive inflexibility, captured by the AAQ (M = 17.43, SD = 10.59), further highlighted the prevalence of maladaptive coping among participants.

Correlation analyses (Table 1) confirmed strong associations between substance use and psychological distress, with alcohol use in particular showing consistent links to stress, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Age negatively correlated with these mental health indicators, underscoring the vulnerability of younger individuals to adverse psychological outcomes when exposed to violence.

These descriptive statistics highlight the psychological vulnerabilities prevalent in the Ecuadorian population, particularly among younger individuals and those involved in substance use, and lay the groundwork for the gender-disaggregated Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analyses presented in the following subsections (3.1 for men, 3.2 for women, and 3.3 for comparative interpretation). Unless otherwise specified, the percentages reported in parentheses for PSM results refer to the relative difference between individuals exposed to and unexposed to violence in the matched sample, calculated as the ATET divided by the mean outcome among matched controls multiplied by 100.

3.2 Psychological impact of violence among men

The psychological consequences of violence are particularly pronounced among men, with consistent increases across substance use, alcohol consumption, psychological distress, and impulsivity. Men who have been exposed to violence show systematically higher likelihoods of engaging in externalizing behaviors, including alcohol misuse and illicit drug use, compared to non-exposed men.

The most striking difference is observed in alcohol use (AUDIT), which increases by 3.81 points (a relative increase of 93.6% with respect to matched controls), compared to a 41.1% increase among women.

Men also exhibit higher levels of psychological distress. Depressive symptoms increase by 5.62 points (45% relative increase), perceived stress (PSS) rises by 4.59 points (31% relative increase), and cognitive inflexibility (AAQ) increases by 8.51 points (48.8% relative increase), indicating marked emotional dysregulation and reduced adaptive flexibility.

In terms of substance use, tobacco consumption increases by 37%, while alcohol use rises by 33.3%. Men exposed to violence are also significantly more likely to use illicit drugs compared to women, with cannabis use increasing by 26.3% and amphetamine use by 17.2%. Additional increases are also observed for cocaine, inhalants, tranquilizers, hallucinogens, and opiates, reinforcing the pattern of polysubstance use among men exposed to violence.

In addition, impulsivity (BIS) increases by 6.15 points (41% relative increase), compared to 4.13 points (29.5% relative increase) in women, reinforcing a greater likelihood of externalizing behaviors among men.

3.3 Psychological impact of violence among women

Table 2 presents the estimated Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) for various psychological outcomes, separately for women and men. Among women who have experienced violence, significant differences are observed in substance use, perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity.

Table 2

| Outcome variable | Women |

|---|---|

| tobacco | 0.208 (SE = 0.042) [0.125, 0.291] |

| alcohol | 0.225 (SE = 0.045) [0.136, 0.313] |

| cannabis | 0.086 (SE = 0.023) [0.040, 0.131] |

| cocaine | 0.014 (SE = 0.009) [–0.003, 0.032] |

| amphetamines or other stimulants | 0.058 (SE = 0.018) [0.023, 0.093] |

| inhalants | 0.025 (SE = 0.018) [–0.010, 0.061] |

| tranquilizers or sleep medications | 0.225 (SE = 0.041) [0.145, 0.305] |

| Hallucinogens | 0.038 (SE = 0.012) [0.014, 0.062] |

| opiates | 0.010 (SE = 0.008) [–0.005, 0.025] |

| other substances | 0.109 (SE = 0.028) [0.054, 0.165] |

| AUDIT | 1.737 (SE = 0.244) [1.258, 2.215] |

| PSS | 4.240 (SE = 0.350) [3.554, 4.926] |

| UCLA | 1.313 (SE = 0.129) [1.060, 1.566] |

| AAQ | 6.562 (SE = 0.557) [5.470, 7.655] |

| PHQ | 3.682 (SE = 0.364) [2.968, 4.395] |

| BIS | 4.127 (SE = 0.469) [3.207, 5.047] |

Psychological outcomes among women exposed to violence (PSM estimates).

The first column lists the psychological and behavioral outcome variables analyzed in the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) models. The second column reports the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) for women exposed to violence compared to non-exposed counterparts. Estimates are presented as effect sizes, with their standard errors (SE) and 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Women who have been exposed to violence show a substantial increase in psychological distress compared to their non-exposed counterparts. Specifically, perceived stress (PSS) increases by 4.24 points, representing a 28.7% rise relative to the control group. Similarly, depressive symptoms (PHQ) increase by 3.68 points, translating to a 35.7% increase in depressive symptomatology. In addition to stress and depression, women exposed to violence also report higher levels of loneliness (UCLA), with an increase of 1.31 points, or 45%. Similarly, cognitive inflexibility (AAQ), a psychological marker associated with maladaptive stress responses, increases by 6.56 points, or 37.7%, which may indicate difficulties in adapting to violent experiences and regulating emotional responses.

Substance use patterns among women also change after exposure to violence. Alcohol consumption increases by 22.5%, while tobacco use increases by 20.8%. Additionally, the use of tranquilizers rises by 22.5%, which may indicate self-medication as a coping strategy. However, the use of illicit drugs such as cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamines remain relatively low, with changes ranging between 1.4% and 10.9%., indicating that while some women resort to illicit substances, the most common coping mechanisms remain alcohol and prescription sedatives.

Impulsivity and risk-taking behavior, as measured by the BIS scale, also show a 4.13-point increase (29.5% relative increase) among women exposed to violence.

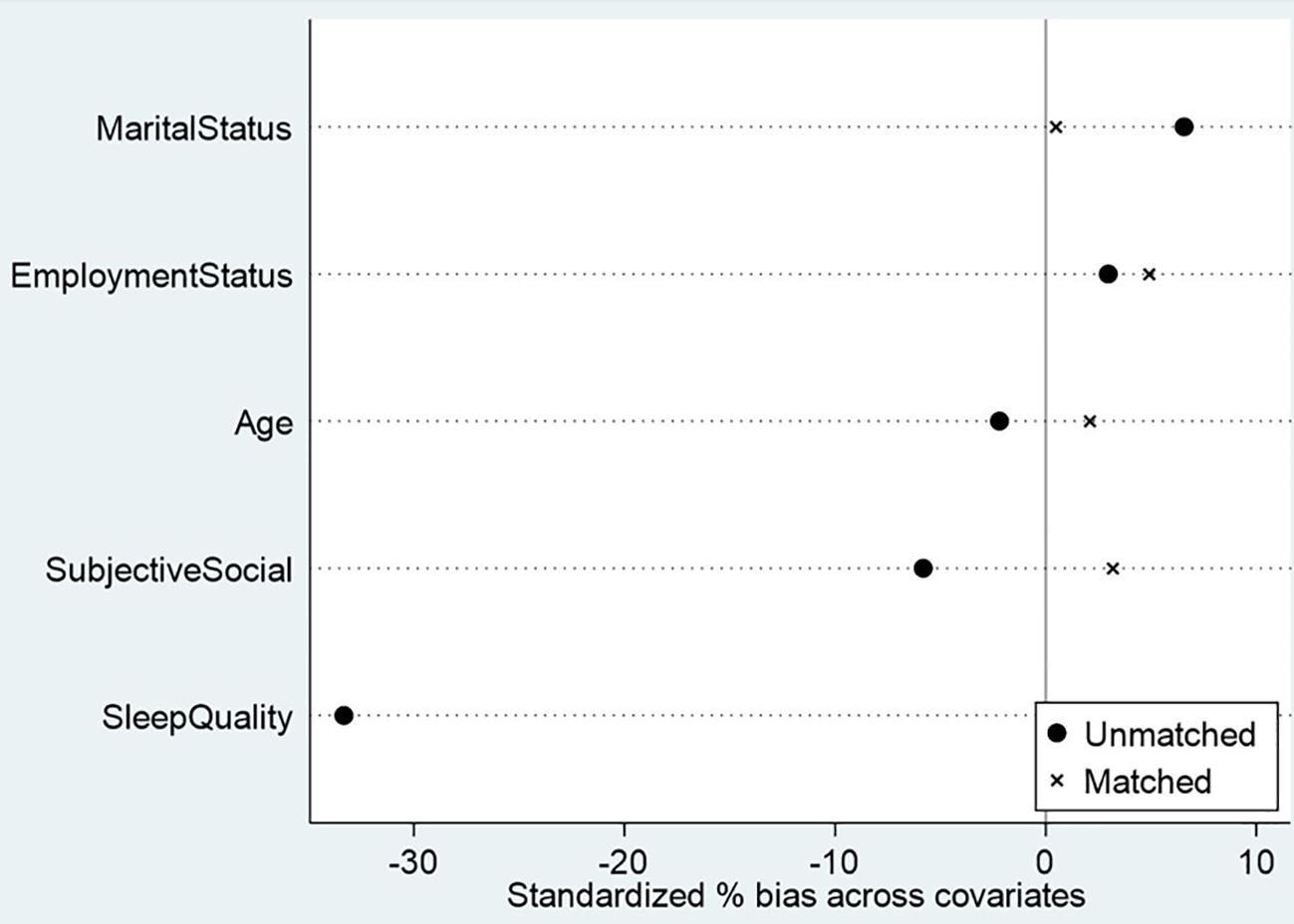

Before estimating the psychological effects of violence, we evaluated the quality of the propensity score matching procedure separately for men and women (Figures 1, 2). Figures 1, 2 present the covariate balance (love plots) before and after matching. In both groups, several covariates displayed substantial standardized mean differences prior to matching- particularly subjective social status, sleep quality, and employment status. After matching, however, the standardized biases for all covariates were reduced to below 5%, indicating excellent balance and confirming that the matched samples are highly comparable. This ensures that the estimated treatment effects reported in Tables 2, 3 are unlikely to be driven by baseline differences and can therefore be interpreted as robust estimates of the psychological impact of violence.

Table 3

| Outcome variable | Men |

|---|---|

| tobacco | 0.370 (SE = 0.114) [0.147, 0.592] |

| alcohol | 0.333 (SE = 0.096) [0.146, 0.521] |

| cannabis | 0.263 (SE = 0.058) [0.150, 0.376] |

| cocaine | 0.172 (SE = 0.050) [0.075, 0.269] |

| amphetamines or other stimulants | 0.172 (SE = 0.048) [0.078, 0.266] |

| inhalants | 0.208 (SE = 0.053) [0.103, 0.312] |

| tranquilizers or sleep medications | 0.376 (SE = 0.067) [0.245, 0.507] |

| Hallucinogens | 0.189 (SE = 0.049) [0.093, 0.285] |

| opiates | 0.136 (SE = 0.047) [0.044, 0.228] |

| other substances | 0.167 (SE = 0.052) [0.064, 0.269] |

| AUDIT | 3.807 (SE = 0.666) [2.502, 5.112] |

| PSS | 4.599 (SE = 0.592) [3.439, 5.759] |

| UCLA | 2.009 (SE = 0.231) [1.556, 2.461] |

| AAQ | 8.513 (SE = 0.934) [6.682, 10.345] |

| PHQ | 5.617 (SE = 0.606) [4.429, 6.804] |

| BIS | 6.154 (SE = 0.807) [4.572, 7.736] |

Psychological outcomes among men exposed to violence (PSM estimates).

The first column lists the psychological and behavioral outcome variables analyzed in the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) models. The second column reports the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) for men exposed to violence compared to non-exposed counterparts. Estimates are presented as effect sizes, with their standard errors (SE) and 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Figure 1

Covariate balance before and after propensity score matching (men).

Figure 2

Covariate balance before and after propensity score matching (women).

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of main findings

This study demonstrates that exposure to violence is associated with profound psychological consequences, but these consequences manifest differently according to gender.

For men, the results indicate a pattern of externalization, characterized by higher levels of alcohol use, illicit substance use, and impulsivity. These outcomes are consistent with the self-medication hypothesis, which posits that individuals may rely on substances as a maladaptive coping strategy following violence exposure (27, 30). Our findings extend this literature by demonstrating that, even after balancing covariates with PSM, violence-exposed men in Ecuador present a clear externalizing profile, particularly through alcohol misuse, an element strongly embedded in regional masculine norm.

For women, in contrast, the findings point to a pattern of internalization, marked by elevated symptoms of depression, heightened stress, loneliness, and cognitive rigidity. These results align with research indicating that women exposed to intimate partner violence are at heightened risk of developing affective disorders and social withdrawal (13, 18). Consistent with emotion-focused coping models, our results suggest that women’s affective vulnerability and social disconnection function as key pathways through which violence affects mental health.

Taken together, the psychological sequelae of violence are multidimensional, involving both behavioral dysregulation and emotional suffering, and gender-specific pathways mediate these outcomes. This divergence between externalizing and internalizing profiles underscores the importance of considering gender not merely as a control variable but as a central determinant in shaping the psychological impact of violence.

4.2 Interpretation and theoretical integration

These results reinforce and extend several frameworks in clinical and social psychology. First, the pattern observed among men is consistent with the self-medication hypothesis, which posits that individuals use psychoactive substances to regulate post-traumatic affect and dysphoria (26, 27). In our data, men exposed to violence display a markedly higher propensity toward alcohol problems (as indexed by AUDIT; 25) and greater impulsivity (47). Crucially, in the Ecuadorian and broader Andean context, alcohol consumption is socially normalized among men and often embedded in masculine identity rituals (e.g., party, community labor mingas). This cultural acceptance likely amplifies the externalizing trajectory observed in our male sample.

Second, the gendered divergence between externalizing (men) and internalizing (women) profiles aligns with stress-coping models and evidence on violence responses. Women exposed to violence show elevated depressive symptoms and perceived stress in numerous cohorts, and ruminative styles exacerbate these outcomes. The heightened loneliness and cognitive rigidity observed in Ecuadorian women may also reflect local structural barriers, including economic dependency and limited access to formal help-seeking services.

Third, our interpretation bridges clinical mechanisms with structural determinants. Women’s mental-health burden is frequently compounded by coercive control, economic abuse, and constrained help-seeking, which intensify and prolong distress (4, 8). In Ecuador and the Andean region, high prevalence of intimate partner violence, combined with persistent gendered norms around caretaking and silence, may intensify internalizing symptoms. Consistent with this literature, our female subsample shows salient elevations in depressive affect, stress, and loneliness-markers of internalizing distress and social disconnection.

For men, the pattern fits with scholarship on gendered socialization: norms valorizing emotional restraint and self-reliance can inhibit disclosure and professional help-seeking. This intersects with Latin American constructs such as machismo, which encourage endurance and discourage emotional expression.

Thus, a clinically coherent picture emerges men’s outcomes map onto an externalizing pathway shaped by socio-cultural norms around alcohol and emotional suppression, whereas women’s outcomes reflect an internalizing pathway influenced by structural constraints, affective vulnerability, and social disconnection.

4.3 Practical implications

The gender-differentiated outcomes observed have important implications for mental health policy and clinical intervention design.

For men, interventions should prioritize substance use treatment. Programs integrating Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for addiction, trauma-informed motivational interviewing, and culturally adapted peer-support strategies may be particularly effective in Ecuador, where alcohol-based socialization is ubiquitous. Public health messaging should challenge harmful masculine norms that stigmatize emotional vulnerability.

For women, interventions should adopt a multilevel perspective. Programs must simultaneously address structural inequalities (economic dependency, coercive control), promote social reconnection, and provide gender-sensitive trauma therapy. Community-based interventions may mitigate isolation and promote supportive networks.

In both cases, violence-informed and gender-responsive care is essential, integrating cultural, structural, and psychological determinants of distress.

4.4 Limitations

Several limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional design precludes strong causal inference. Although PSM reduces observed confounding and substantially improved covariate balance (see Figures 1, 2), the study remains observational, and unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded.

Second, reliance on self-report may introduce bias, particularly for substance use among men. Third, regional cultural heterogeneity in Latin America may limit generalizability. Future studies should incorporate longitudinal designs and culturally grounded qualitative work to enrich understanding of gendered violence responses.

4.5 Future directions

Future research should examine temporal dynamics through longitudinal designs. Qualitative and mixed-methods approaches can illuminate how men and women narrate violence, cope with distress, and engage with help-seeking within specific cultural frameworks. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential for developing integrated interventions. Intersectional factors-ethnicity, rurality, sexual orientation, disability-should also be incorporated to refine understanding of violence consequences in Ecuador and the Andean region.

5 Conclusion

This study shows that violence has profound psychological consequences that manifest differently by gender. Men tend to externalize distress through alcohol consumption, substance use, and impulsivity, whereas women are more prone to internalizing responses such as depression, stress, and loneliness. These gender-specific pathways highlight how structural, cultural, and psychological processes jointly shape responses to violence.

Addressing these differentiated outcomes requires violence-informed and gender-sensitive, culturally informed, and violence-informed interventions that integrate clinical support with broader strategies to reduce economic dependency, social isolation, and harmful gender norms.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. VL: Data curation, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. We gratefully acknowledge the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja and Escuela Politécnica Nacional for its financial support, which made this research possible.

Acknowledgments

We also extend our sincere thanks to the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador for its valuable collaboration in data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Organisation mondiale de la Santé . World Health Organization (2024). Available online at: https://www.emro.who.int/fr/violence-injuries-disabilities/violence/ (Accessed February 5, 2025).

2

García-Moreno C Pallitto C Devries K Stöckl H Watts C Abrahams N . Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2019).

3

World Health Organization . Violencia contra la mujer (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (Accessed May 5, 2025).

4

Stark E . Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press (2007).

5

Burn SM . The psychology of sexual harassment. Teach Psychol. (2019) 46:96–103. doi: 10.1177/0098628318816183

6

Koposov R Isaksson J Vermeiren R Schwab-Stone M Stickley A Ruchkin V . Community Violence Exposure and School Functioning in Youth: Cross-Country and Gender Perspectives. Front Public Health. (2021) 9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.692402

7

Scarpa A . Community Violence Exposure in Young Adults. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. (2003) 4(3):210–27. doi: 10.1177/1524838003004003002

8

Adams AE Sullivan CM Bybee D Greeson MR . Development of the scale of economic abuse. Violence Against Women. (2008) 14:563–88. doi: 10.1177/1077801208315529

9

Brown E Scodellaro C . Les violences envers les populations vulnérables: des réciprocités complexes. Populations Vulnérables. (2023) 9. doi: 10.4000/popvuln.4327

10

Cepeda I Lacalle-Calderon M Torralba M . Measuring violence against women: A global index. J Interpersonal Violence. (2022) 37:NP18614–NP18638. doi: 10.1177/08862605211037424

11

Bott S Guedess A Mary G . Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean. In: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Washington, DC, United States: Pan American Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Available online at: https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/violence1.24-web-25-febrero-2014_0.pdf (Accessed February 5, 2025).

12

Lanchimba C Díaz-Sánchez JP Velasco F . Exploring factors influencing domestic violence: a comprehensive study on intrafamily dynamics. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1243558. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1243558

13

Ouellet-Morin I Fisher HL York-Smith M Fincham-Campbell S Moffitt TE Arseneault L . Intimate partner violence and new-onset depression: A longidutinal study of women’s childhood and adult histories of abuse. Depression Anxiety. (2015) 32:316–24. doi: 10.1002/da.22347

14

Lortkipanidze M Javakhishvili N Schwartz SJ . Mental health of intimate partner violence victims: depression, anxiety, and life satisfaction. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1531783. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1531783

15

Laz-Figueroa K Sánchez BRH García JCS Guevara-Viejó F Molina-Molina V . Gender-based violence and its relationship to the mental health of female university students. Front Sociology. (2025) 10:1597261. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1597261

16

INEC . Principales resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Relaciones Familiares y Violencia de Género contra las Mujeres - EMVIGMU. Quito, Ecuador: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). (2019) p. 2–77.

17

Sambuco N Bradley MM Lang PJ . Trauma-related dysfunction in the fronto-striatal reward circuit. J Affect Disord. (2021) 287:359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.043

18

Campbell JC . Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. (2002) 359:1331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

19

Bronfenbrenner U . The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Vol. 352Harvard University Press. (1979).

20

Tong P An IS . Review of studies applying Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory in international and intercultural education research. Front Psychol. (2024) 14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1233925

21

Campbell A . Sex differences in direct aggression: What are the psychological mediators? Aggression Violent Behav. (2006) 11:237–64. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2005.09.002

22

Raji H Dinesh S Sharma S . Inside the impulsive brain: a narrative review on the role of neurobiological, hormonal and genetic factors influencing impulsivity in psychiatric disorders. Egyptian J Neurology Psychiatry Neurosurg. (2025) 61:4. doi: 10.1186/s41983-024-00930-9

23

Stylianou AM . Economic abuse within intimate partner violence: A review of the literature. Violence Victims. (2018) 33:3–22. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.33.1.3

24

Dichter ME Thomas KA Crits-Christoph P Ogden SN Rhodes KV . Coercive control in intimate partner violence: Relationship with women’s experience of violence, use of violence, and danger. Psychol Violence. (2018) 8:596–604. doi: 10.1037/vio0000158

25

Babor TF Higgins-Biddle JC Saunders JB Monteiro MG . The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2001).

26

Khantzian EJ . The theory of self-medication and addiction. Psychiatr Times. (2017) 34.

27

Schimmenti A Billieux J Santoro G Casale S Starcevic V . A trauma model of substance use: Elaboration and preliminary validation. Addictive Behav. (2022) 134:107431. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107431

28

Kovács LN Takacs ZK Tóth Z Simon E Schmelowszky Á Kökönyei G . Rumination in major depressive and bipolar disorder – a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2020) 276:1131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.131

29

Stark L Seff I Mutumba M Fulu E . Intimate partner violence and mental health: deepening our understanding of associations, pathways, and prevention in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021505

30

Khantzian EJ . The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. (1997) 4:231–44. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550

31

Scott-Storey K O’Donnell S Ford-Gilboe M Varcoe C Wathen N Malcolm J et al . What about the men? A critical review of men’s experiences of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2023) 24:858–72. doi: 10.1177/15248380211043827

32

Barbier A Lefèvre T . Femmes victimes de violence conjugale en France: estimation de la prévalence des violences et de la divulgation des faits à un tiers, facteurs associés et comparaison à la population consultant en médecine légale. J Du Droit la Santé l’Assurance - Maladie (JDSAM) N°. (2022) 30:35–44. doi: 10.3917/jdsam.213.0035

33

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. OSCE-led survey on violence against women: Main report. OSCE Secretariat. (2019). https://www.osce.org/sites/default/files/f/documents/2/1/424979_0.pdf

34

Hamby SL . Measuring gender differences in partner violence: implications from research on other forms of violent and socially undesirable behavior. Sex Roles. (2005) 52:725–42. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-4195-7

35

Oesterle DW Eckhardt CI Parrott DJ . Impulsivity and reactive-proactive aggression as mechanisms of alcohol-related sexual intimate partner violence perpetration among romantic partners. Subst Use Misuse. (2023) 58:1761–70. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2023.2247074

36

Camacho-Ruiz JA Galvez-Sánchez CM Galli F Limiñana Gras RM . Patterns and challenges in help-seeking for addiction among men: A systematic review. J Clin Med. (2024) 13. doi: 10.3390/jcm13206086

37

Seidemann R Duek O Jia R Levy I Harpaz-Rotem I . The reward system and post-traumatic stress disorder: does trauma affect the way we interact with positive stimuli? Chronic Stress. (2021) 5. doi: 10.1177/2470547021996006

38

Seidler ZE Dawes AJ Rice SM Oliffe JL Dhillon HM . The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2016) 49:106–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.002

39

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. (2013) 310(20):2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

40

López V Paladines B Vaca S Cacho R Fernández-Montalvo J Ruisoto P . Psychometric properties and factor structure of an Ecuadorian version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in college students. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0219618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219618

41

Cohen S Kamarck T Mermelstein R . Perceived stress scale. In: PsycTESTS DatasetWashington, DC: American Psychological Association (2014). doi: 10.1037/t02889-000

42

Ruisoto P López-Guerra VM Paladines MB Vaca SL Cacho R . Psychometric properties of the three versions of the Perceived Stress Scale in Ecuador. Physiol Behav. (2020) 224:113045. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113045

43

Hughes ME Waite LJ Hawkley LC Cacioppo JT . A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Res Aging. (2004) 26:655–72. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574

44

Levin ME Luoma JB Lillis J Hayes SC Vilardaga R . The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – Stigma (AAQ-S): Developing a measure of psychological flexibility with stigmatizing thoughts. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2014) 3:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.11.003

45

Kroenke K Spitzer RL Williams JBW . The PHQ-9. J Gen Internal Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

46

López-Guerra VM López-Núñez C Vaca-Gallegos SL Torres-Carrión PV . Psychometric properties and factor structure of the patient health questionnaire-9 as a screening tool for depression among Ecuadorian college students. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:813894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813894

47

Patton JH Stanford MS Barratt ES . Factor structure of the barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. (1995) 51:768–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::AID-JCLP2270510607>3.0.CO;2-1

48

Orozco-Cabal L Rodríguez M Herin DV Gempeler J Uribe M . Validity and reliability of the abbreviated Barratt impulsiveness scale in Spanish (BIS-15S)*. Rev Colombiana Psiquiatría. (2010) 39:93–109. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7450(14)60239-0

49

Rosenbaum PR Rubin DB . The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. (1983) 70:41. doi: 10.2307/2335942

50

Cameron C Trivedi P . Microeconometrics. Methods and applications. In: Jurnal Sains dan Seni ITS, vol. 6. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press (2005).

51

Austin PC . An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. (2011) 46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Summary

Keywords

alcohol, depression, Ecuador, gender differences, propensity score matching, psychological distress, violence

Citation

Lanchimba C, Courtois R and Lopez-Guerra VM (2026) Beyond violence exposure: gender-specific psychological responses to violence in Ecuador – a propensity score analysis. Front. Psychiatry 16:1716810. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1716810

Received

30 September 2025

Revised

26 November 2025

Accepted

19 December 2025

Published

26 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany

Reviewed by

Lizeth Ramón Jaramillo, Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, Mexico

Mamadou Ndione, Université de Bourgogne, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lanchimba, Courtois and Lopez-Guerra.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cintya Lanchimba, cintya.lanchimba@epn.edu.ec

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.