- Department of Anthropology, Archaeology, and Development Studies, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

The Johannesburg Fresh Prouce Market (JFPM) is the largest fresh produce market in Africa, in terms of volume and turnover. It plays a central role in making fresh produce accessible across Gauteng Province and surrounding areas. This article describes and analyses the operations of the JFPM giving attention to the social and economic forces that shape it and looking at its contribution within the food system. The research for this article was conducted from between 2019 and 2023, including extensive interviews with 127 research participants and observations conducted during over 60 visits to the Market. It is found that the JFPM involves a complex interaction between economic and social forces still influenced by apartheid era arrangements. This influence is evident in the long-term social relationships among actors of the same ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The findings also highlight the importance of the JFPM as a source of fresh produce, especially for low-income neighbourhoods through the multitudes of informal traders that source produce there. By making fresh produce more accessible and enabling the agency of diverse actors in the food system, the JFPM makes a key contribution to food security. The Market is also essential for farmers, large and smaller scale, who sell there. The positive role of the JFPM is under threat from a range of challenges ranging from internal issue such as decaying infrastructure to external factors, such as the increasing use of direct buying focused supply chains by supermarket groups. Given the important contributions of the JFPM it needs to be invested in and maintained. The lessons from this market have relevance to food markets in other contexts.

1 Introduction

South Africa has over the last years produced enough food to meet most of its needs and to supply lucrative export markets due to the high level of agricultural production (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2022; Simelane et al., 2024). Despite this, and the constitutional affirmation of a right to food,1 South Africa is far from food secure as many people, for much of the time, do not have access to sufficient safe and nutritious food. The country is afflicted with the triple burden of malnutrition (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2022) with 63.5% of the population suffering moderate to severe food insecurity, 28.8% of 5 years olds stunted by poor nutrition, and 67.9% of women and 38.2% of men overweight or obese (Simelane et al., 2024). There are also high levels of vitamin deficiencies in children and 30.5% of women are anaemic (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2022). Food accessibility, a key dimension of food security, is the biggest challenge as food is available but far too many people simply cannot afford healthy diets. One of the most important food groups required for healthy diets is fresh produce and markets play a key role in determining people’s access to this fresh produce (FAO, 2020).

The Johannesburg Fresh Produce Market (JFPM) is the largest fresh produce market in South Africa accounting for around 45% of the total value of sales across all the National Fresh Produce Markets (NFPMs) (Joburg Market, 2025; SAUFM, 2024). As the NFPMs account for 40–50% of sales of fresh produce from South African farmers (CCSA, 2025), the JFPM is estimated to handle 18–22.5% of all fruits and vegetables produced in the country. The JFPM also plays a central role in making fresh produce accessible across the Gauteng Province of South Africa and surrounding areas, particularly in low-income neighbourhoods through the multitudes of informal traders that source produce at the JFPM. These informal traders are creating livelihoods for themselves through this trade in fresh produce. The fresh produce sold at the JFPM includes the full range of fruits and vegetables from the large volume items such as potatoes, onions, tomatoes, and bananas through to lower volume items like table grapes and okra.

The importance of the JFPM is looked at in this article in the context of increasing concentration of ownership and control in the distribution and retailing of food in South Africa. This concentration is reducing the options and therefore undermining the negotiating power and agency of farmers, the many smaller-scale and informal retailers, and consumers (CCSA, 2019; Greenberg, 2017; Heijden and Vink, 2013). This threatens livelihoods and food accessibility for many people should the JFPM and other similar markets not be there and fully functional. In this context the JFPM and other NFPMs, in particular through being a source of stock for the informal sector and independent grocery stores, are playing a key role in ensuring wider competition and providing a counter force to the trend toward greater concentration.

As the JFPM is such a large and important market, it is surprising to find that there is limited literature available that explains and analyses how it operates. This limited available literature has required us in this article to provide an extensive description of how the JFPM functions in order to be able to answer the main research questions the study started with: (1) what are the social and economic forces that shape the functioning of the JFPM? And (2) how can the socio-economic and food security contribution of the JFPM be protected and enhanced? The purpose of this study and answering these questions is to contribute to our understanding of the functioning of such important food markets and through that to hopefully inform policies related to such markets.

This article is structured as follows: section two presents a brief literature review that situates this study in relation to key theories of relevance to markets; section 3 presents the means and methods used in the research for this article; section 4 presents the findings of the study from describing the operations of the Market and the actors involved through to exploring the interplay of social and economic forces, and showing the role of the Market in fresh produce supplies that are essential for food accessibility. Section 5 discusses the findings before section 6 ends the article with a summary of the main conclusions and recommendations.

The important contributions of this article are: (1) increasing our understanding of how food markets function by describing the current operations, history, successes and challenges of the JFPM; (2) showing the JFPM’s importance as a market for farmers and its contribution to food security through making fresh produce accessible and enabling agency, in particular through the large informal retail sector; and (3) critically assessing the socially embedded nature of the functioning of the Market which has advantages as seen in the resilience of the JFPM and disadvantages, notably the perpetuation of racial and ethnic divisions. The lessons from the study of this large and important food market have potential relevance to markets in other contexts.

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

2.1 Market theories

The narrowly economic view of markets sees them as places where rational economic agents compete, making decisions aimed at giving them the best material returns. Perfect market competition, it is argued, exists when there is: (1) economically rational decision making; (2) economic mobility, i.e., no transaction costs to enter the market; (3) perfect, continuous, costless intercommunication among participants; and (4) atomisation - every participant acting in their own interest (Stigler, 1957, p. 12). The economic agent is said to possess constant preferences that are void of emotions and not swayed by exogenous factors such as patronage, previous experiences, and social context (Ball and Mankiw, 2023).

The limitations of the orthodox economic analysis of markets have long been challenged by the likes of Granovetter (1985) who argue that economic relations are “embedded in social relations.” Other authors have developed these ideas and shown how economic actors are swayed by other factors such as religion and kinship (Block, 1990), framing effects, advertising, and “ethical consumerism” influenced by factors such as altruism, trust, and cooperation (Aldred, 2012). Callon (2007) described markets as “socio-technical arrangements or agencements” which involve multiple influences that are not mutually exclusive to one another. Fourcade (2007) identifies the importance in markets of social networks, the systems of social positions that organise markets, the institutionalisation process that stabilise them, and the performative techniques that bring them into existence. Despite such work, research on food markets has tended to overlook the implications of social forces on market operations (Schneider and Cassol, 2020).

Notable research that has brought to the fore the intersection of social and economic forces in fresh produce markets around the world include the study of the Porta Palazzo market in Turin, Italy, by Black (2012). She delves in to the life histories of market actor’s and explains how the physical environment has shaped the wider activities of the market. Another example is Viteri’s (2010) study of the Buenos Aires Central Wholesale Market in Argentina, which used ethnographic research to reveal the interlinkages between formal and informal social relations among actors and their influence on the market. Chikulo et al. (2020) and Hahlani (2023) both used actor orientated ethnography to examine the functioning of the Mbare Musika market in Harare, Zimbabwe and Wegerif (2018) used a similar approach to study a range of food markets in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The similarity across these works is seeing the importance of social relations, alongside narrower economic factors, in determining and facilitating transactions and thus shaping the operation of food markers. These studies all found market actors operating with common norms based on trust, interdependence, and reciprocity, underpinned by relationships of friendship or kinship, or at least familiarity. These authors tended to see the social relations as a positive factor that added value to people’s lives in markets and facilitated entry into markets. Hinrichs (2000), based on her studies of farmers’ markets in the United Kingdom has cautioned that while social embeddedness has an influence, prices matter, and there is still self-interest at work.

Below we turn from this international perspective to some food market studies from South Africa.

2.2 Fresh produce market studies in South Africa

As mentioned, we have been surprised at how little literature we could find on the fresh produce market system in South Africa. Most of the papers have applied an economics perspective. For instance, Ngiba et al. (2009) and Madevu et al. (2006) provided analyses of the level of competitiveness within South African fresh produce markets using “Porter’s 5-Forces” competition model to look at the Natalspruit and Tshwane markets. Other studies have touched on the fresh produce markets, including the JFPM, while focusing on particular elements of the value chain, such as the competitiveness of the stone fruit supply chain (Boonzaaier, 2015). Other studies making tangential mentions of the JFPM include an exploration of urban agriculture as a business venture (Ratshitanga, 2017), market access through the JFPM for black commercial farmers (Simelane, 2015), and urban agriculture (Malan, 2015). On the other hand, there have been studies that touched on the municipal markets while focussing on the supply side (Henning et al., 2019; Paterson et al., 2007; Strauss et al., 2008; Zuma-Netshiukhwi et al., 2016). The book chapter Tempia et al. (2023) gives a useful overview of the JFPM and municipal markets in South Africa. That chapter is based in part on research done by the authors of this article that goes into greater depth in explaining the JFPM and how it is organized.

Other studies, by academic researchers and the Competition Commission South Africa (CCSA), have looked at the high levels of concentration in markets and the negative implications of that for farmers and consumers. The problems highlighted in this literature include the increasingly limited market choices that farmers and consumers have, which limits their negotiating power. As supermarkets increasingly buy through their own supply chains, many farmers struggle to meet the quantity and standard requirements demanded and those who do get incorporated into these supply chains often find they have little power to negotiate good terms of trade. A result is the downward pressure large supermarket groups exert on farm prices, which are not passed on to consumers (CCSA, 2019; CCSA, 2021; CCSA, 2025; Chikazunga et al., 2008; Greenberg, 2017; Heijden and Vink, 2013; Wegerif, 2024). It is in this context that the CCSA (2025, p. 248) concluded that “[s]elling to independent retailers through the NFPMs is therefore an important alternative route to market for farmers.”

Central to our interest in studies of markets is how markets contribute to food and nutrition security. We, therefore, make clear in the section below the definitions and dimensions of food security.

2.3 Food security

We follow the widely agreed definition of food and nutrition security2 which is “[a] situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2023, p. 246).

We further understand the achievement of food security to depend on six main dimensions that have in the last years become a widely accepted extension of the previously used four dimensions of food security. The six dimensions are: (1) “Availability” of sufficient food through production or importation generally at a national level; (2) “Access” to food for all people, normally through their ability to purchase it, unless they have the means to produce it; (3) “Utilization” which relates to ability to ultimately achieve nutritional wellbeing which depends on being healthy, hence the link to water and sanitation, and the ways food is prepared and cooked; (4) “Stability” of the achievement of food security in the face of short-term shocks that could disrupt it; (5) “Agency” that involves people’s ability to make decisions and take actions to improve their situations, in this case their food security status; and (6) “Sustainability” over the long-term, including for future generations in the face of threats such as from climate change (HLPE, 2020).

Food security is achieved within food systems that encompass the core functions of production and distribution through to consumption, but also take into account the wider social, political, economic, and ecological factors that shape the food system and are also impacted by it (HLPE, 2020; FAO, 2018). Markets are key nodes within food systems playing a major role in the distribution of food with their functioning affected by the policy as well as economic environment and the nature of their functioning have a substantial influence on food being accessible in terms of factors such as price and proximity to customers.

As mentioned in the introduction, with food being available in South Africa yet many people food insecure, the main food security challenge is in achieving access to sufficient healthy food for all, especially for those in poverty (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2022; Simelane et al., 2024; Rudolph et al., 2021). Our focus in this article is on the role of the JFPM and other such markets in contributing to the food accessibility dimension of food security. Further, we give attention to the role of the JFPM in enabling agency due to the contribution we found it making in this dimension.

Having looked at existing work on markets and food security, the next section elaborates the methodology used in the study that informs this article.

3 Means and methods

Building on other market studies (Black, 2012; Chikulo et al., 2020; Malan, 2015; Viteri, 2010; Callon, 2007; Wegerif, 2018) we took an actor orientated approach, relying on extensive interviews, observations, netnography (Kozinets, 2015), and a review of existing reports and publications on the Market. This was inductive and exploratory research that started without strong prior assumptions and instead drew for analysis on the empirical findings, which we then related to arguments in existing literature (O’Leary, 2017).

3.1 Sampling and participants

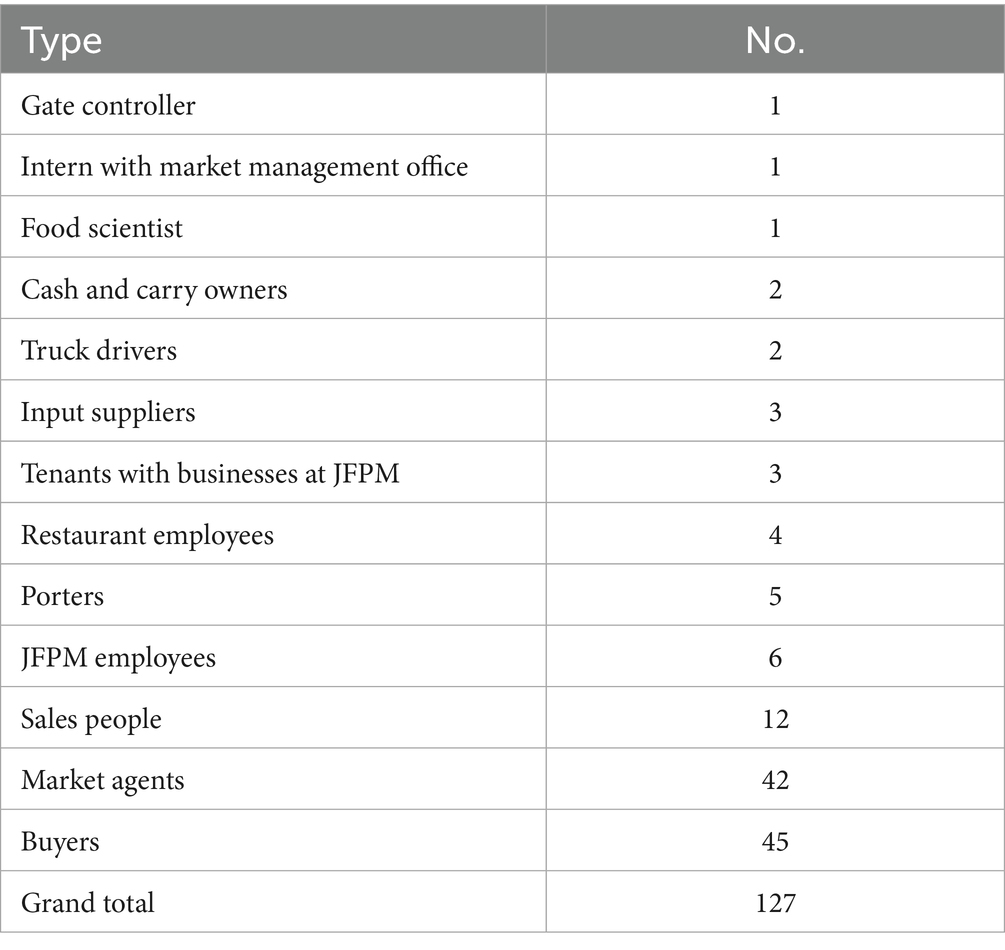

The primary research was carried out from 2019 to 2022 and involved over 60 visits to the JFPM and in-depth interviews with 127 research participants at or linked to the Market (Table 1). Research respondents were selected using purposive sampling targeting a diversity of actors from JFPM (Vehovar et al., 2016). We involved actors from across the three main trading hubs and the smaller Unity and Mandela markets and covering different roles at the market in order to understand all parts of the operation (Table 1). The largest number of the research participants are buyers and the agents and salespeople. This is because they are the main and most numerous actors and at the heart of the Market’s main business of buying and selling fresh produce. This also makes them central to key market functions such as price formation. It was also necessary to have a large number of buyers and sellers (including the agents) in order to cover their diversity in terms of factors like the different parts of the Market they operate in, the different produce they trade in, and their different scales and types of operations.

The total number of research participants was determined by the concept of “saturation” which was reached when further interviews added little new information of any value to our understanding and the emerging analysis (Tracy, 2013). For example, one thorough interview with a gate controller, combined with observation of gate controllers at work and descriptions of their roles from other actors, such as agents who employ them, provided a very good understanding of their role. This made further interviews with gate controllers unnecessary. On the other hand, the diversity of types and experiences of buyers necessitated far more interviews to get a full picture of buyers’ activities, experiences and views.

Potential research participants were approached directly in the Market and by snowball sampling, involving referrals by existing research participants (Etikan et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2019). A limitation was that we did not interview farmers, despite their importance to the Market, as they are rarely in the Market themselves.

3.2 Data collection

The interviews conducted were semi-structured using an interview guide with some set questions on issues such as what influenced people’s buying and selling decisions and then more open-ended discussions on the functioning of the Market and people’s histories and roles at the Market. Most interviews were conducted at the Market, often as the research participants went about their daily tasks, the questions and answers interspersed with dealing with customers and other tasks. More rarely it was possible to find a quiet space to have the discussion when the research participant was less busy. Follow up interviews were made to many of the research participants over the years of the study. During COVID-19 related lockdown measures some interviews were conducted online through mediums such as WhatsApp video and audio calls. Interviews were conducted in English, Xitsonga, sporadic Zulu, and with a few Portuguese words. The use of Xitsonga facilitated the building of rapport as it is one of the most used languages in the Market and the home language of the first author.

Observations were carried out during visits to the Market throughout the research period, which covered all seasons. Observation was found to be particularly useful in understanding the functioning of the Market and related social and economic activities in the space. We could in real time observe, amongst other things, the state of the infrastructure, the movement of stock into, around and out of the market, seeing the process, the different forms of transport used, and roles played by different actors. Being able to observe people at work helped to better understand what they did and how including how different actors relate to each other, for example how buyers check the quality of stock and negotiate with agents. Such observation also provided useful avenues for further exploration in interviews where clarity could be obtained on what had been observed. Some visits involved most of the day, starting from before 4 am.

3.3 Data analysis

Data analysis was done manually by the authors only using Microsoft Word and Excel. The first part of data analysis drew out information from interviews, assessment of reports and existing articles that mention the JFPMs, and information from observations to be able to describe the Market. This description of the JFPM and its actors and operations is essential to understanding the findings and to inform the analysis, especially as the we could not find existing clear descriptions of the JFPM and its functioning.

The set questions were analysed more quantitatively to identify the dominant views across research participants on these issues, such as the main factors informing buying decisions. Data analysis on the more open-ended questions was carried out using a thematic analysis, looking for common and differing responses and emerging themes and phenomena from the interviews and observations. In places we use brief vignettes of particular market actor’s roles and experiences where these exemplify the wider experiences found. These vignettes aim to bring out the real-life experiences of actors and give the reader a feel for the functioning of the JFMP. The emerging themes from the primary research were analysed in relation to key literature to come to conclusions.

Quantification of the impact of the JFPM on food security was beyond the scope of this article, but the importance of its contribution emerged from the findings on the scale and nature of the JFPM operations. When these findings were combined with the dimensions of food security and the concept of the food system, it became clear that the JFPM, as a key node within the food system, makes a key contribution to food security.

3.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the research was obtained from the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee. The JFPM management gave consent for the study, all interviewees gave their informed consent, and explicit permission was given for the researchers to join WhatsApp groups that they participated in. The identity of respondents is protected by using pseudonyms and care was taken to not reveal sensitive information that could be attributed to particular individuals. During the COVID-19 pandemic, safety protocols were followed, such as wearing masks, regular hand sanitizing and attempting to keep a physical distance from research participants. This was not always easy in the crowded Market and when people were tired of following the COVID-19 restrictions.

4 Findings in relation to Johannesburg fresh produce market

Section 4 provides the findings of primary and secondary data collected. It begins contextualising the current state of the Market, paying special attention to its origins, governance and managements structures and how transactions are conducted. This is followed by an exploration of the social and economic forces that shape the Market, its functioning and its successes and challenges.

4.1 Johannesburg fresh produce market today, origins, governance, transactions

4.1.1 Origins of the Johannesburg fresh produce market

The discovery of gold in what is now the Gauteng Province of South Africa in 1886 (Phillips, 2013), led to the creation of the city of Johannesburg and the city needed food. In response an open-air market at Market Square in the centre of the rapidly growing city opened on 1 February 1887. There were fresh produce stalls on the east side of the square selling fresh fruits and vegetables, milk, eggs, butter, mealies, maize, and other food products (Cripps, 2012; Davie, 2018).

Market Square received goods from all regions of the country and farmers of all races. The farmer would bring his produce to the market and sell it to a middleman (broker or wholesale merchant) who sold this produce to buyers like Indian and African hawkers, shopkeepers, mining companies, and housewives (Evans et al., 2018; Cripps, 2012). The Market grew in size and a market building was constructed. In 1889 the commission on all sales inside the market building that went to the market was halved from 10 to 5%.

The Market was relocated in 1913 to a larger site and a new market hall in Newtown where it had direct access to the railway line (Davie, 2018). In 1963, the government introduced selling through market agents as the sole mode of transaction at municipal markets. Agents sold on behalf of the farmer, negotiating with the buyers, and received a commission on the sales made. The maximum commission allowed was set to prevent the excessive exploitation of farmers. This agent and commission system remains in place today.

The Newtown Market established itself as the food retail and wholesale hub for the Union of South Africa and its neighbouring countries with sales of around 2,000 tons and 350 railway trucks delivering goods every day in the 1960s (Day, 1968, p. 11). The Johannesburg Market accounted for a third of the turnover of South Africa’s 102 municipal markets at that time (Bester, 1966).

In 1974 the Market moved to its current 63-hectare site in City Deep, Southeast of the Johannesburg city centre. It continued with the system of sales going through agents in the main hubs. All these registered agents were white, mainly of English, Portuguese, and Afrikaans descent and they tended to have close working relationships, both informal and more formalised in cooperatives, with farmers of the same ethnic origins.

Meanwhile, the sellers of Indian descent operated from smaller halls located between the vegetable and fruit hub (now known as Unity Market). The Indian traders purchased their stock from the main hubs and were called platform traders and paid a fixed rent to the Market.3 Unfortunately, the contribution of black sellers to the Market at that time is unknown, however, interviews indicate that black people were employed by market agencies and bought produce in bulk from the JFPM.

4.1.2 Physical structure of JFPM

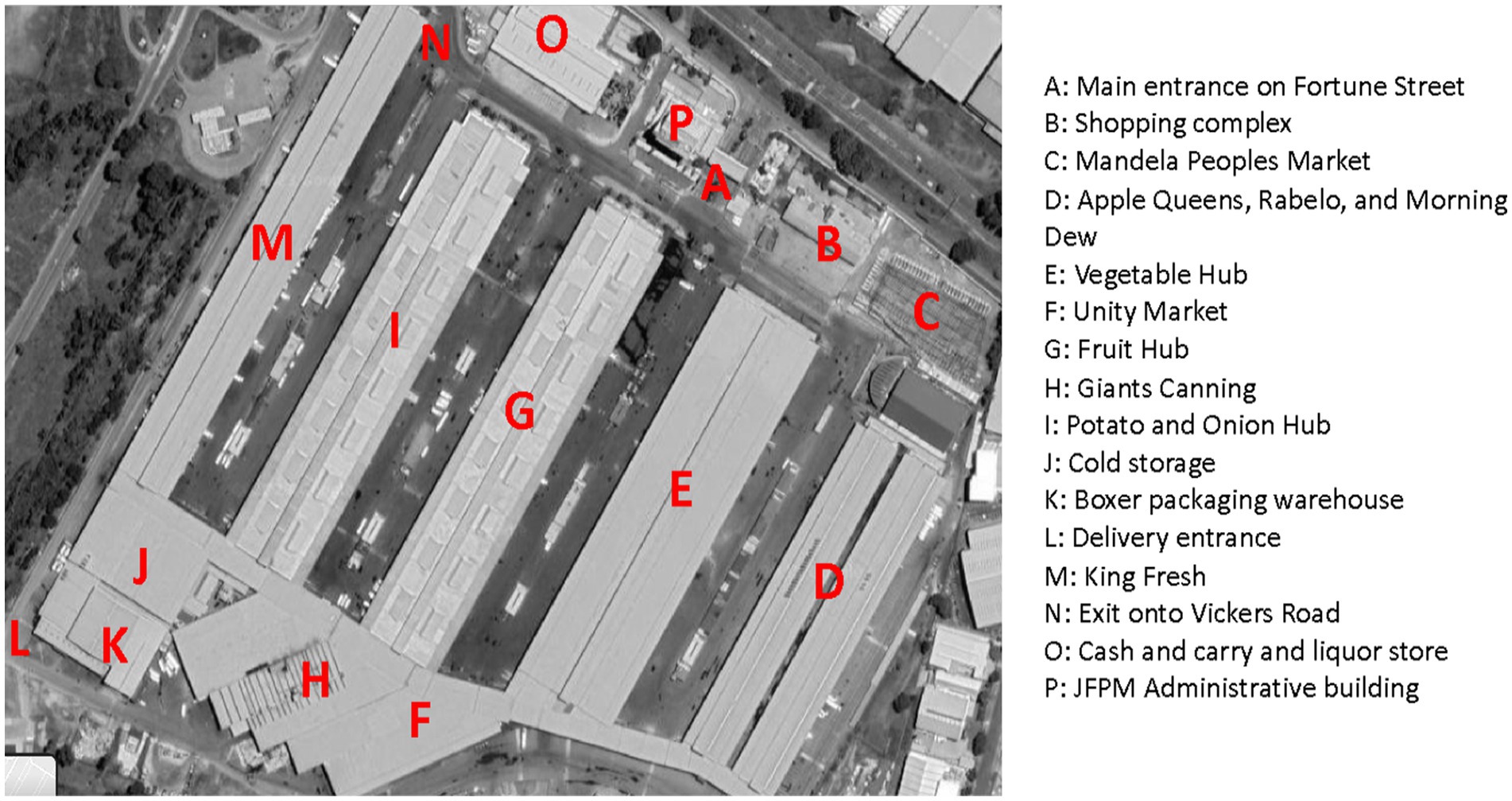

The core of the JFPM consists of five long halls (M, I, G, E, D in Figure 1) each surrounded by full length platforms that allow for the loading and unloading of items. Pedestrians, porters, forklift drivers, and vendors selling tea and snacks all use these platforms. Tarred roads and parking areas separate the halls. The middle three halls each house one of the main trading hubs: Vegetable hub; Fruit hub; and the Potato and Onion hub. The furthest West hall (M) contains a range of wholesalers, the largest being King Fresh. The supermarket chain, Boxer, has a warehouse and packaging facility at the JFPM which is also managed by King Fresh. The furthest East hall (D) houses offices, such as for the agents and market agencies, and other business including some wholesalers.

Figure 1. Aerial shot of JFPM, 2021. Source: Google Maps (n.d.). Joburg Market, 4 Fortune Road, City Deep Johannesburg. https://maps.app.goo.gl/FmZrYxjMT2dekmxL8 with additional information by researcher.

Structures housing the banana ripening and cold storage rooms are along the southern end of the main halls. There are 55 cold rooms owned by the JFPM with the capacity to hold 4,561 pallets of produce. These cold storage rooms are rented out per pallet to the agents who store produce there to keep it fresh for longer. Some agents also have their own cold rooms situated in their trading areas.

Unity market (F) is situated between the vegetable and the fruit hubs with storage units rented by traders. Selling is done from these storage rooms and across the platform with produce set out on pallets or stacked in crates or sacks. The Mandela Market, recently renamed the Tshiamo Market after the construction of a new building, is in the far East corner of the site (C). The traders in the Mandela and Unity markets purchase produce in bulk from the main hubs and then break bulk to sell smaller quantities for cash. Their customers include buyers who do not have the account and card needed to buy in the main hubs and also many who could buy in the main hubs but find good deals on smaller quantities at the Unity or Mandela markets.

Within each main hub, trading spaces are allocated to particular agents within a larger space allocated to the agency they are part of. The amount of space given to each agent and agency is based on their proportion of the total sales in that hub in the previous year. These spaces are demarcated using steel fences on concrete blocks and signage for each agency. These sales areas fill the space between a central alleyway – just wide enough for the forklifts and buyers who walk there - and the outer walls of the hall. Each sales area has an entrance/exit both onto the central alleyway and directly onto the platforms running the length of the building on each side.

During the busiest hours the alleyways in the hubs, entrance/exits, and the platforms alongside the halls teem with people and forklift trucks creating a buzz of activity. The forklift drivers account for the loudest sounds hooting and yelling at people to get out of the way as they speed to pick up or deliver pallets of produce. Each sales area has some form of desk, or a few desks, where the administrative staff, employed by the agents, record transactions on the computer system. Many agents have raised desks they work from, staying on their feet or perched on stools throughout the morning as they interact with the many customers.

The sales floors also serve as storage areas for produce that is brought in on pallets. Stacks of crates and piles of sacks fill most of the trading space of successful agents, while some produce is stored in cold rooms.

Trucks bringing produce into the Market enter in the far East corner (L) where consignment officers check delivery notes and record what is coming in and inspectors check the goods inside the vehicles. The trucks carrying stock bought at the Market exit from the North-West corner (N) where they are also checked. Hundreds of vehicles arrive everyday: the bigger vehicles (such as the semi-trailer trucks that can carry loads of 30 tons and more) are common at night and early in the morning when the main deliveries are made. Many smaller vehicles (such as bakkies4 and cars) are more prevalent leaving with stock bought at the market in the daytime (Figure 2).

4.1.3 Management and governance

Currently, there are 16 municipal National Fresh Produce Markets (NFPMs) in South Africa registered under the South African Union of Food Markets. They operate under one of four models: (1) owned and managed directly as part of municipalities; (2) land and infrastructure owned by the municipality and the operation corporatised with semi-independent status, but owned by the municipality; (3) land and infrastructure owned by the municipality and rented out to a private business operation that runs the market; and (4) privately owned and managed markets (Tempia et al., 2023, p. 123). It is noteworthy that the number of fresh produce markets registered with SAUFM declined from 19 markets in 2018 to 16 by the end of 2024. The JFPM operates under the corporatised model listed second above. It is entirely owned by the City of Johannesburg (CoJ) Municipality, it is regulated by the Company Act of South Africa, 2008 (Act no. 71 of 2008), the Local Government: Municipal System, 2000 (Act no. 32 of 200), and the Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 (Act 56 of 2003). Furthermore, the JFPM is governed by a Service Delivery Agreement (SDA) between it and the CoJ.

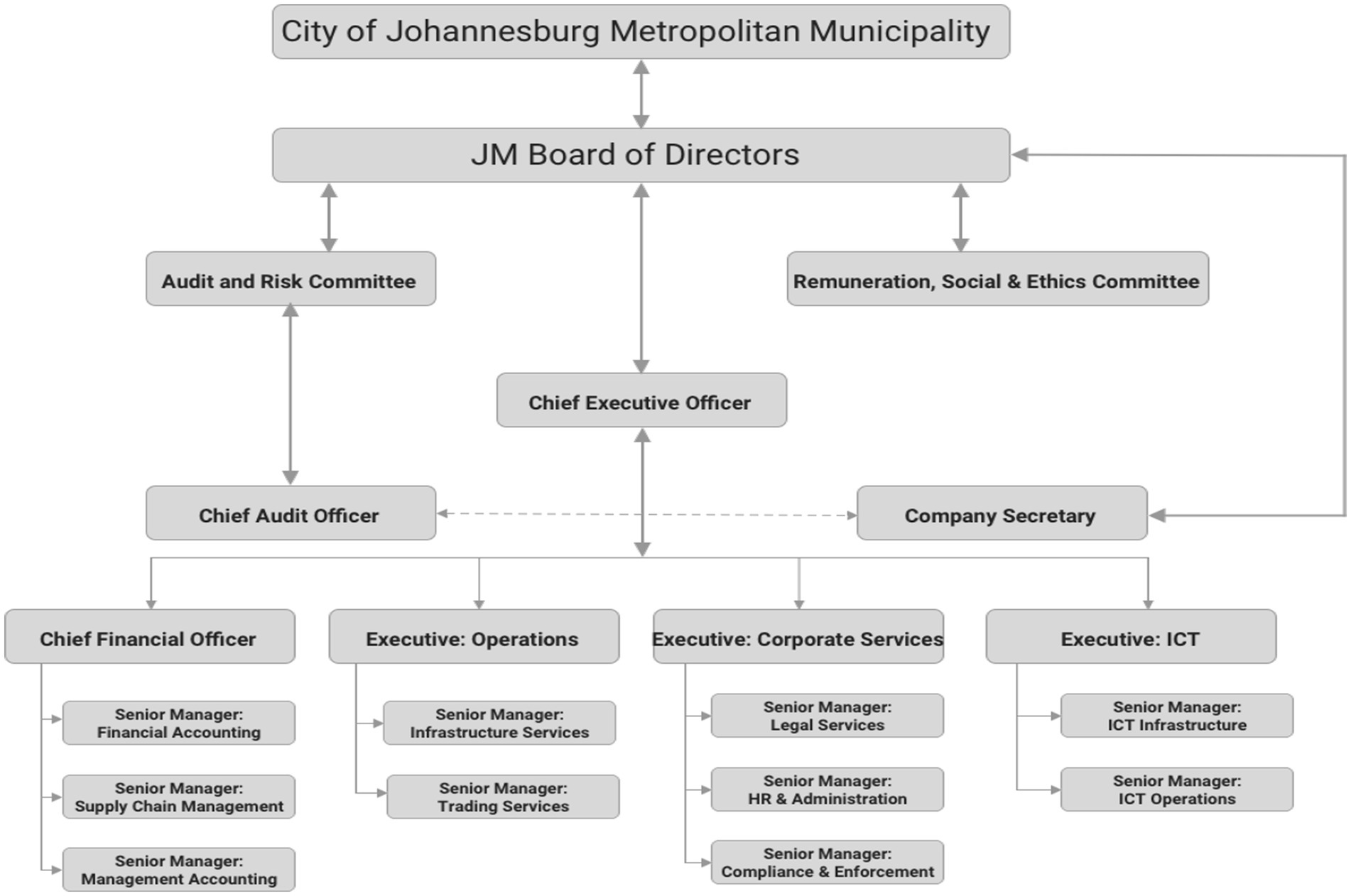

The JFPM has a Board of Directors (BoD) appointed by an independent oversight committee of the CoJ and paid under the CoJ Group Remuneration Policy. The BoD appoint the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the JFPM and report to the CoJ. The CEO is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the JFPM and is assisted by a range of other executives, committees (Figure 3) and 313 employees.

Notwithstanding a semi-independent board, the JFPM has undergone multiple management changes over the past 5 years due to political changes and instability at the municipal level. As the balance of power in the CoJ has shifted with elections and changing coalitions, the leadership of the JFPM has been changed to reflect the new leadership or as part of coalition negotiations and horse-trading.

4.1.4 Transactions at the JFPM

In the year 2024, total fresh produce sales at the JFPM over the 12 months came to 1.37 million tons tonnes with a total value of R11,298.6 million5 (Approx USD 610.7 million) providing a commission income of R564.9 million (USD 30.5 million) to the JFPM. Other income was derived from rent and payments for value-added services, such as use of the cold rooms. We were not able to secure the full financial reports of the JFPM for this period, but according to the budgets of the CoJ for the 2023/24 financial year (CoJ, 2023) the total direct revenue at the JFPM was projected to be R646 million (USD 34.9 million) with a direct expenditure of R519 million (USD 28 million) leaving an anticipated surplus, after taxes and other indirect transfers, of just under R107 million (USD 5.8 million).

The conduct of the all-important market agents is regulated by the Agricultural Produce Agents Council (APAC) under the Agricultural Produce Agent Act (Agents Act), 1992 (Act 12 of 1992) as amended by the Agricultural Produce Agents Amendment Act, 2003 (Act 47 of 2003). APAC is accountable to the Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, and comprises an Executive Committee (EXCO) and sub-committees which cover areas such as transformation, audit and remuneration, and the various agent types (livestock, export, and fresh produce).

All individual market agents trading at the JFPM operate under a fresh produce market agency and are registered with APAC. The market agent registration process includes completing an application form, achieving a minimum 75% pass rate in an online training course and paying R52,441.12 (USD 2,835). In 2022 this amount was made up of a fee of R1,761.92 for the issuing of a certificate, a vetting and crediting fee of R679.20 and a once-off contribution to the APAC fidelity fund of R50 000. Thereafter, the market agent pays R12128.03 per year to APAC. Moreover, the market agency needs to be issued a licence to operate on the trading floor by the Market Master (CEO). There are 17 market agencies operating from the JFPM, all with individual agents linked to them. Each agent in turn employs salespeople, administrative staff, and general labourers who assist with packing the produce in their trading areas.

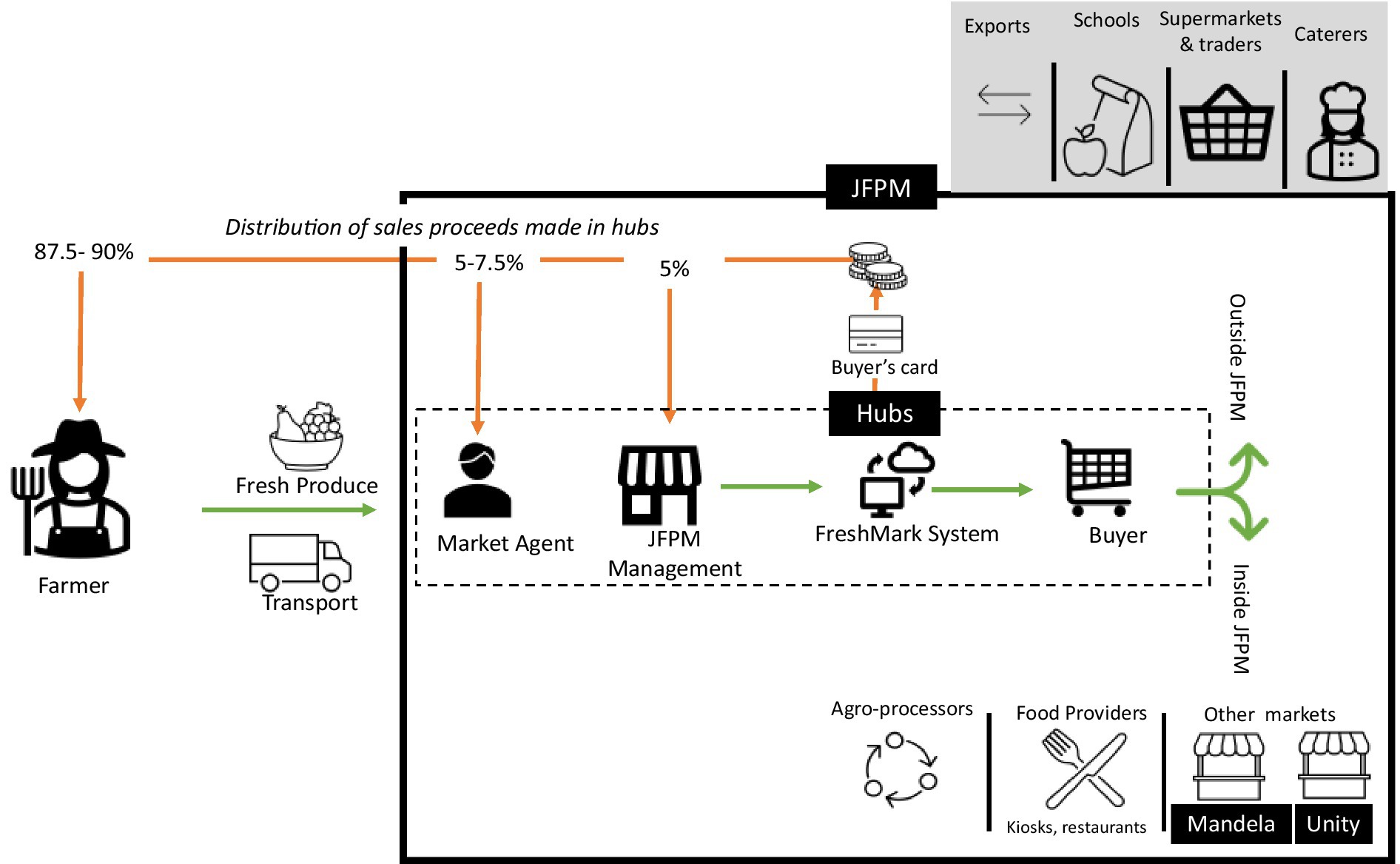

All produce coming into the JFPM must be received by a specific registered agent and all sales in the main market hubs are facilitated by one of these agents (Figure 4). Buyers in the main hubs must be listed as buyers and open an account with the Market. They buy using a card with the payments deducted from their account and no cash payment, for produce, is accepted in the main hubs. A valid identity document, including passports from any country, is required to register and open such an account at one of the Customer Care Centres (CCC) situated in the main trading hubs. The buyers load cash on their accounts at the same CCCs.

The produce sold at the JFPM is sourced from across the country and outside South Africa (e.g., Mozambique), with the bulk of it coming from Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces. A farmer (seller) can approach a market agent, or the market agent can approach the farmer. This is done telephonically or in person with visits to the farms by agents or to the Market by farmers, although this is rare. It is more common for Agents to visit the larger, still normally white owned, farms. Small-scale and black farmers can and do supply the JFPM and other NFPMs, although many feel they do not get a good deal (Ratshitanga, 2017; Simelane, 2015; Wegerif, 2022).

The computerised FreshMark System (FMS) tracks the arrival of the stock in the Market through to its sale. The system distributes the proceeds of sales with between 5 and 7.5% to the agent, 5% to the JFPM, and the balance to the farmer who normally gets 87.5% of the sale price. The agents can negotiate with the farmer within the set range with the larger farmers inevitably being in a better position to get the lower 5% commission rate. The agents commission goes to the agency from where it is split according to internal agreements between that agency and the agent that made the sale. The agents cover all their operating costs, including staff costs, and get their income from the commission they get. The produce sold is deducted from the available stock recorded on the system and physically moved from the main sales floor to the buyer who arranges transport to take their goods away.

Despite the same formal arrangements for transactions and allocations of floor space existing across the three main hubs, each has developed its own character based on established, but not codified, norms. For instance, the communication of prices is different in each hub. The Potato and Onion Hub uses small signs with prices next to samples of the produce set out in display areas, while the Fruit Hub displays average prices on a blackboard at the back of the hall, and the Vegetable Hub displays no prices, at all, with agents verbally communicating prices directly to potential buyers.

Some of the produce in the main hubs is bought by platform traders who sell it on at the Unity and Mandela Markets. Platform traders are registered with the JFPM and pay a fixed monthly rental for the space they use. Some of these registered traders sub-lease their stalls to others through verbal agreements. The platform traders break the bulk amounts to sell in smaller units. For example, buying a whole pallet of potatoes, typically 1,500 kg, and then selling per 10 kg or 5 kg sack. Those who buy at the Unity and Mandela markets include many small traders who buy stock for their businesses. The agents in the main hubs, can also break up the pallets, but often do not like the inconvenience of doing so as they need to move large volumes with minimum transaction costs. Therefore, even if the agent is willing to break up the pallet, they will tend to sell the whole pallet at lower per unit prices. This leaves an opportunity for the traders in the Unity and Mandela markets, who with their smaller-scale operations and cash business, can manage the transaction costs of selling to a larger number of small buyers.

Other produce bought in the main hubs is taken to distribution centres based within the JFPM site, such as for Boxer supermarkets and King Fresh. These companies then divide up the bulk purchases for delivery to their various outlets or clients.

Other produce sold in the main hubs is transported straight out of the JFPM by the range of buyers, the largest group of whom are the multitudes of informal sector retailers, such as street traders.

4.2 Actors at the market

There are a wide range of different actors who derive their livelihoods at the JFPM and spend time there. On any day, the JFPM is full of thousands of different people from all walks of life who come there to perform a variety of functions, and who collectively make up the JFPM. Some people are more essential to the core functioning of the Market and are referred to as market makers (Viteri, 2010). Without these people, the JFPM would cease to exist. Market makers include prominent actors such as the JFPM management staff, market agents, traders in the Mandela and Unity Markets, and buyers. For the sake of brevity, we have focused below only on the main market makers.

4.3 Market agents and salespersons

There are 17 market agencies operating at the JFPM but with just four of these agencies handling over 80% of sales. There are also some investors with stakes in more than one agency, raising concerns about the level of competition within the JFPM (CCSA, 2025). Operating under the various agencies are hundreds of market agents, who run their own operations, competing even within the same agencies, as they depend on the commission from sales for their profits. We could not find reliable figures for the numbers of agents at the JFPM, but based on the national figures for registered fresh produce markets agents (APAC, 2022), and given the share of the national market held by JFPM, we estimate over 400 agents at the JFPM of which about 78% are white and 93% men.

Most market agencies are owned by families of English, Portuguese and Afrikaans descent that have been operational in the Market for decades. Licensed market agents are mainly white men, some who are second and third-generation market agents in their families. For example, Rodrigo immigrated to South Africa from Portugal in 1977 as a child. Rodrigo’s father came to join his uncle in operating a market agency based at the JFPM. Over time, Rodrigo’s father started his own fresh produce selling business. After school, Rodrigo and his brother would help run the family business working as salespeople until they grew up and registered as agents themselves. In 2021, Rodrigo continued to operate as a market agent at the JFPM with his own sons also at that point registered as market agents and running their own operations, all under the same market agency. The family trio collaborate sharing equipment such as forklifts, cold storage, and jack lifts as well as vital information that can help in determining their selling decisions.

The type of arrangement Rodrigo and his sons have is typical at the JFPM. Market agents that operate under the same market agency often either share the same background and ethnicity and come from the same areas or even the same families. Such relations extend to the farmers agents represent at the Market as Portuguese agents are more likely to sell produce from farmers of Portuguese descent, and Afrikaner market agents are more likely to sell produce from fellow Afrikaners and so forth. These social connections are maintained and reinforced through practices such as the daily conversations between agents and farmers, which go beyond discussing Market information to include social issues, and social occasions such as braais6 on farms that agents attend. These arrangements have led to a level of specialization in ethnically based produce clusters at the JFPM with Portuguese market agencies mainly specializing in vegetables and some fruit, English market agencies dominating fruit sales, and Afrikaner market agencies focusing on potatoes, onions, and tomatoes.

The majority of black people and women selling produce at the JFPM are salespersons and are not registered with APAC, however, a handful of black licensed market agents and licenced women agents can be found at the JFPM, like Dineo – a black woman market agent. She came to the Market as an intern working for the JFPM in 2010 and was promoted within a year and worked for the JFPM for 6 years before becoming a market agent in 2016. Dineo currently employs five people and sources produce from farmers in the Western Cape, Gauteng, and Limpopo provinces.

Salespersons perform the same functions as market agents, but they are paid a salary by the agent rather than being entitled to the sales commission. Mufaro, one of a few black salespersons, first came to the Market when a friend helped him find a job as a gate controller. Mufaro learnt the business and rose through the ranks of an agency until he became a salesperson in 2022. We share some detail of a typical day for Mufaro to illustrate the work of salespersons and agents and how prices are set.

Mufaro starts at 3 am with checking the stock with the night shift manager. He oversees the arranging of stock on the sales floor with three packers and two forklift drivers. Mufaro then joins a team meeting, including the market agency’s owners, where they discuss the produce prices. The factors considered are the prices asked by farmers, the previous day’s closing prices, the day of the week and time of the year, the prices of competitors, and the weather. According to Mufaro the biggest influence is supply and demand, as he put it: “when there is too much stock on the floor, the price goes down; when there is too little stock, prices are high.”

After the meeting Mufaro has a sandwich and coffee for breakfast while responding to WhatsApp audio calls, texts, and voice notes from customers, and perusing prices on his two smartphones. He is typically engaged in around 10 negotiations at a time. The first prices are agreed with customers in this period before the Market officially opens at 5 am. Minutes after the Market opens Mufaro processes the sale of 15 pallets of carrots (approximately 19.5 tons) to a Mozambican buyer who is a regular customer. His next sale is a more modest 26 kg pocket of cabbages to an informal trader from the Johannesburg CBD. Notwithstanding the supply and demand factors, prices are not the same for all buyers. Mufaro explains that:

“…not all customers are equal. There are those you know and those you do not know. This is what determines the price on any given day. If the market is high, then you give good prices to everyone. Still, if the market is low, you give out fewer discounts which are just for my loyal customers—people you know. You see, there are big buyers, small buyers, time wasters, and potential customers. But most of all, there are those you trust – people who become your friends because you deal with them on a daily basis. These people get the best negotiation prices because you know them well and have gained some understanding.”

While selling on the sales floor, Mufaro continues to strike deals by phone and on WhatsApp. While selling, Mufaro also has social conversations with clients about things from family to soccer and music. He is always on his feet moving around the sales floor showing customers the produce, discussing prices, and making sales often while standing next to the relevant pallets, crates, or sacks. The agreed sales and prices are given - hand-written on scraps of paper or shouted across the sales floor - to the administrative staff employed by the agent who enter it on the computer at their desk in the middle of the sales floor. The selling persists at a high tempo for the first 2 h and then dwindles until it halts at 11 am.

Mufaro then takes a short break, grabbing an energy drink and snack from the nearby restaurant, where he chats with other salespersons and market agents about the performance of the market and exciting stories from the morning’s activities.

After the break Mufaro oversees 10 workers who clean the sales floor and cold room and rearrange stock, stacking pallets using a forklift and manual labour. Mufaro checks the quantity and quality of produce left on the sales floor and cross-references this with the information on the computer to identify any theft or other losses. He also checks new produce arriving by truck during the day. Mufaro ends his workday at 3 pm and goes home to his wife and two children.

4.4 Platform traders

Platform traders7 buy produce from the main hubs and sell for cash at the Unity and Mandela markets accounting for a considerable share of sales in the main hubs. While there are a few South African platform traders, the majority come from other African countries, mainly from Southern and Western Africa. An example is Chinedu who specialises in selling peppers at Unity Market. Chinedu is second in charge to the “big boss” in a business with his “brothers” who are not blood kin but are all Igbo from Nigeria.

Chinedu’s starts at about 3:30 am unpacking produce from a small storage hall. Occasionally, especially in summer, some produce is in cold storage facilities. The produce is arranged and sold just in front of the small hall under the control of the “big boss” and on the open platform where Chinedu is in charge and oversees five other workers. Upon arrival, Chinedu double-checks the quantity and quality of produce then arranges it in a U-shape, which he stands in the middle of to safeguard the money in a fanny pack at his waist. According to Chinedu “the Market is very busy, and sometimes you can lose a lot of money. So, it is good to protect the money.”

Buyers surround the stall asking for prices as early as 4 am but generally do not buy until the Market’s official opening at 5 am as they first compare prices in the main hubs. Traders at Unity Market set prices based on a minimum mark up on what they paid, as Chinedu explains:

“…we divide a specific produce’s total value by the number of available boxes. Then we put a markup of R5 [per box]. It is always plus R5 for everything because there is too much competition. You can see for yourself – my neighbour also sells peppers.”

Although the sales margins are small, the profits add up as Chinedu can handle a turnover upwards of R100,000 (USD 5,400) on a good day. Chinedu collects all the money, while his co-workers are responsible for garnering sales and moving the produce around. Sales and the exchange of money happen at a rapid pace. Notwithstanding the pace, Chinedu is familiar with many buyers sharing jokes and stories and having nicknames for each other.

Once sales have stopped, Chinedu gathers all the money and counts it with the “big boss” in the small hall before depositing it at the bank. Meanwhile Chinedu’s co-workers pack the remaining stock in the small hall and count and reconcile it with the day’s proceeds.

Chinedu also buys stock for the business. He has close relationships with the agents selling peppers, which enables him to place orders on trust and collect later when trading has closed. Chinedu also has brands he trusts and always buys unless the market is low. Then he shops around, sometimes also sending a co-worker to look for lower prices. After selling and restocking, Chinedu goes home at about noon.

4.4.1 Buyers

Over 10,000 buyers transact at the JFPM every day just from the main hubs. These diverse buyers that the market caters for include supermarkets, wholesalers, exporters, independent grocery stores, hotels, restaurants, catering companies, food-processors, institutional buyers, school feeding programme suppliers, and individuals buying for their own household consumption.

The most prevalent cross-border traders at the JFPM are the “Maputo Mamas” from Mozambique, identifiable by the traditional fabric they wear, who supply fresh produce markets, such as Zimpeta in Maputo. Some of these women live in South Africa, while others travel from Mozambique at least twice a week. Benedict is another cross-border trader we interviewed. He had arrived in South Africa 3 days before with four semi-trailer trucks and spent close to R1 million on citrus, shallot onions, and potatoes. His cheap cell phone, worn trousers, and flip-flops did not reflect the importance of his supplies to the Soweto public market and supermarkets in Zambia.

Ntsetselelo is an example of an informal wholesaler who sells mostly to informal traders in the large township of Tembisa about 40kms from the JFPM. She spends a minimum of R50,000 per day stocking produce such as tomatoes, onions, carrots, peppers, butternut, beetroot, potatoes, and cabbages. Ntsetselelo concludes purchases in the morning and arranges transportation of the stock in the afternoon.

Despite the increased use of direct supply chain arrangements with farmers, large supermarket groups continue to buy at the JFPM, including using the JFPM as a market of last resort when they have supply chain problems (CCSA, 2025). The supermarkets normally send unidentified buyers to surreptitiously check prices and then go in groups in company branded clothes to argue with the agents for lower prices based on promises of large purchases.

Family-owned independent grocery stores that sell in the formerly white suburbs are important buyers. Many of these are of Portuguese descent and have close relations with the Portuguese agents.

Hospitality buyers come from catering companies, restaurants, hotels, event organisers, and institutions. These include suppliers to the government’s National School Nutrition Programme which provides meals to over 9 million children every school day (Wegerif et al., 2022).

The market agents interviewed at the JFPM estimated that 50–60% of their sales – that amounted to R5649 million (USD 305.3 million) in 2024 at the lower 50% estimate – were to the informal sector. The informal traders, mostly street traders, that buy at the JFPM sell in the townships, informal settlements and run down CBD areas around Gauteng. Most use different forms of public transport to get to the JFPM and share the use of hired bakkies (Figure 2) to get themselves and their stock to where they sell. The few informal traders who have their own vehicles often share with other traders, sometimes relatives, to reduce transport costs.

These informal traders make up the overwhelming majority of the over 10,000 traders buying at the main hubs of the JFPM every day. They are creating livelihoods for themselves through their normally small- or micro-enterprises that depend on being able to source stock at the JFPM. It was not possible to get figures for the number of buyers seen streaming in and out of the Unity and Mandela markets as no records are kept of them. From observation the majority of these also appear to be informal traders buying stock. The importance of the JFPM for livelihoods was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic – which saw economic decline and large job losses—when within 1 year 3,000 new buyers opened accounts and started buying at the JFPM for purposes of reselling.

Street traders typically come to the Market daily due to having limited storage facilities and to ensure they always have fresh produce. Cedric, for example, is a young man who rents a room in Soweto and sells fruit at taxi8 ranks in the Johannesburg CBD. Everyday Cedric wakes at 2 am, takes two taxis to get to the CBD, and then walks pushing his trolley to the JFPM. After loading his trolley with fruit, he walks to the taxi ranks where he sells.9 Fifty-year-old Tiyiselani travels to the JFPM by taxi at 4 am and hires a bakkie to transport her stock home. Referring to her shop in Soweto, Tiyiselani declares “this is my baby. I am responsible for my two children and close relatives so I cannot mess this up.”

4.4.2 Farmers

Farmers are essential actors for the functioning of the JFPM as they provide the produce traded. The JFPM is in turn a very important market for the approximately 5,000 farmers that sell through the Market (Joburg Market, 2025). Farmers must be registered on the FMS and can only sell through agents so are rarely found at the JFPM themselves. Payment is made to the farmers within five business days by the agent. Both large-scale, mostly white, farmers and small-scale, mostly black farmers, send their produce to agents at the JFPM but agents prefer the large-scale farmers due to the large volume and reliability of supply. Several market agents interviewed indicated that produce from small-scale farmers was inconsistent in terms of quality and quantity. For their part, many black farmers complain about high transport costs, low prices, and poor communication. Some experienced sending stock only to be told it had rotted before being sold (Dhillon and Moncur, 2023). Despite the challenges, black farmers do sell their produce at the JFPM, those from further away using trucks that fill up by collecting from a large number of farmers. When selling at the JFPM and other NFPMs has worked better for black farmers it has been attributed to good communication with agents (Wegerif, 2022).

4.4.3 Other actors at the JFPM

There are a range of other actors at the JFPM that all contribute to the functioning of the Market. Porters, both registered and unregistered, earn money helping buyers carry their produce to waiting transport. Forklift drivers speed along the crowded platforms and narrow alleys hooting frequently as they move pallets with tons of produce. The forklift trucks are owned by market agencies and a few bigger sellers at Unity Market and get inspected and approved for operation by the JFPM management. Gate controllers are employed by market agencies to monitor all the goods coming in and out of the trading area; they check and sign receipts to ensure no produce leaves unpaid for. Security staff, many armed, are also a big part of the Market with tens’ of millions of Rands transacted there daily.

Transporters are essential for getting people and goods to and from the JFPM. Taxis are the main public transport used to reach the Market and some buyers also leave carrying produce away on the taxis. Most produce comes into the Market on large trucks; sometimes bakkies from smaller farmers. Most stock is carried out of the Market in bakkies for hire, that can be found around the Market (Figure 2), or privately owned bakkies and cars.

Numerous food vendors sell snacks and cooked food to cater for the diverse preferences and socio-economic positions of people working at and coming through the Market. There are cafes and restaurants, small kiosks and stalls made from corrugated iron and zinc, and women vendors selling tea and snacks from trolleys. Eating places, like the kiosks in the parking area, operate 24 h a day serving everything from hearty pap (maize porridge) and stew to vetkoeks (traditional fried dough bread) and tea. The eating places not only supply food but are also places where people meet, chat, and exchange Market information.

4.5 Exploring economic and social forces at the Johannesburg fresh produce market

The largest number of agents and buyers interviewed at the Market (50) considered the decision-making process of buyers to be economically rational and price was considered by most interviewees to be the main factor determining buying and selling decisions. Yet 22 agents and buyers neither agreed nor disagreed that buying was based on gaining economic advantage explaining that, although buyers want to maximise profits, they were also swayed by non-economic factors such as respect, trust, service, cultural norms, and standards. Takesure, a salesperson in the vegetable hub, elaborated further on this response saying buyers are temperamental and can cancel a transaction due to “inconsequential things.” Takesure recalled an example that occurred a few days before our interview when an older woman approached him asking the price of a sugar pocket of cabbage. Takesure gave her the price and then continued with another buyer. This infuriated the woman as she expected Takesure to give her time to consider the price before moving on. The woman went to another market agency and bought cabbage there even though the price was more than Takesure was asking.

Alfonso, a market agent of Portuguese descent, gave another example of social factors overriding price and rational choice considerations. Alfonso said he had sold butternuts for an Afrikaans farmer at R35 a sack while on the same day an Afrikaans agent sold butternuts for the same farmer for R25 a sack. The farmer had split his delivery between the two agents and was very happy with the higher price Alfonso got for him. However, the following day Alfonso found the farmer had delivered butternuts to the Afrikaans agent and not to him. Alfonso explained this by saying that the farmer likes talking to the Afrikaans agent, they speak the same language, explaining that “it is all about relationships… it’s a kind of a race thing.” Other research participants shared similar experiences.

Beyond impacting on transactions, social relations play other roles in the functioning of the Market and the value people derive from being at the Market. We observed a revealing example when a fight broke out between a registered and an unregistered porter at the Unity Market. A scuffle between the two men escalated to a full-blown fight and a growing crowd cheered them on. Security staff arrived but the fight continued, and the crowd was as rowdy as ever. Nyiko is an older black man from Limpopo Province who has been working in the market for 34 years, first as an assistant to an Indian wholesaler and then running his own business since 1997. Nyiko had been sitting quietly at his stall apparently paying little attention as the fight escalated but when the security personnel failed to contain the situation, he walked towards the fighting men. As Nyiko approached the crowd quietened and the men stopped fighting; the security personnel were then able to handle the situation. Unofficial leadership played a stronger role than the formal structures in this case and cultural norms such as respect for the elders appeared to be a factor. A group of older white men who no longer trade but come to the Market daily are respected and influential in a similar way. This small group of men sit on folding chairs at the back of the Fruit Hub where space is always made for them, and they are treated with respect by all market actors.

Access to information is widely considered as important to the functioning of markets. Buyers were positive about the ease of access to price information on the official JFPM and Department of Agriculture Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD) websites and from market agents and salespersons. Observations, however, revealed that as much as prices are freely available, there are inequalities in information access due to social networks. The dominant structure of this form of social organization and related networks was linked to cultural, social, linguistic, kinship, and the geographical origins of those involved. While the information on the websites provides prices of sales made, the buyer on the Market floor needs to find where the specific produce they needed was available at the best price and quality.

Ongoing communication between agents and their customers is essential in providing farmers and buyers with information. This communication tends to be more regular and informative when there are strong ethnic links between the agents and farmers or buyers and with preferred customers, as we saw with Mufaro. This can give some better positioned farmers and buyers an advantage over others. Smaller-scale and potentially more marginal buyers have also found ways to use ethnically based networks, through price sharing circles, to improve their access to information. For example, Rosa comes to the JFPM with a group of women street traders who all sell vegetables alongside each other in the township of Katlehong. Rosa and the other women are all Tsonga speaking and of Mozambican descent. The women arrive at the Market at around 4 am and split into groups of two: one pair loads money on the smart card (which they all share), and the other three pairs visit Unity Market, Mandela Market, and the Vegetable Hub to check the available stock and prices. The group communicate their findings to each other using WhatsApp and amass a large amount of information in a short space of time, which puts them in a better decision making and negotiating position. Rosa and her group can also take advantage of buying in bulk as a group, if that gives them a lower price, and then splitting the stock between them. Interestingly the supermarket groups, as mentioned above, use a somewhat similar strategy by sending buyers into different parts of the Market to check prices before attempting to use this information and their bulk buying to negotiate for lower prices.

Out of 45 buyers interviewed 30 said that they shop around for better prices before making purchasing decisions. Even with information gathering as groups, it is not possible to have all the information on all items and gathering information takes time whereas buyers are under pressure to conclude their purchases and get to their selling places as soon as possible. It is not surprising, therefore, that 10 buyers interviewed did not shop around for prices at all and others would check prices sometimes, but not always. A buyer for the NSNP complained that the whole process of checking prices was too cumbersome. This buyer said he preferred to use one market agent that he found reliable. For buyers not shopping around for better prices a relationship of trust with the market agent is essential. These buyers stated that they either had long-standing agreements with a particular agent or favored a particular brand only available from specific agents. For farmers, who are rarely in the Market, the relationships with agents are even more important than for buyers. Farmers have to trust that they are being given the full information and that the agent is doing the best for them.

Informal traders, such as street traders, are particularly nimble in responding to opportunities in the Market. They know when fresh produce is coming in and they also look for those times of the week and the day when agents are under pressure to clear their trading floors for new stock or get rid of stock before it starts to deteriorate. With their micro-scale operations and tactic of having a quick turnover of stock, the street traders can also take advantage of situations where part of a consignment is beginning to rot. For example, once a few tomatoes in a crate or on a pallet are turning the agent has to sell quickly and cannot demand the full price. The street trader will buy the consignment cheaply and then pick out the good tomatoes to sell.

After price, the other factors identified as most important for their decision making, in order of priority, were: quality; seasonality/availability; the brand; the cultivar; service of the agent; and market agent loyalty.

Exporters are most concerned with quality, the perception of which is strongly linked to the cultivar, as the produce has to survive long journeys to its destination. Pedro, a cross border informal trader to Mozambique, said he only exports Rugani carrots as it is a brand he trusts to have a long lifespan without spoilage. Hospitality buyers were specifically interested in the appearance of produce. Seasonality and weather is linked to availability and therefore prices due to forces of supply and demand. For instance, in 2023 dry weather combined with electricity cuts (“load-shedding”) which decreased irrigation periods resulting in a reduced supply of potatoes (SAnews.co.za, 2023). Potato prices increased by over 40% within 2 months. The informal sector traders were worst impacted as they rely on small margins and could not pass the price increase on to their customers who were already struggling financially. On the other hand, when produce is in season and saturating the Market, the traders look for good deals that can give them improved profits.

Brand loyalty stems from confidence in the quality associated with certain brands, as we saw with Pedro mentioned above. According to Andre, a market agent, informal traders generally buy name brands such as ZZ210 because with a lack of refrigeration they depend on getting quality produce that lasts. Andre elaborated that even when the price is high informal traders will club together to buy a crate of the preferred ZZ2 brand and then share it amongst themselves.

5 Discussion: lessons from the JFPM

In this chapter we discuss some of the key lessons that have emerged from the primary research carried out, as presented above, and relate these to some of the key issues from the literature. This starts with a recap of the history of the JFPM and discussion on its successes and contributions, primarily in relation to the scale of the market and the contribution to food security, and then moves onto lessons in relations to the functioning of the Market and the challenges that exist.

The JFPM emerged out of a long history that started in the market square of the late 1800s mining town of Johannesburg. As such it has shown tremendous resilience and an ability to adapt through dramatic events such as the Boer War, and the transition from colonial to apartheid rule and then to a non-racial democracy. This resilience also confirms the need for such a market as sellers and buyers have used the platform for over 130 years.

The highly regulated system of selling through registered agents has been long established with good intentions of protecting the interests of farmers by regulating the commission charged, holding agents accountable, and having an orderly market. The dominance of white agents, themselves ethnically divided, has colonial and apartheid roots with links to the structure of land ownership and farm production in the country. Informal traders, always from marginalised groups – more of Indian descent in the past, now almost exclusively black and African with many originally from other parts of Africa -, played a key role in the viability of the Market historically and still do today.

The JFPM is made up of both an extensive collection of infrastructure and a wide range of actors that combine informal and less formal relations to enable a large volume of trade in fresh produce. This is done quite cost effectively with the maximum combined commission for the Market and agents coming to 12.5% of the wholesale price, which becomes a considerably smaller percentage of the final retail price.

The volume and value of trade going through the JFPM indicates its importance in the national fresh produce sector. Handling around 20% of the value of all fresh produce produced and sold in South Africa and with annual sales of over R11 billion (USD 595 million) the JFPM is clearly important for the 5,000 plus farmers selling there and the tens of thousands of buyers, most of whom run business that depend on the JFPM for stock. The JFPM also appears to be financially viable, even generating surpluses of around R100 million (USD 5.4 million) per annum for the CoJ.

Fresh produce is of particular importance for healthy diets (FAO, 2020) and therefore food and nutrition security in the context of the triple burden of malnutrition that is so prevalent in South Africa (FAO, European Union, CIRAD and DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 2022). As we have seen above, the JFPM is an essential node in the supply of fresh produce and the bulk of this is going out through small-and micro-scale informal traders who are selling at low prices to buyers with low incomes. The JFPM makes a multifaceted contribution to food security across the six dimensions of food security as articulated in HLPE report 15 (HLPE, 2020), particularly the dimensions of food accessibility and agency. The CCSA also concluded in their study published in 2025 that: “(national) fresh produce markets are crucial to food security, food health and safety, and local economic development” (CCSA, 2025, p. 2).

The ubiquity of the informal traders at the JFPM indicates their competitiveness, showing that they play a key role in making fruit and vegetables accessible. A number of studies have confirmed the importance of the informal sector to food access in low-income areas (Battersby et al., 2016; Battersby and Watson, 2018a; Rudolph et al., 2021; Wegerif, 2024). Several recent studies have specifically confirmed that fresh produce bought from street traders, who primarily source food at the municipal markets including the JFPM, is cheaper than that from supermarkets and other formal sector outlets (Wegerif, 2024; Sithole, 2024). The same studies showed that street traders also make fresh produce more accessible in ways other than the low prices, such as the location of sale that is convenient and removes transport costs. The ability of the informal traders to outcompete other retailers, such as supermarkets, is directly linked to the access they have to good quality produce at low prices at the JFPM and other NFPMs.

In addition to making food accessible for others, the informal traders - many of them from impoverished and vulnerable groups such as immigrants from other African countries - are creating livelihoods for themselves, thus contributing to their own ability to buy food and achieve their own food security.

The JFPM enables the agency of a wide diversity of actors involved in fresh produce production, distribution, retailing, packaging, transporting, and consumption. This creates large economic multiplier effects across the agri-food system and the wider economy, thus contributing to job creation and business opportunities. The JFPM creates a very open platform where farmers from the smallest to largest scale can sell. It is a place where, with the Mandela and Unity Markets as well as the Main Hubs, buyers from individuals and street hawkers, through to the largest supermarket groups, can and do come and buy. Through the diverse range of retailers that source stock at the JFPM, customers are given a far greater variety of options. The JFPM is thus ensuring choice, and through that agency, for many actors in the fresh produce sector. Without the JFPM and other fresh produce markets it is highly unlikely that the dynamic informal sector fresh produce retailers would exist at anywhere near the scale that they do. Even for the supermarket groups the JFPM remains an important source of stock, including as a supplier of last resort when their direct supply chains fail (CCSA, 2025).

As we looked at how the JFPM is organised, we also came across serious challenges, which pose a threat to the effective performance of the Market’s role. Many of the actors at the JFPM complained about poor management over the last years, which coincides with political instability in the CoJ that has contributed to governance instability. The biggest concern, raised repeatedly by agents, is the decaying infrastructure that is negatively affecting their operations and the viability of the JFPM as a place to do business. Among other issues, the Market halls are overcrowded, there is a lack of insulation in the buildings leaving them too hot in the summer, and the failure to maintain generators has left the Market, in particular its cold rooms, unable to function during some electricity cuts. The level of general upkeep also determines the extent to which the JFPM is attractive to customers and a pleasant place to work and do business.

It is encouraging that as this article was being written the new Tshiamo Market building started operating providing increased shelter and storage space for traders (Mamabolo, 2023). However, not all the planned new infrastructure, such as additional cold rooms, had been completed. Further capital expenditure has been budgeted at R98 million (USD 5.3 million) for 2024/25 year and R107 million (USD 5.8 million) for the 2025/26 year (CoJ, 2023). Whether this is adequate and how effectively it is used remains to be seen.

Crime both within and outside the JFPM is another factor that is impacting negatively. Many stories were told of people who were robbed and assaulted while on their way to the Market in the early hours of the morning. While crime is part wider societal challenges, it is possible for the JFPM, along with the CoJ and their Johannesburg Metro Police to make more efforts to improve the situation for workers and customers coming to the Market.

The JFPM has slightly grown the volumes of produce traded there in the last years, but the proportion of the total fresh produce sales in the country going through the JFPM and other municipal markets has declined. According to well informed research participants this decline in the municipal market share of the sector is chiefly attributed to the increased use of direct buying by large supermarket groups through their supply chains. As the supermarkets buy less at the JFPM, the informal traders are filling the gap, but the declining share of the Market is a concern. The increasing concentration of ownership in the South African food system, in particular by supermarkets, has been critiqued for the way it limits the options for small-scale farmers who cannot meet the high volume and quality requirements of supermarkets (Chikazunga et al., 2008; Greenberg, 2017; Heijden and Vink, 2013). This threat from supermarket supply chains to the central role of the JFPM could affect farmers selling there and the informal traders and others buying there.

A lack of transformation, given South Africa’s apartheid past, is a concern frequently raised by agents, farmers and the JFPM management. This lack of transformation is most noted in relation to the limited proportion of the supplies coming from black farmers and the limited value of produce traded by black agents. Interviews with black farmers and salespersons indicated that their limited capital combined with cultural barriers to entry, given the entrenched ethnically based relations between and among white farmers and agents, are leading bottlenecks to greater equity at the JFPM.

The findings presented in the previous chapter highlight that the functioning of the JFPM involves a complex interaction between economic and social forces within a regulatory environment that combines free market discourse with high levels of market regulation.

The economic forces of supply and demand and utility maximization clearly play a big role in the functioning of the JFPM. Social relations are also key to the operation of the JFPM and have a bearing on transactions there. The social and economic interests set parameters for each other as seen in how price can lure a buyer to an agent they are not familiar with, while at other times a buyer or seller will work with an agent they are more comfortable with even when this means they do not get as good a price.