- College of Economics and Management, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China

Introduction: The adverse impacts of natural disaster shocks threaten the sustainable development of agricultural production and exacerbate the risk of rural households returning to poverty. As a financial tool designed to support the development and production of rural households in China, the role of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households facing natural disaster shocks is a critical issue worthy of attention in the new era after the poverty elimination campaign.

Methods: Based on the three periods of balanced panel data from field tracking surveys conducted in China’s Liupan Mountains contiguous poverty area from 2021 to 2023, this study employs the multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model to assess the effects of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households.

Results: The findings show the following: firstly, targeted microcredit significantly improves the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. The dynamic results suggest that the empowering effect of targeted microcredit strengthens over time. Secondly, targeted microcredit enhances the households’ economic resilience primarily by increasing operational income and human capital. Thirdly, the heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the empowering effect of targeted microcredit on the households’ economic resilience is more pronounced among households engaged in agriculture-oriented livelihoods and stable poverty-eradicating status.

Discussion: Therefore, it is crucial to integrate various resources to innovate and develop targeted microcredit programs, stimulate the endogenous development momentum of poverty-eradicating households, thereby enhancing their economic resilience.

1 Introduction

Globally, poverty reduction remains a significant challenge for many countries, with hundreds of millions still living below the poverty line and lacking basic living security (Liu and Li, 2017; Li et al., 2021). As one of the countries with a relatively high proportion of impoverished people worldwide, China has long been committed to poverty alleviation, implementing a series of practical measures such as targeted poverty alleviation policies and rural revitalization strategies (Liu et al., 2018; Cui et al., 2023). In 2020, China achieved its poverty eradication as scheduled, effectively resolving the long-standing issue of absolute poverty while also making significant contributions to the global efforts aimed at poverty reduction (Wu et al., 2024). To consolidate and expand the achievements of poverty alleviation and continue to promote the development of poverty-stricken areas, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued the document named “Opinions on Realizing the Effective Connection between Consolidating and Expanding the Achievements of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization” in December 2020. Through the joint efforts of all parties, the per capita net income of households that have reached the standard for poverty eradication was 14,342 yuan in 2022, reflecting a year-on-year increase of 14.30%, which exceeds the national average for rural residents. However, the governance of relative poverty remains a long-term and complex challenge. Some households lifted out of poverty remain vulnerable due to inadequate initial resources, unstable incomes, and limited developmental capacities (Huang et al., 2023). Under the influence of shocks such as natural disasters and epidemics, the economic conditions of poverty-eradicating households often deteriorate (e.g., a sharp decline in income) (Arouri et al., 2015), which may lead to a return to poverty and adversely affect their long-term development (Li et al., 2022; Wang and Zhao, 2023). The vulnerability of poverty-eradicating households is strongly correlated with their economic resilience (Manyena and Gordon, 2015). In the new phase of comprehensively promoting rural revitalization, it is essential to shift the focus of vulnerability analysis, such as the risk of poverty relapse among poverty-eradicating households, toward improving economic resilience.

During the period of targeted poverty alleviation (2014–2020), targeted microcredit effectively addressed the challenges of financing difficulties and high costs for registered impoverished households. This financial instrument became a crucial means for supporting poor households in developing industries and achieving stable poverty alleviation in China (Wu et al., 2024). Following the success of the poverty eradication campaign, China entered a five-year transition period during which the consolidation and expansion of poverty alleviation achievements are effectively linked with rural revitalization. Targeted microcredit will undergo further optimization and improvement to better serve the phased development goals in the new era. As a key financial product designed to support production development, targeted microcredit provides loans of “<50,000 yuan, with a three-year term, no collateral guarantees, and government interest subsidies” to rural poverty-eradicating households. By the end of 2023, a total of 277.8 billion yuan in targeted microcredit had been issued nationwide, benefiting 6.51 million poverty-eradicating households in developing specialized industries. When examining the effectiveness of targeted microcredit, existing studies primarily utilized data from the period of targeted poverty alleviation to explore its effects on poverty reduction and income enhancement. Theoretically, targeted microcredit is posited to leverage finance’s “inclusive” nature, enabling impoverished households to access more equitable credit services and productive funds with convenience, low threshold, and minimal cost (Wu et al., 2024). As a result, most scholars believe that it can encourage poor households to start businesses and seek employment (Tarozzi et al., 2015; Thanh and Duong, 2017), while also enhancing capital endowment (Oliphant and Ma, 2021), thus alleviating multidimensional relative poverty and increasing income (Garcia et al., 2020; Su et al., 2023). On the contrary, some other studies have found that microcredit may have adverse effects, such as “excessive debt” (Loubere, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018), “high investment risk and low return rate” (Tan and Lin, 2016), and “reduction in the non-farm labor force” (Crépon et al., 2015), all of which may limit income growth and even exacerbate multidimensional poverty. However, the above studies have overlooked that rural households face an uncertain external environment. Thus, more research is needed to focus on the long-term impact of targeted microcredit during the transition period for poverty-eradicating households.

The concept of resilience originated from ecology, referring to the capacity of ecosystems to absorb disturbances and maintain their functions when subjected to shocks (Holling, 1973). Subsequently, sociology scholars adopted the ecological definition of resilience (Adger, 2000), emphasizing the ability of social-ecological systems to reorganize, renew, and evolve in response to disturbances (Folke, 2006). Agricultural production is highly vulnerable when faced with natural disasters. Therefore, resilience research has gradually been applied to the agricultural field in recent years (Xu et al., 2024), including agricultural system resilience (Urruty et al., 2016; Meuwissen et al., 2019; Dardonville et al., 2020), agricultural economic resilience (Volkov et al., 2022; Gao, 2024), and agricultural poverty alleviation resilience (Lade et al., 2017). At the micro-subject level, scholars primarily focus on the economic resilience of rural households, concentrating on the following two aspects. The first aspect to consider is the connotation of household economic resilience. As the opposite of vulnerability, economic resilience refers to the ability of households to adapt to uncertain environments swiftly and to achieve sustained survival and development when faced with various pressures (Milhorance et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2024). The second aspect pertains to the measurement of households’ economic resilience. There are two widely used measurement methods in existing research. One approach involves constructing a multidimensional indicator system to measure the economic resilience index (Smith and Frankenberger, 2018; Asmamaw et al., 2019; Savari et al., 2023). This method views economic resilience as a latent capacity that reflects the influence of both observable and unobservable attributes of individuals, families, and communities (Barrett et al., 2021), and is specifically manifested in three dimensions: resistance, adaptability, and transformation (Bekele, 2022). Another standard method is the conditional moments-based approach, proposed by Cissé and Barrett (2018). This approach estimates economic resilience as the conditional probability of meeting a certain minimum welfare standard and can dynamically predict the long-term development of households under natural disaster shocks. Subsequently, some scholars have used indicators such as income, assets, and consumption poverty lines to construct household welfare standards for measuring economic resilience (McPeak and Little, 2017; Phadera et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). The above studies have made significant contributions to resilience-related research, both in theoretical discussions and empirical analysis, providing a solid foundation for this article’s examination of the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households.

In summary, economic resilience is a critical bridge connecting natural disaster shocks with household development, offering a new perspective for researching long-term poverty alleviation mechanisms and policy adjustments. Given this, this paper evaluates the impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households in the new era. Compared with existing studies, this research makes three marginal contributions to the literature. First, we incorporate natural disaster shocks into the analysis of household potential capacity, exploring the impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households from an uncertain perspective. Second, in contrast to the data derived from the targeted poverty alleviation period and cross-sectional data used in previous studies, this research utilizes three-period balanced panel data from 2021 to 2023 on China’s poverty-stricken households to evaluate the long-term effects of targeted microcredit in the post-poverty alleviation era. Third, this study further explores the heterogeneous impacts of targeted microcredit on households with different livelihood strategies and poverty-eradicating attributes in the new era.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we analyze the theoretical mechanism of the targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. Section 3 introduces the research design. Section 4 presents the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the main results. Section 6 concludes our findings.

2 Conceptual definition and theoretical analysis

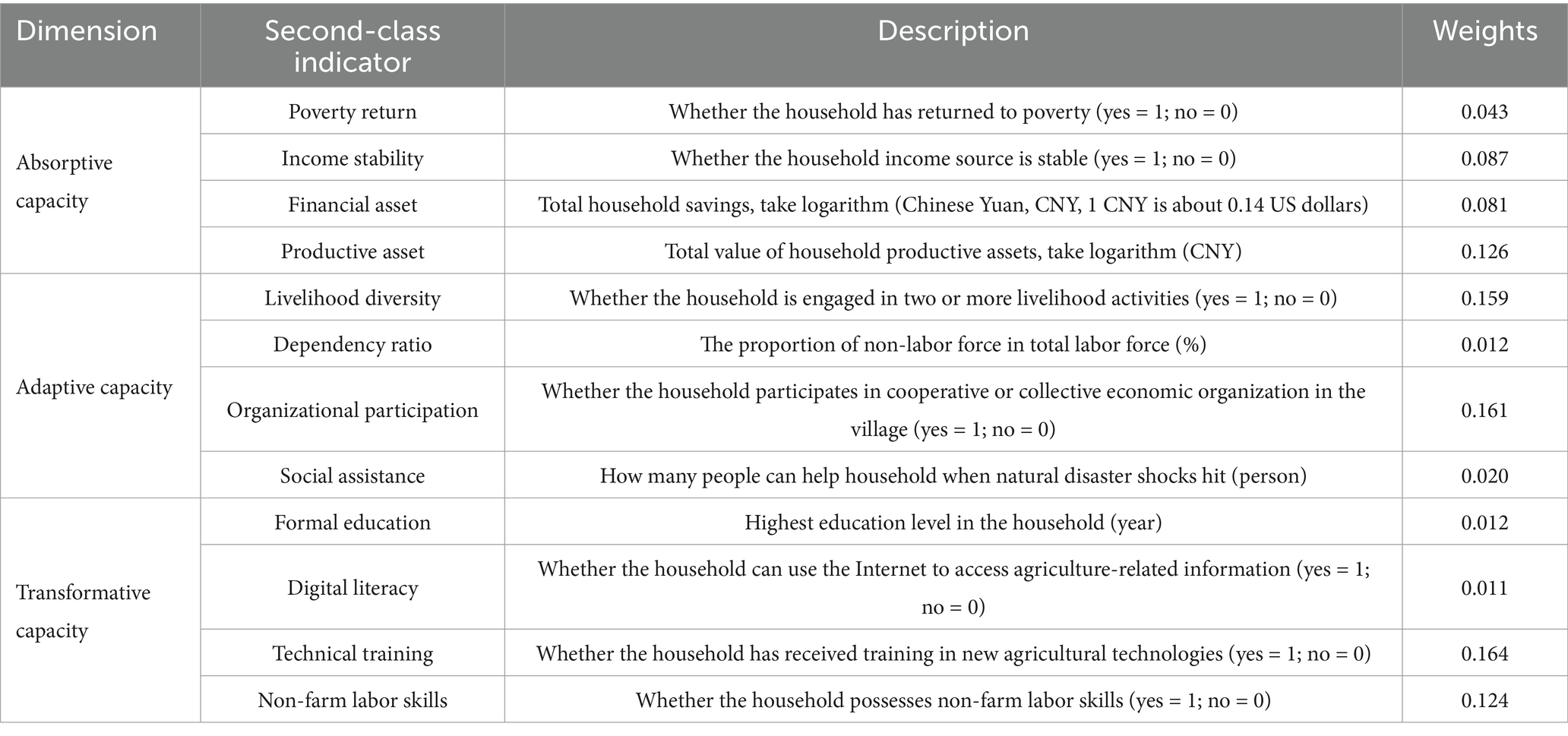

2.1 Measuring economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households

Building on the concept of the resilience of social-ecological systems and considering the specific characteristics of rural China, this study defines the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households as their “capacity to avoid a return to poverty, adjust their structure to restore stability, and achieve sustainable development in the face of natural disaster shocks.” The core idea of this conceptualization is that economic resilience is a multidimensional, comprehensive capacity of households. Drawing on the household resilience research conducted by the researchers (Folke, 2006; Smith and Frankenberger, 2018; Bekele, 2022), this study evaluates the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households across three dimensions: absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and transformative capacity.

First, absorptive capacity refers to the ability of households that have escaped poverty to resist natural disaster shocks and prevent a relapse into poverty. Financial assets and productive capital serve as these households’ financial and physical resources, which can be liquidated to maintain economic stability in the face of natural disaster shocks (Tan et al., 2020). The risk of returning to poverty and income stability are critical indicators of the economic vulnerability for poverty-eradicating households and are directly linked to their absorptive capacity (Do, 2023). Second, adaptive capacity refers to the ability of households that have escaped poverty to adjust their resource allocation to recover swiftly from the adverse impacts of shocks. A higher dependency ratio indicates a heavier support burden for the household, making it more difficult to recover from shocks (Atara et al., 2020). The support provided by the government, relatives, friends, neighbors, and various organizations reflects the household’s capacity to access external resources. This support is crucial to cope with sudden shocks and enhance adaptability (Xiong and You, 2019). Third, transformative capacity refers to the ability of households that were lifted out of poverty to proactively adapt and innovate their livelihood models in response to natural disaster shocks, ultimately achieving self-sustained development. Digital literacy reflects a household’s ability to acquire and utilize information, knowledge, and opportunities in the digital era and is a critical indicator of transformative capacity (Xie et al., 2024). Formal education and skills training represent the household’s ability to acquire new knowledge and are closely related to its transformative capacity (Quandt, 2018).

2.2 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

2.2.1 Targeted microcredit and the economic resilience

This study builds on the approach of Folke (2006), viewing resilience as a dynamic and multifaceted capability. Rooted in the theoretical framework of social-ecological system resilience, this concept captures how such systems can absorb impacts, adapt to change, and undergo transformation when faced with natural disaster shocks. On a smaller scale, households act as individual units whose economic resilience relies not only on external system support but also on their ability to adjust proactively and respond strategically. Therefore, this study analyzes the impact of targeted microcredit on households’ economic resilience from the following three dimensions. In terms of absorptive capacity, most formal financial institutions in China, such as credit unions and banks, tend to exclude disadvantaged rural households to control operational risks and reduce transaction costs, thereby leaving these households vulnerable to financial constraints (Wu et al., 2024). Targeted microcredit can provide these households with collateral-free loans needed for production and operational activities, easing liquidity constraints and improving their ability to withstand financial shocks (Arouri et al., 2015; Goodspeed, 2016), thus enhancing their resilience to remain stable and avoid falling back into poverty. In terms of adaptive capacity, targeted microcredit can increase households’ productive capital, help optimize the allocation of production factors, improve production and operational efficiency (Shano and Waje, 2024), and encourage households to transition from traditional, single livelihood to more diversified strategies (Jia et al., 2013). This transition ultimately strengthens households’ resilience to adapt to natural disaster shocks. Regarding transformative capacity, households that have escaped poverty have long been politically, economically, and socially disadvantaged, making it difficult to access credit markets and overcome inherent capacity constraints effectively. Targeted microcredit facilitates the integration of these households into industrial development through production technology training, stimulates their endogenous development motivation, and ultimately strengthens their capacity for sustainable development (Garcia et al., 2020). Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes Hypothesis 1.

H1: Targeted microcredit can enhance the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households.

2.2.2 Targeted microcredit, operational income and the economic resilience

The suddenness and persistence of natural disaster shocks can cause poverty-eradicating households to lack financial support, restricting the sustainable development of their production and business activities, thereby leading to economic vulnerability (Xie et al., 2024). Operational income, as the primary source of household revenue, is the fundamental guarantee and critical driving force for achieving survival and development. Targeted microcredit is crucial in promoting production and operational activities, ensuring operational income, and enhancing the households’ economic resilience (Su et al., 2023). On the one hand, targeted microcredit can stimulate the endogenous development motivation of poverty-eradicating households by fostering aspirations and knowledge, thereby improving job satisfaction and labor enthusiasm. This, in turn, promotes operational income growth, enhances the households’ economic resilience, and facilitates sustainable development (Garcia et al., 2020). On the other hand, targeted microcredit provides financial support to households that have escaped from poverty, enabling them to transfer land for large-scale operations. This process can leverage economies of scale, resulting in a significant increase in agricultural operational income and enhancing the household’s ability to cope with natural disaster shocks. In summary, targeted microcredit enhances the operational income of poverty-eradicating households and their ability to withstand natural disaster shocks. Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 2.

H2: Targeted microcredit can improve the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households by increasing their operational income.

2.2.3 Targeted microcredit, human capital and the economic resilience

Human capital accumulation is the endogenous driving force for preventing the return to poverty, blocking the intergenerational transmission of poverty, and alleviating relative poverty (Cheng et al., 2021). It is also a crucial source for households to achieve sustainable development (Liu et al., 2022). However, shocks such as natural disasters, unemployment, illness, and accidents can adversely affect agricultural production conditions and the physical capital of households. To ensure basic living expenses, rural households affected by these shocks often reduce expenditures on their children’s education and healthcare (Herrera-Almanza and Cas, 2021). In the long run, this severely impacts households’ human capital, affecting their sustainable development. Targeted microcredit empowers the economic resilience of households lifted out of poverty through human capital in two primary ways. On the one hand, targeted microcredit strengthens the ability of poverty-eradicating households to resist shocks and restore stability by improving their human capital. Typically, targeted microcredit projects are accompanied by skills training, such as agricultural technology, business management, and marketing, which enables households to utilize credit funds more effectively and optimize their production structures. These skills training programs also provide households with opportunities for off-farm employment and broaden their income sources, which can effectively diversify the impact of risky shocks on the household economy (Khandker and Koolwal, 2016). On the other hand, targeted microcredit enhances the long-term development capacity of households lifted out of poverty by increasing investment in human capital. Households receiving targeted microcredit use the credit funds for production and business operations, leaving a “surplus” of the funds initially allocated for production inputs. To improve their living and overall welfare, households often prefer to use the “surplus” funds to invest in human capital, such as health and education (You and Annim, 2014). Therefore, considering the role of human capital, targeted microcredit can alleviate the liquidity constraints faced by poverty-eradicating households, significantly improve their sustainability, and promote intergenerational upward mobility (Wu et al., 2024), enhancing household economic resilience. Based on this analysis, this paper proposes Hypothesis 3.

H3: Targeted microcredit can improve the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households by increasing household human capital.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

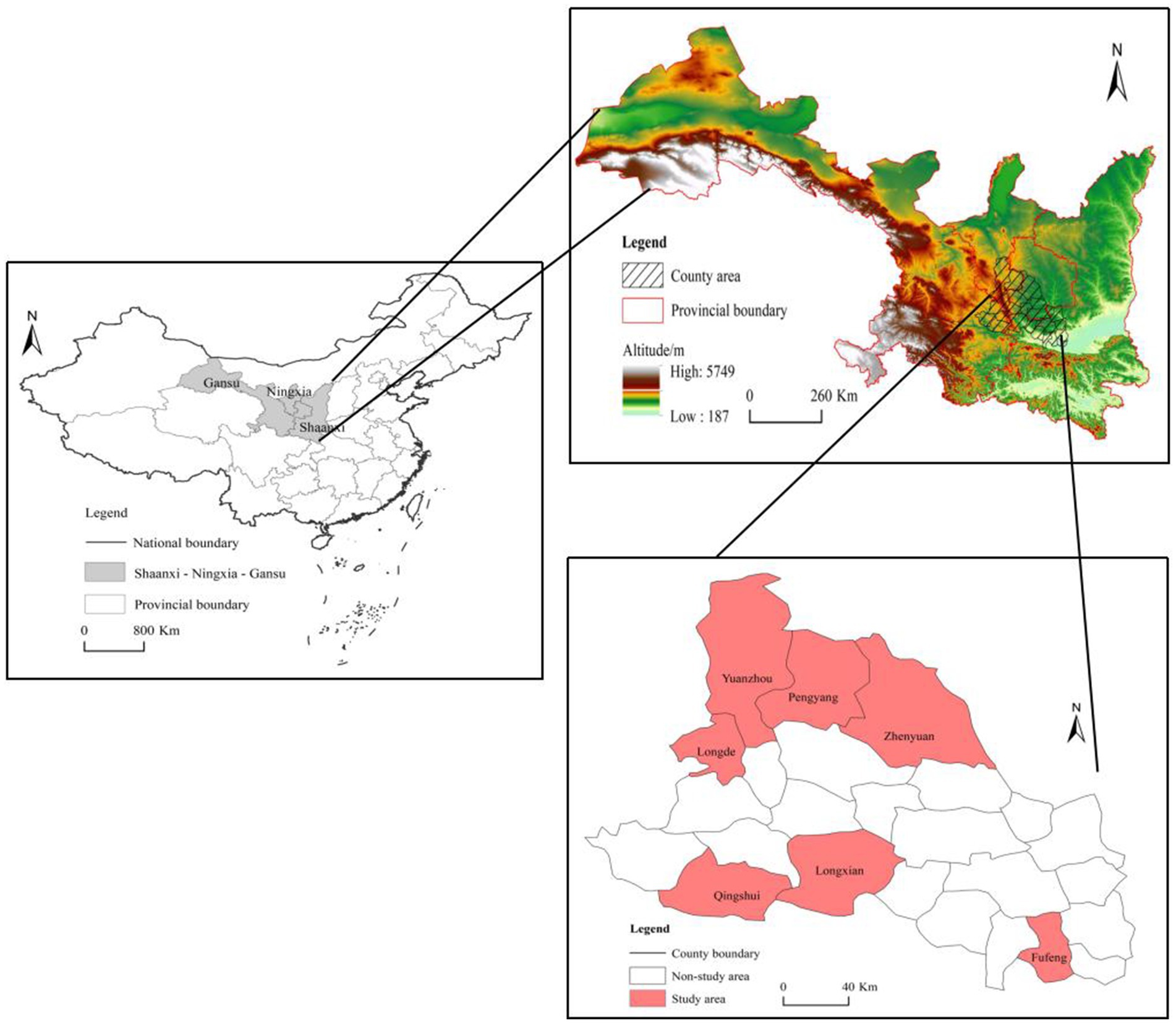

The Liupan Mountains region is one of the 14 contiguous poverty areas identified in the “Outline of Poverty Alleviation and Development in China’s Rural Areas (2011–2020).” The region is located in the border zone between the west-central Loess Plateau and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, with an area of 152,700 km2, covering a total of 61 counties (districts) in Shaanxi Province, Gansu Province, Qinghai Province, and the Ningxia Autonomous Region, China. This paper selects seven counties in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia Province (Regions) in the Liupan Mountains contiguous poverty area as the study area (Figure 1). These seven counties were all designated as impoverished counties by the former State Council’s Poverty Alleviation Office. Compared with other contiguous poverty areas, there are two key reasons for selecting the Liupan Mountains region as the study area in this research. First, the Liupan Mountains region is one of the most deeply impoverished areas, representing the “short board” of China’s 14 contiguous poverty regions. At the end of 2019, the Liupan Mountains region had the highest incidence of rural poverty at 2.6 percent. Although, the Liupan Mountains region experienced rapid development during the poverty alleviation period, there remains a significant gap compared with other contiguous poverty areas and more developed regions. Therefore, the Liupan Mountains region remains one of the poorest and most in need of support in China. Second, in the new era, this region faces challenges in consolidating and expanding the achievements of poverty alleviation. On the one hand, the Liupan Mountains region suffers from a fragile industrial foundation, a substantial population of low-income farmers, and insufficient skills, all of which hinder agricultural development and the income potential of farmers. On the other hand, the livelihood vulnerability of ecological migrants in the Liupan Mountains is high, and there is a significant risk of returning to poverty in the face of natural disaster shocks. Therefore, in the context of consolidating and expanding the achievements of poverty alleviation and effectively linking rural revitalization, the Liupan Mountains region needs targeted microcredit to develop industries for sustained income generation and to empower the sustainable development of rural household economies.

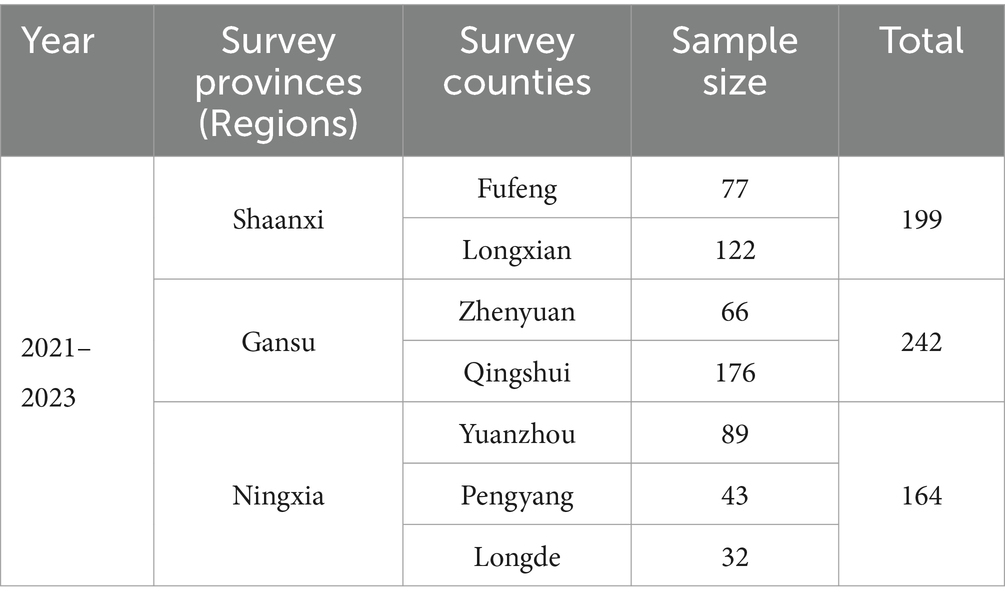

3.2 Data source

The data used in this study were derived from a field tracking survey conducted by the research team in the contiguous poverty regions of the Liupan Mountains from 2021 to 2023. To ensure the representativeness of the research subjects, the research team employed a method that combines stratified sampling with random sampling. Firstly, based on the careful consideration of the promotion of targeted microcredit policies and the level of regional economic development, we selected seven counties (Fufeng, Longxian, Zhenyuan, Qingshui, Yuanzhou, Pengyang, and Longde), referred to as districts, in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia Provinces (Regions) as the study areas. Secondly, sample townships (towns) and villages were drawn in each sample county (district) using the probability proportional-to-size sampling method. Finally, we randomly selected 10–15 households with established poverty eradication cards in each village. After excluding samples not exposed to natural disaster shocks and invalid questionnaires, we obtained 605 poverty-removing households of three-period balanced panel data, containing 1,815 observations (Table 1).

3.3 Variable selection

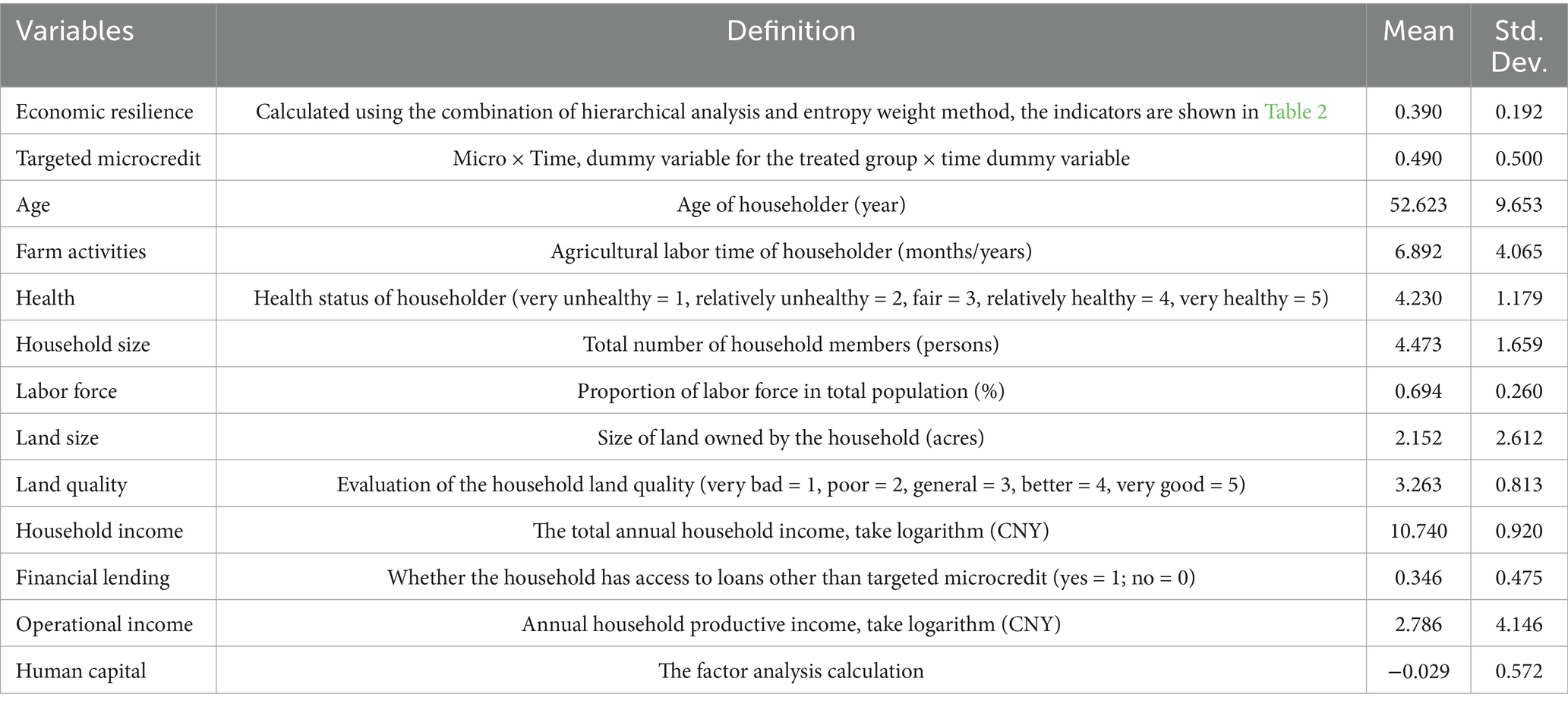

3.3.1 Economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households

This study constructs an economic resilience index for rural households by combining the hierarchical analysis and entropy weight methods. Based on theoretical analysis and existing research, the paper selects indicators for measuring the households’ economic resilience across three dimensions: absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and transformative capacity. The specific indicators used to measure each of these dimensions are detailed in Table 2.

We integrate the hierarchical analysis with entropy weight methods to determine the weights for each indicator, subsequently calculating the households’ economic resilience index through a linear weighted average approach. First, the hierarchical analysis method obtains each economic resilience index’s subjective weights ( ) by constructing the judgment matrix, calculating the maximum eigenroot value, and passing the consistency test. Secondly, the entropy weight method calculates the information entropy and redundancy to get the objective weight ( ) of each indicator of economic resilience after the standardized processing of each indicator. Finally, the combination weight ( ) of each indicator of economic resilience is calculated.

Optimization of Equation 1 using Lagrange multiplier method.

The combined weight of each indicator pertaining to economic resilience is calculated using Equation 2, and the indicators are then weighted and summed using linear weighting to compute the final economic resilience index of poverty-eradicating households.

3.3.2 Targeted microcredit

Targeted microcredit is modeled as an interaction term between the between-group and time dummy variables. The between-group dummy variable represents whether the households have borrowed targeted microcredit after being lifted out of poverty. In this paper, households that borrowed targeted microcredit are defined as the treatment group and assigned a value of 1, while those that have not borrowed are designated as the control group and assigned a value of 0. The time dummy variable indicates whether the observation pertains to the year in which targeted microcredit was borrowed or the subsequent years. If the households respond affirmatively, the time dummy variable is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0.

3.3.3 Mechanism variables

The mechanism variables in this study include operational income and human capital. Operational income is defined as the total annual revenue earned by rural households through productive activities such as planting, livestock breeding, and entrepreneurial activities. Human capital, as defined by Schultz (1961), encompasses a combination of factors such as knowledge, skills, and abilities possessed by individuals, and it reflects the capacity of households to access and effectively utilize credit funds. Therefore, drawing on the research (Islam and Walkerden, 2022), this paper selects household health status, educational attainment, work experience, and skills training as proxy variables for human capital and calculates a composite human capital index using factor analysis.

3.3.4 Control variables

In reference to pertinent studies (Xie et al., 2024), this paper selects factors associated with households’ economic resilience as control variables. At the individual level, these variables include the age, agricultural labor, and health status of the household head. At the household level, the characteristics considered include household size, labor share, land size, land quality, household income, and financial lending. Furthermore, this study introduces household and time fixed effects to control as much as possible for omitted variables that may bias the results of the baseline regression. The control variables used in this study are presented in Table 3.

3.4 Model specification

3.4.1 Baseline model

Given the variations in the timing of accessing to targeted microcredit by households that have been lifted out of poverty, this paper follows the methodology of Beck et al. (2010) by using the multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) model to examine the impact of targeted microcredit on the households’ economic resilience. The idea of the model is to categorize households into treatment and control groups according to whether they have borrowed targeted microcredit, and to identify the differences in economic resilience between the two groups before and after the credit intervention. Ultimately, the model aims to estimate the average treatment effect of targeted microcredit policy. The model is specified as follows.

Where denotes the economic resilience of the households that have been lifted out of poverty. represents a dummy variable for the treatment group (indicating whether the household borrowed targeted microcredit), and is the time variable reflecting the period for borrowing targeted microcredit of poverty-eradicating households. denotes a set of control variables that may affect the economic resilience of the households. and represent the individual and time fixed effects, respectively. is the random disturbance term. The coefficient demonstrates the average treatment effect of targeted microcredit on the households’ economic resilience.

3.4.2 Mediation effects model

To examine the mechanism through which targeted microcredit influences the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households, this paper employs causal mediation analysis. The model is presented below.

Equations 4, 5 illustrate the mediating mechanisms through which the targeted microcredit affects households’ economic resilience. In this context, the coefficient represents the effect of the targeted microcredit on the mediating variable, while the coefficient of indicates the mediator’s effect on households’ economic resilience. The two mediating variables are operational income and human capital. is the mediating variable. The coefficient in Equation 5 measures the targeted microcredit’s direct effect on the households’ economic resilience after controlling for the mediating and other control variables.

3.4.3 Parallel trend test model

An essential prerequisite for using the multi-period DID model is that the treatment and control groups must satisfy the parallel trends assumption. In the absence of targeted microcredit interventions, there should be no systematic difference in the trend of households’ economic resilience between the two groups. To test for parallel trends, this paper adopts the event study approach and constructs the following model (Jacobson et al., 1993).

In Equation 6, k represents the time window during which the sample of poverty-eradicating households borrowed targeted microcredit. Where, k = −2 denotes the second year before the sample accessed targeted microcredit, and k = 4 + refers to the fourth year and subsequent years after the sample accessed targeted microcredit. The definitions of the other variables remain consistent with those in Equation 3.

4 Empirical results

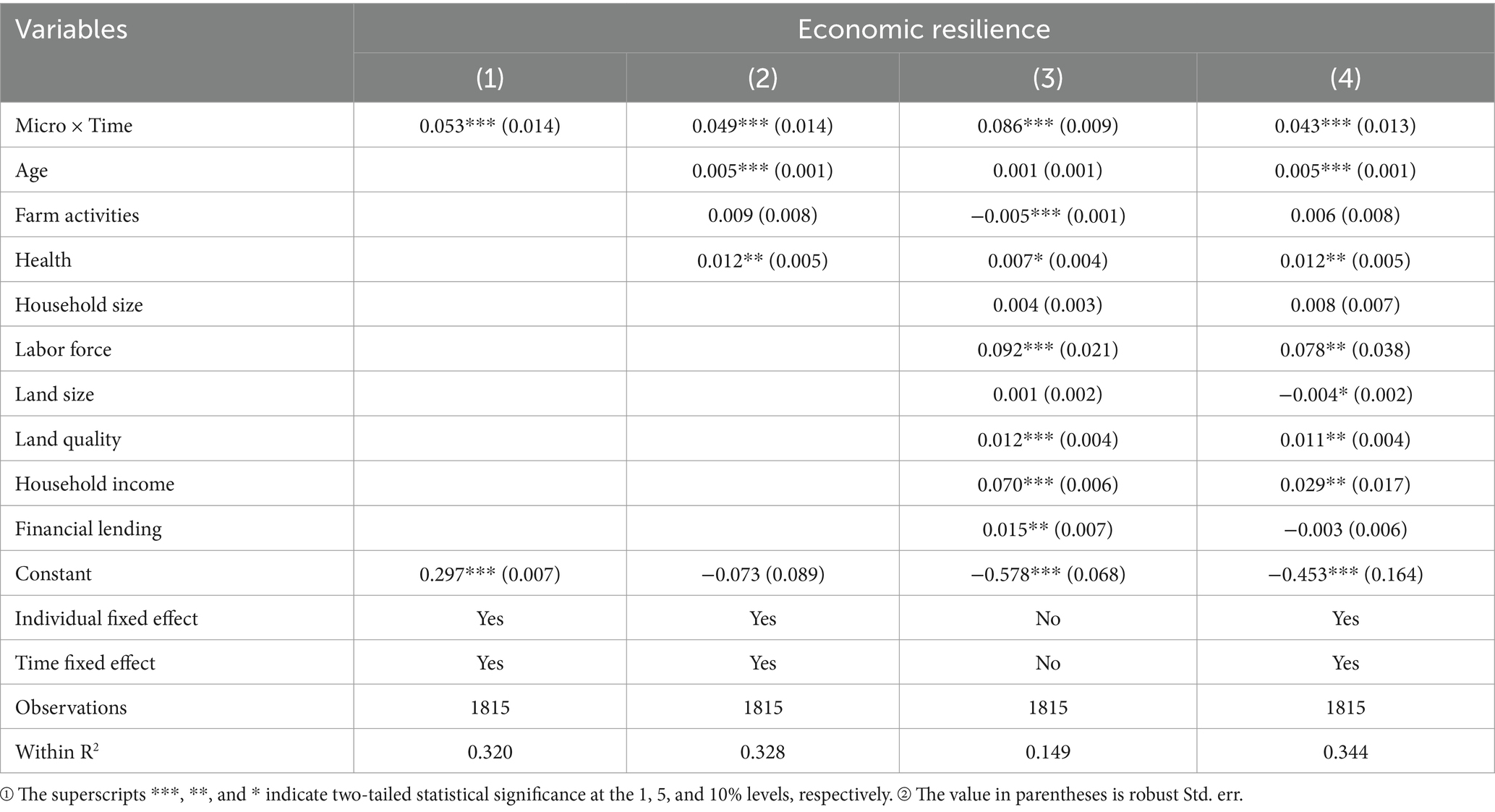

4.1 Baseline regression results

Table 4 presents the principal results regarding the impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of households lifted out of poverty. In column (1), the estimated coefficient of targeted microcredit on economic resilience is 0.053, which is statistically significant at the 1% confidence level when other variables are not controlled for. To ensure the robustness of the baseline regression results, this study progressively adds control variables in columns (2) to (4). As indicated in column (4) of Table 4, the coefficient of targeted microcredit remains statistically significant at the 1% confidence level after accounting for control variables, as well as individual and time fixed effects, with a regression coefficient of 0.043. This finding suggests that economic resilience is increased by 4.3% on average with each unit increase in the probability of borrowing targeted microcredit. Thus, in the context of consolidating and expanding the achievements of poverty alleviation, targeted microcredit can significantly enhance the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households, thereby serving as a crucial driver in empowering them to sustain their development. Collectively, these results provide strong support for Hypothesis H1.

4.2 Robustness tests

4.2.1 Parallel trend and placebo test

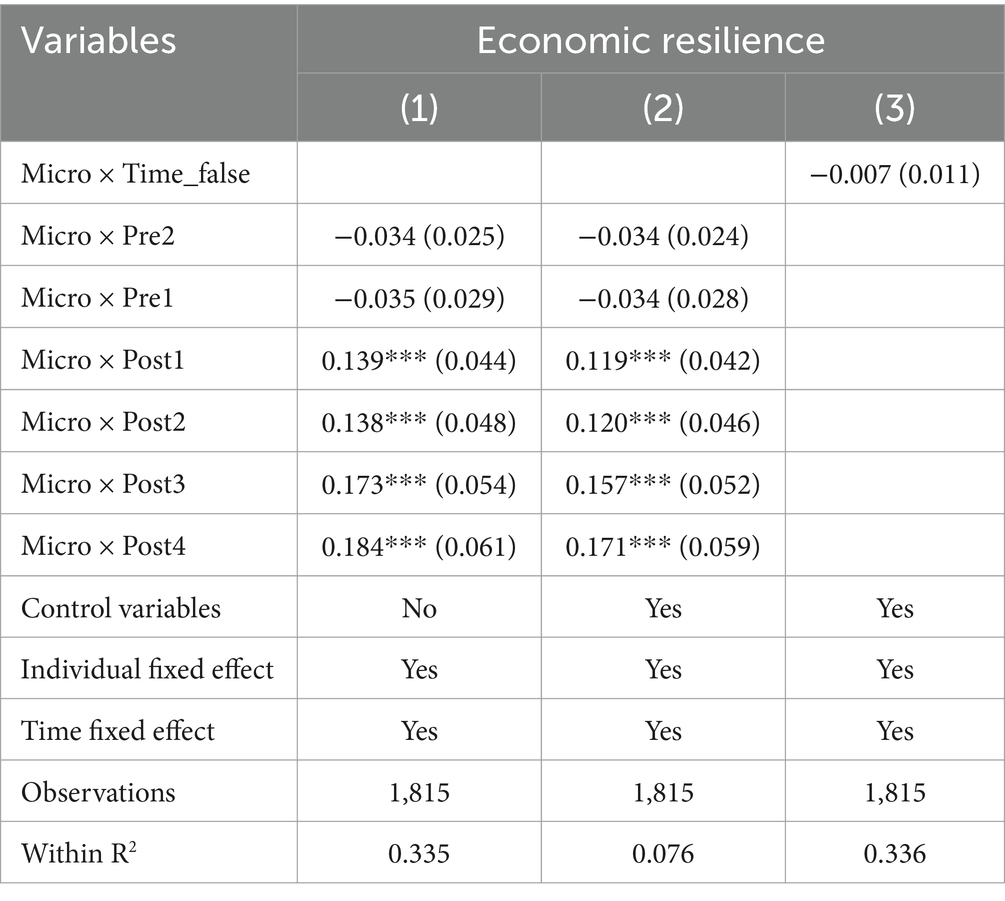

The validity tests of the multi-period DID model included parallel trend and placebo tests. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 present the results of the parallel trend test. The estimated coefficients for the interaction term Micro × Time are insignificant prior to households borrowing targeted microcredit. Conversely, after borrowing targeted microcredit, the estimated coefficients of Micro × Time exhibit a significantly positive value. This indicates that, before borrowing targeted microcredit, the economic resilience of households in both the treatment and control groups followed the same trend. Therefore, the multi-period DID model successfully passes the parallel trend test. Furthermore, the results of the dynamic effect indicate that the empowering impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households gradually strengthens over time. Subsequently, this study conducts the placebo test following the randomized sample method (Baker et al., 2008). The specific processing steps are outlined as follows: First, all the values of the variables in the treatment group are extracted and temporarily stored. These values are then randomly assigned to each sample to create a “dummy variable for the fake treatment group.” Second, the Stata software is employed to randomly generate “fake time dummy variable.” Finally, this study constructs the interaction terms of the “fake targeted microcredit” variable and estimates the regression results according to Equation 3. Column (3) of Table 5 shows that the relationship between the “fake targeted microcredit” variable and the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households is statistically insignificant, indicating that it passes the placebo test. Therefore, the selection of the multi-period DID model for this study is valid and further supports the robustness of the baseline regression results.

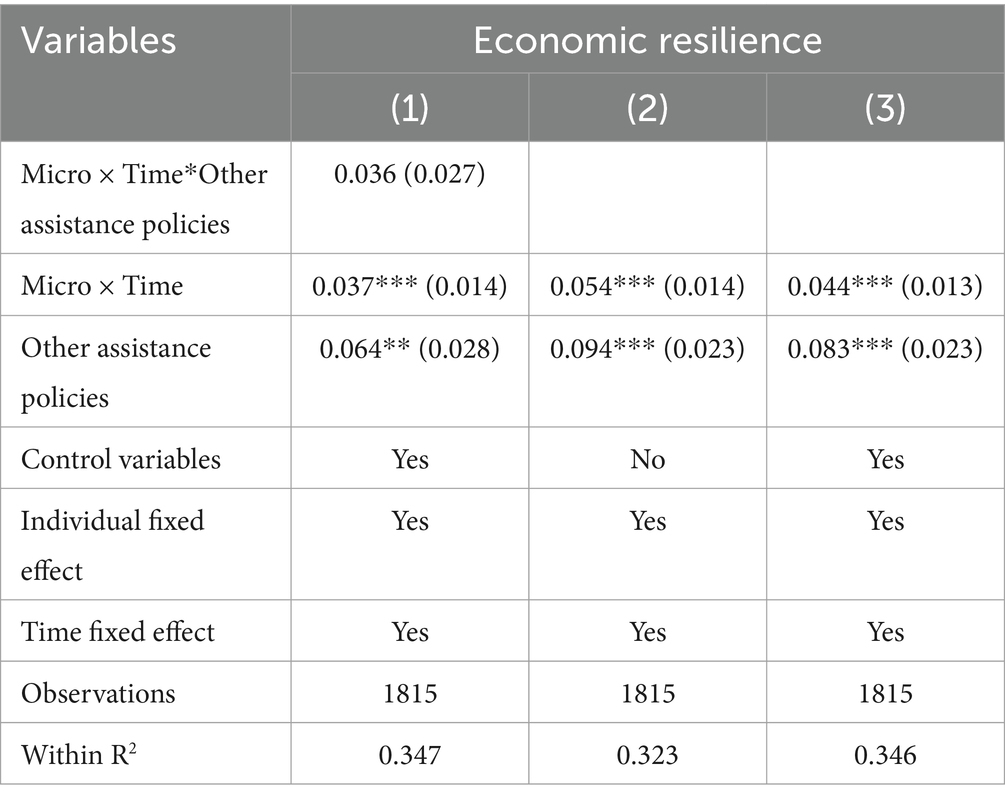

4.2.2 Excluding the impact of other assistance policies

In 2020, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China issued a document named “Opinions on Realizing the Effective Connection between Consolidating and Expanding the Achievements of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization.” This document mandated that the primary assistance policies remain generally stable during the transition period. As a result, in addition to receiving targeted microcredit assistance, households that have been lifted out of poverty are also influenced by other assistance policies, which may introduce bias into the baseline estimate. This study aims to clarify how different policies interact by introducing an interaction term between targeted microcredit programs and other assistance policies. As shown in column (1) of Table 6, the estimated coefficient of the interaction term is not statistically significant, implying that there is no complementary effect between these policies. Thus, we can assume that other assistance policies do not significantly influence the outcome. To ensure the robustness of this finding, this study further controlled for other assistance policies. The results in columns (2) and (3) of Table 6 show that, after accounting for other assistance policies, targeted microcredit continues to significantly enhance the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households at the 1% level. These findings confirm that our baseline results are robust.

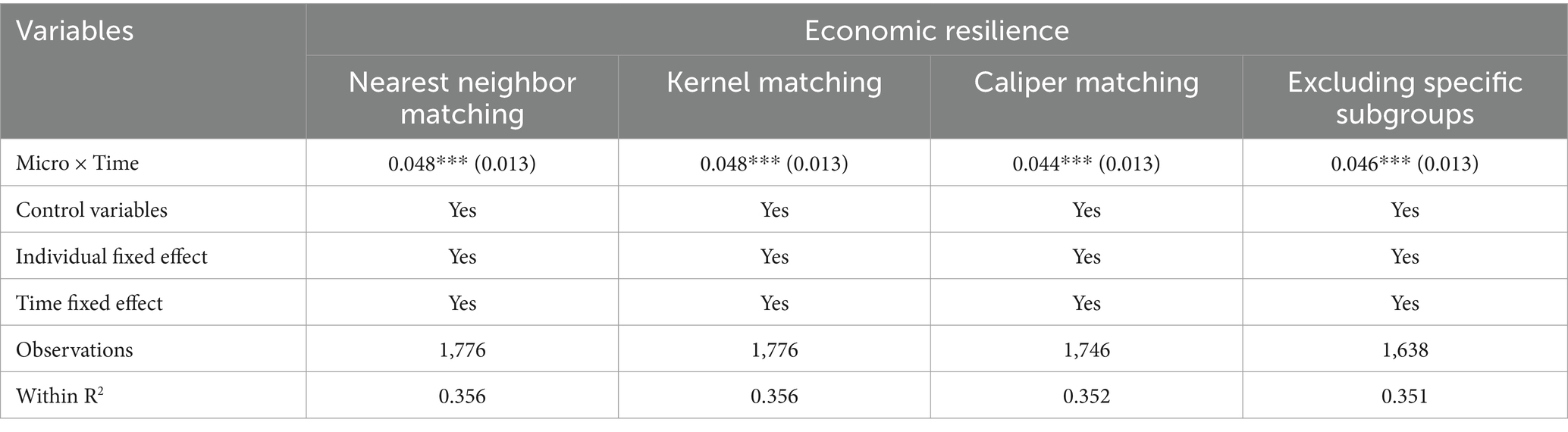

4.2.3 PSM-DID estimation

The decision to borrow targeted microcredit among poverty-eradicating households is not a random process. This may depend on various factors such as household perceptions, agricultural production preferences, resource endowments, etc. As a result, this study may face a sample self-selection problem, which could introduce bias in the estimation of the baseline model. To address the potential endogenous differences between the treatment and control groups that may affect the estimation results, this study adopts the PSM-DID model proposed to conduct a robustness test of the baseline regression results. The core idea of the PSM-DID model is to eliminate the effect of the sample self-selection on the estimation results by constructing a counterfactual analytical framework in which households that borrowed targeted microcredit have characteristics similar to those of households that did not. Commonly used matching methods of the PSM model in the academia include nearest neighbor, kernel, and caliper matching. Consequently, this study combines these three matching methods with the multi-period DID model to estimate the impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of households that have been lifted out of poverty. The results presented in Table 7 indicate that, after addressing the sample self-selection problem, targeted microcredit continues to significantly enhance the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. In conclusion, the results of all the aforementioned tests confirm that the baseline results of this study are robust.

4.2.4 Excluding specific subgroups

In China, Five-Guarantee households and those receiving extreme hardship support are unique groups within the registered impoverished households, receiving comprehensive financial subsidies and social security support from the government. Policies such as special disaster relief funds and housing renovation subsidies can significantly improve these groups’ ability to recover after disasters. Therefore, these government interventions may confound the actual impact effect of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. To address this, our study excludes data from Five-Guarantee households and those receiving extreme hardship support for a robustness check. The results in Table 7 show that targeted microcredit still enhances the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households at the 1% significance level, with an estimated coefficient of 0.046, which exceeds the baseline regression coefficient. This indicates that the policy effect of targeted microcredit is enhanced after excluding specific subgroups, further verifying the robustness of this study.

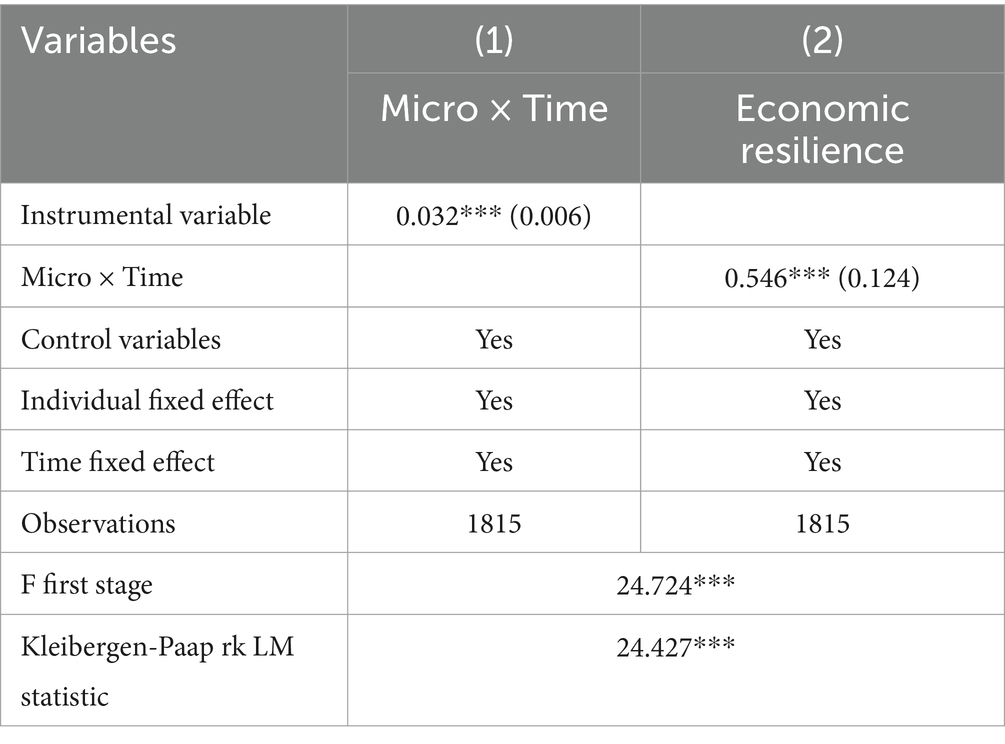

4.2.5 Instrumental variable estimation

To mitigate the issue of non-random access to microcredit, this study utilizes the instrumental variable method as a robustness check. This study uses the distance to the nearest bank branch as the instrumental variable and employs a two-stage regression analysis. The Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic exceeds the critical value of 16.38 at a 10% bias level, indicating there is no issue of weak instruments. Furthermore, the p-value of the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic is 0.00, rejecting the original hypothesis of under-identification of the instrumental variable. Therefore, the instrumental variable used in this study is validated. According to the results in column (1) of Table 8, the bank distance statistically correlates with the endogenous variable at the 1% level. The second-stage regression results indicate that, after correcting for endogeneity using the instrumental variable, the estimated coefficient of targeted microcredit remains significantly positive. This finding further substantiates the robustness of our conclusions.

4.3 Analysis of mechanisms test

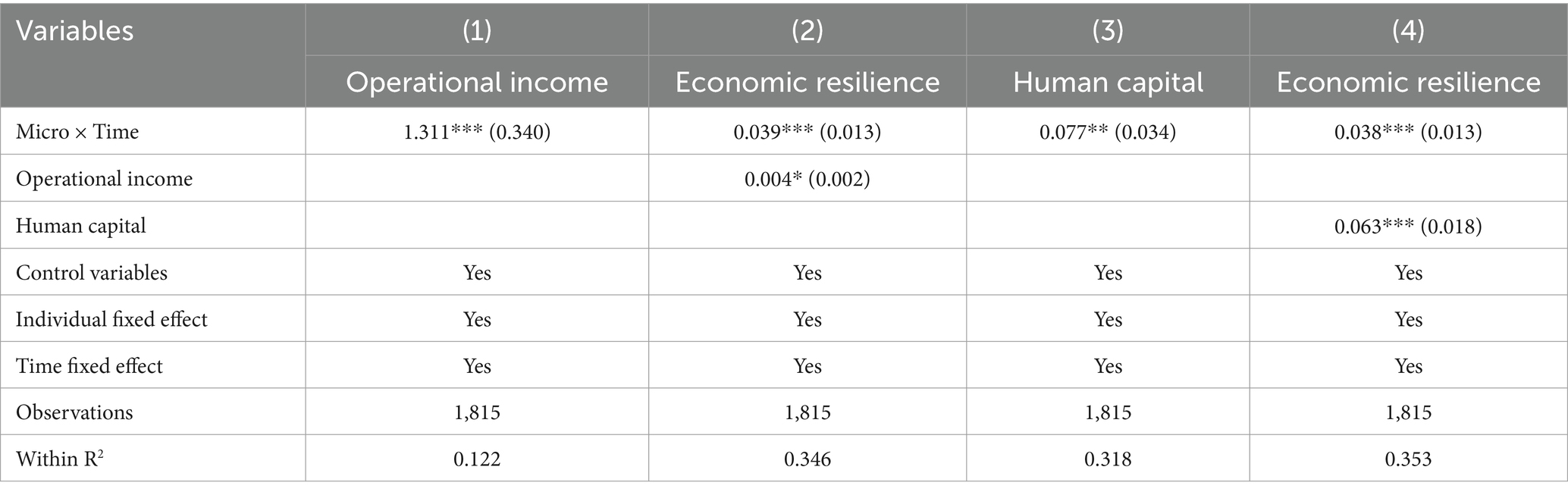

This study examines the mechanism through which targeted microcredit influences the economic resilience of households, utilizing models (4) and (5), with the estimation results presented in Table 9. Column (1) indicates that targeted microcredit significantly increases the operational income of households. In column (2), after incorporating the mechanism variable, targeted microcredit continues to exhibit a significant positive impact on household economic resilience. However, the effect of operational income in column (2) does not pass the significance test, suggesting that operational income fully mediates the pathway through which targeted microcredit enhances household economic resilience, thereby supporting hypothesis H2. Furthermore, column (3) of Table 9 demonstrates that targeted microfinance significantly improves human capital. The coefficient of Micro × Time in column (4) is significant at the 1% level, indicating that targeted microcredit indirectly strengthens the economic resilience of households lifted out of poverty by enhancing human capital, thus confirming hypothesis H3.

4.4 Heterogeneity analysis

4.4.1 Heterogeneity of household livelihood strategies

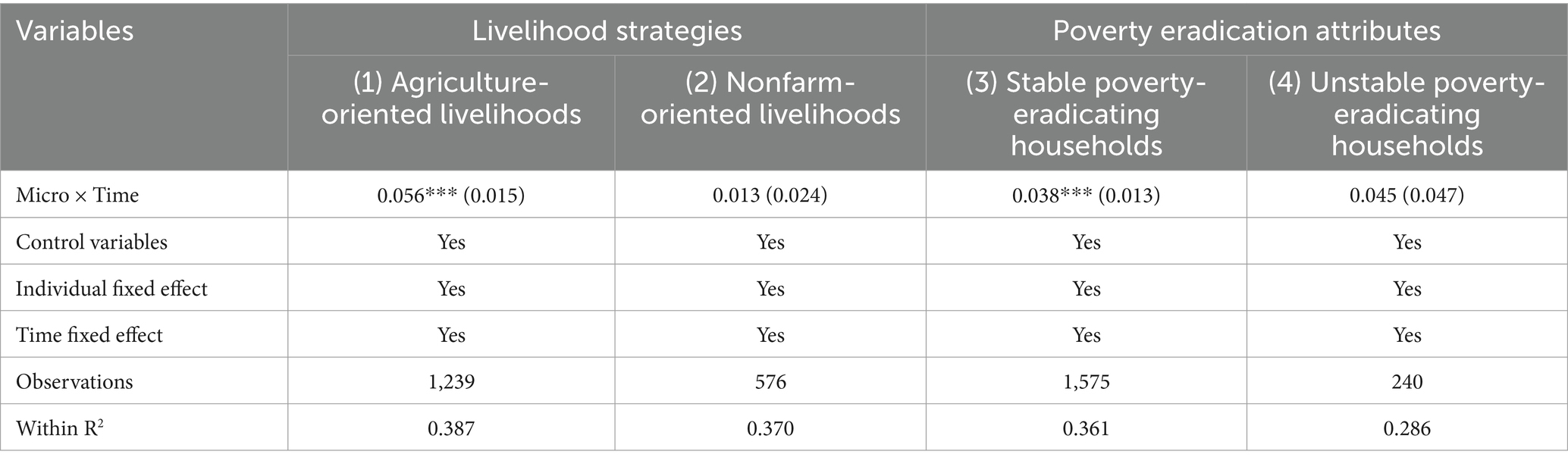

China, as a vast nation, exhibits considerable variability among rural households. Therefore, it is essential to analyze the heterogeneity of households that have been lifted out of poverty. The targeted microcredit policy mandates that credit funds borrowed by households must be used exclusively for agricultural and non-agricultural productive activities. According to the research team’s field survey in the study area, targeted microcredit funds are mainly allocated to productive activities, including agricultural cultivation, livestock and poultry breeding, and small business operations. Drawing on the existing literature (Han et al., 2023), this study categorizes poverty-eradicating households based on their income source into agriculture-oriented and nonfarm-oriented livelihoods. Specifically, agriculture-oriented livelihoods refer to households primarily engaged in agricultural cultivation, livestock and poultry farming, whereas nonfarm-oriented livelihoods include those reliant on off-farm employment and business operations. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 10 present the differential impacts of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households with varying livelihood strategies. The coefficient of targeted microcredit in column (1) is significantly higher than that in column (2), indicating that targeted microcredit strongly affects the economic resilience of households with agriculture-oriented livelihoods.

4.4.2 Heterogeneity of poverty eradication attributes

Due to the influence of various factors, some rural households that have been lifted out of poverty may still face the risk of returning to poverty. As the main assistance measure during the transition period, understanding whether the empowerment effect of targeted microcredit varies among groups with different characteristics is directly related to the adjustment of financial assistance policies in the new era. This paper adopts a standard line of 1.5 times China’s poverty alleviation threshold to categorize the sample households. Households with a per capita disposable income above this threshold are defined as stable poverty-eradicating status, while those below it are classified as unstable poverty-eradicating status. The heterogeneity analysis of poverty alleviation attributes is detailed in columns (3) and (4) of Table 10. The results indicate that targeted microcredit has a more significant empowering effect on the economic resilience of stable poverty-eradicating households than those unstable households. These findings suggest that the Chinese government should further optimize and adjust targeted microcredit policy to better meet the needs of households with varying poverty alleviation attributes in the new era.

5 Discussion

Focusing on the new era following the poverty alleviation campaign, this study analyzes the impact and mechanisms of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. Firstly, this study finds that targeted microcredit significantly impacts the economic resilience of households lifted out of poverty. Our results are consistent with previous studies (Samer et al., 2015; Félix and Belo, 2019), which suggest that targeted microcredit can alleviate liquidity constraints faced by households and serve as an effective coping mechanism against the detrimental impacts of natural disaster shocks (Goodspeed, 2016; Thanh and Duong, 2017). In contrast, the conclusions regarding the long-term effects of targeted microcredit are less consistent with existing literature. Most studies indicate that microcredit generates new livelihood opportunities for poor households and improves their short-term economic conditions, but it does not significantly contribute to long-term sustainability (Bauchet et al., 2015; Nakano and Magezi, 2020) and may even produce adverse effects (Bhuiya et al., 2019; Phan et al., 2023). However, the dynamic effect analysis obtained in this study reveals that the influence of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households has gradually strengthened over time. This finding reveals that targeted microcredit programs in the new era can help poverty-eradicating households achieve sustainable development. Therefore, it is necessary to boost the promotion of targeted microcredit to fully play the long-term empowering role of financial assistance policies. Unlike other market-oriented microcredit programs characterized by high interest rates, targeted microcredit represents a financial poverty alleviation program created by the Government of China for specific beneficiaries and objectives. This project is designed to minimize potential loan risks, thereby reducing financial strain on borrowers (Wu et al., 2024). To achieve this, it is important to refine the risk compensation and sharing mechanisms within targeted microcredit programs.

Secondly, this paper finds that operational income and human capital are significant mechanisms through which targeted microcredit can empower the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households in rural China. This result is generally consistent with existing studies, which suggest that operational income contributes to the sustainability of household asset accumulation, thereby playing a crucial role in fostering resilience against natural disaster shocks (Xu et al., 2024). Furthermore, households possessing higher levels of human capital demonstrate a greater capacity for endogenous development, enabling them to recover more swiftly from the adverse effects of natural disaster shocks, thus enhancing their economic resilience (Islam and Walkerden, 2022). By alleviating financial liquidity constraints faced by poverty-eradicating households, targeted microcredit facilitates the optimal allocation of production factors and augments operational income, thereby strengthening economic resilience (Wu et al., 2024). This result provides insights for optimizing the effectiveness of targeted microcredit in enhancing operational income. Additionally, targeted microcredit can enhance the endogenous development capabilities of poverty-eradicating households and improve the efficiency of credit fund utilization through the enhancement of human capital (Shen and Lu, 2024), thereby further empowering their economic resilience. Therefore, the optimization of targeted microcredit programs should also focus on human capital development to boost inherent development abilities, ultimately empowering the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households.

Given the multidimensional nature of rural households in China, considerable heterogeneity exists in the economic resilience facilitated by targeted microcredit across different dimensions of livelihood strategies and poverty-eradicating attributes. Households with agriculture-oriented livelihoods and stable poverty-eradicating status demonstrate a greater capacity to benefit from targeted microcredit, aligning with the findings of the existing literature (Ding et al., 2024). In the context of comprehensive rural revitalization, these households with agriculture-oriented livelihoods can receive timely government support. In contrast, the limited penetration of credit resources into non-agricultural industries constrains the empowering potential of targeted microcredit for households engaged in off-farm work. Furthermore, households facing unstable poverty-eradicating status are more susceptible to the “welfare dependency” effect of assistance policies, which undermines their endogenous development capacity and makes it challenging to utilize targeted microcredit effectively. The result shows that in the post-poverty eradication era, simply keeping current assistance policies intact is not an effective strategy for confronting sustainable development challenges. It is essential to implement dynamic adjustments that strengthen the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. Therefore, the approach to optimizing financial assistance policies should avoid a blanket application and instead focus on tailoring microcredit resources to fit specific needs.

Although this study presents significant findings, it is not without limitations. Primarily, the research is conducted within the confines of the Liupan Mountains contiguous poverty area, specifically focusing on the Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia provinces (regions). It does not include other provinces (regions) in China with concentrated poverty areas. The regional variability within China may lead to differences in the study to change, but it remains uncertain whether such variations will occur. Therefore, we intend to address this issue in future research by either broadening the geographical scope of our investigation or by utilizing a national survey database of rural households in China. Second, the dataset used in this study consists of short-term panel data (spanning 3 years). This limitation hinders the ability to accurately capture the dynamic changes in the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households and poses challenges in evaluating the long-term effects of targeted microcredit on their economic resilience. Therefore, future studies could track households over multiple periods to examine the circumstances surrounding natural disaster shocks. This method would help in better understanding how economic resilience evolves over the long term. Third, this study elucidates the mechanisms through two channels: operational income and human capital. However, there may be additional pathways through which targeted microcredit influences the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households, warranting further investigation.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

Using data collected from a field tracking study in China’s Liupan Mountains contiguous poverty area from 2021 to 2023, this study constructs the multi-period DID model to investigate the impact of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households in the context of natural disaster shocks. The main conclusions are as follows. First, targeted microcredit significantly enhances the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households, and this effect gradually strengthens over time. Second, targeted microcredit enhances the economic resilience of these households by increasing operational income and human capital. Third, heterogeneity exists in the empowering effects of targeted microcredit on the economic resilience of poverty-eradicating households. Notably, the impact is more substantial among households with agriculture-oriented livelihoods and those maintaining stable poverty-eradicating status.

The above conclusions carry significant policy implications for strengthening the empowering effects of targeted microcredit. First, the government needs to intensify the promotion of targeted microcredit further to enhance effective credit demand, thereby maximizing the empowering impact of such financial instruments on the household’s economic resilience. To this end, the introduction of mobile financial services in impoverished regions is crucial to improving the financial literacy and credit awareness of poverty-eradicating households. Additionally, leveraging digital financial technology to reduce credit transaction costs will stimulate the effective credit demand among these households. Second, policymakers should enhance the effects of targeted microcredit in improving operational income and human capital, thereby reducing dependency on “transfusion-type assistance policies.” Consequently, when implementing targeted microcredit, it is necessary to introduce incentive measures to promote the integration of poverty-eradicating households into industrial development. For instance, improving access to continuing education and bolstering training in modern agricultural production techniques and market sales can contribute to the sustainable development of these households. Third, it is advisable for the government to optimize targeted microcredit in the post-poverty eradication period. By strategically allocating microcredit resources, the government should prioritize households primarily engaged in nonfarm production while also extending additional support to households with unstable poverty-eradicating status. Additionally, the conclusions and recommendations from this study may be applicable to other developing countries that have implemented targeted microcredit programs, offering a reference for them to alleviate household poverty and achieve sustainable development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the (patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin) was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FW: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GQ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. TL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72273106).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 24, 347–364. doi: 10.1191/030913200701540465

Arouri, M., Nguyen, C., and Youssef, A. B. (2015). Natural disasters, household welfare, and resilience: evidence from rural Vietnam. World Dev. 70, 59–77. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.017

Asmamaw, M., Mereta, S. T., and Ambelu, A. (2019). Exploring households' resilience to climate change-induced shocks using climate resilience index in Dinki watershed, central highlands of Ethiopia. PLoS One 14:e0219393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219393

Atara, A., Tolossa, D., and Denu, B. (2020). Analysis of rural households' resilience to food insecurity: does livelihood systems/choice/ matter? The case of Boricha woreda of sidama zone in southern Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. 35:100530. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100530

Baker, M., Gruber, J., and Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. J. Polit. Econ. 116, 709–745. doi: 10.1086/591908

Barrett, C. B., Ghezzi-Kopel, K., Hoddinott, J., Homami, N., Tennant, E., Upton, J., et al. (2021). A scoping review of the development resilience literature: theory, methods and evidence. World Dev. 146:105612. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105612

Bauchet, J., Morduch, J., and Ravi, S. (2015). Failure vs. displacement: why an innovative anti-poverty program showed no net impact in South India. J. Dev. Econ. 116, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.03.005

Beck, T., Levine, R., and Levkov, A. (2010). Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Finance. 65, 1637–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01589.x

Bekele, A. E. (2022). Resilience of Ethiopian agropastoral households in the presence of large-scale land investments. Ecol. Econ. 200:107543. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107543

Bhuiya, M. M. M., Khanam, R., Rahman, M. M., and Nghiem, S. (2019). Microcredit participation and child schooling in rural Bangladesh: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Econ. Anal. Policy 64, 293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2019.09.005

Cheng, X., Chen, J., Jiang, S., Dai, Y., Shuai, C., Li, W., et al. (2021). The impact of rural land consolidation on household poverty alleviation: the moderating effects of human capital endowment. Land Use Policy 109:105692. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105692

Cissé, J. D., and Barrett, C. B. (2018). Estimating development resilience: a conditional moments-based approach. J. Dev. Econ. 135, 272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.04.002

Crépon, B., Devoto, F., Duflo, E., and Parienté, W. (2015). Estimating the impact of microcredit on those who take it up: evidence from a randomized experiment in Morocco. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7, 123–150. doi: 10.1257/app.20130535

Cui, Z., Li, E., Li, Y., Deng, Q., and Shahtahmassebi, A. (2023). The impact of poverty alleviation policies on rural economic resilience in impoverished areas: a case study of Lankao County. China. J. Rural Stud. 99, 92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.03.007

Dardonville, M., Urruty, N., Bockstaller, C., and Therond, O. (2020). Influence of diversity and intensification level on vulnerability, resilience and robustness of agricultural systems. Agric. Syst. 184:102913. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102913

Ding, Z., Fan, X., and Agbenyo, W. (2024). Do low-income households inevitably benefit more from microfinance participation? Evidence from rural China. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 29, 2087–2109. doi: 10.1080/13547860.2023.2204686

Do, M. H. (2023). The role of savings and income diversification in households' resilience strategies: evidence from rural Vietnam. Soc. Indic. Res. 168, 353–388. doi: 10.1007/s11205-023-03141-6

Félix, E. G. S., and Belo, T. F. (2019). The impact of microcredit on poverty reduction in eleven developing countries in south-East Asia. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 53:100590. doi: 10.1016/j.mulfin.2019.07.003

Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 16, 253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

Gao, Q. (2024). The impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural economic resilience. Finance Res. Lett. 66:105679. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.105679

Garcia, A., Lensink, R., and Voors, M. (2020). Does microcredit increase aspirational hope? Evidence from a group lending scheme in Sierra Leone. World Dev. 128:104861. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104861

Goodspeed, T. B. (2016). Microcredit and adjustment to environmental shock: evidence from the great famine in Ireland. J. Dev. Econ. 121, 258–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.03.003

Han, W., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, X. (2023). The impact of farmland transfer participation on farmers' livelihood choices – an empirical study of the effectiveness of the 2014 three property rights separation reform. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 15, 534–562. doi: 10.1108/CAER-12-2021-0236

Herrera-Almanza, C., and Cas, A. (2021). Mitigation of long-term human capital losses from natural disasters: evidence from the Philippines. World Bank Econ. Rev. 35, 436–460. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhaa001

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 1–23.

Huang, W., Ding, S., Song, X., Gao, S., and Liu, Y. (2023). A study on the long-term effects and mechanisms of internet information behavior on poverty alleviation among smallholder farmers: evidence from China. Heliyon 9:e19174. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19174

Islam, R., and Walkerden, G. (2022). Livelihood assets, mutual support and disaster resilience in coastal Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 78:103148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103148

Jacobson, L. S., LaLonde, R. J., and Sullivan, D. G. (1993). Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 83, 685–709.

Jia, X., Xiang, C., and Huang, J. (2013). Microfinance, self-employment, and entrepreneurs in less developed areas of rural China. China Econ. Rev. 27, 94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2013.09.001

Khandker, S. R., and Koolwal, G. B. (2016). How has microcredit supported agriculture? Evidence using panel data from Bangladesh. Agric. Econ. 47, 157–168. doi: 10.1111/agec.12185

Lade, S. J., Haider, L. J., Engström, G., and Schlüter, M. (2017). Resilience offers escape from trapped thinking on poverty alleviation. Sci. Adv. 3:e1603043. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603043

Li, E., Deng, Q., and Zhou, Y. (2022). Livelihood resilience and the generative mechanism of rural households out of poverty: an empirical analysis from Lankao County, Henan Province, China. J. Rural. Stud. 93, 210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.005

Li, H., Liu, M., and Lu, Q. (2024). Impact of climate change on household development resilience: evidence from rural China. J. Clean. Prod. 434:139689. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139689

Li, Y., Wu, W., and Wang, Y. (2021). Global poverty dynamics and resilience building for sustainable poverty reduction. J. Geogr. Sci. 31, 1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11442-021-1890-4

Liu, W., Gerber, E., Jung, S., and Agrawal, A. (2022). The role of human and social capital in earthquake recovery in Nepal. Nat. Sustain. 5, 167–173. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00805-4

Liu, Y., Guo, Y., and Zhou, Y. (2018). Poverty alleviation in rural China: policy changes, future challenges and policy implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 10, 241–259. doi: 10.1108/CAER-10-2017-0192

Liu, Y., and Li, Y. (2017). Revitalize the world's countryside. Nature 548, 275–277. doi: 10.1038/548275a

Loubere, N. (2018). Indebted to development: microcredit as (de)marginalisation in rural China. J. Peasant Stud. 45, 585–609. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1236025

Manyena, B., and Gordon, S. (2015). Resilience, panarchy and customary structures in Afghanistan. Resilience 3, 72–86. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2014.992254

McPeak, J. G., and Little, P. D. (2017). Applying the concept of resilience to pastoralist household data. Pastoralism 7:14. doi: 10.1186/s13570-017-0082-4

Meuwissen, M. P. M., Feindt, P. H., Spiegel, A., Termeer, C. J. A. M., Mathijs, E., De, M. Y., et al. (2019). A framework to assess the resilience of farming systems. Agric. Syst. 176:102656. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102656

Milhorance, C., Le Coq, J.-F., Sabourin, E., Andrieu, N., Mesquita, P., Cavalcante, L., et al. (2022). A policy mix approach for assessing rural household resilience to climate shocks: insights from Northeast Brazil. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 20, 675–691. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2021.1968683

Nakano, Y., and Magezi, E. F. (2020). The impact of microcredit on agricultural technology adoption and productivity: evidence from randomized control trial in Tanzania. World Dev. 133:104997. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104997

Oliphant, W., and Ma, H. (2021). Applying behavioral economics to microcredit in China’s rural areas. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 31:100555. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100555

Phadera, L., Michelson, H., Winter-Nelson, A., and Goldsmith, P. (2019). Do asset transfers build household resilience? J. Dev. Econ. 138, 205–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.01.003

Phan, C. T., Sun, S., Zhou, Z.-Y., Beg, R., and Ramsawak, R. (2023). Does productive microcredit improve rural children's education? Evidence from rural Vietnam. J. Asian Econ. 84:101555. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2022.101555

Quandt, A. (2018). Measuring livelihood resilience: the household livelihood resilience approach (HLRA). World Dev. 107, 253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.024

Samer, S., Majid, I., Rizal, S., Muhamad, M. R., and Rashid, N. (2015). The impact of microfinance on poverty reduction: empirical evidence from Malaysian perspective. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 195, 721–728. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.343

Savari, M., Damaneh, H. E., and Damaneh, H. E. (2023). Effective factors to increase rural households' resilience under drought conditions in Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 90:103644. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103644

Shano, B. K., and Waje, S. S. (2024). Understanding the heterogeneous effect of microcredit access on agricultural technology adoption by rural farmers in Ethiopia: a meta-analysis. Heliyon. 10:e35859. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35859

Shen, J., and Lu, Y. (2024). Innovation in rural finance: Microfinance's impact on prosperity and efficiency in China. J. Knowl. Econ. 16:2155. doi: 10.1007/s13132-024-02155-w

Smith, L. C., and Frankenberger, T. R. (2018). Does resilience capacity reduce the negative impact of shocks on household food security? Evidence from the 2014 floods in northern Bangladesh. World Dev. 102, 358–376. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.003

Su, F., Song, N., Shang, H., and Fahad, S. (2023). Do poverty alleviation measures play any role in land transfer farmers well-being in rural China? J. Clean. Prod. 428:139332. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139332

Tan, X., and Lin, W. (2016). Can poor farmers afford higher micro-credit interest rates than the un-poor? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 8, 100–111. doi: 10.1108/CAER-07-2013-0095

Tan, J., Peng, L., and Guo, S. (2020). Measuring household resilience in Hazard-prone mountain areas: a capacity-based approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 152, 1153–1176. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02479-5

Tarozzi, A., Desai, J., and Johnson, K. (2015). The impacts of microcredit: evidence from Ethiopia. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7, 54–89. doi: 10.1257/app.20130475

Thanh, P. T., and Duong, P. B. (2017). Health shocks and the mitigating role of microcredit—the case of rural households in Vietnam. Econ. Anal. Policy 56, 135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2017.08.006

Urruty, N., Tailliez-Lefebvre, D., and Huyghe, C. (2016). Stability, robustness, vulnerability and resilience of agricultural systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36:15. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0347-5

Volkov, A., Morkunas, M., Balezentis, T., and Streimikiene, D. (2022). Are agricultural sustainability and resilience complementary notions? Evidence from the north European agriculture. Land Use Policy 112:105791. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105791

Wang, R., and Zhao, X. (2023). Can multiple livelihood interventions improve livelihood resilience of out-of-poverty farmers in mountain areas? A case study of Longnan mountain area, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 33, 898–916. doi: 10.1007/s11769-023-1384-7

Wu, B., Niu, L., Tan, R., and Zhu, H. (2024). Multidimensional relative poverty alleviation of the targeted microcredit in rural China: a gendered perspective. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 16, 468–488. doi: 10.1108/CAER-06-2023-0167

Xie, S., Zhang, J., Li, X., Xia, X., and Chen, Z. (2024). The effect of agricultural insurance participation on rural households' economic resilience to natural disasters: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 434:140123. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140123

Xiong, F., and You, J. L. (2019). The impact paths of social capital and the effects of microfinance: evidence from rural households in China? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 11, 704–718. doi: 10.1108/CAER-12-2017-0256

Xu, J., Wang, C., Yin, X., and Wang, W. (2024). Digital economy and rural household resilience: evidence from China. Agric. Econ. Zemědělská Ekon. 70, 244–263. doi: 10.17221/317/2023-AGRICECON

Yao, B., Shanoyan, A., Schwab, B., and Amanor-Boadu, V. (2023). The role of mobile money in household resilience: evidence from Kenya. World Dev. 165:106198. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106198

You, J., and Annim, S. (2014). The impact of microcredit on child education: quasi-experimental evidence from rural China. J. Dev. Stud. 50, 926–948. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2014.903243

Keywords: targeted microcredit, poverty-eradicating households, economic resilience, natural disaster shocks, sustainable development

Citation: Yu Y, Wang F, Qin G and Li T (2025) How does targeted microcredit empower the economic resilience of rural households in the context of natural disasters? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1582487. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1582487

Edited by:

Amar Razzaq, Huanggang Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nugun P. Jellason, Teesside University, United KingdomShowkat Bhat, Symbiosis International University, India

Copyright © 2025 Yu, Wang, Qin and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Li, amd4eWpneHlAeWVhaC5uZXQ=

Yun Yu

Yun Yu Fang Wang

Fang Wang Tao Li

Tao Li