Abstract

Introduction:

There are currently limited autopsy-based studies on sudden unexplained death in patients with schizophrenia (SDU-SCZ).

Methods:

We summarized the demographic data, autopsy characteristics, and postmortem antipsychotics result for a total of 152 SUD-SCZ decedents, encompassing three cases from our forensic center and 149 literature-reported autopsy cases.

Results:

The SUD individuals were found in adults at all ages, ranging from 19–86 years old, with a male-to-female ratio being 94: 58. A total of 106 patients (69.7%, 106/152) were documented to be overweight or obese. Autopsy findings were available in 77 of the 152 cases. The most frequent postmortem pathology was cardiac (46.8%, 36/77), of which unclassified cardiomegaly, focal myocardial fibrosis, and mild coronary atherosclerosis were the most common manifestations, documented in 11 (14.3%), 8 (10.4%), and 5 cases (6.5%), respectively. Data on postmortem antipsychotics were available in 74 of the 152 cases, of which 65 (87.8%, 65/74) were tested positive of any antipsychotic drug, all at therapeutic levels. Olanzapine and clozapine were the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic drugs, documented in 18 cases (24.3%, 18/74) and 16 cases (21.6%, 16/74), respectively. In these SUD-SCZ individuals, the exact cause of death remained unexplained after comprehensive autopsy examination and postmortem antipsychotics analysis.

Discussion:

Linking premorbid conditions (e.g. overweight or obese) to antipsychotics medication histories and postmortem myocardial pathologies would facilitate a more accurate determination and interpretation of the cause of death. Forensic investigation is useful for developing preventive strategies for this vulnerable population.

1 Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness that affects approximately 1% of the world’s population. Life expectancy in schizophrenia patients is estimated to be 10 to 25 years less than the general population and the incidence of sudden death is about three to four times higher (1, 2). Sudden cardiac death accounted for up to 50% of all deaths in schizophrenia, with the primary cause of death due to structural heart disorders, including coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and myocarditis. Despite those with identifiable abnormalities, some cases, about 8 to 10%, may have no definitive cause of death after systemic autopsy and toxicological screening. The causes of death remained unexplained, and were mostly presumed to be due to fatal arrhythmias (3, 4). In forensic pathology, sudden deaths that remain unexplained after comprehensive pathological and toxicological examinations were categorized as sudden unexplained death (SUD) (5). Those sudden deaths in schizophrenia patient without identifiable cardiac abnormality were commonly referred as sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia (SUD-SCZ) (6).

Most recent studies continue to highlight the elevated risk of sudden cardiac death and premature mortality in schizophrenia (7–9). Specifically, a large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis of 135 retrospective, nationwide, and targeted cohort studies assessing mortality risk among people with schizophrenia compared to the general population or other controls between 1957–2021 established a 152% increased risk in all-cause mortality, with a 100-200% risk for cardio-cerebrovascular or any natural causes of death (10). Despite the acknowledged increased of all-cause and cause-specific mortality rate observed in patients with schizophrenia as compared to the general population, fatal cardiac arrhythmias (absence of typical cardiac pathology) as the cause of sudden death among patients with schizophrenia were less frequently noted in the literature (11). Risk factors and the underlying mechanisms for SUD-SCZ remain unclear. The relevant autopsy-based studies on this topic are also scarce. In this study, we presented three cases of SUD-SCZ autopsied at Forensic Center of Gannan Medical University and further conducted a literature search in Pubmed online database for autopsy studies comprising SUD-SCZ cases. We sought to provide a comprehensive summary and novel insights into SUD-SCZ from a forensic perspective.

2 Case presentation

SUD-SCZ cases were retrospectively identified from autopsies that were performed at Forensic Center of Gannan Medical University between January 2020 and December 2024. Cases were identified to be included if the decedents were clearly diagnosed of schizophrenia in clinic before death, experienced a sudden, unexpected and natural death, and were absence of definite anatomic or toxicological cause of death after comprehensive postmortem examination. Postmortem examination consists of medical history review, scene investigation, autopsy, and antipsychotics analysis in blood. Macroscopic and microscopic evaluations of the hearts were performed by forensic pathologists with expertise in cardiovascular pathology. Cases with the cause of death being suicide, homicide, and drug overdose, or with significant heart diseases identified at autopsy, were excluded.

Three cases were identified. Medical information and forensic findings of the three decedents were extracted from archived records. Data were analyzed anonymously. Review of the records was approved by the Ethical Review Board at the School of Basic Medical Science, Gannan Medical University (Approval No.: 2021-127, 2023-051).

2.1 Case 1

A 44-year-old man was found dead in a psychiatric hospital. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia for over 10 years. He routinely received antipsychotic drug treatments, including clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine, but with a poor compliance. He was a heavy drinker and smoker. He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital due to aggressive psychotic behavior. During hospitalization, he took olanzapine 10mg/day orally for the first 4 day, followed by risperidone 4mg/day orally for the next 8 days, with diazepam 10mg/day. In the 14th day, he suddenly became unresponsive, stopped breathing, and was soon announced death in the hospital. At autopsy, the heart weighted 315g with no coronary atherosclerosis. Perivascular fibrosis and myocardial fibrosis in left ventricle were observed microscopically (Figures 1A, B). The liver presented with mild fatty changes microscopically. Other organs were unremarkable. Olanzapine and risperidone was positive in blood via postmortem antipsychotics screening.

Figure 1

Cardiac histo-pathological findings of perivascular fibrosis (A) and focal myocardial fibrosis in left ventricle (B) in case 1; lymphocytic infiltrate within the myocardium in the absence of significant myocyte injury (C) with detailed enlargement (D) in case 3. Magnification: (A, B) 100×, (C) 200×, (D) 400×. All with H&E staining.

2.2 Case 2

A 47-year-old woman collapsed with loss of consciousness, and died immediately in a psychiatric hospital. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia for two years. She was given several different antipsychotic drugs including quetiapine, olanzapine, but withdrawn when symptoms being improved. She was diagnosed with diabetes. After becoming irritability with odd behaviors for 3 days, she was referred to a psychiatry hospital. During hospitalization, risperidone 2mg/day was orally prescribed. The medication lasted for 2 days until her sudden death. At autopsy, the heart weighted 260g with no coronary atherosclerosis. The liver presented with mild fatty changes microscopically. Other organs were unremarkable. Risperidone was positive in blood via postmortem antipsychotics screening.

2.3 Case 3

A 48-year-old woman was found dead in an early morning at her residence. She was a chronic schizophrenia since age 36 and was treated several times. Antipsychotic drugs included risperidone, olanzapine. She was diagnosed with diabetes and hyperlipidemia, but whether she was on the treatment of diabetes and how was her blood glucose controlled remained unknown. Her last therapy lasted for a total of 14 days four months prior to her death. She took olanzapine 15mg/day orally for eight days, followed by amisulpride tablets 600mg/day orally for the next six days. Lorazepam 0.5mg/day was also prescribed. At autopsy, the heart weighted 220g. Small areas of focal inflammatory infiltration were observed in the myocardium, without significant myocyte injury microscopically (Figures 1C, D). No significant abnormality was found in other organs. Olanzapine and amisulpride were identified in blood via postmortem antipsychotics screening.

3 Literature review

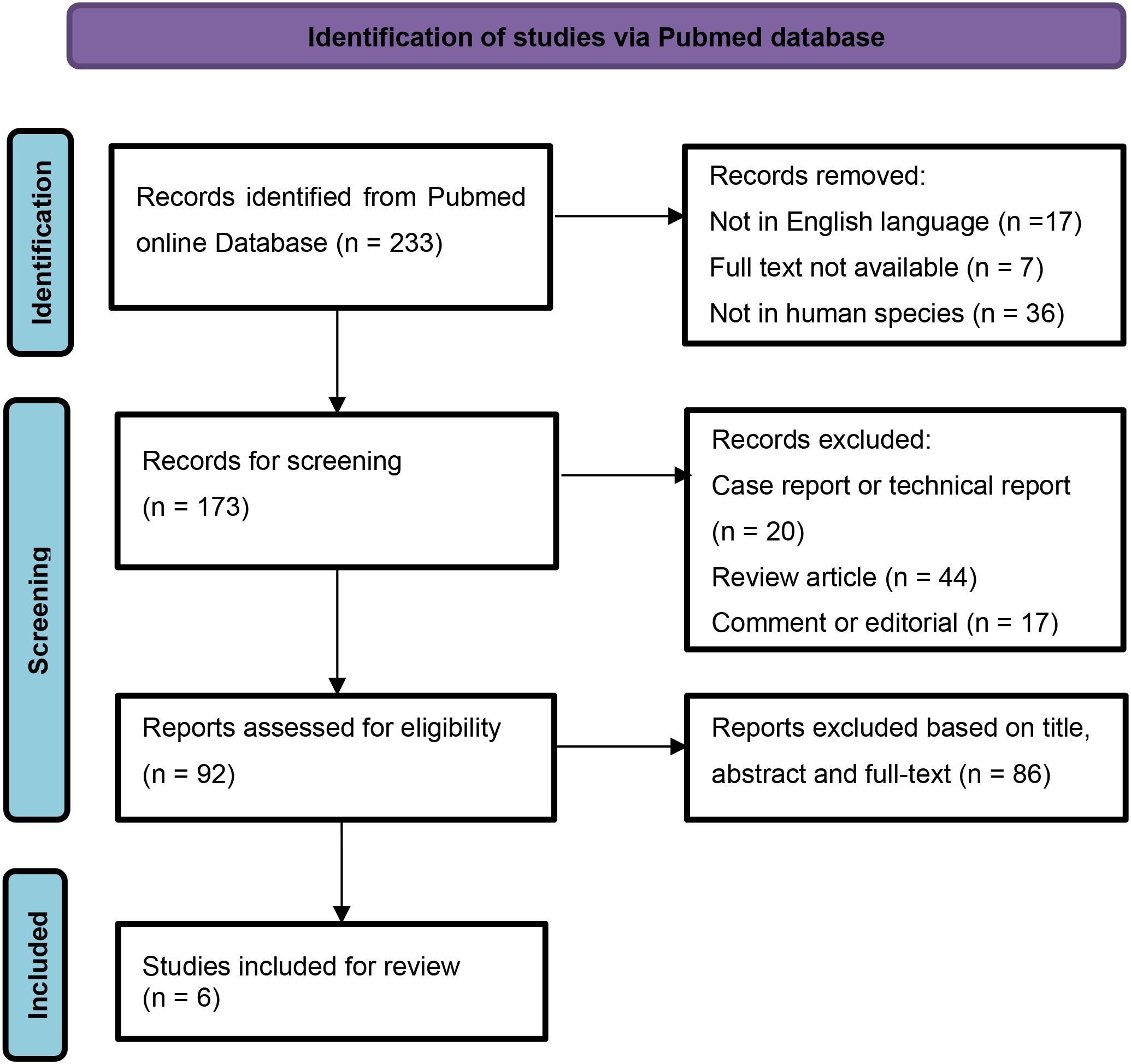

We conducted a literature search in Pubmed online database for forensic studies comprising SUD-SCZ cases, in accordance with the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (12). Two authors, Chen and Yan performed online search independently by utilizing the keywords “sudden death” and “schizophrenia” to detect all publications that related to autopsies in SUD-SCZ. The search was limited to articles published in English language. Restriction in publication date was set from January 2000 to July 2025. Articles were included in if they were forensic studies comprising SUD-SCZ cases, with full text available. Reviews, technical reports, case reports, books, or any published material without complete information were excluded. Titles, abstracts and full text were carefully evaluated to select eligible literature. In cases of discrepancy, two authors reached a consensus through discussion. A manual search of references was performed in the included articles to identify additional studies. PRISMA flowchart summarizing the article selection procession is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2

PRISMA flow chart for study selection.

Six forensic studies containing 149 SUD-SCZ cases were identified through the literature search (13–18). With the additional three from our own case series, a total of 152 cases were included in this study. Basic information and forensic characteristics of the 152 SUD decedents were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Category | Rosh A, et al (13) | Sweeting J, et al (14) | Ifteni P, et al. (15) | Sun D, et al. (16) | Wang S, et al. (17) | Vohra J, et al (18) | Present |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | 2003 | 2013 | 2014 | 2019 | 2023 | 2025 | |

| Country | USA | Australia | Romania | USA | China | Australia | China |

| Data range (y) | 1993-2001 | 2003-2012 | 1989-2013 | 2008-2012 | 2010-2022 | 2016-2021 | 2020-2024 |

| Autopsies in SCZ (n) | 216 | 683 | 51 | 391 | NA | NA | NA |

| SUD-SCZ Cases (n) | 6 | 72 | 6 | 11 | 18 | 36 | 3 |

| Age range (years) |

35-54 | 22-86 | 32-66 | 27-66 | 19-53 | 18-65 | 44-48 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | NA | 26.0 ± 7.1 | 26.0 ± 4.8 | 31.0 ± 7.2 | NA | (a) | NA |

| Male/Female | 4/2 | 41/31 | 4/2 | 7/4 | 11/7 | 26/10 | 1/2 |

| Autopsy findings (b) | NA | ||||||

| Cardiomegaly | 1 | 10 | |||||

| Ventricle dilation | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Mild atherosclerosis | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Focal myocardial fibrosis | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Focal myocardial inflammation | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Other cardiac pathology | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Pulmonary congestion | 2 | ||||||

| Focal bronchopneumonia | 3 | ||||||

| Hepatocyte steatosis | 1 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| Postmortem antipsychotics (c) | NA | NA | |||||

| Chlopromazine | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Haloperidol | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Benztropine | 2 | ||||||

| Thioridazine | 1 | ||||||

| Clozapine | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Olanzapine | 1 | 5 | 10 | 2 | |||

| Quetiapine | 4 | 1 | |||||

| Risperidone | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Ziprasidon | 1 |

Basic information and forensic characteristics of SUD-SCZ individuals (n=152).

SUD, sudden unexplained death; SUD-SCZ, sudden unexplained death in patients with schizophrenia; BMI: body mass index; NA: not available; Other cardiac pathology: including myocardial dystrophy, chronic pericarditis, and cardiac fatty infiltration; (a) 17/36 of the SUD subjects were obese with BMI>30; (b) autopsy findings were available in 77 cases; (c) postmortem antipsychotics data were available in 74 cases, of which 65 were tested positive, 29 cases were recorded as poly-pharmacy.

These unexplained deaths were found in adults at all ages, ranging from 19–86 years old, with a male-to-female ratio being 94: 58. The decedents were reported to be relatively young in two of the publications. Nine of the 11 patients were younger than 50 years of age with an average age of 38 years (16). The average age of the SUD group (39.0 ± 8.4 years) was reported to be significant younger compared to the sudden cardiac death group (49.5 ± 13.0) (17). In three of the included articles, the authors described that all the SUD decedents were overweight or even worse (BMI>25) (14–16). In another study, almost half (17/36) of the SUD subjects were obese with BMI>30, nearly a third (13/36) of the decedents had a premorbid diagnosis of either dyslipidemia (n=6), diabetes (n=4), or hypertension (n=3) (18). A total of 106 patients (69.7%, 106/152) were documented to be overweight or obese (BMI>25).

Autopsy findings were available in 77 of the included 152 cases. The most frequent postmortem pathology was cardiac (46.8%, 36/77), followed by hepatic (13%, 10/77) and pulmonary (6.5%, 5/77). Unclassified cardiomegaly, focal myocardial fibrosis, and mild coronary atherosclerosis were the most common cardiac pathologies, documented in 11 (14.3%), 8 (10.4%), and 5 cases (6.5%), respectively. Hepatic steatosis was documented in 10 cases. Pulmonary congestion or focal broncho-pneumonia were each documented in 5 decedents.

Data on postmortem antipsychotics were available in 74 individuals of the included 152 cases, of which 65 (87.8%, 65/74) were tested positive, all at therapeutic levels. Of the 65 cases, 29 (44.6%, 29/65) were recorded as poly-pharmacy. Olanzapine and clozapine were the most common antipsychotic drugs, recorded in 18 and 16 cases, respectively.

The causes of death were mostly presumed to be due to antipsychotics associated cardiac arrhythmia (13, 14, 16–18). However, Ifteni et al. (15) found no evidence to support the antipsychotic-induced arrhythmias as cause of death, as the utilization of antipsychotic drugs was similar in the explained and unexplained death groups.

4 Discussion

Patients with schizophrenia were at a high risk of sudden cardiac death, with the primary cause of death due to structural heart disorders, including coronary heart disease, myocarditis, and cardio-myopathy. In some of these patients, the exact cause of death remained unexplained after standardized autopsy examination procedures, and these cases were categorized as SUD-SCZ. SUD accounted for a small minority of excess deaths in people with schizophrenia with a reported incidence ranging from 2.8% (13) to 11.8% (16). A recent retrospective study from Australia indicated that the prevalence of SUD-SCZ was up to 29.2% among patients with schizophrenia (19). Our cases, with comprehensive postmortem examination, add to the very few autopsy studies in this population published in the literature. Further research is required to explore the increased observation of SUD in people with schizophrenia.

According to our reported and literature-derived cases, the SUD individuals were found in adults at all ages, ranging from 19–86 years old, with the male-to-female ratio being 94: 58. Two out of the six studies reported that young individuals accounted for the majority of the decedents (16, 17), which raises the possibility that male sex or young age might be a risk factor for SUD-SCZ. However, a meta-analysis of 43 studies reporting on 2,700,825 people with schizophrenia demonstrated that both males and females with schizophrenia experience increased risks of all-cause and cause-specific mortality compared to the general population. There was no statistical significant difference in sex-dependent mortality risk except for males being at a significantly higher risk of death due to dementia (20). The differential influence of sex and age on SUD-SCZ merits further investigations.

Some risk factors have been proposed for SUD in patients with schizophrenia and other psychiatry disorders. An earlier study comprising 100 SUD patients relying on death certificates indicated that dyslipidemia (p=0.012) and co-morbid dyslipidemia and diabetes (p=0.008) were more common in the unexplained cases compared with the group of explained sudden deaths in psychiatric patients (21). In the present study, among the retrieved articles, three articles described that all the SUD decedents were overweight or even worse (BMI>25) (14–16), whereas another study noted that almost half (17/36) of the SUD subjects were obese with BMI>30, summarizing that nearly a third (13/36) of the decedents had a premorbid diagnosis of either dyslipidemia, diabetes, or hypertension (18). In our three cases, two had diabetes and one had dyslipidemia. Our data confirms the notion that dyslipidemia and diabetes were common in SUD patients with schizophrenia. These risk factors may at least to some extent, either alone or in combination, correlate with a more rapid illness worsening than in patients without mental illness (22). The rate of patient with severe mental illness not treated for established cardiovascular risk factors has been reported to be as 88% for dyslipidemia, 62% for hypertension, and 30% for diabetes (23, 24). It is hence strongly suggested that clinicians remain vigilant for the signs or symptoms of diabetes, or dyslipidemia to improve cardiovascular safely in this vulnerable population. A total of 106 patients (69.7%, 106/152) were documented to be overweight or obese (BMI>25) in our study, highlighting the importance of tailored metabolic interventions based on BMI stratification. It is noteworthy that a significant higher occurrence of psychiatric episodes was observed in the SUD group than in explainable deaths (p=0.018) and (OR = 4.025, P = 0.040) (17). Psychiatric episodes were considered as an independent risk factor for SUD in schizophrenia (17). Persistent psychotic episodes often demand an extra load on the heart, and were also associated with increased risks of short-term post-acute coronary syndrome, thereby increasing the possibility of sudden death in patient with schizophrenia (25). Risk factors for sudden death in schizophrenia are complex. Patients with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders are more likely to be overweight, smoke, and have diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or metabolic disorders than those without schizophrenia (26, 27) Moreover, long-term treatment with antipsychotic medication can increase the risk of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, even in young patients. This state of metabolic change may lead to an increased risk of sudden cardiac death and cardiovascular disease mortality among schizophrenia (28, 29). Aside from the aforementioned cardiovascular risk factors, other factors, such as drug influences, genetic background might also underlie predisposition to sudden death (30). Awareness of these risk factors and implementing proactive management might lead to effective interventions for prevention and treatment in schizophrenia patients.

At autopsy, although no clear causes of death were determined, some pathological changes were still observed in our reported and those literature-derived cases, with the cardiac alterations being particularly prominent (46.8%). Unclassified cardiomegaly, focal myocardial fibrosis, and mild coronary atherosclerosis were the most common cardiac pathologies, followed by focal myocardial inflammation, myocardial dystrophy, and cardiac fatty infiltration. These cardiac pathologies, were insufficient to meet diagnostic criteria for known pathologies and insufficient to conclude as causes for sudden death. Such alterations may be partly due to the effects of antipsychotic medications on the cardiac tissue, as chronic exposure to antipsychotics have been reported to impair cardiac structure and function, causing inflammatory lesions, cardiac fibrosis, and cardiomyopathy (31, 32). Taking the focal myocardial inflammation and focal myocardial fibrosis mentioned in our cases for example, clozapine induced myocarditis is by far the most frequently reported antipsychotic-related cardiac injury, with an estimate incidence of 0.7-1.2% (32, 33). Most of these cases occurred in the first 2 months after clozapine therapy. If acute myocarditis is not recognized at the early stage, it may progress to dilated cardiomyopathy, characterized by ventricular dilation and heart dysfunction. Many of the patients were entirely asymptomatic and further, did not undergo the expected investigations that one might expect prior to death (34, 35). In an autopsy report, six in 14 cases were reported to die suddenly from dilated cardiomyopathy, following chronic antipsychotic use (36). A recent study by Esposito et al. from Italy identified myocardial fibrosis and contraction band necrosis in young schizophrenia patients without pre-existing cardiac disease, died suddenly while on antipsychotic therapy at therapeutic doses, corroborating the findings from our cases (37). However, such cardiac findings have also been observed occasionally by forensic pathologists in otherwise healthy individuals, or in SUD among general population, and were categorized as non-diagnostic or autopsy findings with uncertainty of significance (38, 39). From a forensic point of view, exploration of the comparative autopsy findings on preponderance and severity in patients with antipsychotics exposure and those non-exposed population is important for cause-of-death determination. In addition, a pragmatic close clinical monitoring protocol including cardiac biomarkers aimed at timely detection of cardiac toxicity (cardiac injury), in the initial phase of antipsychotics treatment is strongly recommended.

The exact pathophysiological causes of SUD-SCD are not fully understood yet. It is very probable that arrhythmias potentially related with antipsychotics use may play a significant role (40, 41). Antipsychotic medications may increase the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias such as TdP, probably QT interval prolongation through blockade of potassium ion channels, which in worst case, can lead to sudden cardiac death. Specifically, poly-pharmacy and high-dose antipsychotics are widely considered to be an important and the clearest evidence for an elevated SCD risk related to drug-drug interactions in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (41–44). It is not surprisingly that the majority of the patients in present study were tested positive for antipsychotics, because these patients often receive antipsychotic treatments. However, due to the heterogeneity of antipsychotics medication histories, current available data do not allow to document any clear-cut differences in the risk of sudden death between first and second generation antipsychotics or between individual antipsychotic drugs. Moreover, the aforementioned data do not allow to establish a causal correlation between antipsychotics and fatal cardiac arrhythmia because the absence of clinical electrocardiographic (ECG) evidence. The causes of death were made by excluding other alternative causes of death in the literature and our case series. Linking ante-mortem ECG to antipsychotics medication histories and postmortem myocardial lesions would improve the precise diagnosis (45). In a recent study by LC-MS/MS analysis in antipsychotics treated mice, the authors found that the serum of olanzapine and clozapine were generally within therapeutic ranges, while the olanzapine and clozapine concentrations in the heart were significantly elevated since the day 14 and its average level increased by up to 3-fold and 22-fold on day 21 respectively, suggesting that antipsychotics accumulated in the heart and exclusively induced cardiac toxic effects. This may, on one hand, partially explains the contribution of antipsychotic drug use to the development of SUD, and on the other hand suggests that the antipsychotic drug doses in the heart, not only in blood, should be analyzed for interpretation of unexpected death (46). From a forensic perspective, quantifying drug levels within myocardium and comparing distribution across regions (sub-endocardium, conduction system) would help distinguish direct myocardial accumulation from peripheral redistribution and support mechanistic links to the sudden death (45, 47).

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size from our center is small, providing a lack of representativeness. Secondly, our literature search used only one database, with the included articles only in English language. Therefore, there may be a portion of literatures being missed. Lastly, neuro-pathological changes were not mentioned or not available in many cases of our study. So, our study did not summarize the neural pathology.

5 Conclusions

In all, we systemically analyzed the forensic findings including demographic data, autopsy characteristics, and postmortem antipsychotics results from both our forensic center and literature resources. In these SUD-SCZ individuals, the majority of the decedents were found to be overweight or obese; cardiac pathology was the most common finding at autopsy; olanzapine and clozapine were the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic drugs; the exact cause of death remained unexplained after comprehensive autopsy examination and postmortem antipsychotic analysis. Linking premorbid conditions (e.g. overweight or obese) to antipsychotics medication histories and postmortem myocardial pathologies would facilitate a more accurate determination and interpretation of the cause of death. Forensic investigation is useful for developing preventive strategies for this vulnerable population.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethical Review Board at the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Gannan Medical University (approval No.: 2021-127 and 2023-051). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CY: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software. YF: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was financially funded by the Open project of the Key Laboratory of Forensic Pathology, Ministry of Public Security (No.: GAFYBL201903,202307), the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangxi Province (No.: 20161BBG70082), and the Research Project of Gannan Medical University (No.: XN201924).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

McCutcheon RA Reis Marques T Howes OD . Schizophrenia-an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:201–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3360

2

Hjorthoj C Sturup AE McGrath JJ Nordentoft M . Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2017) 4:295–301. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

3

Li KJ Greenstein AP Delisi LE . Sudden death in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2018) 31:169–75. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000403

4

Vohra J . Sudden cardiac death in schizophrenia: A review. Heart Lung Circ. (2020) 29:1427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.07.003

5

Basso C Aguilera B Banner J Cohle S d’Amati G de Gouveia RH et al . Guidelines for autopsy investigation of sudden cardiac death: 2017 update from the association for european cardiovascular pathology. Virchows Arch. (2017) 471:691–705. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2221-0

6

Zhang M Wang S Tang X Ye X Chen Y Liu Z et al . Use of potassium ion channel and spliceosome proteins as diagnostic biomarkers for sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia. Forensic Sci Int. (2022) 340:111471. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2022.111471

7

Tang CH Ramcharran D Yang CW Chang CC Chuang PY Qiu H et al . A nationwide study of the risk of all-cause, sudden death, and cardiovascular mortality among antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Schizophr Res. (2021) 237:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.08.015

8

Mujkanovic J Warming PE Kessing LV Kober LV Winkel BG Lynge TH et al . Nationwide burden of sudden cardiac death among patients with a psychiatric disorder. Heart. (2024) 110:1365–71. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2024-324092

9

Popa AV Ifteni PI Tabian D Petric PS Teodorescu A . What is behind the 17-year life expectancy gap between individuals with schizophrenia and the general population? Schizophr (Heidelb). (2025) 11:117. doi: 10.1038/s41537-025-00667-1

10

Correll CU Solmi M Croatto G Schneider LK Rohani-Montez SC Fairley L et al . Mortality in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. (2022) 21:248–71. doi: 10.1002/wps.20994

11

Ishida T Sugiyama K Tanabe T Hamabe Y Mimura M Suzuki T et al . Lower proportion of fatal arrhythmia in sudden cardiac arrest among patients with severe mental illness than nonpsychiatric patients. Psychosomatics. (2020) 61:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2019.08.005

12

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

13

Rosh A Sampson BA Hirsch CS . Schizophrenia as a cause of death. J Forensic Sci. (2003) 48:164–7. doi: 10.1520/JFS2002001

14

Sweeting J Duflou J Semsarian C . Postmortem analysis of cardiovascular deaths in schizophrenia: A 10-year review. Schizophr Res. (2013) 150:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.08.029

15

Ifteni P Correll CU Burtea V Kane JM Manu P . Sudden unexpected death in schizophrenia: autopsy findings in psychiatric inpatients. Schizophr Res. (2014) 155:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.03.011

16

Sun D Li L Zhang X Blanchard TG Fowler DR Li L . Causes of sudden unexpected death in schizophrenia patients: A forensic autopsy population study. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. (2019) 40:312–7. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000512

17

Wang S He M Andersen J Lin Y Zhang M Liu Z et al . Sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia patients: an autopsy-based comparative study from China. Asian J Psychiatr. (2023) 79:103314. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103314

18

Vohra J Thompson T Morgan N Parsons S Zentner D Thompson B et al . A study of sudden cardiac death in schizophrenia. Heart Lung Circ. (2025) 34:613–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2024.11.011

19

Paratz ED van Heusden A Zentner D Morgan N Smith K Thompson T et al . Sudden cardiac death in people with schizophrenia: higher risk, poorer resuscitation profiles, and differing pathologies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2023) 9:1310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2023.01.026

20

Solmi M Croatto G Fabiano N Wong S Gupta A Fornaro M et al . Sex-stratified mortality estimates in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of 2,700,825 people with schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2025) 91:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2024.11.001

21

Manu P Kane JM Correll CU . Sudden deaths in psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychiatry. (2011) 72:936–41. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06244gry

22

Henderson DC Vincenzi B Andrea NV Ulloa M Copeland PM . Pathophysiological mechanisms of increased cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Lancet Psychiatry. (2015) 2:452–64. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00115-7

23

Nasrallah HA Meyer JM Goff DC McEvoy JP Davis SM Stroup TS et al . Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the catie schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. (2006) 86:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.026

24

Lack D Holt RI Baldwin DS . Poor monitoring of physical health in patients referred to a mood disorders service. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2015) 5:22–5. doi: 10.1177/2045125314560734

25

Chan SKW Chan HYV Liao Y Suen YN Hui CLM Chang WC et al . Longitudinal relapse pattern of patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and its predictors and outcomes: A 10-year follow-up study. Asian J Psychiatr. (2022) 71:103087. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103087

26

Polcwiartek C O’Gallagher K Friedman DJ Correll CU Solmi M Jensen SE et al . Severe mental illness: cardiovascular risk assessment and management. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45:987–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae054

27

Vaccarino V Prescott E Shah AJ Bremner JD Raggi P Dobiliene O et al . Mental health disorders and their impact on cardiovascular health disparities. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2025) 56:101373. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101373

28

Ijaz S Bolea B Davies S Savovic J Richards A Sullivan S et al . Antipsychotic polypharmacy and metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: A review of systematic reviews. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:275. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1848-y

29

Challa F Getahun T Sileshi M Geto Z Kelkile TS Gurmessa S et al . Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:620. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03631-2

30

Treur JL Thijssen AB Smit DJA Tadros R Veeneman RR Denys D et al . Associations of schizophrenia with arrhythmic disorders and electrocardiogram traits: genetic exploration of population samples. Br J Psychiatry. (2025) 226:153–61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2024.165

31

Li XQ Tang XR Li LL . Antipsychotics cardiotoxicity: what’s known and what’s next. World J Psychiatry. (2021) 11:736–53. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i10.736

32

Kelly DL Wehring HJ Linthicum J Feldman S McMahon RP Love RC et al . Cardiac-related findings at autopsy in people with severe mental illness treated with clozapine or risperidone. Schizophr Res. (2009) 107:134–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.020

33

Wooltorton E . Antipsychotic clozapine (Clozaril): myocarditis and cardiovascular toxicity. CMAJ. (2002) 166:1185–6.

34

Kilian JG Kerr K Lawrence C Celermajer DS . Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy associated with clozapine. Lancet. (1999) 354:1841–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)10385-4

35

Patel RK Moore AM Piper S Sweeney M Whiskey E Cole G et al . Clozapine and cardiotoxicity - a guide for psychiatrists written by cardiologists. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 282:112491. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112491

36

Frassati D Tabib A Lachaux B Giloux N Dalery J Vittori F et al . Hidden cardiac lesions and psychotropic drugs as a possible cause of sudden death in psychiatric patients: A report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. (2004) 49:100–5. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900204

37

Esposito M Zuccarello P Sessa F Capasso E Giorgetti A Pesaresi M et al . Sudden cardiac death in young adults and the role of antipsychotic drugs: A multicenter autopsy study. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. (2025). doi: 10.1007/s12024-025-01096-3

38

Raju H Parsons S Thompson TN Morgan N Zentner D Trainer AH et al . Insights into sudden cardiac death: exploring the potential relevance of non-diagnostic autopsy findings. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:831–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy654

39

Papadakis M Raju H Behr ER De Noronha SV Spath N Kouloubinis A et al . Sudden cardiac death with autopsy findings of uncertain significance: potential for erroneous interpretation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2013) 6:588–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000111

40

Howell S Yarovova E Khwanda A Rosen SD . Cardiovascular effects of psychotic illnesses and antipsychotic therapy. Heart. (2019) 105:1852–9. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312107

41

Ray WA Chung CP Murray KT Hall K Stein CM . Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. (2009) 360:225–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806994

42

Erkan O Dai AS Ozturk N Ozdemir S . Second-generation antipsychotics - cardiac ion channel modulation and qt interval disturbances: A review. Biomol BioMed. (2025). doi: 10.17305/bb.2025.13405

43

Ruiz Diaz JC Frenkel D Aronow WS . The relationship between atypical antipsychotics drugs, qt interval prolongation, and torsades de pointes: implications for clinical use. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2020) 19:559–64. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1745184

44

Melo L Pillai A Kompella R Patail H Aronow WS . An updated safety review of the relationship between atypical antipsychotic drugs, the qtc interval and torsades de pointe as: implications for clinical use. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 23:1127–34. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2024.2392002

45

Dedeepya SD Goel V Desai NN . Comment on “Sudden cardiac death in young adults and the role of antipsychotic drugs: A multicenter autopsy study. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. (2025). doi: 10.1007/s12024-025-01136-y

46

Li L Gao P Tang X Liu Z Cao M Luo R et al . Cb1r-stabilized nlrp3 inflammasome drives antipsychotics cardiotoxicity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2022) 7:190. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01018-7

47

Castellino S Groseclose MR Wagner D . Maldi imaging mass spectrometry: bridging biology and chemistry in drug development. Bioanalysis. (2011) 3:2427–41. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.232

Summary

Keywords

antipsychotics, autopsy, forensic pathology, schizophrenia, sudden unexplained death

Citation

Chen Y and Yan F (2026) Forensic postmortem findings for sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia: case series and literature review. Front. Psychiatry 17:1578123. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2026.1578123

Received

17 February 2025

Revised

05 January 2026

Accepted

07 January 2026

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Stefano Ferracuti, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Reviewed by

Yuko Higuchi, University of Toyama Graduate School of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Japan

Donato Morena, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chen and Yan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fengping Yan, tomjiangxi@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.