Abstract

Introduction:

Internet-based interventions are effective in the prevention of eating disorders (EDs) but are rarely translated from controlled study settings into practice. This study aimed to assess short- and long-term outcomes and adherence of a suite of internet-based screening and ED prevention programs.

Methods:

In a 5-arm non-randomized dissemination trial, internet-based ED prevention interventions were offered to women recruited from the general population (N = 3,654). Each arm offered a different version of the ED prevention program, tailored for populations at different levels of risk. The interventions comprised 4 to 12 weekly modules based on cognitive-behavioral principles, including psychoeducation, exercises to promote body image and balanced eating, and—if applicable—to reduce ED symptoms. Primary outcome was the change in weight concerns from pre to post, using t-tests and completer data. Secondary outcomes included ED symptoms, eating habits, self-esteem and quality of life.

Results:

Pre-post within-subject comparisons in the completer sample showed significant reductions in weight concerns in 4 of 5 study arms (effect sizes between d = -0.45 and d = -0.94). ED symptoms were reduced and the ability to eat intuitively was improved in all study arms, with some effects persisting up to 12 months. Assessment drop-out ranged from 60.6% to 78.1% at post, and between 18.0% and 44.0% of participants completed the whole intervention.

Discussion:

The trial demonstrates the feasibility of reaching different risk groups for prevention with a combined screening and tailored interventions as well as feasibility of larger scale dissemination of the interventions in the general population.

Clinical trial registration:

http://www.isrctn.org, identifier ISRCTN13716228.

1 Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious mental disorders associated with high morbidity and mortality (1), affecting 8.4% of adult females and 2.2% of adult males worldwide (2). EDs are associated with marked psychosocial impairment, psychiatric comorbidity, and poor quality of life (3, 4). They are characterized by binge eating behaviors, and/or methods to control weight such as purging, excessive exercise, diet pill use, and food restriction. Given their high prevalence and significant impact, scalable and broadly applicable preventive interventions are of great public health importance.

Research in the past few decades has identified a number of modifiable risk factors including body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, weight and shape concerns and thin-ideal internalization (5). Furthermore, there is an overlap between risk factors for eating disorders and overweight and obesity (6, 7) and eating disturbances occur more frequently in women with overweight and obesity than in women with normal weight or underweight (8). Obesity is a risk factor for binge eating disorder (BED) and possibly bulimia nervosa (BN) (5) and, in turn, disordered eating behaviors such as dieting, purging, laxative/diuretic use, and binge eating contribute to excess weight gain (9, 10). As EDs and overweight share risk factors, addressing these and their interactions in preventive interventions could facilitate healthy weight management without increasing weight or shape concerns or facilitating disordered eating (11–13).

Fortunately, many studies have shown that preventive internet-based interventions can reduce ED risk factors and symptoms (14–18) and even reduce ED onset (19, 20). However, while most of this research of EDs has focused on adolescents and young women (21, 22), disordered eating, dieting, and body dissatisfaction are also prevalent in middle-aged and older women (8, 23).

Over the past decade, our research group has developed a suite of internet-based interventions targeting different ED risk groups for selective prevention (24–28) and general populations for universal prevention (29). These interventions have been delivered digitally as self-help and/or as guided self-help to facilitate ease of access, anonymity and provide service at low cost. The interventions proved to be well accepted and efficacious in younger women, e.g., college-age students (25–27), but two interventions also showed promise for improvement of body image and disordered eating in all age groups (everyBody Basic and everyBody Fit) (24, 29).

To date, only few studies evaluated the effectiveness, reach and dissemination of internet-based ED prevention programs in real world settings (e.g., education systems, healthcare systems, social and traditional media). These programs have mostly been implemented in schools and colleges, and demonstrated successful implementation (30–32). However, age groups past the college age affected by body dissatisfaction and other frequent ED risk factors were not included in these studies.

Increasing reach of prevention programs is crucial for the prevention of ED and might be more important than solely increasing the efficacy of programs in terms of their public health impact (33). Accordingly, while universal prevention programs often produce smaller effects than selective prevention (16), they might be better suited for broader dissemination and as population-based approaches (34).

The aim of the current dissemination study therefore was to provide and evaluate a population-based approach for ED prevention targeting shared risk factors of EDs and overweight. The intervention was tailored to individual ED risk status and ED symptoms and combines ED prevention and health promotion for balanced eating and exercise in women of different age groups. Specifically, we aimed to evaluate short- and long-term effectiveness and to examine demographic characteristics of participants, feasibility, and adherence.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

We included women aged 18 and older, interested in participating in an online program to improve their body image, with access to the internet and who gave informed consent online. We excluded women who reported currently receiving psychotherapy for EDs or who had received ED treatment in the past six months. We also excluded women who met the diagnostic criteria for full-syndrome AN, BN or BED and referred them to treatment, as well as women with a body mass index (BMI) below 18.5 kg/m². Participants had to provide an e-mail address to be enrolled in the trial, but did not need to provide their full name.

Participants were recruited via various means directed at a general audience (e.g., press releases, online and print newspaper articles, TV reports, promotional postcards in malls), through health insurances which offered the program as part of their internet-based prevention portfolio, through medical practices (e.g., promotional postcards and posters in waiting rooms) and through means directed at students (e.g., announcement in lectures, posters around campus). Publications about the study included a wide variety of online (including social media), face-to-face and print media to reach the target group of women of all ages from German speaking countries. The intervention was announced as a free online intervention for women who wanted to improve body image and reduce weight and shape concerns. Recruitment took place between November 2016 and May 2019. Students were offered course credits for participation but other participants were initially not compensated for study participation. Within the first months of recruitment, internal data quality reports revealed high drop-out rates for post-intervention and follow-up assessments. Therefore, to improve adherence to the study protocol, participants who completed the post-intervention assessment were entered into a raffle. Each month, four 25€ gift cards were provided.

2.2 Study design and procedure

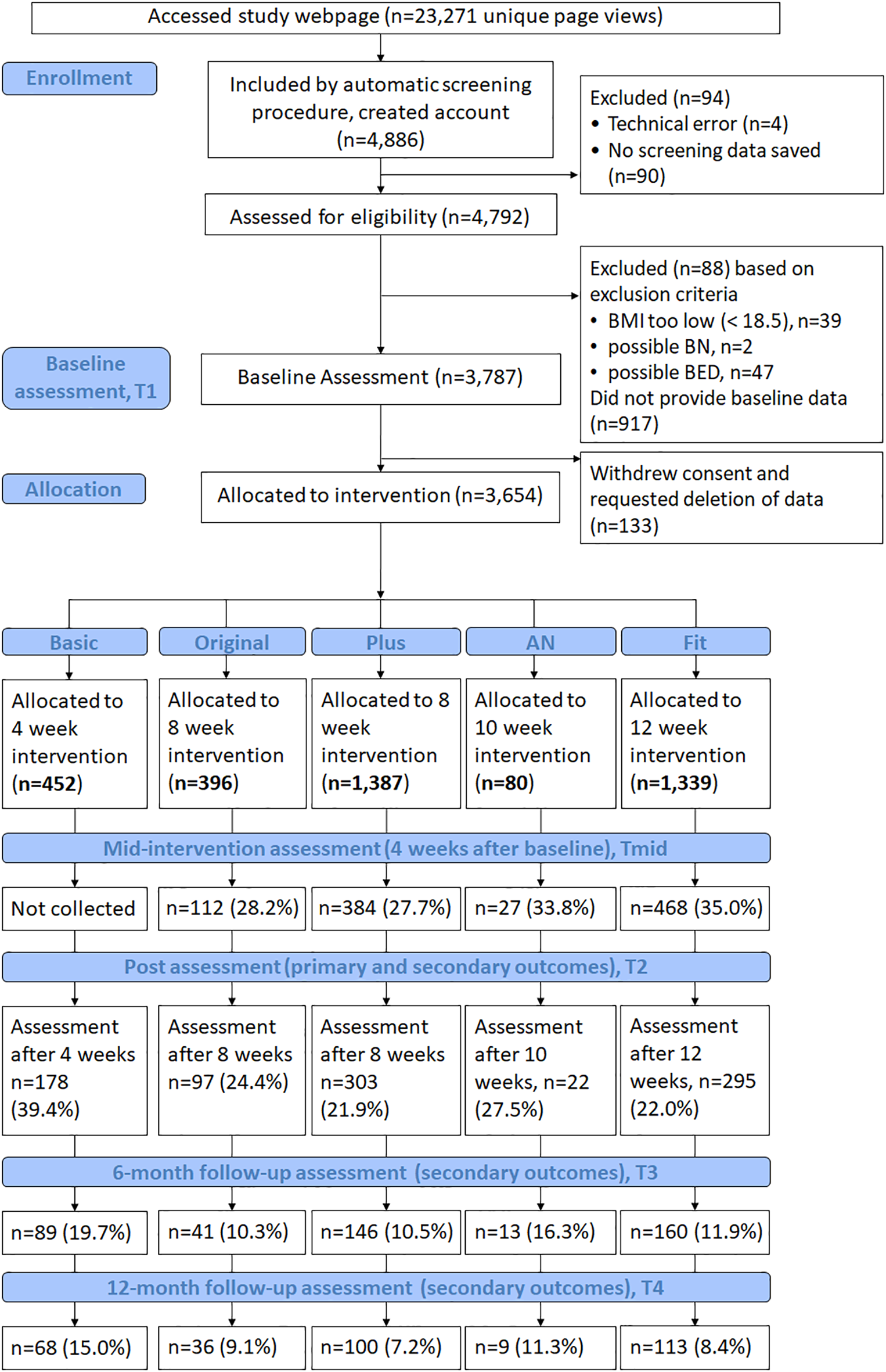

The design of the study was a nonrandomized, parallel-group interventional design. Before enrollment in the intervention, participants were screened for EDs and excluded if exclusion criteria were fulfilled (see Figure 1). Based on the screening information, participants were allocated to one of the five study arms (see Figure 1). The allocation of participants was based on their BMI, the presence of subthreshold (<1/week) binge eating/purging, and the presence of elevated weight and shape concerns defined as a score larger than 42 on the weight and shape concerns scale (WCS) (35).

Figure 1

Participants were screened and included participants were allocated to study arm based on BMI and ED symptoms.

Time between screening and baseline assessment varied between 0–2 weeks. Following inclusion, participants completed baseline assessments (T1) and received access to the intervention they had been assigned to. Further assessments took place at mid-intervention (Tmid), post-intervention (T2), 6-month follow-up (T3), and at 12-month follow-up (T4). Mid-intervention assessment was administered 4 weeks after baseline (except Basic). Post-intervention assessments were administered 4, 8, 10 or 12 weeks after baseline, depending on duration of the intervention in each study arm (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Feature | everyBody study arm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | Original | Plus | AN | Fit | |

| ED symptoms | None | Elevated weight and shape concerns, no other ED symptoms | Elevated weight and shape concerns, occasional binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors | Elevated weight and shape concerns, no other ED symptoms | Possible elevated weight and shape concerns, no other ED symptoms |

| BMI | 18.5-25 | 21-25 | ≥ 18.5 | 18.5-21 | > 25 |

| Duration (weeks) | 4 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Aims | Promoting balanced eating and exercise habits, body image | Improving body image, promoting balanced eating and exercise habits | Improving body image, establishing balanced eating and exercise habits, improving self-esteem, reducing compensatory behaviors | Improving body image, establishing balanced eating and exercise habits, improving self-esteem, reducing dietary restraint | Healthy weight regulation, promoting balanced eating and exercise habits, improving self-esteem and body satisfaction |

| Moderated discussion groups | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individualized weekly feedback | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Accompanying diaries | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Characteristics of the five study arms.

All assessments as well as the interventions were conducted online on an intervention platform provided by Minddistrict (Minddistrict, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), a company specialized in providing online platforms for psychological interventions and research. To be enrolled in the trial and to get access to the assessments and intervention, each participant created a password-protected account on the platform.

This trial has been registered at ISRCTN (ISRCTN13716228) and has been approved by the ethics board of TU Dresden (EK 83032016). The study protocol describing the methods and planned analyses has been published (36).

2.3 Intervention

2.3.1 Content and dosage

For the purpose of this dissemination study, the intervention was adapted from StudentBodies interventions (25–27, 29, 37) and StayingFit (24), all evaluated in previous trials. The adapted version comprises a combined online screening and suite of five tailored, evidence-based prevention programs (“everyBody”), accessible via web browser. Each study arm targets different risk factors presumed to lead to or maintain eating pathology and different stages of risk for eating disorders and/or overweight and obesity (see Figure 1). The characteristics of the five programs are summarized in Table 1.

The intervention content of all these programs is based on cognitive-behavioral principles and aims to improve cognitive, affective and behavioral outcomes. These include psychoeducation, self-monitoring, a personal journal and behavioral exercises. The content focuses on balanced eating and exercise, intuitive eating, self-esteem, dealing with “forbidden foods” and binge eating/purging, improving body image, coping with stress and negative emotions. Sections on intuitive eating promoted eating based on satiety and hunger, reduction of emotional eating and self-permission to eat whatever foods are desired when hungry. The contents of the everyBody interventions are described in more detail in previous publications (24, 26, 38).

Participants were encouraged to complete one session per week, to allow time for consolidation and practice. Each session took 20 to 60 minutes to complete. We added a one-week break between releasing sessions, making it impossible to complete the program ahead of the intended schedule, but there was no upper time limit for completing the intervention. All participants received weekly reminders during the intended duration of the intervention if they did not complete a session. They also received generic weekly e-mail notifications for uncompleted assessments, diary entries, unread messages on the platform and uncompleted sessions.

2.3.2 Discussion groups and diaries

Four study arms (Original, Plus, AN, and Fit) were supplemented by moderated discussion groups to promote the exchange of experiences and thoughts with other participants. Discussion groups were implemented as multi-participant, asynchronous group chats, in which participants from the same study arm were able to communicate with each other. When completing a session, participants were automatically invited to discussion groups themed around the session topics. In each discussion group, the moderator, i.e., a trained psychologist, posted an opening question and moderated the following discussions. The same study arms were supplemented with diaries to record eating habits, exercise behavior, as well as thoughts and feelings related to body image and disordered eating, which were recommended for daily or weekly use.

2.3.3 Individualized feedback

In two arms (Plus and AN), participants received weekly individualized feedback by a coach. Coaches were psychologists (bachelor’s or master’s degree), who received a 1.5h training and continuous supervision by a licensed clinical psychologist specialized in EDs (IB). Based on their entries in diaries and sessions as well as comments in the discussion group, participants received feedback encouraging their motivation to change, helping with cognitive restructuring, suggestions for behavior change, and additional psychoeducation, based on the CBT approach for EDs (39). Participants were encouraged to answer directly to their coach, but messages from the coach were usually limited to one per week. Coaches also provided technical support, if needed.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Screening

A prediction algorithm was applied to exclude potential AN, BN and BED cases from the trial. The online screening included 13 items addressing BMI, weight and shape concerns, restrained eating, loss of control eating and overeating and was previously validated in an independent sample of 215 German women. The screening algorithm had shown excellent classification properties, detecting 98.4% and 91.9% of AN and BN cases (true positives), respectively, as well as good properties in detecting 87.1% BED cases (40). In the current study, the screening algorithm initially categorized a BMI of 41.4 or higher as indicative of BED, regardless of any other symptoms, meaning women with a BMI of 41.4 or higher would be all excluded by the algorithm. To avoid false exclusions, we evaluated all participants with BMI > 41.4 individually for clinically relevant overeating and loss of control eating.

2.4.2 Socio-demographic information

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants, such as year of birth, occupation, relationship status, and self-reported height and weight were assessed. Presence of lifetime diagnoses were assessed via self-report of participants.

2.4.3 Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was weight and shape concerns. Secondary outcomes were ED pathology, eating styles and habits, self-esteem, and quality of life.

2.4.3.1 Weight and shape concerns

Weight and shape concerns were assessed using the Weight Concerns Scale (WCS) (35, 41). The WCS has excellent test–retest reliability of r = .75 for a 12-month interval (English version) (42) and r = .95 for a 7-day interval (German version) (35). The German version showed excellent convergent and discriminant validity (35).

2.4.3.2 ED pathology

ED pathology was assessed using the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire global score [EDE-Q; 43, 44], a 22-item questionnaire covering restrained eating behaviors, eating concerns, and weight and shape concerns. It has good convergent and discriminant validity, shown in a non-clinical sample, as well as good to excellent internal consistency (45).

Core ED symptoms (i.e., number of binge eating episodes in the past four weeks, number of compensatory and weight control behaviors in the past four weeks) were measured using 5 items covering core diagnostic ED behaviors of the EDE-Q (44), omitting the number of days with objective binge eating. Three items assessing the presence of fasting, use of appetite suppressants, and use of diuretics were added (e.g., “Over the past 28 days, how many times have you taken diuretics as a means of controlling your shape or weight?”. Filter questions were added where participants indicated whether the respective symptom had been present during the past 28 days, before they reported the number of incidents. These answers were used to report the presence vs. absence of core symptoms.

2.4.3.3 Eating styles and habits

Intuitive eating was assessed using the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES) (46, 47). The scale assesses three aspects of intuitive eating: ‘‘unconditional permission to eat (when hungry and what food is desired)” (UPE subscale), “eating for physical rather than emotional reasons’’ (EPR subscale), ‘‘reliance on internal hunger and satiety cues to determine when and how much to eat’’ (RIH subscale). Higher total scores indicate higher levels of intuitive eating. Factorial validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, as well as convergent and discriminant validity were shown in a sample of female university students (46).

Fruit and vegetable intake was assessed by four items. Participants reported how many portions of fresh fruit, fresh vegetables, frozen vegetables, and smoothies had been consumed in the past 7 days on a 7-point response scale ranging from 0 to 6 (0, none during the past 7 days; 1, One to three portions during the last 7 days; 2, four to six portions during the last 7 days; 3, about one portion per day; 4 – about two portions per day; 5, about three portions per day; 6, four or more portions per day), e.g., “How many fist-sized portions of fruit did you eat in the last 7 days?” A portion of smoothie or juice was defined as 200 ml (6.8 US fl. oz.) in the instructions. These items had been used in previous studies on the intervention [e.g., 24], but were not assessed for validity or reliability.

2.4.3.4 Other measures of (mental) health

Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, which measures positive and negative aspects of self-evaluation (RSE) (48, 49). Internal consistency, test-retest reliability and convergent and discriminant validity have been shown in several samples (49–51).

Quality of Life was assessed with the Assessment of Quality of Life-8D (AQoL-8D) (52), using the overall utility score of the scale. Factorial, convergent, predictive, and content validity, as well as internal consistency and test-retest reliability have been shown in Australian and US samples so far (53, 54).

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 9-item depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (55, 56) Validity and reliability of the scale have been shown in samples of the German general population (57, 58). The 7-item generalized anxiety module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (GAD-7) (59) was used to assess symptoms of general anxiety disorder. Its validity and reliability has been shown in a sample of the German general population (60). Depressive symptoms and symptoms of generalized anxiety were assessed as moderators, but are only used as predictors for multiple imputation purposes within this publication.

An overview of all measures, including moderators and mediators to outcome and adherence, and their time points of assessment has been published in the study protocol (36).

2.4.4 Adherence

Adherence to the intervention (completed sessions) and engagement with the intervention (diary entries, use of discussion group, number of messages to moderator) was extracted from study data and platform logfiles.

2.5 Adverse events

The following adverse events (AE) were defined for this trial: AE1) onset of binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors between screening and follow-up-period in participants who did not show these symptoms at screening; AE2) diagnostic threshold of frequency of binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors is met during the follow-up-period by participants with prior subthreshold symptoms; AE3) BMI drops below 18.0 kg/m2 during the follow-up-period; and AE4) participant reports inpatient treatment for ED during the follow-up-period.

2.6 Data management and statistical analyses

2.6.1 Data collection

Primary data was collected on the Minddistrict platform. Participants provided self-report assessment within the Minddistrict platform. Data was downloaded for data analysis as CSV files. Data preparation, data cleaning, as well as calculation of derived variables and scores, and data analysis was performed in the SAS Software (Version 9.4, SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data was monitored for completeness during the trial by DG (University of Münster).

General principles of data analysis in the project are described by Görlich and Faldum (61). Furthermore, data analysis followed accepted guidelines such as the ICH E9 “Statistical Guidelines for Clinical Trials” (62).

2.6.2 Analysis sets

The full analysis set includes all participants assigned to a study arm who completed at least the baseline assessment. Intention-to-treat analyses (ITT) were performed on the full analysis set based on the assigned study arm. The completer set includes participants who completed the questionnaires for the respective analyses in the mid assessments, post assessments, 6-months and/or 12-months follow-ups. The per-protocol set is defined by all participants included in the trial who did not exhibit major protocol violations. Protocol violations were defined by any violation of inclusion criteria with respect to the assigned study arm, i.e. participants received the wrong intervention or should have been excluded from the beginning.

2.6.3 Sample size calculation

An a-priori power analysis and sample size determination was performed (36). We planned to detect an intervention effect of d = 0.2 in a two-sided one-sample pre-post test. A total sample size of 2080 women in all study arms would have had to be enrolled in the study and complete post-intervention assessments to reach a power of 80% in the study arm with the lowest expected recruitment, given the prevalence rates of the varying symptoms in each study arm described in Table 1. A-priori, a drop-out rate of 50% was assumed, based on the most recent everyBody studies with drop-out rates of 54% (24) and 45% (29), respectively and a total of 4,160 women was set as recruitment aim.

2.6.4 Data analysis strategy

The statistical analysis plan was finalized before the data analysis was performed.

Each study arm was analyzed separately with two-sided statistical tests with a separate significance level of α = 0.05 for each primary confirmatory null hypothesis. Direct comparisons between study arms were neither planned a-priori nor conducted. Secondary and exploratory analyses were performed without correction for multiple testing due to the exploratory character of these analyses.

Categorical variables were reported using absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables were analyzed by mean and standard deviation.

In the study protocol, analyses using multiple imputed datasets were defined for the primary outcome, and conducting analyses of complete cases (completer analyses) were planned for sensitivity analyses. Due to the high assessment drop-out in all study arms, multiple imputation seemed no longer suitable for the primary analysis. Methodological considerations regarding the mechanisms of missingness and methodological results as e.g. presented by White and Carlin (63) supported that complete case analysis is an acceptable approach in this scenario. Especially when the probability for missing values did not depend on the outcome measure itself, complete cases analysis was less biased than multiple imputation analysis (63).

Instead, we conducted completer analyses for the primary outcome and performed sensitivity analyses using the imputed datasets. This change in the analysis strategy was already pre-specified in the first version of the statistical analysis plan, signed before data analysis. No outcome data was analyzed to make this decision, only drop-out rates were considered.

The study protocol determined a non-parametric analysis (two-sided Wilcoxon rank test) to compare pre-post WCS scores within each study arm. The review of the collected data revealed a normal distribution of the score differences. Thus, the primary analysis was performed using one-sample t-tests without impairment of the validity and consistency of results and increasing power at the same time. For each study arm the primary null hypothesis was tested.

Secondary outcomes were also analyzed using completer data. Two-sided one-sample t-tests were conducted for WCS, EDE-Q, IES, RSE, and AQoL-8D. Changes of binary outcomes, i.e. ED core symptoms (e.g. loss of control eating, excessive exercise) between assessments were analyzed using McNemar’s tests. Changes in frequency of fruit and vegetable intake were analyzed on item level using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Results of t-tests were reported with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the primary and secondary outcomes including point-wise 95% confidence intervals. As descriptive statistics for the binary outcomes we reported the proportion of participants with improvements (Nimproved) at each time point among all symptomatic participants (Nsymptomatic) at baseline.

Multiple imputation for missing data was conducted via predictive mean matching, following the fully conditional specification (FCS) approach (64, 65). Due to computational issues study arm AN, data was imputed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method. Separate imputation models were estimated for each study arm with m = 50 imputations. Only WCS time series data was imputed. Each time point was imputed based on statistical regression model incorporating only data from preceding time points. After imputation, pre-post within-subject differences were calculated and tested with one-sample t-tests. The single test statistics were pooled according to Rubin’s rule (66) and final test statistic and p-value was calculated.

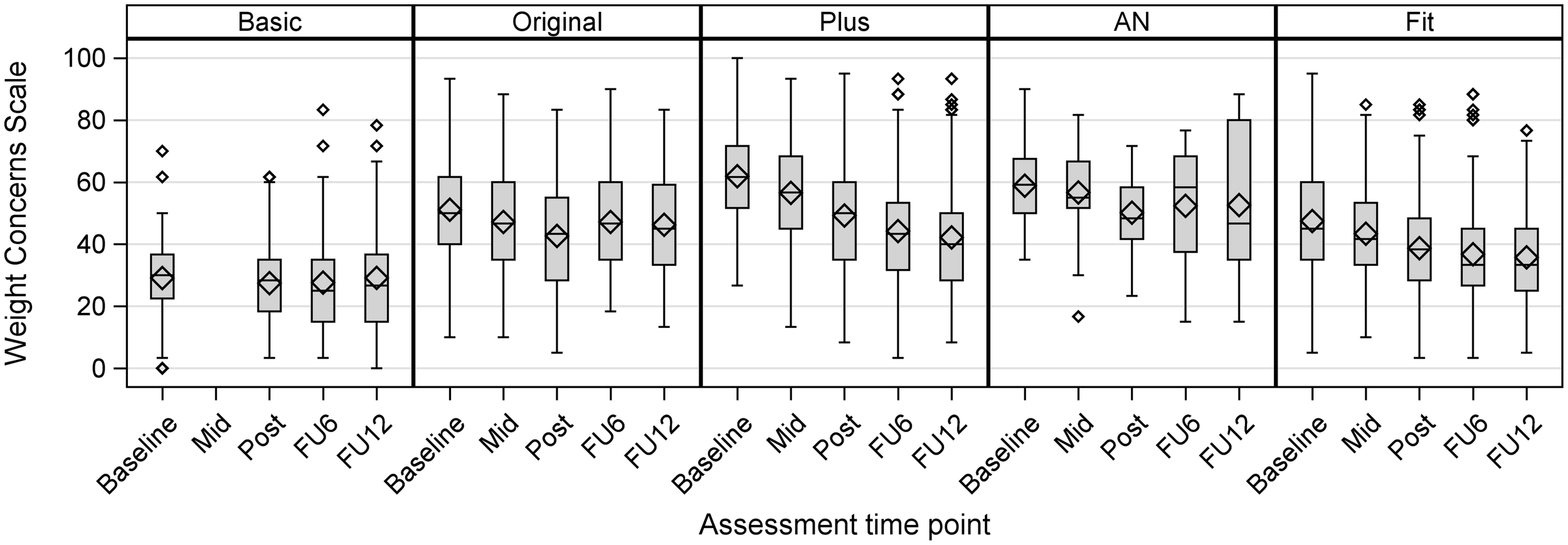

Box plots were used to visualize median scores, mean scores, quartiles, minima, maxima and outliers of primary and secondary outcomes across time points and study arms. Measures of adherence/engagement were reported descriptively. Adverse events (yes/no) were described by absolute and relative frequencies for each type of event.

Simple linear regression models of completer data were used to assess the impact of adherence on the primary outcome, using the number of completed sessions as independent variable and WCS scores at post, 6- and 12-months follow up as dependent variables.

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

In total, 4,886 women were screened, 3,787 provided data for the baseline assessment and 3,654 were allocated to one of the five study arms. Of those, 452 were allocated to the study arm Basic, 396 to Original, 1,387 to Plus, 80 to AN, and 1,339 to study arm Fit. Figure 2 presents the number of reached, screened, included, allocated and assessed participants in total and per study arm. Group sizes are based on whether any data was collected during the respective assessments, regardless of the collection of the primary outcome. Therefore, it is possible that the sample size for a specific study arm and time point is greater that the number of collected WCS (primary outcome) data.

Figure 2

Flow of participants from opening the study website to 12-months follow-up assessments.

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of participants at baseline. Mean age of the overall sample was 40.97 years (SD = 13.73, range 18 – 84). The majority of participants (66.3% to 91.3%) in each study arm had an education level of upper secondary education (European Qualifications Framework Level 4) or higher. About three quarter of the sample (72.5% to 78.9%) were in a relationship at baseline. The majority of participants were in part- or full-time employment (57.5% to 71.2%) and 8.1% to 45.0% were in training at the time. Between 22.6% (study arm Basic) and 43.8% (AN) reported a lifetime diagnosis of any mental disorder (see Supplementary Table S1 in the appendix). Baseline fruit and vegetable intake of participants are presented in Supplementary Table S1 in the appendix.

Table 2

| Study arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | Original | Plus | AN | Fit | |

| Variable | N = 452 | N = 396 | N = 1,387 | N = 80 | N = 1,339 |

| Age, M (SD) | 37.57 (13.45) | 37.48 (13.17) | 38.94 (13.71) | 31.98 (11.16) | 45.79 (12.67) |

| Age, range | 18-75 | 18-79 | 18-84 | 18-61 | 18-83 |

| BMI, M (SD) | 21.83 (1.94) | 22.83 (1.51) | 27.65 (5.51) | 19.98 (0.74) | 30.54 (5.12) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Single | 111 (24.56) | 89 (22.47) | 379 (27.33) | 22 (27.50) | 283 (21.14) |

| In a relationship | 159 (35.18) | 149 (37.63) | 450 (32.44) | 37 (46.25) | 290 (21.66) |

| Married, in a registered civil partnership, or shared household relationship | 182 (40.27) | 158 (39.90) | 558 (40.23) | 21 (26.25) | 766 (57.21) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |||||

| Currently in training (in school, vocational training, college, or university) | 122 (26.99) | 101 (25.51) | 326 (23.50) | 36 (45.00) | 109 (8.14) |

| Seeking employment | 10 (2.21) | 23 (5.81) | 65 (4.69) | 2 (2.50) | 53 (3.96) |

| Housewife | 19 (4.20) | 19 (4.80) | 98 (7.07) | 4 (5.00) | 113 (8.44) |

| Self-employed | 33 (7.30) | 35 (8.84) | 77 (5.55) | 5 (6.25) | 94 (7.02) |

| Part time employment (less than 35 hours) | 152 (33.63) | 111 (28.03) | 379 (27.33) | 15 (18.75) | 433 (32.34) |

| Full time employment (35 or more hours) | 147 (32.52) | 143 (36.02) | 536 (38.67) | 31 (38.75) | 520 (38.83) |

| Retired | 22 (4.87) | 16 (4.04) | 70 (5.05) | 3 (3.75) | 136 (10.16) |

| PHQ-9, M (SD) | 5.49 (3.96) | 7.34 (4.35) | 9.53 (5.03) | 8.51 (5.22) | 6.49 (4.50) |

| GAD-7, M (SD) | 5.15 (4.07) | 6.00 (3.98) | 7.43 (4.56) | 6.88 (4.54) | 5.23 (4.08) |

Participants’ characteristics by study arm.

PHQ-9, 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire.

3.2 Protocol violations

Twenty-three participants were included in the study by the screening algorithm although their BMI met the exclusion criterion of a BMI less than 18.5 (AN = 1; Basic = 21; Original = 1). Additionally, four included participants violated the inclusion criteria of the Plus program, as reasons for exclusion only became apparent during baseline or later assessments. Following the ITT principle all participants with protocol violations are analyzed in the completer as well as in the multiple imputation analysis.

3.3 Adherence

Participants completed an average of 2.31 (SD = 1.69; study arm Basic), 3.31 (SD = 3.13; Original), 2.68 (SD = 2.98; Plus), 3.70 (SD = 3.95; AN), and 4.55 (SD = 4.63; Fit) sessions. Between 44.0% (study arm Basic) and 18.0% (study arm Plus) of participants completed all respective sessions, and between 20.1% (study arm Fit) and 32.5% (study arm AN) did not complete the first session. Supplementary Tables S2–S4 in the appendix describe adherence and engagement measures regarding session completion, platform and intervention use, use of diaries, discussion groups and messages to moderators. Supplementary Figure S1 in the appendix illustrates the percentage of completed sessions in each study arm.

3.4 Outcomes

3.4.1 Weight and shape concerns

For the primary outcome, there were significant within-subjects differences for the completer sample on the Weight Concerns Scale (WCS) scores from baseline to post-assessment for study arms Original, Plus, AN and Fit, with effect sizes of d = -0.45, 95% CI [-0.66, -0.24], d = -0.87 [-1.01, -0.74], d = -0.94 [-1.44, -0.43], and d = -0.54 [-0.67, -0.42], respectively (see Table 3). Sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation (Supplementary Tables S11-S15 in the appendix) revealed consistent results, i.e., significant changes of WCS scores from baseline to post-assessment in the same four study arms. In the study arm Basic, significant changes in WCS scores from baseline to post-assessment were shown in the multiple imputation analysis, d = -0.16, 95% CI [-0.23, -0.08], but not in the completer sample.

Table 3

| Baseline | Mid-intervention | Post | 6-months follow-up | 12-months follow-up | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study arm | M (SD), N | M (SD), N | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | M (SD), N | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | M (SD), N | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | M (SD), N | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

| Basic | 29.09 (10.25), N=452 | [not assessed] | 27.44 (12.47), N=178 | .07 | -0.14 (-0.28, 0.01) | 27.61 (15.76), n = 88 | .46 | -0.08 (-0.29, 0.13) | 29.13 (16.67), n = 65 | .96 | -0.01 (-0.25, 0.24) | ||

| Original | 51.12 (15.70), N=396 | 47.16 (17.58), n = 110 | .11 | -0.15 (-0.34, 0.04) | 42.66 (16.84), N=97 | <.001 | -0.45 (-0.66, -0.24) | 47.15 (16.45), n = 41 | .18 | -0.22 (-0.52, 0.10) | 46.25 (18.08), n = 36 | .050 | -0.34 (-0.67, 0.00) |

| Plus | 61.90 (13.35), N=1387 | 56.54 (15.59), n = 376 | <.001 | -0.52 (-0.63, -0.41) | 49.23 (16.64), N=301 | <.001 | -0.87 (-1.01, -0.74) | 44.22 (17.07), n = 145 | <.001 | -1.01 (-1.21, -0.81) | 42.17 (18.38), n = 100 | <.001 | -1.13 (-1.38, -0.87) |

| AN | 58.85 (12.07), N=80 | 56.67 (14.42), n = 27 | .013 | -0.52 (-0.91, -0.11) | 50.15 (12.57), N=22 | <.001 | -0.94 (-1.44, -0.43) | 52.36 (19.14), n = 12 | .016 | -0.82 (-1.46, -0.15) | 52.59 (26.35), n = 9 | .234 | -0.43 (-1.10, 0.27) |

| Fit | 47.43 (16.54), N=1339 | 43.37 (14.66), n = 453 | <.001 | -0.28 (-0.37, -0.18) | 38.71 (15.16), N=294 | <.001 | -0.54 (-0.67, -0.42) | 36.75 (15.65), n = 160 | <.001 | -0.70 (-0.88, -0.53) | 35.75 (15.22), n = 111 | <.001 | -0.68 (-0.89, -0.47) |

Means, standard deviations, p-value of t-tests for WCS scores, and within-subjects effect sizes from baseline to mid, post and follow-up assessments per study arm based on completer data.

Negative differences and effect sizes indicate improvement in weight and shape concerns. All p-values represent comparisons with baseline.

WCS, Weight and Shape Concerns Scale.

Figure 3 provides an overview of WCS scores for all time points. Secondary outcomes regarding the WCS, i.e., comparisons of baseline scores with mid, post, 6-months follow-up and 12-months follow-up revealed maintained improvements of WCS scores over all time point in study arms Plus and Fit, which were confirmed by multiple imputation analyses. In study arm Original, completer data showed improvements only at post, but multiple imputation analyses show significant improvements at every time point. There were no significant within-subject differences of WCS scores in the Basic study arm except for post assessment in the multiple imputation analysis. While completer data showed significant improvements for mid assessment, post, and 6-months follow-up in study arm AN, multiple imputation analyses confirmed this effect only for the post assessment. Further sensitivity analyses using mixed model analyses confirmed the results of the primary analysis of baseline-post differences in each study arm and for most other time points as well (see Supplementary Table S16 in the appendix).

Figure 3

Box plots of WCS scores for each time point and study arm, depicting median scores, mean scores (diamond shape), quartiles, minima, maxima and outliers (completer data).

Since no protocol violation was present in study arm Fit, the per-protocol analysis was only performed for AN, Plus, Basic and Original. The results were consistent with the completer analysis, except for Study arm Basic. In this arm WCS scores significantly improved at post-assessment (d = -0.16; 95% CI: -0.31, -0.01) (see Supplementary Table S5 in the appendix).

3.4.2 Secondary outcomes and follow ups

Results of the secondary outcome analyses for the completer sample are shown in Supplementary Tables S6–S10 in the appendix. Descriptive characteristics are shown in Supplementary Figures S2–S5 in the appendix. In study arms Plus and Fit, t-tests revealed significant improvements in EDE-Q, IES, RSE, and AQOL-8D scores between baseline and all subsequent time points. In study arms Basic, Original, and AN, scores significantly improved on most of these measures at most time points. According to the McNemar’s tests, the presence of ED symptoms in the Plus arm declined significantly for most symptoms and time points, while in the other arms, the prevalence of most core symptoms did not change significantly between time points, or McNemar’s tests could not be carried out due to too few cases. Effect sizes in the Basic study arm ranged between d = -0.23, 95% CI [-0.54, -0.24] for ED pathology (EDE-Q total scores; 6-month follow-up) and d = 0.78 [0.49, 1.07] for intuitive eating scores (IES; 12-month-follow-up), indicating improvements in these measures. In the study arm Original, effect sizes ranged between d = -0.35 [-0.69, -0.01] for EDE-Q scores (12-month follow-up) and d = -0.68 [-0.90, -0.46] for EDE-Q scores (post). Effect sizes in the Plus study arm ranged from d = 0.31 [0.21, 0.42] for self-esteem (RSE scores; mid-intervention) to d = -1.16 [-1.31, -1.02] for EDE-Q scores (post). In the AN study arm, effects ranged between d = 0.46 [0.01, 0.89] for IES scores (post) and d = -1.26 [-2.01, -0.47] for EDE-Q scores (6 month-follow up). In the Fit study arm, effects ranged between d = 0.20 [0.11, 0.30] for RSE scores (mid-intervention) and d = 0.90 [0.66, 1.13] for IES scores (12-month follow-up). Almost all significant within-subject differences in the completer sample were confirmed by multiple imputation analyses (see Supplementary Tables S11–S15 in the appendix), except in study arm AN for IES scores at post and RSE scores at 6-months follow-up. Multiple imputation analyses additionally revealed improvements in study arm Basic (RSE at post and 12-months follow-up) and in study arm Original (EDE-Q at 6-months follow-up, IES at 12-months follow-up, RSE at 12-months follow-up). Further sensitivity analyses using mixed model analyses largely confirmed the results of the completer analyses, with few deviations (see Supplementary Table S16 in the appendix).

3.4.3 Adherence and outcomes

Analyses of linear regression models using completer data revealed that the number of completed sessions impacted improvements in WCS scores in each study arm at varying time points. In study arm Basic, participants’ average WCS score difference from 6-months follow up to baseline decreased by 10.54 for each completed session, p =<.001, 95% CI [-15.78, -5.30]. In study arm Original, average differences in WCS scores decreased by 2.01 per intervention session at post, p =<.011 [-3.55, -0.48], in study arm Plus average differences in WCS scores decreased by 1.59 at post, p =<.001 [-2.41, -0.77] and in study arm AN by 2.04 at post, p = .004 [-3.35, -0.72]. In study arm Fit, average differences in WCS scores decreased by 0.86 at post, p = .007 [-1.48, -0.23], and by 2.04 at 12-months follow-up, p =<.001 [-3.19, -0.90]. At all other time points, no significant associations were found. Results of the linear regression models are presented in Supplementary Tables S17–S21 in the appendix.

3.5 Adverse events

The proportion of participants with adverse events ranged between 0% and 25% depending on study arm and assessment time point (see Supplementary Table S22 in appendix). In study arm Original, up to 25% of participants showed adverse events AE1 and AE2 at 6-month and at 12-month follow-up, i.e., participants without and with prior core symptoms reported onset of ED symptoms or met the diagnostic threshold of one or more ED symptoms, respectively. A BMI drop below 18.0 (adverse event 3) was most prominent in study arm AN (n = 5). Inpatient treatment for ED (adverse event 4) was only reported in study arm Plus (n = 3).

4 Discussion

The aim of this study was to disseminate and evaluate the effectiveness, adherence, participants’ demographics, and feasibility of a suite of tailored online interventions for ED health promotion and prevention in women of the general population, including previously underserved age groups. Four of the five study arms were targeted at women at risk for EDs based on specific or common risk factors, such as weight and shape concerns, disordered eating behaviors, and other early symptoms of ED. The fifth study arm, a universal preventive intervention (study arm Basic), targeted women without any risk factors.

Overall, uptake of the combined screening and intervention approach was high with 76% (3,654 out of 4,792 women) of screened women allocated to one of the five study arms. However, intervention and assessment drop-out turned out to be markedly higher than expected. While we had estimated an assessment baseline-post drop-out rate of 50%, actual rates ranged between 60.6% and 78.1% at post-intervention and were even higher at follow-up. Intervention adherence also varied between study arms, with the highest adherence rate occurring in the shortest intervention (study arm Basic; 40.9% full completion rate).

The analyses of outcome measures suggest a beneficial impact, although the study design does not allow for causal inferences of intervention effects. Across the four intervention groups with individuals at risk for eating disorders, we found a significant reduction in weight and shape concerns, for both completer and imputed data samples. In the universal prevention study arm Basic, a significant reduction could only be found in the imputed data sample and in the per-protocol analysis. The reduction of weight and shape concerns was maintained up to 12 months for women with subthreshold binge eating symptoms and compensatory behaviors or higher BMI at baseline (study arms Plus and Fit), and up to 6 months for women with lower BMI and restrictive eating (study arm AN). The improvements in intuitive eating and ED pathology, such as eating concerns, restrained eating and weight and shape concerns were stable at most time points in all study arms. In study arm Plus, tailored for participants with initial binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors, we found stable reductions in these initial ED symptoms. The increase of fruit and vegetable intake was maintained up to 12 months in study arm Fit (targeted at women with higher BMI), which incorporated suggestions to increase fruit and vegetable intake. As study arm Basic was tailored for women with no or very low levels of weight and shape concerns and no other risk factors, we assume this group generally did not have much room for improvement. Beyond ED symptomatology, positive and stable within-subject differences up to 12 months were found for self-esteem in study arms Plus and Fit and for quality of life in study arms Basic, Plus and Fit. Finally, while weight was not an outcome measure, we found BMI was mostly stable up to 12 months follow-ups.

We found a significant impact of adherence on weight and shape concerns in all study arms, i.e., for post assessments (study arms Original, Plus, AN, and Fit), 6-months follow-up (study arm Basic) and 12-months follow-up (study arm Fit), however not for other time points. This suggests that using more of the intervention may be beneficial for participants by showing a greater reduction weight and shape concerns with greater adherence. However, we collected proportionally more outcome data of participants who finished most or all of the intervention than of those who finished fewer sessions. All five interventions had already been proven to be efficacious, i.e., shown to reduce risk factors and symptoms for ED in previous individual randomized controlled trials (25–27) or pilot studies (24, 29). The current study design, however, allowed for a tailored preventive approach from universal to selected levels and thus the inclusion of participants with very diverse ED symptomology and previously underserved age groups not reached so far.

The stable improvement in weight and shape concerns, a major risk factor for EDs and obesity, in other ED behaviors and attitudes, in self-esteem, and in quality of life for the completer sample also suggest that this approach could be beneficial under real-world conditions. Despite high drop-out rates and intervention attrition it is important to note that a total of 750 participants (20.5%) across all study arms completed the full intervention. The value of the current broad dissemination approach therefore lies in the large scale at which the intervention can be provided. As suggested by other authors, for their public health impact increasing the reach of prevention programs might be more important than solely increasing the efficacy of interventions (33).

In addition, the approach also proved feasible. The majority of participants not included in the study dropped out before and during the baseline assessment. Only a few (1.8%) screened participants were ineligible for participation, which demonstrates the feasibility of the combined screening and allocation procedure to a tailored intervention based on participants’ risk characteristics. As screening for level of risk and intervention allocation were mostly conducted automatically without including study staff resources, this tailored, population-based approach seems both promising and economic for reaching large populations and thus the scalability required for successful eating disorder prevention (32).

Another strength of the study is the assessment of long-term outcomes 12 months after inclusion. Finally, the recruitment of a large and age-diverse sample from the general population combined with minimal exclusion criteria strengthens the external validity of this trial.

However, the study also had a number of limitations. We performed separate confirmatory analyses with respect to the primary outcome within each study arm. Nevertheless, the remainder of analyses is exploratory without further correction for multiple testing and might yield the risk for false positive findings.

Assessment drop-out of this dissemination study was higher than estimated and higher compared to previous studies including StudentBodies interventions with drop-out rates between 3% and 54% (24–27, 29) or other internet-based ED prevention programs ([weighed mean post assessment drop-out rate of 21%) (18). In the current study, this might be due to the larger number of questionnaires participants had to complete, which also included questionnaires addressing moderator and mediator variables (36) not reported in this publication. Furthermore, enrollment in the trial was conducted completely online and automated. Little effort for enrollment might result in a higher number of drop-outs later on, when participants are faced with more work than initially expected (67). The outcomes of this study therefore must be interpreted on the basis of possible sampling biases due to the high drop-out rates and high proportions of imputed data. Due to the absence of specific tests to validly discriminate between data missing-at-random and data missing-not-at-random, the appropriateness of the imputation procedure may be questionable.

Intervention drop-out was also higher compared with previous studies on the interventions (24–27) or other internet-based ED prevention programs (18), but this seems to be expected in a non-randomized dissemination trial designed to increase reach. Intervention drop-out in internet-based interventions is usually higher in more open, naturalistic settings than in controlled research settings such as RCTs (68, 69). A recruitment strategy that increases reach might recruit more participants who are less motivated, reducing uptake rates and engagement (34). Recently, the personalization of frequency, timing, content, or mode of delivery of personalized reminders has been discussed for a positive impact on adherence (18). Unfortunately, due to technical constraints we were not able to adjust or personalize e-mail reminders in the study. Future revisions of the interventions could employ user-centered design methods to refine intervention content and technical features in order to improve engagement (70).

Due to its uncontrolled design, the current trial does not allow to draw causal inferences of intervention effects, as improved outcomes might also be produced by spontaneous remission or expectancy effects. However, in this large-scale dissemination trial with recruitment in the general population, including control conditions were not feasible. For example, health insurance companies were only willing to support recruitment if all eligible participants would have access to the everyBody interventions. As a large proportion of participants (49%) were recruited via health insurances, the reach of the interventions was likely only to be achieved without control groups.

Another limitation concerns the imbalance in recruitment of different risk groups. Not unexpectedly, we were only able to recruit a relatively small number of participants with restrictive eating and lower BMI for study arm AN. In the randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of this intervention, 4,646 participants had to be screened to be finally able to randomize the required number of 168 randomized participants (3.6%) (27, 71). The under-recruitment of this study arm and – consequently - the reduced statistical power might have produced fewer significant within-subject differences compared to other study arms. For the same reasons, results in this study armed should be considered exploratory in nature. It also reflects once more the difficulty to reach this particular population for prevention purposes in general (72). Finally, reports of adverse events suggest a possible later onset of eating disorder symptoms (binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors, BMI dropping below 18.0) in study arms Original and AN at 6- and 12months follow-up. Again, the respective percentages are heavily influenced by the high drop-out rates at these time points. While worsening of symptoms and treatment options were covered in the intervention content and moderator training, future dissemination programs should plan and budget for mechanisms to detect presence and onset of clinically relevant symptoms. These could include automated notifications to staff members or follow-up information to participants to inform about later onset of symptoms and courses of action.

5 Conclusion

Overall, the results illustrate the potential benefit of the dissemination of tailored internet-based ED prevention at a large scale. The intervention variants address a broad spectrum of risk from no risk to high risk for EDs. This could make the implementation of the suite of interventions potentially appealing to providers. The automated screening and allocation procedure provides feasible opportunities for dissemination of the prevention programs. However, presence and onset of symptoms will still have to be monitored and addressed. User experience might need to be improved to increase adherence and engagement with the interventions for future dissemination purposes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Board at the Dresden University of Technology (Approval number: EK 83032016). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BN: Project administration, Visualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation. DG: Data curation, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. IB: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. BV: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. JS-H: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. CBT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. CJ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 634757.

Acknowledgments

Co-author C. Barr Taylor has passed away on November 30th 2023. The authors would like to thank Sarah Buntzel, Franziska Hagner, Hanne Haumann, Kristian Hütter, Stefanie Kircheis, Corinna Klitzke, Judith Meurer, Luise Müller, Majra Pauli, Maxi Petzold, Arvidh Schaub, Christiane Schlereth, Jara Schulze, and Pia Trübenbach for providing personal guidance to participants as coaches. We also thank Oleg Choubine (University of Münster) for continuous data management support during the trial conduct and data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1731066/full#supplementary-material

References

1

American Psychiatric Association . Treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed. Vol. 163. American Psychiatric Association (2006) p. 4–54.

2

Galmiche M Dechelotte P Lambert G Tavolacci MP . Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 109:1402–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

3

DeJong H Oldershaw A Sternheim L Samarawickrema N Kenyon MD Broadbent H et al . Quality of life in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not-otherwise-specified. J eating Disord. (2013) 1:43. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-43

4

Keski-Rahkonen A Mustelin L . Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2016) 29:340–45. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000278

5

Jacobi C Hütter K Fittig E . Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. In: AgrasWSRobinsonA, editors. The oxford handbook of eating disorders. Oxford University Press, New York (2018). p. 106–25.

6

Goldschmidt AB Wall M Choo THJ Becker C Neumark-Sztainer D . Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychol. (2016) 35:245–52. doi: 10.1037/hea0000283

7

Neumark-Sztainer D Wall MM Haines JI Story MT Sherwood NE van den Berg PA . Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. (2007) 33:359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031

8

Hilbert A de Zwaan M Braehler E . How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? Norms of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire. PloS One. (2012) 7:e291–25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029125

9

Neumark-Sztainer D Wall M Story M Standish AR . Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health. (2012) 50:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.010

10

Sonneville KR Horton NJ Micali N Crosby RD Swanson SA Solmi F et al . Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatr. (2013) 167:149–55. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12

11

Ciao AC Loth K Neumark-Sztainer D . Preventing eating disorder pathology: common and unique features of successful eating disorders prevention programs. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2014) 16:453. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0453-0

12

Kass AE Jones M Kolko RP Altman M Fitzsimmons-Craft EE Eichen DM et al . Universal prevention efforts should address eating disorder pathology across the weight spectrum: Implications for screening and intervention on college campuses. Eat Behav. (2017) 25:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.019

13

Rancourt D McCullough MB . Overlap in eating disorders and obesity in adolescence. Curr Diabetes Rep. (2015) 15:78. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0645-y

14

Le LK-D Barendregt JJ Hay P Mihalopoulos C . Prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 53:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.02.001

15

Melioli T Bauer S Franko DL Moessner M Ozer F Chabrol H et al . Reducing eating disorder symptoms and risk factors using the internet: A meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:19–31. doi: 10.1002/eat.22477

16

Watson HJ Joyce T French E Willan V Kane RT Tanner-Smith EE et al . Prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:833–62. doi: 10.1002/eat.22577

17

Harrer M Adam SH Messner EM Baumeister H Cuijpers P Bruffaerts R et al . Prevention of eating disorders at universities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:813–33. doi: 10.1002/eat.23224

18

Linardon J Shatte A Messer M Firth J Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M . E-mental health interventions for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2020) 88:994–1007. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000575

19

Taylor CB Kass AE Trockel M Cunning D Weisman H Bailey J et al . Reducing eating disorder onset in a very high risk sample with significant comorbid depression: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2016) 84:402–14. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000077

20

Stice E Rohde P Shaw H Gau JM . Clinician-led, peer-led, and internet-delivered dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Acute effectiveness of these delivery modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2017) 85:883–95. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000211

21

Mangweth-Matzek B Hoek HW Pope HG . Pathological eating and body dissatisfaction in middle-aged and older women. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2014) 27:431–35. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000102

22

Slevec JH Tiggemann M . Predictors of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in middle-aged women. Clin Psychol Rev. (2011) 31:515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.002

23

Mangweth-Matzek B Hoek HW Rupp CI Lackner-Seifert K Frey N Whitworth AB et al . Prevalence of eating disorders in middle-aged women. Int J Eat Disord. (2014) 47:320–24. doi: 10.1002/eat.22232

24

Beintner I Emmerich OLM Vollert B Taylor CB Jacobi C . Promoting positive body image and intuitive eating in women with overweight and obesity via an online intervention: Results from a pilot feasibility study. Eat Behav. (2019) 34:101307. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.101307

25

Jacobi C Morris L Beckers C Bronisch-Holtze J Winter J Winzelberg AJ et al . Maintenance of internet-based prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. (2007) 40:114–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20344

26

Jacobi C Völker U Trockel MT Taylor CB . Effects of an Internet-based intervention for subthreshold eating disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2012) 50:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.013

27

Jacobi C Vollert B Hütter K von Bloh P Eiterich N Görlich D et al . Indicated web-based prevention for women with anorexia nervosa symptoms: randomized controlled efficacy trial. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24:e35947. doi: 10.2196/35947

28

Beintner I Jacobi C Taylor CB . Effects of an internet-based prevention programme for eating disorders in the USA and Germany — A meta-analytic review. Eur Eating Disord Rev. (2012) 20:1–8. doi: 10.1002/erv.1130

29

Vollert B Beintner I Taylor CB Jacobi C . A short unguided online training to promote healthy body image and balanced eating in a low-risk sample – Results from a feasibility study. (2021).

30

Bauer S Moessner M Wolf M Haug S Kordy H . ES[S]PRIT - an Internet-based programme for the prevention and early intervention of eating disorders in college students. Br J Guid Counc. (2009) 37:327–36. doi: 10.1080/03069880902957049

31

Fitzsimmons-Craft EE Firebaugh ML Graham AK Eichen DM Monterubio GE Balantekin KN et al . State-wide university implementation of an online platform for eating disorders screening and intervention. Psychol Serv. (2019) 16:239–49. doi: 10.1037/ser0000264

32

Bauer S Bilić S Ozer F Moessner M . Dissemination of an internet-based program for the prevention and early intervention in eating disorders. Z für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. (2020) 48:25–32. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000662

33

Moessner M Bauer S . Maximizing the public health impact of eating disorder services: A simulation study. Int J Eat Disord. (2017) 50:1378–84. doi: 10.1002/eat.22792

34

Taylor CB Ruzek JI Fitzsimmons-Craft EE Sadeh-Sharvit S Topooco N Striegel Weissman R et al . Using digital technology to reduce the prevalence of mental health disorders in populations: time for a new approach. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e17493. doi: 10.2196/17493

35

Grund K . Validierung der Weight Concerns Scale zur Erfassung von Essstörungen. Trier: Universität Trier (2003).

36

Nacke B Beintner I Görlich D Vollert B Schmidt-Hantke J Hütter K et al . everyBody-Tailored online health promotion and eating disorder prevention for women: Study protocol of a dissemination trial. Internet Interv. (2019) 16:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.02.008

37

Heier H . everyBody Basic – Ein Online-Kurzprogramm zur Gesundheitsförderung bei Frauen ohne Essstörungsrisiko. Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie. Dresden: Technische Universität Dresden (2017).

38

Ohlmer R Jacobi C Taylor CB . Preventing symptom progression in women at risk for AN: results of a pilot study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2013) 21:323–9. doi: 10.1002/erv.2225

39

Jacobi C Thiel A Beintner I . Anorexia und Bulimia nervosa. Ein kognitiv-verhaltenstherapeutisches Behandlungsprogramm. Weinheim: Beltz (2016).

40

Reinhardt A-K . Validierung eines prognostischen und diagnostischen Online-Screenings für Essstörungen. In: Fachrichtung psychologie. Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden (2017).

41

Killen JD Taylor CB Hayward C Wilson DM Haydel KF Hammer LD et al . Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: A three year prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. (1994) 16:227–38. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199411)16:3<227::AID-EAT2260160303>3.0.CO;2-L

42

Killen JD Taylor CB Hayward C Haydel KF Wilson DM Hammer L et al . Weight concerns influence the development of eating disorders: A 4-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1996) 64:936–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.936

43

Fairburn CG Beglin SJ . Eating disorder examination questionnaire. In: FairburnCG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guildford Press, New York (2008).

44

Hilbert A Tuschen-Caffier B . Eating disorder examination-questionnaire: deutschsprachige übersetzung. Münster: Verlag für Psychotherapie (2006).

45

Hilbert A Tuschen-Caffier B Karwautz A Niederhofer H Munsch S . Eating disorder examination-questionnaire. Eval der deutschsprachigen Übersetzung. Diagnostica. (2007) 53:144–54. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924.53.3.144

46

Tylka TL . Development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of intuitive eating. J Couns Psychol. (2006) 53:226–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.226

47

Herbert BM Blechert J Hautzinger M Matthias E Herbert C . Intuitive eating is associated with interoceptive sensitivity. Effects body mass index. Appetite. (2013) 70:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.082

48

Rosenberg M . Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1965) 11:326.

49

von Collani G Herzberg PY . Eine revidierte Fassung der deutschsprachigen Skala zum Selbstwertgefühl von Rosenberg. Z für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychol. (2003) 24:3–7. doi: 10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.3

50

Roth M Decker O Herzberg PY Brähler E . Dimensionality and norms of the rosenberg self-esteem scale in a german general population sample. Eur J Psychol Assess. (2008) 24:190–97. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.24.3.190

51

Ferring D Filipp S-H . Messung des Selbstwertgefühls: Befunde zu Reliabilität, Validität und Stabilität der Rosenberg-Skala. Diagnostica. (1996) 42:284–92.

52

Richardson J Elsworth G Iezzi A Khan MA Mihalopoulos C Schweitzer I et al . Increasing the sensitivity of the AQoL inventory for the evaluation of interventions affecting mental health. Melbourne: Centre for Health Economics, Monash University (2011).

53

Richardson J Iezzi A . Psychometric validity and the AQoL-8D multi attribute utility instrument Vol. 13. . Melbourne Australia: Centre for Health Economics Monash University (2011).

54

Richardson J Iezzi A Khan MA Maxwell A . Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. (2014) 7:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0036-x

55

Kroenke K Spitzer RL Williams JBW . The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Internal Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

56

Löwe B Kroenke K Herzog W Gräfe K . Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. (2004) 81:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8

57

Martin A Rief W Klaiberg A Braehler E . Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2006) 28:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003

58

Kocalevent R-D Hinz A Brähler E . Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35:551–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

59

Spitzer RL Kroenke K Williams JB Löwe B . A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Internal Med. (2006) 166:1092–97. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

60

Löwe B Decker O Müller S Brähler E Schellberg D Herzog W et al . Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

61

Görlich D Faldum A . Implementing online interventions in ICare: A biostatistical perspective. Internet Interv. (2019) 16:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.12.004

62

ICH E9 Expert Working Group . Statistical principles for clinical trials. Stat Med. (1999) 18:1905–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990815)18

63

White IR Carlin JB . Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Stat Med. (2010) 29:2920–31. doi: 10.1002/sim.3944

64

Heitjan DF Little RJ . Multiple imputation for the fatal accident reporting system. J R Stat Society: Ser C (Applied Statistics). (1991) 40:13–29. doi: 10.2307/2347902

65

Schenker N Taylor JMG . Partially parametric techniques for multiple imputation. Comput Stat Data Anal. (1996) 22:425–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-9473(95)00057-7

66

Rubin DB . Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons (1987).

67

Eysenbach G . The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. (2005) 7:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11

68

Christensen H Griffiths KM Farrer L . Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2009) 11:e1194. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194

69

Sanatkar S Baldwin P Huckvale K Christensen H Harvey S . e-mental health program usage patterns in randomized controlled trials and in the general public to inform external validity considerations: sample groupings using cluster analyses. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e18348. doi: 10.2196/18348

70

Graham AK Wildes JE Reddy M Munson SA Barr Taylor C Mohr DC . User-centered design for technology-enabled services for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. (2019) 52:1095–107. doi: 10.1002/eat.23130

71

Vollert B von Bloh P Eiterich N Beintner I Hütter K Taylor CB et al . Recruiting participants to an Internet-based eating disorder prevention trial: Impact of the recruitment strategy on symptom severity and program utilization. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:476–84. doi: 10.1002/eat.23250

72

Levine MP . Prevention of eating disorders: 2018 in review. Eat Disord. (2019) 27:18–33. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2019.1568773

Summary

Keywords

eating disorders, health promotion, internet-based intervention, population-based prevention, prevention, public health, women’s health

Citation

Nacke B, Görlich D, Beintner I, Vollert B, Schmidt-Hantke J, Taylor CB and Jacobi C (2026) Tailored online eating disorder prevention and health promotion for women: results of a dissemination trial. Front. Psychiatry 16:1731066. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1731066

Received

23 October 2025

Revised

06 December 2025

Accepted

24 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Stefania Landi, ASL Salerno, Italy

Reviewed by

Paolo Meneguzzo, University of Padua, Italy

Michael Leon, University of California, Irvine, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Nacke, Görlich, Beintner, Vollert, Schmidt-Hantke, Taylor and Jacobi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Barbara Nacke, barbara.nacke@tu-dresden.de

Deceased

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.