- 1Section of Organic Food Quality, Faculty of Organic Agricultural Sciences, University of Kassel, Witzenhausen, Germany

- 2Policy Department, IFOAM Organics Europe, Brussels, Belgium

The necessity and urgency of the food systems transformation is no longer questionable, and the transformation pathways are inevitably reappearing as a subject of academic and public debate. In search of sustainable food production strategies as part of a broader transformation, organic food systems are called for as one of the solutions to achieve environmentally friendly and just food systems. In this context, the role of biodistricts has been recently emphasized at the EU level. The authors of the manuscript argue that biodistricts, aside from acting as a tool to help achieve the EU target of increasing the share of organically farmed land, are also capable of revitalizing rural territories and communities, which are currently threatened with rural exodus. Semi-structured interviews and the focus group with key actors of the biodistrict Cilento revealed a multitude of territory- and community related outcomes, which demonstrate that organic districts are capable of rendering rural territories to attractive multifunctional spaces with a tight-knit community.

1. Introduction

The food system (FS) is being increasingly seen as an essential component of humanity’s transformation toward a more sustainable future in order to align human activities with the planetary boundaries (Rockström et al., 2020). Indeed, being one of the main contributors to the major environmental problems including GHG emissions, ecosystems pollution, loss of habitats and biodiversity loss, the FS offers a tremendous potential to tackle these environmental externalities (Rockström et al., 2020; WWF, 2020). Against this background, sustainable food production practices are being called for to improve the FS performance and help humanity reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Caron et al., 2018; Willett et al., 2019). Organic FSs are being increasingly acknowledged as one of such sustainable solutions, which is why the Farm to Fork Strategy of the European Commission sets the goal of minimum 25% of agricultural land under organic farming in the EU by 2030 as part of its sustainable food production strategies (EU, 2020). One concrete tool for supporting the conversion to organic farming and encouraging short organic supply chains proposed in the Action Plan for the Development of Organic Production for 2021–2027 is biodistricts (Caprile and McEldowney, 2021). Biodistricts (or organic districts, organic regions or eco-regions) represent an innovative integrated territorial approach based on local production systems with prevalent organic farming practices and centered around the four principles of organic agriculture, while bringing together environmental, socio-cultural and economic elements (Stotten et al., 2017; Guareschi et al., 2020; Stotten and Froning, 2023). These initiatives are characterized by multi-level governance, which can be conceived of as “governance space placed between the farm and the territory” (Pugliese et al., 2015; Passaro and Randelli, 2022: 1219).

This manuscript aims to investigate the contribution of organic districts to the revitalization of rural territories and communities, taking the biodistrict Cilento as an example. The authors argue that not only can biodistricts be seen as a viable tool for promoting organic FSs and sustainable production methods, but they can also serve as an instrument for reviving rural territories and communities suffering from rural exodus. The manuscript begins with defining and describing biodistricts and proceeds with presenting the case study of the present research – the biodistrict Cilento. Afterwards, methods and materials are described and the findings disclosing the revitalizing potential of organic districts presented. Discussion and conclusion round off the manuscript.

2. Biodistricts as a tool for promoting sustainable territorial development

Biodistricts are geographical areas “where farmers, citizens, tourist operators, associations and public authorities enter into an agreement for the sustainable management of local resources, based on organic production and consumption (short food chain, purchasing groups, organic canteens in public offices and schools)” (Basile and Cuoco, 2012: 2). The core mission of organic districts is to spread organic production method and support small-scale farmers (Mazzocchi et al., 2021). Furthermore, biodistricts aim at building territorial development based on principles of organic farming transferring these principles from production level to a territorial rural development approach thereby contributing to the socio-economic regeneration of territories (Stotten et al., 2017). In these areas, agriculture blends into artisan production, recreation and tourism, whereby close attention is paid to the protection of biodiversity and landscape and safeguarding soil, air and water (Guareschi et al., 2020). Thus, biodistricts create links between agriculture and other economic sectors and activities within the territory such as eco-tourism, education and culture, thereby contributing to the multi-functionality of the area and creating a meso-space connecting rural and urban / peri-urban spaces and different stakeholders (Pugliese et al., 2015; Basile, 2017; Passaro and Randelli, 2022). At the same time, the initiative seeks to revitalize the impoverished and abandoned rural territories so as to provide the people living in these territories with better living conditions, ultimately increasing the quality of life in these areas (Basile et al., 2016; Dias et al., 2021). One of the central elements of biodistricts are short supply chains with predominantly direct sales channels through farm shops, local purchasing solidarity groups, vegetable box schemes, producer cooperatives and others (Poponi et al., 2021). The governance in organic districts is represented by a multi-actor model comprised of both public and private actors, and the decision-making process has a bottom-up character (Pugliese et al., 2015; Favilli et al., 2018). This makes the model similar to the Local Action Groups (LAGs) (Schermer et al., 2007; Esparcia et al., 2015). Often, as part of the decision-making biodistricts set up a non-profit association comprised of various stakeholder groups (Pugliese et al., 2015; Passaro and Randelli, 2022). Based on the needs of all the represented groups, members set up an Integrated Territorial Development Plan (Pugliese et al., 2015). However, unlike LAGs, where the Local Development Strategy is implemented through the budget provided by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, organic districts have no specifically allocated budget, and the Plan would be funded through different operational programs (Schermer et al., 2007; Esparcia et al., 2015; Pugliese et al., 2015). To date, no studies looked into the level of local administration’s involvement in organic districts, but it does seem to be limited (Passaro and Randelli, 2022).

Regarding the biodistricts’ performance, only a few studies so far presented a monitoring tool tailored to organic districts. Zanasi et al. (2020) offered a framework based on the Porter’s Diamond model and comprised of five modules with indicators measured on a 0–5 Likert scale. This monitoring tool was applied to Cilento biodistrict (Zanasi et al., 2020). Passaro and Randelli (2022) analyzed the agroecological transition of three organic districts applying the FAO’s Tool for Agroecological Performance Evaluation. Two biodistricts demonstrated advanced and one showed incipient transition to agroecology (Passaro and Randelli 2022). Currently, there are 48 established biodistricts in Europe, and many more are under construction (IN.N.E.R, 2023a).

3. Cilento biodistrict as the first multi-vocational organic district

The concept of organic districts dates back to early 2000s, when the first biodistrict was established in Cilento, Campania region of Italy, responding to a bottom-up push from the small-scale organic farmers to establish local market for their produce (Basile and Cuoco, 2012; Pugliese et al., 2015). Ten mayors from ten municipalities organized a series of public meetings to discuss the matter, which resulted in the agreement on developing “a common narrative around organic farming and sustainability for the valorization of the whole Cilento territory” (Pugliese et al., 2015; Favilli et al., 2018: 5). The constitution of the biodistrict Cilento was initiated in 2004, and in 2009 the Campania region passed the corresponding act making Cilento the first multi-vocational biodistrict (Bio-distretto Cilento Association, 2019; informant interview). In this phase, organic farming was conceived of as a “tool for implementing local development strategies which connected local products with natural and cultural values” (Guareschi et al., 2020: 3). Later, in 2011, a non-profit organization “Biodistretto Cilento Association” was established to ensure structured and coordinated governance of the organic district (Stotten et al., 2017).

Biodistrict Cilento is located in the south of Italy, inside the National Park of Cilento and occupies the total area of 3.196 km2 (Pugliese et al., 2015; Stotten et al., 2017). This area is characterized by a rich and heterogenous landscape, with a long coastland along the Tyrrhenian sea, the Alburni mountains and narrow plains of Valle di Diano (Pugliese et al., 2015; Stotten et al., 2017). The biodistrict currently incorporates 41 municipalities allocated to one of the three associations according to the geographical area: coastland, Alburni mountains and Valle di Diano plains (IN.N.E.R, 2023b). Having started off with 400 organic operators and 2.000 hectares of organic utilized agricultural area (UAA), today the biodistrict counts 1.032 organic operators,1 while its UUA increased to 13.749 hectares (Pugliese et al., 2015; Favilli et al., 2018; Bio-distretto Cilento Association, 2019; Cilento, 2023; IN.N.E.R, 2023b). The main actors of the biodistrict Cilento include individual organic operators, farmers’ union, cooperatives and purchase groups, the Italian Association for Organic Agriculture AIAB and other Associations (Mediterranean Diet, Pro Loco Ceraso, etc.), the authority of the National Park, individual tour operators, tourist associations, research and academia (Pugliese et al., 2015; Stefanovic, 2021).

The Cilento food basket is made up of typical foods of the Mediterranean cuisine (Basile and Cuoco, 2012; Pugliese et al., 2015; Bio-distretto Cilento Association, 2019). The organic quality is assured by third-party certification and participatory guarantee system (PGS) scheme, with the latter being particularly attractive for the small-scale producers in the area (Stotten et al., 2017). Organically produced food in Cilento is mainly distributed through short supply chain outlets comprised of farmers markets and on-farm sales, organic purchase groups, e-commerce, HORECA (hotels, restaurants, canteens) as well as innovative initiatives promoting organic food such as organic beaches and eco-trails (Pugliese et al., 2015; Stotten et al., 2017). The biodistrict created a link between tourist activities and organic agriculture in the area while reshaping and diversifying tourist offers through innovative initiatives like eco-trails and organic beaches (Basile and Cuoco, 2012; Pugliese et al., 2015). Noteworthy are also the organic district’s activities in the realm of social agriculture, which include organic farm-based therapeutic and employment service for the disadvantaged groups (Basile and Cuoco, 2012; Stotten et al., 2017).

4. Materials and methods

To support the argument put forward by the authors, the manuscript relies on the primary data collected in the biodistrict Cilento between June 2019 and January 2020. The data collection took place within the framework of the overarching project “How can organic/biodynamic food systems contribute to the societal transformation toward sustainability?.” Cilento biodistrict was investigated following a case study methodology (Yin, 2003; Yin, 2014). First, an exploratory interview with a case informant was conducted to create a snapshot of the organic district. This was followed by 15 semi-structured interviews with the biodistrict’s key actors. The interviewees were nominated by the informant and additionally identified through snowball sampling method during the first interviews (Bernard, 2006).2 The interviewees were selected so as to cover the entire range of stakeholder groups involved in the biodistrict. At the same time, it was important that all of them represent the key actors – people actively involved in and central to the functioning of the organic district. The interviews aimed at disclosing the outcomes of the biodistrict perceived by its key actors over the years.3 Finally, a focus group discussion was carried out with a group of 13 key actors representing diverse stakeholder groups (farmers, tour operators, agritourism establishments, organic beaches, researchers, schools, local administration and consumers). The focus group employed purposive sampling method (Kitzinger, 2006). The discussion was centered around the various outcome categories addressed by the biodistrict within the environmental, social and economic dimensions.4 Due to the scope of this manuscript, only the outcomes related to territorial development and revitalization of community will be discussed.

5. Revitalizing potential of the biodistricts: insights from Cilento

According to the informant, the idea behind the inception of the biodistrict Cilento was to revitalize the rural area. Indeed, the territory, especially its inland areas, was impacted by depopulation characterized by outmigration of young people leading to land abandonment and ageing farm population (Wilson et al., 2016; Salvia et al., 2019). So, aside from the apparent initial objective of creating a local market for organic food from Cilento, the biodistrict model sought to “start a new approach for a new economy, new development of the area” so as to create new jobs and counter rural exodus, especially that of young people (informant interview). The local market for organic produce was created through the involvement of the public procurement sector (school canteens and hospitals) and tourism, with the latter accomplished through linking internal rural area and the coast (informant interview).

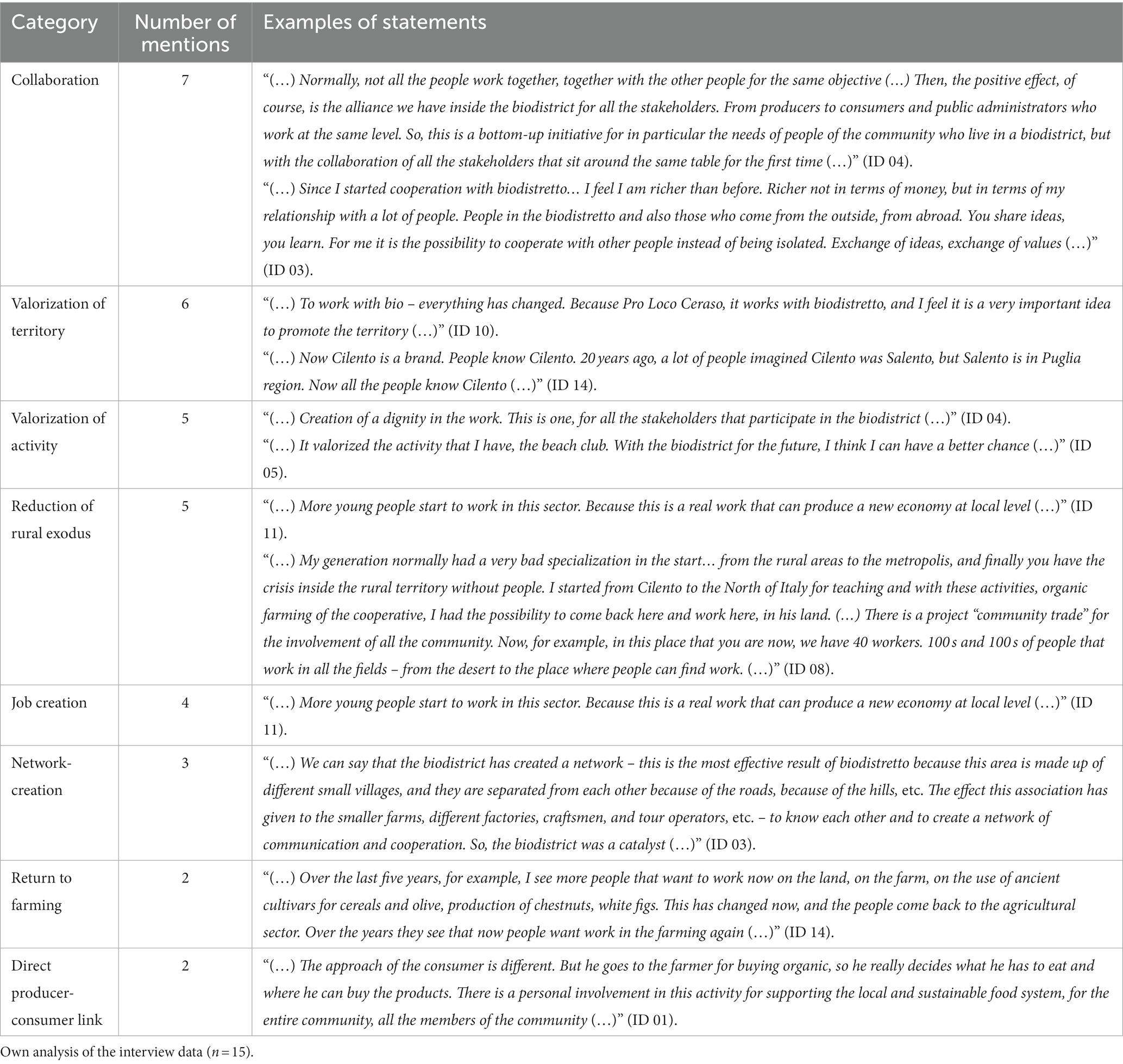

The semi-structured interviews revealed a wide range of community- and territory-related outcomes reported by the key actors. Likewise, the majority of interviewees stated collaboration as one of the most apparent outcomes of the biodistrict, resulting in the actors’ ability to work together toward the same goal and providing a platform for exchange and learning from one another (see Table 1). At the same time, according to the interviewees, the diverse range of activities within the organic district valorized the territory making it known outside of the biodistrict’s borders. In the same vein, the organic district rendered the territory to an attractive employer thereby contributing to the reduction of rural exodus, while restoring the image of farmer’s profession making it attractive again. Moreover, according to the key actors, the biodistrict tends to valorize all the activities performed within its framework thereby dignifying the actors’ work (see Table 1). Not limited to that, due to the very nature of the organic district being a network of actors, it serves as a “catalyst” bringing together various spaciously separated stakeholders providing a networking space for them.

Table 1. Community- and territory-related outcomes of the biodistrict Cilento revealed in the interviews.

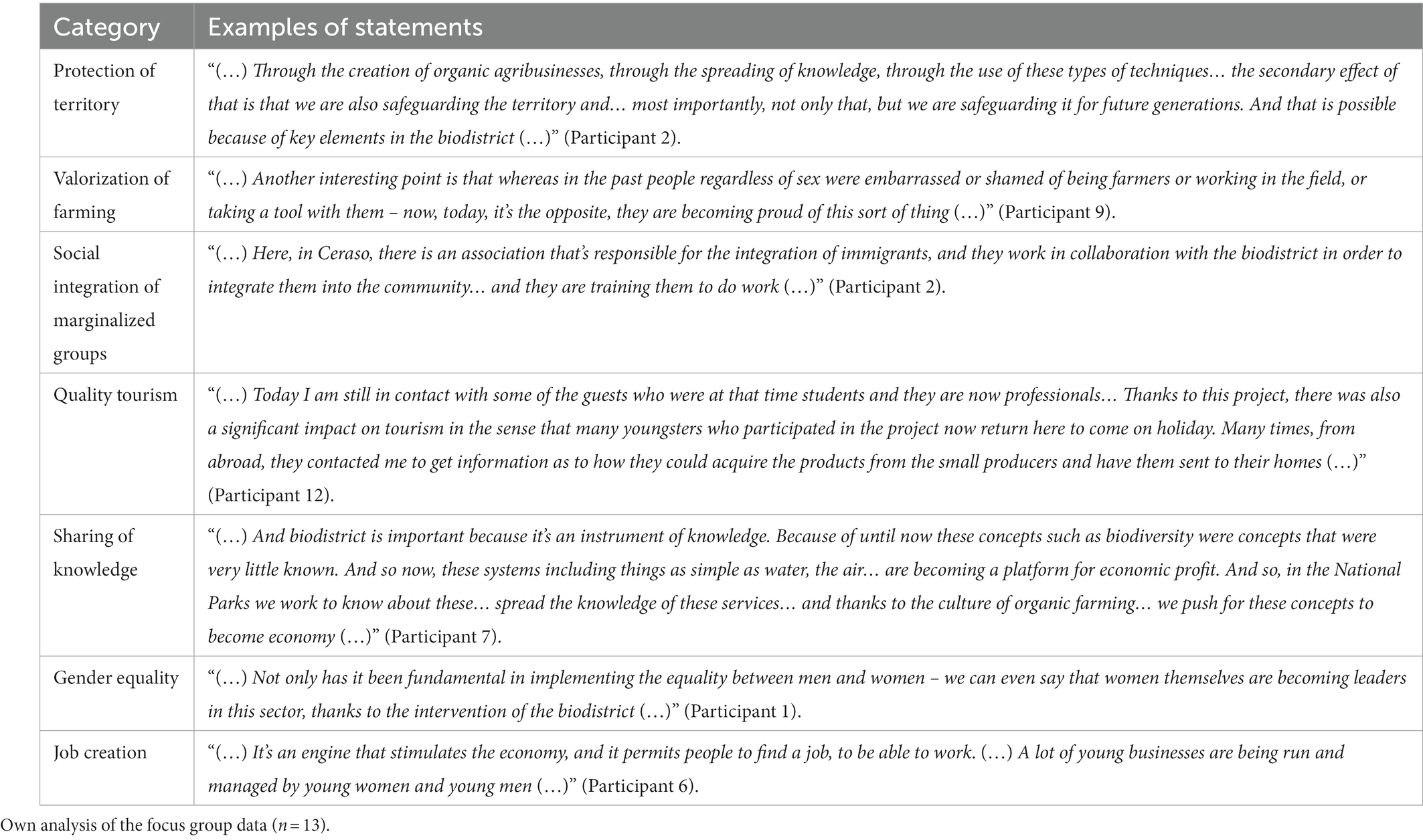

The focus group discussion confirmed some of the Cilento biodistrict’s outcomes revealed in the interviews. Likewise, valorization of farming and protection of the territory have been put forward again (see Table 2). In addition to that, as was explained, the concept of organic districts helps to promote “quality tourism” and valorize organic products from the area:

Table 2. Territory- and community-related outcomes of the biodistrict Cilento revealed in the focus group.

It stimulates what we call the quality tourism, that is that the tourists that come here understand the concept of respect and are invited to observe the workings of the company5 and to respect this way of doing things (Participant 5).

The fact that the production here that is inside of a National Park adds to the prestige of their products… So, for example, an organic product produced in the region of Caserta would not have the same prestige as a product produced in a Cilento National Park area (Participant 11).

Furthermore, the biodistrict’s engagement in the realm of social agriculture was stressed several times throughout the focus group and explained to contribute to the social integration of marginalized groups, which is being accomplished through the employment opportunities offered on organic farms, thanks to the organic district (see Table 2). Within the social dimension, gender roles seem to also be addressed through the biodistrict, contributing to gender equality and women empowerment (see Table 2).

6. Discussion and conclusion

The findings shed light on the biodistricts’ multifaceted contribution to revitalization of rural territories and communities. First, as the Cilento example demonstrated, the multifunctionality of organic districts can help increase the attractiveness of rural territories boosting their development due to a range of new employment opportunities in the area, both in and outside farming, which helps to counteract rural exodus. Moreover, farming as a profession is valorized through the biodistricts model, making agriculture an attractive employment sector again. At the same time, organic districts valorize and protect rural territories and landscapes – the effects previously reported by Basile and Cuoco (2012), Pugliese et al. (2015) and Guareschi et al. (2020, 2022). Owing to these effects, biodistricts are recognized by the IFOAM Organics Europe (2020) as a “success story” and an effective tool for revitalizing rural areas and increasing their attractiveness. This, in turn, facilitates the diversification of tourist activities, with a resulting variety of sustainable agritourism offers such as eco-trails, organic beaches as well as the integration of organic food into menus in tourist establishments – all aiming at not only promoting the area itself, but also the organic food produced in it. Furthermore, the direct producer-consumer links enabled through organic short supply chains with direct marketing channels promoted in organic districts tend to increase personal involvement of the community in the support of local sustainable FSs, while raising awareness to the sustainable mode of food production and the resulting food quality. The awareness-raising effect of direct consumer-producer links in biodistricts was also stressed by Guareschi et al. (2022), who also emphasized the relationship of trust between producers and consumers being formed through this type of interaction. Furthermore, the organic districts model facilitates knowledge transfer and exchange between the actors – the effect observed not only in Cilento, but reported also for the biodistricts Trento, Chianti and Casentino (Passaro and Randelli, 2022).

Looking at the initial driving force behind the organic district’s inception in Cilento, namely the need to establish a local market for organic produce, it supports the observation by Schermer (2005) that the establishment of eco-regions can often be triggered by the efforts to improve the marketing of regional products. Moreover, it was previously reported that biodistricts seem to be more prominent in less favored, or disadvantaged (mountain, hilly, rural) areas experiencing depopulation process (Mazzocchi et al., 2021; Guareschi et al., 2022), which holds true also for Cilento. Such territories might particularly benefit from an economic model based on endogenous territorial characteristics (Mazzocchi et al., 2021). Given the fact that organic farming was historically strong in Cilento, this certainly did play a role in the success of the biodistrict model in Cilento, since organic supply chains are central to the development of organic districts, while a biodistrict itself can be seen “an expression of a local context strongly marked by organic farming,” as also observed in Varese Ligure (Belliggiano et al., 2020: 8).

As the Cilento example demonstrates, not only are biodistricts capable of promoting sustainable production practices and the conversion to organic farming, but they also increase awareness toward quality food and healthy diets and deliver important social outcomes enabling the creation (or strengthening) of a tight-knit community in rural areas. The diverse range of activities in organic districts valorize rural territories transforming them into vibrant multifunctional spaces, attractive to local communities and tourists alike. Capitalizing on the model of organic FSs biodistricts promote sustainable economy and lifestyles thereby contributing to increasing quality of life (Pugliese et al., 2015; Guareschi et al., 2020).

Biodistricts do, however, face a number of challenges potentially hindering them from having a wider outreach. First of all, currently non-existing funding tracks for financing a broad range of activities within organic districts seem to still pose a problem possibly limiting a broader dissemination of the model (Schermer et al., 2007). Aside from that, reliance on a strong leader as facilitator in a multi-actor governance model might pose a risk in case this leader becomes no longer engaged (Favilli et al., 2018). Furthermore, lack of strategic planning skills on the side of organic farmers might impede territorial development actions and multi-sectoral cooperation (Schermer and Kirchengast, 2008). Finally, it should be noted that although organic districts do represent a very promising and much needed research area, the corresponding research is still limited offering a gap to be filled.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following restrictions: protection of confidentiality/participants’ privacy. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to the corresponding author, Mrs. Lilliana Stefanovic, Section of Organic Food Quality, University of Kassel, Germany: bC5zdGVmYUB1bmkta2Fzc2VsLmRl.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OA-M: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Software AG Foundation within the framework of the project “How can organic/biodynamic food systems contribute to the societal transformation toward sustainability?” (ID8333).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the interviewees and focus group participants for contributing to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The farms are represented by small- to medium size family farms with an average size of five hectares (Pugliese et al., 2015).

2. ^Out of 15 key actors interviewed, 13 were nominated by the informant and repeatedly nominated by the interviewees, and two were nominated by the key actors interviewed.

3. ^The outcomes investigated through semi-structured focused on three levels – individual, community- and ecosystem-related.

4. ^Focus group built upon the findings from semi-structured interviews and represented an in-depth investigation of the outcomes in five dimensions – ecosystem stability, food and nutrition security, improved livelihoods, inclusive economic growth, and governance and partnerships. The target group of the focus group was the same as that of semi-structured interviews, namely the key actors representing the various stakeholder groups of the biodistrict.

5. ^Word “company” refers to the organic farm and agri-tourism establishment.

References

Basile, S. (2017). 52 profiles on agroecology: the experience of bio-districts in Italy. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-bt402e.pdf (Accessed July 25, 2023).

Basile, S., and Cuoco, E. (2012). Territorial bio-districts to boost organic production. Available at: https://www.ideassonline.org/public/pdf/BrochureBiodistrettiENG.pdf (Accessed July 25, 2023).

Basile, S., Nicoletti, D., and Paladino, A. (2016). Report on the approach of agro-ecology in Italy. Padula, Italy: Osservatorio Europeo del Paesaggio.

Belliggiano, A., Sturla, A., Vassallo, M., and Viganò, L. (2020). Neo-endogenous rural development in favor of organic farming: two case studies from Italian fragile areas. Eur. Countryside 12, 1–29. doi: 10.2478/euco-2020-0001

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE.

Bio-distretto Cilento Association (2019). The Cilento bio-district. Available at: http://www.ecoregion.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/CILENTO-brochure_EN.pdf (Accessed July 25, 2023).

Caprile, A., and McEldowney, J. (2021). EU, European Parliamentary Research Service. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)696182 (Accessed October 16, 2023).

Caron, P., Ferrero, Yde, Loma-Osorio, G., Nabarro, D., Hainzelin, E., Guillou, M., et al. (2018). Food systems for sustainable development: proposals for a profound four-part transformation, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 38:41. doi: 10.1007/s13593-018-0519-1

Cilento, G. (2023). The story of Cilento, the first Organic District in the world. 9th ALGOA & 4th GAOD summit, June 5, 2023, Kauswagan, Philippines.

Dias, R. S., Costa, D. V. T. A., Correia, H. E., and Costa, C. A. (2021). Building bio-districts or eco-regions: participative processes supported by focal groups. Agriculture 11:511. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11060511

Esparcia, J., Escribano, J., and Serrano, J. J. (2015). From development to power relations and territorial governance: increasing the leadership role of LEADER local action groups in Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 42, 29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.09.005

EU (2020). Farm to fork strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (Accessed July 25, 2023).

Favilli, E., Ndah, T. H., and Barabanova, Y. (2018). 13th European IFSA Symposium, 1-5 July 2018. Chania, Greece.

Guareschi, M., Maccari, M., Sciurano, J. P., Arfini, F., and Pronti, A. (2020). A methodological approach to upscale toward an agroecology system in EU-LAFSs: the case of the Parma Bio-District. Sustainability 12:5398. doi: 10.3390/su12135398

Guareschi, M., Mancini, M. C., Lottici, C., and Arfini, F. (2022). Strategies for the valorization of sustainable productions through an organic district model. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 47, 100–125. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2022.2134270

IFOAM Organics Europe (2020). IFOAM-EU feedback to the Commission’s public consultation on rural areas. Available at: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2021/04/IFOAMEU_Consultation_ruralareas_202011.pdf (Accessed July 25, 2023).

IN.N.E.R. (2023a). EU organic districts map. Available at: https://www.ecoregion.info/2020/11/09/organic-districts-map/ (Accessed July 25, 2023).

IN.N.E.R. (2023b). Distretti biologici: o Bio-Distretti o Eco-Regioni. Available at: https://biodistretto.net/bio-distretto-cilento/ (Accessed September 5, 2023).

Kitzinger, J. (2006). “Focus groups” in Qualitative research in health care. eds. C. Pope and N. Mays (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd), 21–31.

Mazzocchi, C., Orsi, L., Bergamelli, C., and Sturla, A. (2021). Bio-districts and the territory: evidence from a regression approach. Aestimum 79, 5–23. doi: 10.36253/aestim-12163

Passaro, A., and Randelli, F. (2022). Spaces of sustainable transformation at territorial level: an analysis of biodistricts and their role for agroecological transitions. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 46, 1198–1223. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2022.2104421

Poponi, S., Arcese, G., Mosconi, E. M., Pacchera, F., Martucci, O., and Elmo, G. C. (2021). Multi-actor governance for a circular economy in the Agri-food sector: bio-districts. Sustainability 13:4718. doi: 10.3390/su13094718

Pugliese, P., Antonelli, A., and Basile, S. (2015). Full case study report: Bio-Distretto Cilento - Italy. Bari, Italy: CIHEAM & AIAB. Available at: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/29252/ (Accessed July 25, 2023).

Rockström, J., Edenhofer, O., Gaertner, J., and DeClerck, F. (2020). Planet-proofing the global food system. Nature Food 1, 3–5. doi: 10.1038/s43016-019-0010-4

Salvia, R., Kelly, C. L., Wilson, G. A., and Quaranta, G. (2019). A longitudinal approach to examining the socio-economic resilience of the Alento district (Italy) to land degradation—1950 to present. Sustainability 11:6762. doi: 10.3390/su11236762

Schermer, M. (2005). The impacts of eco-regions in Austria on sustainable rural livelihoods. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 3, 92–101. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2005.9684747

Schermer, M., Groier, M., Kirchengast, C., and Miglbauer, E. (2007) Bioregionen als Modell für nachhaltige regionale Entwicklung: Standpunkte & Handlungsempfehlungen an Regionen, Beratung, Administration & Politik.

Schermer, M., and Kirchengast, C. (2008). Eco-regions: how to link farming with territorial development. 16th IFOAM organic world congress, Modena, Italy, June 16-20, 2008. Available at: http://orgprints.org/12099 (Accessed September 18, 2023).

Stefanovic, L. (2021). Basis for monitoring the performance of sustainable development goals in organic food systems. [Dissertation]. Kassel: Kassel university press.

Stotten, R., Bui, S., Pugliese, P., Schermer, M., and Lamine, C. (2017). Organic values-based supply chains as a tool for territorial development: a comparative analysis of three European organic regions. Int. J. Soci. Agricul. Food 24. doi: 10.48416/ijsaf.v24i1.120

Stotten, R., and Froning, P. (2023). Territorial rural development strategies based on organic agriculture: the example of Valposchiavo, Switzerland. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:2993. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1182993

Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., et al. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393, 447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

Wilson, G., Quaranta, G., Kelly, C. L., and Salvia, R. (2016). Community resilience, land degradation and endogenous lock-in effects: evidence from the Alento region, Campania, Italy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 59, 518–537. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2015.1024306

WWF (2020) in Living planet report 2020 - bending the curve of biodiversity loss. eds. R. E. A. Almond, M. Grooten, and T. Petersen (Gland, Switzerland: WWF)

Keywords: biodistricts, rural revitalization, revived community, territorial development, quality of life

Citation: Stefanovic L and Agbolosoo-Mensah OA (2023) Biodistricts as a tool to revitalize rural territories and communities: insights from the biodistrict Cilento. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1267985. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1267985

Edited by:

Stefano Targetti, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Francesco Galioto, Council for Agricultural and Economics Research (CREA), ItalyCopyright © 2023 Stefanovic and Agbolosoo-Mensah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lilliana Stefanovic, bC5zdGVmYUB1bmkta2Fzc2VsLmRl

Lilliana Stefanovic

Lilliana Stefanovic Ohemaa Achiaa Agbolosoo-Mensah

Ohemaa Achiaa Agbolosoo-Mensah