- Department of Agricultural Education and Communication, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

Introduction: This study explores the leadership roles and knowledge transfer strategies of female health and nutrition field technicians in Guatemala’s Western Highlands, a region marked by high rates of poverty and chronic malnutrition. Grounded in transformational leadership theory, the study investigates how these women act as agents of change in rural extension services and aims to understand their leadership styles, motivations, and the impact of their personal experiences on their work. Female technicians were selected due to their unique position at the intersection of technical expertise and community engagement, particularly in female-led households where gender-sensitive approaches are critical.

Methods: A qualitative instrumental case study design was employed for this research, utilizing semi-structured interviews, role-playing, participant observation, and visual methods. Data were collected in the Los Cuchumatanes region of Guatemala from 12 female health and nutrition extension workers, purposefully selected based on their experience and roles within rural communities. A constructivist paradigm guided the interpretation of the participants’ motivations, leadership, and experiences. Data analysis followed a systematic qualitative approach, including open and pattern coding.

Results: Extension workers identified three key leadership approaches: Transformational Growth, Servant Leadership, and Relationship-Oriented. Technicians also highlighted their roles as change agents and mentors, facilitating behavior change and offering indirect support in underserved areas. Effective knowledge transfer methods included home visits, experiential learning, visual aids, and community involvement. Extension workers expressed cautious optimism for the future, emphasizing the need for continued development, professional recognition, and inclusion.

Discussion: This study underscores the importance of values-based leadership, gender-sensitive approaches, and participatory methods in promoting sustainable community development and enhancing the impact of extension services. It also highlights the emotional labor and resilience of female technicians, whose leadership is grounded in lived experience and relational engagement.

1 Introduction

With its social, economic, and ecological diversity, Latin America presents both an opportunity and a challenge for effectively implementing extension services (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017a; Rivera and Alex, 2008). Across the region, extension programs have evolved from top-down, technology-transfer models to more community-based approaches emphasizing capacity building, empowerment, and inclusivity (Landini and Brites, 2018; Rivera and Alex, 2008). Leadership within this evolving model is not solely a matter of managerial or technical competency; it involves building trust, navigating cultural nuances, and motivating behavior change in a context of limited resources and often fragmented institutional support (Anderson and Feder, 2007; GLOBE, 2020; Krys et al., 2022; Landini, 2016). Motivations of extension personnel—why they choose this work, how they persist in the face of challenges, and what aspirations drive their engagement—are increasingly viewed as central to the sustainability and effectiveness of development interventions (Luque Zúñiga et al., 2021; Mosso et al., 2022).

Among the many actors within Latin American extension systems, female field technicians represent a critical yet under-researched group (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1997, 2017b; International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2020). Operating at the intersection of technical expertise and grassroots engagement, these women often act as intermediaries between state agencies, NGOs, and the rural communities they serve (Acosta, 2024; Huairou Commission, 2020; Weidemann, 2021). Their roles are multifaceted: they must implement technical projects, foster community participation, manage conflict, and deliver health and nutrition education that resonates across varied sociocultural contexts (Gibbons et al., 2022; International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2020). Their contributions extend beyond professional boundaries, frequently involving emotional labor, role modeling, and advocacy (Lopez-Escober et al., 2024). Despite systemic gender biases and institutional limitations, female field technicians have demonstrated resilience, innovation, and leadership, particularly in rural regions with entrenched poverty and malnutrition (Howland et al., 2021; Lamiño Jaramillo et al., 2022).

Extension services have followed broader Latin American trends in Guatemala, transitioning from centralized, state-controlled models to more decentralized and participatory structures (Landini and Vargas, 2020; Lamiño Jaramillo et al., 2022). The country’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food implements rural extension services emphasizing food security, family farming, and sustainable agricultural practices (Gibbons and Luna, 2015; López-Ridaura et al., 2019). However, as in many other countries in the region, implementation is uneven, and the effectiveness of programs is heavily dependent on local agents’ capacities and commitment (Gibbons et al., 2022; Peterman et al., 2014). Female technicians are often on the front lines of these programs, particularly in regions like the Western Highlands, where rural development work’s logistical and social complexity is amplified by the area’s distinct geography and demographics (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022; González-Esquivel et al., 2020).

The Western Highlands of Guatemala, composed of departments such as Quiché, Huehuetenango, Totonicapán, and San Marcos, is marked by mountainous terrain, significant Indigenous populations, and persistent poverty (González-Esquivel et al., 2020; López-Ridaura et al., 2019). These conditions pose serious challenges for extension efforts (Landini and Vargas, 2018; Weidemann, 2021). Transportation and communication barriers hinder access to remote villages, while language differences and culturally specific practices require nuanced, adaptive communication strategies (González-Esquivel et al., 2020). Moreover, the region faces some of the highest rates of chronic malnutrition in Latin America, affecting nearly half of all children under five (Landini and Vargas, 2018; Lopez-Escober et al., 2024). This health crisis underscores the need for well-coordinated, culturally competent extension programs integrating agriculture with nutrition education and health promotion (Acosta, 2024; Lopez-Escober et al., 2024).

In such a context, the role of female field technicians is particularly noteworthy. They are often better positioned to work with women in rural households, the primary caregivers and key decision-makers in food preparation and child nutrition (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1997; Huairou Commission, 2020). However, they also face added challenges as women working in male-dominated professional spaces (Lopez-Escober et al., 2024). Navigating these dynamics requires technical knowledge, emotional intelligence, cultural competency, and personal conviction (Lamiño Jaramillo et al., 2022). Research has shown that these technicians frequently draw motivation from their life experiences, including histories of poverty, discrimination, or health challenges, which inform their commitment to community well-being and social justice (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2020; Mosso et al., 2022).

Understanding what motivates these technicians, their leadership styles, and their aspirations for themselves and their communities is crucial for improving extension programming (Landini and Vargas, 2020). Leadership in this context is not defined solely by formal titles or positions of authority but by influence, credibility, and the ability to inspire action (GLOBE, 2020; Krys et al., 2022). Female field technicians often lead by example, embodying the behavioral changes they seek to promote, such as adopting home gardens, improving food hygiene, or advocating for child nutrition (Inter-American Development Bank [IDB], 2016; International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2020). Their leadership is thus grounded in empathy and lived experience, making them uniquely effective at catalyzing change within their communities (Gibbons et al., 2022; Lopez-Escober et al., 2024).

Despite their critical role, female technicians often remain undervalued within institutional frameworks (Acosta, 2024; Lopez-Escober et al., 2024). They may face limited opportunities for promotion, insufficient training resources, or gender-based discrimination within bureaucratic hierarchies (Lopez-Escober et al., 2024). These constraints affect their well-being and limit the potential impact of extension services (Gibbons and Luna, 2015). Therefore, investing in these professionals’ leadership development and well-being is not just a matter of equity but a strategic imperative for effective rural development. Therefore, this study examines the lived experiences of female field technicians working in nutrition and health extension services in Guatemala’s Western Highlands. It seeks to contribute to a broader understanding of how localized leadership and personal motivation intersect to drive systemic change in rural health and nutrition outcomes. To accomplish this goal, four research questions were examined: (1) How do extension workers describe their leadership? (2) What are extension workers’ roles in the communities? (3) What are the most effective ways to transfer knowledge to producers? (4) What is the expected future of agricultural extension in Guatemala?

1.1 Theoretical framework

This research is framed based on the transformational leadership theory, which is characterized by leaders inspiring followers to accomplish goals, promoting changes and transformation, and assessing follower motivations and the satisfaction of their needs (Bennis and Nanus, 2007; Kouzes and Posner, 2017; Northouse, 2019). This theory involves emotions, values, ethics, standards, and long-term goals in leadership scenarios (Northouse, 2019).

Transformational leadership plays a crucial role by aligning the goals of individual employees with those of the organization, emphasizing long-term success, and building trust and commitment (Burns, 1978; Diaz et al., 2024). According to Bass (1985), transformational leaders motivate followers to exceed their self-interests for the organization’s good, fostering an environment of innovation and change (Bass, 1985; Bass and Riggio, 2006). Bass (1985) expanded on Burns’s work and formalized the transformational leadership model with four key components: (1) Idealized Influence, (2) Inspirational Motivation, (3) Intellectual Stimulation, and (4) Individualized Consideration.

1. Idealized influence involves leaders serving as role models who are respected and admired by their followers; these leaders possess a clear vision and sense of purpose and are willing to take risks (Bass and Riggio, 2006; Stewart, 2006). For this research, female extension workers are often viewed as role models within rural communities, gaining trust and admiration through sustained presence, cultural sensitivity, and a strong commitment to well-being. For instance, participants who had multiple years working with the communities demonstrated a clear vision for improving nutrition and health and earned respect by leading by example.

2. Inspirational motivation occurs when leaders inspire and motivate others, generating enthusiasm and challenging them to achieve more; they communicate expectations clearly and show a strong commitment to goals and a shared vision (Bass and Riggio, 2006; Stewart, 2006). For this research, many extension workers described their work as driven by a collective vision, encouraging women and families to adopt healthier behaviors despite systemic barriers. Through community meetings, role-playing, and storytelling, these leaders communicate expectations clearly and inspire others to believe that change is possible.

3. Intellectual stimulation is when leaders encourage new ideas and innovative approaches, fostering creativity in others while avoiding public criticism or correction; this creates a supportive environment for growth and development (Bass and Riggio, 2006; Stewart, 2006). Participants employed creative and participatory strategies, such as cooking demonstrations and visual materials, to introduce new ideas without dismissing traditional practices. Their approach to integrating Indigenous knowledge with modern nutrition concepts exemplifies how transformational leaders foster innovation without alienation.

4. Individualized consideration involves leaders focusing on the unique needs and development potential of everyone; they create a supportive climate where individual differences are respected, encourage interactions with followers, and remain attentive to their concerns (Bass and Riggio, 2006; Stewart, 2006). The female extension agents’ one-on-one relationships with community members, particularly women, illustrate individualized consideration. They tailor interventions to household needs, listen attentively to personal concerns (e.g., child malnutrition, family dynamics), and respect each family’s pace of adoption.

Caldwell et al. (2012) state that transformational leadership aims to align the goals of individuals with those of the organization in which they work. This approach emphasizes creating long-term value and fostering high commitment and trust levels. Its ethical foundation lies in dedication to the well-being of the organization, its employees, and society (Caldwell et al., 2012; Diaz et al., 2024). Additionally, transformational leadership has been shown to enhance organizational effectiveness by promoting a culture of continuous improvement and ethical behavior (Avolio and Yammarino, 2013; Wang et al., 2011).

Furthermore, Odumeru and Ogbonna (2013) provide evidence that transformational leadership significantly augments transactional leadership, resulting in higher levels of individual, group, and organizational performance (Odumeru and Ogbonna, 2013). Extension workers often describe their leadership as collaborative and community-focused, emphasizing the importance of building trust and fostering relationships within the community to disseminate knowledge and practice effectively (Paxson et al., 1993).

Although the study was initially grounded in transformational leadership theory, additional leadership styles, such as servant leadership and relationship-oriented leadership, emerged inductively during data analysis. These frameworks were not part of the original analytical lens but were incorporated into thematic interpretation to more accurately reflect participants’ lived experiences and relational practices. The inclusion of these frameworks enriches the analysis by capturing the service-driven, trust-based, and collaborative dimensions of leadership that are especially relevant in rural, gender-sensitive extension contexts. Rather than conflicting with the original theoretical lens, these emergent styles complement transformational leadership by illustrating how change agency is enacted through relational, ethical, and inclusive practices.

2 Methodology

This study is part of a broader research initiative focused on Guatemalan female extension agents. While it draws from the same participant group as a previously published manuscript (Ceme et al., 2025), it constitutes a distinct and independent investigation. The two studies differ in their research questions, data collection instruments, and analytical frameworks. The earlier manuscript conducted a SWOT analysis of female extension agents, whereas the present study explores their leadership styles and roles. No data, quotations, or findings were reused, ensuring that each manuscript reflects a separate and original line of inquiry.

To accomplish the study’s purpose, we used an instrumental case study design (Stake, 1995). We bounded the case by place, i.e., Western Highlands of Guatemala, and participants’ occupation, i.e., health and nutrition female extension workers. Moreover, a constructivist paradigm guided the interpretation of the perspectives of the female extension agents’ motivations, roles, and leadership (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

2.1 Study area

This study was conducted in Los Cuchumatanes, a mountainous region in the Western Highlands of Guatemala that spans the departments of Huehuetenango and Quiché. Rising to over 3,800 meters above sea level, it is the highest non-volcanic mountain range in Central America (Stadel, 2008). The area is home to a diverse population of Indigenous communities, including the Q’anjob’al, Mam, Chuj, and Ixil peoples, many of whom reside in rural, hard-to-reach communities characterized by limited infrastructure and access to essential services (Lovell, 2005).

The region’s geographic isolation and rugged terrain have contributed to its cultural resilience and posed challenges for development initiatives, particularly in health, nutrition, and education (Grandia, 2012). Many communities rely on subsistence agriculture, and high rates of poverty and chronic malnutrition persist, particularly among women and children (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017b).

This study employed a qualitative design because the purpose was to understand the lived experiences, perspectives, and leadership practices of Guatemalan female extension agents within their cultural and occupational contexts. Leadership, particularly in intercultural and rural development settings, is socially constructed and cannot be fully captured through quantitative surveys alone (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Stake, 1995). Extension agents, especially women, play a pivotal role in supporting rural livelihoods, improving nutrition, and promoting culturally sensitive health practices in the region. This context made Los Cuchumatanes a fitting location for exploring the experiences of female extension workers engaged in health and nutrition outreach in rural Indigenous communities. Figure 1 shows the Map of Guatemala, pointing to the “Los Cuchumatanes” area of study.

2.2 Participant recruitment and selection

Before reaching out to organizations and participants, the University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study under IRB number 2022–773. This research was classified as exempt because informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews. Participants faced no risks, and their confidentiality was guaranteed.

Recruitment began with a capacity-building workshop on gender in rural extension, facilitated by the principal researcher [PL] and attended by 25 female field technicians. The workshop served a dual purpose: (1) to strengthen participants’ skills in recognizing and addressing gendered challenges in agricultural and health extension, and (2) to provide a preliminary opportunity for participants to reflect on their professional roles. While the workshop had educational objectives, it also functioned as a formative stage in the research, helping identify participants willing and suitable to take part in subsequent data collection.

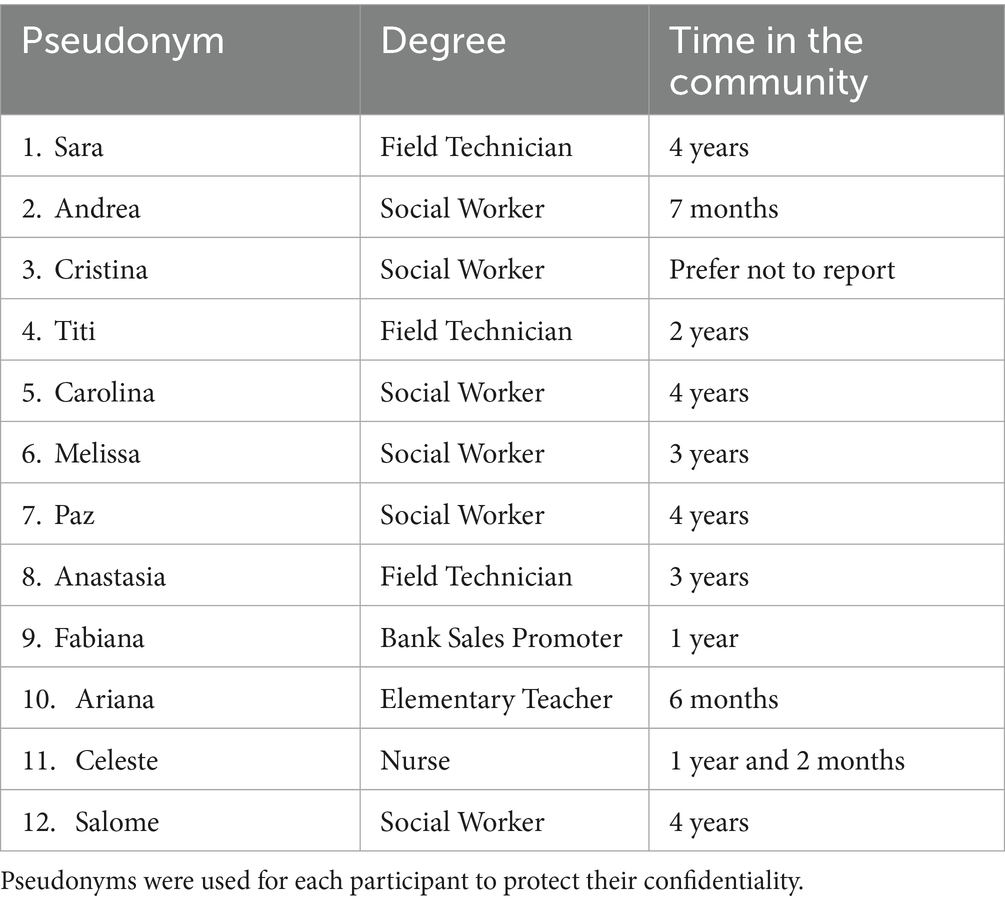

From the 25 workshop participants, 12 were purposefully invited to participate in this research based on the following criteria: (1) have at least 6 months of experience working with women in the western highlands of Guatemala, (2) be over 18 years old, and (3) reside in a rural community. Pseudonyms were used to protect their identities. Table 1 presents the demographic information of the participants.

2.3 Data collection

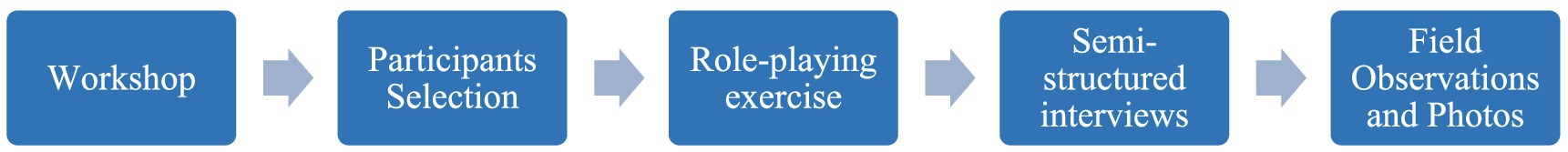

Data collection unfolded in several stages over a four-week immersion and included several sources, including semi-structured interviews, research memos, role-playing, photos, and participatory and non-participatory observations. Figure 2 represents the timeline of activities.

2.3.1 Role-playing

Before the interviews, the principal investigator [PL] led the women in a group activity about what it means to work in extension. PL presented a series of questions related to first contact with the group they served, how to address their job challenges, gender opportunities, and youth opportunities. PL then asked the women to sit together to discuss the findings, ensuring a more complete understanding of their responses. The role-playing was implemented before the participants’ interviews and the document analysis. PL requested to record the videos, and they verbally accepted. This video helped participants articulate their extension experiences in a reflective, low-stakes setting, and it provided PL with contextual knowledge to better frame interview questions and prepare for the subsequent immersion.

2.3.2 Semi-structured interviews

The interviews were conducted using remote systems, Zoom, and WhatsApp video, depending on the participants’ preferences (Archibald et al., 2019). The first data source was semi-structured interviews, which allowed us to follow a specific line of questioning but left space to inquire about the participants’ opinions regarding topics that may arise during the interview (Aurini et al., 2021). Although research questions guided the interviews, they permitted flexibility for new ideas and themes to arise, with additional questions being integrated based on the context of each interview (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed using Sonix®.

We also employed memoing after each interview and during essential moments (Saldana, 2016). Memoing was used to preserve important information that could not be recorded. This method includes writing down personal comments, feelings, and reflections on the interview. This process enhances the transparency of the researcher’s bias through reflexivity (Bingham, 2023). The information from the memo and interviews was matched with the other data collected by the researchers to triangulate the information.

2.3.3 Participant and non-participant observations

Given the emphasis of qualitative research on understanding participants within their natural contexts, observation served as a valuable method for collecting contextual and behavioral data throughout this study (Schensul et al., 1999; Spradley, 2016). Two complementary approaches were employed: participant observation and non-participant observation. Participant observation allowed PL to engage directly in community meetings designed to discuss and co-create potential local projects. This immersive involvement enabled a deeper understanding of participants’ worldviews, leadership dynamics, and communicative practices (Aurini et al., 2021; Spradley, 2016). In contrast, non-participant observation was used during formal training sessions, where PL observed interactions from an external standpoint without direct involvement, maintaining an objective stance while documenting behaviors, responses, and participation patterns (Laurier, 2010).

Throughout all observation activities, PL maintained detailed field notes and focused on listening attentively to verbal and non-verbal cues relevant to leadership expression, motivation, and knowledge transfer practices. Prior to conducting observations, all participants were informed about the purpose and scope of the research and given the opportunity to ask questions, thereby ensuring ethical transparency and voluntary engagement (Laurier, 2010). These observational insights supported the interviews, offering a multidimensional understanding of the extension workers’ roles and experiences within their communities.

2.3.4 Photos

Photography was used as a complementary method to gain insight into the daily job of participants. The photographs enhanced the data collected from interviews and observations, adding a visual element to the research (Pain, 2012). To protect the confidentiality of participants, PL obtained verbal consent for the use of photographs and assured participants that their faces would be blurred if the photos were published. The visual data enriched the analysis and deepened the understanding of the participants’ everyday experiences (Balmer et al., 2015; Barbour, 2008).

2.4 Data analysis

Data collection continued until data saturation, when additional data would no longer contribute significant new insights (Saunders et al., 2018). The steps in the qualitative analysis process included: (1) conducting a preliminary exploration of the data by reviewing transcripts and writing memos; (2) coding the data by segmenting and labeling the text; (3) validating the coding through an inter-coder agreement check; (4) using the codes to create themes by clustering similar codes together; and (5) connecting and interrelating the themes (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

Each interview was reviewed to guarantee accurate transcription, preserving colloquial expressions. According to Morse and Richards (2002), the objective of coding is to let the researcher focus and simplify the interpretation of the data. After transcribing the interviews, researchers analyzed the data with a constant comparative method. This involved continuously comparing the new data with previously analyzed data to refine and expand the emerging categories and themes (Creswell and Creswell, 2018).

The first series of coding that we implemented was initial open coding. According to Saldana (2016), this coding is helpful for case studies because it lends itself easily to analyzing and redirecting the focus of the data analysis. The coding objective was to take the data apart, reconfigure it through identification, and establish the data in categories of each phenomenon that appeared, generating categories, subcategories, and dimensions (Saldana, 2016).

After the first coding cycle, Pattern Coding was used as explanatory coding that pulls together the raw material into a more meaningful unit of analysis. This data analysis methodology helped us connect topics, concepts, and themes that emerged from the data, provided order, and made the data more manageable (Morse and Richards, 2002). We then grouped the codes into major themes to better understand the phenomenon (Saldana, 2016).

For both coding cycles, the three researchers involved in this research independently analyzed the transcripts, compared interpretations, and resolved discrepancies through discussion. A shared codebook was used to document decisions and ensure consistency.

2.5 Trustworthiness

In a qualitative study, credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability are the primary elements of research rigor (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Credibility is considered the researcher’s responsibility to accurately represent established information from the research (Ary et al., 2010), and it can be achieved through methods such as using detailed descriptions and triangulating the data. Researchers utilized various data sources for this research, including semi-structured interviews, research memos, role-playing videos, photos, participatory and non-participatory observations, and document analysis. To increase transparency and minimize bias, researchers documented inquiries, comments, personal feelings, and reflections from the interviews (Bingham, 2023; Saldana, 2016).

There are various methods to ensure transferability (Creswell and Creswell, 2018), including providing a comprehensive explanation and utilizing sampling techniques that focus on a particular group, thus illustrating how the study could be relevant in other scenarios or with different populations. Researchers utilized purposive sampling to choose participants based on specific characteristics (Palinkas et al., 2015). One way to ensure dependability is by documenting the interview process and providing a detailed account of the research methodology. This study recorded the data collection in a dataset containing interview transcripts, reflexive memos, and official documents. Furthermore, an intercoder agreement was considered to ensure coding consistency and comparison (Hanson et al., 2019).

Confirmability can be achieved through research reflexivity (Korstjens and Moser, 2018). This research happened when the researcher disclosed their background to reduce bias (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Additionally, researchers carefully examined and coded the interview transcripts three times, reflecting on the biases and assumptions that might be evident during the data analysis.

2.6 Researcher as an instrument

Despite employing various methods to minimize bias, it is important to acknowledge that researcher bias can never be fully eliminated from the qualitative research process (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). In the interest of transparency, the following statements provide context regarding potential sources of bias in this study.

As noted by Ary et al. (2010), the researcher is the primary instrument for data collection in qualitative research. In this study, the investigators brought significant experience working in rural communities across Latin America (Lamiño Jaramillo et al., 2021; Lamino Jaramillo and Boren-Alpízar, 2023). The lead investigator spent one month embedded with extension agents, gaining firsthand insight into the challenges and constraints female extension agents face. The second and third investigators have served as extension agents in Latin America, which has deepened their understanding of rural realities and the specific barriers women encounter.

As researchers focused on rural education, we recognize the vital contributions of female extension agents and acknowledge that national stereotypes surrounding their roles remain largely unchallenged. Considering these contextual factors, it is essential to affirm the importance of female extension agents, examine their roles and the implementation of their work, and explore pathways to enhance the involvement and empowerment of rural women.

3 Results

3.1 Research question 1: How do extension workers describe their leadership?

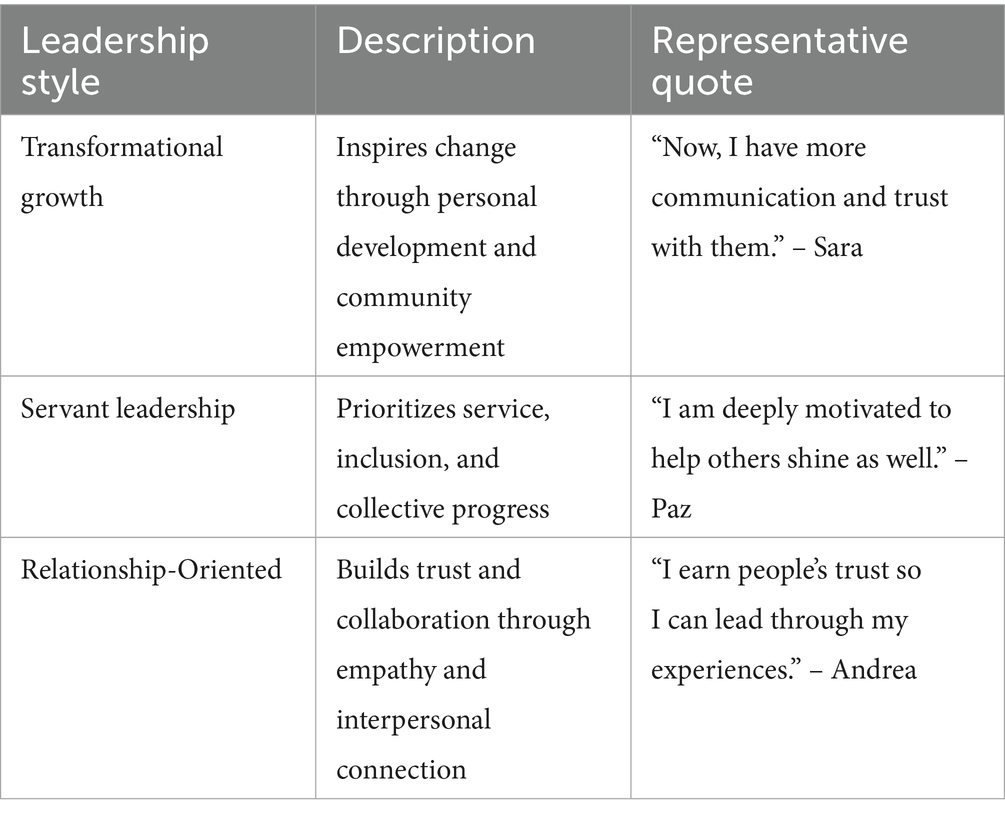

Participants were asked to describe their preferred leadership approach in response to the first research question. We analyzed their responses and linked them to established leadership styles. As a result, the data revealed three main leadership approaches: Transformational Growth, Servant Leadership, and Relationship-Oriented. A description of the three emergent leadership styles, with supportive evidence, is provided in Table 2.

3.1.1 Practicing transformational leadership

For this first theme, we analyzed the leadership development process among the extension agents to see how they transform across adversities. Participants described leadership practices that align with transformational leadership, particularly how they inspire, motivate, and engage community members (Diaz et al., 2024). Rather than exercising authority from a distance, these extension workers emphasized trust-building, adaptability, and collaborative goal-setting as strategies for fostering meaningful change. Their leadership approach focused not only on their growth but also on catalyzing the growth and empowerment of others.

Sara shared how her evolving approach to communication helped her better engage with families in the community:

“Maybe before, I was not very organized, right? It is like working with families. Now I am more organized, planning my activities better to do things well. There is also more constant communication with the families. Maybe I did not communicate as much before, but now there is more communication and trust with them.”

Rather than imposing solutions, participants described how they learned to co-create strategies with community members. Celeste, for example, reflected on how improved relationships and better coordination enhanced her leadership impact:

“Maybe I have changed a little. I used to be more closed off, and maybe I lacked confidence or was shy. But now, I have learned to handle myself better. Since I have been here for over a year, I have a better relationship and more contact with my coworkers. Coordination has also improved a lot.”

Others described how personal growth, particularly in communication and confidence, translated into a more active and motivating leadership style. Salome noted how her ability to speak up and encourage others grew over time:

“Yes, my communication has improved. Before, I was afraid and did not trust my abilities. However, I have realized I am very good at talking to people. Now, when I say to someone, ‘Look, do this, it is going to work, do not be afraid,’ they respond well. That has given me confidence in myself. But now, if accepted, great, and if not, at least I shared it. That has helped me build more confidence and improve.”

Ariana added that leadership in extension work often requires emotional intelligence and the ability to adjust to everyone’s personality, key features of transformational leadership:

“Before, I was very shy. I barely spoke [...] I thought I had a problem, especially when talking to people. However, you learn to understand people over time, whether they are short-tempered or easygoing. It is not personal. I was afraid. However, I have learned that you must adjust based on each person’s temperament.”

Salome offered a vivid and personal reflection on how emotional intelligence and openness help build trust. Her strategy involves showing vulnerability, reciprocity, and appreciation for local wisdom. This approach, she explained, helps break down barriers and fosters mutual learning:

"I used to be a Coca-Cola saleswoman. My boss told me, ‘Win people’s hearts and they will take you places you never imagined.’ So when I arrive, I open myself up first so that people can open the doors of their homes to me. I tell them: ‘This is my job, support me, and you will see that what comes into your home will be knowledge to improve your life.’ I first earned the trust of the head of the household, sometimes a man, but often a mother-in-law [...] I ask them about everything: the kids, the chickens, the dogs, and that helps build trust. Sometimes they offer me food or drinks, and even if it upsets my stomach, I accept everything. People notice the simplicity and listen. I have earned everyone’s heart, and I tell them that I also come to learn from them, because I often see better practices than the ones I am teaching. I tell them: ‘I am going to replicate this,’ and I even use them as examples."

These testimonies highlight how extension agents transformed themselves and used their growth to transform their communities by building trust, encouraging participation, and helping others believe in their capacity to change. This practice of shared transformation lies at the heart of transformational leadership.

3.1.2 Servant leadership

Servant leadership, first introduced by Greenleaf (1970), is a leadership approach that prioritizes the growth and well-being of individuals and communities over organizational success. This leadership style emphasizes empowerment, inclusivity, and collaboration (Liden et al., 2008). In this research, extension agents consistently demonstrated these principles, particularly in their commitment to serving others and ensuring that marginalized groups, such as female farmers, had access to resources and decision-making opportunities.

Paz expressed their motivation for leadership as an unwavering desire to uplift others: “I am deeply motivated to help others shine as well. I am not selfish with my thoughts or ideas; if I see an opportunity, I share it, and I want others also to achieve that sense of community.” This statement encapsulates the essence of servant leadership, where success is measured not by personal achievement but by the collective progress of the community.

Similarly, Anastasia described their leadership philosophy as deeply inclusive: “I see myself as having a leadership style where I am part of the team, I do not just tell others what to do. I believe in democratic leadership, if I am not mistaken, the kind of leadership where, if I say, ‘Okay, let us do this,’ I am included in that effort too. I am not just sending them off to do it; I accompany them through the process.” This approach reflects a servant style of leadership, where the leader actively engages in the process rather than simply delegating tasks.

Many extension agents, particularly those from Indigenous backgrounds, viewed their role as mentorship and empowerment. Celeste emphasized the importance of listening and fostering trust: “I believe I know how to listen and take others’ opinions into account, and I consider myself a good leader because I am not someone who imposes. I have gotten along well with my coworkers and the women, for example, when we work in groups. Thank God, I have had everyone’s understanding and support, and yes, I believe I have shown strong leadership.” This highlights a fundamental aspect of servant leadership, cultivating relationships based on respect, collaboration, and mutual understanding.

Another compelling example of servant leadership emerged in a story about a young woman who took initiative in solving a community-wide water issue. In describing this event, Salome observed how the young leader proposed multiple solutions: “I saw her demonstrating a great sense of leadership because she presented solutions: ‘Let us do this, and if it does not work, we will try something else.’ Everything was done by consensus.” This problem-solving approach, grounded in collective decision-making, reflects a key tenet of servant leadership, empowering others to take ownership of solutions rather than imposing decisions from the top down.

This leadership approach’s impact was evident in how extension agents celebrated the successes of those they worked with. Recognition events, such as awarding certificates for participation in nutrition and health programs, reinforced that leadership is not about personal accolades but empowering others to succeed.

3.1.3 Relationship-oriented

Relationship-oriented leadership emphasizes fostering interpersonal connections, building trust, and promoting collaboration within leadership roles. Leaders who adopt this approach prioritize the well-being and growth of their team members, creating a supportive environment that encourages engagement and development (Goleman et al., 2013; Yukl, 2012). This style is especially crucial in extension work, where cultivating trust and understanding between agents and farmers is key to the success of programs (Maulu et al., 2021).

Participants in this study underscored the importance of relationship-building with farmers, fellow extension agents, and other community members. Carolina shared a perspective that reflects a selfless and inclusive approach to leadership:

"My leadership? [..] I like people to participate, to ask me questions about certain things, and I like to guide when needed. [..] I try to support the women however I can. If I have a way to help them, I do, and I encourage them to move forward."

Her emphasis on guiding and supporting rather than directing highlights a leadership style grounded in encouragement, shared responsibility, and genuine care for others’ development, core elements of relationship-oriented leadership. Building trust and collaborative networks also emerged as foundational to effective leadership in extension settings. Fabiana described her efforts to engage both women and their husbands, acknowledging cultural dynamics that influence participation:

"I like to talk not only with the women who attend trainings, but also with their husbands. [..] Many still think, 'If he does not give me permission, I will not go.' So, we first reach out to the husbands and explain things so they feel comfortable. That is how we build bonds and show we care about our work and the well-being of those around us."

By recognizing these social norms and adjusting her approach, Fabiana fosters mutual respect and inclusivity, which are key tenets of relationship-oriented leadership. Andrea further illustrated how trust and shared experiences are central to her leadership identity: “I would describe my leadership as active and sociable. I earn people’s trust so I can lead through my experiences.” Her statement reinforces that relationship-oriented leadership is not just about charisma, but about being authentic, approachable, and willing to learn alongside others.

These reflections were echoed in field observations, where extension agents celebrated farmers’ successes through recognition events, such as awarding certificates for participation in nutrition and health programs. These moments of acknowledgment validated farmers’ efforts and strengthened the relational ties between agents and community members, further reinforcing trust and collaboration. Figure 3 shows two extension agents presenting a certificate of participation to a community member, symbolizing this shared success.

3.2 Research question 2: What are extension workers’ roles in the communities?

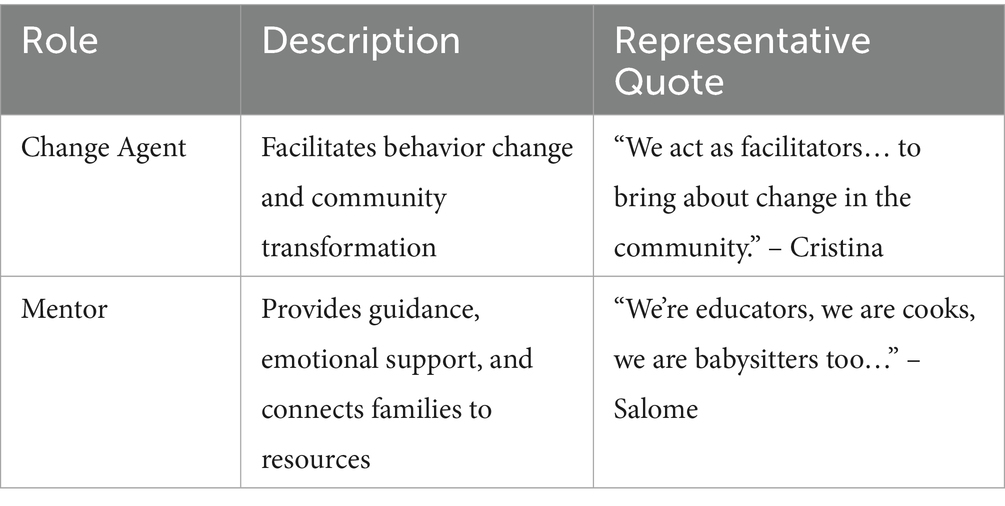

Female field technicians were interviewed about their roles in the community. They reported that they directly facilitate behavior change, which could take time to evaluate. They also expressed the indirect roles that they play in their communities. Due to a lack of other human services, they have had to take on additional roles, such as providing advice and recommendations. The data revealed two themes in response to the second research question: (1) Change agents and (2) Mentors. A description of the two main roles emergent from the data, with supportive evidence, is provided in Table 3.

3.2.1 Change agents

Change agents are pivotal in fostering development by introducing new practices, challenging misconceptions, and promoting sustainable advancements (Benge and Beattie, 2021; Phillips et al., 2013). Extensionists serve as catalysts for transformation, facilitating community adoption of innovative solutions, improving livelihoods, and promoting well-being (Phillips et al., 2013; Rogers, 2003). Their work focuses not only on knowledge transfer but also on behavioral change and empowerment, enabling local leaders to guide and influence others within their communities (Phillips et al., 2013).

Participants consistently emphasized that their effectiveness as change agents depended on their ability to communicate meaningfully, challenge entrenched norms, and build trust with families. They highlighted the importance of humility, patience, and mutual learning when working with diverse populations. Several noted that fostering change was not simply about imposing information but rather about navigating community values with empathy and respect.

Melissa described the delicate balance between persistence and cultural sensitivity. She explained that success required a respectful approach that acknowledged community dynamics while subtly guiding them toward improvement:

"Well, look, it’s about having a positive attitude. Treating people equally, accepting them according to their circumstances. Because each community is different [...] Sometimes there are people who won’t accept what you say, and they may reject you, but you have to remain impartial and treat everyone the same. Everyone has their own way of being. We have to accept many things, even when we know they’re not right, and if our objective is to create change, we need to gradually work on convincing them […] Being humble, that’s a value. Keeping humility, respect, and understanding."

Her reflection illustrates the interpersonal finesse required to build rapport while gradually influencing behaviors without coercion. Her emphasis on humility and patience underscores the importance of cultural awareness in shaping sustainable change.

Cristina echoed this sentiment, framing her role as a facilitator rather than an enforcer of change: “Our role is to provide technical assistance, to facilitate. We act as facilitators. We help find ways to bring about change in the community and also share the experiences and knowledge that families already have to seek improvements together.”

Her insight reinforces the importance of co-creation in the extension process, highlighting that community knowledge should be acknowledged and integrated into the solutions rather than overlooked or overridden.

Paz added another dimension by emphasizing the long-term goal of behavioral transformation and community organization: “I think one of our roles is to help families change their behavior and also to help gradually build organization within the community, and that’s why we connect with other institutions.”

This comment underscores the systemic nature of extension work. Beyond individual behavior change, she highlights the importance of institutional collaboration and long-term community empowerment. Andrea provided a practical view of change agency by detailing the concrete actions that define her daily work: “Our job as extensionists in the communities is to do home visits, monitor children and pregnant women […] make sure they attend their checkups and that everything is going well with their health. That’s what we do in each community, and through that work, we help improve quality of life.”

Her quote demonstrates that behavioral change often begins at the household level. Personalized support and consistent follow-up help lay the foundation for community-wide improvements in health and well-being. Titi offered a powerful example of the initial resistance she faced and how change occurred gradually through trust-building:

"At the beginning, it’s hard to enter a community as a field technician. I remember when I arrived, people said, ‘She’s collecting information because she wants to steal the children.’ But now, they trust me. They say, ‘Here comes the lady from [Organization].’ They even notify me if there are new babies. That shows how important the role is in the community because you generate knowledge. People tell me, ‘I shared with my neighbor what you told me about feeding the baby.’ It’s a fundamental role that spreads little by little, like a cascade."

Her experience reflects the deeply relational nature of extension work, where time, presence, and trust gradually dismantle suspicion and enable knowledge to circulate organically through community networks.

Together, these voices illuminate the multifaceted identity of extensionists as change agents, not only as knowledge providers but as ethical, relational, and strategic actors. They are tasked with bridging tradition and innovation while fostering environments where communities feel empowered to evolve on their own terms.

Reflecting on the research memos, PL recalled a scenario where Sara visited a community member and assisted her in decorating a chart that illustrated the importance of accessing vegetables. During this visit, Paz emphasized the significance of feeding children and maintaining organization within the household to create positive change for the family. Figure 4 shows Sara sticking an image of vegetable consumption on the wall.

3.2.2 Mentors

Mentorship is a cornerstone of effective extension practice (Hagerman et al., 2022). Extensionists often serve not only as educators and advisors but also as role models embedded within the communities they serve (Schaaf et al., 2020). Their mentorship extends beyond agriculture to areas such as health, education, emotional well-being, and social development. By guiding individuals and families through new practices, helping them navigate personal and systemic challenges, and fostering long-term self-sufficiency, extensionists play a transformational role (Knowles et al., 2014).

Participants emphasized the expansive scope of mentorship they provide, often stepping into multiple roles based on community needs. Carolina shared how extensionists are frequently perceived as problem-solvers for nearly every issue that arises:

“I feel like people see us as if we know everything. The truth is, they say we are leaders, not community leaders, but leaders in the sense that we know everything and can fix their lives. Sometimes, based on the questions they ask us, it’s like they think we know it all.”

This reflection highlights the weight of expectations placed on extensionists, who are often seen as all-knowing figures capable of resolving both technical and personal matters. Their perceived authority is rooted in trust and visibility within the community, but it can also be overwhelming.

Celeste expanded on this by describing mentorship as a form of personalized accompaniment—one that includes emotional support and trust-building. She explained how her role naturally evolved to include health monitoring, early childhood development, and informal counseling:

“We don’t just work with women; we’ve also had to work with men during field days. We have to follow up, make sure they’re going to the health center, that their vaccinations are up to date … and as you gain more trust with people […] you end up guiding them. You have to be a teacher, you have to, as they say, be a psychologist too.”

Celeste’s experience illustrates how mentorship in extension is built on relationships. The more trust is earned, the more community members disclose personal struggles, requiring extensionists to respond with care, knowledge, and emotional intelligence.

Salome reinforced the emotional and practical breadth of their role, describing how mentorship often includes cooking, caregiving, and informal advising:

“I feel like we do everything. I feel like we’re educators, we’re cooks, we’re babysitters too … sometimes the women are working, and we say, ‘I’ll carry your baby for a bit, go ahead and keep working.’ And you talk with them […] you even end up doing counseling.”

Her quote underscores the deeply relational and informal nature of mentoring. Through everyday acts of support, extensionists become trusted confidants, nurturing spaces where both technical and emotional needs can be addressed.

Finally, Paz brought attention to the systemic side of mentorship, emphasizing how extensionists act as bridges to opportunity. She described her role as opening community members’ eyes to resources they previously did not know existed: “It’s like bringing the city to the community […] many times the opportunities are there, but I do not know about them. So through us […] it’s like we help open their eyes to opportunities they can access but aren’t taking advantage of.”

During one of PL’s visits with Fabiana, a community member asked her for recommendations on how to help their children recover from being underweight. Fabiana offered practical ideas and also searched online for the most up-to-date information to provide effective solutions, as can be noticed in Figure 5. Together, these examples illustrate how extensionists serve as dynamic mentors who meet people where they are, adapt to emerging needs, and offer guidance in various forms—whether through teaching, listening, connecting, or simply being present. Their mentorship is rooted in empathy, responsiveness, and a deep commitment to the well-being of the community.

3.3 Research question 3: What are the most effective ways to transfer knowledge to producers?

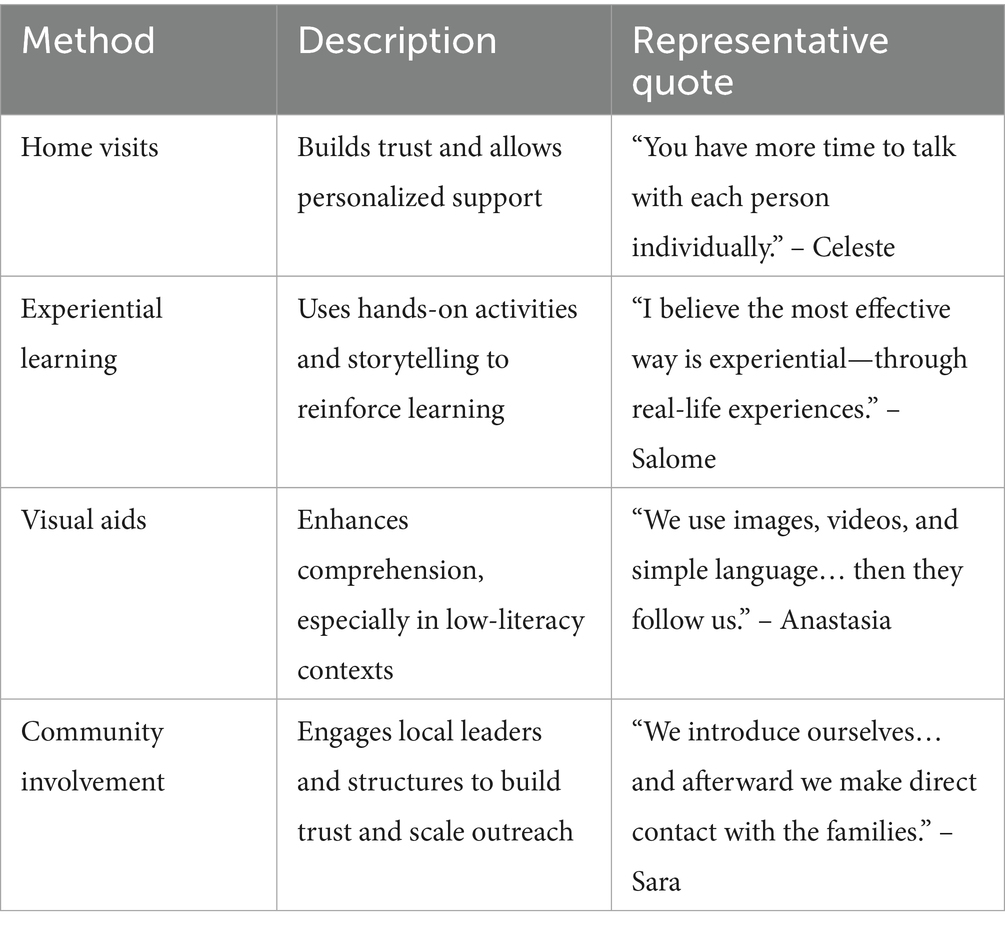

Extension agents were interviewed about the strategies they employ to share technical information and foster behavior change among producers. Across these conversations, participants emphasized approaches that are relational, participatory, and tailored to community realities. Their accounts coalesced around four primary themes: (1) Home visits, (2) Experiential learning, (3) Visual aids, and (4) Community involvement. A description of the four primary methods, with supportive evidence, is provided in Table 4.

3.3.1 Home visits

Home visits are a cornerstone of participatory extension, offering a unique opportunity to foster trust and deliver personalized learning (Arowosegbe et al., 2024). They allow extension agents to understand the lived realities of families and adapt their support accordingly. Unlike group sessions, home visits provide the intimacy and space necessary for meaningful dialogue, behavior change, and relationship-building. As Vanclay (2011) notes, such direct engagement strengthens participatory learning and enhances the relevance of interventions. Through storytelling, observation, and one-on-one conversations, agents deepen their understanding of community needs and create an environment where producers feel seen, heard, and supported.

Celeste articulated the value of this personal connection, emphasizing how home visits provide space for individualized conversations that aren’t always possible in group settings:

“With the visits. Visits, because in each visit, you have more time to talk with each person individually. In a session, it is very nice because you talk about a general topic, and everyone listens. However, when there are several people, one always loses attention. On the other hand, during visits, you can ask about how the child is doing, how the woman is doing, and how the family's nutrition is going. So at that moment, you can also better raise awareness about the educational plan.”

During one of PL’s visits with Sara, we met with 10 families from a community in the highlands. During this time, she provided information about nutrition and how to utilize the resources available in the community effectively. PL observed that the community members were eager for her visit, and they also took this opportunity to ask questions unrelated to nutrition. Sara took advantage of every opportunity to train them and adapt to the community members’ time. In Figure 6, you can see Sara conversing with two community members.

Participants were informed about the best way to diffuse information as part of the interview guide. Similar to Celeste, Fabiana emphasized that effective communication stems from face-to-face dialogue, where the risk of misunderstanding is minimized, and a genuine connection can emerge:

“Through dialogue […]. Talking directly with them. Establishing a conversation directly, not by phone, not by message, because it gets distorted, by visiting them. So when you have a direct conversation, that’s when people start to grasp what we are trying to share.”

This quote reinforces the idea that in-person conversations foster clarity and emotional resonance, which are often lost through more impersonal communication channels. Melissa highlighted how home visits can deliver specialized and dignified care, particularly for pregnant women and families with young children. She underscored how the trust cultivated in these visits leads to a more holistic approach to well-being:

“Where there are pregnant women and children under two years who come to our sessions, we follow up with home visits […]. It's like the attention is a little more specialized, you could say, right? Because it's just the woman and me, right? So it's like […] like the attention is more comprehensive, right? And we call it face-to-face because even she has more trust, so the attention is already different.”

Together, these accounts portray home visits as a strategy and a philosophy of engagement rooted in empathy, trust, and responsiveness. Whether addressing nutrition, health, or hygiene, extension agents leverage these visits to cultivate authentic relationships, meeting families where they are and co-creating pathways for sustainable change.

3.3.2 Experiential learning

Experiential learning, through hands-on approaches like demonstrations, participatory exercises, and storytelling, enhances knowledge retention and practical application. This method aligns with adult learning principles, prioritizing learning by doing and building on participants’ lived experiences (Kolb, 1984). Extension agents use culturally appropriate language and relatable examples to increase accessibility and participant engagement. Titi, for example, reflected on the importance of co-constructing knowledge with families rather than imposing it:

“I feel the most effective way is to build knowledge collaboratively [...] When we build from their base, we’re reinforcing what they already know, and their reaction is: ‘Oh, so I wasn’t completely wrong, I just need to improve a few things’. For me, the best approach is to build from what they already know, especially since there’s so much culture here. For example, it’s common to give babies herbal teas... so we say: ‘Don’t give it directly to the baby; drink it yourself and it’ll pass through your milk’, instead of saying ‘you’re going to kill your child.”

Titi’s reflection highlights how experiential learning can be respectful, constructive, and rooted in empathy. Instead of shaming or correcting participants, agents can build on existing knowledge to encourage growth and change. Salome echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the power of personal storytelling and lived experience in encouraging openness and learning:

“I believe the most effective way is experiential, through real-life experiences. For instance, when we talk about malnutrition and the quality and variety of food, I share stories because it’s something we all struggle with. I tell them, ‘I have three children, all born prematurely. The first two suffered from acute malnutrition and were hospitalized.’ I also share stories I’ve heard in the communities: ‘In such-and-such village, this happened to this woman […]’ And when I do, people open up. They say, ‘Yes, you’re right. Ever since I started giving my daughter eggs, she’s doing better,’ or ‘We’ve started adding milk to the atole [a traditional Central American hot beverage typically made from corn flour, water, and milk], and now she drinks it more.’ People start sharing their experiences, and when they hear that something worked for someone else, they think, ‘If it worked for her, it might work for me too.”

Salome’s strategy demonstrates how lived examples, not abstract theories, resonate deeply, opening space for reflection, conversation, and peer learning. Storytelling, especially when grounded in vulnerability, helps participants connect to the content and to each other. Melissa described how experiential learning is embedded in community activities she facilitates, specifically through cooking demonstrations that help families explore and adopt healthier diets:

“We call them ‘Good and Bad Educational Decisions.’ That’s when we gather the producers' families, especially the women, to hold educational talks and do real-life food demonstrations. Our goal is to promote a more diverse and nutritious diet. So we prepare a recipe during the session, and we’ve found that this is when they really learn. They take what they see and put it into practice at home. It becomes a real channel for knowledge transfer.”

Melissa’s account underscores how experiential learning not only promotes understanding but also encourages action. When participants physically engage in the process, seeing, tasting, and preparing food themselves, they are more likely to replicate those behaviors at home.

During one of PL’s visits with Melissa, we participated in a session focused on preparing healthy dishes, as can be seen in Figure 7. Melissa shared various techniques and recipes that can be made using local resources. PL observed that she worked closely with community members, emphasizing the importance of boiling water and consuming nutritious food. This experience helped me recognize how she integrated servant and transformational leadership, while also creating opportunities for experiential learning, allowing them to practice what they had learned during the sessions.

3.3.3 Visual aids

The use of visual aids such as images, drawings, and demonstrations was described as a critical strategy to overcome literacy barriers and enhance comprehension. These tools, especially when paired with relatable language and hands-on practice, were viewed as essential for making information accessible and actionable.

Anastasia described how using visual tools, such as posters, flipcharts, and videos, along with demonstrations, significantly improved women’s understanding of technical concepts. She emphasized that this multimodal approach not only clarified abstract ideas but also helped sustain participants’ interest:

“With images and examples, we achieve a more effective level of learning, especially with women. It helps them understand better because we’re not just explaining, they’re also seeing it. And when they practice it, the learning becomes even stronger. We use images, videos, and simple language adapted to their level so they can understand. If we just show up with theory, they get bored or don't understand, but if we make it visual and practical, then they follow us.”

Sara echoed the value of using visuals in contexts where written materials are often inaccessible due to low literacy levels. She described how visual and tactile methods allow families, particularly women, to actively engage and replicate techniques in their own homes:

“The families can’t read [...] so to convey information, we use drawings, images, and hands-on practice. With the women, we go step-by-step so they can follow along, see how it’s done, and then do it themselves. The visual part is very important, because if we just tell them, it doesn’t stick. But if they see it, do it, and repeat it, they learn.”

Cristina provided insight into how visual learning strategies are most effective when rooted in trust and open communication. She explained that by using an andragogical approach and being approachable and friendly, she creates a safe learning environment where women feel comfortable asking questions and engaging with the material:

“When I work with families, I use an andragogical approach that facilitates learning. I communicate in a close and friendly way, I’m very sociable, I talk to them, I listen to them, and that builds trust. That trust allows me to use images, visual materials, and practical activities. And when they feel that respect and openness, they understand better. They feel encouraged to participate and say what they don’t understand, and that makes learning more effective.”

During a visit with Anastasia, PL observed that she utilized visual aids to train the women in the community. These materials made the information more digestible, helping to bridge the gap between the literature and the community members. Figure 8 shows the visual aid used by Anastasia.

Together, these reflections highlight that visual aids are not simply pedagogical tools; they are part of a broader relational strategy. When paired with culturally grounded communication and trust-based facilitation, visual methods enhance comprehension and empower participants to apply what they learn in real-life settings. Extension professionals who adopt these practices help bridge the gap between knowledge and action, particularly in communities where formal education is limited or undervalued.

3.3.4 Community involvement

Partnering with community leaders, cooperatives, and family units strengthens knowledge dissemination and encourages collective action (Kania and Kramer, 2011). Involving diverse stakeholders fosters inclusive participation and enhances trust in extension efforts (Pretty, 2003). Participants emphasized building relationships with existing community structures and adapting engagement strategies to local dynamics.

Cristina explained that organizing meetings allows couples and local leaders to engage collectively in decision-making processes, which is essential in contexts where individual engagement may be limited or discouraged. She highlighted how these gatherings become spaces for sharing information, fostering inclusion, and building shared understanding:

"The easiest way to share information is through meetings [...] It’s a bit difficult to do it individually because each group has a leader, and people sometimes fear making individual decisions out of concern for how the leader will perceive it. So, it’s better to do things in a group setting, with both the leader and the couple present."

Paz recounted her experience comparing two projects, one where outreach was difficult due to a lack of coordination, and another where working through local authorities and health professionals facilitated trust and acceptance. She emphasized that prior communication with respected leaders made a significant difference in how households received them:

"Previously, when I worked with another institution, it was more complicated because people often were not interested in coordination [...] However, this project was easier because we already had a list of the people we needed to visit. We coordinate among colleagues or send someone to visit directly, and they welcome us because they already know the group. In some communities, we also work with Agua para la Vida. First, we contact local authorities like trainers or mayors. We introduce ourselves and explain the project's purpose and who we will work with. Then we visit the health center because they have information about the population and the group we want to reach [...] So people already know about our visits and are not as afraid to share information with us."

Anastasia discussed how coordination begins with other project staff or organizations, such as local agronomists or NGOs, to establish initial credibility. From there, meetings with community leaders serve to introduce the project methodology and secure local support:

"First, there is coordination with the other technician, the agronomist, or Agua para la Vida [Field technician focused on promoting clean water]. We call for a meeting if they have contacts with community leaders or the deputy mayor. There, we explain the methodology, the project, and what we hope to work on in the community. That is how we open doors and receive support so that community leaders can accompany us and help with visits to the families we want to work with."

Finally, Sara emphasized the importance of working with organized community structures such as cooperatives and associations, which already have established lines of communication. This structured entry allows for smoother introductions and stronger relationships with the families:

"Here in Ixil, there are already established associations and cooperatives. So we connect with those associations to serve the families they already work with. They have promoters in each community. Sometimes we hold an assembly or meeting where leaders gather so we can introduce ourselves, and afterward we make direct contact with the families because we’ve already been introduced by the group president or promoter."

These diverse voices underscore how community involvement is not a passive byproduct of outreach but an intentional, relational process. Trust is cultivated through presence, transparency, respect for local leadership, and acknowledgment of mutual learning. When extension professionals genuinely engage with community structures and culture, they increase the likelihood of sustained participation and impact.

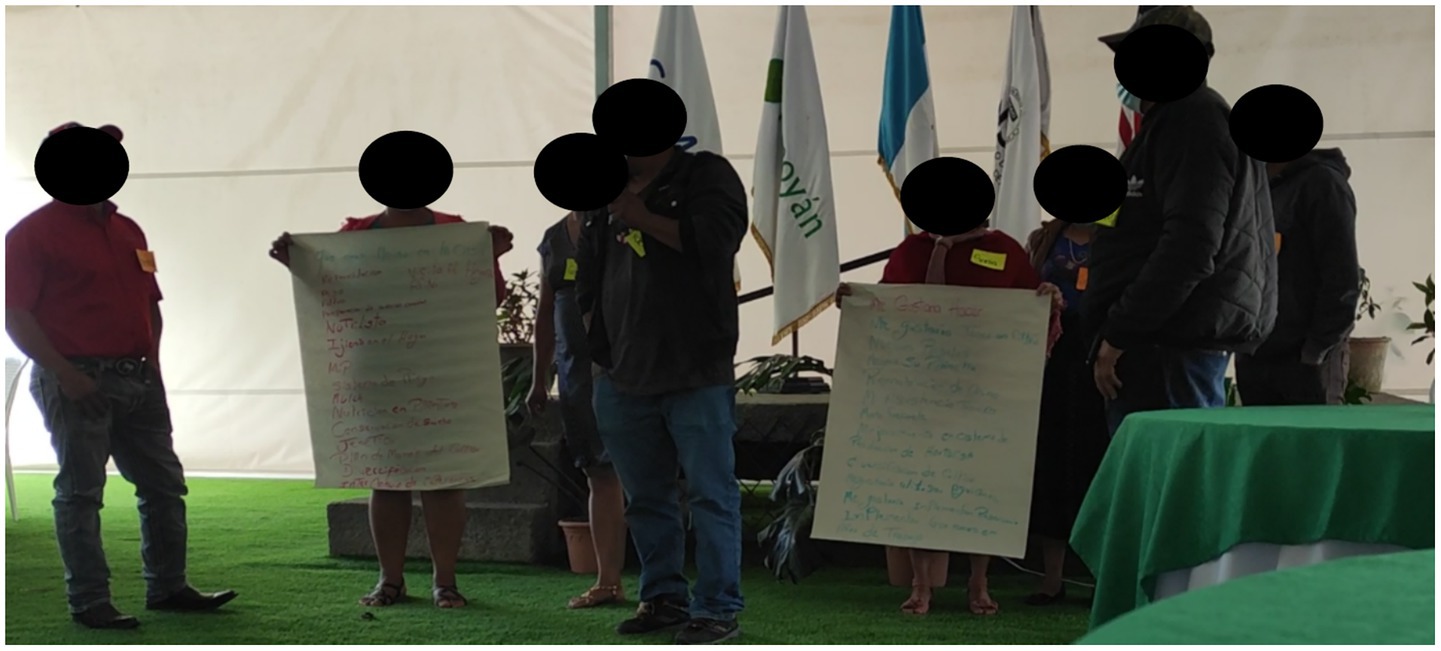

PL attended a meeting where various community leaders were invited to share their needs and perspectives on improving the community. It was clear that extension agents focused on building relationships with the audience they served and the entire community, as this could lead to better approaches. Figure 9 shows an image of community leaders sharing their insights regarding community needs.

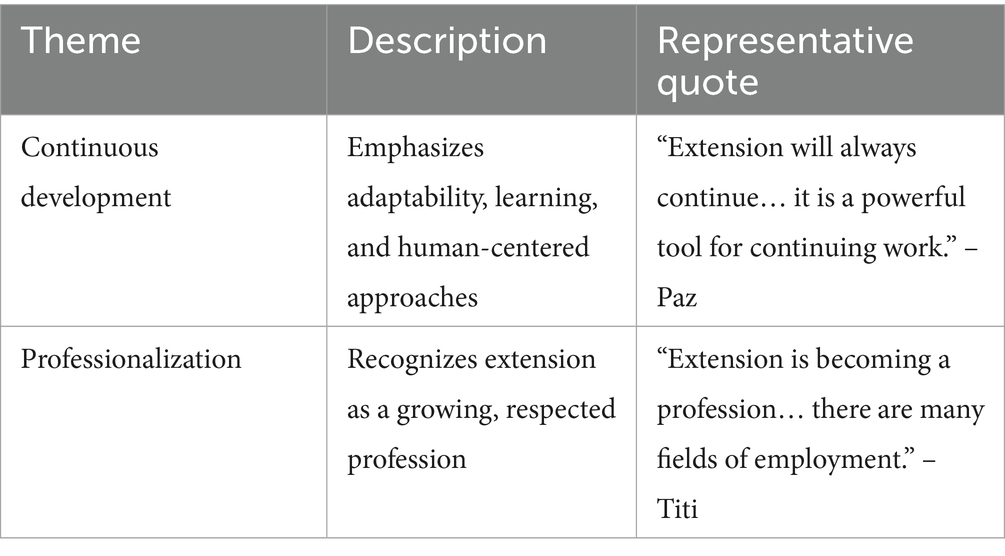

3.4 Research question 4: What is the expected future of extension in Guatemala?

Extension agents were interviewed about their perspectives on the future of extension in Guatemala. While their outlooks varied, participants generally expressed a sense of cautious optimism. They viewed extension as a promising, evolving field with potential for deeper community impact, greater professional recognition, and broader inclusion. Their reflections centered on two primary themes: (1) Continuous development and (2) Professionalization of extension work. A description of the two emergent themes, with supportive evidence, is provided in Table 5.

3.4.1 Continuous development

Participants viewed the future of extension in Guatemala cautiously, emphasizing its potential for growth, adaptability, and deeper community engagement (Benson and Jafry, 2013). While recognizing existing limitations, especially in access to education and infrastructure, many expressed hope that extension would continue to evolve as a transformative tool, particularly for rural and underserved populations. Themes of community empowerment, women’s leadership, and the enduring need for human-centered approaches were consistently highlighted.

Paz reflected on the importance of preserving the humanistic dimension of extension work. She noted that although technology and communication tools have become more widespread, these advancements cannot replace the value of personal connection and empathy in community engagement. To her, extension will remain a key strategy for development if practitioners stay grounded in these principles:

“Extension will always continue; it will remain a strategy. Different organizations and projects will keep working through it. And honestly, even though we now have more active media and communication channels, there is still something missing: the human element. Ultimately, I believe that the true purpose of extension is to be a human-centered strategy. If we know how to use it well, it is a powerful tool for continuing work in communities, both here and in any country.”

Celeste offered a gendered lens on the future of extension, noting the progress that women have made in asserting themselves and seeking leadership opportunities. She acknowledged a growing shift away from traditional submissiveness and toward greater participation. Her hope is that extension will continue to evolve as a vehicle for women’s empowerment:

“How do I see the future of extension? I think we’re on the right path. Women today are no longer as submissive as before; we’ve woken up and we’re actively seeking opportunities. And when we get them, we try to make the most of them. I sincerely hope that in the future things will improve, and that women will have more opportunities and become more visible.”

Salomé expressed confidence in the lasting impact of extension work. She highlighted the role of extensionists as trusted facilitators who bring knowledge directly into communities and help ensure its application and replication:

“In relation to this project, I see it going very well. It’s been successful, and I think it will continue to be. The work we do as field extension technicians gives us access—people absorb the knowledge, put it into practice, and then replicate it.”

Melissa reflected on the ability of extension to reach communities long overlooked by formal education and development programs. She emphasized how this outreach contributes to empowerment and local acceptance of extension as a valuable and necessary resource:

“Many specialists have reached places where education and development simply don’t arrive. They’ve been able to reach those important areas. Many times, they’ve trained people on various topics, and now, it seems that people have become empowered and have embraced extension—especially in some communities, it’s working really well.”

Together, these reflections underscore a shared belief in the ongoing relevance and adaptability of extension in Guatemala. While each participant emphasized different aspects, human connection, women’s empowerment, technical success, or rural outreach, all pointed to extension as a strategy capable of evolving to meet the shifting needs of communities. Notably, the success of this future vision appears to depend not only on technical skills but also on relational leadership, inclusivity, and a long-term commitment to equity and empowerment.

3.4.2 Professionalization of extension work

Participants highlighted the growing legitimacy and recognition of extension as a formal profession in Guatemala (Benson and Jafry, 2013). No longer seen merely as volunteer-driven or ad hoc support work, extension is increasingly valued for its structured methodologies and multifaceted impact across fields such as education, nutrition, and rural development (Yang and Ou, 2022). This professionalization has opened new employment pathways and increased the visibility of extensionists as key actors in community transformation.

“I do see commitment, a real dedication from the people I know who are involved in this work. They give themselves fully to what they do, with both commitment and desire. As time goes on, I see more people getting involved. For example, in our case, there are five of us, but when I’m out in the field, I notice even more people working toward the same goal. You even start building networks with them. I see more and more people in the field, all working for the well-being of others.”

Titi pointed to the increasing number of job opportunities as evidence of the extension’s growing institutional value. She emphasized that extension is no longer limited to agricultural settings but has become integral to various projects across Guatemala. This expansion into fields such as education and nutrition signals a broader professional scope:

“I see this heading in a very positive direction. I truly believe extension is becoming a profession. Over time, I’ve seen more and more job opportunities opening up for extensionists, not just in nutrition or with producers, but in a variety of development projects throughout Guatemala. There are many fields of employment. So yes, I think this extensionist methodology works across different sectors like education, nutrition, and development.”

Andrea offered a more personal and forward-looking perspective. She described how extension drives visible transformations not just in individuals, but across entire families. For her, this signals a hopeful and improving future, in which extension will continue evolving as a legitimate and impactful profession:

“The way I see the future, it's a beautiful one, I would say. Because we’re already seeing changes, real transformations happening in people, not just individuals, but whole families. So, how could I not say it? In the future, I wouldn’t say it will be perfect, but yes, it will definitely improve, much better than what it is now.”

Together, these insights paint a compelling picture of how extension work is evolving in Guatemala, from a loosely defined support role to a respected professional pathway with tangible impacts. The increase in field presence, the rise in employment opportunities across multiple sectors, and the visible transformation of community life all contribute to a sense that extension is growing and becoming a vital part of the country’s development infrastructure.

As part of PL’s contributions to the time he spent with them collecting data for this research, PL conducted a training session on Gender in Agriculture. During this session, PL asked participants to engage in role-playing exercises to illustrate the challenges they face in their roles. Some issues they faced were the need to navigate with participants’ husbands. After the role-playing, they emphasized the importance of ongoing training and education to enhance and share their knowledge with others. In Figure 10, you can see the discussion after the role-playing, where they documented actions to improve their community service.

4 Discussion

Findings suggest the need for extension models that prioritize human-centered, gender-sensitive, and participatory approaches. This emphasis on inclusive and responsive extension models is further reflected in how participants described leadership as closely tied to character and the need for responsible leadership by example, highlighting the value of informal leadership development. Field technicians serve as essential change agents, particularly in preventing undernutrition in families, showcasing their potential to promote positive behavior change. Additionally, they assume the role of counselors, addressing violence and household issues, revealing a need for holistic support. The preference for female field technicians in female-led households underscores the importance of gender-sensitive approaches in agricultural extension services, with field technicians adapting to this dynamic and demonstrating their commitment to enhancing understanding and resource access for female producers.

Results from the first research objective are related to a relationship-oriented approach, transformational growth adoptions, and servant leadership styles by extension workers, enhancing the ability to build trust, foster collaboration, and empower community members. The leadership styles observed in this participant study suggest that extension systems should invest in leadership development programs that cultivate emotional intelligence, cultural competency, and collaborative problem-solving. These approaches improve the effectiveness of extension programs and also promote sustainable community development by encouraging participatory decision-making and continuous personal and professional growth among leaders and community members alike. This is supported by the principles of transformational leadership, which emphasize self-awareness, resilience, and the ability to navigate change effectively (Bass, 1990; Burns, 1978), as well as the core principles of servant leadership, which prioritize the growth and well-being of individuals and communities (Liden et al., 2008). These findings correspond with existing research that highlights how leadership grounded in moral character and interpersonal trust can enhance public value in extension systems. For instance, relationship-centered leadership has been shown to support inclusive decision-making and build cohesion between group members (Tabernero et al., 2009). The emphasis on serving others, a key trait observed among participants, reflects core principles of servant leadership, which have been documented to increase community engagement and adaptive capacity in complex environments (Greenleaf, 2013; Liden et al., 2008). Similarly, transformational leadership’s focus on motivation and growth aligns with how extension agents in this study fostered resilience and development within their communities (Bass, 1990; Burns, 1978). Collectively, these parallels reinforce the role of values-based leadership in promoting sustainable, community-driven change in extension contexts.