- 1Anthropology, School of Language Culture and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, United States

- 2Oxfam Novib, The Hague, Netherlands

- 3Centro de Estudios en Geografía Humana, El Colegio de Michoacán, La Piedad, Mexico

The growing recognition of food justice as an element of food studies inquiry has opened a productive vein that allows for analyzing the effects of oppression on traditional foods of Indigenous peoples. We provide a preliminary classification of food oppression by presenting several different types of foods from a number of cultures: (1) replaced and repressed foods; (2) disempowered and misrepresented foods; and (3) foods of oppression of the dispossessed. Our main argument is that these food types represent different faces of oppression and state power that, regardless of the inherent differences, have permeated diets and imaginaries in various spatial scales and, in doing so, have caused deprivation in local communities, despite being accepted in many cases as traditional food items in oppressed cultures. We conducted a systematic literature review in Scopus focusing on the traditional foods of Indigenous people and elements of oppression and revitalization. The results of our review are discussed in light of what we identify as aspects of culinary oppression. We conclude our paper by sketching the plausible first steps for redemptory solutions based on Indigenous food work aimed at reclaiming basic revalorization and revitalization.

Introduction

Burnett and Figley propose the concept of historical oppression that includes the “cumulative, massive, and chronic trauma imposed on a group across generations and within the life course” (Burnette and Figley, 2017:38). They note that historic trauma includes land dispossession, warfare, and forced assimilations. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the General Assembly on 13 September 2007, with 144 countries voting in support, four voting against and 11 abstaining. As of 2020, the four countries that voted against have now voted to support the Declaration (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples, 2020). It is not surprising that in 2007 the countries not supporting the UNDRP were Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States- all four being colonial settler countries with disenfranchised Indigenous inhabitants. Settler colonial societies by their very structure were established to have permanent white settlers (United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples, 2020). These colonial societies engaged in confiscating Indigenous lands and privatizing them as carved up allocations to settlers. While this type of oppression is rooted in colonial history, its effects are ongoing and include continued impoverishment and marginalization, as well as everyday injustices maintained by power dynamics that tend to impose and perpetuate inequality.

Indigenous peoples have often lost vital and rich food territories, been physically relocated to marginal lands, and had their food ways unacknowledged or denigrated (Schoney, 2007; Turner and Turner, 2008). This loss affects multiple aspects of cultural heritage that interface the territorial and material aspects of food. UNESCO (2003) identifies intangible cultural heritage as including the passing of knowledge from generation to generation, social practices, rituals, and festive events as well as knowledge and practices concerning both nature and the universe and knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts. All of these elements are aspects of cultural food ways and central to a people's overall culture. Peoples relocated from their homelands have little opportunity to maintain their food knowledge and practices. In the USA, results of land and food impoverishment are to be seen in the on-going barriers to accessing food, health disparities, and endemic poverty (Pindus and Hafford, 2019; Freeman, 2020). Other Indigenous and traditional peoples who remain in proximity to their traditional food environments can experience a decrease in use of traditional foods as a more gradual process (Kuhnlein and Receveur, 1996). Hartwig, Jackson, and Osborne describe the contemporary disenfranchisement of Australian Aboriginal peoples resulting from the historic colonial separation of land and water rights. They state: “Changes in Aboriginal water holdings between 2009 and 2018 are indicative of a new wave of dispossession. Almost one fifth of Aboriginal water holdings by volume were lost over 2009–18” (Hartwig et al., 2020:1). Neo-colonial dispossessions include land grabs in Latin America, Africa, and Asia (Lyons and Westoby, 2014; Ashukem, 2020). While land grabbing has roots in colonialism, the practice is now constructed by state actors and corporations seeking land primarily for profitable agricultural or forestry enterprises, namely for products and food to export (Carmody and Taylor, 2016; Charin and Hidayat, 2019; Nyenyezi Bisoka and Ansoms, 2020).

Oppression affects traditional foods and the knowledge and traditional practices surrounding food, with subsequent impacts on local diets and health from various perspectives including socio-historical contexts of culinary oppression. What people eat is linked to culture, environment, economy, and political power (McMichael, 2012). Select foods currently consumed are historically in intimate alignment to oppression, exploitation, and disenfranchisement of Indigenous and traditional peoples. These foods are often married to hardship but become significantly incorporated into the core diet and viewed as culturally “traditional foods” (Mihesuah, 2016). This use of the foods of oppression shows agency and a creativity that has facilitated survival with varying dietary outcomes (Vantrease, 2013; Batal et al., 2018; Tennant, 2020). In this paper, we examine these food traditions from various perspectives by conducting a systematic literature search using Scopus focused on the traditional foods of Indigenous people. In the next section, the results of our search are discussed in light of what we identify as aspects of culinary oppression.

Foods of Oppression, State of the Art

Scopus Search Methodology

We conducted a two-component systematic literature review using Scopus. The review used both Scopus indexed documents and secondary documents (Scopus, 2020) to include a broader coverage. We recognize that a limitation of this set of publications is that it might not necessarily capture most community-led efforts taking place. Future in-depth studies could include grey literature and other databases in the search.

All documents referring to traditional food of Indigenous peoples in title, abstract, and keywords, and published to 31 December 2019, were included in our database for further analysis. For that, the Booleans AND, which ensures the presence of both terms, and OR, which allows the presence of either term (or both), were used using the keyword combination (“traditional food*” AND indigenous*) OR “indigenous people* food” OR “indigenous* food” in the search. This yielded 670 publications indexed by Scopus, and 486 secondary documents (search one).

The search for publications that encompassed aspects of oppression was conducted based on the inclusion of terms in title, abstract and keywords related to replaced or repressed foods, disempowered or misrepresented foods, stigmatized foods, foods and status, foods of the dispossessed, and oppression. Regarding revitalization, articles that included aspects of both revitalization and revalorization were included (search two).

Scopus Search Results

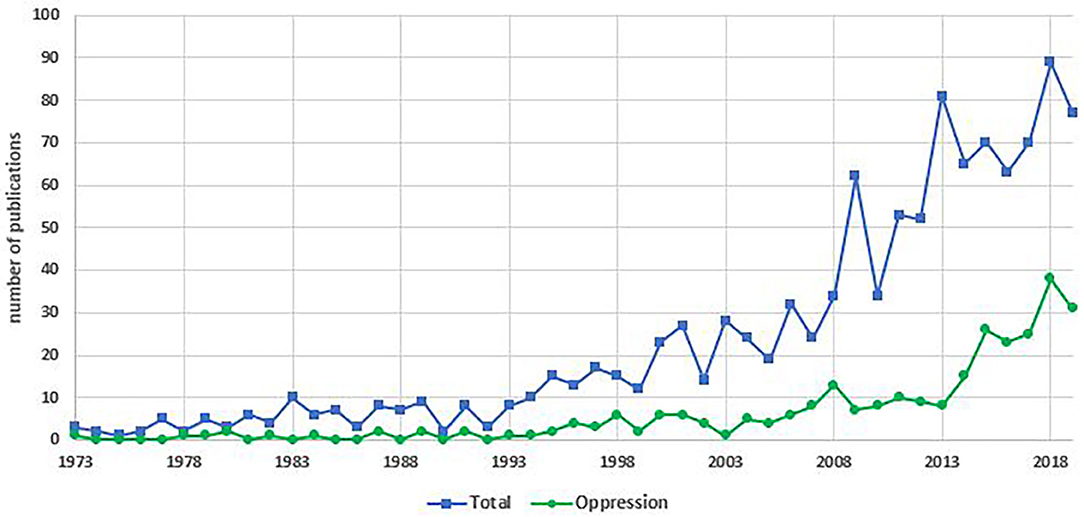

A total of 1,156 publications on traditional foods of Indigenous peoples have been published (search one). The first one dates back to 1915. The number of documents remained below 20 until 2000, when the number of publications started to exponentially increase, reaching a maximum of 89 in 2018 (Figure 1). Only 25% of these documents included aspects of oppression (search two), although the first paper on oppression was published in 1973.

Figure 1. Chronological trends comparing the total number of publications on traditional foods of Indigenous peoples, and how many of these include aspects of oppression. The chart starts in 1973, when the documents on Indigenous peoples' food started to be published in consecutive years.

The most prominent aspect associated with oppression found in the literature was status (261 publications). The term status, however, fails to fully grasp wider structural and historical issues of oppression for Indigenous populations. Terms related to food replacement, dispossession and oppression were included in few documents (26, 10, and eight publications, respectively); whereas issues of repression, disempowerment, misrepresentation, and stigma were largely absent in the literature (i.e., with one document or none). Only five articles referred to culinary colonialism. These results show that no common front has yet to emerge on foods of oppression for Indigenous peoples.

The revitalization or revalorization of Indigenous foods was mostly overlooked in the literature, with only 29 publications (all except one use the term revitalization). This could be partially explained by the fact that this topic is very recent, with the first document published in 2006. This finding might hypothetically be related to larger contextual factors, i.e., the marginalization of Indigenous voices or low number of Indigenous researchers, which could be a focus of future research. The documents on revitalization did not focus on gastronomy, cuisine or culinary (only one or three documents each). Likewise, there were no publications on revitalization that focused on the role of chefs. Furthermore, only two publications in Scopus are focused on Indigenous chefs. These findings suggest there is no common approach in the literature on the ways Indigenous food can be revitalized or revalorized in the context of oppression.

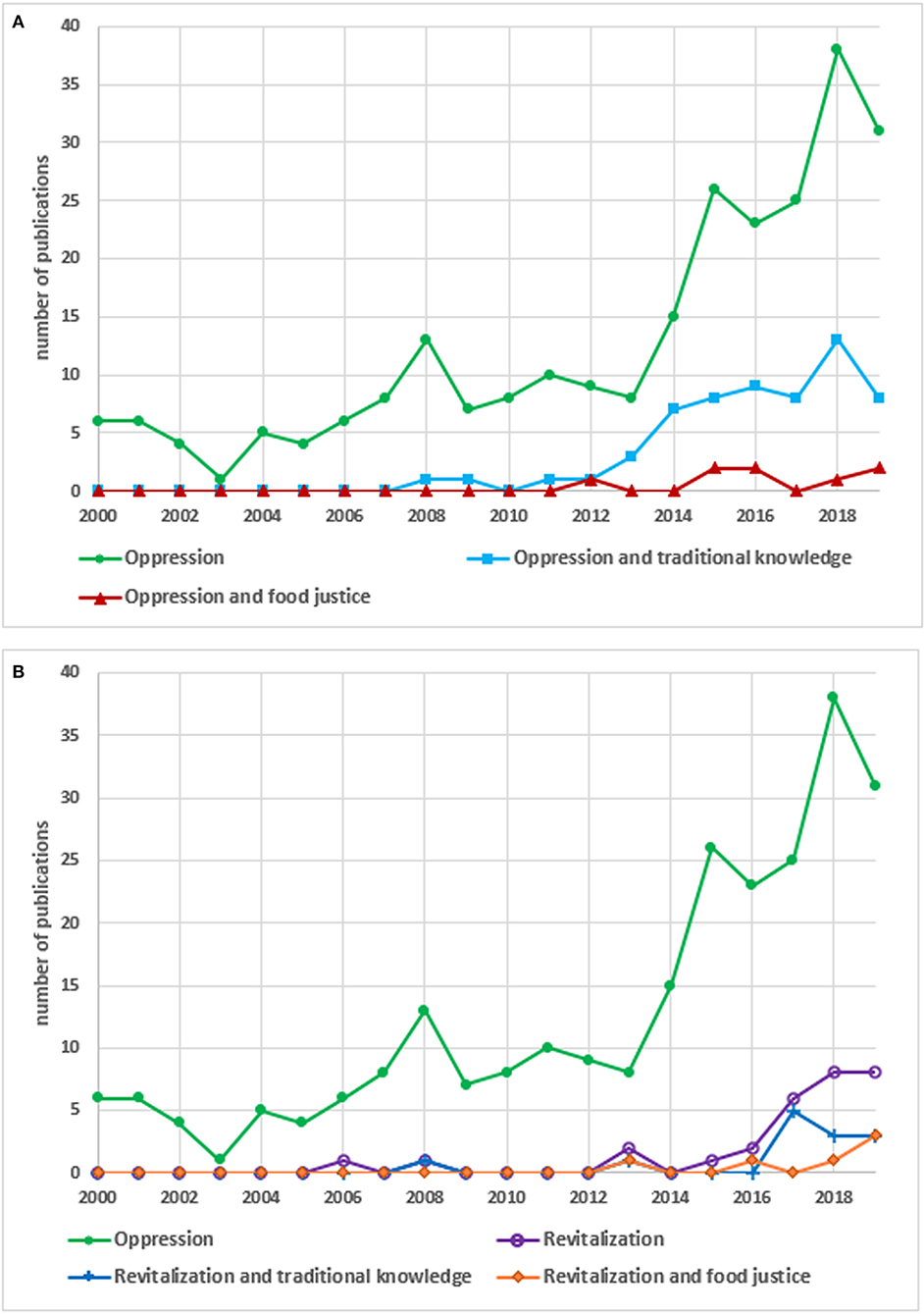

Traditional knowledge was only partly addressed by the literature. Only 22 percent of the documents addressing oppression include traditional knowledge (Figure 2A). The first one dates back to 1993, and only during the last decade did articles appear annually. Forty-five percent of the papers on revitalization include traditional knowledge, with not more than five documents published per year (Figure 2B). These results are surprising, since it has been recognized that oppression is associated with the loss of traditional knowledge, and revitalization is a pathway to regain or reclaim this knowledge.

Figure 2. This figure presents a close-up of the chronological trends of publications on Indigenous peoples' food that include aspects of oppression or revitalization, in relation to traditional knowledge and food justice. (A) Focuses on publications on oppression, while (B) highlights publications on revitalization. The charts start in 2000.

Only one percent of the publications on traditional foods of Indigenous peoples include food justice. While food sovereignty is a more popular concept, it was only included in nine percent of the documents. Food justice was only included in eight publications addressing oppression, and in six documents on revitalization of Indigenous foods (some also focusing on food sovereignty).

Foods of Oppression—an Initial Classification

The incorporation of political topics such as oppression with research on traditional knowledge and Indigenous foods has spanned nearly 50 years. However, the number of papers (averaging 6.2 papers per year) analyzing the convergence of gastronomic and political imaginaries remains relatively low for many topics, including those that are the main focus of our paper and in which oppression, Indigenous peoples, foods, and traditional knowledge intermingle. Imaginaries are those social values, institutions, laws, and symbols which enable common practices, building a sense of legitimacy (Taylor, 2007). Gastronomic imaginaries define what food is and how it should be eaten (see Martinez de Albeni, 2015) while political imaginaries highlight who can or cannot eat it.

We have identified three basic types of foods from a number of cultures that fall into the meta-category of foods of oppression. These types are: (1) replaced and repressed foods (2) disempowered and misrepresented foods, and (3) foods of oppression of the dispossessed.

Replaced and Repressed Foods

To fully understand the meaning of R&R foods it is necessary to link their use to the notions of social apartheid embedded in societal fascism (De Souza Santos, 1998) and in which cities and traditions are classified either as savage or civilized. In territories that have suffered settler colonialisms, as the dominant social groups acquire a growing power over life of the oppressed social groups, the gastronomic practices of the latter are supplanted with colonial foods. This includes introduced substitutes for traditional foods the settler culture deems uncivilized. Numerous examples of R&R foods can be found throughout the colonial history of the Americas, such is the case for the consumption of insects (Katz, 1996), barbecued deer (Vernot, 2018), or native sweets and sweeteners (Wall et al., 2020).

Disempowered and Misrepresented Foods

D&M are those foods that have classist denigration and are now considered (a) inferior in quality and/or nutritional content, (b) filthy, or (c) viewed as food of empoverished people in society regardless of their market value and wide geographic cultivation and yields. Quelites are, perhaps the most salient group of D&M foods because of their ample distribution throughout Mesoamerica (Vizcarra, 2000). Quelite is a generic name for some 500 plants that can be eaten either raw or cooked (Bye and Linares, 2000). Many of these plants, growing within cornfields (Linares and Bye, 2017), are considered to be nothing but weeds. Quelites are considered food for the poor (Katz, 2009), the colonized, and the slaves (De Shield, 2015) despite their nutritional value (Linares et al., 2019). Therefore, quelites, and many other constituents of the Mesoamerican diet (De Walt, 1983) were gradually replaced by processed wheat flour and animal fat (Vizcarra, 2000). The displacement of R&R and D&M foods has severe long-term consequences. For example, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Mexico was suffering a public health crisis triggered by diet-related illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (Denham and Gladstone, 2020). Acting as comorbidity factors, these illnesses placed Mexico among the 10 countries with most COVID-19 related deaths (Kánter Coronel, 2020).

Foods of Oppression of the Dispossessed

FOoDs are offered to the oppressed and conquered. Normally their consumption marks a distance between colonized and colonizer. These are food items that push the colonized closer to civilization, but still serve as a low status marker. The insides of cows and other mammals are common, such as mondongo (Sarmiento Ramírez, 2008); a kind of stew, usually made with offal (normally the cow stomach), popular especially in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. Perhaps the more iconic of these FOoDs is bannock also known as frybread in North America (Cyr and Slater, 2016). While considered by many as traditional Indigenous fare, their origin was in government commodity surplus handouts of flour and lard to Indigenous populations displaced and distanced from their food sources (Mihesuah, 2003, 2016, 2020). The term “comod bods” means the effect of eating these foods becomes visible on the body. The term “comod bod” exemplifies the well-known health impact of food aid and lack of traditional foods in the high occurrence of obesity and diabetes (Blevins, 2008; Vantrease, 2013; Mihesuah, 2016; DeBruyn et al., 2020). A study by Chino et al. (2009) illustrate the patterns of contemporary commodity food use showing regional variation and overall association between multigenerational commodity food consumers and contemporary preferences for canned meat, canned vegetables, and fruit and other commodity based foods.

Revitalization and Revalorization

There are a growing number of prominent Indigenous activist food scholars (Coté, 2016; LaDuke, 2019, Mihesuah, 2003, 2016, 2020). With only two publications in Scopus focused on Indigenous chefs, the growth of Indigenous chefs and their visibility and cultural influence is an area that needs further scholarly attention. Sean Sherman, Oglala Lakota chef and author of The Sioux Chefs' Indigenous Kitchen (Sherman and Dooley, 2017), won the 2018 James Beard Award for the Best American Cookbook. Chef Sherman cooks no frybread and does not use dairy, sugar or domestic beef or pork. In recent years, television productions have increasingly featured North American Indigenous chefs. Rich Francis of the Tetlit Gwich'in and Tuscarora Nations is the first Indigenous chef featured on Top Chef Canada (Indian Country Today, 2014). Chef Francis is an advocate for protecting Indigenous food practices in Ontario and challenges government regulations restricting hunting of wild game that have been central to tribal food ways. Francis appeared in the documentary series Red Chef Revival, which follows three chefs traveling to Indigenous communities in Canada to profile pre-colonial food systems (Kaur et al., 2019). Additional examples of television productions featuring Indigenous chefs include Alter-NATIVE: Kitchen (Luther, 2019) which highlights three Indigenous North American chefs who are creating a new diet of traditionally inspired cuisine, and programming produced by the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network of Canada.

Grey and Newman (2018) caution against contemporary culinary colonialism. They argue that there must be a right to hold Indigenous gastronomic capital back from the market. Gastronomic multiculturalism can be a threat to Indigenous food sovereignty. They note that diet under settler colonialism was one of assimilation but caution against the growth of appropriation that can now follow from non-indigenous chefs where “Indigenous cuisines are thus gentrified, reoriented toward the demographic that originally sought their eradication” (Grey and Newman, 2018:719). The visibility of Indigenous chefs and the work they do in and for Indigenous communities on the ground and digitally are important aspects of revalorization and revitalization. They embody acts of resistance as well, acting as political advocates for the Indigenous right to food sources, territory and culture as well as sustainable provisioning (Judkis, 2017; CBC News, 2018; Pereira et al., 2019).

The revitalization or revalorization of traditional foods is triggered by communities themselves, by outsiders, or both. Tribal educational initiatives have been largely successful in raising awareness and sharing knowledge and skills within Indigenous communities surrounding traditional foods that are central to cultural identity and good nutrition. For example, tribal schools and colleges in North America like the Northwest Indian College (2014) offer classes on cooking traditional foods for Indigenous people throughout Washington state as well as Indigenous professional culinary courses that can help fulfill career aspirations of college students. The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA) (2014) provides an example of the reach of the internet to provide a place to network and share the renewal of indigenous food, culture and resilience. Adult educational programs also prove to be successful on an international level. For example, the Farmer Field Schools on Nutrition and Local Food Plants (Sowing Diversity = Harvesting Security program www.SDHSprogram.org), encourage Indigenous farmers to identify the main bottlenecks that prevent the consumption of local biodiversity and conduct activities to counter them. During cooking demonstrations farmers regain their knowledge of old recipes with the collaboration of the female cooks in the community, or by inviting chefs to experiment and illustrate new ways of cooking traditional foods.

Discussion

We have identified colonialism as a mechanism for eroding local food systems. This has also been noted as a three-stage progression that concludes by misappropriating local foods (Grey and Patel, 2015). So far, we have clearly established boundaries for three types in which sorts of foods have oppressed native and formerly enslaved peoples.

Currently, many of these food items have resurfaced as important elements of a multicultural and globalized cuisine that seeks to bridge cultures through a banal fashion of cosmopolitanism (see Harvey, 2000) that keeps such foods and cultures as captives of culinary colonialism. To get out of this conundrum, it is important to give back the food to its fully acknowledged legitimate owners as has begun to happen if we look at the growth of Indigenous chefs and activist food scholars. Our Scopus search results, however, indicate that more scholarship on revalorization and revitalization is needed.

Future attention to neoliberal arenas of cosmopolitanism with the growth of interest in Indigenous foods deserve close attention. Warnings already made through historic reflection and contemporary concerns remind us that the politics of food go beyond eating and have to do with connecting power, land use, and supply chains. While some of the problems associated with all of these realms cannot be immediately solved, we are convinced that by identifying some of the existing types of culinary oppression and state of the art in publications from Scopus this paper offers a foundation from which new analytical points of view can contribute to the overarching debate in food justice and Indigenous culinary freedom.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions generated for the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ashukem, J. C. N. (2020). The SDGs and the bio-economy: fostering land-grabbing in Africa. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 47, 275–290. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2019.1687086

Batal, M., Johnson-Down, L., Moubarac, J. C., Ing, A., Fediuk, K., Sadik, T., et al. (2018). Quantifying associations of the dietary share of ultra-processed foods with overall diet quality in first nations peoples in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario. Public Health Nutr. 21, 103–113. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001677

Blevins, W. (2008). Dictionary of the American West. College Station, TX: Texas AandM University Press.

Burnette, C. E., and Figley, C. R. (2017). Historical oppression, resilience, and transcendence: can a holistic framework help explain violence experienced by indigenous people? Soc. Work 62, 37–44. doi: 10.1093/sw/sww065

Bye, R., and Linares, E. (2000). Los quelites, plantas comestibles de México: una reflexión sobre intercambio cultural. Biodiversitas 31, 11–14.

Carmody, P., and Taylor, D. (2016). Globalization, land grabbing, and the present-day colonial state in Uganda: ecolonization and its impacts. J. Environ. Dev. 25, 100–126. doi: 10.1177/1070496515622017

CBC News (2018). “Its just history repeating itself:” Indigenous chef says he'll go to court to serve country food. CBC News, Available online at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/chef-country-food-1.4798181 (accessed January 31, 2021).

Charin, R. O. P., and Hidayat, A. (2019). The efforts of talang mamak indigenous people to maintain their existence in customary forest resources battle. Society 7, 21–36. doi: 10.33019/society.v7i1.78

Chino, M., Haff, D. R., and Dodge Francis, C. (2009). Patterns of commodity food use among American Indians. Pimatisiwin J. Aborig. Indig. Commun. Health 7, 279–289.

Coté, C. (2016). “Indigenizing” food sovereignty. Revitalizing Indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities 5:57. doi: 10.3390/h5030057

Cyr, M., and Slater, J. (2016). “Got Bannock? Traditional Indigenous bread in Winnipeg's North End,” in Indigenous Perspectives on Education for Well-Being in Canada, eds. F. Deer and T. Falkenberg (Winnipeg, MB: Education for Sustainable for well-being Press), 59–73. Available online at: https://www.eswb-press.org/uploads/1/2/8/9/12899389/indigeneous_perspectives_2018.pdf (accessed December 24, 2020).

De Shield, C. L. (2015). The cosmopolitan amaranth: a postcolonial ecology. Postcolon. Text 10, 1–22.

De Souza Santos, B. S. (1998). Os fascismos sociais. Folha de S. Paulo, 6–7. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/opiniao/fz06099808.htm (accessed December 21, 2020).

De Walt, K. M. (1983). Nutritional Strategies and Agricultural Change in a Mexican Community. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

DeBruyn, L., Fullerton, L., Satterfield, D., and Frank, M. (2020). Peer reviewed: integrating culture and history to promote health and help prevent Type 2 diabetes in American Indian/Alaska Native communities: traditional foods have become a way to talk about health. Prev. Chronic Dis. 17:E12. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190213

Denham, D., and Gladstone, F. (2020). Making sense of food system transformation in Mexico. Geoforum. 115, 67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.024

Grey, S., and Newman, L. (2018). Beyond culinary colonialism: indigenous food sovereignty, liberal multiculturalism, and the control of gastronomic capital. Agric. Hum. Values 35, 717–730. doi: 10.1007/s10460-018-9868-2

Grey, S., and Patel, R. (2015). Food sovereignty as decolonization: some contributions from Indigenous movements to food system and development politics. Agric. Hum. Values 32, 431–444. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9548-9

Hartwig, L. D., Jackson, S., and Osborne, N. (2020). Trends in Aboriginal water ownership in New South Wales, Australia: the continuities between colonial and neoliberal forms of dispossession. Land Use Policy 99:104869. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104869

Harvey, D. (2000). Cosmopolitanism and the banality of geographical evils. Public Cult. 12, 529–564. doi: 10.1215/08992363-12-2-529

Indian Country Today (2014, May 7). Native chef Rich Francis makes final of ‘Top Chef Canada”. Indian Country Today. Available online at: https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/native-chef-rich-francis-makes-final-of-top-chef-canadac99RoTn0GUWASb1oBY2ptw (accessed December 27, 2020).

Judkis, M. (2017, November 22). This is not a trend: Native American chefs resist the “Columbusing” of Indigenous foods. Washington Post.

Kánter Coronel, I. (2020). Muertes por Covid-19 en México. Available online at: http://www.bibliodigitalibd.senado.gob.mx/handle/123456789/4927 (accessed December 21, 2020).

Katz, E. (1996). “Emergency foods of the Mixtec highlands (Mexico),” in Ethnobiology in Human Welfare, ed S. K. Jain (Lucknow: Deep Publications), 54–61.

Katz, E. (2009). Alimentação indígena na América Latina: comida invisível, comida de pobres ou patrimônio culinário? Espaço Am. 3, 25–41. doi: 10.22456/1982-6524.8319

Kaur, J., Desai, P, and Mah, R. (Producers). (2019). The Red Chef Revival [Documentary television series]. Lebanon: The Black Rino Production Company.

Kuhnlein, H. V., and Receveur, O. (1996). Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annual Rev. Nutr. 16, 417–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.002221

LaDuke, W. (2019). “Foreword” in Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States: Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments, and Regaining Health, eds D. A. Mihesuah and E. Hoover (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), XIII–XVI.

Linares, E., and Bye, R. (2017). Especies vegetales de uso tradicional subvaloradas y subutilizadas de las milpas de México. Revista Digital Universitaria 16. Available online at: http://www.revista.unam.mx/ojs/index.php/rdu/article/view/545 (accessed December 21, 2020).

Linares, E., Bye, R., Nava, N. O., Valdez, A. E. A., and Mariscal, A. G. (2019). “Los quelites del Tianguis de Ozumba (Estado de México, México). Su importancia y formas de consumo en la region,” in Experiencias de trabajo de la Red SIAL México con productores agropecuarios, ed R. M. Larroa-Torres (Ciudad de México: Red de Sistemas Agroalimentarios Localizados). Available online at: http://ru.iiec.unam.mx/4986/1/Experiencias_de_trabajo_SIAL.pdf#page=80 (accessed December 20, 2020).

Luther, B. (Director/Producer). (2019). Alter-Native: kitchen [Documentary film]. United States: World of Wonder Productions Inc.

Lyons, K., and Westoby, P. (2014). Carbon colonialism and the new land grab: plantation forestry in Uganda and its livelihood impacts. J. Rural Stud. 36, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.06.002

Martinez de Albeni, I. (2015). The candy project: the re-enchantment of candy in a liquid world. Essachess J. Commun. Stud. 8:16.

McMichael, P. (2012). The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 39, 681–701. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.661369

Mihesuah, D. (2016). Indigenous health initiatives, frybread, and the marketing of nontraditional “traditional” American Indian foods. Native Am. Indig. Stud. 3, 45–69. doi: 10.5749/natiindistudj.3.2.0045

Mihesuah, D. A. (2003). Decolonizing our diets by recovering our ancestors' gardens. Am. Indian Q. 27, 807–839. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2004.0084

Mihesuah, D. A. (2020). Recovering Our Ancestors' Gardens: Indigenous Recipes and Guide to Diet and Fitness. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Northwest Indian College. (2014) Available online at: https://www.nwic.edu/?s=food (acessed Jauary 31, 2021).

Nyenyezi Bisoka, A., and Ansoms, A. (2020). State and local authorities in land grabbing in Rwanda: governmentality and capitalist accumulation. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 41, 243–259. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2019.1629884

Pereira, L. M., Calderón-Contreras, R., Norström, A. V., Espinosa, D., Willis, J., Guerrero Lara, L., et al. (2019). Chefs as change-makers from the kitchen: indigenous knowledge and traditional food as sustainability innovations. Glob. Sustain. 2:E16. doi: 10.1017/S2059479819000139

Pindus, N., and Hafford, C. (2019). Food security and access to healthy foods in Indian country: Learning from the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. J. Public Affairs 19:e1876. doi: 10.1002/pa.1876

Sarmiento Ramírez, I. (2008). Del “funche” al “ajiaco”: la dieta que los amos imponen a los esclavos africanos en Cuba y la asimilación que éstos hacen de la cocina criolla. An. Museo Am. 16, 127–154.

Schoney, R. (2007). An economic study of loss of use of indian lands: a case study of Saskathchewan, Canada. J. ASFMRA 2000, 118–127. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.190683

Scopus (2020). Scopus: Access and Use Support Center. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V. Available online at: https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/11239/supporthub/scopus/ (accessed December 15, 2020).

Sherman, S., and Dooley, B. (2017). The Sioux Chef's Indigenous Kitchen. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Tennant, Z. (2020). Does Bannock Have a Place in Indigenous Cuisine? The Walrus. Available online at: https://thewalrus.ca/breaking-bread/#:~:text=Bannock%20is%20certainly%20part%20of,it's%20not%20the%20main%20dish (accessed January 31, 2021).

The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA). (2014) Available online at: https://nativefoodalliance.org/ (accessed January 31 2021).

Turner, N. J., and Turner, K. L. (2008). “Where our women used to get the food”: cumulative effects and loss of ethnobotanical knowledge and practice; case study from coastal British Columbia. Botany 86, 103–115. doi: 10.1139/B07-020

UNESCO (2003). Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed January 31, 2021).

United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples (2020). Adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: 13 Years Later. Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/news/2020/09/undrip13/ (accessed December 9, 2020).

Vantrease, D. (2013). Commod bods and frybread power: government food aid in American Indian culture. J. Am. Folkl. 126, 55–69. doi: 10.5406/jamerfolk.126.499.0055

Vernot, D. (2018). Changes in the social and food practices of indigenous people in the New Kingdom of Granada (Colombia): through artifacts. J. Ethn. Foods 5, 177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2018.08.001

Vizcarra, I. (2000). “El taco mazahua, la comida de la resistencia y de la identidad,” in Annual Meetings of the Latin American Studies Association (Miami, FL). 16–18. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ivonne_Bordi/publication/267802684_El_taco_mazahua_la_comida_de_la_resistencia_y_la_identidad_por/links/553428130cf27acb0def9030.pdf (accessed December 20, 2020).

Keywords: chefs, colonization, Indigenous, Indigenous people, revitalization, traditional

Citation: Price LL, Cruz-Garcia GS and Narchi NE (2021) Foods of Oppression. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:646907. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.646907

Received: 28 December 2020; Accepted: 12 February 2021;

Published: 17 March 2021.

Edited by:

Ina Vandebroek, New York Botanical Garden, United StatesReviewed by:

Tania Eulalia Martinez-Cruz, University of Greenwich, United KingdomLeigh Joseph, University of Victoria, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Price, Cruz-Garcia and Narchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa L. Price, bGlzYXByaWNlMTgxQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lisa L. Price

Lisa L. Price Gisella S. Cruz-Garcia

Gisella S. Cruz-Garcia Nemer E. Narchi

Nemer E. Narchi