- Department of Anthropology, College of Liberal Arts, University of Texas, Austin, TX, United States

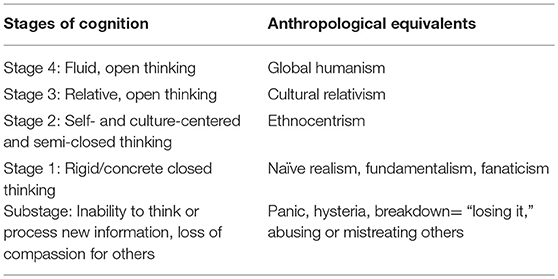

This conceptual “think piece” looks at levels or Stages of Cognition, equating each of the Four Stages I examine with an anthropological concept. I equate Stage 1—rigid or concrete thinking—with naïve realism (“our way is the only way”), fundamentalism (“our way should be the only way and those who do not follow it are doomed”), and fanaticism (“our way is so right that everyone who disagrees with it should be either converted or eliminated”). I equate Stage 2 with ethnocentrism (“there are lots of other ways out there, but our way is best”). The next two Stages represent more fluid types of thinking—I equate Stage 3 with cultural relativism (“all ways are equal in value and validity”), and Stage 4 with global humanism (“there must be higher, better ways that can support cultural integrity while also supporting the individual rights of each human being”). I then categorize various types of birth practitioners within these 4 Stages, while showing how ongoing stress can cause even the most fluid of thinkers to shut down cognitively and operate at a Stage 1 level that can involve obstetric violence—an example of further degeneration into Substage—a condition of panic, burnout or “losing it.” I note how ritual can help practitioners ground themselves at least at a Stage 1 level and offer ways in which they can rejuvenate and re-inspire themselves. I also describe a few of the ongoing battles between fundamentalists and global humanists and the persecution that Stage 4 globally humanistic birth practitioners often experience from fundamentalist or fanatical Stage 1 practitioners and officials, often referred to as the “global witch hunt.”

Much of my anthropological work on childbirth, midwifery, and obstetrics has focused on knowledge systems—ways of knowing about birth (Davis-Floyd, 1992/2003; Davis-Floyd and Sargent, 1997; Davis-Floyd et al., 2018), as does my current work in progress, Birth in Eight Cultures (Davis-Floyd and Cheyney in press). Sections of this book describe “the global technocratic model of birth” and how it is enacted through “standard obstetric procedures,” which I have long analyzed as rituals that enact and display the core values of the technocracy, which, I have argued, supervalues progress via the development of ever-higher technologies, the global flow of information via such technologies, the ongoing dissemination of patriarchy, and the centrality of institutions and capitalism (Davis-Floyd, 1992/2003, 2018a,b). The core section of Birth in Eight Cultures contains specific ethnographic examinations of vast dissimilarities in cultural conceptualizations and management of birth: the chapters show that, on a scale ranging from most to least in descending order, facility births in Greece, Brazil, Mexico, Tanzania, and the U.S. are highly industrialized and technocratic, with cesarean rates ranging from 65% (Greece) to 32% (US). On the more humanistic side of the global spectrum, we find New Zealand (CS 25%), Japan (19%), and the Netherlands (16%). In those countries, conceptions of the body, the meaning of labor and birth, and the predominant care of skilled midwives work to treat birth more in keeping with scientific evidence about birth physiology and to ensure that women are the protagonists of their own births. All our ethnographic chapters show that midwifery autonomy coupled with egalitarian physician collaboration is the key to midwives' ability to truly practice the midwifery model of care, rather than succumbing to the pressures of the global technocratic approach—which influences care almost everywhere, superceding cultural differences.

This book has thus served to illustrate Jordan's insight that “birth is everywhere culturally marked and shaped” and that “science” in general is just another culturally influenced system that can range from being marked and shaped to “prove” that the cultural birth model of any nation is right and appropriate—or can be used to show us truly how best to facilitate the normal physiologic, emotional, and spiritual process of parturition. Given that some cultural birthing systems are full of obstetric violence (like those of Brazil and Mexico) and cause a great deal of harm to women and babies, it can be puzzling that those systems are often consensually constructed by pregnant women and their caregivers. For examples, in Greece, many culturally-influenced women believe that cesareans are safer and better for babies and for their own bodies, despite the preponderance of scientific evidence clearly showing that they are not, while in the Netherlands the low CS rate seems due to the strong cultural belief that birth is a normal process in little need of intervention. Over 60% of US women insist on epidurals (no matter how many other interventions they entail nor the increased risk of CS that accompanies them), because many US women fear and see no value in suffering through labor pain. Yet only around 6% of Japanese women choose epidurals, because they see labor pain as worthwhile, often coding it as “metamorphic”—an essential formative part of the process of becoming a mother. Given such stark cultural contrasts, how then can we find ways to care for parturient women that do not try to destroy local cultural systems, yet do work to make them better for mothers, babies, and families using the resources (often scarce) that they have? Many countries have strong birth activist movements that seek to accomplish that goal, yet are usually met with so much resistance to change that they often make little headway.

Ways of Thinking and Knowing: Open and Closed Systems

Making birth better globally would entail an end to all types of obstetric violence and violations of women's rights during parturition, and would also incorporate educating women everywhere about their rights and about how to facilitate the normal physiology of birth, so that they can make truly informed (not just culturally or obstetrically informed) choices. Since, as has often been shown, many obstetricians don't fully understand how to facilitate truly normal birth with no interventions (because they rarely ever see it), I think we need to take a good hard look at how people think, and, having done that, to use those insights to inquire how best to change ways of thinking that need to change, and to reinforce those that don't.

Thus here I take a broad look at ways of thinking and knowing—of cognizing—the world around us. I focus specifically on the differences between two types of knowledge systems—those that are relatively open and those that are relatively closed. Why? Because the adherents of any knowledge system who wish that system to remain responsive to changing events in a rapidly changing world must remain open to absorbing new information and adapting themselves to that new information. You can't change your paradigm, knowledge system, or belief system without being open to changing it, which entails admitting that it has limitations and flaws—something many people locked into a rigid belief system/worldview are generally unwilling to do. If you are already sure you have all the answers, why look beyond in search of better ones? To achieve an open knowledge system, the kind that is most fitting for this fluid world and that is also essential to achieve better births—births that are safe, physiologic, and woman-centered—one must first understand what it means for a knowledge system to be “closed.”

Relatively Closed Knowledge Systems: Stages 1 and 2

Stage 1 Thinking: Naïve Realism, Fundamentalism, Fanaticism

If a child grows up in one culture and is exposed for the first 20 or so years of its life only to the rhythms, patterns, language and belief system of that culture, its neural networks will become set in those terms. After that, learning a new language or internalizing the norms and values of a different culture or belief system becomes increasingly difficult over time, because integrating new information always requires the formation of entirely new neural pathways in the brain. For a child whose brain is still developing, forming millions of new neural networks every day, that process is effortless; for adults whose neural structures are already largely set, that process requires enormous amounts of time, energy and concentrated effort to create new bridges across the synaptic gaps between what they already know and what they desire to learn. If you have tried to learn a new language later in life, you will know exactly what I mean.

Individuals who are never required to “think beyond” the belief systems of the cultures or subcultures in which they are raised can over time become resistant to processing new information and can become neurocognitively “rigid” or “concrete” in their thinking—placing them in the cognitive arena of what some brain theorists have called Stage 1 thinking.1 For Stage 1 thinkers, there is only one possible set of interpretations of reality, and that set of interpretations is reality; their knowledge system is closed. I link such systems, firstly, to what anthropologists term naïve realism—the notion that “our way is the only way there is.” For example, many members of small-scale societies, before their massive exposure to Western culture, were naïve realists. (I must stress that I am not taking any sort of evolutionary perspective here—I reject any notion that naïve realists are less intelligent than others and that the rest of us have “evolved” beyond naïve realism. Both rigid and fluid thinkers exist in every type of society. It not intelligence, but one's degree of socialization and exposure—or lack thereof—to other ways of thinking that has the greatest effect on how deeply individuals will internalize the core values of their society.)

Throughout much of human history, many types of religious and political Stage 1 thinkers, first called “true believers” by Eric Hoffer (1951), have gone beyond naïve realism to fundamentalism—they know there are many other ways of thinking out there, but are completely convinced and certain that their way of knowing is right and is (or should be) “the only way” for everyone. Most fundamentalists who live in such closed conceptual systems try hard to shut out all conflicting information, especially from their children, whom they seek to raise as naïve realists, often by not allowing them to watch television, read books, or attend schools that do not confirm their parents' belief system, worldview, and/or religion's tenets. Fundamentalists usually do not harm others or try to coerce them into accepting their version of reality—rather, they generally just feel sorry for them and often try to proselytize in the hopes of converting them to the one, true way to “save their souls.” But their punishment for those who leave the religion, or cult, or subcultural group is often severe—depending on how closed the knowledge system of the group is, the remaining members may be told to sever all ties to the person who leaves, cutting him or her off completely from the community s/he used to be part of—an extremely traumatizing “shunning” process practiced, for brief examples, by Scientologists, Jehovah's Witnesses, and the members of any full-fledged cult of any kind.

The most extreme example of Stage 1 thinkers, in my interpretation of these levels or stages of cognition, goes far beyond naïve realism and fundamentalism to fanaticism—the profound belief that their way is so right that those who do not adhere to it should be either converted or exterminated. Religious and other types of fanatics play an increasingly frightening role in today's world, terrorizing the rest of us with the constant threat of acts designed to bring about an end to the world as we know it and re-create it in the image they seek. Such fanatics, from the medieval Crusaders through the Spanish Inquisition and Hitler's Nazi movement to today's jihadists and other types of terrorists (including some members of the American “alt-right”) feel totally justified in killing people who are openly opposed to or simply do not share their beliefs, values, and cultural mores. In this contemporary world where people of many beliefs and cultures live in close proximity, fanatics can be extraordinarily dangerous in their efforts to either convert or destroy those who do not share their completely closed belief systems.

Ritual plays a critical role in the creation of Stage 1 thinkers. A ritual as I have long defined it is a patterned, repetitive and symbolic enactment of a culture or group's (or individual's) core values and beliefs. Through rhythmic repetition and the use of powerful core symbols, ritual constantly works to imprint or “penetrate” these core beliefs and the behaviors that accompany them into the minds and bodies of its participants—a process described in depth in The Power of Ritual (Davis-Floyd and Laughlin, 2016). Ritual is the most powerful tool for conversion to a particular belief system, as ritual is embodied and experiential—these are the deepest and most effective ways of learning, as Jordan (1997; Jordan and Davis-Floyd, 1993) has consistently shown. We tend to believe most deeply what we feel and experience most deeply. Understanding the power of experiential learning, the early missionaries to colonized regions usually began by drawing people to church services where they sang hymns and performed prayers and repeated chants—all deeply experiential—thus developing a feeling for the power of the new religion (Christianity) before they fully understood its didactic or intellectual rationale. Fundamentalist and fanatical preachers, totalitarian dictators, and cult leaders understand that power all too well, and use the intense practice of ritual to draw their converts in and keep the boundaries tight. The more hours their followers spend performing rituals that enact their belief systems, the less time they have to think beyond those systems to examine whether they even want to believe what they are constantly being taught.

All cultures and societies, all religions and belief systems, employ ritual to enact and display their beliefs and celebrate and continue their traditions. But there is a huge difference between holding a Chinese New Year's Festival, going to church on Sundays, or fasting during Ramadan, and trying to convert or punish those who do not practice the rituals you practice and believe as you believe. Rituals can be used to convert people into a certain worldview (from early childhood on, or later during adulthood) and stabilize them in it, and can also be used to trap people in that worldview and create an “us” vs. “them” mentality in their true believers.

Stage 2 Thinking: Ethnocentrism

To my way of thinking, Stage 2 thinkers are what anthropologists call ethnocentric. Ethnocentrists know that other ways of knowing and believing exist and are generally willing to acknowledge that it's OK for others to think differently. But they are entirely certain that their way is better. I and many other anthropologists have found that many, if not most, of us humans are ethnocentric—we can't help it unless we work really hard not to be, because that is most often the way we are raised. Our cultural ways are what we have internalized experientially from the womb on, and so we tend to regard them as right and proper. Stage 2 thinkers may feel and express pity or scorn for “others” who don't understand how much better “our way” is. Stage 2 ethnocentrism, while broader than Stage 1 cognitive systems, is also a relatively closed system, constantly reinforced by the rituals that enact and sustain it. Yet ethnocentrists in general are not fanatic nor fundamentalist—they are often very willing to explore and learn about other cultures, other ways of thinking and being, out of curiosity and a desire to expand their horizons—yet generally remain convinced that their way is best, no matter how widely they travel. Again, many of us are ethnocentric to our cores, even when we try hard not to be.

For one example, many Americans are so ethnocentric that they believe the United States must be Number 1 in all things and must remain the most powerful country in the world. Their ethnocentrism, along with that of many Russians, Chinese, Europeans, and others is the reason we will likely never have a world government with any actual power—few if any countries would be willing to mitigate their sovereignty, even if actually having a world government might stop wars and climate change, might pass enforceable laws against pollution, ethnic cleansing, human trafficking. Instead of seeing a world government as a potentially good thing, people in general are too afraid of subordinating whatever power their own countries have, too afraid of the very real possibility that a world government might turn into a dictatorship ruled perhaps by corporations or power-hungry technocrats. Instead we have the United Nations—an organization with lofty goals but little power to achieve them—but which does offer the possibility of world “governance”—government by consensus among sovereign nations. But to make that work, we must move beyond ethnocentrism to more open systems that work for the good of all.

Relatively Open Knowledge Systems: Stages 3 and 4

Stage 3 Thinking: Cultural Relativism

In dramatic contrast to Stage 1 and 2 thinkers, Stage 3 thinkers are very open. They come to a realization at some point in their lives that every culture and religion has created its own story about the nature and structure of reality, and that no one has the authority to say which story is right. In anthropological terms, I suggest that Stage 3 thinkers are cultural relativists who come to see every story about reality as relative to every other story. Nobody has a lock on truth, and every knowledge system must be understood in terms of its own ecological, historical, ideological, and political context and must be respected as legitimate in its own right. Every culture's rituals are worth description and interpretation. Many anthropologists are cultural relativists who strongly believe that comparing a given culture with another is the best way to understand the uniqueness of that culture and its ways, for cross-cultural comparison highlights otherwise invisible aspects of every culture. Cultural relativism can sound ideal—it entails respect for, appreciation of and understanding of every story that every culture or religion tells, and of the laws and traditions of each and every society. Such tolerance! No bigotry, no racism, no ethnocentrism, no judgment.

And yet cultural relativism as a way of thinking has severe limitations. In some cultures, such as those of rural Pakistan, men are entitled to beat their wives every night just to remind them who is boss. In some cultures, torture of political prisoners is normal. In many capitalistic cultures, environmental pollution is normative, especially when it is profitable in the short term. In some cultures, it is mandatory to practice what outsiders call female genital “mutilation.” And in hospitals around the world, especially in low resource countries, treating birthing women with disrespect and abuse is so culturally normative that it has been officially named by those who critique it—“obstetric violence.” Given that all such practices are part of their “cultures,” a true cultural relativist would seek no change at all, respecting the cultural beliefs that lead such practices. Is that OK? By what standards can cultural relativists say that it is not?

Stage 4 Thinking: Global Humanism

This dilemma posed by cultural relativism has led to an increased global focus on the development of Stage 4 thinking, which I link to what many anthropologists and ethicists call global humanism. Stage 4 global humanist thinkers recognize the intrinsic integrity and value of every cultural and religious story, every set of customs, beliefs, and the rituals that enact them, yet seek higher standards that can be applied in every context to ensure the rights of individuals, most particularly the poorer and weaker members of society. No one should be beaten, murdered, mutilated, tortured, raped, abused, or discriminated against in the name of any cause, sociocultural hierarchy, or belief system. Everyone should have access to clean water, good nutrition, effective health care and fair pay for their work. Daughters should be viewed as intrinsically valuable as sons. Such seemingly desirable goals can often go deeply against the grain of a given culture—as in South Africa before the end of apartheid, as in the many cultures that supervalue boys over girls. Thus many global humanists seek to think beyond the limitations of cultural relativism, searching for universal standards that work for everyone. They want to validate and legitimate every culture and every individual, while devaluing and discouraging specific cultural practices that hurt people who do not deserve to be hurt in this higher, human rights sense.

Global humanists tend to be acutely aware of the structural inequities (of race, ethnicity, class, education, gender, socio-economic and cultural status, and so on) that pervade contemporary societies, and often do their best to address and work to find solutions for them. Global humanists are also aware that they are on an almost impossible set of missions—how can you work to preserve a culture while also working to change key aspects of it (like getting men to stop beating their wives, or ending the poverty induced by the global culture of technocracy and capitalism, or fostering the education of girls and women in nations where they are devalued)? Those working in maternity-related fields know well that such structural inequities are largely responsible for the high maternal and perinatal mortality rates of low-resource nations, where effective care is provided for the wealthy but not for the poor, and men have decision making power over women.

Yet such missions must be attempted anyway for the good of all. Global humanists understand that they must keep their knowledge systems open to new information and engage in bioethical discussion and debate, trying to figure out what works best to preserve everyone's rights without assuming superiority for any one system. For example, many work to lower maternal and perinatal mortality rates without buying into the capitalistic/technocratic notion that traditional midwives should be eliminated because “facility births are always better,” no matter how low-quality that facility care may be (see below). Some traditional birthways are far better than those of hospital birth, and vice-versa. So in birth, global humanists look for what actually works best, rather than what is simply assumed to work best in the global culture of techno-medicine.

Stage 4 thinkers do develop and perform rituals, but such rituals are usually very fluid attempts to express and enact larger, more global values. Since the beliefs of Stage 4 thinkers are open to flux and change, the rituals they create tend to constantly change as well, or to be spontaneous enactments of something going on in the moment, such as for example, the 2017 peace march by Israeli and Palestinian women, or the songs about love, peace, and the strength of women often sung at the end of Midwifery Today conferences with everyone forming a circle and holding hands.

There is no greater challenge to Stage 1 fundamentalists and fanatics than global humanism—and vice-versa. Global humanism says that there can be many right ways as long as everyone's individual rights are preserved; fundamentalists and fanatics say there is only one right way, and only their leaders get to decide who has what rights. Fundamentalists and fanatics seek to build temples of isolation, rigid silos within which their rules can prevail—where cults and sects can practice their belief systems without interference—and including silos designed to protect the turf of a given profession (e.g., obstetrics) against others with overlapping claims to parts of that turf (e.g., midwives). Fundamentalists and fanatics hold tight to their concrete silos, standing firm against the swirling, constantly changing cultural forms of our late modern technocracy. True cultural relativists would have no grounds for criticizing these cultural and professional silos, whereas true global humanists would want to ensure that everyone within them chooses freely to be there and has their rights as human beings honored, even when they step outside the silo box—which is so often not the case. Thus, Stage 1 fundamentalists and fanatics abhor global humanists, in life and in birth, and, again, vice-versa—global humanists abhor the loss of individual freedom of choice that those in charge of such silos can so easily take away.

This concept that individual have rights is relatively new in human history. Its early roots can be traced to the Magna Carta, signed in 1215 by King John of England, guaranteeing for the first time that the king did not have absolute power, but had to acknowledge the sovereign rights of the nobility—the dukes, barons, earls—to own their own lands and generally rule them as they saw fit. Yet the concept that serfs, peasants, and the poor in general had rights too did not gain much traction until the American Revolution of 1776 with its Declaration of Independence, which acknowledged the rights of white males—that was a start—and the French Revolution of 1789, and later the Russian Revolution of 1912 that overthrew the Czar and brought in the communist system, in which every individual was supposed to have rights—until Stage 1 totalitarian dictators took over and that notion went back to the back-burner. And then came the United Nations, which took on the issue of global human rights in a very powerful way, formalizing in key documents for the first time in the world the concept that every human being has certain rights. Yet the granting of those rights seemed to apply mostly to men, until the UN 4th World Congress on Women held in Beijing in 1995, where Hillary Clinton so powerfully stated that “women's and children's rights are human rights.” And that concept opened the way for birthing women to use human rights language to claim that their human rights must be honored in birth as in daily life.

The Foundational Principles of the International Childbirth Initiative: A Focus on Women's Rights

For example, an early draft of the newly developed International Childbirth Initiative: 12 Steps to Safe and Respectful MotherBaby-Family Maternity Care, a globally humanistic template for practice created by FIGO and the International MotherBaby Childbirth Organization and designed to be applicable in all birth settings, notes in its Foundational Principles that: all rights are grounded in established international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; the Declaration of the Elimination of Violence Against Women; the Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Preventable Maternal Mortality and Morbidity and Human Rights; and the United Nations 4th World Conference on Women, Beijing, all of which make specific reference to birthing women's rights.

All of the above Rights documents are critical to understanding that negligent, non-evidence-based, abusive, or extortive care in maternity care services are violations of women's human rights and evidence of gender inequities. The document that provides the strongest support for humanistic, quality care is the charter on Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women (White Ribbon Alliance, 2011). This charter has served not only to raise awareness of childbearing women's rights, but also to clarify the connection between human rights and quality maternity care. It can further support maternal health advocates to hold health systems, communities, and governments accountable. This charter aims to promote respectful and dignified care during labor in line with best clinical practices, to address the issue of disrespect and abuse by providers toward women seeking maternity care, and to provide a platform for improvement by:

• Raising awareness of and guaranteeing childbearing women's rights as recognized in internationally adopted declarations, conventions, and covenants;

• Using human rights language in issues relevant to maternity care;

• Increasing the capacity of maternal and newborn health advocates to participate in human rights processes;

• Aligning childbearing women's entitlement to high-quality maternity and newborn care with international human-rights-based standards; and

• Providing a basis for holding maternal and newborn care systems, communities, and providers accountable to these rights.

Since these rights are non-obvious to many obstetricians and not recognized by them, feminist activists have managed to get legislation passed in Venezuela, Argentina, Panama, and Mexico guaranteeing women the right to have companions during their labors and births and protecting them from obstetric violence, disrespect, and abuse. These are positive steps forward, yet to date, there have been no mechanisms to enforce these laws: technocratic silo-oriented OBs in these countries simply ignore them and continue their traditional ritual practices, forcing women to labor without companionship, cutting episiotomies on all who do not have cesareans, often treating them disrespectfully and even abusively, and denying their protagonism in birth and their supposed informed freedom of choice.

In previous works (Davis-Floyd, 1992/2003, 2018a,b), I answered the question of “why” they do so via my analysis of the intense socialization of obstetricians into the technocratic model of birth via their many years of training, during which they are both bodily and psychologically habituated to the rituals of hospital birth. According to the epidemiologists I have also interviewed, and many of my physician interlocutors as well, the intensity and longevity of this socialization generates “narrow-mindedness” and “tunnel vision” (Stage 1). Below I explore narrow-mindedness and how it fits into the larger schema of the 4 Stages of Cognition I outline above, which of course have implications for all of us, but here I will reflect on their implications for birth practitioners of all types.

Please note: The four stages of cognition as I outline them here have nothing to do with intelligence levels nor necessarily with all areas of life—it is quite possible to be a fluid thinker in other areas while being a rigid thinker in one or several. For example, a quantum physicist studying ambiguities in the universe with a completely open mind to the existence of other universes, string theory, the “multiverse” and other dimensions may also be a faithful Catholic, while a fundamentalist Christian preacher may hold several PhDs in various fields. How fundamentalist or fanatical you are in your particular ideological silo tends to depend on your level of socialization and embodied habituation into the areas in which your thinking becomes rigidified—the deeper the socialization and habituation, and the more rituals associated with them, the “truer believer” you are.

Birth Practitioners and the 4 Stages of Cognition (see Table 1)

Stages 1 And 2: Birth Knowledge Systems

Many traditional midwives, some professional midwives, many nurses, and most obstetricians are Stage 1 or 2 thinkers in terms of maternity care. Indigenous midwives, if left alone, are most likely to be Stage 1 thinkers, practicing as they were taught by their mentors or, as many of them say, “by God.” Many indigenous or traditional midwives are highly skilled and carry on ancient birthing knowledge that is mostly functional and practical—but not always, as some traditional practices (like many technomedical practices) can be quite harmful. So their Stage 1 systems are a mixed bag when viewed from an evidence-based perspective—much good, some harm.

Stage 1 naïve realist practitioners can work within their settings, whether community or facility based, for their lifetimes, without ever questioning their practices and the beliefs that underlie them, because they simply know no other way. But there are few OBs in the world who do not know that their practices are constantly scrutinized and criticized by the thousands of birth activists in many countries, by many of their patients, by some of the more humanistically-inclined midwives and nurses who work with them, and by the doulas who increasingly attend to the support needs of the laboring women under their care (and who often suggest that their client should reject the interventionist treatment they are receiving—sometimes causing the doctors to resent these doulas mightily).

Ethnocentric (“There are other ways, but our way is best”) obstetricians who feel themselves under siege in their practices have choices: (1) They can become curious to learn why their standard practices are so heavily critiqued, examine the evidence, listen to women, and ultimately choose to grow beyond the limitations of their training and make a paradigm shift to the more fluid thinking that humanistic or holistic practice requires. (See Davis-Floyd, 2018a for a full explication of the technocratic, humanistic, and holistic models of birth.) A few do take this path, like the Stage 4 (self-named and woman-centered) “good guys and girls” of Brazil, who usually work with midwives and often have CS rates of around 15% (Davis-Floyd and Georges, 2018). (2) They can take refuge in their Stage 1 silos, developing a fundamentalist attitude and performing their rituals/standard procedures as they always have—choosing to ignore both the scientific evidence and the growing criticisms and efforts of others to force them to change. (3) They can go deeper into Stage 1, “circling the wagons” by becoming highly defensive, even fanatical, critiquing and imposing harsh punishments on their colleagues who “go rogue”/step out of the silo by humanizing their practices.

For example, in Brazil in 2012, a well-respected obstetric professor, Dr. Jorge Kuhn, during a nationally-broadcast TV interview, declared that he supported homebirth—as long as the birth was attended by a skilled professional and transport arrangements were in place. In an extremely fanatical overreaction, the medical council of Rio de Janeiro (CREMERJ) immediately called for his license to be revoked, completely refusing to even look at the irrefutable evidence on which he had based his statement. (See Anderson et al., for a compilation of that evidence2). These actions led to a major series of marches in the streets by women demanding the rights to homebirth, companionship during labor, and other issues (see Figure 1), to which CREMERJ, again fanatically, responded by forbidding any doctor to attend homebirths, causing all of Brazil's humanistic OBs to stop doing so (leaving homebirth attendance to the midwives, who are few in number in Brazil while obs are many).

Figure 1. In 31 cities around Brazil, and 1 in Italy, thousands of people marched for the humanization of birth, for women's rights in childbirth, and in support of homebirth. Photo by a marcher.

Another example of this sort of fanatical medical backlash was Brazil's first forced cesarean section: on April 1, 2014, a woman named Adelir was denied permission while in labor in a hospital to attempt a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), so she left to labor at home, but was forcibly transported back to the hospital for a court-ordered CS. She was deeply traumatized, but took heart when birth activists all over the country adopted the globally humanistic Stage 4 slogan “We are all Adelir” (see Figure 2) and protested with thousands of letters and more marches. (Adelir later enrolled in a nurse-midwifery program so she could provide the kind of care she wished had been given to her).

Figure 2. This drawing circulated across Brazil as thousands protested her forced cesarean. Drawing by Ana Muriel.

Other examples of technomedical fanaticism at work include:

• Ágnes Geréb of Hungary, an obstetrician and midwife who attended thousands of homebirths until she was arrested on false charges, put in prison for 77 days and then house arrest for three years, then sentenced to two more years in prison—all because the powerful Stage 1 OBs in Hungary hated her for rejecting their profession by becoming a midwife, attending homebirths, and keeping the woman at the center, and despite massive national and international protest (see Figure 3) addressed directly to the President of Hungary. These protests finally, in 2018, succeeded in convincing him to revoke her second prison sentence but not to allow her to practice again for 10 years (she is 67)—showing the power of concerted activism to create change, while also demonstrating the power of the Hungarian medical establishment to prevent an “outside-the-silo” practitioner from future practice.

• Ricardo Jones, a humanistic and holistic OB who practiced both home and hospital births for 34 years in a teamwork model with his wife Zeza, a midwife, and a group of doulas, with excellent outcomes. His license was revoked by the medical board of his region six years after their team attended a homebirth following which the baby died a day later due to inappropriate NICU treatment after an appropriate hospital transport. This blaming was purely political—the Stage 1 doctors in Ric's region had been trying to get rid of him for years because of his unorthodox, Stage 4 humanistic practice. Again, global humanists like Ric, Agi, and Jorge Kuhn are anathema to Stage 1 fundamentalists and fanatics. (For Ric's description of his teamwork practice, see Jones, 2009; Figure 4).

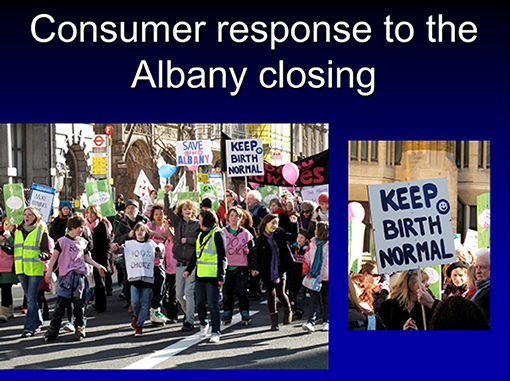

• The closure of the Albany Midwifery Practice by King's Hospital in London. For decades the Albany was touted as one of the best midwifery practices in Europe. Yet, after reaching a 43% homebirth rate (in a country where the overall homebirth rate was around 2%), they were suddenly shut down by their hospital in what many interpret as strong and fear-based overreaction to this high homebirth rate. Despite marches in the streets and other forms of protest from their former clientele (see Figure 5), they were never allowed to re-open. (For the story of how the Albany practice functioned, see Reed and Walton, 2009, and for the story of its closure, after-effects, and full practice statistics, see Reed and Walton, unpublished manuscript3).

Figure 3. Protest sign “Free Geréb!” on the banks of the Danube, close to the Parliament on December 10, 2010, with permission of photographer István Csintalan.

Figure 4. Ric photographs a holistic hospital birth attended by his team. The midwife reassures the birthing woman while the doula massages her lower back. Note the physiologic squatting position, which helps with gravity and aids the pelvis to open much further than it would if she were flat on her back.

Such examples reveal the power of a closed, fundamentalist, and sometimes fanatical obstetric system to eliminate challenges to its ongoing hegemony. I could list hundreds of such cases, as such “witch-hunts” of Stage 4 birth practitioners take place all over the world. This closed technocratic obstetric system, when fanatically applied as Stage 1, has ruined many of the lives of those who oppose it, and will likely seek to continue to do so for years to come as its hegemony is increasingly challenged, both by scientific research and by humanistic practitioners who put the woman, not the system, first.

Technocratic medicine in general is an extremely ethnocentric and relatively closed Stage 2 system, often degenerating into Stage 1 when challenged, as we have just seen. Its practitioners are constantly exposed to new information, yet they tend to incorporate only the kinds of new information that fit within their pre-existing knowledge system. Physicians, for example, are socialized into technomedical ways of thinking, knowing and believing for at least four years of medical school, three years of residency, and often more if they go into subspecialties (Davis-Floyd, 1987, 2018c). Confronted with information that does not match what they learned during their training, they are most likely to ignore or discount it. Obstetricians who read a study comparing epidurals with other types of pain medication can easily process that kind of information, for example, but the same obstetricians presented with multiple studies that demonstrate the benefits of doulas, being in water, massage, and constant changes in position for pain relief will be likely to discount this kind of information, which completely contradicts the technocratic paradigm they are taught.

Most obstetricians can barely keep up with the information that comes across their desks every day that updates them on the latest drugs and technologies (simply amplifying things they already know). Entrenched in a belief system that relies on drugs and technological interventions to manage birth, they see no reason to exert the much greater amounts of energy it would take to assimilate information from outside their technocratic paradigm. This is also true of thousands of professional midwives around the world, who work hard to learn accepted biomedical ways and then are thrust into busy practices. Overworked, overstressed and often underpaid, they too may be unwilling to open their cognitive systems to processing information that contradicts the technocratic approaches they are taught. Birth is not a good catalyst for change in such cases, as most babies come out alive and relatively healthy most of the time anyway (though the negative psychological and physical effects on the mother and the baby of mistreatment during birth can be extreme). So the more you do it in your habitual ways, the more it becomes the only way you can imagine doing it.

It is ironic that science, which was supposed to be the foundation of obstetrics, does not support most standard obstetrical practices. Yet “science” has been used by obstetricians for 150 years to justify the interventions they invented and then increasingly performed. Science used ethnocentrically for Stage 1 or 2 technomedical thinkers is a blinder for what is really medical tradition, passed down from teacher to student through apprenticeship/experiential learning.

The metaphor of a busy office may illustrate the multiple possibilities such Stage 1 or 2 practitioners have for dealing with new information: if it fits their dominant paradigm, it can flow along their established neural pathways and be assimilated; if it does not, it can be discarded as irrelevant nonsense and thrown in the metaphorical trash; or it could be filed way in the “back” of the brain, where the synaptic connections stop, in a (metaphorical) filing cabinet labeled “information I don't want to process right now but might be useful sometime.” If it is so stored, the more it is accessed or added to, the wider become the neural pathways leading to it—and gradually, change based on that new information can occur. Stage 2 ethnocentric obstetricians do generally believe their way is best, but those who are neither fundamentalists nor fanatics often show a willingness to at least examine other ways, often out of simple curiosity. And again, such examination and openness to new learning can and often does lead to positive change.

Stage 3: Cultural Relativist Obstetric Knowledge Systems

Based on my 35 years of interviewing and working with hundreds of birth practitioners of all types, I have concluded that very few birth practitioners in the contemporary world are true cultural relativists. They deal with life and death and know that their decisions can result in either one. Stage 1 (naïve realist, fundamentalist, and fanatical) practitioners make decisions based on the only knowledge they have; Stage 2 (ethnocentric) practitioners make decisions based on the knowledge they are sure is best and to which they are habituated. But of the all the birth practitioners I have talked with, I can't think of one cultural relativist who bases his or her decisions on no standards at all just because he or she can't choose between the many viable care standards out there. Postpartum hemorrhages must be stopped if at all possible. Babies in transverse lie cannot be born unless the attendant does something (such as performing a cesarean, or alternatively reaching in and grabbing the feet to pull them down while sweeping up the arms so they will not stick in the birth canal—a skill some few midwives, both traditional and professional, possess while almost no doctors do). Pregnant women will die of eclampsia if they do not receive effective prenatal care.

Stage 1 and 2 practitioners will deal with such complications as their socialization dictates. But those with open minds and systems fluid enough to encompass multiple cultural realities will not be content to approach such complications in whatever way the culture of the woman they are attending or their own medical traditions would dictate—if they have found or studied the evidence that those medical traditions do not work. If they know a way that is scientifically proven to have better efficacy than a traditional way (whether “traditional” in a technomedical or an indigenous sense), they will apply it. The decisions they make in life-crisis situations are not based on a “whatever the dominant model says” attitude, but rather on a “whatever works” attitude. And what birth attendants with open cognitive systems know about what works will constantly change as they are exposed to new information, whether it comes from science, traditional midwifery, a book they happened to read, or a workshop they just attended the daybefore.

Stage 4: Global Humanist Birth Knowledge Systems

In today's rapidly changing and highly fluid world, to be truly effective, practitioners must remain open to the new information that is constantly emerging from real science and from the increasing availability of birth knowledge from multiple systems—allopathic, indigenous, holistic, integrative. Sometimes the best option for a birth complication might be emotional support or a homeopathic remedy; sometimes it might be a position used by traditional midwives; sometimes it might be a cesarean section. The Stage 4 practitioner will keep her system open to new learning from many sources in a highly postmodern way; she will practice what I call informed relativism (Davis-Floyd et al., 2018)—comparing knowledge systems and techniques and choosing what works best for her from among many options. And she will seek to practice according to the highest moral and ethical standards, which involve giving compassionate, woman-centered care responsive to the needs of the individual, regardless of what “the system” dictates.

Why Many Birth Attendants Do Not Give Stage 4 Care

Cognitive openness and humane standards are not easy to maintain, especially in a busy and stressful practice. Even those Stage 4 practitioners who want to remain open to new learning and new ways of thinking find that the more stress they are under, the less able and willing they are to process new information. Persistent stress can reduce even highly fluid, Stage 4 thinkers to Stage 1 levels by causing cognitive overload and the development of “tunnel vision”—the need to shut out most stimuli and focus on one thing only. In other words, stress can make fluid thinkers become rigid, if only for a while. How often have you thought, on an especially stressful day, “I can't deal with any more information—just don't tell me one more thing”? Usually rest or a vacation will restore Stage 4 thinkers to their normal fluid state. But if the stress continues for too long or becomes too intense, anyone can disintegrate into Substage—a condition ranging on its lighter side from intense irritability and anger, lack of compassion for others, burnout, and “losing it” to its more disastrous side—outright panic, hysteria, or even a full-fledged nervous breakdown. In Substage, it is very easy to abuse others and very hard not to do so.

Performing rituals can stabilize individuals under stress at Stage 1, thereby preventing them from degenerating into Substage. When the crops fail, you make offerings to the gods. When your life seems to be falling apart, you might return to the church of your childhood to recover some sense of stability. When labor slows, you administer pitocin, or rush to perform a cesarean. Stage 1 rituals can generate a sense that everything is under control (even if it isn't). Practitioners facing what they see as constant potential crises in childbirth use such Stage 1 rituals preventatively, so that things at least feel or seem to be under control.

Let's take a quick look at what women studied by anthropologists all over the world have said about professional midwives and doctors working under high levels of stress, especially in low-resource countries4:

“They shave you.”

“They cut you.”

“They leave you alone.”

“They don't let your family members in to be with you.”

“They give you nothing to eat or drink, even if you are hungry or thirsty.”

“They yell at you and sometimes, they slap you.”

Perhaps most practitioners who work in these ways at first approached obstetrics or midwifery with high ideals of serving women. But if you are practicing in a rural clinic in Papua New Guinea or a huge hospital in India, where supplies are limited or nonexistent, there are more women than you can possibly care for, the toilets are filthy and there is often no running water or electricity, and little or no food available for the women, you are treated as inferior by your superiors and nastily by those under you who resent your authority, and you are paid so little you can barely support your family, it is most likely that your ideals will fade away in face of unbearable realities. You may well shut down cognitively and focus on finding any bits of pleasure or relaxation you can. In other words, you will take every opportunity to drink coffee with your colleagues and ignore or mistreat, even abuse the women screaming for help in the next room. Such are the effects of stress, overwork, underpay and professional devaluation. Many anthropologists have noted that practitioners new to work in such places are often initially horrified by the behavior of their elders and work harder to support and care for the women, yet a few months or years later, will be behaving exactly like the colleagues whose behavior they initially abhorred. It is important to emphasize that ongoing stress can lower one's cognitive level from Stage 4 to Stage 1—a conceptual space in which you don't have to think—you just go on “automatic pilot.”And the more stress you are under, the harder it becomes to “think beyond” and the more likely you are to slip into Substage—“burning out,” “losing it,” and sometimes taking out your stress on laboring women by slapping, yelling at, and otherwise abusing them.

What about practitioners in the developed world, where technology, supplies, clean water and food are readily available, the pay is reasonable and schedules offer time off to be with one's family? Indeed, it is this kind of practitioner who is most likely to care about moving beyond rigid knowledge systems to create a more open, fluid and individually responsive style of midwifery care. And yet even professionals in high-resource countries are likely to succumb to the pressures of technomedical socialization and habituation to certain routines, to practice defensively to avoid accusations of malpractice, to conform to institutional systems rather than take the time and energy to fight them.

How Midwives and Obstetricians Can Foster Stage 4 Thinking

1. Attendance at midwifery conferences. Again, to move from technocratic to humanistic or holistic practice (from Stage 1 to Stage 4) requires a tremendous amount of new learning, which requires a great deal of time, attention, and energy. At conferences, practitioners are free to put in that time and energy to develop new neural networks to assimilate new information. There they may be exposed to ways of thinking, knowing and practicing that differ from their own. The midwives in the developed world who tend to become rigid in their practices rarely attend such conferences; they are the ones who most need to attend. And this may sound like a strange recommendation for obstetricians, but all of the humanistic and holistic obs I have interviewed have done exactly that—attend midwifery, not obstetric, conferences. At obstetric conferences, you tend to learn more of what you already know—your belief system is not challenged as it would be at a midwifery conference where “the midwifery model of care” with its woman-centered focus and its many accompanying hands-on skills is taught and demonstrated in lectures and workshops. When OBs show up at midwifery conferences, they generally receive a great deal of support from the midwives they meet for their efforts to learn and change. And if they have already learned and changed, they get to present the practice models they have developed and receive feedback on them that can help to make them better. I have witnessed even highly holistic obs go into shock when they hear how midwives can perform external versions, manually deliver breech and even transverse babies, stop hemorrhages without Pitocin—and rather than scorn the midwives as crazy or irresponsible, they huddle up with them to learn these techniques themselves.

Over the past 35 years, I have attended hundreds of midwifery conferences and have watched how both midwives and the few obs who attend “get their juice” by being there. Midwifery Today conferences are particularly salient in developing and maintaining Stage 4 thinking in midwifery or obstetric practice. Jan Tritten, their organizer, makes every effort to include all types of midwives—professional, traditional, nurse-, direct-entry—on her programs, as well as some holistic obs from various countries, so that every Midwifery Today conference provides opportunities for attendees to be exposed to the ways others think and know. In the US, the annual conferences held by the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) and the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA) also provide many such opportunities; their conferences include workshops that range from the highly technical to the highly holistic.

Particularly exciting are conferences held in countries where midwives and obstetricians are just beginning to move outside their normative practices, such as the annual Siaparto and the triennual ReHuNa conferences in Brazil. The also-triennial congresses held by the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) bring together professional midwives from all over the world, and every time slot on the program offers at least a dozen sessions addressing to multiple types of midwifery knowledge, skills, special interests, and cultural approaches. Small-scale regional midwifery conferences allow practitioners living in relatively close proximity to share common interests and expand their knowledge bases about their own history and political situations. Every midwifery conference I have ever attended has offered its participants many ways to “think beyond” established paradigms and practices; thus I encourage every practicing and student midwife, obstetric nurse, doula, and obstetrician to attend as many such conferences as they possibly can.

2. Learning from women. Birth attendants who practice the same way for many years are usually those who have stopped listening to mothers. Every woman a practitioner attends can bring something new to her knowledge and practice. I have often been struck by the changes in practice that can result from listening carefully to and learning from even one woman, who perhaps is unusual but can teach the practitioner something new about how best to provide woman-centered care.

3. Learning from midwives. The birth stories OBs tell usually focus on pathologies that they find intrinsically interesting because of the intellectual puzzles they present, or crises in which they saved or failed to save a life. In dramatic contrast, midwives tend to tell stories of normal birth, or of how they figured out how to help a birth that could have become pathological stay normal (a process I call normalizing uniqueness (Davis-Floyd and Davis, 2018). Much midwifery lore and knowledge are encoded in these stories. If you want to understand the normal physiology of birth in its wide variations, listen to them, record them, write books and articles full of them so that others can learn what your stories have to teach!

And read the ones already written—they include Ina May Gaskin's Spiritual Midwifery, Ina May's Guide to Childbirth (the first half of which is full of wonderful stories), and Birth Matters; Penfield Chester's Sisters on a Journey; Geradine Simkins' Into These Hands: Wisdom from Midwives; A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary 1785–1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich; Sister Morningstar's The Power of Women; Carol Leonard's Lady's Hands, Lion's Heart; Eleanor Barrington's Midwifery Is Catching; Diary of a Midwife: The Power of Positive Childbearing by Juliana van Olphen-Fehr; Jennifer Worth's famous Call the Midwife, on which the popular TV series is based, and many others, all of which can be found listed in an Annotated Bibliography I and others have created and which is available on the website of the Council on Anthropology and Reproduction (CAR) (at https://goo.gl/heqkX7)—including a whole raft of books telling the stories of revered “Black granny midwives” like Gladys Milton and Margaret Charles Smith, many of whom attended births in the American South at a time when Black women were not admitted to hospitals, so these midwives had to deal with any complications that arose as best they could, developing many skills as they went along.

4. Attention to the scientific evidence. The body of scientific evidence supporting many traditional and professional midwifery practices that facilitate normal, physiologic birth is ever-growing and now includes meta-analyses from the renowned Cochrane Reviews and the Lancet series on midwifery, for two examples. Every birth attendant should keep up with this evidence, as so much of it reinforces “the midwifery model of care” (see Rooks, 1999; Davis-Floyd, 2018d for descriptions of this model). Real science differs fundamentally from biomedical tradition. Every Stage 4 practitioner should have science at his or her command—all references ready to counteract every techno-medical objection to the kind of care s/he wishes to give.

5. Attention to other healing philosophies and modalities. Naturopathy, chiropractic, homeopathy, Reiki, breath therapy, massage therapy, pre- and perinatal psychology, Ayurveda, Chinese medicine and many other types of “complementary,” “holistic” or “functional” health care, as well as many indigenous knowledge systems, have much to offer the contemporary birth practitioner. It is not possible for everyone to know all of these systems, but it is possible to be open to what they can offer by learning about them (for example, some chiropractors are experts in positioning the baby properly for birth, and/or in healing or correcting post-birth injuries or traumas to the baby's neck or spine), incorporating one or some of them, and finding practitioners to whom clients can be referred.

Conclusion: Rigid vs. Fluid Ways of Thinking and the 4 Stages of Cognition

To recap, in this article I have made a clear distinction between rigid and fluid ways of thinking, described 4 Stages of Cognition originally explicated by others, and equated them to what I suggest are their anthropological equivalents. Stage 1 (rigid, concrete) thinking incorporates naïve realism (our way is the only way because we know no other way), fundamentalism (our way is the only right way), and fanaticism (our way is so right that those who do not adhere to it should be either converted or exterminated). I equated Stage 2 thinking to ethnocentrism (we know there are other ways, and that's OK for others, but our way is better!). I correlated Stage 3 thinking with cultural relativism—a very fluid way of thinking (all ways are equal in relative value and no way is better than any other), yet one that offers no way of thinking above and beyond the limitations of “culture” in general. Thus I went on to correlate Stage 4 fluid thinking as global humanism—while respecting each culture, we must seek and establish standards that put the human rights of each individual above cultural mores and traditions that dishonor such rights. I explained each of these Stages of Cognition in relation to each other, and mentioned how ritual can be employed to reinforce these ways of thinking, and to reduce many kinds of stress by solidly grounding individuals in their belief system and worldview, giving them a sense of safety and stability in an uncertain world, and keeping them from “losing it” by regressing into Substage, or helping to bring them back into functionality by getting them out of Substage.

Around the world, midwives and humanistic and holistic obs are under siege as the power of technomedicine grows. Traditional midwives in many countries are in danger of extinction, having already been pushed out of practice or simply died off; professional midwives are too often either naïve or ethnocentric servants to techno-medical ways of knowing and practicing; and many practitioners, including obstetricians, who reject those ways are often persecuted and punished by “the system.” Yet in every country, there are dozens and sometimes thousands of birth practitioners, both traditional and professional, who are Stage 4 global humanists striving to think beyond established paradigms and practices. Davis-Floyd and Georges (2018) have described 32 OBs who have become Stage 4, globally humanistic practitioners, and in “Daughter of Time: The Postmodern Midwife” (Davis-Floyd et al., 2018), my colleagues and I have described midwives who have done the same.

Such practitioners, when not under too much stress, are practicing informed relativism, constantly working to combine the best of premodern indigenous techniques, modern allopathic, and complementary/holistic/integrative knowledge systems. They are responsive to women's needs and desires, to ideas and information from other health care workers, to scientific evidence, and to “whatever works” from wherever it can be learned.

If you are practicing in the twenty-first century, you have two brand new advantages that your historical counterparts did not have: (1) access to information from a rich variety of sources, including indigenous knowledge that has been documented by social scientists or sometimes by traditional midwives themselves (see for example Contreras, 2009) and real science, such as the Cochrane meta-analyses; and (2) strength in local, national, and international organizations. If you are a birth practitioner or a student, I ask you to utilize these strengths, acknowledge your limitations (remember that stress can take you “down” while spiritual and bodily nourishment can bring you up), and strive to keep your knowledge system open to the rich learning that this new and digitally interconnected world can provide.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Funding

RDF received two consecutive grants from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (Grants #6015 and #6247), which supported her research from 1996–2000, to study the professionalization of midwifery in the US, Canada, and Mexico, and later an ongoing grant (2004–present) from the Foundation for the Advancement of Midwifery to continue her research and publication on transformational birth models around the world.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Some few portions of this chapter are adapted from my earliest iteration of some of these ideas in my article Ways of Knowing: Open and Closed Systems, Midwifery Today 69: 9-13, 2004, copyright RDF and Midwifery Today. I thank Midwifery Today for constantly supporting and publishing my work, and its founder Jan Tritten for consistently inviting me to speak (from 1995 to the present, 2018) at the Midwifery Today conferences she and her team organize around the world, and for the knowledge, energy, and inspiration those conferences always provide. Thanks also to Charles Laughlin, my coauthor for The Power of Ritual, for helping me flesh out my anthropological interpretation of the 4 Stages of Cognition, which also appears in different form in that book.

Footnotes

1. ^The “four stages of cognition” schema I present here was initially presented in Human Information Processing: Individuals and Groups Functioning in Complex Social Situations by Schroder et al. (1967). The combination of this schema with the anthropological concepts of naïve realism/fundamentalism/fanaticism, ethnocentrism, cultural relativism and global humanism is entirely my own.

2. ^Anderson, D., Daviss, B. A., and Johnson, K. C. (2018). “Chapter 11: What if another 10% of deliveries occurred at home or in a birth center? The economics and politics of out-of-hospital birth in the United States,” in Speaking Truth to Power: Childbirth Models on the Human Rights Frontier, eds B. A. Daviss and R. Davis-Floyd (Unpublished Manuscript).

3. ^Reed, B. and Walton, C. “The final, positive outcomes of the Albany: a model that worked too well,” in Speaking Truth to Power: Childbirth Models on the Human Rights Frontier, eds B. A. Daviss and R. Davis-Floyd (Unpublished Manuscript).

4. ^The anthropological studies I draw on are too many to be listed here. They can be found in my book Ways of Knowing about Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (2018).

References

Contreras, D. (2009). Medicina Tradicional: Doña Queta y El Legado de Los Habitantes de las Nubes. Aida Guerra Falcon and Hamalgama Editorial.

Davis-Floyd, R (1992/2003). Birth as an American Rite of Passage, 2nd Edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Davis-Floyd, R. (2018a). “The technocratic, humanistic, and holistic paradigms of birth and health care,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 3–44.

Davis-Floyd, R. (2018b). “The rituals of hospital birth: enacting and transmitting the technocratic model,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 45–70.

Davis-Floyd, R. (2018c). “Medical training as technocratic initiation,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 107–140.

Davis-Floyd, R. (2018d). “The Midwifery Model of care: anthropological perspectives,” in Ways of Knowing about Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 323–338.

Davis-Floyd, R., and Cheyney, M (in press). Birth in Eight Cultures: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. Long Grove IL: Waveland Press.

Davis-Floyd, R., and Davis, D. (2018). “Chapter 7: Intuition as authoritative knowledge in midwifery and homebirth,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove IL: Waveland Press), 189–220.

Davis-Floyd, R., and Georges, E. (2018). “Chapter 5: The paradigm shift of holistic obstetricians: the ‘good guys and girls’ of Brazil,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 141–159.

Davis-Floyd, R., Matsuoka, E., Horan, H., Ruder, B., and Everson, C. (2018). “Chapter 8: Daughter of time: the postmodern midwife,” in Ways of Knowing About Birth: Mothers, Midwives, Medicine, and Birth Activism (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 221–264.

Davis-Floyd, R., and Sargent, C. (1997). Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hoffer, E. (1951). The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. New York, NY: Harper and Row, Perennial Classics.

Jones, R. (2009). “Chapter 10: Teamwork: an obstetrician, a midwife, and a doula,” in Birth Models That Work, eds R. Davis-Floyd, L. Barclay, B. A. Daviss, and J. Tritten (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 271–304.

Jordan, B. (1997). “Chapter 1: Authoritative knowledge and its construction,” in Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, eds R. Davis-Floyd and C. Sargent (Berkeley: University of California Press), 55–79.

Jordan, B., and Davis-Floyd, R. (1993). Birth in Four Cultures: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Reed, B., and Walton, C. (2009). “Chapter 5: The Albany midwifery practice,” in Birth Models That Work, eds R. Davis-Floyd, L. Barclay, B. A. Daviss, and J. Tritten (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 141–158.

Schroder, H. M., Driver, M. J., and Streufert, S. (1967). Human Information Processing. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

White Ribbon Alliance (2011). Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women (Full charter). Available online at: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/46_FinalRespectfulCareCharter.pdf

Keywords: birth, knowledge systems, cognition, culture, midwifery, obstetrics

Citation: Davis-Floyd RE (2018) Open and Closed Knowledge Systems, the 4 Stages of Cognition, and the Cultural Management of Birth. Front. Sociol. 3:23. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00023

Received: 27 February 2018; Accepted: 11 July 2018;

Published: 03 October 2018.

Edited by:

Kath Woodward, The Open University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sheila Cosminsky, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesPamela Stone, Hampshire College, United States

Copyright © 2018 Davis-Floyd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robbie E. Davis-Floyd, ZGF2aXMtZmxveWRAYXVzdGluLnV0ZXhhcy5lZHU=

Robbie E. Davis-Floyd

Robbie E. Davis-Floyd