- Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, NSW, Australia

The drivers and characteristics of trends in aquatic product consumption are a crucial component of fish food system sustainability. The Chinese market for aquatic products is the largest in the world, yet little has been published on the characteristics of the freshwater fish market. This Paper draws on interviews with key informants to understand the social characteristics of the freshwater fish market in Chengdu, Sichuan province. Price, food safety and quality, freshness and local culinary traditions are important influences on patterns of freshwater fish consumption. However, imported species such as pangasius and branded products are increasing in popularity, indicative of changes in the Chengdu freshwater fish market and the Chinese market for aquatic products more generally.

Introduction

The drivers and characteristics of trends in aquatic product consumption are increasingly recognised as a crucial component of fish food system sustainability (Béné et al., 2015; Belton et al., 2018; Bogard et al., 2019). China is the largest consumer of aquatic products globally, and, like the broader Chinese food market, is changing rapidly (Villasante et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Fabinyi et al., 2016). Due to the sheer scale of this market, gaining a better understanding of key market dynamics is crucial—both from an economic perspective for those who supply the market (Rabobank, 2012; Zhou et al., 2014) and from an environmental perspective for those interested in how such aquatic product consumption trends may affect global stock sustainability (Villasante et al., 2013; Fabinyi et al., 2016). This paper aims to describe some of the key social characteristics of the freshwater fish market in Chengdu, and discusses some of the implications of this for the Chinese aquatic product market more broadly.

Considerable attention has focused on the consumption of imported seafoods in China, in particular of endangered or vulnerable species, and those of high value (Villasante et al., 2013; Shea and To, 2017; Purcell et al., 2018; Wang and Somogyi, 2018, 2020; Zheng et al., 2018; Harkell, 2019; Wang et al., 2019). In recent consumer studies, for example, Wang and colleagues have investigated factors affecting consumer preferences for sustainable shellfish (Wang and Somogyi, 2018), and on luxury seafood more broadly (Wang and Somogyi, 2020), while Zheng et al. (2018) focus on consumer intentions for wild salmon.

However, there has been limited attention to patterns of freshwater fish consumption in China in the literature (Xian, 2016). This is likely due in part to the fact that freshwater species, in general, tend to be less economically higher-valued than their marine counterparts in China. In a recent study of luxury seafood in China, for example, almost all of the species classed as ‘luxury’ were marine species (Wang and Somogyi, 2020). Additionally, many of the aquatic products commonly consumed in China that inspire concerns about the sustainability of capture fisheries are marine (e.g., sea cucumbers, shark fin, groupers, many types of shellfish). This means that the freshwater fish market has generated less attention from economic and environmental sustainability perspectives, mirroring broader patterns documented in the literature for the ‘forgotten’ inland [freshwater] fisheries (Cooke et al., 2016; Funge-Smith and Bennett, 2019), of freshwater aquaculture (Belton et al., 2020), and of seafood trade more generally (Belton and Bush, 2014).

Yet, the Chinese seafood market remains overall dominated by freshwater fish consumption (Chiu et al., 2013), and there are at least two significant reasons to gain a better understanding of the Chinese freshwater fish consumer market. Firstly, aquaculture is increasing rapidly across the globe, and in particular, freshwater aquaculture is responsible for an increasingly significant level of food consumption (Edwards et al., 2019). While freshwater fish do not tend to be as valuable as marine species per piece, the overall volume of the Chinese freshwater fish market makes it hugely economically significant, and many producers see China as a potential market to sell their products (e.g., Rabobank, 2012). Secondly, from an environmental sustainability perspective, the production and consumption of herbivorous fish such as carp and tilapia is seen as relatively less harmful than many higher-trophic level marine species (Little et al., 2016). Understanding how to promote the consumption of such relatively environmentally sustainably produced fish—and not just reduce the consumption of fish with negative environmental impacts, such as shark fin—is therefore a goal of environmental non-government organisations and policymakers (see e.g., China Blue, 2019).

National level statistics on aquatic product consumption in China do not take into account out-of-home consumption, nor do they describe down to species-level (Chiu et al., 2013). As such, most academic literature on Chinese freshwater fish consumption exists through scattered surveys (e.g., Chiu et al., 2013; Fabinyi et al., 2016; Xian, 2016), although there is also a very significant literature on freshwater fish production in China (e.g., Cao et al., 2015). This paper aims to address the gap in the literature on the Chinese freshwater fish market through a qualitative case study of the Chengdu freshwater fish market. As an exploratory study, the focus is on understanding key characteristics of this market including prices, common freshwater fish products and social contexts of consumption; and on key drivers of change. Findings on the characteristics and dynamics of the freshwater fish market in Chengdu then forms the basis for a wider discussion that compares these features to other, more well-studied aquatic product markets in China, and on the implications for policymakers.

Materials and Methods

Chinese consumer aquatic product preferences are highly diverse according to many factors, such as age, education, gender, wealth and region (e.g., Fabinyi et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Chengdu is a useful case study to examine freshwater fish consumption because, unlike the major coastal cities of China, its regional cuisine (Sichuan cuisine) includes a relatively large proportion of freshwater fish. It is considered to be a ‘second-tier’ city in China, which is undergoing processes of rapid economic and social change broadly similar to many other second-tier cities. While luxury seafood consumption and that of imported products is more commonly associated with first-tier cities (Wang and Somogyi, 2020), freshwater fish consumption, much of which is domestically produced, is more prevalent in inland, second-tier cities.

The research design broadly followed that of Fabinyi and Liu (2014) and Fabinyi et al. (2017) in that it did not directly interview consumers, but considered traders and restaurateurs as key informants on market characteristics and dynamics, and as such a qualitative approach was more appropriate. The goal of the interviews were to establish key characteristics of the freshwater fish market in Chengdu in terms of prices, commonly consumed species, and the social context of consumption; and key trends and drivers of change.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 6 restaurateurs, 2 farmers and 12 traders (from supermarkets, local wet markets and wholesale markets). Interviews were conducted together with a research assistant who helped with introducing the topic and its significance as well as asking a variety of questions and then facilitating the interview by interpreting answers if required. The interviews purposively targeted different types of restaurants and seafood traders; the goal was not to attain a random sample but to obtain ‘saturation’, a standard and well-established concept in qualitative research that refers to the process in data collection where each new interview brings little or no new information (Morse, 1995; Grady, 1998). The interviews were transcribed and translated into English, and data analysis involved manually coding and identifying emergent themes (Bernard, 2006). Informed consent was obtained for all interviews.

Results and Discussion

Commonly Consumed Freshwater Fish in Chengdu

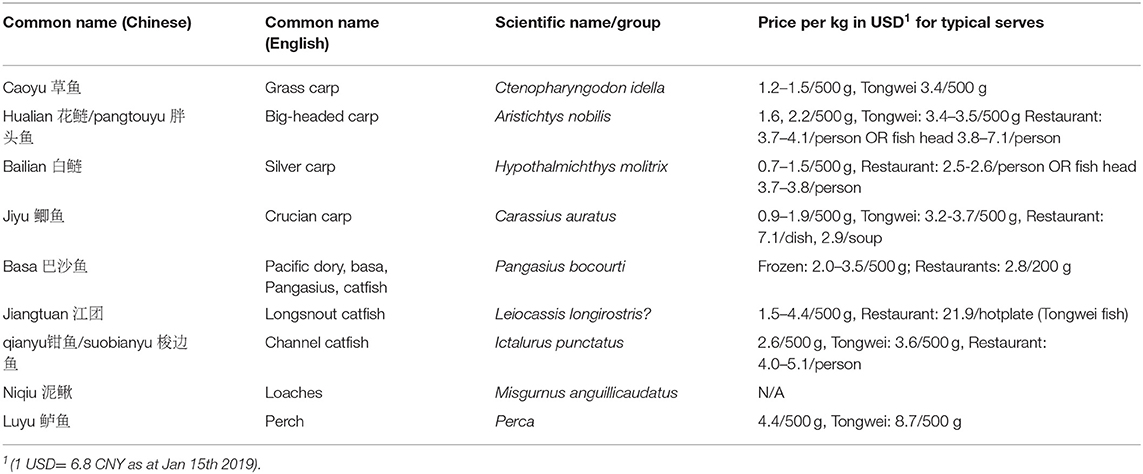

Table 1 shows the various kinds of freshwater fish commonly available for purchase at markets in Chengdu. The species that are most prevalent in wet markets, restaurants, and supermarkets include grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella, caoyu 草鱼), big-headed carp (Aristichtys nobilis, hualian 花鲢 or pangtouyu 胖头鱼), silver carp (Hypothalmichthys molitrix, bailian 白莲), crucian carp (Carassius auratus, jiyu 鲫鱼), longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris, jiangtuan 江团), channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus, qianyu 钳鱼 or suobianyu 梭边鱼), pangasius (pangasius spp., basa 巴沙鱼), and loaches (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus, niqiu 泥鳅).

All can be easily sourced live in Chengdu, with the exception of pangasius which was either: (1) sold frozen at wholesale markets and supermarkets or (2) served as part of a prepared meal in restaurants (Interview with Restauratuer 28 December 2018).

In general, there is a two-tiered pricing structure for the sale of live fish – those that are marketed under the Tongwei brand are sold at a premium in comparison to the exact same species of fish from other sources (Tongwei is a major seafood company in China with a large presence in Sichuan; see “Tongwei Group” section for a full description of the reasons behind these price differences). For example, the lowest priced Tongwei crucian carp was selling for $3.2 US/500 g in comparison to $0.9 US/500 g for the unbranded. The prices of grass carp ($3.4 versus $1.2 US/500 g), big-headed carp ($3.4 versus $1.6 US/500 g) and channel catfish ($3.6 versus $2.6 US/500 g) follow a similar pattern.

Many of these fish are consumed at home, for example big-headed carp is popular in Chengdu and locals might prepare it akin to cold-pot fish whereby a pot including delicate slices of fish, vegetables and tofu would be served in a Sichuanese broth accompanying plain steamed rice. The ‘cold-pot’ refers to the absence of a heat source on the dining table as the fish is served ready-to-eat, as opposed to ‘hot-pot’ whereby diners play an active role in cooking at the dining table. In restaurants, prices of freshwater fish depend on the serving style: (1) cold-pot fish is often shared between two or more people whereby diners choose one type of fish and are charged a specified amount per person—though the fish is typically served banquet style; (2) grilled fish and other Sichuan style fish dishes such as fish with pickled vegetables (suancaiyu 酸菜鱼) are generally priced per dish à la carte style from $5.8 US/dish. As an example, cold-pot silver carp is priced from $2.5 US/person but grilled Tongwei channel catfish is $20.4 US/plate. A further distinction in price is required for cold-pot silver carp fish head which was available at $3.7 US/person—many consider the fish head as a delicacy. The Tongwei longsnout catfish was the highest priced fish among selected casual restaurants in Chengdu at $21.9 US/hotplate (Interview with Waiter 28 December 2018). Grilled fish is popular among a wide range of clientele, especially for social settings. Premium fish such as perch (luyu, Perca) and Mandarin fish (guiyu, Siniperca chuatsi) are mainly sold to wealthier consumers, whereas “ordinary people eat silver carps and grass carps” (Interview with Vendor 31 December 2018).

Sourcing of Freshwater Fish in Chengdu

Freshwater fish in Chengdu is widely available through numerous outlets. Innumerable small-scale fish farms located within Sichuan or other nearby provinces such as Hubei underpin this supply chain by cultivating fish until they are of sufficient size and ready to be transported alive in specialised trucks to either: (1) wholesale markets such as Baijia wholesale market in Chengdu, or (2) supermarkets. Large supermarkets in particular tend to have a greater range of fish for sale (such as frozen pangasius), and at a higher price compared to local markets. Wholesale markets generally supply vendors from smaller neighbourhood wet markets, restaurants and some independent consumers. Such local wet markets also supply (sometimes by delivery) to restaurants and are more accessible to the public.

The largest wholesale fish market in Chengdu is the Baijia market on the outskirts of the city. Fish at the Baijia wholesale market tend to come from Meishan city, or Hubei and Jiangsu provinces (Interview with Vendor 20 January 2019). Another large fish market named Qingshiqiao exists closer to the heart of Chengdu, providing the general public greater accessibility to a range of seafood products sourced from different parts of China. There are also a great number of smaller local markets that are oriented towards serving their local neighbourhood. Pangasius is mostly sourced from Vietnam in frozen form and has enjoyed a rise in popularity recently. This product is mainly available in supermarkets and large wholesale markets because it requires cold chain storage.

Tongwei Group

Tongwei Group is a major Chinese conglomerate that has integrated production, distribution and sales channels for freshwater fish. It was mentioned by many as having a significant role to play in the production of freshwater fish. Its supply network depends mainly on two aquaculture locations—one in Hainan and the other in Sichuan. There is a separate Tongwei wholesale market in Chengdu named Sanlian (三 联) where Tongwei branding, colours and signage are predominant.

The brand name is seen to confer trust to customers about food safety. As one vendor at a smaller store claimed, “The company does not use chemicals or pesticides, so the fish is safe to eat, and quality is guaranteed” (Interview with Vendor 17 January 2019). The reputation and recognition of Tongwei products is further enhanced by its modern distribution channels—its fish are sold through online platforms including JD.com, China's largest online retailer. Furthermore, Tongwei is a supplier for various international supermarket chains including Ito Yokato and Carrefour.

Despite its reputation, there are some vendors who believe the price premium is not justified. For example, when one vendor was asked about differences between Tongwei fish and other fish, the response was “Actually, they are pretty much the same, but Tongwei is good at advertising and made itself a big brand” (Interview with Vendor 20 January 2019). However, the consensus concerning Tongwei is that it uses its technology to produce the best quality fish feed on the market, as one restaurateur puts it: “Good feed makes good fish” (Interview with Restauratuer 28 December 2018). Furthermore, one farmer of longsnout catfish suggested that the key to good fish is using good quality fish feed, and then mentioned they use Tongwei fish feed (Interview with Farmer 24 January 2019).

Food Quality and Food Safety

Food safety is an ongoing concern in China, including in the freshwater fish sector (Xu et al., 2012; Fabinyi et al., 2016), as one vendor explains: “About seven or eight years ago there was a rumour that some grass carp were fed with bad feed and their meat tasted strange” (Interview with Vendor 22 January 2019). Many interviewees perceived that regular inspections by higher authorities serve to prevent malpractices within the fish cultivation industry. For example, one vendor from a wholesale market mentioned that the market is inspected every three to four days by the market management so as to dissuade any malpractices relating to fish feed, whereas another was confident that there are no harmful substances in the fish feed owing to tighter inspections by government representatives (Interview with Vendor 22 January 2019). Freshwater fish were contrasted positively with pork, which had suffered from recent outbreaks of African swine fever in China:

“Fish won't catch any diseases, they are not like pigs or chickens, which are more susceptible to disease outbreaks, so customers feel safe to buy them” (Interview with Vendor 22 January 2019).

“People are cautious about eating pork this year because of the swine fever, so fish prices are much higher than in previous years” (Interview with Vendor 31 December 2018).

It is uncommon for vendors or restaurants in Chengdu to list the origins of fish that is sold, and transparency and traceability standards are low. For example, although consumers tend to have an aversion to the so called ‘eight-barbel catfish’, one vendor said that restaurants may serve this as channel catfish as she suggested that most customers aren't able to distinguish between these kinds of fish—especially once sliced and prepared (Interview with Vendor 14 January 2019).

Local Food Culture in Chengdu

Chengdu was formally declared by UNESCO to be a city of gastronomy in 2011 in recognition of the city's distinctive culinary culture. Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of Sichuanese cuisine is the use of Sichuan peppercorns and chillies, which are commonly combined and used across a wide range of dishes. Another aspect of Sichuanese food culture is the use of freshwater fish. Fish is served in various ways including hot-pot (huoguo 火锅), cold-pot fish (lengguoyu 冷锅鱼), grilled fish (kaoyu 烤鱼) and various braised fish dishes such as fish with pickled vegetables (suancaiyu 酸菜鱼). With hot-pot, the customer is in charge of cooking whereas the other dishes are prepared in the kitchen and are served ready to consume directly—often with plain steamed rice. Furthermore, the act of consuming these dishes is somewhat more experiential and social compared to other choices of meals such as a bowl of noodles which might be consumed individually. Hot-pot in particular is often used as a way to welcome guests to Chengdu and is often enjoyed by groups of people as a social occasion.

The kinds of fish that are used in hot-pot differ slightly, for example, loaches are well-suited for hot-pot due to their small size, and do not tend to be used in other fish preparations. However, crucian and grass carps are suited for skewering and grilling due to their body shape, whereas big-headed carp are generally used to prepare cold-pot fish as its meat is the tenderest out of the most commonly consumed freshwater fish in Chengdu (Interview with Vendor 22 January 2019). Fish head is commonly reserved and served separately as it tends to be more highly prized for perceived cultural and nutritional reasons. It therefore commands a higher price along the supply chain including at the local wet market and in restaurants. Fish maw is also considered a specialty, and this by-product of gutting live fish as requested by customers at a local wet market can be sold to other customers. The practice of keeping fish alive at markets and in restaurants highlights the importance of freshness in Chinese cuisine and was emphasised in multiple interviews.

Although taste is personal and subjective, certain attributes of freshwater fish are highly valued. The quantity and size of the bones, the perceived tenderness of the meat, the scales and the perceived cleanliness of the fish are all important factors. Fish fillets tend to be sliced thinly for dishes such as fish with pickled vegetables (suancaiyu 酸菜鱼) so as to “make flavour go into the fish more easily” (Interview with Restaurateur 31 December 2018). Sichuanese are also very discerning when it comes to matching particular types of fish with certain cooking techniques. A restaurateur explained that marine fish are usually steamed although the kinds of fish that are commonly consumed in Chengdu would be “not delicious and smelly” if steamed. He described how to offset the ‘fishy’ smell using other techniques such as slicing the fish thinly, washing the slices thoroughly and mixing the slices with garlic, ginger, salt and scallions (Interview with Restauratuer 31 December 2018). Furthermore, another pointed out how it might be a waste to use expensive fish for many Sichuanese dishes as the flavours can be seen to overpower the natural flavour of other more expensive fish (Interview with Restaurateur 18 January 2019). Although taste and flavour are held in high regard in Chengdu, the fact that locally consumed fish tend to be seen as good value for money also contributes to their popularity.

Fish is particularly popular during Lunar New Year celebrations (otherwise known as the Spring festival) as the word for ‘fish’ (yu 鱼) is a homophone for the word ‘riches’ (yu 余), which means many Chinese equate fish with prosperity and surplus. One restaurateur described that during the Lunar New Year: “We always buy good fish, expensive fish for this festival. We usually buy better fish during the Spring Festival. It's usually the big fish. Silver carp can weigh as much as 5kg and it tastes good” (Interview with Restauratuer 31 December 2018).

This suggests that even if the working class aren't able to celebrate special occasions with premium fish, they will still endeavour to purchase larger species of commonly consumed fish. With regards to doing business in this industry, most interviewees merely mentioned business was steady. However, one vendor elaborated that “retail sales are indeed not as good as before, we mainly deliver to restaurants now”, suggesting that the consumption of freshwater fish has shifted away from home prepared meals as more people enjoy the luxury of affording to dine-out (Interview with Vendor 22 January 2019). This upward mobility is reflected in the comments of another vendor: “Now we have to sell more (perch and Mandarin fish) than before, as our life is getting better and better (i.e. rapid economic development of China). We used to sell less perch and Mandarin fish” (Interview with Vendor 31 December 2018).

Conclusion

Changing consumer preferences for aquatic products are a crucial driver of outcomes in fish food system sustainability (Tlusty et al., 2019). While the literature on the Chinese market, the largest in the world, has been dominated by analyses of consumer preferences for marine products, farmed freshwater fish provide an increasingly important aspect of consumer diets (Belton et al., 2018), and have long been a significant component of aquatic product consumption in China. This paper has addressed this gap in this literature by focusing on the relatively neglected freshwater fish market in China, describing the characteristics and trends of the freshwater fish market in Chengdu. Further research is needed to address the regional and sampling limitations of this study through quantitative surveys of consumer preferences, value chain dynamics (e.g., Wang et al., 2019) and for studies of freshwater markets across broader or multiple regions of China.

Overall, the study found that the freshwater fish market in Chengdu has similar characteristics to Chinese aquatic product markets in first-tier cities, and to luxury, largely marine markets (Fabinyi and Liu, 2014; Fabinyi et al., 2017; Wang and Somogyi, 2018, 2020; Wang et al., 2018). Firstly, similar values inform consumer preferences for fish. In particular, perceptions about food safety, freshness, cost and local culinary traditions are all important influences over how and what freshwater fish are consumed. Secondly, while carps are still widely consumed by people at home, at restaurants and remain the most common type of fish, there are reports that eating out at restaurants is becoming more common as incomes rise (Zhou et al., 2014), and a growing demand for branded (e.g., Tongwei) and imported (e.g., pangasius) fish. In particular, the apparent rise in pangasius consumption mirrors national reports of trends of increased consumption (Craze, 2019; Harkell, 2019).

Taken together, the findings suggest that the Chinese freshwater fish market is not just a market for cheap, domestically produced products that are largely consumed at home, but dynamic in that it increasingly incorporates branded products, imported products, and eating out at restaurants. While domestically produced carps will continue to be important for the lower end of the Chinese freshwater fish market for the foreseeable future, the freshwater fish market is also changing towards increased out of home consumption, and consumption of imported products—trends usually associated with the luxury, largely marine market in first-tier cities (Wang and Somogyi, 2020). These findings suggest that strong opportunities exist to promote new freshwater species, brands and alternative product forms. For environmental NGOs and others seeking to promote the consumption of more environmentally sustainable seafood in China, this presents an opportunity to complement the negative campaigns against shark fin and other unsusutainably harvested marine products with a positive campaign focusing on more environmentally sustainable freshwater fish consumption. Overall, this paper provides further evidence for the ongoing significance of farmed freshwater fish products as a component of wider, changing trends in consumer aquatic product preferences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because a condition of the ethics protocol was that raw data would only be accessed by the researchers due to confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWljaGFlbC5mYWJpbnlpQHV0cy5lZHUuYXU=.

Ethics Statement

The research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of University of Technology Sydney (Human Ethics Approval Number ETH18-3075). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MF: research design. JF: data collection. JF and MF: data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council grant 'Governing the blue economy in maritime Asia-Pacific' DP180100965. The funder had no role in the design or implementation of the research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thankyou to Yi Guimei from Sichuan University for her support of the research, and to Han Han from China Blue and Dr. Wenbo Zhang from Shanghai Ocean University for helpful discussions on the topic of the paper. Thanks also to Qian Ren and Liu Jingya for their research assistance.

References

Belton, B., and Bush, S. R. (2014). Beyond net deficits: new priorities for an aquacultural geography. Geograph. J. 180, 3–14. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12035

Belton, B., Bush, S. R., and Little, D. C. (2018). Not just for the wealthy: rethinking farmed fish consumption in the Global South. Global Food Security 16, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.10.005

Belton, B., Little, D. C., Zhang, W., Edwards, P., Skladany, M., and Thilsted, S. H. (2020). Farming fish in the sea will not nourish the world. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19679-9

Béné, C., Barange, M., Subasinghe, R., Pinstrup-Andersen, P., Merino, G., Hemre, G. I., et al. (2015). Feeding 9 billion by 2050–Putting fish back on the menu. Food Security 7, 261–274. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0427-z

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

Bogard, J. R., Farmery, A. K., Little, D. C., Fulton, E. A., and Cook, M. (2019). Will fish be part of future healthy and sustainable diets?. Lancet Planetary Health 3, e159–e160. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30018-X

Cao, L., Naylor, R., Henriksson, P., Leadbitter, D., Metian, M., Troell, M., et al. (2015). China's aquaculture and the world's wild fisheries. Science 347, 133–135. doi: 10.1126/science.1260149

China Blue (2019). iFISH. http://www.chinabluesustainability.org/?page_id=2193andlang=en (accessed 20 Nov 2019)

Chiu, A., Li, L., Guo, S., Bai, J., Fedor, C., and Naylor, R. L. (2013). Feed and fish meal use in the production of carp and tilapia in China. Aquaculture 414–415, 127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.07.049

Cooke, S. J., Allison, E. H., Beard, T. D., Arlinghaus, R., Arthington, A. H., Bartley, D. M., et al. (2016). On the sustainability of inland fisheries: finding a future for the forgotten. Ambio 45, 753–764. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0787-4

Craze, M. (2019). UnderCurrent News. 17/5/2019. Vietnam sees a flourishing market for pangasius fillets in China. Available online at: https://www.undercurrentnews.com/2019/05/17/vietnam-sees-a-flourishing-market-for-pangasius-fillets-in-china/ (accessed August 8, 2019)

Edwards, P., Zhang, W., Belton, B., and Little, D. C. (2019). Misunderstandings, myths and mantras in aquaculture: its contribution to world food supplies has been systematically over reported. Mar. Policy 106:103547. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103547

Fabinyi, M., Barclay, K., and Eriksson, H. (2017). Chinese trader perceptions on sourcing and consumption of endangered seafood. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:181. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00181

Fabinyi, M., and Liu, N. (2014). Seafood consumption in Beijing restaurants: consumer perspectives and implications for sustainability. Conserv. Soc. 12, 218–228. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.138423

Fabinyi, M., Liu, N., Song, Q., and Li, R. (2016). Aquatic product consumption patterns and perceptions among the Chinese middle class. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 7, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2016.01.013

Funge-Smith, S., and Bennett, A. (2019). A fresh look at inland fisheries and their role in food security and livelihoods. Fish Fish. 20, 1176–1195. doi: 10.1111/faf.12403

Grady, M. P. (1998). Qualitative and Action Research: A Practitioner Handbook. Bloomington: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Harkell, L. (2019). UnderCurrent News. 12/4/2019. Chen Dan: Chinese pangasius will be ‘hot like crayfish'. Available online at: https://www.undercurrentnews.com/2019/04/12/chen-dan-chinese-farmed-pangasius-will-be-hot-like-crayfish/?utm_source=Undercurrent+News+Alertsandutm_campaign=ac8aaf7d16-Asia_Pacific_roundup_Apr_17_2019andutm_medium=emailandutm_term=0_feb55e2e23-ac8aaf7d16-92636765 (accessed August 8, 2019)

Little, D. C., Newton, R. W., and Beveridge, M. C. (2016). Aquaculture: a rapidly growing and significant source of sustainable food? Status, transitions and potential. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 75, 274–286. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000665

Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 5, 147–149. doi: 10.1177/104973239500500201

Purcell, S. W., Williamson, D. H., and Ngaluafe, P. (2018). Chinese market prices of beche-de-mer: implications for fisheries and aquaculture. Mar. Policy 91, 58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.005

Rabobank (2012). The Dragon's changing appetite: how China's evolving seafood industry and consumption are impacting global seafood markets. Available online at: http://transparentsea.co/images/c/c5/Rabobank_IN341_The_Dragons_Changing_Appetite_Nikolik_Chow_October2012.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2016).

Shea, K. H., and To, A. W. (2017). From boat to bowl: patterns and dynamics of shark fin trade in Hong Kong—implications for monitoring and management. Mar. Policy 81, 330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.04.016

Tlusty, M. F., Tyedmers, P., Bailey, M., Ziegler, F., Henriksson, P. J., Bén,é, C., et al. (2019). Reframing the sustainable seafood narrative. Glob. Environ. Change 59:101991. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101991

Villasante, S., Rodríguez-González, D., Antelo, M., Rivero-Rodríguez, S., de Santiago, J. A., and Macho, G. (2013). All fish for China? Ambio 42, 923–936. doi: 10.1007/s13280-013-0448-9

Wang, O., and Somogyi, S. (2018). Chinese consumers and shellfish: associations between perception, quality, attitude and consumption. Food Qual. Pref. 66, 52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.01.001

Wang, O., and Somogyi, S. (2020). Motives for luxury seafood consumption in first-tier cities in China. Food Qual. Pref. 79:103780. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103780

Wang, O., Somogyi, S., and Ablett, R. (2018). General image, perceptions and consumer segments of luxury seafood in China: a case study for lobster. Br. Food J. 120, 969–983. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2017-0379

Wang, O., Somogyi, S., and Charlebois, S. (2019). Mapping the value chain of imported shellfish in China. Mar. Policy 99, 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.10.024

Xian, Z. (2016). A Study of Carp Production and Consumption in Hubei Province of China. MSc Thesis, University of Stirling.

Xu, P., Zeng, Y., Fong, Q., Lone, T., and Liu, Y. (2012). Chinese consumers' willingness to pay for green-and eco-labeled seafood. Food Control 28, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.04.008

Zhai, F. Y., Du, S. F., Wang, Z. H., Zhang, J. G., Du, W. W., and Popkin, B. M. (2014). Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes. Rev. 15, 16–26. doi: 10.1111/obr.12124

Zheng, Q., Wang, H., and Lu, Y. (2018). Consumer purchase intentions for sustainable wild salmon in the Chinese market and implications for agribusiness decisions. Sustainability 10:1377. doi: 10.3390/su10051377

Keywords: seafood, China, consumption, Sichuan, freshwater fish, carp

Citation: Fang J and Fabinyi M (2021) Characteristics and Dynamics of the Freshwater Fish Market in Chengdu, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:638997. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.638997

Received: 10 January 2021; Accepted: 23 June 2021;

Published: 19 July 2021.

Edited by:

Barry A. Costa-Pierce, University of New England, United StatesReviewed by:

Ogmundur Knútsson, Directorate of Fisheries, IcelandOu Wang, University of Waikato, New Zealand

Copyright © 2021 Fang and Fabinyi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Fabinyi, bWljaGFlbC5mYWJpbnlpQHV0cy5lZHUuYXU=; orcid.org/0000-0001-5293-4081

Julian Fang

Julian Fang Michael Fabinyi

Michael Fabinyi