- 1Bahir Dar University College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

- 2Debre Markos University College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

- 3Institute of Agricultural Economics and Development, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

Introduction: Onion (Allium cepa L.) production in Ethiopia is highly seasonal, while consumption remains year-round, creating critical mismatches between supply and demand. The crop’s perishability and limited storage capacity force farmers to sell quickly at low prices, driving market gluts and substantial postharvest losses. This study examines the determinants of onion production and postharvest losses along the supply chain in northwestern Ethiopia.

Methods: A multi-stage sampling strategy covered three districts (Fogera, North Mecha, and Bahir Dar Zuria) and six kebeles, yielding data from 167 producers, 30 wholesalers, 50 retailers, and 50 consumers, complemented by key informant interviews and field observations.

Results and discussion: Multiple linear regression models, validated for multicollinearity (VIF < 10) and heteroscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan test), revealed that male household headship (β = 1.561, p < 0.05), hybrid seed access (β = 4.40, p < 0.05), and land allocation (β = 16.49, p < 0.01) significantly increased production (R2 = 0.901). Conversely, education (β = −0.51 to −0.31, p < 0.1) and cooperative membership (β = −0.906, p < 0.1) reduced postharvest losses, whereas land size (β = 4.30, p < 0.01), future price expectations (β = 2.17–4.20, p < 0.1), and purchase volume (β = 1.55–4.43, p < 0.01 at wholesale) amplified them. These results highlight persistent gender disparities, input access gaps, and systemic storage constraints. Policy priorities include scaling hybrid varieties, upgrading storage technologies, strengthening cooperatives, and providing targeted capacity building and enhancing supply chain efficiency. Strengthening these areas will be pivotal for advancing sustainable food security and rural income resilience.

1 Introduction

Onion (Allium cepa L.) is an important bulb crop cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, which ranks second next to tomato (FAO, 2012). The onion bulbs are rich in minerals, carbohydrates, proteins, and vitamin C. It is also rich in powerful sulfur-containing compounds that are responsible for pungent odors and many of the health-promoting effects (Trivedi and Dhumal, 2013).

Therefore, high production and the maintenance of good-quality onion bulbs are critical for ensuring food and nutritional security, as well as improving farm income among onion farmers. In Ethiopia, onion is an important cash crop and is produced in various parts of the country by smallholder farmers for both local consumption and regional export markets (Lemma and Shimeles, 2003).

According to FAOSTAT (2019), global annual onion production was 99.97 million tons, with an average yield of 19.25 tons/ha. The Amhara region contributed 54% of the annual production, about 143,195.6 tons in the 2015/16 main season [Central Statistical Agency (CSA), 2015]. In north-western Amhara, particularly in Fogera, Dera Mecha, and Bahir Dar Zuria districts, onion production is rapidly expanding, and it continues to have a competitive advantage. During the 2017/18 production season, the area covered by onions in the Mecha district was 943.75 hectares with an average yield of about 18 tons per hectare, and in the Fogera district, 11,880.5 hectares with an average yield of 20.3 tons per hectare. Thus, there are opportunities to increase production and profitability in north-western Ethiopia.

Despite the available opportunities, the production and productivity of the crop in the country, including the Amhara region, are influenced by different factors (Habtamu Gudisa, 2017; Yeshiwas et al., 2023). There are a number of factors that limit onion production and productivity. These include: weak extension system, infestation of diseases and insect pests, non-organized marketing systems, fluctuation of climatic conditions, lack of infrastructure, imperfect price information, weak market linkage, poor handling of products, and high postharvest losses (Adewumi et al., 2009; Mateows et al., 2015; Giziew et al., 2014; Melese and Reddy, 2018; Etana et al., 2019; Yeshiwas et al., 2024b).

Onion production is seasonal, yet consumption remains relatively stable throughout the year (Mossie et al., 2020; Abrha et al., 2020; Yeshiwas et al., 2024a). The crop’s perishable nature, combined with a lack of proper storage technologies, compels farmers to sell their entire harvest immediately postharvest. This practice leads to a market glut and exacerbates postharvest losses. Effective onion preservation is complex, influenced by a confluence of pre- and postharvest factors including growth conditions, handling practices, temperature, humidity, and disease management (Falola et al., 2023; Petropoulos et al., 2017). Consequently, the final quality is determined by the interplay of genetic, environmental, and management factors across the entire value chain. Therefore, improving postharvest handling practices is critical for enabling large-scale and sustainable onion production.

1.1 Objectives

The main objective of this study is to examine the determinants of onion production and postharvest management practices along the supply chain in northwestern Ethiopia. Specifically, the study aims to identify and analyze the key factors affecting both production and postharvest handling, thereby providing evidence-based insights to guide farmers, policymakers, and other stakeholders in addressing production bottlenecks and ensuring a continuous and sustainable supply of onions to the market.

1.2 Research questions

To achieve the stated objective, the study is guided by the following research questions:

1. What are the key factors influencing onion production among smallholder farmers in northwestern Ethiopia?

2. What are the major determinants affecting postharvest management practices of onion along the supply chain?

3. How do production and postharvest factors interact to influence the efficiency and continuity of the onion supply chain?

2 Empirical literature review

The production and postharvest performance of onion cultivation in Ethiopia are constrained by various heterogeneous biophysical, institutional, and infrastructural factors. Recent studies confirmed across regions, limited access to quality seed, irrigation, fertilizer, and extension services remains a persistent production bottleneck (Ahmed et al., 2023; Shelema et al., 2024). Its postharvest losses, ranging from 25 to 40% stem largely from inefficient handling, poor storage, and weak market integration (Yeshiwas et al., 2023; Yimenu, 2024). The practice of irrigation management and input use optimization has shown measurable yield gains (Awulachew and Gebul, 2025; Zewdie and Yimer, 2023), yet smallholders’ economic and technical efficiencies remain modest. Collectively, the evidence underscores the need for context-specific, value-chain-wide interventions that integrate production efficiency, storage innovation, and market coordination to mitigate losses and enhance the sustainability of onion systems in Ethiopia (Table 1).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Description of the study area

The study was conducted in the Northwestern Amhara region, mainly with three potential onion-producing districts: Mecha district (Kudmi and Enguti kebeles), Fogera district (Shina and Kuhar Micael kebeles), and Bahir Dar Zuria district (Yigoma and Sebatamit kebeles; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the study area. Source: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.5/; Yeshiwas et al. (2023).

3.2 Sampling techniques and analysis

A multi-stage sampling procedure was employed to select study participants (Yeshiwas et al., 2019). In the first stage, two major onion-producing zones, namely South Gondar and West Gojjam, were purposively selected due to their high production potential. In the second stage, three districts, Fogera, North Mecha, and Bahir Dar Zuria, were purposively chosen from these zones as representative onion-growing areas. At the third stage, two kebeles with the highest onion production capacity and strong market linkages to national onion marketing centers were purposively selected from each district. In the fourth stage, onion-producing households within the selected kebeles were randomly sampled for household-level interviews. Finally, in the fifth stage, market actors, including wholesalers, retailers, and consumers in Bahir Dar, Woreta, and Merawi cities, were purposively selected based on their purchasing capacity and market influence.

In total, six kebeles were covered: Kudmi and Engutti (300 households), Shina (1,058 households), Quhar Micael (850 households), Yigoma (1,715 households), and Sebatamit (920 households). From these, a sample of 167 onion-producing households was randomly selected for the study using Yamane’s (1967) formula, ensuring a 5% precision level to optimize representativeness while maintaining feasibility. The proportional sample size was calculated as follows:

Using the sample size determination formula, a total of 167 onion-producing households were randomly selected and surveyed. To capture the broader dynamics of the onion supply chain, additional actors were included: 30 wholesalers, 50 retailers, and 50 consumers were interviewed in Bahir Dar, Woreta, and Merawi. The retailer sample encompassed roadside vendors, market stallholders, and other small-scale traders, while consumer respondents were randomly selected near major markets and asked about their experiences with onion quality, handling practices, and consumption behavior.

To complement the quantitative survey, qualitative data were collected through key informant interviews (KIIs). These were conducted with agricultural experts, extension agents, development officers, and market stakeholders. The KIIs provided institutional perspectives on production and marketing constraints, input access, and postharvest management, thereby enriching the analysis with insights beyond household-level responses.

To identify the determinants of onion production and postharvest losses, multiple linear regression models were employed and analyzed using STATA software version 14.0. Separate models were specified for farmers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers, as outlined in Equations 1–6.

3.2.1 Model diagnosis and selection

Before running the multiple linear regression analysis, the variables that were included in the model were checked for the existence of multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity problems. The multicollinearity problems associated with the explanatory variables were checked by using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). For continuous variables, variance inflation (VIF) is used to detect the problems of multicollinearity. The VIF values less than five are believed to have no problems related to multicollinearity/degree of association among independent variables (Johnston and Dinardo, 1997). Contingency coefficients for a high degree of association for discrete variables. If the VIF is greater than 10, the variable is said to be highly collinear (Gujarati, 2004). Consequently, the VIF for all explanatory variables is less than 10, which indicates that there is no serious multicollinearity problem among the explanatory variables included in the model estimation.

There are different approaches used to detect the existence of heteroscedasticity in linear model estimation. In this study, the problem of heteroscedasticity was checked by using the Breusch–Pagan test. Thus, before fitting important variables into the regression models for analysis, the heteroscedasticity and multicollinearity problems must be addressed; therefore, the data is free from such problems. The Breusch–Pagan Test is designed to detect any linear form of heteroskedasticity in a linear regression model and assumes that the error terms are normally distributed. It tests the null hypothesis that the error variances are all equal versus the alternative that the error variances are a multiplicative function of one or more variables.

3.3 Multiple regression model

3.3.1 farm-level of determinants of onion production

Where: is the dependent variable (onion production at the farm level), are vector (explanatory variables with beta coefficients), is estimated as a regression coefficient or unknown parameter, are explanatory/independent/ variables; such as; Age of the household head (rational numbers; AGEHH), the educational level of the household head (EL), sex of the household head (SHH), active household size (AFS), the experience in onion production years (FE), access to hybrid seed (AHS), lagged price (PRpkgC t-1), total land covered by onion in hectare (TLCO), production cost (in birr; PC), fertilizer amount (FA), membership in marketing cooperatives (MC), market information (MI) and ε = the random error term.

3.3.2 Farm-level determinants of postharvest of onion

Where: is the dependent variable (onion production at the farm level), are vector (explanatory variables with beta coefficients), is estimated regression coefficients or unknown parameters, are explanatory/independent/ variables; Age of the household head (rational numbers) (AGEHH), Sex of the household head (SHH), Active Household size(AFS), X4 is the experience in onion production years (FE), Total land covered by onion in hectare (TLCO), Membership in marketing cooperatives(MC), Market information(MI), Amount harvested (AH) and ε = the random error term.

3.3.3 Wholesaler-level determinants of postharvest handling of onion

Where: is dependent variables (onion production at the farm level), are vector (explanatory variables with beta coefficients), is estimate able regression coefficients or unknown parameters, are explanatory/independent/ variables such as; Age of the household head (rational number) (AGEHH), total household size (AFS), selling experience in years (FE), the educational level of the household head (EL), amount of onion bulb purchased (AP), days to finish selling (DFS), average quantity purchased (AVQPR), average quantity sold (AQS) and ε = the random error term.

3.3.4 Retailer-level determinants of postharvest handling of onion

Where: is the dependent variable (onion production at the farm level), are vector (explanatory variables with beta coefficients), is estimated regression coefficients or unknown parameters, are explanatory/independent/variables such as: total household size (AFS), marital status (MS), selling experience in years (FE), the educational level of the household head (EL), Amount of onion bulb purchased (AP), Days to finish selling (DFS), and ε = the random error term.

3.3.5 Consumer-level determinants of onion postharvest handling

Where: is the dependent variable (onion production at the farm level), are vector (explanatory variables with beta coefficients), is estimated regression coefficients or unknown parameters, are explanatory/independent/ variables such as: sex of the household head (SHH), household size (AFS), the educational level of the household head (EL), amount of onion bulb bought at a time (AP), and ε = the random error term.

3.4 Definition of variables and working hypothesis

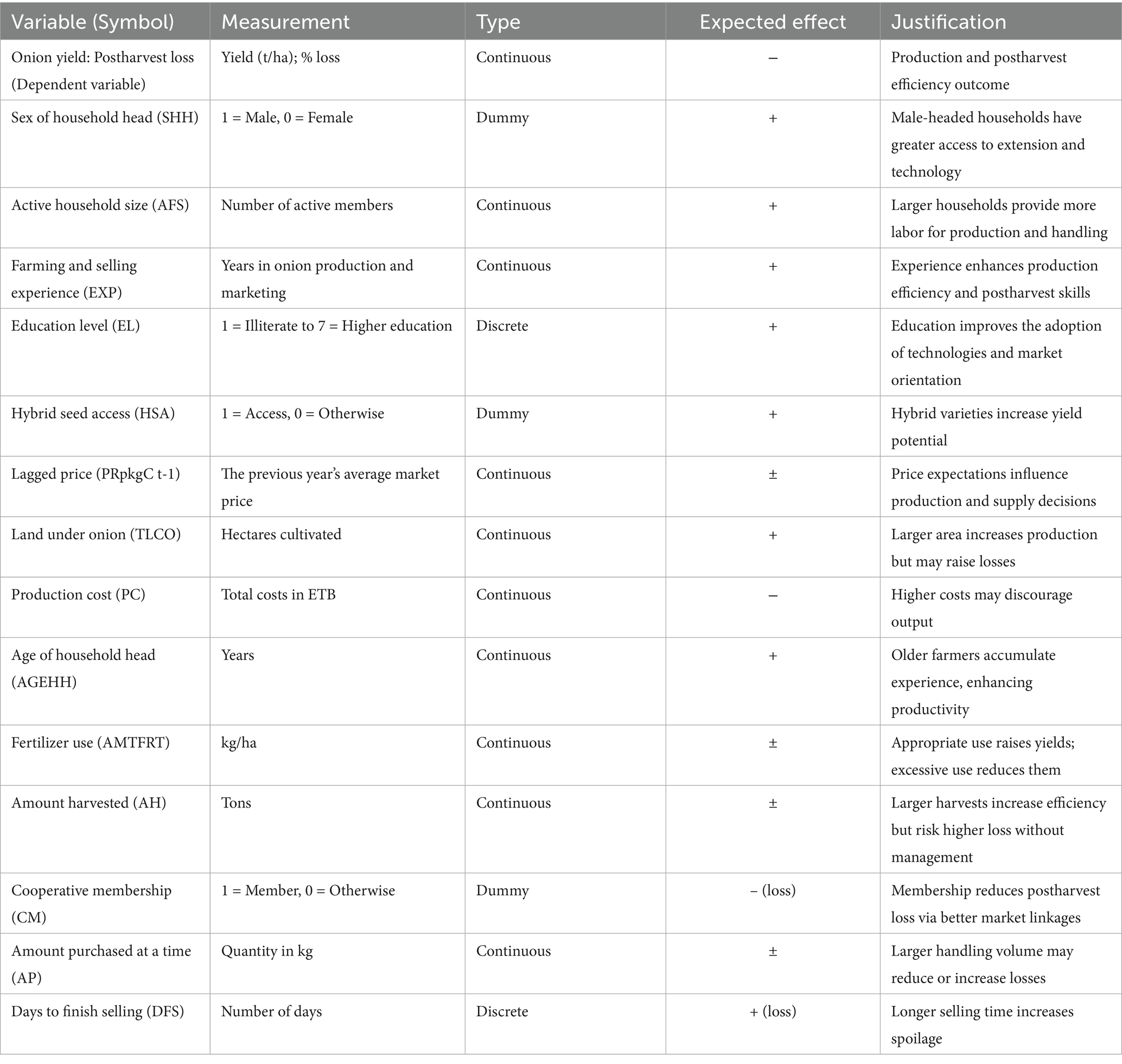

The dependent variables of the study are onion production and postharvest loss, both measured as continuous variables. Production is expressed as yield (tons per hectare) obtained per household during the 2023 production year, while postharvest loss is expressed as the percentage of total output lost after harvest (Table 2).

The explanatory variables were selected based on theory, previous empirical findings, and expert consultations. These variables represent demographic, economic, institutional, and technological factors hypothesized to affect onion production and postharvest management.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Production and productivity

The present survey result indicates that the average yield of onion in the study area was 16 tons/ha, which is higher than the Amhara National Regional State average (11.67 t/ha) reported by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2017). The result indicates the presence of a large onion production potential in the study area. The majority of producers in the study area produced below average per hectare. The reason for the low yield was due to the application of obsolete agronomic practices, lack of improved onion varieties, pests and diseases, poor access to inputs, and market linkages. The Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2019) reported that the average national yield of onion was 19.25 tons/ha, while in the Amhara region, it was 12.28 t/ha. This implies that onion productivity is affected by heterogeneous challenges and needs deep interventions. According to the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2019), in Ethiopia, onions are planted on 36.4 million hectares with a total production of 273,859 tons. The total onion production and the total cultivated area increased by 18.7 and 59.7% respectively, between 2015 and 2020. However, the productivity of onions declined by 25.7% over the same production period.

4.2 Demographic and socio-economic characteristics

This study examines the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of 167 onion-producing households in the study area, based on a 2023–2024 survey, with implications for productivity and market engagement.

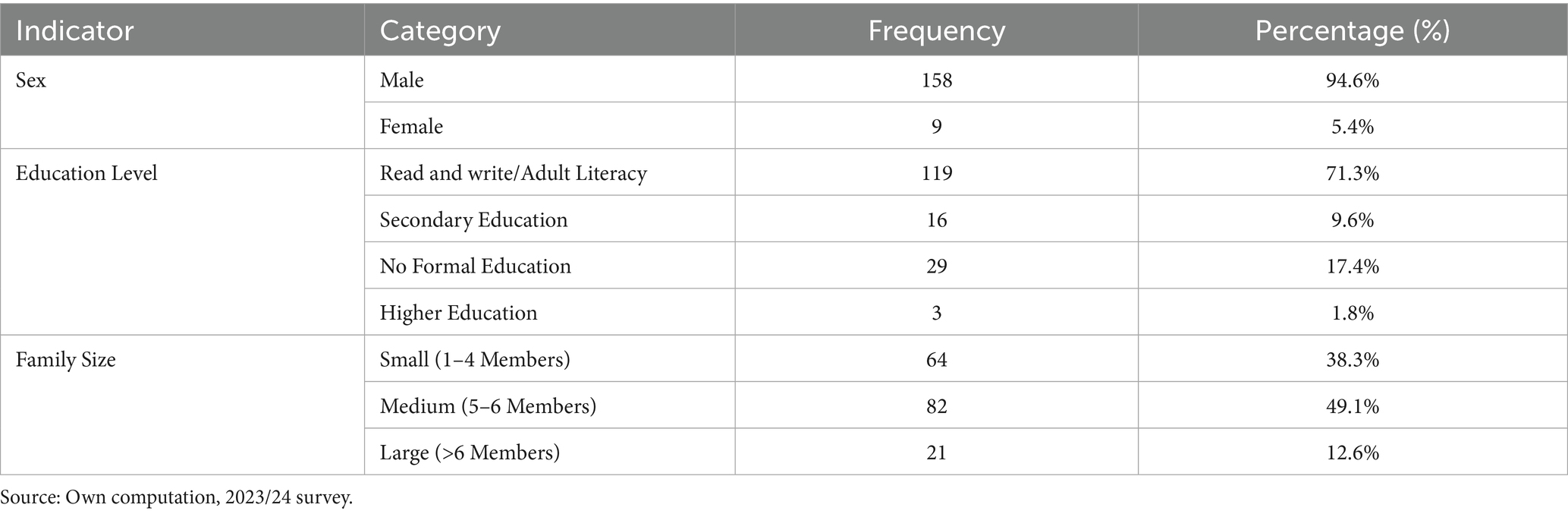

Gender and Labor Dynamics: Of the surveyed households, 94.6% are male-headed and 5.4% female-headed (Table 3). The labor-intensive nature of onion farming typically assigns male members tasks like land preparation and irrigation, while females focus on planting, weeding, and marketing. Gender-inclusive policies are essential for equitable resource access (Green and Ng’ong’ola, 1993; Mebratie et al., 2015).

Educational Attainment: Basic education (only read and write, local language Amharic) is attained by 71.3% of farmers, while 17.4% lack formal education, limiting adoption of modern practices (Table 1). Only 9.6% have secondary education, and 1.8% have higher education. Extension services could bridge this gap.

Family Size and Labor Availability: Medium-sized households (5–6 members) dominate (49.1%), followed by small (38.3%) and large households (12.6%; Table 3). Medium-sized households balance labor and dependency, while small households face labor shortages (Adisalem and Dinku, 2021).

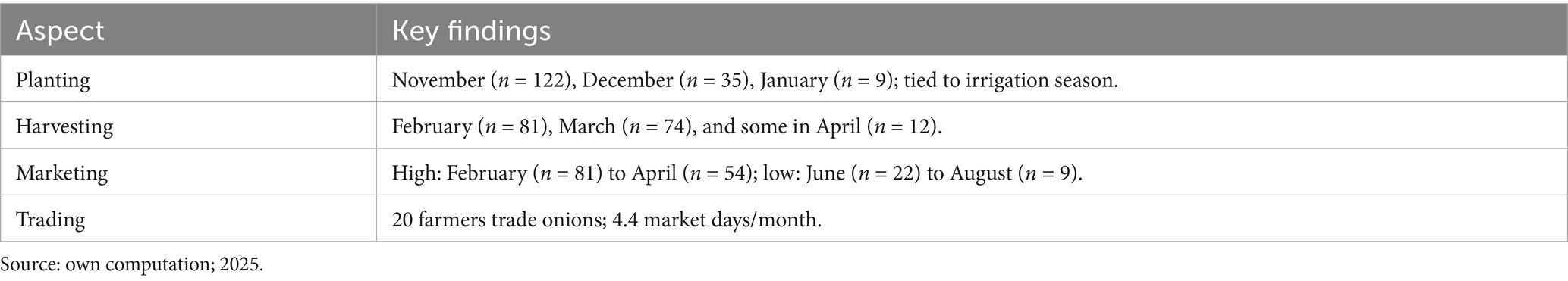

4.3 Onion production practices

Onion production in northwestern Ethiopia is highly seasonal and strongly tied to irrigation availability. The planting period peaks in November (n = 122), with only minor activity in December (n = 35) and January (n = 9). Harvesting is concentrated in February (n = 81) and March (n = 74), while marketing is strongest between February (n = 81) and April (n = 54). However, market supply declines sharply from June (n = 22) to August (n = 9), primarily due to inadequate storage technologies and the perishability of onion bulbs. This seasonal glut and subsequent scarcity not only limit farmer income but also destabilize market availability. Notably, only 20 farmers engage in direct onion trading, with an average of 4.4 market days per month, highlighting restricted market access and the dominance of intermediaries (Table 4).

These findings align with broader evidence that onion production in the region suffers from both pre-harvest and postharvest constraints. High perishability, limited access to improved storage and input supply, and weak marketing systems lead to substantial losses estimated at nearly 30% across the supply chain, with farmers bearing the highest proportion (35.5%; Yeshiwas et al., 2023). Strengthening postharvest technologies, cooperative-based marketing, and infrastructural investment are thus critical for stabilizing production cycles, improving farmer incomes, and ensuring consistent onion availability in local markets.

4.4 Major constraints to onion production: evidence from a farmer survey

The survey of 167 onion farmers, conducted in 2023/24, utilized a Likert scale to identify key constraints affecting onion production. The results, summarized in Table 5, highlight the prevalence and severity of various challenges, with implications for policy and agricultural development. Below, we discuss the major constraints, their impact on production, and potential interventions, ensuring alignment with high-quality journal standards.

High Cost of Inputs: The high cost of inputs, including fertilizers and pesticides, was the most significant constraint, with 67.1% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing (Table 5). This finding underscores the economic burden on smallholder farmers, whose limited financial resources restrict investment in productivity-enhancing inputs (Yeshiwas and Tadele, 2017; Yeshiwas and Tadele, 2021). High input costs reduce profit margins and discourage the adoption of modern farming practices, as noted by Adisalem and Dinku (2021) and Gelaye and Tadele (2022). Subsidies, credit facilities, or cooperative purchasing models could alleviate this constraint, enabling farmers to access essential inputs affordably.

Prevalence of Pests and Diseases: Pests and diseases were reported as significant constraints by 64.7 and 64.1% of farmers, respectively, highlighting their detrimental impact on onion yields. These biological challenges increase production risks and contribute to postharvest losses, as supported by Nisar et al. (2011). The shortage of insecticides/pesticides, noted by 56.3% of respondents, exacerbates this issue, limiting farmers’ ability to manage pest and disease pressures effectively. Integrated pest management (IPM) training and improved access to affordable, high-quality pesticides are critical to addressing this constraint.

Shortage of Quality Seeds: The shortage of quality seeds was a major barrier, with 58.7% of farmers acknowledging its impact. Access to high-quality, disease-resistant hybrid seeds is essential for improving yields and resilience to environmental stressors (Bishaw et al., 2011). The lack of reliable seed distribution systems limits productivity, particularly for smallholder farmers. Strengthening seed supply chains and promoting local seed production could enhance access to quality seeds.

Water Shortage and Low Irrigation Facilities: Water shortage and inadequate irrigation facilities were significant constraints, reported by 56.9 and 60.5% of respondents, respectively. In semi-arid regions, reliable water access is critical for onion production, which is highly sensitive to water stress. Limited irrigation infrastructure restricts farmers’ ability to cultivate onions during dry seasons, reducing both yield and quality (FAO, 2019). Investments in irrigation systems, such as drip irrigation, and water management training could mitigate these challenges.

Shortage of Storage: Postharvest storage shortages affected 58.7% of farmers, contributing to significant postharvest losses due to the perishable nature of onions. Inadequate storage facilities lead to spoilage, reducing marketable output and farmer income (Hodges et al., 2011). Developing affordable, accessible storage solutions, such as ventilated or cold storage units, is essential for improving postharvest management. In addition, the issue of storage losses, accounting for substantial loss of onion produce, ranges from 30 to 40% of total yield, arising from interconnected pre-harvest and postharvest factors such as irrigation, fertilization, maturity, curing, storage conditions, and packaging (Suravi et al., 2024).

Lack of Technical Training: Lack of technical training was reported by 49.1% of respondents, indicating limited exposure to modern agricultural practices. This knowledge gap hinders the adoption of efficient production and postharvest handling techniques. Enhanced extension services and farmer training programs focusing on best practices, such as crop rotation and IPM, could bridge this gap and boost productivity.

Other Constraints: Other constraints, including market access and transportation issues, were reported by 73.1% of farmers, reflecting systemic challenges in the onion value chain. Poor market linkages and infrastructure limit farmers’ ability to sell produce efficiently, leading to price volatility and reduced income (Gogo et al., 2017). Interventions such as digital market platforms and improved rural infrastructure could address these issues.

5 Discussion and policy implications

The identified constraints highlight the multifaceted challenges facing onion farmers, ranging from resource scarcity to systemic market inefficiencies. Addressing these issues requires a holistic approach, including targeted investments in irrigation and storage infrastructure, improved seed and input supply chains, and strengthened extension services. Policy interventions should prioritize subsidies or credit schemes to reduce input costs, along with training programs to promote sustainable practices. Strengthening cooperative systems and market linkages can further mitigate constraints related to market access and postharvest losses, aligning with the findings from Nigussie et al. (2015).

5.1 Econometric analysis

This section examines the key determinants influencing onion production and postharvest losses using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation technique. The analysis is based on cross-sectional data, which captures stronger associations between variables than causal inference. Consequently, the results should be interpreted as indicative relationships rather than causal effects.

5.1.1 Determinants of onion production

5.1.1.1 Interpretation of OLS results

The robustness of the model is supported by the use of robust standard errors, which mitigate heteroskedasticity issues, ensuring valid statistical inference. The absence of multicollinearity, as confirmed by the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis, indicates that the explanatory variables are independent, enhancing the reliability of the regression results.

5.1.1.2 Producers (onion production per hectare)

The ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results reveal key determinants of onion production at the farm level (Table 6). The model exhibits strong explanatory power with an R-squared value of 0.90, indicating that 90.0% of the variation in onion production per hectare is explained by the included explanatory variables. The model’s statistical significance is confirmed by the F-statistic and its corresponding p-value.

Among the explanatory variables, access to hybrid onion varieties significantly enhances production at the 5% significance level (β = 4.4, p < 0.05). Farmers with access to hybrid varieties produce, on average, 4.4 quintals more per hectare compared to those using local or open-pollinated varieties, holding other factors constant. This finding aligns with Bishaw et al. (2011), who noted that hybrid varieties can double yields due to their superior genetic traits. Land size allocated to onion production also has a highly significant impact at the 1% level (β = 16.49, p < 0.01), with an additional hectare increasing onion yield by 16.49 quintals, reflecting economies of scale. Additionally, the sex of the household head positively influences production at the 5% level (β = 1.561, p < 0.05), with male-headed households producing 1.561 quintals more per hectare than female-headed households, potentially due to greater labor availability and traditional gender roles prioritizing market-oriented production (Green and Ng’ong’ola, 1993; Mequanent, 2009; Giziew et al., 2014). While education level shows a positive coefficient (β = 2.43, p < 0.1), it is only marginally significant, suggesting that more educated farmers may adopt improved technologies, though the effect is less pronounced.

5.1.1.3 Postharvest loss at farm level

The regression model for postharvest loss at the farm level is highly significant, with an R-squared value of 0.89, indicating that 89.0% of the variation in postharvest losses is explained by the explanatory variables (Table 4). Education significantly reduces postharvest losses at the 10% level (β = −0.51, p < 0.1), with each additional year of schooling decreasing losses by 0.51%. This is consistent with findings by Garikai (2014), who highlight that education enhances knowledge of proper postharvest handling practices. Cooperative membership also mitigates losses at the 10% level (β = −0.906, p < 0.1), likely due to improved access to market information and collective bargaining power, as supported by MoARD (2010). Access to hybrid varieties significantly reduces losses at the 5% level (β = −4.857, p < 0.05), underscoring their role in improving yield stability and shelf life. Conversely, future price expectations increase losses at the 10% level (β = 2.172, p < 0.1), suggesting that speculative behavior leads to prolonged storage and spoilage, aligning with Kader (2005). Land size has a positive and highly significant effect on losses at the 1% level (β = 4.3, p < 0.01), indicating that larger cultivation areas increase losses by 4.3 quintals per hectare, likely due to challenges in managing higher yields without adequate storage or labor (Nisar et al., 2011; Wondim and Geyo, 2024).

5.1.1.4 Wholesaler-level losses

At the wholesale level, the regression model explains 17.9% of the variation in postharvest losses (R-squared = 0.18), with statistical significance confirmed by the F-statistic (Table 6). Education negatively affects losses at the 10% level (β = −0.36, p < 0.1), with each additional year of schooling reducing losses by 0.36%, consistent with Kader (2005) and Parfitt et al. (2010), who emphasize that education improves postharvest handling knowledge. Larger purchase volumes significantly increase losses at the 1% level (β = 1.55, p < 0.01), with each unit increase in quantity purchased raising losses by 1.55 quintals, likely due to handling and storage limitations (Debebe, 2022). Access to quality storage significantly reduces losses at the 10% level (β = −2.55, p < 0.1), supporting Hodges et al. (2011), who note that proper storage conditions are critical for perishable crops. Future price expectations exacerbate losses at the 10% level (β = 4.2, p < 0.1), reflecting inefficiencies from speculative holding, as delays in sales increase spoilage (Kader, 2005; Hodges et al., 2011).

Most postharvest losses occurred among wholesalers purchasing plantain/banana at the farm gate. Losses were significantly influenced by farm-to-market distance, market experience, storage duration, storage costs, and cooperative membership. To mitigate seasonal gluts and reduce losses, it is recommended that plantain marketers form effective cooperatives for local marketing and storage.

5.1.1.5 Postharvest loss at retailer level

The regression model for retailer-level postharvest losses has an R-squared value of 0.22, explaining 22% of the variation (Table 6). Education significantly reduces losses at the 10% level (β = −0.31, p < 0.1), with each additional year of schooling decreasing losses by 0.31%, as educated retailers adopt better handling practices (Debebe, 2022). Larger purchase volumes positively affect losses (β = 4.43, p > 0.1), though the effect is not statistically significant, suggesting that higher quantities may increase spoilage due to prolonged storage, consistent with Nigussie et al. (2015). Future price expectations significantly increase losses at the 10% level (β = 4.2, p < 0.1), as speculative holding leads to quality deterioration, aligning with Kader (2005) and Parfitt et al. (2010). Access to quality storage reduces losses at the 10% level (β = −0.46, p < 0.1), highlighting the importance of proper storage infrastructure (Gogo et al., 2017).

5.2 Econometric results of harvest loss for different actors (farm, wholesaler, and retailer levels)

The econometric results highlight substantial variation in harvest outcomes and post-harvest losses across the onion supply chain. At the farm level, production is strongly driven by access to hybrid varieties, land size, and household characteristics, while losses are primarily reduced by education, cooperative membership, and improved varieties. This indicates that both technological adoption and farmer capacity play central roles in enhancing productivity and reducing waste.

Along the marketing chain, wholesalers and retailers exhibit loss patterns shaped by handling capacity and expectations of future prices. Larger purchase volumes consistently elevate losses at both nodes, reflecting storage and logistical constraints. Education and access to quality storage remain critical in reducing losses, though their effects are modest relative to farm-level improvements.

The findings suggest that reducing post-harvest losses requires coordinated improvements in knowledge, storage infrastructure, and supply-chain efficiency across all actors, with the strongest leverage at the production stage.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

This study reveals that onion production and postharvest outcomes in northwestern Ethiopia are shaped by a complex interplay of demographic, socioeconomic, farm-level, and market factors. Regression analyses indicated that gender, education, access to hybrid seeds, landholding size, price expectations, and purchase volumes significantly influence both productivity and postharvest losses. Notably, poor handling practices and the crop’s inherent perishability were identified as primary drivers of losses, undermining farmers’ incomes and creating instability in local markets. These findings underscore the multidimensional challenges that smallholder farmers face along the onion value chain.

Addressing these challenges requires integrated, evidence-based interventions targeting both production efficiency and postharvest management. Promoting hybrid onion varieties, ensuring timely access to quality inputs and storage solutions, and strengthening cooperative structures can enhance market access, bargaining power, and value chain coordination. Simultaneously, adoption of improved postharvest practices such as sorting, grading, ventilated storage, and appropriate packaging, along with capacity building for farmers and other value chain actors, is essential to reduce losses and improve profitability.

Future research employing longitudinal or panel data designs is recommended to capture temporal dynamics and establish causal linkages between production factors and postharvest outcomes.

Such research should assess the long-term effectiveness of interventions, explore cross-regional differences, and incorporate climate-resilient strategies to further support sustainable production. Coordinated action among farmers, cooperatives, policymakers, and private stakeholders is critical for reducing postharvest losses, stabilizing markets, and fostering resilient onion value chains. By addressing these challenges holistically, stakeholders can enhance food security, strengthen rural livelihoods, and promote sustainable agricultural development in the region.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans. The requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin was waived because verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in interviews and surveys. This procedure is consistent with local ethical standards and was deemed sufficient by the institution.

Author contributions

YY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. MA: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. EA: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. ET: Writing – review & editing, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and data collection from Healthy Food Africa.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrha, T., Emanna, B., and Gebre, G. G. (2020). Factors affecting onion market supply in Medebay Zana district, Tigray regional state, northern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 6:1712144. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2020.1712144

Adewumi, M. O., Ayinde, O. E., Falana, O. I., and Olatunji, G. B. (2009). Analysis of post-harvest losses among plantain/banana (Musa spp.) marketers in Lagos state, Nigeria. Niger. J. Agr., Food Environ. 5, 35–38.

Adisalem, S. T., and Dinku, A. M. (2021). Determinants of inorganic fertilizer use by smallholder farmers in south Wollo and Oromia special administrative zones, Ethiopia. J. Agric. Ext. 25, 101–108. doi: 10.4314/jae.v25i4.11

Ahmed, Y. E., Senbeta, A. N., Bukul, B. B., and Dasalegn, S. G. (2023). Economic efficiency of onion production in east Shewa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 41, 39–52. doi: 10.9734/ajaees/2023/v41i11831

Awulachew, T. W., and Gebul, M. A. (2025). Effects of deficit irrigation and mulching on yield and water productivity of onion at Melkassa, Ethiopia. Air Soil Water Res. 18:11786221251342627. doi: 10.1177/11786221251342627

Bishaw, Z., Struik, P.C., and van Gastel, A. J. G. (2011) Wheat and barley seed system in Syria: farmers, varietal perceptions, seed sources and seed management. Int. J. Plant Prod. 5, 323–347.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2015). Agricultural Sample Survey Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency, Government of Ethiopia.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2017). Agricultural sample survey 2016/2017 (2009 E.C). Volume I report on area and production of major crops (private peasant holdings, Meher season). Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency, Government of Ethiopia.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2019). Area, production and productivity of major horticultural crops Meher season. Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency, Government of Ethiopia.

Debebe, S. (2022). Post-harvest losses of crops and its determinants in Ethiopia: tobit model analysis. Agric. Food Secur. 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40066-022-00357-6

Etana, M. B., Aga, M. C., and Fufa, B. O. (2019). Major onion (Allium cepa L.) production challenges in Ethiopia: a review. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 9, 42–47.

Etefa, O. F., Forsido, S. F., and Kebede, M. T. (2022). Postharvest loss, causes, and handling practices of fruits and vegetables in Ethiopia: a scoping review. J. Hortic. Res. 30, 1–10. doi: 10.2478/johr-2022-0002

Falola, A., Mukaila, R., Iı, R. O. U., Ajewole, C. O., and Gbadebo, W. (2023). Postharvest losses in onion: causes and determinants. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım ve Doğa Dergisi 26, 346–354. doi: 10.18016/ksutarimdoga.vi.1091225

FAO. (2012). Statistical year book food and agriculture organization. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. (2019). FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at: https://www.fao.org/faostat

FAOSTAT (2019). Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT database. FAOSTAT (2019). Rome, Italy: Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT database.

Garikai, M. (2014). Assessment of vegetable postharvest losses among smallholder farmers in Umbumbulu area of KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa (M.Agric. thesis). University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

Gelaye, Y., and Tadele, E. (2022). Agronomic productivity and organic fertilizer rates on growth and yield performance of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) in northwestern Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2022:2108401.

Giziew, A., Negatu, W., Wale, E., and Ayele, G. (2014). Constraints of vegetables value chain in Ethiopia: a gender perspective. Int. J. Advan. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 3, 44–71.

Gogo, E. O., Opiyo, A. M., Ulrichs, C., and Huyskens-Keil, S. (2017). Nutritional and economic postharvest loss analysis of African indigenous leafy vegetables along the supply chain in Kenya. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 130, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.04.007

Green, D. A., and Ng’ong’ola, D. H. (1993). Factors affecting fertilizer adoption in less developed countries: an application of multivariate logistic analysis in Malaŵi. J. Agric. Econ. 44, 99–109.

Habtamu Gudisa, (2017). Onion (Allium cepa L.) yield improvement progress in Ethiopia: a review. Inter J Agri Biosci 6, 265–271.

Hodges, R. J., Buzby, J. C., and Bennett, B. (2011). Postharvest losses and waste in developed and less developed countries: opportunities to improve resource use. J. Agric. Sci. 149, 37–45. doi: 10.1017/S0021859610000936

Hussen, S., Beshir, H., and Hawariyat, Y. W. (2023). Post-harvest loss assessment of commercial horticultural crops in south Wollo, Ethiopia: challenges and opportunities. Food Sci. Quality Manag. 17, 34–39.

Kader, A. A. (2005). Increasing food availability by reducing postharvest losses of fresh produce. Acta Hortic. 682, 2169–2176. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.682.296

Lemma, D., and Shimeles, A. (2003). Research experiences in onion production. Research report no. 55. Ethiopian agricultural research organization (EARO), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mateows, N., WoldeAmanuel, T., and Asfaw, Z. (2015). Market chain analysis of agro-forestry products: the case of fruit at Tembaro district, Kembata Tembaro zone South Ethiopia. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 4, 201–216. doi: 10.11648/j.ijber.20150404.13

Mebratie, M. A., Haji, J., Woldetsadik, K., Ayalew, A., and Ambo, E. (2015). Determinants of postharvest banana loss in the marketing chain of Central Ethiopia. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 37, 52–63.

Melese, T., and Reddy, P. C. S. (2018). Determinants of outlet choices by smallholder onion farmers in Fogera district Amhara region, northwestern Ethiopia. J. Hortic. For. 10, 27–35. doi: 10.5897/JHF2018.0524

Mequanent, M. (2009) Determinants of household food security and coping strategy: The case of Adaberga Woreda, west Shoa zone, Ethiopia. A thesis, Haramaya University, Ethiopia.

MoARD. (2010). Ethiopia’s agricultural and sector policy and investment framework (PIF): Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, 2010–2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Mossie, H., Berhanie, Z., and Alemayehu, G. (2020). Econometric analysis of onion marketed supply in Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 6:1733329. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2020.1733329

Nigussie, Y., Kuma, A., Alemu, T., and Desalegn, K. (2015). Onion production for income generation in small scale irrigation users agropastoral households of Ethiopia. J. Hortic. 2, 1–5. doi: 10.4172/2376-0354.1000145

Nisar, M., Ali, S., and Qaisar, M. (2011). Preliminary phytochemical screening of flowers, leaves, bark, stem and roots of Rhododendron arboreum. Mid-East J. Sci. Res. 10, 472–476.

Parfitt, J., Barthel, M., and Macnaughton, S. (2010). Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transact. Royal Society B: Biological Sci. 365, 3065–3081. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0126,

Petropoulos, S. A., Ntatsi, G., and Ferreira, I. C. F. R. (2017). Long-term storage of onion and the factors that affect its quality: a critical review. Food Rev. Int. 33, 62–83. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2015.1137312

Shelema, A., Hruy, G., and Mengesha, B. (2024). Farm partial budget analysis of onion (Allium cepa L.) for the application of nitrogen and spacing in southern Tigray, Ethiopia. Asian J. Agric. Hortic. Res. 11, 109–116. doi: 10.9734/ajahr/2024/v11i2318

Suravi, T. I., Hasan, M. K., Jahan, I., Shopan, J., Saha, M., Debnath, B., et al. (2024). An update on post-harvest losses of onion and employed strategies for remedy. Sci. Hortic. 338:113794. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113794

Trivedi, A. P., and Dhumal, K. N. (2013). Effect of soil and foliar application of zinc and iron on the yield and quality of onion (Allium cepa L.). Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 38, 41–48. doi: 10.3329/bjar.v38i1.15188

Wondim, M. T., and Geyo, G. B. (2024). Determinants of commercialization among onion producer households in southern Ethiopia: a double hurdle approach. Front. Environ. Econ. 3:1443921. doi: 10.3389/frevc.2024.1443921

Yeshiwas, Y., Alemayehu, M., and Adgo, E. (2023). The rise and fall of onion production; its multiple constraints on pre-harvest and post-harvest management issues along the supply chain in Northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 9:e15905. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15905,

Yeshiwas, Y., Alemayehu, M., and Adgo, E. (2024a). Strategic mapping of onion supply chains: a comprehensive analysis of production and post-harvest processes in Northwest Ethiopia. Front. Sustain. 5:1387907. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1387907

Yeshiwas, Y., Alemayehu, M., and Adgo, E. (2024b). Enhancing bulb yield through nitrogen fertilization and the use of hybrid onion (Alluim cepa L.) varieties in Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 19:e0312394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0312394,

Yeshiwas, Y., and Tadele, E. (2017). Review on heavy metal contamination in vegetables grown in Ethiopia and its economic welfare implications. J. Biol. Agricul. Healthcare 7, 31–44.

Yeshiwas, Y., and Tadele, E. (2021). An investigation into major causes for postharvest losses of horticultural crops and their handling practice in Debre Markos, North-Western Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. doi: 10.1155/2021/1985303

Yeshiwas, Y., Tadele, E., and Workie, M. (2019). Utilization, cultivation practice and economic role of medicinal plants in Debre Markos town, east Gojjam zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plant Res. 13, 18–30. doi: 10.5897/JMPR2018.6704

Yimenu, S. M. (2024). Identification of postharvest loss determinants of small-scale onion farm holders in lode Hetosa District of Arsi zone, Ethiopia. Arsi J. Sci. Innovation 3, 1–28. doi: 10.20372/nchq-1887

Zegeye, M. B., Alemu, T. A., Sisay, M. A., Mulaw, S. G., and Abate, T. W. (2024). Factors affecting onion production: an empirical study in the Raya kobo district, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. PLoS One 19:e0305134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0305134,

Keywords: onion, supply chain, production, postharvest loss, storage technology, hybrid seed, value chain

Citation: Yeshiwas Y, Tadele E, Adgo E and Alemayehu M (2025) Heterogeneous production constraints and postharvest losses in onion farming: evidence from Northwest Ethiopia. Front. Sustain. 6:1697487. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1697487

Edited by:

Santanu Kumar Ghosh, Kazi Nazrul University, IndiaReviewed by:

Porfirio Gutierrez-Martinez, Instituto Tecnológico de Tepic, MexicoBikash Koli Dey, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, India

Arne Nygaard, Campus Kristiania, Norway

Copyright © 2025 Yeshiwas, Tadele, Adgo and Alemayehu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yebirzaf Yeshiwas, eWViaXJ6YWZ5X3llc2hpd2FzQGRtdS5lZHUuZXQ=

Yebirzaf Yeshiwas

Yebirzaf Yeshiwas Esubalew Tadele

Esubalew Tadele Enyew Adgo

Enyew Adgo Melkamu Alemayehu

Melkamu Alemayehu