- College of Ocean and Agricultural Engineering, Yantai Institute of China Agricultural University, Yantai, China

The increasing demand for natural flavor enhancers and functional food ingredients has driven interest in Lentinus edodes (shiitake mushrooms), which are rich in proteins and bioactive compounds. This study optimized the enzymatic hydrolysis of L. edodes using various proteases and response surface methodology. Single-factor experiments were conducted, and flavor protease was identified as the most effective enzyme. The optimal hydrolysis conditions were 50.268°C, 5.23% material ratio, and 223.64 kU/100 g protease dosage, with a predicted amino acid nitrogen raise ratio of 268.908%. Validation tests gave an average of 267.6 ± 0.7%, with <5% deviation. After hydrolysis, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and alanine increased, enhancing umami and sweetness. Essential amino acids such as lysine, valine, and isoleucine also rose significantly. Antioxidant activity was confirmed by DPPH and ·O₂- scavenging, with IC₅₀ values of 2.536 and 2.013, respectively. These results demonstrate that enzymatic hydrolysis is a promising approach to improve both the taste and nutritional value of L. edodes, supporting its application in natural seasoning and functional food development.

1 Introduction

Global population growth and climate change challenge traditional food systems, with food demand projected to rise by 50% by 2050, thus raising expectations for the development and supply of bio-based proteins. Animal proteins are popular for their essential amino acids but impose a severe environmental burden, with livestock farming occupying 77% of agricultural land and accounting for over 30% of greenhouse gas emissions (Petrescu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023). Fungal proteins, due to their nutritional, physiological, and functional benefits, present a promising alternative protein source (Li et al., 2023).

Lentinus edodes, commonly known as the shiitake mushroom, is the most widely consumed edible fungus in China, prized for its nutritional and flavor qualities (Wang et al., 2017). It is also the second most cultivated edible mushroom globally, often referred to as the “Queen of Mushrooms” (Chen et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2022; Ahmad et al., 2023). Lentinus edodes contains a variety of nutritional compounds and bioactive substances, including polysaccharides, proteins, fibers, vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber, trace elements, ergosterol, and vitamins (B1, B2, C) (Li et al., 2014; Morales et al., 2020; Sheng et al., 2021), among others. Additionally, the 5′-nucleotides in L. edodes can mask salty, sour, bitter, and fishy tastes. Among these, 5′-guanylic acid, when added to amino acid-based flavor enhancers, can amplify umami intensity by dozens to hundreds of times, making it a renowned powerful flavor enhancer. These compounds not only contribute to the nutritional value of L. edodes but also enhance its unique flavor while providing physiological benefits, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antifungal properties (Reis et al., 2017). Moreover, L. edodes protein is rich in both essential and non-essential amino acids (Xu et al., 2024). Its amino acid composition is comparable to that of animal protein (Gopal et al., 2022).

Various physical (Hwang et al., 2021) and chemical methods are commonly employed to process protein in L. edodes, including enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation, chemical extraction, and synthesis (Chen et al., 2021; Prandi et al., 2023; Zhang L. et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023). However, physical disruption methods, such as mechanical grinding, ultrasound treatment, or pressure homogenization, often lead to denaturation or degradation of sensitive proteins (Krishnarjuna and Ramamoorthy, 2022). Chemical methods, including detergents or solvents, can dissolve cell wall components but may compromise protein activity or purity (Goldberg, 2021). Among these, enzymatic hydrolysis is a low-cost, safe, and environmentally friendly approach widely used in the food industry (Du et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023). During protein hydrolysis, proteases recognize and bind to the R groups of amino acid residues on either side of the peptide bond via steric hindrance. Conformational changes in the R groups of certain amino acids lead to peptide bond cleavage (Datta et al., 2017). Consequently, L. edodes proteins can be degraded by cellulases and proteases into free peptides and amino acids, which significantly contribute to the mushroom’s unique flavor and taste profile (Gao J. et al., 2021). Additionally, the hydrolysates exhibit various bioactivities in vitro, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities (Agaricus bisporus and its by-products as a source of valuable extracts and bioactive compounds, 2019), effectively enhancing functional properties, and nutritional characteristics. There were some studies reported on the extraction and functional properties of edible fungi proteins, including those from Agaricus bisporus, and Stropharia rugosoannulata, etc. as well as the functional properties of L. edodes proteins (Ramos et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2024). However, few studies have employed data analysis methods to optimize the hydrolysis process of L. edodes.

In this study, L. edodes was used as the raw material, with amino acid nitrogen raise ratio as the key evaluation indicators. The extraction process of L. edodes protein was optimized using response surface methodology. The functional properties of L. edodes hydrolysate were analyzed, and its amino acid composition was evaluated. This research provides a theoretical basis for the development and utilization of high value-added L. edodes.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Preparation of Lentinus edodes hydrolysate

2.1.1 Screening of proteases

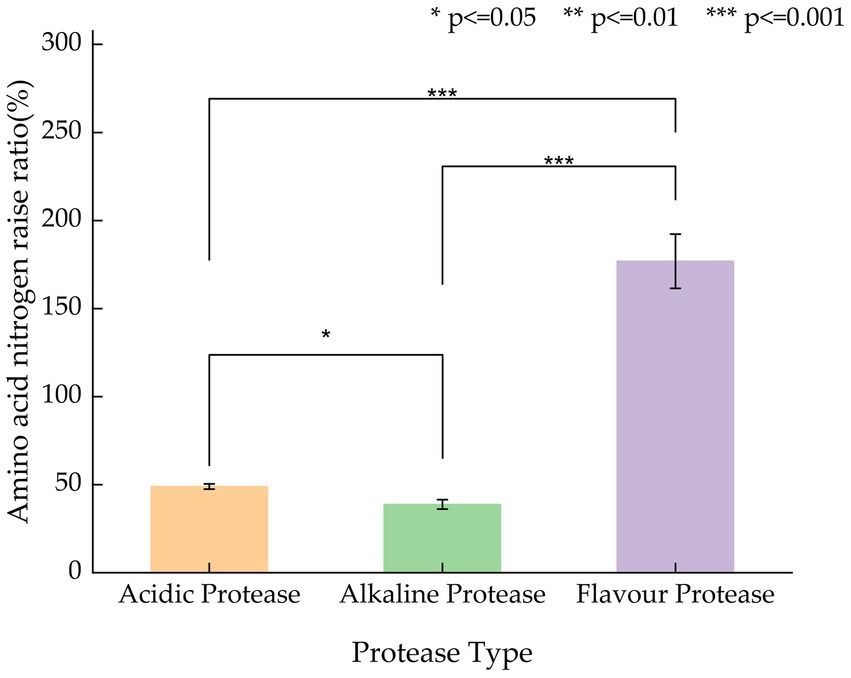

The hydrolysis degree of L. edodes protein is related to the type of enzyme. The effect of different proteases on the amino acid nitrogen content of L. edodes enzymatic hydrolysates is shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, the hydrolysis degree of different protease hydrolysates is significantly different (p < 0.05), among which the hydrolysis degree of flavor protease hydrolysates is extremely different from that of alkaline protease and acidic protease (p < 0.01). Flavor protease has the best hydrolysis effect. Compared with the control group without enzyme, the amino acid nitrogen content increased by an average of 176.8%; the hydrolysis effect of alkaline protease and acidic protease is relatively poor, and the amino acid nitrogen content increased by less than 40% compared with the control.

The selection of these three enzymes—acidic protease, alkaline protease, and flavor protease—was based on their differing optimal pH ranges and substrate specificities. Acidic protease (optimal pH 3–5) is effective for denatured protein hydrolysis; alkaline protease (optimal pH 9–11) is suitable for degrading structural proteins; while flavor protease (optimal pH 6–8) is widely used in food applications for producing taste-active peptides, including those contributing to umami and sweetness (Du et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2022). The superior performance of flavor protease in this study is likely attributed to its combined endo- and exopeptidase activity, which facilitates the release of small peptides and free amino acids.

Additionally, other proteases such as papain, bromelain, and neutrase have been re-ported to effectively hydrolyze plant or fungal proteins in other contexts, contributing to improved functional and flavor properties. These may serve as promising alternatives for future optimization (Wen et al., 2020).

Therefore, flavor protease was selected as the most suitable enzyme for enzymatic hydrolysis of L. edodes and applied in the following steps.

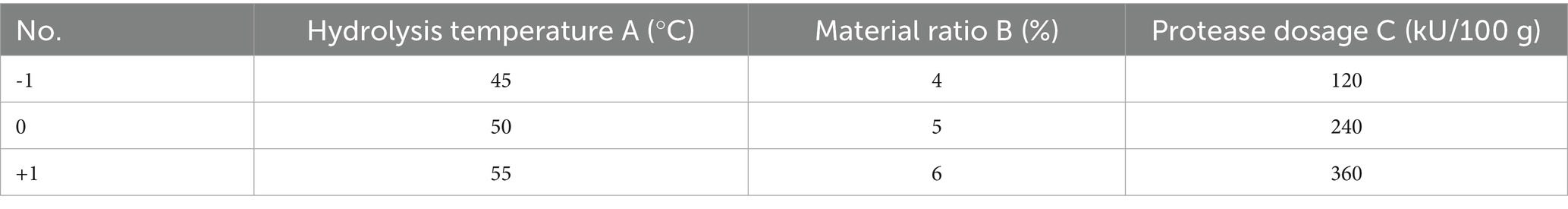

2.1.2 The effect of hydrolysis temperature

With the increase of temperature, the content of amino acid nitrogen showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing (p < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2A. The amino acid nitrogen raise ratio in the hydrolysis was the highest at 50°C, because the enzyme showed the highest enzymatic activity in the optimal temperature range. After 50°C, the content of amino acid nitrogen begins to decrease, because too high temperature will cause enzyme denaturation and inactivation. Therefore, in the response surface experiment, the enzymatic hydrolysis temperature is set at 50°C is the center value.

Figure 2. The optimization of parameters of L. edodes hydrolysis: (A) Hydrolysis temperature, (B) Material ratio, (C) Protease dosage, and (D) Hydrolysis time. Different letters in the same indicators indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

2.1.3 The effect of material ratio

As shown in Figure 2B, as the proportion of the extract increases, the degree of hydrolysis gradually increases. When the material ratio reaches 1:20, the degree of hydrolysis is the highest. When the extract continues to increase, the degree of hydrolysis shows a downward trend. This is because the increase in the extract reduces the contact point between the substrate and the enzyme molecule, and the enzymatic efficiency decreases. When the substrate concentration is too high, the viscosity of the substrate affects the full contact between the enzyme and the substrate, and the enzymatic efficiency decreases. This corroborates Zhang et al.’s assertion that a low material ratio may lead to excessively high protein concentrations, which can affect the fluidity of the system and the interaction between the enzyme and substrate (Zhang Y. et al., 2023). Therefore, 1:20 is selected as the optimal material ratio for enzymatic hydrolysis of L. edodes.

2.1.4 The effect of protease dosage

When the addition amount increases from 120 kU/100 g to 240 kU/100 g, the degree of hydrolysis increases (Figure 2C); when the amount of enzyme added continues to increase, the degree of protein hydrolysis decreases. Therefore, 240 kU/100 g is selected as the optimal amount of protease added.

2.1.5 The effect of hydrolysis time

As shown in Figure 2D, the amino acid nitrogen content gradually increased with the extension of time. Before 1.5 h, the rising rate was relatively large (p < 0.05), and it tended to be flat before 2.5 h (p > 0.05) but still rose slowly, indicating that the enzymatic reaction was close to the end. This may be because the substrate concentration gradually decreased with the extension of time, and when the substrate was completely hydrolyzed, the enzymatic activity ended. Therefore, considering the cost factor and to avoid edge effects, the enzymatic hydrolysis time can be directly determined at 2 h.

2.2 Results of response surface experiment

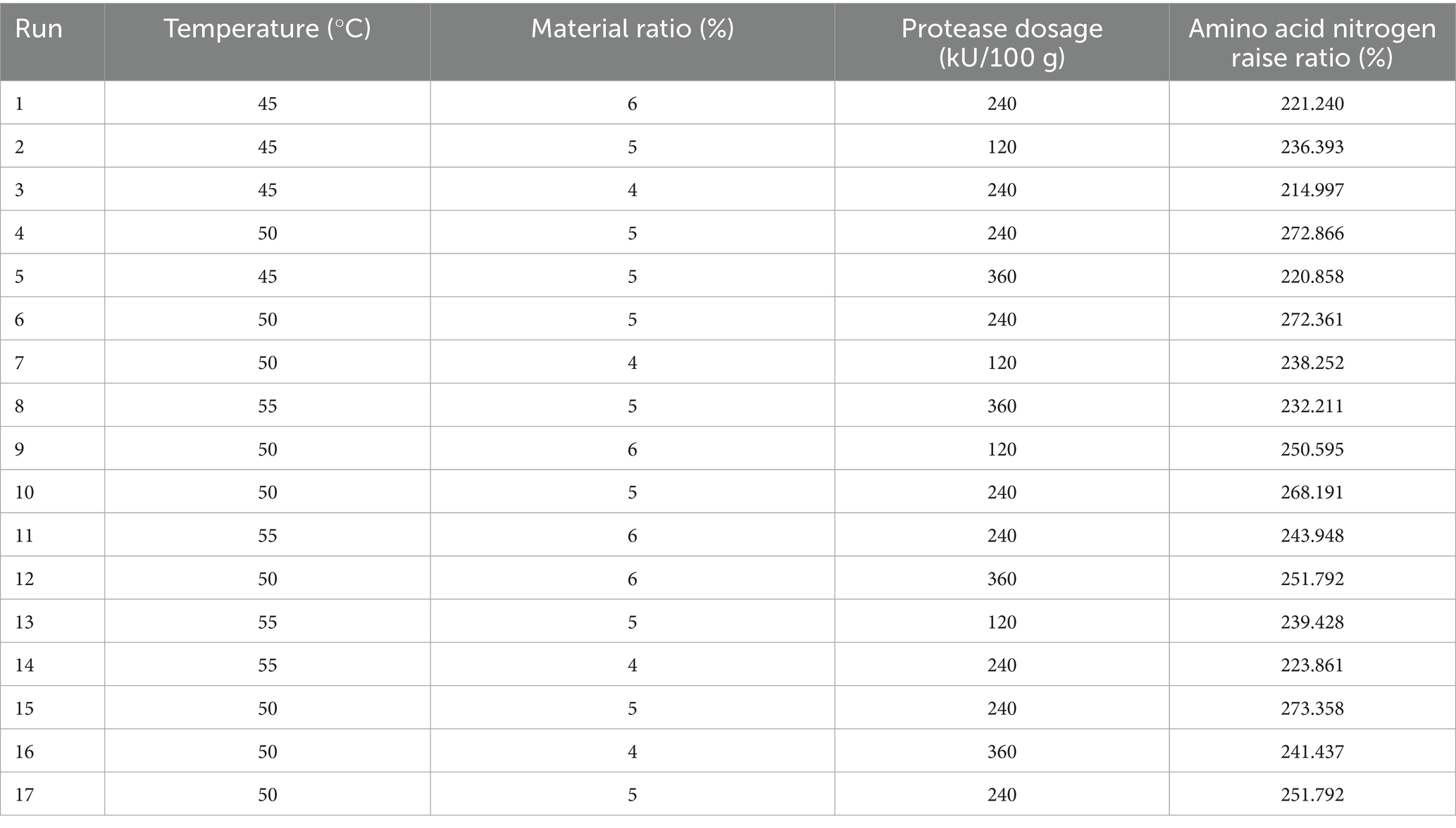

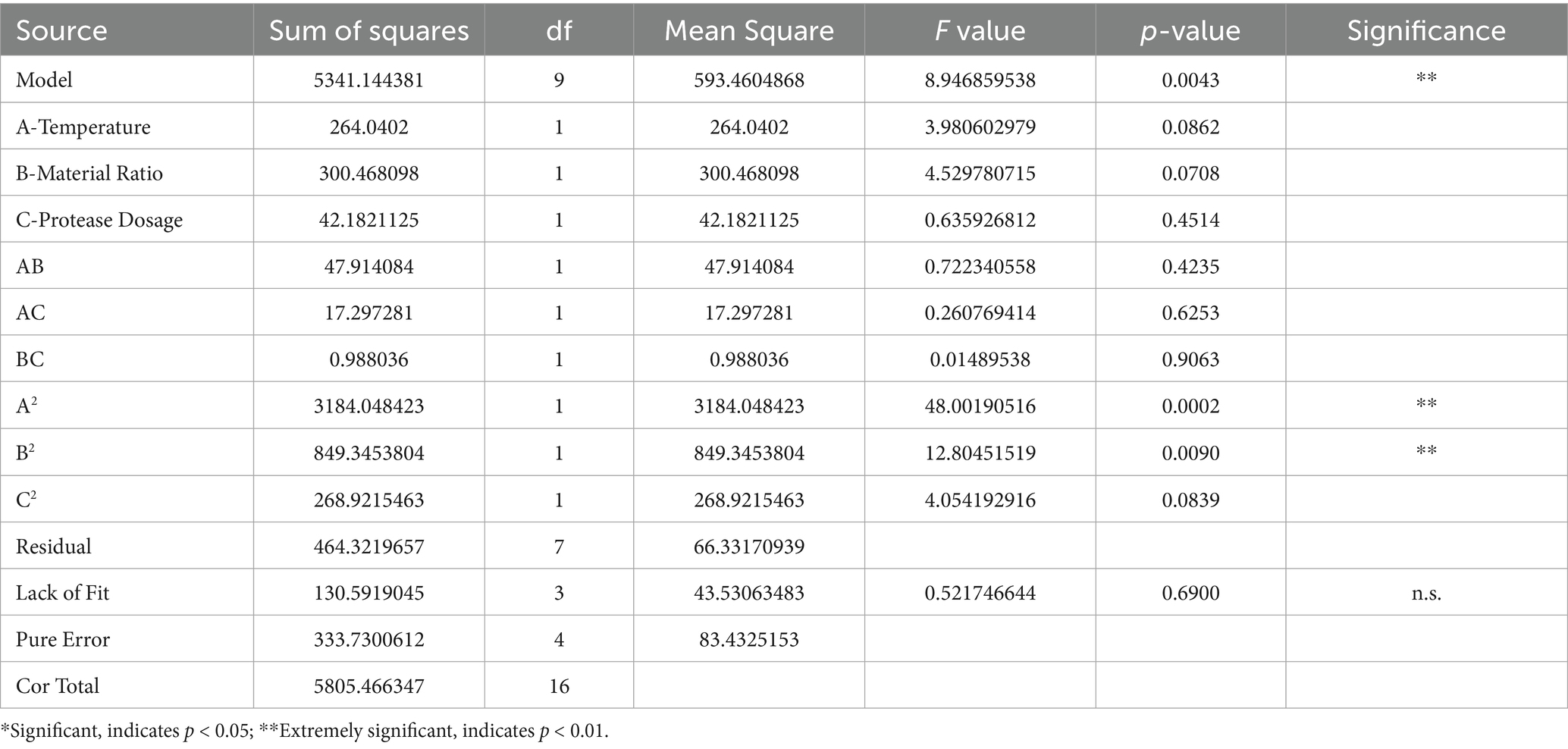

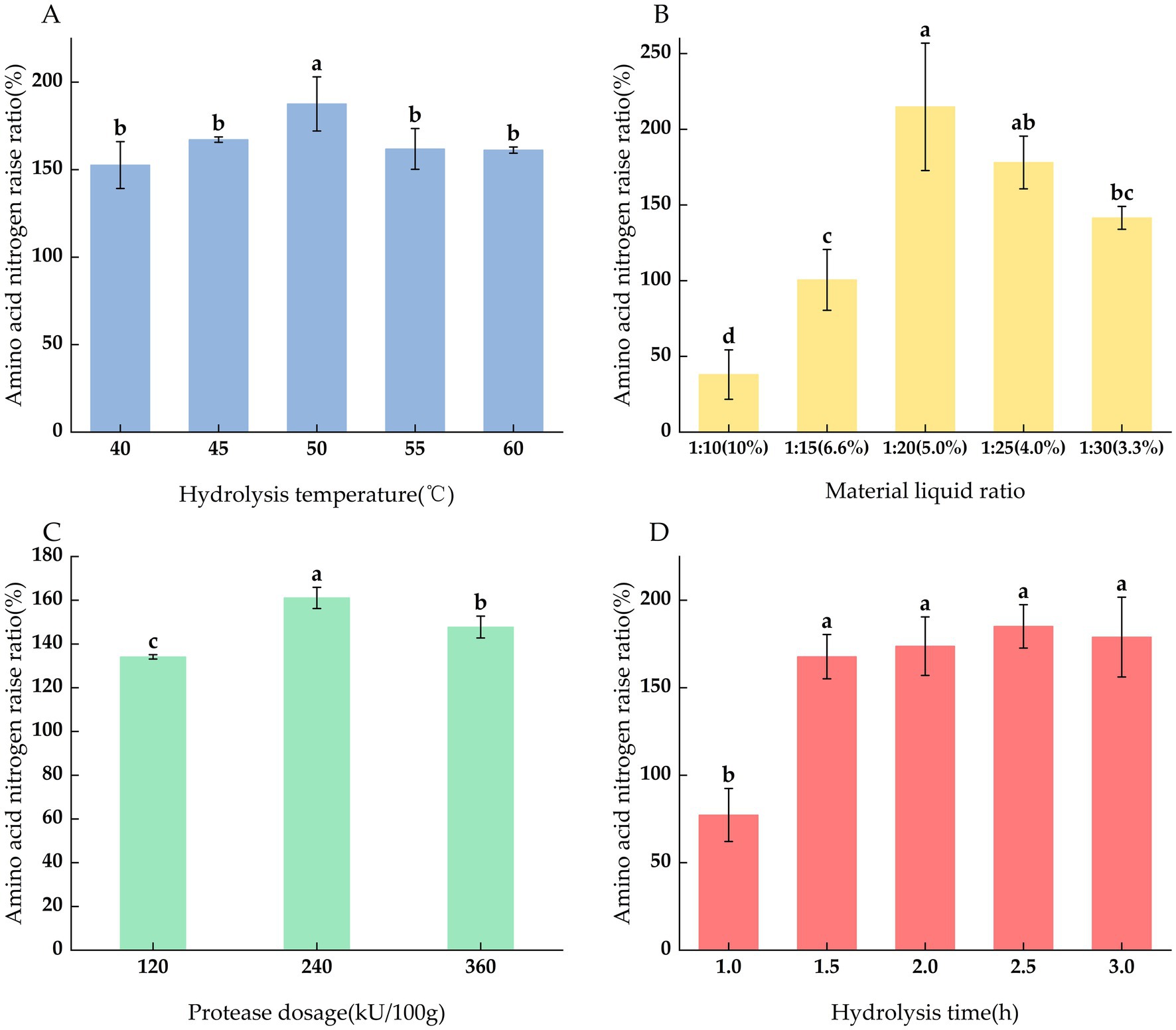

There is a certain interaction between the various factors in the hydrolysis process. Referring to the results of single factors, three factors, namely, hydrolysis temperature, enzyme addition and material ratio, were selected to determine the optimal process. The central composite design was adopted to establish a mathematical model. The result analysis is shown in Tables 1, 2.

The equation shows the variation between the enzymatic amino acid content and each factor. The response surface results show that the p value of the model is less than 0.05, indicating that the model factor level terms are generally significant, the model level is extremely significant (p < 0.01), the F value of the lack of fit term is not significant, and the equation fit is good. The correlation coefficient R2 = 0.9200, that is, 92% of the response value changes can be represented by this model. Based on the above parameters, the experimental method is reliable, and the regression model can be used to analyze the experimental results instead of the actual experimental point.

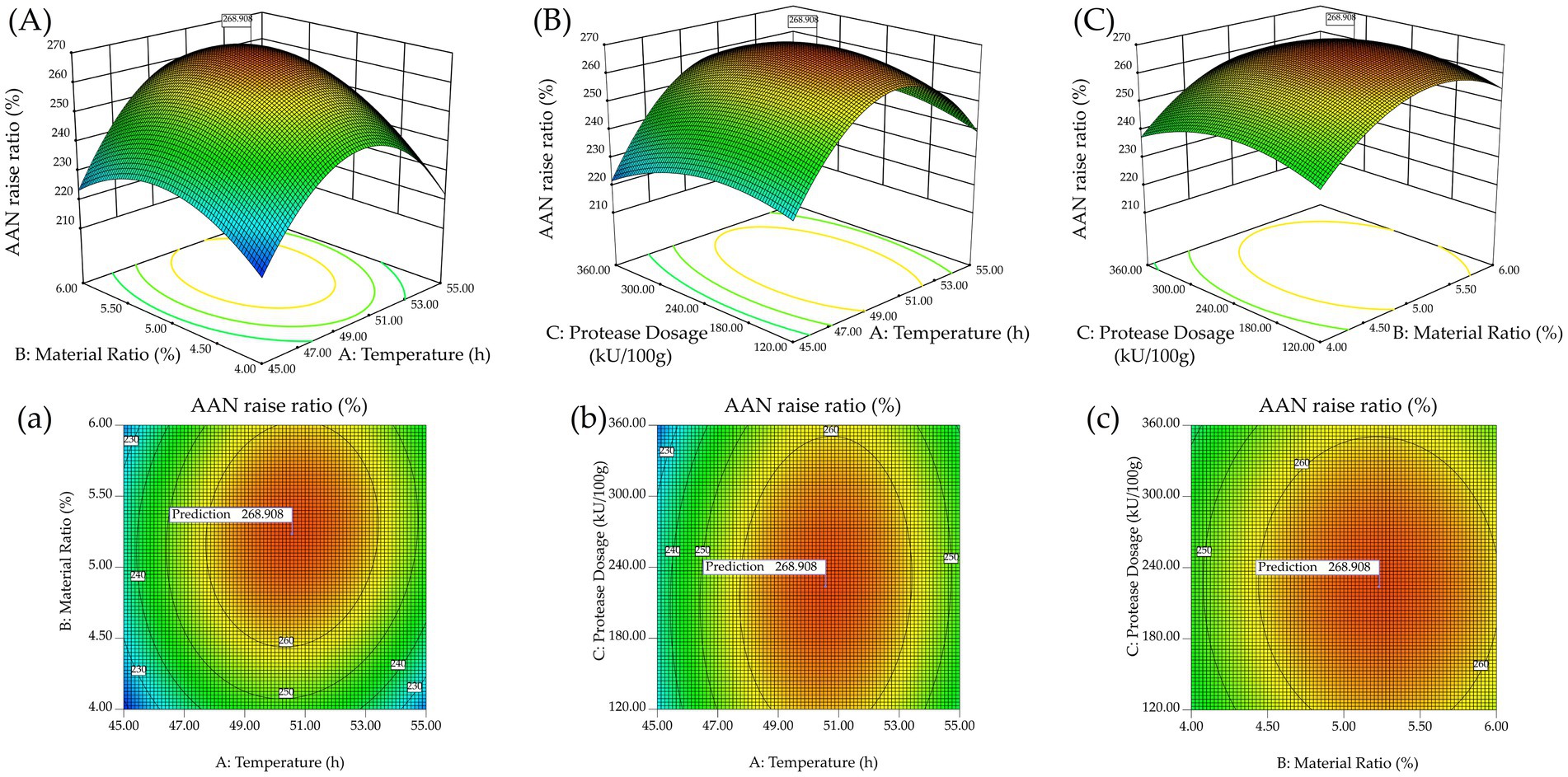

2.2.1 Response surface analysis of interaction

As shown in Figure 3A and Figure 3a, it can be observed that when the material-to-liquid ratio is low or the temperature is relatively low, the contour lines are denser, while at higher temperatures or higher material-to-liquid ratios, the contour lines are more widely spaced. This secondly corroborates Zhang et al.’s assertion (Zhang Y. et al., 2023). Therefore, lower material-to-liquid ratios or lower temperatures have a more pronounced effect on the degree of hydrolysis, while higher temperatures or higher material ratios have a lesser impact.

Figure 3. The effect of the interaction between factors on amino acid nitrogen raise ratio. 3D surface graphs: (A) Temperature and Material Ratio, (B) Temperature and Protease Dosage, (C) Material Ratio and Protease Dosage; Contour graph: (a) Temperature and Material Ratio, (b) Temperature and Protease Dosage, (c) Material Ratio and Protease Dosage.

2.2.2 Predicted result and validation of the optimized hydrolysis process

The optimal enzymatic hydrolysis conditions for L. edodes were predicted through regression equations. It’s optimization yielded a material ratio of 5.23%, a temperature of 50.268°C, a protease dosage of 223.64 kU/100 g, and a predicted AAN raise ratio of 268.908%. Under the consideration of practical operability, the optimal extraction process was refined to involve an hydrolysis temperature of 50°C, a material ratio of 5.2%, and a protease dosage of 223 kU/100 g. Six replicate validation experiments were conducted according to the revised optimal process conditions, yielding an average hydrolysis degree of 267.6 ± 0.7%. The absolute deviation between this value and the theoretical prediction was less than 5%, and the results of a t-test indicated no significant difference, thereby further validating the reliability of the model.

2.3 Results of free amino acid compositions

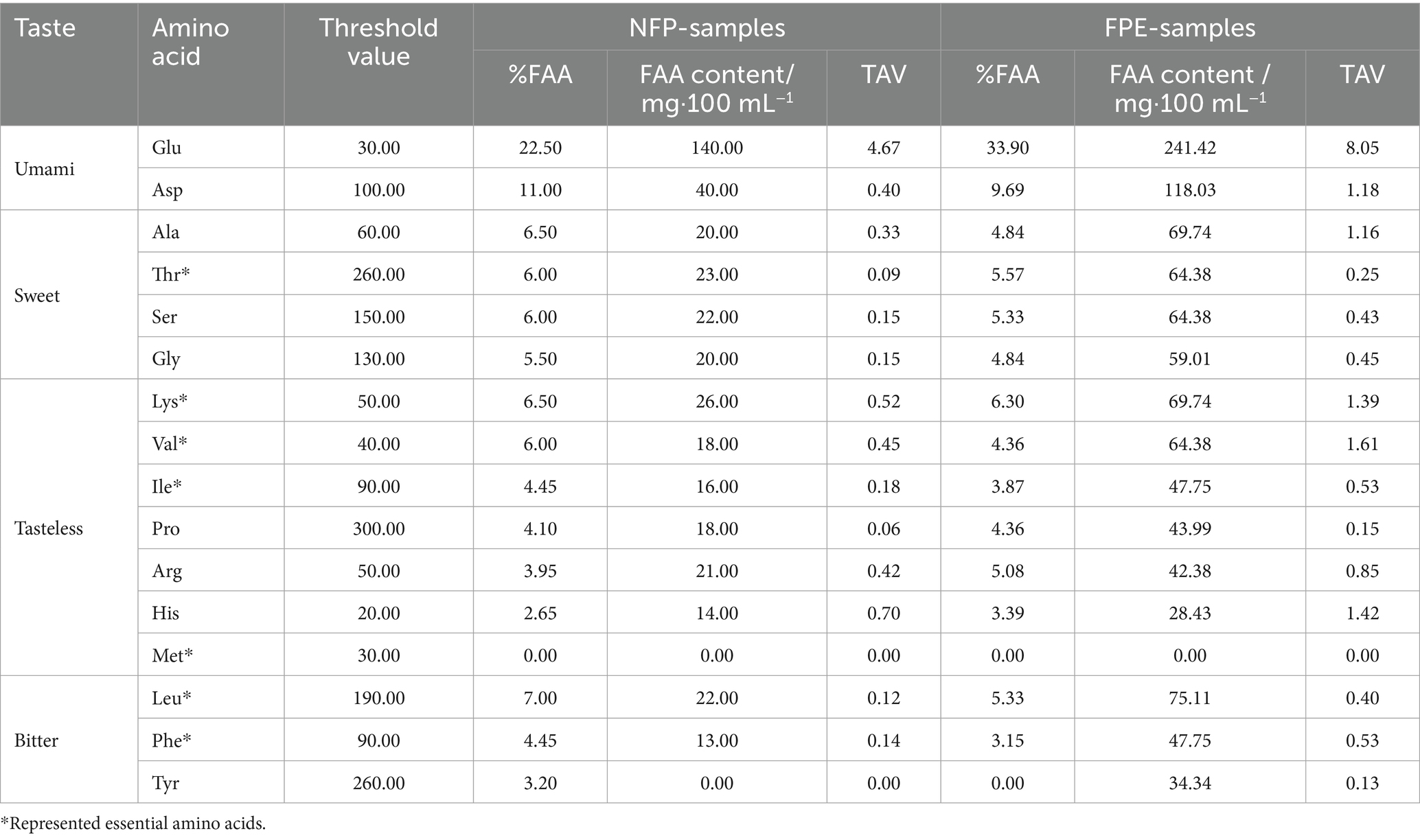

The Taste Activity Value (TAV) theory is used to quantify the contribution of individual compounds, such as amino acids, to the overall taste profile of a product. This theoretical framework is particularly useful for assessing the flavor characteristics of foods before and after processes such as enzymatic hydrolysis (Gao H. et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024). TAV is calculated using the following formula:

When the TAV of a compound is greater than 1 (TAV > 1), it indicates that the compound is present at a concentration exceeding its sensory threshold, meaning its taste is perceptible and contributes to the overall flavor. Conversely, if the TAV is less than 1 (TAV < 1), the compound’s concentration is below its sensory threshold, making it unlikely to influence the flavor profile.

In the analysis of free amino acids, various taste phenotypes are commonly used to classify them. Based on the classification methods of Cai et al. (2024), Bachmanov et al. (2016), and Chen et al. (2022), this study adopts the approach outlined in Table 3 to categorize the taste phenotypes of free amino acids. The threshold values for TAV calculations were derived from the research conducted by Liu et al. (2019).

Post-hydrolysis, the flavor profile of the product becomes markedly more prominent in umami and sweetness, while bitterness remains subdued. Glutamic acid (Glu) and aspartic acid (Asp), key contributors to umami flavor, show substantial increases in FAA content from 140.00 mg·100 mL−1 to 241.42 mg·100 mL−1 and from 40.00 mg·100 mL−1 to 118.03 mg·100 mL−1, respectively, elevating their TAVs to 8.05 and 1.18. This rise underscores a more pronounced umami taste post-hydrolysis. Similarly, alanine (Ala) exhibits a TAV exceeding 1, signaling a perceptible sweetness, with FAA content rising from 20.00 mg·100 mL−1 to 69.74 mg·100 mL−1. Bitter-tasting amino acids, such as leucine (Leu), phenylalanine (Phe), and tyrosine (Tyr), though increased in FAA content, do not reach TAV thresholds that impart a strong bitterness. This aligns with the findings of Poojary et al. (2017), who demonstrated that enzyme-assisted extraction is a promising method for enhancing the recovery rate of umami-related amino acids from mushrooms.

Additionally, the nutritional quality is enhanced, evidenced by the significant elevation in essential amino acids (EAAs) such as Lysine (Lys), Valine (Val), and Isoleucine (Ile). Lysine, which is crucial for protein synthesis and collagen formation (Matthews, 2020), rises from 26.00 mg·100 mL−1 to 69.74 mg·100 mL−1. Valine and Isoleucine, both vital for muscle recovery and metabolism (Mann et al., 2021), also increase markedly to 64.38 mg·100 mL−1 and 47.75 mg·100 mL−1, respectively. The overall FAA content indicates an enhanced nutritional profile post-hydrolysis, contributing both to the flavor intensity and the health benefits of the product.

2.4 Results of in vitro antioxidant test

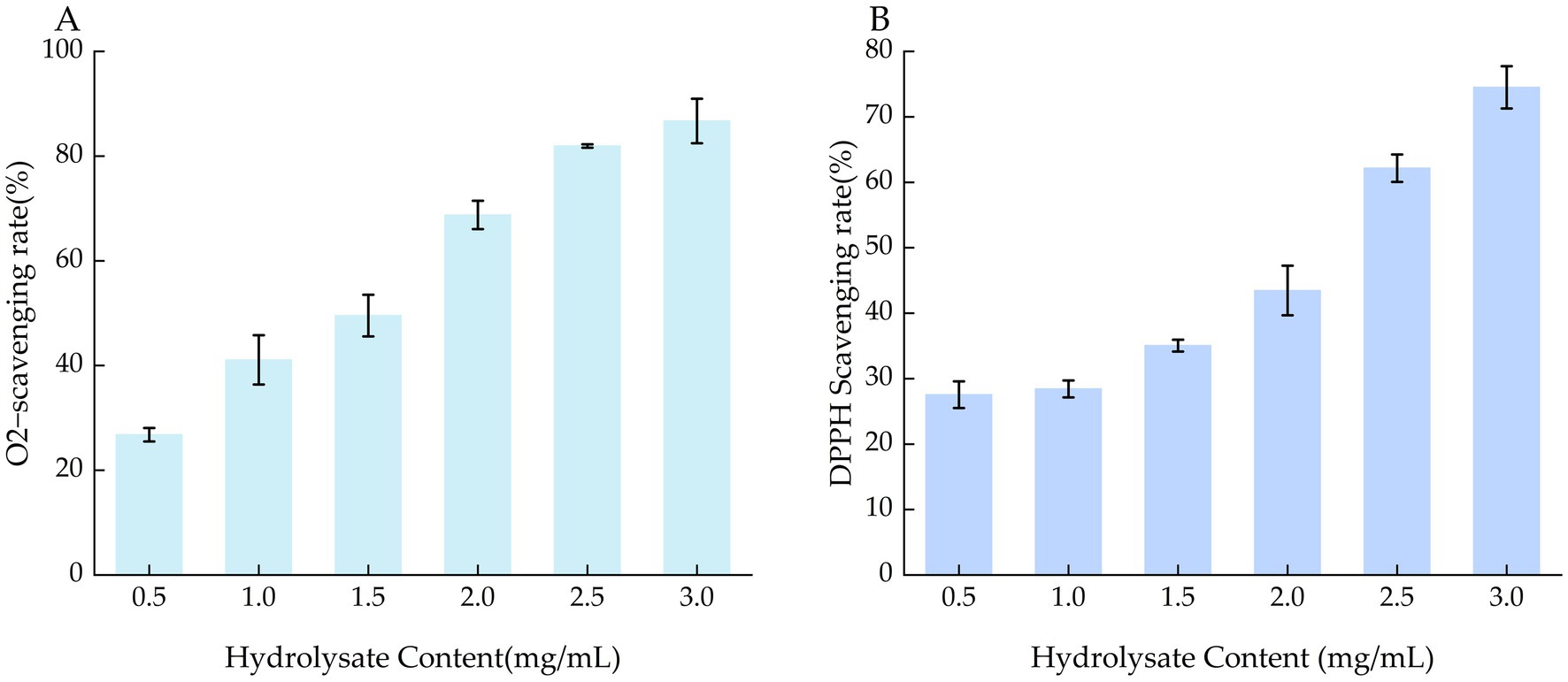

2.4.1 Determination of ·O₂− scavenging ability

The ·O₂− scavenging ability of L. edodes hydrolysates solutions at different concentrations exhibited a clear dose–response relationship, with higher hydrolysate content corresponding to increased ·O₂− scavenging rates (Figure 4A). These results indicate that the concentration of L. edodes hydrolysates solutions significantly affects their ·O₂− scavenging ability. Using the same analytical method as described above, the IC50 for ·O₂− was determined to be 2.013.

2.4.2 Determination of DPPH scavenging ability

As shown in Figure 4B, the DPPH radical scavenging ability of with different hydrolysate content increased with concentration. L. edodes hydrolysate solutions with high concentration had high free radical scavenging rates. This indicated that the concentration of L. edodes hydrolysates had a high impact on DPPH scavenging ability. By using GraphPad Prism IC50 was calculated as 2.536. This indicates that L. edodes hydrolysates has strong antioxidant properties. The results are significantly superior to those of extracts from various wild mushrooms (Bolesławska et al., 2024).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Materials

The fresh L. edodes was obtained from e-commerce platforms.

Acid protease (49,049 U/g) was obtained from Novozymes Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nan’jing, China). Alkaline protease (577,179 U/g) and flavor protease (336,859 U/g) were obtained from Wanbo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Zheng’zhou, China).

3.2 Preparation of Lentinus edodes powder

Place the fresh L. edodes into a 60°C dryer and dry in hot air until constant weight. Using a grinder, the dried mushroom roe was ground into powder and passed through a standard sieve with a pore size of 0.2 mm. The sieved fines are selected and stored in a sealable bag in a cool and dry place.

3.3 Preparation of Lentinus edodes hydrolysate

3.3.1 Hydrolysis process

Add buffer solution to the mixture of powder and water with a total mass of 16 g to adjust to the optimum pH range of the corresponding protease. Then the protease was added, mixed thoroughly and hydrolyzed by heating in a shocked water bath. Finally, the mixture was placed in a water bath at 95°C and kept for 15 min to kill the protease activity. At the end, Cooling to room temperature and centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 min was performed to obtain the supernatant. The obtained supernatant is the hydrolysate.

3.3.2 Screening of proteases

Three kinds of proteases, acidic protease, flavored protease and alkaline protease, were analyzed to hydrolyze L. edodes proteins. The experimental steps were as follows: 1 g of L. edodes powder was added into 15 mL of distilled water, mixed thoroughly, and then adjusted to the optimal pH range of the corresponding proteases, and then 1% of alkaline protease, flavor protease and acid protease with equal enzyme activity units, were added, mixed thoroughly, and then adjusted the mass to 20 g. L. edodes were hydrolyzed at the optimal temperature for 2 h. The optimal proteases for hydrolysis of L. edodes proteins were selected according to the increase of amino acid nitrogen content.

3.3.3 Single-factor experiment

Based on the study conducted by Zhou et al. (2024) and Bing et al. (2024), the range of individual hydrolysis parameters was determined with subsequent modifications and improvements. The hydrolysis process of Lentinula edodes was studied using flavor protease, and the effects of material ratio, enzyme dosage, hydrolysis temperature and hydrolysis time on the hydrolysis effect were investigated.

3.3.3.1 The effect of protease dosage

Under the conditions of material ratio of 1:15, hydrolysis temperature of 45°C and enzymatic hydrolysis time of 2 h, the protease dosage were 120 kU/100 g, 240 kU/100 g and 360 kU/100 g, respectively, to investigate the effect of protease dosage on the AAN raise ratio.

3.3.3.2 The effect of hydrolysis temperature

Under the conditions of solid–liquid ratio of 1:15, protease dosage of 120 kU/100 g, and hydrolysis time of 2 h, the enzymatic hydrolysis temperatures were, 40°C, 45°C, 50°C, 55°C and 60°C, respectively, and the effect of hydrolysis temperature on the AAN raise ratio was investigated.

3.3.3.3 The effect of hydrolysis time

Under the conditions of solid–liquid ratio of 1:15, the protease dosage were 120 kU/100 g, and hydrolysis temperature of 35°C, the hydrolysis times were 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h, 2.5 h and 3 h respectively, and the effect of hydrolysis temperature on the AAN raise ratio was investigated.

3.3.3.4 The effect of material ratio

Under the conditions of protease dosage of 120 kU/100 g, hydrolysis temperature of 35°C and hydrolysis time of 2 h, the material liquid ratio was set to 1:10, 1:15, 1:20, 1:25 and 1:30 respectively, and the effect of the material ratio on the AAN raise ratio was investigated.

3.3.4 Response surface experimental design

Based on the outcomes of the single-factor experiments, enzyme hydrolysis temperature (A), material-to-liquid ratio (B), and enzyme dosage (C), which significantly influenced the degree of hydrolysis, were selected as independent variables. The AAN increase ratio was chosen as the response variable for the Box–Behnken experiment. A three-factor, three-level experimental design was formulated and analyzed using Design Expert 8.0.6 software. The coded factor levels are presented in the Table 4.

3.4 Determination of amino acid nitrogen raise ratio

Amino acid nitrogen reflects the degree of hydrolysis of proteins (Luan et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2024). The content of amino acid nitrogen in the hydrolysates was determined following the procedure outlined in Section 11.3 of the GB 5009.235–2016 standard, titled “National Food Safety Standard: Determination of Amino Acid Nitrogen in Food”. The amino acid nitrogen raise ratio (AANrR) was calculated using the following formula, (Equation 1), based on the principles provided in the aforementioned national standard:

3.5 Determination of free amino acids compositions

A 4 mL sample was mixed with 1 mL of 5-sulfosalicylic acid and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter. The contents of free amino acids in the supernatant were determined using an automatic amino acid analyzer (L-8900; Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Kowalska et al., 2022).

3.6 In vitro antioxidant test

3.6.1 Determination of ·O2− scavenging ability

The superoxide anion (·O₂−) scavenging ability of L. edodes hydrolysates was assessed using the method described by Esfandi et al. (2024). The O₂− scavenging rate was calculated according to the following formula (Equation 2):

3.6.2 Determination of DPPH scavenging ability

The DPPH scavenging ability of L. edodes hydrolysates was determined using Karami’s method (Karami et al., 2019). The DPPH scavenging rate was calculated according to the following formula (Equation 3):

3.7 Statistical analysis

The test data were analyzed for variance using SPSS 22 statistical software. Multiple comparisons were conducted employing Duncan’s method, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Response surface analysis was performed using Design-Expert 8 software, and all graphs were generated with Origin 2024b software. Data were averaged from the results of three repeated experiments.

4 Conclusion

In this study, enzymatic hydrolysis was applied to convert macromolecular proteins in L. edodes into free amino acids and peptides, thereby improving its flavor and nutritional profile. Flavor protease exhibited the best hydrolysis performance. The process increased umami and sweet amino acids while keeping bitter and tasteless amino acids below their sensory thresholds, enhancing overall taste. The resulting amino acid profile closely resembled the FAO/WHO model, satisfying essential amino acid requirements and demonstrating notable antioxidant (Song et al., 2024). Given the rising demand for natural food seasonings, hydrolyzed L. edodes has strong market potential, especially as a base for compound seasonings (Ismail-Fitry and Ang, 2019; Xu et al., 2022). Moreover, antioxidant peptides derived from plant proteins offer advantages over synthetic additives, including cost-effectiveness, safety, and sustainability (Wen et al., 2020). Hence, L. edodes-based seasonings can also serve to reduce the need for additional preservatives due to their inherent preservative properties.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

BZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. XW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. TQ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. QD: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. HW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Shandong Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System Edible Fungi Innovation Team, grant number SDAIT-07-14.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, I., Arif, M., Xu, M., Zhang, J., Ding, Y., and Lyu, F. (2023). Therapeutic values and nutraceutical properties of shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes): a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 134, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.03.007

Bachmanov, A. A., Bosak, N. P., Glendinning, J. I., Inoue, M., Li, X., Manita, S., et al. (2016). Genetics of amino acid taste and appetite. Adv. Nutr. 7, 806S–822S. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011270

Bing, S.-J., Chen, X.-S., Zhong, X., Li, Y.-Q., Sun, G.-J., Wang, C.-Y., et al. (2024). Structural, functional and antioxidant properties of Lentinus edodes protein hydrolysates prepared by five enzymes. Food Chem. 437:137805. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137805

Bolesławska, I., Górna, I., Sobota, M., Bolesławska-Król, N., Przysławski, J., and Szymański, M. (2024). Wild mushrooms as a source of bioactive compounds and their antioxidant properties—preliminary studies. Food Secur. 13:2612. doi: 10.3390/foods13162612

Cai, T., Hai, N., Guo, P., Feng, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., et al. (2024). Characteristics of umami taste of soy sauce using electronic tongue, amino acid analyzer, and MALDI−TOF MS. Food Secur. 13:2242. doi: 10.3390/foods13142242

Chen, C., Chen, G., Wang, S., Pei, F., Hu, Q., and Zhao, L. (2017). Speciation changes of three toxic elements in Lentinus edodes after drying and soaking. J. Food Process. Preserv. 41:e12772. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12772

Chen, Z., Fang, X., Wu, W., Chen, H., Han, Y., Yang, H., et al. (2021). Effects of fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum GDM1.191 on the umami compounds in shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes). Food Chem. 364:130398. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130398

Chen, W., Li, X., Zhao, Y., Chen, S., Yao, H., Wang, H., et al. (2022). Effects of short-term low salinity stress on non-volatile flavor substances of muscle and hepatopancreas in Portunus trituberculatus. J. Food Compos. Anal. 109:104520. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104520

Cui, L., Liu, Y., Liu, M., Ren, M., Ahmed, A. F., and Kang, W. (2022). Identification of phytochemicals from Lentinus edodes and Auricularia auricula with UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS. J. Future Foods 2, 253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jfutfo.2022.06.006

Datta, S., Annapure, U. S., and Timson, D. J. (2017). Different specificities of two aldehyde dehydrogenases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. Biosci. Rep. 37:BSR20160529. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160529

Du, X., Jing, H., Wang, L., Huang, X., Wang, X., and Wang, H. (2022). Characterization of structure, physicochemical properties, and hypoglycemic activity of goat milk whey protein hydrolysate processed with different proteases. LWT 159:113257. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113257

Esfandi, R., Willmore, W. G., and Tsopmo, A. (2024). Structural characterization of peroxyl radical oxidative products of antioxidant peptides from hydrolyzed proteins. Heliyon 10:e30588. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30588

Fang, X., Chen, Z., Wu, W., Chen, H., Nie, S., and Gao, H. (2022). Effects of different protease treatment on protein degradation and flavor components of Lentinus edodes. eFood 3:e41. doi: 10.1002/efd2.41

Gao, J., Fang, D., Muinde Kimatu, B., Chen, X., Wu, X., Du, J., et al. (2021). Analysis of umami taste substances of morel mushroom (Morchella sextelata) hydrolysates derived from different enzymatic systems. Food Chem. 362:130192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130192

Gao, H., Wang, W., Xu, D., Wang, P., Zhao, Y., Mazza, G., et al. (2021). Taste-active indicators and their correlation with antioxidant ability during the Monascus rice vinegar solid-state fermentation process. J. Food Compos. Anal. 104:104133. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104133

Gao, P.-P., Zhang, M.-M., Wu, F., Ma, R., Zhang, F., Liu, H.-Q., et al. (2024). Impact of Stropharia rugosoannulata extract on Lactobacillus reuteri HBM11-69 growth, metabolism and mechanisms. LWT 201:116175. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116175

Goldberg, S. (2021). Mechanical/physical methods of cell disruption and tissue homogenization Methods Mol. Biol., 424: 563–585. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1186-9_36

Gopal, J., Sivanesan, I., Muthu, M., and Oh, J.-W. (2022). Scrutinizing the nutritional aspects of Asian mushrooms, its commercialization and scope for value-added products. Nutrients 14:3700. doi: 10.3390/nu14183700

Huang, Q., Qian, X., Jiang, T., and Zheng, X. (2019). Effect of chitosan and guar gum based composite edible coating on quality of mushroom (Lentinus edodes) during postharvest storage. Sci. Hortic. 253, 382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2019.04.062

Hwang, I.-S., Chon, S.-Y., Bang, W.-S., and Kim, M. K. (2021). Influence of roasting temperatures on the antioxidant properties, β-glucan content, and volatile flavor profiles of shiitake mushroom. Food Secur. 10:54. doi: 10.3390/foods10010054

Ismail-Fitry, M. R., and Ang, S.-S. (2019). Production of different mushroom protein hydrolysates as potential Flavourings in chicken soup using stem bromelain hydrolysis. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 57, 472–480. doi: 10.17113/ftb.57.04.19.6294

Karami, Z., Peighambardoust, S. H., Hesari, J., Akbari-Adergani, B., and Andreu, D. (2019). Antioxidant, anticancer and ACE-inhibitory activities of bioactive peptides from wheat germ protein hydrolysates. Food Biosci. 32:100450. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2019.100450

Kowalska, S., Szłyk, E., and Jastrzębska, A. (2022). Simple extraction procedure for free amino acids determination in selected gluten-free flour samples. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 248, 507–517. doi: 10.1007/s00217-021-03896-7

Krishnarjuna, B., and Ramamoorthy, A. (2022). Detergent-free isolation of membrane proteins and strategies to study them in a near-native membrane environment. Biomol. Ther. 12:1076. doi: 10.3390/biom12081076

Li, Y., Ishikawa, Y., Satake, T., Kitazawa, H., Qiu, X., and Rungchang, S. (2014). Effect of active modified atmosphere packaging with different initial gas compositions on nutritional compounds of shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 92, 107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.12.017

Li, K., Qiao, K., Xiong, J., Guo, H., and Zhang, Y. (2023). Nutritional values and bio-functional properties of fungal proteins: applications in foods as a sustainable source. Food Secur. 12:4388. doi: 10.3390/foods12244388

Liu, T.-T., Xia, N., Wang, Q.-Z., and Chen, D.-W. (2019). Identification of the non-volatile taste-active components in crab sauce. Food Secur. 8:324. doi: 10.3390/foods8080324

Luan, C., Zhang, M., Devahastin, S., and Liu, Y. (2021). Effect of two-step fermentation with lactic acid bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on key chemical properties, molecular structure and flavor characteristics of horseradish sauce. LWT 147:111637. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111637

Mann, G., Mora, S., Madu, G., and Adegoke, O. A. J. (2021). Branched-chain amino acids: catabolism in skeletal muscle and implications for muscle and whole-body metabolism. Front. Physiol. 12:702826. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.702826

Matthews, D. E. (2020). Review of lysine metabolism with a focus on humans. J. Nutr. 150, 2548S–2555S. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa224

Morales, D., Rutckeviski, R., Villalva, M., Abreu, H., Soler-Rivas, C., Santoyo, S., et al. (2020). Isolation and comparison of α- and β-D-glucans from shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) with different biological activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 229:115521. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115521

Petrescu, D. C., Vermeir, I., and Petrescu-Mag, R. M. (2019). Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: a cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:169. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010169

Poojary, M. M., Orlien, V., Passamonti, P., and Olsen, K. (2017). Enzyme-assisted extraction enhancing the umami taste amino acids recovery from several cultivated mushrooms. Food Chem. 234, 236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.157

Prandi, B., Cigognini, I. M., Faccini, A., Zurlini, C., Rodriguez, O., and Tedeschi, T. (2023). Comparative study of different protein extraction technologies applied on mushrooms by-products. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 1570–1581. doi: 10.1007/s11947-023-03015-2

Ramos, M., Burgos, N., Barnard, A., Evans, G., Preece, J., Graz, M., et al. (2019). Agaricus bisporus and its by-products as a source of valuable extracts and bioactive compounds. Food Chem. 292, 176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.04.035

Reis, F. S., Martins, A., Vasconcelos, M. H., Morales, P., and Ferreira, I. C. F. R. (2017). Functional foods based on extracts or compounds derived from mushrooms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 66, 48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.05.010

Sheng, K., Wang, C., Chen, B., Kang, M., Wang, M., Liu, K., et al. (2021). Recent advances in polysaccharides from Lentinus edodes (Berk.): isolation, structures and bioactivities. Food Chem. 358:129883. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129883

Song, F., Lin, Y., Xie, L., Chen, L., Jiang, H., Wu, C., et al. (2024). Nutritional value evaluation of wild edible mushroom (Helvella leucopus) from western China. Int. Food Res. J. 31, 503–513. doi: 10.47836/ifrj.31.2.21

Wang, H. J., An, D. S., Rhim, J.-W., and Lee, D. S. (2017). Shiitake mushroom packages tuned in active CO2 and moisture absorption requirements. Food Packag. Shelf Life 11, 10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2016.11.002

Wang, B., Shi, Y., Lu, H., and Chen, Q. (2023). A critical review of fungal proteins: emerging preparation technology, active efficacy and food application. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 141:104178. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.104178

Wen, C., Zhang, J., Zhang, H., Duan, Y., and Ma, H. (2020). Plant protein-derived antioxidant peptides: isolation, identification, mechanism of action and application in food systems: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 105, 308–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.019

Xie, Y., Guo, C., Devahastin, S., Jiang, L., Du, M., and Yi, J. (2024). Non-destructive determination of volatile compounds and prediction of amino acid nitrogen during sufu fermentation via electronic nose in combination with machine learning approaches. LWT 207:116648. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116648

Xu, J., Shen, R., Jiao, Z., Chen, W., Peng, D., Wang, L., et al. (2022). Current advancements in antitumor properties and mechanisms of medicinal components in edible mushrooms. Nutrients 14:2622. doi: 10.3390/nu14132622

Xu, X., Yu, C., Liu, Z., Cui, X., Guo, X., and Wang, H. (2024). Chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes). J. Fungi 10:552. doi: 10.3390/jof10080552

Yang, F., Fu, A., Meng, H., Liu, Y., and Bi, S. (2024). Non-volatile taste active compounds and umami evaluation of Agrocybe aegerita hydrolysates derived using different enzymes. Food Biosci. 58:103772. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.103772

Yang, J., Zhu, B., Dou, J., Ning, Y., Wang, H., Huang, Y., et al. (2023). pH and ultrasound driven structure-function relationships of soy protein hydrolysate. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 85:103324. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103324

Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, X., Wang, W., Wang, J., Li, X., et al. (2023). Preparation and identification of peptides with a-glucosidase inhibitory activity from shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) protein. Food Secur. 12:2534. doi: 10.3390/foods12132534

Zhang, L., Zhang, M., Adhikari, B., and Zhang, L. (2023). Salt reducing and saltiness perception enhancing strategy for shiitake (Lentinus edodes) bud using novel combined treatment of yeast extract and radio frequency. Food Chem. 402:134149. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134149

Zhou, S., Xiao, Z., Sun, J., Li, L., Wei, Y., Yang, M., et al. (2024). Low-molecular-weight peptides prepared from Hypsizygus marmoreus exhibit strong antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Molecules 29:3393. doi: 10.3390/molecules29143393

Keywords: mushroom protein, amino acid evaluation, response surface, protease hydrolysis, flavor, TAV value

Citation: Zheng B, Wu X, Qiao T, Ding Q and Wang H (2025) Response surface methodology optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis of Lentinus edodes and analysis of product ingredients functions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1617816. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1617816

Edited by:

Reza Rastmanesh, American Physical Society, United StatesReviewed by:

Seydi Yıkmış, Namik Kemal University, TürkiyeAndrew Setiawan Rusdianto, University of Jember, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Zheng, Wu, Qiao, Ding and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Honglei Wang, d2FuZ2hvbmdsZWlAY2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Bowei Zheng

Bowei Zheng Xiaoqi Wu

Xiaoqi Wu Tonglei Qiao

Tonglei Qiao Qiang Ding

Qiang Ding Honglei Wang

Honglei Wang