- 1Department of Sociology, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2Department of Sociology, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia

- 3Department of Fisheries and Marine Socio-Economics, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia

Introduction: Lakes in mining regions face critical threats from environmental degradation and bureaucratic complexities spanning multiple levels of government. Despite this urgency, the role of local governments as intermediaries between central government regulations, mining corporate interests, and local community needs remains poorly understood. This study examines local government mediation roles in environmental governance at Lake Matano, East Luwu, Indonesia.

Methods: The research, conducted during July 2025, employed semi-structured interviews with eight key informants comprising government officials and community leaders, complemented by document analysis and participatory observation.

Results: The findings reveal that environmental management authority remains fragmented across central, provincial, and district governments, creating jurisdictional overlap and weak coordination mechanisms. In response to this governance vacuum, local communities have developed autonomous management systems through grassroots initiatives. Local governments have demonstrated their capacity to serve as effective mediators, reconciling diverse stakeholder interests through trust-based persuasive approaches and dialogue rather than relying solely on formal regulatory enforcement. These findings introduce a novel conceptualization of local government as a “social weaver,” integrating formal legal frameworks with community acceptance and legitimacy.

Discussion: The study identifies three critical imperatives: strengthening inter-agency coordination mechanisms, formally recognizing local initiatives, and enhancing local government mediatory capacities. This research concludes that preserving lake ecosystems in mining regions requires more than regulatory reform alone. Success depends fundamentally on local governments’ ability to balance environmental protection, social justice, and economic interests within an integrated framework. The sustainability of these ecosystems ultimately hinges on developing governance approaches that harmonize competing demands while maintaining ecological integrity.

1 Introduction

Freshwater lake ecosystems worldwide are experiencing severe degradation driven by the combined effects of climate change and exploitative economic activities. Rising global temperatures have triggered hydrological fluctuations that accelerate eutrophication, sedimentation, and biodiversity loss in inland waters (Pörtner et al., 2022). More than half of the world’s major natural lakes have shrunk dramatically since 1992, a volume equivalent to seventeen times that of Lake Mead in the United States (UNEP, 2023). Simultaneously, industrial growth and urbanization continue to degrade watersheds, particularly in developing countries with limited management capacity (FAO, 2021; World Bank, 2024). Lake management challenges extend beyond ecological dimensions to encompass institutional complexities, where overlapping authorities and inadequate inter-agency coordination impede adaptive responses. These conditions necessitate more flexible and participatory governance models that transcend administrative and sectoral boundaries.

Southeast Asia has become the region most affected by water resource management crises, experiencing rapid industrialization amid environmental vulnerabilities. Over 40 percent of lakes in ASEAN countries suffer from deteriorating water quality due to mining waste, deforestation, and uncontrolled tourism (UNESCO, 2022). Indonesia faces additional challenges from its decentralized system that fragments environmental authority among central, provincial, and district governments (Hidayat et al., 2025). Under Presidential Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No. 60 of 2021 on the Rescue of National Priority Lakes, major lakes such as Toba, Poso, and Matano are designated as strategic areas where conservation agendas intersect with mining permits, energy projects, and local economic needs. The regulation also identifies at least 15 lakes in Indonesia as critical, requiring urgent and integrated management efforts. Harmonizing environmental conservation with economic growth demands synergy across governmental levels—a formidable challenge within Indonesia’s autonomous system, where local governments bear responsibility but possess limited capacity.

Beyond biophysical dimensions, lake sustainability is influenced by complex institutional structures and political dynamics. Extensive research demonstrates that management failures stem more from overlapping authorities, weak coordination, and tokenistic community participation than from insufficient scientific data (Pahl-Wostl, 2019; Wang et al., 2020). When power disparities persist, fragmented policies exacerbate social vulnerabilities and trigger resource conflicts (Roy et al., 2024; Biedenkopf, 2022; Syam, 2025). In resource-rich regions with weak institutions, environmental management often becomes an arena for political competition rather than ecological cooperation. Governance vacuums are subsequently filled by informal actors through creativity and everyday social activities (Spanuth and Urbano, 2024; Anderson et al., 2023). This study argues that understanding these hybrid spaces requires perspectives that transcend technocratic-managerial approaches, moving toward comprehending how actors negotiate legitimacy, authority, and meaning within contested socio-ecological spaces.

Over the past decade, water governance research has evolved through concepts of collaborative management, polycentric governance, and stakeholder engagement (Schmidt and Fleig, 2018; Prutzer et al., 2021; Clarke-Sather et al., 2017; Shunglu et al., 2022; Adams et al., 2018; Cisneros, 2019; Santos, 2025). Studies of mining-affected lakes typically focus on environmental degradation and corporate social responsibility while overlooking mediation processes that enable conservation-extraction coexistence (St-Gelais et al., 2018; Yasmin et al., 2022; Robinson et al., 2023). Research on local governments in environmental management emphasizes administrative aspects rather than negotiation functions (Li et al., 2016; Zhu and Tang, 2018). While collaborative management studies highlight cooperation, they overlook how local governments integrate diverse regulatory regimes, local norms, and market mechanisms within hybrid socio-ecological systems. Consequently, empirical studies examining local governments as institutional mediators in state-market-community relations, particularly in mining-lake regions of developing countries, remain scarce. This research addresses that gap.

This study employs two principal concepts: hybrid environmental governance (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006) and institutional mediation (Crona and Parker, 2012). The first concept views environmental management as a joint product of state, private, and community actors operating through combinations of formal and informal rules. Authority is distributed yet interconnected, requiring negotiation and trust rather than hierarchy. The second concept emphasizes the role of intermediary actors—particularly local governments—in translating and linking diverse governance logics across scales. Integrating both perspectives, this article positions local government as “social weavers” that cultivate cohesion amid fragmented governance by bridging formal legality and community norms. This approach enables in-depth analysis of mediation as both a political and socio-ecological process supporting collective action within institutional pluralism.

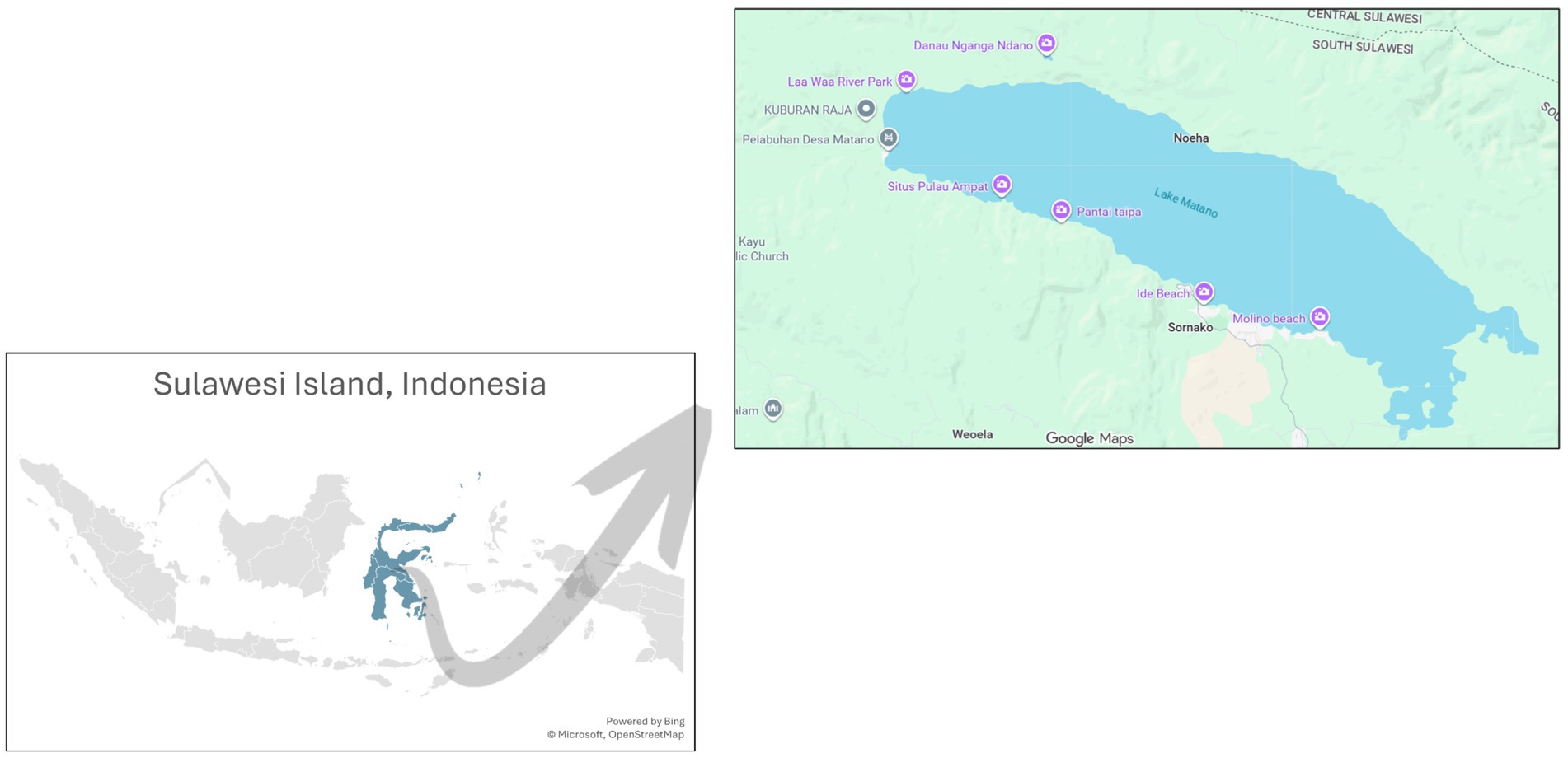

Lake Matano in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, represents Indonesia’s deepest lake ecosystem—pristine yet politically complex. As part of the Malili Lake Complex (comprising Lakes Matano, Mahalona, and Towuti), this region possesses high ecological value and holds Nature Tourism Park status under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The lake borders PT Vale Indonesia’s nickel mining area, creating a unique intersection between conservation and extraction. Administratively, the region falls under multiple jurisdictions—central conservation authorities, provincial water agencies, district government, and villages—each holding partial mandates over land, water, and livelihoods. Indigenous Padoe-Mori and Matano communities coexist with migrants, forming a blend of traditional and modern institutions. This complexity makes Lake Matano an ideal site for examining how local governments navigate relationships among national regulations, corporate interests, and community practices within hybrid environmental governance.

To address the identified research gap—the scarcity of empirical studies on local governments as institutional mediators—this research adopts a three-pronged analytical strategy. Understanding mediation requires first comprehending the governance context that necessitates mediation, then identifying the diverse practices and interests that must be reconciled, and finally examining the actual mediation mechanisms employed. Accordingly, this research pursues three objectives: (1) analyzing authority fragmentation in Lake Matano management, which establishes the institutional context that creates the need for mediation; (2) exploring local initiatives that function as practical environmental management, which reveals the informal governance practices that mediators must integrate with formal regulations; and (3) explaining local government’s role as a multi-level mediator in balancing conservation and development, which reveals the informal governance practices that mediators must integrate with formal regulations. Theoretically, this article enriches hybrid environmental governance discourse by emphasizing mediation as a relational mechanism enabling local institutions to bridge formal-informal domains. Empirically, the research contributes to understanding Southeast Asian lake governance by revealing district-level actors’ capacity to sustain environmental collaboration amid fragmented authority. Practically, findings offer policy recommendations for designing place-based sustainability strategies in natural resource-dependent regions. The article proceeds as follows: section 2 discusses methodology, section 3 presents findings across three themes, section 4 examines theoretical and policy implications, and section 5 reflects on future directions for research and environmental governance reform.

2 Methods

2.1 Research location profile

This study was conducted in the vicinity of Lake Matano, located in East Luwu Regency, South Sulawesi (Figure 1). The lake is part of an interconnected system of three major lakes—Matano, Mahalona, and Towuti—collectively known as the Malili Lake Complex. In 2014, the Indonesian government designated approximately 23,219 hectares of this area as a Nature Tourism Park through Ministerial Decree of Forestry No. SK.6590/Menhut-VII/KUH/2014, currently managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Agency (Balai Besar KSDA) of South Sulawesi.

The research site is situated in Nuha District and encompasses five villages: Sorowako, Nuha, Matano, Nikkel, and Magani. A notable feature of this location is the presence of PT Vale Indonesia’s nickel mining operation, which has been active for over 50 years, yet the lake ecosystem has remained remarkably well-preserved. This unique coexistence of industrial mining activity and environmental conservation prompted our investigation into how local authorities manage the delicate balance between economic development and ecological preservation.

Within this region, the indigenous Padoe, Dongi, and Matano communities, who have inhabited the area for generations, coexist with migrant populations, government institutions, and the mining corporation. This socially diverse landscape provides an opportunity to examine how local government mediates competing interests—ranging from environmental conservation and economic growth to the welfare of local communities.

2.2 Research design

In this study, we adopted an interpretive qualitative approach through an in-depth case study (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2017). We deliberately selected this method because our focus was not to generate broadly generalizable conclusions, but rather to understand in granular detail how social and institutional relationships operate within a highly specific setting—Lake Matano. We conceptualize the lake as a stage where three primary actors converge: government, corporations, and local communities.

A central focus of this research concerns how we position local government. Rather than merely functioning as policy implementers, local government actors operate as intermediaries working across multiple scales—from central to village levels—while simultaneously bridging the interests of the state, business entities, and citizens. To understand this dynamic, we draw upon hybrid environmental governance theory from Lemos and Agrawal (2006) and the concept of institutional mediation from Crona and Parker (2012). These theoretical frameworks illuminate the critical role local institutions play in connecting formal government regulations with the values and customary practices embedded within local communities.

We conceptualize local government as “social weavers” who skillfully navigate and integrate diverse interests and relationships between people and their environment. They operate through flexible mechanisms—at times negotiating, at times mediating—continuously adapting to evolving circumstances and shifting power dynamics.

2.3 Data collection

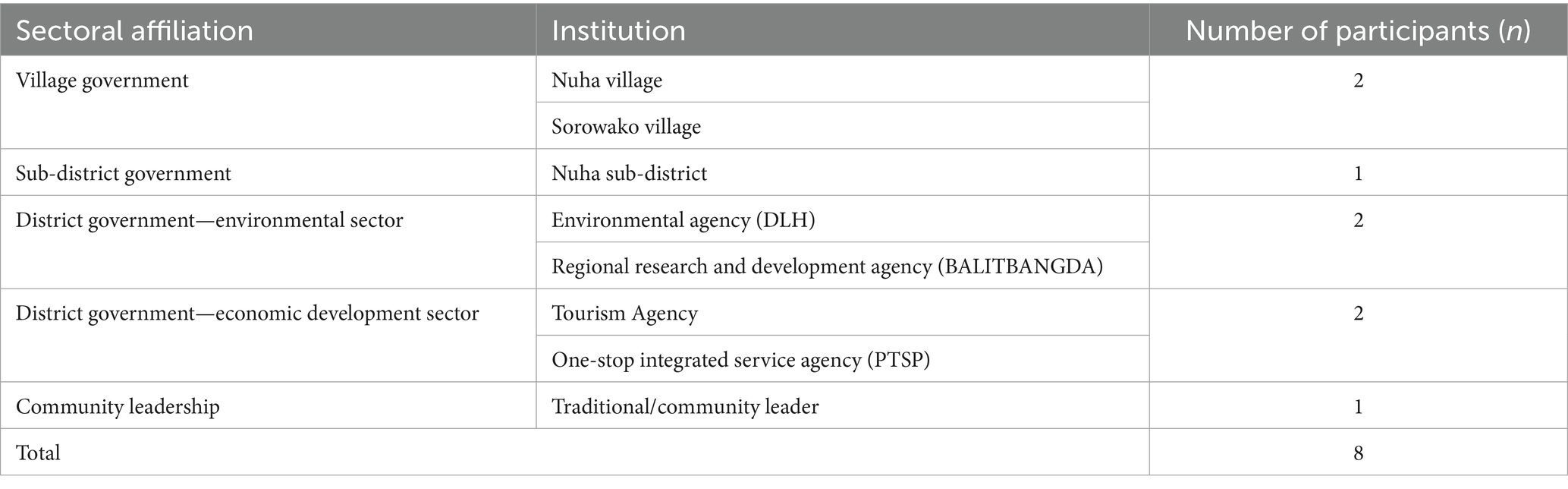

We collected research data throughout July 2025 using three complementary methods. First, we conducted in-depth interviews with eight key informants representing multiple governance levels—district, subdistrict, and village authorities, as well as community leaders. These informants held positions across various sectors, including environmental management, permitting, and spatial planning. To protect participant confidentiality, we have omitted their names and specific titles, referring to them instead by generic designations such as “district-level environmental official” or “village leader.” The semi-structured interviews lasted between 45 and 90 min and took place in various settings, including government offices, official residences, and neutral locations in and around Sorowako and Nuha. Using a flexible interview guide, we focused on eliciting participants’ experiences and perspectives regarding the tensions between environmental conservation and economic development imperatives. All interviews were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia, the shared language of researchers and participants.

We employed purposive sampling to identify and recruit key informants who possessed direct knowledge and experience in environmental governance at Lake Matano. The selection criteria focused on individuals occupying strategic positions across multiple governance levels (district, sub-district, and village) and sectors (environmental management, spatial planning, economic development, and community leadership).

We initially identified twelve potential participants through three channels: (1) official government organizational structures and preliminary site visits to relevant agencies in East Luwu Regency, (2) recommendations from the Natural Resources Conservation Agency (BKSDA) staff who facilitated initial access to the research site, and (3) snowball referrals from early participants who identified additional key actors involved in lake management decisions. Of the twelve individuals contacted through formal invitation letters and follow-up phone calls, ten agreed to participate. However, two district-level officials were unable to participate due to scheduling conflicts during the July 2025 research period.

Ultimately, eight in-depth interviews were successfully conducted with participants representing all critical governance tiers and sectoral perspectives relevant to Lake Matano management (see Table 1). Data collection continued until we reached theoretical saturation, evidenced by the convergence of perspectives on governance challenges, mediation practices, and stakeholder relationships. The final sample composition provided sufficient depth and diversity to address our research objectives while maintaining the confidentiality protections required by our ethical clearance.

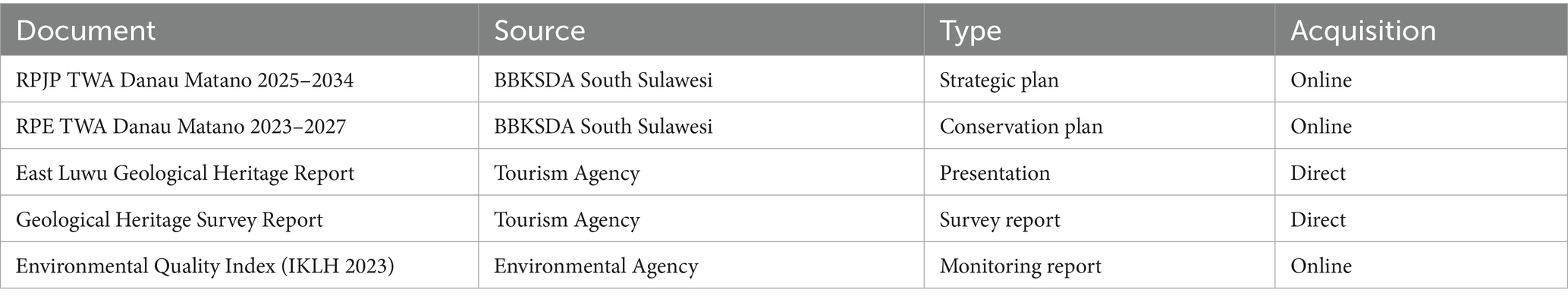

Second, we conducted a systematic document analysis of policy and planning materials relevant to Lake Matano governance. Documents were collected through two methods: (1) retrieval from official websites of relevant government agencies, and (2) direct acquisition from officials during fieldwork visits to institutional offices. We collected a total of five key documents from three source institutions: the Natural Resources Conservation Agency of South Sulawesi (BBKSDA Sulawesi Selatan), the Tourism Agency of East Luwu Regency (Dinas Pariwisata Kabupaten Luwu Timur), and the Environmental Agency of East Luwu Regency (Dinas Lingkungan Hidup Kabupaten Luwu Timur). These documents were selected based on their direct relevance to environmental management frameworks, conservation planning, and ecological monitoring of the Lake Matano region. Table 2 presents the complete list of documents included in the analysis. Third, we engaged in participant observation by immersing ourselves in various community activities, including participating in a community service event to clean the lakeshore, attending a Geopark awareness campaign in Nuha, and observing daily tourism operations at Molino Beach. Through these observations, we documented how different stakeholders interact and negotiate competing interests in practice.

This research received ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee of Hasanuddin University (Approval Number 632/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2025), ensuring compliance with ethical research standards, including obtaining informed consent from participants, maintaining anonymity, and safeguarding personal data.

2.4 Data analysis

In this study, we employed the reflexive thematic analysis approach to process our data (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Given our predefined research objectives and theoretical framework, we adopted a hybrid analytical strategy that combined deductive and inductive elements. The deductive component involved using our three research objectives—authority fragmentation, local initiatives, and mediation roles—as sensitizing concepts to guide initial data organization. The inductive component allowed specific themes and patterns to emerge organically from participants’ narratives within each broad category.

Interview data constituted the primary dataset and received full thematic analysis, while document and observation data served complementary functions. Policy documents were analyzed using directed content analysis to extract formal regulatory frameworks and institutional contexts. Field observation notes provided triangulation evidence—documenting actual practices that confirmed or complicated interview accounts. Following data triangulation principles (Patton, 2015), integration occurred at the interpretation stage rather than by merging all sources into a single coded dataset.

The analytical process was iterative and dynamic, commencing during fieldwork and continuing throughout the research. We began by immersing ourselves in the data through verbatim transcription of all interview recordings in Bahasa Indonesia, followed by multiple close readings to capture the underlying patterns and emotional dimensions of participants’ narratives.

In the first coding cycle, we employed structural coding aligned with our three research objectives. This involved assigning broad codes to data segments that addressed: (a) issues of authority, jurisdiction, and inter-agency coordination; (b) community-based practices and local environmental management; and (c) instances of negotiation, bridging, and mediation by local government actors. This deductive framework ensured systematic attention to our central research questions.

In the second coding cycle, we conducted inductive coding within each structural category to identify emergent sub-themes. For instance, within the “authority fragmentation” category, we identified specific manifestations such as jurisdictional overlap, enforcement gaps, and planning disconnects. Within the “mediation” category, we identified mechanisms such as trust-building, informal dialogue, and kinship-based approaches. This two-stage process enabled us to maintain analytical focus while remaining open to unexpected findings.

Subsequently, we clustered related codes into coherent thematic categories and theoretically situated these within our frameworks of hybrid governance (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006) and institutional mediation (Crona and Parker, 2012). To ensure consistency and validity, we triangulated interview findings with the Regional Long-Term Development Plan for the Lake Matano Nature Tourism Park and field observations.

Throughout the research process, we maintained reflexive memos documenting our potential biases and assumptions as researchers, consistent with the principles of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Rigor was strengthened through member checking with selected participants, peer debriefing sessions, and comprehensive documentation of the entire analytical trajectory. Data analysis was conducted in Bahasa Indonesia to preserve original meanings and contextual nuances. Translation into English occurred only at the manuscript preparation stage, with selected quotations translated by the bilingual first author and verified through back-translation of key passages to ensure conceptual equivalence (van Nes et al., 2010).

3 Results

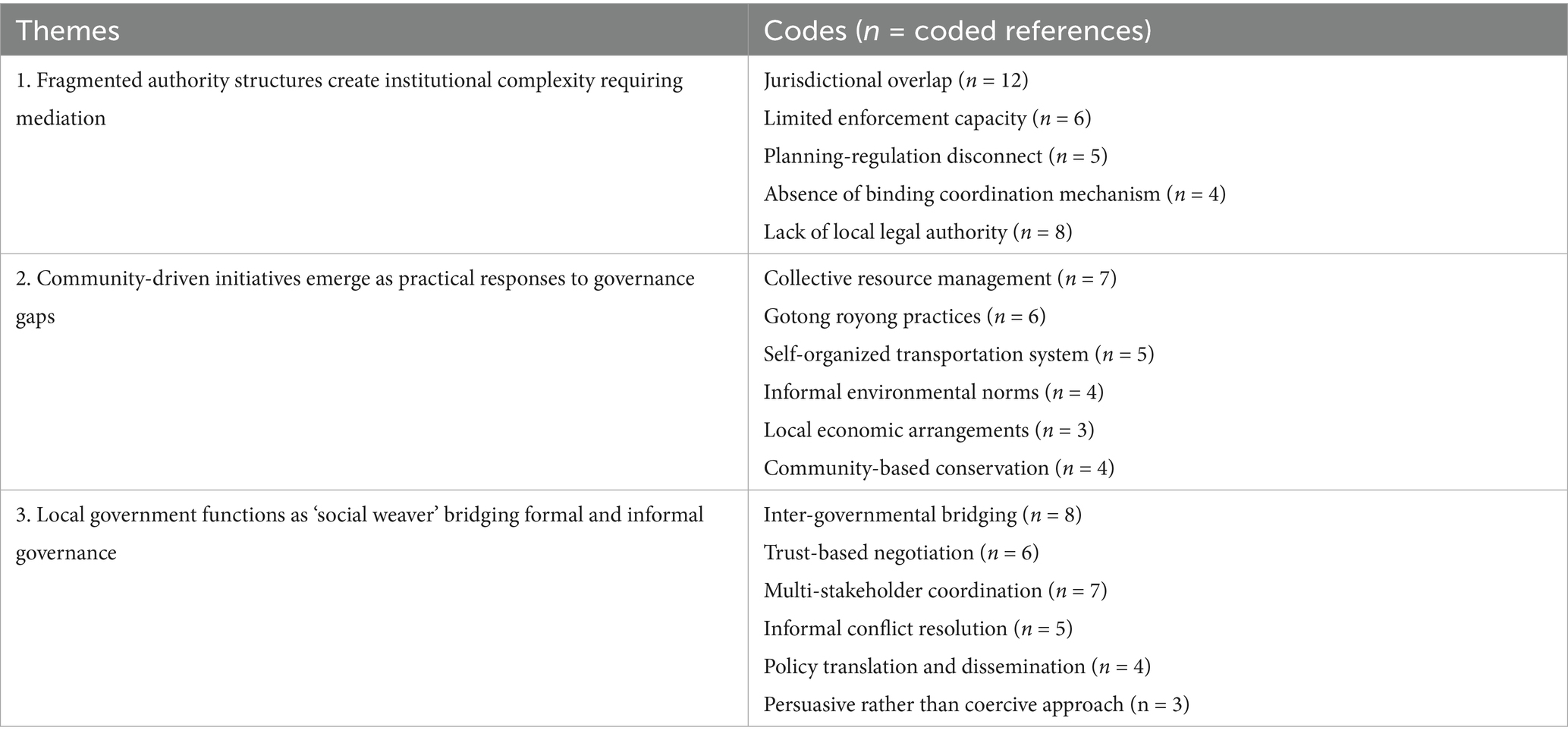

The thematic analysis yielded three interrelated findings that collectively address our research objectives, as summarized in Table 3. This table presents the emergent themes and their constituent codes, with the frequency of coded references (n) indicating the empirical grounding of each pattern across eight interview transcripts. First, we identified overlapping and fragmented authority structures (Theme 1, comprising five codes with 35 total references) that characterize Lake Matano governance, creating institutional complexity that necessitates mediation. Second, we documented community-driven initiatives (Theme 2, comprising six codes with 29 total references) that have emerged as practical responses to governance gaps and have become embedded in everyday environmental management practices. Third, we examined the local government’s role as a ‘social weaver’ (Theme 3, comprising six codes with 33 total references) that stitches together environmental and social sustainability amid the competing interests of the central government, corporations, and local communities. These three findings constitute the empirical foundation for understanding how local governments function as institutional mediators in mining-lake regions. The following sections present each finding in detail, drawing upon the specific codes identified in Table 3.

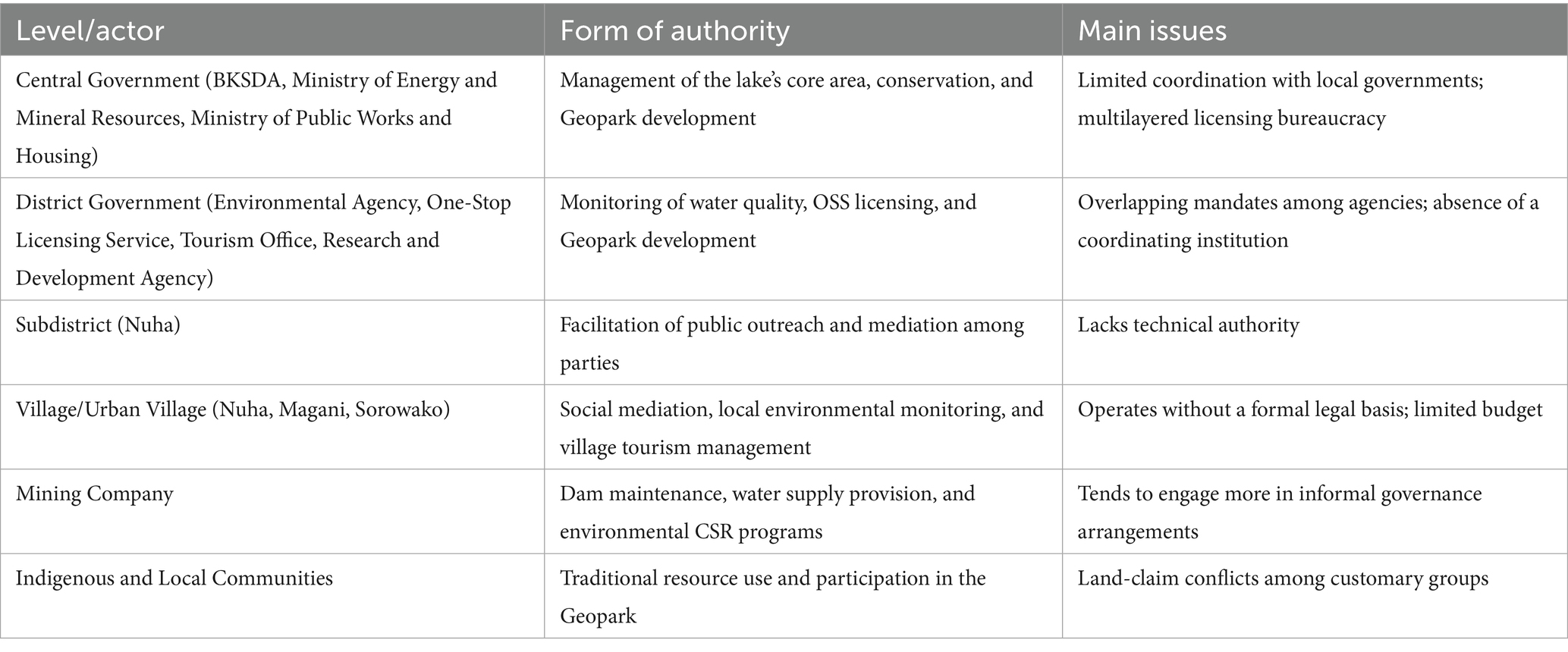

3.1 Fragmentation of authority in Lake Matano management

Through a series of conversations with various informants across multiple levels of government, we identified a particularly concerning primary issue: the management of Lake Matano involves an overwhelming number of overlapping agencies. Our informants, ranging from central government officials to provincial and district-level administrators, unanimously agreed that inter-agency coordination remains severely deficient. The complexity deepens further as administrative boundaries fail to align with the lake ecosystem’s natural boundaries, rendering existing policies difficult to implement comprehensively.

A district-level licensing official explained to us that they face significant constraints in issuing business permits around the lake. The area extending 50 meters from the lake’s edge falls entirely under the jurisdiction of the Natural Resources Conservation Agency (BKSDA) and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing. Nevertheless, during our fieldwork around the lake, numerous unauthorized structures remained visible. This situation represents a troubling irony that underscores weak field-level enforcement (Participant 6, Interview and Observation, July 2025).

This perspective was reinforced by a regional planning official who offered an intriguing insight: although Lake Matano lies geographically within their administrative territory, its legal status as a national conservation area relegates the local government to the sidelines. Their involvement is confined to developing tourism support facilities and community empowerment programs, with no authority over the lake’s core management (Participant 2, Interview, July 2025).

At the sub-district level, a mid-level government official candidly acknowledged that their role functions merely as a “communication bridge” between the community and higher levels of government. They lack the technical authority to directly address the lake’s environmental issues (Participant 4, Interview, July 2025).

Most significantly, village heads and neighborhood chiefs—positioned at the grassroots level—confront the lake’s various problems most directly. Several village leaders we interviewed described how residents consistently approach them with issues ranging from land disputes and pollution to illegal shoreline development. These officials must manage waste, mediate conflicts, and regulate residents’ economic activities along the lake’s edge, despite lacking formal authority to do so (Participant 8, Interview, July 2025).

The impact of this bureaucratic complexity is palpable. Without a clear institutional “commander,” each agency operates independently according to its sectoral interests. Bottom-up innovations that would better serve community needs are frequently obstructed by top-down regulations. A regional tourism department official illustrated this with a concrete example: the difficulty of preparing the Lake Matano Geopark documentation. Several proposed sites fell within company mining areas, while others overlapped with strict conservation zones. Consequently, the process stalled for months (Participant 3, Interview, July 2025).

This complexity intensifies as each stakeholder maintains different priorities. The central government emphasizes conservation and biodiversity protection. Regional governments seek to develop tourism to boost local economies. Meanwhile, communities living around the lake prioritize their daily needs: clean water, transportation, and livelihoods. These divergent visions render inter-stakeholder cooperation extremely challenging, often resulting in mere patchwork solutions.

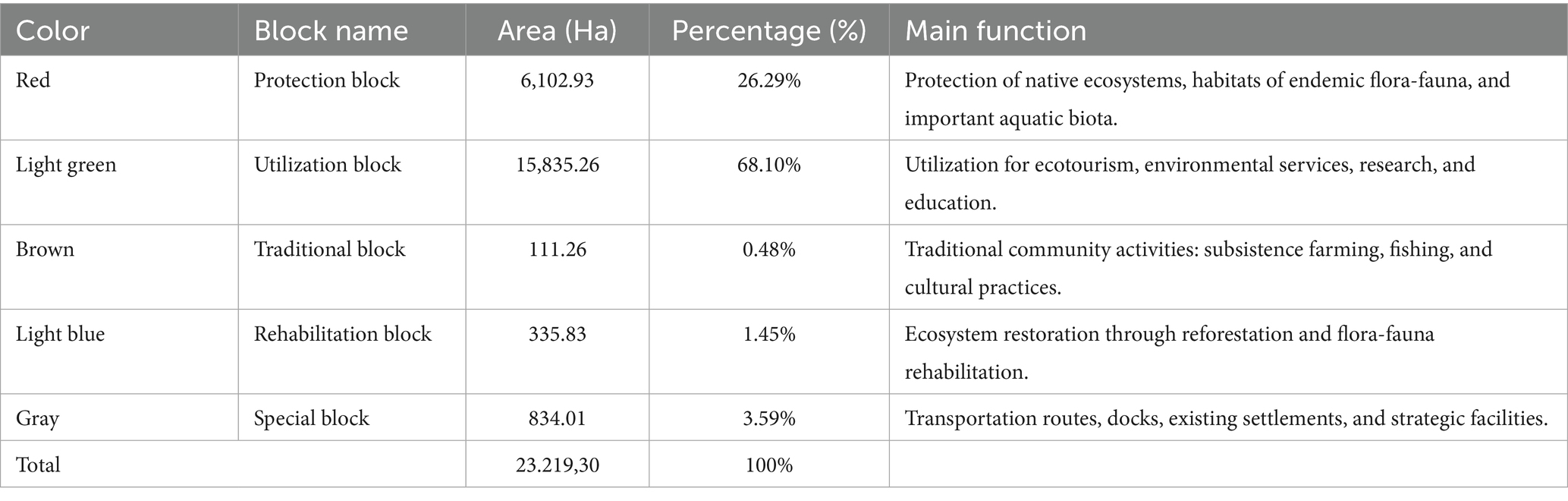

An examination of the Long-Term Management Plan (RPJP) document for the Lake Matano Nature Recreation Park 2025–2034 revealed that the lake area has indeed been divided into five zones with distinct functions, ranging from protection to utilization zones (see Figure 2 and Table 1). However, in practice, this zoning scheme fails to synchronize with district spatial planning. Several areas designated for tourism conflict with mining territories or customary lands. This demonstrates the fragility of planning coordination among conservation, mining, and regional economic development sectors.

The map and data presented in Figure 2 and Table 4 show that the Lake Matano Nature Recreation Park encompasses five management zones totaling 23,219 hectares. Particularly notable is the dominance of the utilization zone, which comprises nearly 70% of the area—marked in light green on the map. This zone accommodates various activities from ecotourism to research. Meanwhile, the protection zone, which functions to preserve the original ecosystem, covers only approximately one-quarter of the total area, located in the central to western sections. Several smaller zones also exist: a rehabilitation area for ecosystem recovery (1.45%), a traditional zone for local community needs (0.48%), and a special zone for infrastructure such as piers and settlements (3.59%). This division reflects the classic dilemma of balancing economic interests with conservation efforts.

Coordination problems exist not only between central and regional governments but also among district-level agencies. The Environmental Agency focuses on monitoring water quality, while the Tourism Agency concentrates on developing the Geopark program. Ironically, despite their mutual dependence—tourism requires a clean environment—coordination between them remains minimal. A district-level environmental official revealed their limitations: “We can only conduct monitoring twice a year, and we lack the authority to enforce violations because this lake remains under central jurisdiction” (Participant 7, Interview, July 2025).

The Tourism Agency faces similar constraints; they cannot finalize the Geopark proposal without approval from the ministry and BKSDA. More troubling still, no single institution truly serves as the “helmsman” for cross-sectoral coordination. Even the regional research institution that initially prepared crucial documentation on the area’s geological heritage was forced to transfer responsibility to the Tourism Agency due to organizational restructuring. As a result, many programs were interrupted mid-course and lost momentum.

In the field, the impact of this bureaucratic chaos is acutely felt. Village governments frequently become residents’ first point of complaint, despite lacking formal authority. One coastal village, for instance, must handle land disputes in coastal areas and regulate illegal buildings, even though these areas actually fall within conservation zones managed by BKSDA. A local village leader explained: “Residents trust us more than central agencies. So we resolve issues through kinship approaches, through deliberation, not formal procedures” (Participant 1, Interview, July 2025).

The role of the local mining company is equally distinctive. They manage three critical dams that maintain the lake’s water balance, yet their coordination with the local government remains largely informal. This situation illustrates a stark reality: Lake Matano’s management is trapped in jurisdictional fragmentation. Overlapping authorities, weak coordination, and the absence of clear institutional leadership have created a governance vacuum. This gap is then filled by various informal local-level initiatives, a phenomenon that will be explored in greater depth in the following section (summarized in Table 5).

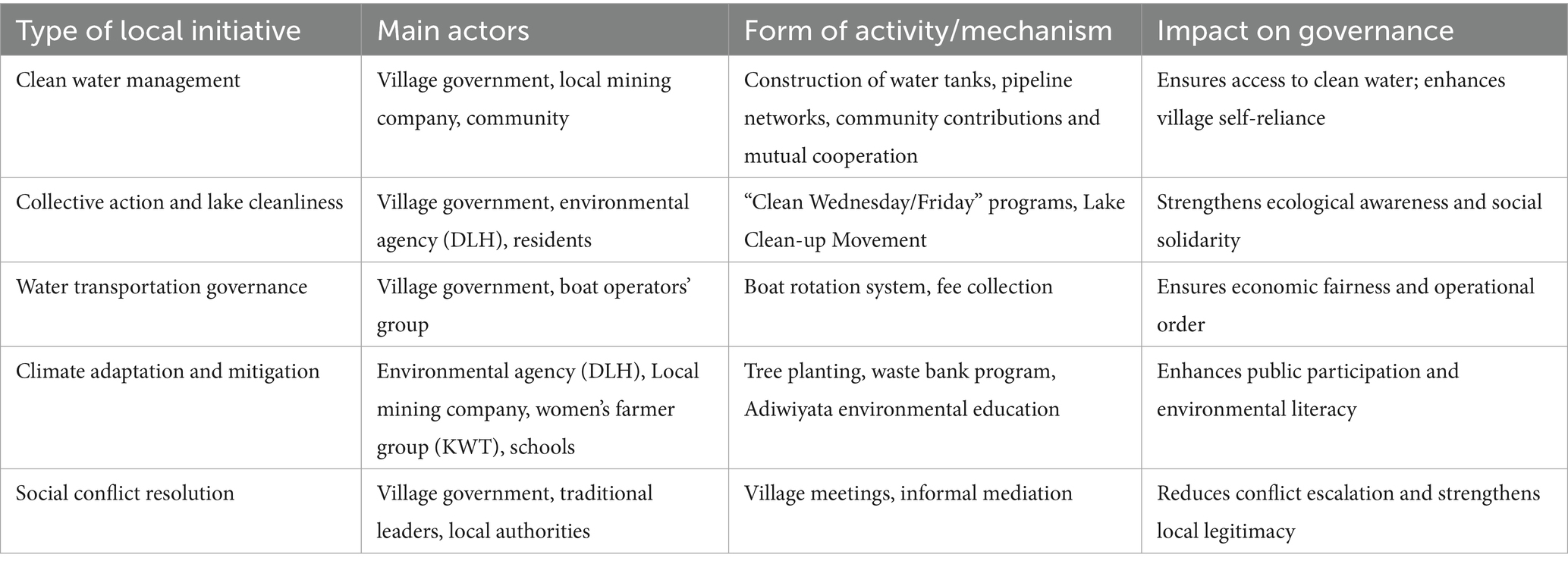

3.2 Local initiatives as de facto governance

When formal bureaucracy becomes entangled in coordination complexities, local communities do not remain passive. They develop their own mechanisms for managing Lake Matano, ranging from organizing clean water access and maintaining lake cleanliness to coordinating water transportation and implementing environmental conservation efforts. These initiatives emerge organically from the community’s daily needs, filling the void left by formal institutions.

In Nuha Village, the clean water supply system operates through a simple yet effective framework. A local village leader explained that residents continue to rely on lake water for daily needs, utilizing both private pumps and collectively managed distribution networks. “We received two water tanks from the mining company, and they also helped construct water pipes in several settlements,” he noted. Notably, facility maintenance is conducted through gotong royong (communal work) with voluntary contributions from residents (Participant 5, Interview, July 2025).

Lake water serves purposes beyond drinking and bathing; it constitutes a source of economic livelihood. Many residents utilize it for small-scale enterprises such as crafting woven products from local aquatic plants or household-scale fish cultivation. For coastal communities, the lake represents an integral component of their identity. This consciousness motivates them to maintain water quality without formal regulatory enforcement.

The spirit of gotong royong remains vibrant in the lake’s coastal areas. In several villages, Wednesdays and Fridays are designated for collective cleaning activities. All community segments—from village officials and women to youth—participate in cleaning the lakeside. “Nobody is coerced; everyone acts because they recognize that this lake sustains our livelihood,” stated a community leader (Participant 8, Interview, July 2025). These activities frequently receive equipment support from the mining company and local environmental agencies, creating grassroots collaboration rather than top-down directives.

In Nuha Village, where approximately 70 percent of residents work as water transportation providers, the village government has established a “boat lot” system—a rotation schedule ensuring equitable opportunities for all boat operators. “About 70 percent of our residents depend on this enterprise. Without regulation, passenger competition would emerge,” explained a village official. They even issue fuel purchase recommendation letters for gas stations, collaborating with the transportation department. Interestingly, proceeds from transportation operations partially fund public facility improvements and places of worship (Participant 5, Interview, July 2025).

Additionally, since 2023, climate adaptation programs have been implemented across five villages surrounding the lake. Each village employs distinct approaches: some focus on planting trees to protect water sources, others develop environmentally friendly products, while some establish women’s farmer groups for food security. A district-level environmental official acknowledged: “Our budgetary and personnel constraints have been mitigated through active community participation. Even schoolchildren are involved as environmental ambassadors for their families” (Participant 7, Interview, July 2025).

The relationship between communities and the mining company proves more complex than mere economic transactions. In one village, residents declined protest invitations, feeling they had received substantial assistance—from sports fields and water networks to scholarships. An unwritten agreement exists: the company provides social facilities while the community maintains order and environmental conservation.

Village governments also function as local “peace mediators.” A village leader explained: “For every issue—whether interpersonal conflicts or environmental concerns—we first attempt resolution at the village hall through deliberation. Only when this fails do we escalate to the sub-district or police” (Participant 5, Interview, July 2025). This approach underscores that trust and social bonds remain foundational to collective life governance.

Across these local initiatives, local communities clearly do not passively await directives from above. They create governance systems that may not appear in official documents but tangibly impact daily life. Village governments, community groups, and local companies each play complementary roles. This represents hybrid governance rooted in noble values: gotong royong, mutual trust, and shared responsibility for preserving their natural heritage (see Table 6).

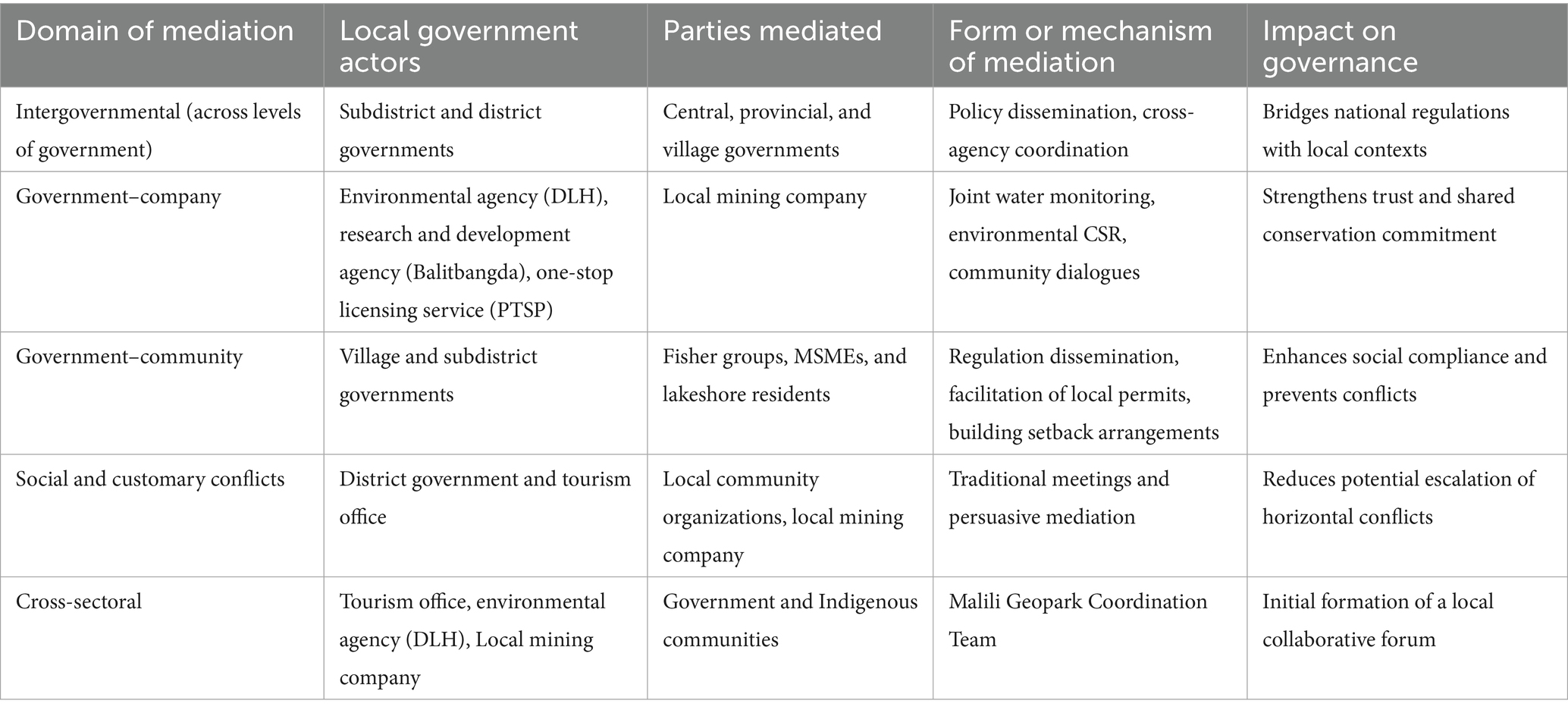

3.3 Local governments as multi-level mediators

The role of local government in managing Lake Matano extends far beyond simply implementing top-down policies. These authorities function as crucial intermediaries connecting diverse stakeholders—including the central government, mining corporations, and local communities residing around the lake. Within the complex framework of authority distribution, regional governments serve as “social bridges,” ensuring effective communication and coordination among all parties. This role manifests through various mechanisms, ranging from inter-agency coordination and dialogue facilitation to conflict resolution in the field.

A critical function of local government involves ensuring that central policies reach communities through appropriate channels. A subdistrict-level official explained that they frequently serve as liaisons when programs originate from ministries or provincial authorities. For instance, when conducting outreach regarding lake border demarcations or conservation initiatives, subdistrict offices organize meetings with affected villages. “We strive to ensure communities understand existing regulations while simultaneously verifying that these policies align with ground realities,” the official noted (Participant 4, Interview, July 2025).

At higher administrative levels, inter-departmental coordination proves essential. Various agencies—including environmental services, tourism departments, and regional research bodies—convene regularly to establish shared perspectives on lake management. This coordination becomes particularly vital when developing strategic documents such as the Malili Lake Complex Geopark development plan. However, a regional research official acknowledged that coordination efforts remain fragmented without formal binding mechanisms. “We initiate programs, but implementation depends heavily on cooperation with other departments” (Participant 2, Interview, July 2025).

Local government also functions as a “policy filter” for central directives. In licensing matters, for example, relevant departments reject business permits in conservation zones while simultaneously assisting communities in identifying alternative locations that comply with regulations. This approach demonstrates how regional authorities balance regulatory enforcement with community needs.

The relationship with local mining companies exemplifies how regional governments cultivate mutually beneficial partnerships. Both parties share interests in preserving the lake: the government prioritizes conservation and community welfare, while mining operations depend on lake water for their activities. “If the lake deteriorates, company operations suffer. That’s why they deeply care about lake preservation,” explained a regional research official (Participant 2, Interview, July 2025).

This collaboration materializes through various forms, including infrastructure support, clean water provision, and participation in environmental activities. The local mining company serves as the government’s primary partner in monitoring water quality and rehabilitating coastal areas. Although no formal agreement exists, this relationship operates on mutual dependency—the government gains technical support and resources, while the company secures social legitimacy from authorities and communities.

When community concerns about mining impacts arise, subdistrict governments assume mediating roles. They organize meetings among residents, companies, and environmental departments to address these concerns. “Local communities trust direct dialogue more than written reports. Therefore, we facilitate face-to-face meetings to build trust,” a subdistrict official clarified (Participant 4, Interview, July 2025).

Local authorities also play crucial roles in translating conservation policies into comprehensible and acceptable terms for communities. When central agencies conduct outreach about lake border demarcations, subdistrict and village governments help re-explain these concepts using simpler language. This becomes essential as many long-term residents in areas now designated as conservation zones experience confusion regarding changes to their land status.

The adopted approach follows a principle of “regulating rather than prohibiting entirely.” A village head explained that they continue permitting economic activities within certain distances of the lake border, provided these do not harm the ecosystem (Participant 1, Interview, July 2025). Villages also facilitate permits for local tourism activities and small businesses, ensuring these operations remain environmentally sustainable. This approach maintains equilibrium between community economic needs and conservation objectives.

One of the most significant challenges involves managing indigenous land claims around the lake. Two indigenous groups assert claims to the same territory, creating potential conflict. Although regional governments lack legal authority to adjudicate indigenous claims, they facilitate dialogue to prevent conflict escalation. Open meetings are organized involving indigenous leaders, company representatives, and religious figures to find common ground.

In addressing illegal construction along lake borders, local government favors persuasive approaches. “Immediate demolition would trigger major protests. We prefer gradual approaches, encouraging them to adapt progressively to regulations,” stated a regional tourism official (Participant 3, Interview, July 2025). This strategy reflects local government sensitivity to social dynamics, seeking to enforce regulations without generating unnecessary tensions.

Despite functional mediation processes, cross-sectoral coordination still faces institutional constraints. No permanent forum binds all parties, resulting in sporadic coordination dependent on specific catalysts. However, positive developments have emerged with the establishment of the Malili Geopark Coordination Team, incorporating various departments, local mining companies, and indigenous community representatives. This team potentially represents the foundation for more structured future governance mechanisms.

In conclusion, local governments have fulfilled vital roles as mediators, maintaining balance among diverse interests at Lake Matano (see Table 7). Despite limited authority and resources, their capacity to facilitate dialogue, coordinate across sectors, and conduct social negotiations has provided essential foundations for sustainable lake management. Their success in executing these roles critically determines whether economic development and environmental preservation can proceed harmoniously without sacrificing local community welfare.

4 Discussion

Our research reveals that environmental governance at Lake Matano faces significant challenges stemming from institutional fragmentation, whereby numerous agencies operate independently without effective coordination. Remarkably, however, local communities have not remained passive—they have instead developed innovative strategies to sustain lake conservation despite suboptimal formal systems. Three key findings emerged from our analysis: first, the dispersion of authority across multiple institutions; second, autonomous initiatives undertaken by local populations; and third, the mediating role performed by local governments in reconciling competing stakeholder interests. These findings demonstrate that lake sustainability cannot rely solely on formal regulations but requires communities to possess the capacity to build communicative bridges across diverse institutions and interests (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006; Crona and Parker, 2012). In essence, social capital serves as the binding force that coheres a fragmented system.

The overlapping jurisdictions at Lake Matano represent a familiar phenomenon in developing nations, where governmental bodies, private enterprises, and civil society compete for environmental governance authority (Baker et al., 2020; Ghosh and Wolf, 2021). Consider the inherent contradiction: a lake that recognizes no administrative boundaries must be managed simultaneously by multiple districts, inevitably generating conflicts among centralized conservation policies, regional mining permits, and various local programs. Parallel research in China and the Philippines has documented similar challenges: when subnational governments receive authority without adequate coordination mechanisms with central authorities, governance voids emerge in which no entity assumes genuine responsibility (Li et al., 2016; Reyes, 2020). In Indonesia, regional autonomy has granted districts greater authority, yet this decentralization has not been accompanied by sufficient coordination mechanisms (Vujanovic, 2017). Our findings align with Anand et al. (2024), who demonstrate that lakes in peri-urban Asian regions are frequently managed through weakly coordinated networks, rendering their sustainability heavily dependent on local governments’ adaptive capacity. Without this adaptive capability, interest conflicts persist and threaten ecosystem integrity.

Encouragingly, communities have not acquiesced to these circumstances but have instead generated autonomous solutions through diverse initiatives, including collective water management, communal lake cleanup efforts, and self-organized water transportation systems (Gain et al., 2021). This constitutes tangible evidence that communities and village governments can establish governance systems rooted in collective action rather than merely awaiting top-down directives. These practices emerge from the daily needs of lakeside residents. This phenomenon can be characterized as “just hybrid governance”—a form of justice created by communities outside formal legal frameworks when such systems fail to address their needs (Toxopeus et al., 2020). At Lake Matano, village and subdistrict governments function as critical bridges between formal institutions and communities, underscoring the importance of social mediation in filling institutional voids (Crona and Hubacek, 2010).

Notably, local mining companies have participated in sanitation and water conservation programs, demonstrating that cross-sectoral collaboration can succeed when built upon mutual dependence rather than coercion. Companies require clean water for operations, while communities need support for environmental stewardship. Collaborations involving corporations and local governments prove more effective when constructed on social legitimacy—namely, community trust—rather than merely contractual obligations (Pirard et al., 2023). Similar findings emerge from Wahyono et al. (2025) at Lake Dieng, where partnerships among companies, communities, and local governments generated innovative responses to environmental risks.

Local governments occupy a distinctive role as “brokers” connecting multiple governance levels and interests (Aggarwal and Anderies, 2023). They not only implement policies from above but also translate and adapt regulations to accommodate local conditions—functioning analogously to interpreters who convey meaning rather than merely translating words literally. This mediating function signals a transition from rigid, hierarchical governance models toward more flexible, relational approaches, wherein governments earn legitimacy through their capacity to reconcile diverse interests. This bridging capacity proves essential for enabling successful cooperation in complex social-ecological systems (Boakye-Danquah et al., 2018).

At Matano, mediation processes frequently occur informally through dialogue, deliberation, and even personal conversations among key figures, rather than through official correspondence or formal meetings. These traditional approaches prove effective for conflict resolution, particularly regarding land and boundary disputes. This practice aligns with “adaptive co-management” concepts (Armitage et al., 2010), which emphasizes that ecosystem sustainability depends on local communities’ capacity for continuous learning and adaptation. In this context, local governments function as ‘social weavers’ who stitch together diverse domains (state, market, and civil society) through ongoing, multilayered mediation. They serve as connectors, ensuring all parties can convene and seek collaborative solutions.

Compared with research at Lake Toba (Naibaho and Su, 2025), our study offers novel insights by conceptualizing mediation as relationship-building rather than merely technical coordination among institutions. Mediation concerns trust-building and communication, not simply task allocation. Hybrid organizations achieve effectiveness by reconstructing social relationships through trust and communication that cross institutional boundaries (Deng et al., 2021). Lake Matano exemplifies governance that may appear structurally fragile yet remains socially robust due to interpersonal bonds and trust among residents.

Theoretically, this research enriches the concept of “hybrid environmental governance” (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006) by incorporating relational mediation as an institutional adhesive. Previous co-management research has primarily focused on role distribution while insufficiently examining how inter-institutional relationships are maintained through everyday negotiation and compromise (Domptail et al., 2013). At Matano, lake sustainability persists not because regulations are clear but because individuals can translate formal rules into values acceptable to communities. This mediating capacity enables system functionality despite inherent contradictions.

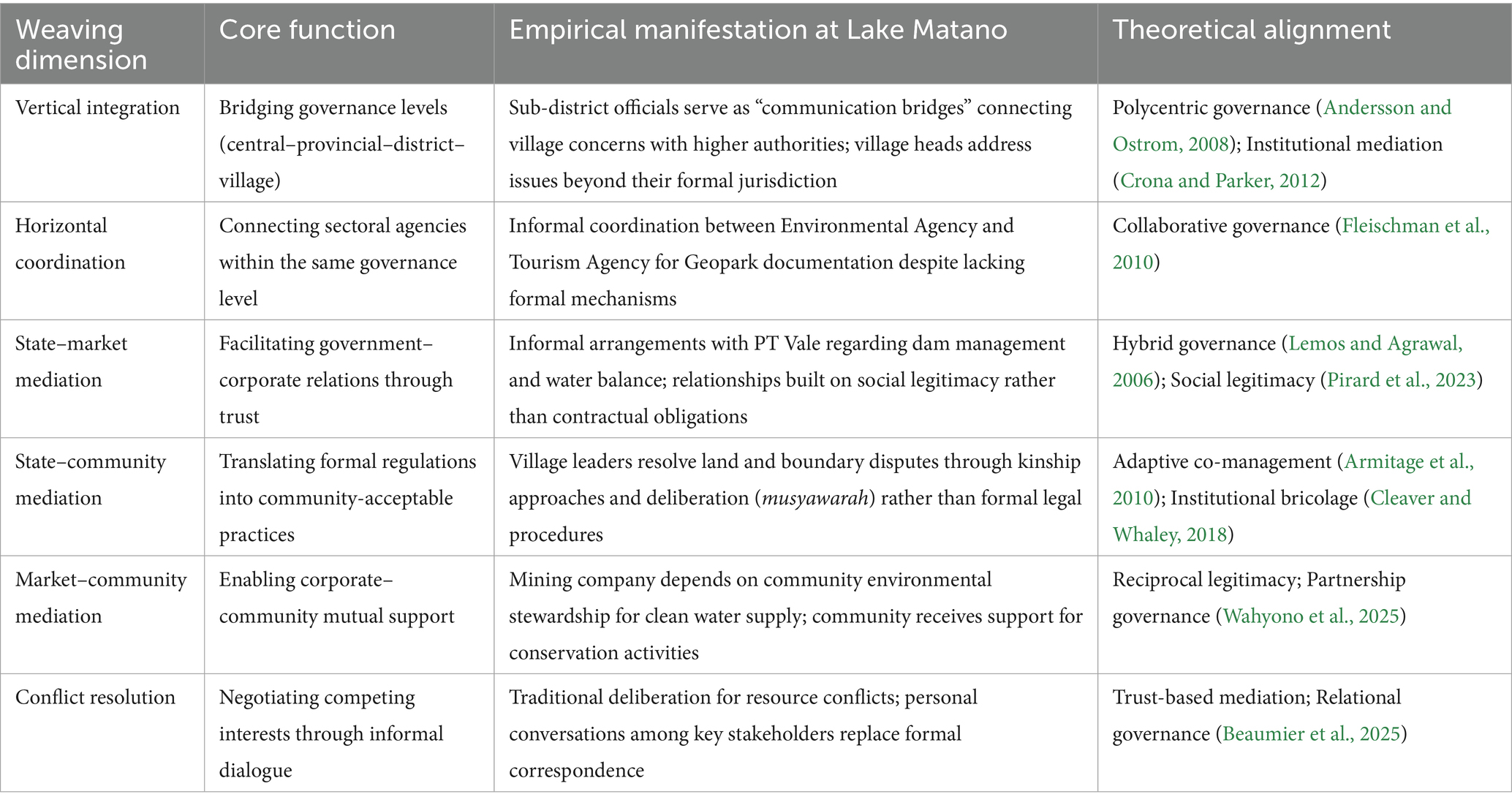

To systematically conceptualize local government’s mediating role as discussed above, we propose the ‘social weaver’ framework that synthesizes our empirical findings with existing governance theories. Table 8 presents six weaving dimensions that capture how local governments at Lake Matano integrate fragmented governance arrangements into a cohesive fabric of environmental management. The framework identifies three core functions that local governments perform: translating formal regulations into locally meaningful practices, bridging multiple governance levels and sectors, and negotiating competing interests through trust-based dialogue.

Table 8. The “Social Weaver” framework: local government’s mediating functions in Lake Matano governance.

This framework offers a transferable analytical lens for examining local government mediation in other contested socio-ecological systems. For practical implementation, three lessons emerge. First, local governments must be strengthened as mediators, not merely policy implementers (Minneti, 2018). Second, community initiatives require formalization to prevent their disappearance when key figures change (Boakye-Danquah et al., 2018). Third, collaborations with local mining companies can be enhanced through transparent, trust-based forums rather than relying solely on legal obligations (Pirard et al., 2023). Trust represents social capital that cannot be purchased.

For future policy, establishing a “Lake Matano Collaborative Body” could address jurisdictional overlaps and enhance cooperation (Gain et al., 2021). Such a forum could integrate nature tourism park management plans with district spatial planning, as recommended by Aggarwal and Anderies (2023). This would provide all stakeholders with space for voice and collective solution-seeking.

An unexpected finding emerged: communities exhibit greater trust in mining companies than in central government institutions—an irony given that mining is typically perceived as an environmental threat. This phenomenon reveals new forms of legitimacy built upon mutual interdependence, where environmental conservation becomes a shared interest bridging economic and ecological concerns. Similar patterns emerge in green city governance, where environmental justice is reinforced through common interests (Toxopeus et al., 2020). At Matano, relationships among local government, communities, and corporations are reciprocal—characterized by mutual exchange rather than hierarchical authority.

The community’s approach to conflict resolution through informal deliberation also merits attention. This aligns with Giddens (1984) structuration theory, whereby local communities create new social rules within existing formal structures. They do not resist the system but discover creative spaces within it. Governance at Matano exemplifies how local communities integrate social adaptability with ecological resilience (Aggarwal and Anderies, 2023). This demonstrates that communities are not passive objects but active agents determining their environmental fate.

While this study offers meaningful insights into the mediating role of local governments in environmental governance, several methodological limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, as a single-case study focused exclusively on Lake Matano, the findings are inherently context-specific and may not directly apply to other mining-lake regions with different political configurations, corporate actors, or community structures. The unique characteristics of Lake Matano—including its designation as a Nature Tourism Park, the long-established presence of PT Vale, and the particular composition of indigenous and migrant communities—may have shaped governance dynamics in ways that differ from other localities. Second, our reliance on eight key informants, though strategically selected to represent multiple governance levels and sectors, constrains the breadth of perspectives captured. Certain stakeholder voices—particularly those of marginalized community members, environmental activists, or mining company employees—remain underrepresented in this analysis. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of data collection during a single month (July 2025) limits our ability to capture temporal dynamics, seasonal variations in governance practices, or the evolution of stakeholder relationships over time. These limitations suggest that our findings should be interpreted as indicative patterns rather than definitive conclusions, and readers should exercise caution when extrapolating these insights to other contexts.

This research opens numerous avenues for further inquiry. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine how trust networks and collaborative arrangements endure through leadership transitions and policy shifts (Boakye-Danquah et al., 2018). Can systems built on personal relationships survive when key figures are no longer active? Additionally, comparative research with other mining-lake regions in Southeast Asia could strengthen the “social weavers” concept as an institutional mediation model in developing countries (Minneti, 2018; Beaumier et al., 2025). Through further investigation, we can better understand how local communities generate creative solutions to complex environmental challenges.

5 Conclusion

This study finds that the successful management of Lake Matano is contingent upon the capacity of the local government to adapt and serve as an intermediary among multiple stakeholders. Despite the presence of numerous institutions with overlapping regulations, local authorities have effectively navigated these complexities through three principal mechanisms: resolving regulatory ambiguities, supporting community-based initiatives, and facilitating communication across different governmental levels. Notably, the effectiveness of lake governance is not determined solely by formal regulations codified in official documents. Rather, it is the local government’s capacity to “weave together” relationships among government entities, mining corporations, and local communities that constitutes the critical factor. They function analogously to weavers who patiently integrate disparate threads of interests—balancing environmental protection imperatives, economic development objectives, and community welfare considerations. The study further demonstrates that flexible collaboration among government, corporations, and residents can compensate for the rigidity inherent in formal coordination systems.

This research offers several important implications. Theoretically, the study contributes to environmental governance literature by introducing the “social weaver” conceptualization, which extends hybrid governance theory (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006) by emphasizing relational mediation as an institutional adhesive that binds fragmented governance systems. This framework shifts analytical attention from formal institutional arrangements to the everyday practices of negotiation, trust-building, and dialogue through which local governments reconcile competing interests. The findings also enrich institutional mediation theory (Crona and Parker, 2012) by demonstrating that effective mediation in developing country contexts often operates through informal mechanisms rooted in cultural values such as gotong royong (mutual cooperation) and musyawarah (deliberation), rather than through formalized coordination structures.

Practically, this study carries significant implications for environmental policy design in decentralized governance systems. First, capacity-building programs should prioritize strengthening local governments’ mediating competencies—including negotiation skills, stakeholder facilitation, and conflict resolution—rather than focusing exclusively on technical environmental management capabilities. Second, national conservation policies should formally recognize and integrate community-based initiatives that have demonstrated effectiveness in filling governance gaps, thereby preventing their disappearance when key local figures transition out of their roles. Third, regulatory frameworks governing mining operations in ecologically sensitive areas should mandate the establishment of multi-stakeholder collaborative forums that institutionalize dialogue among government agencies, corporations, and local communities.

More broadly, this research suggests that the sustainability of lake ecosystems in mining regions across developing countries depends fundamentally on governance approaches that transcend technocratic-managerial paradigms. Environmental protection in contexts of institutional fragmentation and competing economic pressures requires what we term “relational governance”—systems built on trust, social capital, and ongoing negotiation rather than solely on regulatory compliance and enforcement. This has profound consequences for how international development agencies and national governments design environmental interventions: success hinges not merely on creating new institutions or regulations, but on nurturing the social relationships and mediating capacities that enable diverse actors to collaborate despite divergent interests. The Lake Matano case demonstrates that local governments, when empowered as mediators rather than mere policy implementers, can serve as critical agents in achieving the delicate balance between environmental preservation, economic development, and social justice in resource-rich territories.

Admittedly, this research has several limitations, as it focuses on a single case at Lake Matano and does not examine long-term developments. To establish the generalizability of these findings, comparable studies should be conducted in mining regions adjacent to lakes across other Southeast Asian nations. Future research should investigate how the local government’s mediating role endures or evolves amid leadership transitions, policy shifts, and intensifying environmental pressures. Additionally, subsequent studies would benefit from employing multiple methodological approaches and mapping inter-stakeholder networks to identify influential actors and understand how trust is constructed among them.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ES: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. IN: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the Institute for Research and Community Services (LPPM), Universitas Hasanuddin, through the Hasanuddin University Early Career Researcher Grant (PDPU) under contract number 01260/UN4.22/PT.01.03/2025.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges this financial support, which made this study possible.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, E. A., Juran, L., and Ajibade, I. (2018). ‘Spaces of exclusion’ in community water governance: a feminist political ecology of gender and participation in Malawi’s urban water user associations. Geoforum 95, 133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.016,

Aggarwal, R. M., and Anderies, J. M. (2023). Understanding how governance emerges in social-ecological systems: insights from archetype analysis. Ecol. Soc. 28:202. doi: 10.5751/ES-14061-280202

Anand, A., Zeng, Y., Reckien, D., and Pfeffer, K. (2024). Governance interactions concerning peri-urban lake ecosystems: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Commons 18, 670–688. doi: 10.5334/ijc.1409

Anderson, C., Joshi, A., Barnes, K., Ahmed, A., Ali, M., Chaimite, E., et al. (2023). Everyday governance in areas of contested power: insights from Mozambique, Myanmar, and Pakistan. Dev. Policy Rev. 41:e12683. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12683

Andersson, K. P., and Ostrom, E. (2008). Analyzing decentralized resource regimes from a polycentric perspective. Policy Sci. 41, 71–93. doi: 10.1007/s11077-007-9055-6

Armitage, D., Berkes, F., and Doubleday, N. (2010). Adaptive co-management: Collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance. Sustainability and the environment. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Baker, S., Ayala-Orozco, B., and García-Frapolli, E. (2020). Hybrid, public and private environmental governance: the case of sustainable coastal zone management in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 27, 625–637. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2020.1722764

Beaumier, G., Couette, C., and Morin, J.-F. (2025). Hybrid organisations and governance systems: the case of the European Space Agency. J. Eur. Public Policy 32, 1004–1034. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2024.2325647

Biedenkopf, K. (2022). “Hazardous waste: fragmented governance and aspirations for environmental justice” in Eds. P. G. Harris, Routledge handbook of global environmental politics, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781003008873

Boakye-Danquah, J., Reed, M. G., Robson, J. P., and Sato, T. (2018). A problem of social fit? Assessing the role of bridging organizations in the recoupling of socio-ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 223, 338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.042,

Braun, Virginia, and Clarke, Victoria. 2021. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: SAGE Publications.

Cisneros, P. (2019). What makes collaborative water governance partnerships resilient to policy change? A comparative study of two cases in Ecuador. Ecol. Soc. 24:129. doi: 10.5751/ES-10667-240129

Clarke-Sather, A., Crow-Miller, B., Banister, J. M., Thomas, K. A., Norman, E. S., and Stephenson, S. R. (2017). The shifting geopolitics of water in the Anthropocene. Geopolitics 22, 332–359. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1282279

Cleaver, F., and Whaley, L. (2018). Understanding process, power, and meaning in adaptive governance: a critical institutional reading. Ecol. Soc. 23:49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26799116

Crona, B., and Hubacek, K. (2010). The right connections: how do social networks lubricate the machinery of natural resource governance? Ecol. Soc. 15:418. doi: 10.5751/ES-03731-150418

Crona, B. I., and Parker, J. N. (2012). Learning in support of governance: theories, methods, and a framework to assess how bridging organizations contribute to adaptive resource governance. Ecol. Soc. 17:19. doi: 10.5751/ES-04534-170132

Deng, B., Xie, W., Cheng, F., Deng, J., and Long, L. (2021). Complexity relationship between power and trust in hybrid megaproject governance: the structural equation modelling approach. Complexity 2021:8814630. doi: 10.1155/2021/8814630

Domptail, S., Easdale, M. H., and Yuerlita, (2013). Managing socio-ecological systems to achieve sustainability: a study of resilience and robustness. Environ. Policy Gov. 23, 30–45. doi: 10.1002/eet.1604

FAO (2021). State of the world’s land and water resources for food and agriculture – Systems at Breaking Point. Rome, FAO.

Fleischman, F. D., Boenning, K., Garcia-Lopez, G. A., Mincey, S., Schmitt-Harsh, M., Daedlow, K., et al. (2010). Disturbance, response, and persistence in self-organized forested communities: analysis of robustness and resilience in five communities in southern Indiana. Ecol. Soc. 15:9. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268203,

Gain, A. K., Hossain, S., Benson, D., Di Baldassarre, G., Giupponi, C., and Huq, N. (2021). Social-ecological system approaches for water resources management. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 28, 109–124. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2020.1780647

Ghosh, R., and Wolf, S. (2021). Hybrid governance and performances of environmental accounting. J. Environ. Manag. 284:111995. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111995,

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hidayat, A. R., Hospes, O., and Termeer, C. J. a. M. (2025). Why democratization and decentralization in Indonesia have mixed results on the ground: a systematic literature review. Public Adm. Dev. 45, 159–172. doi: 10.1002/pad.2095

Lemos, M. C., and Agrawal, A. (2006). Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 31, 297–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.31.042605.135621

Li, Y., Koppenjan, J., and Verweij, S. (2016). Governing environmental conflicts in China: under what conditions do local governments compromise? Public Adm. 94, 806–822. doi: 10.1111/padm.12263

Minneti, J. J. (2018). Environmental governance and the global south. William Mary Environ. Law Policy Rev. 43:83.

Naibaho, B. B. S., and Su, S. J. (2025). Strengthening collaborative governance: implementing the Pentahelix approach to address challenges in the Toba caldera UNESCO global geopark, Indonesia. Geoconserv. Res. 8:802. doi: 10.57647/j.gcr.2025.0801.02

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2019). The role of governance modes and Meta-governance in the transformation towards sustainable water governance. Environ. Sci. Pol. 91, 6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.10.008,

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Pirard, R., Pacheco, P., and Romero, C. (2023). The role of hybrid governance in supporting deforestation-free trade. Ecol. Econ. 210:107867. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107867

Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M. M. B., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., et al., eds. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change.

Prutzer, M., Morf, A., and Nolbrant, P. (2021). Social learning: methods matter but facilitation and supportive context are key—insights from water governance in Sweden. Water 13:2335. doi: 10.3390/w13172335

Reyes, V. (2020). Contractual and stewardship timescapes: the cultural logics of US–Philippines environmental conflict and negotiations. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 51, 616–629. doi: 10.1017/S0022463420000727

Robinson, J., Klimczak, P., and Smyth, N. (2023). An innovative approach to accommodate the draft National Mine Closure Strategy in South Africa by predicting pit Lake water quality and generating a post closure resource using passive treatment. Mine closure 2023: 16th international conference on mine closure, 2023 2–5 October 2023, Reno. Australian Centre for Geomechanics.

Roy, S., Majumder, S., Bose, A., and Chowdhury, I. R. (2024). Mapping the vulnerable: a framework for analyzing urban social vulnerability and its societal impact. Soc. Impacts 3:100049. doi: 10.1016/j.socimp.2024.100049

Santos, E. (2025). Nature-based solutions for water management in Europe: what works, what does not, and what’s next? Water 17:2193. doi: 10.3390/w17152193

Schmidt, N. M., and Fleig, A. (2018). Global patterns of National Climate Policies: Analyzing 171 country portfolios on climate policy integration. Environ. Sci. Pol. 84, 177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.03.003,

Shunglu, R., Köpke, S., Kanoi, L., Nissanka, T. S., Withanachchi, C. R., Gamage, D. U., et al. (2022). Barriers in participative water governance: a critical analysis of community development approaches. Water 14:762. doi: 10.3390/w14050762

Spanuth, A., and Urbano, D. (2024). Exploring social enterprise legitimacy within ecosystems from an institutional approach: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 26, 211–231. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12349

St-Gelais, N. F., Jokela, A., and Beisner, B. E. (2018). Limited functional responses of plankton food webs in northern lakes following diamond mining. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 75, 26–35. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2016-0418

Syam, R. (2025). Research trends in environmental sociology: A bibliometric analysis of scientific publications from 1976 to 2024. Paris, France: IIETA.

Toxopeus, H., Kotsila, P., Conde, M., Katona, A., van der Jagt, A. P. N., and Polzin, F. (2020). How ‘just’ is hybrid governance of urban nature-based solutions? Cities 105:102839. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102839,

UNEP 2023. “Global environment outlook 7: living within earth’s limits.” global environment outlook (GEO). Available online at: http://www.unep.org/geo/global-environment-outlook-7 (Accessed July 10, 2025).

UNESCO (2022). World water development report 2022: Groundwater – Making the invisible visible. Paris: UNESCO.

van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., and Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: is meaning lost in translation? Eur. J. Ageing 7, 313–316. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y,

Vujanovic, P. (2017). Decentralisation to promote regional development in Indonesia. OECD Econ. Depart. Work. Papers 1380, 6–37. doi: 10.1787/d9cabd0a-en

Wahyono, A., Yoga, G. P., Subehi, L., Rustini, H. A., Fakhrudin, M., Apip, A., et al. (2025). Building a collaborative environmental governance for sustainable Management of a Volcanic Lake at the Dieng plateau in Central Java Indonesia. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 21, 833–842. doi: 10.1093/inteam/vjaf020,

Wang, Y., Zang, L., and Araral, E. (2020). The impacts of land fragmentation on irrigation collective action: empirical test of the social-ecological system framework in China. J. Rural. Stud. 78, 234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.005,

World Bank (2024). Water security and sustainable growth in a changing climate. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yasmin, F., Sakib, T. U., Emon, S. Z., Bari, L., and Sultana, G. N. N. (2022). The physicochemical and microbiological quality assessment of Maddhapara hard rock-mine discharged water in Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Resourc. Environ. Sustain. 8:100061. doi: 10.1016/j.resenv.2022.100061,

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Keywords: environmental governance, lake, local government, mining region, socio-ecological sustainability

Citation: Syam R, Wisadirana D, Susilo E, Nurhadi I and Latief MI (2026) Stitching sustainability: local governments as mediators in hybrid environmental governance of mining-lake regions. Front. Sustain. 6:1745521. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1745521

Edited by:

Jose M. Cruz, University of Connecticut System, United StatesReviewed by:

Robert Newell, Royal Roads University, CanadaBing Baltazar Brillo, University of the Philippines Los Banos, Philippines

Copyright © 2026 Syam, Wisadirana, Susilo, Nurhadi and Latief. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ridwan Syam, cmlkd2Fuc3lhbUB1bmhhcy5hYy5pZA==

Ridwan Syam

Ridwan Syam Darsono Wisadirana2

Darsono Wisadirana2