Abstract

Geneticization is a concept originally introduced by Abby Lippman to critique the growing dominance of genetic explanations in health, identity, and society. Over the decades, the notion of geneticization has undergone significant development across various academic fields including sociology, bioethics, clinical medicine, and cultural studies, highlighting its broad relevance and impact on multiple areas of research. We conducted a scoping review of 25 peer-reviewed studies from 2011 and 2024, to investigate how the concept has been taken up, redefined, and challenged across multiple disciplines. Guided by two central research questions: (1) What are the prevailing themes surrounding geneticization in recent scholarship? and (2) To what extent do Lippman’s original concerns remain relevant? the review synthesizes insights from these studies, categorizing them across sociological, clinical, and ethical dimensions. Findings reveal a shift from deterministic framings toward more complex understandings, such as enlightened geneticization, biosociality, and biological citizenship, which highlight individuals’ agency in interpreting genetic information. At the same time, the review identifies ongoing risks of genetic reductionism in areas such as race, identity, reproduction, and education. The results underscore that while the term “geneticization” has evolved in both use and meaning, it remains a critical analytical lens for evaluating the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of genetic technologies. The review concludes by emphasizing the continued relevance of interdisciplinary inquiry and ethical vigilance in the genomic era.

1 Introduction

The term geneticization was first articulated in the early 1990s by Canadian epidemiologist and women’s health scholar (Lippman, 1991, 1992). In a series of influential publications, Lippman (1998) and Lippman (1993) offered a critical appraisal of the growing incorporation of genetic technologies into routine healthcare, with particular concern for their implications in prenatal screening and women’s reproductive health. Lippman (1991) warned that this trend risked reinforcing genetic determinism and reductionism, whereby individual identity and health outcomes were interpreted primarily through the lens of genetic composition, potentially silencing alternative, non-genetic explanations for disease and well-being. Her analysis laid the groundwork for a broader debate on how genetics shapes not only scientific practice but also cultural understandings of selfhood, responsibility, and belonging. Subsequent scholarships expanded Lippman’s framework, linking geneticization to broader sociological and ethical debates about the medicalization of everyday life (Gerhardt, 1989; Clarke et al., 2003). Like medicalization and biomedicalization, geneticization denotes the extension of biomedical reasoning into new domains, but with a distinctive focus on the authority of genetic knowledge.

The origins and applications of the concept of geneticization have been traced across a range of historical and disciplinary contexts. Flitner (2003) links the early use of genetics to state-led agricultural modernization programs in the 1920 and 1930s, where genetic science was intertwined with social Darwinist ideologies, reflecting the politicization of heredity in shaping populations. In the realm of medicine, Hoedemaekers and ten Have (1998) have critically examined the influence of geneticization on preventive screening and counseling practices, emphasizing its role in reshaping clinical paradigms. Ten Have (2001) further argues that Western societies are undergoing a profound redefinition of personhood, where individuals are increasingly interpreted through the lens of DNA codes and genetic language. He proposes that geneticization functions as a heuristic tool to redirect bioethical debates toward the interpersonal, institutional, and cultural dimensions of emerging genetic knowledge. Similarly, Stempsey (2006) characterizes geneticization as a transformative force in both medical diagnostics and societal understanding, while Horstman (2008) warns that this shift may marginalize social and cultural explanations of health and illness, privileging biological determinism over more holistic frameworks.

Building on earlier critiques, Hedgecoe (2009) offers an important empirical contribution by emphasizing that geneticization is not a uniform or simplistic process, but one shaped by complex individual and social interpretations of genetic information. His work underscores the ethical stakes of geneticization, arguing that it fosters a neo-ontological framing of disease where genetic identity becomes foundational to one’s being and may inadvertently promote genetic reductionism, with potential consequences such as discrimination and social inequality (Hedgecoe, 2009).

Over time, the concept has evolved beyond its original critique of reductionism to encompass more complex and context-sensitive analyses of how genetics intersects with identity, kinship, policy, and governance. As genetic technologies are increasingly embedded within healthcare systems globally, the demand for a multifaceted and interdisciplinary analysis of this phenomenon has become more pronounced. Scholarly engagement with geneticization has spanned various domains, which can be broadly categorized into three principal areas of investigation:

Sociology, anthropology, and culture: where geneticization is analyzed in relation to social structures, identity formation, and cultural narratives surrounding health and disease.

Ethics and bioethics: focusing on the moral, philosophical, and policy-related implications of genetic technologies, particularly concerning autonomy, consent, and equity.

Clinical practice and medicine: exploring the impact of geneticization on medical decision-making, patient care, and the role of genetic information in diagnostics and treatment.

This interdisciplinary perspective highlights the importance of moving beyond a narrowly biomedical interpretation of geneticization, urging a more comprehensive examination of its social, ethical, and clinical ramifications.

The rise of emerging medical paradigms such as personalized medicine, which is predicated on an individual’s genomic profile, has intensified the integration of genetic information into contemporary healthcare strategies. A key aim of global large-scale genome initiatives is not only to advance the development of precision and personalized medicine, but also to define the boundaries between normal and pathological genomic variation (Kovanda et al., 2021). These efforts are fundamentally informed by insights generated through genomic research. Moreover, the expanding societal reach of genetics is evident in the adoption of legal and policy frameworks in certain countries that require genetic testing as a prerequisite for marriage, underscoring the deepening influence of genomics in both medical and socio-legal domains, particularly over the past decade (Bener et al., 2019).

Despite a rich body of theoretical and empirical work, two comprehensive reviews—by Arribas-Ayllon (2016) and Weiner et al. (2017) have largely defined the state of the field to date. Both demonstrated how the term had shifted from a critical warning about determinism to a heuristic tool for studying the social and epistemic consequences of genomic science. However, these reviews were limited by their temporal scope and disciplinary focus. Arribas-Ayllon’s work centered on biosociality and disease classification, while Weiner and colleagues emphasized theoretical debates within sociology and science and technology studies (STS). The present review builds on these foundations by systematically synthesizing literature published between 2011 and 2024, a period marked by major genomic, technological, and ethical transformations. It integrates findings across sociology, bioethics, and clinical medicine—disciplines rarely examined together, thereby providing a broader interdisciplinary assessment of how the notion of geneticization has evolved in the postgenomic era.

In addition to this disciplinary synthesis, the present study situates geneticization within current public discourse, where the social and ethical stakes of genetic knowledge have become increasingly visible. The rise of direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing has enabled individuals to access and interpret their genomic data outside clinical contexts, reshaping notions of ancestry, health, and identity (Friedman and Anderson, 2024; Majumder et al., 2021). Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in genomics ranging from predictive diagnostics to algorithmic risk profiling have further blurred the boundary between medical science and data capitalism, raising new concerns about transparency, bias, and data sovereignty (Dara et al., 2025; Ahmed et al., 2023; Dias and Torkamani, 2019). Similarly, the use of genetic testing in forensics and immigration governance where ethical dilemmas around consent, unintended findings, and database use are increasingly prominent, illustrate how geneticization extends beyond healthcare into legal, investigative and political arenas (Sessa et al., 2024; Barata et al., 2015; Duster, 2015). Meanwhile, advances in epigenetics complicate earlier deterministic framings by emphasizing the reciprocal influence of environment and social experience on gene expression (Meloni, 2015; Lock, 2015). Together, these developments underscore that the discourse on geneticization remains both empirically and normatively vital, requiring renewed attention to its ethical, social, and policy implications in a rapidly evolving genomic landscape.

Accordingly, this review examines how recent scholarship has reinterpreted and operationalized the concept of geneticization across diverse contexts. It asks: (1) What are the prevailing themes and trajectories in contemporary debates on geneticization? and (2) To what extent do Lippman’s original concerns remain relevant in the era of precision medicine, big data, and global genomics? By synthesizing insights from 25 recent studies, the review seeks to advance an updated, interdisciplinary understanding of geneticization as both a social process and an analytical framework for evaluating the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of modern genetics.

2 Materials and methods

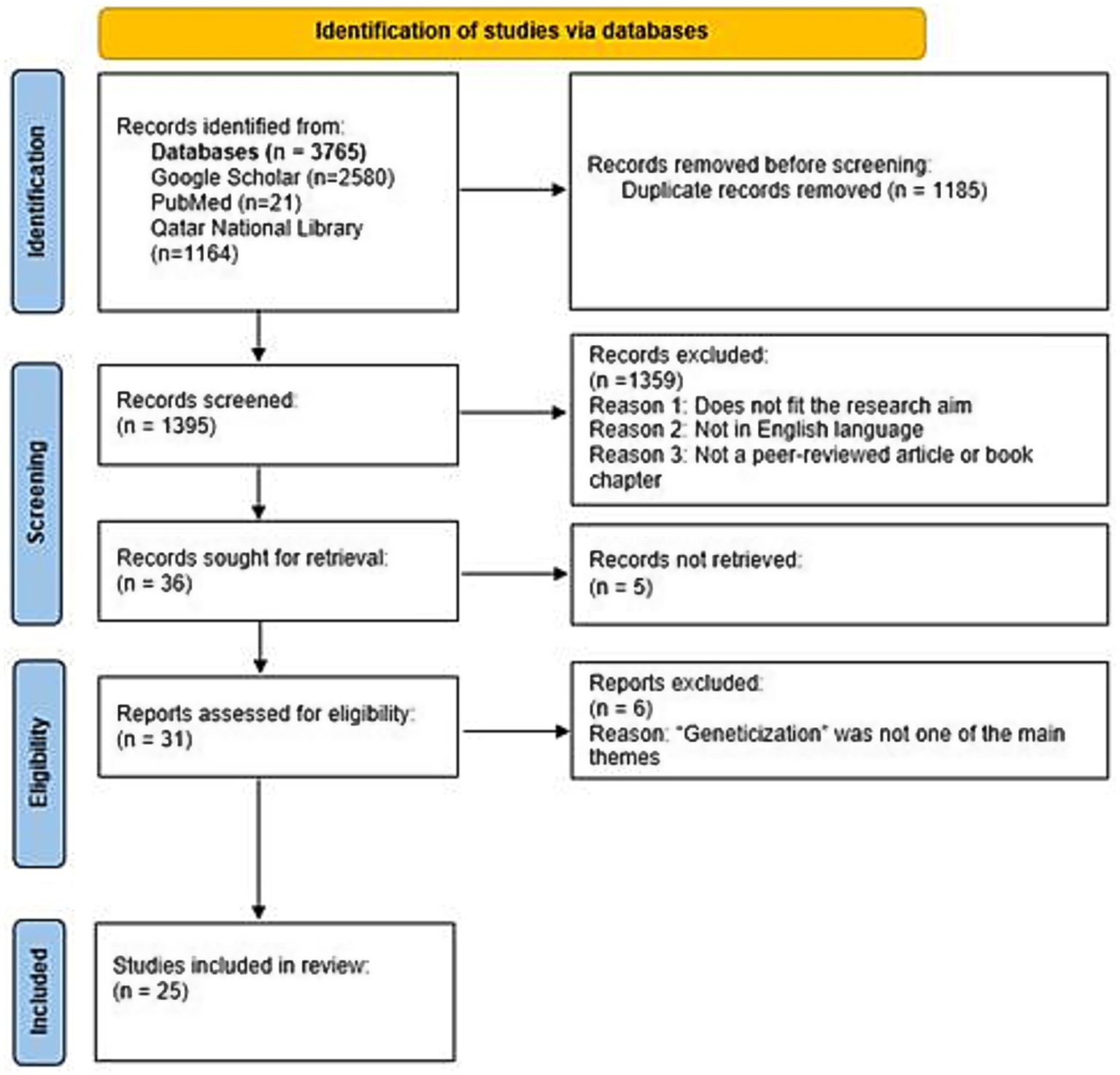

This study followed a scoping review design to map how the concept of geneticization has been defined, applied, and contested across sociology, bioethics, clinical medicine, and related fields. PRISMA-ScR guidelines were followed (Tricco et al., 2018) to ensure transparency, replicability, and rigor in the identification, screening, and selection of studies. A scoping review was selected because the literature on geneticization is conceptually diverse, spans multiple disciplinary traditions, and includes heterogeneous methods. The study selection process is presented using a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram adapted for scoping review purposes (Figure 1). In this review, the term “records” is used to refer to all initial sources identified during the search process, encompassing journal articles, book chapters, and other types of publications. As the review progressed, the term “studies” was applied more specifically to those peer-reviewed records that were screened, assessed for eligibility, and ultimately included in the review.

Figure 1

Geneticization literature review flow diagram (framework adapted from PRISMA 2020 flow diagram adapted for scoping review).

2.1 Search strategy

An in-depth and systematic search was carried out across several electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and digital collections accessible through the Qatar National Library. The search aimed to capture all relevant literature from January 2011 to December 2024. The terms used in the search strategy included the keyword variants: “geneticization” OR “geneticisation,” as both spellings are used interchangeably in the literature. These search terms were applied to the titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles to ensure comprehensive coverage. The search terms were used consistently across all databases utilized for the study.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To maintain a focused scope, studies were included based on the following inclusion criteria:

-

Articles published between 2011 and 2024.

-

Peer-reviewed publications in English.

-

Studies in which “geneticization” or “geneticisation” formed the central analytical or conceptual theme.

Studies were excluded if:

-

The term “geneticization” was only mentioned briefly or in passing.

-

The article did not engage with the theoretical, ethical, or social dimensions of geneticization in a substantive manner.

-

Full text was unavailable.

Because scoping reviews aim to map research rather than restrict it, no limitations on study design or methodology were imposed.

2.3 Screening and selection process

The initial search resulted in the generation of a total of 3,765 articles from the different databases such as Google Scholar (n = 2,580), PubMed (n = 21) and databases (around 200) accessible through Qatar National Library (n = 1,164). Following the removal of duplicate records (n = 1,185), a total of 1,395 records remained. These were screened for relevance to the research focus. A total of 1,359 records were excluded based on the following criteria: not in English language, not a peer-reviewed article or edited book chapter, or insufficient alignment with the core research questions. After this, 36 records remained which were searched for full text availability. Five full-text records could not be retrieved. The remaining 31 records—comprising 27 peer-reviewed journal articles and 4 book chapters, met the inclusion criteria and were assessed in detail for their contributions to the study’s focus on the concept of geneticization within the specified time period (see Figure 1). The relatively low number of results retrieved from PubMed likely reflects the disciplinary distribution of scholarship on geneticization. Since geneticization is a concept originating primarily within sociology, anthropology, STS, and bioethics, much of the relevant scholarship is published in journals outside the biomedical domain. As PubMed predominantly indexes biomedical and physical science literature, it returned comparatively fewer records than other databases. Furthermore, geneticization is not represented in PubMed’s controlled vocabulary—Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), which limits the sensitivity of keyword-based searches for conceptual or theoretical work. In contrast, Google Scholar and QNL databases employ broader full-text indexing and include social science journals, book chapters, and gray literature, resulting in a substantially higher number of retrieved sources. These disciplinary and indexing differences were taken into account when interpreting database yields.

Bibliographic references of selected studies were scanned to identify any additional relevant literature, but this did not result in any additions. Screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by the first author, while the second author reviewed and discussed uncertain or borderline cases. Any uncertainties or disagreements regarding the inclusion of studies were addressed through discussion between the two authors until consensus was reached; no third reviewer was involved at any stage of the screening or selection process. Microsoft Excel was used for record tracking, inclusion/exclusion decisions, and data visualization.

2.4 Data extraction and analysis

A detailed content analysis was then conducted. All 31 records were read multiple times, and a standardized data extraction table was developed by the first author to systematically capture key elements of each study, including research objectives, methodological approach, outcomes of interest, and other relevant details (see Table 1). This table facilitated structured comparison and synthesis across studies. Subsequently, backward citation tracking was employed, whereby the reference lists of the already included studies were systematically examined to identify additional relevant literature, but this did not result in the inclusion of new studies within the specified time frame. The second author reviewed and provided feedback on the data collection procedures, analytical process, and preliminary findings to enhance the reliability of the review. No formal risk-of-bias assessment was conducted, as scoping reviews aim to map the landscape of existing research rather than assess study quality.

Table 1

| Authors | Year | Type of record | Title | Research objectives | Methodology | Outcomes of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsekeris and Alexias | 2012 | Journal article | Science, genetic knowledge and the human body | To overview the intersection of geneticization and genetic counseling | Comprehensive critique of contemporary theoretical literature | Promotes critical thinking about being human and coping with genetic and bodily knowledge |

| Ankeny, RA | 2017 | Journal article | Geneticization in MIM/OMIM®? | Explores the evolution of MIM/OMIM® | Philosophical and historical analysis of MIM/OMIM® | The phenomenon of geneticization is not solely recent or always associated with genomic sequencing |

| Matthews, LJ | 2024 | Journal article | The geneticization of education and its bioethical implications | Examine the geneticization of education | Comprehensive critique of using Direct to Consumer (DTC) genetic testing for determining educational outcomes. | Explore both real and potential downstream bioethical implications and proposals for mitigating negative impacts |

Representation of data extraction form.

During the course of the content analysis, six records—5 journal articles and 1 book chapter, were excluded upon closer inspection since the concept of “geneticization” was not one of the main themes of the article or chapter—which is one of main criteria for inclusion. Although it is inherently challenging to guarantee that all relevant studies have been captured, the systematic approach adopted including iterative searching and citation tracking supports the conclusion that the review is sufficiently comprehensive and methodologically robust. We further categorized the studies into the 3 domains mentioned earlier (see Table 2 for included studies).

Table 2

| Category | Reference | Year | Title | Relevance/justification for inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociology, anthropology and culture | Tsekeris and Alexias (2012) | 2012 | Science, genetic knowledge, and the human body | Overviewed geneticization and its relevance to genetic counseling |

| Franklin (2013) | 2013 | From blood to genes? | Discussed consanguinity in the context of geneticization | |

| Arribas-Ayllon (2016) | 2016 | After geneticization | Reviewed and reconstructed the geneticization concept | |

| Hyun (2017) | 2017 | Geneticizing ethnicity and diet | Argued against geneticization of ethnicity and dietary habits in the context of anti-doping research | |

| Weiner et al. (2017) | 2017 | Have we seen the geneticisation of society? | Reviewed the literature on geneticization | |

| Dingel et al. (2019) | 2019 | “Why did I get that part of you?” | Studied geneticization of addiction as described by individuals in addiction treatment programs | |

| Strand and Källén (2021) | 2021 | I am a Viking! | Analyzed the construction of geneticized identity through the use of GATs | |

| Hunt and Merolla (2022) | 2022 | Genes and race in the era of genetic ancestry testing | Criticized the use of GAT for “the social deconstruction of whiteness” and thereby the geneticization of race | |

| Jacoby (2022) | 2022 | Commercially geneticizing race, ethnicity, and nation | Described the geneticization of race, ethnicity and identity through commercialized genetic tests | |

| Peters (2023) | 2023 | Racial-genomic interest convergence and the geneticization of Black families | Studied the geneticization of race | |

| Mannette (2021) | 2021 | Navigating a world of genes | Analyzed the concept of geneticization | |

| Shmidt and Donohue (2024) | 2024 | Invincible racism? | Criticized the geneticization of minoritized groups | |

| Ethics and bioethics | Domaradzki (2019) | 2019 | Geneticization and biobanking | Described the geneticization of identity through biobanking and related ethical aspects |

| Sharon (2014) | 2014 | New modes of ethical selfhood | Critiqued the geneticization thesis | |

| Roberts (2015) | 2015 | “good soldiers are made, not born” | Argued against geneticization of military ability and discussed the bioethical implications of the same | |

| Leźnicki (2020) | 2020 | Bioethical aspects of human geneticization | Discussed genetic enhancements and associated bioethical aspects | |

| Matthews (2024) | 2024 | The geneticization of education and its bioethical implications | Explained the geneticization of education and its bioethical implications | |

| Clinics and medicine | Pavone and Arias (2012) | 2012 | Beyond the geneticization thesis | Critiqued the geneticization of PGD/PGS in the context of Spain |

| Löwy (2014) | 2014 | How genetics came to the unborn | Described the geneticization of PND and in turn the geneticization of the unborn | |

| Navon and Eyal (2016) | 2016 | Looping genomes | Described the process of geneticization of autism | |

| Dekeuwer (2017) | (2017) | Conceptualization of genetic disease | Discussed the problem of geneticizing diseases | |

| Ankeny (2017) | 2017 | Geneticization in MIM/OMIM®? | Geneticization in Mendelian Inheritance cataloging | |

| Shim and Kim (2020) | 2020 | Contextualizing geneticization and medical pluralism | Situated the concepts of geneticization and medical pluralism within specific social, cultural, and institutional contexts to understand how they interact | |

| Alon et al. 2021 | 2021 | Regulating reproductive genetic services | Discussed the geneticization of human reproduction | |

| Löwy (2022) | 2022 | Precision medicine | Discussed the geneticization of clinics |

Studies included in the literature review.

3 Results

3.1 Evaluation of the geneticization concept

The theoretical foundation of geneticization lies at the intersection of genetics and social theory, particularly in its critique of the reductionist and deterministic assumptions often embedded in genetic discourse (Arribas-Ayllon, 2016). Lippman’s original thesis framed geneticization as a set of processes through which genetic explanations increasingly displace social, environmental, and structural determinants in the understanding of health and disease (Weiner et al., 2017). This trend has contributed to the emergence of what some scholars characterize as a dominant discourse of genetic determinism, wherein genetic traits are positioned as the primary factors shaping individual identity, behavior, and health outcomes (Arribas-Ayllon, 2016; Weiner et al., 2017). However, recent scholarship has complicated this narrative, suggesting that Lippman’s initial formulation may overstate the uniformity and dominance of genetic discourse. Rather than treating genetic knowledge as a monolithic force, these scholars emphasize the situated and context-dependent ways in which individuals interpret and engage with genetic information. They argue that lay understandings of genetics are often mediated by personal experience, cultural values, and social context, resulting in a plurality of meanings and applications. The following sections explore some of the key extensions and reinterpretations of the geneticization thesis that have emerged in recent years.

3.1.1 Enlightened geneticization

The concept of enlightened geneticization, introduced by Hedgecoe (2001b), represents a more nuanced iteration of geneticization—what he terms a “reasonable, non-extremist” position. This framing acknowledges the relevance of non-genetic factors but continues to prioritize genetic explanations as the primary causal mechanisms in understanding disease. Through a series of empirical investigations, Hedgecoe (2002), Hedgecoe (2001b), and Hedgecoe (2003) illustrates how the discourse surrounding conditions such as schizophrenia exemplifies enlightened geneticization, wherein genetic causality is foregrounded while non-genetic determinants are implicitly marginalized. In contrast, he describes the incorporation of genetic explanations into public health narratives around diabetes as a form of “geneticization by stealth,” a more gradual and understated integration of genetic framing. These distinctions underscore the evolution of geneticization from overtly deterministic models to more subtle, yet still hierarchical, representations of causality within biomedical discourse (Hedgecoe, 2002).

More recently, Dingel et al. (2019) have applied the concept of enlightened geneticization to the context of addiction, illustrating how individuals integrate genetic explanations into their personal narratives. Their study shows that individuals often adopt genetic framings of addiction to mitigate stigma, using notions of genetic predisposition as a way to legitimize their experiences and reduce feelings of personal culpability. This reframing allows for a more compassionate understanding of addiction, positioning it within a biomedical discourse that emphasizes inherited vulnerability rather than moral failure. The application of the enlightened geneticization thesis in this context reflects a broader shift toward integrated models of causation, where both genetic and non-genetic influences are acknowledged, albeit unevenly in shaping health and behavior. This case underscores the evolving societal discourse around identity, responsibility, and biomedical legitimacy in relation to addiction (Dingel et al., 2019).

3.1.2 Biological citizenship

The term “biological citizenship” was first introduced by Petryna (2002) in her ethnographic work, Life Exposed: Biological Citizens After Chernobyl, where she examined how individuals in post-disaster contexts negotiated medical care, legal recognition, and state support through claims rooted in biological harm. The concept was later elaborated by Rose and Novas (2005) in the context of genetic testing, healthcare access, and patient advocacy, where they argued that increasing engagement with genetic knowledge is reshaping how individuals conceptualize identity, responsibility, and health-related rights. Rose (2001) contended that individuals are increasingly called upon to act as biological citizens, exercising agency in relation to their genetic risks and health trajectories. Unlike enlightened geneticization, which retains a strong emphasis on genetic causality despite its acknowledgment of complexity, biological citizenship offers a more pluralistic framework. It situates genetic knowledge within broader social, cultural, and environmental contexts, enabling individuals to weave genetic information into their narratives of identity and belonging without reducing them solely to their biological components (Sharon, 2014). This shift reflects a growing recognition of the interplay between biosocial agency and technoscientific knowledge in shaping contemporary subjectivities.

In the earlier mentioned study by Dingel et al. (2019) on understanding addiction genetics through family history, they identified elements of both enlightened geneticization and biological citizenship within participants’ narratives. While both frameworks were evident, the authors argued that Rose (2001) notion of biological citizenship offered a particularly compelling lens for understanding these dynamics, owing to its flexibility and attentiveness to the multifaceted nature of identity. Their findings suggest that individuals construct personal identities that reflect a blending of genetic and non-genetic influences, situating biological risk within a broader context of social experience, family history, and cultural expectations. This process involved not only interpreting genetic predispositions but also responding to normative pressures regarding the management of genetic risk, particularly in relation to socially stigmatized conditions such as addiction. Thus, the study highlights the interplay between biomedical knowledge and lived experience, and the nuanced ways individuals negotiate responsibility, identity, and agency (Dingel et al., 2019).

3.1.3 Biosociality

The concept of biosociality, introduced by Rabinow (1997), refers to the ways in which emerging genetic technologies reshape traditional modes of social organization by fostering new forms of community and identity grounded in biological or genetic knowledge. Rather than social ties being based solely on cultural or familial norms, biosociality suggests that individuals may come to identify and affiliate with others based on shared genetic traits or risks. This framework has been critically examined by Rapp (1999) and Finkler (2000), who drew on ethnographic research to interrogate how DNA and genetic discourse are integrated into everyday life. Rapp (1999) argues that biomedicine employs specific discursive strategies that encourage individuals to internalize genetic categories and see themselves as part of emerging biosocial groups. Yet, these messages are not passively absorbed; they are filtered, resisted, or reshaped through various mediating influences, including religious beliefs, cultural traditions, social class, and ethnicity. Finkler (2000) critiques what she terms the medicalization of kinship, observing that biomedical narratives often privilege genetic relatedness over socially constructed forms of familial connection. In contrast to Rabinow’s vision of biosociality as generative of new, flexible kinship formations, Finkler contends that medical discourse may, in fact, constrain kinship definitions, reinforcing biological essentialism and marginalizing non-biological or chosen relationships, such as those established through marriage, adoption, or emotional bonds.

Biosociality is conceptualized as a framework that highlights the productive role of genetic markers in generating new social categories and affiliations (Arribas-Ayllon, 2016). Biosocial identities often emerge through the hybridization of traditional and novel identity categories, resulting in socially heterogeneous and context-dependent formations. Tsekeris and Alexias (2012) postulated that this concept illustrates the development of a biological sense of personal identity and social existence, enabling individuals to formulate genetic explanations of themselves and cultivate new relationships with figures of scientific and medical authority. Biosociality also gives rise to new modes of civic participation and activism, particularly among individuals affected by genetic conditions. These include efforts to challenge stigma and discrimination, advocate for improved access to medical information and healthcare services and mobilize for greater recognition of patient rights. In this way, biosociality is not merely a descriptive term but a lens through which to understand the dynamic interplay between genetics, identity, and collective action in contemporary biopolitical landscapes (Tsekeris and Alexias, 2012).

Biosociality, as articulated by Arribas-Ayllon (2016), extends well beyond the confines of the clinical setting, giving rise to new social assemblages that are formed outside traditional medical institutions. This challenges conventional notions of biomedicine as limited to anatomical depth and diagnostic authority, by emphasizing practices such as risk calculation, mutation identification, and genetic interpretation, which facilitate the creation of dynamic social networks. Genetic knowledge contributes to the formation of new subjectivities, as individuals and groups organize around shared genomic variants, constructing networks of associations that include categories, narratives, and expert-lay collaborations. In this context, patient organizations may coalesce around particular genetic conditions, providing not only access to medical expertise but also collective narratives, cultural traditions, and support structures that enable members to share experiences, advocate for intervention, and interpret their identities through a genetic lens (Arribas-Ayllon, 2016). Biosociality thus offers a robust framework for examining the evolving interplay between the state, scientific authority, community, and lay individuals, highlighting how genetic knowledge is productive of subjectivity and new forms of affiliation.

The rise of the Internet and digital health platforms has significantly shaped collective practices of genetic identification and knowledge exchange, enabling the formation of virtual communities centered around rare genetic conditions and specific mutations (Sharon, 2014). Sharon (2014) highlights the proliferation of websites, forums, and chat rooms that support nearly every known genetic disorder, offering patients, at-risk individuals, and caregivers spaces for information sharing, emotional support, and advocacy. These online communities serve as vital social and epistemic networks, where participants exchange personal experiences related to disease management, treatment navigation, and healthcare access. Moreover, they provide avenues for users to collaboratively interpret genetic risk, seek credible health information, and mobilize for policy or research advancements relevant to their conditions. Such interactions reflect the growing role of lay actors in co-producing genetic knowledge, thereby challenging traditional hierarchies of biomedical authority. As users gain scientific literacy and negotiate forms of distributed expertise, the boundary between experts, consumers, and producers becomes increasingly blurred (Sharon, 2014; Arribas-Ayllon, 2016). This shift not only empowers individuals but also reconfigures the relationship between patients and genetics professionals, positioning online communities as influential stakeholders in the broader genomic landscape.

3.2 Geneticization from a sociological dimension

3.2.1 Implications for race

The role of Genetic Ancestry Tests (GATs) in the geneticization of race and identity has been critically examined in recent scholarship (Roth and Lyon, 2018; Hunt and Merolla, 2022; Strand and Källén, 2021). In particular, Strand and Källén (2021) explore this phenomenon through individuals who used GATs to assert Viking ancestry, illustrating how genetic data is not simply accepted at face value but is actively interpreted and integrated into personal narratives. Their study introduces the notion of “geneticized identities,” which emerge at the intersection of objective genetic findings and subjective meaning-making processes. Participants constructed diverse and often imaginative understandings of what it means to be a Viking, ranging from traits like warlikeness to entrepreneurial spirit demonstrating how GATs serve as a flexible platform for identity formation. Rather than reinforcing static or essentialist notions of ancestry, these interpretations underscore the symbolic and aspirational dimensions of genetic information in contemporary identity practices (Strand and Källén, 2021).

The identities constructed through GATs are deeply shaped by socio-historical narratives surrounding groups such as the Vikings, often drawing on culturally embedded associations with strength, exploration, and entrepreneurial prowess (Strand and Källén, 2021). Individuals frequently map these traits onto their genetic results, interpreting biological ancestry through the lens of popular and historical representations. As a result, attributes like restlessness, aggression, or business acumen are sometimes attributed to so-called “Viking genes,” effectively naturalizing cultural stereotypes by presenting them as inherent biological characteristics. This process reflects how geneticized identities are co-produced through both scientific data and cultural imagination. Importantly, the cultural and racial context plays a critical role in shaping these interpretations. Studies have shown that claims to Viking ancestry are often entangled with notions of whiteness and Nordic exceptionalism, serving as a vehicle through which individuals assert social belonging or symbolic status (Ahmed, 2007; Strand and Källén, 2021). In this sense, the appeal of certain ancestral narratives may not only reflect personal identity exploration but also reproduce socio-political hierarchies, reinforcing racialized and Eurocentric ideals within contemporary frameworks of genetic belonging.

These processes of identity construction illustrate a broader trend in which genetic information becomes a central lens for understanding the self. The prominence of commercial GATs encourages individuals to interpret their DNA as authoritative markers of identity, sometimes leading to the disavowal of previously held cultural affiliations (Jacoby, 2022). This shift contributes to a broader cultural narrative in which genetic markers are positioned as the definitive source of personal truth, effectively eclipsing lived experience, social context, and cultural heritage. Jacoby (2022) critiques this discourse for reinforcing a biologically deterministic model of identity, which reduces the richness of human experience to genetic data, obscuring the socio-cultural and political dimensions that fundamentally shape how identity is constructed and maintained. The geneticization of identity, she argues, signals a significant transformation in how individuals conceptualize the self, raising critical concerns about authenticity, belonging, and the implications of genetic essentialism in an era of increasing reliance on biomedical frameworks for personal meaning (Jacoby, 2022).

A growing body of scholarship has highlighted the role of GATs in prompting individuals, particularly white Americans to reconsider and, in some cases, reconfigure their racial self-identifications based on genetic data (Roth and Ivemark, 2018; Roth and Lyon, 2018; Hunt and Merolla, 2022). In their study, Hunt and Merolla (2022) found that a significant number of white participants reported modifying their racial identities upon learning of previously unknown ethnic affiliations revealed through GATs. This phenomenon signals a broader shift in which genetic information begins to supplant conventional markers of identity, such as cultural heritage and familial narratives. Commercial GAT enterprises contribute to this dynamic by framing race and ethnicity as primarily biological constructs, thereby reinforcing essentialist views that stand in contrast to sociological understandings of race as socially constructed. These companies often promote the notion that identity can be distilled to genetic composition alone, prioritizing biological determinism over experiential and cultural dimensions of selfhood. Within this framework emerges the concept of the “social deconstruction of whiteness,” wherein white individuals adopt alternative ethnic labels derived from their GAT results as a means of distancing themselves from the undifferentiated category of “white” (Hunt and Merolla, 2022). While this repositioning may allow for the exploration of more complex ancestral narratives, it also raises critical concerns. Specifically, such re-identification occurs within a sociopolitical landscape that continues to confer systemic advantages upon whiteness. As such, this development reflects a problematic outcome of the geneticization of race and identity, whereby biological narratives can obscure or even reinforce existing racial hierarchies.

Beyond white identity reconstruction, Peters (2023) recently examined how GATs shape the construction of racial and ethnic identities among Black individuals and families. Central to this analysis is the concept of “racial-genomic interest convergence,” which underscores the mutual dependence between the GAT industry and Black consumers. This convergence reflects how Black individuals, seeking reconnection with African ancestry disrupted by historical violence, become integral to an industry that simultaneously commodifies Black identities and asserts narrative authority over Blackness. Peters (2023) critiques the assumption that GATs offer comprehensive identity reconstruction, arguing instead that Black ancestry often remains “necessarily unfinished.” This sense of incompletion contributes to deeper frustrations around Black identity, introducing new questions and reinforcing ethno-racial boundaries (Peters, 2023). GATs tend to elevate genetic connections over cultural or communal ties, thus narrowing the framework through which identity can be understood beyond genomic data. Advertising by GAT companies frequently promotes DNA as a definitive marker of identity (Putman and Cole, 2020), a message that may conflict with the lived realities of Black families, who often value non-biological conceptions of kinship and belonging (Peters, 2023). These findings underscore the ongoing complexities of how race and identity are negotiated through genomic technologies amid the persistent legacies of racial injustice.

3.2.2 Implications for ethnicity

Efforts to use genetic authority to define cultural and social identity have raised profound ethical and sociological concerns, particularly when applied to marginalized populations such as the Roma or the Romani people (Shmidt and Donohue, 2024). This is seen to be grounded in a sociobiological framework that assumes culture, behavior, and identity can be inferred from genetic traits, thereby advancing a racialist ideology that imposes static identities based on presumed biological differences (Cvorovic and Lynn, 2014). By this reductionist logic, stereotypes are reinforced and the political and social exclusion of minority groups are rationalized. Advocates of geneticization promote narratives that cast minorities as inherently deviant from dominant societal norms by interpreting cultural practices as genetically predetermined (Shmidt and Donohue, 2024). The resulting epistemic structure marginalizes more complex or contextual understandings of identity, favoring essentialist interpretations (Nguyen, 2020). Shmidt and Donohue (2024) contend that the fusion of sociobiology and race science continues to legitimize discriminatory practices against Roma communities, perpetuating structural inequality and stereotyping within both scholarly and public spheres. They call for a critical reassessment of these narratives, advocating for interdisciplinary engagement to disrupt the epistemic authority of geneticization and to challenge its detrimental impact on marginalized identities (Shmidt and Donohue, 2024).

The geneticization of ethnicity is also evident in anti-doping research, where biological determinism frequently overshadows social and cultural interpretation. Within this field, “ethnicity” is often conflated with race, allowing complex cultural identities to be reframed as biological variables (Hyun, 2017). This conflation facilitates interpretations of genetic variation as indicators of athletic potential or susceptibility to doping, rather than recognizing them within broader socio-cultural frameworks. A prominent example involves research on the UGT2B17 gene, which exhibits polymorphisms across ethnic groups. Findings from such studies have led to claims that certain ethnicities inherently possess biological traits affecting doping detectability, thereby positioning ethnicity as a genetic marker rather than a cultural identity (Hyun, 2017). Specifically, the deletion polymorphism of the UGT2B17 gene, found in approximately 66.7% of East Asians, has been framed in media discourse to suggest a genetic predisposition among Asian athletes to avoid detection, promoting the stereotype of East Asians as “born to cheat” (Hyun, 2017). This narrative is further complicated by associations between ethnic dietary habits and doping outcomes. For instance, compounds in green tea which is widely consumed in East Asia have been shown to inhibit UGT2B17 activity, potentially influencing testosterone levels and skewing testosterone/epitestosterone ratios. As a result, athletes from these backgrounds began altering culturally significant dietary practices to avoid suspicion, illustrating how genetic framing has pathologized cultural behaviors. Hyun (2017) argues that such interpretations reinforce essentialist assumptions by linking traditional diets to genetic predispositions for doping, ultimately framing ethnic identity through a narrow biological lens.

Media portrayals play a central role in perpetuating these simplifications. In particular, media portrayals of anti-doping studies frequently reduce complex findings to narratives that imply definitive racial or ethnic advantages, thereby reinforcing racial essentialism in the public imagination (Hyun, 2017). This distortion contributes to tangible consequences for athletes from specific ethnic backgrounds, fostering anxiety and prompting behavioral changes including reassessment of culturally significant dietary practices out of concern for how these might be perceived. Such representations obscure the nuanced interplay between culture and biology, instead advancing reductive views that equate ethnicity with genetic predisposition. In this context, the geneticization of ethnicity and diet within anti-doping science exemplifies how cultural identities are increasingly subsumed under frameworks of biological determinism.

3.2.3 Implications for kinship and community

The use of genetic testing, particularly in contexts like ancestry research, allows individuals to explore their familial connections in new ways, which indicates that genetics does not merely inform individual identity but also redefines social relationships. For instance, the proliferation of GATs has enabled individuals to explore familial connections in novel ways, extending kinship networks to include distant or previously unknown relatives. This phenomenon gives rise to what some scholars describe as a new form of genealogical realism, wherein biological data redefines familial structures and expands the parameters of relatedness (Finkler, 2000; Franklin, 2013; Peters, 2023). Such developments reflect a contemporary iteration of biosociality, characterized by the construction of relationships grounded increasingly in genetic ties rather than purely social bonds (Arribas-Ayllon, 2016). In clinical contexts, genetics has also been shown to medicalize kinship, particularly through the use of family pedigrees to assess hereditary risk (Finkler, 2005). Nevertheless, scholars such as Rapp (1999) argue that pre-existing social definitions of kinship often override genetic framings, suggesting that socially grounded ties can displace genetically derived ones. Similarly, empirical studies by Lock (2007) and Weiner (2011) reveal that lay responses frequently diverge from clinical expectations—individuals may downplay or disregard genetic links that fail to resonate with their lived experiences or relational understandings. These findings collectively highlight the tensions between genetic and social conceptualizations of kinship in both medical and everyday contexts. See Table 3 for summary of findings on geneticization from a sociological dimension.

Table 3

| Subtheme | Key findings | Representative studies |

|---|---|---|

| Race | Genetic Ancestry Tests (GATs) are reshaping racial identity by promoting biologically grounded understandings of belonging. Users interpret DNA results through cultural narratives (e.g., “Viking genes”), reinforcing whiteness and Eurocentric ideals while reconfiguring racial self-identification. | Strand and Källén (2021), Hunt and Merolla (2022), Jacoby (2022) and Peters (2023) |

| Ethnicity | Genetic authority is used to biologically define cultural groups (e.g., Roma communities), perpetuating stereotypes and exclusion. In anti-doping science, ethnicity is conflated with biology, producing essentialist narratives that pathologize cultural practices and diets. | Shmidt and Donohue (2024) and Hyun (2017) |

| Kinship and community | Genetic testing reconfigures social relationships, creating new forms of “biosociality” based on shared genetic information. Genetic frameworks medicalize kinship, but social understandings often resist purely biological definitions of relatedness. | Franklin (2013), Weiner et al. (2017), Peters (2023), and Arribas-Ayllon (2016) |

Summary of findings—geneticization from a sociological dimension.

3.3 Geneticization from a bioethical dimension

Ethical engagement with the process of geneticization aims to develop comprehensive frameworks to guide the responsible innovation and application of genetic technologies (ten Have, 2012). These ethical frameworks are informed by distinct national, cultural, and legal contexts, each reflecting specific moral values and rights-based discourses. Ethicists serve a crucial role in interrogating the broader implications of geneticization, assessing its effects across individual, institutional, and societal domains, and establishing normative criteria for the ethical acceptability of genetic interventions. Due to the intimate and sensitive nature of genetic data, policy development concerning its collection, use, and disclosure necessitates rigorous ethical and legal scrutiny (Shi and Wu, 2017). Within this landscape, bioethics operates both as an ideological force and as a mechanism for legitimizing biotechnological advances. It simultaneously functions as an evaluative lens, applying normative principles derived from dominant bioethical discourses to emerging genetic practices (Arnason and Hjörleifsson, 2007). To remain relevant, this discourse must be continually recalibrated to account for the multifaceted impacts of geneticization on both individual lives and social structures.

Ethical discourse surrounding geneticization often foregrounds the principle of individual autonomy as a foundational value (ten Have, 2012). Yet, this emphasis is increasingly complicated by state-led interventions that prioritize collective concerns such as public health or national security sometimes at the expense of individual rights (Gostin, 2000). In these scenarios, ethical considerations shift toward a model of collective responsibility, where the stewardship of genetic information involves a broad array of stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, genetic researchers, policymakers, and the public. The accelerated dissemination of genetic data via both traditional and digital media intensifies the ethical obligation to protect personal genetic information and to address potential harms. These concerns extend beyond individuals to encompass social groups and communities, highlighting the broader societal dimensions of genetic privacy and data governance.

Genetic information carries implications that extend well beyond the individual, potentially impacting family members, communities, social institutions, and, in certain contexts, entire nations. It may also be of considerable interest to third-party stakeholders such as insurers, employers, and law enforcement agencies. To address the ethical complexities of geneticization, ten Have (2001) introduced a four-level analytical model, comprising conceptual, institutional, cultural, and philosophical dimensions. This framework provides a structured approach for examining the multifaceted ethical considerations associated with the production and use of genetic knowledge. Expanding upon this model, Hedgecoe (2001a) highlighted the critical role of interdisciplinary engagement particularly among social scientists and philosophers across the first three levels. Such collaboration is essential for generating contextually nuanced and ethically sound responses to the evolving challenges posed by geneticization.

The development of genetic technologies frequently centers on the ideals of personalized medicine and individual autonomy in health management, often at the expense of acknowledging the profound influence of environmental and social determinants of disease (Brothers and Rothstein, 2015; Santaló and Berdasco, 2022). In response, mainstream bioethics must expand its evaluative scope to engage more critically with the process of geneticization, incorporating frameworks capable of addressing the broader societal ramifications of these technologies. This entails not only assessing their downstream effects but also interrogating the upstream ideological assumptions that shape their inception, design, and implementation.

3.3.1 Concerns regarding genetic discrimination and stigma

The discourses surrounding geneticization are embedded with substantial cultural and political implications. One key concern is the capacity of genetic information to shape social identities, raising ethical issues related to genetic discrimination and the potential reinforcement of racial and ethnic stereotypes. Genetic testing frequently employs ethno-racial classifications that risk conflating intricate social hierarchies with ostensibly objective genetic data. This conflation can influence individuals’ social positioning and affect how they navigate relationships within these socio-genetic frameworks (Jacoby, 2022).

The broader ethical concerns surrounding geneticization include its potential to reinforce existing stereotypes and biases, particularly against marginalized populations (Heredia et al., 2017). The risk of genetic discrimination where genetic data is misused to stigmatize individuals or groups contributes to the perpetuation of harmful narratives that shape and constrain identity formation (Domaradzki, 2019). As individuals increasingly interpret their identities through the lens of genetic information, there emerges a heightened vulnerability to internalized and social stigma, especially among those who are aware of a genetic predisposition to certain diseases.

The implications of geneticization become especially pronounced in institutional contexts, such as military recruitment, where the medicalization of performance through genetic and genomic assessments risks reducing complex human capabilities to predetermined genetic traits (Roberts, 2015). By emphasizing heredity over experience, training, and demonstrated competence, such practices echo historical eugenics discourses and reinforce social hierarchies, potentially valorizing biased models of aptitude along racial and gender lines (Roberts, 2015). These institutional applications underscore the urgent need to critically evaluate the ethical ramifications of embedding genetic determinism into frameworks that govern human evaluation and opportunity.

Ethical dilemmas also emerge in the context of genetic enhancements, which extend the logic of geneticization into the realm of human augmentation (Leźnicki, 2020). Distinctions between therapeutic interventions, aimed at treating disease, and non-therapeutic enhancements, intended to improve innate abilities, raise fundamental questions regarding the alteration of human nature. Bioethical debates often frame these concerns through contrasting perspectives: personalistic Christian ethics tend to reject modifications perceived as violating divine intent, while utilitarian approaches may support interventions that enhance well-being (Leźnicki, 2020). Echoing concerns from institutional applications of genetic data, the potential resurgence of eugenic thinking in enhancement practices could facilitate exclusion or marginalization of individuals with genetic impairments, further entrenching social inequality (Roberts, 2015; Leźnicki, 2020). Despite technological feasibility, resistance from bioethicists and restrictive legal frameworks continues to temper the advancement of enhancement-focused genetic research, highlighting the ongoing negotiation between scientific possibility and ethical responsibility.

3.3.2 Geneticization of education

The emerging geneticization of education represents a paradigm shift in how educational abilities and outcomes are conceptualized—one that increasingly attributes such characteristics to genetic determinants. This perspective, as described by Matthews (2024), draws an analogy to the process of medicalization: just as diverse human conditions have been reframed within biomedical frameworks, educational traits such as intelligence, mathematical aptitude, and reading proficiency are now being interpreted through the lens of genetic influence. In this context, geneticization implies a growing tendency to regard these traits as primarily encoded in DNA, thereby diminishing the perceived significance of pedagogical strategies, learning environments, and socio-cultural factors in shaping educational achievement.

The geneticization of education has progressed significantly over recent decades, particularly with the rise of genomic research and the widespread use of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which aim to identify specific genetic variants linked to educational outcomes such as mathematical ability, reading skills, and overall educational attainment (Rietveld et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2018). A pivotal shift occurred in the early 2000s, as researchers increasingly pursued genetic correlations of educational traits, marking a key turning point in the genetic framing of education. Matthews (2024) offers a critical perspective on this trend, emphasizing the limited predictive and explanatory power of these studies and raising concerns about the robustness of claims that position genetic factors as the primary determinants of educational achievement.

The geneticization of education carries significant implications that extend beyond the scientific sphere into bioethical considerations and broader societal consequences. Central concerns center on the potential for exacerbating educational inequalities and enabling discrimination grounded in perceived genetic predispositions. With the growing accessibility of DTC genetic testing, there is an increasing risk that parents and educators may develop biases based on assumptions about a child’s genetic potential. Matthews (2024) suggests such biases could shape parental expectations and educational strategies, thereby reinforcing a self-fulfilling prophecy in which children with lower genetic scores are afforded fewer opportunities and resources, entrenching existing patterns of disadvantage. See Table 4 for summary of findings on geneticization from a bioethical dimension.

Table 4

| Subtheme | Key findings | Representative studies |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical frameworks | Bioethics provides tools for evaluating the moral implications of genetic technologies but must evolve to address collective and societal concerns beyond individual autonomy. | Sharon (2014) and Roberts (2015) |

| Discrimination and stigma | Genetic information risks reinforcing racial and social stereotypes, legitimizing discrimination in institutional settings (e.g., military recruitment) and through enhancement debates. | Jacoby (2022), Roberts (2015), Domaradzki (2019), and Leźnicki (2020) |

| Education | Educational attainment and ability are increasingly geneticized through GWAS studies, diminishing recognition of socio-cultural influences. This trend risks exacerbating inequality and bias in educational systems. | Matthews (2024) |

Summary of findings—geneticization from a bioethical dimension.

3.4 Geneticization from a clinical dimension

The alignment between genotypic and phenotypic information frequently presents challenges, underscoring the inherent complexity of pathological classifications (Rabeharisoa and Bourret, 2009). This misalignment can generate psychological and social distress, largely stemming from the uncertainty surrounding disease probability. Nonetheless, genetic diagnosis may also empower individuals to pursue screening and preventive interventions, offering a means to potentially reduce the impact of genetic susceptibilities.

In this regard, the notion of genetic disease itself is increasingly contested. As virtually all diseases involve genetic components, the term risks losing specificity and meaning, potentially becoming universally applicable (Dekeuwer, 2017). This conceptual broadening raises what Dekeuwer (2017) terms the “causal selection problem”: the difficulty of determining which genetic factors should be regarded as primary contributors to disease, particularly in multifactorial conditions. This critique challenges simplistic models of genetic causation by foregrounding the intricate interplay between genetic and environmental factors. The concept of geneticization, often linked to deterministic and reductionist views of human life and behavior, may yield troubling social consequences such as the perception that genetic issues are best addressed through genetic selection, a view some interpret as implicitly eugenic (Dekeuwer, 2017).

The institutionalization of these perspectives within biomedical infrastructures further illustrates how geneticization becomes embedded in scientific practice. This trend is evident in the evolution from Mendelian Inheritance in Man (MIM) to Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), which reflects a broader shift toward molecular conceptualizations of disease. According to Amberger et al. (2015) and Ankeny (2017), OMIM has adopted stricter nosological criteria to navigate the tension between offering comprehensive genetic data and avoiding an excessively geneticized view of disease. Ankeny (2017) further argues that the institutionalization of MIM and OMIM as central tools in clinical genetics has entrenched a genetically centered framework for disease understanding and that the accessibility of these databases has amplified this geneticized perspective.

3.4.1 Geneticization effects on specific diseases

The social construction of autism has undergone a significant transformation, shifting from its initial framing as a psychiatric disorder grounded in behavioral and developmental paradigms to its contemporary classification as a genetically determined condition (Melendro-Oliver, 2004; Nadesan, 2013). Navon and Eyal (2016) argue that the genetic framing of autism has fostered the emergence of biosocial communities among parents and children, enabling shared genetic understanding to serve as a foundation for emotional bonding and collective identity This reframing has helped parents move away from experiences of blame toward a sense of shared identity and advocacy, allowing them to view themselves as “experts on their own children.” In doing so, they have articulated subjective interpretations of autism that reinforce their roles within these communities, which seek both care and societal recognition (Navon and Eyal, 2016). The use of genetic terminology establishes a discursive framework that enables individuals to articulate, represent, and, in doing so, construct and solidify autism as a distinct biosocial entity. The adoption of genetic terminology has also established a discursive framework through which autism is articulated and socially constructed as a distinct biosocial entity (Silverman, 2011). As genetic classifications of autism have become more prominent, diagnostic criteria have expanded, contributing to its current status as a spectrum disorder. This expansion has increased genetic heterogeneity and introduced new complexities into autism identities, demonstrating that geneticization interacts dynamically with evolving social perceptions and the fluid nature of biosocial identity (Navon and Eyal, 2016).

3.4.2 Geneticization of reproduction, genetic screening procedures, and medicine

The geneticization of reproduction has been characterized as a transformative shift in the application of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART), wherein the focus moves from addressing infertility to the active selection or engineering of embryos based on genetic traits (Alon et al., 2021). This shift carries significant ethical concerns, including the risk of fostering modern forms of eugenics, exacerbating social inequalities, and intensifying discrimination based on genetic characteristics (Asch and Barlevy, 2012; Alon et al., 2021). Within the context of reproductive genetic services (RGS), Alon et al. (2021) describe this process as encompassing the use of technologies such as Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT) to select embryos for specific traits, raising the prospect of human enhancement. This shift marks a transition from PGT’s initial focus on detecting severe, early-onset monogenic disorders to broader applications that include less severe, late-onset polygenic conditions, thereby expanding the scope and ethical complexity of genetic testing in reproduction (Klitzman et al., 2008; Batzer and Ravitsky, 2009). Alon et al. (2021) conclude that the geneticization of reproduction embodies a complex intersection of technological advancement, ethical considerations, and societal values, thereby posing substantial challenges for regulatory frameworks tasked with balancing individual reproductive autonomy against broader social consequences.

Closely related developments can be observed in the domain of prenatal diagnosis (PND), where the integration of genetic testing has fundamentally reshaped understandings of pregnancy and fetal health. The increasing association between PND and genetic evaluation, a process often described as the “geneticization of the unborn,” emerged during the 1960 and 1970s and transformed both medical practice and social perceptions of prenatal care (Löwy, 2014). While PND initially aimed to identify hereditary conditions within families, advancements in cytogenetics broadened its scope to include chromosomal anomalies such as those linked to Down syndrome (Löwy, 2014). The concept of “genetic abortion”- the termination of pregnancies based on the detection of fetal malformations gained prominence during this period, illustrating the expanding connection between PND and genetic frameworks, even in cases where conditions were not strictly genetic (Löwy, 2014).

A pivotal role was played in reinforcing the genetic framing of PND, by the emergence of genetic counselors as they became integral to guiding women through the complexities of prenatal testing, including deliberations regarding potential terminations (Stern, 2012). This development reflects the deepening integration of genetics into reproductive decision-making and underscores the ethical challenges inherent in the genetic discourse surrounding prenatal care. Consequently, the geneticization of PND represents more than an advancement in diagnostic capabilities; it marks a broader cultural transformation in how pregnancy, disability, and reproductive rights are understood and navigated (Löwy, 2014). This process of geneticization functioned to obscure the limitations of medical science in preventing or treating many congenital disorders, while simultaneously promoting an optimistic narrative centered on the promise of genetic science.

The social and institutional embedding of these technologies is further illustrated in the use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening (PGD/PGS) within fertility clinics. In Spain, for instance, the implementation of such technologies has received broad support among healthcare professionals, though their adoption is deeply influenced by the interplay of regulatory, economic, and cultural factors (Pavone and Arias, 2012). These mediating factors contribute to the broader process of geneticization more than the scientific or technological aspects and therefore a need to scrutinize these socio-institutional factors is highlighted more than the application of the technologies in the process of geneticization (Pavone and Arias, 2012).

The process of geneticization is seen not to be confined only to reproductive medicine but extends into the broader clinical landscape. In addition to the “geneticization of the unborn,” Löwy (2022) argues that a parallel “geneticization of the clinics” has occurred, particularly within the evolving paradigms of oncology, where genomic analysis has become a routine component of cancer treatment. This shift reflects a convergence of research and clinical care, effectively blurring traditional boundaries between the two domains (Cambrosio et al., 2018). The incorporation of genetic data into clinical practice introduces new organizational dynamics, offering the potential for personalized medical interventions while simultaneously raising concerns about the cost, equity, and accessibility of such treatments (Jones, 2013).

At a deeper epistemological level, the expansion of precision medicine reflects not only a technical shift but also the rise of a new scientific ideology. Drawing on Rheinberger (2013) conception of scientific ideologies as systems of thought that transcend empirical boundaries, precision medicine can be seen as a modern manifestation of the genetic ideal—one that offers hyperbolic representations of biological control while remaining partially detached from clinical reality (Löwy, 2022). By aligning precision medicine with this tradition, Löwy (2022) situates it within a broader historiographical context, prompting critical reflection on its epistemological and cultural implications for the fields of biology, genetics, and medicine.

The reach of geneticization extends even further when viewed through the lens of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine (TCAM). This has been explored by Shim and Kim (2020), who examined how genetic beliefs influence TCAM utilization across different national contexts. Their findings reveal considerable variation, with many countries outside East Asia exhibiting a strong negative correlation between genetic beliefs and the use of TCAM. Shim and Kim (2020) argue that these patterns are shaped significantly by institutional contexts, which mediate the relationship between belief systems and medical practices. In settings where TCAM is formally recognized as a legitimate and accessible component of healthcare, individuals who hold genetic beliefs are nonetheless more inclined to use TCAM (Shim and Kim, 2020). This indicates that geneticization is not solely a cognitive or conceptual transformation but is also contingent upon the broader medical and institutional structures within which individuals make health-related decisions. See Table 5 for summary of findings on geneticization from a clinical dimension.

Table 5

| Subtheme | Key findings | Representative studies |

|---|---|---|

| Disease classification | The definition of “genetic disease” has expanded, blurring distinctions between genetic and environmental causation. Databases like OMIM reinforce a genetically centered disease model. | Dekeuwer (2017) and Ankeny (2017) |

| Specific conditions (e.g., autism) | Autism’s framing has shifted from behavioral to genetic, fostering new biosocial communities and reshaping identity politics around neurodiversity. | Navon and Eyal (2016) |

| Reproduction and screening | Reproductive technologies increasingly focus on embryo selection and genetic screening, raising eugenic and social equity concerns. Geneticization extends to prenatal care and clinical practice. | Alon et al. 2021, Löwy (2022), and Pavone and Arias (2012) |

| Precision and alternative medicine | Precision medicine and TCAM illustrate how genetics penetrates diverse clinical paradigms, shaping both biomedical ideologies and complementary health practices. | Löwy (2022) and Shim and Kim (2020) |

Summary of findings—geneticization from a clinical dimension.

4 Discussion

This scoping review examined contemporary scholarly discourse on geneticization and assessed the extent to which Abby Lippman’s original critiques remain relevant in light of recent developments. The findings affirm that while the conceptual core of geneticization, i.e., the increasing attribution of health and identity to genetic factors persists, it has evolved into more nuanced and multidimensional frameworks across disciplines.

4.1 Geneticization: from determinism to nuance

Early critiques of geneticization, such as Lippman (1991) warning against reductionist and deterministic thinking remain foundational. However, recent studies suggest that contemporary discourse has moved beyond simplistic binaries. The works of Arribas-Ayllon (2016) and Weiner et al. (2017) have demonstrated that genetic explanations are now often embedded within more complex understandings that incorporate social, environmental, and psychological factors. The concept of enlightened geneticization exemplifies this shift, where genes remain central, yet are contextualized within broader causal networks (Hedgecoe, 2001b). This supports Weiner et al. (2017) conclusion that the original fears of total genetic determinism have only partially materialized, as modern accounts increasingly reflect dynamic, hybrid models of causation.

4.2 Social identity, race, and ethnicity

The review highlights that geneticization today extends far beyond clinical genetics into domains of social identity and race. The proliferation of GATs has played a critical role in reshaping how individuals understand and form their identities. While some users find empowerment in discovering genetic links to ancestral groups, others experience disorientation or loss of previously held cultural identities (Strand and Källén, 2021; Jacoby, 2022). This duality illustrates the productive yet potentially reductive nature of genetic information, which can both enrich and constrain identity narratives. Studies also indicate that geneticization can reinforce essentialist understandings of race, particularly when GAT results are interpreted as biologically determinative of cultural traits (Peters, 2023; Hunt and Merolla, 2022). The phenomenon of racial-genomic interest convergence and critiques of genetic reductionism in the case of Roma identity underscore the political and ethical stakes of geneticized identities in reinforcing existing hierarchies (Peters, 2023; Shmidt and Donohue, 2024).

The concepts of “biosociality,” “enlightened geneticization” and “biological citizenship” or “biocitizenship” highlight the growing significance of genetic and biological classifications in establishing community affiliations (Rabinow, 1997; Hedgecoe, 2001b; Rose, 2001). These frameworks illustrate how individuals increasingly identify and connect with particular groups based on shared genetic or biological traits, reflecting a broader transformation in the understanding of social belonging within contemporary society (Sharon, 2014). Such identities are rooted in the recognition and negotiation of genetic relationships, which facilitate new forms of community engagement and collective advocacy centered around biological identities. Moreover, these concepts facilitate the categorization of individuals or groups based on their patterns of interaction with genetic knowledge, allowing for a more context-sensitive and accurate characterization of their lived experiences and biomedical conditions.

4.3 Bioethical dimensions and ELSI

The ethical concerns first raised by Lippman remain highly relevant, particularly regarding autonomy, consent, and genetic discrimination. The review identifies a persistent gap between mainstream principlist bioethics and the sociocultural realities of geneticization, echoing critiques by ten Have (2001) and Arnason and Hjörleifsson (2007). As genetic knowledge becomes more accessible through media and DTC testing, ethical frameworks must evolve to address not only individual rights but also collective harms, particularly among historically marginalized populations (Roberts, 2015; Leźnicki, 2020; Shmidt and Donohue, 2024). The review also finds that stigma and selective disadvantage remain pressing issues. In areas like education and military recruitment, the integration of genetic frameworks has raised alarm over the potential to categorize individuals based on their presumed genetic potential (Roberts, 2015; Matthews, 2024). These trends reinforce the need for continuous ethical scrutiny and socially responsive policy development.

4.4 Clinical and reproductive contexts

In clinical and reproductive domains, the findings affirm that geneticization has become deeply institutionalized, particularly in areas such as the application of PND, PGT and precision oncology (Löwy, 2014; Alon et al., 2021; Cambrosio et al., 2018). As genomic tools become central to medical diagnostics and reproductive decision-making, the boundaries between medical care and technoscientific ideologies blur. While these tools enhance predictive capacities, they also contribute to the medicalization of reproduction and the geneticization of the unborn, raising ethical concerns about eugenics, informed consent, and social equity (Löwy, 2014). Moreover, developments such as OMIM exemplify how digital genomic repositories reinforce genetic framings of disease. As Ankeny (2017) notes, OMIM represents not just a shift in format but a transformation in how disease is conceptualized, placing genotype at the core of diagnosis and classification.

Previous studies have examined the extent to which conditions such as cystic fibrosis, mental illnesses, and breast cancer have undergone processes of geneticization. For instance, Phelan (2005) work on mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression highlights the increasing emphasis on genetic explanations, particularly through the lens of familial aggregation. This perspective is further supported by twin and adoption studies, which have consistently shown that genetic factors play a more significant role than non-genetic influences in the etiology of schizophrenia (Kendler and Diehl, 1993). Similar patterns are observed in autism research, with Navon and Eyal (2016) illustrating how genetic framings have come to dominate discussions of conditions previously not conceptualized in genetic terms. While this shift is not universally viewed as problematic, as Navon and Eyal (2016) acknowledge, concerns have been raised in specific contexts. In the case of breast cancer, for example, Sherwin and Simpson (1999) argue that the growing focus on genetic risk may marginalize environmental, nutritional, and broader social determinants of health, reflecting a key tension in the discourse on geneticization.

4.5 Cross-disciplinary tensions and global perspectives