- 1School of Business, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

- 2School of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Hubei University of Economics, Wuhan, China

Introduction: This study investigates the effect of shapes in food packaging graphics (SFPG) on consumer purchase intentions. While prior research has primarily focused on cross-modal associations between SFPG and other sensory modalities (e.g., taste, smell), the direct influence of SFPG on purchase behavior remains underexplored.

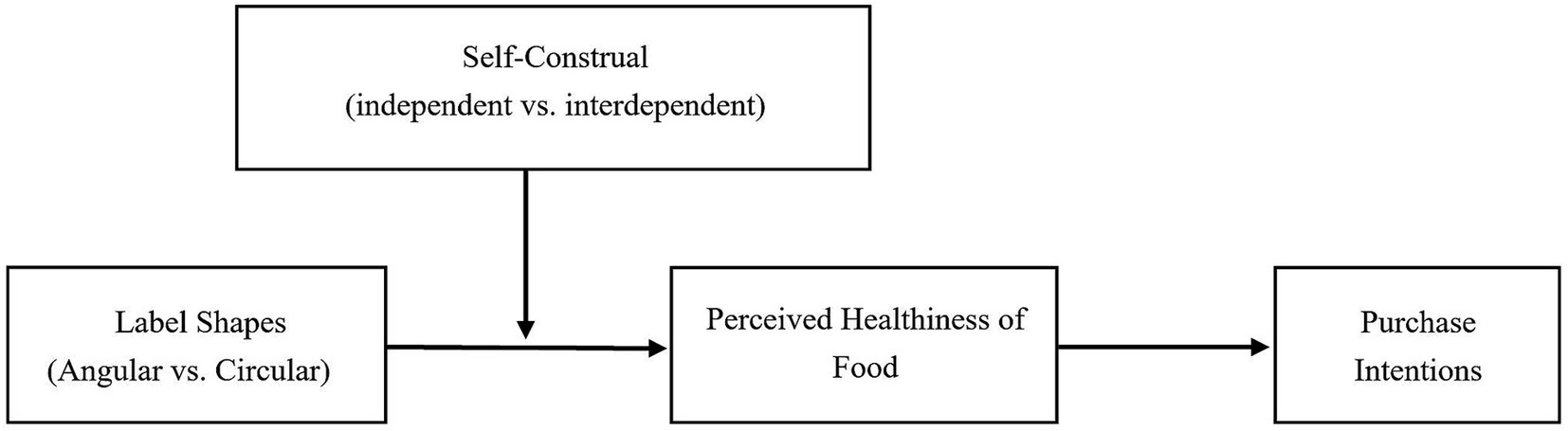

Methods: Three experiments were conducted to examine how SFPG influences perceived healthiness and purchase intentions. Experiment 1 compared the effects of angular vs. circular SFPG on consumer purchase intentions. Experiment 2 tested the mediating role of perceived healthiness in this relationship. Experiment 3 explored the moderating effect of self-construal (independent vs. interdependent) on the SFPG-purchase intention link.

Results: Results from Experiment 1 revealed that angular SFPG significantly enhanced purchase intentions compared to circular SFPG. In Experiment 2, perceived healthiness was found to mediate the relationship between SFPG and purchase intentions. Experiment 3 demonstrated that self-construal moderated the effect of SFPG on purchase intentions. Specifically, angular SFPG increased purchase intentions for individuals with an independent self-construal, whereas circular SFPG had a more significant effect for individuals with an interdependent self-construal. Additionally, the study rules out alternative explanations of visual salience.

Discussion: These findings offer a new perspective on how SFPG influences consumer decision-making, highlighting the role of perceived healthiness and self-construal in shaping purchase intentions. The results provide valuable implications for food packaging design and help businesses better position their products in the market and attract their target consumers.

1 Introduction

In the food economy, understanding how consumers make purchasing decisions is crucial because it directly affects market demand and supply chain management. The graphical design of packaging is crucial to consumer choice and purchase intention (Hamlin, 2016). Existing literature primarily emphasizes the cross-modal associations between shapes on food packaging graphics (SFPG) and other sensory modalities. Cross-modal associations refer to the interactions and connections between different sensory modalities, such as vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell (Spence, 2011). For instance, consumers may categorize circular, symmetrical, and less complex graphic shapes as sweet (and more pleasant tastes) while associating angular, asymmetrical, and more complex shapes with sourness (and less pleasant tastes) (Salgado-Montejo et al., 2015). The cross-modal associations between SFPG and other sensory modalities (such as taste and smell) in packaging design can significantly modulate consumers’ sensory expectations of product attributes. Specifically, angular flame icons increase expectations of spiciness, while circular flame icons enhance expectations of baked flavors (Gil-Pérez et al., 2019). Some studies have found that the cross-modal associations between (angular vs. circular) SFPG and colors, and wine aromas have no significant impact on consumers’ sensory matching or label preferences (Heatherly et al., 2019). However, other research indicates that in coffee packaging, angular shapes paired with green colors (perceived as more acidic) and circular shapes paired with pink colors (perceived as sweeter) better stimulate consumers’ purchase intentions and preferences (Sousa et al., 2020). This study primarily focuses on exploring the impact of SFPG on consumers’ purchase intentions, while considering the mediating role of perceived healthiness of food and the moderating role of self-construal, thereby addressing the gaps in existing literature on SFPG.

Shapes are generally categorized into angular and circular in individual contexts (Arnheim, 1974). Angular shapes are more frequently evaluated as angular, geometric, flat, hard, static, rough, sharp, restrictive, sour, cold, masculine, cold, and passive, whereas circular shapes are perceived as organic, rounded, soft, dynamic, fluffy, rigid, free, sweet, sensual, feminine, warm, and lively (Albertazzi et al., 2021). Moreover, research indicates a connection between angular (vs. circular) shapes and healthy (vs. unhealthy) foods (Wang et al., 2022). Thus, this study proposes that angular (vs. circular) SFPG enhances the perceived healthiness of food, thereby increasing individual purchase intentions. Furthermore, self-construal elicits individual goals and social orientations, influencing their psychology and decision-making (Aaker and Lee, 2001). For example, individuals in Japan often exhibit interdependent self-construal, where their identity is closely tied to their relationships and group memberships. In contrast, individuals in the United States typically display independent self-construal, defining themselves through personal goals and attributes. Therefore, self-construal moderates the effect of SFPG on individual purchase intentions. Specifically, for individuals with independent self-construal, angular (vs. circular) SFPG enhances purchase intentions; for those with interdependent self-construal, circular (vs. angular) SFPG enhances purchase intentions.

To better serve the practical and theoretical needs in the field of food economics, this paper makes the following three main contributions. Firstly, it explores the impact of SFPG on individual purchase intentions, addressing a gap in the existing literature that primarily focuses on the cross-modal associations between SFPG and other sensory modalities (such as taste and smell). Secondly, it enriches the study of perceived healthiness in the food consumption decision-making process by demonstrating that the effect of SFPG on individual purchase intentions is mediated by perceived healthiness, expanding the relevant research in this area. Finally, it extends self-construal to the food consumption decision-making process. This study finds that individuals with independent self-construal, and angular (vs. circular) SFPG enhance purchase intentions; for those with interdependent self-construal, circular (vs. angular) SFPG enhances purchase intentions, which further broadens the literature on graphic shapes. These findings not only provide a fresh perspective for understanding consumer behavior but also offer valuable insights for economic decisions in packaging design for food companies. They help businesses better position their products in the market and attract their target consumers.

2 Literature review

2.1 Food packaging

Packaging design is a crucial component of product marketing. Selecting appropriate packaging design elements can effectively communicate the perceived healthiness of food products to consumers and contribute to the success of a brand (Chrysochou, 2010). Previous research on food packaging design elements has primarily focused on three categories: informational elements, graphic elements, and structural elements. Specifically, informational elements refer to those that express the characteristics of the food, such as ingredients and nutritional content. Graphic elements pertain to the visual identity provided by the printed elements on the packaging, like shapes, colors, patterns, and fonts. Structural elements refer to those that give the product its form and texture, such as size, and material (Festila and Chrysochou, 2018). Other studies have divided food packaging into product information on the front of the package and ingredient information on the back, distinguishing between product-level credibility cues that describe the overall characteristics of the food and ingredient-level credibility cues that detail the food’s components (Baksi et al., 2017; Hieke and Taylor, 2012). Both types significantly influence consumers’ willingness to purchase healthy foods (Resano et al., 2018; Verbeke et al., 2013).

Therefore, this study focuses on the shape of graphic elements on the front of food packaging. Existing research in the field of marketing has shown that SFPG is crucial to consumer choices (Hamlin, 2016).

2.2 Angular/circular shapes

Shapes can generally be categorized as angular and circular (Arnheim, 1974; Liu, 1997). Similar to human beings, shapes possess distinct “personalities” (Arnheim, 1974; Colwell, 1975). Angular shapes (such as rectangles and triangles) are composed of straight lines and sharp angles, whereas circular shapes are characterized by curves and smoothness. The disparity between angular and circular shapes extends beyond their compositional elements to the symbolic meanings they convey (Arnheim, 1974). According to shape symbolism literature, angular shapes signify toughness, strength, hardness, and individuality, also symbolizing masculinity, severity, independence, and aggression, often perceived as fostering confrontational relationships between primary stimuli and the surrounding environment. On the other hand, circular shapes symbolize femininity, gentleness, softness, harmony, friendliness, and approachability, often perceived as fostering harmonious relationships between primary stimuli and the surrounding environment (Arnheim, 1974; Bar and Neta, 2006; Colwell, 1975; Jiang et al., 2016; Liu, 1997; Liu and Kennedy, 1993; Rompay et al., 2009; van Rompay and Pruyn, 2011; Zhang et al., 2006).

Furthermore, existing research indicates that angular and circular shapes play crucial roles in individual judgment and decision-making (Jiang et al., 2016; Maimaran and Wheeler, 2008; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhu and Argo, 2013). Previous studies have shown that the shape of a product itself, the shape of product containers (e.g., utensils, packaging, labels), and even any shapes inadvertently near the product can impact various aspects of individual behavior (Lynch and Zauberman, 2007). Previous research (e.g., Theo et al., 2015) suggests that the shape of brand designs impacts individuals’ perceptions of brand personality, with angular shapes enhancing perceptions of masculinity and circular shapes enhancing perceptions of femininity. Moreover, the shape of a logo not only affects individuals’ inferences about product attributes but also impacts their evaluations of the product manufacturer, with individuals believing that manufacturers using circular logos are more caring and customer-oriented than those using angular logos (Jiang et al., 2016).

Combining self-construal and shape literature, it has been found that angular-shaped logos are more attractive to individuals with independent self-construal (who form antagonistic relationships with others), while circular-shaped logos are more attractive to individuals with interdependent self-construal (who form harmonious relationships with others) (Zhang et al., 2006). Previous research on seating arrangements found that angular seating arrangements evoke a need for uniqueness (a desire to distinguish oneself from others), while circular seating arrangements evoke a need for belonging (a desire to connect oneself with others) (Zhu and Argo, 2013). Previous studies have also resolved this issue by mapping angular and circular shapes to the two basic dimensions of social judgment—warmth and competence. For example, research found that in fast-paced services, by adjusting physical environmental cues (such as shape cues) and social cues (such as busyness level), customer evaluations of service experiences can be effectively managed; specifically, angular (vs. circular) cues in service landscapes activate customers’ competence (warmth) associations, enhancing customer satisfaction by enhancing perceived provider competence in busy environments, while circular cues in non-busy environments enhance customer satisfaction by conveying warmth feelings, thus improving customer satisfaction (Liu et al., 2018). Circular logo shapes help enhance individuals’ green perceptions and thereby enhance green brand preference (Liu and Wei, 2021). The study found that there is a cross-modal association between the taste of liquids and shape, with angular shapes are associated with bitterness and thinness, while circular shapes associated with sweetness and voluminosity, indicating that certain taste characteristics may have sensory correspondences with corresponding shape perceptions rather than purely linguistic associations (Deroy and Valentin, 2011).

2.3 Perceived healthiness of food

Perceived healthiness of food refers to people’s overall cognition of the nutritional value, low-fat, and low-calorie content of food (Hagen, 2020). As a subjective cognition, the perceived healthiness of food often exhibits bias due to the general lack of individual ability to judge the healthiness of food accurately. The literature on the perceived healthiness of food primarily focuses on graphic shapes, individual cognition, and food types. Firstly, previous research has discussed that the perceived healthiness of food is significantly impacted by different types of graphic shapes, nutritional information, and individual nutritional knowledge. These factors can significantly alter individuals’ perceived healthiness of food and subsequently affect their purchase intentions (De Temmerman et al., 2021; Jürkenbeck et al., 2022). Furthermore, food labels claiming low (vs. high) calories lead to higher (vs. lower) perceived healthiness of food and lower (vs. higher) satiety (Watson et al., 2020). Additionally, previous research (e.g., Leila et al., 2024) has found that individuals generally hold a positive attitude toward Traffic Light Labeling (TLL) and tend to perceive foods with green TLL labels as healthier.

Secondly, the perceived healthiness of food is significantly affected by individual nutritional cognition and food categories. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of nutritional knowledge are more likely to recognize the close relationship between health and diet and therefore are more inclined to try functional foods containing healthy ingredients such as fiber or antioxidants. In contrast, individuals with lower nutritional knowledge may hold conservative attitudes toward these products, affecting their perceptions of food healthiness (Ares et al., 2008; Bech-Larsen and Grunert, 2003). Lastly, previous research has shown that consumers tend to favor aesthetically pleasing foods because they perceive them as more natural and healthier (Hagen, 2020). However, recent studies have found that “ugly” labels can correct consumers’ negative expectations of unattractive produce, thereby increasing their purchase intentions and providing a new approach to reducing food waste (Mookerjee et al., 2021). Additionally, other research indicates that individuals believe food types and brand-related cognitive factors play important roles in judging the perceived healthiness of food. Individuals think of ultra-processed foods as less healthy and believe that healthy snacks contain fewer calories, leading to enhanced consumption (Hässig et al., 2023; Provencher et al., 2009; Provencher and Jacob, 2016).

In summary, consumers are increasingly valuing the perceived healthiness of food in their purchasing decisions. The design elements of food packaging, particularly graphic shapes, significantly impact consumers’ perception of food healthiness. This perceived healthiness, in turn, greatly influences consumers’ purchase intentions. Therefore, shapes, as crucial design elements on packaging graphics, effectively influence consumers’ purchase decisions by shaping their perceived healthiness of food.

2.4 Self-construal

Self-construal is the perception and understanding of one’s relationship with others and the surrounding world (Kitayama et al., 1997; Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Self-construal comprises two aspects: independent self-construal, which emphasizes personal autonomy, self-reliance, and uniqueness, and interdependent self-construal, which focuses on social connections, group harmony, and relationships with others (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). At the sociocultural level, self-construal is highly related to individualism and collectivism, depicting individual differences shaped by social values and normative orientations (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Oyserman et al., 2002). Individualistic cultures prioritize independence, autonomy, and personal achievement. In contrast, collectivistic cultures prioritize interdependence, social harmony, and group goals (Singelis and Brown, 1995). Additionally, self-construal has been shown to impact various aspects of social cognition and behavior, such as interpersonal communication, decision-making (Markus and Kitayama, 1991), and prosocial and antisocial behaviors (Simpson et al., 2018). Previous research indicates that constructivist self-cognition is a dynamic, non-continuous, and non-essentialist view of self, exhibiting consistency in multicultural contexts, especially within Buddhist collectivist cultures. This provides new perspectives and directions for self-cognition research (Ge et al., 2021).

2.5 The effect of SFPG on purchase intentions

Information on food packaging such as food labels serves as an essential source for consumers to obtain nutritional information about food (Schoonbrood and Delarue, 2024), and is directly related to the perceived healthiness of food. It plays a significant role in consumers’ evaluation of food healthiness (Bialkova et al., 2013). Currently, scholars have extensively studied the impact of food label characteristics on perceived healthiness, with common features including label color (Shen et al., 2018), imagery (Miklavec et al., 2021), nutritional content labeling (Sütterlin and Siegrist, 2015), information expression (Mohr et al., 2012), information presentation style (simple vs. complex) (Andrews et al., 2011), and typography (Karnal et al., 2016). Thus, shapes on packaging graphics, as a characteristic of food packaging information, are also a subjective perception. The perceived healthiness of food is influenced by this feature.

Existing research from the fields of cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and sensory marketing has provided empirical evidence demonstrating a connection between angular (vs. circular) shapes and healthy (vs. unhealthy) foods (Wang et al., 2022). Some research indicates consumers are prone to be influenced by the shape of a product (angular versus circular) (Vallen et al., 2019). For instance, studies have shown that the consistency between brand name pronunciation and dessert shapes can enhance persuasiveness, but circular dessert shapes may hinder this consistency effect, reducing brand appeal and purchase intentions. Previous research (e.g., Kim, 2016; Spears et al., 2016) has also tested that angular shapes on food packaging, compared to circular graphic shapes, convey more vitality and energy, thereby increasing hunger and appetite. In addition, cross-modal strategies have been proven useful in food research. For example, a study aimed to investigate whether cross-sensory strategies could alter sweetness perception across different age groups (young, middle-aged, and elderly) found that the effects of cross-sensory interactions were similar across all age groups (Romeo-Arroyo et al., 2024). The mentioned studies collectively confirm the association between angular (vs. circular) shapes and concepts of healthy eating. Existing research has indicated that the stronger people’s perception of the healthiness of food, the stronger their intention to purchase (Steinhauser et al., 2019).

Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Angular (vs. circular) SFPG can enhance individuals' purchase intentions.

H2: Perceived healthiness of food mediates the impact of angular (vs. circular) SFPG on purchase intentions.

2.6 The moderating role of self-construal

Individuals with interdependent self-construal tend to think and interact with groups or strengthen existing relationships (Cross et al., 2010), emphasizing harmonious social values (Millan and Reynolds, 2014). In contrast, individuals with independent self-construal tend to focus on their inner attributes or characteristics (Spassova and Lee, 2013). Individuals with interdependent self-awareness tend to adhere to social or group norms and rely on others’ information, while those with independent self-awareness prefer their inner thoughts and follow their emotions (Zhang and Shrum, 2009).

Circular shapes symbolize femininity, gentleness, harmony, and approachability, often perceived as fostering a harmonious relationship with the surroundings; angular shapes represent toughness, strength, and individuality, symbolizing masculinity, severity, and aggression, often seen as creating a confrontational relationship with the surroundings (Arnheim, 1974; Bar and Neta, 2006; Colwell, 1975; Jiang et al., 2016; Liu, 1997; Liu and Kennedy, 1993; Rompay et al., 2009; van Rompay and Pruyn, 2011; Zhang et al., 2006).

Previous research has found that individuals with independent self-construal prefer angular shapes, while those with interdependent self-construal prefer circular shapes due to different “conflict resolution styles.” Chinese scholars have also proposed that the preference for independent (vs. interdependent) self-construal for angular (vs. circular) brand logos is due to different needs for uniqueness (Wang et al., 2017). Both studies confirm that individuals with independent self-construal prefer angular shapes, while those with interdependent self-construal prefer circular shapes. Additionally, previous research (e.g., Escalas and Bettman, 2005). Suggests that having internally consistent imagery can enhance the connection between individuals and brands, meaning that individuals with independent (vs. interdependent) self-construal evaluate angular (vs. circular) brand logos more favorably.

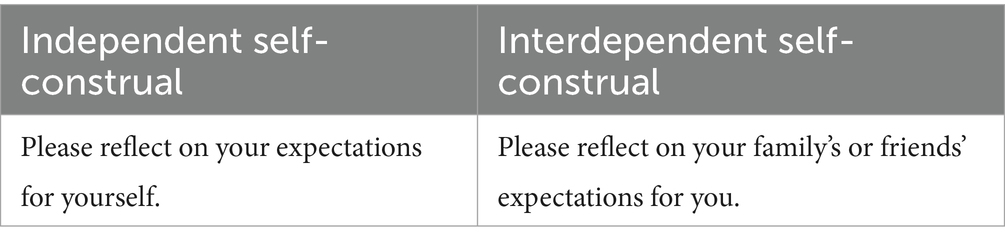

The previous research indicates that individuals with independent self-construal prefer angular shapes, thus angular label shapes can enhance their purchase intentions. Conversely, individuals with interdependent self-construal prefer circular shapes, leading to higher purchase intentions for products labeled with their preferred circular shapes. Thus, we selected self-construal as a moderator variable to explore how it influences the relationship between SFPG and purchase intention, which enriches research on the impact of individual differences on decision-making within consumer behavior theory. In summary, combining packaging metaphors and shape symbolism literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Self-construal moderates the impact of SFPG on individual purchase intentions. Specifically, for individuals with independent self-construal, angular (vs. circular) SFPG enhances purchase intentions; for individuals with interdependent self-construal, circular (vs. angular) SFPG enhances purchase intentions.

The conceptual model for hypotheses is shown in Figure 1.

3 Materials and methods

The study included three experiments aimed at investigating the impact of SFPG on consumers’ purchase intentions. Detailed descriptions of the measurement items and an overview of the experiments can be found in Appendixes A, B. This study utilized SPSS version 25 and PROCESS version 3.5 for statistical analyses, focusing on mediation effects.

3.1 Experiment 1

Experiment 1 aimed to verify the influence of angular (vs. circular) SFPG on purchase intention using real brand bread (healthy food and necessities) (H1). Our manipulation of graphic shapes uses a rectangular label for the angular group and a circular label for the circular group (Jiang et al., 2016). Additionally, we measured product familiarity (Mead and Richerson, 2018; Schoonbrood and Delarue, 2024) and product preference (Cowart et al., 2008), excluding the exclusion explanations of product familiarity and product preference.

3.1.1 Experimental design and participants

Experiment 1 employed a single-factor two-level design (SFPG: angular vs. circular). A total of 258 participants were recruited through a professional survey platform. The average age of the participants was 32.72 years (SD = 10.768), with 167 female participants, accounting for 64.7% of the total sample.

3.1.2 Experimental procedure

The experiment was conducted online, and participants received monetary compensation upon completing all the items. The real brand “Huiyou,” a famous bread brand in China (see Figures 2, 3), was used as the stimulus to closely mimic a real-world scenario. We adopted the presentation style of products and product information from online shopping platforms like JD.com and Taobao. Specifically, we placed the image of the food item on the left side of the screen and the food information on the right, allowing consumers to see the food details. Additionally, we provided more comprehensive food information to the participants, including the ingredients list, shelf life, production license, and nutritional facts table. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups (SFPG: angular vs. circular). Each participant was presented with images of whole wheat bread packaging and product information. Participants in the angular shape group saw angular graphic shapes, while those in the circular shape group saw circular graphic shapes. All other information was identical across both groups.

After viewing the images, participants answered three questions regarding their purchase intention: “I will consider buying this whole wheat bread,” “I am very likely to buy this whole wheat bread,” and “I will buy this whole wheat bread” (Cronbach’s α = 0.79) (Sweeney et al., 1999). Subsequently, participants rated product familiarity and product preference. All scales used were 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Finally, participants answered demographic questions.

3.1.3 Experimental results

Manipulation test. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the manipulation of shapes. The results indicated that the sharpness perception reported by the angular shapes group (M = 4.98, SD = 0.910) was higher than that of the circular shapes group [M = 4.03, SD = 0.627, F(1, 256) = 94.166, p < 0.001], and η2 = 0.2688. These findings indicate that the shape manipulation in Experiment 1 was effective.

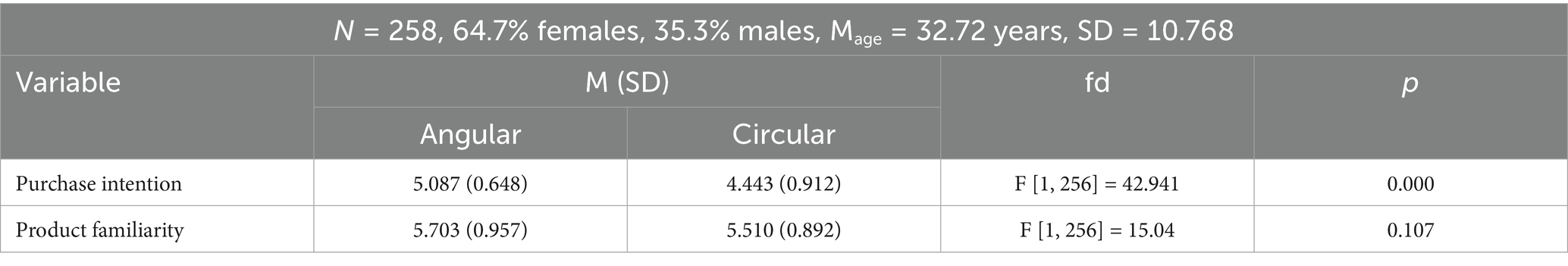

Purchase intention. The results of a one-way ANOVA indicated that participants in the angular shape group (M = 5.087, SD = 0.648) exhibited a greater intention to purchase the bread compared to participants in the circular shape group [M = 4.443, SD = 0.912, F(1, 256) = 42.941, p < 0.001], and η2 = 0.1432, supporting H1 (see Table 1).

Exclusion explanations. The results of a one-way ANOVA indicated that there was no significant difference in product familiarity between participants in the angular shape group and the circular shape group (p > 0.06). When controlling for preference, we found that fondness did not significantly influence purchase intentions [F(1, 256) = 0.45, p = 0.502]. This suggests that while participants may have a general preference for whole wheat bread, this preference does not drive their purchase intentions in the context of our study. Consequently, we could exclude the influence of product familiarity and product preference (see Table 1).

3.1.4 Experimental discussion

Experiment 1 verified the effect of angular (vs. circular) SFPG on purchase intention (H1). In contrast to experiment 1 using healthy food (necessities), experiment 2 would replace the stimuli with unhealthy food (non-necessities) to further validate H1, thereby eliminating the potential influence of healthy food (necessities) on experimental outcomes. While Experiment 1 excluded the alternative explanation of product familiarity, previous research has indicated the interference of product information richness (Janina et al., 2018) and product transparency on purchase intention (Cheng et al., 2018); these influences will also be excluded in the next experiment. In Experiment 1, the entire food label shape was utilized. Subsequent experiments would employ the shape of the food label itself to further validate the influence of graphic shapes on purchase intention.

3.2 Experiment 2

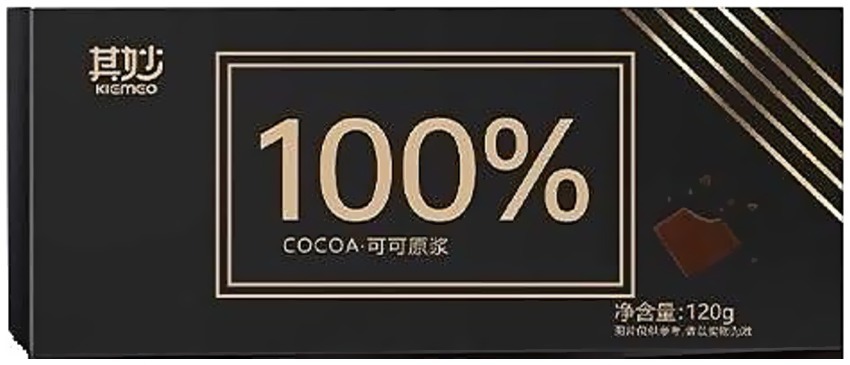

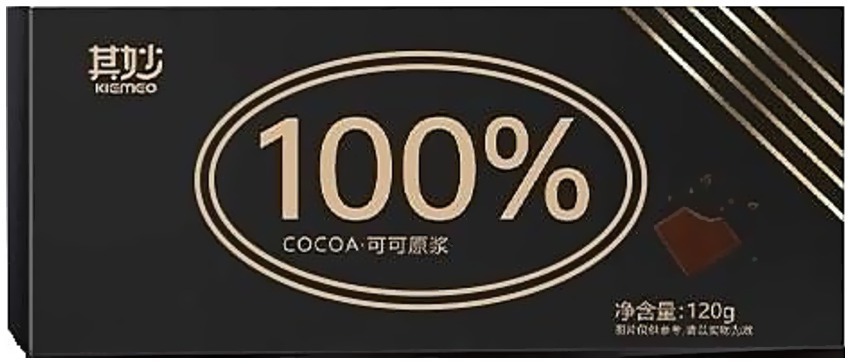

Experiment 2 aimed to verify the mediating role of perceived healthiness of food in the effect of SFPG on purchase intentions (H2), utilizing unhealthy food (non-necessities; real brand chocolate), using opaque packaging, and eliminating the effect of product transparency (Cheng et al., 2018). Meanwhile, to eliminate the influence of product information richness (Janina et al., 2018), this experiment uses stimuli with minimal product information. Additionally, product evaluation can serve as a proxy for purchase intentions. Therefore, Experiment 2 employs a product evaluation scale (Förster, 2004) to measure purchase intentions, thereby enhancing external validity and increasing generalizability. This experiment also measures perceived product innovativeness (Rogers et al., 2014; Stock and Zacharias, 2013) to rule out exclusion explanations. The shape manipulation in this experiment differs from Experiment 1, where the entire label shape was used, whereas Experiment 2 focuses on SFPG.

3.2.1 Experimental design and participants

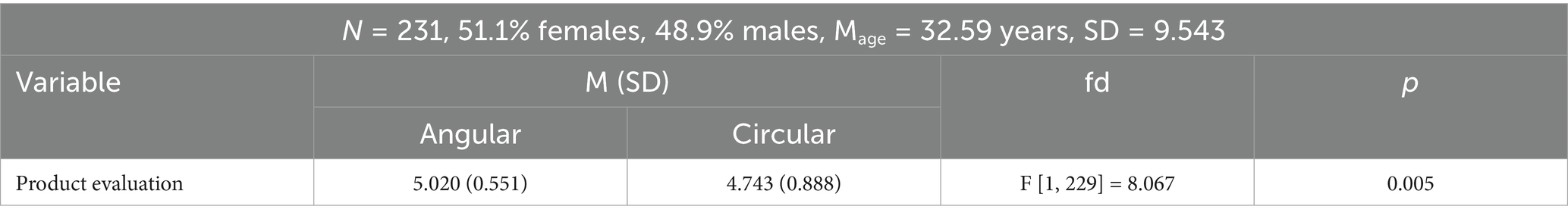

Experiment 2 employed a single-factor two-level design (SFPG: angular vs. circular). A total of 231 participants were recruited through a professional survey platform. The average age of the participants was 32.59 years (SD = 9.543), with 118 female participants, accounting for 51.1% of the total sample.

3.2.2 Experimental procedure

Similar to experiment 1, experiment 2 was also conducted online, and participants received monetary compensation upon completing all the items. The real brand “Wonder,” a famous chocolate brand in China (see Figures 4, 5), was used as the stimulus to closely mimic a real-world scenario. We adopted the presentation style of products and product information from online shopping platforms like JD.com and Taobao. First, participants were informed that a chocolate manufacturer was about to launch a new chocolate product and wanted to gauge consumer attitudes toward the product before its official release. Next, participants were shown an image of the product information for the chocolate and were told that this was a screenshot of the product information on the chocolate’s packaging. The product information included the product name (Wonder), product specifications (120 g), nutrition label (100% COCOA Cocoa Extract), and a disclaimer (Image for reference only; please refer to the actual product). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups (SFPG: angular vs. circular). Each participant was presented with images of the chocolate packaging and product information. Participants in the angular shape group were shown graphic shapes with angular shapes, while those in the circular shape group were shown labels with circular shapes. All other information was identical across both groups.

After viewing the images, participants answered questions regarding their perceived healthiness of food and product evaluation. Two items were used to assess the perceived healthiness of food: “I believe this product keeps me healthy,” and “I believe the healthiness of this product is very important” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) (α = 0.70) (Roininen et al., 1999; Steptoe et al., 1995). Three items were used for product evaluation (α = 0.83). Following the items used in the same method in Experiment 2 (Förster, 2004), participants rated their agreement with three statements: “I am satisfied with this chocolate,” “This chocolate is appealing to me,” and “I rate this chocolate highly.”

Participants then completed a scale to assess perceived product innovativeness, with all scales using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The shape manipulation was similar to that in experiment 1. Finally, participants answered demographic questions.

3.2.3 Experimental results

Manipulation test. An ANOVA was conducted to examine the manipulation of shapes. The results indicated that the sharpness perception reported by the angular shapes group (M = 5.09, SD = 1.146) was higher than that of the circular shapes group [M = 4.07, SD = 0.931, F(1, 229) = 55.402, p < 0.001]. These findings indicate that the shape manipulation was effective.

Product evaluation. A one-way ANOVA showed that participants in the angular shape group (M = 5.020, SD = 0.551) had a higher product evaluation for the chocolates than those in the circular shape group [M = 4.743, SD = 0.888, F(1, 229) = 8.067, p = 0.005]. While Experiment 2 focused on product evaluation using statements such as “I am satisfied with this chocolate” and “This chocolate is appealing to me,” the results indicate that angular SFPG positively influenced these evaluations. Although this experiment did not directly measure purchase intention, previous research suggests that positive product evaluations are strong predictors of future purchase behavior. Therefore, it can be inferred that angular SFPG may indirectly promote purchase intention by enhancing product appeal and satisfaction. This suggests that angular SFPG promotes purchase intention, validating H1 (see Table 2).

Mediation of perceived healthiness of food. We employed the bootstrapping method in Process (Model 4; Hayes, 2013) to verify the mediating role of perceived healthiness of food between SFPG and purchase intention. The SFPG was used as the independent variable, purchase intention as the dependent variable, and perceived healthiness of food as the mediating variable. The number of bootstrap samples was set to 5,000, with a confidence interval of 95%. The results indicated that when the SFPG was angular, it increased the perceived healthiness of food (β = 0.3271, SE = 0.1065, t = 3.0726, p = 0.0024). Perceived healthiness of food positively influenced purchase intention (β = 0.2242, SE = 0.0590, t = 3.8013, p = 0.0002). The direct effect of SFPG on purchase intention is not significant (β = 0.2044, SE = 0.0970, t = 2.1076, p = 0.0362). Additionally, the indirect effect of the angular SFPG on purchase intention was significant, with a confidence interval that did not include zero (β = 0.0733, SE = 0.0337, LLCI = 0.0192, ULCI = 0.1489), indicating that the mediating effect was significant. Thus, H2 was supported.

Exclusion explanations. The results of a one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference between participants in the angular shape group and the circular shape group in their evaluation of food innovativeness (p > 0.06). Thus, we ruled out the influence of food innovativeness.

3.2.4 Experimental discussion

Experiment 2 replicated the finding that angular SFPG can increase purchase intention. Moreover, it examined the mediating role of the perceived healthiness of food in this effect. Experiment 2 significantly enhanced the validity of the experiment by presenting less food information and using unhealthy food (non-necessities) with opaque packaging as stimuli. Additionally, potential explanations related to perceived product innovativeness were ruled out. This experiment also confirmed that the effects of the entire food label shape and the SFPG were consistent, indicating that angular SFPG increased purchase intention.

3.3 Experiment 3

Experiment 3 aimed to examine the moderating effect of self-construal on the impact of SFPG on individuals’ purchase intention (H3). Since Experiments 1 and 2 utilized real brands and solid food items as stimuli, to eliminate the influence of existing brands on purchase intention, Experiment 3 employed virtual brands of liquid food items (drinks) as stimuli. Additionally, to enhance internal validity, a new scale (Chen and Kim, 2013; Teresa et al., 2006) was used to measure purchase intention as the dependent variable.

3.3.1 Experimental design and participants

This experiment employed a 2-factor (SFPG: angular vs. circular) × 2 (self-construal: interdependent vs. independent) between design. A total of 402 EMBA students from a university in southern China participated in the online experiment by completing a survey link, with an average age of 31.87 years (SD = 8.379). Among them, 192 participants were female, accounting for 47.8% of the total sample. Participants received monetary compensation upon completing all items.

3.3.2 Experimental procedure

The virtual juice brand “Joy” was used as the stimulus to closely mimic a real-world scenario (see Figures 6, 7). We adopted the presentation style of products and product information from online shopping platforms like JD.com and Taobao. In this experiment, the juice packaging featured the brand logo and brand name. On the left side of the presented display, product information was shown, which included the product name (Blueberry Juice), fruit juice content (100% NFC), and net quantity (320 mL). Central information, comprising the shelf life (4 months), country of origin, production license, and company website, was also included. On the right side, ingredient information was detailed, including the ingredients list, storage instructions, barcode, and nutritional label. Participants were randomly and evenly assigned to four experimental groups. They were informed that the experiment consisted of two unrelated parts.

Figure 7. Juice with circular shapes on food packaging graphics.

Shichang Liang

Shichang Liang Yizheng Zhou1

Yizheng Zhou1 Qiuju Qin

Qiuju Qin Jingyi Li

Jingyi Li