- 1Department of Engineering Science, Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan

- 2Yonenosho Elementary School, Matsusaka, Mie, Japan

- 3Department of Neuropsychiatry, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki, Japan

- 4Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

- 5AI Lab, Department of Artificial Intelligence, CyberAgent, Inc., Tokyo, Japan

- 6Department of Education, Elementary School Attached to Mie University Faculty of Education, Tsu, Mie, Japan

Educational institutions are facing a critical shortage of teachers worldwide. Consequently, the trend of introducing interactive robots into educational sites is growing. However, most previous research focused on specific subjects or time slots, and only a few studies have introduced interactive robots to participate in whole classroom activities with children routinely. This study investigates the use of avatar robots operated by multiple remote operators in elementary school classrooms. Over nine days, a 5th-grade class was observed to assess the robot’s impact on student engagement, motivation, and peer interactions, and compared to classes where any avatar robots were not introduced. Key findings include improved student confidence in presentations, enhanced social interactions during recess, and positive feedback on the robot’s role in supporting classroom activities. The results suggest that avatar robots, with consistent remote operation, can provide valuable educational support without strong negative reactions from students.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the shortage of teachers has become a severe problem in the Japanese educational field (Ministry of Education and Culture and Sports and Science and Technology, 2022). Teacher shortages are a global issue, as highlighted in the report by OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020). Excessive workload on teachers and US and UK government policies (Perryman and Calvert, 2020; Ingersoll et al., 2016) has been shown to lead teacher resignations (Ingersoll and Smith, 2003). Furthermore, declining social status of teachers and low salaries (Wiggan et al., 2021; Han et al., 2018) are considered to cause the reluctance of the young generation to the teacher profession.

In response to these challenges, researchers and policymakers are increasingly recommending the utilization of community resources to support education (Giraudeau and Bailly, 2019; Canedo-Garcia et al., 2017). Initiatives, where older adults support young people in educational settings, are being introduced worldwide (Newman and Hatton-Yeo, 2008). Such an initiative is advantageous because it also ensures opportunities for social activities for older adults (Galbraith et al., 2015). Collaboration between schools and communities have been promoted by the governments in Japan (Ministry of Education and Culture and Sports and Science and Technology, Report of the Central Council for Education, 2015) as well as in other countries (Newman and Hatton-Yeo, 2008). However, several practical problems have also been highlighted, including the time constraints of educational supporters, restrictions on the range of movement of elderly educators owing to the aging-related decline in physical abilities, and confusion experienced by children with outsiders (Newman and Hatton-Yeo, 2008; Murayama et al., 2019), which makes it difficult to supply necessary human resources. Governmental support for school-community collaboration such as providing sufficient budget and human resources has been concerned to be insufficient in Japan (Shimojo, 2020). Meanwhile, there is another concern for children to experience confusion with outsiders in such a collaboration (Newman and Hatton-Yeo, 2008; Murayama et al., 2019). In Japan, lack of consensus to treat outsiders (i.e., community supporters) in school has been pointed out to enhance this confusion (Yoshida and Yoshizawa, 2024). On the other hand, the telepresence robot is expected to allow users to work against these constraints, and therefore has been attempted to allow people to engage in educational support from a distance (Kasuk and Virkus, 2024).

In recent years, increasing attention has been focused on using avatars to enable individuals to work from different locations and provide services remotely, thereby overcoming spatial and time constraints (Ishiguro, 2021; Baba et al., 2020; Nakanishi et al., 2021). The use of social robots as avatars is gaining increasing interest in educational contexts because of the expectation that children may feel less resistant when interacting with them. This has led to an increase in the number of initiatives that incorporate avatars into educational settings (Belpaeme et al., 2013; Nakanishi et al., 2022). For example, Komatsubara et al. developed a science learning support system using a semi-autonomous robot with a remote operator to provide science-related dialogues during recess (Komatsubara et al., 2015). Yun et al. demonstrated that a robot named EngKey, which was introduced in 29 elementary schools for 3 months and was remotely operated by a teacher in the Philippines to teach English to South Korean students, could improve the grades of students (Yun et al., 2011). Moreover, Hashimoto et al. showed that children were highly motivated to participate in class when an android robot called SAYA, which was operated by a remote operator who acted as a teacher, was used in a classroom (Hashimoto et al., 2011). In previous studies, avatar robots have been used for limited tasks, for example, as classroom teachers in specific classes (Hashimoto et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 2013) and as teaching assistants in specific classes (Yamazaki et al., 2012; Nakanishi et al., 2022). Most of the research has been focused on class time, which is not recess. By contrast, the systematic review by Hodges et al. confirmed numerous benefits of recess for children, including academic and cognitive benefits, behavioral and emotional benefits, physical benefits, and social benefits, which can collectively improve their academic performance (Hodges et al., 2022). Although related research has introduced robots during recess (Kanda et al., 2007), previous studies neither supported entire classroom activities, including during recess nor did they support interpersonal relationships, which cannot be established (Murayama et al., 2019), through the sequence of whole classroom activity. Only one operator was involved in these studies; however, this approach may not be practical when supporting classroom activities for an extended period. By contrast, in a previous study, we introduced avatar robots operated by multiple remote operators in rotation to assist whole classroom activities (Kawata et al., 2023). More specifically, an interactive robot participated in whole classroom activities for 3 days and interacted with children freely. Children did not show negative reactions to the avatar robot operated remotely by multiple individual operators rotationally. Nonetheless, the effects of introducing avatar robots into classrooms remain unclear. Intermittent implementation may not provide sufficient interaction between the avatar robot and the children to assess these consequences.

In this study, we expanded the settings of previous research (Kawata et al., 2023) to examine the effects of a long-term introduction of an avatar robot into an elementary school classroom. Specifically, when planning for the long-term deployment of an avatar robot, frequent changes in remote operators are expected. We implemented an information-sharing strategy to maintain consistent behavior and character across operators. We believe that this strategy could help reduce any communication inconsistencies that may arise with the children owing to shifts in remote operators. Additionally, we implemented group-focused communication strategies to ensure that each child in the class had equal interaction opportunities with the avatar robot. The avatar robot was continuously introduced to a class for fifth graders of the Mie University-affiliated elementary school for 9 days from 4 to 14 July 2022, excluding public holidays, to rotate classroom groups. In Japan, fifth graders are 10–11 years old. This class was chosen as a normal one in the public school. Three operators alternately operated the avatar robot. We assessed the impact on the children and the classroom before and after its introduction. The results suggest that daily and long-term interactions with an avatar robot not only provide children with comfortable recess and classes but also potentially encourage their participation in classroom activities. Based on these findings, we examined the character and behavior of the robot, including the appropriateness of the remote operator system. We discuss the potential for educational support using the avatar robot.

2 Related works

2.1 Educational support using telepresence robots

Telepresence robots are robotic devices that can be operated from a remote location. These robots incorporate video conferencing equipment (Kristoffersson et al., 2013). Specifically, telepresence robots have cameras, speakers, microphones, screens, and sensor-based motion control, enabling operators to log in and remotely control the robot from a tablet or PC. Operators can use the cameras on a device to access and monitor the local environment. Telepresence robots can be used to provide social interaction from a distance (Kristoffersson et al., 2013). Telepresence robots are being increasingly deployed in real-world educational settings to help children learn (Conti et al., 2017; Woo et al., 2021; Botev and Rodríguez Lera, 2021; Shimaya et al., 2019).

Telepresence robots in education have shown the potential to support children’s learning. Reportedly, students’ grades improved when a native English-speaking human teacher operated a robot to teach English to children from a remote location (Yun et al., 2011; Park et al., 2011). A teleoperated robot operated by an English teacher was introduced to language education and compared with a Skype interface (Tanaka et al., 2013). This suggested that the robot facilitates communication between the teacher and participants with potentially beneficial educational effects. By contrast, it has been shown that even if the remote operator is not an education specialist, the robot could make children interested in the class. Hashimoto et al. installed the Android SAYA in a classroom as a teacher, and one operator remotely operated the robot to conduct during a class. The approach piqued the children’s interest in science classes (Hashimoto et al., 2011). A teleoperated robot operated by Australian children was introduced to language education, and it was observed that Japanese students actively used English phrases to talk to the robot (Tanaka et al., 2013). However, these studies have primarily focused on providing learning support in specific subject areas, with less emphasis on activities that require long-term, continuous intervention, such as fostering interpersonal relationships within the classroom.

2.2 Supporting classroom activities

Teachers should make students participate in the learning process to optimize each student’s learning and development and to prevent gradual withdrawal, truancy, and dropout (Havik and Westergård, 2020). Additionally, positive interpersonal relationships between teachers and students positively impact learning, motivation, etc. (Xie and Derakhshan, 2021). In particular, positive attention (Frisby, 2019) and praise for student language use (Chalk and Bizo, 2004; Havik and Westergård, 2020) have been reported to be effective in promoting classroom participation behaviors. However, owing to teacher shortages, students may lack the support to actively participate in classroom activities (García and Weiss, 2019; Sutcher et al., 2019). Consequently, attempts have been made to support this need through technology. Among these, initiatives that promote the autonomy of children have been reported. For example, Nakanishi et al. introduced a small humanoid robot called Sota, which an older adult remotely controlled. It was shown that children began to talk about themselves spontaneously when the robot interacted with them in the morning and on their way home (Nakanishi et al., 2022). In another experiment, a teleoperated robot called Telenoid in an elementary school classroom for 2 days promoted communication among children, who showed more active attitudes toward group work (Yamazaki et al., 2012). Thus, the interaction of children with a robotic mediator during group work resulted in more active children. However, these studies were limited to support related to specific classroom activities, they did not address daily whole-class activities or full-day support for classroom activities comprising multiple participants and times. Studies demonstrated that providing children with comfortable breaks is crucial for aspects such as developing relationships and facilitating learning (Ramstetter et al., 2010; Bauml et al., 2020; Stapp and Karr, 2018). Furthermore, no study evaluated whether such support positively impacts classroom activities and children’s ability to socialize and communicate. Therefore, although technological interventions such as teleoperated robots are expected to enhance student engagement and participation in certain activities, it remains unclear how these technologies will support class and recess time on a daily basis.

3 Interactive avatar robot

3.1 Avatar robot system

Based on a previous study by Baba et al. (2020), multiple operators remotely controlled a social interactive humanoid robot called Sota using a teleoperation system called “Sota100” to achieve flexible communication with children and teachers. Sota100 has proven its performance and feasibility in various fields (Baba et al., 2020; Hatano et al., 2023; Song et al., 2021; Okafuji et al., 2024), including environments with children (Nakanishi et al., 2022), which indicates its design to be well accepted even in the classroom situation. The system configuration of the avatar robot used in this study is shown in Figure 1. The avatar robot Sota was developed by Vstone Corporation. Sota is a tabletop communication robot (280 mm (H)

Figure 1. Structure of an interactive teleoperation robotic system, based on a study by Baba et al. (2020). Using the voice changer, the audio output from the avatar robot remains consistent even when multiple remote operators are switched.

3.2 Interactive behaviors

Children had classes from the first period to the fifth period everyday. The avatar robots participated in classroom activities from the first recess after the first class to the long recess after the fourth class (9:30 a.m. to 1:25 p.m.); an operator was assigned to the first slot from the first recess (9:20 a.m.) to the end of the third class (11:30 a.m.). Subsequently, another was assigned to the second slot from the recess after the third class (11:30 a.m.) to the end of long recess after the fourth class (13:25 p.m.). Note that the robot avatar was tentatively suspended during the lunch and cleaning up time in the long recess. Each operator should log in to the control system 10 min before the start of their assigned slot, review the interaction history logs, and prepare for the upcoming interaction. The avatar robot was assigned the character “I am attending this class because I want to go to elementary school again” to give the children the impression that the avatar robot is motivated to participate in classroom activities. We did not disclose to the children that a human operator was remotely controlling the avatar robot. During classes, it spoke in response to requests from the children or the teacher. For example, the teacher sometimes requested it to respond by saying “what do you think about this opinion (of the children)?” and it praised or empathized by saying “I see, that’s one way of thinking!”, “I think so too!” or “I wish you would tell me more about it!” In the group work, the operators would call children’s names to solicit their opinions and encourage them to exchange opinions. Additionally, comments by the children were met with words of praise and nods of agreement (e.g., “What do you think, [name]?”, “You’ve expressed your opinion brilliantly!” or “Thank you for explaining that so clearly!”). During recess, basically, it did not only answer questions from the children but also freely asked the children various questions related to their school life, friendships, and understanding of the lessons. It sometimes offered to review any challenging parts when necessary. Furthermore, the operator occasionally asked other children to help involve those who had not spoken much with the avatar robot. When communicating with the children, the operator attempted to listen attentively without attacking or criticizing them, while protecting their privacy and avoiding comments that might impose gender roles or harassment. Note that its gaze direction was manually controlled by the operator in real time so as to look like it was directed to a child or the teacher. Its gestures were triggered to enhance its reactions, such as raising both hands and nodding.

3.3 Information sharing

Multiple operators were operating the robot; we needed to share information to avoid inconsistencies in communication. Inconsistencies might occur owing to differences in how each operator interacts with the children or owing to forgetting previous interactions. If the robot cannot maintain a consistent character, this could lead to distrust and confusion among children and hinder the goal achievement. Therefore, we used Google Forms and Google Spreadsheets. The operators recorded observations of the children’s actions and their responses during class. Ten minutes after the start of each class, 5 minutes were allocated for recording, inputting the collected information into Google Forms, and submitting it. These records were then submitted and reviewed by the next operator on a shared Google Spreadsheet before their session began, ensuring consistent communication and responses. This ensured consistency in information sharing and communication reactions among remote operators. This tool can share a log of interaction by all operators.

Additionally, real-time information sharing with the classroom teacher was facilitated through Slack. Slack, a group communication tool, supported interactions across devices, such as PCs and smartphones, enabling voice calls and file sharing. The classroom teacher uploaded images of the blackboard and textbook content to Slack, which remote operators used as references to participate in the lessons alongside the children.

4 Methods

4.1 Overview of the method

In this experiment, the interactive avatar robot “Sota” was installed in a fifth-grade elementary school classroom. The avatar robot, with three remote operators, participated in the class for 9 days, from 4 to 14 July 2022, excluding holidays. The remote operators interacted with the children and teachers via the robot. In addition, its position in the classroom was changed such that all groups comprising four children had equal chances of sitting next to it. During class, the avatar robot called out the names of the children to motivate them to share their opinions, responded to their ideas, and praised them. During recess time, the avatar robot focused on the members of the target group, which was situated beside it. The robot asked them about their understanding of the lesson, suggested that they review it, and encouraged conversation among the children. During lunch breaks, the robot engaged in free conversations with children from different groups, as they spontaneously gathered around the robot. These interactions explored whether the avatar robot provided comfort during recess time, encouraged the children to share their opinions and presentations during class, and supported their classroom activities. Moreover, we conducted a questionnaire survey to compare children’s sentiments regarding the avatar robot; the activities performed during recess time and in the classroom were also compared between the classes with and without the avatar robot, and the relationship between these factors was also examined. Furthermore, we used the Hyper-QU questionnaire (Musashi and Kawamura, 2015) to analyze changes in the classroom atmosphere and social skills of the children when the avatar robot was installed.

4.2 Participants

The participants of this study included 96 children in the fifth grade of an elementary school attached to a Mie University-affiliated elementary school. There were three fifth-grade classes, and Sota was installed in only one classroom, that is, class 5C (N = 32), which was considered the experimental group. Conversely, the other two classes without an avatar robot (classes 5A and 5B (N = 64)) were considered as the control group. Note that the children of class 5C participated in preliminary experiments before the main experiment (Kawata et al., 2023).

4.3 Apparatus

The avatar system described in 3.1 was utilized. The location of the avatar robot was changed daily to provide all the children with an opportunity to interact with the avatar robot. The remote operators used a laptop (Lenovo IdeaPad Core-i7 SSD 512GB) and a headset (Jabra 75 Evolve). Moreover, Morphvox (ScreamingBeeInc, 2024), a voice-changing software, was used to apply a ‘child’ effect to the voice of the operators, resulting in similar voice sounds for all the operators and ensuring a seamless transition between them.

4.4 Measurements

We used Kamide’s index to evaluate children’s sense of comfort and stress when spending time with the avatar robot, as well as their ability to interact with it—corresponding to (1) sense of wellbeing in the presence of the robot (Kamide et al., 2015). Subsequently, Kamide’s index was employed to assess the avatar robot’s personality and whether it exhibited consistent responses, aligning with (2) independent behavior of the robot (Kamide et al., 2016). Additionally, we created a questionnaire to determine whether the children felt comfortable during recess, which relates to (3) evaluation of comfort during recess time. Finally, we developed a questionnaire asking whether the children were comfortable giving presentations about the class time they spent with the avatar robot, corresponding to (4) evaluation of ease of presentation. The questionnaire is detailed in Table 1. Moreover, we investigated the effects of the avatar robot only for children in the class where the avatar robot was installed using the Hyper-QU questionnaire, which was used as a standardized classroom group assessment (Musashi and Kawamura, 2015).

4.4.1 Sense of wellbeing in the presence of the robot

This dimension assessed the sense of wellbeing experienced by the children in the presence of the robot in the classroom. The questionnaire was developed based on the sense of security scale used by Kamide et al. (2015). We chose the two items with the highest factor loadings in the different categories, including evaluations of “Comfort,” “Peace of Mind, ” “Performance,” and “Controllability.” Responses were collected on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”).

4.4.2 Independent of the robot

This dimension consisting of totally 10 items evaluated the perceptions regarding the character of the avatar robot. In this experiment, there is a possibility that children might perceive inconsistencies in the avatar robot’s behavior due to the fact that it was operated by multiple individuals with different personalities. Such inconsistency could lead to the impression that the robot did not have consistent awareness about itself. Therefore, we decided to ask the children directly about their perceptions of the robot’s self-consistency by using the following two question items: “This robot seems to have self-consistency” and “I infer the robot’s responses are consistent.” Similar to the previous dimension, a seven-point scale was used for responses. Additionally, potential self-inconsistency was considered to also reduce the impression of the robot’s anthropomorphism. Based on the previous research developing the Japanese version of psychological scales to evaluate anthropomorphism (Kamide et al., 2016), four sub factors for it, namely “Human Nature Positive,” “Human Nature Negative,” “Uniquely Human Positive,” and “Uniquely Human Negative.” Two question items with higher factor loding were chosen to assess each sub factor.

4.4.3 Comfort during recess

This category assessed whether children experienced comfort during recess and whether they experienced ease while engaging with their classmates. It comprised two questionnaire items: “I feel comfortable during recess” and “I find it easy to talk to my classmates during recess.” Responses were collected on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”).

4.4.4 Presenting in class

This dimension evaluated the ease of making presentations in four different scenarios during class. The questionnaire contains four items: “It is easy to make presentations for problems with clear answers,” “It is easy to make presentations for problems with unclear answers,” “It is easy to make presentations in small groups,” and “It is easy to present in front of the entire class.” Responses were collected using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”).

4.4.5 Total assessment in classroom

The impact of the avatar robot on the classroom was evaluated by adopting items from the Hyper-QU questionnaire developed by Musashi and Kawamura (2015), which measures the satisfaction of each child with school life, motivation for class activities, and social skills of the children. In particular, the questionnaire measured the extent to which children felt that their classmates and teachers approved of their presence and behavior (approval or disapproval), and evaluated their satisfaction with school life. Moreover, the questionnaire assessed the motivation of the children for class activities by measuring their motivation and satisfaction (friendship, motivation to learn, and class atmosphere). Furthermore, the social skills required for interpersonal relationships necessary for group formation were measured (consideration and interaction). Consideration indicates whether basic manners and rules were observed in adult interactions, while interaction indicates whether children were actively involved with their friends. We assessed the extent to which children mastered these social skills. These categories were used to provide a comprehensive study of the impact of avatars in the classroom environment.

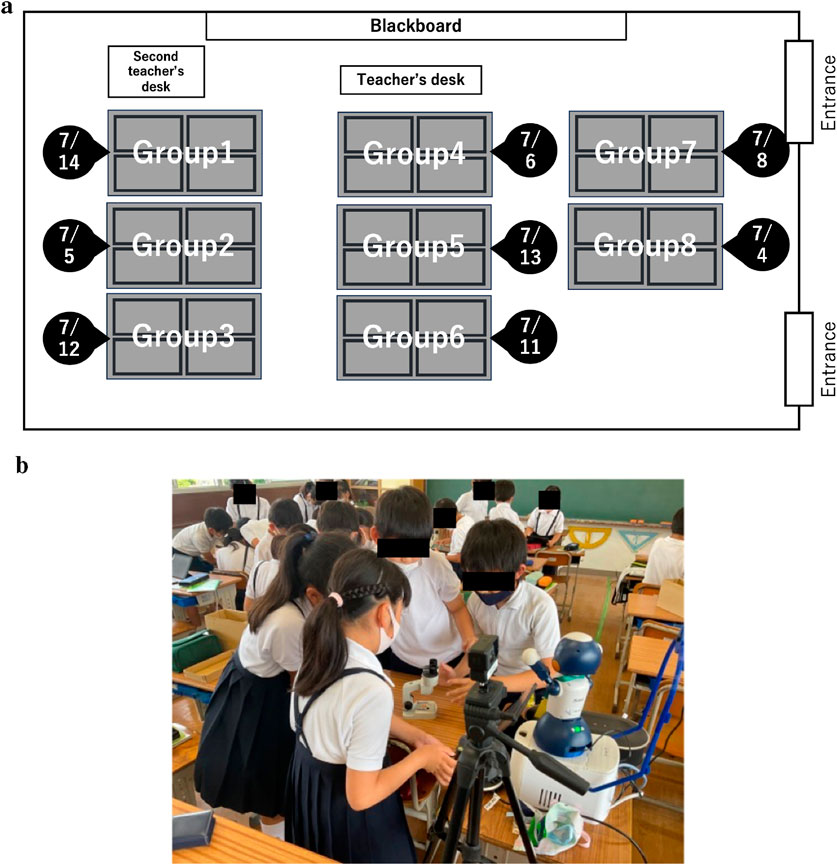

4.5 Procedure

The avatar robot “Sota” was placed on a specialized desk for children and moved to a different group each day for 9 days. The classroom arrangement for 5C is shown in Figure 2a. As shown in Figure 2b, Sota interacted closely with the children in their assigned groups during the class. Note that during recess and lunch breaks, children outside of the target group could also interact freely with the robot every day. On the fourth day, when class participation was low because of the use of other facilities in the school, Sota was placed on the desk of the teacher. Two remote operators were assigned each day to work in shifts during the first and second halves of the designated period. The remote operators comprised two staff members from Osaka University and one staff member from Nagasaki University. They used a remote-control interface from their respective laboratories to operate Sota. The avatar robot was operated only when the children used their home classroom for classes. The total number of times when it was operated in the class was 16 over nine days. To avoid disrupting the flow of the class, operators were instructed not to have the robot speak during the class and to refrain from initiating any utterances until called upon. On the other hand, it freely interacted with the children during recess. Three operators were randomly assigned to the slots for operating the avatar robot for 8, 5, and 3 periods, respectively. Slack was used as a tool to facilitate real-time communication between the classroom teacher and remote operators. The classroom teacher shared photos of the blackboard content and textbook material using Slack. The remote operators referred to information from the textbooks and handouts shared via Slack and participated in the class. The designated remote operator documented the communication that occurred between the teacher, children, and themselves using Google Forms and shared this information with the other remote operators. Questionnaires assessing the appropriateness of the avatar robot and examining the potential of the avatar robot to support education for both the experimental and control groups were administered on July 1st as a pretest and July 15th as a posttest. Moreover, the “HyperQU” survey to evaluate the impact on the classroom was administered only to the experimental group on 1st July as a pretest and on 15th July as a posttest. Additionally, on 15th July, the experimental group provided free descriptive answers regarding their impression of their two-week-long interactions with the robot. Following the questionnaire, we observed the discussion on “how to interact with the robot” in the moral class for the children of the experimental group.

Figure 2. (a) Schedule of the movement of the avatar for 2 weeks. (b) Interaction between the avatar and children of Group 5 during class. (a) This figure shows the schedule and movement of the avatar over 2 weeks. The classroom is divided into eight groups, with the numbers in black balloons indicating the dates the avatar was positioned in each group. (b) This image shows children interacting with the avatar robot. This image was taken during a science class and shows children of Group 5, explaining the microscope to the avatar robot.

5 Results

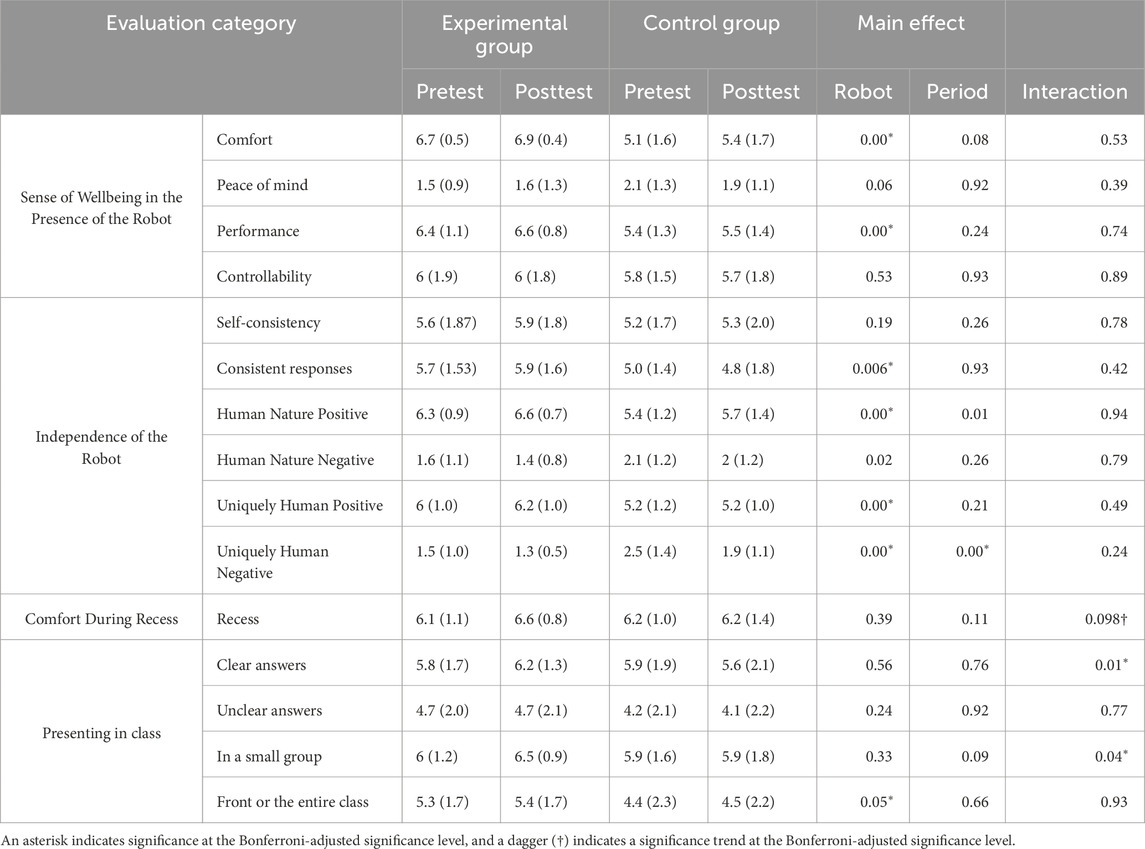

We used a mixed-design two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a variable of the period (pretest/posttest) as the within-subject factor and a variable of the robot (with/without) as the between-subject factor when analyzing the measurements in the four categories. We analyzed the questionnaire responses of 30 children in the experimental group and 44 children in the control group who answered both pretest and posttest for the different categories, such as their sense of wellbeing in the presence of the robot, independence of the robot, comfort during recess time, and ease of presentation. Table 2 presents the test results for the main effects and interactions for each question. We conducted paired t-tests to analyze the differences between the two time points, that is, 1st July (pretest) and 15th July (posttest), concerning the classroom with the avatar. The analysis aimed to assess the school life motivation scale for the subscales of friendship, learning motivation, classroom atmosphere, school life satisfaction related to approval/disapproval of their classmates, and social skills based on consideration and interaction. We analyzed 29 children from a total of 34 children in the experimental group who responded to both the pretest and posttest assessments.

Table 2. Mean (standard deviation) of scales related to the following questionnaire items: sense of wellbeing in the presence of the robot, independence of the robot, comfort during recess, ease of presenting.

5.1 Sense of wellbeing in the presence of the robot

For each measurement, the mixed-design ANOVA was conducted with the adjusted significance level as per the Bonferroni method (

5.2 Independence of the robot

For each measurement, the mixed-design ANOVA was conducted with the adjusted significance level according to the Bonferroni method (

5.3 Comfort during recess

We combined the results of the two questions related to the recess and analyzed them using a mixed-design ANOVA. The robot (F (1,72) = 0.761,

5.4 Presenting in class

The category of ease of presentation consisted of four different questions related to different situations. For questions related to clear answers for ease of presentation, a significant interaction was observed (F (1,72) = 7.142,

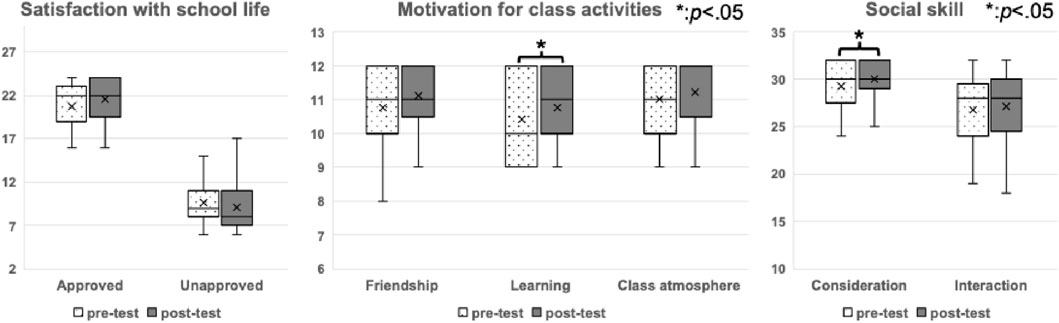

5.5 Total assessment in classroom

Regarding learning motivation, a significant difference was observed between the means of both levels (t = 2.167,

Figure 3. Results for the categories of satisfaction with school life, motivation for class life, and social skill according to Hyper-QU. The results are summarized in Panel 3 for the 29 children of the experimental group, who responded to both the pretest and posttest assessments.

6 Discussion

6.1 Characterization and behavior of the avatar

First, the results of this research show that after 9 days of interaction, the children in the classroom with the avatar robot felt it easier to present questions for which children knew that the answers were clear. Moreover, they indicated that the children felt more comfortable presenting in front of small groups. Additionally, learning motivation was increased. The strategies adopted for the avatar’s behavior, which included calling out children by name, encouraging the expression of personal opinions, and praising presenters, are likely to have encouraged children to learn through active class participation. In other words, the implemented avatar robot was able to be operated by multiple operators and could effectively support children’s classroom activities, as intended to be checked in this experiment. We found consistent positive comments on the perceived impact of the avatar robot on their classes in free descriptive feedback from the children, such as, “Having the robot in my group made it easier for me to participate more in the class,” “Having the robot made it easier to present during the class,” and “Having the robot in class boosts the classmates’ motivation to learn, making it more enjoyable.” They are consistent with related studies showing that introducing an avatar robot into a community of children made children more active (Yamazaki et al., 2012).

Second, the results show that interactions with the avatar robot enabled children to spend their recess time more comfortably, and it seemed to promote easier communication with their classmates. During recess time, the adopted strategy for interaction involved free conversations with children on various topics, such as classroom atmosphere, friendship, and school life. Such interactions are considered to provide comfort to children during recess time. The manner in which the avatar mediated the interactions between children was also observed during recess time, suggesting the potential role of the avatar in promoting interpersonal interactions. The children provided consistent answers in the free description of their impression of their time with the avatar. For example, “ the presence of the avatar robot contributed to a more enjoyable recess and promoted conversations with their peers.” Specifically, they commented, “It’s helpful to have the robot as a playmate during recess” and “After spending time with the robot, I found it easier to talk a lot with my classmates, and we became closer.” It has been suggested that comfortable recess time is crucial for building relationships and facilitating learning (Ramstetter et al., 2010). Therefore, the avatar robot is considered to contribute to providing children with a comfortable recess time that encourages interaction among them.

Finally, the consideration skill, indicating self-evaluation of one’s considerable attitude toward others, was improved in the classrooms where the avatar robot was installed. Considering that the avatar consistently exhibited considerate behavior toward children throughout the experimental period, this suggests the possibility that the avatar robot could serve as a positive role model for children. We found consistent answers in the free description that indicated children’s impressions, for example, “I want to learn from the robot and get better at saying ’thank you”’ and “I admire the robot’s reactions.” In addition, a child in the moral class who viewed the robot’s behavior positively had the following opinion: “The robot always responds to our presentations and interactions; we should adopt its behavior as well.” The results imply the necessity to carefully design the avatar’s characteristics to avoid unexpectedly influencing children’s behavior.

6.2 Teleoperator system

In the experiment, children in the classroom with the avatar robot reported a greater sense of comfort and perceived the robot as more helpful for their wellbeing. They also felt that the robot acted more independently. At the same time, there was no clear decreasing trend observed. Although the results do not suggest that having multiple operators harmed the children’s positive impression of the robot, we did not gain clear practical insights into which specific robot behaviors are most desirable for gaining children’s acceptance. Therefore, it would be valuable to conduct additional experiments with longer intervention periods in different classroom settings to see if similar results are observed. During this period, the proposed methods for remote operators to preshare dialogue content and information enabled avatar robots to maintain consistent speech and behavior. This facilitated seamless communication with children without causing severe discomfort. Thus, the children may not have noticed the switching of remote operators. Therefore, the practical feasibility of rotationally operating avatar robots by multiple individuals was demonstrated. Additionally, no comments were received from the children expressing any discomfort toward the avatar robot. By interacting with children remotely and providing consistent support and communication, avatar robots have demonstrated the potential to help students maintain positive relationships without causing stress, as intended to be checked in this experiment. Avatar robots, such as Sota (Nakanishi et al., 2022) and Telenoid (Yamazaki et al., 2012), shown promising outcomes in enhancing children’s communication and participation. Previous studies have been limited to specific classes or short-term experiments; however, our system enabled the robot to participate in whole classroom activities alongside students over an extended period, demonstrating the feasibility of providing continuous attention and support in the classroom. This study also highlights the potential for nonteacher operators to teleoperate with avatar robots while maintaining consistent behavior and avoiding negative reactions from students. The results suggest that this approach can effectively support children’s learning and school education.

In this study, we conducted an experiment in which an avatar robot was operated by multiple operators taking turns to provide all-day support. The results demonstrated that avatar robots can support children’s learning and social interaction even when operated in shifts by different individuals. This finding suggests that, in real-world implementations where it is difficult to ensure a single operator’s continuous involvement, adopting a multi-operator approach may be a viable solution. At the same time, while our study focused on confirming the feasibility of multi-operator use, it was not designed to directly compare avatar robots operated by a single individual with those operated by multiple people. Nevertheless, examining the potential advantages and disadvantages of multi-operator control is an important issue. We believe that confirming the feasibility of multi-operator support in this study lays the groundwork for future empirical investigations from this perspective. Furthermore, leveraging the resources of the local community to operate avatar robots provides a solution for addressing teacher shortages and expanding educational support systems.

6.3 Limitations and future works

In this study, children only in Class 5C had prior exposure to the robot before the experiment, which might promote children to be accustomed to it and influence their responses. However, the current study was not intended to separate the potential effect of the prior exposure from other effects. Furthermore, the length of the prior exposure to the avatar robot might influence how much it was accustomed to the children and positively evaluated. Therefore, the future work should adequately investigate this issue.

In the Discussion, we suggested the potential for the avatar robot to be perceived as a positive role model by children. However, the present study did not incorporate methods that allow for an in-depth analysis of children’s psychological responses related to role modeling. This limitation reflects the absence of psychological assessment tools in the study design. Future research should address this gap by exploring children’s internal responses in greater detail through interviews, behavioral observations, and the use of validated psychological scales.

Since this study was conducted with fifth-grade students in a Japanese elementary school, the generalizability of the findings to other age groups or cultural contexts remains limited. Children’s responses to avatar robots may vary depending on developmental stage and cultural background. To address this limitation, future research should expand the scope of investigation by conducting studies with students of different age groups and in diverse cultural or institutional settings. Such studies would help evaluate the adaptability of the system and identify necessary modifications for implementation in varied contexts—for example, simplified user interfaces, systems for receiving input from teachers, and alignment with local classroom practices and curricula. Furthermore, to address the shortage of teachers, it is necessary to reveal the technical challenges that may arise when people from various backgrounds and characteristics, such as expertise, genders, ages, traits, and handicaps/gifts, operate the system. However, the current results are limited to an experimental setting with a small number of operators—specifically, three females without expertise in education. This limitation makes it challenging to demonstrate that the proposed method functions in a manner that potential citizen confederates from a wide range of backgrounds can effectively assist teachers in providing rich education support to children.

Finally, we plan to enhance the avatar robot design by adding features that will allow for personalized interaction, such as recognizing individual students, remembering conversations and summarizing the history of the dialogue. The introduction of such features is expected to enhance support for children in diverse learning environments (Baxter et al., 2017). We believe integrating the avatar robot with other teaching tools will provide a clearer understanding of children’s learning progress, enabling more appropriate and responsive educational support. Furthermore, as Papakostas et al. (2021) has shown such personalization and integration improvements will contribute to a more flexible avatar design potentially beneficial for students with special needs whose requests are not adequately addressed by the current support system (Papakostas et al., 2021). In addition, we will consider different types of teleoperators, such as older adults interested in contributing to education and professional counselors with expertise in helping children with special needs, to explore the potential of the proposed methodology to promote attentive educational support throughout the community.

7 Conclusion

In this study, we reported a field experiment concerning questions for an application of an avatar robot on the school-community collaboration by introducing Sota100 to a classroom of an elementary school concerning two questions: “whether an avatar robot can be effectively operated by multiple remote operators to support children’s classroom activities” and “whether switching between multiple operators would negatively affect children’s perception of the avatar robot”. It was introduced with an information sharing method to maintain consistent communication with children despite changes in operators. Namely, this study expanded upon the setup of a previous study (Kawata et al., 2023) by introducing avatars operated by three operators in turns for 9 days, from 4 July 2022 to 14 July 2022, excluding holidays. The test was conducted in a fifth-grade class at a Mie University-affiliated elementary school. The field study conducted at elementary schools suggested that the continuous and daily use of an avatar robot, which actively engaged in the classroom by calling out names of children, encouraging their opinions, praising presenters, and freely interacting with children during recess time, could effectively provide comfortable classes and recess time for children. Additionally, it showed an improvement in their motivation to learn and communicate in the classroom with the avatar robot. Furthermore, the policy of listening to children without criticism may have led to a ripple effect, improving their consideration skills, possibly because the children perceived the avatar robot as a normative entity. Notably, the findings suggest that the children did not develop negative impressions of the avatar robot, even if an avatar robot with multiple remote operators is introduced to participate in whole classroom activities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the possibility that multiple people can take turns operating an avatar robot to participate alongside the children in the classroom activities without causing them any strong negative reactions, and that the avatar robot can support the children’s class activities. This may be because the multiple remote operators could maintain consistent statements and behaviors of the avatar by incorporating a method in which they obtained information about the children and shared the information along with the history of dialogues with each other in advance. The results suggest that multiple nonteacher operators can teleoperate with the avatar robot, which could support children’s school life by creating an atmosphere wherein children feel comfortable expressing their opinions in class and providing a comfortable recess time. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged regarding the scope of the present study. This study was conducted using one classroom and one avatar robot in a specific culture and educational context. While positive effects were observed in supporting children’s learning and classroom participation, it remains unclear whether similar results would be achieved in other environments or with different types of robots. Further field studies in different locations and countries are needed to validate the generalizability of the method.

In the future, we aim to explore the potential of our proposed method to facilitate community-wide, attentive educational support. This involves considering various types of remote operators, including older adults who may be interested in contributing to education and professional counselors with expertise to assist children with special needs. In addition, we plan to improve the avatar robot by adding features for personalized interaction and integration with teaching tools, aiming to better support diverse learners. These enhancements could benefit students with special needs by enabling more flexible avatar designs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Mie University Faculty of Education Research Promotion Committee (Reference No. 2021-11). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review and editing. HKu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. HKa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. JB: Writing – review and editing, Software. NM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review and editing. HI: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. YY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the JST Moonshot R&D Grant No. JPMJPS2011 (for development of base system), JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. JP20H00101 (for experiment), 22K17977 (for character design of the avatar), and JST-MiraiProgram Grant No. JPMJMI22J3 (for discussion on moral lesson).

Conflict of interest

Author JB was employed by CyberAgent, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baba, J., Sichao, S., Nakanishi, J., Kuramoto, I., Ogawa, K., Yoshikawa, Y., et al. (2020). “Teleoperated robot acting autonomous for better customer satisfaction,” in Extended abstracts of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–8.

Bauml, M., Patton, M. M., and Rhea, D. (2020). A qualitative study of teachers’ perceptions of increased recess time on teaching, learning, and behavior. J. Res. Child. Educ. 34, 506–520. doi:10.1080/02568543.2020.1718808

Baxter, P., Ashurst, E., Read, R., Kennedy, J., and Belpaeme, T. (2017). Robot education peers in a situated primary school study: personalisation promotes child learning. PloS one 12, e0178126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178126

Belpaeme, T., Baxter, P., De Greeff, J., Kennedy, J., Read, R., Looije, R., et al. (2013). “Child-robot interaction: perspectives and challenges,” in Social robotics: 5th international conference, ICSR 2013, bristol, UK, october 27-29, 2013, proceedings 5 (Springer), 452–459.

Botev, J., and Rodríguez Lera, F. J. (2021). Immersive robotic telepresence for remote educational scenarios. Sustainability 13, 4717. doi:10.3390/su13094717

Canedo-Garcia, A., Garcia-Sanchez, J.-N., and Pacheco-Sanz, D.-I. (2017). A systematic review of the effectiveness of intergenerational programs. Front. Psychol. 8, 1882. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01882

Chalk, K., and Bizo, L. A. (2004). Specific praise improves on-task behaviour and numeracy enjoyment: a study of year four pupils engaged in the numeracy hour. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 20, 335–351. doi:10.1080/0266736042000314277

Conti, D., Di Nuovo, S., Buono, S., and Di Nuovo, A. (2017). Robots in education and care of children with developmental disabilities: a study on acceptance by experienced and future professionals. Int. J. Soc. Robotics 9, 51–62. doi:10.1007/s12369-016-0359-6

Frisby, B. N. (2019). The influence of emotional contagion on student perceptions of instructor rapport, emotional support, emotion work, valence, and cognitive learning. Commun. Stud. 70, 492–506. doi:10.1080/10510974.2019.1622584

Galbraith, B., Larkin, H., Moorhouse, A., and Oomen, T. (2015). Intergenerational programs for persons with dementia: a scoping review. J. Gerontological Soc. Work 58, 357–378. doi:10.1080/01634372.2015.1008166

García, E., and Weiss, E. (2019). Us schools struggle to hire and retain teachers. the second report in” the perfect storm in the teacher labor market” series. Economic policy institute.

Giraudeau, C., and Bailly, N. (2019). Intergenerational programs: what can school-age children and older people expect from them? a systematic review. Eur. J. ageing 16, 363–376. doi:10.1007/s10433-018-00497-4

Han, S. W., Borgonovi, F., and Guerriero, S. (2018). What motivates high school students to want to be teachers? the role of salary, working conditions, and societal evaluations about occupations in a comparative perspective. Am. Educ. Res. J. 55, 3–39. doi:10.3102/0002831217729875

Hashimoto, T., Kobayashi, H., and Kato, N. (2011). “Educational system with the android robot saya and field trial,” in 2011 IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems (FUZZ-IEEE 2011) (IEEE), 766–771.

Hatano, Y., Baba, J., Nakanishi, J., Yoshikawa, Y., and Ishiguro, H. (2023). “Exploring the recommendation expressions of multiple robots towards single-operator-multiple-robots teleoperation,” in International conference on human-computer interaction (Springer), 46–60.

Havik, T., and Westergård, E. (2020). Do teachers matter? students’ perceptions of classroom interactions and student engagement. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 64, 488–507. doi:10.1080/00313831.2019.1577754

Hodges, V. C., Centeio, E. E., and Morgan, C. F. (2022). The benefits of school recess: a systematic review. J. Sch. Health 92, 959–967. doi:10.1111/josh.13230

Ingersoll, R. M., and Smith, T. M. (2003). The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educ. Leadersh. 60, 30–33. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/34868.

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., and May, H. (2016). Do accountability policies push teachers out? Educ. Leadersh. 73, 44–49. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/35328.

Ishiguro, H. (2021). The realisation of an avatar-symbiotic society where everyone can perform active roles without constraint. Adv. Robot. 35, 650–656. doi:10.1080/01691864.2021.1928548

Kamide, H., Kawabe, K., Shigemi, S., and Arai, T. (2015). Anshin as a concept of subjective well-being between humans and robots in Japan. Adv. Robot. 29, 1624–1636. doi:10.1080/01691864.2015.1079503

Kamide, H., Kazuki, T., and Arai, T. (2016). Creation of a Japanese version of the anthropomorphic scale(Japanese). Personality Res. 25, 218–225. doi:10.2132/personality.25.218

Kanda, T., Sato, R., Saiwaki, N., and Ishiguro, H. (2007). A two-month field trial in an elementary school for long-term human–robot interaction. IEEE Trans. robotics 23, 962–971. doi:10.1109/tro.2007.904904

Kasuk, T., and Virkus, S. (2024). Exploring the power of telepresence: enhancing education through telepresence robots. Inf. Learn. Sci. 125, 109–137. doi:10.1108/ils-07-2023-0093

Kawata, M., Maeda, M., Yoshikawa, Y., Kumazaki, H., Kamide, H., Baba, J., et al. (2023). “Preliminary investigation of the acceptance of a teleoperated interactive robot participating in a classroom by 5th grade students,” in Social robotics: 14th international conference, ICSR 2022, florence, Italy, december 13–16, 2022, proceedings, Part II (Springer), 194–203.

Komatsubara, T., Shiomi, M., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., and Hagita, N. (2015). A robot in a science room to help understanding of science class. J. Robotics Soc. Jpn. 33, 789–799. doi:10.7210/jrsj.33.789

Kristoffersson, A., Coradeschi, S., and Loutfi, A. (2013). “A review of mobile robotic telepresence,” in Advances in human-computer interaction 2013.

Ministry of Education and Culture and Sports and Science and Technology (2022). Fact-finding survey on “teacher shortage”(Japanese). Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/kyoin/mext_00003.html.

Ministry of Education and Culture and Sports and Science and Technology Report of the Central Council for Education (2015). Regarding the state of cooperation and collaboration between schools and local communities to realize education in the new era and regional revitalization, and future promotion measures (report)(Japanese). Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo0/toushin/1365761.htm.

Murayama, Y., Murayama, H., Hasebe, M., Yamaguchi, J., and Fujiwara, Y. (2019). The impact of intergenerational programs on social capital in Japan: a randomized population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public health 19, 156–159. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6480-3

Musashi, Y., and Kawamura, S. (2015). Atmosphere in classrooms and elementary school children’s motivation for classes and their social skills(Japanese). Jpn. J. Classr. Manag. Psychol. 4, 29–37. doi:10.34318/jacmp.4.0_29

Nakanishi, J., Hazama, T., Baba, J., Song, S., Yoshikawa, Y., and Ishiguro, H. (2021). “Exploring possibilities of social robot’s interactive services in the case of a hotel room,” in 2021 30th IEEE international conference on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN) (IEEE), 925–930.

Nakanishi, J., Baba, J., and Ishiguro, H. (2022). “Robot-mediated interaction between children and older adults: a pilot study for greeting tasks in nursery schools,” in 2022 17th ACM/IEEE international Conference on human-robot interaction (HRI) (IEEE), 63–70.

Newman, S., and Hatton-Yeo, A. (2008). Intergenerational learning and the contributions of older people. Ageing horizons. 8, 31–39. Available online at: https://www.ageing.ox.ac.uk/files/ageing_horizons_8_newmanetal_ll.pdf.

Okafuji, Y., Ishikawa, T., Matsumura, K., Baba, J., and Nakanishi, J. (2024). Pseudo-eating behavior of service robot to improve the trustworthiness of product recommendations. Adv. Robot. 38, 343–356. doi:10.1080/01691864.2024.2321191

[Dataset] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020). Pisa 2018, results: students and money (volume vi)effective policies, successful schools. doi:10.1787/ca768d40-en

Papakostas, G. A., Sidiropoulos, G. K., Papadopoulou, C. I., Vrochidou, E., Kaburlasos, V. G., Papadopoulou, M. T., et al. (2021). Social robots in special education: a systematic review. Electronics 10, 1398. doi:10.3390/electronics10121398

Park, S. J., Han, J. H., Kang, B. H., and Shin, K. C. (2011). “Teaching assistant robot, robosem, in English class and practical issues for its diffusion,” in Advanced robotics and its social impacts (IEEE), 8–11.

Perryman, J., and Calvert, G. (2020). What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? accountability, performativity and teacher retention. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 68, 3–23. doi:10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417

Ramstetter, C. L., Murray, R., and Garner, A. S. (2010). The crucial role of recess in schools. J. Sch. Health 80, 517–526. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00537.x

Software ScreamingBeeInc (2024). Morphvox pro. Available online at: https://screamingbee.com/morphvox-voice-changer.

Shimaya, J., Yoshikawa, Y., Kumazaki, H., Matsumoto, Y., Miyao, M., and Ishiguro, H. (2019). Communication support via a tele-operated robot for easier talking: case/laboratory study of individuals with/without autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Soc. Robotics 11, 171–184. doi:10.1007/s12369-018-0497-0

Shimojo, M. (2020). Current state and issues of community schools for solving educational issues; possibility of using educational resources in local communities (Japanese). J. Incl. Educ. 8, 67–81. doi:10.20744/incleedu.8.0_67

Song, S., Baba, J., Nakanishi, J., Yoshikawa, Y., and Ishiguro, H. (2021). Teleoperated robot sells toothbrush in a shopping mall: a field study. Ext. Abstr. 2021 CHI Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst., 1–6. doi:10.1145/3411763.3451754

Stapp, A. C., and Karr, J. K. (2018). Effect of recess on fifth grade students’ time on-task in an elementary classroom. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 10, 449–456. doi:10.26822/iejee.2018438135

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., and Carver-Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: an analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Educ. policy Anal. Arch. 27, 35. doi:10.14507/epaa.27.3696

Tanaka, F., Takahashi, T., Matsuzoe, S., Tazawa, N., and Morita, M. (2013). “Child-operated telepresence robot: a field trial connecting classrooms between Australia and Japan,” in 2013 IEEE/RSJ international Conference on intelligent Robots and systems (IEEE), 5896–5901.

Wiggan, G., Smith, D., and Watson-Vandiver, M. J. (2021). The national teacher shortage, urban education and the cognitive sociology of labor. Urban Rev. 53, 43–75. doi:10.1007/s11256-020-00565-z

Woo, H., LeTendre, G. K., Pham-Shouse, T., and Xiong, Y. (2021). The use of social robots in classrooms: a review of field-based studies. Educ. Res. Rev. 33, 100388. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100388

Xie, F., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Front. Psychol. 12, 708490. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490

Yamazaki, R., Nishio, S., Ogawa, K., Ishiguro, H., Matsumura, K., Koda, K., et al. (2012). How does telenoid affect the communication between children in classroom setting? CHI’12 Ext. Abstr. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst., 351–366. doi:10.1145/2212776.2212814

Yoshida, T., and Yoshizawa, H. (2024). Changes in perceptions of residents, parents, and teachers towards schoolcommunity cooperation (Japanese). Jpn. J. Appl. Psychol. 50, 141–150. doi:10.24651/oushinken.50.2_141

Keywords: encouraging classroom activities, remote-controlled avatar, multiple operators, field trial, educational support

Citation: Kawata M, Maeda M, Kumazaki H, Kamide H, Baba J, Matsuura N, Ishiguro H and Yoshikawa Y (2025) Encouraging classroom activities for children using avatar robots: a field trial. Front. Robot. AI 12:1571804. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2025.1571804

Received: 06 February 2025; Accepted: 13 August 2025;

Published: 09 September 2025.

Edited by:

Paitoon Pimdee, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, ThailandReviewed by:

Abdul Aziz Saefudin, PGRI University of Yogyakarta, IndonesiaAlam Rahmatulloh, Siliwangi University, Indonesia

Marianus Tapung, Santu Paulus Indonesian Catholic University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Kawata, Maeda, Kumazaki, Kamide, Baba, Matsuura, Ishiguro and Yoshikawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Megumi Kawata, a2F3YXRhLm1lZ3VtaS5lc0Bvc2FrYS11LmFjLmpw

Megumi Kawata

Megumi Kawata Masashi Maeda2

Masashi Maeda2 Hirokazu Kumazaki

Hirokazu Kumazaki Hiroko Kamide

Hiroko Kamide Jun Baba

Jun Baba Hiroshi Ishiguro

Hiroshi Ishiguro Yuichiro Yoshikawa

Yuichiro Yoshikawa