- 1Department of Economics and Management (DISEI), University of Florence (UNIFI), Florence, Italy

- 2Latin American and Caribbean Research Centre (CIALC), National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico

Farmers’ Markets (FMs) have gained relevance in recent years as increasingly acknowledged to be critical to turn to more equitable food systems, easing agroecological transition, and preserving biocultural heritage. However, the issue of the forms of social and institutional coordination needed to create, organize, manage and promote FMs is a recent topic in the literature, and their governance is still poorly considered. Based on a set of case studies in Tuscany, Italy, this paper intends to contribute to filling this gap by analysing the forms of governance and the role of different stakeholders. The hypothesis is that FMs are social constructions that respond to processes of social and institutional innovation through direct exchanges between producers, consumers and other stakeholders, articulated at both local and non-local level. The aim of the paper is to explore the interactions between stakeholders and the corresponding forms of multi-level governance that emerge. The method for testing the hypotheses is qualitative, through semi-structured interviews to FMs managers and conversations with producers and other stakeholders, conducted between May and August 2022 in Tuscany. The research was complemented by consultation of indirect sources, such as FMs websites and social networks. The results are summarized in the elaboration of a three-dimensional and territorially embedded governance model. The first dimension refers to the management of internal relations between stakeholders within the FM. The second corresponds to the activation of dialogue, negotiation, and agreement with the municipality and other local authorities, and with local farmers’ unions. The third type corresponds to vertical flows between the FMs and extraterritorial bodies, i.e., regional government, regional and national farmers’ unions and other stakeholder associations. It is important to note that at FMs level, processes of hybridization between the different types of governance are established. The article contributes to the analysis of FMs as economic and social constructions and may be useful for establishing comparative frameworks around institutional and collective action dimensions, multi-actor and multilevel studies of governance.

1 Introduction

Farmers’ Markets (FMs) have attracted the attention of scholars, social movements promoting the right to food, activists, food producers, consumers, and policy makers, especially since the 2000s. FMs are characterized by the involvement of a plurality of farmers (and sometimes other producers, such as small-scale artisanal agri-food processors) who offer directly to consumers, on a regular basis and in a coordinated way, food products grown or bred (and eventually processed) close to the place where the market is held. FMs are often advocated to encourage and promote the values of fair trade, healthy and locally produced food, sustainable production practices, small producers, and solidarity between urban and rural communities. According to some scholars, the geographic and relational proximity in FMs exert positive effects on the economy and the environment. On the one hand, they promote fair trade by eliminating or reducing intermediaries (Hinrichs, 2000; Jarosz, 2008; Belletti and Marescotti, 2013). In addition, they can promote agroecological transition, thus favouring more sustainable food production and consumption models able to respond to future emergent challenges and reconciling economic viability and fairness, social wellbeing and equity and environmental care (Di Iacovo et al., 2014; Rover et al., 2017; Petropoulou et al., 2022; Coelho de Souza et al., 2023), as well as the protection of biocultural heritage (Belletti et al., 2022).

FMs are part of short food supply-chains (SFSCs) arrangements, which have given rise to the formation of alternative food networks claiming new forms of production, consumption and lifestyles (Marsden et al., 2000). As part of these networks, FMs are a manifestation of economic, social and institutional innovation that have spread mainly in Western Europe, the United States, Canada, and Japan, as well as in other countries in Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean over the last two decades (Enthoven and Van den Broeck, 2021; Davies et al., 2022; Hyland and Macken-Walsh, 2022).

According to Kebir and Torre (2014), the innovation in SFSCs can be analysed as collective action translated into civic initiatives with that aim to boost geographic and organizational proximity based on the quality of territorial assets. Similarly, Martens et al. (2023) analyse the role of innovative forms of collaboration in the sustainable transformation of local agrifood systems, under the lens of geographic, social, organizational, institutional and cognitive proximity. Geographical proximity refers to the physical distance in localized systems articulating rural and urban flows in a specific territory. Social proximity refers to the closeness and intensity of relationships between the actors in the supply chain, and is based on values such as recognition, trust, solidarity, and reciprocity. Organizational proximity regards the dimension and structure of collective action in the supply chain. Institutional proximity concerns formal and informal norms and rules in local collective initiatives (see also Loconto et al., 2016) while cognitive proximity concerns the knowledge background of the actors involved.

The issue of governance emerges as a central aspect in SFSCs, to coherently organize, manage and boost the different kinds of proximity relationships between the actors. It is through governance that interactions between the various stakeholders take place and innovation processes are generated and managed. In particular, governance in FMs refers to the set of rules, structures, and processes that guide and regulate their birth and operation. It involves strategic management and decision-making mechanisms, organizational structures, and policies that determine how the FM is managed, ensuring fairness, transparency, and efficiency in its functioning. The analysis of SFSCs governance, and particularly FMs, should not only take into account their internal dimension related to planning, organization and management, but also the relationships between the FMs and the external environment, both at local and extra-local level. Stakeholders analysis as value creation and strategy formulation (Brugha and Varvasovszky, 2000; Freeman et al., 2008) at these different territorial scales is a fundamental task to understand how forms of coordination are built in the FMs.

Despite its importance in organizing proximity relations between stakeholders and actors in SFSCs, the issue of governance has been little explored in literature. With this paper we try to contribute to fill this gap by investigating how interactions in FMs between producers, consumers and other stakeholders—at internal, local and extra-local level—are shaped and organized through multi-level governance processes.

Who are the actors and other stakeholders that contribute to the creation, consolidation and management of FMs and what is their role and their interactions? What are the relevant aspects of the governance of FMs? Which governance arrangements and models emerge? These are the research questions that this article aims to answer by examining a set of case studies in the region of Tuscany, Italy, where FMs have a long tradition. The hypothesis from which we start is that FMs are social constructions that correspond to multi-level processes of social and institutional innovation generated by stakeholders. These processes lead to the construction of vertical, horizontal and hybrid forms of decision-making and strategies in each of the markets, involving both producers, consumers and other stakeholders at local and extra-local levels. The aim of this paper is to analyse the multilevel governance processes characterizing FMs, in order to uncover how the different typologies of FMs regulate their internal functioning, decision-making and relations between the actors involved, which kind of relations they entertain with external local and extra-local stakeholders, and how the different governance levels interact with each other and influence the FM itself.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the conceptual model as a result of literature review. After presenting in Section 3 the materials and the methods used, Section 4 presents in detail the results of the interviews and fieldwork. In Section 5, the discussion and validation of the hypothesis are addressed. The conclusions consider the relevance of this study and some potential future lines of research and policy implications.

2 Literature review and conceptual model

Governance has been defined as an umbrella concept (Porras, 2016), which implies a lack of precision in the subject. In order to avoid the common mistake of taking the definition of governance for granted, we will briefly recall some features of this concept in the literature on FMs and in the broader field of studies on Localized Agri-Food Systems (LAFS) of which FMs are often an expression, in order to draw out the elements useful for the construction of the conceptual model. LAFS are a type of organization of agrifood activities, in which territorial dynamics play a decisive role in terms of the coordination between stakeholders and the development of production activities (Muchnik, 2006).

The concept of governance has developed in several stages. In its origins, it was linked to the crisis of bureaucratic governments in the face of the emergence of society’s actions. For public administration, this concept was a recognition of decentralization and the emergence of civil society (Kooiman, 1993) and governance by inter-institutional and self-organized networks (Rhodes, 1997). For other scholars, this concept means coordination and cohesion among multiple actors, including institutional ones, with different purposes and objectives (Pierre and Peters, 2000). For still others, governance is the way of governing to achieve the common objectives of actors with different purposes in increasingly complex societies (Kooiman, 2003) and with decision-making centers adapted to the characteristics of local economies (Ostrom, 2014).

The evolution of governance as the management of local resources, as well as its role in the expression of solidarity economies based on trust, has been transcendental for studies of territorial governance conceived as the construction of multilevel agreements and institutions. In the literature on localized agri-food systems, the themes of multilevel coordination between stakeholders, democratic participation and accountability at the local level, social capital building and agroecology emerge from the governance perspective (Torres Salcido and Sanz Cañada, 2018; Sanz-Cañada et al., 2023). According to the literature on localized agri-food systems, the innovation of FMs is based on three fundamental axes: (1) the embeddedness of food (Hinrichs, 2000; Sonnino, 2007; Brinkley, 2017) and the relationships between producers and consumers (Chiffoleau, 2009); (2) the collective strategies aiming at valorising origin products, and the related effects on territorial development (Vandecandelaere et al., 2010), and (3) the recognition of food as a relevant driver in the agenda, design and implementation of public policies (Sage, 2003; Troccoli et al., 2021).

For the purposes of this paper, governance is interpreted as a multilevel territorial management process whose aim is to align different stakeholders around shared values and a project, and to build collaborative practices, norms, and agreements between them. This process is multilevel because it involves the micro level (here corresponding to the single FM), the meso level (corresponding to the territory where the FM operates) and the macro level (involving extraterritorial dimensions and actors). Public management bodies act as additional stakeholders, aiming at regulation, promotion and support, including through financial support plans and programs. The objective of governance is to contribute to the construction of capacities and to creation of economic and social value in an inclusive manner based on shared values and goals. The morphology of governance varies according to the specific historical and social circumstances: top-down, bottom-up and hybridization in decision making (Dunsire, 1993; Kooiman, 2003).

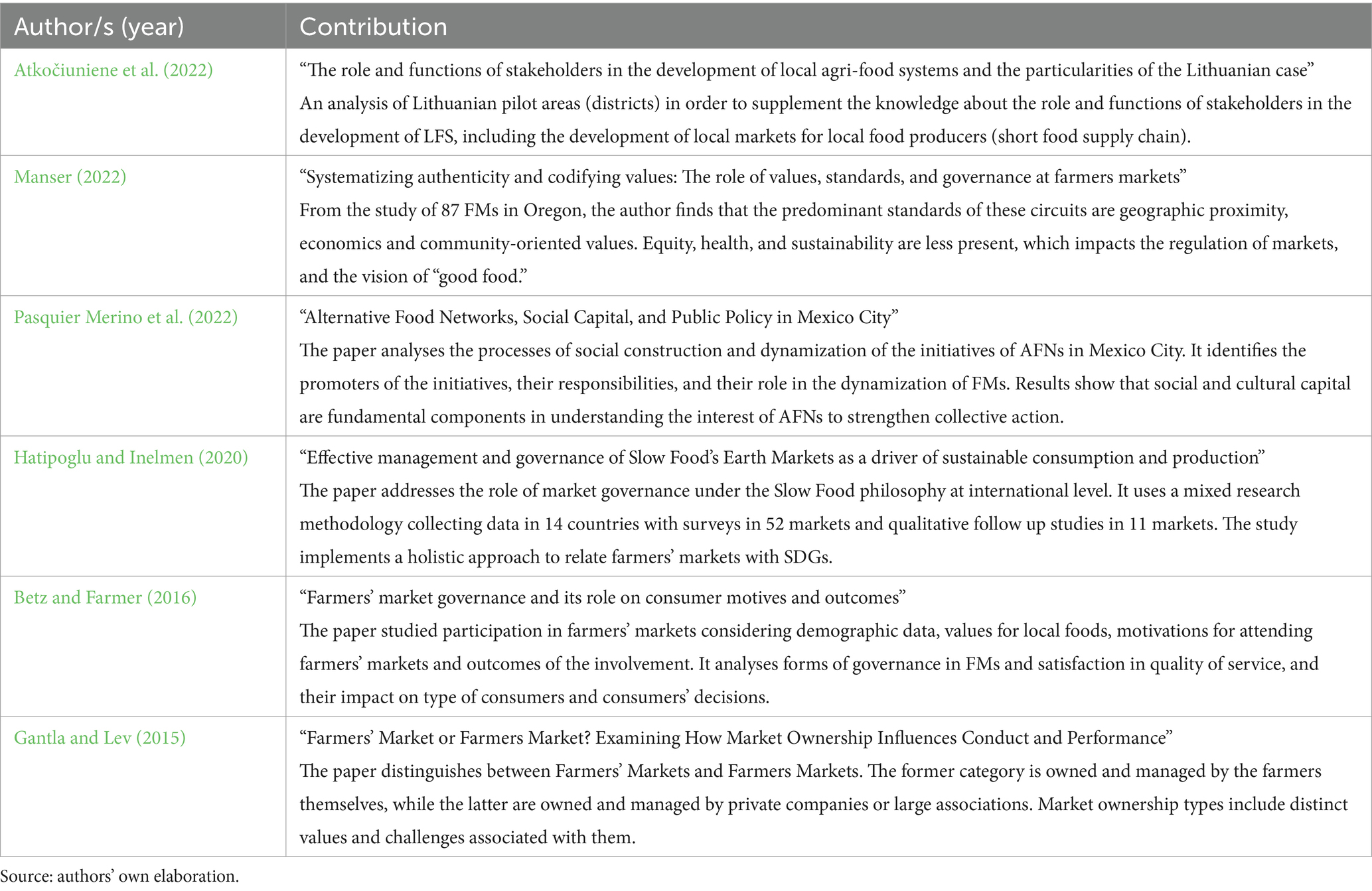

However, despite its importance, interest by both scholars and policy makers on the role of stakeholders in the governance of FMs is relatively recent. In Table 1, we report some of the very few existing publications specifically dealing with FMs governance and/or management1 and their main contribution.

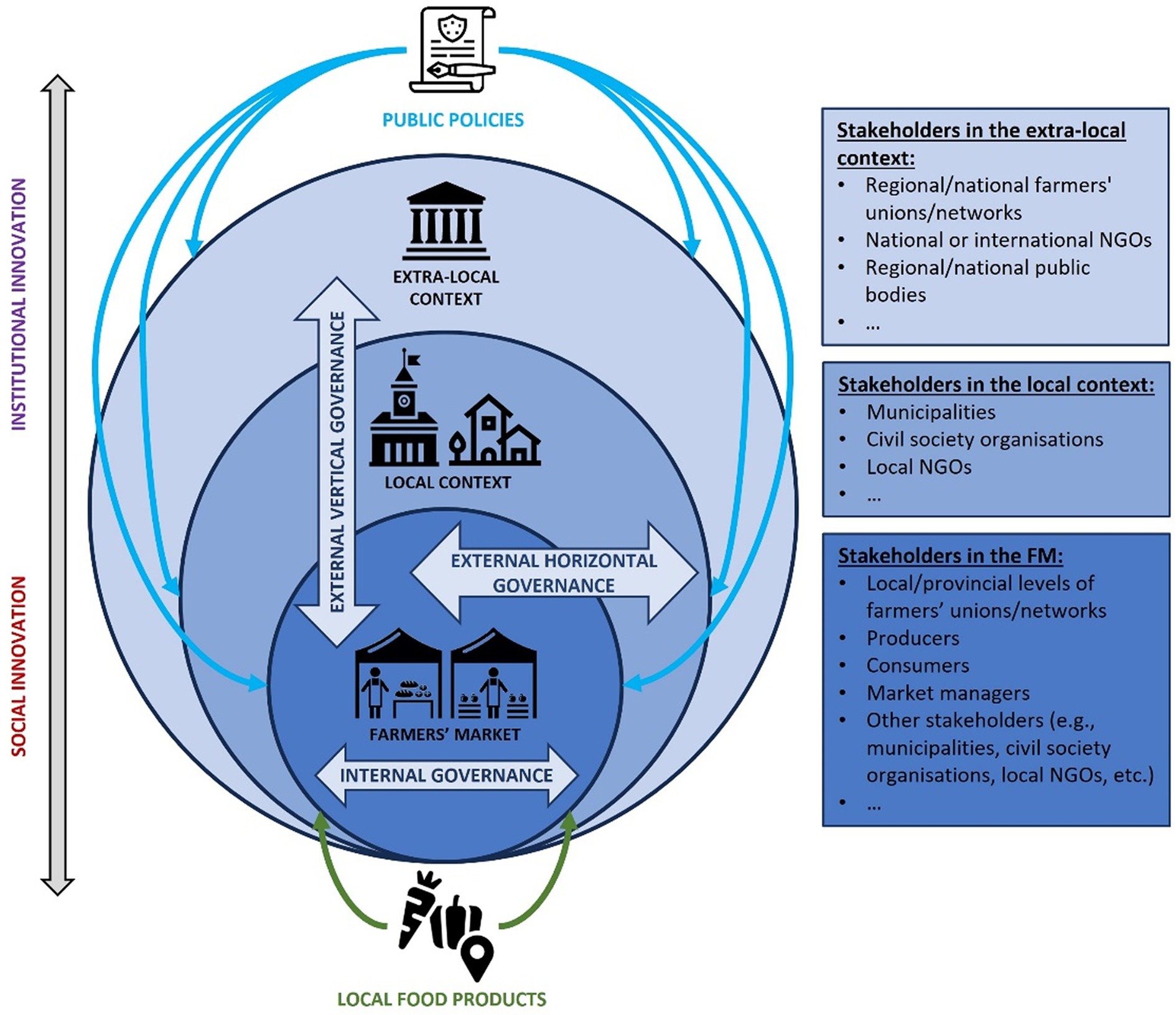

The literature review highlights the plurality of stakeholders involved with different title and roles, and with different perspectives and interests, in the activation processes of FMs and in their management. Figure 1 shows the multilevel governance model adopted in our research, which is inspired by polycentric forms of governance (Ostrom, 2014) and highlights three different scales. At the FM internal scale, the activation starts from the need of local farmers and the availability of local products suitable for direct sale, coupled to the existence of a local demand for these products. Farmers, and sometimes other stakeholders’ categories (consumers, local public bodies, non-governmental organizations), act to organize and give governance to the market, defining the identity of the market and a set of rules concerning, e.g., access, frequency, types of production and producers. The external horizontal scale of governance reflects the construction and management of horizontal forms of decision making and territorial integration in the local territorial context, both public and private ones. This model extends into a third scale of governance, the external vertical, connecting the “local” to regional, national and international (including European Union) levels, when relevant. The regulations and programs respond to a vertical decision-making scheme due to the formulation of public policies. However, this model does not exclude hybridizations originating from the adaptation of rules and regulations to territorial contexts. The application of standards, laws, regulations, and quality certification follows bottom-up and top-down decision-making processes at the three levels of governance. In this way, a localized system is articulated with stakeholders internal to the market and integrated into the territory and extraterritorial stakeholders at regional, national, or multinational levels.

In accordance with what has been said so far, the research focuses on the role of stakeholders in the construction of multilevel governance from a territorial perspective.

3 Materials and methods

Tuscany is a region located in Central Italy, of great importance for its biocultural heritage and the civic and institutional networks also related to rurality, agriculture and food that have fostered the growth of FMs. For several years, the government of the Region of Tuscany has also promoted the spread of FMs through promotional activities and the granting of financial incentives, as have some Municipalities.

The spread and activity of FMs is remarkable in all the provinces of Tuscany. According to a specific census carried out by the Region of Tuscany,2 155 FMs were active throughout Tuscany in 2019, for a population of approximately 3.73 million inhabitants. The vast majority of these FMs (145) are held on a regular basis, mostly weekly. Following the pandemic, the number of FMs in Tuscany has increased. Many of them are promoted by the two main national Farmers’ Unions, the Coltivatori Diretti (Coldiretti) through the Campagna Amica (“Friendly Countryside”) network, and the Confederazione Italiana Agricoltori (CIA), through the Spesa in Campagna (“Shopping in the Countryside”) network, and by Slow Food, which promotes the Mercati della Terra (“Earth Markets”) network. On the other hand, there is a number of FMs initiatives supported by local NGOs, groups of producers and/or consumers, and municipalities—or a combination of them.

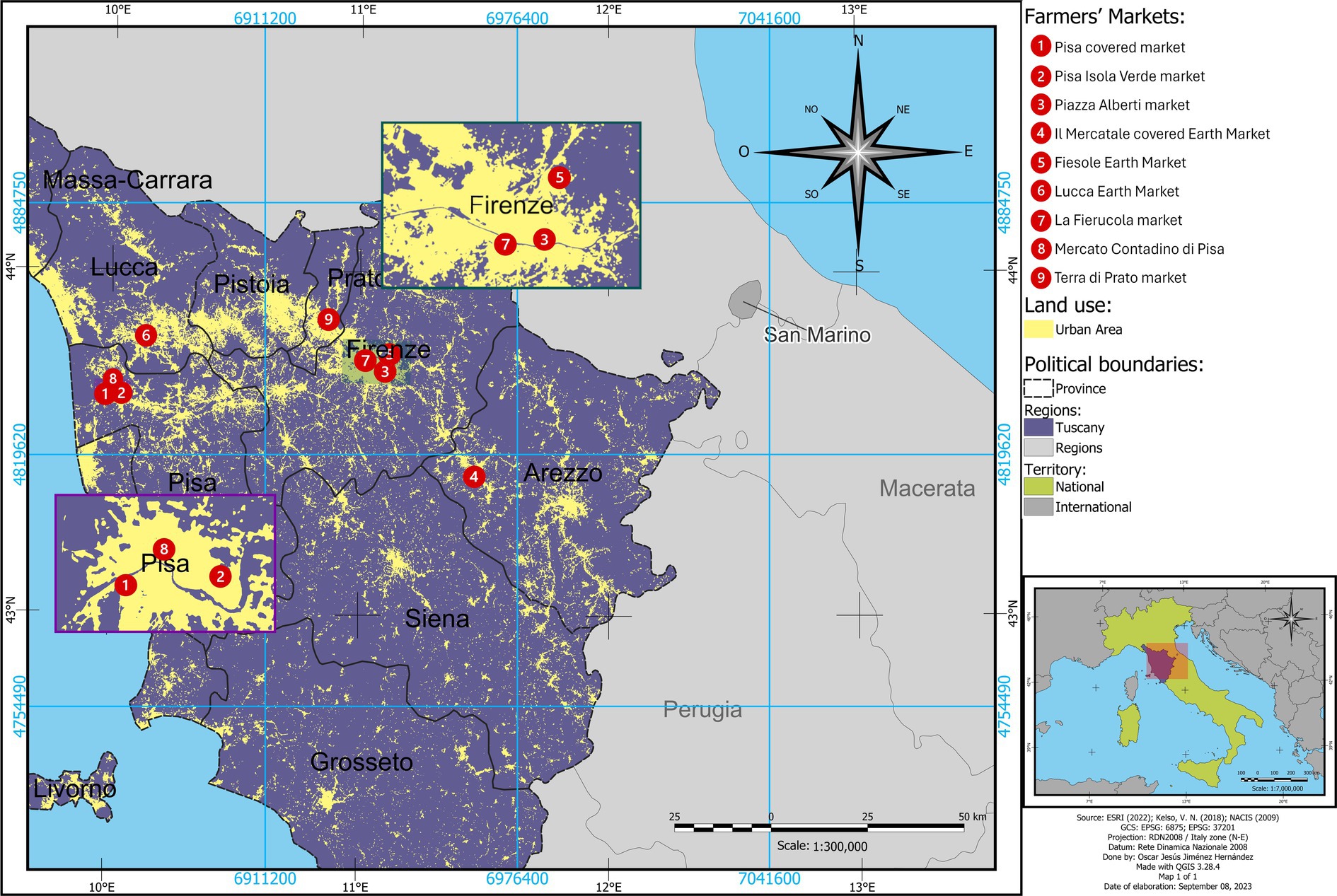

The direct sources for this research come from nine interviews with FM managers and one interview with the head of a regional FM network (CIA Spesa in Campagna), all conducted between May and August 2022. In addition, we conducted interviews with farmers and other vendors (small artisans) during our visits, for a number of 22 in total, which allowed a broader view of the functioning and objectives of each market. Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of the FMs where the interviews were conducted, which cover the northern part of the Tuscany.

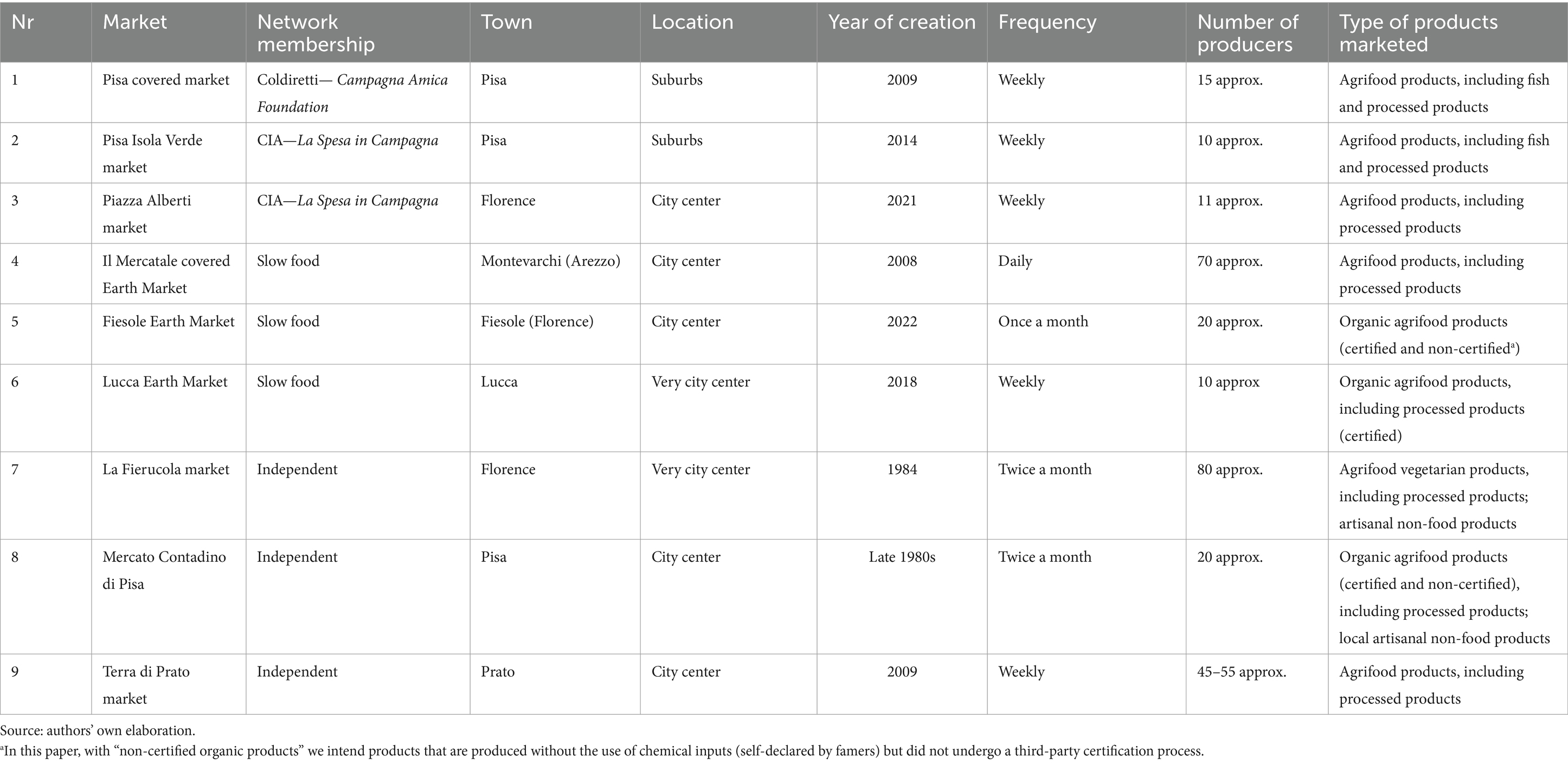

The nine FMs of the sample cover a range of different situations in terms of location, date of creation, frequency of the market, number of producers involved, and types of products marketed (Table 2). Most of them belong to some nation-wide network, namely farmers’ union (Coldiretti and CIA) or the Slow Food movement, while others are set up as independent markets.

Situated in five provinces of Tuscany, the nine FMs are located in different urban contexts, some being in the very center of cities, while others in more suburban districts. Consequently, the type of consumers is also different, with a greater presence of tourists in FMs located in the historical centers of art cities (Florence, Pisa, Lucca).

Concerning the specific physical space in which the markets are installed, which depends on critical issues and arrangements between the various private and public stakeholders involved, most of the FMs analysed are held in public open spaces, some other occupy public covered or closed spaces, and only one of them (Pisa Isola Verde market) benefits from the spaces of a civil society cultural association.

Most of the markets in the sample are already well-established since at least 5 years, while two of them are more historical markets (La Fierucola and Mercato Contadino di Pisa), and two others are very recent markets (Fiesole Earth Market and Piazza Alberti market).

Concerning the frequency of the markets, the majority of them are held weekly, except for a few of them which are held with a lower frequency (once or twice a month) and one of them which is open daily (Il Mercatale covered Earth Market). On average, these FMs are composed of 10–20 producers, with the exception of three bigger markets having 50–80 producers (Il Mercatale, La Fierucola, Terra di Prato), but sometimes producers’ participation varies according to products’ availability during the different seasons. With regard to marketed products, in the most of the FMs analysed, producers directly offer both fresh products (mainly fruit and vegetables, more rarely meat and fish) and processed products (bread, cheese, jams and preserves, olive oil and honey), while a few markets also see the participation of local non-food artisanal producers.

The analysis of the interviews was complemented by indirect sources: (1) information and statistics available on the websites of Coldiretti—Campagna Amica, of CIA—Spesa in Campagna, and Slow Food – Mercati della Terra, or directly provided by the persons responsible of the FM and organizations; (2) Facebook of the FMs and other social media; (3) the regulations of each FM; and (4) dissemination materials collected during our visits to the markets.

The research follows a case study methodology. According to Yin (1994), this is a legitimate methodological strategy: (a) to study contexts in which the researcher has no control over the events he/she is confronted with; (b) to analyse emergent phenomena of social life; and (c) to answer questions about how and who. Although it is particular in nature, the results can move from description to generalization (Giménez and Heau Lambert, 2014). The case study may aim to learn about local management models and institutions in order to compare experiences in common resource management (Poteete et al., 2010). The analysis of the information is inductive because of its interest in grounding the method through the analytical construction of the categories from the bottom up (upward) (Bryant and Charmaz, 2007). In this sense, the case can be complemented with stakeholder analysis to assess the inclusion of stakeholders in strategies, decision-making mechanisms and in the definition of the future of organizations (Brugha and Varvasovszky, 2000).

The methodological strategy followed for the research consisted of several steps:

1. First, based on the literature and previous experience, an operational concept of FM governance was defined according to the multilevel model discussed in Figure 1. The formulation of the questionnaire aimed at obtaining information by means of semi-directed questions in the following sections: activation process, characteristics, stakeholders involved and relationships, internal organization and management, financing, consumer characteristics and future perspectives.

2. Secondly, the interview was designed to be conducted specifically with stakeholders who have a vision that integrates market knowledge and interactions with other territorial levels. Therefore, the subjects interviewed were FM coordinators and regional managers. The sample of interviewees was selected purposively by combining the knowledge and relationship networks of researchers following a snowball technique. With regard to the dynamics of the interviews, the subjects were encouraged to openly express their opinions and emotions (Valles Martínez, 2002). For this reason, the interviewees were asked to deepen their answers, but always within the framework of the previously designed questions.

3. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for their subsequent analysis by means of a codification of the interviewees’ discourses based on the themes emerged in the literature review and defined in the conceptual framework, and information were then systematised in the comparison tables reported in Section 4 (Tables 3–5).

4. The interview in each of the markets provided the opportunity to carry out a non-participant observation exercise and to talk to some producers individually. Their insights were very helpful in obtaining a complementary point of view to that of the market managers.

4 Results

This section presents the main, organizational and governance characteristics of the nine FMs object of our study,3 as resulting from desk analysis, interviews and direct observation. After a description of the genesis and evolution of the sample FMs and the values orienting them, we analyse these FMs as regulated spaces, identifying what and how FMs regulate, and finally we directly address internal and external governance issues.

4.1 The social construction of FMs: genesis and evolution

The results of the interviews highlight how FMs originate from different categories of stakeholders oriented by a variety of values and motivations, and how they undergo different evolution pathways over time.

In a number of cases the initiator belongs to the agriculture world, pushed by the motivation of opening a marketing space especially for small farmers. In three out of the nine cases, FMs were activated within Farmers’ Unions FMs’ networks. CIA and Coldiretti both originated in the post-World War II years as Farmers’ Unions. Although of different political-ideological orientation (CIA more left wing, Coldiretti more center), both Unions have the mission of defending the interests of small family farmers and representing them in the political arena. Both Unions developed a dense territorial network of technical, economic and fiscal assistance centers for farmers, and in the last 20 years have launched initiatives to strengthen a more direct connection of farmers with consumers and society at large. The creation of a national network of FMs is functional not only to help member farmers to directly market their products, but also to give greater social visibility to the claims of farmers and agriculture.

According to its website,4 Coldiretti has the largest direct sales network in the world, with more than 10,000 marketing points including FMs, agritourism and processing businesses. In 2008 Coldiretti created the Campagna Amica Foundation to promote a network of FMs Campagna Amica “zero miles,” conceived as a meeting place between farmers and city dwellers. The aim of this initiative is to express the value and dignity of Italian agriculture by highlighting its role in the care of the environment, territory and traditions, in facilitating fairness in food chains and access to food at a fair price of fresh and quality products. Similarly, CIA launched the La Spesa in Campagna5 initiative with the aim of promoting the territory, short chains, and food quality. This initiative favours direct relations between farmers and consumers through the creation of collective selling points, mainly FMs. La Spesa in Campagna is made up of five thousand small agricultural enterprises that must comply with the CIA’s rules and participate in the organization through their representatives.

In other FMs consumers (in associative form or through representative organizations) promote the creation of FMs, motivated by a search for higher quality produce but also by a desire to forge alliances with the world of farming. Three out of our nine analysed FMs are part of Slow Food – Mercati della Terra network. Slow Food is today an international non-governmental organization founded in Italy in the 1980s by activists who demanded the right of everyone to have access to healthy, fair, and clean food, claiming the importance of valuing farmers as custodians of territories, biodiversity, and local traditions.6 To this aim Slow Food launched in 2004 the Mercati della terra (“Earth Markets”) project with the purposes of opening a space for small-scale farmers engaged in agroecological methods and in preservation of local agrobiodiversity and traditional foods normally excluded from conventional marketing channels, and also to giving urban consumers access to local seasonal products, produced with respect for the environment and for workers’ rights. Slow Food conceives the Mercati della Terra not only as selling points, but also as places for promoting dialogue between producers and consumers and encouraging community development also through the exchange of knowledge and taste education.

Less frequent is the case where the initiative for the creation of FMs comes from public institutions, with the desire to improve relations between the city and countryside, favouring citizens’ access to local products and at the same time to trying to preserve a small peri-urban agriculture. The analysis highlights as in a number of cases the activation of FMs appears as a top-down process, with a key central stakeholder (usually a producers’ or consumers’ association) willing to set up a specific marketing project. This project includes the identification of the physical space, the support to the emergence of a group of producers interested and able to participate regularly in the FM and their selection according to specific criteria, the definition of the business model of the FM encompassing the FM marketing strategy and access to the economic and material resources needed to set up the market and give it an identity, by means of stalls (gazebi), signs and homogeneous marketing images. That is the case, for instance, of the three FMs belonging to the Coldiretti Campagna Amica and CIA La Spesa in Campagna networks, which were born from the impulse of the local (provincial or regional) departments of these two national-wide farmers’ associations, and still continue to function under their regulation and technical management. A similar process was followed also by the Lucca market, which currently adheres to the Slow Food system but was born as a CIA La Spesa in Campagna market.

In other cases, such as for instance Il Mercatale covered Earth Market and Terra di Prato market, the FM originates from a centralized public initiative, usually by the local municipality together with some other local institution and/or national organizations (e.g., the regional administration, the farmers’ unions or Slow Food), but then emancipates and evolves with time into a more independent market managed by the producers themselves grouped in a formalized association or network, but still benefiting from some support by the originating local municipality or national organization.

Conversely to the previous situation, Fiesole Slow Food market originates from already existing local independent groups of producers or associations, and then decides to join established nation-wide networks. Lastly, the more independent FMs arise from a bottom-up process driven by self-organised local groups of actors (usually producers but also consumers and/or civil society representatives) grouped in a very simple form of association, and still continue to function under their regulations and technical management. That is the case of La Fierucola in Florence and Mercato Contadino di Pisa.

4.2 FMs as a regulated space

The aim of this part of the study is to analyse the rules that govern the functioning of markets by answering the following main questions: are there rules? To what extent are they formalized? What aspects are regulated? What is the process by which the rules are defined?

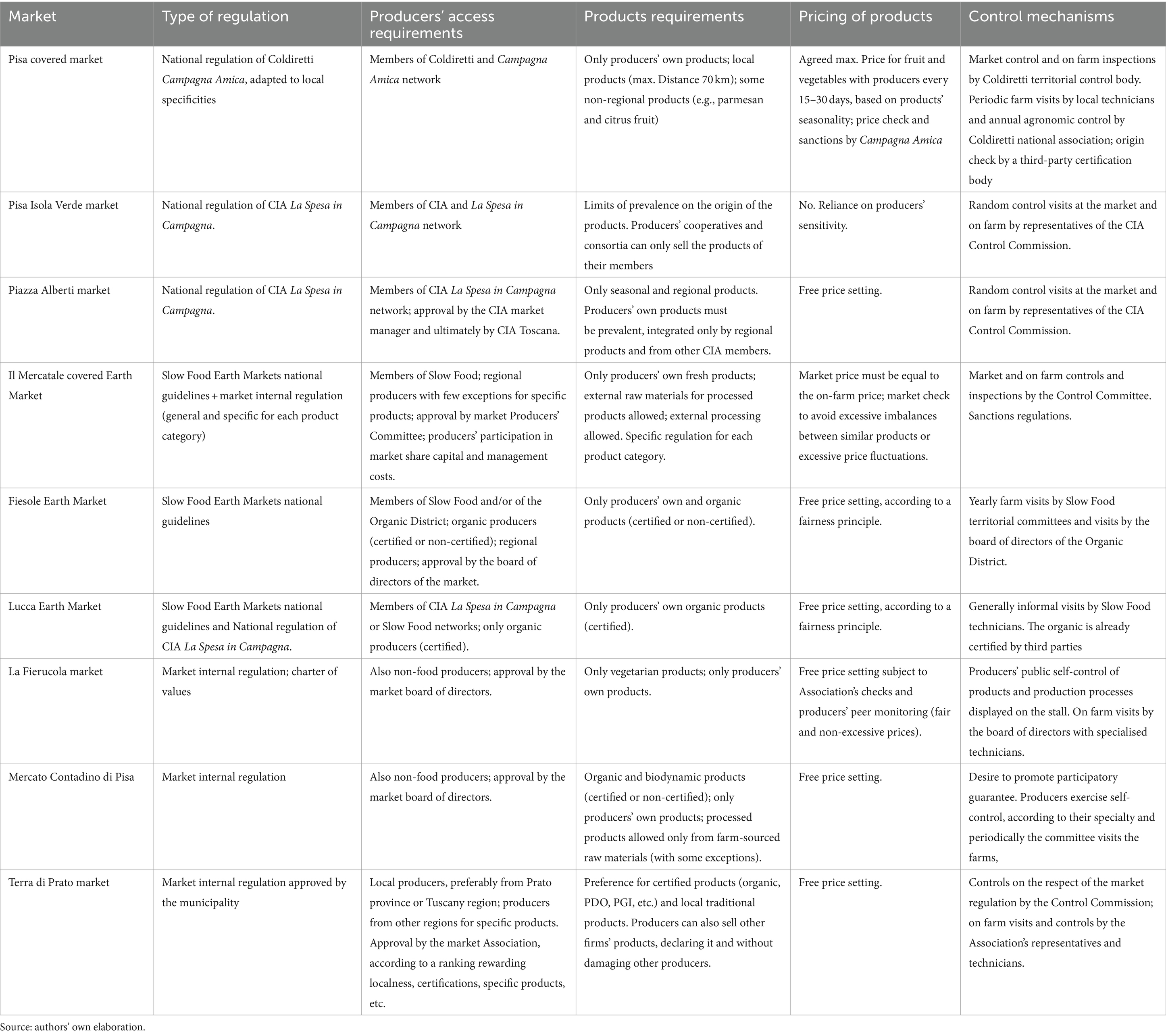

The analysis showed that regulations can concern many different aspects, mainly producers’ access requirements (e.g., food/non-food producers, producers’ provenance, farmers and/or processors, etc.), the quality parameters that the products must comply with (e.g., only organic, raw, processed, etc.), price determination (e.g., free setting, agreed, price caps, etc.), and related control mechanisms (Table 3). Regulations can be more or less formal, bottom up or top-down (defined at more general level, e.g., by farmers unions).

As far as the characteristics of producers and products required to participate in the market and the approval mechanisms through which requirements are assessed are concerned, we pointed out that in the FMs belonging to three nation-wide networks, producers’ membership in the network is an essential requisite, whereas in the independent FMs sometimes producers need to be affiliated with the association managing the market and sometimes the affiliation is not required. An interesting case is the Lucca Earth Market, which is part of both La Spesa in Campagna and the Earth Markets’ networks and is therefore managed by CIA Toscana Nord with the collaboration of Slow Food Lucca, with producers being members of both networks.

Most of the FMs analysed allow the participation of only farmers (not processors nor retailers), which anyway can also sell a part of processed products, such as in Il Mercatale Earth Market, where both external processing of farmers’ own raw materials and internal processing of external raw materials are allowed. In some cases, producers are allowed also to sell others’ products, provided that these products are still local, clearly signalled to consumers and do not damage other producers (Terra di Prato), still originate from producers that are members of the same network/association (CIA Piazza Alberti), or from the same producers’ consortium/cooperative (Pisa Isola Verde). Some FMs also allow non-food producers (La Fierucola and Mercato Contadino di Pisa), while some others restrict participation only to organic producers and products, certified (Lucca Earth Market) and non-certified (Mercato Contadino di Pisa and Fiesole Earth Market). Last, all FMs privilege local producers, usually restricting to or preferring the participation of Tuscan producers, with some exceptions in some cases for specific non-regional producers (e.g., Parmigiano cheese or citrus fruit producers, which cannot be produced in Tuscany). In the case of Terra di Prato, it is interesting to highlight that access to new members is granted according to a real ranking of requests which rewards producers based on localness, certifications (PGI, PDO, organic, etc.) and specificities of products, which tend to favour very local producers offering niche and traditional products. In CIA and Coldiretti FMs, producers and products’ requirements are usually approved by the market manager and, ultimately, the local levels of the networks, whereas in Slow Food and independent FMs new requests are assessed by the management board of the market, which usually involves or at least consults former producers.

Regulations also define the participation of producers in the FM’s management cost, usually fixing a participation fee for each market day that can vary according to the market and to the number or the length of each producers’ market stalls. Sometimes, producers also have to pay an annual membership fee to the market reference organization. The fees are used to pay the market costs (e.g., public space, electricity, etc.) and sometimes the reference associations’ administrative and management costs. An interesting case is Il Mercatale, where producers joining the firms’ network contract (see paragraph 4.4) pay a one-time fee to join the market share capital and in addition participate in the market management costs.

In some cases, regulations also concern the prices that can be applied at the market, setting maximum prices agreed between producers (Pisa covered market), imposing to maintain the same prices applied during on-farm sales (Il Mercatale) or making simple reference to fairness principles, to avoid excessive prices and imbalances between similar products (Slow Food markets, La Fierucola, Pisa Isola Verde). In such cases, price checks are carried out formally by the market management board or the market management association, and informally through producers’ peer-to-peer monitoring.

The provenance and the other products’ characteristics declared by producers are usually checked periodically or randomly both at the market or during on-farm visits, sometimes internally by representatives of the market management board or by specific control commissions appointed by the market association/network, others externally by technicians or certification bodies. In some cases, self-control and collective peer-to-peer monitoring mechanisms are encouraged (La Fierucola, Mercato Contadino di Pisa), although proper forms of participatory guarantee systems are not present.

4.3 External horizontal governance and vertical governance

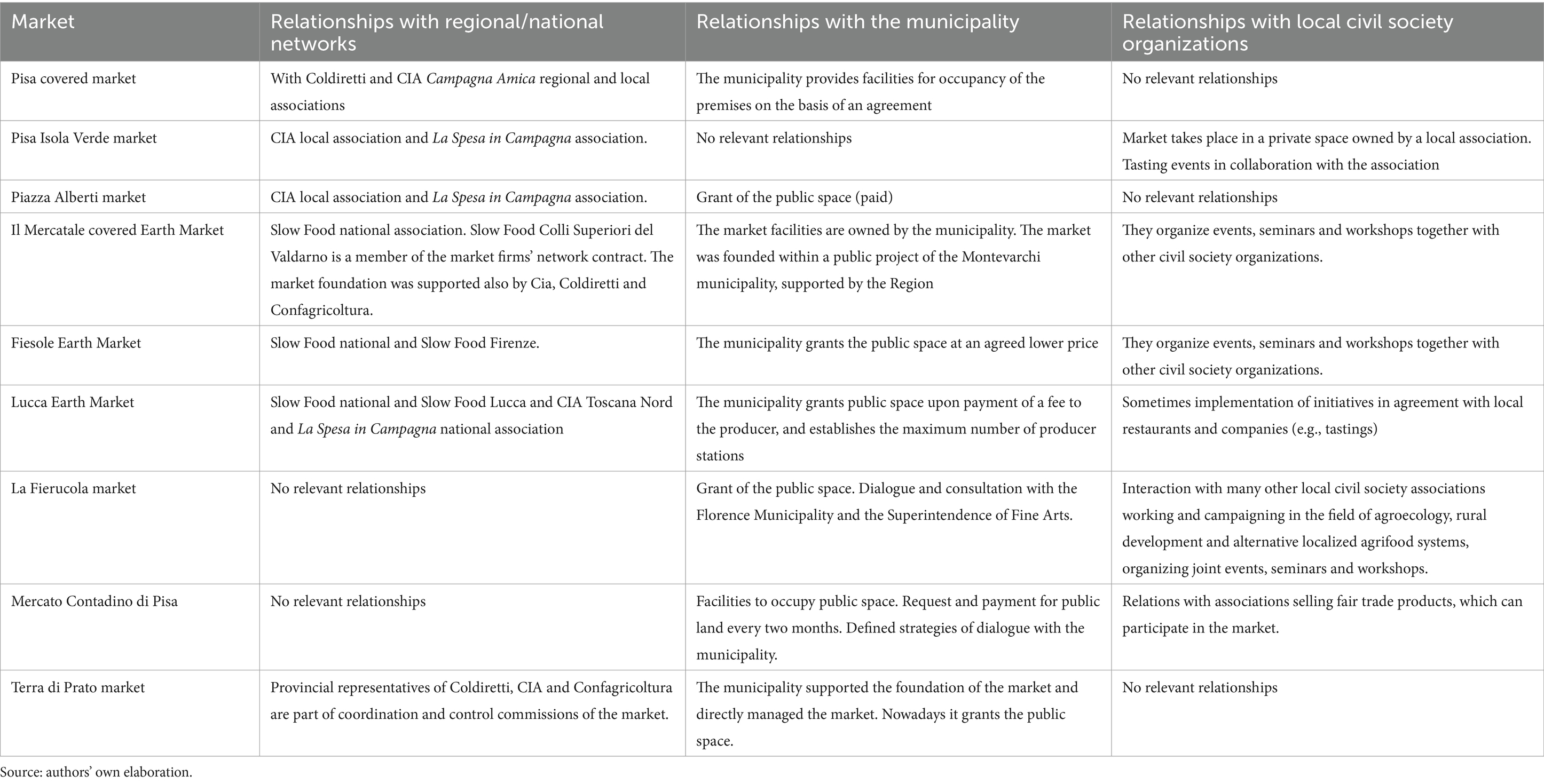

The governance of FMs is characterized as a multilevel process, as shown in the conceptual framework in Figure 1, which includes an internal level within the FM, a level of external horizontal relations between the market and the local context, and a level of external vertical relations between the market and the extra-local context (regional, national, and international).

This section analyses the forms of external horizontal (territorial) and vertical governance established in FMs (Table 4). As it results from the processes of FMs genesis and rules definition, various stakeholders can influence its functioning in different ways. At the territorial horizontal level, FMs have external relationships with the municipality and with civil society organizations, whereas at the vertical level, FMs interact with the regional or national levels of the associations or networks to which they belong.

FMs belonging to the three nation-wide networks have strong relationships with the correspondent national organizations and often adopt their national regulations or guidelines for their own internal functioning. Furthermore, FMs also adopt the operating format, business model and image (e.g., logos and slogans) provided by the networks they belong to, and eventually conform to their own identity.

However, it is interesting to note that the very structure of these networks involves multi-level governance processes, since it is often the local provincial levels, more than the national ones, that directly interact with the organization of the FMs. A particular case is the Lucca Earth Market which belongs to two networks at the same time, the CIA and Slow Food ones, and thus interact with the provincial levels of both organizations. On the other hand, the external relations in independent FMs tend to be more horizontally developed and locally projected, as their associations are set up specifically to manage the market and do not have a multi-level structure.

Table 4 shows how, at the local horizontal level, the presence of relationships with civil society organizations depend on the relational networks developed by territorial dynamizers and promoters (Ton et al., 2014), namely actors able to facilitate processes of sustainable territorial valorisation based on cultural heritage, biodiversity and origin products, through the activation of social and physical capital and resources of a territory (Belletti et al., 2022). Such networks lead to the involvement of volunteerism, the construction of territorial relations, which often allow FMs to organize cultural and knowledge-sharing events (workshops, seminars, etc.) to promote products, practices and values linked to the market itself (organic agriculture, ethical and sustainable food production and consumption, quality products valorisation, etc.). That is the case of Slow Food markets and some independent markets which, thanks to their set of territorial relations, carry on a promotional and cultural role, besides their market functions. Another interesting case is the Pisa Isola Verde market, which benefits from the relationship with a local civil society organization, to hold the market in their physical spaces.

Concerning the external relation with the municipality, for some FMs it is related only to the concession, and in some cases the rent, of public space and the related services (such as supply of water and electricity and cleaning of sales areas), as in the case of FMs belonging to the Farmers’ Unions networks. Belonging to these networks can also facilitate the relationship of FMs with municipal administrations; in fact, CIA and Coldiretti tend to manage these relationships in a centralized manner through their local officials, also by virtue of their contractual power. Instead, more independent markets, as well as markets supported by Slow Food, tend to develop more intense relations and dialogues with the municipality, which sometimes directly have supported the process of their formation. For instance, Il Mercatale and Terra di Prato were both activated within a municipal project publicly funded by the Tuscany Region. As we will see in the next paragraph, sometimes these relations are even more close, and the municipality is directly involved in the internal governance processes of the FMs.

4.4 The internal organization and governance

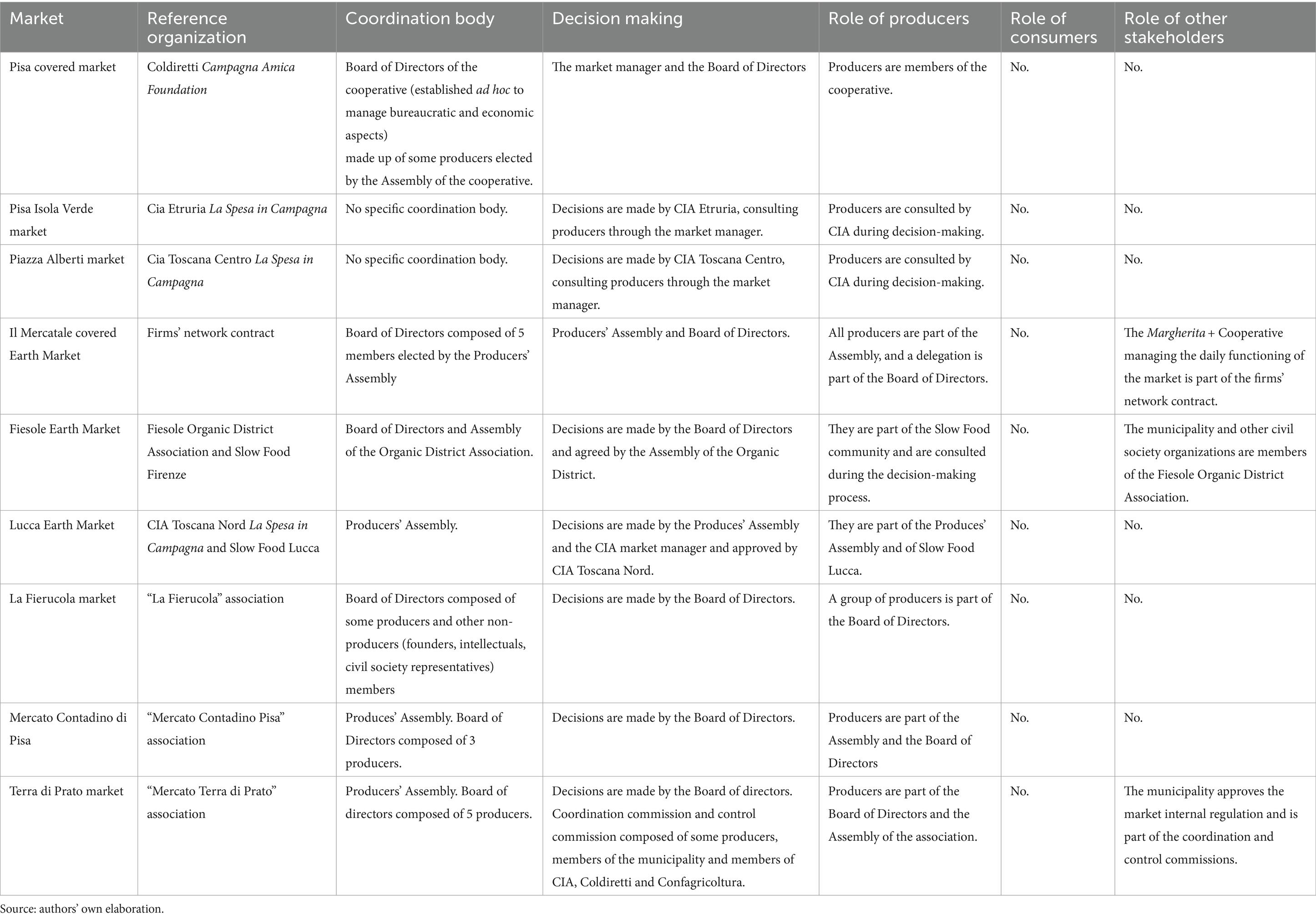

The internal organization of FMs is influenced by the horizontal and vertical governance relations analysed in the previous paragraph, but then each FM develops its internal governance arrangements (Table 5).

FMs belonging to national-wide networks have not a market-specific reference body (i.e., a body that legally represents the FM), whereas independent markets set up a specific association to internally manage the market and interact with other external actors. It is interesting to notice how Slow Food markets are in a hybrid situation. Indeed, besides belonging to the Slow Food network, the Lucca market also belongs to the CIA network, the Fiesole market was activated and is internally managed by the Fiesole Organic District Association, and Il Mercatale set up a firms’ network contract which includes the local Slow Food itself and the social cooperative which manages the market daily functioning.

In most FMs, usually the market operational functioning is supported and supervised by a market manager designated from the reference organization, while decisions are made by a market coordination body, which sometimes also includes some representatives of producers and is usually elected by a larger assembly gathering all the producers. Instead, FMs directly depending on the farmers’ unions, usually do not have a specific coordination body, and decisions are made by the provincial level of the reference organization, consulting producers through the intermediation of the market manager. Two interesting cases are the Pisa covered market and La Fierucola. The former, besides belonging to the Coldiretti Campagna Amica network, established a producers’ cooperative to manage the market, whose coordination body collaborates with Coldiretti representatives in the decision-making process. The latter, instead, includes in its coordination body, together with producers, also local intellectuals and civil society representatives, which took part in the initial activation of the market.

The involvement of the municipality in the internal governance model happens in Fiesole Market and Terra di Prato, where the municipality is a member of the reference organizations managing the markets, making decisions, and in the Prato case, approving the market regulation. This governance arrangement facilitates relations between the FM and local authorities.

Last, concerning the role of consumers in the internal governance, this is something more theoretical than practical, as many of the interviewees referred to it as an ideal aim more than a real ongoing practice. In the Mercato Contadino di Pisa and Lucca Earth Market, the idea of activating a participatory guarantee system actively involving consumers is being discussed, but at the moment this is still not practised, mainly for costs-related issues in terms of time and money. In Il Mercatale, an attempt to integrate consumers into the steering committee was done but failed due to arised conflicts with producers. The representative person of CIA Toscana says that the participation of associations and consumers in a price observatory is allowed, but not in the CIA decision-making bodies. In all the other markets, even if sometimes producers invite consumers to visit their farms, there are no real formal and ongoing efforts to involve them in the market internal governance processes. In general, interviewees give little importance to consumer participation either in quality certification or as members of steering committees.

5 Discussion

5.1 FMs as socially constructed spaces

Our analysis confirms that FMs are not just physical places but first and foremost socially constructed spaces (Smithers et al., 2008; Manser, 2022), whose creation involves the identification, sharing and management of economic and social practices, relations, knowledge and values.

The types of actors involved in FMs that we have identified in the empirical analysis are many and diverse: producers and their associations and syndicates, consumers and their associations, citizens and non-governmental organizations, local public administrations (municipalities). However, as might be expected, farmers and their representative organizations play the most important role. On the other side, while the literature has considered the role of consumers as fundamental for the development of FMs, both as co-creators (Sacchi et al., 2022) and co-managers (Betz and Farmer, 2016), our sample shows instead a very little participation of consumers in the design of FMs, in the strategic planning, and in decision-making. However, citizens are not just mere consumers but stakeholders interested in the environment and sustainability and play an important role in influencing the qualification of products sold, in the definition of some of their characteristics and in the recognition of producers (Muchnik, 2006; Sanz-Cañada et al., 2018; Giacchè and Retière, 2019; Lovatto et al., 2021). Aware of this, some market managers, such as that of the Lucca Earth market, have shown interest in introducing participatory guarantee systems as tools for achieving a higher involvement of consumers in the dynamics of the market, although so far without much success.

5.2 Internal regulation and governance

Our findings support recent literature on FM governance (Betz and Farmer, 2016), according to which the type of actors that gives rise to the FM strongly determines its strategic positioning, which is largely achieved through internal regulation. Through regulation, FMs actors define and share a set of more or less formalized standards and internal rules, in order to align both the supply of products with shared conceptions of product quality, and the behaviour of participating producers with shared conceptions of farming, as to achieve an internal qualification of the market and to limit internal unfair competition. This is not only an issue of marketing, at least for certain types of FMs, but it also expresses the need to affirm producers’ identity and values, in line with Manser’s statement: “Farmers market’s standards and regulations are used to demarcate and draw discursive boundaries around what products and vendors are, and are not, considered authentic and legitimate” (Manser, 2022, p. 156).

Internal qualification is the basis for external qualification, that is the definition of a specific identity of the FM itself, manifested and promoted towards the outside world (consumers, citizens, society at large), in order to differentiate the FM, its products and its “alternativeness” with respect to other more conventional products, markets and distribution channels.

Regulations of the investigated FMs display different characteristics. First of all, the level of formalization of the rules is varied. Written regulations do not always exist in the cases examined, and they are not always easily accessible to consumers or third parties. The content of the regulations also varies. A key aspect is usually the criteria for selecting vendors: the typology of vendors is normally set (i.e., only farmers or only organic farmers), but rarely the regulation outlines the process for vendor application and evaluation, and potential expulsion if they fail to comply with the market rules. Regulations also establish rules that vendors, customers, and other stakeholders must follow, including guidelines on product quality, booth setup and behaviour within the market, while the price level—or the way prices are set—is rarely regulated.

Compliance with internal standards and regulations and conflict resolution mechanisms emerge from our research as an essential part of the internal governance. Indeed, FMs may encounter disputes or conflicts between vendors, customers, or other stakeholders, and governance outlines the procedures for conflict resolution, which may involve mediation, arbitration, or other mechanisms. One of the most critical aspects is to ensure that the vendor produces what sells and does not act as an intermediary. The way to guarantee the origin of products depends on the type of external governance. Thus, for FMs associated with large farmers’ unions, the visit to the plots and the supervision of agronomists within the market, as well as the information displayed by the producer herself, are the appropriate mechanisms to guarantee local, healthy, fresh, and seasonal products, thus maintaining consumers’ confidence. In the case of other types of FMs, Slow Food affiliates base their control on the organization’s own references and territorial networks, but also on the self-control exercised by producers. This can be the best mechanism to override free riders, as for example in case of conflicts between certified organic producers and non-certified agroecological producers. In this case, the mediation and decision-making capacity of the managers is fundamental to maintain the market objectives. As one FM coordinator says, attention must be paid to rumours among producers and consumers. In this respect, networks between different FMs also count. For instance, in the Mercato Contadino Pisa they had the case of some honey sellers who were also in the Fierucola, but when their plot was visited, it was found that they had no production, so they were expelled from both FMs.

Empirical findings show how regulation can be more or less formal and comprehensive, but also collectively agreed or top down prescribed, and originate from stakeholders’ interaction at different governance levels.

5.3 Governance and FM origin and evolution

FM governance processes are influenced by the type of internal rules of each FM. At the same time, the analysis of FMs highlight that the characteristics of internal regulation are the result of vertical and horizontal governance processes.

The way in which the FM is created and its connection with extra-local networks significantly shape both internal and external governance models, both vertically and horizontally. Our analysis has allowed for a number of FMs types to be identified. A first major division is between FMs linked to national networks and “independent” ones. The latter include FMs promoted directly by public authorities and others promoted by spontaneous groups of farmers and local associations.

The first FMs arose from bottom-up processes as pioneering initiatives with an ideological orientation aimed at promoting modes of production and consumption alternative to the dominant models of industrialized agriculture and mass and globalized consumption. This implied a qualification of the market based not only on proximity between the place of production and consumption, but also on production methods (e.g., organic low chemical inputs, artisanal, etc.) and a focus on local breeds and varieties and traditional products. This qualification took place, and still takes place, not so much through formal and codified rules, but rather, based on prior sharing of values and mutual knowledge between producers (and/or consumers) who activated the initiative. The action of non-farmers actors (intellectuals, associations carrying a broad interest such as the environmentalist ones) has been relevant in the history of the Fierucola and the Mercato Contadino di Pisa, inspired by the preservation of organic or biodynamic farming and the links with the local area not only in terms of physical distance, but also of recovery of traditional varieties, breeds and ways of processing. The building of this legacy and prestige of the founders had effects on the definition of their strategies of dialogue with municipalities and on the construction of solidarity economies. In short, the presence of a cohesive group of producers and/or consumers precedes the creation of the FM. The implications for governance are obvious: models of proximity, based on consolidated horizontal relations and direct knowledge, which frequently involve the more or less formalized participation of other stakeholders in the territory or neighbourhood. With the time passing, and with the growth of their success and thus of the number of participants, some of these initiatives formalized their rules more, leading to written regulations (e.g., Fierucola). Today, independent FMs show to develop their own internal regulation, agreed within the market between producers and sometimes other stakeholders, as part of the association managing the market. On the contrary, in FMs originating from a public initiative, as Terra di Prato market, the internal regulation drawn by the FM producers’ association must be then approved by the municipality.

5.4 Role of national networks

In recent times, affiliation to regional and nation-wide networks (i.e., Coldiretti Campagna Amica, Cia La Spesa in Campagna and Slow Food Earth Markets) is one of the most evident phenomenon in the field of FMs. The entry into play of the large national organizations representing farmers (CIA and Coldiretti), and then of consumers’ organizations (Slow Food), had several implications. First, it helped FMs to transform into a mass phenomenon, now known and accessible to many consumers and farmers. However, the founding values of FMs have changed somewhat: while physical and organizational proximity remains the key factor, more attention has been given to protecting the income of small producers and the convenience for consumers, the search for the fair price, and the freshness of products (Mengoni et al., 2024).

The most relevant implication of the growing role of FMs networks relates to the way markets are created and the mechanisms of governance. Particularly in the case of CIA and Coldiretti, the creation of a FM, at least in large urban areas, is the result of planning by the local branch of the organization, normally at provincial level. The local organization finds the potential public spaces available for a FM and starts the animation and selection of producers interested in regularly attending the FM in order to assess the potential of both products supply and demand in the area.7 Then the local organization implements the business model developed by the central organization with the objective to homogeneously shape all the FMs of the network with the same organizational and communicational format. As shown in the previous section, FMs belonging to nation-wide networks usually vertically adopt the association’s regulation. Coldiretti, CIA and Slow Food support the emergence and/or the development of FMs and to some extent they guide their decisions and operational behaviour.

However, membership of networks is not a constitutive fact of FMs, and it can also be the result of a development path. Indeed, we examined several cases of FMs already established and operating thanks to the initiative of producers and/or other stakeholders, which at some point decided to join networks, in particular the Slow Food Earth Market network. Joining a network can become a way for FMs to qualify themselves, effective also in terms of communication to consumers, and to reduce bureaucratic and administrative burdens, including transaction costs to homogenize the vendors, aligning them to common standards, and negotiate with local public authorities. FMs created within the Coldiretti, CIA and Slow Food networks benefit from a proven organizational and communicational format, an established and well-known image among the population (e.g., the name and the logo La Spesa in Campagna, the yellow flags and the visual layout that characterize the FMs of Campagna Amica) and the operational support of the local association. For instance, it is the local association that negotiates with the local Municipality to identify and manage the physical location for the market, obtain permits, set up the market and provide all necessary administrative formalities. According to Beckie et al. (2012, p. 333), “horizontal and vertical collaborations [between farmers markets] are resulting in innovative strategies to address challenges of scale, scope, infrastructure, and organizational capacity that are prevalent in alternative food networks.”

5.5 Shaping regulations through the interaction of external and internal governance: multilevel governance models

However, from the observation of the cases, it appears too simplistic to categorise the governance model of FMs belonging to national networks as hetero-directed by external territorial actors and levels. Indeed, empirical findings show that national or regional standards and regulations are frequently at least partly redefined and adapted at the level of the single FM. Market regulations arise from interactions of actors inside the market with both territorial and vertical levels.

The role of external vertical governance is very relevant mainly in markets with an institutional identity shaped by the large farmers’ unions Coldiretti and CIA. These centralized organizations have set up general regulations at national level, also in order to realize homogeneous forms of communication. However, some FMs belonging to La Spesa in Campagna and Campagna Amica networks are allowed to make some minor adjustments to their internal regulations, for example concerning the admission of new members, to adapt them to the territorial contexts, as it is the case of the Pisa Covered Market. This denotes a hybridization between vertical decisions and the horizontality needed by stakeholders within the FM. Anyway, in the FMs that follow a model of centralized decisions from an extra-territorial body, the formalization of procedures in national regulations and the top-down governance are efficient ways of dealing with conflicts between stakeholders. However, on a day-to-day basis, conflicts are resolved with the intervention of the market managers, and only in critical cases they also involve the local committees or managers of the farmers’ unions.

In Slow Food’s FMs, regulations have a more dynamic flow between the central bodies of the organization and the single FM. The flexibility of this type of governance consists in markets adopting the Slow Food philosophy principles of “Buono, pulito e giusto” (good, clean, and fair), and committing to respecting and disseminating them, being then free (as happens for instance in the Mercatale covered Earth market) to also adopt a market internal regulation concerning producers’ admission, sanctions and selling rules for specific products’ categories.

In independent markets, multilevel relationships are largely limited to the municipality and territorial actors. The Fierucola acknowledges the role of the local municipality and its importance for the functioning of the markets. Terra di Prato Market too has a regulation drawn up by the municipality, but it is being reworked at the proposal of the Market’s Board of Directors to regulate some new emerging aspects, such as the participation of peasant businesses outside the surrounding area of Prato.

The above-mentioned forms of governance are neither linear nor fixed. This can be observed in the interrelation of stakeholders in the markets, but also in their evolution under the impulse of producers’ associations, the proactivity of managers, the support of Farmers’ unions, Slow-Food, and municipalities. This combination of stakeholders with flexible and networked schemes can be seen in the Mercatale of Montevarchi, where in order to overcome the work overload for producers to transport their products, set up the stalls and sell daily, a cooperative solution has been developed that allows to have some employees, thus reducing physical producer’s assistance. This represent an innovation that have emerged from the producers and are driven by the promoters of the FMs, both at the level of internal organization and of governance.

To sum up, the regulations of the FMs need to be updated, with better participation of producers and consumers, and a greater training of managers who can rotate in leading positions. Even if they appear outdated, regulations are an important source for characterizing FMs. In the case of large organizations, they impose a top-down relationship with the actions of national farmers’ unions or national or international NGOs such as Slow Food. But they also include the actions carried out from below, from the city and the territory, by farmers and neighbourhood organizations for the installation of FMs.

6 Conclusion

Through a comparative analysis, this study examined the dimensions of FMs governance and the relationships between them. Three main scales of governance were identified. The first concerns internal governance, which consists of the processes aimed at managing the relationships between the actors who actively participate in the FM, the definition of internal rules of operation, and the operational management of the FM itself. External horizontal governance concerns the relationship between the FM and the actors present in the territorial context in which the FM operates (e.g., public institutions, consumers, citizens), while external vertical governance, which links the FM to regional, national and international levels.

In the Italian context, external vertical governance has become increasingly important. Large networks of FMs have become widespread, expressing both the farmers’ interests and citizens’ associations of general interest. Non-local external actors have become more active in the creation of FMs, and purely economic motives have become more important. The spread of large FMs networks responds to many needs of producers: speeding up market formation, simplifying participation mechanisms, reducing transaction costs in the relationships with other actors in the territory, having a known image in relations with public institutions and consumers. This has led to a partial reduction in the scope for territorial and, in particular, internal governance, which is mostly entrusted to managers, while the role of participation is diminishing.

Following Nicol (2020), we may say that national networks ease the way to scaling out of FMs, expanding the geographical reach through replication, and may better contribute to the scaling up of FM model, having higher advocacy power towards the public authorities for institutional change (policy, rules, and laws). At the same time, within national networks scaling deep, that is more related to change in people, relationships, communities and culture, or in short, the “alternativeness” and transformative role of FMs, may lose energy, being more focused on the pure economic aspect of market exchange.

Notwithstanding the limited number of FMs analysed and the focus only on a specific territory, this research provides consistent evidence that FMs simultaneously implement top-down and bottom-up governance systems, involving a plurality of actors intervening in various capacities and with different interests and objectives in the context of local food systems. However, the finding that bottom-up governance models are becoming prevalent and that the space of internal and external territorial governance is shrinking must be discussed carefully, avoiding oversimplifications.

In fact, the research revealed a wide variety of organizational and governance forms in FMs, the characteristics of which are strongly linked to the constituent values and objectives behind the birth of each market. We have observed that in some FMs regulations are shaped through interactions between different external (horizontal and vertical) and internal governance levels, integrating wider external regulations and adapting them to the specific territorial context, or conversely validating internal regulation. This intervention extends to territorial and local contexts, such as the municipality, as well as to broader territorial contexts, such as the region, the country or global organizations. The complexity of interactions suggests that the characteristics of stakeholders, their influence and impact, vary, according to their position of geographical and relational proximity.

Governance has to do with the issue of who takes the lead to coordinate the FM: the vendors, the community, or large organizations (Gantla and Lev, 2015). Each solution has its own advantages and disadvantages. In the vendors’ FM, the management has strong ties to the inside, but weak ties to the community that hosts them. The managers of this type of FM find it difficult to incorporate more activities into the FM and to secure funding, due to the strong commitment to the vendors. In the community-type market, horizontal relationships and community-oriented decisions favour the ability to attract volunteer work from activists and other market actors, lowering transaction costs. However, linkages with producers depend on the incorporation of vendors’ representatives in governance committees. In contrast, FMs as sub-entities of large organizations have the advantage of greater access to finance and better training of managers, but their links with vendors are normally weaker.

As for the role of consumers as stakeholders, results do not allow us to test the influence of consumers as a key stakeholder in the functioning of FMs. The possibility remains open that consumers do not play an important role as attributed to them in the literature. It is also possible that the interactions between stakeholders have created an institutional environment of trust that mitigates the need for consumers participation.

In conclusion, we can state that FMs represent a sign of the more general process of redefinition of the role of the State, the market, and civil society highlighted by numerous scholars in the field of food systems (Lamine et al., 2012; Bui et al., 2016, 2019; Geels, 2019, among others) as they implement forms of multi-level governance in which different productive, institutional and social actors are involved and interact.

According to our findings, we agree that the conjunction of values and an adequate institutional framework are important pillars for the governance of these markets (Manser, 2022) and that adequate internal coordination and multilevel coordination with relevant actors are fundamental for their future.

Generally speaking, our research underlined the important role public authorities can play in supporting FMs, at all governance levels. Indeed, FMs governance models seem more able to involve local actors and other stakeholders and set up new territorial alliances that can contribute to higher levels of food democracy and sovereignty. Therefore, public support to FMs, as well as other initiatives in the frame of SFSCs, can largely contribute to achieving more equitable food systems, easing agroecological transition, and preserving biocultural heritage. In particular, the “independent” FMs should deserve more attention as they appear to be more fragile and need to build stronger networks to benefit from collective services and reduce management costs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GTS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. GTS granted an academic stance at the University of Florence, Department of Economics and Management (DISEI), funded by Programa de Apoyo a la Superación del Personal Académico (PASPA) of the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). For this research the University of Florence has benefited from the support of the COACH project—Collaborative Agri-food Chains: Driving Innovation in Territorial Food Systems and Improving Outcomes for Producers and Consumers (https://coachproject.eu/), European Commission, Coordination and support actions, CALL H2020-RUR-2020-1, Program H2020, Project 101000918.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the managers and the farmers of the nine farmers’ markets included in the sample, who kindly agreed to be interviewed for the aim of this research work. The authors also thank Oscar Jesús Jiménez Hernández for his contribution in the elaboration of the FMs’ map in Figure 2. Last, the authors thank the Programa de Apoyo a la Superación del Personal Académico (PASPA) of the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), and the European Commission Horizon 2020 programme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1401488/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^These publications are the result of a search in the Scopus and Web Of Sciences (WOS) databases through a combination of the following keywords: Farmers Markets, Governance, Management.

2. ^See https://www.regione.toscana.it/-/i-mercati-degli-agricoltori-in-toscana

3. ^See Supplementary Annex for a detailed description of the main characteristics, genesis and evolution of the sample FMs.

4. ^https://www.coldiretti.it/ and https://www.campagnamica.it/

5. ^https://www.cia.it and http://www.laspesaincampagna.it/

6. ^https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/it/cosa-facciamo/mercati-della-terra-slow-food/

7. ^According to the interview with CIA’s regional representative in Tuscany (July 15, 2022): “In general, there must be a minimum number of enterprises that demand it. But before that, there is an animation process that consists of finding a vacancy, and summoning farmers who are available. They are the ones who propose it to the municipality, and the municipality says which places are available.”

References

Atkočiuniene, V., Vaznoniene, G., and Kiaušiene, I. (2022). The role and functions of stakeholders in the development of local food systems: case of Lithuania. European Countryside 14, 511–539. doi: 10.2478/euco-2022-0026

Beckie, M. A., Kennedy, E. H., and Wittman, H. (2012). Scaling up alternative food networks: farmers’ markets and the role of clustering in western Canada. Agric. Hum. Values 29, 333–345. doi: 10.1007/s10460-012-9359-9

Belletti, G., and Marescotti, A. (2013). Potenzialità e limiti delle iniziative di filiera corta. Prog. Nutr. 15, 146–162.

Belletti, G., Ranaboldo, C., Scarpellini, P., Gabellini, S., and Scaramuzzi, S. (2022). “Redes y dinamizacion territorial, factores clave para la valorizacion sostenible e inclusiva del patrimonio biocultural rural: un analisis desde el territorio de Garfagnana (Italia)” in Bio-cultural heritage and communities of practice, participatory processes in territorial development as a multidisciplinary fieldwork, perspectives on rural development, vo6. Ed. L. Bindi , 6:109–138. doi: 10.1285/i26113

Betz, M. E., and Farmer, J. R. (2016). Farmers’ market governance and its role on consumer motives and outcomes. Local Environ. 21, 1420–1434. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2015.1129606

Brinkley, C. (2017). Visualizing the social and geographical embeddedness of local food systems. J. Rural. Stud. 54, 314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.023

Brugha, R., and Varvasovszky, Z. (2000). Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy Plan. 15, 239–246. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.239

Bryant, A., and Charmaz, K. (2007). “Introduction. grounded theory research: methods and practices” in The Sage handbook oy grounded theory. eds. A. Bryant and K. Charmaz (London: Sage), 1–28.

Bui, S., Cardona, A., Lamine, C., and Cerf, M. (2016). Sustainability transitions: insights on processes of niche-regime interaction and regime reconfiguration in agri-food systems. J. Rural. Stud. 48, 92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.10.003

Bui, S., Costa, I., De Schutter, O., Dedeurwaerdere, T., Hudon, M., and Feyereisen, M. (2019). Systemic ethics and inclusive governance: two key prerequisites for sustainability transitions of Agri-food systems. Agric. Hum. Values 36, 277–288. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-09917-2

Chiffoleau, Y. (2009). From politics to cooperation: the dynamics of embeddedness in alternative food supply chains. Sociol. Rural. 49, 218–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2009.00491.x

Coelho de Souza, J., da Silva Pugas, A., Rover, O. J., and Nodari, E. S. (2023). Social innovation networks and agrifood citizenship. The case of Florianópolis area, Santa Catarina / Brazil. J. Rural. Stud. 99, 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.002

Davies, J., Blekking, J., Hannah, C., Zimmer, A., Joshi, N., Anderson, P., et al. (2022). Governance of traditional markets and rural-urban food systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Habitat Int. 127:102620. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102620

Di Iacovo, F., Fonte, M., and Galasso, A. (2014). Agricoltura civica e filiera corta. Nuove pratiche, forme di impresa e relazioni tra produttori e consumatori. Roma, Italy: Coldiretti.

Dunsire, A. (1993). “Modes of governance” in Modern governance. New-government-society interactions. ed. J. Kooiman . First. Reprinted in 1994 ed (London-Thousand Oaks-New Dheli: Sage), 21–34.

Enthoven, L., and Van den Broeck, G. (2021). Promoting food safety in local value chains: the case of vegetables in Vietnam. Sustain. For. 13:6902. doi: 10.3390/su13126902

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., and Wicks, A. (2008). Managing for stakeholders: Survival, reputation, and success. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gantla, S., and Lev, L. (2015). Farmers’ market or farmers market? Examining how market ownership influences conduct and performance. J. Agric. Food Sys. Community Dev. 6, 49–63. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2015.061.005

Geels, F. W. (2019). Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: a review of criticisms and elaborations of the multi-level perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 39, 187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.06.009

Giacchè, G., and Retière, M. (2019). The “promise of difference” of cooperative supermarkets: making quality products accessible through democratic sustainable food chains? Redes 24, 35–48. doi: 10.17058/redes.v24i3.14002

Giménez, G., and Heau Lambert, C. (2014). “El problema de la generalización en los estudios de caso” in La etnografía y el trabajo de campo en las ciencias sociales. ed. C. Oemichen Bazán . Primera ed (México: UNAM-IIA), 347–364.

Hatipoglu, B., and Inelmen, K. (2020). Effective management and governance of slow food’s earth markets as a driver of sustainable consumption and production. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 1970–1988. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1826498

Hinrichs, C. C. (2000). Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rural. Stud. 16, 295–303. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00063-7

Hyland, J. J., and Macken-Walsh, A. (2022). Multi-actor social networks: a social practice approach to understanding food hubs. Sustain. For. 14, e1–e19. doi: 10.3390/su14031894

Jarosz, L. (2008). The city in the country: growing alternative food networks in metropolitan areas. J. Rural. Stud. 24, 231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.10.002

Kebir, L., and Torre, A. (2014). “Geographical proximity and new short supply chains” in Creative industries and innovation in Europe. Concepts, measures and comparative studies. ed. L. Lazzeretti (London: Routledge), 194–211.

Kooiman, J. (1993). Modern governance. New government-society interactions. London–Thousands Oaks–New Delhi: Sage.

Lamine, C., Renting, H., Rossi, A., Wiskerke, J. H., and Brunori, G. (2012). “Agri-food systems and territorial development: innovations, new dynamics and changing governance mechanisms” in Farming systems research into the 21st century: The new dynamic. eds. I. Darnhofer, D. Gibbon, and B. Dedieu (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 229–256.

Loconto, A., Poisot, A. S., and Santacoloma, P. (2016). Innovative markets for sustainable agriculture. How innovations in market institutions encourage sustainable agriculture in developing countries. Rome: FAO-INRA.

Lovatto, A. B., Miranda, D. L. R., Rover, O. J., and Bracagioli Neto, A. (2021). Relacionamento e fidelização entre agricultores e consumidores em grupos de venda direta de alimentos agroecológicos em Florianópolis-SC. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural. 59:e227676. doi: 10.1590/1806-9479.2021.227676

Manser, M. G. (2022). Systematizing authenticity and codifying values: the role of values, standards, and governance at farmers markets. J. Rural. Stud. 96, 154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.10.021

Marsden, T., Banks, J., and Bristow, W. (2000). Food supply chain approaches: exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 40, 424–438. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00158

Martens, K., Rogga, S., Hardner, U., and Piorr, A. (2023). Examining proximity factors in public-private collaboration models for sustainable Agri-food system transformation: a comparative study of two rural communities. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1248124. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1248124

Mengoni, M., Marescotti, A., and Belletti, G. (2024). Farmers’ markets as a sustainable model of producers-consumers relationships: evidence from Italy. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ., n. 1, forthcoming.

Muchnik, J. (2006). Sistemas Agro-alimentarios Localizados: Evolución del Concepto y Diversidad de Situaciones. In Congreso Internacional De La Red Sial – “Alimentación Y Territorios”, 3, 2006, Baeza (Jaén)

Nicol, P. (2020). Pathways to scaling agroecology in the City region: scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep through community-led trade. Sustain. For. 12:7842. doi: 10.3390/su12197842

Ostrom, E. (2014). Más allá de los mercados y los Estados: gobernanza policéntrica de sistemas económicos complejos. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 76, 15–70,

Pasquier Merino, A. G., Torres Salcido, G., Monachon, D. S., and Villatoro Hernández, J. G. (2022). Alternative food networks, social capital, and public policy in Mexico City. Sustain. For. 14:16278. doi: 10.3390/su142316278

Petropoulou, E., Benos, T., Theodorakopoulou, I., Iliopoulos, C., Castellini, A., Xhakollari, V., et al. (2022). Understanding social innovation in short food supply chains: an exploratory analysis. Int. J. Food Stud. 11, SI182–SI195. doi: 10.7455/ijfs/11.SI.2022.a5

Porras, F. (2016). Gobernanza: propuestas, límites y perspectivas. Primera edición. Edn. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora.

Poteete, A. R., Janssen, M., and Ostrom, E. (2010). Working together: Collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.