- 1International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), CGIAR, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Institute of Development Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

In Nampula province, Mozambique, internally displaced and refugee communities live in settlements situated at the outskirts of Nampula city. This paper explores the intersection of gender and food systems in displacement contexts by focusing on the experiences of displaced populations and examining how displacement exacerbates existing gender inequalities and shapes access to food resources and livelihoods. It delves deeper into the barriers and opportunities men and women face in orienting themselves within food systems in displacement contexts. A participatory rural appraisal methodology, disaggregated by gender, was implemented in displaced communities in Nampula. The gendered analysis found that displacement dynamics affected food systems, where gender dynamics play a central role in determining resilience capacities. The findings of this study contribute to the scholarship on the nexus between climate security, food security and gender, bringing internally displaced and refugee communities into the fore of food system discussions.

Introduction

Food insecurity does not happen in a silo. Rather, it results from a range of social, political, climatic and ecological disturbances that impact food systems in varied and multifaceted ways (Bryan et al., 2023; FAO, 2008, 2023b; Pingali et al., 2005; Queiroz et al., 2021; Tendall et al., 2015; Wezel et al., 2020). Within these food systems, gender emerges as a significant stratifier and definer of how different groups experience and respond to these disturbances. Food systems are defined as complex systems that

Encompass the entire range of actors and their interlinked value-adding activities involved in the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food products that originate from agriculture, forestry or fisheries, and parts of the broader economic, societal and natural environments in which they are embedded (FAO, 2018, p. 1).

Globally, climate and conflict-related risks are rising, posing significant threats to food system sustainability and food security (IPCC, 2023; United Nations, 2023). Such hazards force the number of displacements to rise (IDMC, 2024; IOM, 2024a,b), generating contexts of multifaceted vulnerability that drive food insecurity (IDMC, 2023; Queiroz et al., 2021; Vos et al., 2020). In this paper, displaced persons are understood as

Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, either across an international border or within a State, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters (IOM, 2019, p. 55).

To build resilient food systems that can withstand ongoing and future climate security shocks, gender must be a key consideration (Bryan et al., 2023; Sachs and Patel-Campillo, 2014). This paper explores resilience at both the individual and systemic levels. Generally, resilience is understood as the capacity of individuals or systems to “bounce back” from various shocks and stressors (Holling, 1973; Tendall et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2004). This conceptual understanding informs the exploration of resilience used in this paper. At an individual level, resilience refers to the ability of a person to adapt, cope, and recover from shocks while maintaining their overall aspects of human security and well-being (Garmezy and Masten, 1986; Hirani et al., 2016). Resilience is shaped by gender, socio-economic status, age, cultural background, and access to resources and support systems. Similarly, food system resilience refers to the ability of a food system to maintain food security despite disruptions, challenges, or shocks, such as natural disasters, economic instability, or supply chain disruptions. It is about how effectively the system can adapt, recover, and continue to provide sufficient, nutritious, and accessible food after shocks. Various contextual factors, including the adequacy of food production, accessibility of markets, availability of resources like water and arable land, and the overall infrastructure supporting food distribution influence the capacity for resilience in food systems (Tendall et al., 2015). Thus, food system thinking offers a holistic understanding of the myriad of disturbances and influences that affect food security at both a micro and macro level.

In displacement contexts, food systems face specific challenges and vulnerabilities. Displacement settlements are often situated in makeshift contexts, which may alter access to markets, trade, land and the availability and access to resources (Conca, 2024; FAO, 2023a; Queiroz et al., 2021). Lacking access to the various factors that make up a resilient food system, such as a profitable market economy and available natural resources and productive inputs, threatens food security. Furthermore, displacement contexts are highly vulnerable to climate hazards due to the limited infrastructure and poor socio-economic conditions. The compounded, repeated, and prolonged pressures within displacement contexts render these food systems volatile with limited capacity for resilience (IDMC, 2023; Pingali et al., 2005; Queiroz et al., 2021; Vos et al., 2020).

While all people have a role to play within food systems, the role each person plays is, at large, determined by gender. Different genders have varied access to opportunities within a food system. For example, their exposure to disturbances, the capacities that individual has to respond to that disturbance as well as the institutions that govern the individual’s opportunities, such as legislation, cultural norms and decision-making structures all influence gendered experiences (Bryan et al., 2023). Globally, women still face notable structural challenges and barriers within food, land and water systems as these systems are entrenched in patriarchal practices that define most societies (Bates, 2016; Hooks, 1984; Mahmood, 2001). Structural limitations on women globally translate to women having significantly less access to land ownership as well as control and access to the broader food value chain, with gender differences noted in access to transportation, production rates and market participation (FAO, 2023c; Maereka et al., 2023; Odiwuor, 2022). Additionally, women are also highly responsible for reproductive care work within the household, limiting their opportunities for paid employment and broader market access (Anwar et al., 2019; Choudhary and Parthasarathy, 2007; Dickin et al., 2020; Sachs and Patel-Campillo, 2014). On the other hand, while men are more likely to access paid employment, they are often required to migrate across borders to access work (Crush, 2013; FAO, 2023c; Hampshire and Randall, 1999; Rao et al., 2019a; Sturridge et al., 2022). In displacement contexts, these gendered differences shape experiences within food systems at the intersection of gender and displacement, and thus, understanding these nuances plays a crucial role in food system transformation and sustainability.

Despite the protracted realities of displacement, much of the discourse regarding food security in displacement contexts focuses on short-term coping rather than adaptability and resilience (Abdel et al., 2014; Arhin et al., 2022; George and Adelaja, 2022; Horn, 2009; Sassi, 2021). While coping mechanisms tend to be short-term solutions to shocks, often associated with already deteriorated well-being, adaptation mechanisms aim to pre-empt and minimize harmful impacts in the longer-term (Bryan et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2004). Rather than understanding the protracted development needs required, responses to food insecurity in displacement contexts are often reactive, responding to a series of immediate shocks, leaving the food systems reliant on aid, which may hinder local production and market trade (de Coning, 2016; Gibson et al., 2005; Pingali et al., 2005; Tschirley et al., 1996). For refugees living in Syria and Jordan, for example, despite 90% receiving food aid, refugees grappled with deteriorating food security, resulting in the use of coping strategies such as skipping meals, reducing portion size, and selling food aid to purchase larger quantities of food (Doocy et al., 2011). This reality is mirrored in many displacement contexts, where what was meant to be a journey towards stability and a safer life, results in a protracted and even life-long food insecure displacement (Bellino, 2018; George and Adelaja, 2022; Wesley Bonet, 2021).

The protracted displacement reality and high insecurity underscore the critical importance of building sustainable food systems and food security in these contexts. While many displaced communities rely heavily on coping, longer-term adaptability and resilience emerge in some contexts. This can, for example, be seen in Ghana, where mining-induced displacement resulted in mobility from rural to urban areas, leading communities previously dependent upon agriculture to turn to other sectors for income, with many engaging in multiple sectors and mixed farming practices (Arhin et al., 2022). Such stories indicate a need to understand how resilience and adaptability emerge in displacement contexts and what barriers displaced populations face in building sustainable and resilient food systems. As displacement is on the rise, it is key that food systems transform to adopt sustainable and resilient practices that go beyond pure ecological emphasis but also build equitable and just food systems that uphold food security under current and foreseen climate security pressures (Gliessman, 2016; Shiva, 2014; Webb et al., 2020; Wezel et al., 2020).

While gender is becoming an increasingly popular topic within climate-responsive science, particularly within the Southern Africa region, and a key research field for food system sustainability, evidence is lacking on gendered dynamics within displacement contexts. This is despite these contexts being highly climate-affected and climate effects being highly gendered (Bunce and Ford, 2015; Dunn and Matthew, 2015; Smith, 2022). While this study has utilized ‘men’ and ‘women’ categories in the data collection, as advised by local partners, we conceptualize and understand gender in its broader form, understanding gender to be a social construction (Butler, 1990). As such, we understand the opportunities and barriers faced by different genders as at large socially, culturally and politically constructed and thus, these gender norms can be shaped and altered in contexts such as displacement. We recognize the significant shortcomings of non-cis inclusion in this paper. Current gender data tend to hold a heavy focus on women and girls’ vulnerabilities, a trend which has left other gender voices largely excluded from the research agenda, including men and boys as well as non-cis voices and intersectional experiences (Bunce and Ford, 2015; Carr and Thompson, 2014; Maviza et al., 2024; Quisumbing and Doss, 2021; Smith, 2022). The skewed focus on women’s vulnerabilities necessitates a shift away from the narrative of lacking female resilience and male vulnerability, to centre a broader array of voices into knowledge generating and decision-making spaces (Henry, 2021; Smith, 2022). As Dunn and Matthew (2015, p. 159) argues,

This is not to suggest that centering research on women is not useful, but rather that a gender analysis requires consideration of how men and women are affected differently because of how gender-specific roles and norms are constructed in particular contexts and in the international sphere (e.g., within international organizations). Familiarity with both sets of roles and norms is essential to a nuanced gender analysis.

While recognizing unequal power relations within agrifood systems is key for achieving equity within these systems, understanding men’s experiences is not only essential for understanding male vulnerability but also for how women are affected by changing male realities in displacement contexts and vice versa.

In Nampula, Mozambique, the challenges that emerge at the intersection of climate and conflict hazards leading to displacement are plentiful. Since 2017, violent conflict has been ongoing in Cabo Delgado, leading to large numbers of internal displacements, particularly within the northern provinces, including Nampula (ACLED, 2024; UNHCR, 2024). Additionally, Mozambique is facing severe impacts of climate change, including droughts, floods and cyclones, which impact infrastructure and land use systems, further exacerbating human security risks (Human Rights Watch, 2019; OCHA, 2023). As a consequence of these ongoing challenges, as of January 2024, it was estimated that approximately 835,834 Internally Displaced People (IDP) reside in Mozambique, of which 21% had been displaced due to extreme weather events and the remaining fleeing the armed conflict in Cabo Delgado (UNHCR, 2024). Food insecurity is at the heart of displacement impacts. In 2022, 75% of the countries facing severe food insecurity worldwide have IDPs (IDMC, 2023). This is a trend clearly reflected in Nampula, where food insecurity rates are the highest nationally, with approximately 335,000 severely food-insecure people living in the province (FAO, 2021; OCHA, 2024).

Thus, escalating numbers of forcibly displaced persons render it necessary to understand how food systems are affected by such contexts. Understanding this dynamic will help build sustainable food security for the over 110 million people facing displacement globally, living in what is becoming an increasingly prominent and protracted reality (IDMC, 2024; UNHCR, 2023). This paper seeks to improve the understanding of gendered dynamics within food systems in displacement contexts. By focusing on intersections between displacement and gender, we aim to contribute to filling some of the existing knowledge gaps regarding gender dynamics in food system and forced displacement science, in order for academia and responsive organizations to build inclusive and durable solutions to ongoing and future challenges.

Methods

Study area

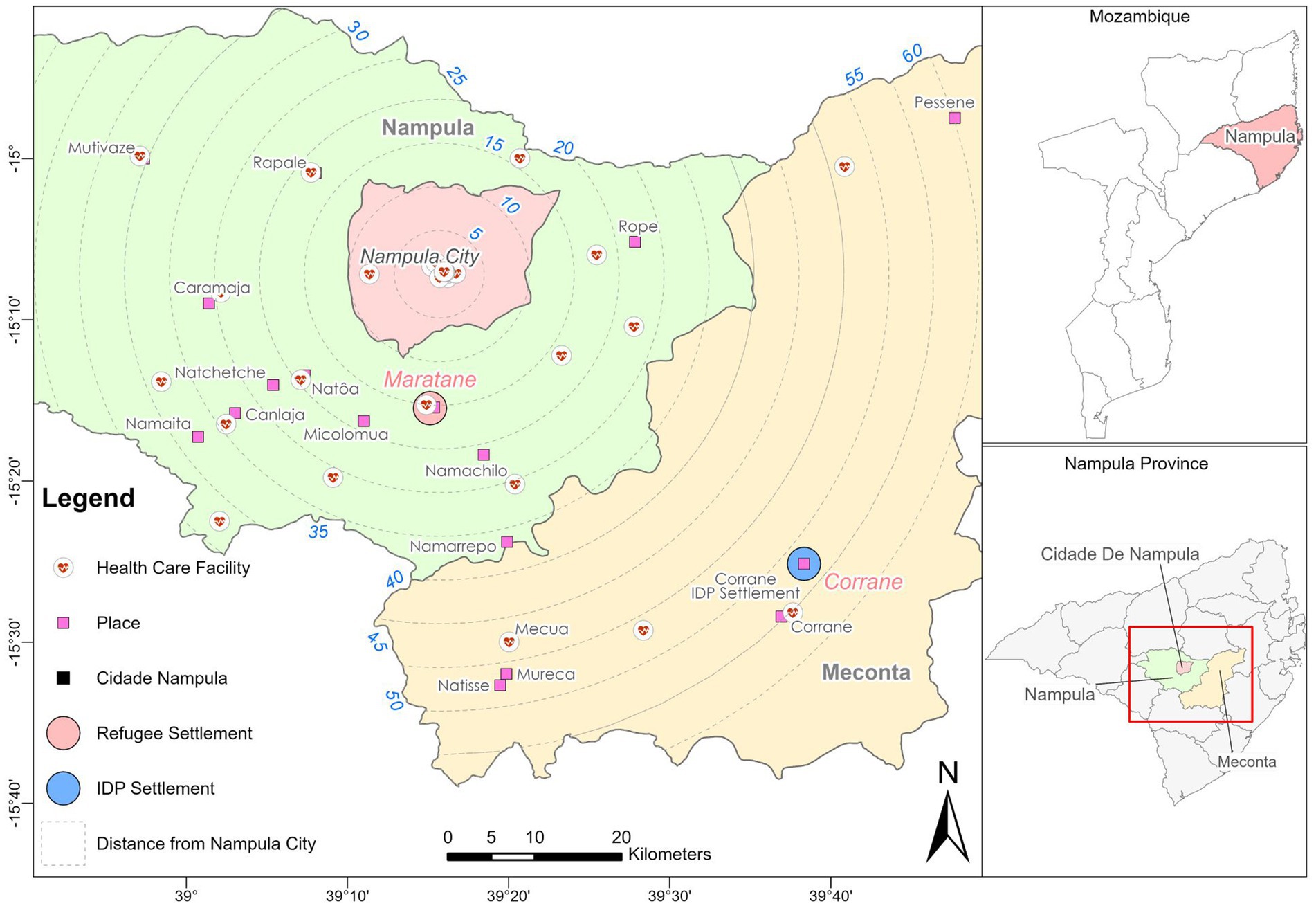

The research took place in Corrane IDP Settlement (CIS) and Maratane Refugee Settlement (MRS) in Nampula province, northern Mozambique. CIS was established in 2020 to provide temporary shelter and essential services such as food, water, sanitation, health, and education to thousands of IDPs fleeing violence, conflict, and insecurity in the northern region of Cabo Delgado. The conflict in Cabo Delgado has led to widespread displacement, economic disruption, and increased humanitarian needs. The settlement has a population of approximately 7,000 IDPs (IOM, 2022). MRS was established in 2001 to accommodate refugees fleeing conflicts in their countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Burundi, Rwanda, and Somalia (UNHCR and WFP, 2022). MRS is Mozambique’s only official refugee reception centre (UNHCR and WFP, 2022). The settlement hosts around 9,000 refugees (although this number is contested due to people frequently moving in and out of the settlement). Most of the people (86%) in MRS have been living there for between 5 to 20 years, making protracted stays a common reality (UNHCR and WFP, 2022) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Nampula Province, including Corrane IDP settlement and Maratane Refugee Settlement.

Data collection methods and tools

The study employed a qualitative approach to obtain in-depth data on participants’ lived experiences with food systems in displacement contexts. A participatory rural appraisal (PRA) methodology was adopted to center the diverse lived experiences of the displaced and host communities. Data collection took place across 5 days at each site. Activities included a transect walk of the settlement and the natural resource landscape within the community and the surrounding area. The building of a historical timeline of the social, political, climatic and environmental events and changes to the environment. Resource mapping also took place, with participants being asked to map the resources in their area and discuss how the resources (or lack thereof) impacted them and how these were impacted by the wider socio-ecological ecosystem. Furthermore, all groups were asked to map and discuss the main challenges in each site and develop solutions to these challenges by identifying the needs and actions required. For each focus group discussion (FGD), five to ten open-ended questions were developed to gain insight into topics related to climate, conflict, natural resources and gender, asked along each PRA activity. A specific gender discussion also took place in each group where participants were asked questions related to gender norms, values and experiences within their communities. Gendered questions were also mainstreamed throughout the methodology. Data collection was done over a period of five days with men and women engaged separately in each site.

Study participants

Participants were sampled at each site in collaboration with community leaders and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The study involved a total of 50 participants, 25 in MRS and 25 in CIS. In each site, participants were divided into two groups categorised by cis-gender, each with 8 to 15 volunteers. In MRS, participants spoke various languages depending on their country of origin, with the majority speaking Swahili, French and English, while some spoke basic Portuguese. In CIS, participants spoke a mixture of Makuwa and Makonde and some also spoke Portuguese. To bridge the language gap, translators were used in both settlements. To triangulate the data, Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were conducted with ten officials from UNHCR (2 women, 1 man), government departments (2 women, 1 man), and community leadership structures within the settlements and host communities (3 men, 1 woman).

Data analysis

The qualitative data gathered was analysed using thematic analysis. The verbatim quotes detailing the participants’ experiences were thematically coded and analysed. Coding entails categorisation data in qualitative research (Maxwell, 1998), where the researcher identifies and groups data under distinct themes and uses the identified themes as master headings that guide the analysis (Flick, 2013; Gibbs, 2007). For this paper, the authors deductively coded data guided by the themes emerging from the data in accordance with the research question. The deduced themes formed subheadings under which findings, supported by direct interview excerpts, were presented and discussed.

Findings

The findings in this paper highlight the gendered dynamics of food systems within displacement contexts, revealing their interactions with external factors like climate change and humanitarian aid, both of which are central to food systems affected by displacement. The data generated revealed four key themes: the volatility of food systems, the gendered nature of these food systems, the impacts of climate variability and change on food systems, and gender biases in humanitarian assistance in displacement contexts. These themes are explored in detail in the sections that follow.

Food system volatility in CIS and MRS

In general, the food systems in CIS and MRS were highly affected by displacement. Climatic and environmental hazards coupled with a violent history of colonialism, conflict and political instability have left Nampula a place where sufficient access to food is not guaranteed. Frequent and intense droughts, floods and cyclones have rendered the land less fertile and local food systems extremely volatile. As a result of this high food system volatility, all focus groups noted significant food and nutritional insecurities, particularly following extreme weather events. Some of the respondents narrated it this way:

“[Men and women] are facing the same problems since they came here [Corrane settlement], no food, no food, no food” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

“We’d prefer to die of hunger in Corrane than to die before the war in Cabo Delgado” (Man FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

“Here it is very difficult, it’s difficult to get money for food. It’s difficult to get a job” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

“We eat little food, but we have survived. Some ran away, and others died from hunger” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

The testimonies from CIS and MRS starkly illustrate acute food system volatility arising from the intersection of displacement and poor socio-economic conditions, evidenced by the emphatic reports of food scarcity. This disruption forces trade-offs between safety and sustenance, emphasising the profound destabilising effect of conflict-induced displacement on food system resilience. Furthermore, the challenges in income generation within the settlement highlight the critical role of socio-economic capital in securing food access, revealing the volatile interplay between economic stability and nutritional security. The tragic reality of differential survival outcomes, with some surviving on meager rations while others perish from starvation, serves as a poignant indicator of the catastrophic human cost associated with such extreme food system volatility, underscoring the systemic failure to ensure basic nutritional needs within the displaced population.

Reliance on humanitarian aid in both CIS and MRS further exacerbates food system volatility. While essential for immediate survival, this dependency can undermine the development of sustainable local food production and market integration. Fluctuations in aid distribution, often influenced by external factors and donor priorities, create periods of acute food insecurity, particularly when coupled with environmental shocks. Furthermore, the influx of aid can sometimes disrupt local markets, depressing prices for small-scale producers and hindering the emergence of independent livelihoods. The limited access to functioning markets and the constraints on alternative income-generating activities trap residents in a cycle of vulnerability, making them highly susceptible to any disruption in aid supply or environmental conditions.

Despite the challenges, people in both settlements have adopted several mechanisms to build food security, with the settlement structure generating new and emerging systems and opportunities for collaboration and learning. This became evident in CIS, where participants requested that the Makuwa word “Okhaviherana” be included in this work due to its great importance in the community and in building sustainable food systems, meaning ‘the spirit of solidarity’.

The gendered nature of food Systems in Corrane and Maratane

One of the broader themes emerging from the findings is the nature of food systems in the two sites. Emerging subthemes under this broad theme, namely, Access to farming Land, Access to Natural Resources, Access to Markets, and Decision-Making, Power, and Control, all speak to gender differences noted in the local food system, including food production, distribution and processing. The way these differences emerged varied depending on the context. Despite differences, food insecurity was high for all genders. The data shows that the food systems in CIS and MRS are fragile but adaptive, reflecting the complex interplay of displacement, environmental stressors, and socio-economic dynamics. Findings on the subthemes are presented in the following subsections:

Access to farming land

“The major issue is that the host community won’t give land freely. If you want to get [a] machamba [land], be prepared it won’t be free” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

Land is a key element in food systems, especially in agro-based communities. It is a critical asset which is very scarce in displacement contexts in general (Vos et al., 2020), and Nampula is no exception. When MRS was first established, both the host community and refugees tell a tale of available land and generous aid. Despite limited climatic disturbances at the time, the adequate aid distribution meant that the refugees “did not cultivate nothing in 2002, because we were receiving food aid” (Woman FDG participant, MRS, Dec 2023). The host community explained how the refugees had come to them for food and work, and that land, food and water had been shared. However, tensions grew as the refugee’s stay protracted, population pressures grew, and government aid was unequally distributed to refugees over host community members. Collaboration slowed down as explained by KIIs from the host community, “they would say they are helping the refugee communities, but that they would also help the host communities, but this support never came” (Man, host community KII, MRS, Dec 2023). With the protracted and increasing refugee population, the host community “had to move their farms further out toward the mountains to accommodate the refugees” (Man, host community KII, MRS, Dec 2023). However, with time, tensions surfaced as host communities began reclaiming ‘their’ land from the refugees.

While all land in Mozambique is under public ownership (Constitution of The Republic of Mozambique, 2018; Jacobs and Almeida, 2020), the government can allocate land for individual usage. In both MRS and CIS, land was allocated to provide the displaced communities with sustainable livelihood opportunities. This equated to approximately 42 × 70 m plots each in CIS (according to male IDP participants), given to early arrivals. In MRS, The National Institute for Refugee Support (INAR), allocated approximately 2000 hectares of land to be utilised by the refugee population following a reduction in aid. The land allocation in MRS included the settlement, non-arable areas as well as areas far from the settlement, leaving limited arable land available and accessible for food production. Despite efforts from government institutions to peacefully implement the land allocation, the initiative was not recognised by the host communities in either settlement. Tensions quickly arose over rights to land as one participant explained “the land that the government gave was taken by local landowners. If you fight with the local landowners, you die” (Man FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

These tensions impacted food production in multifaceted ways. When discussing the conflicts, the refugee community reported frequent cases of sexual assault as well as the destruction of food supplies, including the burning and stealing of crops and the burning down of the market structures within MRS. One refugee man narrated that, “my wife left 1 day to go to the fields alone and was raped by some man from the host community to send a message to all of us that we should not come to their land,” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Yet, although tensions persist amongst displaced and host communities, it was also evident that the influx of refugees had generated positive outcomes for the local food system. One host community KII explained, “because the refugees arrived, [I] learned how to crop tomatoes” (Man, host community KII, MRS, Dec 2023). The KII explained that host communities have adopted successful home-based horticulture practices during the agricultural off-season, where they plant vegetables in their kitchen gardens. This shift occurred following the arrival of refugees, who introduced the necessary techniques that the host communities previously lacked.

Due to the limited arable land and tensions, most participants reported utilising spaces outside their homes for small kitchen gardens, mainly for household consumption. These were largely managed by the women in the household. Those unable to cultivate within the settlement or with access to financial means would rent land from host communities. In both settlements, men were more likely to own land than women, but women were more likely to rent land. In Mozambican culture, particularly in the northern provinces, matriarchal lines are common, yet while property is often passed to women, land remains in the hands of the male head of the household. This was reflected in the communities in CIS, who had travelled from Cabo Delgado where such practices are common.

“Within the family the land belongs to the man. But if a woman is alone, she can also own [land]. In terms of the house, the right of the house belongs to the women. Because the one who will be living with the children is the woman not the man. If you come as a man to marry someone else, you are aware that the house belongs to her. Culturally in northern Mozambique, there is a matriarchal system. If you come to the family, when you decide to divorce, you leave everything there” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

As MRS hosts people from a range of different backgrounds and cultural contexts, practices differed depending on the cultural norms of the household. Focus group discussions revealed that land ownership rights were significantly lower for women than for men living in this settlement.

“In our culture, a woman is not allowed to own anything” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

“According to our culture, a married woman cannot own anything unless she is single” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

This also meant that women were more likely to rent land from host communities than men. While in both settlements, the host community rents land to the displaced communities, challenges persist, particularly due to high rental prices, lack of contracts and violence perpetrated in the fields. Due to women’s central role in agricultural production, these issues were particularly prominent amongst women participants.

“Nobody owns land, but they rent it. Some of the women rent. They have never gotten [a] document [contract]. They rent for 3 months, after that it’s finished. After 3 months they renew the contract [verbal agreement]. It depends on prices, if you produce a lot, the condition to renew will be high. They can tax you more than what they did before. You have to pay before you start. You also have to give a bit of the produce, the amount depends on how much you produced, it can be 5 or 10kg of the produce” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Women also accounted for the majority of food production in both settlements, particularly within the agricultural sector. The cultural contexts differed in each settlement, with the displaced and host communities in Corrane noting that both men and women work in agriculture and contribute equally when working in the fields. This was not the case in MRS where the women explained that:

“Women go the most to the field, men don’t go there. Women go there to plant, men only go to observe” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

“Women are responsible for producing food. Single women alone with their children. The men do nothing, the women are the only ones who go to machambas, to clean, plant and cultivate everything” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Access to natural resources

“We are refugees here in Maratane. We don’t have any natural resources” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

With limited access to land, the natural resource landscape is crucial for achieving food security in displacement contexts. Access to natural resources, such as forests, water and land systems depends upon an array of factors, in which gender and displacement intersect to play a crucial role. All groups within the displacement contexts reported limited access to natural resources within and surrounding the settlements. Differences mainly presented themselves in what type of resources were lacking for each gender. While women tended to focus on food-related resources for the household, e.g., fruits, animals etc. men focused on economic opportunities such as charcoal and fishing for profit. While charcoal production is a common livelihood strategy for communities in Nampula, this was not a commonly reported mechanism utilised by the displaced communities due to the surrounding forest areas being owned by host communities. This presented an issue, particularly for the men who expressed a wish to engage in charcoal production to improve their livelihoods.

Fishing was also a key resource in both settlements, largely managed by the men. Mozambique’s vast coastlines make fishing a common form of livelihood across the country. In both settlements, men and women noted fishing to be a key avenue for food security, yet no women reported participation in the sector. However, due to the limited sample, we cannot conclude that this applies to all. In CIS, many of the IDP men had worked as fishers before their displacement. As Nampula is located approximately 200 km from the coast, fishing opportunities are scarce. This is made worse by the limited infrastructure connecting the settlements to the wider area. The men explained that they utilised social networks surrounding the Nampula area and would travel during the week to fish and then return to CIS during the weekend. Yet, lacking equipment proved a challenge for many, including fishing nets, ropes and boats.

The women in both settlements reported utilising natural resources in and around the settlements. Some reported hunting rabbits and rodents to boost food security. Fruit trees and plants in and around the settlements were utilised but access to these resources was significantly limited due to host community tensions and lacking land ownership. Even within the settlements, most fruit trees were privately owned by the host community, and so picking of the fruit was seen as theft with harsh punishments expected (corporal mutilation). Nevertheless, in both settlements the women showcased great knowledge of the local trees and what areas they were allowed to harvest from. They also noted changes to the surrounding forests due to climate change.

“The trees along the road, they don’t have an owner. The trees by the machambas belong to the Mozambicans. There has been changes in the trees, the number of trees have reduced. There is limited access to shade. In the rainy season, when there is wind, they [Women, MRS] can see that the trees were so useful, the wind [without the trees] impact directly on their houses. Cyclones have reduced the trees, some of them are affected by specific diseases and some were too old” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Access to markets

Market access differed significantly in both settlements. MRS is located approximately 30 km from Nampula city with good road infrastructure and regular public transport for the price of around 100 MZN. CIS is located approximately 60 km outside of Nampula city with limited infrastructure connecting the city to the settlement. The main road to CIS is poorly maintained and highly vulnerable to floods, significantly restricting movement outside of the settlement during rainfall. Transport from CIS to Nampula City costs around 400 MZN. The closest larger market to CIS is in Corrane Town, approximately 4 km from the settlement, with a shuttle costing about 100 MZN. Due to the high cost of transport and the consequential need for prioritising who to send, in addition to the household’s dependence on women’s domestic labour, men were prioritised for wider market access and urban errands. In both settlements, traditional gender roles permeated the household, with women being primarily responsible for household labour. As the men explained, “Women are better than men at everything about the house; they take care and [are] better housekeepers than men” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Local market access also differed in both settlements. As MRS is in closer proximity to the city and has been established for a greater period, markets in this settlement had a greater variety of choices in comparison to CIS. MRS boasted a greater variety of produce and products sold, including vegetables, fish and cooking tools as well as other essential items such as oil, sugar, spices and clothing. Several businesses were also spread around the settlement including a restaurant, seamstress and a bar.

At the time of the visit, the CIS public market consisted of dried fish, okra, tomato, mango and banana as well as some clothing. One store was selling household essentials including soap, sugar and tea. The women in CIS noted that this store was essential to get a hold of “things you can find in the city.” The lack of access to markets in CIS limited food choices and meant that the food systems remained hyper-local, restricting financial circulation within the settlement. Although the men brought in fish from surrounding areas, produce was limited and few opportunities for trade existed.

“The market problem is linked to the lack of money. No money, no market. No market no employment. The lack of market [variety] is also linked to machambas [lack of yield] because you can’t sell anything [leading to a] lack of food at the market. What the market has is not what we want” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

Spatial price discrimination was evident in the disparity between the urban and the settlement market prices. Goods originating from the city, such as soft drinks, commanded higher prices within both settlements compared to their prices in Nampula City. Conversely, certain locally produced goods, such as meat, were more affordable within the settlements and rural communities, attracting consumers from neighbouring areas, including Nampula City, who recognised the opportunity for cost savings. The consequence of this spatial price discrimination was twofold. The higher costs of city-originating goods for displaced communities impact their purchasing power and potentially reduce their overall consumption levels. On the other hand, the lower cost of locally produced goods facilitated an influx of consumers from neighbouring areas into the settlements, bringing economic benefits. The gender differences in market access coupled with spatial price discrimination, reduce women’s opportunities to make adequate profit as they are less likely to engage in trade and wider market opportunities. The women reported a lack of access to food processing tools, such as to cooking equipment and mills. In CIS, the women explained that access to mills would enable them to start a business, as they could sell baked goods in the local area. However, the lack of cooking equipment made it difficult to earn a profit from processed food. Despite some women having received culinary education, limited access to tools and financial credit hindered their ability to access and capitalise on business and employment opportunities.

Decision-making, power, and control

“At home the man remains the chief of the family” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

The women explained how although they controlled the money and purchased food, decision-making remained with the male head of the household.

“If they [the household] have money, it is the woman who controls the money. The man decides what the money is used for. It’s difficult because the man can’t control the money. Women know that if the man controls the money, one day he will take it and drink with his friends. So, if the women keep the money, it will be used in the proper way. The plan is coming from the man, but it is controlled by the women” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

However, the women noted that while this was the overall trend, this differed depending on the household.

“We can’t generalise issues. There are different scenarios. In some families, the man, after some work, if he earns money, he will show his wife and together they will decide how they will use the money. In other families, even if the husband and wife work together, the women will not see the results of the work. The man will keep the money and he will never share the money with her” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

The general lack of financial decision-making power for women within the household highlights persistent gender inequalities that not only affect economic control but also lead to broader social issues, including domestic violence.

“There are disputes between men and women over resource access. Some of them fight against each other physically, some cases are reported to the police. Others are only verbal and psychological violence” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

While violence and conflict over resources often manifest as male-to-female violence, instances of violence against men were also reported, underscoring the complex dynamics of power and conflict within households. In response to these challenges, the women had developed adaptive strategies to maintain food security. For instance, some women in MRS sought to rent land for farming to ensure food production in cases of financial mismanagement by their husbands.

“The women decide to rent the land so that she may continue to produce food and feed the children. So, if she discovers the husband kept all the money, she looks for land to rent” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

Impacts of climate variability and change on food systems

“This lack of rain is affecting people’s livelihoods – no farming, no food, increasing diseases…children do not grow” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023).

“[Cyclone] Gombe destroyed everything. Both the wind and the water. After the storm everything stopped” (Man FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

Gendered differences in labour division, and access to land, resources and markets resulted in differential climate change impacts. Crop production was severely impacted by extreme weather, which highly affected the women of the settlements who were primarily responsible for cultivating the land. Despite the heavy impacts of climate change on agricultural production, limited climate adaptation or mitigation mechanisms existed in either settlement. While some (men and women) had been trained on extreme weather emergency responses, the women felt that they had limited knowledge regarding climate change responses. “There is no training on climate change. No information on climate change. There are no early warning systems” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

The changes in rainfall made the land difficult to cultivate and limited options for irrigation existed. Climatic changes also resulted in increased pests, which was a common problem in both settlements. In MRS, the women explained how the purchasing and usage of pesticides on the crops fell within the responsibility of the man due to differences in market access. While the limited crop yields as a result of extreme weather events affected food security for all, it was evident that men and women faced differing social consequences of food insecurity. Due to limited alternative livelihood opportunities for women, lacking yields and damaged crops led women in both settlements to engage in harmful coping mechanisms such as survival sex. In the face of drought, one woman explained “When there is no water, there is no food, so people turn to prostitution” (Woman FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023). Participants in both settlements explained how when food was scarce, survival sex persisted as a common coping mechanism for women, particularly exchanges between displaced women and the host community men.

On the other hand, women’s central role in maintaining food and water security as well as securing the household made them particularly key in disaster risk reduction as their knowledge helped ensure that the household was secure ahead of extreme weather events. “During disasters, the women try to get water inside their houses because water resources will be destroyed, so they make sure they have water, wood, charcoal and food storage” (Man FGD participant, MRS, Dec 2023). This became evident during the research as once the wind picked up, the women requested time off to secure the household ahead of a potential storm, while the men did not. Although climatic hazards have always existed, the community noted an increase in extreme weather events.

Gender biases in humanitarian responses

Aid interacts with the local food system in multifaceted ways. In both settlements, aid was highly gendered. Women were primarily responsible for collecting food aid for their households in both settlements. In the studied context, while attempts to equalise gendered power relations benefited food security and household spending power by female household members, the context also exacerbated sentiments of lost masculinity amongst male household members due to limited breadwinning opportunities and access to aid. This structure challenged traditional gender roles and expectations, with social security concerns rising in response, particularly male-to-female gender-based violence (GBV). The women in CIS explain:

“Here in this camp, there are no specific rights for men. Because when they came, the responsibility of the family for the entire process is the name of the women. The woman is the leader of all processes in the camp officially. Culturally the head of the family is the man but, in the camp, this is the women. The ones who can go to get support is the woman not the man. The man should follow his wife” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

“The men are not comfortable. They are always complaining that you women are leading the process. Sometimes they say that if something wrong happens to you it is up to you to sort it out. It provoked a lot of conflict, in other families they used to fight physically against each other and sometimes when the wife is not around the man takes the food that she received as support and sells it to host communities. The money he keeps. Part of this behaviour is because they are somehow frustrated because in their homeland they used to do business. Here there is nothing for them, so they are dependent” (Woman FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

The limited aid provision for men in the settlements coupled with few livelihood generating opportunities meant that some men were forced to turn to dangerous coping mechanisms. While these included violent acts against female household members, many also resulted to other mechanisms such as returning to areas of conflict. The men in CIS reported that the severe food insecurity had forced some men to travel back to Cabo Delgado to fish. They explained how “others prefer to die in Cabo Delgado as long as they can farm and fish…They stay for a few months and then come back. They come back with a lot of money, but it’s very dangerous. Many have gone to do this and been killed in Cabo Delgado” (Man FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023). For those staying in CIS, while men were largely excluded from directly receiving aid, they were more likely to receive work through international organisations. Although some labour opportunities were provided to women, it was evident from both genders that the majority of (the limited), labour opportunities went to men. However, this was not perceived by the women in this study as unfair, rather, many of the women expressed frustrations over the limited opportunities provided to the men in the settlements and the high nepotism rates, which limited opportunities to a lucky few. The men in CIS expressed high reliance on projects from international organisations explaining that, “our life was to sit and wait, just depending on projects” (Man FGD participant, CIS, Dec 2023).

Additionally, the high reliance on foreign aid in the settlements meant that, despite the team clearly communicating research intent only, showcasing vulnerability was a clear coping mechanism within both settlements. While the focus groups in CIS were more inclined to showcase resilience, likely due to many stating a wish to stay permanently, the refugee women in MRS explicitly told the research team that showcasing resilience would prove a significant barrier to them, as perceived resilience and integration would limit opportunities for resettlement elsewhere.

Discussion

At the intersection of gender and displacement, opportunities and barriers within food systems are formed. While the displacement context generates multifaceted challenges, including lack of access to land, natural resources and high climate change vulnerability, these challenges do not impact everyone equally. A significant finding from this paper is the differential impacts of food system disruptions on gender. Discussions with displaced communities revealed that limited access to land and insecure tenure agreements heightened vulnerabilities in both settlements. These challenges were accompanied by distinct gender-related consequences, including disparities in labour linked to food production, incidences of GBV and varying degrees of food insecurity.

Although limited land access poses a significant hurdle for all displaced individuals, its impact is distinctly gendered. Echoing the general trends in Africa, women in the studied sites played a crucial role in the agri-food sector (Bryan et al., 2023; Djoudi and Brockhaus, 2011; FAO, 2023c; Rao et al., 2019a). However, our research highlights a critical divergence: despite this active involvement, persistent socio-cultural and structural factors in Mozambique significantly impede women’s ability to translate their labour into profit and build resilience. This resonates with studies highlighting the unrecognised and informal nature of women-dominated sectors like small-scale agriculture and domestic labour (de Brauw, 2014; Johnston et al., 2015; Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action, 2022). The study argues that the continued invisibility of women’s contributions, despite governmental attempts at legislative reform regarding land acquisition (Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action, 2022), reveals a critical gap between policy and practice, ultimately exacerbating land insecurity for women, a challenge compounded by its limited accessibility of land for displaced communities (Vos et al., 2020). Additionally, climate change acts as a significant external stressor, exacerbating existing vulnerabilities within food systems and disproportionately affecting displaced communities who often have limited adaptive capacity.

In the absence of land and natural resources, formal employment and wider market access is key for economic resilience, yet globally, forced displacement settlements provide significant barriers for people to seek formal employment, due to issues such as national restrictions on freedom of movement, rights to employment and insufficient documentation (Fasani et al., 2021; Fincham, 2012; Wesley Bonet, 2021). While there is full freedom of movement for refugee and IDP populations in Mozambique (UNHCR, 2010), people living in displacement settlements face a multitude of barriers to movement, including poor infrastructure and socio-economic conditions, largely confining them to hyper-local opportunities and food-value chains. Gendered differences in wider, urban market access were evident, largely shaped through time-consuming expectations of domestic labour placed on women. This, coupled with great travel distances and poor infrastructure led to the consequential prioritisation of men for urban access. This observation aligns with findings from other camp settings (Johnston et al., 2015; Komatsu et al., 2015; Logie et al., 2022; Rao et al., 2019a,b), suggesting a systemic pattern where women’s unrecognized domestic burdens directly undermine their economic opportunities. Furthermore, the predominantly informal nature of labour in these contexts limits women’s access to crucial social protection mechanisms like childcare and reproductive health support (Gammage et al., 2019; Logie et al., 2024; Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action, 2022), further entrenching their confinement to less resilient, hyper-local food chains. The geographical proximity to Nampula City influenced resilience capacities in both sites. For example, the closer location of MRS to Nampula City and better access to transport facilitated improved market access for food system inputs and opportunities for selling outputs, thereby enhancing resilience for all genders and the broader food system. In contrast, Corrane’s remote location, coupled with poorly maintained roads, restricted market access - particularly for women - undermining individual and systemic resilience. Strengthening market access could thus play a crucial role in fostering resilience across gender lines.

Interestingly, the study also reveals that displaced men face significant limitations in accessing diverse livelihood opportunities, challenging a potentially gender-blind approach to displacement challenges. The inability to pursue traditional livelihoods such as charcoal production and fishing due to resource ownership by host communities and settlement location, created considerable economic strain. Fishing is a common livelihood for both men and women in Mozambique (Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action, 2022; Sturridge et al., 2022), but the settlements were situated far from the sea, proving a significant barrier of access to this resource. In the absence of opportunities within and surrounding the settlements, many of the men resorted to extreme coping mechanisms, such as returning to areas affected by conflict, to secure a livelihood. The cultural expectation for men to provide economic security for their households added substantial pressure to secure employment. While this expectation afforded men certain advantages, such as being prioritised for project employment and gaining access to markets, it also created a dichotomic reality, of upholding cultural expectations of the man as the breadwinner within a context with little to no opportunities to fulfil such expectations.

There is increasing recognition of the need to look at relations within the field of gender studies (Dunn and Matthew, 2015; FAO, 2023c; Rao et al., 2019a; Smith, 2022). In times of disaster, a common notion has been that gender relations may shift, where power is altered by women becoming de facto heads of households (Djoudi and Brockhaus, 2011; Hans et al., 2021; Smith, 2022). However, it seems that rather than induce equity, many of these contexts undermine female power and security. For example, when we look at food systems in displacement contexts, foreign humanitarian intervention is a common reality. Intervention in a complex system does not result in linear outcomes, rather, there is a need to consider the specific contextual relations that make these systems peaceful (or not) and sustainable (or not) (de Coning, 2016). It was evident in the studied settlements that despite humanitarian organisations attempting to equalise gendered power by primarily providing women with aid, the man remained the head of the household and even exerted violence to maintain this position. This finding is in line with the common critique of resilience, that resilience for one may undermine resilience for another (Chelleri et al., 2015; Mahdiani and Ungar, 2021). While this is a common environmentalist critique, it applies in the field of gender studies, highlighting the need to understand the relational gendered consequences of resilience building. Considering the foregoing, this paper recommends the crucial need to bridge the humanitarian-development divide when offering assistance in displacement settings. There is a need to shift from a model reliant solely on humanitarian aid to development-focused initiatives that promote individual and system self-reliance and strengthen the long-term resilience of local communities and food systems to address the gendered challenges. This transition should be implemented carefully to preserve social cohesion and foster solidarity within the community.

In the studied contexts, sentiments of lost masculinity with limited opportunities for breadwinning led men in both settlements to re-enforce their positions of power within the domestic sphere through financial and sometimes physical control, generating a power dynamic which exacerbated cases of GBV. That is not to say that targeting women for aid did not increase women’s financial autonomy and security; rather, there is a need to look at the relational consequences of such efforts to improve security and equity outcomes for all genders. Therefore, in advancing gender equity and the transformation of sustainable food systems, it is essential to approach gender resilience not as an isolated concept but as an integral component of the broader food system. This requires situating it within the wider societal structural dynamics that shape gender relations. Consequently, gender studies should focus on understanding the interconnectedness of gender relations rather than treating them as individualistic and separate experiences. As such, this study is not conclusive on how interventions impact wider food systems and security; instead, it points to the importance of further research to unpack these non-linear gender relational consequences.

Conclusion

Within displacement contexts, food systems are shaped through multifaceted social and ecological factors that govern the settlements and their respective host communities. These systems are highly volatile, due to pressures such as conflicts over land, increasing climatic hazards and limited livelihood opportunities. Gender plays a crucial role in determining individual capacities for resilience within these contexts. The pivotal role of displaced women in upholding food security within settlements, particularly within the agri-food sector and food processing, remains largely unrecognised. Women encounter substantial barriers to resilience, including challenges in accessing land for cultivation, limited access to wider market participation and insufficient financial capital to invest in sectoral improvement and climate adaptation. Similarly, displaced men encounter multifaceted challenges in finding formal employment or resource access. While they showcase resilience through leveraging social networks for livelihood options such as fishing, barriers persist, including great travel distances and poor infrastructure, hindering access to natural resources beyond the settlement.

These gender dynamics reveal how men and women are affected differently by structural and cultural power relations and barriers but also how these dynamics interlink and relate to one another. These findings point to the ongoing need to include displaced communities in decision-making processes, with particular attention to women who remain largely excluded from the peace and security agenda unless victimised (Dunn and Matthew, 2015; Henry, 2017, 2021; Smith, 2022). It is important to note that while this study aimed to front local perspectives, local voices are ultimately not given the same recognition due to a need for anonymity within the study. Therefore, continued local integration and representation are needed to address such gaps and prevent the marginalization of local, especially Global South dynamics in favour of Western notions of gender transformation and ‘development.’ In striving to bolster resilience within displacement-affected food systems, it is essential to consider the gender dynamics and relations that shape roles and experiences within these systems. A nuanced and inclusive understanding of these dynamics facilitates targeted interventions, improving security, equity and resilience for all genders.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset contains information that may identify participants and lead to social protection concerns due to the vulnerable context in which this study was conducted. Requests for data access will be considered on a case-by-case basis. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dGhlYS5zeW5uZXN0dmVkdEBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ== or Zy5tYXZpemFAY2dpYXIub3Jn.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Alliance of Biodiversity International and the International Centre For Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was authorised under clearance number 2023-IRB72. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Verbal informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

TS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. GM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article was funded by the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders/.

Acknowledgments

This work is carried out with support from the CGIAR Climate Action Science Program (CASP) and the CGIAR Food Frontiers and Security (FFS) Science Program. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders/. We acknowledge and thank Anne Mette Lykke at Aarhus University, who was the supervisor for the MSc thesis on which this paper is based. We would also like to thank Jonathan Tsoka and Richard Holden for their work in creating the map used in this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel, R. S. B., Hadia, A. M. D., and Mirza, B. B. (2014). Coping strategies of Darfurians displaced women in Khartoum. J. Agric. Extens. Rural Dev. 6, 168–174. doi: 10.5897/JAERD2013.0553

ACLED (2024), Cabo Ligado Update: 15-28 April 2024 (Cabo Ligado, 2024; pubd online May 2024). Available online at: https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-update-15-28-april-2024 (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Anwar, N. H., Sawas, A., and Mustafa, D. (2019). Without water, there is no life: negotiating everyday risks and gendered insecurities in Karachi’s informal settlements. Urban Stud. 57, 1320–1337. doi: 10.1177/0042098019834160

Arhin, P., Erdiaw-Kwasie, M. O., and Abunyewah, M. (2022). Displacements and livelihood resilience in Ghana’s mining sector: the moderating role of coping behaviour. Resources Policy 78:102820. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102820

Bates, L. (2016). Everyday sexism. The Project That Inspired a Worldwide Movement. New York: A Thomas Dunne Book for St. Martin’s Griffin.

Bellino, M. J. (2018). Youth aspirations in Kakuma refugee camp: education as a means for social, spatial, and economic (im)mobility. Glob. Soc. Educ. 16, 541–556. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2018.1512049

Bryan, E., Ringler, C., and Meinzen-Dick, R. (2023). “Gender, resilience, and food systems” in Resilience and food security in a food systems context. Eds. C. Béné and S. Devereux (New York: Cornell University), 239–280.

Bunce, A., and Ford, J. (2015). How is adaptation, resilience, and vulnerability research engaging with gender? Environ. Res. Lett. 10:123003. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/123003

Carr, E. R., and Thompson, M. C. (2014). Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings: current thinking, new directions, and research Frontiers. Geogr. Compass 8, 182–197. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12121

Chelleri, L., Waters, J. J., Olazabal, M., and Minucci, G. (2015). Resilience trade-offs: addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environ. Urban. 27, 181–198. doi: 10.1177/0956247814550780

Choudhary, N., and Parthasarathy, D. (2007). Gender, work and household food security. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 43, 523–531. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i402044

Conca, K. (2024). Environmental peacebuilding: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. J. Soc. Encount. 8, 4–12. doi: 10.69755/2995-2212.1236

Constitution of The Republic of Mozambique (2018) Available online at: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/moz117331POR.pdf (Accessed January 18, 2024).

Crush, J. (2013). Linking food security, migration and development. Int. Migr. 51, 61–75. doi: 10.1111/imig.12097

de Brauw, A. (2014). Gender, control, and crop choice in northern Mozambique. Agric. Econ. 46, 435–448. doi: 10.1111/agec.12172

de Coning, C. (2016). From peacebuilding to sustaining peace: implications of complexity for resilience and sustainability. Resilience 4, 166–181. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2016.1153773

Dickin, S., Segnestam, L., and Sou Dakouré, M. (2020). Women’s vulnerability to climate-related risks to household water security in Centre-East, Burkina Faso. Climate Dev. 13, 443–453. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2020.1790335

Djoudi, H., and Brockhaus, M. (2011). Is adaptation to climate change gender neutral? Lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali. Int. For. Rev. 13, 123–135. doi: 10.1505/146554811797406606

Doocy, S., Sirois, A., Anderson, J., Tileva, M., Biermann, E., Storey, J. D., et al. (2011). Food security and humanitarian assistance among displaced Iraqi populations in Jordan and Syria. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.023

Dunn, H., and Matthew, R. (2015). Natural resources and gender in conflict settings. Peace Rev. 27/2, 156–164. doi: 10.1080/10402659.2015.1037619

FAO (2008). An introduction to the basic concepts of food security. Practical guides (the food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/3/al936e/al936e00.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2024).

FAO (2018). Sustainable food systems concept and framework (the food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b620989c-407b-4caf-a152-f790f55fec71/content (Accessed May 12, 2024).

FAO (2021). Mozambique agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19 monitoring report august 2021 (the food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/ec8b7c10-80e2-4edf-91ab-72e3a39197eb/content (Accessed March 15, 2024).

FAO (2023a). Developing sustainable and resilient agrifood value chains in conflict-prone and conflict-affected contexts (Cairo, Egypt; pubs online 2023). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc6662en (Accessed January 17, 2024).

FAO (2023b). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023 (Rome, Italy) Available online at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc3017en (Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

FAO (2023c). The status of women in Agrifood systems (food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/3/CC5060EN/online/status-women-agrifood-systems-2023/chapter1.html (Accessed March 14, 2024).

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., and Minale, L. (2021). (the struggle for) refugee integration into the labour market: evidence from Europe. J. Econ. Geogr. 22, 351–393. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbab011

Fincham, K. (2012). Learning the nation in exile: constructing youth identities, belonging and ‘citizenship’ in Palestinian refugee camps in South Lebanon. Comp. Educ. 48, 119–133. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2011.637767

Gammage, S., Sultana, N., and Glinski, A. (2019). Reducing vulnerable employment: is there a role for reproductive health, social protection, and labor market policy? Fem. Econ. 26, 121–153. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2019.1670350

Garmezy, N., and Masten, A. S. (1986). Stress, competence, and resilience: common frontiers for therapists and psychopathologist. Behav. Ther. 17, 500–521. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(86)80091-0

George, J., and Adelaja, A. (2022). Armed conflicts forced displacement and food security in host communities. World Dev. 158:105991. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105991

Gibbs, G. R. (2007). Thematic coding and categorizing. Analyzing qualitative data 703, 38–56. doi: 10.4135/9781849208574

Gibson, C. C., Andersson, K. P., Ostrom, E., and Shivakumar, S. (2005). The Samaritan’s dilemma: The political economy of development aid. Oxford University Press.

Gliessman, S. (2016). Transforming food systems with agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 40, 187–189. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2015.1130765

Hampshire, K., and Randall, S. (1999). Seasonal labour migration strategies in the Sahel: coping with poverty or optimising security? Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 5, 367–385. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199909/10)5:5<367::AID-IJPG154>3.0.CO;2-O

Hans, A., Rao, N., Prakash, A., and Patel, A. (2021). Engendering Climate Change. New York: Routledge.

Henry, M. (2017). Problematizing military masculinity, intersectionality andmale vulnerability in feminist critical military studies. Crit. Milit. Stud. 3, 82–199. doi: 10.1080/23337486.2017.1325140

Henry, M. (2021). On the necessity of critical race feminism for women, peace and security. Crit. Stud. Sec. 9, 1–5. doi: 10.1080/21624887.2021.1904191

Hirani, S., Lasiuk, G., and Hegadoren, K. (2016). The intersection of gender and resilience. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 23, 455–467. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12313

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

Horn, R. (2009). Coping with displacement: problems and responses in camps for the internally displaced in Kitgum, northern Uganda. Intervention 7, 110–129. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3283302714

Human Rights Watch. (2019). Mozambique: cyclone victims forced to trade sex for food. Human rights watch. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/04/25/mozambique-cyclone-victims-forced-trade-sex-food (Accessed April 16, 2024).

IDMC (2023). GRID 2023: internal displacement and food security (internal displacement monitoring Centre). Available online at: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2023/ (Accessed March 11, 2024).

IDMC (2024). 2024 global report on internal displacement (IDMC and NRC). Available online at: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2024/ (Accessed May 11, 2024).

IOM (2019). International migration law no. 34 - glossary on migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

IOM (2022). IOM Camp Coordination & Camp Management: Corrane site profile - Corrane Posto, Meconta District (international organisation for migration). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/iom-camp-coordination-camp-management-corrane-site-profile-corrane-posto-meconta-district-august-2022 (Accessed March 10, 2024).

IOM (2024a). Africa migration report (second edition) connecting the threads: linking policy, practice and the welfare of the African migrant (International Organization for Migration). Available online at: https://publications.iom.int/books/africa-migration-report-second-edition (Accessed March 10, 2024).

IOM (2024b). Mozambique — mobility tracking assessment report 20 (January 2024) (International Organization for Migration) Available online at: https://dtm.iom.int/reports/mozambique-mobility-tracking-assessment-report-20-january-2024 (Accessed May 10, 2024).

IPCC (2023). Climate change 2023 synthesis report: Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Jacobs, C., and Almeida, B. (2020). Land and climate change: Rights and environmental displacement in Mozambique. Mozambique: Van Vollenhoven Institute for Law.

Johnston, D., Stevano, S., Malapit, H., Hull, E., and Kadiyala, S. (2015). Agriculture, gendered time use, and nutritional outcomes: a systematic review. The international food policy research institute (IFPRI), CGIAR research program on agriculture for nutrition and health. Available online at: https://www.ifpri.org/publication/agriculture-gendered-time-use-and-nutritional-outcomes-systematic-review (Accessed February 5, 2024).

Komatsu, H., Malapit, H. J. L., and Theis, S. (2015). How does women’s time in reproductive work and agriculture affect maternal and child nutrition? Evidence from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Mozambique, and Nepal. The international food policy research institute (IFPRI). Available online at: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/129842 (Accessed April 7, 2024).

Logie, C. H., MacKenzie, F., Malama, K., Lorimer, N., Lad, A., Zhao, M., et al. (2024). Sexual and reproductive health among forcibly displaced persons in urban environments in low and middle-income countries: scoping review findings. Reprod. Health 21:51. doi: 10.1186/s12978-024-01780-7

Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Coelho, M., Loutet, M. G., Narasimhan, M., Lukone, S. O., et al. (2022). Water insecurity and sexual and gender-based violence among refugee youth: qualitative insights from a humanitarian setting in Uganda. J. Water Sanit. Hygiene Dev. 12, 883–893. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihac065

Maereka, E. K., Nchanji, E. B., Nyamolo, V., Cosmas, L. K., and Chataika, B. Y. (2023). Women’s visibility and bargaining power in the common bean value chain in Mozambique. CABI Agric. Biosci. 4:56. doi: 10.1186/s43170-023-00197-9

Mahdiani, H., and Ungar, M. (2021). The dark side of resilience, adversity and resilience. Science 2, 147–155. doi: 10.1007/s42844-021-00031-z

Mahmood, S. (2001). Feminist theory, embodiment, and the docile agent: some reflections on the Egyptian Islamic revival. Cult. Anthropol. 16, 202–236. doi: 10.1525/CAN.2001.16.2.202

Maviza, G., Maphosa, M., Caroli, G., Synnestvedt, T., and Tarusarira, J. (2024). The complicated relationship between climate, conflict, and gender in Mozambique (Pubd online February 2024) Available online at: https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2024/02/the-complicated-relationship-between-climate-conflict-and-gender-in-mozambique/ (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Maxwell, J. (1998). Designing a Qualitative Study. In Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. Eds. L. Bickman and D. Rog (Los Angeles: SAGE). 69–100.

Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action (2022). Gender equality profile Mozambique. Mozambique: Ministry of Gender.

OCHA. (2023). Mozambique: tropical cyclone Freddy, floods and cholera - situation report no.1. UN Office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/mozambique-tropical-cyclone-freddy-floods-and-cholera-situation-report-no1 (Accessed March 02, 2024).

OCHA (2024). Mozambique: Cabo Delgado, Nampula & Niassa Humanitarian Snapshot - January 2024 (UN Office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/mozambique-cabo-delgado-nampula-niassa-humanitarian-snapshot-january-2024 (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Odiwuor, F.. (2022). Women smallholder farmers: what is the missing link for the food system in Africa? | Wilson Center Available online at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/women-smallholder-farmers (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Pingali, P., Alinovi, L., and Sutton, J. (2005). Food security in complex emergencies: enhancing food system resilience. Disasters 29, S5–S24. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00282.x

Queiroz, C., Norström, A. V., Downing, A., Harmáčková, Z. V., De Coning, C., Adams, V., et al. (2021). Investment in resilient food systems in the most vulnerable and fragile regions is critical. Nat. Food 2, 546–551. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00345-2

Quisumbing, A. T., and Doss, C. R. (2021). Gender in agriculture and food systems. Handb. Agric. Econ. 5, 4481–4549. doi: 10.1016/bs.hesagr.2021.10.009

Rao, N., Gazdar, H., Chanchani, D., and Ibrahim, M. (2019a). Women’s agricultural work and nutrition in South Asia: from pathways to a cross-disciplinary, grounded analytical framework. Food Policy 82, 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.014

Rao, N., Mishra, A., Prakash, A., Poonacha, P., Vincent, K., Singh, C., et al. (2019b). A qualitative comparative analysis of women’s agency and adaptive capacity in climate change hotspots in Asia and Africa. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 964–971. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0638-y

Sachs, C., and Patel-Campillo, A. (2014). Feminist food justice: crafting a new vision. Feminist Stud. 40, 396–410. doi: 10.1353/fem.2014.0008

Sassi, M. (2021). Coping strategies of food insecure households in conflict areas: the case of South Sudan. Sustain. For. 13:8615. doi: 10.3390/su13158615

Smith, E. (2022). Gender dimensions of climate security. SIPRI Insights Peace Sec. 1–31. doi: 10.55163/MSJJ1524

Sturridge, C., Feijó, J., and Tivane, N. (2022). Coping with the risks of conflict, climate and internal displacement in northern Mozambique. London: HPG case study.

Tendall, D. M., Joerin, J., Kopainsky, B., Edwards, P., Shreck, A., Le, Q. B., et al. (2015). Food system resilience: defining the concept. Glob. Food Sec. 6, 17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2015.08.001

Tschirley, D., Donovan, C., and Weber, M. T. (1996). Food aid and food markets: lessons from Mozambique. Food Policy 21, 189–209.

UNHCR (2010). Submission by the United Nations high commissioner for refugees for the Office of the High Commissioner for human rights’ compilation report. Universal periodic review: MOZAMBIQUE. UN high commissioner for refugees, human rights liaison unit division of international protection). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/lib-docs/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session10/MZ/UNHCR_UNHigh_Commissioner_for_Refugees_eng.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2024).

UNHCR (2023). Mid-year trends 2023. UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/mid-year-trends-report-2023 (Accessed March 10, 2024).

UNHCR (2024). UNHCR Mozambique: Operational Update January & February 2024. UN high commissioner for refugees. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/attachments/ad7a6d16-b63a-421f-8bfe-f8c647107b9c/UNHCR%20Mozambique%20OPERATIONAL%20UPDATE_JAN%20FEB%202024.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2024).