- 1Hamad bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar

- 2Qatar Foundation, Doha, Qatar

This paper delves into Qatar’s evolving food security program, emphasizing the role of state-driven capital in shaping its corporate food regime. Previously, most studies on food regimes centered on corporate dynamics and neoliberal characteristics; the rising influence of state capital, especially in the Gulf region, remains underexplored. Qatar is emerging as a key state player in the global food landscape, contesting the dominance of traditional Northern entities by leveraging significant capital to back agribusiness ventures, foster new trade routes, and drive innovation. The study analyzes Qatar Food Security strategies to unpack the interplay between state-driven capitalism, agro-security mercantilism, and agribusiness’s role within the corporate food regime. This study employs a multiple case study methodology on organizations, initiatives, and strategies that have been instrumental to Qatar’s food security response during and after the 2017 economic blockade. The paper concludes that Qatar secures food security through a multifaceted strategy that leverages domestic production, international investments, private sector engagement, and infrastructure development, showcasing its ability to navigate food security amid geopolitical challenges. Qatar adeptly harnessed the private sector to bolster food security in its desert environment and diminish import dependence. This strategic move fortified Qatar’s position as a potent, forward-thinking, and credible state. Over a period, Qatar has emerged as a role model for other Arab and Middle Eastern countries that are facing harsh climate conditions and unruly natural resources that hinder an Agri based economy. This paper endeavors to deeply explore the strategies adopted by this oil rich country to attain self-sufficiency in food and agriculture.

1 Introduction

Qatar, covering an area of 11,628 km2 on the Arabian Peninsula, has only 1.1 percent of its land suitable for farming due to arid conditions and poor soil (Karanisa et al., 2021). Traditionally, the locals depended on fishing, herding, date farming, and limited vegetable cultivation. However, the discovery of natural gas and oil in the early 20th century led to significant urban and infrastructural growth (Hussein and Lambert, 2020). The resulting economic prosperity saw a spike in food and water consumption, with the current average caloric intake in Qatar being 4,275 kcal per day (Al-Thani et al., 2017), exceeding health institution recommendations. Moreover, the expatriate community, constituting over 80 percent of the population, has introduced water-intensive food preferences, such as meat, dairy products, and processed food. This results in Qatar’s heavy reliance on food imports, given its challenging agricultural conditions. The growing dependence on external sources for food and water in Qatar contributes to the country’s reliance on global markets, raising substantial concerns about food security (Ben Hassen and El Bilali, 2019). This situation makes Qatar vulnerable to potential disruptions in food supply chains and fluctuations in prices in the international markets, thus presenting a multifaceted challenge in meeting the needs of its population.

However, recently Qatar has emerged as a significant state actor in the global food landscape, challenging the long-standing dominance of Northern entities. This transformation has been facilitated by Qatar’s strategic utilization of substantial capital resources to support agribusiness ventures, stimulate the development of new trade routes, and foster innovation within the food sector. A pivotal turning point in this trajectory was the 2017 diplomatic crisis. Qatar adeptly harnessed the private sector to bolster food security in its arid environment and reduce its vulnerability to food imports. This strategic maneuver fortified Qatar’s food security and its image as a forward-thinking and credible state actor on the global stage. To contextualize Qatar’s journey towards food security and state-driven capitalism, it is essential to revisit the myriad challenges it faced. These included a history of political blockade, volatile fluctuations in oil prices, extreme temperatures, acute water scarcity (Hussein and Lambert, 2020), and an overreliance on food imports (Karanisa et al., 2021). For instance, the political blockade and diplomatic tensions with neighboring states disrupted food supply chains, accentuating the urgency of achieving self-sufficiency. Fluctuations in oil prices, upon which Qatar’s economy heavily relied, introduced vulnerabilities that could impact food security. Moreover, the harsh desert climate and limited freshwater resources posed formidable obstacles to local food production. Hence, to counter these challenges, Qatar has made significant strides through its National Food Security Strategy(QNSFP) 2018–2023, ranking 24th globally in the 2021 Global Food Security Index (Economist Impact, 2022).

This study posits that narratives around food security empowered Qatar and its agribusiness sector to challenge the traditionally Northern-dominated food regime by introducing state-led capital inflows. It suggests that the Qatari state had various social, economic, and political motives to back this corporate food framework. The research delves into how Qatar utilized its capital, business acumen, and logistical prowess to meet its food security goals. Driven by the necessity to support its 2.6 million residents, Qatar rapidly created alternative supply routes, bolstered local production, and formed new partnerships. Benefiting from its petroleum-rich economy, Qatar adopted new technologies, increased foreign agro investments, and made lasting agreements for food imports, mainly through companies like Hassad Food. This underscores corporations’ significant role in shaping Qatar’s food policies, as endorsed by the Qatar National Food Security Programme (QNFSP), and reveals how the Qatari state strategically invested in food and agriculture, expanding corporate influence over food production.

Food regime theory (Friedman and McMichael, 1989) traces this system’s evolution—from colonial to corporate eras—yet ignites debate over Northern bias and neoliberalism’s scope. While some scholars critique its focus on transnational corporations over state agency (Pritchard, 2009), others detect a multipolar shift (Henderson, 2019). Qatar’s state-led approach tests these tensions, highlighting the interplay of statist and corporate power in food governance. To explore this transformation, this study employs a qualitative case study approach, analyzing national food security plans, peer-reviewed studies, and media reports to address a core question: How did state-led capital reshape Qatar’s food regime to enhance security amid ecological and geopolitical constraints?

This study investigates how Qatar’s state-led capitalism reshaped its food regime, driven by economic necessity, social stability, and geopolitical leverage. It adds to the literature in three explicit ways. First, it challenges the Northern bias of food regime theory (McMichael, 2012) by documenting a Gulf state’s use of state capital to subvert corporate hegemony, offering a hybrid state-corporate model absent from prior frameworks. Second, it extends political economy analyses (e.g., Woertz and Martínez, 2018) by integrating ecological constraints, aridity, and climate change into the study of food security, revealing how environmental limits shape capitalist adaptation in ways overlooked by studies of resource-rich agro-exporters (Henderson, 2019). Third, it bridges a gap in Middle Eastern scholarship, where Gulf states are sidelined, by positioning Qatar as a case of state agency that redefines sovereignty in global food governance. Unlike neoliberal models or Southern export strategies, Qatar prioritizes resilience over profit, providing a novel lens for arid, import-dependent regions. These contributions yield actionable insights for policymakers navigating markets, climate risks, and geopolitical tensions, advancing theoretical and practical food security discourses.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Food regimes

Food regime theory, rooted in Marxism, examines the interplay between food systems, politics, and global economics. A “food regime” denotes a historically delimited configuration of institutional arrangements, power structures, and economic practices that govern the production, circulation, and consumption of food on a transnational scale. Friedman and McMichael’s groundbreaking study, “Agriculture and the State System,” asserts that food security is not just a technical issue. Instead, politics and state interventions profoundly affect food and agriculture. They advocate examining historical shifts in agricultural practices and their links to capitalism and power to understand food regimes. They categorized food regimes based on periods: the British-led regime (1870–1914), exemplified by the extraction of sugar from Caribbean plantations to fuel European industrialization, and the US-led post-war regime (1945–1973), characterized by the dissemination of surplus wheat through Marshall Plan aid to reconstruct Western Europe. These epochs underscore the hegemony of Northern states in orchestrating global agrarian relations.

The advent of globalization led to heightened criticisms of capitalism in food systems (Bernstein, 2016). Debates in the 1980s proposed a new regime; marked by the increased role of transnational corporations and an evolving state role (Friedman and McMichael, 1989). Various frameworks emerged to analyze the contemporary global food context, such as the neoliberal and financialised food regimes (Burch and Lawrence, 2009). While some believe corporate capital and neoliberalism now dominate, others argue in a transitional phase (Friedman, 2009; Pritchard, 2009; Winders et al., 2015; Jakobsen, 2021).

McMichael’s corporate food regime framework accounts for challenges Gulf states face, emphasizing corporate and non-Western influence on food regimes. This aligns with the shifting global power dynamics (Belesky and Lawrence, 2019; Dixon, 2014). This study employs McMichael’s framework as a heuristic lens. Still it critiques its Northern-centric orientation, positing that state-driven interventions in resource-constrained contexts challenge neoliberal hegemony, thereby augmenting discourses on “food sovereignty” (the capacity of nations to autonomously determine their food policies) and the reconfiguration of global agrarian markets (Belesky and Lawrence, 2019; Dixon, 2014; Winders et al., 2015).

2.2 The corporate food regime

McMichael (1992) discusses the current corporate food regime as a progressive stage in capitalism’s political evolution. This regime sees transnational capital prioritized over national interests. This change was facilitated by neoliberal globalization policies, notably through venues like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)'s Uruguay Round (McMichael, 2006). Institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, grounded in free market competition and expanded foreign trade, paved the way for multinational corporations to dominate the global food chain. The 1995 Agriculture Agreement within the WTO institutionalized this regime, enabling corporations to exploit regulatory structures. This framework sheds light on the global food system’s intricate dynamics, including power shifts, structural aspects, and historical contexts, providing a rich viewpoint for analyzing the modern food system.

While the corporate food regime promotes the unhindered movement of goods and services, it disrupts the traditional state-centric international relations model, challenging dominant state-system theories. This shift opposes the northern-dominated corporate food regime (McMichael, 2012). Unlike the first and second food regimes, where the North controlled the South’s food production and distribution, the corporate food regime showcases a multipolar power distribution. Countries in the global South are becoming more assertive, enhancing their food production and distribution capabilities.

The emergence of New Agricultural Countries (NACs) like Thailand and Mexico, which leveraged corporate investment, challenges the dominance of traditional agricultural powers and highlights the shift towards a more diversified global agricultural landscape (Henderson, 2019). However, academia often focuses on major players like the BRICS nations, such as Brazil’s significant share in global soybean exports, sidelining the Gulf states. This study critiques these gaps, arguing that state-mediated responses in peripheral regions contest the supposed universality of the corporate food regime, revealing tensions between neoliberal market logic and national food sovereignty imperatives. This contributes to a broader understanding of global market transformations that move beyond export-centric paradigms (Pritchard et al., 2016).

2.3 Role of the state

Recent scholarship has underscored the significance of the state within the contemporary frameworks of food regimes, though some critiques suggest a relative neglect or insufficient. However, states are instrumental in modulating international food networks and supporting wage relations, vital for maintaining equilibrium in this corporate food-dominated world. Lang and Heasman's (2015) and Clapp’s (2017) studies address the global environmental and social limits associated with state-led food regimes. By doing so, they also navigate the dynamics of accumulation endemic in capitalism. Understanding these processes provides insight into how states like Qatar can maintain food security in the face of a blockade and other international challenges.

Furthermore, the examination of state-led capitalism and neomercantilism by Belesky and Lawrence (2019), along with the exploration of China’s impact on the neoliberal food system, reveals the inherent paradox in economic liberalism. In addition, Young (2017) underscores the importance of the state’s involvement in land acquisitions, emphasizing the Gulf’s profit-driven approach to agribusiness investments and its role in shaping bilateral relations. Henderson (2022) notes that government actions like aid provision and high-ranking official communication reinforce bilateral ties and endorse land investments. Therefore, this study critiques the literature’s under-emphasis on such peripheral actors (Pritchard, 2009), illuminating how Qatar’s ecological and geopolitical constraints enrich understandings of multipolar shifts where power diffuses beyond Northern hegemony and inform strategies for arid, import-dependent regions. Bridging this gap, this study offers a novel lens on state agency, contesting neoliberal assumptions and contributing to global food governance discourses.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study adopts a qualitative research design grounded in the theoretical frameworks of the Corporate Food Regime and the Food Regime Theory to explore the political economy of food systems and the role of the state in shaping food security policies. The Corporate Food Regime perspective highlights the influence of multinational agribusinesses, while the Food Regime Theory provides a historical lens on the global food economy and state interventions. By employing these frameworks, the study examines the dynamics of Qatar’s food security strategy, emphasizing the interplay between state policies, corporate actors, and local agricultural initiatives. The in-depth case study methodology is employed to examine Qatar’s unique food security landscape in this context. Multiple case studies are analyzed, focusing on key actors and initiatives, including Hasad Food, Baladna, and QNFSP. These cases are selected based on their strategic importance to Qatar’s food security vision and their roles in enhancing local food production and supply chain resilience, notably during and after the economic blockade.

3.2 Data

The study relies on multiple secondary data sources, mainly qualitative, encompassing the immediate crisis response to the Gulf blockade and the subsequent institutionalization of food security strategies. Policy document analysis formed a core component, including examination of QNFSP reports, strategic plans from the Ministry of Municipality and Environment, and annual reports and investment portfolios from Hassad Food. Economic and trade data was gathered from authoritative sources including FAOStat agricultural production indices, Qatar Planning and Statistics Authority, trade reports, and datasets from the Global Food Security Index published by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Media and gray literature analysis included systematic coverage monitoring from Al Jazeera, The Peninsula Qatar, and Gulf Times and business analyses from Financial Times and Reuters.

The methodology acknowledges some limitations. Language constraints represent one limitation, as Arabic materials were not incorporated, and some policy nuances may be underrepresented; the rapid evolution of Qatar’s food security landscape presents another challenge, meaning some recent developments may not be fully captured in the analysis.

4 Analysis and discussion

4.1 Domestic measures

4.1.1 Qatar National Food Security Programme (QNFSP)

The QNFSP was launched in 2008 with the goal of achieving 70 percent food self-sufficiency by 2013. The QNFSP was set up in Qatar with a starting capital of US$1 billion as a direct reaction to the 2007–2008 global food crisis (Sippel, 2013). Even though Qatar’s strong financial position made it less susceptible to the effects of price hikes, the crisis, marked by surging food prices and supply chain issues, triggered worldwide food security fears. With significant funds dedicated to the QNFSP, Qatar’s intended to strengthen its local food production, improve self-reliance, and ensure consistent and accessible food provisions for its residents. It prioritized various sectors, including agriculture, water, renewable energy, and food manufacturing, and aimed to enhance resource utilization, environmental protection, and profitability through advanced farming and irrigation methods.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the QNFSP was compromised by the 2017 blockade imposed on Qatar, which severely exposed its ongoing dependence on foreign food sources. In response, Qatar released an updated QNFSP (2018–2023) that outlined specific targets for achieving food self-sufficiency. While Qatar was dependent on imports for 85 percent of its vegetable intake, the nation has devised a plan to create a hydroponic greenhouse cluster to reach 70 percent self-sufficiency in the production of greenhouse vegetables like tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, zucchini, and lettuce as Food Security Department of Qatar reports in 2020. Qatar hoped to eliminate its reliance on fresh milk and poultry imports by ending specials and redirecting resources to other uses, such as transforming excess chicken into eggs. Furthermore, it intended to increase its ability to produce meat and fish by constructing sheep and goat breeding farms, fattening units, and fish husbandry. The Ministry of Municipality and Environment expected a 30 percent rise in cattle output and a 65 percent increase in fish production (The Peninsula Qatar, 2019). To achieve these ambitious goals, the QNFSP relies on the support of Hassad Food, Qatar’s agribusiness investment branch.

4.1.2 Hassad Food, Baldana and Wildam

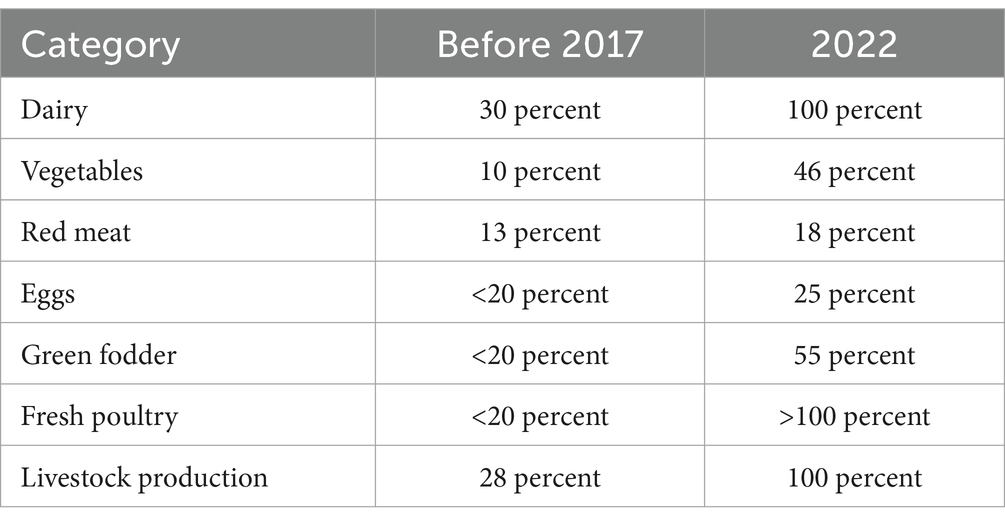

In 2008, Hassad Food was established as a fully owned subsidiary of the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA). It was designed to serve as Qatar’s investment arm in the food and agribusiness sectors, both internationally and locally. Hassad Food is owned by the QIA, the country’s sovereign wealth fund with a total value of US$115 billion, primarily funded through the sale of natural gas. Through Hassad Food, the government has established funding programs to encourage participation from private sector operators and ensure the nation retains control over its food production and distribution processes. Hassad Food is crucial in securing Qatar’s food supply by investing in domestic and foreign farming companies and engaging in various activities, including producing and selling fresh produce, cattle, dairy products, animal feed, and poultry (McSparren et al., 2017). Hassad Food, as the parent company of various Qatari businesses, dominates the food sector by strategically investing in key agricultural industries. It is the parent business of Aswaq for Food Facilities Management, which oversees the major food markets, and Mahaseel for Marketing & Agri, which provides marketing services to more than 400 local farmers (Hassad Food, 2023). Moreover, Hassad invested in the Arab Qatari Agricultural Production Company (QATFA), the largest plantation in Qatar, and the Arab Qatari Company for Chicken Production (Al-Waha), Qatar’s largest chicken supplier. It also owns stakes in the National Food Company “NAFCO” and Aalaf Qatar, which own a major dates processing plant and three large livestock feed fields in Qatar. These investments enable Hassad to diversify its agricultural portfolio and focus on critical food products highly consumed in Qatar, such as produce, chicken, dairy, and livestock feed. Furthermore, Hassad purchased essential shares in the local dairy and livestock companies Baladna Company and Widam Food Company. Baladna is one example of the kingdom’s successful partnerships with Qatari agribusinesses. In 2017, Baladna brought 16,000 dairy cows by sea and 4,000 by air to significantly increase domestic dairy output in Qatar (Invest Qatar, 2022). Baladna’s subsequent initial public offering (IPO) 2 years later for QAR1.4 billion ($380 million) further demonstrated the success of this partnership and its contribution to Qatar’s food security. Now openly traded on the Qatar Stock Exchange, the business supplies 95 percent of the nation’s dairy needs. Therefore, corporate agribusiness, led by Hassad Food and its investments in various sectors, has been crucial in enhancing Qatar’s food security following the 2017 blockade by increasing domestic production and reducing reliance on imports, particularly in key areas, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Qatar food self-sufficiency rates (Al Jazeera, 2020; The Peninsula Qatar, 2020b, 2023).

4.1.3 Agricultural financing

Qatar Development Bank (QDB) is a key player in Qatar’s pursuit of food security. Through its “Jahez” initiative, QDB supports small and medium-sized industrial companies by providing fully equipped manufacturing facilities. This endeavor addresses challenges these businesses face offering rapid setup and operational support. QDB’s comprehensive approach includes guidance and knowledge exchange programs, fostering a nurturing environment for entrepreneurs. The bank’s selection criteria ensure that applicants possess industry expertise and a forward-looking vision, aligning with Qatar’s food security goals. Collaborations with Qatar Islamic Bank (QIB) further facilitate financing for sectors vital to food security. In essence, QDB’s multifaceted efforts, from offering industrial facilities to financial support and guidance, significantly enhance Qatar’s food security. By empowering local businesses, QDB reduces reliance on food imports, reinforcing Qatar’s commitment to ensuring a stable and sustainable food supply for its growing population.

Notably, Qatar’s self-sufficiency rate for fresh poultry exceeded 100 percent in 2019, suggesting a surplus for this category. According to data from the Qatar Development Bank (2022), the share of Qatar’s labor force employed in agriculture increased from 1.23 percent in 2015 to 1.53 percent in 2019, reflecting the sector’s growth through an expanding workforce. These numbers indicate a positive development in Qatar’s efforts to strengthen its agricultural capabilities and enhance its overall food security.

4.1.4 Consumption patterns

Changes in food consumption are another facet of Qatar’s efforts to achieve food security. Indeed, food consumption, particularly within the context of supermarkets, became a geopolitical battleground as new trade arrangements replaced products made by the blockading countries with those from alternative sources (Monroe, 2020). Supermarkets helped bridge the gap created by the blockade and maintained a steady flow of food items in the market. Nevertheless, the situation both shaped and was shaped by nationalist sentiments to incentivize national production and reduce import dependence. The state’s efforts to increase domestic food production via heavy subsidies and advertising fostered a new consumer culture centered on buying locally produced goods. In Doha, Baldana advertisements prominently showcase its dual message of ‘Made in Qatar’ and ‘Made by Nature’ (Koch, 2021, p. 124). By promoting fresh and nutritious food options, they encouraged healthier eating habits. These efforts aimed to ensure access to nutritious food options and minimise wastage in the food supply chain. By addressing food waste, Qatar intended to optimise its available resources and ensure a more sustainable and efficient food system (The Peninsula Qatar, 2020a,b). The state implemented rigorous standards in its production processes, ensuring that locally produced food met the highest safety requirements to safeguard the quality of food but also to build trust among consumers, assuring them that the food available was safe for consumption (Eltai et al., 2018). Together, their efforts aimed to overcome the challenges of the blockade by consuming locally.

Buying and consuming local products became a patriotic act supporting the nation during a challenging time. First, it helped keep the local economy afloat during the blockade and promoted long-term economic growth by developing domestic industries. Second, showing that it could survive and even thrive under the blockade, Qatar sent a strong message to the international community about its resilience and independence. Furthermore, through food, expatriate consumers could participate in a seemingly less politically charged form of nationalism by purchasing and endorsing locally produced products. Although local food movements are commonly portrayed as resistance against government-backed agricultural programs that favor large multinational cooperations, the case of Qatar demonstrates a shift towards the nation-state. Thus, the state’s involvement explains how ideologies and national imaginaries are created and disseminated through food. Together, the state, supermarkets and agribusiness created a new consumer culture and form of nationalism, which sent the international community a strong message of national resilience and independence.

4.1.5 Technology and infrastructures

Furthermore, Qatari agribusinesses’ involvement in ensuring food security encompasses crisis management and advancing research and development. As an integral part of the QNFSP, the country is committed to enhancing resource efficiency in agriculture, considering its inherent natural constraints. Qatar’s local food production faces significant challenges due to its location in one of the world’s driest regions. These challenges include limited water resources, a scarcity of arable land, and high temperatures (Ismail, 2015). Consequently, these factors have led to inefficient groundwater utilisation for irrigation, decreased water availability, increased soil salinity, and a growing demand for intensive land use, water, and energy resources (Bilal et al., 2021). Qatar has embraced innovative technologies such as aquaponics and vertical farming to improve the sustainability and reliability of its water sources, thereby enhancing food resilience and self-sufficiency. The country seeks to explore novel farming techniques that maximise the utilisation of treated sewage and desalinated water for food production. By 2023, Zulal Oasis, a state-backed agriculture investment arm, hopes to use patented greenhouse technology to provide up to 70 percent of Qatar’s demand for locally grown vegetables (Beer, 2014). Consequently, state-backed corporate agribusiness plays a significant role in mitigating the limitations of Qatar’s natural conditions. On the one hand, these initiatives aim to improve production efficiency, increase agricultural yields, and reduce water usage. On the other hand, these technological advancements allow the ruling elite to demonstrate their capacity to adjust and address environmental challenges, thereby reinforcing their credibility and authority. Agrico, a family-owned business that has been buying and shipping food for 70 years, further illustrates such dynamics. Although water shortage is a constant burden in a nation where the average maximum monthly rainfall is only 15 mm and summer temperatures surpass 40C, it has not prevented the agri-tech firm from converting these limitations into a business opportunity (Invest Qatar, 2022). Agrico engages in what its chairman, Ahmed AlKhalaf, refers to as agricultural manufacturing. The company aims to increase production after the first harvest of fresh shrimp, which it presently produces at one ton per day, to one thousand tons annually by extending its technology and operations into other nations like Oman, Malaysia, and Iraq. According to Agrico’s owner: “since the technology is available, there is nothing stopping us from reaching our targets” (Al Jazeera, 2020). Additionally, Agrico works with the Finnish agri-tech firm iFarm to build cutting-edge vertical farms. Ahmed Al-Khalaf adds: “We have modified technology developed in the Western World and adapted it even further to have a very unique system anywhere in the world,” (quoted in Aguilar, 2018). Hence, Agrico has made notable efforts to integrate Qatar’s capital into the global corporate food regime by acting as a mediator between the Northern capital and the Gulf region. By showcasing its technological advancements, Qatar can position itself as an innovative and influential player in the global food economy, attracting investment, forging partnerships, and strengthening its geopolitical position while dominating traditional North countries.

Qatar’s last identified domestic initiative is a stockpiling strategy to ensure a steady food supply in emergencies. Following the Blockade, the government created a food reserve, which includes essential food items such as rice, flour, sugar, and oil. The stockpile is maintained at a level that ensures the country has enough food to last for 6 months in case of an emergency, such as during Covid-19 (The Peninsula Qatar, 2022). There is a system of regular rotations, inspections and quality checks to ensure the food remains safe for consumption. In this project, Hassad Food promotes the expansion of associated services such as cooling and storing, which are essential for maintaining food quality and ensuring that the reserve remains fresh. Through partnerships with the state and collaboration with Hassad, businesses in Qatar can gain access to funding and receive special treatment from government organizations, recognizing their crucial role in achieving food security goals. As a result, the distinction between food security objectives and profit-seeking discourse once again becomes blurred and adaptable. Qatar’s state capitalism exhibits a dual effect, reshaping the traditional structure of international agriculture through domestic measures while simultaneously promoting private interests openly.

4.2 International measures: investments, trade and logistics

Although Qatar has made significant strides towards achieving self-sufficiency in food production, its reliance on imports continued to account for over 50 percent of its total food consumption (Food Security Department Qatar, Ministry of Municipality and Environment, 2020). This imported food must transit through the narrow chokepoints of the Hormuz and Bab Al Mandab straits, which pose a significant threat to the safe delivery of essential supplies due to the potential risks of Iran’s actions, Somali piracy, and the ongoing conflict in Yemen. Hence, the QNFSP outlines a critical pillar that centers on establishing sustainable and dependable supply chains over the long term through international trade and logistics. It aims to develop a resilient food import strategy to withstand potential trade shocks and disruptions. Among the initiatives, the government has implemented regulatory measures to incentivize new partnerships and the private sector to seek alternative food sources from various places as Food Security Department Qatar reports in 2020. These measures include tax incentives, subsidies, and regulatory frameworks encouraging the corporate food regime while challenging traditional flows.

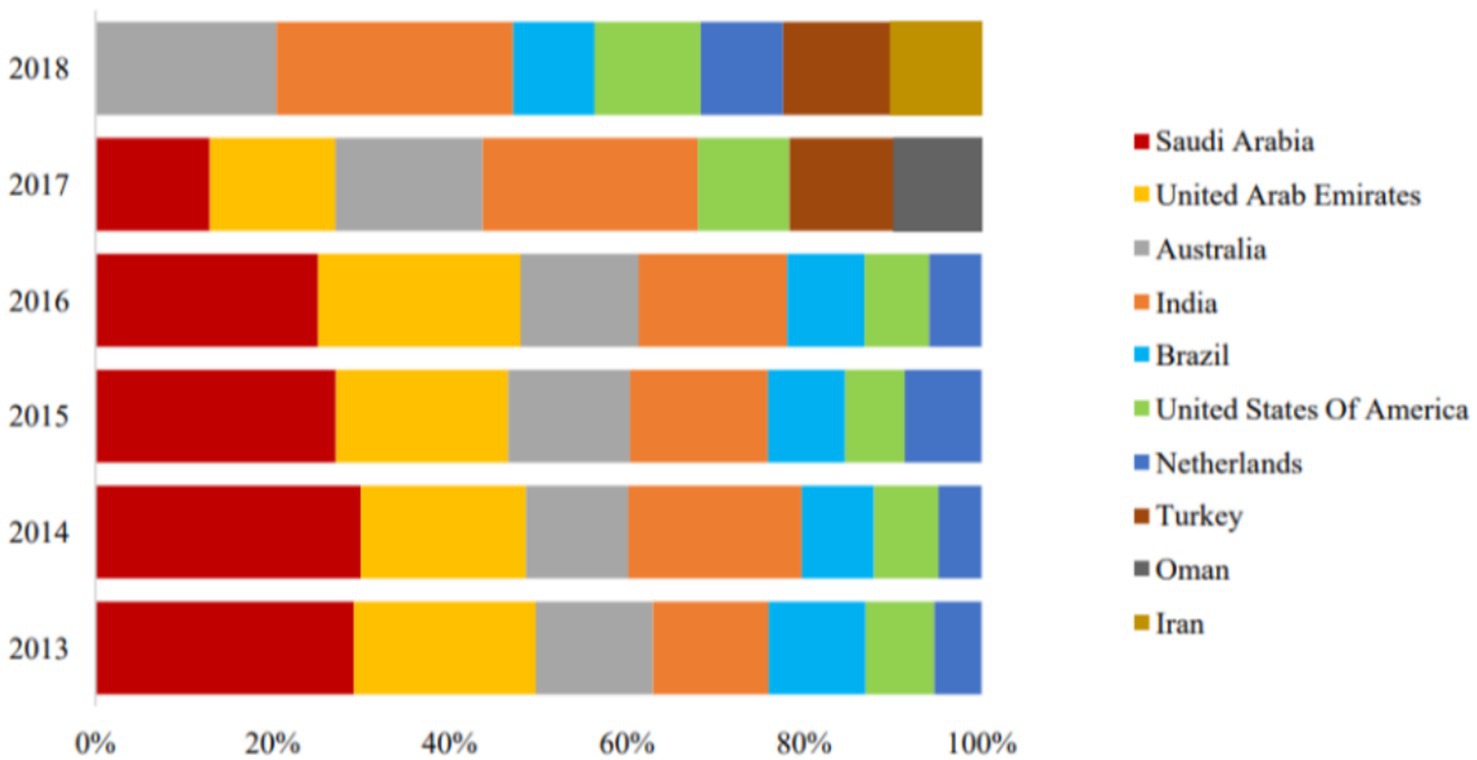

Qatar’s response encompassed the tactical establishment of new relationships with various nations, thus transforming adversity into an opportunity for building new alliances. The situation’s urgency necessitated a quick transition to alternative supply sources. It was clear from the onset that a shift towards diversification was not just necessary but a strategic imperative to make allies in the broader geopolitical landscape. The objective is to reduce Qatar’s vulnerability to external factors by diversifying the geographical locations of trade partners for essential commodities, with a target of having 3–5 partners per critical item. Additionally, it strives to mitigate the effects of trade shocks or other unexpected disruptions by proactively establishing contingency plans. These nations stepped in rapidly to fill the supply void, sending planeloads of food and other necessities, thus establishing themselves as reliable partners during the crisis. Figure 1 shows the contribution of the top 10 countries to the economic value of food trade in Qatar for the years 2016, 2017, and 2018, with significant changes in after 2016. In 2016, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were the dominant contributors, reflecting Qatar’s reliance on neighboring Gulf countries for food imports. However, in 2017, their shares significantly declined due to the diplomatic and economic blockade imposed on Qatar by its Gulf neighbors. Consequently, Qatar diversified its food trade partners, increasing imports from countries like Turkey, Iran, and Brazil. By 2018, the data shows a more balanced distribution, with a noticeable rise in the contributions from Australia, Brazil, and India, highlighting Qatar’s strategic shift towards sourcing food from more distant but reliable partners to enhance its food security. Hence, food became intricately linked with politics (Meneley, 2011). The diversification also saw the establishment of direct trade routes that circumvented the blockade. These new maritime routes were put in place to facilitate the import of food and other essentials directly from countries like Oman, Pakistan, and India (Al-Abdelmalek et al., 2023). It represented a clear break from the dependence on traditional partners and a move towards a new, more diversified, resilient food supply chain. The transition was closely monitored by national news media, which depicted Iranian cargo planes being loaded with food and supermarkets stocking Turkish milk, among other examples (The Voice of America, 2017). These reports aimed to inform the country’s residents about the logistical changes taking place and reassure them that there would be no shortage of food. It also showed the blockading countries that Qatar could withstand their sanctions’ impact.

Figure 1. Top 10 countries’ contribution to food trade in Qatar (Al-Abdelmalek et al., 2023).

The QNFSP underpinned these efforts through its proactive role in fostering partnerships with key international players, including initiatives that encouraged the private sector in Qatar to develop relationships with trade missions and entities in target countries (Food Security Department Qatar, Ministry of Municipality and Environment, 2020). As a wealthy nation, Qatar can approach food security through asset purchases, management, production and financial mechanisms. John McKillop, CEO of Hassad Australia, suggested in the Financial Review that foreign agricultural investments could potentially result in cheaper goods and other favorable economic outcomes for Qatar (Cranston, 2016). Following this financialization logic, Hassad Food purchased properties in Sudan and Australia and plans to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in farming initiatives in Kenya, Brazil, Argentina, and Ukraine (Fuchs, 2012). It signifies a spatial reconfiguration of the food regime, reflecting a shift in the dynamics of the corporate food system. It exemplifies how Qatar no longer rely solely on global markets and instead seeks to challenge the dominance of agro-exporting corporations primarily based in the Global North. In the Arab world, Hassad possesses stakes in the Arab Company for Livestock Development (ACOLID) and the Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development (AAAID). In addition to its shares in the largest fully integrated poultry project in Oman, A’Saffa Foods, in 2019, Hassad invested in the seafood sector by acquiring the International Seafood Company. Moreover, Hassad expanded its investments in 2020 by acquiring shares in Sunrise Foods International, a leading global processor and trader of organic grains and oil seeds. Sunrise Foods holds a substantial market share in North American and European markets and has established a broad network of suppliers to source high-quality grains for its customers worldwide. Thus, Qatar’s extensive worldwide investments in agriculture can be understood in the context of a broader trend in the global food regime, which is increasingly being shaped by capital flowing from the Gulf states. Another notable point is Hassad ownership of substantial agricultural land in Australia and its strategic partnership with Australian firm MIRA (Sippel, 2013). The fact that Qatar has invested in Australia, considered part of the Global North with reliable production of safe, green, high-quality food, demonstrates a departure from the traditional North–South dynamics, where capital typically flows from developed to developing countries. This shift enables Qatar to diversify its food sources and reduce its reliance on imports, thus increasing its resilience in the face of potential food shortages.

The concept of internationalization has become increasingly important in response to the broader trend of Gulf capital. Agribusiness firms from the Gulf region have emerged as influential participants in the agricultural value chain (Hanieh, 2018). The significance of this sector extends beyond its economic implications, as it also holds geopolitical importance and is driven by the securitizing discourse around food (Koch, 2021). The framing surrounding food security has accelerated the logic of agro-security mercantilism, as illustrated by Qatar’s notable ownership of foreign agricultural land. It acquired 3,000 square kilometers of prime agricultural property in Australia through Hassad Food for over $500 million and government-owned land in Turkey and India (Beer, 2014). Additionally, establishing a 2,000-hectare Qatari farm in Sudan has bolstered the country’s self-sufficiency efforts (Chandran, 2017). Thus, the availability of land has played a pivotal role in the expansion of the food industry—for Qatar—and, as a result, has a significant impact on food security (Dixon, 2014).

The corporate food regime of Qatar aims to advance its own interests and enhance its capabilities in food production and distribution. This regime’s expansion extends geographically, and its logistical operations are crucial. The nation’s plan aims to improve its logistics framework, encompassing ports and transportation systems, to promptly respond to the absence of trade partners or a decline in self-reliance (Alagos, 2022). It aims to connect new regions to its market and consolidate its role as a food reexport zone. Launched in 2017, Hamad Port Food Security Project spreads over 500,000 square meters; it includes three main factories and three factories behind the processing plants (The Peninsula Qatar, 2022). The project includes specialized facilities for manufacturing, processing, and refining rice, unrefined sugar, and edible oils. The factories’ production is said to be enough for three million people and aims to supply products for local, regional, and global use (The Peninsula Qatar, 2022). Indeed, the stock has a two-and-a-half-year shelf life and may be shipped again outside the nation. Therefore, the US$ 400 million Hamad Port Food Security Project is poised to put Qatar on the map as a solid food-exporting hub. Such food security programs are political initiatives interconnected with the security of logistical operations, the expansion and strengthening of agro-commodity circuits, and, notably, the control over trade routes and logistical networks (Henderson and Ziadah, 2023). It sheds light on how Qatar, as a new player, is entering the agro-commodity circuits and reorganizing the food regime to challenge Northern domination.

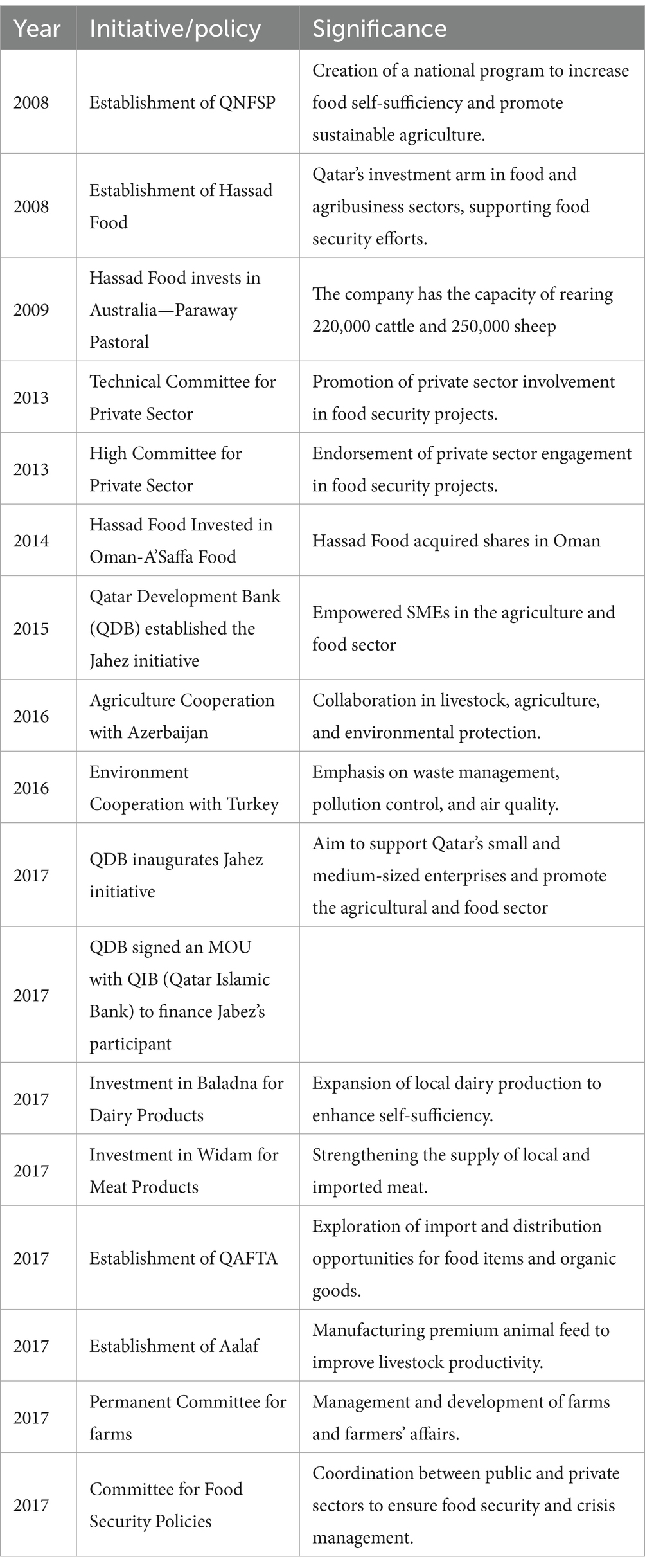

Lastly, Qatar Airways played a pivotal role in responding to the blockade imposed on the nation in 2017 by securing essential supplies and improving its logistics network. The company bolstered its efforts by adding five more freighters, successfully implementing the Freighter Centralized Load Control system, and transitioning to fully digital ramp handling across its entire freighter network (Air Cargo News, 2017). As a result, load planning improved, and on-time performance saw a 30 percent increase compared to the previous year. Today, Qatar Airways Cargo ranks as the second-largest cargo carrier globally, serving over 60 cargo destinations worldwide, enabling imports from various new countries. Hence, the consequences of the blockade provided an impetus for the airline to expedite its existing five-year plan, which focused on several key areas, including strengthening functionality and soft power, enhancing innovation, broadening brand-building, and defining the relationship between the state and the airline. Ultimately, the country experienced a 160 percent increase in cargo imports in June 2017, indicating the effectiveness of the measures implemented to respond to the blockade. Furthermore, structural changes to the supply chain were implemented, leading to the complete restocking of food inventory levels. The country’s logistics network was also significantly diversified by introducing two key maritime shipping routes from Asia and Oman. On the one hand, the magnitude of Qatar’s investments in this sector suggests that its influence on the global food commodities market is growing, transcending its domestic market needs. On the other hand, Qatar’s geographical growth through its logistics network has positioned this Gulf nation at the heart of the agricultural value chain. Therefore, the company’s efforts positioned Doha as a global hub while strengthening Qatar’s corporate food regime through public and private partnerships and geographical diversification. Table 2 provides a summary of policy development to strengthen food security in Qatar between 2008 and 2017.

Table 2. Brief overview of the evolution of Qatar’s food security programs 2008–2017 (author’s review).

5 Conclusion

According to the corporate food regime, the world’s food system is increasingly dominated by multinational corporations, marking a significant shift from the traditional, geographically defined agricultural regimes. This theoretical construction helps to understand the complex interplay of market forces, corporate strategies, and state policies in shaping global food systems. While previous literature within this framework lacked focus on the state’s role, this research addresses the gap by examining Qatar as a case study. The research identifies Qatar’s innovative “state-financialized food governance” model as demonstrating several transformative characteristics that challenge conventional food regime theory. These include the strategic deployment of sovereign wealth to build resilient food systems, substantial investments in agricultural technologies specifically adapted to arid environments, and the creation of diversified international trade networks that significantly reduce vulnerability to supply shocks, particularly evident in Qatar’s rapid response to the 2017 blockade.

By employing a qualitative case study approach grounded in the Corporate Food Regime and Food Regime Theory, this study provides a detailed analysis of Qatar’s food security strategy, focusing on the roles of Hasad Food and QNFSP. The research contributes to the broader discourse on food security and political economy. Hassad Food occupies a unique position within the corporate food regime due to its operations in the agri-business sector. Nevertheless, Hassad Food combines the characteristics of a business-oriented corporation with the responsibilities and accountability associated with being a state-owned enterprise. As a corporation, Hassad Food seeks to profit by investing in the agriculture and food industries worldwide. This aligns with the profit-driven nature of entities in the corporate food regime, potentially conflicting with food security principles or environmental sustainability. However, being state-owned means that Hassad Food operates with public accountability and pursues strategic goals beyond mere profitability. This dual role creates inherent ambiguity in Hassad Food’s function within the corporate food regime. In conclusion, Hassad Food, being a state-owned corporation, offers an intriguing case study to exemplify the intricate and multi-dimensional nature of actors operating within the corporate food regime.

The close relationship between the public and private sectors highlights the unique dynamics of food security in Gulf countries. Qatar created a beneficial environment for corporations. It sheds light on the state’s motives to collaborate with private enterprises to address food security challenges effectively. Notably, the blockade incident transformed Qatar’s food security strategy, showcasing the nation’s resilience and adaptability in the face of adversity. These findings highlight Qatar’s successful diversification of food imports and promotion of local production to mitigate the blockade’s effects. However, the novel aspect of this research lies in understanding the motives behind the state’s actions, providing valuable insights for other nations facing similar issues.

Qatar’s efforts to expand and diversify its food supply chains have reduced its reliance on imports and created a stable and reliable food supply. It has decreased the vulnerability of its economy to external factors and opened business opportunities within the country by tremendously increasing domestic production and consumption thanks to technological advances. These initiatives were deeply rooted in discourses surrounding food security, with consumption pattern changes framed as acts of patriotism. This narrative reinforces the national commitment towards self-sustainability and encourages citizens to participate in this transformative journey actively. Moreover, the government’s investment in agricultural technologies and practices demonstrates the state’s technological prowess, legitimising its authority and reinforcing its power over the population. In turn, it can increase Qatar’s global standing and reputation, potentially leading to increased diplomatic support and cooperation from other nations. Through techno-politics, food has served as a means to navigate the geopolitical and environmental challenges of the blockade.

This paper adds to the ongoing food regime debate by examining the influence of Qatar’s capital in shaping the corporate food system. Introducing state-led capital flows through infrastructure development and international investments underscores Qatar’s potential to influence food systems beyond its borders. These initiatives challenge the traditional dominance of Northern countries in the global food regime, where power and control over food production, distribution, and trade have traditionally been held. Qatar enhances its food security by actively participating in the food system through strategic logistical development and creating a surplus in self-sufficiency. It establishes itself as a powerful player in shaping the global food landscape. This demonstrates Qatar’s ambition to contribute to a more multipolar food system and challenge existing power dynamics.

However, building on David Pimentel’s foundational critiques of industrial agriculture and Orozco-Meléndez and Paneque-Gálvez's (2024) framework for sustainable food systems, the analysis reveals how Qatar’s model could be strengthened through greater incorporation of ecological justice principles and more inclusive governance structures. The current heavy reliance on capital-intensive technological solutions, while impressive in its immediate results, raises important questions about long-term sustainability and energy efficiency that must be addressed. Similarly, while Qatar’s offshore agricultural investments have enhanced its food security, their broader impacts on local communities and ecosystems in host countries require more thorough examination and mitigation strategies.

Several concrete recommendations emerge for enhancing Qatar’s food security model. The country’s technological innovations in controlled-environment agriculture could be productively paired with community-based knowledge systems through participatory research programs that engage both scientists and local farmers. The Qatar Investment Authority and Hassad Food could develop and implement comprehensive environmental and social criteria for agricultural investments abroad, ensuring they contribute meaningfully to sustainable development in host countries rather than simply extracting resources. Building on post-normal science approaches, Qatar’s food security institutions could establish formal mechanisms for incorporating civil society and indigenous perspectives into agricultural research and policy-making processes. Dedicated agroecology pilot programs could be initiated by allocating a portion of Qatar’s substantial agricultural research budget to testing approaches that combine modern technology with ecological principles. Furthermore, Qatar could leverage its considerable financial and technical resources to support regional food sovereignty initiatives across the Gulf, particularly those focused on smallholder farmers and sustainable practices.

Given the scope of this research, a deeper investigation of the economic, environmental, and social implications of Qatar’s food security strategies is needed. Economically, this could involve studying the effects of Qatar’s investments on agricultural markets and rural livelihoods in both Qatar and the host countries. Environmentally, it would be necessary to examine the impacts of Qatar’s agrarian practices on soil health, water resources, and biodiversity. Socially, future research could focus on the effects of Qatar’s strategies on issues like land rights, labor conditions, and rural development in the countries where it has made investments. Comprehensive research in these areas could help better understand the full implications of Qatar’s corporate food security approach and inform future policy decisions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BF: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MT: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research is supported by National Priorities Research Program #12C-0804-190009, entitled SDG Education and Global Citizenship in Qatar: Enhancing Qatar’s Nested Power in the Global Arena, from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). OA Funding provided by QNL Qatar.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguilar, J. (2018). 1mn sqm of land for indoor farming to boost Qatar’s Agri sector. Gulf Times, April 2. Available online at: https://www.gulf-times.com/story/587521/1mn-sqm-of-land-forindoor-farming-to-boost-Qatar

Air Cargo News. (2017). Qatar airways outlines its cargo response to air space "blockade". Air Cargo News, September 6. Available online at: https://www.aircargonews.net/qatar-airways-outlines-its-cargo-response-to-air-space-blockade/20111.article

Al Jazeera. (2020). Qatar's food security boost post-blockade. Al Jazeera News, June 9. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/program/newsfeed/2020/6/9/qatars-food-security-boost-post-blockade

Al-Abdelmalek, N., Kucukvar, M., Onat, N. C., Fares, E., Ayad, H., Bulak, M. E., et al. (2023). Transforming challenges into opportunities for Qatar’s food industry: self-sufficiency, sustainability, and global food trade diversification. Sustain. For. 15:5755. doi: 10.3390/su15075755

Alagos, P. (2022). Qatar on way to meet 2023 food security goals. Gulf Times, December 30. Available online at: https://www.gulf-times.com/article/652401/qatar/qatar-on-way-to-meet-2023-food-security-goals

Al-Thani, M., Al-Thani, A.-A., Al-Mahdi, N., Al-Kareem, H., Barakat, D., Al-Chetachi, W., et al. (2017). An overview of food patterns and diet quality in Qatar: findings from the National Household Income Expenditure Survey. Cureus. 9, 1249–1265. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1249

Beer, E. (2014). Hassad Food agrees $500m Turkey investment. Food Navigator. 17 October. Available online at: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2014/10/17/Hassad-Food-agrees-500m-Turkey-investment/

Belesky, P., and Lawrence, G. (2019). Chinese state capitalism and neomercantilism in the contemporary food regime: contradictions, continuity and change. J. Peasant Stud. 46, 1119–1141. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1450242

Ben Hassen, T., and El Bilali, H. (2019). Food security in the Gulf cooperation council countries: challenges and prospects. J. Food Secur. 7, 159–169. doi: 10.12691/jfs-7-5-2

Bernstein, H. (2016). Agrarian political economy and modern world capitalism: the contributions of food regime analysis. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 611–647. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1101456

Bilal, H., Govindan, R., and Al-Ansari, T. (2021). Investigation of groundwater depletion in the state of Qatar and its implication to energy water and food nexus. Water. 13:2464. doi: 10.3390/w13182464

Burch, D., and Lawrence, G. (2009). Towards a third food regime: behind the transformation. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 267–279. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9219-4

Chandran, S. (2017). 2,000-hectare Qatari farm in Sudan a boost to Qatar’s self-reliance move. Qatar Tribune, September 17. Available online at: https://www.qatar-tribune.com/article/85946/FIRSTPAGE/2000-hectare-Qatari-farm-in-Sudan-a-boost-to-Qatar-39s-self-reliance-move

Clapp, J. (2017). Bigger is not always better: The drivers and implications of the recent agribusiness megamergers. Waterloo, ON, Canada: University of Waterloo.

Cranston, M. (2016). Qatar's Hassad defends Australian agriculture investment results. The Australian Financial Review, March 13. Available online at: https://www.afr.com/property/qatars-hassad-defends-australian-agriculture-investment-results-20160311-gngidp

Dixon, M. (2014). The land grab, finance capital, and food regime restructuring: the case of Egypt. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 41, 232–248. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2013.831342

Economist Impact. (2022). Global Food security index 2021 – the 10-year anniversary. The Economist Impact Group Available online at: https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/about

Eltai, N. O., El-Obeid, T., Kassem, I. I., and Yassine, H. M. (2018). “Food regulations and enforcement in Qatar” in Reference module in food science (Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Food Security Department Qatar, Ministry of Municipality and Environment. (2020). Qatar National Food Security Strategy 2018 – 2023. Food Security Department Qatar. Available online at: https://www.mme.gov.qa/pdocs/cview?siteID=2&docID=19772&year=2020

Friedman, H. (2009). Moving food regimes forward: reflections on symposium essays. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9225-6

Friedman, H., and McMichael, P. (1989). Agriculture and the state system: the rise and decline of national agricultures, 1870 to the present. Sociol. Rural. 29, 93–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00360.x

Fuchs, M. (2012) Qatar’s next big purchase: a farming sector. Reuters, January 6. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-qatar-food/qatars-next-big-purchase-a-farming-sectoridUKTRE8051V220120106/

Hanieh, A. (2018). Money, markets, and monarchies: The Gulf cooperation council and the political economy of the contemporary Middle East. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hassad Food. (2023). Investment portfolio. Hassad Food. Available online at: https://www.hassad.com/investment-portfolio/

Henderson, C. (2019). Gulf capital and Egypt’s corporate food system: a region in the third food regime. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 46, 599–614. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2018.1552583

Henderson, C. (2022). The rise of Arab gulf agro-capital: continuity and change in the corporate food regime. J. Peasant Stud. 49, 1079–1100. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2021.1888723

Henderson, C., and Ziadah, R. (2023). Logistics of the neoliberal food regime: circulation, corporate food security and the United Arab Emirates. New Polit. Econ. 28, 592–607. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2022.2149721

Hussein, H., and Lambert, L. A. (2020). A rentier state under blockade: Qatar’s water-energy-food predicament from energy abundance and food insecurity to a silent water crisis. Water 12:1051. doi: 10.3390/w12041051

Invest Qatar. (2022). Food from the desert: Qatar's nourishing investment. Financial Times, October 18. Available online at: https://investqatar.ft.com/article/food-from-the-desert

Ismail, H. (2015). Food and water security in Qatar: part 1—Food production. Future Directions International Pty Ltd.: Perth, Australia, 6. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Food+and+Water+Security+in+Qatar:+Part+1%E2%80%94Food+Production&author=Ismail,+H.&publication_year=2015

Jakobsen, J. (2021). New food regime geographies: scale, state, labor. World Dev. 145:105523. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105523

Karanisa, T., Amato, A., Richer, R., Majid, S. A., Skelhorn, C., and Sayadi, S. (2021). Agricultural production in Qatar’s hot arid climate. Sustain. For. 13:4059. doi: 10.3390/su13074059

Koch, N. (2021). Food as a weapon? The geopolitics of food and the Qatar–gulf rift. Secur. Dialogue 52, 118–134. doi: 10.1177/0967010620912353

Lang, T., and Heasman, M. (2015). Food wars: The global Battle for mouths, minds and markets. 2nd Edn. Earthscan: London, UK.

McMichael, P. D. (1992). Tensions between national and international control of the world food order: contours of a new food regime. Sociol. Perspect. 35, 343–365. doi: 10.2307/1389383

McMichael, P. (2006). “Global development and the corporate food regime” in Research in rural sociology and development. eds. F. H. Buttel and P. McMichael (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited) Vol. 12, 265–299. doi: 10.1016/S1057-1922(06)12010-2

McMichael, P. (2012). The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. J. Peasant Stud. 39, 681–701. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.661369

McSparren, J., Besada, H., and Saravade, V. (2017). Qatar’s global investment strategy for diversification and security in the post-financial crisis era. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Centre on Governance, University of Ottawa.

Meneley, A. (2011). Blood, sweat and tears in a bottle of Palestinian extra-virgin olive oil. Food Cult. Soc. 14, 275–292. doi: 10.2752/175174411X12893984828872

Monroe, K. V. (2020). Geopolitics, food security, and imaginings of the state in Qatar’s desert landscape. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 42, 25–35. doi: 10.1111/cuag.12243

Orozco-Meléndez, J. F., and Paneque-Gálvez, J. (2024). Co-producing uncomfortable, transdisciplinary, actionable knowledges against the corporate food regime through critical science approaches. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 29863–29890. doi: 10.1007/s10668-023-03377-9

Pritchard, B. (2009). The long hangover from the second food regime: a world-historical interpretation of the collapse of the WTO Doha round. Agric. Hum. Values 26, 297–307. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9216-7

Pritchard, B., Dixon, J., Hull, E., and Choithani, C. (2016). ‘Stepping back and moving in’: the role of the state in the contemporary food regime. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 693–710. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1136621

Sippel, S. R. (2013). Arab-Australian land deals between Food security, commercial business, and public discourse. LDPI Working Paper. 27. The Land Deal Politics Initiative.

The Peninsula Qatar. (2019). Qatar to develop storage facility for 22 essential items for at least six months. The Peninsula Qatar, December 11. Available online at: https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/11/12/2019/Qatar-to-develop-storage-facility-for-22-essential-items-for-atleast-six-months

The Peninsula Qatar. (2020a). 3 years of dignity and prosperity: Qatar achieves self-sufficiency in food sector. The Peninsula Qatar, June 5. Available online at: https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/05/06/2020/3-years-of-dignity-and-prosperity-Qatar-achieves-self-sufficiency-in-food-sector

The Peninsula Qatar. (2020b). Measures to reduce food waste stepped up. The Peninsula Qatar, February 15. Available online at: https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/15/02/2020/Measures-to-reduce-food-waste-stepped-up

The Peninsula Qatar. (2022). Hamad port plays vital role in national food security. The Peninsula Qatar, August 11. Available online at: https://thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/11/08/2022/hamad-port-plays-vital-role-in-national-food-security

The Voice of America. (2017). Iran, Turkey send food to Qatar amid fears of shortages. VOA News, June 11. Available online at: https://www.voanews.com/a/tillerson-cavusoglu-qatar/3895653.html

Winders, B., Heslin, A., Ross, G., Weksler, H., and Berry, S. (2015). Life after the regime: market instability with the fall of the US food regime. Agric. Hum. Values 33, 73–88. doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9596-9

Woertz, E., and Martínez, I. (2018). Embeddedness of the MENA in economic globalization processes. MENARA Project, Barcelona and Rome.

Keywords: sustainable food system, corporate food regime, food security, state-led capital, food policy

Citation: Mohamed A, Salmon C, Faizi B and Tok ME (2025) From crisis to resilience: food security policy development in Qatar. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1446264. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1446264

Edited by:

Enoch Kikulwe, Alliance Bioversity International and CIAT, KenyaReviewed by:

Amar Razzaq, Huanggang Normal University, ChinaMuhammad Abdul Kamal, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Mohamed, Salmon, Faizi and Tok. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdulfatah Mohamed, YWJkdWxtb2hhbWVkQGhia3UuZWR1LnFh

Abdulfatah Mohamed

Abdulfatah Mohamed Charlotte Salmon

Charlotte Salmon Bushra Faizi

Bushra Faizi M. Evren Tok

M. Evren Tok