- 1Hangzhou Wuyunshan Hospital (Hangzhou Institute for Health Promotion), Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 2Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 3Affiliated Mental Health Center & Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 4National Center for Mental Health, Beijing, China

Objective: This study examined the current state of decent work among psychiatrists and explored factors associated with their perceptions of decent work.

Methods: This cross-sectional study used convenience sampling to recruit psychiatrists from eight hospitals in China. Data were collected online using the Self-Control Scale (SCS), the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS), and the Decent Work Perception Scale (DWPS). A total of 517 valid responses were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with perceptions of decent work.

Results: Career adaptability was positively associated with decent work (r = 0.534, p < 0.01), and self-control was also positively associated with decent work (r = 0.396, p < 0.01). Monthly income and professional title were significantly associated with decent work. Significant differences were found between psychiatrists earning less than 8,000 RMB and those earning 8,000–12,000 RMB (β = 0.178, p = 0.001), 12,000–20,000 RMB (β = 0.199, p = 0.001), and more than 20,000 RMB (β = 0.143, p = 0.005). A significant difference was also observed between resident physician and attending physician (β = -0.141, p = 0.010).

Conclusions: Income, professional title, self-control, and career adaptability were associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. These findings may inform discussions on working conditions and contribute to efforts to support the sustainability of mental health services.

1 Introduction

As the understanding of mental illness has shifted from interpretations rooted in moral deficiency or demonic influence to a medical condition amenable to scientific treatment (1), the role of psychiatrists has transitioned from marginalization to becoming a crucial component of societal stability. Despite this progress, psychiatric healthcare professionals remain disproportionately affected by workplace violence (2). Evidence on mental health among clinicians further shows that psychiatrists experience higher rates of depression than many other medical specialists (3). In China, nearly one-fifth of psychiatrists report an intention to leave the profession (4). In addition, they face a constellation of challenges, including burnout (5) and persistent professional stigma (6–8), all of which exert sustained negative effects on their professional lives. Therefore, exploring the current state of decent work among psychiatrists and the factors associated with it not only contributes to understanding their position in modern society but also offers a theoretical basis for supporting their rights.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) formally introduced the concept of “decent work” in 1999, defining it as employment that ensures freedom, equity, security, and dignity for all workers (9). Although early research in healthcare settings has examined decent work among psychiatric nurses, considerably less attention has been given to psychiatrists, whose professional environment differs substantially from that of other medical groups. In China, psychiatrists face pronounced occupational stressors, including elevated rates of workplace violence and burnout (10, 11). Therefore, ensuring decent work for psychiatrists is therefore not only essential for respecting and protecting their individual rights but also a necessary component of the sustainable development of the mental health sector.

The importance of self-control for individual well-being and career success has received considerable scholarly attention. Self-control, defined as the capacity to inhibit impulses and act in accordance with social norms, has been linked to behavioral problems and antisocial tendencies when insufficient (12). In occupations that place high demands on self-control, such as the service sector, the inability to meet these demands can result in burnout and emotional exhaustion (13). Individuals with stronger self-control are also more likely to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors that benefit both their colleagues and the broader organization (14). Psychiatrists work in environments characterized by high levels of emotional pressure, complex clinician–patient interactions, and continuous advances in medical knowledge. These challenges often generate feelings of overload and diminished control (15, 16). Thus, strengthening self-control among psychiatrists may therefore help them regulate their emotions and behaviors more effectively, promoting better adaptation to the rapidly evolving healthcare environment.

Career adaptability refers to the psychological resources and self-regulatory capacities individuals draw upon when responding to current and anticipated career tasks, challenges, transitions, and major life events (17). It is regarded as a flexible psychological resource that enables individuals to navigate career-related changes and supports continuous professional development (18). Prior research has shown that career adaptability directly contributes to higher levels of work engagement among healthcare professionals and is associated with a stronger orientation toward happiness (19). It has also been linked to turnover intentions, suggesting that individuals with higher adaptability are less likely to consider leaving their jobs (20). Furthermore, a meta-analysis demonstrated that career adaptability is significantly related to a range of psychological and dispositional variables, including cognitive ability, self-esteem, core self-evaluation, proactive personality, future orientation, hope, and optimism (21). However, existing research on career adaptability has primarily focused on populations such as university students (22), employees in organizational settings (23), and nurses (24). Studies examining career adaptability among psychiatrists remain limited, highlighting a need for further investigation within this professional group.

The Psychology of Working Theory (PWT) offers a theoretical basis for examining how self-control and career adaptability relate to perceptions of decent work. PWT positions decent work at the center of its framework and explains how individuals obtain work experiences that meet basic survival needs, social connection needs, and self-determination needs. The theory proposes that economic constraints and marginalization influence work volition and career adaptability, and these constructs are associated with the attainment of decent work (25). From a functional perspective, self-control represents a foundational psychological capacity that enables the effective enactment of career adaptability (17). Within the PWT framework, career adaptability is conceptualized as a key mechanism through which individuals navigate structural constraints to achieve decent work. In occupations characterized by high emotional demands and uncertainty, individuals with higher levels of self-control are better able to sustain goal-directed occupational behavior and regulate emotional responses to role conflict and complex work requirements, thereby facilitating the development and mobilization of career adaptability (26, 27). In turn, individuals with greater career adaptability are more capable of managing occupational stressors, coordinating external constraints with personal career goals, and maintaining functional and sustainable work performance, which enhances their perceptions of work quality and decency (28). Accordingly, we propose that self-control indirectly influences perceptions of decent work through its support of career adaptability, with career adaptability serving as a mediating mechanism in this relationship.

In psychiatric clinical practice, perceptions of decent work are shaped by various structural factors such as workload, institutional regulations, and clinical risk, many of which are difficult for individuals to change in the short term. The PWT emphasizes the role of psychological processes and identifies career adaptability as a key mechanism through which individuals construct experiences of decent work under structural constraints (29). As a psychological resource, self-control does not directly alter external conditions but enables individuals to regulate attention, emotional responses, and behavior in stressful situations (30). This regulatory capacity serves as a foundation for adaptive career behaviors and is closely related to career adaptability (17, 31). Career adaptability reflects the extent to which individuals mobilize internal resources to respond to external constraints by demonstrating concern for the future, maintaining behavioral control, exploring opportunities, and building confidence, which contributes to the development of subjective perceptions of decent work (32).

In summary, existing literature and theoretical perspectives suggest that self-control and career adaptability are important personal resources associated with decent work. However, empirical studies exploring these associations among psychiatrists remain limited. Guided by the PWT framework, this study examines the relationships among self-control, career adaptability, and perceptions of decent work among psychiatrists. This research provides theoretical insights into psychiatrists’ work experiences in high-pressure and complex clinical environments and offers practical implications for enhancing their professional well-being and supporting the sustainability of mental health service systems.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This study used a cross-sectional design and followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. Details are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2 Sample

This study used convenience sampling to recruit psychiatrists from eight psychiatric hospitals in eastern China (Zhejiang Province), central China (Anhui Province), and western China (Sichuan Province). The provinces included in this study differ in economic development, healthcare resources, and mental health service capacity, which provides a degree of regional representativeness. All participating hospitals were tertiary-level psychiatric hospitals, ensuring a relatively high and comparable standard of clinical service and organizational structure across sites.

Inclusion criteria: officially employed staff; registered psychiatrists; voluntary participation in this study.

Exclusion criteria: clinical students; physicians not working in clinical practice; voluntary withdrawal during the study.

2.3 Sample size

The required sample size was estimated using Kendall’s rule, which recommends a sample size 10 to 20 times the number of variables. With 12 variables included in this study, the required sample size ranged from 120 to 240 participants. Allowing for a 20 percent invalid response rate, the minimum required sample size was set at 142.

A total of 556 questionnaires were collected. After removing incomplete or illogical responses, 517 valid questionnaires were retained. The valid response rate was 93.0%.

2.4 Instruments

2.4.1 Demographic information

The demographic information questionnaire was developed by the research team and includes items on gender, age, educational background, years of working, professional title, marital status, parental status, monthly income, and employment status.

2.4.2 Self-Control Scale

The Self-Control Scale was originally developed by Tangney and colleagues (33) and subsequently revised by Tan Shuhua to better reflect characteristics of traditional Chinese culture (34). The revised scale conceptualizes self-control across five dimensions. It retains the original dimensions of impulse control, healthy habits, and focused work, and adds two culturally grounded dimensions: resistance to temptation and moderation of entertainment. The instrument comprises 19 items rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Items 1, 5, 11, and 14 are scored positively, and the remaining items are reverse-scored. Total scores range from 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating stronger self-control. In the present study, the scale demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.914.

2.4.3 Career Adapt-Abilities Scale

The Career Adapt-Abilities Scale was developed by Savickas and colleagues to assess individuals’ career adaptability (17). The Chinese version was translated and adapted by Hou (35). The scale contains four dimensions: career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence. It includes 24 items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very little ability) to 5 (very strong ability). Total scores range from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating greater career adaptability. In this study, the instrument showed excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.976.

2.4.4 Decent Work Perception Scale

The Decent Work Perception Scale was developed by Mao Guanfeng and colleagues in 2013 to assess individuals’ perceptions of decent work (36). The scale includes five dimensions: work rewards, job position, career development, professional recognition, and work environment. It consists of 16 items, each rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Total scores range from 16 to 80, with higher scores reflecting a stronger perception of decent work. In this study, the scale demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.941.

2.5 Data collection

Data were collected through an online survey platform. All questionnaires were converted into scannable QR codes by the research team. After obtaining consent from the heads of the participating hospitals, the researchers sent the QR codes to these hospital leaders along with an explanation of the study purpose, data collection procedures, and informed consent requirements. The hospital leaders distributed the QR codes to physicians through their work groups. The questionnaire consisted of three components: an introduction, an informed consent form, and the survey items. The introduction described the study objectives and provided instructions for completing the questionnaire. The informed consent form emphasized anonymity, minimal risk, and voluntary participation. Respondents who agreed to participate could proceed to the survey, whereas those who declined were redirected to an exit page. To reduce potential response bias, each IP address was allowed only one submission.

2.6 Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the variables. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations. One-way ANOVA and independent-samples t-tests were used to examine the effects of demographic characteristics on perceptions of decent work. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to assess associations among career adaptability, self-control, and decent work perception. Stepwise multiple linear regression was used to identify predictors of decent work perception. Mediation effects were tested using the PROCESS macro, with Model 4 selected to assess the mediating role. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

2.7 Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Mental Health Center and Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2024018). Ethical approval was obtained before data collection began. Consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, all participants received comprehensive information about the study purpose, procedures, and potential risks. Informed consent was obtained from every participant prior to participation.

3 Results

3.1 Common method bias test

Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess potential common method bias. The first unrotated factor explained 38.08% of the total variance, lower than the commonly accepted threshold of 40% (37). This result suggests that common method bias was not a substantial threat to the validity of the study.

3.2 Demographic characteristics of participants

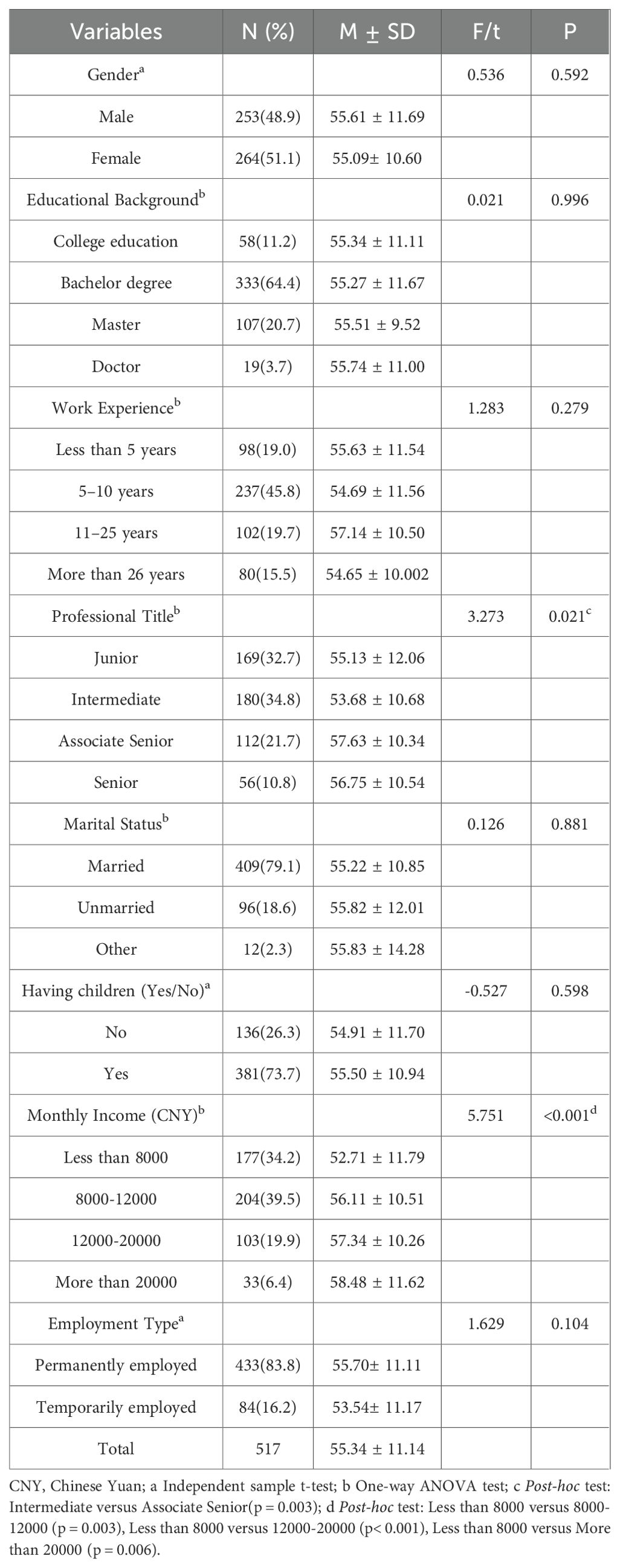

A total of 517 psychiatrists participated in this study. The mean age was 38.12 ± 8.69 years. Among them, 253 participants (48.9%) were male and 264 (51.1%) were female. A total of 237 participants (45.8%) reported 5 to 10 years of work experience. Most respondents held intermediate professional titles (180, 34.8%), followed by junior titles (169, 32.7%). The majority were married (409, 79.1%), and 381 (73.7%) had children. Monthly income most frequently ranged from 8,000 to 12,000 CNY (204, 39.5%). Additionally, 433 psychiatrists (83.8%) were permanent staff members. See Table 1.

3.3 Influence of sociodemographic factors on decent work

The findings indicated that among the examined sociodemographic variables, professional title and monthly income significantly influenced psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. Specifically, significant differences were observed between participants with intermediate and associate senior titles (p = 0.003). Monthly income also had a significant effect on decent work perception: individuals earning less than 8,000 RMB scored lower than those earning 8,000–12,000 RMB (p = 0.003), 12,000–20,000 RMB (p < 0.001), and more than 20,000 RMB (p = 0.006). These results suggest that higher income levels are associated with higher perceptions of decent work among psychiatrists.

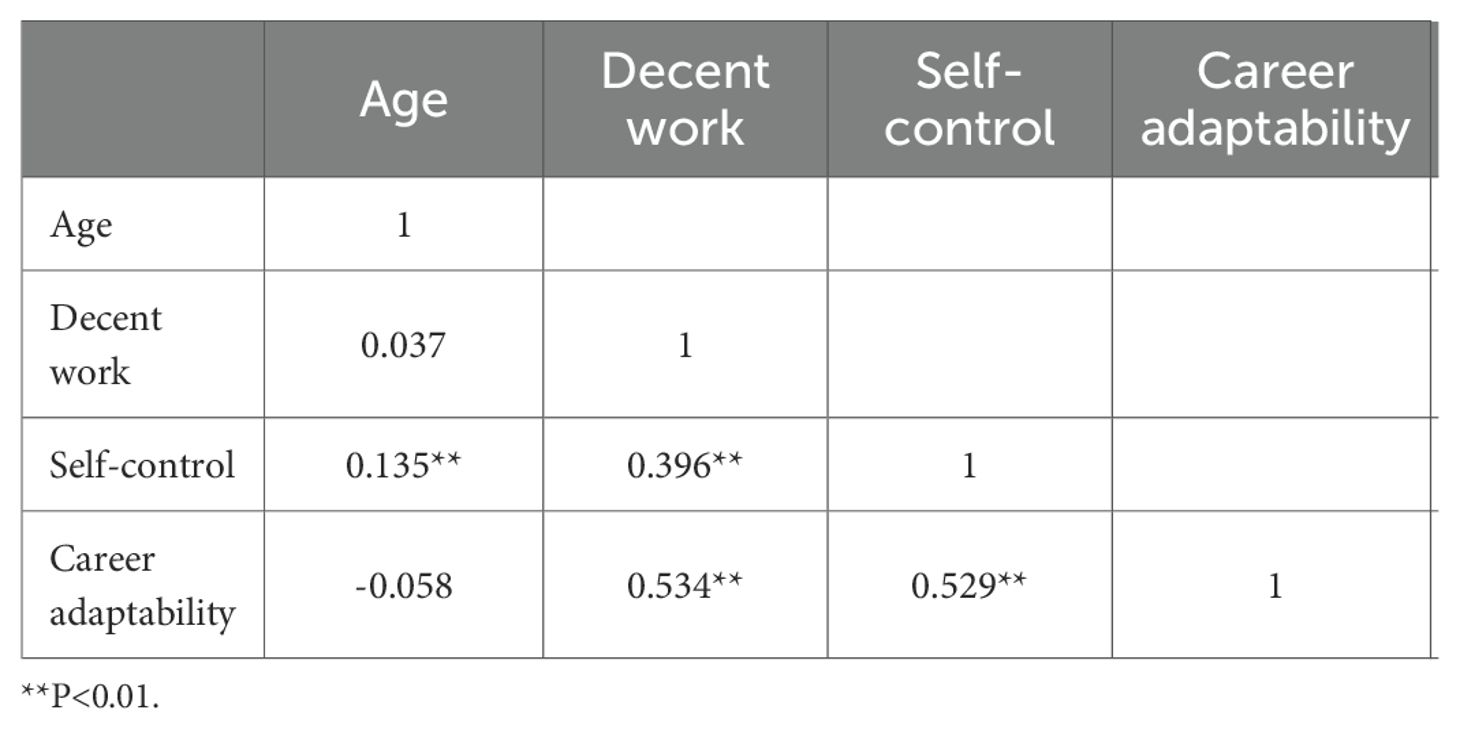

3.4 Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations among the core study variables. Career adaptability was positively associated with decent work perception (r = 0.534, p < 0.01), and self-control also showed a positive association with decent work perception (r = 0.396, p < 0.01). In addition, self-control demonstrated a significant positive correlation with career adaptability (r = 0.529, p < 0.01). See Table 2.

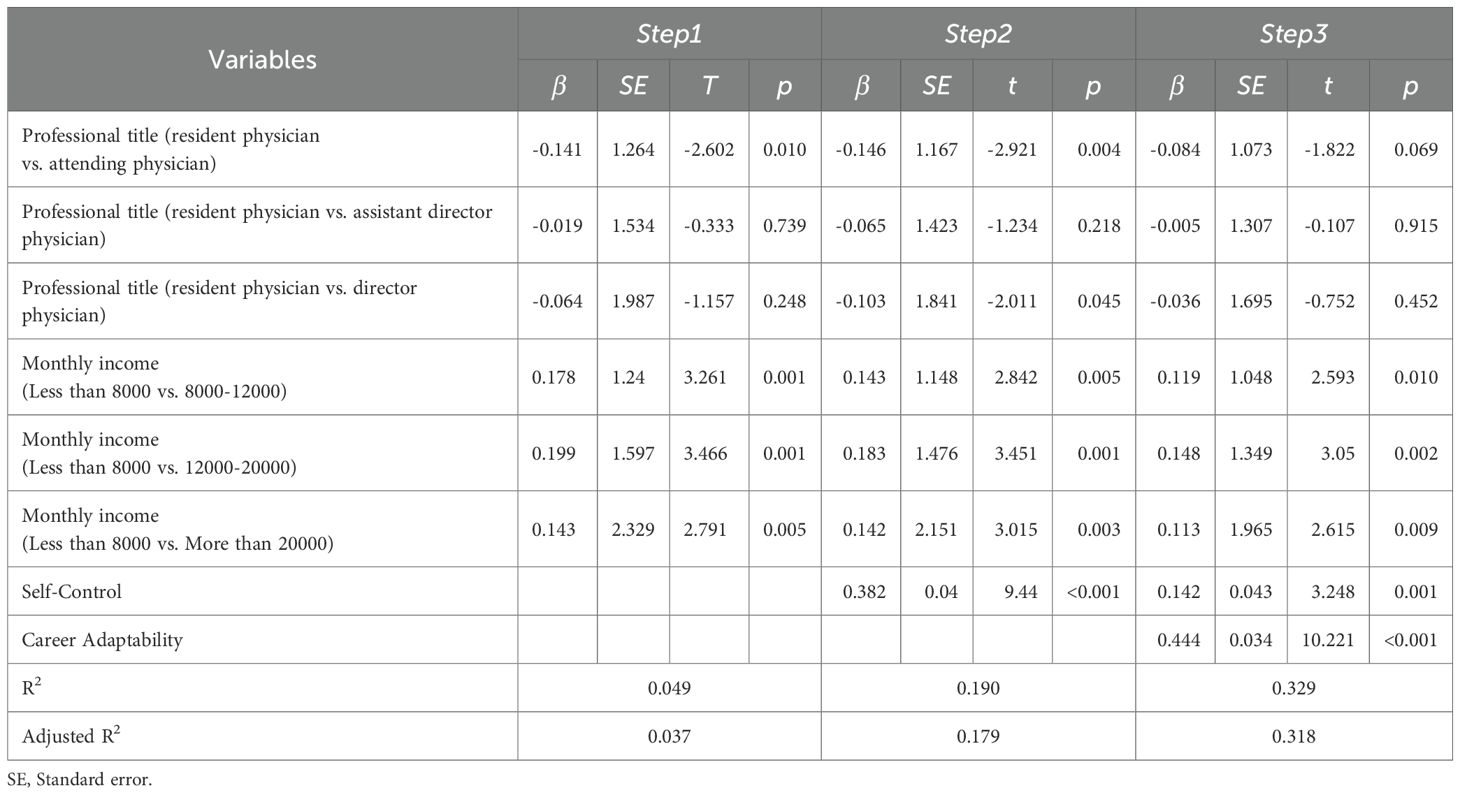

3.5 Multivariate regression analysis

As shown in Table 3, in the first step of the hierarchical regression analysis, professional title and monthly income, identified as significant factors in the univariate analysis, were entered into the model as categorical variables using dummy coding. Resident physician and monthly income less than 8,000 RMB were used as the reference categories. Monthly income remained significantly associated with perceptions of decent work. Compared with psychiatrists earning less than 8,000 RMB, significant differences were found among those earning 8,000–12,000 RMB (β = 0.178, p = 0.001), 12,000–20,000 RMB (β = 0.199, p = 0.001), and more than 20,000 RMB (β = 0.143, p = 0.005). For professional title, attending physician reported significantly different perceptions of decent work compared with resident physician (β = -0.141, p = 0.010). No significant differences were observed between resident physician and associate chief physicians (β = -0.019, p = 0.739), or between resident physician and chief physicians (β = -0.064, p = 0.248). The R² value for this step was 0.049, indicating that demographic variables explained 4.9% of the variance in decent work perceptions.

In the second step, self-control was added to the model and demonstrated a significant association with decent work (β = 0.382, p < 0.001). After including self-control, the effects of professional title and monthly income on decent work perceptions were somewhat attenuated but remained significant. The R² value increased from 0.049 to 0.190, suggesting that the model explained 19.0% of the variance in decent work perceptions after accounting for self-control.

In the third step, career adaptability was entered into the model. Career adaptability showed a significant positive association with decent work (β = 0.444, p < 0.001). Self-control also remained significantly associated with decent work (β = 0.142, p = 0.001). After career adaptability was added, the effect of professional title further weakened, and the difference between resident physician and attending physician was no longer statistically significant (β = -0.084, p = 0.069). The R² value increased to 0.329, indicating that the final model accounted for 32.9% of the variance in decent work perceptions.

To assess multicollinearity, we examined tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Tolerance indicates the proportion of variance in each predictor that is not explained by other predictors, with values below 0.10 typically considered problematic. VIF reflects the degree to which the variance of a regression coefficient is inflated by multicollinearity, and values above 10 are commonly viewed as indicative of concern. In this study, all tolerance values exceeded 0.56 and all VIF values ranged from 1.41 to 1.77, confirming that multicollinearity was not a concern.

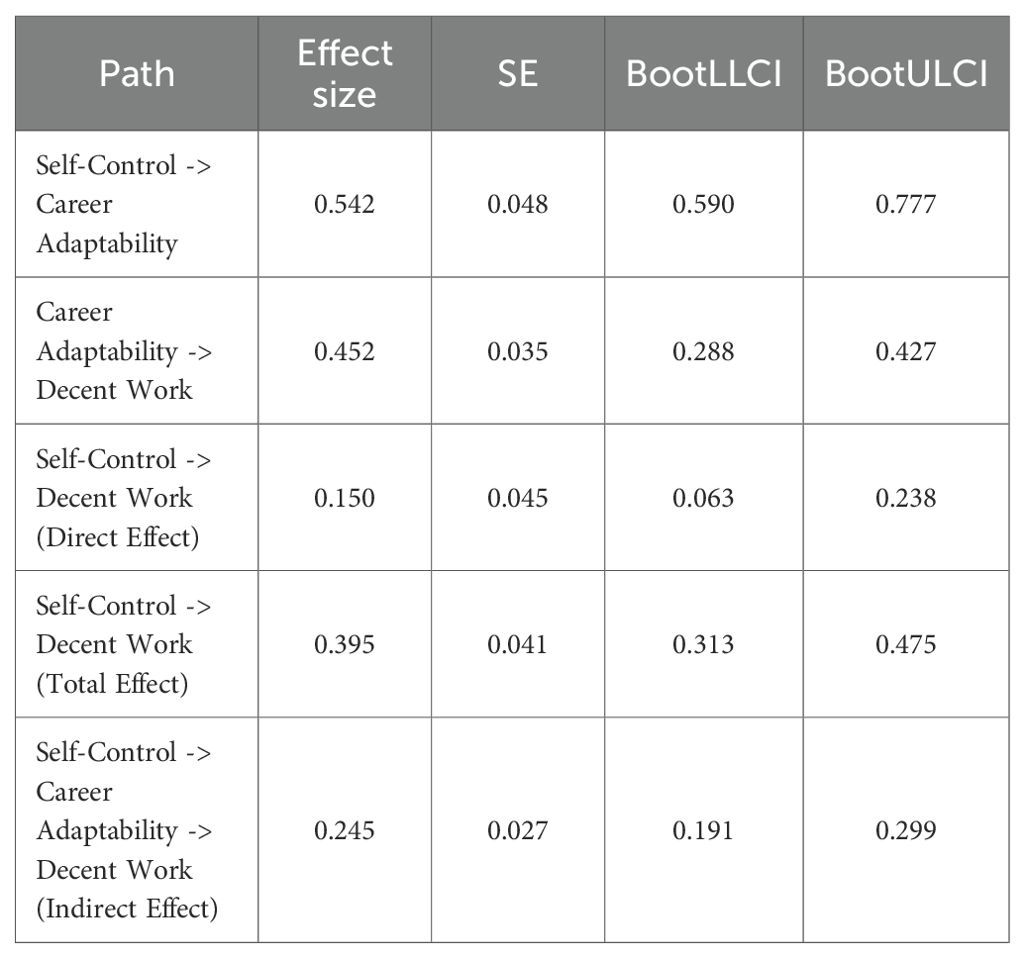

3.6 Mediation analysis

In this study, self-control demonstrated both direct and indirect associations with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. The direct effect of self-control on decent work was statistically significant (β = 0.157, p < 0.001). Self-control was also positively associated with career adaptability (β = 0.529, p < 0.001). In turn, career adaptability showed a significant positive association with decent work (β = 0.451, p < 0.001).

The indirect effect of self-control on decent work through career adaptability was significant (β = 0.239, 95% CI [0.187, 0.296]), suggesting that career adaptability partially mediated this association. The total effect of self-control on decent work remained statistically meaningful (β = 0.396, p < 0.001). See Table 4.

Table 4. Path analysis results for the effects of self-control and career adaptability on decent work.

4 Discussion

In this study, several sociodemographic and psychological factors were associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. Professional title and monthly income showed significant relationships with decent work, indicating that individuals with higher professional status and higher earnings tend to report a more favorable perception of their work conditions. Psychological variables also played an important role. Both self-control and career adaptability were positively related to perceptions of decent work. Moreover, self-control demonstrated both direct and indirect associations with decent work through career adaptability. This pattern suggests that individuals with higher self-control may develop stronger career adaptability, which in turn contributes to a higher perception of decent work. In sum, career adaptability serves as a meaningful explanatory mechanism linking self-control to psychiatrists’ evaluations of the quality and dignity of their work.

The associations between professional title, income level, and perceptions of decent work align with patterns documented in prior research and extend the understanding of decent work within the psychiatric workforce. Senior physicians generally possess greater clinical experience and domain-specific expertise, which enables them to make informed long-term decisions, manage complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, and exercise higher levels of autonomy and authority. These factors enhance their professional standing and the recognition they receive (38). It is noteworthy that after career adaptability was included in the model, the association between professional title and perceptions of decent work was no longer statistically significant. This finding suggests that the initial differences observed between resident physicians and attending physicians may, to some extent, be attributable to underlying psychological resources rather than professional rank alone. In China, psychiatrists across different professional titles are often exposed to similarly high levels of workload, sustained emotional labor, elevated clinical risk, and stringent institutional constraints (39, 40). Under such conditions, individual differences in career adaptability may play a more proximal role than hierarchical status in shaping psychiatrists’ subjective perceptions of work quality, dignity, and decency. Similarly, higher monthly income was strongly linked to a greater sense of decent work, consistent with findings from research conducted in nursing (41). Economic remuneration plays a central role in shaping whether individuals feel fairly rewarded for their contributions. Evidence from China indicates that low wages are among the top three contributors to job dissatisfaction among psychiatrists (42). The literature further highlights that income is closely related to perceptions of fairness and the capacity to maintain a reasonable standard of living, both of which are integral components of decent work (25). Professional status and adequate financial compensation are also key determinants of job satisfaction among healthcare professionals, suggesting that improvements in decent work conditions may simultaneously enhance psychiatrists’ job satisfaction and retention (10).

Moreover, the findings of this study indicate that self-control constitutes an important factor associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. Self-control is closely associated with intrinsic motivation and effective self-regulation strategies and has been conceptualized as a psychological resource that supports sustained task performance (43). In psychiatric practice, clinicians routinely encounter emotionally charged and cognitively demanding situations. Self-control requirements such as emotion regulation and distraction management form a substantial part of their daily work. Previous research has shown that when self-control demands accumulate or are poorly managed, they are associated with higher stress levels and reduced well-being among clinicians (44, 45). These findings indicate that greater emphasis should be placed on the role of self-control within the mental health workforce. Developing targeted interventions that enhance self-regulatory skills may enable psychiatrists to navigate professional development more effectively and mitigate stress-related challenges inherent in their clinical work.

This study also indicates that career adaptability is closely associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work, a finding consistent with prior research in the teaching profession (46). Career adaptability is conceptualized as a self-regulatory resource; individuals with higher levels of adaptability tend to experience fewer negative outcomes, which contributes to reduced stress and higher job satisfaction. (47). In contrast, lower career adaptability has been associated with a reduced likelihood of engaging in decent work (48). For psychiatrists, who frequently encounter complex clinical demands and emotionally intensive practice environments, career adaptability functions as an important psychological resource that supports well-being and a sense of professional fulfillment.

Finally, the results of this study show that career adaptability mediates the relationship between self-control and decent work, lending further support to the PWT. Self-control is critical in professional contexts because it enables individuals to regulate their behaviors and emotions effectively It helps professionals respond thoughtfully to challenging situations, avoid impulsive reactions, and remain focused on long-term objectives rather than short-term distractions (49, 50). This capacity facilitates continuous improvement, goal attainment, and sustained career development. Enhanced career adaptability, in turn, positively shapes individuals’ perceptions of decent work by aligning their work experiences with personal values and long-term career goals (51). Moreover, the mediation effect was moderate in size (β = 0.245), indicating that career adaptability plays an important role in the process through which self-control is reflected in psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. Given the emotional demands and cognitive complexity inherent in psychiatric practice, individuals who are able to regulate their emotions and behaviors effectively may be better positioned to develop adaptive strategies that support more positive work experiences. In this context, career adaptability functions as a meaningful psychological resource rather than a peripheral factor and contributes to how psychiatrists understand the quality, dignity, and sustainability of their professional work. Therefore, managers play a pivotal role in cultivating environments that support the development of self-control and career adaptability. Such efforts may contribute to strengthening psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work and enhancing their overall professional well-being.

Finally, the results of this study indicate that career adaptability mediates the relationship between self-control and perceptions of decent work, which is consistent with our proposed hypothesis (25). While prior research has primarily conceptualized career adaptability as a psychological resource that directly facilitates access to decent work (32), the present findings further suggest that the effective enactment of career adaptability is closely linked to individuals’ capacity for self-control. Self-control enables individuals to maintain stable behavioral engagement and regulate emotional responses in work contexts characterized by high emotional demands and substantial uncertainty, thereby providing the necessary conditions for the development and activation of career adaptability (49). The mediating effect of career adaptability was of moderate magnitude (β = 0.245), indicating that it plays a meaningful role in the pathway through which self-control relates to psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. Career adaptability has been widely recognized as a key psychological resource supporting career sustainability, subjective well-being, and experiences of decent work (28, 41). Under conditions of high emotional labor, clinical uncertainty, and structural constraints faced by psychiatrists, career adaptability not only facilitates sustained occupational engagement and goal-directed behavior but also helps buffer occupational stress, reduce the risk of burnout, and enhance perceptions of work meaning and dignity (28, 52). Accordingly, managers who promote the development of self-control and career adaptability are better positioned to enhance psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work and support their sustained professional well-being.

4.1 Implication

This study provides several implications for discussions concerning the working conditions of psychiatrists. First, sustained attention to socioeconomic support is essential, as income was closely associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work. This suggests that healthcare administrators and policymakers should prioritize fair and competitive compensation systems and transparent pathways for career advancement. Additional benefits such as paid leave, comprehensive health insurance, and housing allowances may further strengthen psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work (53). Second, the associations observed between self-control, career adaptability, and perceptions of decent work indicate that these psychological resources are integral to psychiatrists’ professional functioning. Training initiatives focused on emotional regulation and impulse control may help psychiatrists maintain psychological stability under high-pressure clinical conditions (54, 55). Team-based exercises, scenario-based simulations, and structured problem-solving activities can also enhance adaptability and career resilience, thereby fostering stronger perceptions of decent work (56). Finally, this study extends the application of the PWT to the context of psychiatric professionals. While previous research has often conceptualized career adaptability as a universally applicable psychological resource directly associated with the attainment of decent work, the present study highlights the foundational role of self-control in enabling career adaptability within the psychiatric profession. In an occupational context characterized by sustained emotional labor, clinical uncertainty, and limited control over structural conditions, the ability to maintain emotional stability and behavioral consistency is closely associated with the effective utilization of career adaptability. By clarifying the link between self-control and career adaptability, this study refines a key mechanism within the PWT framework and offers a direction for future theoretical development focused on career functioning in high-pressure professional environments such as psychiatry.

4.2 Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to draw causal conclusions from the observed associations. Future longitudinal or experimental research is needed to clarify the causal pathways linking self-control, career adaptability, and perceptions of decent work. Second, the study relies on self-reported data from psychiatrists, which may be influenced by social desirability or self-presentation tendencies. Subsequent studies could draw on multiple data sources, including qualitative approaches, to obtain a more comprehensive understanding. Third, this study intentionally focused on individual-level self-regulatory and adaptive processes, specifically self-control and career adaptability, and did not incorporate contextual factors such as work environment, social support, or organizational culture. Although these contextual variables were beyond the scope of the present study, they may also play important roles in shaping psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work and should be examined in future research. In addition, the DWPS used in this study was developed by Chinese scholars and is grounded in the local cultural context. Its applicability across different cultural settings may be limited. Future research could benefit from cross-cultural validation of the DWPS and comparative studies across different countries or cultural groups. The hospitals included in this study were all located in three provinces, which may further limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies could expand sampling to additional regions and conduct broader investigations on the status and determinants of decent work among psychiatrists nationwide.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study offers important insights into factors associated with psychiatrists’ perceptions of decent work in China. The results highlight the contribution of sociodemographic characteristics, such as income and professional title, as well as psychological attributes, including self-control and career adaptability. These findings provide direction for efforts aimed at improving the working conditions of psychiatrists and support the long-term sustainability of mental health services.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Mental Health Center & Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine(No. 2024018). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XZ: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Data curation. LW: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HW: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. SZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. ZJ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation. BX: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Methodology. HL: Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Medical and Health Research Program of Zhejiang Province, China (2025KY1137).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the physicians who participated.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Braslow J. Mental ills and bodily cures: Psychiatric treatment in the first half of the twentieth century. Berkeley, CA, USA: Univ of California Press (2023).

2. Cornaggia CM, Beghi M, Pavone F, and Barale F. Aggression in psychiatry wards: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2011) 189:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.024

3. Eckleberry-Hunt J and Lick D. Physician depression and suicide: a shared responsibility. Teach Learn Med. (2015) 27:341–5. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1044751

4. Yang Y, Zhang L, Li M, Wu X, Xia L, Liu DY, et al. Turnover intention and its associated factors among psychiatrists in 41 tertiary hospitals in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:899358. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.899358

5. Bykov KV, Zrazhevskaya IA, Topka EO, Peshkin VN, Dobrovolsky AP, Isaev RN, et al. Prevalence of burnout among psychiatrists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2022) 308:47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.005

6. Kastrup M, Heinz A, and Wasserman D. Exemplary contribution of professional scientific organizations: the european psychiatric association. Stigma Ment Illness-End Story? (2017), 627–33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-27839-1_36

7. Bhugra D, Sartorius N, Fiorillo A, Evans-Lacko S, Ventriglio A, Hermans MHM, et al. EPA guidance on how to improve the image of psychiatry and of the psychiatrist. Eur Psychiatry. (2015) 30:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.02.003

8. Gaebel W, Zäske H, Zielasek J, Cleveland HR, Samjeske K, Stuart H, et al. Stigmatization of psychiatrists and general practitioners: results of an international survey. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2015) 265:189–97. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0530-8

9. Sengenberger W. Decent work: the international labor organization agenda. Dialogue Cooperation. (2001) 2:39–55.

10. Yao H, Wang P, Tang Y-L, Liu Y, Liu T, Liu H, et al. Burnout and job satisfaction of psychiatrists in China: a nationwide survey. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:593. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03568-6

11. Xia L, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Liu T, Liu Y, Jiang F, et al. Violence, burnout, and suicidal ideation among psychiatry residents in China. Asian J Psychiatry. (2022) 76:103229. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103229

12. Pechorro P, Delisi M, Quintas J, Gonçalves RA, and Maroco J. Investigating sex-related moderation effects and mediation effects of self-control on delinquency among portuguese youth. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminology. (2021) 65:882–98. doi: 10.1177/0306624X20981037

13. Schmidt KH, Neubach B, and Heuer H. Self-control demands, cognitive control deficits, and burnout. Work Stress. (2007) 21:142–54. doi: 10.1080/02678370701431680

14. Liu YZ and Wang YJ. Self-control and organizational citizenship behavior: The role of vocational delay of gratification and job satisfaction. Work. (2021) 68:797–806. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203413

15. Lai R, Teoh K, and Plakiotis C. The impact of changes in mental health legislation on psychiatry trainee stress in victoria, Australia. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2023) 1425:199–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_19

16. Glushkova A and Semenova N. Working conditions and their effect on the health level of psychiatric staff (literature review). VM Bekhterev Rev Psychiatry Med Psychol. (2020) 1, 3–7. doi: 10.31363/2313-7053-2020-1-3-7

17. Savickas ML and Porfeli EJ. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J vocational Behav. (2012) 80:661–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

18. Tahiry MA and Ekmekcioglu EB. Supervisor support, career satisfaction, and career adaptability of healthcare sector employees. Vilakshan-XIMB J Manage. (2023) 20:292–301. doi: 10.1108/XJM-09-2021-0247

19. Hassan S, Ali MA, Rafiq S, Rizvi SMA, and Ahmad I. Career Adaptability and Job Engagement: Testing the mediating effect of Orientation to Happiness in the Healthcare sector. J Excellence Manage Sci. (2024) 3:34–48. doi: 10.69565/jems.v3i2.235

20. Chan SHJ and Mai X. The relation of career adaptability to satisfaction and turnover intentions. J Vocational Behav. (2015) 89:130–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.05.005

21. Rudolph CW, Lavigne KN, and Zacher H. Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. J vocational Behav. (2017) 98:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.09.002

22. Zhang X, Yu L, Chen Y, Fu Z, Zhang F, Li Z, et al. Career adaptability and career coping styles among Chinese medicine specialty students during the COVID-19: The mediating role of career decision-making self-efficacy. Heliyon. (2024) 10. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34578

23. Prasad J, Gardner DM, Leong FT, Zhang J, and Nye CD. The criterion validity of career adapt–abilities scale with cooperation among Chinese workers. Career Dev Int. (2021) 26:252–68. doi: 10.1108/CDI-04-2020-0106

24. Liu L, Liu M, Lv Z, Mao Y, and Liu Y. Self-awareness and career adaptability of new nurses in the oncology hospital: a chain mediating model of creative self-efficacy and work readiness. Curr Psychol. (2024) 43:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-06151-w

25. Duffy RD, Blustein DL, Diemer MA, and Autin KL. The psychology of working theory. J Couns Psychol. (2016) 63:127. doi: 10.1037/cou0000140

26. Uhlig L, Baumgartner V, Prem R, Siestrup K, Korunka C, and Kubicek B. A field experiment on the effects of weekly planning behavior on work engagement, unfinished tasks, rumination, and cognitive flexibility. J Occup Organizational Psychol. (2023) 96:575–98. doi: 10.1111/joop.12430

27. Williamson LZ and Wilkowski BM. Nipping temptation in the bud: Examining strategic self-control in daily life. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2020) 46:961–75. doi: 10.1177/0146167219883606

28. Wu H, Zhu S, Wang L, Yuan H, Xue B, and Luo H. The relationship between career adaptability, decent work, job satisfaction and burnout among psychiatrists: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2025) 25:888. doi: 10.1186/s12888-025-07343-9

29. Xu Y, Liu D, and Tang DS. Decent work and innovative work behavior: Mediating roles of work engagement, intrinsic motivation and job self-efficacy. Creativity Innovation Management. (2022) 31, 49–63. doi: 10.1111/caim.12480

30. Clinton M, Conway N, Sturges J, and Hewett R. Self-control during daily work activities and work-to-nonwork conflict. J Vocational Behavior. (2020) 118, 103410. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103410

31. Klehe U-C, Fasbender U, and Horst A. Going full circle: Integrating research on career adaptation and proactivity. J Vocational Behavior. (2021) 126, 103526. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103526

32. Marcionetti J, Zambelli C, and Rossier J. Influence of career adaptability and job control on decent work and occupational stress in a sample of apprentices. J Career Dev. (2024) 52:95–111. doi: 10.1177/08948453241304328

33. Tangney JP, Boone AL, and Baumeister RF. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. In: Self-regulation and self-control. London, UK: Routledge (2018).

34. Tan S-H and Guo Y-Y. Revision of self-control scale for Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2008) 16, 468–470.

35. Hou Z-J, Leung SA, Li X, Li X, and Xu H. Career adapt-abilities scale—China form: Construction and initial validation. J Vocational Behav. (2012) 80:686–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006

36. Mao G, Liu W, and Song H. Perceived decent work: scale development and validation. Stat Decision. (2014) 30:86–9.

37. Hair JF Jr., Black WC, Babin BJ, and Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall: London (2010).

38. Nilsson MS and Pilhammar E. Professional approaches in clinical judgements among senior and junior doctors: Implications for medical education. BMC Med Educ. (2009) 9, 25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-25

39. Yue J-L, Li N, Que J-Y, Hu S-F, Xiong N-N, Deng J-H, et al. Workforce situation of the Chinese mental health care system: results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:562. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04204-7

40. Xia L, Jiang F, Rakofsky J, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Zhang K, et al. Resources and workforce in top-tier psychiatric hospitals in China: A nationwide survey. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:573333. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.573333

41. Xue B, Feng Y, Li X, Hu Z, Zhao Y, Ma W, et al. Unveiling nurses’ perspectives on decent work: A qualitative exploration. Int Nurs Rev. (2024) 72, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/inr.13041

42. Jiang F, Hu L, Rakofsky J, Liu T, Wu S, Zhao P, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics and job satisfaction of psychiatrists in China: Results from the first nationwide survey. Psychiatr Serv. (2018) 69:1245–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800197

43. Wehrt W, Casper A, and Sonnentag S. More than a muscle: How self-control motivation, depletion, and self-regulation strategies impact task performance. J Organizational Behav. (2022) 43:1358–76. doi: 10.1002/job.2644

44. Rivkin W and Schmidt KH. Resources buffering the day-specific relations between work-related self-control demands and employee well-being. Psychol Self-Control: New Res. (2016), 73–102.

45. Neubach B and Schmidt KH. Main and interaction effects of different self-control demands on indicators of job strain. Z fur Arbeits- und Organizations Psychol. (2008) 52:17–24. doi: 10.1026/0932-4089.52.1.17

46. Wen Y, Chen H, Liu F, and Wei X. The relationship between career calling and resilience among rural-oriented pre-service teachers: the chain mediating role of career adaptability and decent work. Behav Sci. (2024) 14, 11. doi: 10.3390/bs14010011

47. Fiori M, Bollmann G, and Rossier J. Exploring the path through which career adaptability increases job satisfaction and lowers job stress: The role of affect. J Vocational Behav. (2015) 91:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.08.010

48. Vilhjálmsdóttir G. Young workers without formal qualifications: experience of work and connections to career adaptability and decent work. Br J Guidance Counselling. (2021) 49:242–54. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2021.1885011

49. Gordeeva TO, Osin EN, Suchkov DD, Ivanova TY, Sychev OA, and Bobrov VV. Self-control as a personal resource: determining its relationships to success, perseverance, and well-being. Russian Educ Soc. (2017) 59:231–55. doi: 10.1080/10609393.2017.1408367

50. Cruz JFA and Sofia RM. The pursuit of success and excellence: Self-control in achievement contexts. Psychol Self-Control: New Res. (2016), 33–72.

51. Su X, Wong V, and Liang K. Effects of contextual constraints, work volition, and career adaptability on decent work conditions among young adult social workers: a moderated mediation model. Int J Adolescence Youth. (2023) 28:2245451. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2023.2245451

52. Russo RA, Dallaghan GB, Balon R, Blazek MC, Goldenberg MN, Spollen JJ, et al. Millennials in psychiatry: exploring career choice factors in Generation Y psychiatry interns. Acad Psychiatry. (2020) 44:727–33. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01272-3

53. Goodman JM and Schneider D. The association of paid medical and caregiving leave with the economic security and wellbeing of service sector workers. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21, 1969. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11999-9

54. Hasani J and Shahmoradifar T. Effectiveness of process emotion regulation strategy training in difficulties in emotion regulation. J Military Med. (2016) 18:339–46.

55. Badri R, Vahedi S, Bairami M, and Einipour J. Effect of emotion regulation skill training based on dialectical behavior therapy upon affective styles. Soc Sci (Pakistan). (2015) 10:712–7.

Keywords: career adaptability, cross-sectional study, decent work, psychiatrists, self-control

Citation: Zhang X, Wang L, Wu H, Zhu S, Jiang Z, Xue B and Luo H (2026) Factors associated with decent work among psychiatrists: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 17:1617618. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2026.1617618

Received: 24 April 2025; Accepted: 05 January 2026; Revised: 22 December 2025;

Published: 23 January 2026.

Edited by:

Angela Stufano, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyReviewed by:

Abdul Haeba Ramli, Universitas Esa Unggul, IndonesiaHakan Büyükçolpan, Bülent Ecevit University, Türkiye

Mehtap Kızılkaya, Adnan Menderes University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2026 Zhang, Wang, Wu, Zhu, Jiang, Xue and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Luo, aHpsdW9ob25nQHpqdS5lZHUuY24=; Bowen Xue, Ym93ZW4uaHpAZm94bWFpbC5jb20=

Xiaolan Zhang1

Xiaolan Zhang1 Huaineng Wu

Huaineng Wu Bowen Xue

Bowen Xue Hong Luo

Hong Luo