- 1School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

- 2Nutrition Opportunities Worldwide, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Agricultural Sciences, Africa University, Mutare, Zimbabwe

Background: Africa has a triple burden of malnutrition. The private sector can affect the nutritional status of the population. To improve nutrition, civil society and development agencies are developing initiatives to engage these actors. The objectives of this study were to (a) identify and describe these initiatives and (b) understand their successes and challenges.

Methods: An exploratory research design, including an online search, the author’s knowledge, and generative artificial intelligence, was used to develop a list of potential nutrition initiatives. Publicly available data on these initiatives was included in an Excel template. Initiatives with a nutrition focus were shortlisted using an inclusion and exclusion criterion. In-depth review of data and semi-structured interviews were conducted with shortlisted nutrition initiatives for further insights.

Results: Forty-eight initiatives were identified. Of these, twenty-four were multi-country with African presence, and twenty-four were Africa-only. Eight initiatives were shortlisted for in-depth review. Three more were added based on advice from an interviewee. Most initiatives were founded between 2011 and 2015. Private sector actors of varied sizes, operating in diverse food value chains, were engaged by the lead agencies. However, these actors were focused on food processing and manufacturing, with only some initiatives engaging the food retailers. The civil society and development agencies worked with the private sector through convening meetings, collaboration on projects, capacity building through training, and encouraging the private sector to make public commitments and monitoring them. Frequently reported initiative successes included an increased recognition by governments on the need to engage with the private sector on nutrition improvements. Frequently shared challenges were limited resources (financial and human) and an unclear business rationale to invest in nutrition. Key recommendations for the future were to ensure an appropriate structure with the right partners, an aligned vision, a robust governance process, and regular communication.

Conclusion: Multi-country initiatives led by civil society organisations or development agencies are engaging the private sector to improve nutrition in Africa. These initiatives operate using different approaches to influence private sector actions. This study fills an important knowledge gap by identifying and describing such initiatives and presenting their successes and challenges for future initiatives design and execution.

1 Introduction

Food has been recognized as a human right since 1948, when it was included in Article 25 of the United Nations (UN) Declaration of Human Rights. However, this has not solved the ongoing problem of food insecurity, hunger, and malnutrition. In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were set by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), with SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) focused on ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition (UNGA, 2015), without which none of the other SDGs can be achieved (Lile et al., 2023). Not only is the elimination of hunger a key element for good health, but it is also a crucial element in the economic growth and development of countries (Unicef, 2023).

Despite these global efforts, the number of people globally affected by hunger and malnutrition is still high. The State of Food Insecurity and Nutrition in the World 2024 (SOFI) estimated that between 713 and 757 million people may have faced hunger, which is approximately 1 out of 11 people in the world (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO et al., 2024).

Many countries in Africa continue to face widespread malnutrition for several reasons, including limited food availability, lack of access to and unaffordability of healthy diets, unhealthy food environments, etc., which is further exacerbated by conflicts, economic slowdowns, and high and persistent inequality. Five years from 2030, malnutrition is still on the rise in Africa, with 20.4 percent of the population undernourished. One out of every five people were reported to be undernourished in 2023 (298.4 million people). It is projected that more than half of the 582 million people who will be chronically undernourished at the end of the decade (2030) will be in Africa (World Health Organization, 2024). Additionally, anaemia affects an estimated 40.4 percent of women of reproductive age, 13.7 percent of infants have a low birth weight, among children aged under 5 years, the average prevalence of overweight is 5.3 percent, stunting is 30.7 percent, and wasting is 6.0 percent. The adult population also faces a malnutrition burden: an average of 10.0 percent and 9.0 percent of adult (aged 18 and over) women and men live with diabetes, and 20.8 percent of women and 9.2 percent of men live with obesity (Development Initiatives, 2022).

A healthy diet is critical to achieving and sustaining adequate nutrition. Food and drink, the mainstay of the diet, are primarily provided by a broad range of private sector actors across Africa. Thus, the private sector has an important role to play in ensuring food supply chains and environments are delivering healthy diets (Levine and Kuczynski, 2009). Indeed, diverse private sector actors, including micro-small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), not just food and beverage companies, have considerable potential to ensure that food systems and environments are providing nutritious foods. Furthermore, these private sector actors have significant power across the food system, with involvement in almost all aspects of the production, processing, distribution, marketing, and sale of food and beverages that consumers eat and drink every day (Dukeshire, 2013; Clapp, 2017; Fanzo et al., 2020; Nduhura et al., 2022; Smyth et al., 2021; Aseete et al., 2023). Recognising the significant involvement and power of diverse private sector actors across the food system, the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement started in 2010, emphasising the need to establish multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs). It encouraged the governments, United Nations (UN) agencies, and civil society organisations (CSOs) to strategically and tactically engage various private sector actors to improve global food security and nutrition (Scaling Up Nutrition, 2025).

In recent years, MSIs led by civil society and development agencies have emerged as potential mechanisms for transforming food systems and improving nutrition. These initiatives are increasingly being developed in alignment with global guidelines and frameworks that promote inclusive and sustainable approaches to food system change (UNDP, 2023; Lie and Granheim, 2017; Food Forward NDCs, 2024; UNEP, FAO and UNDP et al., 2023).

A growing collection of literature has begun to explore and analyse these efforts. A 2024 study identified 30 MSIs involved in food system transformation (Van Den Akker et al., 2024), while another examined the influence of ultra-processed food corporations within multi-stakeholderism, cataloguing 45 relevant initiatives (Slater et al., 2024). Earlier documentation includes a 2011 inventory of 18 multi-stakeholder sustainability alliances in the agri-food sector (Dentoni and Peterson, 2011). Further, a 2018 report by SustainAbility and WWF assessed how MSIs addressing sustainable food systems and diets operate across different stakeholders, commodities, issues, and geographies, identifying critical gaps and offering recommendations for future action (Harvey and Trewern, 2018).

The High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) provided, in its June 2018 report, a comprehensive list of institutions, programs, and MSIs, including those based in Africa. The report recognises that MSIs have emerged quite recently as a topic mobilizing scientific communities beyond social sciences and that such communities are still small. Evidence and data are limited in time and scope and quickly evolving. It reported that it is difficult to find detailed and publicly available data on existing MSIs. The report identified five main domains of intervention for MSIs: (i) knowledge co-generation and capacity building; (ii) advocacy; (iii) standard setting; (iv) action; and (v) fundraising and resource mobilization. It also recognises that MSIs face major challenges and limitations in the realization of their potential, such as tensions among partners because of mistrust or diverging views in various areas. Tensions can also be generated by conflicts of interest in the MSI and power asymmetries (HLPE on Food Security and Nutrition, 2018).

Emerging evidence from developing countries further enriches the understanding of MSIs in practice. One study explored eighty-nine multi-stakeholder platforms across Bangladesh, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, identifying enabling conditions and bottlenecks that influence their effectiveness in addressing food and nutrition security. The noted bottlenecks were—lack of awareness among stakeholders on healthier diets, weak connections between the private sector and the initiative, poor collaborations between MSIs, poor leadership, etc. (Herens et al., 2022). In addition, country-level reports from Bangladesh, Kenya, Mali, Nepal, and Rwanda provide practical insights and recommendations for designing, implementing, and monitoring MSIs aimed at transforming food systems and improving nutrition (USAID, 2016; SUN, 2023; Kar, 2014; Gaihre et al., 2019; Initiative, 2016; Rural21, 2019).

Within Africa, the evidence on MSIs engaging farmers is also expanding. A 2021 systematic review documented knowledge co-creation processes within MSIs in sub-Saharan Africa. The study noted some positive results of what MSIs could achieve, including increased yields and income for farmers, policy, regime, and institutional changes, and changes in environmental sustainability. Several limitations were also reported, including limited attention for scaling up and a lack of sustainability due to dependency on donor funding. It also noted limitations related to the evidence base on MSIs (Van Ewijk and Ros-Tonen, 2021). Another study assessed the feasibility of generating timely and reliable evidence on the effectiveness of MSIs as drivers of agri-food system transformation. It illustrated the challenges and progress of MSIs in achieving their intended outcomes by using initiatives such as Bonsucro and the Farm to Market Alliance (FtMA) as examples. Challenges like managing multiple short-term pressures, such as creating the right governance structures, supporting an enabling environment for collaboration, and demonstrating accountability to funders, were noted for FtMA (Thorpe et al., 2022).

Despite this growing body of evidence on MSIs for food system transformation, there remains a gap in research on nutrition initiatives led by civil society and development agencies engaging the private sector in Africa. Understanding how these agencies engage and influence the private sector to promote more focus on nutrition is crucial for forming similar future initiatives. Therefore, this study seeks to identify and define civil society and development agencies-led initiatives aimed at influencing private sector actions to improve nutrition in Africa and to understand their successes and challenges for consideration by future initiatives. Two key questions that this study aims to address are:

1. What are the major initiatives through which civil society and development agencies engage with the private sector to improve nutrition across Africa?

2. What are their key successes and challenges that can inform the design of future nutrition-focused initiatives?

2 Methods

2.1 Identification of nutrition-focused initiatives

A search strategy to identify potential initiatives was developed using the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018), the online template from Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries, and through discussions with researchers at Tufts University. Since the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, launched in 2010, had inspired a new way of working collaboratively with the private sector to end malnutrition, initiatives established after 2010 till March 2024 were included. An initial scan to identify the initiatives was done using the search term ‘multistakeholder initiatives for food and nutrition’ on Google. The first 10 pages were screened for relevance by reviewing the titles, as the following pages did not provide any added data. This approach was used to identify any existing literature or reports on civil society and development agencies-led initiatives engaging the private sector to improve nutrition. Through this search, we identified a review conducted by the World Wildlife Fund (Harvey and Trewern, 2018). This reference was used to begin the identification of potential nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector in Africa.

A secondary search was conducted using the study protocol as guidance on the Summons discovery service at the University of Reading, U.K. This provides a comprehensive search across a wide range of library resources, including e-books, journal articles, newspaper articles, and more, through a single search box (University of Reading, 2025). For the search in Summons, 18 search terms were used as shown in Annex I. This search resulted in 62 peer-reviewed articles. Titles of these articles were reviewed for relevance, and 17 articles were shortlisted for abstract review. After removing duplicates, 11 full-text publications were reviewed to identify relevant initiatives.

An additional Google search was conducted using the search term ‘multi stakeholder nutrition.’ The first one hundred titles were reviewed for relevance, as no additional data was being identified thereafter. This search identified a further 29 articles and reports, which had some data on multi-stakeholder initiatives. Few initiatives were included based on the author’s knowledge of this field. Generative artificial intelligence (Chat GPT) was also used to complement the search and identify additional initiatives. The list of questions used in Chat GPT is provided in Annex I.

If any initiative included a nutrition topic, it was added to the list of initiatives. Once the list of potential nutrition initiatives was ready, detailed data from online documents was reviewed and added to a pre-designed Excel template. The completed Excel template is included in Annex II.

2.2 Shortlisting of nutrition-focused initiatives

Potential initiatives included in the list were screened using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion:

• Led by civil society alone or civil society with support from development agencies.

• Large scale, with an emphasis on Africa.

• Primary focus: Influencing private sector actions for improving nutrition.

• Private sector actors engaged: Food processors, manufacturers, retailers.

Exclusion:

• Initiatives led only by the private sector for lobbying purposes (for example, trade associations).

• No African presence.

• Primary focus: Agriculture, emergency food relief, or promoting nutrition activities mandated by the government (for example, food fortification).

• Private sector actors engaged: input suppliers and farmers

This study was part of a larger project—The Food Prices for Nutrition, which shows how the cost and affordability of healthy diets can be used to monitor food access and guide intervention (Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, 2025). Since the project focused specifically on ‘Nutrition’, only initiatives with a direct nutrition-related approach were included. Initiatives targeting food production and working with farmers were excluded, as their main objective was to boost production and resilience among farmers. Even when nutrition was part of some initiatives, it was aimed at the farmers themselves rather than consumers in the market.

Once the shortlist of 11 initiatives was created, an additional search of the initiatives’ websites, publications, project reports, and monitoring and evaluation frameworks was conducted. Any additional data identified was added to the Excel template (Annex II).

2.3 Key informant interviews and analysis

A qualitative interview template was developed, and a mock interview was conducted with an expert at Tufts University before the submission and approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University (Annex III). The authors agreed that the interviews would be iterative and used the template for guidance purposes only.

The key individuals from civil society and development agencies who were identified for the shortlisted initiatives were approached via LinkedIn or email (June 2024) to confirm their interest and availability for an interview and discuss their initiative in detail. The interview questions were shared in advance so that the contacted representative could recommend the best person within the organisation to answer the questions. Interviews with private sector representatives from the shortlisted initiatives were not conducted, as a separate agency was handling that work as part of a parallel project.

One initiative declined to participate, and no response was received from another initiative. Nine semi-structured virtual interviews were conducted between June and July 2024. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The transcripts were used to create a summary of responses to the interview questions. All interview transcripts and notes were anonymized and stored in secure files for data confidentiality. The interviews provided an opportunity for an in-depth understanding of the initiative.

A thematic analysis was conducted to analyse the interview data on factors contributing to the development and function of the initiatives. Data from the interview transcripts was read and re-read by the authors to become familiar with the content. The authors highlighted meaningful segments of data and labelled them in three overarching themes: successes, challenges, and recommendations, aligned with the interview questions. Each sentence in the interview transcript was reviewed and color-coded to identify sub-themes within the three overarching themes. Five sub-themes were identified for success and challenges, respectively, and eight sub-themes were identified for recommendations. The sub-themes for successes and challenges are arranged in descending order, with the most frequently mentioned appearing at the top.

To minimize bias and validate the accuracy of the findings, one author coded the in-depth interview data on success and challenges for all shortlisted initiatives, and another author coded data on recommendations. An independent review of the data coded by both authors was conducted by the third author. Any disagreements among authors were resolved through discussions. Data from the interviews was cross-validated and triangulated with data from websites and other descriptive documents for similarities and differences.

3 Results

3.1 Nutrition-focused initiatives: identification and description

We identified 3 potential initiatives from the review by Harvey and Trewern (2018). No additional nutrition initiatives were identified through Summons. 11 initiatives engaging the private sector for improving food security and nutrition were identified through a secondary online search. A further three initiatives were added based on the author’s knowledge of the field. Thirty-one additional initiatives were identified using generative artificial intelligence. A total of 48 potential nutrition initiatives were identified and added to the Excel template provided in Annex II.

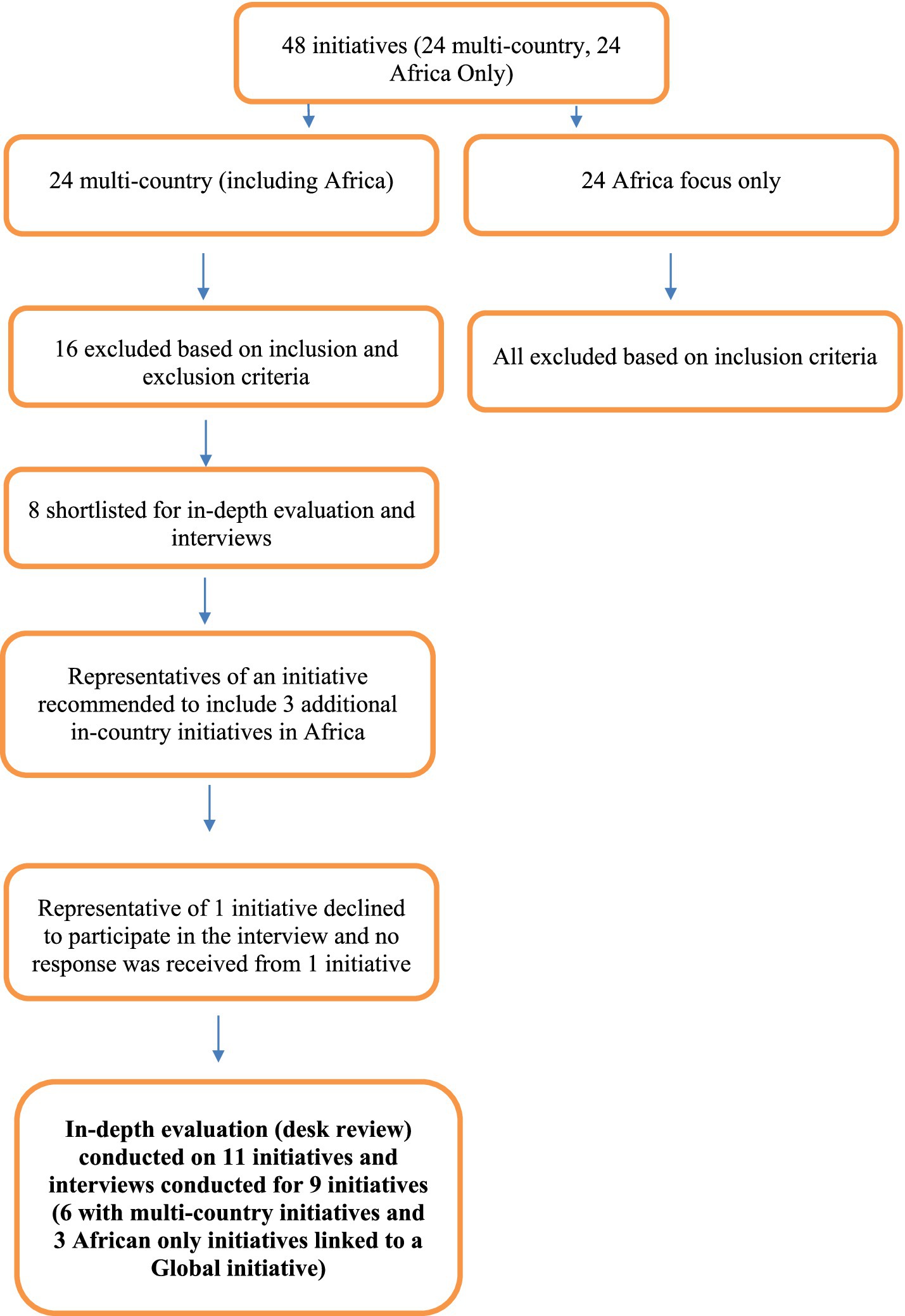

Figure 1 outlines the results of the shortlisting of nutrition-focused initiatives. Of the 48 initiatives, 24 were multi-country. The other 24 initiatives were Africa-only, which were focused on agriculture and engaged farmers, and were not included. From 24 multi-country initiatives, five (5) initiatives were shortlisted for in-depth review based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria:

• Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNI)

• Business Call to Action (BCtA)

• Zero Hunger Private Sector Pledge (ZHPSP)

• Private Sector Mechanism (PSM)

• Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Business Network (SBN), Global.

Three (3) others were added considering their potential to influence private sector actions, even though they did not qualify the inclusion criteria:

• Global Nutrition Report (GNR) and its Nutrition Accountability Framework (NAF)

• Food Systems Dashboard (FSD) and its Food Systems Countdown Initiative (FSCI)

• Business Platform for Nutrition Research (BPNR)

Additionally, three SBN country-level initiatives (Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania) were included, given their relevance to this study and suggestions by SBN Global. This was crucial to obtaining a better understanding of the activities of these initiatives at the country level. Therefore, a total of 11 nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector in Africa were shortlisted.

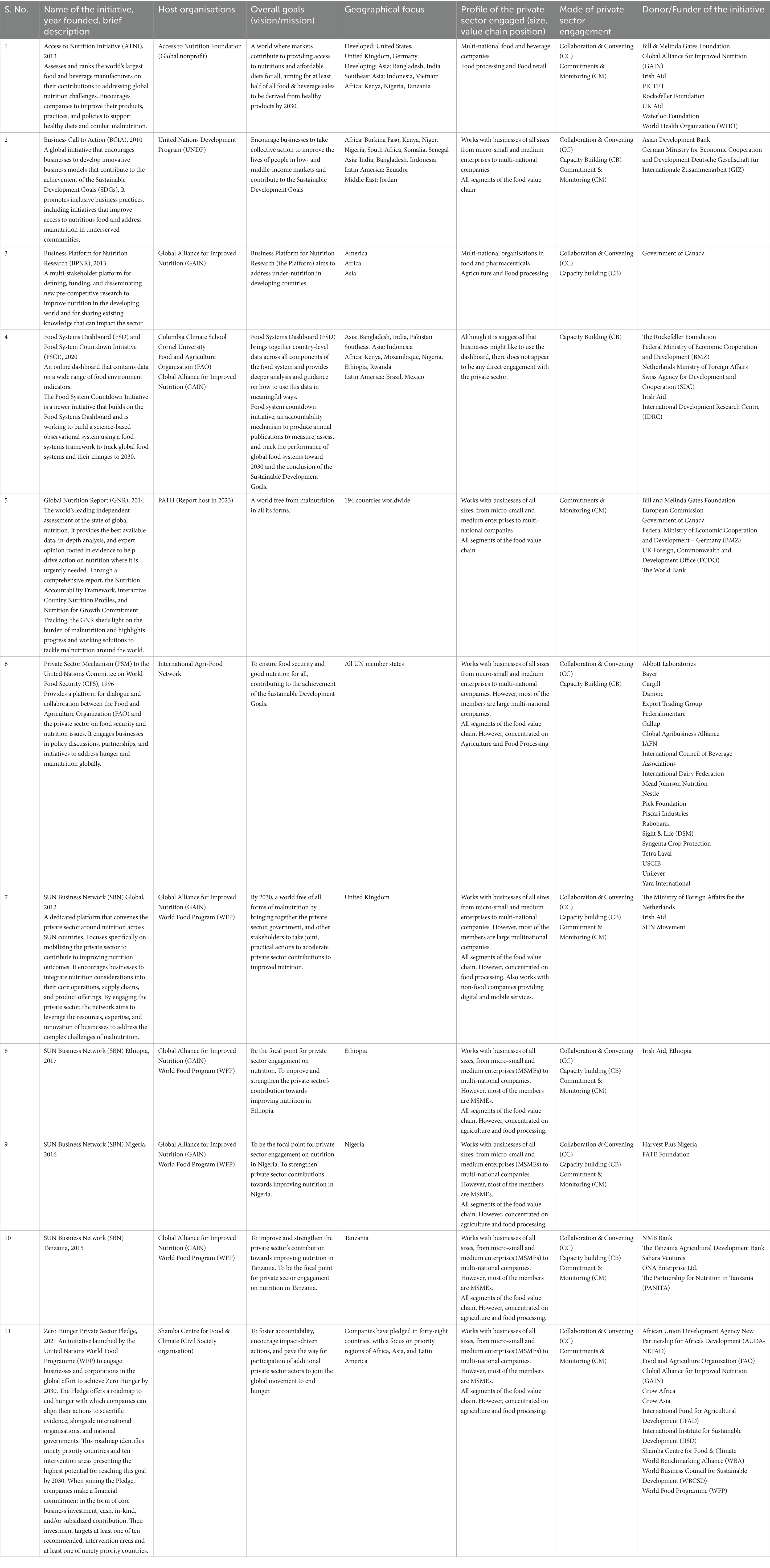

An overview of these 11 initiatives is provided in Table 1 and described below.

Table 1. Overview of civil society and development agencies-led nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector in Africa.

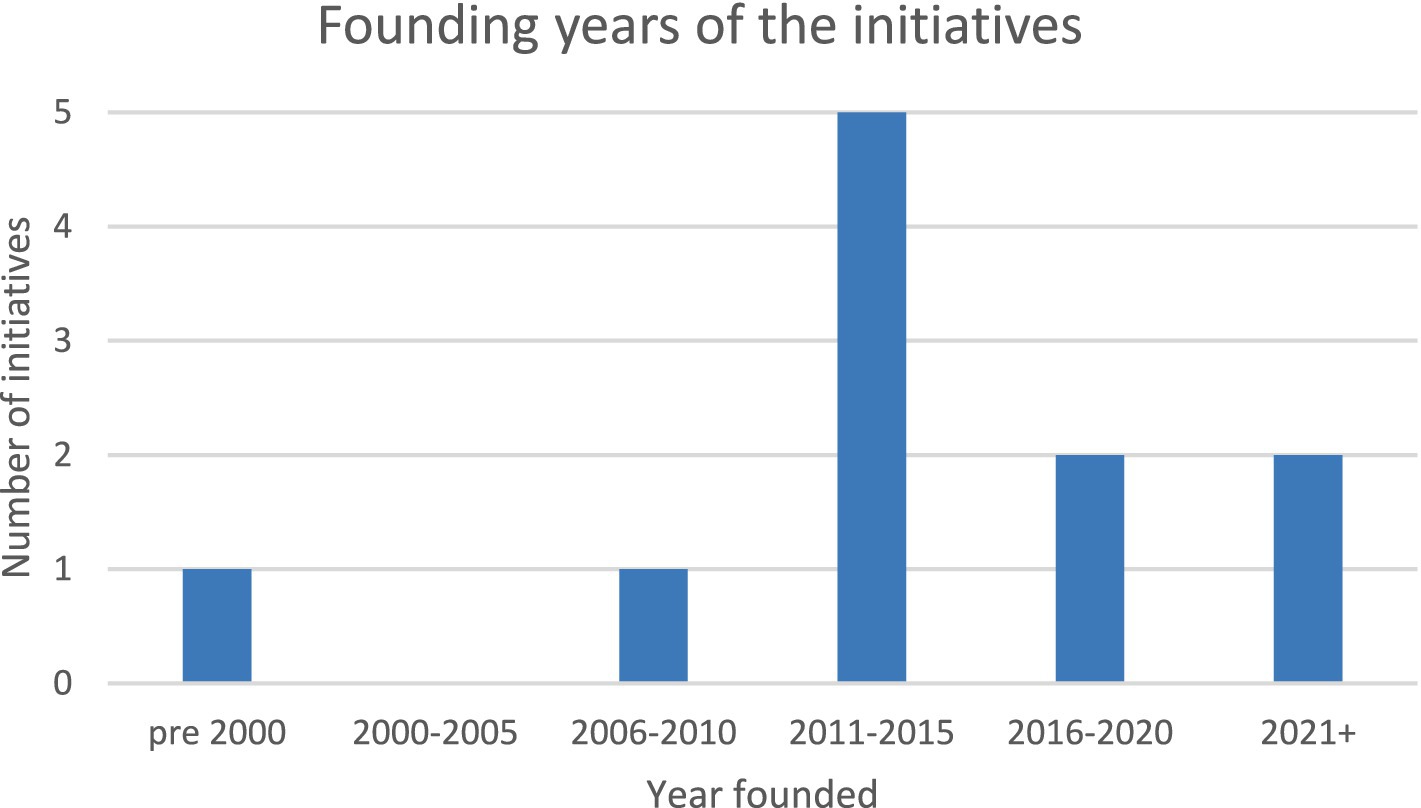

Most of these initiatives (SBN Global and Tanzania, ATNI, BPNR, and GNR) were founded between 2011 and 2015. Country networks for SBN (Nigeria and Ethiopia) were established between 2016 and 2020. FSD and ZHPSP are the most recent initiatives (Figure 2). All initiatives were engaging diverse and multiple private sector actors, ranging from large multi-national organisations to micro, small, and medium enterprises. However, initiatives such as SUN Business Networks in Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Tanzania were primarily engaging micro-small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to enhance their contributions to nutrition. Despite the efforts to engage the private sector actors throughout the food value chain, most of the actors engaged were focused on food manufacturing and processing.

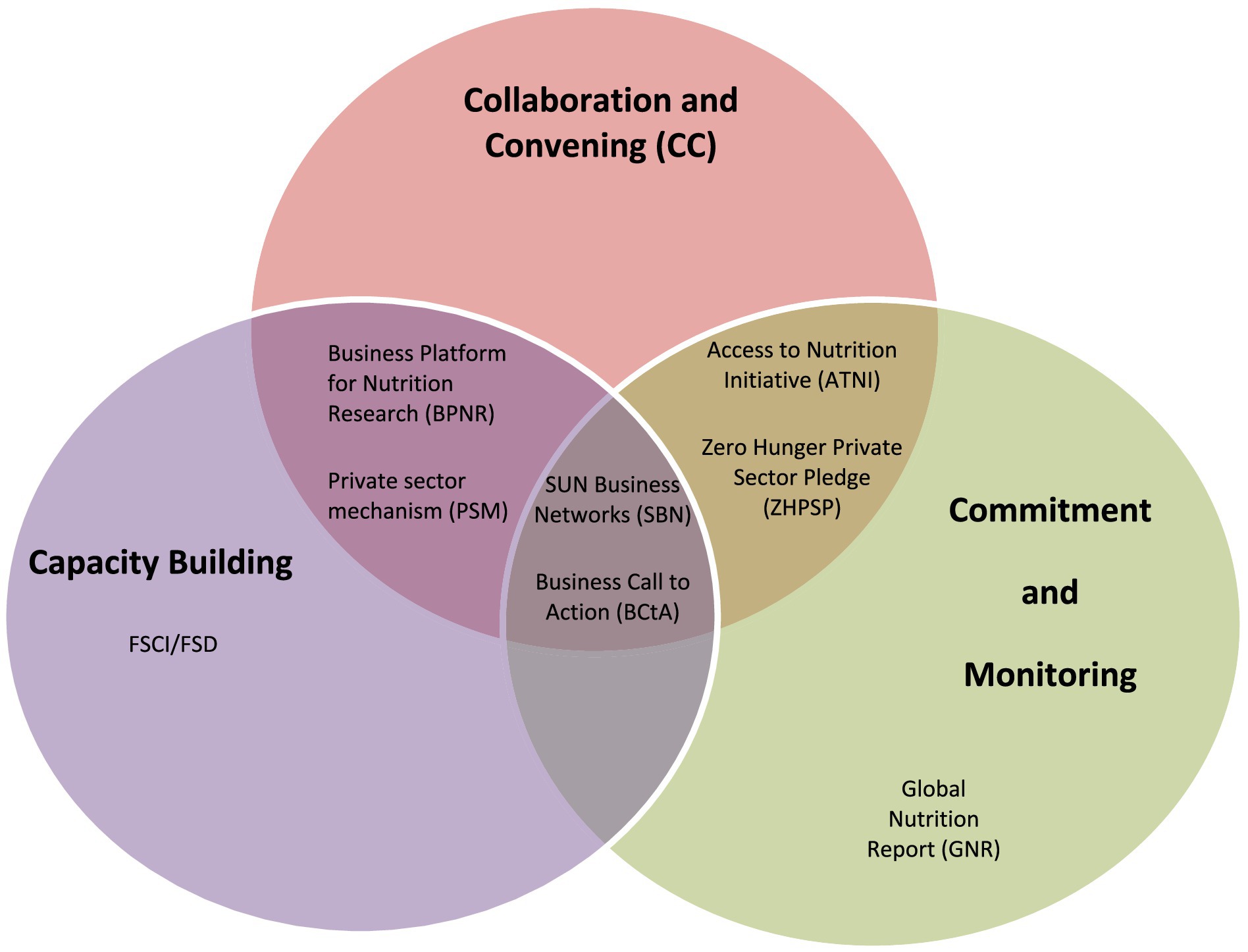

The civil society and/or development agencies were engaging the private sector using either one or a combination of the following approaches (Figure 3):

• Convening and Collaboration (CC): having discussions and dialogues to promote the need for private sector actions to improve nutrition. Examples include hosting meetings to discuss country-specific nutrition challenges, raising awareness on nutrition among private sector actors, developing networks involving private sector actors, etc.

• Capacity Building (CB): providing technical support to the private sector to develop and strengthen their skills and abilities so that they can contribute more to improving nutrition. For example, training on food safety would make available safe, nutritious foods.

• Commitment and Monitoring (CM): encouraging the private sector actors to make public commitments on nutrition and checking progress against those commitments to promote transparency.

Figure 3. Classification of nutrition-focused initiatives by approach to influence the private sector.

SBN Global and national networks (Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Tanzania) and BCtA used all three approaches to engage the private sector. Other initiatives used a combination of two approaches (BPNR, PSM, ATNI, ZHPSP). GNR and FSD interacted with the private sector using a single approach.

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) played a key role across many of the nutrition-focused initiatives. It is the lead organisation for the six initiatives (FSD/FSCD, SBN Global, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, BPNR), a donor for one initiative (ZHPSP), and has some supporting roles in two other initiatives (GNR and ATNI).

3.2 Reported successes, challenges, and recommendations by the initiatives

3.2.1 Reported successes and contributing activities

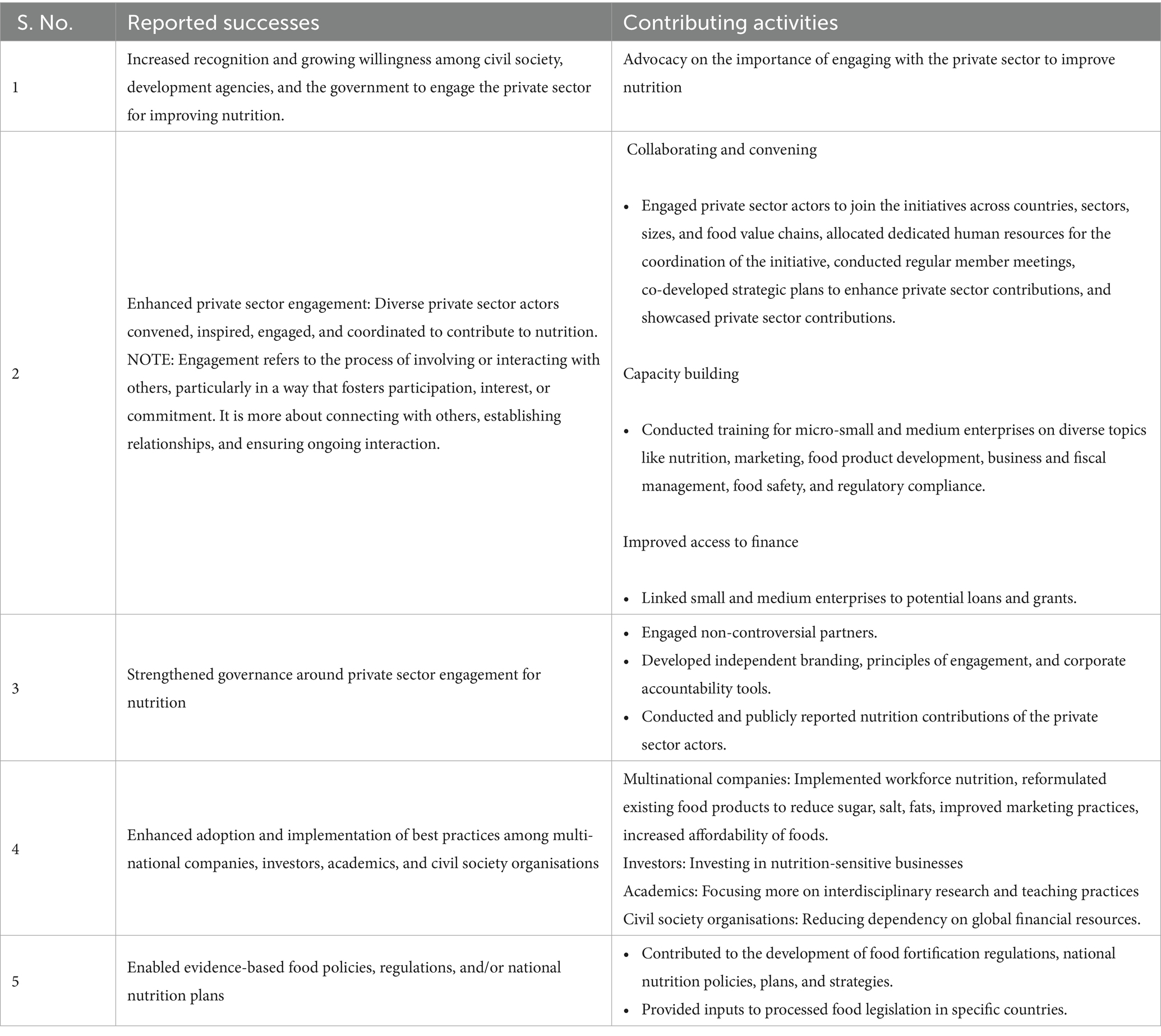

The successes reported by the representatives of the initiatives interviewed and their activities are summarised in Table 2 and described below. These have been arranged in descending order based on how frequently they were reported by interviewees, with the most cited success appearing at the top.

• Growing recognition and increased willingness among governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to engage with the private sector actors to address malnutrition: Representatives of all the initiatives interviewed acknowledged the key role and the need to engage with the diverse private sector actors to improve nutrition in Africa. They believed that their advocacy activities were instrumental in enhancing the willingness among governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to engage with the private sector for improving nutrition. This success was supported by the fact that SBNs are oversubscribed in terms of demand for setting up business networks from various national governments in Africa and other countries.

• Increased engagement of diverse private sector actors with non-governmental and development agencies to improve nutrition: The majority of interviewers mentioned that they had increased their engagement with the private sector actors of all sizes, operating in different food value chains, from food processing to retail, to improve nutrition in Africa. They attributed this success to activities such as (i) convening and coordinating diverse private sector actors, (ii) providing capacity development support to these actors, and (iii) facilitating access to finance in the form of loans and grants to the relevant actors. The presence of dedicated staff and regular meetings was highlighted as a key requirement to ensure that all types of private sector actors were effectively integrated into the initiatives’ frameworks. For micro-small and medium enterprises, provision of technical assistance (in areas like nutrition, food fortification, marketing and product development, business and financial management, regulatory compliance, and food safety), and helping them access finance through various finance opportunities like loans and grants was noted to be beneficial to sustain their engagement.

• Strengthened governance for private sector engagement in nutrition: The initiatives highlighted that their approaches and strategies to engage the private sector actors improved the quality and monitoring of private sector engagement for nutrition. Some of these approaches included engaging non-controversial partners and developing independent branding to ensure that the initiatives were perceived as neutral and objective. It was noted that pre-defined principles of engagement provided a clear framework to guide private sector participation for improving nutrition. Monitoring tools like the nutrition accountability framework and public reporting of private sector contributions to nutrition were also recognised as useful mechanisms to improve accountability of the private sector actors towards nutrition.

• Increased adoption and implementation of best practices among diverse stakeholders: It was reported that various multi-national companies are reformulating their foods to reduce sugar, salt, and fat, using responsible business practices, and are investing in the health of their employees. Investors, through the advocacy efforts of an initiative, were noted to be mobilising their investments towards nutrition-sensitive businesses. The approach of interdisciplinary research and teaching practices was also reported by one of the initiatives.

• Development of evidence-based food policies, regulations, and national nutrition plans: An initiative reported that they worked closely with the government to support the development of their country’s food fortification regulations by sharing inputs from their relevant private sector members. Another initiative highlighted that their accountability monitoring reports were instrumental in guiding some governments to develop regulations on foods high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats. Comprehensive food systems data provided by another initiative was noted to be contributing to the development of evidence-based nutrition policies.

Table 2. Successes and contributing activities reported by the representatives of the initiatives interviewed.

In summary, these successes were noted to be instrumental in strengthening engagement among diverse stakeholders (private sector, government, civil society, academia, development agencies, and donors) across sectors and geographies and to ensure a cohesive and comprehensive approach to address the burden of malnutrition.

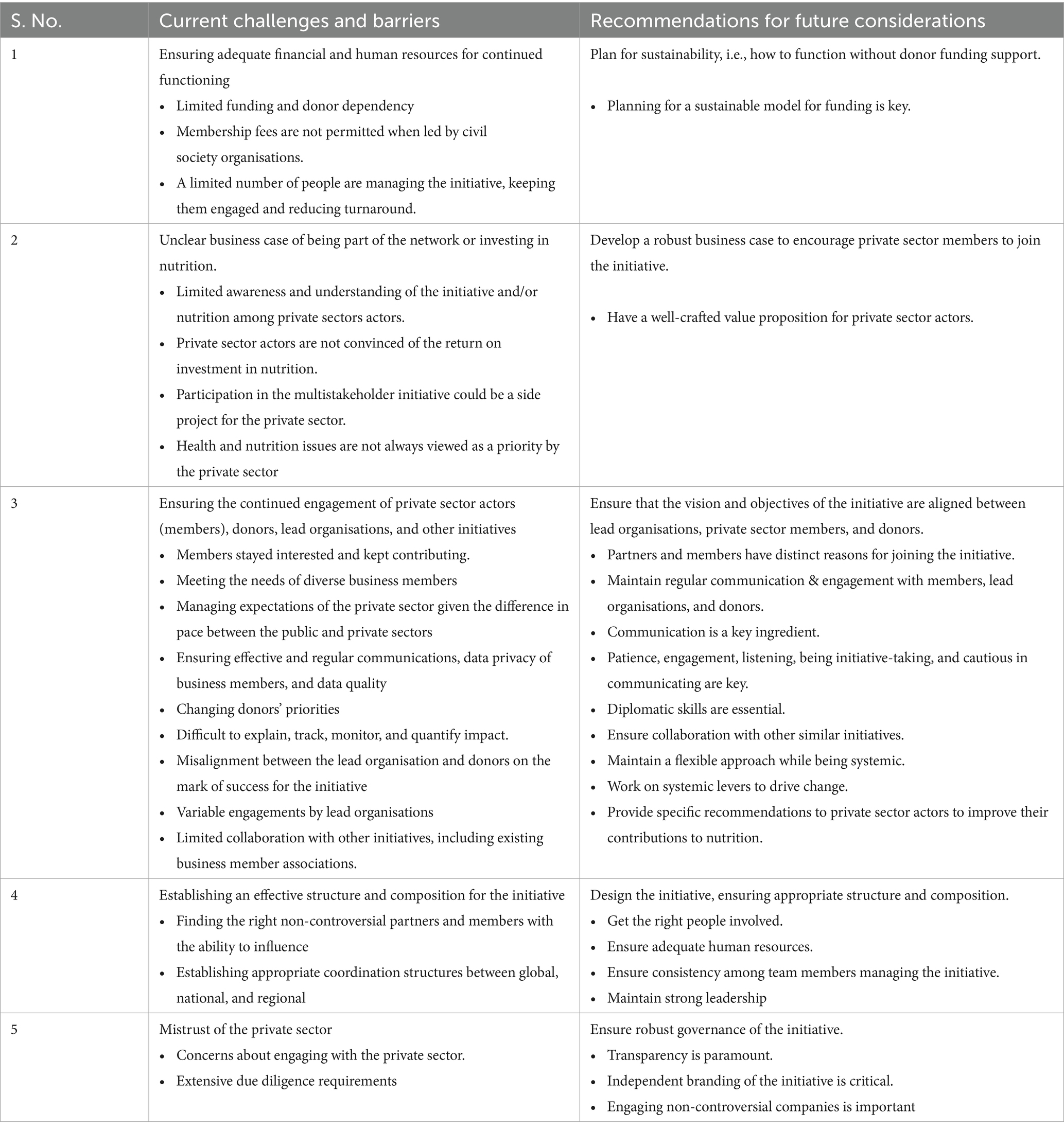

3.2.2 Challenges encountered and recommendations for future planning

Interviews with representatives from nine initiatives and a review of their publicly available evidence highlighted five challenges that hindered their development and functioning. These are summarised in Table 3 and have been organised in decreasing order, with the most frequently mentioned challenge at the top. Eight recommendations were provided by the interviewees. As the recommendations stem from the initiatives’ challenges, they are presented alongside the corresponding challenges to avoid repetition.

• Ensuring adequate financial and human resources for the development and function of the initiative: Most of the initiatives frequently faced pressing issues of limited funding, as they often rely on external sources of financial support, such as donors. The scope and scale of their activities are often restricted by the availability of funds, limiting the services they can provide to their members, the regions they can reach, and the overall effectiveness of their plans and strategy. Further complicating the financial sustainability was that all these initiatives are being led by civil society or development agencies and are prohibited from charging membership fees from the participating private sector members. This restriction limited their ability to generate revenue from within their networks, which could otherwise provide a more stable and self-sustaining funding model. The initiatives often encountered operational challenges, such as limited staff, and ensuring that they continue to remain motivated and engaged. The available human resources were mostly insufficient to drive these initiatives across diverse regions, to balance coordination requirements, to scale activities, maintain momentum and engagement, and achieve meaningful impact. Maintaining the motivation and commitment of the staff and managing turnover, particularly when there are constant funding pressures, caused disruptions in progress and resulted in the loss of valuable institutional knowledge.

Considering these challenges, it was recommended that financial and human resources be planned for from the outset of the initiative.

• Unclear business rationale for investing in nutrition: It was highlighted that private sector members from micro-small and medium enterprises to large multinational companies had limited knowledge of nutrition. This was further exacerbated by the complexity of nutrition, which made it difficult for them to fully understand and engage with nutrition-related initiatives. Private sector actors struggled to understand the benefits to their businesses because of investing in nutrition and were unclear on how to incorporate nutrition initiatives into their core operations. These gaps in understanding nutrition and its return to business contributed to difficulty or resistance in the private sector actors to engage with civil society and development agencies for improving nutrition.

Therefore, it was recommended to develop a strong business case and present a well-crafted, tailored value proposition to different private sector stakeholders for enhanced engagement.

• Ensuring the continued engagement of initiative private sector members, donors and partners, and other stakeholders: All initiatives rely on ongoing participation from businesses, civil society, governments, and donors. Sustaining the continued engagement of these stakeholders required continuously demonstrating value. The challenge of meeting the needs of stakeholders from different sectors is further complicated due to the diversity of private sector actors concerning size, food value chains, etc. The difference in pace of advancement between public and private sector actors and ensuring privacy of confidential business data were also noted as challenges.

Shifting priorities of donors were also recognised, which made it difficult for the initiative to plan and execute long-term strategies. It was also highlighted that there were instances where there were misalignments in the mark of success between the lead organisations and donors, combined with difficulties in measuring and reporting tangible results of the initiatives engaging the private sector members. Initiatives focused on commitments and monitoring highlighted the challenge of demonstrating additionality in private sector contributions.

Initiatives also noted that civil society and development agencies shifted between active and passive participation based on their internal agendas and priorities. Lastly, the absence of nutrition-focused business member organisations and their limited willingness to collaborate with initiatives led by the civil society or development agencies made it difficult for the initiatives to transition from dependency on donor funding.

In response to these challenges, four key recommendations emerged: (i) establish a shared vision early in the process that all stakeholders can align with, allowing their diverse objectives to coexist within a broader goal of improving nutrition outcomes; (ii) maintain regular engagement through meetings, reports, or digital platforms to keep stakeholders actively involved and committed to the initiative’s success; (iii) explore and pursue collaboration opportunities with similar initiatives to enhance sustainability and broaden impact; and (iv) focus on systemic levers to drive long-term change, while staying adaptable to evolving conditions, emerging opportunities, and unexpected challenges.

• Establishing a robust structure and composition of the initiative: Striking a balance between influence and neutrality when selecting the private sector members was found challenging, especially in an environment where private sector involvement is viewed with scepticism. Developing robust coordination structures to ensure alignment of objectives, roles, and responsibilities at the national, regional, and international level was noted as a challenge by country-specific initiatives working under international guidance.

Accordingly, strong leadership was recommended to guide the development and implementation of the initiatives. Retaining core team members and engaging the right private sector actors were identified as crucial for advancing nutrition outcomes.

• Mistrust of the private sector: Widespread mistrust of the private sector, particularly within the nutrition and development sectors, is an ongoing challenge. This is often due to historical concerns over profit-driven motives and the role of the private sector in perpetuating issues such as unhealthy diets or unsustainable practices. The initiatives highlighted that this scepticism often contributed to reluctance among governments and civil society, and development agencies to fully engage with the private sector, despite the potential benefits of the engagement. To manage these concerns, the initiatives needed extensive due diligence processes involving, but not limited to, thorough evaluations of companies’ track records, practices, and alignment with the initiative’s goals. While necessary, these due diligence requirements were noted to be time-consuming and resource-intensive, further complicating the process of engaging the private sector. The combination of mistrust, concerns over engagement, and the burden of due diligence created a significant challenge for such initiatives, particularly in sectors like nutrition, where the role of the private sector is often viewed with scepticism.

To address the aforementioned challenges, several strategies were recommended: establishing independent branding to safeguard the initiative’s integrity; engaging non-controversial private sector partners while excluding those with a history of ethical concerns or harmful practices; and ensuring full transparency regarding the roles and contributions of private sector partners, funding sources, and the criteria used for decision-making within the initiative.

4 Discussion

4.1 Profile of the initiatives

This paper has attempted to identify and describe civil society and development agency-led initiatives that engage with the private sector to improve nutrition in Africa. The goal of these initiatives is to influence practices or monitor how serious the private sector actors are about improving nutrition, and in some cases, help them when resources are constrained to make the necessary changes.

We found only a few initiatives led by civil society and development agencies engaging diverse private sector actors for nutrition. These initiatives focus on influencing the private sector to manufacture and sell nutritious foods with an emphasis on dietary adequacy, and on reducing the intake of nutrients of public health concern. Our findings are unlike those of Heren et al., who reported that multi-stakeholder platforms focused on nutrient adequacy rather than moderation (Herens et al., 2022). The shortlisted nutrition-focused initiatives in Africa were multi-country and were developed by civil society and development agencies located in the Global North. These emerged possibly because of the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement in 2010. Most of these initiatives were engaging with the large private sector actors, manufacturing, and processing food. These findings are like the study by Slater et al., which identified 45 food systems multi-stakeholder initiatives. These initiatives were dominated by multi-national corporations engaged in food processing and were based in high-income countries of the Global North (Slater et al., 2024). Our findings also agree with another study that examined multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) to drive healthier and more sustainable food systems. It identified and categorized actors within these MSIs, drawing on social network analysis to provide insights into actor centrality, power structures, and how this might impact MSIs’ potential to drive transformative change. Thirty MSIs were included and had 813 actors. Most actors were based in high-income countries (HICs) (n = 548, 67%) (Van Den Akker et al., 2024).

We found that diverse private sector actors were engaged by some of these initiatives, including multi-national companies and micro, small, and medium enterprises. The engaged private sector actors were working on diverse foods throughout the food value chain, from food processing to retail. Even though engagement with private sector actors in food retail was noted in some initiatives like ATNI, this engagement is still at a nascent stage. Limited engagement with the private sector actors involved in food storage, transport, trade, transformation, retail, and provisioning was also noted by Herens et al. (2022) and another study (Harvey and Trewern, 2018).

Our study found that many civil society and development agencies are engaging the private sector to improve nutrition. However, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) was identified as one of the organisations with footprints across most of the nutrition-focused initiatives engaging the private sector. It was either the lead organisation or a donor, or an advisor in these initiatives. These findings are similar to those reported by Van Den Akker et al., who, in addition to identifying the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) as organisations with connections with maximum multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs), also listed GAIN as an actor with connections to MSIs (Van Den Akker et al., 2024). International civil society and development agencies such as FAO, UNDP, WFP, Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN), the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), were also identified as lead organisations for 89 multi-stakeholder platforms in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Nigeria (Herens et al., 2022).

Our study found that the nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector were funded from multiple sources and that the majority was from grants to implement projects over a specified period. This funding model poses a challenge to the long-term sustainability of such initiatives. Indeed, a 2021 study reported that nearly all multi-stakeholder platforms were initiated and/or facilitated with donor support (Van Ewijk and Ros-Tonen, 2021).

We also found that all Africa-only initiatives focused on agriculture and are engaging farmers to help them improve their food production and/or access markets to sell their produce. While a nutrition-sensitive approach has started to emerge in some of these initiatives, nutrition is not their primary focus. Our findings are in line with those reported by a systematic literature review on food-related multistakeholder platforms (MSPs) in sub-Saharan Africa (Van Ewijk and Ros-Tonen, 2021). The MSPs included were focused on crops and integrated management systems, and environment management for agricultural development. Additionally, the reported outcomes of the review included changes in agricultural practices and increased market access for the farmers. Another study in Nigeria reported that several non-governmental organisations or civil society-driven MSPs are addressing the development of the agricultural sector for improved food security from a market-led perspective (Herens et al., 2022).

The initiatives involving multinational companies engaged these actors either by facilitating private sector commitments to improve nutrition and monitoring the same (e.g., ATNI, GNR, and ZHPSP) or by convening and collaborating with these actors. Initiatives engaging micro-small and medium enterprises (SBN country networks), in addition to these two approaches, incorporated a capacity-building aspect to ensure the continued engagement of their private sector members. These findings are similar to findings of a study exploring multi-stakeholder platforms in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, which reported that various civil society and development agencies engaged the private sector actors through coordination, capacity building, and knowledge sharing activities (Herens et al., 2022).

We also noted a few connections between nutrition initiatives. Only initiatives that had both multi-country and international presence, such as Scaling Up Nutrition Business Networks (Global and Country), were learning from each other, facilitated by their international office. Our findings are similar to those reported by Heren et al., which noted that different multi-stakeholder platforms act within their own local or regional environment rather than reaching out to other multi-stakeholder platforms (Herens et al., 2022).

4.2 Successes and challenges of the initiatives

The successes of nutrition focused initiatives reported by our study were—a growing recognition and increased willingness among governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to engage with the private sector actors to address malnutrition, increased engagement of diverse private sector actors with non-governmental and development agencies to improve nutrition, strengthened governance for private sector engagement in nutrition, increased adoption and implementation of best practices among diverse stakeholders and development of some evidence-based food policies, regulations, and national nutrition plans. Although these noted successes are of the initiatives most of which have developed in the last decade, these primarily reflect activities and outputs identified through interviewee responses responses, supplemented by a few independent evaluations available in the public domain. Our findings are like a study evaluating whether multi-stakeholder platforms (MSPs) are effective approaches to agri-food sustainability. This study reported that the effectiveness of MSPs is primarily framed as successfully delivering activities and outputs, such as platform members. It is not assessed in terms of the role of the initiative in influencing a specific food sector. The study recommends that more MSPs should undertake better assessments of their contribution to food system transformation and report publicly on these results to generate a clear understanding of whether and how MSPs are capable of catalysing more sustainable food systems (Thorpe et al., 2022). Some additional evidence also notes that MSPs may play a role in transforming food systems (Herens et al., 2022). Some other independent evidence on multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) on food systems transformation questions the legitimacy and influence of such initiatives (Slater et al., 2024). Another study highlights that MSIs engaging the private sector may reflect rather than challenge existing power structures, thus serving to maintain the status quo. It recommends a need to critically examine their ability to drive global food system transformation (Van Den Akker et al., 2024). Herens et al. also concluded that existing multi-stakeholder platforms may have limited capacity to truly transform the food systems (Herens et al., 2022).

Challenges noted for the development and function of nutrition focused initiatives in our study were ensuring adequate financial and human resources, unclear business rationale for investing in nutrition, ensuring the continued engagement of initiative private sector members, donors and partners, and other stakeholders, establishing a robust structure and composition of the initiative and managing the mistrust of the private sector including conflict of interest. These findings are aligned with the study by Heren et al., which reported that funding of the multi-stakeholder platforms was often project or programme-based, with a set timeframe, based on core funding from key international donors. Upon completion of the assignment or closure of the project, many multi-stakeholder platforms tended to turn inactive or fall apart. The study also noted other barriers and challenges hindering MSPs from being more adaptive in food systems governance, such as limited human and financial resources, conflicts of interest, coordination problems, lack of continuity, multiple national policies, and unclear structure and rules. The study also highlighted that the sustainability of such platforms is a critical challenge (Herens et al., 2022). Another study also highlighted the challenge of managing conflicts of interest in initiatives involving the multi-national food industry manufacturing ultra-processed foods (Slater et al., 2024).

4.3 Limitations of this study

This study has a few limitations. There is no database of nutrition initiatives led by civil society organisations or development agencies engaging with the private sector, and our attempt to create one might have missed some. The search was only done using the English language, and there may be initiatives with data in other languages. Even though the study focused on nutrition initiatives in Africa, an in-depth evaluation was done on multi-country nutrition-specific initiatives that were initiated in the Global North and were operating in Africa. Exclusion of Africa-only nutrition-sensitive initiatives based on the stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria could have introduced some selection bias. In addition, we reported short-term success and challenges of the shortlisted initiatives (within the last 10 years). Since the success of such initiatives takes longer, the actual success and outcomes are yet to be seen. Also lack of consensus and framing of what success entails within the complex initiatives is a limitation of this study. Lastly, the reported successes and challenges represent the perspective of civil society and development agencies. This study does not include the perspective of private sector members engaged in such initiatives. Despite these limitations, this is one of the first studies to identify and describe civil society and development agencies-led nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector in Africa and report their success and challenges. These findings can provide useful guidance for future nutrition initiatives engaging the private sector.

4.4 Future research

To address the limitations of the current study, future research could focus on in-depth evaluations of nutrition-sensitive Africa-only initiatives engaging farmers. Research efforts are also needed for the development of metrics that can help quantify the success of such initiatives. Additionally, there is a need to systematically assess the ability of these initiatives to influence private sector actions to improve nutrition.

5 Conclusion

This research adds to the growing body of evidence on nutrition initiatives in Africa that are led by civil society organisations and development agencies engaging the private sector. While several initiatives were initially identified, only a limited number met the nutrition-focused criteria. These initiatives involved a range of private sector actors, primarily in food manufacturing and processing. However, the limited engagement of food retailers suggests a missed opportunity, especially given the vital role of retail in shaping diets and nutrition outcomes. Greater efforts are needed to include these actors in future initiatives. All the nutrition initiatives examined were multi-country efforts initiated by organisations based in the Global North. Considering malnutrition’s diverse and context-specific nature across African countries, African leadership must increase its focus on nutrition initiatives to ensure local relevance and ownership. As most of these initiatives have been active for less than a decade, it remains too early to draw definitive conclusions about their effectiveness in influencing private sector actions. Continued investment, both financial and human, is essential to sustain progress and enable independent evaluations of their impact on private sector practices. Finally, fostering collaboration between initiatives is critical. Many of the challenges identified are shared across initiatives, and coordinated efforts can help maximize the overall impact of nutrition-focused initiatives engaging the private sector in the region.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Tufts University and Tufts Medical Centre. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation. FW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KM: Investigation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is funded through Tufts University grant for the Food Prices for Nutrition (FPN) project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and UKAid from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) as INV-016158.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the key informants who participated in the interviews, and especially Professor William Masters and Mr. Alex Kneuppel of Tufts University for engaging us on this project and for their inputs and support throughout this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1541076/full#supplementary-material

References

Aseete, P., Barkley, A., Katungi, E., Ugen, M., and Birachi, E. (2023). Public–private partnership generates economic benefits to smallholder bean growers in Uganda. Food Secur. 15, 201–218. doi: 10.1007/s12571-022-01309-5

Clapp, J. (2017). Concentration and power in the food system: who controls what we eat? Glob. Environ. Polit. 17, 151–152. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_r_00423

Dentoni, D., and Peterson, C. H. (2011). Multi-stakeholder sustainability alliances in Agri-food chains: a framework for multi-disciplinary research. Int. Food Agribus, Manag. Rev. 14, 83–108.

Development Initiatives. (2022). 2021 global nutrition report: the state of global nutrition. Available online at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/ [Accessed June 15, 2025].

Dukeshire, S. (2013). Concentration, consolidation, and control: how big business dominates the food system. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 4, 1–173. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2013.041.010

Fanzo, J, Shawar, YR, Shyam, T, and Shiffman, J. (2020). Food system PPPs: can they advance public health and business goals at the same time? Available online at: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/gain-discussion-paper-series-6-food-systemsy-ppps-can-they-advance-public-health-and-business-goals-at-the-same-time.pdf [Accessed October 15, 2024].

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2024). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024 - financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome. Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/ebe19244-9611-443c-a2a6-25cec697b361 (accessed 22 June 2025).

Food Forward NDCs. (2024). Strengthening inclusive multistakeholder approaches in food governance. Available online at: https://foodforwardndcs.panda.org/content/uploads/2024/08/Strengthening-inclusive-multi-stakeholder-approaches-in-food-governance-Food-Forward-NDCs.pdf [Accessed June 3, 2025].

Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. (2025). Food prices for nutrition – diet cost metrics for a better-fed world. Available online at: https://sites.tufts.edu/foodpricesfornutrition/ [Accessed June 16, 2025].

Gaihre, S., Kyle, J., Semple, S., Smith, J., Marais, D., Subedi, M., et al. (2019). Bridging barriers to advance multisector approaches to improve food security, nutrition and population health in Nepal: transdisciplinary perspectives. BMC Public Health 19:961. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7204-4

Harvey, M, and Trewern, J. (2018). Sustainable food systems and diets: a review of multi-stakeholder initiatives. Available online at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/59078%20Sustainable%20food%20systems%20report%20-%20ONLINE.pdf [Accessed June 3, 2025].

Herens, M. C., Pittore, K. H., and Oosterveer, P. J. M. (2022). Transforming food systems: multi-stakeholder platforms driven by consumer concerns and public demands. Glob. Food Sec. 32:100592. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100592

HLPE on Food Security and Nutrition (2018). Multi-stakeholder partnerships to finance and improve food security and nutrition in the framework of the 2030 agenda.

Initiative, T. P. (2016). An introduction to multi-stakeholder partnerships, briefing document for the GPEDC high level meeting. Available online at: https://archive.thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Introduction-to-MSPs-Briefing-paper.pdf [Accessed June 3, 2025].

Kar, B. K. (2014). Multi-stakeholder Partnership in Nutrition: an experience from Bangladesh. Int. J. Commun. Health 26, 15–21.

Levine, R., and Kuczynski, D. (2009). Global nutrition institutions: is there an appetite for change? Available online at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/esswpaper/id_3a2256.htm [Accessed November 27, 2024].

Lie, AL, and Granheim, SI (2017). Multistakeholder partnerships in global nutrition governance: protecting the public interest. 137, 1806.

Lile, R., Ocnean, M., and Balan, I. M. (2023). “Challenges for zero hunger (SDG 2): links with other SDGs” in Transitioning to zero hunger. ed. D. I. Kiba (Switzerland: MDPI).

Nduhura, A, Molokwane, T, Lukamba, M, Mugerwa, B, Nuwagaba, I, Twinomuhwezi, I, et al. (2022). Food Security: The Application of Public Private Partnerships to Feed the Hungry and Prosper Africa. 1, 65–94.

Rural21. (2019). Multi-stakeholders for better food systems. The International Journal of Rural Development, 53.

Scaling Up Nutrition. (2025). Scaling Up Nutrition. Available online at: https://scalingupnutrition.org/about/who-we-are (accessed 22 June 2025).

Slater, S., Lawrence, M., Wood, B., Serodio, P., Van Den Akker, A., and Baker, P. (2024). The rise of multi-stakeholderism, the power of ultra-processed food corporations, and the implications for global food governance: a network analysis. Agric. Hum. Values. 42, 177–192. doi: 10.1007/s10460-024-10593-0

Smyth, S. J., Webb, S. R., and Phillips, P. W. B. (2021). The role of public-private partnerships in improving global food security. Glob. Food Sec. 31:100588. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100588

SUN. (2023). Coordination at the heart of the SUN movement in Mali_ the role of multi-stakeholder and multisectoral platforms. Available online at: https://scalingupnutrition.org/resource-library/case-studies/coordination-heart-sun-movement-mali-role-multi-stakeholder-and [Accessed June 3, 2025].

Thorpe, J., Sprenger, T., Guijt, J., and Stibbe, D. (2022). Are multi-stakeholder platforms effective approaches to Agri-food sustainability? Towards better assessment. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 20, 168–183. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2021.1921485

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

UNDP. (2023). Working with power in multi-stakeholder processes. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/foodsystems/publications/working-power-multi-stakeholder-processes [Accessed June 3, 2025].

UNEP, FAO and UNDP. (2023). Rethinking food systems: A guide for multi-stakeholder collaboration. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/publications/rethinking-our-food-systems-guide-multi-stakeholder-collaboration (accessed 22 June 2025).

UNGA. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf [Accessed June 15, 2025].

Unicef. (2023). Key asks 2023 voluntary national reviews: SDG 2, zero hunger issue brief. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/documents/sdg-issue-brief-2 [Accessed June 15, 2025].

University of Reading. (2025). Summon discovery service. Available online at: https://www.reading.ac.uk/library/using-the-library/catalogues/summon [Accessed June 15, 2025].

USAID. (2016). Operationalizing multi-sectoral coordination and collaboration for improved nutrition recommendations from an in-depth assessment of three countries’ experiences.

Van Den Akker, A., Fabbri, A., Slater, S., Gilmore, A. B., Knai, C., and Rutter, H. (2024). Mapping actor networks in global multi-stakeholder initiatives for food system transformation. Food Secur. 16, 1223–1234. doi: 10.1007/s12571-024-01476-7

Van Ewijk, E., and Ros-Tonen, M. A. F. (2021). The fruits of knowledge co-creation in agriculture and food-related multi-stakeholder platforms in sub-Saharan Africa – a systematic literature review. Agric. Syst. 186:102949. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102949

World Health Organization. (2024). Malnutrition key facts. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition [Accessed March 18, 2025].

Keywords: multi-sectoral, nutrition, Africa, civil society, private sector, food systems

Citation: Mittal N, Wallace F and Mukumbi K (2025) From advocacy to action: civil society and development agencies engaging the private sector actors to improve nutrition in Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1541076. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1541076

Edited by:

Julian Douglas May, University of the Western Cape, South AfricaReviewed by:

Sabrina Arcuri, University of Pisa, ItalyJacob Korir, Texas Tech University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Mittal, Wallace and Mukumbi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Navneet Mittal, bmF2bmVldG1pdHRhbEBnbWFpbC5jb20=; bi5taXR0YWxAcmVhZGluZy5hYy51aw==

Navneet Mittal

Navneet Mittal Fiona Wallace

Fiona Wallace Kudzai Mukumbi

Kudzai Mukumbi