- 1Center for Development Research, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

- 2Institute of Crop Science and Resource Conservation, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

- 3University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana

- 4West African Science Service Center on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

- 5Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

We conduct a systematic review to explore the state of knowledge on participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management in Africa, the extent to which women and other marginalized groups are engaged in the collective development processes, and how gender issues are addressed. Grounded in gender and social inclusion concepts, guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA), and using Scopus and Web of Science databases, we discover a modest and fluctuating growth in participatory and social learning research since 2005. However, many participatory studies, do not address specifically collective learning and reflection nor integrate gender. For those with in-depth gender focus, multiple approaches are adopted for stakeholder selection and engagement, enabling a detailed reflection and integration of gender dimensions in co-developing solutions. It is crucial for participatory studies to be socially inclusive and gender sensitive, and address power dynamics, which are necessary to alter gender relations and norms, tackle inequality, and enhance agency at the household and community levels.

1 Introduction

The complex nature of contemporary development challenges, such as climate change, land degradation, low soil fertility and agricultural productivity, food insecurity and population growth, requires participatory and stakeholder-driven approaches to tackle these challenges (Barreteau et al., 2010; Bentley Brymer et al., 2018; Lelea et al., 2014). Researchers, policymakers and development practitioners are increasingly responding to the call for effective multistakeholder approaches in dealing with complex challenges (Kotir et al., 2024; McNaught, 2024; McNaught et al., 2024). This is because classical top-down development approaches have been ineffective and often exclude the experiences, knowledge, preferences, and contextual needs of beneficiaries in the development processes (Chambers et al., 1989; Chambers, 1994; Steyaert et al., 2007), partly accounting for the low adoption of agricultural innovations or ineffective development interventions (Stevenson and Vlek, 2018; Kosmowski et al., 2020).

In sub-Saharan Africa, pervasive inequalities in the agriculture and natural resource management sectors that support the livelihoods of the poor, vulnerable and marginalized population, make participatory, co-creation and co-development approaches paramount (Egunyu and Reed, 2015; Elias et al., 2017; Tavenner and Crane, 2019). Yet, there is not enough information on the extent to which these approaches promote gender and inclusion, which we seek to address through a systematic review. Agriculture is the backbone of many African economies and serves as the main source of gross domestic product, employment, foreign income and food security strategies. Scoones (2009) highlights its instrumental role in rural development and the livelihoods of the rural poor who constitute the majority of the sector’s labor force. Yet, prevailing inequalities perpetuated by sociocultural norms and values hinder effective participation and fair distribution/generation of benefits, particularly for women. Women are often disadvantaged compared to men in the agriculture and natural resource sector due to associated norms, roles and responsibilities (Beuchelt and Badstue, 2013; Nischalke et al., 2017; Asare-Nuamah et al., 2024; McGuire et al., 2024a). Asymmetric power relations, exclusion from essential decision-making processes, limited access to and ownership of essential resources, such as land, technology, credits, extension services etc., hamper women’s participation in agriculture (Yaro, 2010; Britwum et al., 2014; Tsikata and Yaro, 2014; Nischalke et al., 2018; Kabeer, 2020; Britwum, 2022; Tseer et al., 2024). Providing the needed resources to women and empowering them to participate effectively in agriculture can contribute to enhancing food security, reducing poverty, and promoting sustainable agricultural transformation. If not addressed, persistent inequalities against women and other marginalized and social groups can hamper sustainable development (Paris et al., 2008).

Participatory approaches, including social learning, can serve as tools to leverage and promote women and other marginalized groups’ participation in agriculture, land and natural resources management, address poverty and strengthen inclusive policy and decision-making processes (Muro and Jeffrey, 2008; McDougall et al., 2013b; McDougall et al., 2013a; Farnworth et al., 2022). The literature highlights the immense contributions and impacts of women’s participation in participatory and social learning processes in Ghana, Tanzania, Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Zambia, Uganda and other African contexts (McDougall et al., 2013b; McDougall et al., 2013a; Lindley, 2014; Shaw and Kristjanson, 2014; Restrepo et al., 2016, 2018; Richardson-Ngwenya et al., 2018; Cronkleton et al., 2021; Phiri et al., 2022). This is because women, just like men, are critical change agents for sustainable agriculture and land management. For instance, women’s roles in afforestation, sustainable harvesting and use of fuelwood contribute to tackling climate change, and promote sustainable natural resource management (Egunyu and Reed, 2015; Nchanji et al., 2017). Similarly, in Burkina Faso, women’s agroecological knowledge enhanced traditional crop species’ resilience and sustainability to climate and environmental changes (Karambiri et al., 2017). In effect, women’s participation in social learning brings new perspectives and gendered dimensions due to their gendered roles and sociocultural experiences in society, which greatly influence social learning processes and outcomes (Egunyu and Reed, 2015; Elias et al., 2017; Hegde et al., 2017; Kabeer, 2020). Purposively including women’s voices and experiences in research and development projects contribute to altering norms, values and behavior necessary for sustainable development (Nischalke et al., 2017; Cornish et al., 2021; Asare-Nuamah et al., 2024).

Notwithstanding, existing evidence shows that many participatory approaches continue to perpetuate gender inequality as women and other marginalized groups are often excluded (Swan et al., 2009; Egunyu and Reed, 2015). Twyman et al. (2015) associate women’s exclusion in social learning to the gender-blind nature of many participatory approaches. Also, patriarchy, cultural norms, and unequal power relations account for the exclusion of women and other marginalized groups (Cornwall, 2003; Wagle et al., 2017; Evans et al., 2021). Similarly, women and other traditionally under-represented groups can be intimidated in multi-stakeholder learning spaces, limiting their participation (McDougall et al., 2013b). Furthermore, inadequate stakeholder selection (Johnson et al., 2004) and stakeholder selection bias (Twyman et al., 2015), hinder women’s active participation in social learning.

An emerging number of studies have reviewed gender in participatory and social learning research (see Johnson et al., 2004; Kristjanson et al., 2017; Shaw and Kristjanson, 2014; Swan et al., 2009; Tschakert et al., 2023). For instance, one of the earliest reviews on gender in participatory research focused largely on research projects from a global perspective which may have excluded other important studies in Africa that are not project-based (Johnson et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the authors strengthened the discourse on women’s participation in participatory research. Kristjanson et al. (2017) and Shaw and Kristjanson (2014) limited their scope to CGIAR (2024) research projects that embraced gender in participatory research designs, such as the Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security. Tschakert et al. (2023) also reviewed gender and diversity in participatory learning approaches with the aim to contribute methodologically to addressing power imbalances in participatory learning. The authors note that even research designs and settings that claim to be inclusive show pervasive power differences, which disempower and marginalize disadvantaged groups. There is, however, a limited knowledge on the extent to which participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management in Africa has evolved, how gender issues are integrated and addressed as well as the approaches that facilitate the integration of gender in participatory and social learning.

This study explores the current state of knowledge on the inclusion of gender aspects in participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management in Africa. Specifically, we address the following research questions: (1) How has gender and inclusion in participatory and social learning research in Africa evolved and influenced by gender-related global development landmarks? (2) What contextual issues motivate gender and inclusion in participatory and social learning research in Africa? (3) What approaches facilitate gender and inclusion in participatory and social learning research? (4) How much are gender issues discussed and/or addressed in participatory and social learning research and what are the outcomes? We focused on participatory studies that provided an inclusive and safe space (i.e., dialogue, deliberative and reflective processes that adopt democratic values including respecting individual’s rights and views, freedom of expression, voluntary participation etc.) for learning and reflections. The structure of the paper is as follows: section 2 explores the theoretical underpinning of the study, section 3 describes the research methods; section 4 presents the findings, which are then discussed in section 5 while section 6 concludes the study.

2 Theoretical background

This article used gender, social inclusion and social learning as the theoretical anchor. Social inclusion is about not excluding people in collective action and development based on their identity, such as age, gender, sexuality, race, religion, class, disability etc. (Gidley et al., 2010; Mansouri and Lobo, 2011; Huambachano et al., 2025). Social inclusion dwells on diversity and propagates the inclusion of people with diverse experience, views and identities in driving collective action. It prioritizes the degree at which marginalized, deprived and underrepresented communities and groups, including women and youth, are engaged and included in addressing challenges that affect their lives. Social inclusion is grounded in social justice and right-based approaches, and aims at empowering underrepresented groups for collective action and decision-making (Cornwall, 2003, 2016; Gammage et al., 2016; Kabeer, 2020). Thus, it offers an opportunity for these groups to benefit from the processes, structures and systems which they previously had limited or no access to. Essentially, social inclusion empowers women and marginalized groups to overcome constraints to their effective participation in agriculture and natural resource management.

Gender constitutes socially prescribed roles and identity assigned to women and men in a given society (Kabeer, 1999, 2005). The socially prescribed roles and identity determine what women and men can and cannot do, and the forms of power and resources available and exercised by them in a society. This disposition among men and women shows their capacity and vulnerability levels, revealing the (dis)advantage and unique positions of each gender in a society. Gender and social inclusion focus on tackling challenges that seem general but exert differentiated impacts on different gendered groups. For example, climate change, agricultural productivity, food security, land and resources access etc. are challenges that affect larger population but with uneven impact on different individuals/groups. Also, issues of power, hierarchy and gender relations dictate how different groups, including women, participate in agriculture. Specific to power, four forms of power are crucial for men and women’s agency, resources and achievement in collective decision and agricultural participation: power over, power to, power with and power within (Rowlands, 1997; Kabeer, 1999; Alkire et al., 2013). ‘Power over’ constitutes a form of empowerment where individuals exercise control over others including resources while ‘power to’ deals with being able to make decisions related to choices out of available alternatives and options. ‘Power with’ implies collaborative empowerment where individuals collectively exercise their power while ‘power within’ constitutes the ability to induce or cause a change in one’s life (Kabeer, 1999; Galiè and Farnworth, 2019). The different forms of power are crucial for empowering women and vulnerable groups, and enhancing their participation in collective decision-making (Alkire et al., 2013). Hence, gender sensitive approaches promote the need to consider the unique positions, challenges and experiences of women and other marginalized groups in collective action (Lopez et al., 2023). Social inclusion aligns with social differentiation approaches which emphasize understanding and paying attention to certain groups’ roles, shared knowledge, and contexts in addressing common challenges within a particular system (Shaw and Kristjanson, 2014).

Participatory action research places farmers or beneficiaries at the center of collective action (Chambers et al., 1989; Scoones and Thompson, 2009). Participatory action research builds on the assumption that diverse forms of knowledge are crucial in addressing challenges in a particular context, and participants within the context must play active roles in tackling the challenges. Thus, local participants have rich knowledge and experiences that can contribute to the development of sustainable and context-specific solution. Essentially, participatory action research argues for the active and not passive participation of local actors in addressing challenges that affect their daily lives (Darnhofer et al., 2012; Christinck and Kaufmann, 2017). It recommends developing solutions with local actors and promotes bottom-up approach and not the traditional top-down approach to development.

Participatory and social learning research aligns with the ideals of participatory action research and deals with addressing complex socio-ecological challenges, making gender and social inclusion crucial. Reed et al. (2010) outline three distinct characteristics of social learning that align with social inclusion: (1) social learning brings about a change in practices and understanding; (2) the impact of the change manifests beyond small groups and individuals; and (3) the change occurs through learning among social networks. Shaw and Kristjanson (2014) also denote that the context within which social learning occurs, how interactions among different actors are managed, the form and purpose of learning (i.e., addressing technical and practical problems as against exploring the underlining conditions including norms and values associated with a problem), the channels for mobilizing and disseminating knowledge (i.e., networks, partnerships, collaborations etc.), and the development outcomes from the learning process are essential features of social learning. From the above discussion, the adopted theoretical framework allows us to explore the extent to which different groups, including women, resource poor and marginalized, with diverse identities, are included in participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management in Africa, and how their unique and gendered challenges and contexts are integrated and addressed.

3 Methods

3.1 Study design

The study adopted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021; Parsons et al., 2024). PRISMA is widely used in systematic reviews to provide an in-depth state of knowledge on a particular phenomenon or research interest (Castellini et al., 2025; Mkumbukiy et al., 2025). Given its ability to show past and current trends and development in a particular field, it is a robust, transparent, systematic, reproducible and reliable approach (Page et al., 2021). No prior protocol registration was performed, our systematic approach follows PRISMA guidelines in full and is transparently described below.

3.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria and information sources

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were pre-determined to guide the retrieval of relevant information for the study (Supplementary Table 1). For inclusion in the study, the research must have been (1) conducted in Africa with a particular focus on agriculture, land and natural resource management including climate change; (2) applied participatory and social learning approach(es); and (3) prioritized or focused on gender. Specific to the timeframe, we concentrated on 1970 to date given that women in development began to gain attention from the 1970s and by 1980s alternative visions for gender and development had emerged, further influencing the UN Conference in Beijing (1990s), the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Lopez et al., 2023). We used Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases for the search and retrieval of documents. These databases have been widely used in many systematic reviews as relevant, reliable, and valid sources of information (Williams et al., 2018, 2021; Beuchelt and Nassl, 2019; Amofa et al., 2023; Asare-Nuamah, 2023; Parsons et al., 2024). They offer a comprehensive identification and retrieval of relevant information from diverse sources. We included different types of documents, such as empirical research articles, conference proceedings, notes, books and book chapter indexed in the databases. However, documents that focused on participatory approach and gender but from different perspectives, such as addressing gangsterism, or did not focus exclusively on Africa (e.g., Lopez et al., 2023) were excluded. Also, review papers were excluded, and we prioritized documents written in English. Given that we prioritized documents written in the English language, we did not conduct any further search in non-English databases or journals, which is accepted under the PRISMA guidelines.

3.3 Search terms and boolean operators

Keywords were pre-determined to enhance effective search and retrieval of relevant information. Given that many studies employ different participatory approaches we considered the need for the keywords to represent studies that used any of the participatory approaches. The keywords used included “social learning” and “participatory action research” since they are often mentioned or used in many of the studies that adopt participatory approaches as well as “gender” “agriculture” “land management” and “natural resource management.”

Boolean operators were applied to the keywords to ensure effective literature search. Given that social learning and participatory action research are often used interchangeably in the literature, we used the OR operator to ensure all documents containing any or all of these keywords were identified. Again, we applied the OR operator for agriculture, land management and natural resource management. The AND operator was used to join the keywords together (i.e., “social learning” OR “participatory action research” AND “agriculture” OR “land management” OR “natural resource management” AND “gender”). We applied the “TITLE-ABS-KEY” search field in Scopus while in the case of WoS, the keywords were applied to the “Topic” search field.

3.4 Search strategies and data management

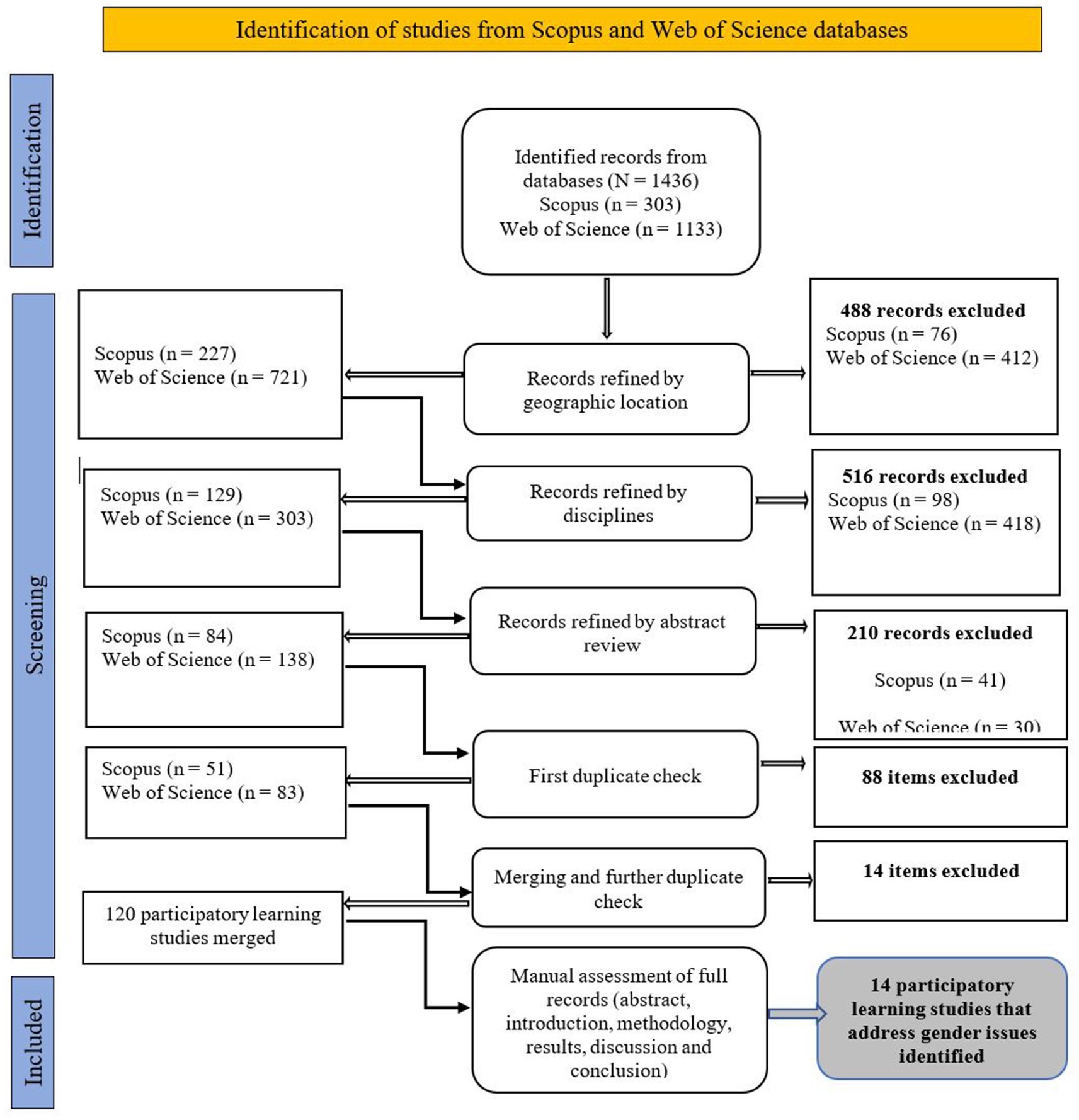

We searched the databases in July 2024 and retrieved 1,436 documents from Scopus (303 records) and WoS (1,133 records). Following the PRISMA guidelines (see Figure 1), the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. We first refined the identified items focusing on the geographic location of the study. Studies that were out of the scope of the study area (i.e., Africa) were eliminated from the identified documents, resulting in 948 items retained (WoS = 721, Scopus = 227), representing 66% of the identified items.

Secondly, we focused on eliminating documents from unrelated disciplines. For instance, using WoS subject categories, we eliminated studies from Biological Sciences, Arts and Humanities, leading to 303 items retained in WoS database. In the case of Scopus, 129 items were also retained after applying subject-focused elimination criterion. The abstracts of the retained items were further reviewed to gain a first-hand knowledge of the studies. It emerged that some of the retained documents were not related to Africa (e.g., studies from Australia, Sweden, China, United States of America etc.) or focused on different research areas (e.g., street violence, gangsterism, sexual orientation, feminist history, education, etc.). These items, totaling 210 were excluded from the databases.

For the remaining 222 items (84 from Scopus and 138 from WoS), duplicates were manually excluded based on their titles, resulting in 134 items retained. These items were downloaded as Research Information Systems (RIS) and Comma Separated Values (CSV) files. The RIS file was then transported into Mendeley Reference Manager (Mendeley, 2022) to aid in the merging of the documents while also checking for duplicates. At this point, 14 documents were further excluded, and also deleted from the CSV file. In the end, 120 documents were retained. All the 120 documents were downloaded in Portable Document Format (PDF) for thorough scrutiny. The abstracts, introduction, methodology, results, discussion and conclusion sections of the documents were thoroughly reviewed to determine their suitability for inclusion.

3.5 Data analysis

Following the thorough review of the 120 papers, it emerged that all the papers applied participatory approaches. However, given that we were interested in participatory studies that provided an inclusive and safe space for learning and reflection (a key feature of social learning), and included gender, only 14 of the papers met the criteria for in-depth analysis. These criteria included (1) the study provides democratic and safe space for social learning (reflections, exchange of information, knowledge and experiences), (2) actively includes and engages women and other social groups in the learning process to frame the problem and identify solutions, (3) issues that affect women and other groups with respect to the problem and the solutions are discussed and/or addressed.

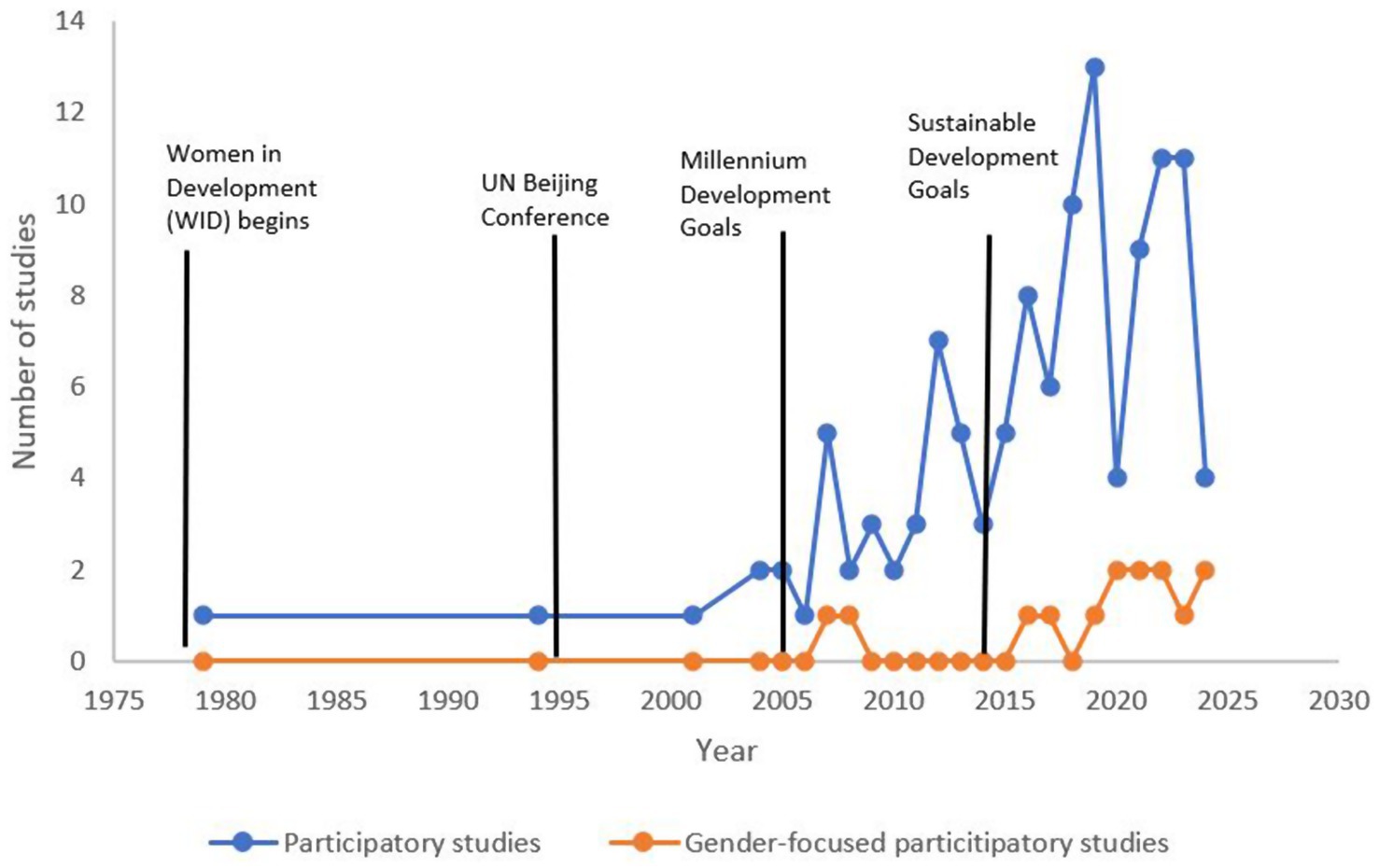

For research question 1, a trend analysis was performed in Excel to explore how participatory research has evolved generally (from the 120 documents) in Africa vis-à-vis participatory learning studies that integrated and addressed gender issues (the 14 documents). We included all the 120 identified papers only in the trend analysis to enable us to make a case for the need to strengthen gender integration in participatory learning research. Major global events that have contributed to the integration of gender in development discourse (Lopez et al., 2023) were transposed onto the trend analysis graph to gain an in-depth understanding of how they might have influenced the integration of gender in participatory research.

The analysis for research questions 2–4 were restricted to the 14 identified documents. For research question 2, we followed Shaw and Kristjanson (2014) who argued that social learning tenets involves understanding stakeholder’s contexts. We hypothesized that exploring the context under which the identified studies were carried out will offer insights into how the prevailing conditions in the contexts influence and justify gender inclusion in participatory learning. We manually identified the contextual issues reported in each of the studies’ introduction, methodology and results sections (Supplementary Table 2 provides an overview of the 14 studies based on the research questions). Regarding research question 3, the stakeholder engagement approaches that facilitate both social learning and gender integration were extracted from the identified records. The identified themes for this included how stakeholders were selected, the diversity of stakeholders engaged and the mechanisms adopted for learning (i.e., forms of participation). Stakeholder diversity was classified as the breadth and depth of stakeholders. Breadth as used in this study implies the number of stakeholders engaged while depth refers to the different stakeholders from different institutions and levels that were engaged in the identified participatory and social learning studies.

On the forms of participation, White (1996) reports diverse participation forms, such as nominal, instrumental, representative, and transformative participation. Johnson et al. (2004) also report conventional, consultative, collaborative, collegial and farmer experimentation, which are further classified into two broad categories, i.e., functional or empowering participation. We used functional or empowering participation in identifying the forms of participation. Functional participation seeks to engage stakeholders in order to improve research goals and enhance the associated results from the research while empowering participation aims to strengthen the individual and collective capacities to innovate and ‘engages participants through training for skills acquisition to understand and implement or experiment a particular technology and management practices’ (Johnson et al., 2004, p. 190). Empowering participation places stakeholders at the center of the research and the learning process, and recognizes the need to enhance their capabilities, thereby improving the outcomes from participatory and social learning.

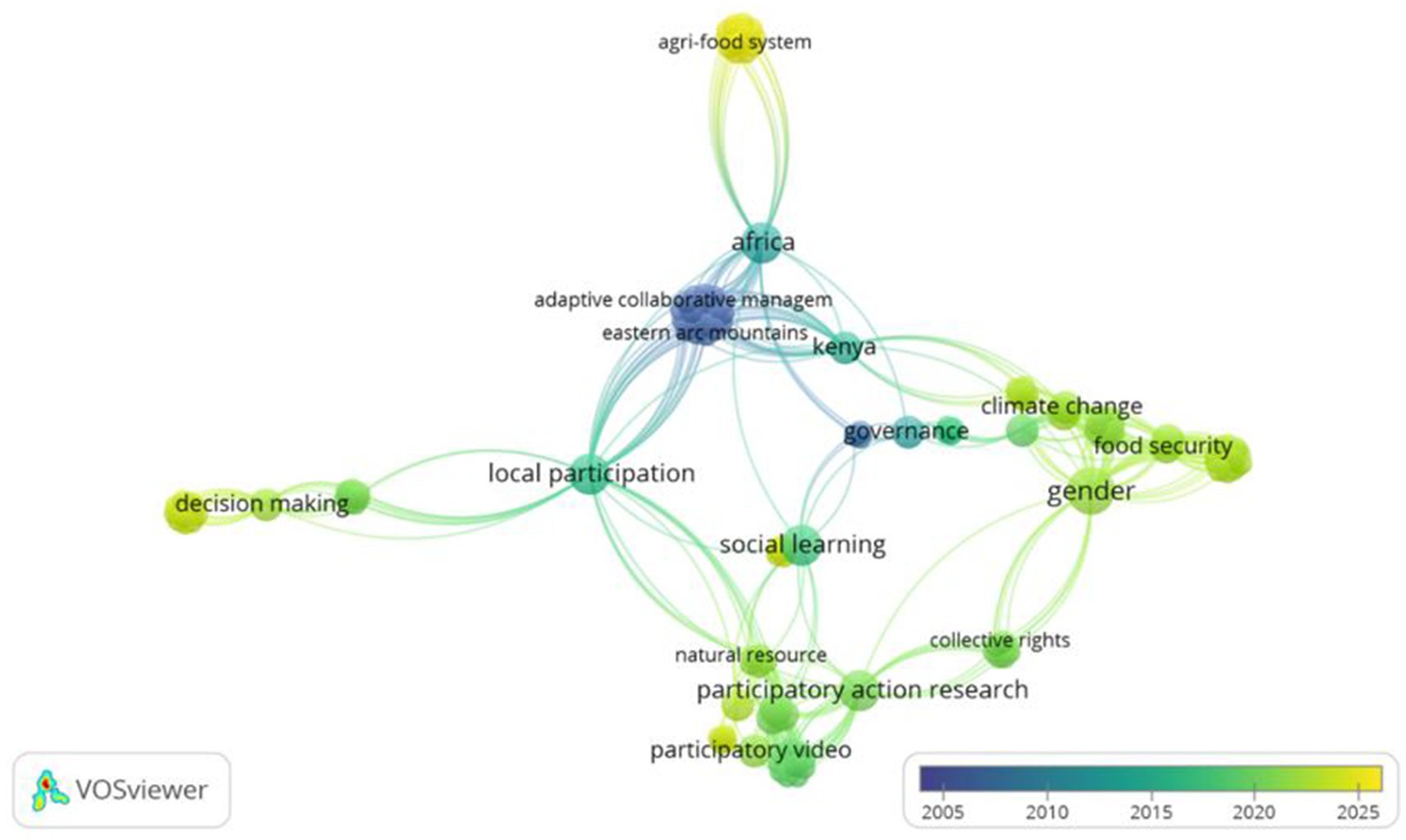

We complemented the analysis of the stakeholder engagement approaches by performing keywords analysis using VOSviewer to explore the common approaches reported in the 14 studies and how they are linked. Co-occurrence of keywords analysis was performed using the full counting method in VOSviewer. This analysis helped us to know whether the approaches identified in the studies supported gender integration or not. Since its development by van Eck and Waltman (2010), VOSviewer has become a frequently used tool in bibliometric studies (Amofa et al., 2023; van Eck and Waltman, 2023). While simple and easy to use, VOSviewer is recognized as a robust and comprehensive computer program capable of exploring networks, mapping and visualizing patterns in bibliometric records. VOSviewer was calibrated to ensure maximization of its text-mining capabilities.

We analyzed research question 4 by manually scanning through and closely reading each of the 14 records to identify themes that reflected issues of gender and inclusion. To enhance reliability, the third author independently verified a random subset of the themes identified in the 14 studies, and discrepancies were addressed through discussions. The themes include women, men and youth voices, power and power relations, rights, gender roles, decision-making, and access to resources. We explored the four forms of power highlighted in the 14 studies. We also identified and synthesized the outcomes reported in the 14 studies.

4 Results

4.1 Summary and trajectory of social learning and participatory research that integrate gender

Supplementary Table 2 provides detailed overview of the 14 studies used in the analysis. A summary of the 14 studies showed that the earliest study among the identified records was published in 2007. Afterwards, 1 study each was published in 2008, 2016, 2017, 2019, and 2023. Two studies each were also published in 2021, 2022 and 2024. The identified records covered diverse issues on agriculture and land management, including sustainable water and agrifood systems (1), forest resource management (4), climate smart agriculture and rural innovation (3), adaptive capacity (4), and communal land governance and conservation (2). Country-wise, the studies were conducted in Ghana (5), Tanzania (2), Kenya (2), Ethiopia (1), and Cameroon (1). Some of the studies covered multiple countries or regions: one in East and West Africa (Mali, Guinea, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania), one in Kenya and Tanzania, and one in Zambia and Uganda.

The results of the trend analysis of participatory and social learning research are presented in Figure 2. We observe that participatory research has evolved since the 1970, with a modest and fluctuating increase between 2005 and 2009 and again after 2015. Juxtaposing this trend with global landmarks, we note that global landmarks focusing on gender, particularly the Women in Development and the Beijing Conference, did not significantly influence the practice of participatory research in Africa. However, participatory research in Africa increased following the MDGs and the SDGs. Specific to gender-integrated social learning and participatory studies, the results show that it was until 2007 that gender begun to be integrated into participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management but this declined from 2009 to 2016. Currently, gender-integrated participatory and social learning studies are gaining traction after the 2015 SDGs but declined in 2019 possibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the number of gender-integrated participatory and social learning studies is low compared to the growth observed generally in participatory research.

Figure 2. Trends of participatory and social learning studies that integrate gender and juxtaposed with global landmarks for gender and development.

4.2 Contextual issues that necessitate the need for gender and social inclusion in participatory and social learning

Manual assessment of the 14 documents provided in-depth insights into the context of the projects’ communities, which might have motivated gender inclusion (see the supplementary Table 2). All the studies highlight project communities’ climate change vulnerability. Subsistence and rain fed agriculture being the dominant livelihood activities of both men and women in the studies’ settings is threatened by erratic rainfall, floods, droughts and rising temperature, frequently increasing smallholder agriculture exposure to climate change, and severely impacting crop and livestock survival, yields, food security and income. Climate change impacts on agriculture further worsen poverty, which is highly differentiated within and across communities and gender. This reveals the differential power and agency of different gender groups to respond to climate change (Garcia et al., 2021).

Women’s agricultural roles and their limited access to land and other resources were highlighted within the studies’ contexts. The studies note that while women’s agricultural and natural resources management roles are crucial for households and community development, they are often overlooked, as men are culturally regarded as households’ breadwinners. Women are also neglected in decision-making due to prevailing cultural and patriarchal norms that perpetuate gender discrimination. For instance, Farnworth et al. (2023) demonstrate how culture and stigmatization are deployed to stifle women’s mobility and response to climate challenges in rural Tanzania. The studies also highlighted women’s limited adoption of agricultural innovations (Farnworth et al., 2023; Kwapong et al., 2024), customary land rights (Lemke and Claeys, 2020), threats to women-specific activities, such as African Locust Bean processing in northern Ghana (Lelea et al., 2022) or milk processing among pastoralist women in Ethiopia (Mulema et al., 2020), and the existing inequality in education among marginalized women in rural communities in Kenya (Walker et al., 2022). These contextual issues reveal the complex nature of challenges faced in the studies’ settings, highlighting the need for social inclusion and gender sensitive approaches to these challenges.

4.3 Stakeholder selection and engagement approaches that promote integrating gender in participatory and social learning

The majority of the 14 studies (76%) selected their participants through the support of local partners and community leaders (see stakeholders’ selection approaches in Supplementary Table 2). This included village heads, opinion leaders, selected local coordinators, local project coordinators and extension agents. Engaging local actors in stakeholder selection enhanced the inclusion of diverse individuals in the learning process. For instance, in Ghana, the assistance of local actors allowed the inclusion of 57% males and 43% females from the project communities (Kwapong et al., 2024), while enabling Farnworth et al. (2023) to also engage 8 couples and 4 female household heads drawn from their project communities in Tanzania. With the help of village heads, Kalibo and Medley (2007) selected 25 participants (68% women and 32% men) in Makwasinyi community while 24 participants comprising of 75% women and 25% men were selected from Jora community in Kenya. For the remaining studies (24%), participants were selected directly by the research team through invitations (two studies) or inviting and interviewing participants (one study) (see stakeholders’ selection approaches in Supplementary Table 2). While 50% of the studies (see study number 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 13 and 14 under stakeholders’ diversity in Supplementary Table 2) included only members of the communities, such as women and men farmers, women groups and community leaders, the remaining 50% engaged stakeholders beyond the project communities, including government officials, extension agents, scientists, civil society organizations and the private sector. It must be cautioned that these approaches that facilitate gender and social inclusion in participatory and social learning do not mean that women were automatically engaged in decision-making or exercised power.

Multiple stakeholder engagement approaches were adopted by the reviewed studies. Some of these include workshops (e.g., modelling, future scenario, co-leaning workshops), field and community visits, participatory video proposal and screening, participatory adaptation scenario and mapping activities, participatory resource mapping, community conversations and discussions, group sessions and topic- or issue-based meetings. Others include training, auto-appraisal, hands-on and role playing, working in groups, and game-based (scenario) activities. Workshop is the most commonly used engagement approach as mentioned by 64% of the studies, although all the studies combined two or more approaches (see forms of engagement in Supplementary Table 2). About 57% of the engagement approaches can be classified as empowering as they involved skills-based activities as opposed to 43% functional approaches that helped to better frame the problems in the participants’ contexts (see forms of engagement in Supplementary Table 2). Skill-based approaches include community resource mapping exercises, future visioning and visualization, community problem-trees, video production, participatory modelling, and role-playing. These allowed the participants to gain hands-on skills as they framed the problems and co-developed solutions in their contexts. Activities, such as brainstorming, discussions, community and field visits are functional that also helped in framing the problems.

The keywords identified in the VOSviewer analysis also offered additional insights into the commonly used approaches and contextual issues that necessitated the need for integrating gender in participatory and social learning studies and their interconnections (Figure 3). The figure shows the evolution in keywords from those that were used from the early 2000s (i.e., forestry, forest resources, community resource management, community conservation, participatory rural appraisal etc.) to more recent post 2015 (SDGs) keywords including sustainable development, system thinking, participatory modelling, system dynamic modelling, agri-food systems and decision-support systems. This demonstrates the emergence of new approaches to addressing complex challenges through participatory research.

4.4 Gender and social inclusion in participatory and social learning studies

The studies discussed and/or addressed several gender and intersectional issues (Supplementary Table 2). The studies worked with the gender binaries - male/female or men/women. About 57% of the studies looked at gender roles and division of labor among women and men at the farm and household levels through discussions and dialogues with both male and female participants or gender-specific subgroups (see gender and social inclusion in Supplementary Table 2). For instance, through community meetings and discussions, it was revealed that women performed more household chores including harvesting water and firewood while men’s roles involved clearing lands and fertilizer application (Kotir et al., 2024). Similarly, livestock mobility and healthcare are the domains of men as opposed to processing and preserving milk products, which are women’s roles (Lemke and Claeys, 2020; Walker et al., 2022). Discussions on the gender roles of men and women generated tensions given the differential perspectives of men and women. For instance, women vehemently opposed the notion that men are the sole providers of household incomes as the incomes generated from women’s livelihood activities contribute to household management (Garcia et al., 2021). Single mothers, widows and young women in particular objected to the views of men. As heads of their households, these participants play the same role as men.

Power relations and power dynamics featured prominently in all the identified studies. Issues of power were manifested and discussed in diverse forms including households and agricultural decision-making, access and control of resources, adoption and dissemination of innovation, norms and hierarchy. Except one study that looked at the different power modalities that were at play among the social learning participants (Richardson-Ngwenya et al., 2019), all the remaining studies explored power dynamics from both the household and community levels. In many workshops and dialogues, household and agricultural decisions, such as what crop to plant, where and when to plant, which innovations to adopt, and how income from agriculture is used, were reported to be exercised men. Thus, men exercise ‘power over’ and less ‘power with’ in household decision-making even if women play critical role in households’ agricultural activities. For instance, women in their participatory videos and community meetings highlighted they have to inform their husbands before adopting innovations (Kwapong et al., 2024).

‘Power over’ the control of resources was tensely discussed as they are traditionally the domains of men. It was frequently reported that men control resources, such as land, and they are also often the targets of interventions and innovations, sidelining many women, particularly singles, divorced women and widows. Men’s exercise of ‘power over’ resources is not limited to the resources of the households but also community resources, such as forest and irrigation. Culture and local legislation could stiffen women, particularly widows, control of land and access to irrigation as observed in rural Tanzania (Smucker and Wangui, 2016). Local land legislation makes it possible for lands to be taken away from members of the communities and given to others. However, compared to women who often lose their lands, men exploit their social networks in the communities and with other bodies to minimize loss and maintain control over lands.

Men’s exercise of ‘power over’ resources are also manifested in resources that are traditionally ascribed to women. For instance, women traditionally engage in shea collection and processing, and firewood harvesting but the rising demand for shea products or fuelwood has intensified men’s penetration into shea and charcoal production, leading to competition that disadvantage women (Cronkleton et al., 2021). This is consistent with Lelea et al. (2022) who also observed a similar trend where the installation of the ‘dawadawa’ (African Locust Bean) Chief threatens women’s traditional access and use of ‘dawadawa’. For women in northern Ghana, their limited ownership and control of land given the patriarchal inheritance systems and the allocation of land by local, male chiefs or male family members increases their vulnerability to access ‘dawadawa’. This demonstrates how traditional land governance structures and the associated land tenure systems proportionally disadvantage women’s access to resources.

From an intersectional lens, women exercise different forms of power based on their educational status (Walker et al., 2022). Educated pastoralist women exhibited greater ‘power over’, ‘power to’ and ‘power with’ in making decisions to respond to drought compared to uneducated women, as they have better access to information, enabling them to make informed adaptation decisions. This allows them to respond better to drought (e.g., know when to restock or sell their livestock) compared to their counterparts. Similarly, their educational status allows them to access essential social networks, enabling them to collaborate and exercise ‘power with’ others. Cooperation among women led to the exercise of ‘power to’ and ‘power with’ as both men and women collaborated together to identify and develop innovations (Richardson-Ngwenya et al., 2019). Specific to ‘power to’, participants identified innovations they deemed suitable to their contexts through exercising ‘power with’ other members of their groups. Making decision related to what is suitable and essential to participants demonstrated their ‘power to’ while working with others to find solutions symbolized ‘power with’. In Cameroon, while both men and women exercise power in the management of forest resources, men inherently dominate essential decision-making bodies and committees, and hence, used ‘power with’ to control more resources, and women (Brown et al., 2008). Women’s limited power in forest resource management stems from their burden of work, such as child care and household chores, which often hinder their effective participation. Similar manifestation of power is also elaborated in water resource management in Zambia and Uganda (Ratner et al., 2017).

4.5 Outcomes from participatory and social learning studies that integrate gender and social inclusion

From the studies’ result sections, several outcomes are reported (Supplementary Table 2). While the outcomes are broad, they can be categorized into those related to the research process, impacts on participants’ capacities, and changes occurring in the wider communities. Regarding the impact on the research process, the studies focused on how participatory and social learning approaches contributed to improved framing of the research problems in the studies’ contexts, particularly from a gendered perspective. The engagement of both men and women through participatory and social learning approaches offered the opportunity to understand the complexity and diversity of the research problems. For instance, landscape mapping exercises involving men and women helped to identify and understand the resources needs and constraints of women and men (Kalibo and Medley, 2007). Women mapped their landscape by including forest and trees sites as important parts of their landscape given their roles in the collection of firewood as an essential resource. However, they also included wild animals in their landscape as wild animals pose a danger to them and prevent them from collecting firewood from tree sites. In the case of men, essential elements in their landscape included black cotton soil, which is essential for farming, as well as trees and grasses areas that served building purposes. The insights gained from framing the problems significantly contributed to improving researchers’ knowledge and shaped the research process. For instance, Kotir et al. (2024) indicated that they gained in-depth knowledge of the deep-rooted cultural beliefs and practices among their participants, enabling them to effectively engage their participants in their cultural context.

All the studies highlighted improvement in the capacities of research participants. The participants improved their knowledge of the diversity of problems men and women face in their communities. Additionally, research participants reported improved confidence in public speaking, established and built new networks, and acquired skills in using technologies, such as camera or video editing, as well as facilitation skills (Cronkleton et al., 2021). Women highlighted that their engagement in the research boosted their confidence to speak in the presence of community chiefs for the first time. The adoption of participatory and social learning approaches with men and women contributed to collaboration and trust building.

Beyond the impacts on the research participants, the studies highlight that engaging both men and women in participatory and social learning offer enormous benefits at the household and community levels, such as improved collaboration, collective decision-making, shifting gender relations, norms and practices, and changes in perceptions (Farnworth et al. 2023). Improved collective decision-making among spouses at the household enabled them to collaborate in identifying and addressing their challenges. For instance, husbands who previously made decisions related to the sales of crops now consult their wives and some even allow their wives to keep and manage the money after sales. Collaboration at the households also enhanced shared rights among spouses, as men and their children performed household chores, such as cooking, washing and collecting firewood, which was previously not done. Roles, such as tilling land, sales of livestock and treating sick animals, are traditionally performed by men while women also engage in cooking, cleaning barns, fetching water and milking cow. However, participatory and social learning activities altered gendered roles, as men performed women’s roles, such as cooking (e.g., baking bread and preparing sauce), milking cows while wives also ploughed with oxen and marketed livestock. This contributed to burden sharing, minimizing women’s burden of work.

Changes in perceptions among men and women served as the foundation for shifting gender relations and roles at the household and community levels. By allowing women groups report and facilitate community meetings, there was a general shift in perception that women can also perform community activities that are traditionally associated with men. Women’s ability to perform men’s roles was associated with improved knowledge in how to manage and handle animal source food (Farnworth et al., 2023). Similarly, providing the dialogue platforms to discuss gender roles allowed women to raise their voices and challenge gender norms, which put a spotlight on women’s undervalued contributions. This understanding influenced the agency to work collectively at the household, thereby shifting perceptions that men are the sole household decision-makers. The changes in perceptions also minimized stigmatization, such as men being considered womanish for helping their wives or women considered prostitutes for relying on mobility as a form of response to climate and environmental challenges.

The identification and adoption of innovations were also reported among the identified studies (Farnworth et al., 2023; Kotir et al., 2024). Engaging men and women positioned them to identify tree planting and income generating activities as more suitable innovations for improving women’s livelihoods while agricultural expansion through fertilizer application and mechanization were more preferred among men. Similarly, participatory and social learning improved access to resources among the vulnerable (Farnworth et al., 2023). Landless youth accessed alternative livelihoods including the construction of fish ponds to engage in fish farming. To improve efficiency, landless youth pooled resources together and integrated women in their alternative livelihoods’ activities. The authors note that integrating women in fish farming improved productivity and income, as they brought their indigenous knowledge, such as feeding fish with household leftover and maize flour, which significantly reduced the cost of production. Introducing a quota system for management committees and minimizing women’s burden through the introduction of childcare arrangement increased women’s participation in natural resource management (Ratner et al., 2017).

5 Discussion

The results from the study reveal that while participatory studies have increased in recent times, relatively few studies integrate gender, which is consistent with Egunyu and Reed (2015) that many participatory studies are gender blind. The context under which participatory studies are conducted and the rationale of participatory studies to address complex socioecological challenges necessitate the need to be inclusive and sensitive to gendered issues. Our study shows that complex challenges, such as climate change, cultural norms, natural resource management, vulnerability, inequality in access to resources, among others, in agrarian communities are gendered and complex. Hence, addressing these challenges requires paying attention to issues of gender and inequality (Sumberg and Thuijsman, 2024). Participatory approaches including video proposals, system modelling, mapping exercises, dialogue platforms or workshops have shown to be appropriate in addressing such complex societal challenges as they offer the opportunity for knowledge exchange, deliberation and reflection among different stakeholders and gender groups. Similarly, they offer the opportunity to challenge gender norms that perpetually disadvantage women or stigmatize men from collaborating with women. Thus, participatory and social learning approaches that are inclusive and sensitive can address the limitations of traditional research that often favours men or employs questionnaires and interviews which do not provide the space to address unique positions and challenges of certain groups while challenging gender norms through reflection (Twyman et al., 2015; Asare-Nuamah et al., 2025).

We observed that many of the studies selected participants through local partners and community leaders. Local actors have in-depth knowledge of their context, vulnerable groups, gender norms and values and can contribute significantly to selecting appropriate stakeholders. However, local actors must be conscientized to consider gender and other marginalized groups in the selection process to avoid the exclusion of other relevant actors, resulting in selection bias (Johnson et al., 2004). For instance, local leaders can selectively engage well-integrated stakeholders in the system and provide affirmations that align with their preferences, regardless of their veracity, thereby biasing the information. Another challenge that may arise when local actors select stakeholders is the inclusion of participants with limited capacities to participate effectively in dialogues, deliberations and reflection. Studies note that requisite capacities are essential for effective engagement (Lotz-Sisitka and Burt, 2006; Kilvington, 2010; Lamboll et al., 2021). However, this can indirectly exclude women and marginalized groups who are often not exposed to participatory engagement. Richardson-Ngwenya et al.'s (2018) approach of inviting and interviewing local stakeholders prior to their inclusion in their study contributed to addressing selection bias as it helps to assess the engagement capacities of the actors. We observed from the studies that a careful and targeted selection of research stakeholders leads to a much larger inclusion of women than otherwise.

Addressing gender issues, such as inequality in access and control of resources, traditional norms and practices that perpetually disadvantage women and marginalized groups, is essential for tackling complex challenges. As these issues are deeply rooted in hierarchies, it is crucial to be sensitive to these issues, address the underlining power relations and power dynamics to address gender inequality in participatory settings (Tschakert et al., 2023). At both household and community levels, men exercise power over women and resources - highlighting ‘power over’ as visible power in gender relations (Tschakert et al., 2023; Dev et al., 2024), which severely hinders women’s participation in decision-making roles or resources access and control. While power to, power with and power within are imperative in households and community development, these forms of power are often invisible in gender relations (Kabeer, 2020). Through participatory and social learning approaches, these four forms of power can be reinforced or addressed as they are discussed and contested among men and women. Thus, participatory and social learning approaches that are socially inclusive and gender sensitive/transformative allow women and marginalized groups to often contest and challenge the notion of power allocated to men and the associated discrimination against them. While gender sensitive/responsive approaches recognize the peculiar challenges of men and women and encourage their participation in collective action, gender transformative approaches are highly essential as they challenge and transform the structural and systemic causes of gender-based inequalities that are inherent in discriminatory and biased social institutions (Lopez et al., 2023). Thus, the latter enables women to assert their rights and contributions in households’ and community decision-making or resource management. The contestation of power and rights among men and women in participatory settings helps to change the rules governing society and gender relations.

Integrating gender in participatory and social learning research offers benefits and outcomes far beyond traditional research approaches and participatory studies that are gender blind. While researchers learn from the context and improve the research goals, participants enhance their capacities through the acquisition of communication and facilitation skills, improved confidence and networks as well as improvement in knowledge and emerging practices. These capacities are essential in exercising power and agency (Bikketi et al., 2016; Dev et al., 2024) and enable women to make decisions for themselves, e.g., entering into cooperation, sharecropping or pooling resources with others. The gained capacities allow households and communities to make more informed decision to respond to climate and environmental challenges and adopt innovations. Participatory and social learning approaches that integrate gender can contribute to shifting power dynamics, norms, gender relations and perceptions (Farnworth et al., 2023). Beyond participatory and social learning approaches, studies including Asare-Nuamah et al. (2024) note that increasing access to essential resources for women can position them in asserting their roles as change agents in their households and communities, thereby altering their power and gender relations.

Notwithstanding the benefits associated with participatory and social learning approaches, they are not without challenges when applying the approaches in the real-world. The insatiable and changing needs and preferences of humans and gender groups can stiffen progress toward collective development (Kotir et al., 2024). This affects the sustainability of collectively developed innovations over time. To meet the changing preferences of diverse social groups in participatory settings and enhance context-specific innovations, participatory and social learning researchers, policymakers and practitioners must adapt their approach to the context. Adapting participatory and social learning approaches to local contexts requires more resources, which is often lacking, and it is also time-consuming. Also, funders expect to see research results and impact of their investments within a stipulated time, thereby hindering the potential to adapt to local context and create sustainable change. Many studies have also reported how the existing power imbalances and socio-cultural contexts in agricultural settings in Africa substantially influence participatory processes (Farnworth et al., 2023), creating lock-in effects and rendering them ineffective and unsustainable. Compliance and adherence to culturally rooted norms, values and rules governing social relations hinder the potential of the marginalized and underrepresented groups to embrace change (Kwapong et al., 2024). Thus, change emanating from participatory and social learning processes can further worsen social tension and conflict between power holders (gatekeepers) and the marginalized and underrepresented groups in society. Additionally, applying participatory and social learning approach can be initially confusing and challenging for rural participants, which can lead to withdrawal among participants. For instance, Farnworth et al. (2023) report that exposing the Gender Action Learning Systems (GALS) tools to participants in rural Tanzania received initial negative reactions, as many of the local actors perceived the approach to be difficult and confusing. Providing detailed conceptual and practical understanding of a particular approach or tool, and adopting iterative and repetitive processes in participatory and social learning can contribute to minimize initial negative feedback, particularly in communities that are not exposed to participatory processes. Again, the possibility of tension and conflict among participants in participatory and social learning has been highlighted, which can be addressed through diverse conflict mediation and resolution approaches, such as open dialogue and active listening (Kotir et al., 2024; McNaught, 2024; McNaught et al., 2024).

The findings from this review have broader implications for addressing complex socio-ecological challenges by researchers, policymakers and practitioners including civil society organizations, as the world seeks to promote sustainable development and leave no one behind. From our findings, we argue that it is insufficient for researchers, policymakers and practitioners to adopt just participatory approaches in research and development if gender and social inclusion are not rigorously taken into account in the learning process. As observed in northern Ghana, Lelea et al. (2022) show how women groups used participatory mapping and visualization to negotiate innovative land-use arrangements with traditional leadership, thus securing women’s rights to harvest ‘dawadawa’ on communal lands. Similarly, Kalibo and Medley (2007) demonstrate how participatory landscape mapping involving men and women revealed gendered access and constraints to natural resources, improving collective resource management among men and women at both household and communal levels in rural Kenya. Thus, socially inclusive and gender sensitive approaches are crucial to ensure that innovations and development meet the priorities, preferences and unique needs of different categories of stakeholders and beneficiaries. Explicitly, policy-makers, researchers and practitioners must be conscious to integrate social inclusion and gender sensitive approaches in participatory and social learning when dealing with complex societal challenges. This offers the advantage of not only understanding the peculiar contexts of underrepresented, vulnerable, disadvantaged and marginalized groups but also co-develop solutions that meet their unique needs and overcome their constraints, thereby leaving no one behind and promoting sustainable development. Any form of exclusion can result in insensitive innovations and development, which can perpetuate inequality, particularly against marginalized groups.

We identify critical gaps in the literature that requires attention. First, there is limited application of intersectinoality in the seleced studies, hightlighting a methodological and practical gap in participatory and social learning approaches. This must be addressed to strengthen the core intent of the approaches in promoting sustainable and inclusive development. Applying intersectionality in participatory and social learning approaches to address complex challenges is highly recommended (Lopez et al., 2023) as it has the added advantage of offering even more targeted outcomes and solutions in vulnerable contexts. This can be achieved following intersectional approaches (e.g., GenderUp) that enable the integration of intersectionality and diversity in participatory studies in complex environments (McGuire et al., 2024b; McGuire et al., 2024a). Second, while the studies prioritize highlighting positive outcomes, their limitations are often not reported. For instance, the studies are silent on the challenges and barriers that affect gender-inclusive participatory and social learning approaches. It is imperative for gender-inclusive participatory and social learning studies to highlight the challenges and barriers encountered to enable future studies to explore mechanisms of dealing with the challenges. Also, it is crucial for studies to demonstrate how the observed changes and impacts in households and communities can be sustained without creating further burden and unintended consequences (i.e., tension, conflict, competition etc.) for beneficiaries. This is important as ad hoc and unsustained changes can have negative consequences that may further worsen prevailing inequalities at the household and community levels. Third, the approaches to monitoring and evaluating outcomes from participatory and social learning are not concretely highlighted in the majority of the studies. As noted by Christinck and Kaufmann (2017), learning occurs through continuous loop that involves interaction between action and reflection. Hence, participatory monitoring and evaluation approaches are essential, as they enable participants to self-evaluate their actions and reflections, resulting in the development and improvement of new knowledge and practices among local actors. Fourth, the review shows that the existing studies are largely skewed towards qualitative approaches, neglecting the application of quantitative approaches in gender-inclusive participatory and social learning studies. This makes it difficult in performing meta-analysis on the subject matter.

While this study offers immense insights into gender and participatory research there are limitation associated with the approaches we adopted in the study. We recognized that relying only on Scopus and Web of Science databases might have excluded some relevant records on the subject matter, which is a limitation of this study. This is because many Africa-based journals are not indexed in Scopus and Web of Science. Similarly, the databases used are often skewed towards the English language and hence resulted in the exclusion of other relevant non-English studies, such as those in French or Portuguese. Also, the keywords used in the literature search might have missed out some relevant materials indexed in Scopus and Web of Science. Again, given the approach adopted, our systematic review is unable to determine which participatory and social learning approaches are effective in empowering women and men in real world scenarios. This can be addressed if systematic review is complemented with further interviews of researchers and local participants engaged in the identified studies, which we could not do in this study. Thus, our approach limits our ability to concretely assess sense of empowerment through a systematic review. These limitations led to the exclusion of relevant insights from existing studies not indexed in these databases or not in the English language. Implicitly, the results and interpretations from this study might have led to an incomplete representation of gender-inclusive participatory studies conducted in Africa. Nonetheless, the insights from this systematic review contributes to the literature and practice to shed more light on the inclusion of gender in participatory and social learning research.

6 Conclusion

We conducted a systematic review of how participatory and social learning research in agriculture and land management in Africa integrated gender. The findings reveal that while the adoption of participatory research has increased, especially after the 2015 SDGs, gender remains elusive in many participatory studies. Yet, the contextual challenges that participatory studies seek to address, such as climate vulnerability, adaptive capacity, agri-food systems, innovation adoption, access and control of resources etc., are complex and gendered, and requires the active participation of diverse voices. Gender-responsive, socially inclusive participatory studies that provide the space for dialogues, deliberations and reflections are important to addressing gender issues, as they enable men and women from different social groups to frame their contextual problems from their perspectives and lived experiences, shaping how the challenges must be addressed collaboratively.

Participatory studies should be socially inclusive and gender sensitive, and pay attention to power dynamics that govern society, determine gender relations, and influence access and control over resources. This can contribute to addressing the peculiar challenges of diverse stakeholders. From the systematic review, it became evident that men exercise power over resources and women, undermining the importance of other forms of power, such as power to, power with and power within. Future studies should address these power modalities when addressing challenges in the agricultural sector, as women’s inability to exercise power at the households and community levels increases their vulnerability. Participatory approaches involving both men and women can then lead to a shift in norms, values, perceptions and behavior at the household and community levels, if they are both socially inclusive and gender sensitive. We recommend that participatory and social learning studies must go beyond mere recognition of the gendered challenges and constraints of women and men by ensuring that efforts are made to address and alter existing power relations. Given the limited application of intersectionality in participatory and social learning research, future research must focus more on intersectionality in co-developing gender-responsive, gender-sensitive and gender-transformative innovations and solutions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PA-N: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. TB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. CA: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study forms part of the INTERFACES project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) under the funding line research for sustainability (FONA) with the research grant number FKZ 01LL2101A. This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Bonn.

Acknowledgments

An initial version of the abstract was submitted and presented at the 2024 Tropentag Conference in Vienna, Austria.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1664042.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1628825/full#supplementary-material

References

Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., and Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Dev. 52, 71–91. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007

Amofa, B., Oke, A., and Morrison, Z. (2023). Mapping the trends of sustainable supply chain management research: a bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed articles. Front. Sustain. 4:1129046. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1129046

Asare-Nuamah, P. (2023). Trade-offs and synergies of climate adaptation strategies within the agriculture value chain in Africa. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Manag. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.26796/jenrm.v9i1.213

Asare-Nuamah, P., Anaafo, D., Akurugu, C. A., and Beuchelt, T. (2025). Integrating gender in social learning approaches for agriculture and land management research and implementation projects: Insights and reflections from sub-Sahara Africa. Bonn, Germany. Available online at: https://bit.ly/ZEF-WP-239 (Accessed May 3, 2025).

Asare-Nuamah, P., Sedegah, D. D., Anane-Aboagye, M., Asiedu, E. A., and Akolaa, R. A. (2024). Enhancing rural Ghanaian women’s economic empowerment: the cassava dough enterprise. Dev. Pract. 34, 97–114. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2023.2272058

Barreteau, O., Bots, P. W. G., and Daniell, K. A. (2010). A framework for clarifying “participation” in participatory research to prevent its rejection for the wrong reasons. Ecol. Soc. 15:24. doi: 10.5751/es-03186-150201

Bentley Brymer, A. L., Wulfhorst, J. D., and Brunson, M. W. (2018). Analyzing stakeholders’ workshop dialogue for evidence of social learning. Ecol. Soc. 23, 42–52. doi: 10.5751/ES-09959-230142

Beuchelt, T. D., and Badstue, L. (2013). Gender, nutrition- and climate-smart food production: opportunities and trade-offs. Food Secur. 5, 709–721. doi: 10.1007/s12571-013-0290-8

Beuchelt, T. D., and Nassl, M. (2019). Applying a sustainable development lens to global biomass potentials. Sustain. For. 11:5078. doi: 10.3390/su11185078

Bikketi, E., Ifejika Speranza, C., Bieri, S., Haller, T., and Wiesmann, U. (2016). Gendered division of labour and feminisation of responsibilities in Kenya; implications for development interventions. Gend. Place Cult. 23, 1432–1449. doi: 10.1080/0966369x.2016.1204996

Britwum, A. O. (2022). Gendered tensions in rural livelihoods and development interventions. Fem. Africa 3, 1–13.

Britwum, A. O., Tsikata, D., Akorsu, A., and Aberese, M. (2014). Gender and land tenure in Ghana: A synthesis of the literature. Accra, Ghana: Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University of Ghana.

Brown, H. C. P., Buck, L. E., and Lassoie, J. P. (2008). Governance and social learning in the management of non-wood Forest products in community forests in Cameroon. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 7, 256–275. doi: 10.1504/IJARGE.2008.018329

Castellini, G., Romanò, S., Merlino, V. M., Barbera, F., Costamagna, C., Brun, F., et al. (2025). Determinants of consumer and farmer acceptance of new production technologies: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1557974. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1557974

CGIAR (2024). Why gender matters in collective action for agricultural innovation. Kampala. Available online at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/97418208-78b3-47ad-81a2-32d68e63f65c/content (Accessed April 10, 2025).

Chambers, R. (1994). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): analysis of experience. World Dev. 22, 1253–1268. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(94)90003-5

Chambers, R., Pacey, A., and Thrupp, L. A. (1989). Farmer first: Farmer innovation and agricultural research. London: Practical Action.

Christinck, A., and Kaufmann, B. (2017). “Facilitating change: methodologies for collaborative learning with stakeholders” in Transdisciplinary research and sustainability: Collaboration, innovation and transformation. ed. M. Padmanabhan (London, UK: Routledge), 20.

Cornish, H., Walls, H., Ndirangu, R., Ogbureke, N., Bah, O. M., Tom-Kargbo, J. F., et al. (2021). Women’s economic empowerment and health related decision-making in rural Sierra Leone. Cult. Health Sex. 23, 19–36. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1683229

Cornwall, A. (2003). Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on gender and participatory development. World Dev. 31, 1325–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00086-X

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: what works? J. Int. Dev. 28, 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

Cronkleton, P., Evans, K., Addoah, T., Dumont, E. S., Zida, M., and Djoudi, H. (2021). Using participatory approaches to enhance women’s engagement in natural resource management in northern Ghana. Sustain. For. 13:7072. doi: 10.3390/su13137072

Darnhofer, I., Gibbon, D., and Dedieu, B. (2012). Farming systems research into the 21st century: the new dynamic. Farming Syst. Res. 2012, 1–490. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4503-2

Dev, D. S., van de Fliert, E., and McNamara, K. (2024). Who plans for women? Representation of power in planning for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Asia Pac. Viewp. 65, 365–379. doi: 10.1111/apv.12422

Egunyu, F., and Reed, M. G. (2015). Social learning by whom? Assessing gendered opportunities for participation and social learning in collaborative forest governance. Ecol. Soc. 20:444. doi: 10.5751/ES-08126-200444

Elias, M., Jalonen, R., Fernandez, M., and Grosse, A. (2017). Gender-responsive participatory research for social learning and sustainable forest management. For. Trees Livelihoods 26, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1247753

Evans, K., Monterroso, I., Ombogoh, D., Liswanti, N., Tamara, A., Mariño, H., et al. (2021). Getting it right, a guide to improve inclusion in multi-stakeholder forums. Bogor, Indonesia. Available online at: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/7973/ (Accessed April 11, 2025).

Farnworth, C. R., Fischer, G., Chinyophiro, A., Swai, E., Said, Z., Rugalabam, J., et al. (2022). Gender-transformative decision-making on agricultural technologies: Participatory tools. Ibadan, Nigeria: International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA).

Farnworth, C. R., Fischer, G., Rugalabam, J., and Islahi, Z. S. (2023). Gender-transformative agricultural experimentation and decision-making: piloting GALS tools in Tanzania. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 101:102836. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102836

Galiè, A., and Farnworth, C. R. (2019). Power through: a new concept in the empowerment discourse. Glob. Food Sec. 21, 13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.07.001

Gammage, S., Kabeer, N., and Rodgers, Y. V. d. M. (2016). Voice and agency: where are we now? Feminist Econ. 22, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1101308

Garcia, A., Tschakert, P., Karikari, N. A., Mariwah, S., and Bosompem, M. (2021). Emancipatory spaces: opportunities for (re)negotiating gendered subjectivities and enhancing adaptive capacities. Geoforum 119, 190–205. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.09.018

Gidley, J. M., Hampson, G. P., Wheeler, L., and Bereded-Samuel, E. (2010). Social inclusion: context, theory and practice. Australas. J. Univ. Engagem. 5, 6–36.

Hegde, N., Elias, M., Lamers, H. A. H., and Hegde, M. (2017). Engaging local communities in social learning for inclusive management of native fruit trees in the Central Western Ghats, India. For. Trees Livelihoods 26, 65–83. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1257398

Huambachano, M., Soto, G. R. N., and Mwampamba, T. H. (2025). Making room for meaningful inclusion of indigenous and local knowledge in global assessments: our experiences in the values assessment of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem. Ecol. Soc. 30:16. doi: 10.5751/ES-15599-300116

Johnson, N. L., Lilja, N., Ashby, J. A., and Garcia, J. A. (2004). The practice of participatory research and gender analysis in natural resource management. Nat. Res. Forum 28, 189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00088.x

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: refections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Change 30, 435–464.

Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: a critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Gend. Dev. 13, 13–24. doi: 10.1080/13552070512331332273

Kabeer, N. (2020). Women’s empowerment and economic development: a feminist critique of storytelling practices in “Randomista” economics. Feminist Econ. 26, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2020.1743338

Kalibo, H. W., and Medley, K. E. (2007). Participatory resource mapping for adaptive collaborative management at Mt. Kasigau, Kenya. Landsc. Urban Plan. 82, 145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.02.005

Karambiri, M., Elias, M., Vinceti, B., and Grosse, A. (2017). Exploring local knowledge and preferences for shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) ethnovarieties in Southwest Burkina Faso through a gender and ethnic lens. For. Trees Livelihoods 26, 13–28. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2016.1236708

Kilvington, M. (2010). Building capacity for social learning in environmental management. Christchurch: Lincoln University.

Kosmowski, F., Alemu, S., Mallia, P., Stevenson, J., and Macours, K. (2020). Shining a brighter light: Comprehensive evidence on adoption and diffusion of CGIAR-related innovations in Ethiopia. Rome. Available online at: https://cas.cgiar.org/spia (Accessed April 8, 2025).

Kotir, J. H., Jagustovic, R., Papachristos, G., Zougmore, R. B., Kessler, A., Reynolds, M., et al. (2024). Field experiences and lessons learned from applying participatory system dynamics modelling to sustainable water and Agri-food systems. J. Clean. Prod. 434:140042. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140042