- Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences (DISPOC), University of Siena, Siena, Italy

While global hunger has decreased, particularly in regions traditionally plagued by malnutrition, recent years have seen a rise in food access challenges in countries previously considered immune to such problems. Italy experienced a significant increase in individuals and families requiring food assistance during and after the pandemic. Nevertheless, the primary response to food poverty has been largely left to religious institutions, which have managed the redistribution of food to the most vulnerable segments of the population. Drawing on recent empirical research, this article presents a critical analysis of Italy’s approach to combating food poverty, with a focus on the key characteristics and the role of support services provided by Catholic organizations.

1 Introduction

In recent years, two simultaneous trends have affected the Italian welfare system: a progressive reduction in budgetary allocations, and a shift in the population’s needs, with poverty increasingly affecting segments of the middle class and employed individuals (Ascoli and Pavolini, 2016; Ferragina and Arrigoni, 2021; Busilacchi and Luppi, 2022). Consequently, there has been a rise in the number of families where a single income is no longer sufficient to prevent impoverishment (Saraceno et al., 2020).

As in other European countries (Lambie-Mumford, 2017; Beacom et al., 2020; O’Connell and Brannen, 2021; Penne and Goedemé, 2021; Eurostat, 2024), well before the pandemic period (Maino et al., 2016; Davis and Baumberg Geiger, 2017), food insecurity and poverty had become increasingly important in Italy. Alongside the most serious forms of material deprivation, the various dimensions of food insecurity have also grown. The difficulty in accessing sufficient and quality food for a healthy life, which affects those in conditions of social vulnerability, fuels the so-called paradox of “scarcity in abundance” (Campiglio and Rovati, 2009). This paradox highlights that despite the overabundance of food resources, which are often wasted in the process from production to consumption, the portion of the population unable to secure adequate resources for their livelihood is increasing.

Nevertheless, the policies addressing these issues have mostly been dictated by the emergency and delegated to territorial networks run by various associations (Arcuri et al., 2020; Gori, 2020).

After reconstructing the Italian “model” of combating food poverty through specialized literature, the article analyzes, based on empirical research carried out in the Tuscany region (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Berti et al., 2021; Paletti and Valzania, 2023), its functioning and its transformations over time, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and reflecting on the open scenarios for the future.

The article is organized into four paragraphs. The first frames the topic by analyzing the key characteristics of poverty in Italy. The second reviews the principal European and international policies. The third and fourth paragraphs examine the specificity of the Italian context and its regional system for addressing poverty. Finally, the conclusions propose several critical reflections.

2 The growth of food poverty in Italy before and after the pandemic period

According to Istat (2024), in 2023 Italy registered just over 2.2 million families (8.4% of the total resident families, maintaining the same level as 2022) and nearly 5.7 million individuals (9.7% of the total resident individuals, consistent with the previous year) living in conditions of absolute poverty.1 Notably, recent years have witnessed a consistent rise in food poverty, particularly affecting families already experiencing absolute poverty (Fondazione Banco Alimentare, 2022; Caritas, 2021).

As is well-established, Istat measures food poverty through a combination of indicators that assess various facets of this issue, including limited access to food, economic difficulties, social isolation, and the specific nutritional requirements of both children and adults. Among these indicators, the material deprivation index, which considers the lack of access to a substantial meal every other day, and the social deprivation index, which records the inability to participate in social activities centered around food, are of primary importance.

Data from Istat (2023) indicate that between 2019 and 2022, approximately 4.4 million individuals (7.5% of the population aged 16 and over) experienced material deprivation, while 2.4 million (4.8%) faced social deprivation. These figures reveal a particular severity in the Southern regions and the islands, where 3.1 million people live in food poverty. The material hardship faced by these families has significant repercussions, especially concerning the health of minors (ActionAid, 2022; Palladino et al., 2024). Indeed, in Italy, 13.5% of the population under the age of 18 (amounting to 1.346 million children and adolescents) lives in absolute poverty and is directly vulnerable to food poverty (Caritas, 2021). This deprivation predominantly manifests in insufficient food portions for daily nutritional needs, an inadequate and/or poorly diversified diet, and a lower prevalence or earlier termination of breastfeeding.

Qualitatively, the multidimensional nature of poverty (Saraceno et al., 2020) is particularly striking, highlighting the complex interplay of variables that contribute to impoverishment and widen inequalities across Italy’s regions.

A significant aspect is the rapidly changing profile of food poverty compared to the past. Increasingly, those suffering from food insecurity or the inability to eat adequately include a growing segment of the population impoverished by the worsening economic crisis and the pandemic emergency. Today, the “new” poor also encompass the unemployed, precarious workers, and individuals with weak social networks who quickly find themselves, often defenseless and psychologically unprepared, to face emergencies and new needs. Among the most critical situations are large families—predominantly of foreign origin (especially people who came from Africa and Asia)—with weak relational networks or those relying almost exclusively on family ties, which prove less effective in times of need.

The pandemic phase has clearly exacerbated the general situation. Food insecurity has intensified due to increasing economic hardship, the suspension of school activities, and the loss of work income for many families. This has led to a growing prevalence of single women or women with dependent children, due to their greater social fragility and the difficult conciliation between work and life times, as well as individuals with jobs but insufficient income to avoid insecurity and food poverty (Caritas, 2021; ActionAid, 2022).

3 An overview about the main policies

In recent years, the EU has aimed to update its food strategies in line with sustainability principles. Within the European Green Deal, which outlines the path to making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, the “Farm to Fork” strategy holds a central role. This strategy addresses the transition to a sustainable food system, offering benefits for both producers—in terms of income and economic advantages—and consumers—in terms of food access and positive impacts on the health and well-being of European citizens (European Union, 2020).

Currently, the discussion surrounding food sovereignty and democracy has intensified, partly as a response to escalating issues of food insecurity and poverty. It has become increasingly clear that there’s a strong connection between the right of communities to shape their own agricultural and food policies and the capacity to ensure access to healthy, culturally appropriate food produced through sustainable methods (Dekeyser et al., 2018; Sampson et al., 2021).

While awaiting the tangible effects of this strategy, many European countries continue to grapple with food insecurity and poverty. According to the Eurostat (2024) data, in 2023, 9.5% of the EU population could not afford a meal containing meat, fish, or a vegetarian equivalent every 2 days, nearly three percentage higher than in 2019 (6.8%). In the most recent EU member states, such as Bulgaria and Romania, these figures reach alarming levels, exceeding 20%. However, even Germany and France (13.3 and 12.2% respectively), while Italy stands at 8.4% and Spain at 6.4%.

These food insecurity issues have yet to receive adequate responses from national public policies. Although the situations are incomparable to those in some African and Asian countries, the fight against food insecurity even in wealthy European nations remains unsatisfactory. Interventions are often under-resourced and follow emergency-driven, sector-specific approaches, as evidenced by the worsening of the phenomenon during the pandemic crisis (Hple, 2021; Pawlak et al., 2024).

An analysis of international literature and a review of poverty reduction initiatives, including those implemented at the local level, reveal two distinct approaches. The first, more traditional and widespread, is a typically charitable approach carried out through food banks and other interventions by associations and private entities, often with religious affiliations. Specifically, charitable organizations step in to fill gaps in the public social safety net and address basic food needs (Poppendieck, 1998; McIntyre et al., 2016; Caraher and Furey, 2018). While indispensable, these approaches have limitations. One primary risk is that individuals are viewed as merely “mouths to feed” (McAll et al., 2015) rather than as recipients of structural interventions capable of dismantling the reproduction of unequal social relations. Furthermore, these approaches can foster dependency and stigmatization, and may not guarantee a balanced diet that is also appealing to the recipients. Research conducted in Norway, the Netherlands, and Greece during the pandemic-related food emergency highlighted two additional issues: firstly, charitable interventions linked to food bank systems heavily rely on private sector donations, which can limit their capacity to address the underlying causes of food insecurity; secondly, these actions often depend on the involvement of elderly volunteers (Warshawsky, 2023).

The second approach encompasses a variety of local initiatives that combine addressing food needs with inclusive and participatory policies. An interesting example in this regard is the case of Barcelona, as described by Magaña-González et al. (2023). The alternative practices adopted in some areas of Barcelona aim to move beyond a purely welfare-based logic through the active involvement of beneficiaries. This seeks to reduce dependence on food assistance programs and foster autonomy and self-management. The objective of these alternative practices, exemplified by the “Cuina Més amb Menys” project, is to transition away from emergency responses and create sustainable long-term solutions by integrating food production, distribution, and consumption within a community context. This approach also allows for a focus on food quality rather than solely on quantity. Similar projects have been developed in Brussels (Damhuis et al., 2020) and Mulhouse (Villet and Ngnafeu, 2020), with the goal of overcoming charitable practices and adopting participatory and inclusive approaches. To achieve these objectives in Brussels, community gardens were established for self-production of food, and tool and seed exchange programs for cultivation were initiated. In both Brussels and Mulhouse, efforts have been made to teach new food practices and encourage socialization through communal cooking.

Even in Italy, a comprehensive policy specifically targeting food poverty remains absent. Over the years, challenges in accessing food have been incorporated into broader poverty reduction policies (Gori, 2020). Consequently, alongside resources from the FEAD (Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived), the most prevalent approach remains the traditional charitable model based on soup kitchens for the poor and the distribution of food packages (Maino et al., 2016). Only in recent years have innovative projects aimed at moving beyond mere food distribution gained traction, with the emergence of urban agriculture initiatives and collective purchasing groups, for instance.

4 How to combat food poverty: the role of catholic associations

Drawing directly on researches conducted in Tuscany by the University of Siena (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Berti et al., 2021; Paletti and Valzania, 2023),2 and comparing the results with those of similar research carried out in other regions of Italy (Bottiglieri et al., 2016; Marotta, 2020; Felici et al., 2022), this paragraph presents an overview of the ways food poverty is addressed in Italy.

A fundamental aspect shared across all examined territorial contexts, albeit with some specific variations, is that food poverty is tackled locally by a network of associations within the social private sector. In particular, associations affiliated with the Catholic Church have increasingly filled the void left by the State and have become central hubs within a broader network of actors. This network also includes local public institutions and other associative and volunteer organizations (Caritas, 2021). These are characterized by their proximity and territorial closeness to families experiencing social vulnerability, and their role involves monitoring, prevention, as well as intervention in cases of need (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Berti et al., 2021; Paletti and Valzania, 2023).

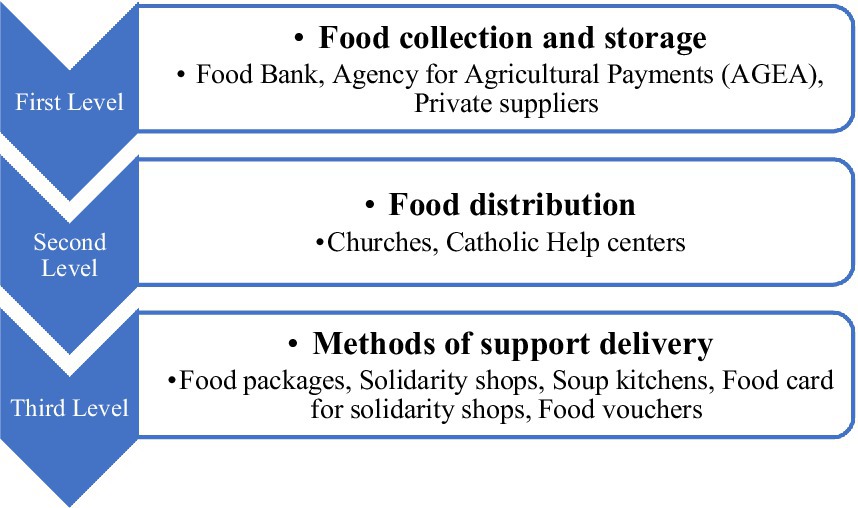

The system’s operation hinges on territorial specificities—regional variations, where some associations wield greater political influence than others, or local dynamics, generally stronger in large cities and less so in smaller towns. Its daily practice, with some exceptions, unfolds through three phases: the collection and storage of food; the transit of food through distribution centers across different territories; and the varied distribution of food, often through coexisting methods. Within this framework, food support services can also be categorized into three distinct levels of intervention (see Figure 1).

These approaches naturally address different needs (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Paletti and Valzania, 2023). Food parcels—typically prepared by staff and volunteers—offer an initial and immediate response to requests for assistance, delivered with varying frequency depending on factors such as the quantity of food included. Similarly, though targeting a different user group, soup kitchens provide an immediate solution to the urgent need for a hot meal and an opportunity to interact with staff, volunteers, and other users. Soup kitchens primarily serve a particularly marginalized population, often comprising homeless individuals or those living in inadequate housing where cooking is not feasible. In fact, soup kitchens cater to people in situations of extreme marginality (70% of beneficiaries experience precarious employment, while 45% are homeless), playing a vital role in providing a hot meal to anyone in need.

Solidarity Emporiums, in contrast, are free distribution points for food (and other items) where access is generally granted after an interview with social workers. Food vouchers also represent a response provided by social workers and are issued to individuals who meet the eligibility criteria outlined in the regulations (Berti and Valzania, 2020).

Compared to other intervention methods, Solidarity Emporiums operate according to a distinct philosophy (Maino et al., 2016). While their primary objective is to serve as a stable and visible point of reference for the population to find support when needed, they also aim to move beyond the predominantly welfare-based approach of simply distributing food. This latter method, despite its undeniable practical effectiveness, can often risk creating dependency among beneficiaries without empowering them to achieve autonomy and overcome their situation of need. Furthermore, the Emporium seeks to minimize—as much as possible3—the stigmatization processes that are a frequent issue with the delivery of food parcels.

To achieve these goals, these spaces strive to replicate a setting similar—both in terms of their external appearance and the perception created among users—to that of a regular supermarket. Within this environment, beneficiaries are enabled to select the goods necessary for their sustenance while preserving their personal dignity. In recent years, Solidarity Emporiums have faced a degree of overlap with the “Reddito di cittadinanza” (Citizenship Income) and the issuance of food vouchers, often also facilitated by Caritas itself, for direct use in supermarkets (Paletti and Valzania, 2023). Nevertheless, they remain arguably the most progressive approach within the intervention system against food poverty and in support of the most vulnerable population.

Furthermore, during the approximately 2 years when the health emergency disrupted and slowed down all activities, the Food Bank, Caritas Listening Centers, and the broader network of Solidarity Emporiums—often in collaboration with social services—managed not only to provide traditional forms of assistance but also to diversify their interventions. They broadened their scope of action to include individuals and families who were seeking this type of help for the first time. The pandemic and the need for physical distancing inevitably altered the operational methods of these services. Key changes included Emporiums being compelled to function as providers of pre-packaged shopping parcels to avoid gatherings, reducing the frequency of distribution while increasing the size of the parcels, and operating primarily by appointment. This phase amplified existing trends, such as the expanding and diversifying segment of the population facing hardship, necessitating a more complex response and effectively requiring operators, predominantly volunteers, to devise innovative ways to compensate for the inability to provide in-person assistance.

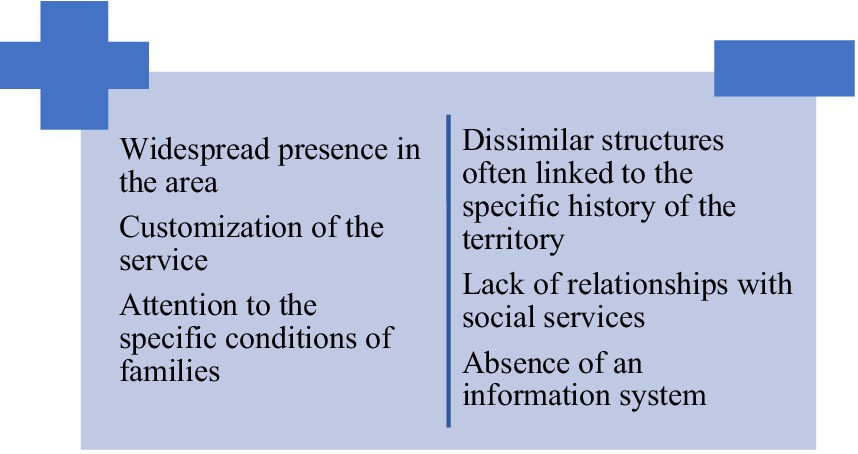

This system for combating food poverty demonstrably has both strengths and weaknesses (Maino et al., 2016; Berti and Valzania, 2020). Among its most commendable aspects is undoubtedly the widespread presence of intervention structures across the territory, starting with the network of Churches and parishes. This network provides a foundational level of initial aid upon which more extensive services can be built. Furthermore, Caritas Centers and the network of Solidarity Emporiums have—often in synergy with social services—successfully diversified their interventions, broadening their reach to include individuals and families seeking assistance for the first time. This has enhanced their ability to tailor responses to actual needs (see Figure 2).

However, the very widespread presence of aid structures at the local level can paradoxically also be viewed as a negative aspect (Paletti and Valzania, 2023). While it is positive in terms of facilitating easy access to services and ensuring personalized attention through listening (the customization of responses), thanks to the involvement of volunteers, it becomes negative when it is excessively shaped by the history of individual territories, leading to an overly uneven overall organizational structure. The network of Solidarity Emporiums, in fact, appears to be poorly institutionalized (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Berti et al., 2021). There is no structured system of relations between the various Emporiums, and the system’s functioning relies heavily on individual interpersonal connections. The primary risk is that the replacement or turnover of a single person can have even systemic repercussions; as said us one of the leaders of Emporium of Prato “everything is very much tied to the individual person…if a person changes, the service itself risks failing…or in any case the relationships between the various Emporiums change”. Another critical point of this “model” is the often discontinuous and unformalized relationship with local administrations. In particular, the collaboration between Caritas and the network of public social services needs strengthening. Social services primarily refer individuals needing food aid to Caritas, while Caritas can report situations of fragility or complexity requiring more structured intervention to social services. It is perhaps in this neglected and underdeveloped connection that one of the major weaknesses of the entire system lies. Often, the system appears too fragmented between a public sphere, where social services mainly play an informational role for people in need, and the associative sphere, where the actual provision of assistance takes place: “this is one of the major critical issues of the social system in Tuscany…we hope that in the next years the situation will improve and there will be a greater link between public services and Caritas services” (Councillor for Social Policies—municipality of Firenze).

The beneficiaries also highlighted several critical areas for improvement (Paletti and Valzania, 2023). Among the most significant, the need to: increase food education courses for families to enhance their skills; increase the availability and variety of fresh food products such as meat, fish, and vegetables; encourage greater attention to child food poverty by increasing the availability of products specifically for or suitable for early childhood; evaluate the possibility of increasing the availability of products for individuals with specific nutritional needs due to their health conditions (e.g., celiac disease, diabetes, food intolerances, cardiovascular diseases, etc.); and increase the use of food vouchers.

5 Some final considerations

Specialized literature has long emphasized that, alongside moving beyond the notion that hunger is solely a problem of developing nations, the fight against food poverty in wealthy Western countries is, in fact, approached through two distinct and often conflicting paradigms: the charitable approach and the human rights approach (Riches and Silvasti, 2014).

Charitable measures focus on alleviating hunger through food donations and aid, whereas the right to food recognizes access to adequate sustenance as a fundamental human right, necessitating structural policies and long-term interventions to tackle the underlying causes of hunger.

In Italy—although some national anti-poverty policies, such as the Citizenship Income, have played a significant role—the struggle against food poverty primarily unfolds through fragmented, territorially-based actions, often emergency-driven, and managed almost exclusively by Catholic associations (Maino et al., 2016; Arcuri et al., 2020). A welfare-oriented approach prevails, characterized by short-term interventions that do not address the structural determinants of food poverty, much less the broader issue of the right to food. This is not to say that the system currently operated by Catholic associations does not yield significant actions in combating the phenomenon (Berti and Valzania, 2020; Berti et al., 2021); on the contrary, as also emerged from the opinions expressed in the interviews within our research, it seems crucial to emphasize the importance—indeed, the necessity—of a service capable of offering human connection and timely responses to needs that often cannot wait.

Within this similar framework, and with national resources allocated to these policies decreasing, the potential future scenarios are essentially twofold: short-to-medium term and long term.

In the immediate and near future, it is advisable to pursue two complementary strategies: first, to strengthen the existing infrastructure by increasing the resources of the FEAD and exploring other potential alternative measures (private donations, initiatives to combat food waste, etc.). This would aim to ensure widespread territorial coverage and a greater variety of products offered by the various local structures, while also encouraging the establishment of social emporiums over simple food parcel distribution. Second, given the multidimensional nature of poverty, it is crucial to further develop the integration between policies and, above all, between services (both public and private social services), linking food poverty interventions to broader social inclusion initiatives.

In the long term, on the other hand, it would be beneficial to promote complementary or even preventative actions that go beyond the current system, aligning with the concept of the right to food and a fundamental transformation of the system. In this regard, alongside enhanced education on food and food waste, it would be necessary to bridge the gap between producers and consumers. This could make access to food less dependent on its commodification and, more generally, promote and expand self-production initiatives to a greater extent than has been done so far.

On the strictly economic front, a testable instrument, as is known, is a guaranteed minimum income (or universal basic income). This involves the provision of a subsidy to all citizens regardless of their income or employment status, with the aim of ensuring a minimum level of subsistence. This measure could also build upon the legacy of the so-called “purchase card,” or the direct transfer of money (€40 per month) onto a dedicated credit card for use in major food retail outlets, promoting greater stability for a measure that has demonstrated its effectiveness while also reducing stigma.

Author contributions

FB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The incidence of individual relative poverty is slightly increasing, reaching 14.5% from 14.0% in 2022, involving almost 8.5 million individuals. The incidence of absolute poverty among families with at least one foreign national stands at 30.4%, while it is significantly lower at 6.3% for families composed solely of Italian citizens. The incidence of relative family poverty, at 10.6%, remained stable compared to 2022, encompassing over 2.8 million families below the relative poverty threshold.

2. ^All these researches aimed to assess whether, and under which specific conditions, the implemented policies effectively support beneficiaries in improving their social circumstances. To address this objective, these studies adopted a predominantly qualitative methodology, with particular emphasis on collecting rich, contextual data. The core data collection method consisted primarily—though not exclusively—of biographical interviews. This technique allows for the extraction of key narrative elements from participants’ life histories, highlighting events they deem crucial to understanding their current situations (Mayer and Tuna, 1990). Given the challenges in identifying suitable participants, the research team convened six targeted meetings with local stakeholders, including professionals from both public and private social service sectors. These engagements proved instrumental in refining the sample and gathering contextual insights. Two research phases, conducted between 2018 and 2021, yielded a total of 40 in-depth interviews with social workers and 40 semi-structured questionnaires completed by users of social grocery programs. The most recent phase, carried out in 2022 and focused exclusively on recipients of soup kitchen services, collected 150 completed questionnaires.

3. ^Although requiring the display of an identification card at the entrance (on which an equivalent value expressed in points, not money, is pre-loaded), the intention is for individuals to feel more freedom in filling their shopping cart.

References

ActionAid (2022). Cresciuti troppo in fretta. Gli adolescenti e la povertà alimentare in Italia, Milano.

Arcuri, S., Brunori, G., and Galli, F. (2020). “The role of food charity in Italy” in The rise of food charity in Europe. eds. H. Lambie-Mumford and T. Silvasti (Bristol: Policy Press).

Ascoli, U., and Pavolini, E. (2016). The Italian welfare state in a European perspective: a comparative analysis. London: Policy Press.

Beacom, E., Furey, S., Hollywood, L., and Humphreys, P. (2020). Investigating food insecurity measurement globally to inform practice locally: a rapid evidence review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 3319–3339. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1798347

Berti, F., Bilotti, A., and Valzania, A. (2021). La povertà alimentare in Toscana. Strumenti di contrasto e possibili ricadute sul benessere e la salute delle persone. Salute Soc. 2, 169–183. doi: 10.3280/SES2021-002012

Berti, F., and Valzania, A. (2020). Food poverty in Tuscany: local public policies and (good) practices. Anthropol. Food 15. doi: 10.4000/aof.11165

Bottiglieri, M., Pettenati, G., and Toldo, A. (2016). Toward Turin food policy. Good practices and visions. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Busilacchi, G., and Luppi, M. (2022). When it rains, it pours. The effects of the Covid-19 outbreak on the risk of poverty in Italy. Rass. Ital. Soc. 1, 11–34. doi: 10.1423/103179

Campiglio, L., and Rovati, G. (2009). Il paradosso della scarsità nell’abbondanza: il caso della povertà alimentare. Milano: Guerini and Associati.

Caraher, M., and Furey, S. (2018). The economics of emergency food aid provision. A financial, social and cultural perspective. London: Palgrave Pivot.

Damhuis, L., Serré, A., and Rosenzweig, M. (2020). Concrétiser l’ambition démocratique de l’alimentation durable? Expérimentations bruxelloises dans l’aide alimentaire. Anthropol. Food 15. doi: 10.4000/aof.11372

Davis, O., and Baumberg Geiger, B. (2017). Did food insecurity rise across Europe after the 2008 crisis? An analysis across welfare regimes. Soc. Policy Soc. 16, 343–360. doi: 10.1017/S1474746416000166

Dekeyser, K., Korsten, L., and Fioramonti, L. (2018). Food sovereignty: shifting debates on democratic food governance. Food Secur. 10, 223–233. doi: 10.1007/s12571-017-0763-2

European Union (2020) Farm to Fork strategy. For a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. European Commission Paper

Eurostat (2024). Inability to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish (or vegetarian equivalent) every second day

Felici, F. B., Bernaschi, D., and Marino, D. (2022). La povertà alimentare a Roma: una prima analisi dell'impatto dei prezzi. Roma: Cursa.

Ferragina, E., and Arrigoni, A. (2021). Selective neoliberalism: how Italy went from dualization to liberalisation in labour market and pension reforms. New Polit. Econ. 26, 964–984. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2020.1865898

Hple (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition: developing effective policy responses to address the hunger and malnutrition pandemic. Hple issue paper. Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/5d230f39-ad95-47c4-a23e-471c07953223/content

Magaña-González, C. R., Piola, E., Llobet, M., Muñoz, A., and Duran, P. (2023). Towards a social transformation of food assistance models: possibilities and challenges of alternative practices in Barcelona and its metropolitan area. Auton. Loc. Serv. Soc. 2, 295–318. doi: 10.1447/108279

Maino, F., Lodi Rizzini, C., and Bandera, L. (2016). Povertà alimentare in Italia: le risposte del secondo welfare. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Mayer, K., and Tuna, B. (1990). Event history analysis in life course research. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

McAll, C., Van de Velde, C., Charest, R., Roncarolo, F., McClure, G., Dupéré, S., et al. (2015). Inégalités sociales et insécurité alimentaire. Réduction identitaire et approche global. Revue du Cremis 8. On line published

McIntyre, L., Tougas, D., Rondeau, K., and Mah, C. L. (2016). “In”-sights about food banks from a critical interpretive synthesis of the academic literature. Agric. Hum. Values 33, 843–859. doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9674-z

Paletti, F., and Valzania, A. (2023). La povertà alimentare in Toscana: una ricerca qualitativa sugli utenti dei centri Caritas. Autonomie locali e servizi sociali. 2, 279–294. doi: 10.1447/108278

Palladino, M., Cafiero, C., and Sensi, R. (2024). Understanding adolescents’ lived experience of food poverty. A multi-method study among food aid recipient families in Italy. Glob. Food Secur. 41:100762. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2024.100762

Pawlak, K., Malak-Rawlikowska, A., Hamulczuk, M., and Skrzypczyk, M. (2024). Has food security in the EU countries worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic? Analysis of physical and economic access to food. PLoS One 19:e0302072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302072

Penne, T., and Goedemé, T. (2021). Can low-income households afford a healthy diet? Insufficient income as a driver of food insecurity in Europe. Food Policy 99:101978. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101978

Riches, G., and Silvasti, T. (Eds.) (2014). First world hunger revisited: food charity or the right to food? London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Sampson, D., Cely-Santos, M., Gemmill-Herren, B., Babin, N., Bernhart, A., Bezner Kerr, R., et al. (2021). Food sovereignty and rights-based approaches strengthen food security and nutrition across the globe: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:686492. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.686492

Saraceno, C., Benassi, D., and Morlicchio, E. (2020). Poverty in Italy: features and drivers in a European perspective. London: Policy Press.

Villet, C., and Ngnafeu, M. (2020). Se positionner aux côtés des personnes Des expériences alsaciennes en sécurité alimentaire, entre réduction identitaire et reconnaissance sociale. Anthropol. Food 15. doi: 10.4000/aof.11230

Keywords: food poverty, Catholic associations, Italy, Tuscany, food support services

Citation: Berti F and Valzania A (2025) Less state and more solidarity shops: the Italian method to combat food poverty. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1596425. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1596425

Edited by:

Manjeet Singh Nain, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaCopyright © 2025 Berti and Valzania. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabio Berti, ZmFiaW8uYmVydGlAdW5pc2kuaXQ=

Fabio Berti

Fabio Berti Andrea Valzania

Andrea Valzania