- 1Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Ben Guerir, Morocco

- 2Department of Business and Management, Guido Carli Free International University for Social Studies, Rome, Italy

Agriculture is an important component of the African economy, contributing to growth and employment. Still, African agriculture remains plagued by problems linked to limited modernization, low productivity, and an aging farmer population, and declining interest of young people. To remedy this situation, the AgriENGAGE project, a European Commission-funded initiative involving eight African and two European universities, seeks to improve agricultural education and stimulate entrepreneurship in African universities. Interviews and reports by these universities highlight the four essential elements: the need to find the right balance between theory and practice, the role of practical learning and incubation, the place of public support, and the need for industry involvement. Despite the efforts made, including AgriENGAGE, several problems persist, such as the limited space and economic literacy in the teaching community, the lack of resources and infrastructure, and the limited collaborations between academic institutions and industry.

1 Introduction

Agriculture employs more than a billion people worldwide, accounting for about 4.3% of the global GDP in 2021 (FAO, 2023). In Africa, in 2019, agriculture's contribution to GDP, at current market prices, was about 15.7%, slightly higher than the 14.1% registered in 2012 (African Development Bank, 2021). Notwithstanding the rapid structural transformations in African economies, the agricultural sector remains a cornerstone in most African countries, as it employed an estimated 48% of the workforce in 2021 (FAO, 2023; Davis et al., 2023), a decrease from the 1991–2000 decade's level of 58% (ILO, 2019). During the 2001–2021 period, the real value of agricultural production grew at an average pace of 4.6% per year, double the rate from 1970 to 2000. However, despite growth in agricultural production, the African continent is still lagging behind other regions in terms of agricultural productivity, as most of the increase comes from using more land (The Economist, 2018).

According to World Bank data, Africa is home to about 60% of the world's total uncultivated arable land (Ramutsindela and Mickler, 2020). However, this underutilization of land, combined with low productivity, is exacerbated by the fact that around 93% of cultivated land depends on rainfall and low fertilizer use (Alden, 2013). Furthermore, agriculture in Africa is characterized by limited mechanization and thus driven principally by human labor. Yet, despite the several challenges, including limited access to capital, technology, and the adverse effects of climate change, the sector remains pivotal for Africa's growth (Nkwabi and Mboya, 2019). Previous studies have suggested that embracing and supporting entrepreneurs holds significant potential to contribute toward unleashing the continent's agricultural potential by catalyzing increased productivity in the agricultural sector and, consequently, economic growth (Reardon et al., 2019). Despite several challenges, including limited access to capital, technology, and the adverse effects of climate change, the sector remains pivotal for Africa's growth (Nkwabi and Mboya, 2019; IBM, 2019).

Agro-entrepreneurial ventures are typically characterized by their ability to develop innovative (better) solutions at different nodes of agricultural value chains (i.e., upstream, midstream, and downstream). Previous estimates suggest that, in African agricultural value chains (VC), 40% of the value is created midstream in the VC and 20% downstream of the VC (AGRA, 2019). The farm-level output makes up the remaining 40%. This evidence underscores how the performance of the private sector in the midstream (logistics, processing, and wholesaling) and downstream (retailing and consumption) of Africa's value chains remains as important as farm performance in determining the food security of Africans (AGRA, 2019).

Therefore, entrepreneurship can foster value creation and supply chain improvements, offering greater market access and higher income for farmers in Africa. Peprah and Adekoya (2020) have indicated that fostering an entrepreneurial ecosystem in agriculture should stimulate additional value creation, enhance food security, and reduce poverty levels across the continent.

The business landscape for agriculture in Africa has seen significant advancements recently, with rising opportunities characterized by higher—though more volatile prices—burgeoning urban food markets, and substantial opportunities for productivity enhancement. Although they remain geographically heterogeneous across Africa, foundational efforts to transition African agricultural systems toward more climate-smart agriculture set the stage for sustainable climate-resilient growth in this sector. The development of the private sector, combined with an improved policy environment and technological advancements, is streamlining reforms, enhancing information dissemination, and reducing operational costs. Therefore, supporting agricultural entrepreneurship through policies, investment, and education is essential for unlocking the productivity potential in Africa's agricultural sector (World Bank, 2013; World Bank Group, 2021).

Moreover, entrepreneurial orientation—innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking propensity constitute primary resources for the sector. Kangogo et al. (2021) suggest that policy development should consider the interplay between climate-smart agriculture practices and a conducive environment for farmer entrepreneurship.

Investments to nurture agricultural entrepreneurs occur through launching academic programmes (i.e., curriculum enhancement), enhancing intellectual property regulations and technology transfer policies, and strengthening technology commercialization models through business incubation parks and spin-off companies (Payumo et al., 2017; Osiru et al., 2012). For example, Mupfasoni et al. (2018) argue that the rising efforts in entrepreneurship research and education in Burundi in the agricultural sector can impact the economy at both micro and macro levels. Other studies on policy lessons point to education and capacity building as essential factors to increase agribusiness competitiveness in Africa and facilitate technical and entrepreneurial skill training (Babu and Shishodia, 2017; Cletzer et al., 2016).

The recent adoption of agri-entrepreneurship programs at the university level (Kashyap et al., 2022) is crucial for accelerating the transformation of the Agriculture sector through the implementation of new techniques and practices by entrepreneurs and industry leaders (Bairwa et al., 2014; Zaglul, 2016). Academic programs contribute significantly to informing agricultural practitioners and managers of decisions, developing farmers' knowledge and skills, and promoting the adoption of environmental sustainability principles (Singh, 2013). Agri-entrepreneurship education can also lead to the development of agricultural services that can contribute to increased productivity and profits for small farmers by connecting them to regional, national, and international markets, as well as accelerated growth and diversified incomes (Singh, 2013; Kadzamira et al., 2023).

Entrepreneurship and enterprise development programs can play a crucial role in Africa's economic growth and job creation, especially considering that about 10 to 12 million young people enter the African labor market yearly when only 3.1 million formal jobs are created (African Development Bank, 2016; Campbell, 2022; Oesch, 2006). Furthermore, from a food security angle, Africa's food import bill has increased from $7.9 billion during 1993–1995 to $43.6 billion during 2018. Recent forecasts for the region's imports are estimated to increase to USD 110 billion by 2030 (AGRA, 2022).

There has been growing political commitment across the African continent to engage youth in agribusiness and the agrifood sector, as in the Malabo Declaration, the African Union's Continental Agribusiness Strategy. For instance, Morocco's Green Generation 2020–2030 strategy is committed to creating a new generation of young entrepreneurs in the agriculture sector (Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries of Morocco, 2023) through actions focused on the development of human capital and the integration and proper positioning of the role of farmers in the commercial value chain, especially “midstream” (i.e., food processing, wholesale, and logistics) or “downstream” (i.e., retail and food service) (IFAD, 2016).

Similarly, Kenya developed a national programme to address challenges that hinder youth from participating effectively in the agricultural sector. The programme aimed to equip youth with appropriate agribusiness skills, knowledge, and information. Among the declared objectives, two stand out regarding access to modern technologies and the utilization of Good Agricultural Practices to increase efficiency and promote youth-inclusive climate-smart agricultural technologies, as outlined in the “Kenya Youth Agribusiness Strategy 2018–2022” (Ministry of Agriculture - Kenya, 2018).

1.1 Literature gap and research objectives

There is currently a worldwide interest in agricultural entrepreneurship and a recognition of its contribution in agricultural development (Franzel et al., 2023; World Bank, 2007), and the role that education and training can play in improving capacity, especially in Africa where the huge yield gap implies there is potential yield gains (Nin-Pratt et al., 2011; Van Ittersum et al., 2013). However there is significant lack of research and evidence-based reporting on existing models of university-industry collaboration in Africa. The benefits from such collaboration have already been underlined in previous studies (Sassi and Mshenga, 2025) that investigated the impacts on curriculum development, innovation and business and employment readiness. In addition, some relevant aspects, such as digital innovations, have suffered from their low integration into agricultural higher education, which is considered a contributing factor in their insufficient utilization (Engmann and Ngwakwe, 2024; Smidt and Jokonya, 2023).

Another under-explored aspect in existing research on agri-entrepreneurship education relates to the pedagogical and institutional elements of training programs (Osiru and Adipala, 2016). Despite existing research that shows that agri-entrepreneurship can play a significant role in job creation, food security and the modernization of value chain (Chirinda et al., 2024) there is a lack of information and analysis that looks into multiple institutional and national contexts, to juxtapose and compare the curriculum design, implementation strategies, and measurable outcomes of agri-entrepreneurship education and training programs [Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM), 2017]. This lack of evidence and perspective also limits our grasp regarding how universities can integrate other aspects such as indigenous knowledge, post-colonial education models, inclusive approach(es) and policy alignment (Omodan et al., 2024; Nigussie et al., 2024) and the expected outcomes in terms of entrepreneurship resilience.

The present study aims to fill a critical gap in existing literature. It provides a comparative, cross-country analysis of the operationalization of agri-entrepreneurship education by African universities. Whereas previous research focused on theoretical frameworks, on single-university or single-country case studies or on the presentation of projects' outcomes, this study adopts an appropriate framework for data collection and analysis from eight HEIs, to evidence-grounded conclusions on curricular development, University-Industry collaboration, and pedagogical innovation.

1.2 Research question

This paper seeks to address a little-studied and under-documented theme in African agricultural education: providing information on the practical arrangements that African universities are making to support agricultural innovation and youth agri-entrepreneurship. Specifically, the paper examines adjustments to agribusiness education, institutional arrangements, industry partnerships and community engagement.

1.3 Theoretical framework

Recent trends in entrepreneurship education emerged as a critical strategy for equipping graduates of African agriculture universities with the skills and competencies required to address pressing challenges in food security, rural livelihoods, and sustainable agricultural development. In this context, universities are increasingly recognized not only as knowledge producers but also as catalysts for entrepreneurial activity and socio-economic transformation, aligned with their evolving “third mission” of societal engagement (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 2000; Woldegiorgis and Doevenspeck, 2013).

The Triple Helix model (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 2000) provides a conceptual foundation for analyzing how agriculture universities in Africa can promote entrepreneurship by fostering dynamic interactions between academia, government, and industry. Such interactions are essential for creating innovation ecosystems that support the development of agribusiness ventures and rural entrepreneurship. More specifically the present study embraces the approach of “Mode 3 Knowledge Production System” (Carayannis et al., 2016) which offers a reflection on the increasing complexity, diversity, and interconnectivity of contemporary knowledge societies.

Early conceptualization of Triple Helix models focused solely on academic knowledge production (Mode 1) or applied, transdisciplinary approaches (Mode 2) (Gibbons et al., 1994). Mode 3 emphasizes the coexistence of diverse knowledge paradigms, stakeholder inclusion, and the cultivation of “creative knowledge environments”. It focuses on interaction of diverse actors, knowledge paradigms, and institutional logics for understanding how entrepreneurial learning in agriculture universities can be embedded within diverse, multi-actor knowledge environments.

In the African agricultural context, where systemic constraints such as resource scarcity, market fragmentation, and institutional gaps persist, entrepreneurship education can support on how to systematize opportunity recognition, experiment and practice innovation, among graduates.

By the adoption of Mode 3 Triple Helix framework this study aims to investigate how agriculture universities in Africa design and implement entrepreneurship education that contributes to sustainable agribusiness development and rural transformation (Mugimu, 2021).

2 Methodology

2.1 Research context: the AgriENGAGE project

The three-year Erasmus+ Capacity Building in Higher Education (CBHE) project (AgriENGAGE) was funded by the European Commission and implemented during 2020–2023. The project aimed to strengthen the capacity of higher education institutions (HEIs) to provide adequate training programs in agri-entrepreneurship and community engagement. Specifically, the project focused on developing the skills and competencies of university staff and students in agri-entrepreneurship and community engagement to catalyze the transformation of farming communities and the agri-industry. In that regard, AgriENGAGE is inspired by the crucial role that education can play in stimulating agricultural transformation and enhancing the sector's competitiveness while meeting job market demands.

A consortium of twelve universities collaborated in this project: Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II (IAV), Morocco; Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P), Morocco; Pwani University, Kenya; Egerton University, Kenya; University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), Benin; Université Nationale d'Agriculture (UNA), Benin; Gulu University, Uganda; Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda; Pavia University, Italy; and University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

2.2 Research design and data analysis

In this paper we built upon a unique project framework that involved eight universities from four countries (Kenya, Uganda, Morocco, and Benin), all participating in AgriENGAGE activities and outcomes. This set of universities, a sample of opportunity, has the advantage of representing varied approaches and assorted contexts. A semi-structured questionnaire was shared with project faculty from all universities. The questions involved a set of quantitative and qualitative -mostly open- questions, and covered a large set of questions that encompassed the following themes regarding agricultural education programs agri-entrepreneurial training and: (i) Current status and national alignment, (ii) Institutional strategies and challenges, (iii) Capacity for innovation and entrepreneurship, (iv) Monitoring and evaluation efforts, (v) Youth engagement, (vi) Role of external stakeholders, vii) Pedagogical approaches, (viii) Barriers and enabling factors, (ix) Institutional and community transformation. Collected responses were analyzed thematically, with emerging issues grouped under key categories such as institutional support, curricular balance, private sector engagement, and barriers to implementation.

The interview questions were systematically designed based on the Triple Helix Model. Questions related to curriculum design, entrepreneurial education, and graduate outcomes reflect the university dimension, focusing on how higher education institutions equip students with practical skills and an entrepreneurial mindset. The industry and entrepreneurial dimension is addressed through inquiries into the conditions for cultivating entrepreneurs, inventors, and scientists, as well as the barriers to agri-business development, thereby exploring university-industry linkages. Finally, the policy dimension was captured through questions examining the role of public authorities and external actors in supporting universities' efforts to promote agri-entrepreneurship and strengthen the broader enabling environment.

2.3 Findings

2.3.1 Highlights from the AgriENGAGE project

Regarding long-term education programs, AgriENGAGE helped review and upgrade existing undergraduate and graduate degree programs in all partner universities and develop new master's programs at UM6P and GULU University. In line with the objectives of AgriENGAGE, these new programs and modifications allowed the HEIs to respond to the growing need by the public and private sectors, as well as NGOs, for highly trained graduates in agribusiness. UM6P launched a Master of Agribusiness Innovation in October 2023 (UM6P - Master of Agribusiness Innovation, 2023), with 19 students in its first cohort, predominantly from Sub-Saharan Africa.

All African universities in the project developed new short-term training and education modules, specifically short modules dedicated to agribusiness innovation, directed at university staff and students. For example, in September 2023, UM6P conducted the “Agribusiness Innovation Masterclass” for PhD students (UM6P - Master of Agribusiness Innovation, 2023). In July 2022, UM6P also organized the Agri-entrepreneurship and Community Engagement Summer School, directed at students from all eight AgriENGAGE African universities (Ruforum-AgriENGAGE Summer School, 2023).

The project also provided valuable training workshops for faculty and staff from all partner universities. For example, the University of Copenhagen organized a “Workshop on Agri-Entrepreneurship Modules for African Universities” in January 2023, which provided the basis for developing the aforementioned short modules. Another training workshop at Pavia University focused on Industry-University collaboration in May 2023.

Regarding research output, the project generated two main bodies of research outputs. The first is case studies on local agribusinesses as a follow-up to the training by the University of Copenhagen team in March 2022 in Rabat, Morocco. For example, Lamdaghri et al. (2023) focused on the benefits of international collaboration during the AgriENGAGE project in promoting innovation and entrepreneurship in the two participating Moroccan Universities. Second, research articles based on the AgriENGAGE lessons learned and experiences, such as a perspective paper by Chirinda et al. (2024), where the authors link the successes and shortcomings of the AgriENGAGE to the more general framework and pertinent theories on the education of entrepreneurship, innovation, and community engagement in agriculture programs. As a follow-up, the authors of the present work aim to share the key insights on factors that determine the success of Agri-Entrepreneurship education in Africa.

The following section summarizes the experiences and lessons learned at the eight African partner universities that formed part of the AgriENGAGE project.

2.3.2 Key outcomes from the AgriENGAGE experience

AgriENGAGE at heart is an education-focused program where fruits usually take time to materialize. At its closure in January 2024, all project deliverables were deemed achieved, resulting in valuable interdisciplinary and multi-cultural experiences and important lessons learned, especially in capacity building and program review and design. One of the lessons learned in AgriENGAGE is through participants' exposure to a wide range of examples of agri-entrepreneurship education in Africa. This exposure is even more crucial given the little literature on the topic, which can be detrimental to governmental and industry involvement efforts and to funding prospects by international donors and research and development programs. In fact, the AgriENGAGE experience is worth an in-depth study to illustrate the collectively produced knowledge, the gained know-how, and transferable learnings of similar programs. Such a study would contribute to filling the knowledge gap on agri-entrepreneurship education in Africa, as well as its challenges, impact, and effectiveness.

All African partner universities were invited to answer a comprehensive list of questions about their agri-entrepreneurship programs and AgriENGAGE experience in their respective institutions (See Annex A). These questions aimed to tease out their insights regarding curriculum composition, agri-entrepreneurship initiatives, government and industry support, AgriENGAGE short and long-term outcomes, barriers and challenges, and other lessons from their AgriENGAGE journey.

The answers by the AgriENGAGE partners highlight four dimensions that shape the success of Agri-Entrepreneurship education in their experience-informed opinions on the four dimensions opinion, as follows: (1) Balancing theory vs. practice, (2) enhancing practical learning and incubation, (3) government support, and 4) industry involvement.

The following sections present details on the four highlighted dimensions.

1) Balancing theory vs. practice

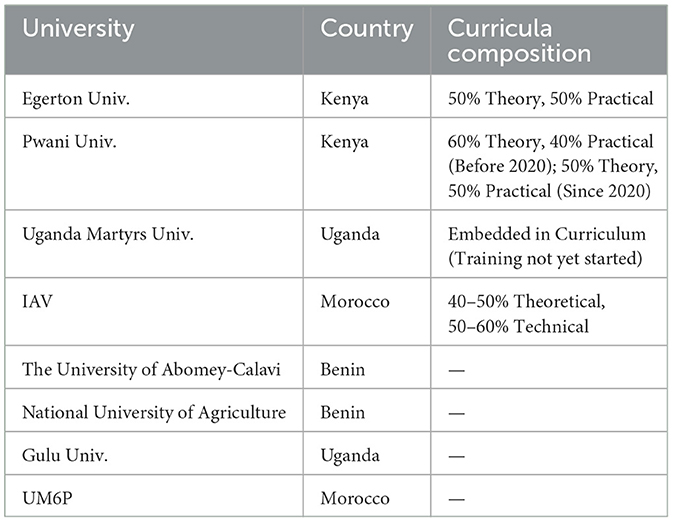

The universities' answers depict a mixed outcome regarding the evolution of the balance of theoretical training with practical and technical teaching related to agriculture and its industries in recent years. All participant universities demonstrated a high awareness of the importance of practical learning, as evidenced by their curricula revisions aimed at enhancing the graduates' and up to 60% in IAV in Morocco, as reported in Table 1. Other universities reported a different picture, such as UMU, where practical training is reportedly embedded in the curriculum, but actual training has not started yet.

2) Entrepreneurial learning, innovation, and incubation

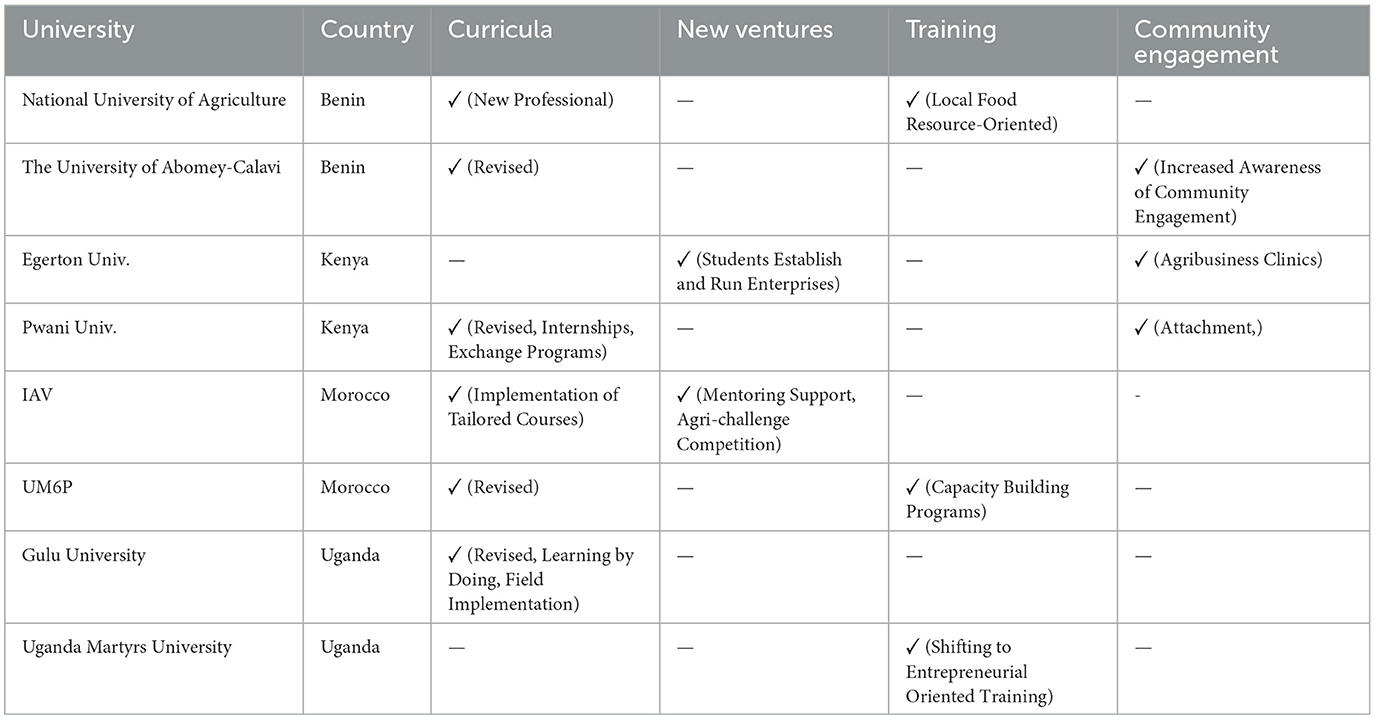

All participant universities showed high awareness of the importance of practical learning as they have all made curricula revisions to enhance the graduate's agri-entrepreneurship education and community engagement skills.

The different universities provided a wealth of diversity in the proposed practical learning interventions, including “Learning by Doing” and “Field Implementation” at Gulu University, as presented in Table 2. More practical learning was brought through innovative programs as UMU adopted entrepreneurial-oriented training. At the same time, UM6P introduced a new Master's program in Agribusiness Innovation and developed a new capacity-building program to promote Agri-entrepreneurship and community engagement. UM6P researchers and students can prototype and test their solutions on the university's Experimental Farm and apply for funds to UM6P Filia, UM6P Ventures, which invests in students' and researchers' startups.

At Egerton University, as part of the Masters in Agrienterprise Development, students are trained to establish and run their enterprises for grades. In Morocco, IAV teamed up with UM6P to provide mentoring support to 120 students to establish new ventures through Agrichallenge competitions.

All participant universities report that the main challenges encountered in implementing agri-entrepreneurship in the curriculum are the lack of adequately trained teachers, as highlighted by UMU and UAC. UAC also mentions the need for post-training follow-up. One of Gulu University's main challenges is the limited resources for field and practical courses, as well as the difficulty in engaging with the industry and the private sector, particularly in securing guest lecturers, mentors, and coaches. Another challenge is securing funding to establish incubation hubs, where students can launch their agri-enterprises and validate the feasibility of their business ideas (UAC Startup Valley, 2023). These hubs can be linked to industry and the private sector to scale them up.

Egerton highlights the lack of resources for monitoring and mentorship at incubation centers. Most universities highlighted funding limitations, including for facilities and seed funding.

3) Government support

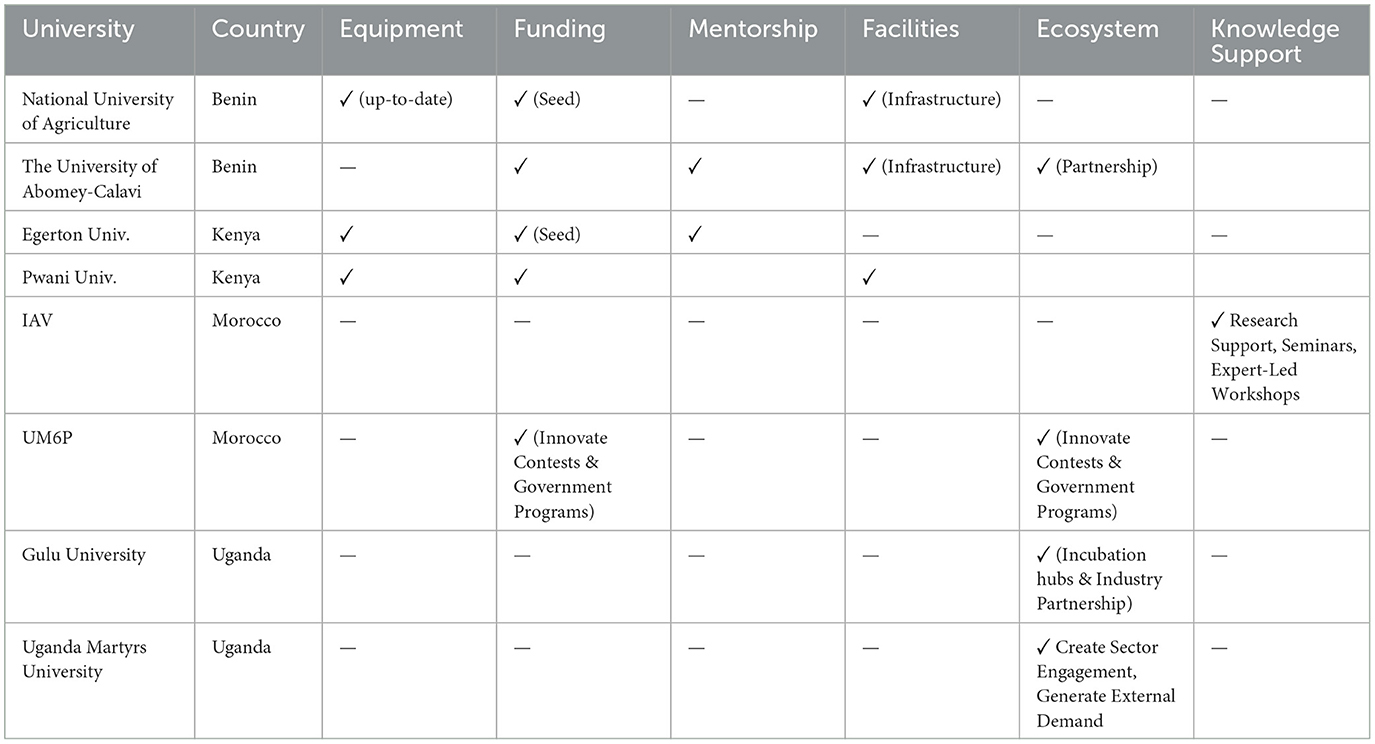

All universities agreed on the significant role that the government and outside groups can play in supporting efforts to integrate agri-entrepreneurship into agriculture education and make it more effective (Poulton and Macartney, 2012). Table 3 shows that their answers can be grouped into two main types: material support in terms of equipment, funding, and facilities, and soft support, including student mentorship, knowledge and ecosystem support.

For instance, Pwani University and NUA mentioned the need for equipment support, while Egerton stressed the need for prototyping equipment. Most universities prioritized financial support. Pwani and UAC highlighted financial support through scholarships or grants for agri-entrepreneurship students, while Egorton and NUA mentioned seed funding for student entrepreneurs. In comparison, UM6P favored special funding programs to sustain the project's deliverables, such as the agrifood tech incubators and agri challenge.

Pawni brought up the importance of facilities, while Gulu favored support for establishing incubation hubs. Both Benin partner universities, NUA and UAC, emphasized the need for infrastructure to support practicals in agriculture. Egerton and UAC highlighted the importance of mentorship and coaching programs by successful agri-entrepreneurs to share their knowledge and experience with students and guide them in developing their projects.

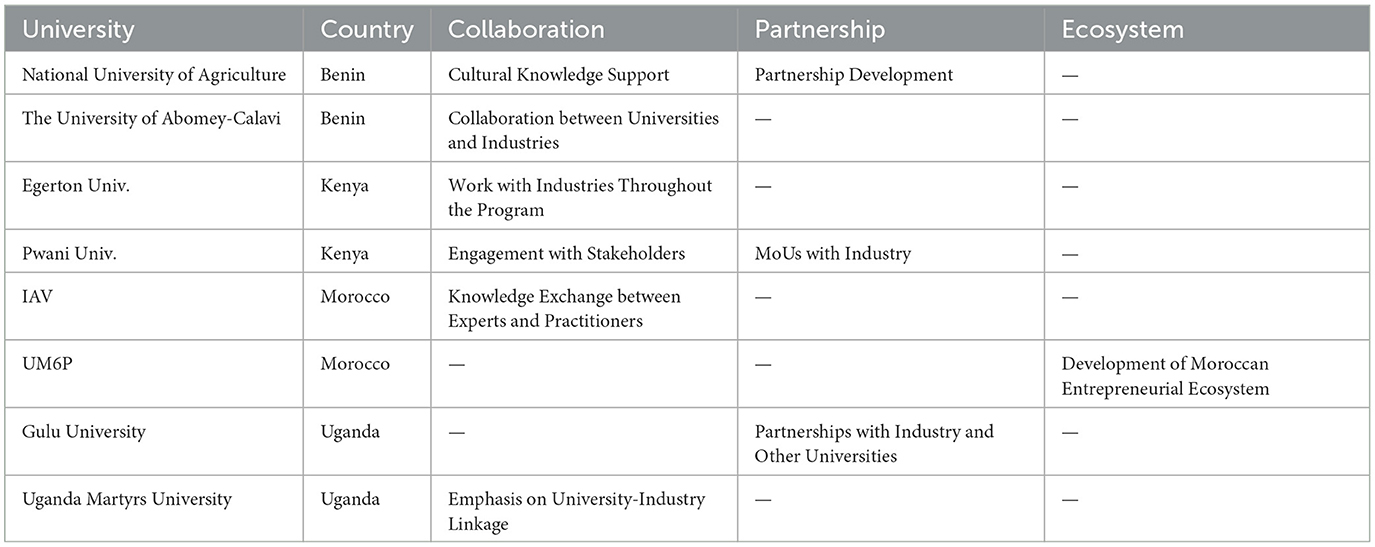

4) Industry involvement

Most universities leverage their education and research activities to contribute to engage with the community and collaborate with the ecosystem (Osiru et al., 2012), as presented in Table 4. Some direct examples are Benin's UAC program to increase awareness of community engagement and Egerton's investment in Agribusiness Clinics to benefit farmers and enterprises.

Another direct contribution by Pwani University is the project “Institutionalization of Field Schools” in collaboration with FAO, which contributed to the training of (20) University staff members, certified as Field Schools Master Trainers to increase inclusiveness, participation, and ownership of agricultural knowledge generation and dissemination among farmers. UMU distance learning courses and weekend programs for mid-career agriculturalists offer a flexible learning opportunity for non-working students.

IAV organized seminars led by experts on the main aspects of entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector, presenting real success cases and preparing graduates to meet the industry's needs. Collaboration with the ecosystem involves conducting relevant research programs to modernize agriculture and meet the evolving expectations and needs of farmers and the industry.

Egerton University's agricultural education curriculum is aligned with local needs in the production sector, but the gap persists in management, entrepreneurship, and value addition. All the agriculture and environment faculty programs in Gulu align with the country's national development priorities. At Pwani University, the research targets the areas of animal and crop production and agribusiness to better serve the community and industry in the coastal regions and other areas of Kenya, with sought-after outputs.

Agricultural research conducted by AUC researchers at the Faculty of Agronomic Sciences aims to meet the local community's needs and contribute to the sustainable development of agriculture in Benin. It also aims to solve the specific problems facing Benin's farmers and to improve their productivity, resilience, and wellbeing. Researchers collaborate with local farming organizations and government institutions to increase the adoption of research findings in rural development programs and agricultural policies.

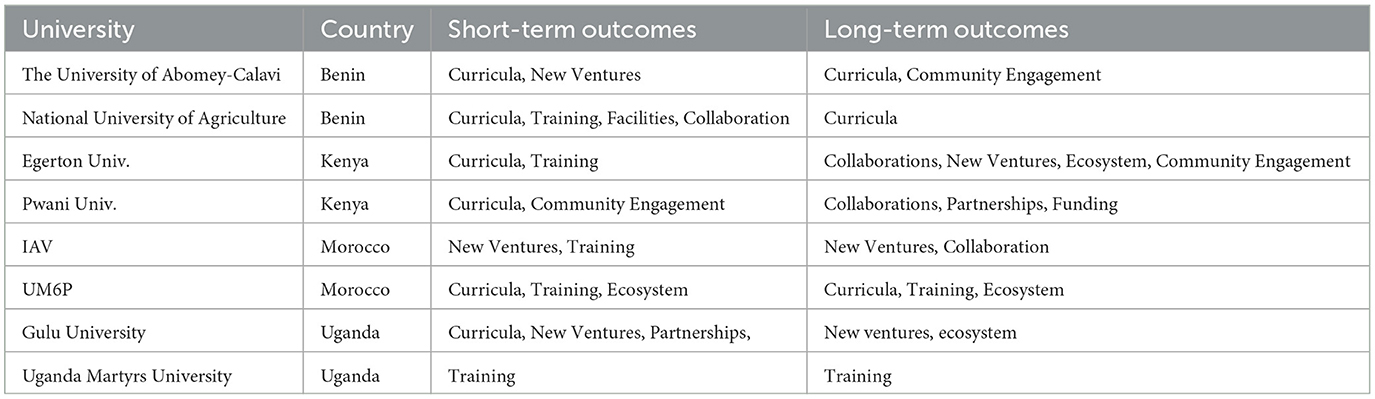

In summary, upgrading curricula is the key common short-term AgriEngage outcome highlighted by the partners, while developing new ventures and the ecosystem through partnerships or community engagement are the key common long-term outcomes of the project as illustrated in Table 5.

3 Discussion and conclusion

The results from the AgriENGAGE project offer an in-depth perspective of the Mode 3 Knowledge Production System (Carayannis et al., 2016) within African higher education institutions. The project demonstrated how universities can simultaneously act as knowledge producers, application hubs, and innovation catalysts by embedding entrepreneurial learning and community engagement into their academic structures. For instance, the integration of incubation programs, industry mentorship, and field-based experiential learning across eight African universities illustrates the formation of creative knowledge environments that bridge teaching, research, and socio-economic impact. These initiatives align with the third mission of universities which is to generate economic and social value—not only through graduate employability and startup support but also through institutional partnerships with government and industry stakeholders. AgriENGAGE's structured collaborations, curriculum reform, and ecosystem-building activities thus reflect Mode 3 processes, where policy-driven top-down reforms (e.g., Green Generation in Morocco or Kenya's Agribusiness Strategy) intersect with bottom-up innovations in teaching and student-led ventures. These dynamics underscore the evolving role of HEIs in Africa as multi-functional agents in regional development and knowledge co-production.

These results complement the analysis carried out by national and international reports indicating that some of the most recurrent challenges facing farmers in African countries are related to a lack of access to credit, a lack of training in financial literacy, and lack of market access (Hruby and Mengoub, 2023). Other mentioned challenges include climate change and the lack of infrastructure for agribusiness industries, as described by the World Bank Climate Change Action Plan 2022–2025 (World Bank Group, 2021; Kadzamira et al., 2023). Looking at these challenges through the lens of the Mode 3 Triple Helix model offers a fresh perspective onto developing the agricultural sector with positive ripple effects on the rest of the economy, improving food security and employment creation (Munang and Andrews, 2014; Hruby and Mengoub, 2023; Odularu, 2023). Reinforcing the entrepreneurial contribution to the agricultural sector is expected to address many of the aforementioned challenges (Reardon et al., 2019).

Entrepreneurship education is a critical driver to enhance entrepreneurial understanding among students, policymakers, and the general community (Hytti and O'Gorman, 2004). Supporting the development of entrepreneurial attitudes, skills, and competencies among African university students is challenging (Mbeteh and Pellegrini, 2022; Tulu, 2017) and requires a contextualized framework for entrepreneurship education. AgriENGAGE partners' emphasized the importance of balancing theory and practice, entrepreneurial learning and incubation in the educational design. These results align with entrepreneurship-driving education factors, including entrepreneurial motivations, opportunity recognition, understanding the global environment, and carrying the business idea (Shane et al., 2003).

A university's entrepreneurial education must be part of a broader entrepreneurial ecosystem that includes communities, social structures, institutions, and cultural values (Roundy et al., 2017; Polanyi, 1944; Oesch, 2006). The key outcomes from AgriENGAGE partners' feedback, particularly government support and industry involvement, confirm the importance of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the role of human, structural, and relational capital in enhancing entrepreneurial university posture (Lombardi et al., 2018).

Finally, the AgriENGAGE experiences show the importance of providing necessary resources, either internally or through external project funding, to integrate entrepreneurship across university education successfully. This paper aims to synthesize some of the main experiences gained by eight African universities about integrating entrepreneurship into agricultural education.

The main lessons that emerged from the AgriENGAGE experience are the importance of (i) developing the ecosystem in the African continent where youth create and develop innovative enterprises, (ii) networking and collaboration(s) among scholars and educators across Africa, and (iii) sustainability in funding of entrepreneurship programs to give their full transformative effects. These outcomes need to be carefully considered when designing university interventions in HEIs to ensure their effectiveness in achieving the desired objectives; they also need to be taken into account by policymakers to devise better support for universities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude and thank all the universities participating in the AgriENGAGE project that supported this research. Special thanks go to Prof. Achille E. Assogbadjo, Prof. Flora Josiane Chadare, Prof. Basil Mugonola, Prof. Elisha Otieno Gogo, Prof. Patience Mlongo Mshenga, Prof. Kenza Aitelkadi, Prof. Joseph Ssekandi, and Prof. Anthony Egeru for facilitating access to responses from the African universities involved in the project. We also thank Prof. Carsten Nico Hjortsø and Prof. Maria Sassi for their constructive feedback on the questionnaire. We extend our gratitude to the editor and three reviewers for their relevant and constructive comments on our manuscript, which have undoubtedly strengthened this work. All remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

African Development Bank (2016). Catalyzing youth opportunity across Africa. Jobs for Youth in Africa. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Images/high_5s/Job_youth_Africa_Job_youth_Africa.pdf

African Development Bank (2021). The African Statistical Yearbook. Publishing African Development BankGroup. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/african-statistical-yearbook-2021

AGRA (2019). Africa Agriculture Status Report: The Hidden Middle: A Quiet Revolution in the Private Sector Driving Agricultural Transformation. 7. Available online at: https://agra.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/AASR2019-The-Hidden-Middleweb.pdf

AGRA (2022). Africa Agriculture Status Report. Accelerating African Food Systems Transformation. 10. Available online at: https://agra.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/AASR-2022.pdf

Alden, C. (2013). China and the long march into African agriculture. Cahiers Agric. 22, 16–21. doi: 10.1684/agr.2012.0600

Babu, S. C., and Shishodia, M. (2017) Agribusiness Competitiveness: Applying Analytics, Typology, Measurements to Africa, IFPRI Discussion Papers 1648. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Available online at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/fpr/ifprid/1648.html

Bairwa, S. L., Lakra, K., Kushwaha, S., Meena, L., and Kumar, P. (2014). Agripreneurship development as a tool to upliftment of agriculture. Int. J. Sci. Res. 4, 1–4. doi: 10.15740/HAS/IJCBM/8.1/126-130

Campbell, O. E. (2022). Human capital development and labour market outcomes in Africa: evidence from sub-saharan African countries. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 13. 30–38. doi: 10.7176/JESD/13-6-05

Carayannis, E. G., Campbell, D. F. J., and Rehman, S. S. (2016). Mode 3 knowledge production: systems and systems theory, clusters and networks. J. Innov. Entrep. 5:17. doi: 10.1186/s13731-016-0045-9

Chirinda, N., Abdulkader, B., Hjortsø, C. N., Aitelkadi, K., Salako, K. V., Taarji, N., et al. (2024). Perspectives on the integration of agri-entrepreneurship in tertiary agricultural education in Africa: insights from the AgriENGAGE project. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1348167. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1348167

Cletzer, D. A., Rudd, R., Westfall-Rudd, D., and Drape, T. A. (2016). Agricultural education and training in sub-saharan Africa: a three-step approach to AET Institution building. Int. J. Educ. 8, 73–87. doi: 10.5296/ije.v8i2.9196

Davis, B., Mane, E., Gurbuzer, L. Y., Caivano, G., Piedrahita, N., Schneider, K., et al. (2023). Estimating Global and Country-Level Employment in Agrifood Systems. FAO Statistics Working Paper Series, No. 23–34. Rome: FAO.

Engmann, A., and Ngwakwe, C. C. (2024). Transforming small-scale farm entrepreneurship through innovation: the case of cross link. Acta Acad. Beregsasiensis Econ. 7, 50–63. doi: 10.58423/2786-6742/2024-7-50-63

Etzkowitz, H., and Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university-industry-government relations. Res. Policy 29, 109–123. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

FAO (2023). Gross Domestic Product and Agricultre Value Added 2012–2021. Global and Regional Trends. Rome: FAOSTAT Analytical Briefs Series No. 64.

Franzel, S., Davis, K., Gammelgaard, J., and Preissing, J. (2023). Investing in Young Agripreneurs: Why and How? International Food Policy Research Institute. doi: 10.4060/cc2747en

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., and Trow, M. (1994). The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. Sage Publications, Inc.

Hruby, A., and Mengoub, F. E. (2023). Unlocking Africa's Agricultural Potential. Scaling AgTech to Improve Productivity. Atlantic Council Africa Center. Available online at: https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/2023-09/Unlocking-Africas-Agricultural-Potential_0.pdf

Hytti, U., and O'Gorman, C. (2004). What Is “Enterprise Education”? An analysis of the objectives and methods of enterprise education programmes in four European countries. Educ. Train. 46, 11–23. doi: 10.1108/00400910410518188

IBM (2019). The digital future of agriculture in Africa. Available online at: https://ibmafricananswers.economist.com/the-digital-future-of-agriculture-in-africa/ (Accessed October 15, 2019).

IFAD (2016). Rural Development Report: Fostering Inclusive Rural Transformation, International Fund for Agricultural Development. Rome, Italy: IFAD.

ILO (2019). Africa's Employment Landscape. Available online at: https://ilostat.ilo.org/africas-changing-employment-landscape/

Kadzamira, M. A. T. J., Ogunmodede, A., Duah, S., Romney, D., Clottey, V. A., and Williams, F. (2023). African agri-entrepreneurship in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. CABI Agric. Biosci. 4:16. doi: 10.1186/s43170-023-00157-3

Kangogo, D., Dentoni, D., and Bijman, J. (2021). Adoption of climate-smart agriculture among smallholder farmers: Does farmer entrepreneurship matter?. Land Use Policy, 109:105666. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105666

Kashyap, P., Prusty, A. K., Panwar, A. S., Kumar, S., Punia, P., Ravisankar, N., et al. (2022). Agri-Entrepreneurship Challenges and Opportunities. Today & Tomorrows Printers and Publishers.

Lamdaghri, Z., El Kadi, K. A., Zebakh, S., Soulimani, A. A., Ettabi, M. I., Imani, H., et al. (2023). “The importance of internationalization in the promotion of innovation and entrepreneurship in moroccan universities,” in Erasmus Scientific Days 2022 (ESD 2022) (Atlantis Press), 341–350.

Lombardi, R., Lardo, A., Cuozzo, B., and Trequattrini, R. (2018). The impact of entrepreneurial universities on regional growth: a local intellectual capital perspective. J. Knowl. Econ. 9, 199–211. doi: 10.1007/s13132-015-0334-8

Mbeteh, A., and Pellegrini, M. (2022). Entrepreneurship Education in Africa. A Contextual Model for Competencies and Pedagogy in Developing Countries. Emerald Publishing Limited. doi: 10.1108/9781839097027

Ministry of Agriculture - Kenya (2018). Kenya Youth Agribusiness Strategy 2018–2022. Positioning the Youth at the Forefront of Agricultural Growth and Transformation. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Fisheries and Council of Governors. Available online at: https://kilimo.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Kenya-Youth-in-Agribusiness-Strategy_signed-Copy.pdf

Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries of Morocco (2023). Available online at: https://www.agriculture.gov.ma/ar/ministere/generation-green-2020-2030 (Accessed November 8, 2024).

Mugimu, C. B. (2021). Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Africa Embracing the “New Normal” for Knowledge Production and Innovation: Barriers, Realities, and Possibilities. IntechOpen.

Munang, R., and Andrews, J. (2014). Despite climate change, Africa can feed Africa, Available online at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/special-edition-agriculture-2014/despite-climate-change-africa-can-feed-africa (Accessed May 18, 2025).

Mupfasoni, B., Kessler, A., and Lans, T. (2018). Sustainable agricultural entrepreneurship in Burundi: drivers and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 25, 64–80. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0130

Nigussie, L., Minh, T. T., and Senaratna Sellamuttu, S. (2024). Youth inclusion in value chain development: a case of the aquaculture in Nigeria. CABI Agric. Biosci. 5:44. doi: 10.1186/s43170-024-00243-0

Nin-Pratt, A., Johnson, M., Magalhaes, E., You, L., Diao, X., Chamberlin, J., et al. (2011). Yield Gaps and Potential Agricultural Growth in West and Central Africa, IFPRI Research Report No. 170. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Nkwabi, J. M., and Mboya, L. B. (2019). A review of factors affecting the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Tanzania. Euro. J. Bus. Manage. 11:1. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dfcd/54ad2667f90d4a136bfe93fa470287c32c0a.pdf

Odularu, G. (2023). “The introduction: pandemic preparedness and a-platonic policies for transforming Africa's agrifood systems,” in Agricultural Transformation in Africa, Advances in African Economic, Social, and Political Development, ed. G. O. A. Odularu (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-19527-3_1

Omodan, B. I., Manquma, N., and Mafunda, A. (2024). Decolonising minds, empowering futures: rethinking entrepreneurial education for university students in Africa. J. Curriculum Stud. Res. 6, 1–19. doi: 10.46303/jcsr.2024.8

Osiru, M., and Adipala, E. (2016). Responding to key gaps in Africa's higher agricultural education: lessons from the regional universities forum for capacity building in agriculture. RUFORUM Working Document Series. 14, 1–13. Available online at: http://repository.ruforum.org

Osiru, M., Nampala, P., Ntwali, C., Nambi, E., and Adipala, E. (2012). “The RUFORUM community action research programme: a programme to link African universities to communities and agribusiness,” in RUFRUFORUM Third Biennial Conference, Entebbe, Uganda, 24-28 September 2012. Available online at: https://repository.ruforum.org/documents/ruforum-community-action-research-programme-programme-link-african-universities

Payumo, J. G., AkofaLemgo, E., and Maredia, K. (2017). Transforming sub-saharan Africa's agriculture through agribusiness innovation. Global J. Agric. Innovation Res. Dev. 4, 1–12. doi: 10.15377/2409-9813.2017.04.01.1

Peprah, A. A., and Adekoya, A. F. (2020). Entrepreneurship and economic growth in developing countries: evidence from Africa. Bus Strategy and Dev. 3, 388–394. doi: 10.1002/bsd2.104

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation: Economic and Political Origins of Our Time. New York: Rinehart.

Poulton, C., and Macartney, J. (2012). Can public-private partnerships leverage private investment in agricultural value chains in Africa? A preliminary review. World Dev. 40, 96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.017

Ramutsindela, M., and Mickler, D. (2020). Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals, 1st Edn. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14857-7

Reardon, T., Awokuse, T., Haggblade, S., Kapuya, T., Minten, B., and Vos, R. (2019). “Chapter 2: the quiet revolution in agri food distribution (wholesale, logistics, retail) in sub-saharan Africa,” in Africa Agriculture Status Report: The Hidden Middle: A Quiet Revolution in the Private Sector Driving Agricultural Transformation (Issue 7). Nairobi: AGRA.

Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) (2017). RUFORUM Vision 2030: The African Universities' Agenda for Agricultural Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation (AHESTI). RUFORUM. Available online at: https://repository.ruforum.org/system/tdf/Ruforum

Roundy, P., Brockman, B., and Bradshaw, M. (2017). The resilience of entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Bus. Venturing Insights 8, 99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.08.002

Ruforum-AgriENGAGE Summer School (2023). Available online at: http://www.agriengage.org/sites/ruforum.dd/files/Summer%20School%20Announcement.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Sassi, M., and Mshenga, P. M. (2025). Unlocking the potential of university-industry collaborations in African higher education: a comprehensive examination of agricultural faculties. Ind. Higher Educ. 39, 102–114. doi: 10.1177/09504222241254694

Shane, S., Locke, E. A., and Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 13, 257–279. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

Singh, A. P. (2013). Strategies for developing agripreneurship among farming communities in Uttar Pradesh, India. Acad. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 3, 1–12.

Smidt, H. J., and Jokonya, O. (2023). A framework to develop technopreneurs in digital agriculture value chains in South Africa. J. Foresight Thought Leadersh. 2:13. doi: 10.4102/joftl.v2i1.21

The Economist (2018). Africa Needs a Green Revolution. The Economist. Available online at: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/11/03/africa-needs-a-green-revolution

Tulu, S. K. (2017). A qualitative assessment of unemployment and psychology fresh graduates' job expectation and preference. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 6, 21–29. doi: 10.11648/j.pbs.20170602.12

UAC Startup Valley (2023). UAC Startup Valley Homepage. UAC Startup Valley. Available online at: https://uacstartupvalley.com/

UM6P - Master of Agribusiness Innovation (2023). Available online at: https://www.um6p.ma/master-agribusiness-innovation (Accessed March 15, 2025).

Van Ittersum, M. K., Cassman, K. G., Grassini, P., Wolf, J., Tittonell, P., Hochman, Z., et al. (2013). Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance-a review. Field Crops Res. 143, 4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.09.009

Woldegiorgis, E. T., and Doevenspeck, M. (2013). The changing role of higher education in Africa: a historical reflection. Higher Educ. Stud. 3, 35–45. doi: 10.5539/hes.v3n6p35

World Bank (2007). World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/5990

World Bank (2013). Unlocking Africa's Agricultural Potential. An Action Agenda for Transformation; Sustainable Development Series; 76990. The World Bank. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/16624

World Bank Group (2021). World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2021-2025: Supporting Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zaglul, J. A. (2016). EARTH University educational model: perspective on agricultural educational models for the twenty-first century. Front. Life Sci. 9, 173–176. doi: 10.1080/21553769.2016.1193826

Annex A

List of questions regarding key emerging issues

1. Can you provide some insights and figures to describe the current state of agricultural education at your university? Can you describe if and how it is aligned with the local needs of your country?

2. How does your university address the challenges of introducing Agri-entrepreneurship?

3. Are the conditions present for producing (or attracting) entrepreneurs, inventors, and scientists in the agricultural sector?

4. Are there any specific initiatives by your university to assess the success of initiatives in equipping graduates with the skills and capacity to start sustainable agri-businesses?

5. How important (please provide actual data if available) are the efforts made by your university to attract the youth to agriculture education?

6. How can the government or outside groups help your university's efforts to integrate agri-entrepreneurship into agriculture education more effectively? What are the short- and long-term outcomes (positive and negative if any) of AgriENGAGE in enhancing agri-entrepreneurship education in your university and community engagement skills? Can you describe how theoretical principles of entrepreneurship, innovation, business setup, and risk management are taught to students at your university? Can you provide figures?

7. Can you provide data on the evolution (over the last 5-10 years) of the balance of theoretical training with practical and technical courses related to agriculture and its industry in your university?

8. Can you share any observed positive outcomes or challenges that you encountered in implementing agri-entrepreneurship in the curriculum? What are the main barriers and challenges that need to be addressed to improve agri-entrepreneurial training?

9. Can you please discuss the importance of providing training and support to change the mindset of the entire system and develop a culture of investment in promising agro-business ideas?

10. Please share any other lessons and experiences gained from implementing the AgriENGAGE program and its contribution to the transformation of agriculture communities and the agricultural industry.

Keywords: Triple Helix (TH) model, agri-entrepreneurship education, African higher education, university-industry collaboration, agricultural transformation in Africa

Citation: Chfadi T, Abdulkader B and Chirinda N (2025) From syllabi to startups: lessons from eight African case studies on university-industry collaboration and agri-entrepreneurship education. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1572898. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1572898

Received: 07 February 2025; Accepted: 25 July 2025;

Published: 04 September 2025.

Edited by:

Rusdiaman Rauf, STIE Tri Dharma Nusantara, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Niyaz Panakaje, Yenepoya (deemed to be University), IndiaRahayu Relawati, Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Chfadi, Abdulkader and Chirinda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bisan Abdulkader, YmFiZHVsa2FkZXJAbHVpc3MuaXQ=

Tarik Chfadi1

Tarik Chfadi1 Bisan Abdulkader

Bisan Abdulkader Ngonidzashe Chirinda

Ngonidzashe Chirinda