- 1Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 2Xiangya School of Nursing of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

Background: Regular exercise may boost cognition in older adults with MCI, but the effectiveness of different aerobic exercise (AE) modalities is unclear. We conducted a meta-analysis to assess AE’s impact on cognition in this group.

Objective: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effects of AE on cognitive function in older adults with MCI.

Methods: We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library up to July 2025 and referenced included articles. RCTs with aerobic exercise and outcomes for global cognition and specific cognitive domains in older MCI adults were included. Data was pooled using mean difference, standardized random-effect model, and 95% CI with RevMan V.5.4 and Stata 16.0.

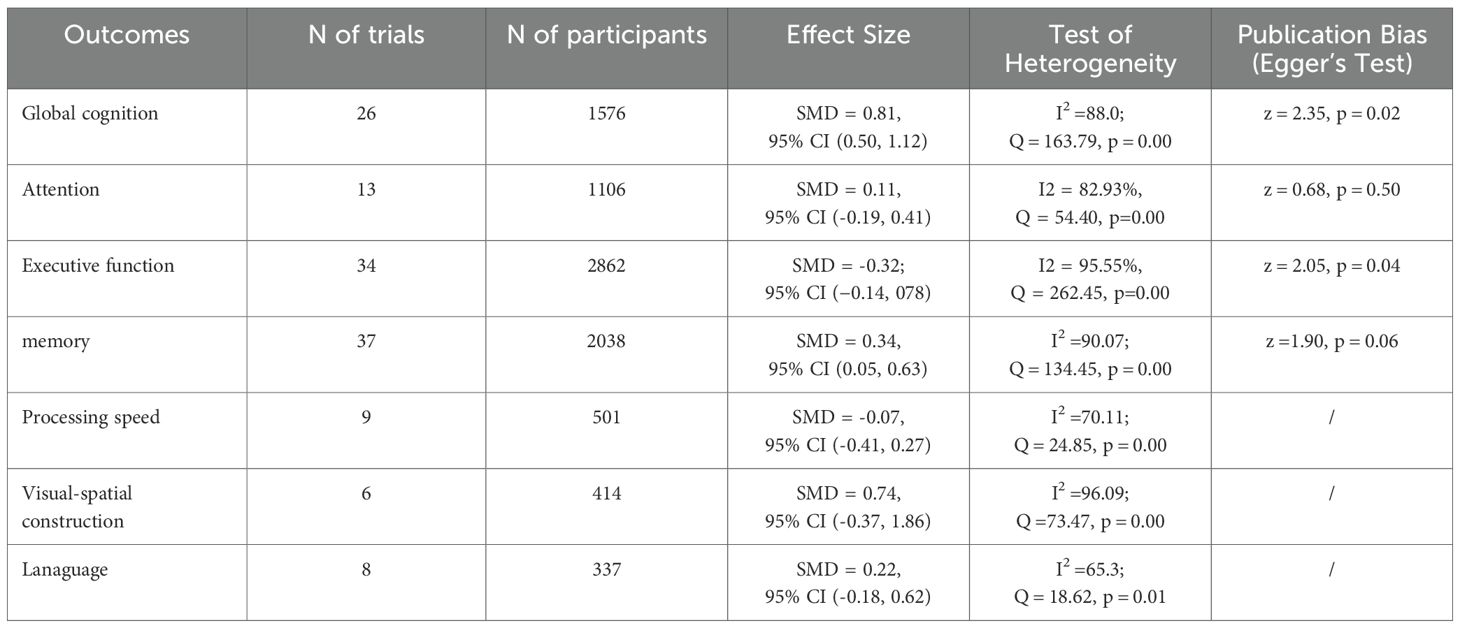

Results: A total of 33 studies with 1996 participants were included. The results revealed that AE exerted a significant positive effect on global cognition (SMD = 0.81, 95% CI (0.50, 1.12), Z = 5.07, p=0.00) and a moderate positive effect on memory (SMD = 0.34, 95% CI (0.06, 0.63); Z = 2.33, p = 0.02). Notably, no significant improvements were observed in executive function, attention, processing speed, language, or visuospatial abilities. Furthermore, meta-regression and subgroup analyses indicated statistically significant variations across different intervention combinations, suggesting heterogeneity in treatment effects.

Conclusion: AE significantly improved global cognition and memory in elderly individuals with MCI. Furthermore, the frequency (3–5 sessions per week), timing, intensity, and total duration of the interventions should be tailored to individual needs and gradually refined for personalized optimization.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42021238308.

Introduction

The accelerating aging of the global population has led to a significant increase in the risk of MCI among adults agedtss years, with prevalence rates rising sharply with advancing age. For instance, the prevalence is 6.7% in adults aged 60–64 years but rises dramatically to 25.2% among those aged 60 years and above (1, 2). Other studies have reported that approximately 15% of adults aged > 60 years are affected by MCI (3). Among those affected, individuals with amnestic MCI (aMCI), characterized by substantial memory decline, are at a significantly higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease(AD). In contrast, those with non-amnestic MCI (naMCI) primarily exhibit deficits in other cognitive domains, such as executive function and language (4). Compared to cognitively healthy peers, individuals with MCI face a markedly elevated risk of dementia progression. The conversion rate for MCI patients aged 65 and above is approximately 14.9% within 2 years and rises to 23.8-46% within 3 years (4, 5). Although an estimated 10tima of individuals may experience cognitive stability or even improvement (6), the lack of effective, timely interventions poses a substantial socioeconomic burden, with associated costs projected to soar to US$2.54 trillion by 2030 (7). This escalating burden underscores the urgent need for effective prevention and treatment strategies in global public health initiatives (8–10). Given the limited efficacy and lack of consensus regarding pharmacological interventions (e.g. acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) (11, 12), non-pharmacological approaches, including cognitive training, dietary modifications, and social engagement, have emerged as primary strategies for mitigating cognitive decline (13, 14).

Among the array of non-pharmacological interventions for MCI, exercise has garnered significant attention for its cost-effectiveness and practicality (15, 16). Among the various exercise modalities, aerobic exercise (AE) offers distinct advantages owing to its unique neuroprotective mechanism. Research indicates that AE not only enhances cardiopulmonary fitness, increases cerebral blood flow, and promotes hippocampal neuroplasticity (17, 18) but also confers neuroprotective benefits via multiple pathways, including reducing amyloid-g deposition (19–21) and mitigating oxidative stress (22–24). Recent high-quality evidence reviews have further clarified the overall benefits of AE for individuals with MCI (25–27). Nevertheless, the specific effects of AE on cognitive function in older adults with MCI remain inconsistent. For example, a network meta-analysis identified moderate-intensity AE as a highly effective intervention for enhancing global cognition in this population (25). Similarly, an umbrella review affirmed the positive impact of exercise (including AE) on cognitive impairment but emphasized that significant heterogeneity in exercise type, dosage, and assessment tools contributes to inconsistent findings (27). Furthermore, research comparing different exercise modalities for alleviating neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI underscores the importance of tailored intervention strategies (26). Therefore, this study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the effects of AE on cognitive function in older adults with MCI. The specific objectives are: (1) to determine the overall efficacy of AE for improving cognition in MCI; (2) to explore, via subgroup analysis and meta-regression, the relationship between specific exercise parameters (e.g., frequency, intensity, duration) and cognitive outcomes; and (3) to provide an evidence-based foundation for developing standardized and feasible AE intervention protocols.

Methods

The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42021238308).

Literature research

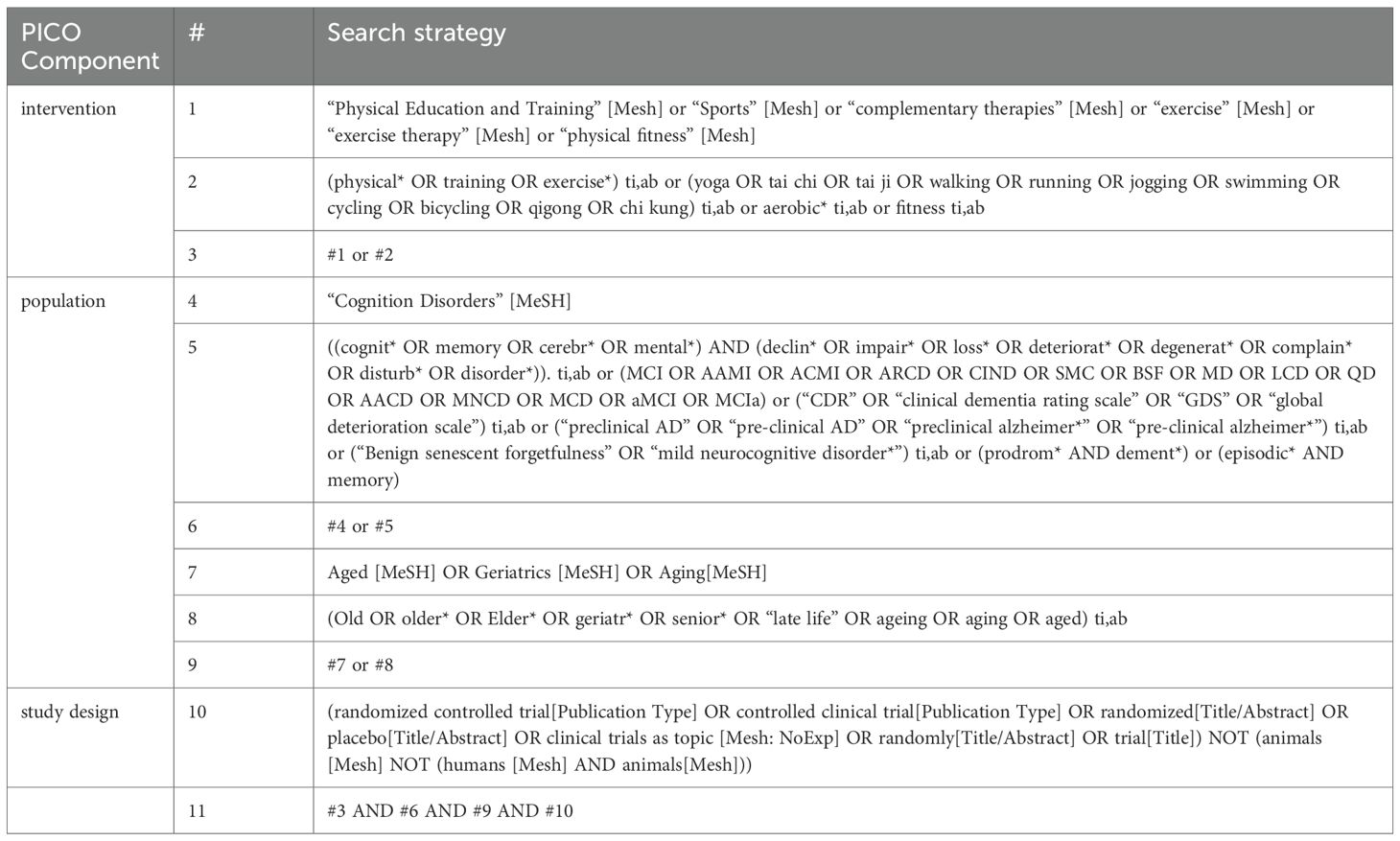

For a more comprehensive literature search, two investigators independently searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Web of Science for relevant literature from inception to July 2025. The search phrases used were: (“Cognition Disorders” or (“cogniti*” or “impair*”)) and (“exercise” or “physical activity” or “fitness” and (“Geriatrics” or “Aged”). Hand searching was also performed to identify additional relevant publications from the reference lists of all articles. The complete search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis: (1) Participants: older adults aged 60 years and above who met the diagnostic criteria for MCI, Individuals aged ≥ 60 years are considered older according to WHO (28). (2) Interventions: Aerobic exercise (29), also referred to as endurance activities, entails rhythmic movement of the body’s large muscle groups over a sustained duration. This form of exercise is renowned for enhancing cardiovascular and pulmonary health and includes popular activities such as walking, running, swimming, and cycling. (3) Any type of control group was eligible, including no treatment, a waiting list, or an alternative active treatment group. (4) Outcome measurements involving global cognition, memory (immediate and delayed recall), executive function, attention, language, and visuospatial function; (5) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Conference abstracts, case reports, commentary articles or letters to the editor, and protocols were excluded. Studies including elderly patients with vascular cognitive impairment or other neurological disorders resulting from AD, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, cardiovascular disease, or other severe illnesses were also excluded. In addition, when duplicate or overlapping data were found in multiple reports, only the report with the most complete information was included.

Data extraction

Two independent authors (ZQ and HZC) evaluated the eligible studies and extracted data using a self-designed information extraction form. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by the judgment of a third reviewer (ZH). The following information was extracted from each study: author, country, study type, participants (age, sex, sample size, and percentage), intervention (type, duration, frequency, and intensity), and outcome. We extracted the means and standard deviations to compute effect sizes. The direction of the effect size was adjusted such that a positive effect size indicated an improvement in the outcome measures.

Risk of bias assessment

Two independent reviewers (ZQ and HZC) assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (30). The overall rating is determined by evaluating the six aspects of each study (Selection Bias, Performance Bias, Detection Bias, Attrition Bias, Reporting Bias, and other Biases) as low risk, high risk, and unclear. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussions.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) and Stata 16. Hedges’ adjusted g was used to calculate the effect sizes for the standardized mean difference (SMD). SMD was preferred over Mean Difference (MD) because of the use of different instruments to measure cognitive outcomes in the included studies. SMD standardizes results across diverse scales, enabling the comparison of effect sizes despite different measurement tools (31). This approach ensured a more consistent and interpretable summary of the intervention effects on cognitive function. SMD values of 0.15–0.40, 0.40–0.75, and over 0.75 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively (32). Random-effects models were used to pool the summary SMD. Tests for heterogeneity were conducted and assessed using I2 and Q statistics. An I2 of less than 25%, 25%–50%, and over 50% was usually viewed as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (33). A p-value of < 0.05 for the Q statistic and I2 > 50% reflected significant heterogeneity. Egger’s tests and a contour-enhanced funnel plot were created to check for publication bias (34).

Additionally, a meta-regression analysis was performed to explore the sources of heterogeneity among studies and systematically evaluate the effects of potential moderator variables on the research outcomes (35). Subsequently, subgroup meta-analyses were performed based on the moderator variables identified as significant in the meta-regression analysis. This approach facilitates a deeper exploration and elucidation of the influence of these moderator variables on effect sizes within more homogeneous subsets (36). These analyses assessed the moderating effects of intervention frequency, duration, intensity, and intervention (i.e. dance, bicycle, walking, Tai Chi) and control (i.e. usual care, placebo, health education, others) types.

Results

Search process

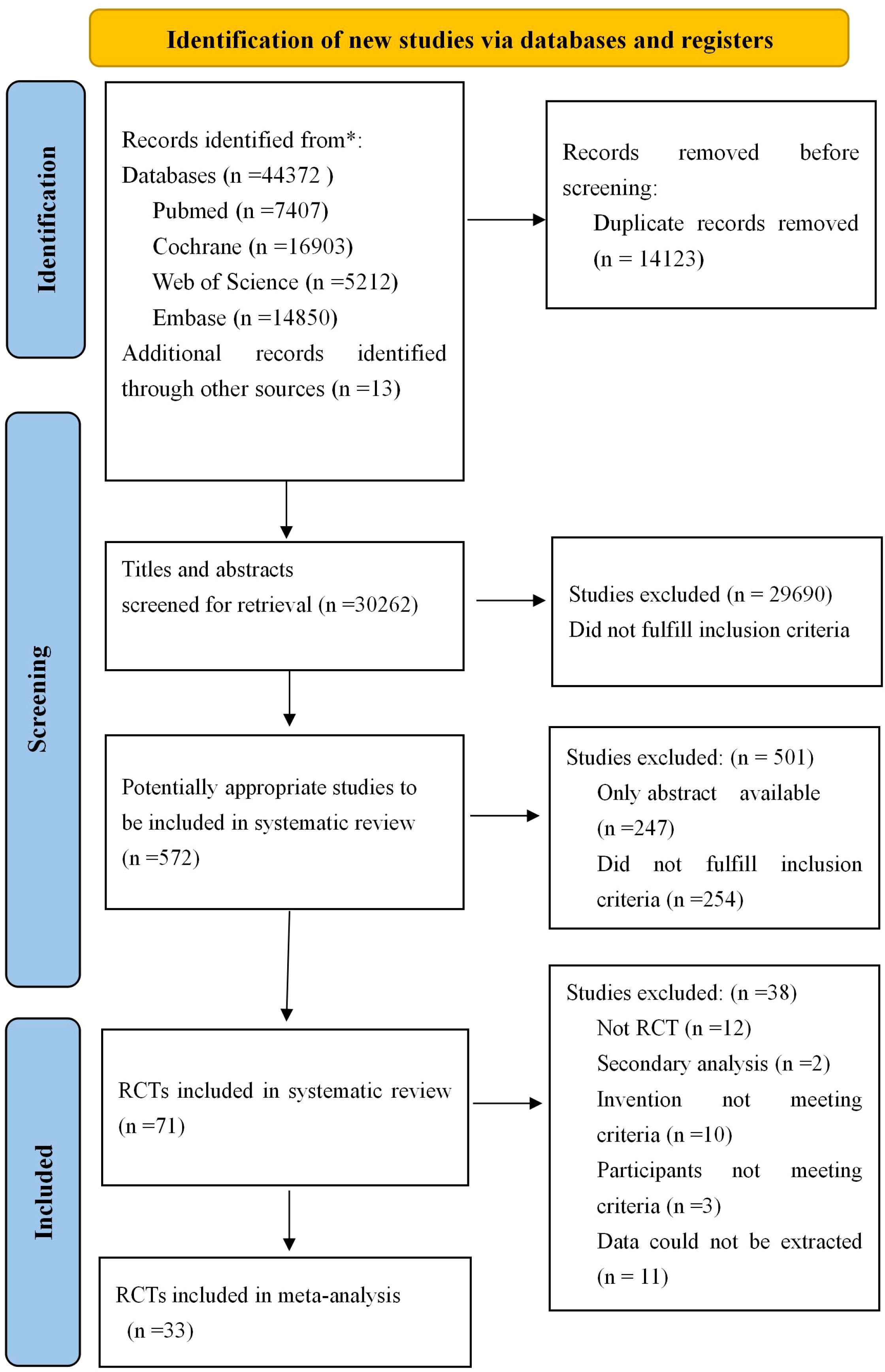

The results of the search are presented in Figure 1. A total of 44372 studies were identified from four databases, and 13 studies were obtained from citations related to references. A total of 14123 were removed because of duplication. After screening the titles and abstracts, 29690 studies were excluded, leaving 572 studies with full texts to be checked for eligibility. Of these, 247 were protocol/conference abstracts, 254 did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, 12 were non-RCTs, and two studies (37, 38) were secondary analyses from one study that produced more than one publication; thus, they were regarded as one study. The intervention method is multi-component intervention (39–48), three studies did not meet the inclusion criteria (49–51) and 11 were excluded due to insufficient data. Ultimately, 33 studies were included in this review.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for searching and selection of the included studies. RCTs, Randomized controlled trials.

Study characteristics

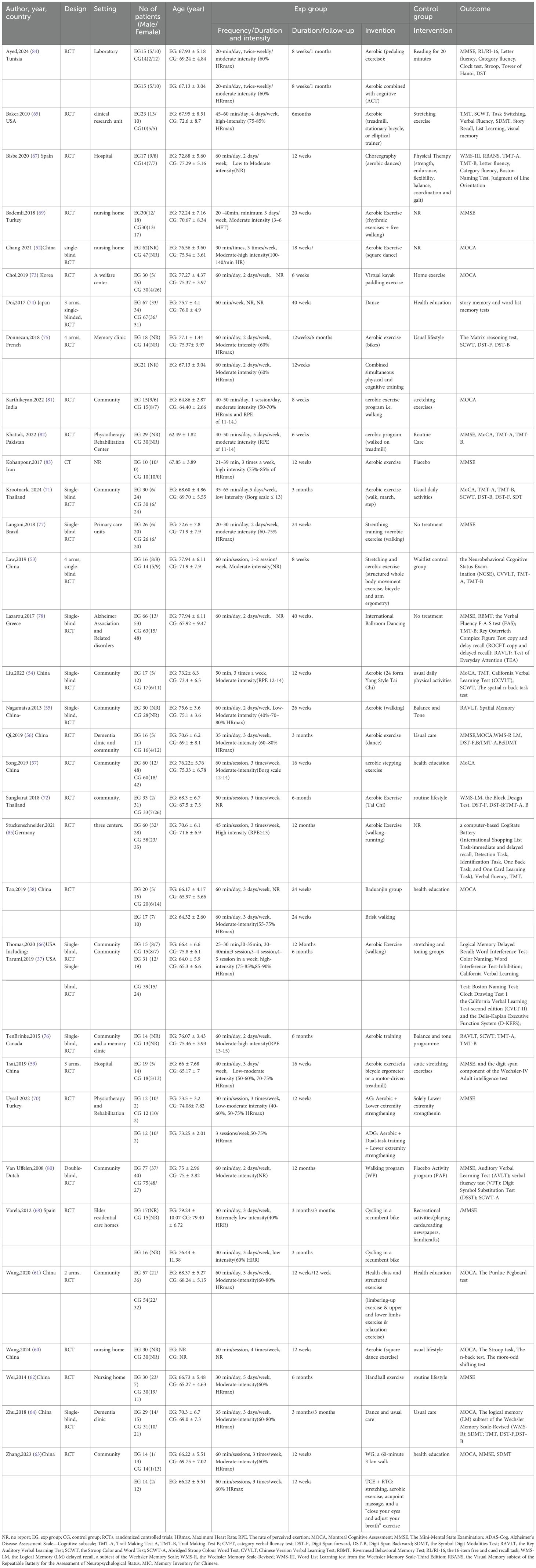

The detailed characteristics of the 33 studies included in this analysis are listed in Table 2. A total of 33 RCTS, involving 1996 participants with MCI (men, 640; women, 1010; mean age 71.44) were included, of whom 1004 were allocated to the intervention groups and 992 to the control groups. All studies were published between 2008 and 2024. The study countries and regions included China (52–64)(n=13), USA (65, 66)(n=2), Spain (67, 68)(n=2), Turkey (69, 70)(n=2), Thailand (71, 72)(n=2), Korea (73)(n=1), Japan (74) (n=1), French (75) (n=1), Canada (76) (n=1), Brazil (77) (n=1), Greece (78) (n=1), Germany (79) (n=1), Dutch (80) (n=1), India (81) (n=1), Pakistan (82) (n=1), Iran (83) (n=1), Tunisia (84)(n=1). In terms of intervention characteristics, the type of aerobic exercise included walking (55, 63, 66, 69, 71, 77, 80, 81, 85) (n=9), treadmill or bicycle (53, 59, 65, 68, 75, 82) (n=6), dance (552, 56, 60, 64, 67, 74, 78) (n=7), pedaling exercise (84)(n=1) kayak (73) (n=1), Handball (62)(n=1), stepping (57) (n=3), Taichi (54, 72)(n=2) and Baduanjin (58)(n=1). The duration of aerobic exercise was, on average, 19 weeks (range =8–48 weeks) with 3 sessions per week (range =1–7 sessions) of 20–60 minutes in volume in the 33 studies, a heart rate reserve of 40–60%, 40–90% maximum heart rate, Rating of Perceived Exertion(RPE) 11-15, Borg scale12-14, or metabolic equivalents were applied to control the intensity of aerobic exercise in 25 studies included studies. Among the 33 articles, 16 studies clearly indicated the adoption of moderate-intensity exercise, two studies adopted low or extremely low-intensity exercise (68, 71), four studies adopted high-intensity exercise (65, 66, 79, 83), and one study used the intensity of exercise that varied with the duration of intervention (52, 55, 59, 67, 70, 76) (Table 2).

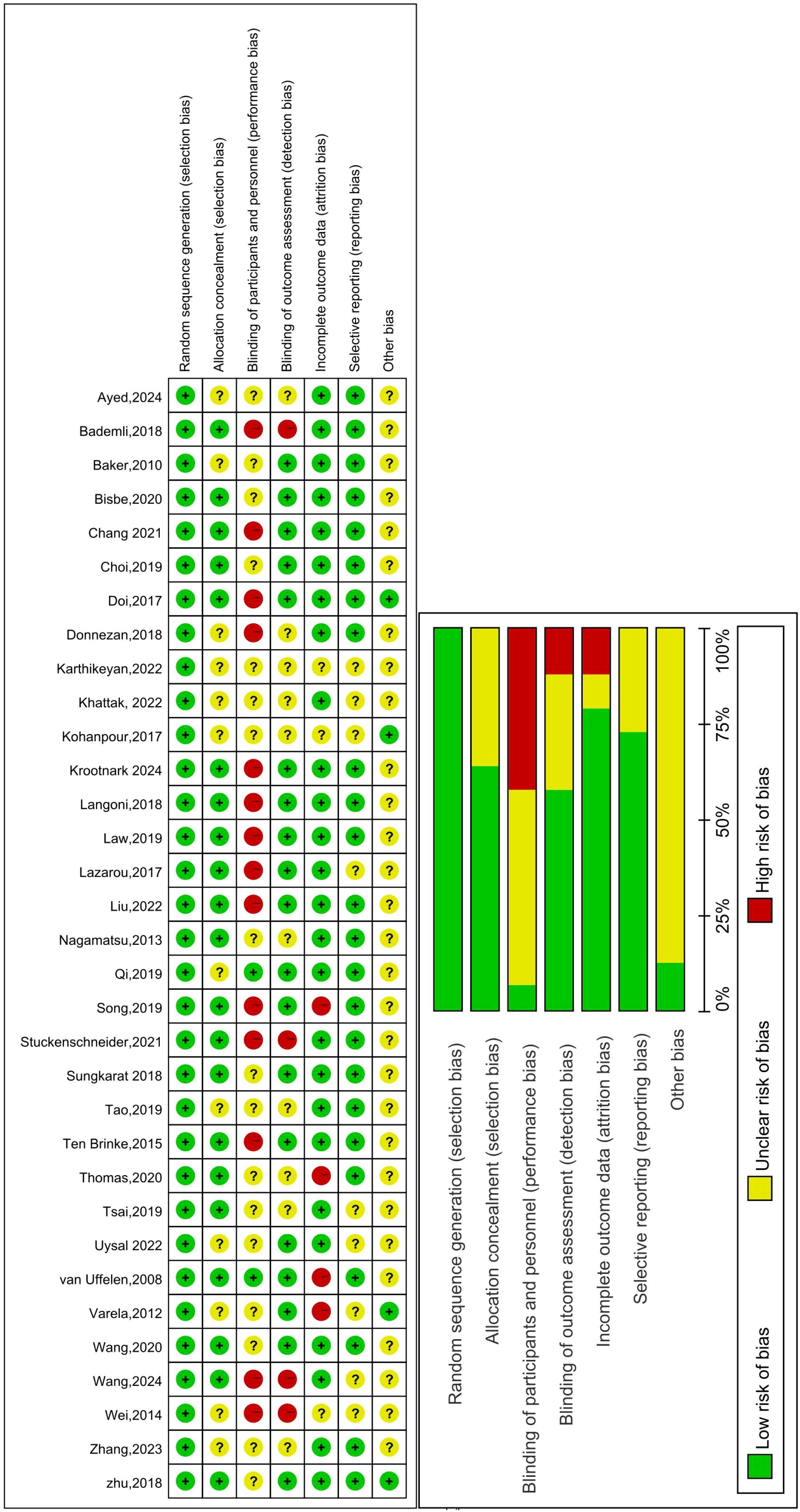

Risk of bias

We conducted a risk of bias assessment for the included studies. The risk of bias and specific percentages (high, unclear, or low risk) are shown in Figure 2. Regarding the selection bias, all studies included reported random allocation, 21 studies of them reported the specific method of generated random number using computer (53, 55, 57, 61, 64, 71, 72, 74, 79), software(SPSS, Stata, Excel, SAS) (60, 66, 67, 73, 77, 78, 80), draw lots (52), URL (69, 76). Only two studies clearly indicated the method of allocation concealment using sealed and opaque envelopes (54, 59). Due to the type of intervention, it is difficult to blind the participants; therefore, the performance bias is high, and only two studies blinded the participants (56, 80). Nineteen studies adopted blinding to outcome evaluators (52–54, 56, 57, 61, 64, 65, 67, 68, 70–74, 76–78, 80), so the detection bias was low. In the attrition bias, studies were considered high risk since the dropout rate was higher than 20% (57, 66, 68, 80). We considered the reporting bias were low risk, since all the outcomes were reported, except in some studies that lacked research registration information.

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary: Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Green circle: The risk of bias was low. Red circle: The risk of bias was high. Yellow circle: The risk of bias was unclear.

Effects of aerobic exercise intervention on MCI

Primary outcome: global cognition

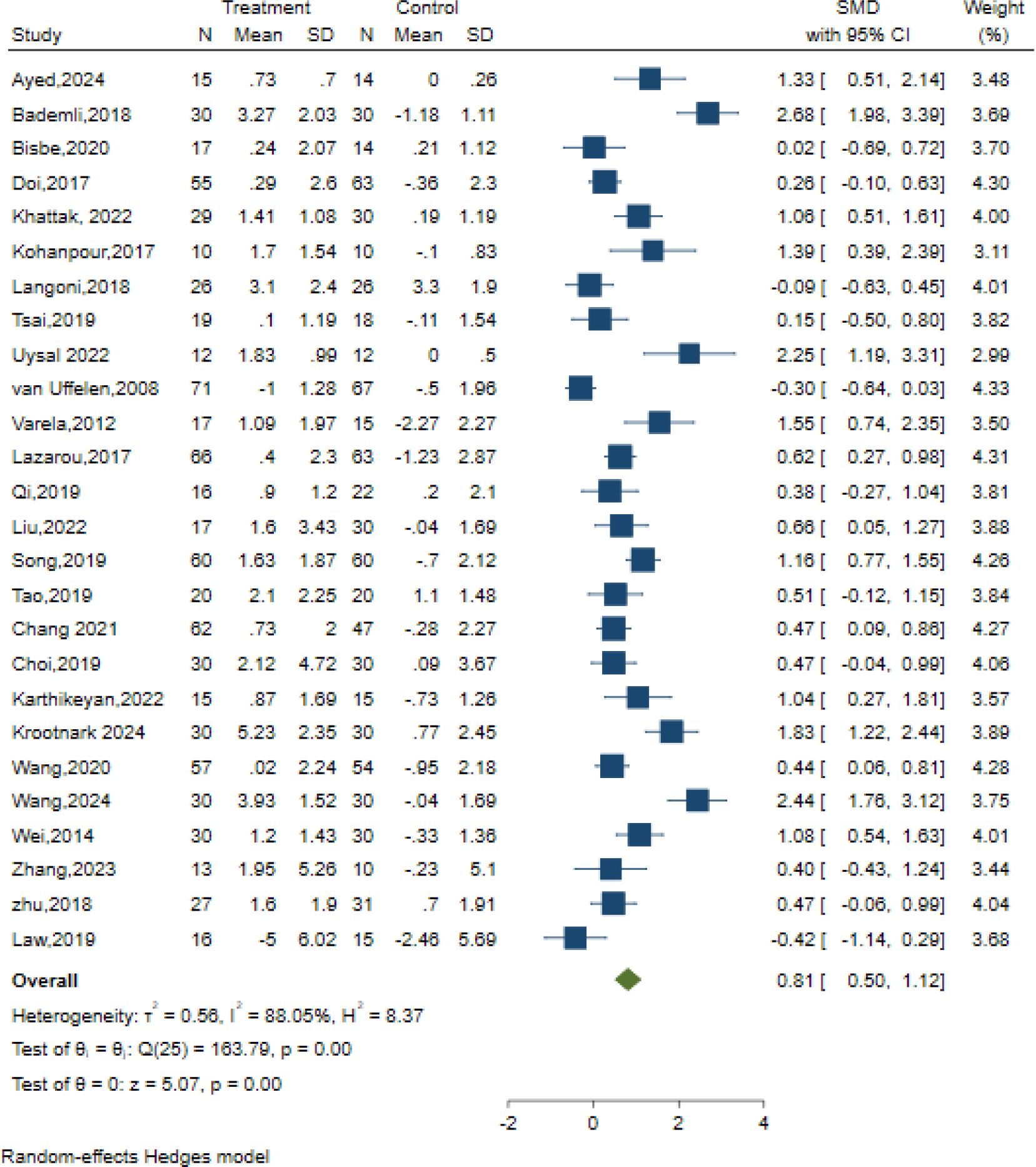

26 studies examined the effects of AE on global cognition using different classic and sensitive tests, including the MMSE, MoCA, and the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination (NCSE). The intervention group presented substantial improvement in global cognition relative to the control condition, using a random effects model. [SMD = 0.81, 95% CI (0.50, 1.12), Z = 5.07, p=0.00; I2 = 88.05%, p<0.01] (Figure 3). The contour-enhanced funnel plot showed that no study was trimmed; however, Egger’s regression test (z = 2.35, p = 0.02) suggested a potential publication bias (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1).

Additionally, the meta-regression analysis indicated that AE Duration (min) had a statistically significant impact on effect size. Subgroup analysis was performed to assess the duration of AE interventions, which demonstrated that a duration of ≥30-≤50 min [SMD = 1.00, 95% CI (0.45, 1.55)], > 50 min [SMD = 0.30, 95% CI (0.00, 0.61)], and change in exercise duration[SMD = 1.31, 95% CI (0.57, 2.04)] conferred cognitive outcomes in older adults with MCI, Among which the duration of exercise exhibited the most significant variation in effect size and demonstrated the most optimal cognitive enhancement for older adults with MCI (Figure 3). The remaining meta-regression analyses showed that none of the moderators had a statistically significant impact on effect size. Specifically, the AE period in weeks did not significantly impact global cognition (z=-1.47, p = 0.14); similarly, the frequency of sessions per week (z=1.92, p = 0.06), Intervention Intensity (z=-0.15, p = 0.88), intervention type (z=0.17, p = 0.86), control type(z=0.04, p = 0.97), and scale type(z=-0.33, p = 0.74) showed no significant effect on the results. (Supplementary Table S1).

Despite these factors, we performed subgroup analyses concerning the overall duration of the intervention, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the nature of the control group. Our findings revealed that aerobic exercise lasting ≤12 weeks[SMD = 0.93, 95% CI (0.54, 1.32)] exhibited a more significant intervention impact than exercise lasting > 12 weeks[SMD = 0.64, 95% CI (0.11, 1.16)]. Regarding intervention frequency, optimal results were observed when the sessions were conducted 3–5 times weekly [SMD = 1.08, 95% CI (0.70, 1.46)]. Regarding intervention intensity, low-intensity interventions emerged as the most effective [SMD = 1.20, 95% CI (0.16, 2.25)]. Among the diverse intervention types, walking interventions [SMD = 0.93, 95% CI (0.15, 1.72)] were more beneficial than dance interventions [SMD = 0.65, 95% CI (0.06, 1.25)]. Additionally, within the control group categories, stretching exercises [SMD = 1.10, 95% CI (-0.09, 2.29)] displayed the most favorable outcomes (Supplementary Figures S2A–E).

Secondary outcomes: cognitive sub-domains

Apart from the effects on global cognition, most studies also examined the effects of AE on specific cognitive sub-domains, including executive functions, memory, attention, language, processing speed, and visuospatial function.

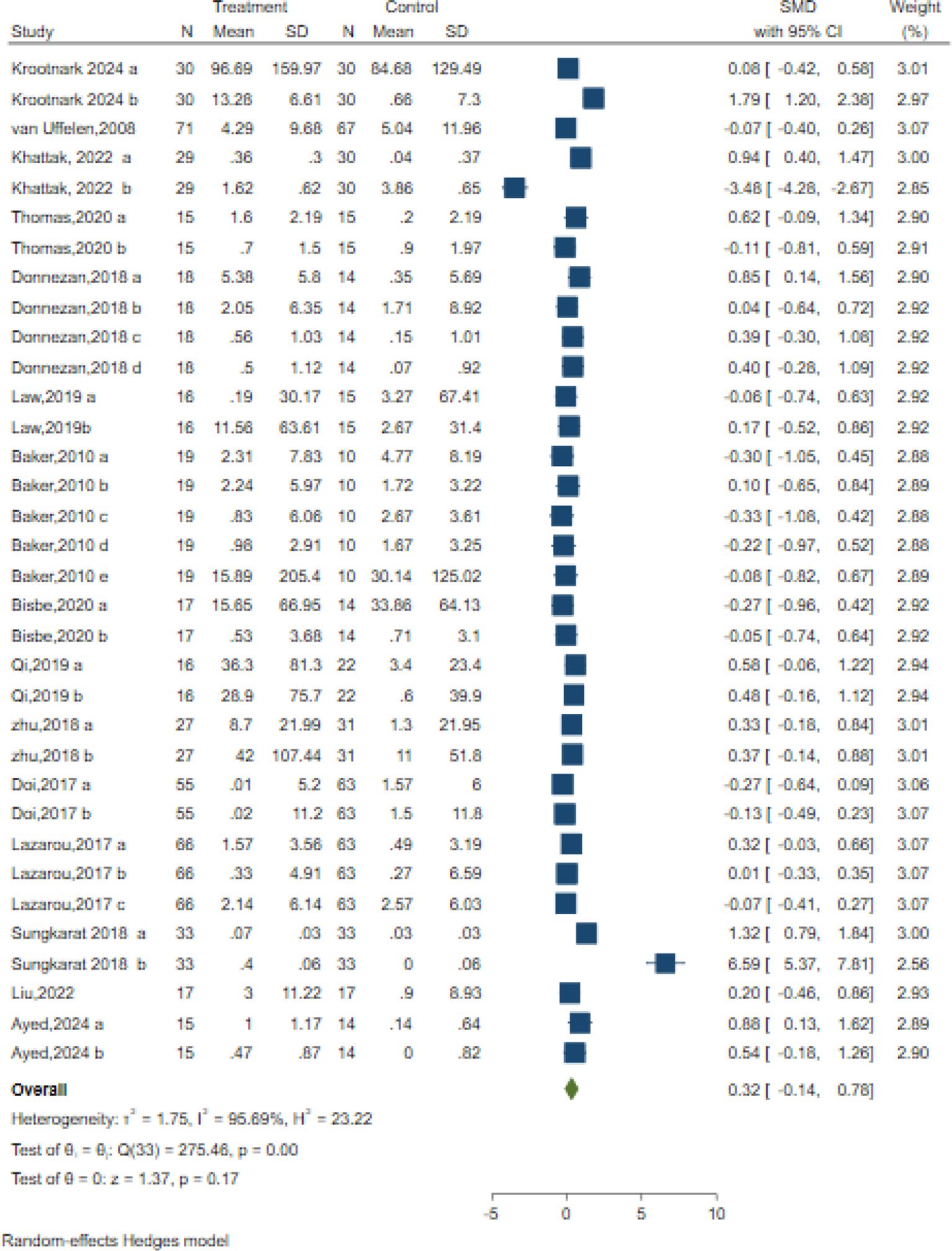

Executive function

Executive functions are a comprehensive cognitive domain, which includes functions like planning, problem solving, set shifting and inhibition (86) 34 controlled trials in 15 studies evaluated the effects on executive functions but used different classic and sensitive tests, including the Verbal Fluency Test (VFT), Stroop-Colour Test (SCT), Trail-Making Test (TMT), Matrix Reasoning test, Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure Test and Digit Span Test individually or in combination. A random-effects meta-analysis for executive function showed no significant changes in executive function [SMD = 0.32; 95% CI (−0.14, 078); Z = 1.37, p = 0.17; I2 = 95.69%, Q = 275.46, p=0.00] (Figure 4). Both Egger’s test (z = 2.05, p = 0.04) and contour-enhanced funnel plot suggested a potential risk of publication bias (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1).

Additionally, the meta-regression analysis indicated that none of the moderators had a statistically significant impact on the effect size. Specifically, the AE period (z=-0.03, p = 0.97), duration of each session in minutes (z=-0.76, p = 0.45), frequency of sessions per week (z=-0.60, p = 0.55), Intervention Intensity (z=-1.32, p = 0.19), intervention type (z=1.66, p = 0.10), and control type(z=-1.02, p = 0.31) showed no statistically significant differences (Supplementary Table S1).

We also performed subgroup analyses concerning the overall length of the intervention, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the type of control group. Our findings revealed that only the duration of intervention and the type of control group had a significant positive impact on executive function. Specifically, interventions lasting ≥30-≤50 min demonstrated the most prominent improvement in executive function[SMD = 1.37, 95% CI (-0.34, 3.08)]. Among control group types, interventions showed optimal efficacy when compared to usual care (SMD = 0.70, 95% CI: -0.30 - 1.71) or reading (SMD = 0.70, 95% CI: -0.19 -1.22). Given the inclusion of only two studies, this research suggests that interventions have the most significant effects when the control group receives usual care (Supplementary Figures S3A–F).

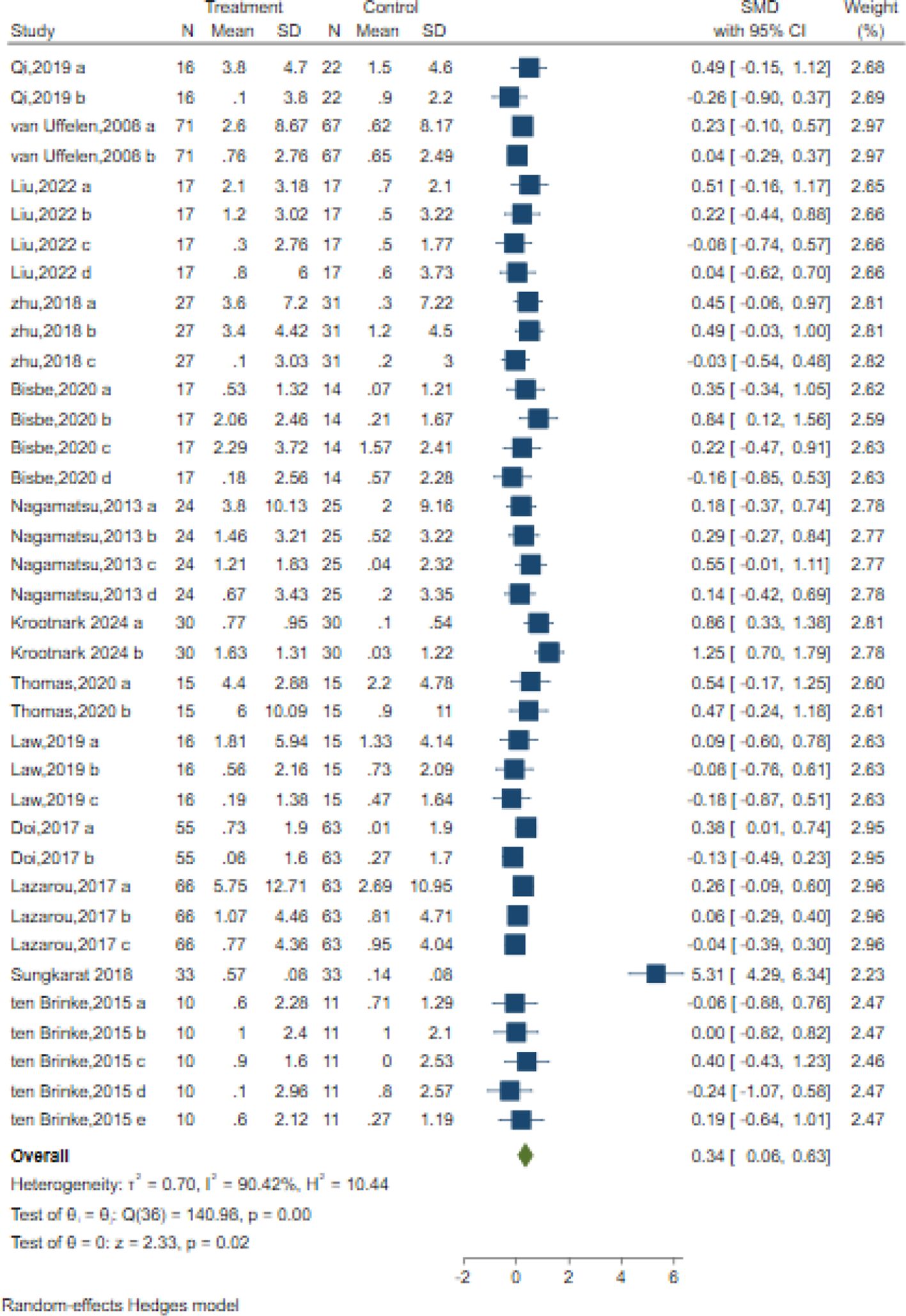

Memory

In total, 37 trials in 14 studies measured memory in older adults with MCI using different classic and sensitive tests, including the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT), Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-II, WMS-III), Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R), Digit Span Test (DST-F, DST-B), spatial n-back task test, Visual Memory subtest of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), and list learning delayed recall test. The results indicated that the intervention significantly improved memory with a moderate effect size compared to the control intervention [SMD = 0.34; 95% CI (0.06, 0.63); Z = 2.33, p = 0.02, I2 = 90.42%, Q = 140.98, p=0.00] (Figure 5). Among them,16 trials in six studies measured verbal memory. A small positive effect was reported after AE intervention compared to the control intervention [SMD = 0.11; 95% CI (-0.06, 0.28); Z = 1.27, p = 0.20, I2 = 0.29%, Q = 15.73, p=0.40] (Figure 5). Although Egger’s test indicated no evidence of publication bias (z = 1.90, p = 0.06), the results of the contour-enhanced funnel plot suggested that some studies were trimmed, implying a potential risk of publication bias (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1).

The meta-regression analysis in Supplementary Table S1 indicates that neither the intervention period (z=-0.18, p = 0.86) nor session frequency (z=1.53, p = 0.13) had a significant effect on memory. Additionally, duration (z=-0.58, p = 0.56) and intervention intensity (z=-1.23, p = 0.21) did not significantly impact the outcomes. Intervention types (z=1.61, p = 0.11) and control types (z=-0.90, p = 0.37) also did not differ significantly from no intervention (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, no significant moderators were identified for the memory.

We also performed subgroup analyses concerning the overall length of the intervention, duration, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the type of control group. Our findings revealed that the overall length of the intervention, duration, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention all had a significant positive impact on memory. Specifically, the duration varied in exercise progress [SMD = 0.84, 95% CI (0.50, 1.17)], intervention frequency ≤ 3times/week [SMD = 0.14, 95% CI (0.03, 0.25)], intervention intensity varied in exercise progress [SMD = 0.23, 95% CI (0.06, 0.42)], and the over length ≤12 weeks[SMD = 0.27, 95% CI (0.10, 0.44)] demonstrated the most prominent improvement in memory. Among the intervention group types, walking interventions showed optimal efficacy (SMD = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.20 – 0.64). Similarly, given the current inclusion of only one or two studies in intensity, this research suggests that intervention intensity varies in exercise progress, exhibiting the most significant effects (Supplementary Figures S4A–F).

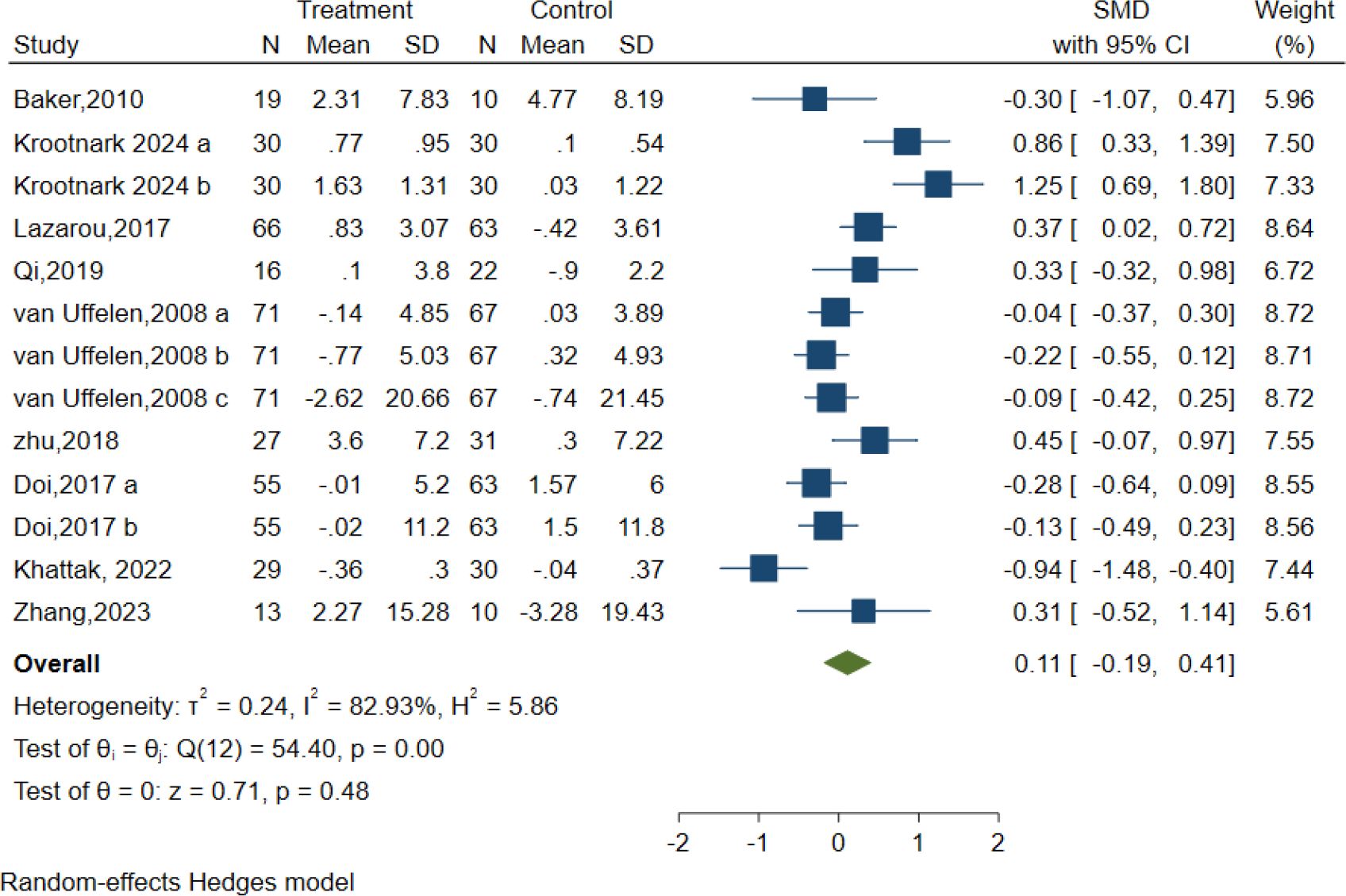

Attention

In total, 13 controlled trials in nine studies examined the impact of AE on attention using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), Digit Span Test (DST-F, DST-B), Test of Everyday Attention (TEA 4), and Abridged Stroop Colour Word Test (SCWT-A). Regardless of the assessments applied to assess the intervention effects on the attention domain. The intervention group presented no substantial improvement in attention relative to the control condition, as demonstrated by the random effect model [SMD = 0.11; 95% CI (-0.19, 0.41); Z = 0.71, p = 0.48, I2 = 82.93%, Q = 54.40, p=0.00] (Figure 6). The contour-enhanced funnel plot showed that no study was trimmed, and Egger’s regression test (z = 0.68, p = 0.50) suggested no potential publication bias (Table 3, Supplementary Figure S1).

Additionally, meta-regression analysis indicated that AE intensity had a minor statistical impact on effect size. A subgroup analysis was performed to assess the intensity of AE interventions, which demonstrated that moderate intensity conferred a very minor optimal attention in elderly individuals with MCI [SMD = -0.05, 95% CI (-0.40, 0.29), I2 = 75.14%, p=0.01] (Figure 6). The remaining meta-regression analyses showed that none of the moderators had a statistically significant impact on effect size. Specifically as follows: AE period in weeks did not significantly impact attention (z=-1.13, p = 0.26); Similarly, the duration of each session in minutes (z=-0.04, p = 0.96), frequency of sessions per week (z=0.66, p = 0.51), intervention type (z=0.03, p = 0.97) and control type(z=-1.43, p = 0.15) showed no significant effect on the results. (Supplementary Table S1).

Subgroup analyses were also conducted concerning the overall length of the intervention, frequency, type of intervention, and type of control group. Our findings revealed that none of these factors had a significant impact on attention (Supplementary Figures S5A–E).

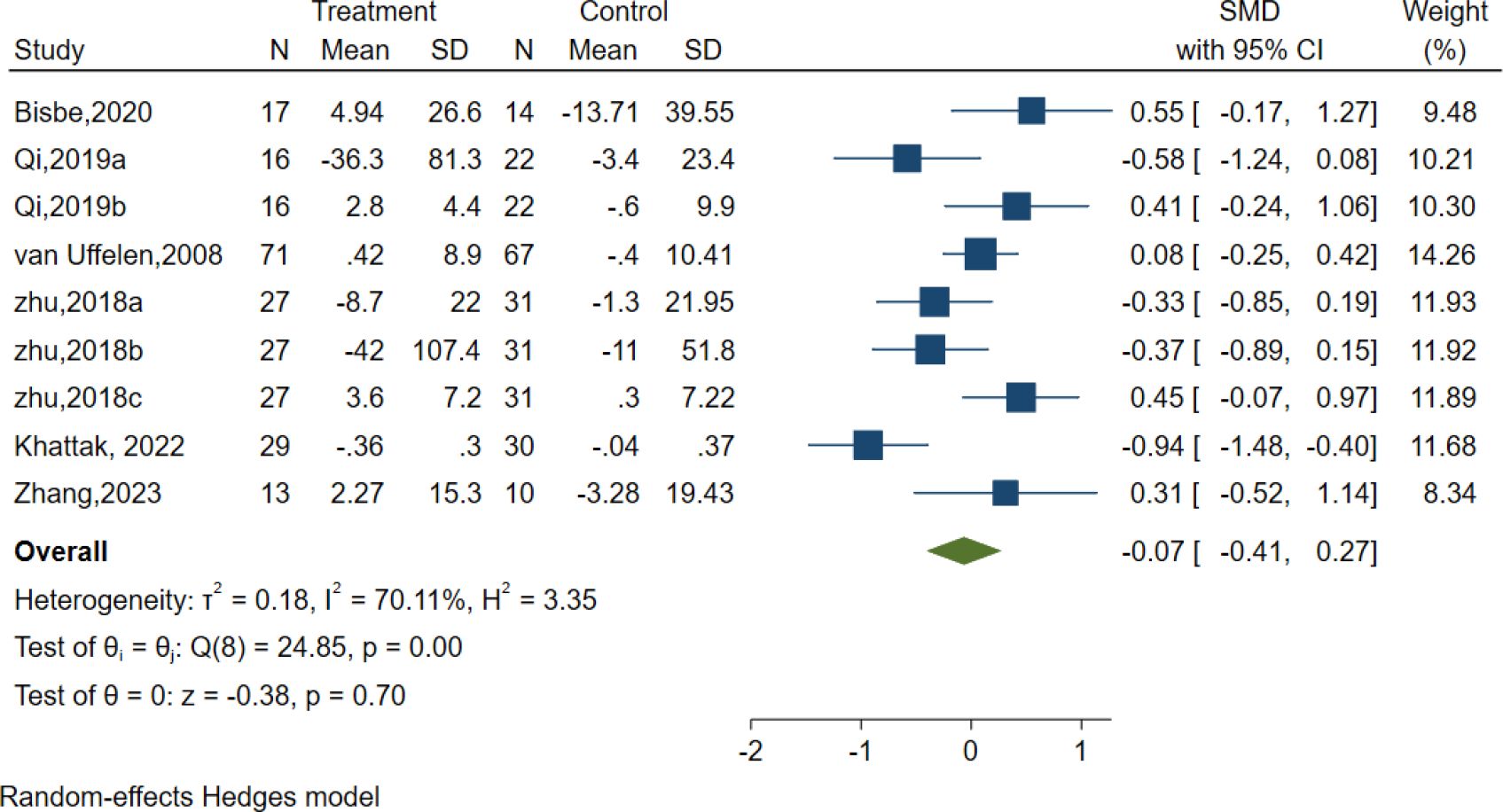

Processing speed

Six studies evaluated the effects of AE on Processing speed using different classic and sensitive tests, including the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), Trail-Making Test (TMT), and Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST). However, the results indicated no significant effect of AE in the Processing speed [SMD =-0.07, 95% CI (−0.41, 0.27), p = 0.70; I2 = 70.11%, Q = 24.85, p = 0.00] (Figure 7).

Subgroup analyses were also conducted concerning the overall length of the intervention, duration, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the type of the control group. Our findings revealed that none of these factors had a significant impact on attention (Supplementary Figures S6A–F).

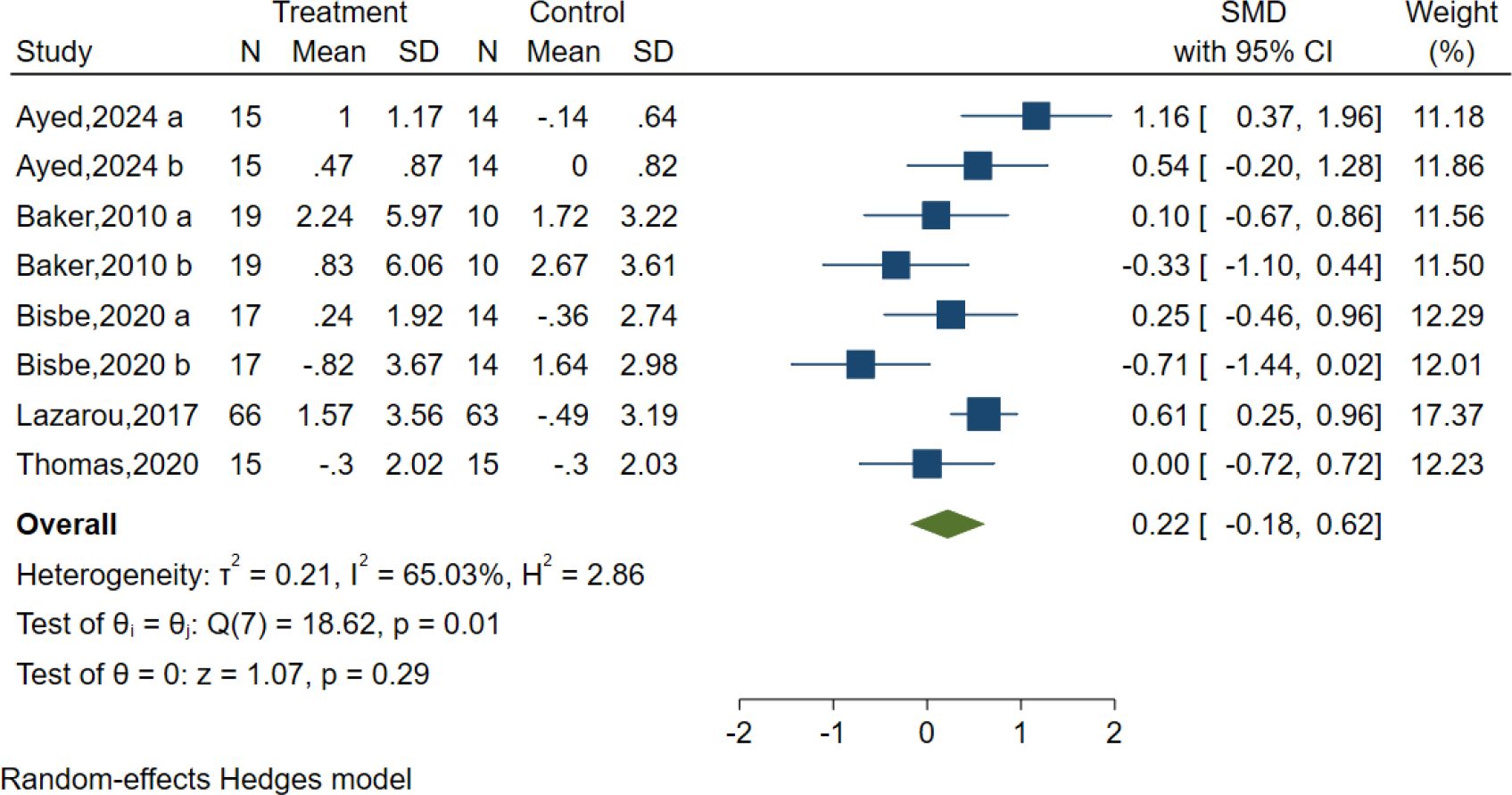

Language

Five studies evaluated the effects of AE on language using different classic and sensitive tests, including the Verbal Fluency Test (VFT), Verbal Fluency F-A-S test(FAS), and Boston Naming Test (BNT). However, the results indicated no significant effect of AE in the Language test [SMD = 0.22, 95% CI (−0.18, 0.62), p = 0.29; I2 = 65.03%, Q = 18.62, p = 0.01] (Figure 8).

We also performed subgroup analyses concerning the overall length of the intervention, duration, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the type of control group. Our findings revealed that the intensity and type of control had a significant positive impact on language. Specifically, moderate-intensity [SMD = 0.84, 95% CI (0.23, 1.45)], and the control type was reading [SMD = 0.84, 95% CI (0.23, 1.45)] showed optimal efficacy. However, the results are not recommended for adoption because of the limited number of studies included, which may compromise their reliability and generalizability (Supplementary Figures S7A–F).

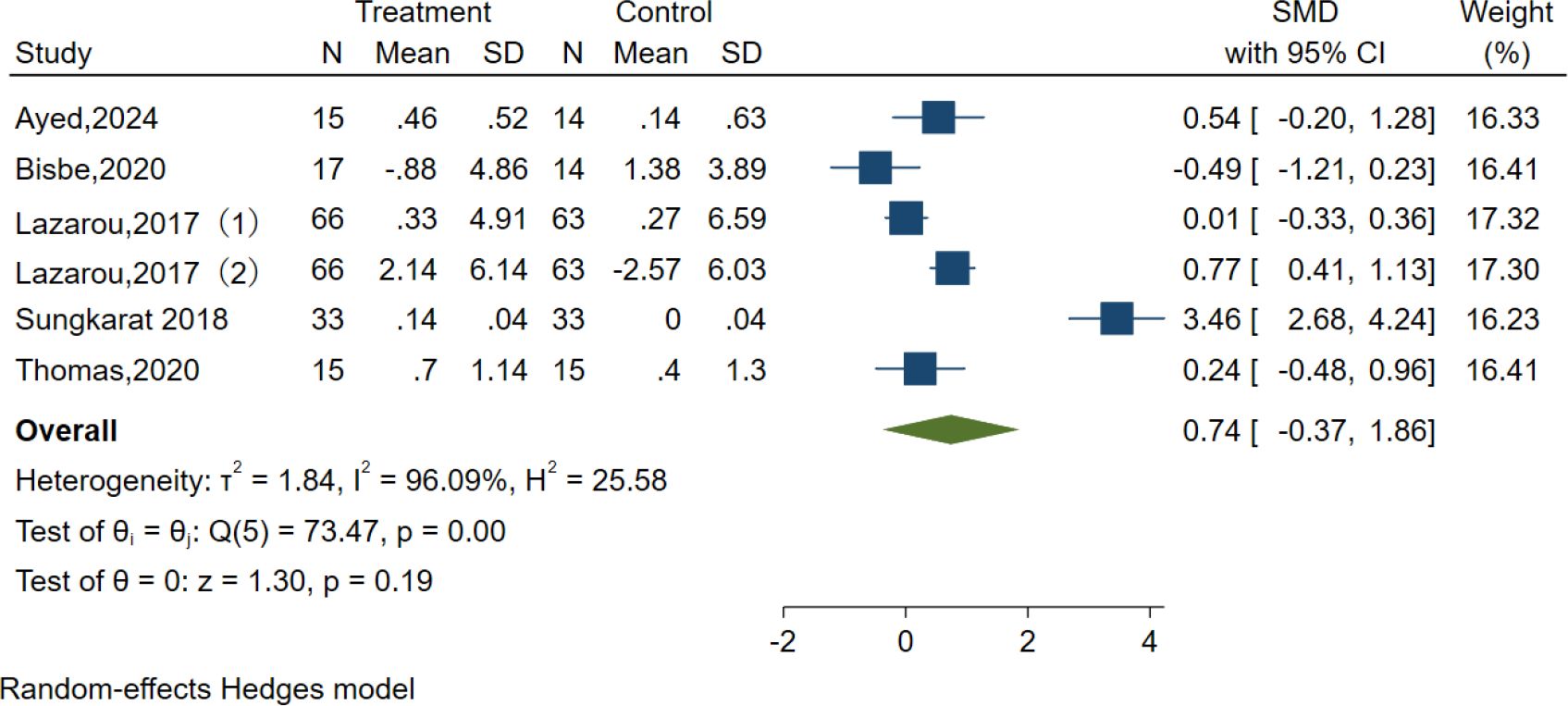

Visuospatial function

Five studies examined the effects of AE on visuospatial function using the clock test, Judgment of Line Orientation (JLO), and Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCFT). However, the results indicated no significant effect of AE in the Visuospatial function test [SMD = 0.74, 95% CI (−0.37, 1.86), p = 0.19; I2 = 96.09%, Q = 73.47, p < 0.01] (Figure 9).

We also performed subgroup analyses concerning the overall length of the intervention, duration, frequency, intensity, and type of intervention, as well as the type of control group. Our findings revealed that the intensity and type of control had a significant positive impact on language. Specifically, the duration was ≥30–≤50 min [SMD = 3.46, 95% CI (2.70, 4.22)], the intervention type was Tai Chi [SMD = 3.46, 95% CI (2.70, 4.22)], and the control type was usual care [SMD = 3.46, 95% CI (2.70, 4.22)], which showed optimal efficacy. However, the results are not recommended for adoption due to the limited number of studies included, which may compromise their reliability and generalizability (Supplementary Figures S8A–F).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses for both global cognition and specific cognitive domains. In each iteration, we removed one study at a time and assessed its impact on the overall effect size. Neither global cognition nor specific cognitive domains exhibited significant variations in effect size compared to the overall average, thereby validating the robustness of our research findings (Supplementary Figure S9).

Discussion

We conducted a meta-analysis of global cognition and specific cognitive domains in older patients with MCI. Our analysis demonstrates that AE intervention has remarkable potential for enhancing cognitive function and significantly mitigating the conversion from MCI to dementia. Among elderly MCI patients, it elicits substantial improvement in global cognition, with domain-specific efficacy variations ranging from mild to moderate in the present study. The effect sizes of memory and attention were 0.34 and 0.15, respectively. There was no significant improvement in executive function, processing speed, language and visuospatial function. The meta-analysis did not detect significant enhancements in visual-spatial function, language, or processing speed following AE. This may be attributable to the limited sample size, as AE primarily engages large muscle groups and does not directly target the fine motor skills or hand-eye coordination mechanisms underlying the assessed cognitive domains.

In addition, we performed a dose-response meta-analysis to examine the impact of intervention frequency, duration, intensity, and cumulative duration on overall cognitive function and specific cognitive domains using subgroup analysis. Regarding intervention frequency, our results revealed that a regimen of 3–5 sessions per week elicited a large effect size, significantly enhancing both global cognition (ES = 1.08) and memory (ES = 0.70) in older adults with MCI. Sanders et al (86). engaging in AE at least four times a week elicited beneficial outcomes. Jia et al (87). demonstrated that working out three or more times weekly had a positive impact on enhancing cognitive function. These findings are largely consistent with our research, which involved older adults with dementia and included activities beyond aerobic exercise. Regarding intervention duration, our findings revealed that variations in intervention duration exhibited the most significant impact on overall cognition and memory in elderly individuals with MCI, with effect sizes of 1.31 and 0.84, respectively. Notably, for elderly MCI patients, executive function improvements achieved the largest effect size (1.37) when exercise sessions were tailored to a duration of 30–50 min. This aligns with the observations of Ahn et al (88), who similarly reported optimal cognitive benefits for elderly with MCI following 30–50 min of AE. However, contrasting results emerged from Sanders et al.’s study (86), which indicated peak efficacy at 30 min of exercise, with durations exceeding 45 min showing no significant effects. It is important to note that their study included patients with dementia and diverse aerobic modalities, suggesting that prolonged exercise may induce central fatigue, a phenomenon potentially linked to diminished cognitive outcomes. Supporting this, existing research has demonstrated that exercise exceeding 50 min can lead to reduced cerebral blood flow, thereby compromising neurological function (89). Uncertainty persists regarding the role of specific time intervals in triggering fatigue in humans. In terms of intervention intensity, the results of this study demonstrated that low-intensity AE exerted the most significant impact on the overall cognitive function of elderly patients with MCI (ES = 1.20), while fluctuations in intensity during exercise duration exhibited the greatest influence on memory performance (ES = 0.23). Furthermore, this study highlights that despite intervention intensity being a source of heterogeneity in attention outcomes, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise has a minimal effect on attentional abilities in elderly individuals with MCI(ES=-0.05). Conversely, the existing literature suggests that moderate-intensity AE may confer optimal overall cognitive benefits in the elderly (90). This observation could be attributed to the physiological decline in older adults, which limits their capacity to sustain higher-intensity workouts. Consistent with this, prior meta-analyses have indicated that chronic exercise with varied intensity loads differentially affects working memory, while other studies have elucidated that the beneficial effects of physical activity vary contingent upon exercise modality (91, 92). Regarding the length of intervention, this study revealed that interventions lasting ≤12 weeks yielded an overall cognitive function effect size of 0.93 and a memory effect size of 0.27. Notwithstanding, prior literature has suggested that 3–6 month interventions may elicit optimal effects on global cognition and diverse cognitive domains in elderly populations (90). However, the current study exclusively focused on healthy older adults and alternative aerobic exercise modalities only. Conversely, the ACSM recommends that older individuals should sustain exercise volumes for 16 or 32 weeks or longer to preserve and potentiate exercise benefits. Notably, the present meta-analysis demonstrated statistical significance exclusively for interventions ≤12 weeks in duration. Based on these findings, this study advocates a weekly frequency of 3–5 intervention sessions for older adult patients with MCI. Furthermore, the duration and intensity of individual sessions, along with the overall intervention timeline, should be progressively titrated to optimise efficacy.

Extensive research has demonstrated that AE significantly enhances cognitive ability through various mechanisms. Silva et al. (93) revealed that AE effectively promotes neural plasticity, boosts cerebral blood flow, and strengthens synaptic connectivity, thereby positively influencing cognitive function. From an evolutionary neuroscience perspective, Raichlen and Alexander (94) postulated that AE enhances brain adaptability, facilitating the maintenance of executive function and memory retention while improving cognitive resilience during aging. At the molecular level, AE modulates dopamine, a neurotransmitter pivotal in motivation and cognitive processing, the regulation of which by exercise may underpin its cognitive benefits. Stillman et al (95). Further, aerobic exercise delays cognitive decline through three interconnected mechanisms: at the cellular level, exercise promotes the secretion of neurotrophic factors (BDNF, NGF, IGF-1), which facilitate neuronal growth, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation (LTP)—fundamental processes underpinning learning and memory (96, 97); at the neurostructural level, aerobic exercise induces structural remodelling, characterised by expanded gray and white matter volumes in the hippocampus and increased cortical thickness, alterations that are robustly associated with advanced cognitive functions. Psychologically, regular exercise alleviates stress, depression, and anxiety, enhancing emotional well-being and fostering cognitive resilience.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the use of multiple assessment tools to measure the same cognitive domain for comparison with AE interventions complicates the interpretation of the meta-analysis results. Second, the lack of standardized intervention protocols is a significant limitation. The “AE” interventions in the literature vary widely in modality (e.g., brisk walking, cycling), frequency, session duration, and intensity, lacking a unified, validated implementation framework. Third, considerable clinical heterogeneity across study samples must be acknowledged. Participants differed significantly in comorbidities, medication use, baseline physical and psychological status, sex, and education. Fourth, intervention durations were generally brief (predominantly 8–24 weeks), with a notable absence of long-term follow-up assessments. This precludes an evaluation of the long-term maintenance of cognitive benefits or the potential of AE to delay progression to dementia; future high-quality RCTs should therefore incorporate extended follow-up periods (e.g., 6–12 months post-intervention) to robustly validate the sustained benefits of AE.

The main advantage of this meta-analysis is the inclusion of a relatively large number of studies that adhere to strict and robust methodological standards to evaluate the efficacy of AE in enhancing cognitive function in elderly patients with MCI. The results show that AE can effectively improve the global cognition and memory of elderly people with MCI, and this result may provide empirical data for clinicians. However, methodological limitations and a limited number of studies have hindered the ability to determine the potential advantages of AE interventions for specific cognitive domains and different intervention methods. Furthermore, our review suggests future research should prioritize the following directions: First, researchers should develop a core, standardized AE intervention protocol for individuals with MCI. This requires establishing an evidence-based consensus on modality, intensity, frequency, and duration, supported by objective dose monitoring (e.g., using wearable devices). Second, multi-center collaborations should be established to employ a harmonized battery of validated cognitive assessments. This will enable robust longitudinal tracking of specific domains, particularly memory and executive function. Third, future study designs must systematically document comprehensive baseline participant characteristics (including MCI subtype, comorbidities, medication history, and genetic risk profiles) and incorporate post-intervention follow-up of at least 6–12 months. This is essential to clarify the long-term maintenance of cognitive benefits and the potential of AE to delay dementia progression. Ultimately, through the execution of high-quality, large-sample RCTs with extended follow-up, combined with advanced data analysis (e.g., exploring moderators and individual responses), we can work towards developing a targeted, scalable, and evidence-based intervention framework. This will provide precise, personalized guidance for clinical management.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis explored the impact of AE on global cognitive function and specific cognitive domains in patients with MCI. The findings unequivocally demonstrate that AE significantly enhances global cognition and memory in elderly individuals with MCI. Based on diverse intervention modalities, a frequency of 3–5 sessions per week is recommended. However, the optimal duration, intensity, and total duration of each intervention should be individualised and progressively adapted to each participant’s capacity. This study provides robust evidence supporting a dose-response association between AE and cognitive improvement in MCI, thereby offering practical implications for optimising future intervention strategies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

QZ: Writing – original draft. ZCH: Methodology, Writing – original draft. TW: Software, Writing – original draft. YJ: Writing – original draft, Software. HZ: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. GM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We really appreciate the efforts of all the researchers whose articles were included in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1741998/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Chojnacki C, Gasiorowska A, Poplawski T, Konrad P, Chojnacki M, Fila M, et al. Beneficial effect of increased tryptophan intake on its metabolism and mental state of the elderly. Nutrients. (2023) 15(4):847. doi: 10.3390/nu15040847

2. Shen J, Feng B, Fan L, Jiao Y, Li Y, Liu H, et al. Triglyceride glucose index predicts all-cause mortality in oldest-old patients with acute coronary syndrome and diabetes mellitus. BMC geriatrics. (2023) 23:78. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03788-3

3. Yong L, Liu L, Ding T, Yang G, Su H, Wang J, et al. Evidence of effect of aerobic exercise on cognitive intervention in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:713671. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713671

4. McGrattan AM, Pakpahan E, Siervo M, Mohan D, Reidpath DD, Prina M, et al. Risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s dementia (New York N Y). (2022) 8:e12267. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12267

5. Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TSD, Ganguli M, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment [RETIRED]: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. (2018) 90:126–35. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826

6. Beishon LC, Batterham AP, Quinn TJ, Nelson CP, Panerai RB, Robinson T, et al. Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III) and mini-ACE for the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database systematic Rev. (2019) 12:CD013282. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013282.pub2

7. Jia J, Wei C, Chen S, Li F, Tang Y, Qin W, et al. The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimer’s dementia. (2018) 14:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.12.006

8. Aggarwal NT, Tripathi M, Dodge HH, Alladi S, and Anstey KJ. Trends in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in the asian-pacific region. Int J Alzheimers Dis. (2012) 2012:171327. doi: 10.1155/2012/171327

9. Jia L, Du Y, Chu L, Zhang Z, Li F, Lyu D, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e661–e71. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30185-7

10. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, Fratiglioni L, Helmer C, Hendrie HC, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. (2017) 13:327–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.63

11. Feldman HH, Ferris S, Winblad B, Sfikas N, Mancione L, He Y, et al. Effect of rivastigmine on delay to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease from mild cognitive impairment: the InDDEx study. Lancet Neurology. (2007) 6:501–12. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70109-6

12. Langa KM and Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. Jama. (2014) 312:2551–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13806

13. Gavelin HM, Dong C, Minkov R, Bahar-Fuchs A, Ellis KA, Lautenschlager NT, et al. Combined physical and cognitive training for older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. (2021) 66:101232. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101232

14. Meng Q, Yin H, Wang S, Shang B, Meng X, Yan M, et al. The effect of combined cognitive intervention and physical exercise on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2022) 34:261–76. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01877-0

15. Bhatti GK, Reddy AP, Reddy PH, and Bhatti JS. Lifestyle modifications and nutritional interventions in aging-associated cognitive decline and alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. (2020) 11:369. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00369

16. Intzandt B, Vrinceanu T, Huck J, Vincent T, Montero-Odasso M, Gauthier CJ, et al. Comparing the effect of cognitive vs. exercise training on brain MRI outcomes in healthy older adults: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2021) 128:511–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.07.003

17. Heijnen S, Hommel B, Kibele A, and Colzato LS. Neuromodulation of aerobic exercise-A review. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:1890. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01890

18. Song D and Yu DSF. Effects of a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme on the cognitive function and quality of life of community-dwelling elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 93:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.019

19. Choi DH, Kwon KC, Hwang DJ, Koo JH, Um HS, Song HS, et al. Treadmill exercise alleviates brain iron dyshomeostasis accelerating neuronal amyloid-beta production, neuronal cell death, and cognitive impairment in transgenic mice model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. (2021) 58:3208–23. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02335-8

20. Lu X, Moeini M, Li B, de Montgolfier O, Lu Y, Belanger S, et al. Voluntary exercise increases brain tissue oxygenation and spatially homogenizes oxygen delivery in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol aging. (2020) 88:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.11.015

21. Ryan SM and Kelly AM. Exercise as a pro-cognitive, pro-neurogenic and anti-inflammatory intervention in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. (2016) 27:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.03.007

22. Garcia-Mesa Y, Colie S, Corpas R, Cristofol R, Comellas F, Nebreda AR, et al. Oxidative stress is a central target for physical exercise neuroprotection against pathological brain aging. journals gerontology Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2016) 71:40–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv005

23. Kim TW, Park SS, Park JY, and Park HS. Infusion of plasma from exercised mice ameliorates cognitive dysfunction by increasing hippocampal neuroplasticity and mitochondrial functions in 3xTg-AD mice. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(9):3291. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093291

24. Nakanishi K, Sakakima H, Norimatsu K, Otsuka S, Takada S, Tani A, et al. Effect of low-intensity motor balance and coordination exercise on cognitive functions, hippocampal Abeta deposition, neuronal loss, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. (2021) 337:113590. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113590

25. Jia M, Hu F, Hui Y, Peng J, Wang W, and Zhang J. Effects of exercise on older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. (2025) 104:980–94. doi: 10.1177/13872877251321176

26. Kong Q, Huang K, Li S, Li X, Han R, Yang H, et al. Effectiveness of various exercise on neuropsychiatric symptoms among older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2025) 112:102890. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2025.102890

27. Sun G, Ding X, Zheng Z, and Ma H. Effects of exercise interventions on cognitive function in patients with cognitive dysfunction: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Front Aging Neurosci. (2025) 17:1553868. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1553868

28. WHO. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-12-2020-who-launches-baseline-report-for-decade-of-healthy-ageing

29. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J sports Med. (2020) 54:1451–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

30. Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10:Ed000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142

31. Andrade C. Mean difference, standardized mean difference (SMD), and their use in meta-analysis: as simple as it gets. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 81(5):20f13681. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20f13681

32. Brydges CR. Effect size guidelines, sample size calculations, and statistical power in gerontology. Innovation Aging. (2019) 3:igz036. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz036

33. West SL, Gartlehner G, Mansfield AJ, Poole C, Tant E, Lenfestey N, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review Methods: Clinical Heterogeneity. Rockville (MD: AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care (2010).

34. Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002

35. Thompson SG and Higgins JP. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. (2002) 21:1559–73. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187

36. Patel MS. An introduction to meta-analysis. Health Policy. (1989) 11:79–85. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(89)90058-4

37. Tarumi T, Rossetti H, Thomas BP, Harris T, Tseng BY, Turner M, et al. Exercise training in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A one-year randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. (2019) 71:421–33. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181175

38. Zhu Y, Gao Y, Guo C, Qi M, Xiao M, Wu H, et al. Effect of 3-month aerobic dance on hippocampal volume and cognition in elderly people with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:771413. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.771413

39. Jeong MK, Park KW, Ryu JK, Kim GM, Jung HH, and Park H. Multi-component intervention program on habitual physical activity parameters and cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(12):6240. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126240

40. Lam LC, Chan WC, Leung T, Fung AW, and Leung EM. Would older adults with mild cognitive impairment adhere to and benefit from a structured lifestyle activity intervention to enhance cognition?: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0118173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118173

41. Li L, Liu M, Zeng H, and Pan L. Multi-component exercise training improves the physical and cognitive function of the elderly with mild cognitive impairment: a six-month randomized controlled trial. Ann palliative Med. (2021) 10:8919–29. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-1809

42. Li PWC, Yu DSF, Siu PM, Wong SCK, and Chan BS. Peer-supported exercise intervention for persons with mild cognitive impairment: a waitlist randomised controlled trial (the BRAin Vitality Enhancement trial). Age Ageing. (2022) 51(10):afac213. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac213

43. Liao YY, Tseng HY, Lin YJ, Wang CJ, and Hsu WC. Using virtual reality-based training to improve cognitive function, instrumental activities of daily living and neural efficiency in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:47–57. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.19.05899-4

44. Parial LL, Kor PPK, Sumile EF, and Leung AYM. Dual-task zumba gold for improving the cognition of people with mild cognitive impairment: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. (2023) 63:1248–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac081

45. Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Park H, Tsutsumimoto K, Verghese J, et al. Effects of combined physical and cognitive exercises on cognition and mobility in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med directors. (2018) 19(7):584–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.019

46. Suzuki T, Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Ito K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of multicomponent exercise in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. PloS One. (2013) 8:e61483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061483

47. Yang QH, Lyu X, Lin QR, Wang ZW, Tang L, Zhao Y, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention to slow mild cognitive impairment progression: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2022) 125:104110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104110

48. Köbe T, Witte AV, Schnelle A, Lesemann A, Fabian S, Tesky VA, et al. Combined omega-3 fatty acids, aerobic exercise and cognitive stimulation prevents decline in gray matter volume of the frontal, parietal and cingulate cortex in patients with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage. (2016) 131:226–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.050

49. Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, Foster JK, van Bockxmeer FM, Xiao J, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. Jama. (2008) 300:1027–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1027

50. Makino T, Umegaki H, Ando M, Cheng XW, Ishida K, Akima H, et al. Effects of aerobic, resistance, or combined exercise training among older adults with subjective memory complaints: A randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. (2021) 82:701–17. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210047

51. Amjad I, Toor H, Niazi IK, Afzal H, Jochumsen M, Shafique M, et al. Therapeutic effects of aerobic exercise on EEG parameters and higher cognitive functions in mild cognitive impairment patients. Int J Neurosci. (2019) 129:551–62. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2018.1551894

52. Chang J, Zhu W, Zhang J, Yong L, Yang M, Wang J, et al. The effect of Chinese square dance exercise on cognitive function in older women with mild cognitive impairment: the mediating effect of mood status and quality of life. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.711079

53. Law LLF, Mok VCT, and Yau MMK. Effects of functional tasks exercise on cognitive functions of older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. (2019) 11:98. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0548-2

54. Liu CL, Cheng FY, Wei MJ, and Liao YY. Effects of exergaming-based tai chi on cognitive function and dual-task gait performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized control trial. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:761053. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.761053

55. Nagamatsu LS, Chan A, Davis JC, Beattie BL, Graf P, and Voss MW. Physical activity improves verbal and spatial memory in older adults with probable mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. J Aging Res. (2013) 2013:861893. doi: 10.1155/2013/861893

56. Qi M, Zhu Y, Zhang L, Wu T, and Wang J. The effect of aerobic dance intervention on brain spontaneous activity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a resting-state functional MRI study. Exp Ther Med. (2019) 17:715–22. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.7006

57. Song D, Yu DSF, Li PWC, and Lei Y. The effectiveness of physical exercise on cognitive and psychological outcomes in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2018) 79:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.002

58. Tao J, Liu J, Chen X, Xia R, Li M, Huang M, et al. Mind-body exercise improves cognitive function and modulates the function and structure of the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex in patients with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage Clinical. (2019) 23:101834. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101834

59. Tsai CL, Pai MC, Ukropec J, and Ukropcová B. Distinctive effects of aerobic and resistance exercise modes on neurocognitive and biochemical changes in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. (2019) 16:316–32. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190228125429

60. Wang H, Pei Z, and Liu Y. Effects of square dance exercise on cognitive function in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment: the mediating role of balance ability and executive function. BMC geriatrics. (2024) 24:156. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04714-x

61. Wang L, Wu B, Tao H, Chai N, Zhao X, Zhen X, et al. Effects and mediating mechanisms of a structured limbs-exercise program on general cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2020) 110:103706. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103706

62. Wei XH and Ji LL. Effect of handball training on cognitive ability in elderly with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci letters. (2014) 566:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.02.035

63. Zhang Q, Zhu M, Huang L, Zhu M, Liu X, Zhou P, et al. A study on the effect of traditional Chinese exercise combined with rhythm training on the intervention of older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis other dementias. (2023) 38:15333175231190626. doi: 10.1177/15333175231190626

64. Zhu Y, Wu H, Qi M, Wang S, Zhang Q, Zhou L, et al. Effects of a specially designed aerobic dance routine on mild cognitive impairment. Clin Interventions aging. (2018) 13:1691–700. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S163067

65. Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch neurology. (2010) 67:71–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307

66. Thomas BP, Tarumi T, Sheng M, Tseng B, Womack KB, Cullum CM, et al. Brain perfusion change in patients with mild cognitive impairment after 12 months of aerobic exercise training. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. (2020) 75:617–31. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190977

67. Bisbe M, Fuente-Vidal A, Lopez E, Moreno M, Naya M, De Benetti C, et al. Comparative cognitive effects of choreographed exercise and multimodal physical therapy in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomized clinical trial. J Alzheimer’s disease. (2020) 73:769–83. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190552

68. Varela S, Ayán C, Cancela JM, and Martín V. Effects of two different intensities of aerobic exercise on elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized pilot study. Clin rehabilitation. (2012) 26:442–50. doi: 10.1177/0269215511425835

69. Bademli K, Lok N, Canbaz M, and Lok S. Effects of Physical Activity Program on cognitive function and sleep quality in elderly with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2019) 55:401–8. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12324

70. Uysal İ, Başar S, Aysel S, Kalafat D, and Büyüksünnetçi A. Aerobic exercise and dual-task training combination is the best combination for improving cognitive status, mobility and physical performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2023) 35:271–81. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02321-7

71. Krootnark K, Chaikeeree N, Saengsirisuwan V, and Boonsinsukh R. Effects of low-intensity home-based exercise on cognition in older persons with mild cognitive impairment: a direct comparison of aerobic versus resistance exercises using a randomized controlled trial design. Front Med. (2024) 11:1392429. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1392429

72. Sungkarat S, Boripuntakul S, Kumfu S, Lord SR, and Chattipakorn N. Tai chi improves cognition and plasma BDNF in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation Neural repair. (2018) 32:142–9. doi: 10.1177/1545968317753682

73. Choi W and Lee S. The effects of virtual kayak paddling exercise on postural balance, muscle performance, and cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys activity. (2019) 27(6):861–870. doi: 10.1123/jap2018-0020

74. Doi T, Verghese J, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, et al. Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Directors Assoc. (2017) 18:686–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.013

75. Combourieu Donnezan L, Perrot A, Belleville S, Bloch F, and Kemoun G. Effects of simultaneous aerobic and cognitive training on executive functions, cardiovascular fitness and functional abilities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Ment Health Phys activity. (2018) 15:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.06.001

76. ten Brinke LF, Bolandzadeh N, Nagamatsu LS, Hsu CL, Davis JC, Miran-Khan K, et al. Aerobic exercise increases hippocampal volume in older women with probable mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month randomised controlled trial. Br J sports Med. (2015) 49:248–54. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093184

77. Langoni C, Resende T, Barcellos AB, Cecchele B, Knob MS, Silva T, et al. Effect of exercise on cognition, conditioning, muscle endurance, and balance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J geriatric Phys Ther. (2019) 42(2):E15–22. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000191

78. Lazarou I, Parastatidis T, Tsolaki A, Gkioka M, Karakostas A, Douka S, et al. International ballroom dancing against neurodegeneration: a randomized controlled trial in Greek community-dwelling elders with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis other dementias. (2017) 32:489–99. doi: 10.1177/1533317517725813

79. Stuckenschneider T, Sanders ML, Devenney KE, Aaronson JA, Abeln V, Claassen JAHR, et al. NeuroExercise: the effect of a 12-month exercise intervention on cognition in mild cognitive impairment—A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci. (2021) 12:621947. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.621947

80. van Uffelen JG, Chinapaw MJ, van Mechelen W, and Hopman-Rock M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br J sports Med. (2008) 42:344–51. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044735

81. Karthikeyan T. Therapeutic effects of home-based exercise of geriatrics for the management of cognitive impairment. ES J Public Health. (2020) 1:1003.

82. Khattak HJ, Ahmad Z, Arshad H, and Anwar K. Effect of aerobic exercise on cognition in elderly persons with mild cognitive impairment. Rawal Med J. (2022) 47(3):696. doi: 10.5455/rmj.20210713072242

83. Kohanpour MA, Peeri M, and Azarbayjan MA. The effects of aerobic exercise with lavender essence use on cognitive state and serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in elderly with mild cognitive impairment. Br J Pharmacol. (2017) 6:80–4.

84. Ayed IB, Aouichaoui C, Ammar A, Naija S, Tabka O, Jahrami H, et al. Mid-term and long-lasting psycho-cognitive benefits of bidomain training intervention in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Invest health Psychol education. (2024) 14:284–98. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe14020019

85. Stuckenschneider T, Sanders ML, Devenney KE, Aaronson JA, Abeln V, Claassen J, et al. NeuroExercise: the effect of a 12-month exercise intervention on cognition in mild cognitive impairment-A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci. (2021) 12:621947. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.621947

86. Sanders LMJ, Hortobagyi T, la Bastide-van Gemert S, van der Zee EA, and van Heuvelen MJG. Dose-response relationship between exercise and cognitive function in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0210036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210036

87. Jia RX, Liang JH, Xu Y, and Wang YQ. Effects of physical activity and exercise on the cognitive function of patients with Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. BMC geriatrics. (2019) 19:181. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1175-2

88. Ahn J and Kim M. Effects of aerobic exercise on global cognitive function and sleep in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Nurs (New York NY). (2023) 51:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.02.008

89. Ogoh S, Tsukamoto H, Hirasawa A, Hasegawa H, Hirose N, and Hashimoto T. The effect of changes in cerebral blood flow on cognitive function during exercise. Physiol Rep. (2014) 2(9):e12163. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12163

90. Zhang M, Jia J, Yang Y, Zhang L, and Wang X. Effects of exercise interventions on cognitive functions in healthy populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2023) 92:102116. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2023.102116

91. Falck RS, Davis JC, Best JR, Crockett RA, and Liu-Ambrose T. Impact of exercise training on physical and cognitive function among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol aging. (2019) 79:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.007

92. Meijer A, Konigs M, van der Fels IMJ, Visscher C, Bosker RJ, Hartman E, et al. The effects of aerobic versus cognitively demanding exercise interventions on executive functioning in school-aged children: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. J sport Exercise Psychol. (2020) 43:1–13. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2020-0034

93. Boa Sorte Silva NC, Barha CK, Erickson KI, Kramer AF, and Liu-Ambrose T. Physical exercise, cognition, and brain health in aging. Trends Neurosci. (2024) 47:402–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2024.04.004

94. Raichlen DA and Alexander GE. Adaptive capacity: an evolutionary neuroscience model linking exercise, cognition, and brain health. Trends Neurosci. (2017) 40:408–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.05.001

95. Stillman CM, Esteban-Cornejo I, Brown B, Bender CM, and Erickson KI. Effects of exercise on brain and cognition across age groups and health states. Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:533–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.04.010

96. Jimenez-Roldan MJ, Sanudo Corrales B, and Carrasco Paez L. Effects of high-intensity interval training on executive functions and IGF-1 levels in sedentary young women: a randomized controlled trial. Front sports active living. (2025) 7:1597171. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2025.1597171

Keywords: aerobic exercise, mild cognitive impairment, old adults, cognitive function, meta-analysis

Citation: Zhao Q, Hong ZC, Wei TT, Jiang YT, Zeng H and Miao G (2026) Effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 16:1741998. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1741998

Received: 08 November 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Revised: 08 December 2025;

Published: 09 January 2026.

Edited by:

Takeshi Terao, Oita University, JapanCopyright © 2026 Zhao, Hong, Wei, Jiang, Zeng and Miao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Zeng, emVuZ2h1aUBjc3UuZWR1LmNu; Guiling Miao, MTc1MTY1NTMwNkBxcS5jb20=

Qian Zhao

Qian Zhao Zhao Chen Hong2

Zhao Chen Hong2 Hui Zeng

Hui Zeng Guiling Miao

Guiling Miao