Abstract

Project social value has emerged as a critical dimension of sustainable road infrastructure, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, limited integrative models explain how project social value can be systematically embedded in infrastructure delivery. This study develops a conceptual model to enhance project social value in road construction through a comprehensive synthesis of prior research. The model identifies five factors: community engagement, government role, sustainability practices, organizational performance, and design, represented by 38 indicators. Grounded in stakeholder and sustainability theories, the model positions project processes as the dynamic context through which these determinants interact to generate social outcomes. The study advances theoretical understanding by integrating social and technical dimension of sustainability, and provide practical guidance for policy makers, managers, and practitioners to embed social value principle within infrastructure planning and delivery.

1 Introduction

Infrastructure projects, particularly road construction, significantly influence a nation’s economic development by enhancing accessibility, mitigating inequality, and fostering local economic advancement (Khan et al., 2021; Chan et al., 2022). Road construction projects not only serve to improve connectivity and facilitate mobility, but can also have other positive effects, such as opening access to remote areas, creating jobs, and improving the quality of life of the community. Considering that road construction projects immediately engage with and affect adjacent communities, it ought to be conceived and executed to provide significant social value. This involves meeting the project’s technical specifications while simultaneously guaranteeing that the results enhance social welfare, empower communities, and provide equitable access to opportunities.

Social value in infrastructure development refers to the supplementary social, economic, and environmental advantages produced by a project beyond its core functional objective (Raiden and King, 2021). The social value of a project encompasses its conclusion, along with the anticipated long-term benefits and impacts for stakeholders and the broader community (Cartigny and Lord, 2017; Gidigah et al., 2022). This social value is crucial and can significantly impact a project’s success or failure (Chipulu et al., 2014). Integrating social values into construction projects is crucial to ensure that the benefits of development are not limited to a small group of people or specific parties but are enjoyed by the entire community, including vulnerable groups. A project’s social value has become an indicator of construction project success, reflecting a recent shift in the paradigm (Gyadu-Asiedu et al., 2024; Ika and Pinto, 2022).

Traditionally, construction projects have focused on achieving the triple constraints of time, cost, and quality. Project managers tend to focus their efforts on controlling costs within budget, ensuring timely completion, and achieving desired quality standards. These three aspects form the primary basis for decision-making, planning, and implementation of construction projects (Van Wyngaard et al., 2012). However, a paradigm shift has occurred whereby the success of a project is measured not only by these three constraints but also by the social value the project creates for the community. Road projects should not be judged solely on technical and financial metrics but also on their ability to create meaningful and sustainable social value. This paradigm shift, reflected in the integration of social, environmental, and economic considerations, is often referred to as the triple bottom line (Elkington and Rowlands, 1999), has positioned social value as a crucial measure of project success, particularly for publicly funded infrastructure that directly impacts communities. This shift in perspective emphasises the necessity of success indicators that go beyond conventional financial and technical measurements. From this perspective, integrating social value into road construction projects is not only a managerial concern but also a strategic mechanism for operationalising the SDGs at the project level.

Despite the increasing alignment between infrastructure development, social value, and the SDGs, existing research in construction and infrastructure management remains fragmented. Prior studies have often examined through isolated lenses such as community engagement, sustainability practices, or at a single project stage, without offering an integrated conceptual framework specifically tailored to road construction projects. As a result, there is a limited systematic understanding of how these diverse elements collectively contribute to social value creation and SDG achievement in road infrastructure development.

To address this gap, this study adopts a narrative review approach to synthesise existing literature on social value in road construction projects. By integrating insights from multiple theoretical perspectives and develops a coherent conceptual framework. The proposed framework aims to support both researchers and practitioners in better understanding, assessing, and embedding social value in road construction projects, while also contributing to the practical implementation of the SDGs within the infrastructure sector.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Social value in construction

The social value of a project is its functional utility for life and shared goals, so it is neither absolute nor relative (Choi, 2014). A project’s social value must be viewed as “worth” because it encompasses the project’s outputs and outcomes (Martinsuo et al., 2019). The concept of “social value” in construction projects refers to the potential benefits a project can offer to local communities and the wider community. These benefits can be both long-term and short-term, ranging from employment or housing to public facilities and sustainability.

Social value in the construction industry encompasses the additional benefits that contribute to community well-being, social inclusion, and sustainable development (

Raidén et al., 2019). In road projects, these benefits can include reduced transport inequality, improved access to essential services, job creation, and skills development for local populations. The construction industry, particularly projects, has unique characteristics compared to the manufacturing industry. Projects with a high degree of variability and change in design, location, production environment, and supply chain structure are used to carry out their task (

Raiden et al., 2018).

Raiden et al. (2018)also state that each project offers different social value, which depends on several factors, including:

Project size. Larger projects typically could offer more social value than smaller projects.

Project type. Economic infrastructure, such as roads and railways, offers significant social value opportunities due to the large number of communities they impact. Social infrastructure (schools, hospitals, etc.) offers social value based on the nature of its operations, for example, in education and healthcare. Housing provides other forms of social value related to security, comfort, a sense of home, family cohesion, and wealth creation.

The project’s location. Because there are more community needs and chances to hire underprivileged local communities, projects in low-socioeconomic areas usually have a larger social value proposition.

Innovative project design, urban design, and buildings promote safe and healthy living and generate economic value by attracting new businesses to an area. Materials specified in the design can be sourced from responsible suppliers, creating social value in their production, and the construction technologies implied by the design can create or destroy job opportunities.

Integrated procurement helps reduce the focus on short-term gains and encourages more sustainable solutions, like energy-efficient technologies that lower overall costs. It also allows more people involved, like building users and the community, to work together. Integrated procurement also offers more opportunities for stakeholders (such as creating users and the community) to share and collaborate on project outcomes.

Local supply chains: The use of local businesses and social enterprises in a project’s supply chain can create employment and business opportunities for local and disadvantaged groups.

Timing (the political, social, and economic context in which a project is constructed): By preserving jobs, projects constructed during a recession can add greater social benefit. There are more incentives and chances to add social value to the project if the government is politically willing to take social value into account throughout the bidding process.

The concept of ‘social value’ in construction projects refers to the potential benefits a project can offer to local communities and society. These benefits can be long-term and short-term, ranging from employment or housing to public facilities and sustainability. The social value of a project must be seen as “worth” because it is in the form of project output and outcomes resulting from the project (Vuorinen and Martinsuo, 2019). In practice, social value in construction projects is influenced by legislation, procurement, and increasing public demand for CSR (Raiden et al., 2018).

According to

Martin (1997)and

Green and Sergeeva (2019)several criteria can be used to evaluate whether a project has succeeded in creating social value. These criteria include:

Achievement of social objectives. This criterion covers the extent to which the project achieves its stated social goals, such as improving the quality of life, reducing poverty, or creating jobs.

Increased Economic Benefits. This criterion covers the economic benefits generated by the project for owners, managers, and the community at large.

Equity and Inclusion. This criterion covers the extent to which the project addresses social justice and inclusion, including how it benefits marginalised or vulnerable groups.

Capacity Development. This criterion encompasses the capacity building of individuals or communities involved in the project, including the acquisition of increased skills, knowledge, and the ability to participate in decision-making processes.

Stakeholder Perception and Satisfaction. This criterion covers how well the project meets their expectations and needs.

Long-Term Impact. This criterion covers the sustainable positive changes in social, economic, and environmental conditions resulting from the project.

Social Innovation: This criterion includes the extent to which the project creates innovative solutions to existing social problems, as well as the ability to inspire other projects or broader policies.

2.2 Relevant theoretical perspectives

2.2.1 Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory was initially proposed by Freeman (1984), who asserted that organisations bear responsibility not solely to shareholders but also to all entities with a vested interest in the organisation’s operations. Parmar et al. (2010) assert that stakeholder theory has developed into normative and instrumental frameworks. This idea underscores the significance of honouring the interests of each stakeholder as an intrinsic value. This approach is viewed as a method to enhance organisational performance by augmenting legitimacy, trust, and stakeholder support. In construction projects, stakeholders can be diverse, encompassing a range of entities, including project owners and contractors, government agencies, and the surrounding community. Identifying stakeholders early in a project is important in guaranteeing its success. It’s crucial to analyse the level of interest, expectations, concerns, and influence of each stakeholder.

Furthermore, a bibliometric review by Mahajan et al. (2023) confirms the rapid growth of this research since 2000. From 988 articles (1969–2021), they identified four main clusters: stakeholder theory and sustainability, stakeholder theory and organisational performance, stakeholder theory and strategic management, and stakeholder theory and stakeholder management. This mapping demonstrates that stakeholder theory is relevant not only to business but also to the public sector and infrastructure projects.

The implementation of Stakeholder Theory is essential in infrastructure projects, especially road projects, as they directly engage with the broader community, governmental entities, contractors, and the business sector. The normative approach underscores the ethical duty to guarantee that the project provides equal social benefit to impacted communities, but the instrumental perspective asserts that technical success (cost, quality, time) will be more sustainable if stakeholder interests are duly considered. Consequently, Stakeholder Theory can provide a robust theoretical framework to elucidate why the generation of social value ought to be a principal aim in road construction.

Although Stakeholder Theory has been recognised as a relevant conceptual framework for explaining stakeholder involvement in projects, its implementation in project management practice still faces various obstacles. The results of the study by Wojewnik-Filipkowska et al. (2019) show that the complexity of relationships between stakeholders, limited communication, and conflicts of interest often hinder the practical application of this theory in real projects. In the context of construction projects, project managers tend to focus more on achieving the iron triangle (cost, quality, and time). At the same time, the aspect of creating social value is often placed as a secondary priority.

2.2.2 Sustainability theory

The concept of sustainability, popularised by the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987), emphasises development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Rivai and Rohman, 2020; Srivastava et al., 2021). Sustainability is generally conceptualised through three interdependent pillars: economic, environmental, and social, which is known as the triple bottom line (Silvius and Schipper, 2014). While economic and environmental aspects have received significant attention in infrastructure projects, the social dimension often remains underexplored despite its crucial role in ensuring the long-term well-being of society (Hidayat et al., 2020; Rivai and Rohman, 2020; Wang et al., 2018). To achieve optimal social sustainability in development, it is crucial to integrate social values into every construction project. By considering the social impacts they generate, construction projects can meet economic and environmental goals and provide tangible benefits to the broader well-being of society.

In relation to stakeholder theory, sustainability theory extends the discussion from identifying who is affected by a project to evaluating how the project outcomes affect them. This aligns with the necessity of embedding social sustainability within road construction projects, ensuring that infrastructure not only functions as a physical asset but also as a catalyst for inclusive and equitable development. The integration of sustainability theory also aligns with global development agendas, particularly the Sustainable Development Goals (Lee et al., 2016), especially SDG 9 on resilient infrastructure and SDG 11 on sustainable communities. Well-designed roads can enhance mobility, facilitate access to education and health care, and stimulate local economies, thereby supporting both economic and social objectives (Acheampong and Silva, 2015; Hidayat et al., 2020).

3 Methodological approach

This study adopts a narrative review approach to examine the integration of social value within road construction projects. This approach allows for greater flexibility in synthesising diverse theoretical perspectives and conceptual debates, which is particularly appropriate given the exploratory aim of the study to develop a theoretical model that explains the factors influencing social value creation in infrastructure projects, especially road projects.

The literature analysis primarily focused on peer-reviewed journal articles to ensure conceptual robustness and academic rigour. Conference papers and academic books were used selectively to complement theoretical discussion, while theses and dissertations were consulted only during the initial scoping stage to contextualise the research domain, rather than serving as primary sources for factor or indicator derivation.

The analysis process followed a structured conceptual synthesis strategy. First, relevant literature addressing social value, stakeholder theory, sustainability, and road infrastructure development was screened. Key concepts, themes, and social value-related indicators were then systematically extracted from the selected studies and compiled into an initial pool of indicators.

Subsequently, a synthesis and clustering process was undertaken to group conceptually similar indicators based on theoretical affinity and thematic relevance. Through this process, indicators were organised into five higher-order factors representing the main dimensions influencing social value creation in road construction projects.

Finally, the resulting factor-indicator structure was reviewed to ensure internal consistency, conceptual clarity, and relevance to road infrastructure projects. The outcome of this process is a conceptual model for optimizing project social value in road construction projects.

4 Factors influencing social value in road construction projects

Social value in construction extends beyond the physical completion of a project, encompassing long-term benefits such as improved quality of life, public facilities, and employment opportunities that ensure lasting positive impacts for future generations. It has become a crucial dimension of project success, reflecting an organisation’s commitment to social responsibility and community well-being. In road construction projects, social value is particularly significant due to their direct, prolonged, and spatially embedded interactions with local communities, users, and surrounding environments. Projects that embed social principles from the outset can foster trust, minimise conflict, and enhance corporate reputation, transforming social value into a strategic investment rather than a mere obligation.

Building on the synthesis of the reviewed literature, this study identifies and classifies the key factors influencing the achievement of social value in road construction projects. Through a structured factor synthesis process, five interrelated determinants supported by a total of 38 indicators were derived and are summarised in Table 1. These factors represent higher-order dimensions emerging from recurring themes in the literature and reflect both governance-related and practice-oriented perspectives on social value creation.

Table 1

Factors influencing social value in road construction projects.

According to Table 1 above, five main factors were identified that influence the achievement of project social value in road construction projects. These five factors are: community involvement, government role, project sustainability practices, project organisational performance, and design. Community engagement is central, as projects that actively involve communities are more likely to generate ownership, trust, and long-term social benefits (Dare et al., 2014). This finding is consistent with the social sustainability literature, which emphasises participatory processes as a foundation for inclusive and socially responsive infrastructure development.

The government’s role is equally significant, since the policy frameworks, regulations, and financial mechanisms determine the enabling environment for project social value (Albareda et al., 2007). Moreover, project sustainability practices ensure that infrastructure development balances environmental responsibility with social justice, while organisational performance influences how effectively stakeholders’ expectations are translated into tangible outcomes. Design, as the last factor, directly affects inclusiveness, safety, and cultural identity, thereby shaping the everyday experience of communities that use and live around road infrastructure (Rohman and Wiguna, 2021).

Taken together, these five factors provide an integrated conceptual lens for understanding how social value is created, embedded, and sustained throughout the lifecycle of road construction projects. The importance of governance, public involvement, and institutional capacity as key facilitators of social sustainability outcomes is also highlighted in recent research on smart and sustainable cities (Kumar et al., 2025).

5 Toward a conceptual model

The synthesis of influencing factors indicates that social value in road construction projects is not the outcome of a single dimension but rather the result of dynamic interactions among multiple categories. Drawing on stakeholder theory and sustainability principles, this study identifies five key determinants: community engagement, government role, sustainability practices, organisational performance, and design. Each factor represents a distinct yet complementary dimension. Community engagement highlights the alignment of project outcomes with local needs and legitimacy, while the government’s role emphasizes regulatory and institutional support. Sustainability practices underscore the integration of environmental and social responsibility, organizational performance reflects managerial and institutional capacity, and design captures inclusiveness and functionality for end users. Together, these determinants provide the foundation for understanding how social value can be achieved in infrastructure delivery, especially road infrastructure.

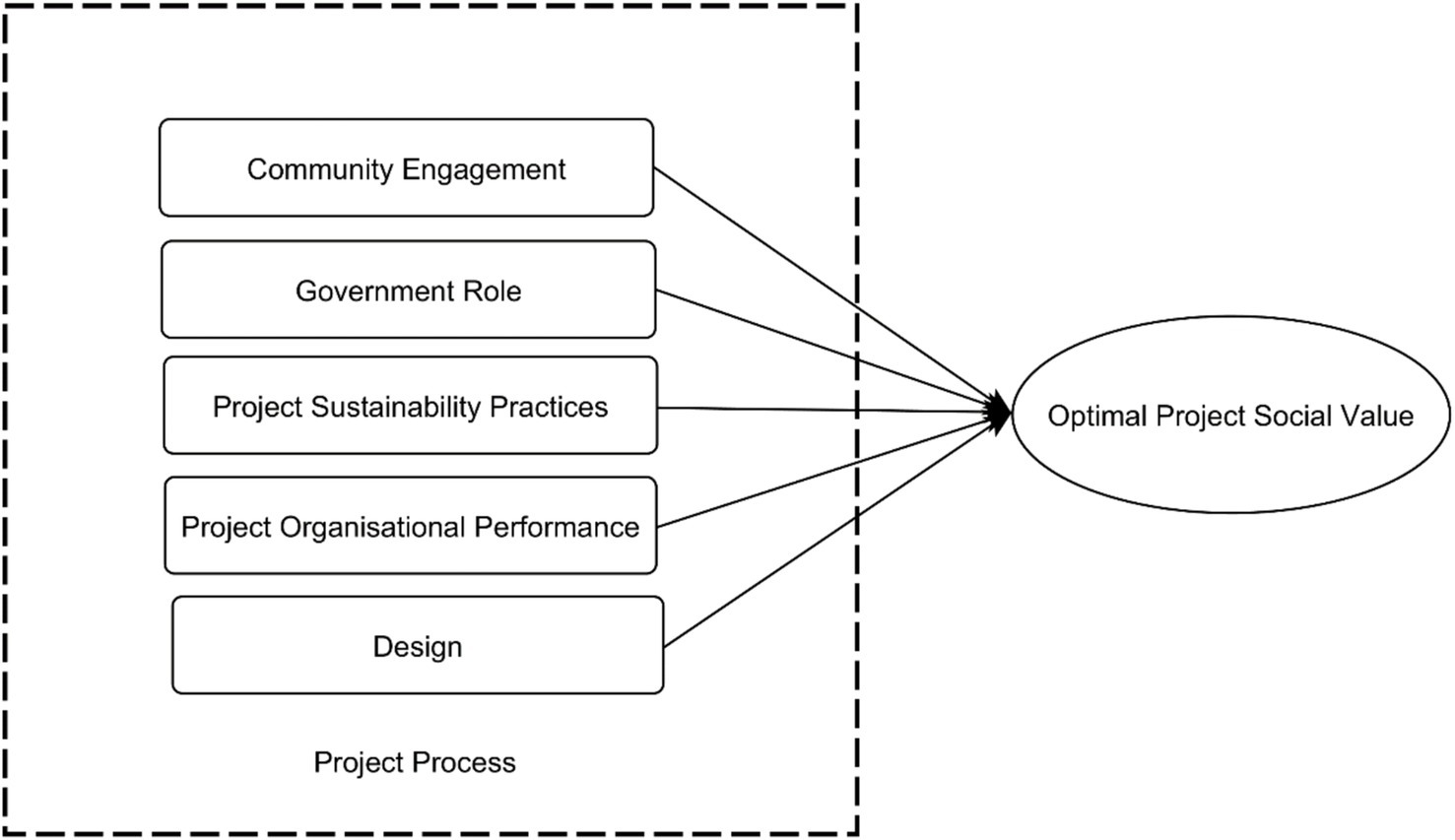

Based on this synthesis, a conceptual framework is proposed in Figure 1. The framework positions project processes (dashed-line box) as the context in which the five determinants: community engagement, government role, project sustainability practices, organizational performance and design emerge and exert their influence. The dashed line boundary denotes the project process domain, emphasizing that these determinants manifest and interact throughout project delivery rather than acting as isolated variables. The arrows indicate directional influence toward the project’s social value outcome (oval), clarifying how value is co-produced through the inclusion, government support, sustainability integration, organizational capability, and design. The indicators derived from the literature for each factor are presented in Table 1, while the detailed elaboration of how these factors influence project social value is provided in the discussion section.

Figure 1

A conceptual model to optimise project social value.

6 Discussion

Building on the proposed conceptual model, this section elaborates on how each determinant contributes to the achievement of project social value in road construction projects. The relative importance of these factors and their indicators may vary across different project stages. For instance, community involvement is crucial during the planning and design stages but becomes less important during the implementation stage. Meanwhile, organisational performance and sustainability practices are essential during the implementation stage but become less important during the operational stage. This dynamic variation reflects the project process domain in the conceptual model, which illustrates that the determinants emerge and interact across different phases of project delivery. Therefore, a factor synthesis process is necessary to determine which factors and indicators are most influential in shaping project social value.

Community engagement is the first factor that influences the achievement of the project’s social value. Engaging communities in project planning and execution increases the likelihood of tailoring the project to align with local requirements, expectations, and values. This ensures that the project provides direct benefits to affected communities. Community involvement can increase support and acceptance of the project, reducing the risk of resistance or social conflict (Conde and Le Billon, 2017). Engaging the community can help identify potential social risks and adverse impacts early in the project lifecycle (Haddaway et al., 2017). Mechanistically, meaningful participation and transparent, responsive communication foster perceived fairness and shared ownership, while an accessible grievance redress channel converts potential disputes into collaborative problem solving, thereby safeguarding long-term community benefits (Yang et al., 2009). In archipelagic road contexts, where access, livelihoods, and land issues are sensitive, these mechanisms are decisive. This proactive approach enables the development of mitigation plans, ensuring that the project will contribute positively to the community rather than unintentionally harming it. Effective community participation raises the probability that a project will endure over time. Community engagement emerges as a central driver of social value in infrastructure projects, yet its effectiveness depends on the quality of interaction rather than the mere existence of participation. Similar findings are reported in the social infrastructure literature, which highlights that participation is most impactful when it fosters inclusiveness, accountability and collaborative governance (Mashabela et al., 2025). Leung and Yu (2014) demonstrate that structured approaches such as Value Methodology (VM) can provide a logical and neutral framework for dialogue, transforming destructive conflict into constructive outcomes that strengthen trust, team spirit, and organisational reputation.

The government is essential in several areas, including capacity building, long-term strategic goal formulation, community involvement, financial support, partnerships, and regulatory framework (Ofori, 2015). When taken as a whole, these steps improve a project’s potential to produce significant social value and support sustainable development. The rules and guidelines that direct the creation and execution of projects are set by and enforced by governments. These laws have the power to require specific social and environmental factors, guaranteeing that projects make a beneficial contribution to sustainability and societal well-being. The government can provide grants, loans, and other forms of financial aid to construction projects that aim to generate social benefits.

Sustainability practices play a pivotal role in determining the extent to which road infrastructure contributes to long-term social value. Sustainability in construction projects is often linked to the creation of healthier and safer living environments, which directly improves the quality of life of local communities. Sustainability practices aim to minimise the negative impacts of construction projects on the environment (Yusof et al., 2017). Embedding sustainability into project practices, such as minimising carbon emissions, effective waste management, and ensuring social justice, can enhance both the perceived legitimacy and tangible benefits of infrastructure. According to Kaur and Pandey (2021) Sustainable road projects must adopt practices such as the use of low-emission construction technologies, environmentally friendly materials, and effective dust and pollution control strategies. These measures not only mitigate the ecological footprint of infrastructure projects but also contribute directly to improving local air quality and community well-being. Road projects can make a tangible contribution to global goals, such as SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), by integrating sustainability practices with the mitigation of climate change and its associated public health implications. By establishing environmental management as essential to the legitimacy and acceptance of infrastructure development, this highlights the role of sustainability as a catalyst for creating social value.

Project organisational performance is crucial to achieving social value because it encompasses how well an organisation manages and executes its projects. High organisational performance ensures the effective management of resources, including staff, money, and time (Kerzner, 2016). The findings of Raiden and King (2021) reinforce the discussion on project organisational performance as a critical factor in achieving social value. This article emphasises that organisational performance cannot be measured solely by traditional indicators (cost, quality, time), but rather through the organisation’s ability to learn, adapt, and collaborate to create social value. Organisational learning enables contractors, clients, and others to internalise social value into their strategies, policies, and work culture. Similarly, Felício et al. (2013) demonstrated that transformational leadership and social entrepreneurship are essential drivers linking social value to organisational performance, fostering innovation and responsiveness to societal needs. This suggests that project organisations achieve stronger performance when they combine efficiency with leadership, innovation, and learning capacity that enable the systematic creation of social value.

Design is the last influencing factor to achieve the project’s social value. The design has a significant influence on the project’s social value achievement because it directly impacts how a project serves and benefits the community. The project will satisfy the demands and preferences of the end-users if it is designed with them in mind. Because the initiative offers solutions that are pertinent to and beneficial to the community, this strategy increases user happiness and utility. Community acceptance of projects is higher when they honour and reflect local aesthetics and culture (Brooks et al., 2012). The social value of the project is increased by the citizens’ sense of identity and pride, which is fostered by this cultural alignment. As stated by Barton et al. (2021) that projects designed with accessibility in mind tend to deliver higher social value because they serve the needs of a wider audience. Design quality influences social value through user-centricity (safety, inclusivity, accessibility), placemaking (cultural resonance, aesthetics), and whole life performance (durability, adaptability, lifecycle benefits). In practice, design reviews should adopt social value as gatekeeping elements, ensuring that road projects integrate safety audits, inclusivity features, and context-sensitive elements from the early planning stages.

The conceptual model supports the broader agenda of smart and sustainable cities by integrating social, institutional and design dimensions that align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) and SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities). This linkage highlights the model’s relevance for advancing holistic sustainability in infrastructure planning and management. By translating abstract social value principles into a structured set of factors and indicators, the model provides a practical reference for integrating social considerations into road infrastructure decision-making and governance.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the proposed model is derived solely from a synthesis of prior literature and has not yet been empirically validated. Second, the scope is limited to road infrastructure projects, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other types of infrastructure. Third, the reviewed studies are geographically uneven, with a concentration in specific region, which may introduce contextual bias and limit the applicability of the model across different socio-institutional settings.

Future research should address these limitations by empirically validating the model through expert evaluations and stakeholder surveys. Statistical techniques such as multiple regression or structural equation modelling could be applied to test the hypothesis relationships across diverse project contexts. Beyond validation, advanced approaches such as Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) may be employed to build predictive models of project social value, enabling scenario analysis and decision support tools for policy makers and practitioners.

7 Conclusion

Project social value is the result of a project, as well as the long-term benefits and impacts expected from the project for stakeholders and the broader community. To optimise the achievement of the project’s social value, it is necessary to identify factors that influence the social value of a construction project. Five primary factors impacting the results of the literature study were identified, namely community engagement, government role, project sustainability practices, project organisational performance, and design. These five factors depend on 38 indicators that are divided into community engagement, which consists of eight indicators; government role, which consists of five indicators; project sustainability practices, which consists of nine indicators; project organisational performance, which consists of seven indicators; and design, which consists of eleven indicators. Together, these factors provide a structured framework for understanding how social value can be systematically embedded in infrastructure delivery.

Theoretically, the model advances social value research by integrating stakeholder and sustainability perspectives into a structured framework tailored to infrastructure projects. Practically, it provides a diagnostic tool for policymakers and practitioners to embed social value considerations into project design, procurement, and delivery processes.

As the model is based solely on literature synthesis, it has not been empirically validated. Future research should operationalise the identified factors into measurable constructs, test them across diverse project contexts, and explore predictive approaches such as ANFIS to simulate policy and project scenarios.

Statements

Author contributions

NM: Conceptualization, Resources, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Data curation. MR: Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. IW: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia, for providing doctoral scholarship support to the first author.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abdel-Raheem M. Ramsbottom C. (2016). Factors affecting social sustainability in highway projects in Missouri. Procedia Eng.145, 548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.04.043

2

Acheampong R. A. Silva E. A. (2015). Land use? Transport interaction modeling a review of the literature and future research directions. J. Transp. Land Use8, 11–38. doi: 10.5198/jtlu.2015.806

3

Agyekum K. Botchway S. Y. Adinyira E. Opoku A. (2021). Environmental performance indicators for assessing sustainability of projects in the Ghanaian construction industry. Smart Sustain. Built Environ.11, 918–950. doi: 10.1108/sasbe-11-2020-0161

4

Albareda L. Lozano J. M. Ysa T. (2007). Public policies on corporate social responsibility: the role of governments in Europe. J. Bus. Ethics74, 391–407. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9514-1

5

Bamgbade J. A. Kamaruddeen A. M. Nawi M. N. M. Adeleke A. Q. Salimon M. G. Ajibike W. A. (2019). Analysis of some factors driving ecological sustainability in construction firms. J. Clean. Prod.208, 1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.229

6

Barton H. Grant M. Guise R. (2021). Shaping neighbourhoods: For local health and global sustainability. London: Routledge.

7

Brooks J. S. Waylen K. A. Borgerhoff Mulder M. (2012). How national context, project design, and local community characteristics influence success in community-based conservation projects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA109, 21265–21270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207141110

8

Cartigny T. Lord W. (2017). Defining social value in the UK construction industry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.170, 107–114. doi: 10.1680/jmapl.15.00056

9

Chan M. Jin H. van Kan D. Vrcelj Z. (2022). Developing an innovative assessment framework for sustainable infrastructure development. J. Clean. Prod.368:133185. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133185

10

Chan E. Lee G. K. L. (2008). Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc. Indic. Res.85, 243–256. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9089-3

11

Chipulu M. Ojiako U. Gardiner P. Williams T. Mota C. Maguire S. et al . (2014). Exploring the impact of cultural values on project performance: the effects of cultural values, age and gender on the perceived importance of project success/failure factors. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag.34, 364–389. doi: 10.1108/IJOPM-04-2012-0156

12

Choi Y. (2014). Measuring social values of design in the commercial sector. London: Brunel University London.

13

Conde M. Le Billon P. (2017). Why do some communities resist mining projects while others do not?Extr. Ind. Soc.4, 681–697. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2017.04.009

14

Damoah I. S. Kumi D. K. (2018). Causes of government construction projects failure in an emerging economy: evidence from Ghana. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus.11, 558–582. doi: 10.1108/IJMPB-04-2017-0042

15

Dare M. Schirmer J. Vanclay F. (2014). Community engagement and social licence to operate. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais.32, 188–197. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2014.927108

16

Elkington J. Rowlands I. H. (1999). Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of 21st century business. Alternatives J.25:42. doi: 10.5860/choice.36-3997

17

Erkul M. Yitmen I. Çelik T. (2016). Stakeholder engagement in mega transport infrastructure projects. Procedia Engineering161, 704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.745

18

Felício J. A. Martins Gonçalves H. da Conceição Gonçalves V. (2013). Social value and organizational performance in non-profit social organizations: social entrepreneurship, leadership, and socioeconomic context effects. J. Bus. Res.66, 2139–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.040

19

Freeman R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston, MA: Pitman.

20

Fujiwara D. Dass D. King E. Vriend M. Houston R. Keohane K. (2021). A framework for measuring social value in infrastructure and built environment projects: an industry perspective. London: Thomas Telford Ltd, 175–185.

21

Ghimire S. Tuladhar A. Sharma S. R. (2017). Governance in land acquisition and compensation for infrastructure development. Am. J. Civ. Eng.5, 169–178. doi: 10.11648/j.ajce.20170503.17

22

Gidigah B. K. Agyekum K. Baiden B. K. (2022). Defining social value in the public procurement process for works. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag.29, 2245–2267. doi: 10.1108/ecam-10-2020-0848

23

Green S. D. Sergeeva N. (2019). Value creation in projects: towards a narrative perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag.37, 636–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.12.004

24

Gyadu-Asiedu N. A. Aigbavboa C. Ametepey S. O. (2024). Social value trends in construction research: a bibliometric review of the past decade. Sustainability16:4983. doi: 10.3390/su16124983

25

Haddaway N. R. Kohl C. da Rebelo Silva N. Schiemann J. Spök A. Stewart R. et al . (2017). A framework for stakeholder engagement during systematic reviews and maps in environmental management. Environ. Evid.6, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13750-017-0089-8

26

Hidayat Y. Rohman M. Utomo C. Social sustainability indicators for school buildings in Surabaya. IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science, 2020. IOP Publishing, 012033.

27

Hill R. C. Bowen P. A. (1997). Sustainable construction: principles and a framework for attainment. Constr. Manag. Econ.15, 223–239. doi: 10.1080/014461997372971

28

Huang R. Y. Yeh C. H. (2008). Development of an assessment framework for green highway construction. J. Chin. Inst. Eng.31, 573–585. doi: 10.1080/02533839.2008.9671412

29

Ika L. A. Pinto J. K. (2022). The “re-meaning” of project success: updating and recalibrating for a modern project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag.40, 835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2022.08.001

30

Kaur R. Pandey P. (2021). Air pollution, climate change, and human health in Indian cities: a brief review. Front. Sustain. Cities3:705131. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.705131

31

Kazancoglu Y. Ozbiltekin-Pala M. Ozkan-Ozen Y. D. (2021). Prediction and evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions for sustainable road transport within Europe. Sustain. Cities Soc.70:102924. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102924

32

Kerzner H. (2016). Project Management: A systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling, WPLS student package: John Wiley & Sons.

33

Khan S. A. R. Godil D. I. Quddoos M. U. Yu Z. Akhtar M. H. Liang Z. (2021). Investigating the nexus between energy, economic growth, and environmental quality: a road map for the sustainable development. Sustain. Dev.29, 835–846. doi: 10.1002/sd.2178

34

Kothari C. France-Mensah J. O’Brien W. J. (2022). Developing a sustainable pavement management plan: economics, environment, and social equity. J. Infrastruct. Syst.28:04022009. doi: 10.1061/(asce)is.1943-555x.0000689

35

Krannich A.-L. Reiser D. (2021). “The United Nations sustainable development goals 2030” in Encyclopedia of sustainable management. Eds. Idowu, R. Schmidpeter, N. Capaldi, L. Zu, M. Del Baldo and R. Abreu. (London: Springer).

36

Kumar H. Gupta A. Singh R. Sayal A. (2025). Toward sustainable social change: strategic approaches to smart city development in developing nations. Front. Sustain. Cities7:1592534. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1592534

37

Lawer E. T. (2019). Examining stakeholder participation and conflicts associated with large scale infrastructure projects: the case of Tema port expansion project, Ghana. Marit. Policy Manag.46, 735–756. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2019.1627013

38

Lee B. X. Kjaerulf F. Turner S. Cohen L. Donnelly P. D. Muggah R. et al . (2016). Transforming our world: implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy37, 13–31. doi: 10.1057/s41271-016-0002-7

39

Leung M.-Y. Yu J. (2014). Value methodology in public engagement for construction development projects. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag.4, 55–70. doi: 10.1108/bepam-05-2012-0033

40

Liao P.-C. Xia N.-N. Wu C.-L. Zhang X.-L. Yeh J.-L. (2017). Communicating the corporate social responsibility (CSR) of international contractors: content analysis of CSR reporting. J. Clean. Prod.156, 327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.027

41

Liu Y. van Marrewijk A. Houwing E.-J. Hertogh M. (2019). The co-creation of values-in-use at the front end of infrastructure development programs. Int. J. Proj. Manag.37, 684–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.013

42

Maelissa N. Rohman M. A. Wiguna I. P. A. . (2023). Influencing factors of sustainable highway construction. E3S web of conferences. EDP Sciences

43

Mahajan R. Lim W. M. Sareen M. Kumar S. Panwar R. (2023). Stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Res.166:114104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114104

44

Martin F. (1997). Justifying a high-speed rail project: social value vs. regional growth. Ann. Reg. Sci.31, 155–174. doi: 10.1007/s001680050043

45

Martinsuo M. Klakegg O. J. van Marrewijk A. (2019). Editorial: delivering value in projects and project-based business. Int. J. Proj. Manag.37, 631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.011

46

Mashabela B. J. Gumbo T. Ishola A. A. (2025). Social infrastructure service delivery in South Africa: a bibliometric, visualization, and thematic analysis. Front. Sustain. Cities7:1605180. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1605180

47

Mirzakhani A. Turró M. Behzadfar M. (2023). Factors affecting social sustainability in the historical city centres of Iran. J. Urban.16, 498–527. doi: 10.1080/17549175.2021.2005119

48

Ng S. T. Wong J. M. W. Wong K. K. W. (2013). A public private people partnerships (P4) process framework for infrastructure development in Hong Kong. Cities31, 370–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.12.002

49

Ofori G. (2015). Nature of the construction industry, its needs and its development: a review of four decades of research. J. Constr. Dev. Countr.20:115.

50

Parmar B. L. Freeman R. E. Harrison J. S. Wicks A. C. Purnell L. De Colle S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: the state of the art. Acad. Manage. Ann.4, 403–445. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2010.495581

51

Raiden A. King A. (2021). Social value, organisational learning, and the sustainable development goals in the built environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycling172:105663. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105663

52

Raiden A. Loosemore M. King A. Gorse C. (2018). Social value in construction. London: CRC Press.

53

Raidén A. Loosemore M. King A. Gorse C. A. (2019). Social value in construction. London: Routledge.

54

Rivai F. Rohman M. (2020). A framework for mapping stakeholders interests related social sustainability in residential building. IOP conference series: Materials science and engineering, IOP Publishing, 012003.

55

Rohman M. A. Doloi H. Heywood C. A. (2017). Success criteria of toll road projects from a community societal perspective. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag.7, 32–44. doi: 10.1108/bepam-12-2015-0073

56

Rohman M. A. Wiguna I. P. A. (2021). Evaluation of road design performance in delivering community project social benefits in Indonesian ppp. Int. J. Constr. Manag.21, 1130–1142. doi: 10.1080/15623599.2019.1603095

57

Silvius A. Schipper R. P. (2014). Sustainability in project management: a literature review and impact analysis. Soc. Bus.4, 63–96. doi: 10.1362/204440814x13948909253866

58

Srivastava S. Raniga U. I. Misra S. (2021). A methodological framework for life cycle sustainability assessment of construction projects incorporating TBL and decoupling principles. Sustainability14:197. doi: 10.3390/su14010197

59

Van Wyngaard C. J. Pretorius J.-H. C. Pretorius L. . (2012). Theory of the triple constraint—a conceptual review. IEEE international conference on industrial engineering and engineering management, 2012 2012 Hongkong. IEEE, 1991–1997.

60

Vuorinen L. Martinsuo M. (2019). Value-oriented stakeholder influence on infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag.37, 750–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.10.003

61

Wang H. Zhang X. Lu W. (2018). Improving social sustainability in construction: conceptual framework based on social network analysis. J. Manag. Eng.34:05018012. doi: 10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000607

62

Watts G. N. Dainty A. Fernie S. (2019). Measuring social value in construction. ARCOM 2019 (35th annual conference). Leeds Beckett University: Association of Researchers in Construction Management (ARCOM) Proceedings of the 35th annual conference.

63

Watts G. Higham A. Abowen-Dake R. (2021). The effective creation of social value in infrastructure delivery: Thomas Telford Ltd, 167–174.

64

Wojewnik-Filipkowska A. Dziadkiewicz A. Dryl W. Dryl T. Bęben R. (2019). Obstacles and challenges in applying stakeholder analysis to infrastructure projects: is there a gap between stakeholder theory and practice?J. Prop. Invest. Finance39, 199–222.

65

World Commission on Environment and Development . (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

66

Yang J. Shen G. Q. Ho M. Drew D. S. Chan A. P. C. (2009). Exploring critical success factors for stakeholder management in construction projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag.15, 337–348. doi: 10.3846/1392-3730.2009.15.337-348

67

Yuan H. (2012). A model for evaluating the social performance of construction waste management. Waste Manag.32, 1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.01.028,

68

Yusof N. A. Awang H. Iranmanesh M. (2017). Determinants and outcomes of environmental practices in Malaysian construction projects. J. Clean. Prod.156, 345–354.

69

Zheng X. Easa S. M. Ji T. Jiang Z. (2020). Modeling life-cycle social assessment in sustainable pavement management at project level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess.25, 1106–1118. doi: 10.1007/s11367-020-01743-7

Summary

Keywords

community, conceptual model, design, project social value, road infrastructure, sustainability

Citation

Maelissa N, Rohman MA and Wiguna IPA (2026) Toward better social value creation in road infrastructure: a conceptual model. Front. Sustain. Cities 8:1760070. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2026.1760070

Received

03 December 2025

Revised

15 January 2026

Accepted

26 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

8 - 2026

Edited by

Charles Chen, Hawaii Pacific University, United States

Reviewed by

Essam Almahmoud, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia

Asheem Shrestha, Deakin University, Australia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Maelissa, Rohman and Wiguna.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Arif Rohman, arif@ce.its.ac.id

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.