- 1Business School, Guangdong Ocean University, Yangjiang, China

- 2College of Economics and Management, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

Introduction: In dynamic and unpredictable environments, farmers’ cooperatives must develop organizational resilience to maintain a sustainable competitive advantage. However, the mechanisms through which resilience impacts competitiveness remain underexplored in existing literature. This study investigates how chairpersons’ self-efficacy, as a key psychological factor, fosters both planned and adaptive resilience, ultimately enhancing the cooperative’s competitive advantage.

Methods: Grounded in social cognitive theory, we conducted a survey of 286 farmers’ cooperatives in Guangdong Province, China. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the relationships between self-efficacy, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage. Additionally, multiple regression analysis was used to test the moderating effect of environmental dynamism.

Results and discussion: The empirical results show that chairpersons’ self-efficacy significantly strengthens both planned and adaptive resilience. In turn, these two forms of resilience positively influence cooperative competitive advantage, mediating the link between self-efficacy and competitiveness. Furthermore, environmental dynamism negatively moderates the resilience–competitiveness relationship, suggesting that resilience translates more effectively into advantage under relatively stable conditions. In highly dynamic contexts, cooperatives must complement resilience with additional adaptive strategies to sustain performance.

Conclusion: This study highlights the pivotal role of chairpersons’ psychological capital in shaping cooperative resilience. By enhancing leaders’ self-efficacy, cooperatives can strengthen both planned and adaptive resilience. However, resilience yields greater benefits in stable environments, while dynamic conditions demand more flexible and adaptive approaches. These insights extend resilience theory in cooperative settings and provide practical guidance for sustaining competitiveness under uncertainty.

1 Introduction

As novel agricultural management organizations (Zheng et al., 2024), farmers’ cooperatives are positioned to bridge the gap between smallholder farmers and the broader market (Liu et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024), make a substantial contribution to agricultural modernization and rural development (Jiang et al., 2024), and serve as a core force in rural revitalization efforts (Li and Ito, 2024). In the face of financial turmoil, pandemics, and climate change as highlighted by Hollands et al. (2024), farmers’ cooperatives must navigate widespread crises and mounting competitive pressures. The increasing volatility of environmental conditions demands stronger organizational resilience to maintain continuous operations and sustain competitive advantage amid unexpected challenges (De Matteis et al., 2023). Organizational resilience, recognized as a critical dynamic capability, reflects an organization’s ability to respond to and recover from disturbances through strategic resource allocation and acquisition (Hillmann and Guenther, 2021; Palanikumar et al., 2023; Florez-Jimenez et al., 2025). It captures the capacity to bounce back quickly from disruptions while maintaining operational performance (Anwar et al., 2021; Sinha and Edalatpanah, 2023). Resilient organizations anticipate threats, act decisively during crises, and adapt to change, thus ensuring business continuity and long-term competitiveness (Trieu et al., 2024; Yoshida, 2024).

Despite substantial policy support from the Chinese government, farmers’ cooperatives in China are still at an early stage of development and often lack robust resilience (Liu et al., 2024). These cooperatives tend to be small in scale (Jiang et al., 2024) and remain vulnerable to environmental shocks. Cooperative production can be disrupted by natural disasters, and the perishable nature of agricultural products intensifies both production and market risks, exceeding those faced by many other industries. External shocks frequently catch cooperatives unprepared, hindering their ability to respond and adapt quickly, which threatens their viability and long-term sustainability. Consequently, in a rapidly evolving agricultural landscape, cooperatives must develop strategic adaptive capabilities to manage external pressures effectively and preserve their competitive edge (Giagnocavo et al., 2018; Martos-Pedrero et al., 2025). In China, research on organizational resilience is nascent, with few empirical studies to date, revealing a clear theoretical gap.

Moreover, within farmers’ cooperatives, managers—especially chairpersons—play a pivotal role in shaping organizational trajectory (Liang and Li, 2024). As hybrid entities, cooperatives face the dual challenge of balancing member-driven governance with market responsiveness. Thus, leadership in agricultural cooperatives is more critical than in many other complex organizations. Empirical studies (Hu et al., 2023) suggest that cooperative leaders’ personality traits, particularly self-efficacy, strongly influence cooperative resilience. Self-efficacy, a central concept in cognitive theory (Bandura, 1982), refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to handle unforeseen challenges. This psychological resource helps managers mitigate crisis-induced stress, communicate confidence to their teams, and enhance the organization’s preventive and crisis-management capabilities (Božović et al., 2021), thereby bolstering organizational resilience (Kunz and Sonnenholzner, 2023; Santoro et al., 2020). Although chairpersons’ self-efficacy has been studied, its direct link with organizational resilience remains underexplored. This study uses survey data from Guangdong, China to examine how chairpersons’ self-efficacy strengthens organizational resilience and competitive advantage at the cooperative level—an important but under-researched area.

Finally, organizational resilience is highly contextual (Peter and Zhu, 2021; Li et al., 2021). Introducing environmental dynamism as a contextual variable helps clarify throw resilience operates and provides practical guidance for cooperatives to maintain competitive advantage. Previous work has not fully examined these interrelationships. To address these gaps, this study empirically examines the impact of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on cooperatives’ competitive advantage in China, emphasizing the mediating role of organizational resilience. Additionally, we investigate the moderating effect of environmental dynamism.

Our contributions are threefold. First, grounded in social cognitive theory, our research broadens the literature on cooperative competitive advantage by focusing on managerial antecedents. Second, by examining the mediating role of organizational resilience, we illuminate the mechanisms linking self-efficacy to competitive advantage within cooperatives. Finally, we clarify how environmental dynamism moderates the resilience–competitive advantage relationship, identifying a key contextual factor that influences the effectiveness of resilience capabilities in cooperatives.

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 Organizational resilience and competitive advantage of cooperatives

The study of organizational resilience has become central in business management, particularly for its impact on performance (Hillmann and Guenther, 2021; Linnenluecke, 2017; Liang and Li, 2024). The term “resilience” originates from the Latin resilire, meaning to rebound or recover (Stoverink et al., 2020). Initially used in ecology to describe ecosystems’ capacity to recover from disturbances, resilience in organizations has been examined via the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities perspectives. Organizational resilience refers to an organization’s ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from disruptions while maintaining or improving operations (Kahn et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2017; Martín-Rojas et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024).

Building on existing research, we distinguish two forms of organizational resilience: planned and adaptive. Planned resilience involves proactively allocating resources for risk management and business continuity to minimize disruption impact (Nakanishi et al., 2014). Adaptive resilience entails generating novel responses to unforeseen crises, enabling organizations to pivot beyond established protocols (Bürgel et al., 2023; Forliano et al., 2023). In today’s fast-changing environment, both forms are essential for navigating uncertainty.

Empirical research on cooperative resilience remains limited (Francesconi et al., 2021; Wulandhari et al., 2022). Yet, resilience is critical for cooperatives—especially in developing nations—given their vulnerability to economic, political, and climate shocks (Birchall, 2004). Cooperative resilience has been defined as the capacity to recover from disruptions, maintain operations under stress, and seize economic and social opportunities (Borda-Rodriguez et al., 2016; Wulandhari et al., 2022). Here, we adopt a capability-centric view, defining cooperative resilience as the ability to endure, adapt, and grow amid crises.

In strategic management, resilience informs decisions that ensure survival, growth, and competitive advantage in turbulent contexts (Duchek, 2020; Hillmann, 2021). Cooperatives with strong planned resilience can innovate by anticipating market shifts and formulating effective strategies, leading to higher growth and advantage (Rakopoulos, 2014; Lin and Fan, 2024). Cooperatives with robust adaptive resilience quickly adjust structures and governance, respond to customer needs, and mitigate inefficiencies (Wiwoho et al., 2020; Zhang and Qi, 2021), thereby gaining an edge. Studies confirm a strong positive link between resilience and competitive advantage (Wieland and Wallenburg, 2013; Ostadi and Soleimon, 2017). Sobaih et al. (2021) show that both planned and adaptive resilience significantly boost performance. Building on these findings, the subsequent hypothesis is proposed:

H1a: planned resilience has a positive effect on the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

H1b: Compared with planned resilience, adaptive resilience has a greater impact on the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

2.2 Self-efficacy and competitive advantage of cooperatives

Self-efficacy is not only an individual’s belief in their ability to achieve goals but also a core dimension of psychological capital, which includes hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy (Luthans et al., 2007; Avey et al., 2009). As a component of psychological capital, self-efficacy influences behavior and outcomes (Bernacki et al., 2015). Within the broader context of entrepreneurial leadership, self-efficacy underpins opportunity recognition, risk taking, and innovation (Gupta et al., 2004; Ireland et al., 2003), making it especially relevant for cooperative chairpersons who must navigate dynamic agricultural markets.

In organizational leadership, self-efficacy is a key predictor of leader effectiveness and team success (Hannah et al., 2008; Alshebami, 2023; Raza et al., 2024). It reflects a leader’s confidence in setting goals, motivating followers, and overcoming obstacles (Paglis and Green, 2002; Zhao and Huang, 2025; Houston et al., 2025). As cooperatives face market liberalization, globalization, and shifting demands, chairpersons play a vital role in guiding sustainable growth. However, research linking chairperson self-efficacy to cooperative competitive advantage is scarce.

In China, most farmer cooperatives are founded by large farmers or entrepreneurs, referred to as chairpersons (Qu et al., 2023). These chairpersons also engage in entrepreneurial activities (Serdyukov and Grima, 2025) and hold significant decision-making power (Dong and Wang, 2018; Peng et al., 2020). Chairpersons with high self-efficacy—bolstered by other psychological capital resources such as optimism and resilience—can unite members around goals, foster dedication, and navigate challenges, thereby enhancing their confidence and decision-making (Paglis and Green, 2002). This leadership style crucially strengthens competitive positioning.

In agricultural cooperatives—often small and kinship-based—chairpersons must balance diverse member interests. High self-efficacy chairpersons nurture strong leader-member bonds, motivate members toward shared objectives, and instill collective responsibility (Bandura, 1977; Gkypali and Roper, 2024). They confidently tackle challenges and innovate (Ud din Khan et al., 2023; Chen and Zhang, 2024), thereby enhancing competitive advantage. In contrast, low self-efficacy can undermine proactivity and long-term competitiveness. Prior studies link leader self-efficacy to organizational performance (McGee and Terry, 2024; Alshebami, 2023), business success (Hollands et al., 2024; Raza et al., 2024), and competitiveness (McCann et al., 2009). Therefore, consequently, the ensuing hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Chairpersons’ self-efficacy has a positive effect on the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

2.3 The mediating role of organizational resilience

Social cognitive theory posits that self-efficacy drives motivation and behavior by influencing how individuals perceive and mobilize cognitive resources (Bandura, 2001). Extending this to organizational dynamics, leaders’ self-efficacy functions as a microfoundation of dynamic capabilities—translating personal cognition into collective resilience through two mechanisms: cognitive framing and resource orchestration (Helfat and Peteraf, 2015; Eggers and Kaplan, 2013).

First, self-efficacious leaders construct shared cognitive frameworks that institutionalize planned resilience. By setting clear goals and strategies (Huang, 2015; Stroe et al., 2018), they align organizational routines with anticipatory buffers (Rakopoulos, 2014). This mirrors Teece’s (2007) “sensing” dimension of dynamic capabilities, where leader cognition scaffolds organizational foresight.

Second, during disruptions, high self-efficacy enables rapid resource reconfiguration—a hallmark of adaptive resilience. Leaders leverage their agency beliefs to motivate teams (Beck and Schmidt, 2018), pivot resources (Schmitt et al., 2018), and innovate solutions (Yang and Yang, 2022), operationalizing the “seizing” and “transforming” facets of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007).

As Linnenluecke (2017) theorized, resilience represents a form of dynamic capability. If self-efficacy is an invisible cognitive resource, then resilience capabilities translate these resources into advantage (Teece, 2007). High self-efficacy enables chairpersons to mobilize resources effectively for planned and adaptive resilience. Empirical evidence shows self-efficacy indirectly affects performance via resilience (Prayag and Dassanayake, 2023; Djourova et al., 2020). Based on this, we proposes hypothesis 3:

H3a: Planned resilience positively mediates the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

H3b: Adaptive resilience positively mediates the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

2.4 The moderating effects of environmental dynamism

Most studies focus on internal conditions for resilience development (Zhang and Qi, 2021; Wulandhari et al., 2022), with few examining external conditions. Environmental dynamism—unpredictability and volatility in a firm’s environment (Hillmann and Guenther, 2021)—influences adaptive capacity. In China, many farmer cooperatives are small, resource-constrained, and face market competition, demand fluctuations, industry consolidation, and policy shifts (Peng et al., 2020; Muñoz et al., 2020). High external dynamism heightens uncertainty, stress, and risk (Waldman et al., 2001; Gligor et al., 2015), potentially undermining leaders’ confidence in building resilience (Schilke, 2014). Developing resilience in such contexts demands costly, time-intensive, and irreversible resource allocations, which can erode competitiveness.

Conversely, low dynamism environments are more predictable, enabling cooperatives to use established routines and organizational memory to solve recurring issues (Wang et al., 2023). Stable environments let leaders leverage self-efficacy to build resilience more effectively, yielding sustainable advantages. Xiao et al. (2020) found that unstable environments negatively affect relational outcomes. Based on this, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H4a: The mediating effect of planned resilience on the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and cooperative competitive advantage is regulated by environmental dynamism. Through the mediation of planned resilience, the indirect positive association between self-efficacy and cooperative competitive advantage is larger when the amount of environmental dynamism is low.

H4b: The mediating effect of adaptive resilience on the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and cooperative competitive advantage is regulated by environmental dynamism. Through the mediation of adaptive resilience, the indirect positive association between self-efficacy and cooperative competitive advantage is larger when the amount of environmental dynamism is low.

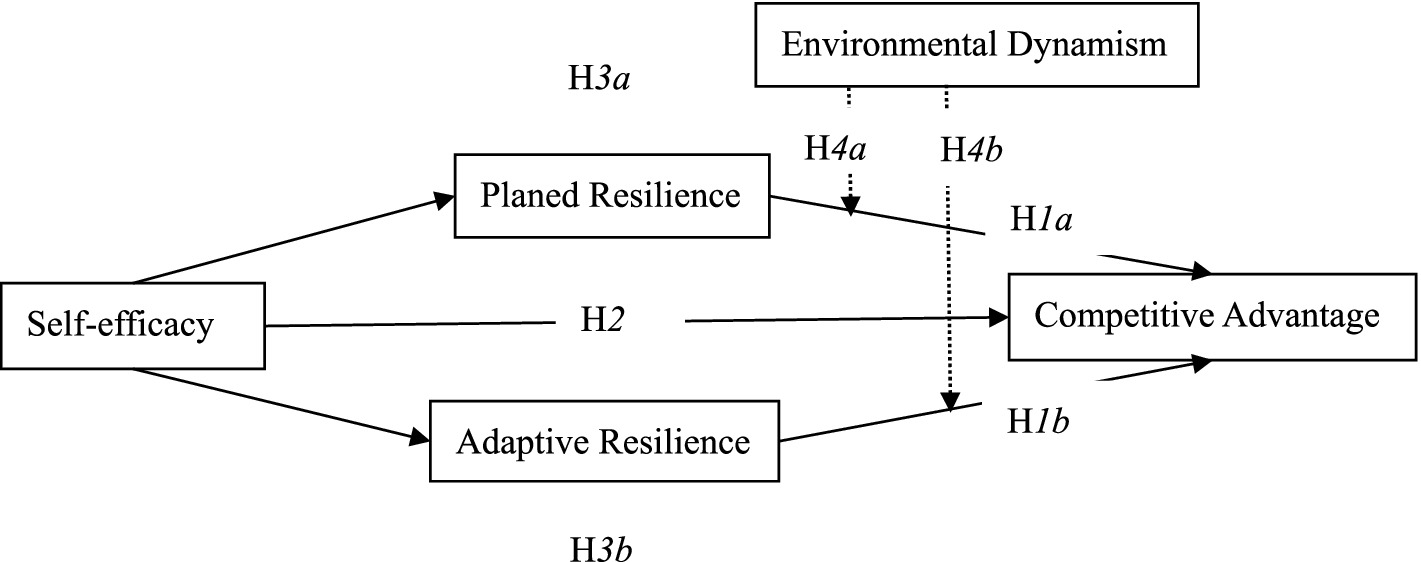

In summary, we proposes a regulated mediation model (see Figure 1) that involves environmental dynamism in the mechanism of self-efficacy’s impact on cooperative competitive advantage through organizational resilience. All the above assumptions are verified through empirical investigation and data analysis of 286 cooperatives.

Figure 1. Research framework. Steeper positive slope indicates that higher planned resilience strengthens the positive impact of environmental dynamism on competitive advantage. Flatter slope suggests reduced effectiveness of environmental dynamism when planned resilience is low.

3 Methodology

3.1 Study area description

Guangdong Province was selected as the survey area for two primary reasons. Guangdong Province was selected as the survey area for two primary reasons. Firstly, Guangdong leads China’s expansion of farmer cooperatives in both quantity and effectiveness. Guangdong had more than 50,000 farmer cooperatives with a total of 72,000 members in 2021, radiation has driven 117,000 farmers into the region, and the average household income of farmers entering the market has increased by more than 3,000 yuan. According to data from the Guangdong Provincial Market Supervision Administration website, in 2023, 8,000 new farmer specialized cooperatives were registered, representing a year-on-year increase of 102.5%; the total number reached 60,000, with both the growth rate and total achieving record highs. Second, to promote the high-quality development of cooperatives, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs selected 30 counties (cities and districts) in 8 provinces in 2018.

Among them, Dabu County, Luoding City, Gaozhou City and Lianzhou City in Guangdong Province were also selected as the first batch of pilot areas. The four cities and counties are distributed in the western and northern regions of Guangdong, where the economic level is quite different and the competitive advantage of cooperatives in different regions is uneven. According to data released on local government websites, in 2024, per capita GDP was approximately ¥35,857 in Dabu County, ¥37,401 in Luoding City, ¥60,932 in Gaozhou City, and ¥49,246 in Lianzhou City, reflecting pronounced regional disparities. Such economic heterogeneity likely contributes to uneven competitive advantages among local cooperatives. Consequently, focusing on cooperatives in these pilot areas provides high credibility and strong representativeness. Findings from these areas offer valuable insights for high-quality cooperative development across other Chinese provinces and comparable developing regions.

3.2 Data collection and sample

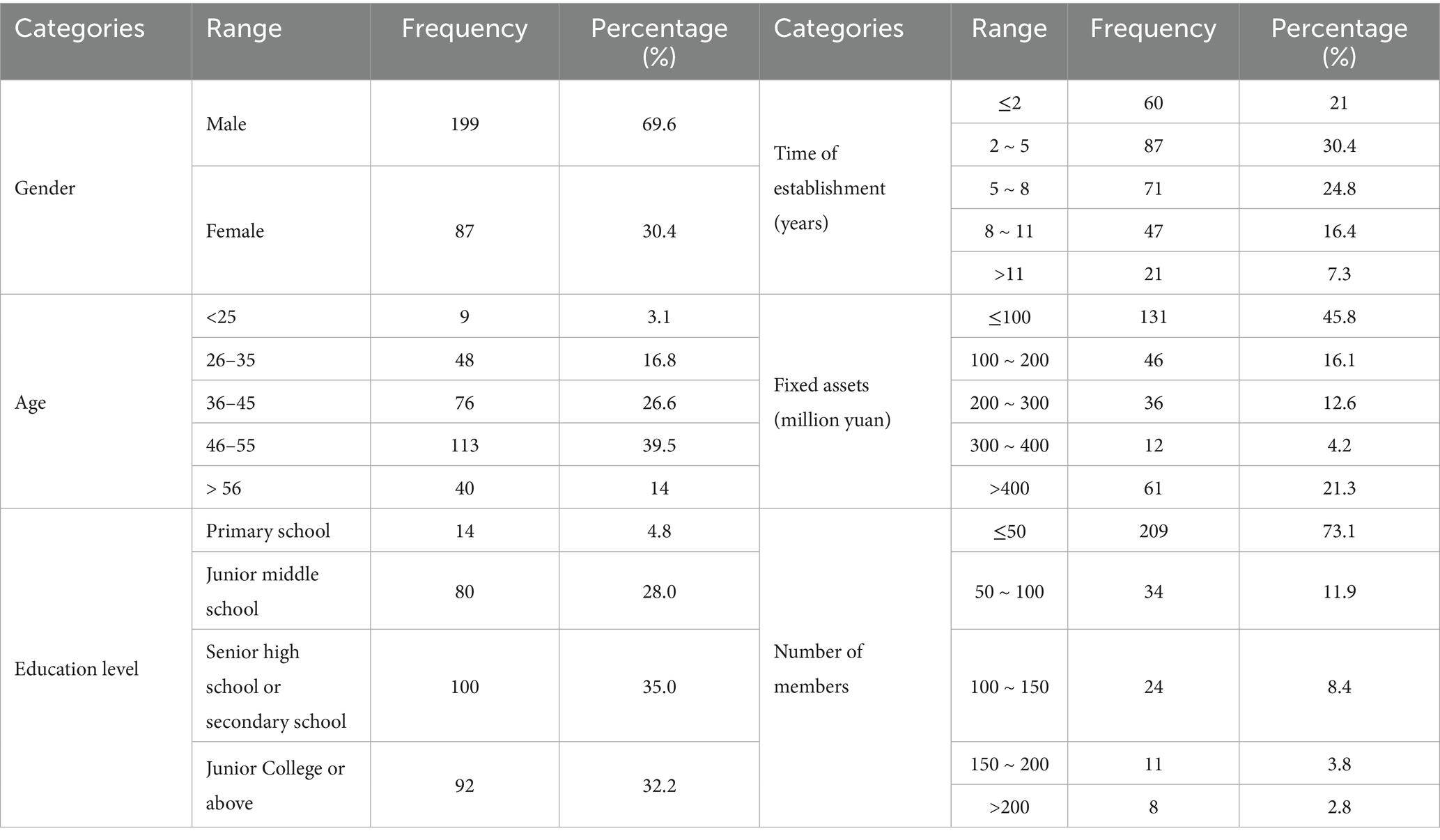

Our study comprised two phases: preliminary exploration and formal inquiry. From April to June 2021, pretests were conducted in Guangzhou and Qingyuan (Guangdong Province) to refine the questionnaire. The formal survey was administered from 2 August to 26 November 2021 by two research teams operating in Dabu County, Luoding City, Gaozhou City, and Lianzhou City. Cooperatives were selected via random sampling, and questionnaires were administered through one-on-one interviews with cooperative chairpersons to ensure comprehensive insight into cooperative operations. Finally, we distributed 320 questionnaires and received 286 valid questionnaires, for an effective rate of 91.1%. The descriptive data of respondents are shown in Table 1.

Among the respondents, 69.6% were male, and most were between 46 and 55 years old (39.5%). A total of 35.0% of respondents had a senior high school or secondary school education level, and 32.2% had a level of junior college or above. In terms of educational attainment, 35.0% had completed senior high school or secondary education, while 32.2% possessed a junior college degree or higher. Regarding the cooperatives’ characteristics, 76.2% were established for less than 8 years, and 23.8% had been in operation for over 8 years, with an average age of 5.86 years. This closely aligns with the average establishment age of 6.3 years reported in the sample cooperatives by Huang et al. (2021), suggesting that our sample is representative. The majority of cooperatives, 45.8%, had fixed assets valued at 100 million or less. The membership size was predominantly small, with 73.1% having 50 members or fewer, and only 26.9% exceeding 50 members, reflecting the typical scale of small cooperatives in China.

3.3 Measures

All variables were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, where responses were scored from “strongly disagree” (assigned a value of one) to “strongly agree” (assigned a value of five) relative to the statements provided.

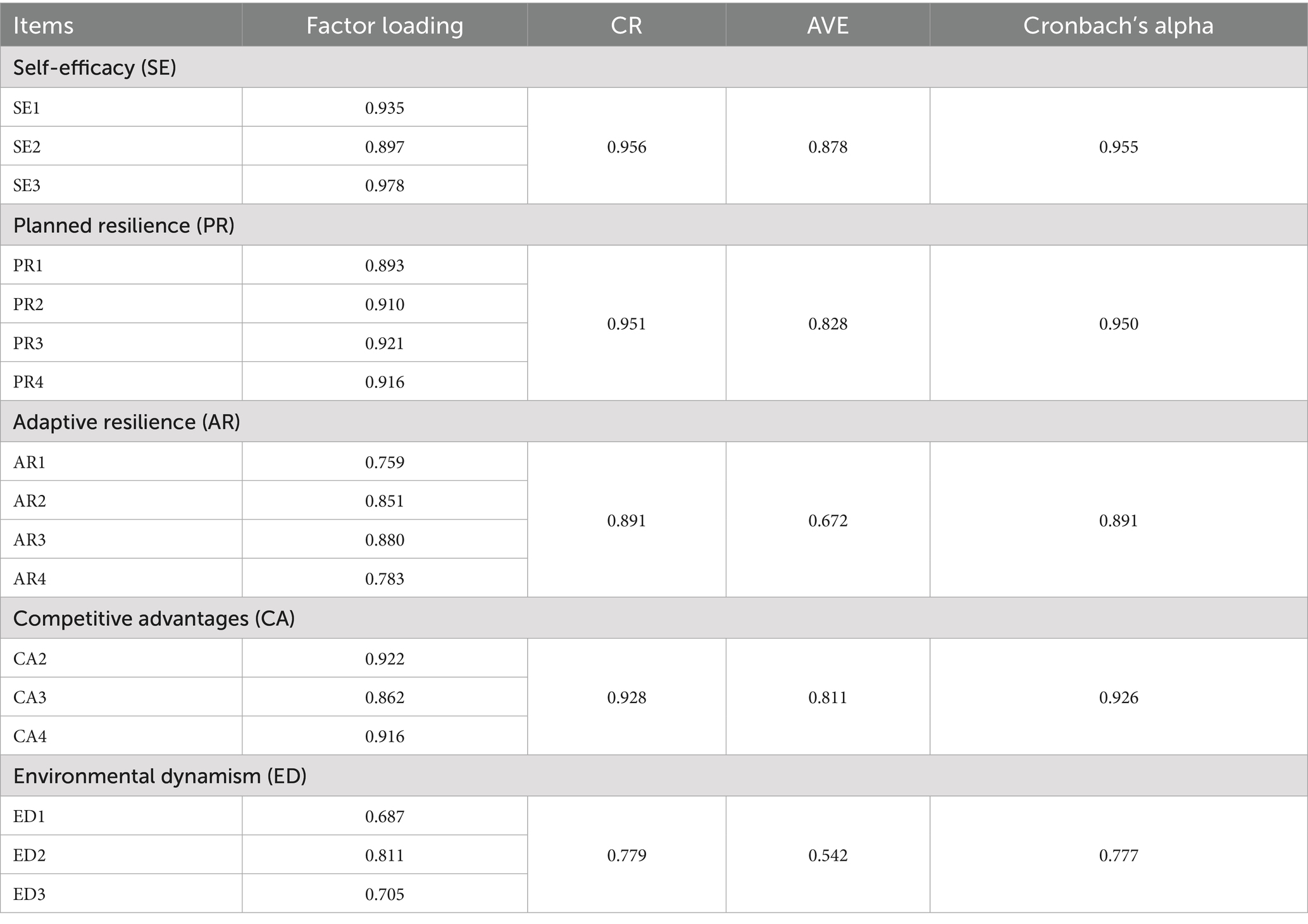

Self-efficacy was gauged using three validated items (labeled SE1 to SE3), which were confirmed by Spreitzer (1995) and Zhu and Liu (2019). The assessment of organizational resilience utilized a scale crafted by Prayag et al. (2020). This construct was evaluated across two dimensions: planned and adaptive resilience. Planned resilience was quantified using four items (designated PR1 to PR4), while adaptive resilience was ascertained through four distinct indicators, each corresponding to elements labeled from AR1 to AR4. According to Wen and Chen (2019), competitive advantage was measured with four items (from CA1 to CA4). In line with Santos-Vijande et al. (2007), we used three items (from ED1 to ED3) to measure environmental dynamism. Table 2 provides a thorough list of the items connected to the research constructs.

3.4 Structural equation modelling

The self-efficacy of chairpersons is a subjective cognitive construct, and organizational resilience and competitive advantage are similarly conceptualized as latent variables that cannot be observed directly. Directly measuring these constructs may introduce subjective biases and measurement error. Structural equation modelling (SEM) is therefore well suited to our study because it simultaneously estimates measurement models (confirming the reliability and validity of multiple-item scales for latent constructs) and structural models (testing hypothesized relationships among those constructs), including mediation and moderation effects (Lowry and Gaskin, 2014). SEM’s capacity to incorporate latent variables within causal frameworks enables us to properly model the indirect effects of self-efficacy on competitive advantage through planned and adaptive resilience (Chin, 1998), as well as the moderating influence of environmental dynamism. Consequently, we have chosen SEM to rigorously test the hypotheses proposed in this study.

4 Results

4.1 Model specification

4.1.1 Reliability and validity tests

The validity and reliability of the data were evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis. Table 2 presents the outcomes. All constructions have composite dependability (CR) values greater than 0.7, with a range of 0.779 to 0.956. This shows that the theoretical construct may be accurately measured as a component of the structural model (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Cronbach’s alpha of the corresponding latent variable after deleting item CA1 increased to higher than 0.7, which was eliminated to enhance the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the scales measuring self-efficacy, planned resilience, adaptive resilience, competitive advantage, and environmental dynamism were 0.955, 0.950, 0.885, 0.926, and 0.777, respectively, all surpassing the benchmark of 0.7. This indicates that the scales possess satisfactory reliability. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.542 to 0.878, indicating strong convergent validity. As presented in Table 3, the square root of AVE for each construct exceeds its inter-construct correlations, thereby confirming discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

4.1.2 Common method bias tests

To ensure rigorous assessment of common method bias, we employed a multi-method approach. First, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted through unrotated exploratory factor analysis (Podsakoff et al., 2003), revealing that the first factor accounted for 45.01% of the variance (below the 50% threshold). Second, we performed marker variable analysis using demographic variables (age and education level) as markers, following the procedure recommended by Lindell and Whitney (2001). The correlations between the marker variables and substantive constructs were negligible (r < 0.12), and the adjusted correlations remained statistically significant. Third, confirmatory factor analysis with a single common method factor yielded poor model fit (χ2/df = 16.185, GFI = 0.562, NFI = 0.560, CFI = 0.574, RFI = 0.497, and RMSEA = 0.231), all below acceptable thresholds (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The multi-method results collectively demonstrate that common method bias does not significantly affect our findings.

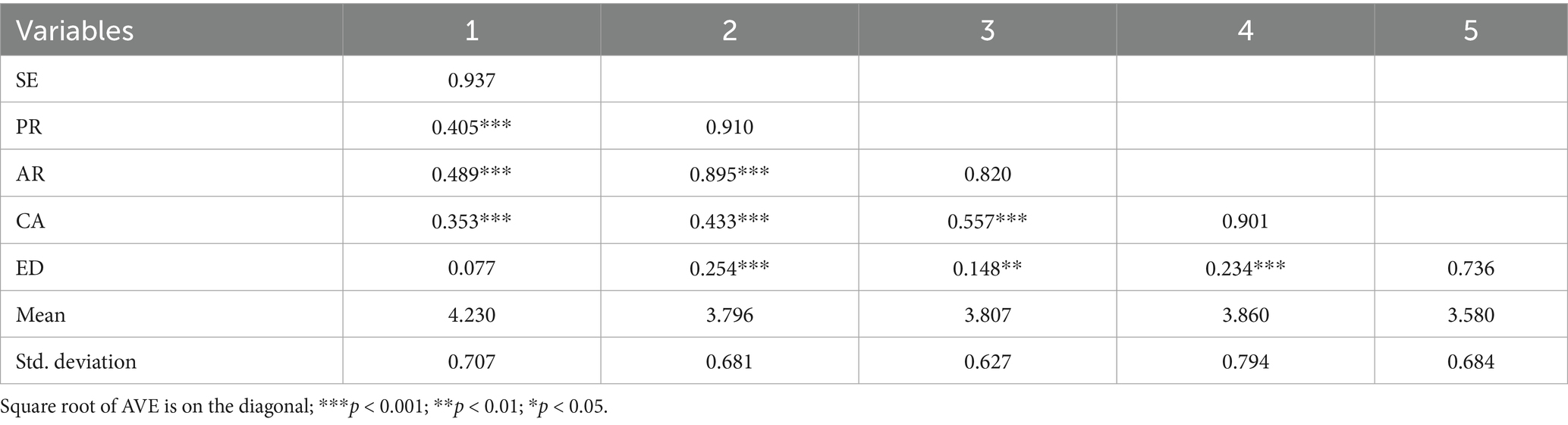

4.1.3 Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

The descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the primary variables are presented in Table 3. The standard deviations fall within the acceptable range, between +1 and −1, and the mean values for the key variables exceed 3. Additionally, positive correlations are observed across all variables. The competitive advantage of cooperatives is notably associated with self-efficacy (r = 0.353, p < 0.001), planned resilience (r = 0.433, p < 0.001), and adaptive resilience (r = 0.557, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-efficacy is significantly correlated with both planned resilience (r = 0.405, p < 0.001) and adaptive resilience (r = 0.489, p < 0.001).

4.2 Hypothesis testing

Prior resilience studies have predominantly focused on enterprises in developed economies (Duchek, 2020; Hillmann, 2021), often overlooking agricultural cooperatives in developing-nation contexts. China, as a major developing economy with a substantial rural and agricultural sector (Hua and Brown, 2024), provides an ideal setting to examine whether established resilience–advantage pathways hold under distinct resource constraints, market volatility, and policy environments. Consequently, in this chapter, we investigate how organizational resilience and chairperson self-efficacy influence competitive advantage in Chinese agricultural cooperatives, thereby addressing a critical gap in the literature.

Adhering to the guidelines proposed by Taylor et al. (2008), we employed structural equation modeling using AMOS 26.0 to assess the effects of organizational resilience on the competitive advantage of cooperatives (Hypothesis 1), the influence of self-efficacy on the competitive advantage of cooperatives (Hypothesis 2), and the mediating role of self-efficacy on organizational resilience (Hypothesis 3).

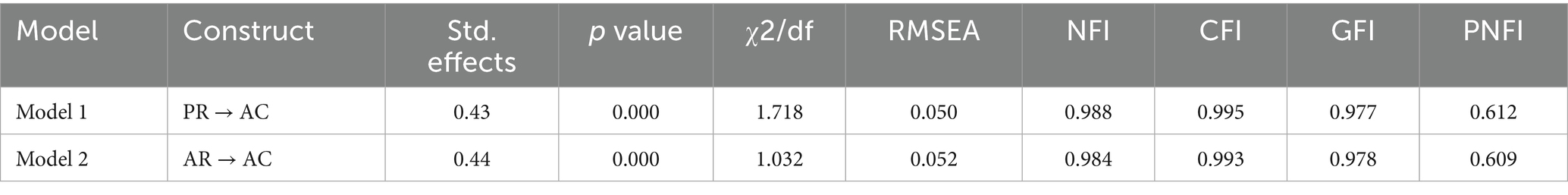

4.2.1 The influence of organizational resilience on the competitive advantage of cooperatives

In the first step, two structural equation models were built to estimate the hypothesized relationships between planned and adaptive resilience and the competitive advantages of cooperatives. By focusing on Chinese agricultural cooperatives-an under-researched developing-nation context-this analysis tests whether resilience effects observed in Western studies (e.g., Sobaih et al., 2021) generalize to China. Overall, the proposed model 1 generally has a satisfactory fit with χ2/df = 1.718, GFI = 0.977, NFI = 0.988, CFI = 0.995, and RMSEA = 0.050. The results of model 2 were well fitted, with χ2/df = 1.032, GFI = 0.978, NFI = 0.984, CFI = 0.993, and RMSEA = 0.052.

The results summarized in Table 4 indicate support for H1a and H1b, implying that cooperative competitive advantage is directly determined by planned resilience (β = 0.43, p < 0.001) and adaptive resilience (β = 0.44, p < 0.001). These findings align with prior evidence from developing-country contexts (Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari, 2013), but extend the literature by demonstrating that adaptive resilience exerts a stronger effect than planned resilience in Chinese agricultural cooperatives. Further analysis of the path coefficients indicates that adaptive resilience has a more significant impact on the competitive advantage of cooperatives than planned resilience. This result is explained by the fact that, under persistent uncertainties-such as fluctuating commodity prices, climatic shocks, and policy shifts in China’s agricultural sector (Borda-Rodriguez et al., 2016)—adaptive resilience enables cooperatives to recover and innovate amid adversity, thereby securing long-term viability.

Table 4. Analysis of the impact of planned and adaptive resilience on the competitive advantage of cooperatives.

4.2.2 The influence of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on the competitive advantage of cooperatives

In the second step, we tested for the direct effect of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on the competitive advantages of cooperatives. The results were well fitted: χ2/df = 2.975, GFI = 0.996, NFI = 0.998, CFI = 1.000, RFI = 0.996, and RMSEA = 0.000.

We find that chairpersons’ self-efficacy is significantly and positively related to competitive advantage (β = 0.35, p < 0.000), thereby supporting H2. This implies that cooperative chairpersons who have greater confidence in their leadership capabilities foster practices—such as strategic decision-making and stakeholder mobilization—that enhance competitive positioning. This result aligns with prior evidence showing that leader self-efficacy fosters strategic decision-making and stakeholder mobilization, which enhance competitive positioning (Khedhaouria et al., 2015). Moreover, our finding counters arguments that structural or environmental factors alone determine cooperative performance (Duchek, 2020), by demonstrating the unique contribution of individual cognitive resources.

4.2.3 Mediating effect of planned and adaptive resilience

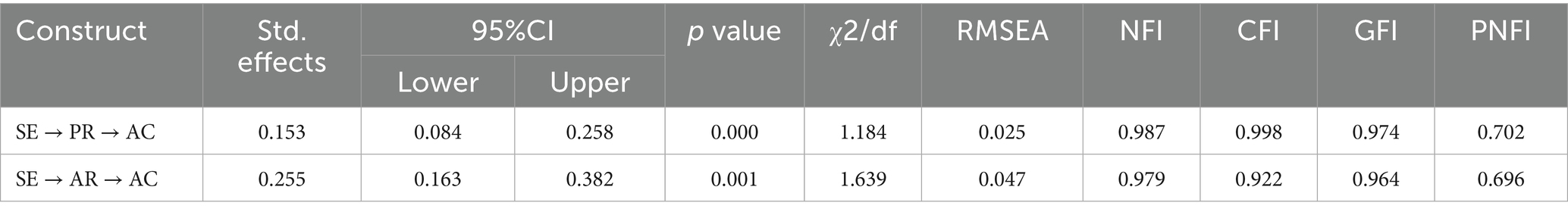

In the third step, planned resilience and adaptive resilience were tested as mediators of the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and cooperative competitive advantage. The planned resilience mediation model exhibits acceptable fit (χ2/df = 1.264, GFI = 0.969, NFI = 0.984, CFI = 0.997, RMSEA = 0.030), as does the adaptive resilience mediation model (χ2/df = 1.639, GFI = 0.964, NFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.922, and RMSEA = 0.047).

The bootstrapping method was employed to further validate the mediating roles of planned and adaptive resilience. Table 5 illustrates that the indirect effect of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on the competitive advantages of cooperatives via planned resilience is 0.16, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.088, 0.263]. Similarly, the indirect effect through adaptive resilience is 0.26, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.163, 0.382]. The exclusion of zero from both confidence intervals supports hypotheses H3a and H3b. These results are consistent with prior findings demonstrating that resilience mediates the positive impact of self-efficacy on organizational outcomes in agricultural and service sectors (Prayag and Dassanayake, 2023). Moreover, this evidence counters views that emphasize only direct effects of self-efficacy on performance without considering resilience as a mechanism (e.g., Khedhaouria et al., 2015), highlighting the critical role of resilience in translating cognitive resources into competitive advantage.

4.2.4 Moderating effects of environmental dynamism

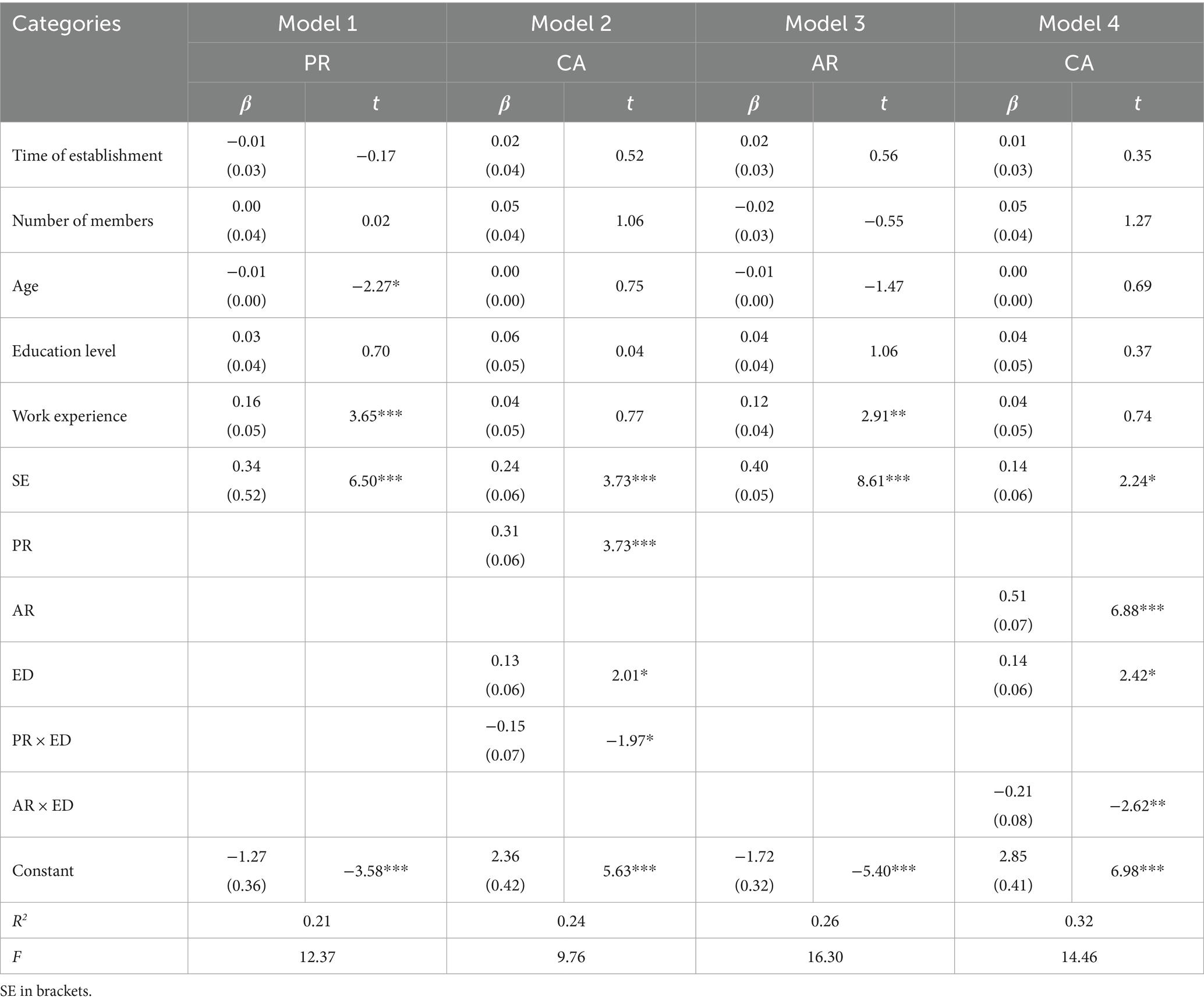

We used Hayes (2013) SPSS PROCESS macro to assess whether environmental dynamism moderates the mediating influence of planned and adaptive resilience on the link between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and competitive advantage. This approach aligns with recommendations to examine context-specific moderation effects (Schilke, 2014; Wulandhari et al., 2022).

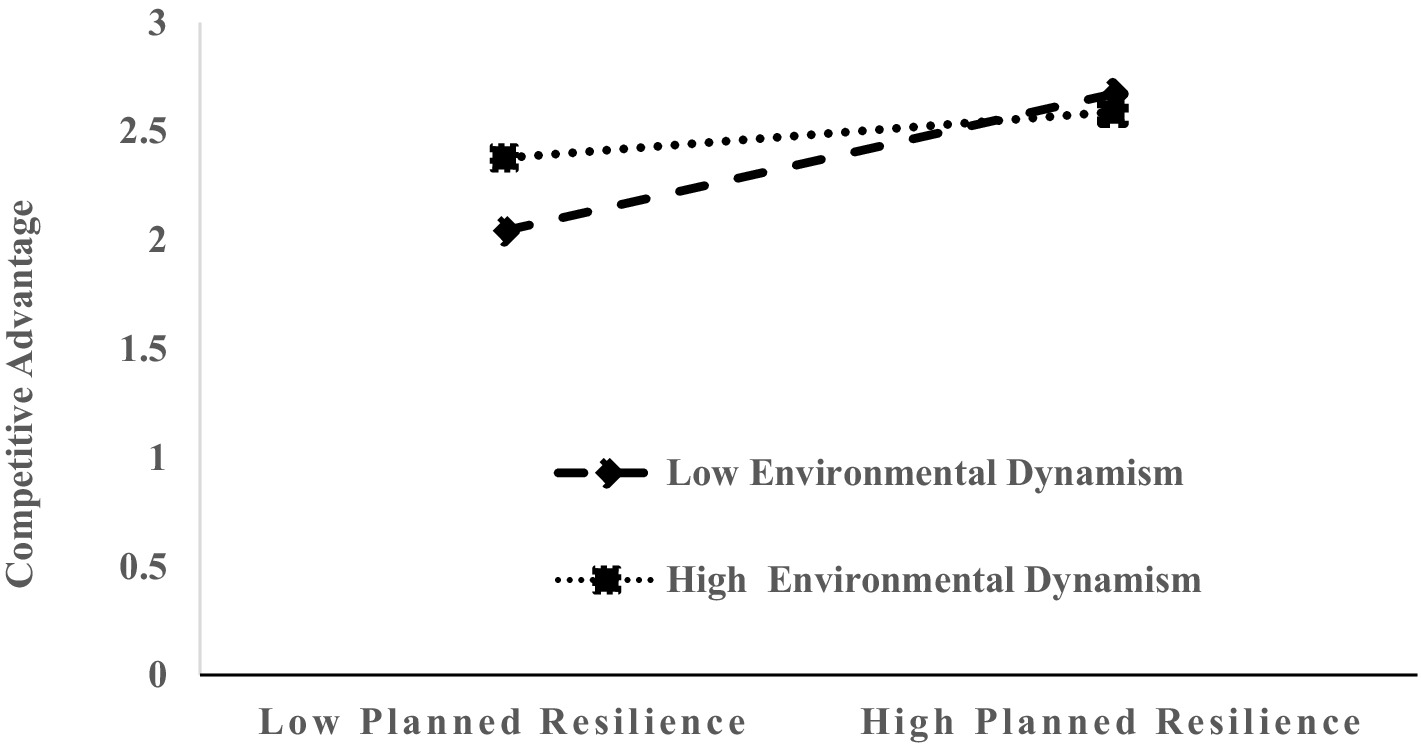

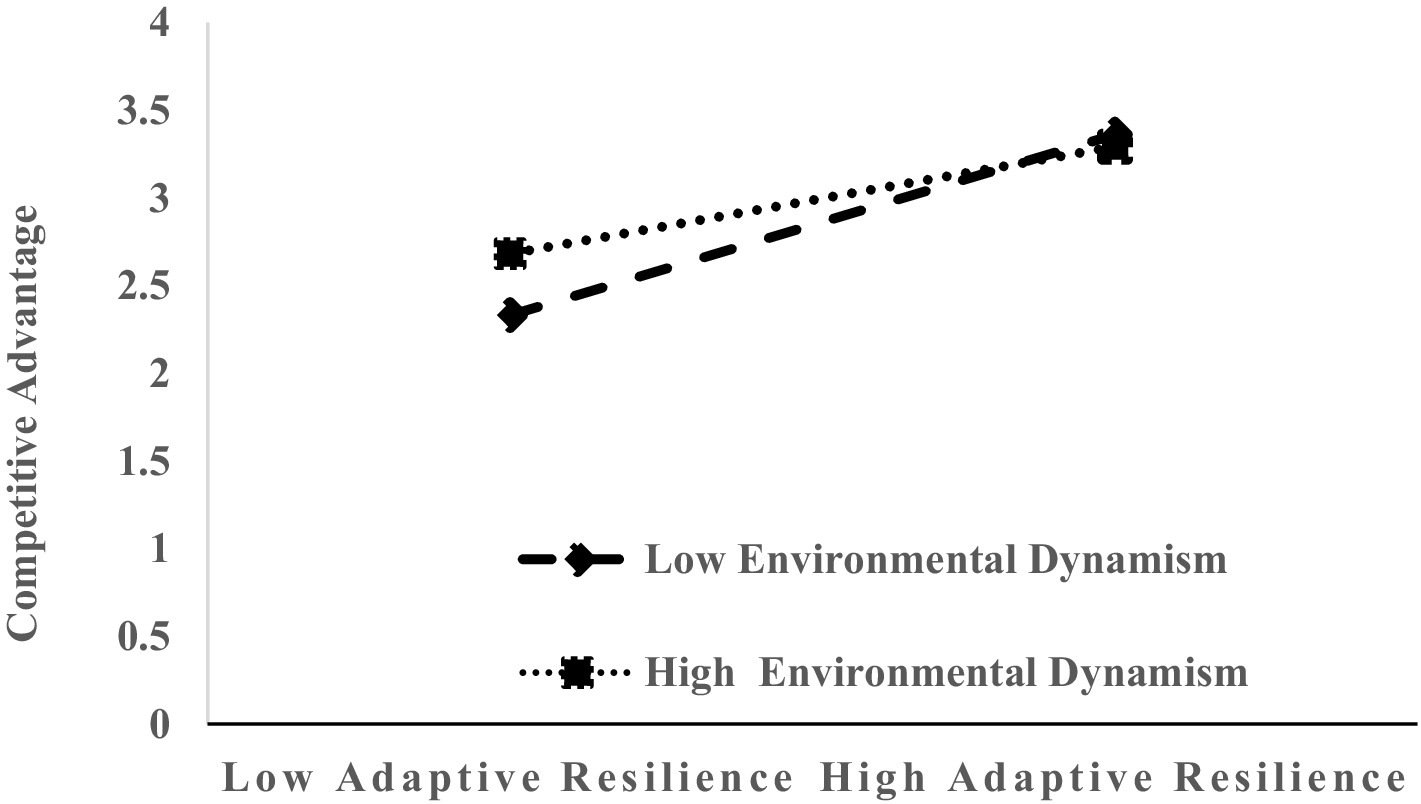

Table 6 shows that chairpersons’ self-efficacy positively affects planned resilience, adaptive resilience, and competitive advantage. Planned and adaptive resilience both positively affect competitive advantage. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that resilience enhances competitive positioning under stable conditions (Sobaih et al., 2021). However, the significant negative interaction terms—planned resilience × environmental dynamism and adaptive resilience ×environmental dynamics—indicate that higher environmental dynamism weakens the positive impact of resilience on competitive advantage. This pattern aligns with Schilke (2014) and Xiao et al. (2020), who reported that environmental volatility attenuates resilience benefits, and it counters propositions that resilience uniformly improves performance irrespective of context (Forliano et al., 2023).

Table 6. The moderating effect of environmental dynamics on the mediating effect of organizational resilience between self-efficacy and competitive advantage.

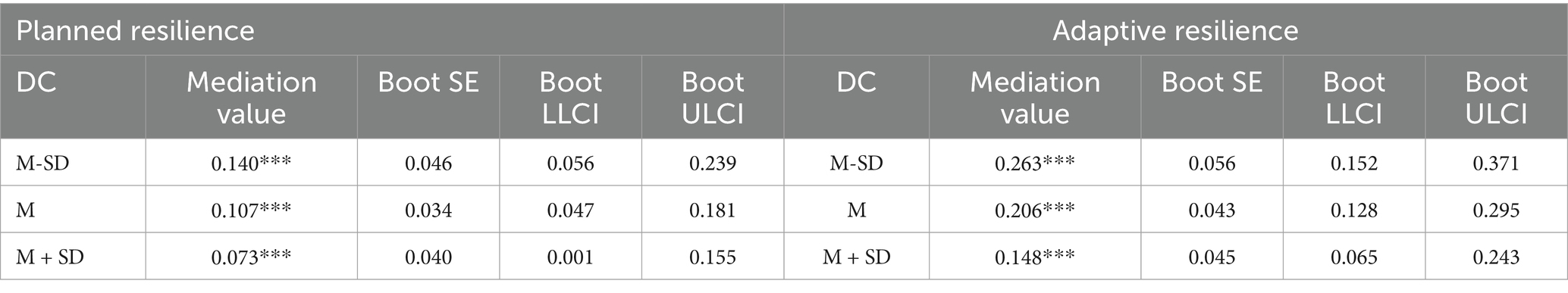

Next, we probed the moderated mediation across three levels of environmental dynamism (mean±1 SD). As shown in Table 7, the mediating effect of planned resilience on the relationship between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and competitive advantage was found to be positively significant at all three levels of environmental dynamism. These results corroborate moderated mediation findings in other sectors (Prayag and Dassanayake, 2023) but run counter to assertions that planned resilience’s indirect effect remains constant across varying environmental conditions (Wulandhari et al., 2022). Similarly, an analysis was performed to assess the moderating influence of environmental dynamism on the mediating role of adaptive resilience between chairpersons’ self-efficacy and competitive advantage. The results shown in Table 6 reveal that environmental dynamism significantly moderates the indirect effect of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on competitive advantage through adaptive resilience. This outcome supports earlier evidence that adaptive resilience’s benefits diminish under turbulent conditions (Hua and Brown, 2024) and contradicts views that adaptive resilience’s mediation effect is invariant to environmental context (Borda-Rodriguez et al., 2016). Consequently, both Hypothesis 4a and Hypothesis 4b are substantiated. Among the control variables, chairpersons’ work experience is significantly related to planned resilience (β = 0.16, p < 0.001) and competitive advantage (β = 0.12, p < 0.01).

Figures 2, 3 graphically depict these interactions, illustrating that under high environmental dynamism—exacerbated by COVID-19 market disruptions—cooperatives struggle to leverage resilience effectively, leading to weaker competitive positioning or even closures due to insufficient surplus for resilience-building. In contrast, under low dynamism, resilience mechanisms translate more robustly into advantage.

Figure 2. The interactive effect of planned resilience and environmental dynamism on competitive advantage. Steeper positive slope denotes that adaptive resilience amplifies the positive relationship between environmental dynamism and competitive advantage. Flatter slope suggests reduced effectiveness of environmental dynamism when adaptive resilience is low.

Figure 3. The interactive effect of adaptive resilience and environmental dynamism on competitive advantage.

5 Discussion

The competitive environment demands that cooperatives consider organizational resilience to survive crises. However, resilience often coexists with flexibility and short-termism, creating paradoxes in dynamic settings where long-term stability and rapid adaptation may conflict. As leaders, chairpersons play a pivotal role in cooperative management. Grounded in social cognitive theory and dynamic capabilities theory, this study uses survey data from 286 cooperatives in Guangdong Province, China, to examine how chairperson self-efficacy influences competitive advantage through organizational resilience.

First, we establish that in China, chairperson self-efficacy significantly enhances cooperative competitive advantage. Chairpersons with high self-efficacy set ambitious goals, persist through setbacks, and promptly regain confidence after failure, which boosts job satisfaction. This aligns with Palmer et al. (2019) and extends understanding of self-efficacy’s role in cooperative growth.

Second, organizational resilience contributes to competitive advantage. Resilient cooperatives anticipate disruptions and enact early responses (Mollenkopf et al., 2022), while their adaptive capacity reshapes core competencies for sustained advantage (Fathi et al., 2021). This duality reflects the tension between planned preparedness and flexible adaptation.

Third, building on self-efficacy’s direct effect, we show how high self-efficacy bolsters resilience. Effective leaders maintain clear direction and assess vulnerabilities objectively, deploying innovative strategies during crises. Their confidence in risk-taking and strategy adjustment underlines the connection between self-efficacy and resilience. In China’s dynamic agricultural market—shaped by collectivist norms and policy incentives for rapid response—adaptive resilience often surpasses planned resilience, as cultural emphasis on communal problem-solving and government support for agile interventions enable faster recovery. Thus, chairpersons with strong self-efficacy enhance both forms of resilience, but adaptive resilience yields a greater competitive edge under these cultural and policy conditions.

Fourth, environmental dynamism significantly moderates the link between organizational resilience and competitive advantage. This clarifies when resilience translates into advantage. We tested the moderating effect of dynamism on both resilience’s mediating role and its direct impact on competitive advantage. Following Barreto (2010), we compared resilience outcomes under low- and high-dynamism conditions. Results show that even in highly dynamic environments, both planned and adaptive resilience remain positively associated with competitive advantage. This contradicts Schilke (2014), who argued that dynamic capabilities cannot deliver advantage under such volatility. Cooperatives, being more vulnerable and resource-limited than larger firms, often rely on short-term plans that can be quickly recombined into new strategies. However, resilience’s effectiveness declines as dynamism increases, indicating that its strongest benefit occurs under lower dynamism.

6 Theoretical implications and managerial implications

6.1 Theoretical implications

Our research provides several contributions for theory. First, we extends social cognition theory to explore important antecedents of the competitive advantage of cooperatives. Our research found that chairpersons’ sense of self-efficacy, as a positive psychological cognition, can transform the existing psychological quality into the competitive advantage of cooperatives. The views of our paper can provide policy references for the managers of cooperatives so that they can better understand and reflect on their sense of self-efficacy, thus helping cooperatives achieve sustainable competitive advantage.

Second, we draw on the “resource-capability-advantage” framework of RBV (Barney, 1991), our research found that a high perceived self-efficacy can increase chairpersons’ motivation and stress tolerance, making them more resilient to obstacles and setbacks and boosting organizational resilience and performance achievements. In conclusion, the validation of RBV’s “resource-capability-advantage” concept inside the framework of cooperatives enriches our understanding of the mechanism through which cognitive theory influences organizational competitive advantage.

Third, our research reveals the moderating influence of environmental dynamism on the relationship between planned resilience and the competitive advantage of cooperatives, as well as between adaptive resilience and the competitive advantage of cooperative relationships. These findings provide valuable insights into how cooperatives can strategically adjust the focus and intensity of leveraging organizational resilience to impact their competitive advantage, contingent upon the level of environmental dynamism they face. Hillmann and Guenther (2021) have shown that resilience frequently interacts closely with the conditions of its external environment. This demonstrates that environmental factors cannot be ignored in the promotion of cooperative capacity, and this finding has certain theoretical contributions.

6.2 Managerial implications

Empirically our research provides suggestions to the policymakers: Cooperatives should emphasize the development of self-efficacy in chairpersons through training and practice to enhance their ability to set challenging goals, be resilient in the face of difficulties and recover quickly from failure. High leader self-efficacy contributes to higher job satisfaction and organizational performance, which positively impacts the cooperative’s long-term competitive advantage. Second, co-operatives need to develop and strengthen planned and adaptive resilience to cope with environmental uncertainty and turbulence. By developing flexible plans and strategies, cooperatives are better able to anticipate and adapt to changes in the environment, maintain business continuity and recover quickly from crises, thereby enhancing their competitive advantage. Third, cooperatives should pay close attention to environmental dynamics and adjust their resilience strategies in response to changes in the environment. When environmental turbulence intensifies, cooperatives should pay more attention to short-term planning and rapid response capabilities in order to utilize existing resources and plans to make new combinations and respond quickly to market changes. At the same time, cooperatives should recognize that the effectiveness of planned and adaptive resilience may diminish under high environmental dynamics, and therefore require more flexible and innovative strategies to maintain and enhance competitive advantage.

7 Limitations and future research

Although our research contributes to both theory and practice, several limitations warrant consideration.

First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to infer causality among chairpersons’ self-efficacy, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to clarify temporal and causal dynamics.

Second, while our study focuses on Chinese agricultural cooperatives, the mechanisms linking chairpersons’ self-efficacy, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage may extend beyond this context. In many developing nations—such as those in Africa and Southeast Asia—smallholder cooperatives face similar resource constraints, policy uncertainties, and market volatility, suggesting that self-efficacy–driven resilience could likewise enhance competitive positioning. However, local governance structures, community norms, and regulatory environments differ, so empirical validation in these regions is necessary. Similarly, non-agricultural cooperatives (e.g., credit unions or consumer cooperatives) operate under distinct sectoral dynamics—such as financial regulations or service delivery imperatives—which may moderate the resilience pathways identified here. Finally, public–private partnerships (PPPs) and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often function under hybrid governance models, blending profit motives and stakeholder accountability. In those settings, self-efficacy and resilience remain relevant but may interact with factors like regulatory oversight or public mandates in ways that differ from purely member-driven cooperatives. We encourage future research to test our model across these varied contexts to clarify its boundary conditions and inform tailored strategies.

Third, the determinants of organizational resilience are multifaceted, and this study cannot cover all potential antecedents. Subsequent investigations could examine digital leadership as an antecedent of resilience, exploring how technology-driven leadership styles influence cooperative adaptability. Fourth, our focus on traditional farmer cooperatives overlooks governance structures in multi-stakeholder cooperatives. Future research could explore resilience pathways in multi-stakeholder settings to reveal how diverse member interests shape resilience and performance. Finally, other contextual factors—such as social capital and cultural norms—merit deeper investigation to build a more comprehensive model of resilience and competitive advantage.

8 Conclusion

Our research constructs an integrative framework to investigate the determinants of competitive advantage within cooperatives. The empirical findings reveal that both chairpersons’ self-efficacy and organizational resilience positively influence the competitive edge of cooperatives. Furthermore, the impact of chairpersons’ self-efficacy on the competitive advantage is partially mediated by planned and adaptive resilience. Additionally, environmental dynamism negatively moderates the mediating roles of both planned and adaptive resilience. Consequently, we enhances our comprehension of the sustained competitive advantage in cooperatives, bridging a research gap and extending the applicability of institutional theory. The insights gleaned from our research offer valuable guidance to policymakers and cooperative practitioners, particularly those from developing nations and the agricultural sector, thus propelling the high-quality development of cooperatives and advancing agricultural progress in these countries.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JiW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JuW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund Project of China (grant number 21&ZD090), the Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 2024A1515011302), the Scientific Research Start-up Funds Project of Guangdong Ocean University (grant number YJR24007).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alshebami, A. S. (2023). Green innovation, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial orientation and economic performance: interactions among Saudi small enterprises. Sustainability 15:1961. doi: 10.3390/su15031961

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., and Rouziou, M. (2021). Weathering a crisis: a multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 47, 864–892. doi: 10.1177/10422587211046545

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., and Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: a positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 48, 677–693. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20294

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 17, 99–120. doi: 10.1016/S0742-3322(00)17018-4

Barreto, I. (2010). Dynamic capabilities: a review of past research and an agenda for the future. J. Manage. 36, 256–280. doi: 10.1177/0149206309350776

Beck, J. W., and Schmidt, A. M. (2018). Negative relationships between self-efficacy and performance can be adaptive: the mediating role of resource allocation. J. Manage. 44, 555–588. doi: 10.1177/0149206314567778

Bernacki, M. L., Nokes-Malach, T. J., and Aleven, V. (2015). Examining self-efficacy during learning: variability and relations to behavior, performance, and learning. Metacogn. Learn. 10, 99–117. doi: 10.1007/s11409-014-9127-x

Borda-Rodriguez, A., Johnson, H., Shaw, L., and Vicari, S. (2016). What makes rural co-operatives resilient in developing countries? J. Int. Dev. 28, 89–111. doi: 10.1002/jid.3125

Borda-Rodriguez, A., and Vicari, S. (2013). Understanding rural co-operative resilience: a literature review. (IKD Working Paper No. 64), Co-operative College and Open University. Available at: https://university.open.ac.uk/ikd/publications/working-papers (Accessed May 4, 2018).

Božović, T., Blešić, I., Nedeljković-Knežević, M., Đeri, L., and Pivac, T. (2021). Resilience of tourism employees to changes caused by COVID-19 pandemic. J. Geograph. Inst. 71, 181–194. doi: 10.2298/ijgi2102181b

Bürgel, T. R., Hiebl, M. R., and Pielsticker, D. I. (2023). Digitalization and entrepreneurial firms’ resilience to pandemic crises: evidence from COVID-19 and the German Mittelstand. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 186:122135. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122135

Chen, X., and Zhang, S. X. (2024). Too much of two good things: the curvilinear effects of self-efficacy and market validation in new ventures. J. Bus. Res. 183:114845. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114845

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 295, 295–336.

De Matteis, J., Elia, G., and Del Vecchio, P. (2023). Business continuity management and organizational resilience: a small and medium enterprises (SMEs) perspective. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 31, 670–682. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12470

Djourova, N. P., Rodríguez Molina, I., Tordera Santamatilde, N., and Abate, G. (2020). Self-efficacy and resilience: mediating mechanisms in the relationship between the transformational leadership dimensions and well-being. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 27, 256–270. doi: 10.1177/1548051819849002

Dong, H., and Wang, Y. Q. (2018). Analysis of the status and problems concerning the development of farmer professional cooperatives in China and possible countermeasures. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. 35, 106–109. doi: 10.13727/j.cnki.53-1191/c.2018.02.015 (in Chinese).

Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 13, 215–246. doi: 10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

Eggers, J. P., and Kaplan, S. (2013). Cognition and capabilities: a multi-level perspective. Acad. Manage. Ann. 7, 295–340. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2013.769318

Fathi, M., Yousefi, N., Vatanpour, H., and Peiravian, F. (2021). The effect of organizational resilience and strategic foresight on firm performance: competitive advantage as mediating variable. Iran. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 20, 497–510. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2021.116145.15723

Florez-Jimenez, M. P., Lleo, A., Ruiz-Palomino, P., and Muñoz-Villamizar, A. F. (2025). Corporate sustainability, organizational resilience, and corporate purpose: a review of the academic traditions connecting them. Rev. Manag. Sci. 19, 67–104. doi: 10.1007/s11846-024-00735-3

Forliano, C., Orlandi, L. B., Zardini, A., and Rossignoli, C. (2023). Technological orientation and organizational resilience to Covid-19: the mediating role of strategy’s digital maturity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 188:122288. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122288

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Francesconi, N., Wouterse, F., and Birungi Namuyiga, D. (2021). Agricultural cooperatives and COVID-19 in Southeast Africa. The role of managerial capital for rural resilience. Sustainability 13:1046. doi: 10.3390/su13031046

Giagnocavo, C., Galdeano-Gómez, E., and Pérez-Mesa, J. C. (2018). Cooperative longevity and sustainable development in a family farming system. Sustainability 10:2198. doi: 10.3390/su10072198

Gkypali, A., and Roper, S. (2024). Innovation and sales growth intentions among the solopreneurs: the role of experience and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 200:123201. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123201

Gligor, D. M., Esmark, C. L., and Holcomb, M. C. (2015). Performance outcomes of supply chain agility: when should you be agile? J. Oper. Manag. 33, 71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2014.10.008

Gupta, V., MacMillan, I. C., and Surie, G. (2004). Entrepreneurial leadership: developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. J. Bus. Venturing 19, 241–260. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00040-5

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., and Harms, P. D. (2008). Leadership efficacy: review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 19, 669–692. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.09.007

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Helfat, C. E., and Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 36, 831–850. doi: 10.1002/smj.2247

Hillmann, J. (2021). Disciplines of organizational resilience: contributions, critiques, and future research avenues. Rev. Manag. Sci. 15, 879–936. doi: 10.1007/s11846-020-00384-2

Hillmann, J., and Guenther, E. (2021). Organizational resilience: a valuable construct for management research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 23, 7–44. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12239

Hollands, L., Haensse, L., and Lin-Hi, N. (2024). The how and why of organizational resilience: a mixed-methods study on facilitators and consequences of organizational resilience throughout a crisis. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 60, 449–493. doi: 10.1177/00218863231165785

Houston, L., Kraimer, M., and Schilpzand, P. (2025). The motivation to be inclusive: understanding how diversity self-efficacy impacts leader effectiveness in racially diverse workgroups. Group Organ. Manag. 50, 983–1019. doi: 10.1177/10596011231200929

Hua, H. H., and Brown, P. R. (2024). Social capital enhances the resilience of agricultural cooperatives: comparative case studies in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. World Dev. Sustain. 5:100170. doi: 10.1016/j.wds.2024.100170

Huang, J. (2015). How the entrepreneur of farmers’ cooperatives form social entrepreneurship intention: a theoretical model and empirical study. J Agrotech Econ 12, 4–15. (Chinese)

Huang, Y., Li, X., and Zhang, G. (2021). The impact of technology perception and government support on e-commerce sales behavior of farmer cooperatives: evidence from liaoning province, China. Sage Open. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/21582440211015

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, Z., Zhang, Q. F., and Donaldson, J. (2023). Why do farmers’ cooperatives fail in a market economy? Rediscovering Chayanov with the Chinese experience. J. Peasant Stud. 50, 2611–2641. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2022.2104159

Ireland, R. D., Hitt, M. A., and Sirmon, D. G. (2003). A model of strategic entrepreneurship: the construct and its dimensions. J. Manage. 29, 963–989. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00086-2

Jiang, M., Li, J., and Mi, Y. (2024). Farmers’ cooperatives and smallholder farmers’ access to credit: evidence from China. J. Asian Econ. 92:101746. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2024.101746

Kahn, W. A., Barton, M. A., Fisher, C. M., Heaphy, E. D., Reid, E. M., and Rouse, E. D. (2018). The geography of strain: organizational resilience as a function of intergroup relations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 43, 509–529. doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0004

Khedhaouria, A., Gurău, C., and Torrès, O. (2015). Creativity, self-efficacy, and small-firm performance: the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Small Bus. Econ. 44, 485–504. doi: 10.1007/s11187-014-9608-y

Kunz, J., and Sonnenholzner, L. (2023). Managerial overconfidence: promoter of or obstacle to organizational resilience? Rev. Manag. Sci. 17, 67–128. doi: 10.1007/s11846-022-00530-y

Liang, L., and Li, Y. (2024). How does organizational resilience promote firm growth? The mediating role of strategic change and managerial myopia. J. Bus. Res. 177:114636. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114636

Lindell, M. K., and Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 114–121. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

Lin, J., and Fan, Y. (2024). Seeking sustainable performance through organizational resilience: examining the role of supply chain integration and digital technology usage. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 198:123026. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2023.123026

Linnenluecke, M. K. (2017). Resilience in business and management research: a review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 19, 4–30. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12076

Li, Q., Wang, M., and Xiangli, L. (2021). Do government subsidies promote new-energy firms’ innovation? Evidence from dynamic and threshold models. J. Clean. Prod. 286:124992. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124992

Liu, Y., Cao, L., Wang, Y., and Liu, E. (2024). Viability, government support and the service function of farmer professional cooperatives—evidence from 487 cooperatives in 13 cities in Heilongjiang, China. Agriculture 14:616. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14040616

Li, X., and Ito, J. (2024). Multiple roles of agricultural cooperatives in improving farm technical efficiency: a case study of rural Gansu, China. Agribusiness 41, 424–444. doi: 10.1002/agr.21901

Lowry, P. B., and Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: when to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 57, 123–146. doi: 10.1109/TPC.2014.2312452

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., and Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital: developing the human competitive edge. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Martín-Rojas, R., Garrido-Moreno, A., and García-Morales, V. J. (2023). Social media use, corporate entrepreneurship and organizational resilience: a recipe for SMEs success in a post-Covid scenario. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 190:122421. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122421

Martos-Pedrero, A., Cortés-García, F. J., Abad-Segura, E., and Belmonte-Ureña, L. J. (2025). Internationalization, innovation, and resilience: financial performance of agricultural cooperatives in southeastern Spain’s rural economy. J. Rural. Stud. 117:103682. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2025.103682

McCann, J., Selsky, J., and Lee, J. (2009). Building agility, resilience and performance in turbulent environments. People Strat. 32, 44–51.

McGee, J. E., and Terry, R. P. (2024). COVID-19 as an external enabler: the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation. J. Small Bus. Manage. 62, 1058–1083. doi: 10.1080/00472778.2022.2127746

Mollenkopf, D. A., Peinkofer, S. T., and Chu, Y. (2022). Supply chain transparency: consumer reactions to incongruent signals. J. Oper. Manag. 68, 306–327. doi: 10.1002/joom.1180

Muñoz, P., Kimmitt, J., and Dimov, D. (2020). Packs, troops and herds: prosocial cooperatives and innovation in the new normal. J. Manage. Stud. 57, 470–504. doi: 10.1111/joms.12542

Nakanishi, H., Black, J., and Matsuo, K. (2014). Disaster resilience in transportation: Japan earthquake and tsunami 2011. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 5, 341–361. doi: 10.1108/IJDRBE-12-2012-0039

Ostadi, I. M., and Soleimon, P. M. (2017). The relationship between the organizational resilience and the competitiveness and sustainable competitive (the case study: cement company of Bojnord). Future Study Manag. 28, 103–125.

Paglis, L. L., and Green, S. G. (2002). Leadership self-efficacy and managers’ motivation for leading change. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 215–225. doi: 10.1002/job.137

Palanikumar, M., Kausar, N., Garg, H., Kadry, S., and Kim, J. (2023). Robotic sensor based on score and accuracy values in q-rung complex diophatine neutrosophic normal set with an aggregation operation. Alex. Eng. J. 77, 149–164. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2023.06.064

Palmer, C., Niemand, T., Stöckmann, C., Kraus, S., and Kailer, N. (2019). The interplay of entrepreneurial orientation and psychological traits in explaining firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 94, 183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.005

Peng, X., Liang, Q., Deng, W., and Hendrikse, G. (2020). CEOs versus members’ evaluation of cooperative performance: evidence from China. Soc. Sci. J. 57, 219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.01.006

Peter, L. P., and Zhu, J. Z. (2021). A literature review of organizational resilience. Foreign Econ. Manag. 43, 25–41. doi: 10.16538/j.cnki.fem.20210122.101 (Chinese).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prayag, G., and Dassanayake, D. C. (2023). Tourism employee resilience, organizational resilience and financial performance: the role of creative self-efficacy. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 2312–2336. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2022.2108040

Prayag, G., Ozanne, L. K., and de Vries, H. (2020). Psychological capital, coping mechanisms and organizational resilience: insights from the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 34:100637. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100637

Qu, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Ma, X., Wei, G., and Kong, X. (2023). The future of agriculture: obstacles and improvement measures for Chinese cooperatives to achieve sustainable development. Sustainability 15:974. doi: 10.3390/su15020974

Rakopoulos, T. (2014). The crisis seen from below, within, and against: from solidarity economy to food distribution cooperatives in Greece. Dialect. Anthropol. 38, 189–207. doi: 10.1007/s10624-014-9342-5

Raza, T., Ali, S. A., and Majeed, M. U. (2024). Transformational leadership and project success: the roles of social capital and self-efficacy. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 31, 335–371. doi: 10.32890/ijms2024.31.1.12

Santoro, G., Bertoldi, B., Giachino, C., and Candelo, E. (2020). Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurial resilience and success: the moderating role of stakeholders’ engagement. J. Bus. Res. 119, 142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.052

Santos-Vijande, M. L., and Álvarez-González, L. I. (2007). Innovativeness and organizational innovation in total quality oriented firms: the moderating role of market turbulence. Technovation. 27, 514–532. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2007.05.014

Schilke, O. (2014). On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage: the nonlinear moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Strateg. Manage. J. 35, 179–203. doi: 10.1002/smj.2099

Schmitt, A., Rosing, K., Zhang, S. X., and Leatherbee, M. (2018). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial uncertainty and business opportunity identification: exploration as a mediator and entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a moderator. Entrep. Theory Pract. 42, 835–859. doi: 10.1177/1042258717721482

Serdyukov, S., and Grima, F. (2025). Building an agreement in a farming cooperative governance: a sociology of conventions approach. Eur. Manag. J. 43, 89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2024.01.001

Sinha, R. P., and Edalatpanah, S. A. (2023). Efficiency and fiscal performance of Indian states: an empirical analysis using network DEA. J. Oper. Strateg. Anal. 1, 1–7. doi: 10.56578/josa010101

Sobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I., Hasanein, A. M., and Abdelaziz, A. S. (2021). Responses to COVID-19: the role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 94:102824. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102824

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 1442–1465. doi: 10.2307/256865

Stoverink, A. C., Kirkman, B. L., Mistry, S., and Rosen, B. (2020). Bouncing back together: toward a theoretical model of work team resilience. Acad. Manag. Rev. 45, 395–422. doi: 10.5465/amr.2017.0005

Stroe, S., Parida, V., and Wincent, J. (2018). Effectuation or causation: an fsQCA analysis of entrepreneurial passion, risk perception, and self-efficacy. J. Bus. Res. 89, 265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.035

Taylor, A. B., MacKinnon, D. P., and Tein, J. Y. (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 11, 241–269. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300344

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manage. J. 28, 1319–1350. doi: 10.1002/smj.640

Trieu, H. D., Nguyen, P. V., Tran, K. T., Vrontis, D., and Ahmed, Z. (2024). Organisational resilience, ambidexterity and performance: the roles of information technology competencies, digital transformation policies and paradoxical leadership. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 32, 1302–1321. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-05-2023-3750

Ud din Khan, H. S., Li, P., Chughtai, M. S., Mushtaq, M. T., and Zeng, X. (2023). The role of knowledge sharing and creative self-efficacy on the self-leadership and innovative work behavior relationship. J. Innov. Knowl. 8:100441. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2023.100441

Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J., and Puranam, P. (2001). Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 44, 134–141.

Wang, J., Wan, J., and Zeng, L. (2023). Relationship embedding, dynamic capabilities, and competitive advantages of cooperatives: an empirical study based on a sample of 286 cooperatives in Guangdong Province. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.). 2, 90–101. doi: 10.13300/j.cnki.hnwkxb.2023.02.009 (Chinese).

Wen, C., and Chen, B. (2019). Entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial strategy and the competitive advantage of new ventures. Foreign Econ. Manag. 41, 139–152. doi: 10.16538/j.cnki.fem.20190808.007 (Chinese).

Wieland, A., and Wallenburg, C. M. (2013). The influence of relational competencies on supply chain resilience: a relational view. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 43, 300–320. doi: 10.1108/IJPDLM-08-2012-0243

Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., and Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational response to adversity: fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manage. Ann. 11, 733–769. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0134

Wiwoho, G., Suroso, A., and Wulandari, S. J. M. S. L. (2020). Linking adaptive capability, product innovation and marketing performance: results from Indonesian SMEs. Manag. Sci. Lett. 10, 2379–2384. doi: 10.5267/J.MSL.2020.2.027

Wulandhari, N. B. I., Gölgeci, I., Mishra, N., Sivarajah, U., and Gupta, S. (2022). Exploring the role of social capital mechanisms in cooperative resilience. J. Bus. Res. 143, 375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.026

Xiao, X., Tian, Q., and Mao, H. (2020). How the interaction of big data analytics capabilities and digital platform capabilities affects service innovation: a dynamic capabilities view. IEEE Access 8, 18778–18796. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2968734

Yang, F., and Yang, M. M. (2022). Does cross-cultural experience matter for new venture performance? The moderating role of socio-cognitive traits. J. Bus. Res. 138, 38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.073

Yoshida, S. (2024). Impact of sustainability integrating environmental and social practices on farm resilience: a quantitative study of farmers facing the post-COVID-19 economic turbulence in Japan. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1341197. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1341197

Zhang, J., and Qi, L. (2021). Crisis preparedness of healthcare manufacturing firms during the COVID-19 outbreak: digitalization and servitization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:5456. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105456

Zhang, Y. Z., Mi, Y. S., and Liu, C. J. (2024). Farmer participation in cooperatives enhances productive services in village collectives: a subjective evaluation approach. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1442600. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1442600

Zhao, L., and Huang, H. (2025). The double-edged sword effects of leader perfectionism on employees’ job performance: the moderating role of self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 16:1412064. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1412064

Zheng, Y., Mei, L., and Chen, W. (2024). Does government policy matter in the digital transformation of farmers’ cooperatives?—a tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1398319. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1398319

Keywords: farmers’ cooperatives, organizational resilience, chairpersons’ self-efficacy, competitive advantage, environmental dynamism

Citation: Wang J, Wan J and Wu Z (2025) Seeking competitive advantage of farmers’ cooperatives through organizational resilience: examining the role of chairpersons’ self-efficacy and environmental dynamism. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1554308. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1554308

Edited by:

Vijay Singh Meena, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaReviewed by:

Azra Ahmić, International University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and HerzegovinaAdebanji Adejuwon William Ayeni, North-West University, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Wan and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junyi Wan, d2FuanlzY2F1QDE2My5jb20=

†ORCID: Junyi Wan, orcid.org/0000-0002-1661-7772

Jia Wang

Jia Wang Junyi Wan

Junyi Wan Zhidong Wu

Zhidong Wu