- 1Section of Sustainability Management in the International Food Industry, Faculty of Organic Agricultural Sciences, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany

- 2Institute of Business Administration for the Agricultural and Food Sector, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Giessen, Germany

- 3Center for Sustainable Food Systems, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Giessen, Germany

Introduction: The food sovereignty concept intends to transform agri-food systems toward justice and sustainability. While the food sovereignty movement advocates economic alternatives, the actors engaged in economic activities and striving for food sovereignty as actors of change remain overlooked. Food sovereignty scholarship and the movement gives several exemplars such as peasants, local farms and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), as well as activities such as local food processing. However, recognition of these exemplars as ‘economic actors’ is rarely explicit, nor are their ‘economic activities’ recognized. Simultaneously, large corporations are criticized for their global market dominance, which has led to generalized negative perceptions of economic actors. This lack of differentiation, along with the absence of a clear conceptualization of Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS), contributes to blind spots. Furthermore, aspects of how EAFS are structured and organized are rarely considered at the organizational level. This has led to limitations, such as in addressing organizational challenges and developing solutions to strengthen and scale EAFS.

Methods: This study aims to conceptualize the diversity of EAFS at the organizational level by identifying patterns in food sovereignty literature. Using thematic analysis within an integrative literature review, we examined 108 publications, including some gray literature.

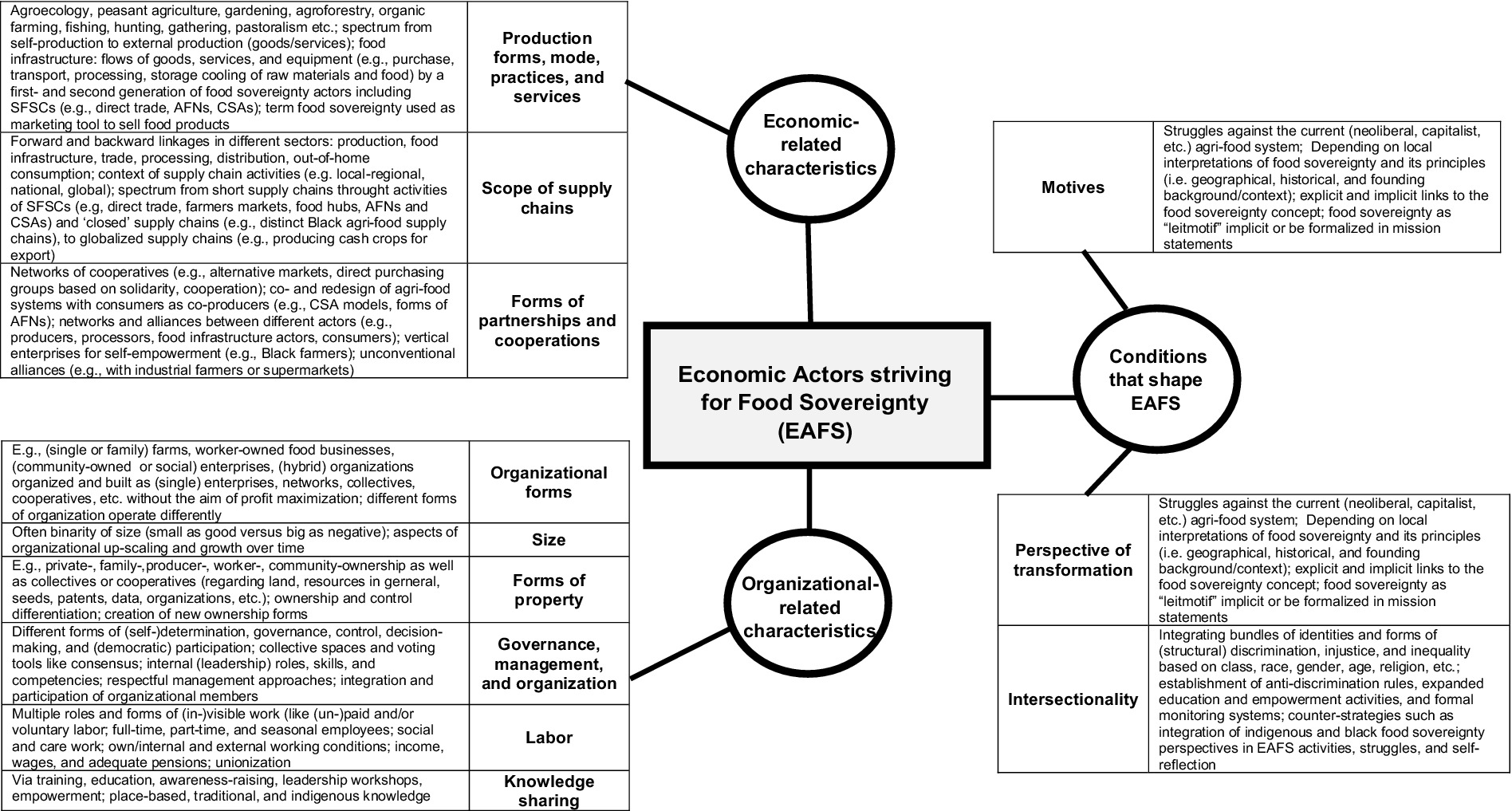

Results: We propose a framework with three main themes: (i) conditions that shape EAFS, including diverse motives, which affect their (ii) economic-related characteristics along the agri-food supply chain, and their (iii) organizational-related characteristics, such as forms of property and decision-making. This framework includes 12 sub-themes each encompassing a wide spectrum of differentiation and options for distinction.

Discussion: It reveals that EAFS combines alternative and conventional elements that differ in their configurations. The economic actor perspective helps to identify a broad set of EAFS and perceive their potentiality to foster new alliances and obtain mutual support. Moreover, this study underscores that food sovereignty is also a multifaceted organizational phenomenon, emphasizing the need for organizational insights to stabilize and expand EAFS. The findings can be used by researchers, practitioners, food movements, and related alternative food concepts such as food democracy, to better understand and develop such concepts and its involved actors.

1 Introduction

In the face of multiple interlinked crises, such as climate change, environmental destruction, social inequalities, and threats to democracy around the world (e.g., Pimbert, 2018; Battilana et al., 2022; Mirzabaev et al., 2023), both socially and ecologically sustainable agri-food systems that are less extractive toward nature and people are being called for (e.g., Hinrichs, 2000; Mars, 2015; Campbell et al., 2017). Against this background, alternative food concepts such as food sovereignty can be seen as a way to transform agri-food systems toward being more just and sustainable (e.g., Anderson et al., 2019; Siegner et al., 2020). A widely cited definition emerged through the Declaration of Nyéléni, developed in 2007 by the global food sovereignty movement at the Nyéléni Forum in Mali_ Food sovereignty is “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (Nyéléni, 2007). While the food sovereignty movement itself is striving for “the establishment of another economic model” (Nyéléni International Steering Committee, 2008, p. 43), and building and practicing economic alternatives, the actors which are engaged in economic activities and striving for food sovereignty, as actors of change, are overlooked in the food sovereignty discourse. This is somewhat surprising as sustainable transitions require an understanding of who the actors involved in driving such changes are (e.g., Fischer and Newig, 2016; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016).

The discourse on food sovereignty is shaped by the contributions of the food sovereignty movement alongside academic scholarship particularly within disciplines such as geography, sociology, rural studies, political economy, and critical agrarian studies (e.g., Binimelis et al., 2014; Anderson, 2018; Dekeyser et al., 2018; Stapleton, 2019a; Pimbert, 2018; Abdoellah et al., 2020; Resler and Hagolani-Albov, 2021). In this context, food sovereignty was conceptualized into various research frameworks, sometimes based on indicators, to assess sustainability of agri-food systems. Examples includes studies from the Global North and Global South with different analytical contexts such as local-regional (e.g., Badal et al., 2011; Binimelis et al., 2014; Vallejo-Rojas et al., 2016; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019; Daye, 2020) and national (e.g., Reardon et al., 2010; Levkoe and Blay-Palmer, 2018) as well as global (e.g., Oteros-Rozas et al., 2019; Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre, 2019). Despite the broad scope of this food sovereignty research, relatively few studies focus on specific food sovereignty actors. For instance, Calvario et al. (2020) analyzed a Basque farmer’s union within the international food sovereignty movement, while Bowness and Wittman (2023) examined a Brazilian non-governmental organization (NGO) involved in food sovereignty mobilization. Other studies have investigated individual actors (Larder et al., 2014; Figueroa, 2015) such as farmers’ perspectives on local food systems in Canada (Beingessner and Fletcher, 2020) or a local food network in Austria (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013). The varied uses of the term ‘actor’ highlight ambiguities in the food sovereignty discourse, a challenge similarly noted in transition studies (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016). Thus, the term ‘actors’ can refer to individual actors (persons as ‘independent’ players or members of an organization) and individual organizational actors (e.g., organizations such as firms, groups, networks) which are able to act (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016). Following this understanding, organizations can be designed by individuals to achieve purposeful collective actions unattainable by any individual (King et al., 2010). These ambiguities concerning actors become evident with regard to the historical origins of food sovereignty. The concept originated from a global grassroots movement driven by small-scale and local peasants and farmers, rural workers, and other marginalized actors in agri-food systems (e.g., Desmarais and Wittman, 2014; Desmarais, 2015; Borras, 2016; Powell and Wittman, 2018). Several examples are mentioned in the food sovereignty literature by scientists and actors from the food sovereignty movement as positive for food sovereignty (Dekeyser et al., 2018), as food sovereignty-conducive (Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019), or as striving for food sovereignty (Carney, 2012; Ajates, 2020; Mestmacher and Braun, 2021). The documentation of the Nyéléni Forum in Mali (full report), published by the Nyéléni International Steering Committee (2008), presents exemplars such as peasants, local farms, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) initiatives, and activities such as local food processing. These examples are also mentioned by Borras et al. (2015), Stapleton (2019b), Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá (2019), and Van Der Ploeg (2020).

However, these actors and their diverse economic activities are rarely named and considered explicitly as ‘economic actors’ or ‘economic activities’, creating blind spots in the discourse. This phenomenon of not naming economic actors (and thus making them invisible) aligns with related research in solidarity and social economies (SSE), where organizational research has shown that actors and “organizations were engaged in economic activity, very few thought of themselves in these terms” (Safri, 2015, p. 931). At the same time, the food sovereignty discourse critiques dominant economic actors such as large corporations that operate in agri-food systems (e.g., Portman, 2018; Pahnke, 2021). This often leads to and supports generalizations in the discourse that portray economic actors negatively (Ayres and Bosia, 2011), criticizing their transformative potential in providing market-based solutions (Fairbairn, 2012), or frame food sovereignty in general as anti-business (Desa and Jia, 2020). In contrast to these negative framings or the lack of consideration of economic actors within the food sovereignty discourse, research about diverse economies has highlighted the existence of a diversity of economic actors engaged in the implementation of non-harmful economic processes (e.g., Gibson-Graham, 20061; Blue et al., 2021).

The lack of differentiation, along with the absence of a conceptualization of Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS), reveals significant blind spots in the food sovereignty discourse. Current research on food sovereignty primarily focuses on agri-food-related production activities (Vallejo-Rojas et al., 2022), offering limited insight into EAFS at the organizational level. For example, there is little understanding of how EAFS are structured and organized, which restricts more nuance in critical examinations such as addressing organizational challenges—and thus the development of solutions to strengthen and scale EAFS. By incorporating organizational perspectives, we draw attention in this study to organizational structures and activities (King et al., 2010) of EAFS thereby enabling a redressing of the (organizational) challenges faced by EAFS. Studies at the organizational level in post-growth economies have already shown that alternative economic organizations are also susceptible to market pressures that can perpetuate inequalities (Banerjee et al., 2021). In addition, these organizational actors are not necessarily without their power hierarchies and their labor relations are not necessarily better (e.g., Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Parker, 2017; Böhm et al., 2020). Similarly, Rosol (2020) calls for a more critical examination of ‘alternativity’ and of the alternative and non-alternative described practices within agri-food systems. This is in line with the call of organizational research to investigate the organizational diversity of actors in agri-food systems; yet analysis of such at an organizational level is still underrepresented but equally necessary for agri-food sustainability transitions (e.g., Watson, 2019; Böhm et al., 2020; Michel, 2020; Moser et al., 2021).

Against these backgrounds, this study investigates the food sovereignty literature (i.e., scientific peer-reviewed publications supplemented by some identified gray literature) to identify patterns that can help conceptualize the diversity of Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS) at the organizational level. The wording striving for food sovereignty is used here, drawing on its usage by scholars (e.g., Carney, 2012; Ajates, 2020; Mestmacher and Braun, 2021), as well as in a similar manner as striving for sustainability (e.g., Schaltegger et al., 2003; Böhm et al., 2020). We introduce the term EAFS here based on related discourses and as an umbrella term to capture their diversity. This term refers to individual organizations and their structures and indirectly includes the individuals involved.

We aim to take one of the first steps toward a deeper understanding of EAFS by identifying recurring patterns in 108 food sovereignty publications from both the Global South and Global North. This is achieved through an integrative literature review and thematic analysis. Based on these patterns and themes, we propose an EAFS framework to guide future research. The following research questions guided our literature review:

1. Which patterns regarding EAFS can be identified in the food sovereignty literature?

2. How can the diversity of EAFS be conceptualized?

Current organizational knowledge on EAFS in the food sovereignty literature is underdeveloped, so our review cannot conclude how these organizations actually operate. However, this study provides the first attempts to structure those patterns that have been identified in relevant publications in a comprehensive way and that merit further investigation. A second limitation of this study relates to organizational theory. One deficit of the food sovereignty literature—the body of research that we analyze—is the insufficient theorization of EAFS as theoretical approaches from organizational studies are rarely applied (see Chapter 3.1). Our study aims to encourage and facilitate both theorization and in-depth empirical research on the organizational level by identifying relevant themes (i.e., related to patterns in the food sovereignty literature) that are relevant for EAFS demanding further theoretical analysis.

To answer the research questions, the article is structured as follows: Chapter 2 introduces the conceptual and theoretical background in more detail. Chapter 3 follows with research methodology for the integrative literature review, including our thematic analysis approach. Chapter 4 provides a detailed literature analysis and presents our EAFS framework based upon three main themes and 12 sub-themes regarding corresponding EAFS characteristics. After the discussion (Chapter 5), we conclude by discussing limitations further research paths, as well as outlining the potential of the presented perspectives and framework for researchers, practitioners, food movement associations, and related alternative food concepts.

2 Conceptual and theoretical background

This chapter explains food sovereignty both as a movement and as a concept and argues for a deeper engagement with economic actors at the organizational level in debates on a food sovereignty-informed agri-food system transformation.

2.1 Food sovereignty as a movement and concept

To better understand the need for a better consideration of the organizational level of economic actors in the discourse on food sovereignty, it is essential to contextualize food sovereignty with its historical origins. Food sovereignty emerged from social struggles and peasant-based fights connected with the global agricultural and food crisis of the last decades, particularly the rural movements of the Global South (e.g., McMichael, 2014; Figueroa, 2015). The term ‘food sovereignty’ apparently first appeared in Mexico. The international peasant movement association La Via Campesina (LVC)2 then launched the concept at the Rome Civil Society Organization Forum in 1996 (Edelman, 2014; see Chapter 1). The food sovereignty concept offers a “different way of thinking about how the world food system could be organized” (Akram-Lodhi, 2013, p. 4), challenging existing structures of corporate power and control in the global agri-food system, and aims to shift power and resources to a new system of production and consumption (Wittman, 2015).

As mentioned in the introduction, food sovereignty is widely cited in the literature and conceptualized into research frameworks in studies both in the Global South and the Global North. In this context, the definition developed by the global food sovereignty movement in the Nyéléni Declaration is used by several scholars (e.g., Schiavoni et al., 2018; Resler and Hagolani-Albov, 2021; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021). The Declaration presents six often-cited pillars of food sovereignty: (I) focus on food for people, (II) value food providers, (III) localize food systems, (IV) put control locally, (V) build knowledge and skills, and (VI) works with nature (Nyéléni International Steering Committee, 2008). However, the term ‘food sovereignty’ is now increasingly used as a marketing instrument by corporations, appearing on food packages sold in conventional supermarkets, which is criticized as greenwashing and co-optation by scholars and the movement (e.g., Fairbairn, 2012; Levkoe and Blay-Palmer, 2018).3

2.2 Incorporating the organizational level into food sovereignty research

EAFS may not always be negatively described in the food sovereignty discourse. In critical organization studies, they are sometimes portrayed as alternative organizations and fighters against neoliberal structures and oppressive work management (Vásquez and Del Fa, 2019; see also introduction), while also being embedded in current agri-food systems through relations of dependency. Thus, EAFS are struggling “to perform in accordance with the principles and aims of food sovereignty” (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013, p. 4,791) and “to organize themselves in ways that are sustainable […], and which avoid assimilation into the dominant global food system” (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013, p. 4,780). Given the lack of a nuanced understanding of EAFS at the organizational level, it is helpful to adopt King et al.’s (2010) suggestion that organizational perspectives should include and focus on the structures and activities of organizations. Accordingly, Ménard (2013) describes organizations as complex arrangements consisting of formal structures (e.g., legal forms), the allocation of property and decision-making rights (e.g., by contracts), and forms of governance (regulating how decisions are being taken) (see also Rosol and Barbosa, 2021 as well as Poças Ribeiro et al., 2021 which specifically address the role of founders, leaders, and managers in alternative food networks (AFNs)). However, there is little consideration of what we name EAFS as a diverse organizational phenomenon (see Ménard, 2017 for an overview of the diversity of organizational arrangements in the agri-food sector). In this sense, we aim to build initial bridges between food sovereignty as a movement and as a concept at the organizational level by focusing on EAFS themselves through the inclusion of organizational perspectives. Such perspectives have the potential to “face or overcome different organizational challenges” (Miralles et al., 2017, p. 834) of these actors, which strategically limit struggles for food sovereignty since individual and organizational actors are always embedded in overarching socio-ecological systems (Muñoz and Cohen, 2017).

3 Research methods

This chapter explains the method selection, data selection process for the integrative literature review, and thematic analysis method used for data analysis and framework building.

3.1 Method selection

We conducted an integrative literature review of food sovereignty studies to circumscribe, differentiate, and better understand EAFS diversity, being “a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic […] such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated” (Torraco, 2005, p. 356). The goal of it is to summarize what is currently known by identifying patterns, themes, and research gaps, thus helping to guide further research (Snyder, 2019). Corresponding to the character of our field of research, we are following an interdisciplinary research approach for a deeper engagement of the organizational level in food sovereignty debates. We are, therefore, articulating different research areas and moving across topics and disciplines of food sovereignty research such as geography, sociology, rural studies, political economy, and critical agrarian studies (see Chapter 1). We do so “in order to increase the chances of cross-fertilization of ideas and theories and unexpected discoveries” (Alvesson and Gabriel, 2013, p. 254). We chose the thematic analysis method by Braun and Clarke (2006) because this method is a widely used qualitative analytic method and is usually adopted when existing theory or research literature on a phenomenon, such as EAFS, is limited. The method provides a detailed analysis of specific aspects of the literature sample (see Chapter 3.2) being guided by our specific research questions (see Chapter 1), rather than a comprehensive description of the entire data sample as, for example, a systematic literature review would have done (Braun and Clarke, 2006; for an overview of review methods see Snyder, 2019). In contrast to methodologies such as grounded theory, the used thematic analysis method is not wedded to any pre-existing theoretical framework, and therefore, the method can be used within different theoretical frameworks (for differences to other methods see Braun and Clarke, 2021). Our approach, therefore, is akin to and takes certain inspiration from grounded theory by acknowledging theorizations that inform existing studies, to generate an original conceptual framework. The thematic analysis approach has the advantage of being able to stimulate theoretical progress in the highly heterogenous field of food sovereignty studies by building on important insights gained through sometimes meticulous empirical work, often being informed (often implicitly, or without sufficiently elaboration) by the use of a diverse and broad range of theories.4 It is difficult to integrate these theories in a way that allows for a better understanding of the potential and limitations of EAFS in agri-food system transformations. Further limitations related to the selection and analysis process are discussed in Chapter 5.5.

3.2 Data selection process for the integrative literature review

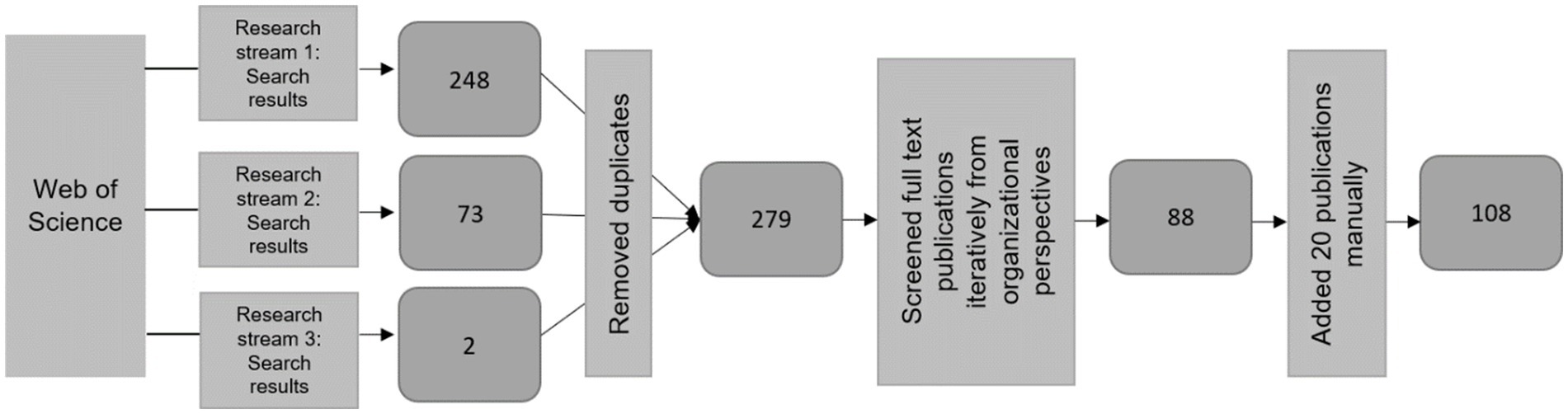

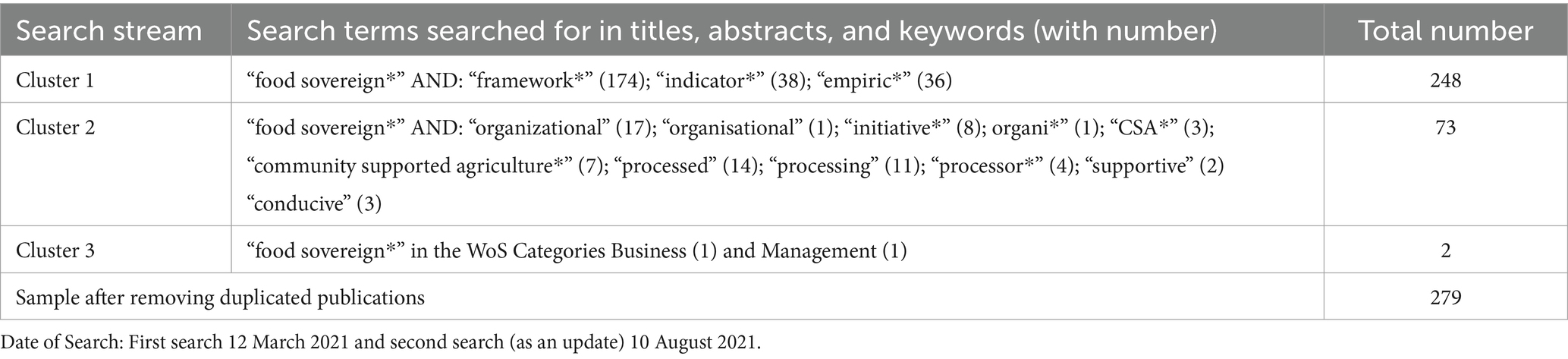

For all searches, we used “food sovereign*” to select relevant scientific peer-reviewed publications, which include both the adjective and the noun “food sovereignty.” Keywords guiding searches within this corpus can be divided into three clusters (see Table 1):

(1) Framework perspective: Food sovereignty is conceptualized in terms of various frameworks to assess sustainability of agri-food systems including pillars, categories, and indicators in (empirical) studies to facilitate analysis. Examples of this include the Global North and Global South with different analytical contexts, such as local-regional, national, and global, and involving different scientific disciplines (see Chapters 1 and 3.1). Frameworks often indirectly mentioned a wide range of economic actors, modes of production, and forms of organization, from which keywords were drawn for (2).

(2) Examples of EAFS: This cluster of keywords includes initiatives along the agri-food supply chain, for example, food processors and forms such as CSA (see examples in Chapter 1).

(3) Business and management: Within the organization, management, and business literature, relevant publications were rarely found. For this reason, we additionally crosschecked the noun “food sovereignty” in the Web of Science database categories “Business” and “Management.”

Table 1. Search clusters and keyword combinations that generated the publications included in the integrative literature review.

Final searches in the online Web of Science database were performed on 10 August 2021, with the three search streams of the clusters previously explained. This process identified a total of 299 publications. In the final sample, 108 publications published between 2010 and 2021 were included in the analysis after the selection process (Figure 1).5 The first step required the removal of duplicates, which left 279 peer-reviewed publications belonging to several research disciplines (n = 279 documents, 10 August 2021, updated review). Titles, abstracts, and full text were scrutinized with an emphasis on organizational information guided by our research questions (see Chapter 1). After having read the full text of all publications, 190 were excluded because they did not match the following criteria: Publications were excluded if they used the food sovereignty term and concept (1) without context (e.g., definition, framework, concrete food sovereignty principles, e.g., references to the Nyéléni Declaration); (2) only as a keyword without being integrated in the text; (3) only as part of the reference list without being integrated in the text. Indigenous6 food sovereignty perspectives were included when publications made explicit links to the food sovereignty concept. During the full-text analysis, an additional 16 publications were identified through reviewing the references listed in the scholarly publications. After having derived the final publication list, we manually added four publications that were already known from previous research and data collection prior to this study. Among these 20 additional publications, some are gray literature, such as project reports or documents published by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which are not indexed in the Web of Science database.7

3.3 Thematic analysis method: data analysis and framework building

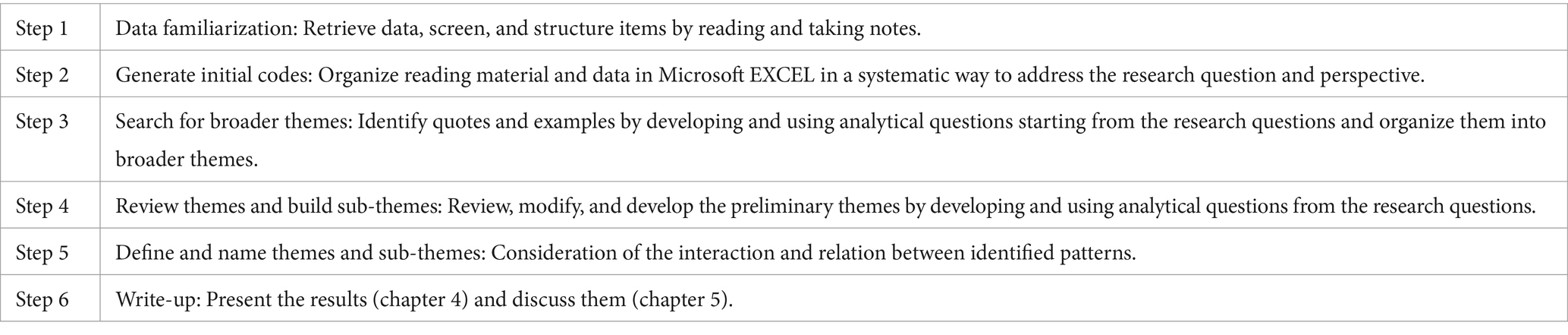

We followed Braun and Clarke’s (2013) and Maguire and Delahunt’s (2017) recommendations and applied the thematic analysis method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns in the form of themes in the data, which were identified as being important to answer our research questions in Chapter 1 and the conceptual-theoretical background regarding the organizational level explained in Chapter 2. This qualitative method combines flexibility and rigor, which is particularly useful for investigating such an under-researched area. Rigor is achieved by a structured step-by-step approach (see the six steps below, summarized in Table 2). Flexibility is achieved by extending the analysis beyond explicit meanings to include the interpretation of latent meanings. For the in-depth review, we reduced the material in several loops and identified patterns (themes and sub-themes) that can help to characterize EAFS. We only considered the 108 publications of the literature sample described above. Other food sovereignty publications were excluded from the analysis to keep the literature selection transparent. The process of the thematic analysis is described by the use of six interrelated steps (see Table 2). Themes and sub-themes (i.e., themes within themes) emerged from the data along these steps.

Table 2. Six-phase framework, based on Braun and Clarke (2006) and Maguire and Delahunt (2017), was used and applied for the thematic analysis in this study (illustration by the authors).

To begin with, we familiarized ourselves with the data by reading the publications, taking notes on possible themes and sub-themes using a review matrix created with Microsoft Excel (step 1).

The 108 publications were sorted by publication year for investigating the historical evolution of the research topic. When reading and screening the full publications, relevant sections were extracted, transferred to the matrix, and categorized by initial codes (step 2).

For the next step, Excel and MAXQDA Version 2020 were used to assist with data management and coding. The results of the coding process were deliberated and agreed upon by both authors. Coding proceeded on two levels: Semantic coding referred to what is explicitly stated in a text, while latent coding was used for capturing implied meanings such as (non-explicit) intentions or assumptions underlying explicit meanings. We developed analytical questions starting from the research questions (see Supplementary material) and searched for broader themes in the review matrix by identifying respective quotes and examples (step 3).

We reviewed, modified, and developed these quotes and examples into preliminary themes and sub-themes according to different levels of abstraction guided by verification questions suggested for the thematic analysis method (for example, see Braun and Clarke, 2013; Maguire and Delahunt, 2017) (step 4).

In the next step, we named the (main) themes and sub-themes. Furthermore, we analyzed in this step how themes and sub-themes interrelated with each other (i.e., interaction and relation between themes and sub-themes) and sorted the sub-themes into the (main) themes. We constructed as a theme (1) conditions that shape EAFS that have three sub-themes (see Chapter 4.1 and Table 3). It reflects generic aspects that affect the other two themes. These are economic-related characteristics of EAFS (theme 2, see Chapter 4.2 and Table 4) and organizational-related characteristics (theme 3, see Chapter 4.3 and Table 5). Theme 2 has three, whereas theme 3 includes six sub-themes. These themes and sub-themes are based on the predominantly descriptive method that we used, condense the aggregated content of the literature, which means that the themes describe patterns in the data that are relevant to the research questions in a synthetic fashion. Following the thematic analysis method, we thus did not address the question of which theoretical perspectives authors had used, not least because of the broad range of relevant EAFS aspects relate in many ways to heterogeneous theories from different disciplines (see Chapter 3.1) (step 5).

We identified a wide spectrum of various patterns that capture EAFS diversity. In total, the information from our sample relevant to answering our research questions was synthesized into 12 sub-themes and three main themes, resulting in a novel framework that may guide future investigations of EAFS (see visualization Figure 2 in Chapter 4). We present the results in Chapter 4 and discuss them in Chapter 5 (step 6).

Figure 2. Framework: Characterizing the diversity of Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS). Visualization of the three main themes (i) conditions that shape EAFS (Chapter 4.1), (ii) economic-related characteristics (Chapter 4.2), and (iii) organizational-related characteristics (Chapter 4.3) (see circles) with 12 related sub-themes and identified patterns (see tables) from the literature sample.

4 Integrative literature review: conceptualization of diverse Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS)

In the following, we present EAFS diversity according to patterns we identified in the literature. Each sub-theme encompasses a spectrum of differentiation and options for distinction which illustrate the diversity of EAFS. As mentioned in Chapter 3, it is possible that themes and sub-themes can interrelate with each other.

4.1 Theme 1: conditions that shape EAFS

The literature addresses three basic conditions that shape EAFS in terms of motives, the perspective of transformation, and intersectionality (also see Table 3). Theme 1 therefore reflects generic aspects that affect Theme 2 and also Theme 3.

4.1.1 Motives

Several studies highlight that activities of EAFS are inspired by a wide range of underlying motives (e.g., Larder et al., 2014; Hoey and Sponseller, 2018; McClintock and Simpson, 2018). James et al. (2021, p. 13–14) found that the struggle against “neoliberal racial capitalism (such as privatization, competition, and rationalization)” unites the motives of both individual organizational actors (EAFS seen as an organization) and individual actors (e.g., founders and leaders of organizations) to establish, manage, and operate EAFS. Other motives identified are concerns over problematic policies, negative effects of the industrial, corporate food system, or a limited public awareness of such aspects (Hoey and Sponseller, 2018). According to one study, food sovereignty related motives “were found in the bigger ideas of why actors supported and initiated” (Clendenning et al., 2016, p. 10) their organization. A single EAFS may often determine food sovereignty as an abstract goal without detailing its meaning or how it should be implemented (see Alberio and Moralli, 2021). However, Di Masso et al. (2014) point out that individual motives, viewpoints, and strategies of EAFS can differ depending on local interpretations of food sovereignty principles, as well as geographical and historical context, such as colonialism. Thereby, the motives of EAFS can be explicitly or implicitly linked to the food sovereignty concept. By explicit motives, EAFS speak the language of food sovereignty and include the term “food sovereignty,” often referencing the Nyéléni Declaration or engage in movements that explicitly refer to food sovereignty. In addition to those EAFS that are aware of the concept, there are others that do not explicitly know and use food sovereignty language. Yet many EAFS “might not be using the language of food sovereignty but are in fact engaged in initiatives that fit within a food sovereignty framework” (Desmarais and Wittman, 2014, p. 5). These apparently implicit EAFS, that are often ‘invisible’ in the food sovereignty discourse, have been studied by various scholars (e.g., Abdoellah et al., 2020; Beingessner and Fletcher, 2020; Ertor-Akyazi, 2020; Robinson, 2021; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021). These EAFS do not necessarily “talk the talk” of food sovereignty in terms of words, but Figueroa (2015, p. 5) argues that they “walked the walk” practically. Naylor (2019, p. 715) describes these EAFS as “outsiders” that “might (or not) advocate or ally with groups working toward food sovereignty.” Although these EAFS do not refer to the term as such, their principles, values, related motives, and corresponding practices are characterized by scholars as being aligned with food sovereignty principles (e.g., Clendenning et al., 2016; Stapleton, 2019a). EAFS can adopt the food sovereignty concept “as a kind of ‘leitmotif’ and try to comply with its basic principles” (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013, p. 4,781). Motives and goals of EAFS may remain implicit in organizational discourse or be formalized in mission statements (e.g., Kato, 2013; Siegner et al., 2020).

4.1.2 Perspective of transformation

EAFS are often described as following transformative approaches that change agri-food systems on a spectrum that ranges from progressive to radical (see Giménez and Annie, 2011 cited by, e.g., Alkon and Mares, 2012, Di Masso et al., 2014, Schiavoni, 2016; see also Pimbert, 2018). A transformational perspective implies the reorganization of production and the reduction of dependency on the market through a range of market- and non-market-based approaches (Larder et al., 2014; Calvário, 2017; Madsen, 2021; Sippel and Larder, 2021). Progressive approaches predominantly focus on practical alternatives, such as initiating local organizations and reforms. In contrast, radical perspectives of transformation aim at destroying the capitalist power structure of the current economic system. Examples in the literature are acts of disobedience, such as circumventing legal constraints or land occupations (e.g., Ayres and Bosia, 2011; Roman-Alcalá, 2015; Calvário, 2017; Pahnke, 2021). Clendenning et al. (2016) provide some context regarding different perspectives on transformation in the U.S. urban food movement where CSAs, urban gardens, and farmers markets do not make explicit links to food sovereignty, but structural similarities to food sovereignty principles are evident. Therefore, Ayres and Bosia (2011, p. 60) interpret the CSA approach in the U.S. context as “microresistance to global agribusiness.” Conceptions of time required for transformative change differ among EAFS as being described in the literature. Duncan and Pascucci (2017) understand agri-food system transition as a longer-term process across two to three generations, whereas radical approaches favor short-term change, in contrast to long-term perspectives connected with progressive approaches (Di Masso and Zografos, 2015). Scholars note that food sovereignty actors are embedded in the current economic system and operate within a neoliberal, growth-orientated environment of a corporate food regime, which affects their perspectives and strategies of transformation (Alkon and Mares, 2012; Larder et al., 2014; Clendenning et al., 2016). They need access to and control over resources (land, water, knowledge, seeds, and other inputs) and enter into various relationships with producers and service providers for credit, implements, tractors, manure and compost fertilizers, fuel, digital technology, etc. (e.g., Ortega-Cerdà and Marta, 2010; Badal et al., 2011; Calix de Dios et al., 2014; First Nations Development Institute, 2014; Pimbert, 2018; Carolan, 2018 Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre, 2019). Due to being embedded in the current system, scholars warn that EAFS runs the risk of also reproducing conventional, capitalist, neoliberal structures, and mechanisms that may include racism and other forms of social exclusion thereby limiting their transformative potency (e.g., Alkon and Mares, 2012; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2018).

4.1.3 Intersectionality

This is emphasized as another condition shaping EAFS. To integrate bundles of identities and possible forms of discrimination in the context of EAFS, several scholars are using an intersectional lens in their food sovereignty studies (e.g., Kato, 2013; Kerr, 2013; Collins, 2019; Calvario et al., 2020) or refer to intersectional approaches (e.g., Fairbairn, 2012; Moragues-Faus and Marsden, 2017). The historical origins of many such organizations indicate multiple, intersecting connections with food sovereignty through the struggles of marginalized and discriminated actors (e.g., peasants, rural and migrant workers, Indigenous people, small- and medium-sized producers, pastoralists, fishers, rural women, and peasant youth). Commonly cited examples include forms of intersectional injustice linked to historical and contemporary colonialism (such as slavery, dispossession, and racism) and interconnected categories of discrimination (such as class, race, gender, age, and religion) within a neoliberal system (e.g., Alkon and Mares, 2012; Kerr, 2013; Vallejo-Rojas et al., 2016; Portman, 2018; Tramel, 2018; Collins, 2019; McCune and Sanchez, 2019; Turner et al., 2020; Sippel and Larder, 2021; Pahnke, 2021). In this context, anti-discrimination rules, expanded education and empowerment activities, and formal monitoring systems are identified as necessary for EAFS to reduce the risk of power abuse and to address intersectional power relations and structures of domination, such as racism, sexism, xenophobia, and other forms of inequality (Iles and de Wit Maywa, 2015). With regard to structural inequality in the forms of racism and class power, Fairbairn (2012) argues for the promotion of intersectional perspectives, particularly so in EAFS in urban areas. As referenced by Kato (2013), many EAFS have yet to address the intersectional nature of power relations, especially regarding whiteness and the positionalities of the middle class, which are particularly relevant for EAFS in the Global North. The integration of Indigenous and Black food sovereignty perspectives in EAFS activities, struggles, and self-reflection are examples of a counter strategy (e.g., First Nations Development Institute, 2014; Taylor, 2018; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021). Further examples are the interlinking of food sovereignty activism and scholarship with a critique of gender inequalities and of violence against women, and a corresponding strategy to ensure equal decision-making power by empowering and advancing women to resist both the patriarchy and neoliberalism, as well as promoting agrarian reform policies that contribute to gender equality (Kerr, 2013; Calix de Dios et al., 2014; Deepak, 2014; De Marco Larrauri et al., 2016; Plahe et al., 2017; Portman, 2018). Although food sovereignty is interpreted by Collins (2019) as a feminist concept in principle, she calls for more attention to further inequalities intersecting with gender relations in control over property in agricultural land.

4.2 Theme 2: economic-related characteristics

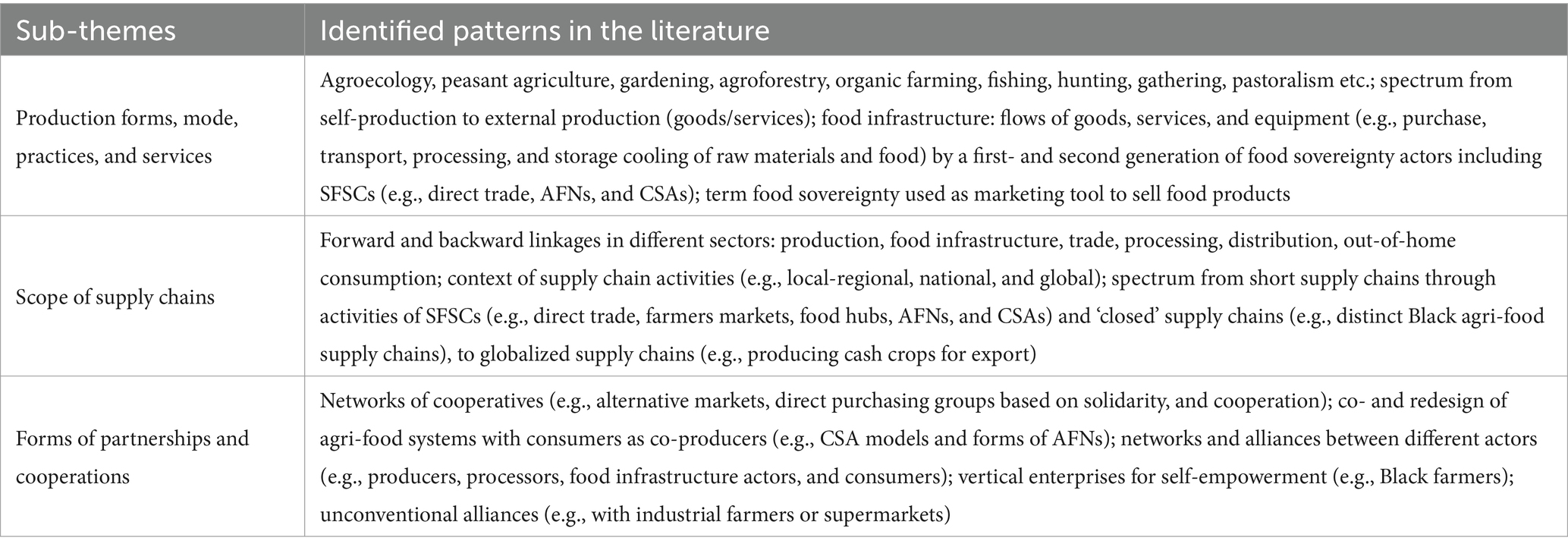

The conditions that shape EAFS (theme 1) affect the second theme economic-related characteristics leads to three sub-themes, production forms, mode, practices, and services, the scope of supply chains, as well as forms of partnerships and cooperations (also see Table 4).

4.2.1 Production forms, mode, practices, and services

The literature contains a diversity of production forms which relate to land and agriculture in terms of agroecology informing the production of seeds, crops, and how to process products, thus being a key building block for food sovereignty (e.g., Reardon et al., 2010; Anderson, 2018; Gliessman et al., 2019; McCune and Sanchez, 2019; Siegner et al., 2020; Resler and Hagolani-Albov, 2021). Some scholars describe peasant agriculture as being close to agroecology, whereas others distinguish between agroecology and a more general peasant mode of production (Soper, 2020; Van Der Ploeg Ploeg, 2020). Other publications refer to agroforestry (Moreno-Calles et al., 2016; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021), organic agriculture (Alberio and Moralli, 2021), the integration of aquatic resources by artisanal fishing, as well as hunting and gathering as production forms, often by Indigenous peoples, rural workers, and migrants (Desmarais and Wittman, 2014; Sonnino et al., 2016; Hoey and Sponseller, 2018; Mills, 2018; Ertor-Akyazi, 2020; Soper, 2020). The mentioned examples can be ascribed to a so-called first generation of food sovereignty actors. In most publications, these small-scale producers, and especially peasants, are described as key actors of a first food sovereignty generation (e.g., Dunford, 2015; Dekeyser et al., 2018; Soper, 2020). This includes peasant farming, gardening, pastoralism, forest-based production, and activities of members of rural landless movements, as well as of other small-scale users of natural resources that are producing food (e.g., Iles and de Wit Maywa, 2015; Hoey and Sponseller, 2018; Pimbert, 2018; Pollans, 2018). The spectrum contains LVC member associations from the Global South and North, such as landless workers’ movements (e.g., Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, MST) (Blesh and Wittman, 2015; Calvario et al., 2020; Sippel and Larder, 2021) as well as peasants, farms with up to 1,200 acres, with employed workers, or fully mechanized farms, and various peasant and movement associations that sometimes pursue conflicting ideologies, identities, and production practices (Giménez and Annie, 2011; Bhattacharya, 2017; Fladvad et al., 2020). The spectrum of forms of production identified in the food sovereignty literature ranges from self-production (e.g., honoring food sovereignty as an everyday practice, especially the contributions of women; see Turner et al., 2020) to production for external use by providing goods and/or services, for example, “organic products for sale” (Levkoe and Blay-Palmer, 2018, p. 73). Food processing is often reduced in the discourse to a critique of capitalist food processing. A recurring argument is that conventional food processing leads to more salty, fatty food (Paddock and Smith, 2018) and is sometimes connected in the literature with food regime terminology such as in “industrially processed ‘food from nowhere’” (Schiavoni, 2016, p. 19). For these reasons, several researchers call for more food infrastructure perspectives in the food sovereignty discourse that can include private, decentralized, or collaborative distribution and processing activities or possibilities that interlink with other EAFS along the supply chain (e.g., Kato, 2013; Borras et al., 2015; Pollans, 2018; Courtheyn, 2018; Hoey and Sponseller, 2018; Anderson, 2018; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Matacena and Corvo, 2020). Food infrastructure enables the flow of goods and services (e.g., purchase, transport, processing, storage, cooling of food, or flows of related equipment) along the supply chain from farms to consumers. For this reason, it is described as a powerful element of food sovereignty and scholars call for more attention to these activities (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Binimelis et al., 2014; Campbell and Veteto, 2015; Leitgeb et al., 2016; Schiavoni et al., 2018; Seminar et al., 2018; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Van Der Ploeg, 2020; Keske, 2021; Levkoe et al., 2021). In some studies, the number of slaughterhouses, businesses milling flour, food hubs, and dairy and non-dairy products are used as indicators for food infrastructures supporting food sovereignty (Vallejo-Rojas et al., 2016; Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre, 2019; Levkoe and Blay-Palmer, 2018). In the context of food production, some EAFS aim to reduce capitalist market dependencies through integration of activities of further types of producers, workers, consumers, and of civil society organizations (e.g., Dekeyser et al., 2018; Mills, 2018). The production activities of these actors, for example, short food supply chain (SFSC) initiatives such as AFNs and CSAs, as well as urban agriculture, community gardening, and artisan food production, have been introduced by De Schutter (2013) as the so-called second food sovereignty generation (e.g., Borras et al., 2015; Gupta, 2015; Clendenning et al., 2016; Al Shamsi et al., 2018; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Matacena and Corvo, 2020; Siegner et al., 2020; Alberio and Moralli, 2021; Sippel and Larder, 2021). A critically mentioned example in the context of production is that some corporations are using the term food sovereignty as a marketing tool to sell food products. Fairbairn (2012) characterizes this as a dilution and cooptation of food sovereignty (see also Alkon and Mares, 2012; Clendenning et al., 2016; Loyer and Knight, 2018; Daye, 2020). One example refers to a corporation that applies an indicator-based food product label that includes a sub-indicator called “food sovereignty” (Jawtusch et al., 2013).

4.2.2 Scope of supply chains

Supply chains cover different sectors which are linked to each other, which is why Lubbock (2020) argues for the inclusion of forward and backward linkages of EAFS along the supply chain. This includes production, various forms of food infrastructure, trade, processing, and distribution facilities, as well as the out-of-home consumption sector (e.g., restaurants, catering, farm-to-school, and farm-to-cafeteria programs), which can include activities of a variety of organizational members (e.g., farmers, workers, technicians, and civil society activists) (e.g., Fairbairn, 2012; Borras et al., 2015; Clendenning et al., 2016; Powell and Wittman, 2018; Al Shamsi et al., 2018; Calvario et al., 2020; Van Der Ploeg, 2020; Sippel and Larder, 2021; Beingessner and Fletcher, 2020; Pye, 2021). The spectrum contains a diversity of supply chain activities in different contexts such as local-regional, national, and global (e.g., Iles and de Wit Maywa, 2015; Roman-Alcalá, 2015; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2018; Oteros-Rozas et al., 2019; Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre, 2019). One often mentioned example are SFSCs like forms of direct trade, for instance, farmers markets and food hubs (e.g., Giménez and Annie, 2011; Laidlaw and Magee, 2016; Hoey and Sponseller, 2018; Alberio and Moralli, 2021; Keske, 2021; Resler and Hagolani-Albov, 2021) as well as other SFSC initiatives such as AFNs and CSAs (e.g., Borras et al., 2015; Gupta, 2015; Clendenning et al., 2016; Al Shamsi et al., 2018; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Matacena and Corvo, 2020; Siegner et al., 2020; Alberio and Moralli, 2021; Sippel and Larder, 2021). Another example are ‘closed’ supply chains that build, for instance, distinct Black agri-food supply chains for Black farmers and other Black supply chain organizations that founded vertical enterprises (Taylor, 2018). In contrast to this, some studies indicate a wide range of spatial relations of food sovereignty initiatives. For example, Soper (2020) analyzed Indigenous peasant producers in Ecuador that organized as a producer cooperative to cultivate cash crops for export and trade them on the world market with consumers in the Global North.

4.2.3 Forms of partnerships and cooperations

Several scholars highlight different cooperation forms of EAFS in view of how to achieve food sovereignty that incorporates different actors. One example is networks of cooperatives which organize alternative markets and coordinate direct purchasing groups based on solidarity and cooperation rather than competition (Koensler, 2020). Another example is the co- and redesign of agri-food systems through new forms of cooperation such as CSA models (as one often cited type of AFNs), where consumers are recurringly referred to as co-producers in respective studies (e.g., Duncan and Pascucci, 2017; Alberio and Moralli, 2021) and the integration of actors traditionally or conventionally being considered “outsiders” to food production and distribution activities (Naylor, 2019). Food infrastructure, which is often organized across the supply chain as networks as a form of cooperation between producers, processors, and consumers, is another example of partnerships and cooperatives (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Borras et al., 2015; Figueroa, 2015; Moragues-Faus, 2016; Dekeyser et al., 2018; Pollans, 2018; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019; Matacena and Corvo, 2020). The case of new rural–urban alliances between different actors, for example, producers and consumers, shows that cooperation can correspond with new organizational structures (Giménez and Annie, 2011; Desmarais and Wittman, 2014; Sippel and Larder, 2021). In speaking about patterns of intersectional approaches to agri-food system transformation, Taylor (2018) it is important to describe a specific economic form as a collective action and thus a vehicle for self-empowerment. For example, Black farmers and other Black supply chain organizations founded vertical enterprises and have thereby built distinct Black agri-food supply chains. The previous examples show that sub-themes can be interrelated. Sometimes, EAFS cooperate with industrialized farmers of the Global North or with supermarkets to increase their impact and to unlock the transformational potential that some food sovereignty actors identify in such unusual arrangements (Claeys, 2012; Larder et al., 2014). Scholars highlight that in building and managing such partnerships between different actors, approaches, interests and goals, and tensions between can occur (Alkon and Mares, 2012; Moragues-Faus, 2016; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2018).

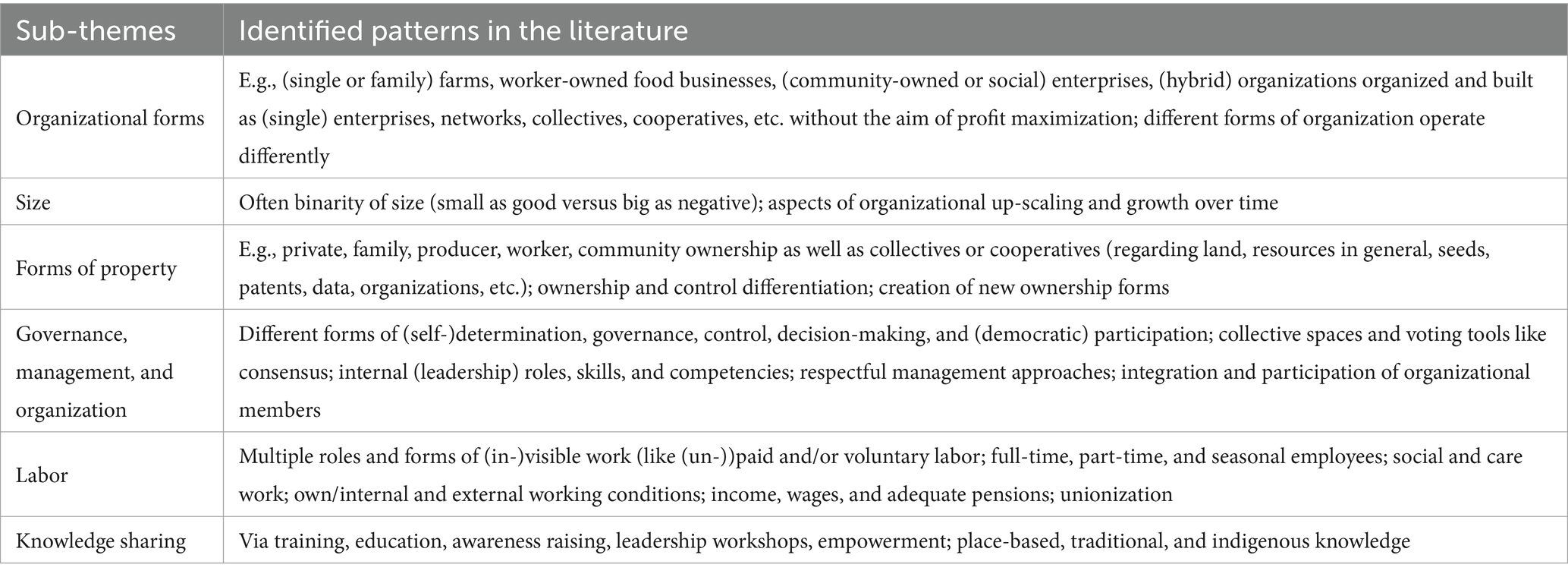

4.3 Theme 3: organizational-related characteristics

The conditions that shape EAFS (theme 1) affect also the third theme organizational-related characteristics leads to six sub-themes, organizational forms, size, property forms, governance, management, and organization, and labor, as well as knowledge sharing (also see Table 5).

4.3.1 Organizational forms

Blue et al. (2021) identify diverse organizational forms using Gibson-Graham’s (2006) concept of diverse economies, highlighting a range of different economic rationalities and ways of engaging in economic activities (as referred to by Moragues-Faus, 2016 and Wittman et al., 2017). Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá (2019) see small-scale, worker-owned food businesses as so-called homologues to the organizational form of peasant and family farms, indicating that these also belong to EAFS (since peasant and family farms are often understood as paradigmatic cases of EAFS, see, e.g., Wittman et al., 2017, Sippel and Larder, 2021). Organizations are established by either producers, consumers, or workers or by a set of different actors (e.g., Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019). Studies distinguish EAFS using notions such as collectives and cooperatives, in general, or, more specifically, producer cooperatives, producer networks, co-ops, and buying groups, as well as community enterprises and community-owned enterprises (Gordon, 2016; Soper, 2020; Keske, 2021; Pahnke, 2021). Others include social enterprises that are described as hybrid organizational forms without the aim of profit maximization (e.g., Desmarais and Wittman, 2014; Figueroa, 2015; Laidlaw and Magee, 2016; Alberio and Moralli, 2021; Machín et al., 2020). McClintock and Simpson (2018) point out that these different forms of organizations may operate quite differently with regard to agri-food system transformation. In addition, scholars highlight that “the six founding principles of [food sovereignty] portray a focus on agrarian rights and food production” and the challenge that “its lack of clarity and contradictions, specifically in terms of its organizational structure and its values, has led to critiques and debates” (Dekeyser et al., 2018, p. 231).

4.3.2 Size

The debate on size is usually focusing on small- to medium-sized local or regional producers such as peasants and farmers or food processors. These EAFS are often framed as being alternative, small, positive, good, or locally embedded as opposed to conventional, big, negative, bad, global, not locally embedded, centralized organizations, such as multinational companies in food processing, distribution, and retailing, as well as large-scale farms (e.g., Alkon and Mares, 2012; Campbell and Veteto, 2015; Moragues-Faus, 2016; Beingessner and Fletcher, 2020; Calvario et al., 2020; Daye, 2020; Alberio and Moralli, 2021; Blue et al., 2021; James et al., 2021). Finding the optimal size for organizations corresponding with diverse and vague food sovereignty principles is mentioned in the food sovereignty literature as a challenge for upscaling and growth (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Noll and Murdock, 2020).

4.3.3 Forms of property

Many scholars such as Blesh and Wittman (2015), Borras et al. (2015), Roman-Alcalá (2015), Shattuck et al. (2015), Leitgeb et al. (2016), Wittman et al. (2017), Taylor (2018), James et al. (2021), and Pahnke (2021) analyze EAFS’ property forms with a focus on land (e.g., land access, governance, use, sovereignty, rights, reforms, and occupations). Land is thereby often related to the historical origins of food sovereignty and related struggles. Some scholars also refer to access to and use of resources in general (Mihesuah, 2017), or seeds, patents, etc. in particular (Kerr, 2013; Campbell and Veteto, 2015). In addition, Carolan (2018) relates food sovereignty and property aspects to digital technology and data control. Blue et al. (2021) advocate for the inclusion of a property perspective along the supply chain in discussions on food sovereignty studies, and Calvário (2017) further extends this to the organizational level of EAFS, stating that most farm holdings are privately owned. With regard to forms of property in the means of production, some forms identified in the literature go beyond traditional or conventional private forms of property (Garcia-Sempere et al., 2019). Examples include land cooperatives, community-owned farms, and land trust organizations that are interpreted as having the potential to challenge private property regimes by replacing them with a community-based mechanism more conducive to food sovereignty and any respective agri-food system change (Wittman et al., 2017). Alternatives that support democratization of agri-food systems, and thus food sovereignty (see discussion above), according to the literature, include producer-owned processing facilities and suitable forms, such as the cooperative, whether created by (family) farmers or (farm) workers (e.g., Taylor, 2018; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Soper, 2020; Pahnke, 2021). Hoey and Sponseller (2018) argue that creating new business models and establishing new EAFS could potentially undermine the general property concentration in agri-food systems. Questions relevant for the assessment of these issues are included in the practical toolkit of the First Nations Development Institute (2014).8

4.3.4 Governance, management, and organization

Food sovereignty is grounded in concepts of self-determination and self-governance (Ertor-Akyazi, 2020; Noll and Murdock, 2020). Regarding economic decision-making, the aspect of democratic control is often emphasized in the discourse in opposition to traditional hierarchical understandings of how to organize food production and distribution (e.g., Alberio and Moralli, 2021). Pahnke (2021, p. 381) highlights the aspect of control in and over the organization in general and that it is often “unclear if claiming ownership is the same as taking control. Moreover, what kind of ownership, or control, is being encouraged? Collective, individual, or perhaps both?” (see also Taylor, 2018). Food sovereignty literature concerning decision-making and organizational governance often ignores internal organization and its actors (e.g., Reardon et al., 2010; Badal et al., 2011; Dekeyser et al., 2018; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021; Pye, 2021). Actors within an EAFS can be a board of directors or specific types of organizational members, such as workers (e.g., Kato, 2013; Wittman et al., 2017; Stapleton, 2019a; Machín et al., 2020). Governing for food sovereignty at the organizational level includes, for Resler and Hagolani-Albov (2021), a respectful management approach practicing autonomy and democracy (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020). Some EAFS provide and foster opportunities for such self-organization and participation by organizing collective spaces for members to engage in discussion and exchange (Calvário, 2017; Porcuna-Ferrer et al., 2020). Moragues-Faus (2016) mentioned decentralization, participatory, and non-hierarchical organization as characteristics of food co-ops and buying groups distinguishing them from traditional and conventional organizations operating in food distribution. Some EAFS use specific decision-making techniques such as radical democracy and consensus-oriented forms of deliberation (e.g., Roman-Alcalá, 2015; Moragues-Faus, 2016; Vallejo-Rojas et al., 2016; Duncan and Pascucci, 2017; Gallegos-Riofrio et al., 2021). According to Porcuna-Ferrer et al. (2020), the appropriate organizational and leadership skills of organizational members and their positive effects can promote organizational stability.

4.3.5 Labor

This sub-theme includes a spectrum of diverse forms of labor across agri-food supply chains done by peasants and farmers (e.g., preparation of agricultural inputs, post-harvesting, food processing, and distribution) (e.g., Seminar et al., 2018; Pye, 2021), by workers (e.g., rural, landless, migrant, and undocumented) in production on farms, in horticulture, plantations, or aquaculture, as well as in food transportation, storage, processing, manufacturing, service, wholesale, and cooking (Borras et al., 2015; Laidlaw and Magee, 2016; Moragues-Faus and Marsden, 2017; Levkoe and Blay-Palmer, 2018; Stapleton, 2019a; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Van Der Ploeg, 2020; Pye, 2021). In the context of labor, research addresses how to connect EAFS with unions and the need for critical approaches to labor relations within EAFS (Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Calvario et al., 2020; Korsunsky, 2020). Some food sovereignty researchers investigating, for example, EAFS labor relations consider historical and current forms of feudal, slave, and child labor (Deepak, 2014; Larder et al., 2014). A recurrent point is that predominantly white, affluent food movements pay less attention to labor and migration relations than non-white social ones (Korsunsky, 2020; Sunam and Adhikari, 2016). In addition, literature also includes discussions about wage labor in general, addressing topic such as working conditions, income, and pensions (e.g., Alkon and Mares, 2012; Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Deepak, 2014; Scialabba, 2014; Iles and de Wit Maywa, 2015; Gliessman et al., 2019; Korsunsky, 2020; Pye, 2021), as well as policy proposals, including minimum income, the fair sharing of jobs, and disparities in free time between men and women (Calix de Dios et al., 2014; Pimbert, 2018).

4.3.6 Knowledge sharing

This can occur through training, education, awareness raising, and leadership workshops, particularly through empowerment of women. It is frequently highlighted in the food sovereignty literature as an important factor in making the transformation of agri-food systems relevant for qualified work in food production and distribution of EAFS (Deepak, 2014; Campbell and Veteto, 2015; McCune and Sanchez, 2019). According to Fairbairn (2012), food sovereignty should not be reduced to educating individuals since this could depoliticize actors, potentially weakening the food sovereignty movement (Clendenning et al., 2016). Place-based, traditional, and indigenous knowledge of seeds, agricultural processes, preparation and preservation of foods, healthy nutrition, hygiene aspects, and decision-making are mentioned by a number of authors as being supportive of food sovereignty and of empowering both individuals and organizations (Lutz and Schachinger, 2013; Calix de Dios et al., 2014; Gupta, 2015; Plahe et al., 2017; Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá, 2019; Machín et al., 2020).

Our findings regarding the three themes and 12 sub-themes of EAFS are a first step toward building a more comprehensive conceptual framework for understanding the diversity of EAFS at the organizational level. Our primary focus here is on thematic analysis, acknowledging a generic theoretical underpinning as explained in Chapter 2, without delving into proper theory building or conceptualization. Thus, Figure 2 provides an overview of the themes and sub-themes. Theme 1 represents overarching aspects that affect both theme 2 and theme 3, thereby laying the basis for the discussion of our findings in the following chapter. In addition, see Supplementary Table S1 for illustrating the diversity of EAFS in descriptive terms.

5 Discussion

Despite the character of our investigation of the food sovereignty literature, some analytical conclusions and hypotheses can be drawn from our initial framework. We discuss the findings below and conclude this chapter with limitations and implications for further research.

5.1 Incorporation of different generations of EAFS along the agri-food supply chain

Incorporating organizational perspectives in this study is understood to mean paying attention to what we conceptualize as Economic Actors striving for Food Sovereignty (EAFS) which are able to act. This study confirms that attributes of EAFS are mentioned explicitly and implicitly in the food sovereignty literature, but a comprehensive overview and conceptualization of those organizational actors is thus far missing. This is somewhat surprising given that the food sovereignty movement itself presented an action agenda for an alternative economic model which is outlined, for instance, in the documentation of the Nyéléni Forum in Mali by the Nyéléni International Steering Committee (2008). This documentation (full report of the Forum) includes various economic actors that are covered by our presented EAFS conceptualization; however, this publication is rarely cited in the discourse (exceptions are, for instance, Blue et al., 2021 and Seminar et al., 2018). The food sovereignty concept aims to transform agri-food systems toward justice and sustainability, yet the literature often overlooks an economic actor perspective of the role of EAFS as actors of change who are engaged in enacting, driving, or contesting transitions. This oversight may be due to the critical stance toward economic actors prevalent in the food sovereignty discourse. In contrast, related discourses on themes such as diverse economies and SSE highlight the importance of recognizing and understanding these actors’ diversity and provide more differentiated perspectives (Gibson-Graham, 2008; Zanoni et al., 2017).

In this study, this oversight is contrasted with a developed EAFS framework that offers a conceptual language for EAFS, illustrating the existence and the diversity of this group of actors. Our findings indicate that the diversity of EAFS originates from two different food sovereignty generations. One explanation for the under-representation of EAFS, in particular regarding the scope of agri-food supply chains, might be the historical origins of the movement that focused on primary producers of the first food sovereignty generation (i.e., peasants, farmers, and rural workers). Consequently, supply chain actors, for example, food processors, have often been overlooked in the discourse, despite the food sovereignty movement’s stated aim of transforming agri-food systems. The focus on primary sector actors and related production activities, and the omission of an explicitly addressed supply chain perspective may stem from associations with corporations in general or with food processing, both often negatively generalized. This aligns with research gaps identified in agri-food sustainability transitions, where food processing and distribution (see framework theme 2 in Chapter 4.2) are underrepresented in research (see El Bilali, 2019 and suggestions for further research). Making visible the diversity of EAFS along the supply chain has the potential to foster (new) forms of partnerships and cooperations between EAFS.

5.2 Motives of striving for food sovereignty with varying strengths and conflicting goals

Most EAFS share a general motive to transform agri-food systems toward justice and sustainability (see framework theme 1 in Chapter 4.1). Our findings show that what can be termed ‘explicit EAFS’, familiar with the term and concept of food sovereignty, and ‘implicit EAFS’, not directly using the terminology, both exist and contribute to this diversity. This finding supports Shattuck et al. (2015) and Figueroa (2015), who argue that food sovereignty is “happening” and “walking” even if the actors do not directly “talk” the food sovereignty language in terms of words. Their motives include raising awareness of societal and environmental issues, and making practical changes in food production and distribution (see theme 2). In addition, the conditions that shape EAFS can not only affect economic-related characteristics along the agri-food supply chain but also involve the reconfiguration of organizational aspects, such as organizational structures and ways of organizing (see organizational-related characteristics in theme 3 in Chapter 4.3). In contrast to other discourses, organizational perspectives are more prominent in, for example, SSE research than in the food sovereignty literature analyzed in this study (see, for example, Calvario et al., 2020, Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020, Alberio and Moralli, 2021). Each sub-theme of the developed EAFS framework contains a broad spectrum of possibilities for differentiation and options for distinction. Therefore, the framework illustrates that the food sovereignty concept suffers from some inconsistencies and generalizations. For example, some EAFS oppose capitalist food system structures or try to reduce their involvement in them by, for instance, establishing direct (trade) relations (sub-theme forms of partnerships and cooperations), while others remain embedded in the (international) capitalist market and build alliances (at least partially) with capitalist and other conventional agri-food system actors (see example of EAFS, more precisely small farmers which are part of the MST movement, selling in order to survive economically organic products to a French multinational company, by Böhm et al. (2016), as well as Soper, 2020 in framework theme 2).

Another example where the food sovereignty concept suffers from some inconsistencies and generalizations is that the support for family peasant farming, gender equality, and collective rights often does not critically question the traditional model of family farms and property relations (Collins, 2019). The food sovereignty discourse frequently addresses gender in binary terms of “men and women” (see Ruiz-Almeida and Rivera-Ferre, 2019), neglecting not only the distinction between sex, gender, and sexuality but also the diversity within these constructions. Further food sovereignty studies could shift the attention from the production of (traditional) gender roles to the making and unmaking of binary gender (see Pfammatter and Jongerden, 2023 for de- and re-constructions of gender and farming identities by queer farmers). Thus, it seems that some of the identified examples contradict principles of food sovereignty. Including intersectional perspectives (see theme 1) can provide a more nuanced analysis of how diverse EAFS are structured, organized, and operated (see, e.g., the study of Von Redecker and Herzig, 2020 for the inclusion of intersectional and queer-feminist perspectives in the context of LVC). Our study thus facilitates to balance the investigation of sometimes conflicting food sovereignty goals and principles regarding economic-related activities, organizational-related characteristics, etc.

5.3 Need for connecting themes instead of isolating alterity

By incorporating organizational perspectives, we draw attention not only to economic-related characteristics but also to organizational-related characteristics that can be also very diverse and cover a broad spectrum. The findings of this study indicate that food sovereignty literature so far rarely connects with or shows differentiation of economic-related (framework theme 2) and organizational-related characteristics (theme 3) (also see Tables 3–5, and framework in Figure 2). These themes are often viewed through one of two lenses: “alternative” (and then associated with normative or generalized analytical claims, e.g., good, positive, small, local, non-capitalist, non-market-based, democratic, and non-hierarchical), against “conventional” or “mainstream” (associated in opposite ways with, e.g., being bad, negative, big, global, capitalist, market-based, non-democratic, and hierarchical). These lenses do not always prove analytically useful (e.g., Renting et al., 2012; Larder et al., 2014; Cruz and van de Fliert, 2023). For instance, an EAFS might have non-capitalist economic-related characteristics but maintain hierarchical organizational forms. The diverse configuration options of CSAs illustrate this point. The alternative production-distribution model of a CSA (see theme 2) can be organized and owned as a community farm with democratic management (see sub-theme property forms in theme 3), or organized and owned by a single farmer (Grenzdörffer et al., 2022; see also Wittman et al., 2017 about cooperative land ownership as pathway toward food sovereignty).

Such differences may impact transformative potentials and the ability of EAFS to reproduce under market conditions, which is why generalizations about so called “alternative” production systems (e.g., small-scale peasant agriculture, agroecological production, CSA model), alternative organizational forms (e.g., cooperative ownership), or alternative organizational governance (e.g., collective decision-making), which are often associated with food sovereignty and its principles, may often impede the differentiation in views (e.g., Beingessner and Fletcher, 2020; Korsunsky, 2020; Soper, 2020; Pye, 2021). Research has shown that organizations being labeled “alternative” can also engage in social exclusion or prioritize profit over sustainability, similar to “conventional” organizations (e.g., Slocum, 2007; Nesterova, 2021). Therefore, food sovereignty scholars (e.g., Clendenning et al., 2016; Borras, 2016; Korsunsky, 2020) and AFN research (e.g., Rosol, 2020) advocate for critical views on alterity. This is consistent with organizational research that supports nuanced views, recognizing that hierarchical structures within EAFS can sometimes be useful or necessary, depending on the context (Parker, 2021). Although EAFS are often framed as being alternative organizations, they may combine different features in very specific ways that defy a precise location on a single gradient of a degree of alterity. To properly analyze and assess alterity, it seems useful to look at each theme and sub-theme individually. We thus agree with Parker et al. (2014) that the interrelations of various aspects of EAFS must be analyzed (see, for example, MST farmers mentioned above). Future studies should avoid viewing alterity in isolation and instead understand EAFS as products of multiple, often hybrid or contradictory practices.

5.4 Organizational level to incorporate challenges of and within EAFS

Our analysis revealed dilemmas of EAFS that can lead to challenges regarding agri-food system transformation. For instance, EAFS are embedded in socio-economic structures intersecting various power relations, shaping their operations, obstacles, and solutions. While food sovereignty literature focuses on different analytical contexts (local-regional, national, and global), it often overlooks EAFS, crucial for driving change, at the organizational level. This overlooking of organizational challenges can thwart food sovereignty activism and undermine its goals. This bias also undermines goals of social inclusion and empowerment since EAFS are often established, managed, and operated by severely marginalized groups (see framework theme 1). They have a hard time even keeping their organizations functional, with few resources left for strategic thinking or developing replicable solutions for the challenges that might help support other EAFS by strengthening their transformative impact. This challenge is poignantly expressed by alternative food movement research in which a cited practitioner describes it as follows: “It’s hard to be strategic when your hair is on fire” (Hoey and Sponseller, 2018, p. 606).

If EAFS are unstable and cannot sustain, scale, or multiply in the long term, agri-food system transformation is unlikely to happen. Research has a responsibility to support resource-limited EAFS in developing solutions to their challenges. Including organizational perspectives from related fields can help better analyze EAFS and develop counterstrategies to the challenges that question their reproduction and promotion. Based on this, we argue that detailed investigations of concrete organizational practices, including management approaches, are needed to ensure and increase their organizational stability (see framework theme 3). However, there is so far a notable gap between food sovereignty literature and critical management and critical organization studies, despite both approaches challenging capitalist, neoliberal, and patriarchal systems as well as advocating for alternatives to them (e.g., Alvesson et al., 2009; Grey and Willmott, 2010).

As our study has shown, property aspects and relations are rarely explicitly addressed and are not a focus in the food sovereignty literature. Where mentioned, it is typically limited to land issues. Therefore, we argue more attention be paid to examining property relations at the organizational level of EAFS, particularly in relation to who is actually in control of the means of production within economic actors in general but also of EAFS in particular. In this context, we call for overcoming simplistic claims that being “alternative” is, for instance, inherently transformative, gender sensitive, and socially inclusive (see Chapter 5.3 above). Furthermore, property relations that partly deviate from or are in conflict with (Western) private property should be explicitly investigated. EAFS might provide an interesting case for organizational studies, reflecting the assertion made by Peredo et al. (2022) that the problems of our time should not be addressed solely through so-called Western knowledge and that scholarship, especially in management and organization studies, should adopt decolonial perspectives. Considering the diversity of property relations identified in the food sovereignty literature on EAFS (see theme 3), the complexity of these relations should be analyzed in view of social-ecological transformations (Grenzdörffer et al., 2022). Bencherki and Bourgoin (2019), for example, highlight that property is at the heart of organizations and labor relations, but even organizational scholars rarely discuss these issues. Our findings also indicate that labor relations in EAFS are underdeveloped, despite the “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas” considering peasant farmers and rural workers as equals (Van Der Ploeg, 2020).

Following Parker’s (2021) assertion that we do not know which forms of organization work best in particular contexts, we conclude that the food sovereignty movement should focus more on the diversity of EAFS from organizational perspectives. This could be achieved by integrating relevant organizational knowledge, for example, into the curricula of existing “Agroecology Schools” that follow food sovereignty principles (for such schools, see McCune and Sanchez, 2019; Garcia-Sempere et al., 2018; for “Schools for Organizing” see Parker, 2021). This is especially so because small- and medium-sized organizations often need external support for organizational learning (Braun et al., 2022). We, as authors of this study, collaborated in previous projects with various food sovereignty movement associations, as well as EAFS. Therefore, we have tried to align our research with the awareness of research by Nyéléni Germany, which states that research should contribute to more food sovereignty9. We argue that our approach has the potential to facilitate this.

5.5 Limitations and implications for further research

Our thematic analysis of an integrative literature review offers a detailed examination of specific aspects of food sovereignty literature rather than a comprehensive description of the entire data sample as it would be in a systematic literature review. The inclusion of additional keywords could lead, for example, to the identification of further publications. Since the literature search was conducted in August 2021, more recent publications are not included in the sample, although current literature is referenced in other chapters. Thematic analysis is chosen for its suitability where existing theories or research on a phenomenon are limited and is used without relying on a pre-existing theoretical framework. We do not tackle these theoretical backgrounds due to their implicit nature, varying contexts (local-regional, national, global), and insufficient elaboration, particularly concerning EAFS, which require a separate theoretical project with uncertain outcomes. Another limitation is that our study does not provide insights into how EAFS operates due to the limited knowledge about these actors (see also limitations mentioned at the beginning in Chapter 1).