Abstract

Purpose:

To investigate the rehabilitative effects of modified psychomotor therapy (mPMT), which incorporates traditional Chinese healthcare exercises, on the self-efficacy, psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, and social functioning of individuals with schizophrenia during the community rehabilitation period.

Methods:

A total of 96 individuals with schizophrenia, who were being managed during community rehabilitation period at Yangpu District, were randomly and equally divided, using the simple random number method, into two groups: the intervention group (mPMT) and the control group (Control). The control group received routine community mental health services, including psychiatric medication, follow-up visits from the community family doctor teams, health education and routine community rehabilitation services, whereas the mPMT group received psychomotor therapy alongside these services above for a period of six months. The self-efficacy of individuals with schizophrenia was primarily assessed using the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES). Psychiatric symptoms, social disability and quality of life were respectively assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome (PANSS), the Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS) and the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS).

Results:

After six months, the within-group GSES scores were significantly higher in both the control and mPMT groups compared to the baseline scores (p < 0.0001), while the SQLS and SDSS scores were significantly lower (p < 0.001). After 6 months of intervention, PANSS, SQLS and SDSS scores were significantly lower in the mPMT group than in the control group (p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

mPMT serves as an effective complementary intervention to alleviate psychiatric symptoms, enhance self-efficacy, and improve the quality of life for individuals with schizophrenia in community rehabilitation.

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder characterized by cognitive dysfunction, which is a core symptom, as well as positive and negative symptoms (1). It is marked by fundamental changes in personality, fragmented thoughts, emotions, and actions, and a loss of coordination with the surrounding environment. These disturbances not only impair cognitive abilities but also diminish social functioning and self-efficacy—both of which are closely linked to patients’ long-term prognosis (2). According to the World Health Organization’s world mental health report 2022, nearly one billion people around the world suffer from a mental illness, which equates to one in eight people in the world experiencing mental health challenges. Epidemiological data indicate high relapse rates among individuals with psychotic disorders: 53.7 % relapse within two years and 81.9 % within five year (3). Recovery, especially within community settings, remains a formidable challenge, and China’s community-based mental health rehabilitation infrastructure is still underdeveloped, limiting many patients’ opportunities for normal family life and social reintegration (4). Therefore, the pressing issue is how to effectively assist patients with mental illness, who are permanent residents of the community, in enhancing their cognitive abilities and achieving improved social functioning and self-efficacy necessary for better daily living.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capability to perform specific behaviors. It is a pivotal determinant of daily functioning, social participation, and overall quality of life. While antipsychotic medication is essential for preventing relapse, long-term pharmacotherapy can adversely affect quality of life and does not fully restore social functioning or self-efficacy (5). Poor medication adherence and patients’ reluctance to continue oral treatment after symptom stabilization further contribute to relapse (6). Moreover, medication alone has limited impact on negative symptoms, quality of life, and social functioning (7, 8).

Research demonstrates that regular physical exercise promotes neural connectivity, thereby enhancing cognition and memory (9). Exercise also mitigates some of the adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs. Controlled physical activity has been shown to improve psychiatric symptoms, increase motivation for engagement, and encourage active participation in social activities among schizophrenia patients (10, 11). Ho et al. conducted their study in Hong Kong, China—a region combining Eastern cultural values and a mature Western-style mental health service system. The cultural context may have increased participants’ familiarity and willingness to engage in Tai Chi (a traditional Chinese practice), while the community setting reduced hospital-related barriers to consistent participation (12).

In addition to exercise, community-based therapies—such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills training, cognitive remediation, peer-support groups, and medication-adherence interventions—help patients cope with difficulties and facilitate societal reintegration (13–16). Yet these approaches are typically delivered in isolation, lacking a comprehensive mind-body integration. Therefore, a rehabilitation method integrating psychotherapy and exercise is needed.

Psychomotor Therapy (PMT) is a multidisciplinary, mind-body treatment that incorporates mental-state analysis, philosophy, neurology, neurophysiology, and cognitive neuropsychology (17). It aims to synchronize physical movement with mental activity, fostering connections between patients, others, and the environment. By viewing physical, mental, and social functions as an integrated whole, PMT employs techniques such as body-perception training to energize both body and mind for therapeutic and rehabilitative purposes (3). Haeyen’s systematic review recommended PMT for personality-disordered individuals, noting improvements in emotional regulation, stress management, and social functioning (18). Nonetheless, research on PMT’s impact on community psychiatric rehabilitation—particularly on self-efficacy—is scarce.

Therefore, the present study aims to utilize the mPMT, which incorporates traditional Chinese health-preserving exercises, to provide a 6-month intervention for individuals with schizophrenia during their community rehabilitation period. The goal is to assess their self-efficacy, negative and positive psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life, among other factors. The present study assumed that mPMT would be effective in improving self-efficacy and quality of life for individuals with schizophrenia during community rehabilitation period.

1 Methods

1.1 Participants

The study sample was drawn from patients who were currently residing in the Yangpu district during community rehabilitation period. Both patients and their guardians were fully informed before signing an informed consent form. The trial was approved by the ethics committee of Yangpu District Mental Health Center, Shanghai (Approval No. 2021-011).

The sample size was calculated using G*Power software. According to the results of the literature review, an increase of 3 in self-efficacy was categorized as effective. The mPMT group’s effectiveness rate was categorized as ρ1 = 0.75 and the control group’s as ρ2 = 0.40. The confidence level was categorized as α = 0.05, the certainty level as 1-β = 0.90 and the tolerance level as δ = 0.1. This resulted in a bilateral Z1-α/2 = 1.96 and Z1-β = 1.28. The required sample size was calculated to be 40 cases for each group. Based on an expected dropout rate of 20%, the required sample size is 48 cases per group for a total of 96 cases. The 96 patients were randomly and equally divided into control and mPMT groups using the random number table approach. Participants were unaware of their assigned number until the baseline assessment had been completed. The physicians involved in the assessment were trained in homogenization and were blinded to the trial grouping information to ensure an accurate assessment. A group of community workers and physicians contacted the subjects closely by telephone and home visits to improve their compliance.

Inclusion criteria: meet the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia of “International Classification of Diseases ICD-10”; discharge time < 2 years or disease duration <15 years; age 18~60 years old, junior high school or above, male or female; stable condition, able to communicate normally, and able to cooperate with the completion of the various experimental evaluations; did not undergo any other rehabilitation training in the 6 months prior to the entry into this study; and did not perform physical exercise regularly in the normal course of the day.

Exclusion criteria: those who do not meet the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia of “International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)”; those who do not meet the above inclusion criteria; those with severe skeletal and muscular system, neurological disease; those with drug addiction or abuse; those with psychotic episodes; those with critical conditions (e.g. severe cardiac insufficiency, serious infections, and tumors); those who refuse to be followed up, and those who are not able to independently complete all the above evaluations and rehabilitation training.

1.2 Intervention method

Both the intervention and control groups received routine community mental health services, including psychiatric medication, follow-up visits by community family doctor teams, health education and routine community rehabilitation services. The intervention group received mPMT alongside the above routine community mental health services for a total of 6 months (25 weeks). Each mPMT session lasted 90 minutes, consisting of three 30-minute modules: relaxed perception training (first 30 mins), Thematic Course (middle 30 mins), and relaxed perception training (last 30 mins). For the epidemic prevention-related training, there will be 3 sessions per week from Week 1 to Week 8 (combining online and offline methods) to ensure an 80% participation rate; 2 sessions in Week 9; and 1 session per week from Week 10 to Week 25 (also combining online and offline methods). For patients who cannot attend offline training, online training will be arranged as an alternative, and the overall training participation rate shall be no less than 75%. The detailed weekly curriculum is presented in Supplementary 1.

1.3 Assessment methods

1.3.1 General self-efficacy scale

The GSES consists of 10 items designed to assess an individual’s level of confidence in the face of frustration or adversity on a 4-point Likert scale (“not at all true”, “somewhat true”, “mostly true” or “completely true”) (19). The scale is scored as follows: 1 for “not at all correct,” 2 for “somewhat correct,” 3 for “mostly correct,” and 4 for “completely correct.” The GSES is a unidimensional scale, and only the total scale score is calculated. This total is obtained by summing the scores of all 10 items and then dividing by 10.

1.3.2 Positive and negative syndrome

The PANSS is used to measure the severity of symptoms in schizophrenia patients and to determine whether psychopathic symptoms are present (20). Psychiatrists are trained in the application of measurement and implement a comprehensive evaluation of the adult, taking into account information from the clinical examinations, family members, and other aspects of the patient’s life in order to ensure that the results are accurate and trustworthy. Typically, the evaluation consists of all patient information over a one-week period.

1.3.3 Social disability screening schedule

The SDSS is utilized to evaluate the extent of social disability among psychiatric patients (21). It comprises 10 items, each scored on a scale from 0 to 2: (0) signifies no significant functional impairment, (1) indicates significant functional impairment, and (2) denotes severe functional impairment. During the evaluation process, the evaluator needs to be professionally trained and spends 5–8 minutes on questioning. For some special cases, there may perhaps be exclusions, such as assessments 2 and 3 for unmarried people, which can be recorded in (9) and will not be counted in the overall score. According to the latest regulations, the assessment is limited to the last month. Each assessment requires 5–10 minutes. The SDSS assessment indicators encompass the total score and individual item scores. Based on the results of the national epidemiological survey on mental illness across twelve provinces, an individual scoring ≥ 2 is identified as having a social functioning disability. This threshold is also utilized in the China Disability Prevalence Survey to determine mental disability (22).

1.3.4 The schizophrenia quality of life scale

The SQLS is a scale developed in 1999 by British psychiatrists Greg Wilkinson and Dlane Wild to measure the quality of life of people with mental disorders so that they can better understand how they are living. The scale consists of 30 entries: 15 psychosocial subscales and 7 motivational/spiritual subscales reflecting emotional expression and interpersonal interactions as well as motivational and spiritual components, respectively. In addition, there are eight symptom/side effect subscales, which reflect the side effects of medication. Responses were scored on a five-point scale ranging from 0-4. The raw scores of this questionnaire were converted to a final standardized score of 0-100, where lower scores indicate a better subjective quality of life.

1.4 Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 statistical software was used for analysis. Continuous variables were tested for normality and homoscedasticity by Wilk’s test. Information on measures conforming to normal distribution was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄± s), inter- and intra-group comparisons were made by independent samples T-tests, and non-normal distributions were expressed as median (P25, P75), with non-normal distributions tested using the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test. Categorical data were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical results p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences.

2 Results

2.1 Baseline characteristics

Comparing the general information of the intervention and control groups, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of gender, education, medication use, marital status, family history, form of onset of the disease, proportion of psychiatric symptoms, age and duration of the disease. (Table 1).

Table 1

| Ctrl (n=48) | Intv (n=48) | Z/t/x2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristic | |||||

| Sex (n,%) | Male | 22 (45.8) | 23 (47.9) | 0.042 | 0.838 |

| Female | 26 (54.2) | 25 (52.1) | |||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 43.6 ± 5.7 | 44.7 ± 6.0 | 0.901 | 0.367 | |

| Education (n,%) | Junior High | 6 (12.5) | 8 (16.7) | 1.151 | 0.765 |

| Senior High | 17 (35.4) | 18 (37.5) | |||

| Associate | 13 (27.1) | 14 (29.2) | |||

| Bachelor+ | 12 (25.0) | 8 (16.7) | |||

| Marital (n,%) | Single | 26 (54.2) | 32 (66.7) | 1.806 | 0.386 |

| Married | 17 (35.4) | 11 (22.9) | |||

| Divorced | 5 (10.4) | 5 (10.4) | |||

| Family Hx (n,%) | N | 45 (93.8) | 44 (91.7) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Y | 3 (6.2) | 4 (8.3) | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Duration (Mean ± SD) | 2.0(2.0,4.0) | 4.0(2.0,7.0) | -2.006 | 0.045* | |

| Medication (n,%) | Monotherapy | 8 (16.7) | 9 (18.8) | 0.072 | 0.789 |

| Combination therapy | 40 (83.3) | 39 (81.2) | |||

| Onset (n,%) | Acute | 7 (14.6) | 6 (12.5) | 0.186 | 0.911 |

| Subacute | 16 (33.3) | 15 (31.2) | |||

| Chronic | 25 (52.1) | 27 (56.2) | |||

| Symptom Types (n,%) | 0 | 5 (10.4) | 9 (18.8) | 6.728 | 0.081 |

| 1 | 24 (50.0) | 12 (25.0) | |||

| 2 | 10 (20.8) | 16 (33.3) | |||

| 3+ | 9 (18.8) | 11 (22.9) | |||

| Support Group (n,%) | N | 13 (27.1) | 14 (29.2) | 0.052 | 0.821 |

| Y | 35 (72.9) | 34 (70.8) | |||

Baseline general population characteristics of the two groups.

Over the course of the 6-month intervention, there was a 12.5% dropout rate in the mPMT group, with 6 patients interrupting their training during psychomotor processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart.

2.2 Main outcome indicators

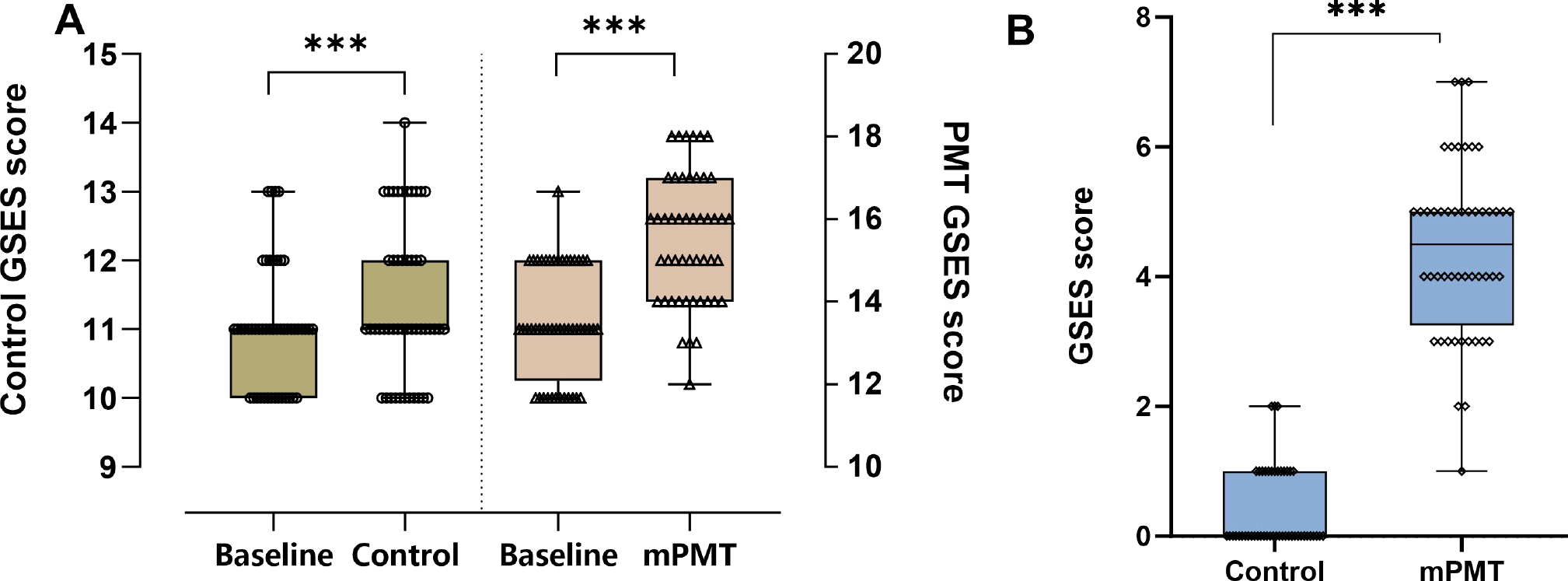

2.2.1 Effects of the mPMT intervention on self-efficacy

Self-efficacy directly affects behavioral choices, motivation, and emotional responses. GSES scale scores were significantly higher in the mPMT group compared to baseline after 6 months of mPMT intervention (z = 6.071, p < 0.0001) and in the control group compared to baseline after routine mental health services (z = 3.755, p < 0.0001). But the difference in GSES scale scores between the two groups was significantly higher in the mPMT group -4.42(95% CI, -4.8‐‐4.03) than in the control group -0.4 (95% CI, -0.57‐‐0.22)(Cohen’s d = 3.96; z = 8.553, p < 0.0001) (Figure 2). This suggests that mPMT therapy leads to greater improvements in patients’ self-efficacy.

Figure 2

Effect of mPMT intervention on GSES. (A) Intragroup comparison between the intervention and control groups, with the left y-axis showing GSES scores in the control group and the right y-axis showing GSES scores in the mPMT group; (B) Intergroup comparison between the intervention and control groups. ***p < 0.0001.

2.3 Secondary outcome indicators

2.3.1 Effects of mPMT intervention on PANSS, SDSS, SQLS

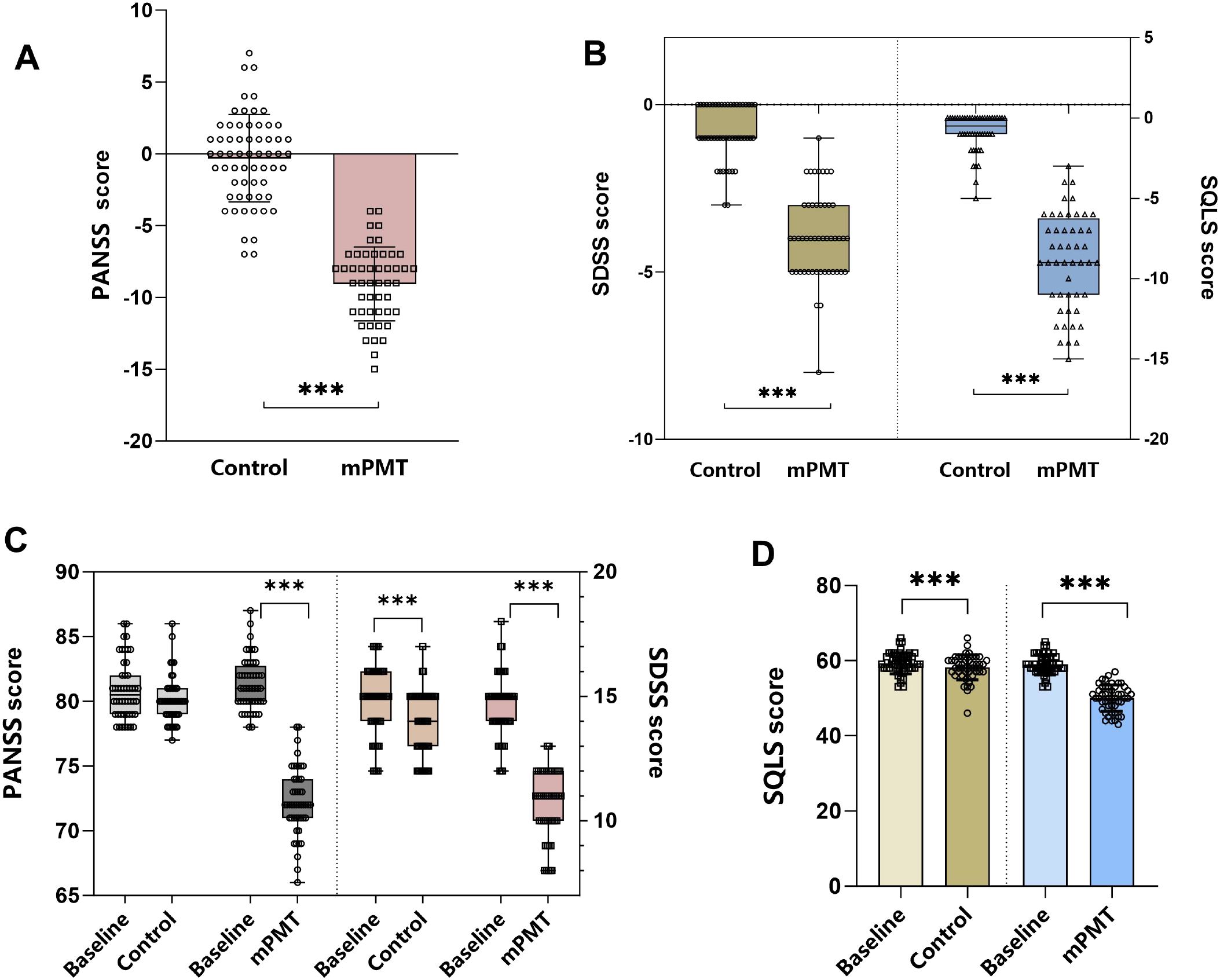

The PANSS was used to evaluate the severity of symptoms in different types of schizophrenia, and through the 6-month intervention, the total scores of the mPMT group were all significantly lower compared to baseline (z = -6.043, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3C), but there was no significant difference in the control group (z = -1.715, p = 0.086). Moreover, the mPMT group 9.06(95% CI,8.32-9.81) was more effective in reducing the degree of symptoms compared to the control group 0.77(95% CI, -0.08-1.62) (Cohen’s d = 3.15; z = -14.746, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

Secondary outcome indicators. (A) Comparison of the difference in PANSS scores between the control and mPMT groups; (B) Comparison of the difference in SDSS and SQLS scores between the control and mPMT groups; (C) Comparison of the PANSS and SDSS of the control and mPMT groups with the baseline data at 6 months post-intervention; (D) Comparison of the SQLS of the control and mPMT groups with the baseline data at 6 months post-intervention. ***p < 0.0001.

The SDSS scores were primarily used with psychiatric patients living in the community to assess the degree of impairment in social functioning in psychiatric patients. After 6 months of intervention, both the control group and the mPMT group showed a significant reduction from baseline (z = -4.813, p < 0.0001; z = -6.077, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3C). However, comparing the intervention effects between the two groups, it was found that the difference in SDSS scores was significantly lower in the mPMT group 3.94(95% CI, 3.55-4.32) than in the control group 0.81(95% CI, 0.57-1.06) (Cohen’s d = 2.9; z = -8.084, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3B). Therefore, the mPMT intervention had a more favourable impact on patients’ social functioning.

To assess whether patients’ quality of life improved after the intervention, we assessed the improvement in quality of life using the SQLS scale. Significant improvement in quality of life occurred in both the control and mPMT groups after the 6-month intervention (59.35 ± 2.82 vs. 58.48 ± 2.84; t = -5.145, p < 0.0001) VS (58.83 ± 2.64 vs. 49.94 ± 3.52; t = -20.318, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3D). Despite the improvement in quality of life in both groups, the mPMT group 8.9(95% CI, 8.02-9.78) remained significantly better than the control group 0.88(95% CI, 0.53-1.22), with a significant reduction in SQLS score (Cohen’s d = 3.52; z = -8.474, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3B). A significant negative correlation exists between GSES and SQLS (r = -0.287, p = 0.049), indicating that higher GSES correlates with better SQLS -where lower scores indicate higher quality of life.

3 Discussion

The novelty of mPMT lies in its incorporation of traditional Chinese health exercises, which are rooted in the concept of holistic mind-body unity. It is a specialized, body-mediated, and functionally re-engineered rehabilitation process designed to foster psychological adjustment. After 6 months of mPMT intervention, the self-efficacy and scores of all subscales in the mPMT group were significantly different compared with the pre-intervention period, suggesting that mPMT was able to improve the self-efficacy and quality of life of individuals with schizophrenia in the community rehabilitation period.

Self-efficacy and positive or negative coping styles as interlocking mediators in the relationship between psychological resilience and depression (10). The results of the study showed that compared with the control group, patients in the mPMT group showed significant improvement in their self-efficacy after 6 months of intervention with mPMT, suggesting that mPMT can effectively improve the self-efficacy of individuals with schizophrenia in the community rehabilitation period. The significant improvement in self-efficacy observed in the mPMT group can be effectively interpreted using Albert Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy. This theory posits that an individual’s belief in their capability to execute courses of action is built upon four primary sources: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological/affective states. The design of mPMT strategically incorporates elements that target these sources. The mPMT program, through its structured progression of exercises such as Tai Chi and Baduanjin, emphasizes motor coordination and relaxation, as well as aerobic exercises, which offer significant benefits in enhancing patients’ physical health, self-confidence, and sense of achievement. They can also motivate patients to participate in physical exercise more actively and improve their adherence to exercise (11). Tai Chi exercise significantly reduces motor disabilities and increases backward digit span and mean cortisol levels in patients (12). Baduanjin improves balance function, motor dual-task performance, and cognitive dual-task performance in individuals with schizophrenia (23). The improvement effect of Baduanjin on logical memory in long-term hospitalized individuals with schizophrenia was also significant (24).

The therapeutic benefits of mPMT extend beyond self-efficacy, exerting positive effects across multiple domains that are best understood within the Bio-psycho-social medical model. A meta-analysis by Vancampfort et al. (25)systematically demonstrated that exercise interventions significantly improve psychological, cognitive, and physical outcomes in people with mental disorders. In line with this, psychomotor rehabilitation builds upon the patient’s self-perception and integrates positive thinking techniques to facilitate cognitive and attitudinal shifts (26, 27). This process encourages a deeper self-understanding, helps patients identify personal strengths and limitations, and ultimately strengthens their self-awareness and belief in their own capabilities. Cognitive self-efficacy in individuals with schizophrenia is a person’s belief in his or her ability to use situational self-regulation, efficacy, and flexibility, as well as interpersonal and intrapersonal coping, and is an important predictor of social functioning (28). Moreover, aerobic exercise has been shown to improve responsiveness to external stimuli, boost cognitive performance, encourage community involvement, and support mental health, all of which contribute to better social functioning (29). From a neurobiological perspective, schizophrenia is associated with dysregulation in neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin and dopamine (30). Appropriate physical activity can modulate the release and availability of these neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft, leading to improved attentional control and facilitating more effective social communication (31). Furthermore, as negative symptoms diminish, neural connectivity among the prefrontal cortex, striatum, thalamus, and temporal lobe is strengthened, which enhances the brain’s capacity for information processing and emotional regulation (32, 33).

Community-based psychiatric rehabilitation serves as a crucial step in reintegrating home-treated patients into their families and society (34). Studies have shown that rehabilitation activities carried out in specialized centers significantly enhance patients’ medication adherence, daily living skills, and coping abilities. For example, a community-based Tai Chi intervention was found to reduce patients’ scores on the PANSS, decrease the risk of aggressive behavior, and lead to greater improvement in medication adherence one year after the intervention (35). Furthermore, diverse rehabilitation activities have enriched patients’ daily lives, with many valuing the friendships, sense of belonging, and self-worth gained during the process. However, this institution-centric rehabilitation model may, to some extent, slow down patients’ further integration into broader society (36). According to Maslow’s theory of needs, these patients have already met the needs of both physiological and safety levels, so the next goal is the need for belonging and respect. Yet due to constraints in staffing and space, rehabilitation centers are often unable to continuously meet all patients’ recovery needs.

This study has several limitations. First, the samples were geographically restricted to Yangpu District, Shanghai, with a small size (48 participants per group), and the participants were limited to patients with stable conditions, junior high school education or above, and good cooperation ability—failing to cover those with more severe conditions, lower educational levels, or poorer communication skills, which may affect result generalizability. Second, mPMT is a comprehensive intervention involving Taichi, Baduanjin, meditation, and breathing exercises, making it hard to identify the dominant effective component. Third, primary outcome measures such as GSES and SQLS relied on patient self-reports, which are prone to social desirability bias or subjective deviation.

Based on the findings and limitations of this study, several directions for future research are recommended. It is possible that the observed results were inflated by the increased level of care and interaction with medical personnel provided to the mPMT group, as such contact is a recognized beneficial factor in schizophrenia. Conducting comparative effectiveness trials, for instance, directly pitting mPMT against interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy or standard physical exercise, would help to better delineate its specific therapeutic benefits. Furthermore, longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods are needed to evaluate the long-term sustainability of the improvements in self-efficacy, social functioning, and symptom reduction. Finally, research exploring the differential effects of mPMT across various patient subgroups—such as the elderly, those with significant comorbidities, or individuals at different stages of illness—could help to identify which populations benefit most, thereby facilitating more personalized and effective rehabilitation strategies.

4 Conclusion

A comprehensive analysis indicates that a community-managed psychomotor intervention integrating elements of traditional Chinese healthcare exercise can significantly improve self-efficacy, social functioning, and psychotic symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia. These improvements subsequently enhance self-identity and quality of life, supporting the use of this intervention as an adjunctive therapy to pharmacotherapy in community healthcare.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Yangpu District Mental Health Center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HZ: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CC: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Investigation. YC: Formal Analysis, Resources, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JKH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WJ: Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SW: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The “Good Doctor” Construction Project of the Health and Wellness Work Committee of Yangpu District provides medical resources, The Project of the Institute of Mental Health, Yangpu District Mental Health Center, Shanghai (YJYQN202402) and The 2024 Pudong New Area Health System Outstanding Young Medical Talent Training Program (PWRq2024-20) provide publication fees and experimental funds.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1721293/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Takeda T Umehara H Matsumoto Y Yoshida T Nakataki M Numata S . Schizophrenia and cognitive dysfunction. J Med Invest. (2024) 71:205–9. doi: 10.2152/jmi.71.205

2

Cao X Chen S Xu H Wang Q Zhang Y Xie S . Global functioning, cognitive function, psychopathological symptoms in untreated patients with first-episode schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 313:114616. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114616

3

Navalón P Sahuquillo-Leal R Moreno-Giménez A Salmerón L Benavent P Sierra P et al . Attentional engagement and inhibitory control according to positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an emotional antisaccade task. Schizophr Res. (2022) 239:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.11.044

4

Zhu Y Li X Zhao M . Promotion of mental health rehabilitation in China: community-based mental-health services. Consort Psychiatr. (2020) 1:21–7. doi: 10.17650/2712-7672-2020-1-1-21-27

5

Jauhar S Johnstone M Mckenna PJ . Schizophrenia. Lancet. (2022) 399:473–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01730-X

6

Tréhout M Leroux E Bigot L Jego S Leconte P Reboursière E et al . A web-based adapted physical activity program (E-apa) versus health education program (E-he) in patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers: study protocol for A randomized controlled trial (Pepsy V@Si). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2021) 271:325–37. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01140-z

7

Marder SR Umbricht D . Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: newly emerging measurements, pathways, and treatments. Schizophr Res. (2023) 258:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2023.07.010

8

Kern RS Reddy LF Cohen AN Young AS Green MF . Effects of aerobic exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness and social functioning in veterans 40 to 65 years old with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 291:113258. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113258

9

Abbas MS Nassar ST Tasha T Desai A Bajgain A Ali A et al . Exercise as an adjuvant treatment of schizophrenia: A review. Cureus. (2023) 15:E42084. doi: 10.7759/cureus.42084

10

Wang L Li M Guan B Zeng L Li X Jiang X . Path analysis of self-efficacy, coping style and resilience on depression in patients with recurrent schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2023) 19:1901–10. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S421731

11

Nuechterlein KH Mcewen SC Ventura J Subotnik KL Turner LR Boucher M et al . Aerobic exercise enhances cognitive training effects in first-episode schizophrenia: randomized clinical trial demonstrates cognitive and functional gains. Psychol Med. (2023) 53:4751–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722001696

12

Ho RT Fong TC Wan AH Au-Yeung FS Wong CP Ng WY et al . A randomized controlled trial on the psychophysiological effects of physical exercise and tai-chi in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2016) 171:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.038

13

Taub S Krivoy A Whiskey E Shergill SS . New approaches to antipsychotic medication adherence - safety, tolerability and acceptability. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2022) 21:517–24. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1983540

14

Fitapelli B Lindenmayer JP . Advances in cognitive remediation training in schizophrenia: A review. Brain Sci. (2022) 12:149. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12020129

15

Chen Q Sang Y Ren L Wu J Chen Y Zheng M et al . Metacognitive training: A useful complement to community-based rehabilitation for schizophrenia patients in China. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:38. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03039-y

16

Stefancic A House S Bochicchio L Harney-Delehanty B Osterweil S Cabassa L . What we have in common”: A qualitative analysis of shared experience in peer-delivered services. Community Ment Health J. (2019), 55:907–15. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00391-y

17

Stamp AS Pedersen LL Ingwersen KG Sørensen D . Behavioural typologies of experienced benefit of psychomotor therapy in patients with chronic shoulder pain: A grounded theory approach. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2018) 31:229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.03.001

18

Haeyen S . Effects of arts and psychomotor therapies in personality disorders. Developing A treatment guideline based on A systematic review using grade. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:878866. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.878866

19

He T Chen Y Song C Li C Liu J Huang J . Reliability and validity of the chinese version of the self-efficacy perception scale for administrator nurses. Int J Nurs Sci. (2023) 10:503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.09.015

20

Kay SR Fiszbein A Opler LA . The positive and negative syndrome scale (Panss) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

21

Luo R Fan N Dou Y Wang Y Wang M Yang X et al . Relationship between cognitive function and functional outcomes in remitted major depression. BMC Psychiatry. (2024) 24:311. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05675-6

22

Zhang Mingyuan HY . Handbook of psychiatric rating scales. Hunan Science & Technology Press (2015).

23

Chen CR Huang YC Lee YW Hsieh HH Lee YC Lin KC . The effects of baduanjin exercise vs. Brisk walking on physical fitness and cognition in middle-aged patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:983994. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.983994

24

Li M Fang J Gao Y Wu Y Shen L Yusubujiang Y et al . Baduanjin mind-body exercise improves logical memory in long-term hospitalized patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102046. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102046

25

Vancampfort D Firth J Stubbs B Schuch F Rosenbaum S Hallgren M et al . The Efficacy, mechanisms and implementation of physical activity as an adjunctive treatment in mental disorders: A meta-review of Outcomes, Neurobiology and key determinants. World Psychiatry. (2025) 24:227–39. doi: 10.1002/wps.21314

26

Sabé M Kohler R Perez N Sauvain-Sabé M Sentissi O Jermann F et al . Mindfulness-based interventions for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Schizophr Res. (2024) 264:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2023.12.011

27

Sylvia LG Lunn MR Obedin-Maliver J Mcburney RN Nowell WB Nosheny RL et al . Web-based mindfulness-based interventions for well-being: randomized comparative effectiveness trial. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:E35620. doi: 10.2196/35620

28

Santosh S Kundu PS . Cognitive self-efficacy in schizophrenia: questionnaire construction and its relation with social functioning. Ind Psychiatry J. (2023) 32:71–7. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_263_21

29

Xu Y Cai Z Fang C Zheng J Shan J Yang Y . Impact of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia during daily care: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2022) 312:114560. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114560

30

Lim A Harijanto C Vogrin S Guillemin G Duque G . Does exercise influence kynurenine/tryptophan metabolism and psychological outcomes in persons with age-related diseases? A systematic review. Int J Tryptophan Res. (2021) 14:1178646921991119. doi: 10.1177/1178646921991119

31

Alizadeh Pahlavani H . Possible role of exercise therapy on depression: effector neurotransmitters as key players. Behav Brain Res. (2024) 459:114791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114791

32

Cummings MA Arias AW Stahl SM . What is the neurobiology of schizophrenia? CNS Spectr. (2024) 30:E13. doi: 10.1017/S1092852924000518

33

Dubreucq J Gabayet F Ycart B Faraldo M Melis F Lucas T et al . Improving social function with real-world social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: results from the remedrugby quasi-experimental trial. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:E41. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.42

34

Saha S Chauhan A Buch B Makwana S Vikar S Kotwani P et al . Psychosocial rehabilitation of people living with mental illness: lessons learned from community-based psychiatric rehabilitation centres in gujarat. J Family Med Prim Care. (2020) 9:892–7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_991_19

35

Kang R Wu Y Li Z Jiang J Gao Q Yu Y et al . Effect of community-based social skills training and tai-chi exercise on outcomes in patients with chronic schizophrenia: A randomized, one-year study. Psychopathology. (2016) 49:345–55. doi: 10.1159/000448195

36

Zheng SS Zhang H Zhang MH Li X Chang K Yang FC . Why I stay in community psychiatric rehabilitation”: A semi-structured survey in persons with schizophrenia. BMC Psychol. (2022) 10:213. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00919-0

Summary

Keywords

community rehabilitation period, complementary intervention, modify psychomotor therapy, schizophrenia, self-efficacy

Citation

Zhang H, Chen C, Chen Y, Hu J, Han J, Ji W and Wang S (2025) Impact of modified psychomotor therapy on self-efficacy in community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia receiving rehabilitation. Front. Psychiatry 16:1721293. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1721293

Received

09 October 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

03 December 2025

Published

16 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Ellie Fossey, Monash University, Australia

Reviewed by

Anna Julia Krupa, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Poland

Sandor Rozsa, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, Hungary

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Chen, Chen, Hu, Han, Ji and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shasha Wang, wss_rehabil@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.