- University of Gastronomic Sciences, Pollenzo/Bra, Cuneo, Italy

Underutilized crops (UCs) offer significant ecological, nutritional, and socio-cultural benefits, yet remain marginalized in mainstream food systems. This study investigated consumers’ knowledge and attitudes toward a potential label for UCs across three European countries: Italy, Portugal, and Germany. Through a cross-national online survey (n = 3,023), we examined consumers’ familiarity with the UC concept, perceived social, environmental, and economic benefits, trust in a potential UC label, and willingness to buy UC-labeled products. Statistical analyses, including Mann–Whitney U tests, Kruskal–Wallis tests with post-hoc comparisons, and ordinal logistic regression models, revealed that declared knowledge of UCs is associated with significantly higher perceived benefits and stronger purchase intentions. Trust in the UC label emerged as the most significant predictor of willingness to buy, followed by socio-demographic and value-based factors such as education level, ethical concern, and food label engagement. Participants viewed the UC label as more closely aligned with the organic label than with the quality schemes of protected geographical indications and protected designations of origins. These results underscore the potential of a dedicated UC label to raise awareness, enhance consumer trust, and support more biodiverse and resilient food systems. The development of such a label should be accompanied by targeted communication strategies and participatory design processes to reflect the multifaceted value of underutilized crops.

1 Introduction

The global food system is undergoing increasing scrutiny as it fails to address key sustainability and equity challenges, including climate change, environmental degradation, malnutrition, and the erosion of agrobiodiversity (Elouafi, 1979; Jenkins et al., 2023). Agrobiodiversity, defined as the genetic variability within and among plant and animal species used in agriculture, is a cornerstone of resilient, adaptive, and sustainable food system (Jenkins et al., 2023; Khoury et al., 2014). Yet despite its importance, current agricultural production is alarmingly homogenized: just nine species contribute over 66% of global crop production (FAO, 2019), while thousands of locally adapted and potentially valuable plant species are underutilized or neglected in formal markets, research agendas, and policy frameworks.

Within this context, underutilized crops (UCs) - sometimes called orphan, neglected, minor, or traditional crops - refer to species, landraces, or cultivars that are historically cultivated and ecologically adapted but marginalized in modern food systems (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004; Mabhaudhi et al., 2022). UCs encompass a wide array of crop types, including cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and aromatic or medicinal plants. Consequently, products derived from UCs can vary significantly in form and degree of processing: from fresh produce intended for direct consumption (e.g., leafy greens, pulses, or fruits) to processed ingredients and packaged foods such as flours, grain-based products, preserves, or herbal infusions. This diversity implies that a UC label could apply to a broad spectrum of food products across the value chain, highlighting the versatility and wide applicability of these crops within contemporary diets and food systems. UCs often exhibit agronomic traits that align with the principles of agroecology, including resilience to biotic and abiotic stress, adaptation to marginal environments, and cultivation using low-input practices (Jenkins et al., 2023; Mabhaudhi et al., 2022; Bayudan et al., 2024). They are also culturally embedded, nutritionally rich, and linked to diversified and context-specific food traditions (Nicita et al., 2023).

However, their marginalization is rarely due to agronomic inferiority alone. Rather, UCs suffer from systemic neglect stemming from insufficient research, lack of extension services, poor seed systems, underdeveloped value chains, and inadequate market infrastructure (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004). Moreover, the dominance of standardized global food systems, prioritizing yield, shelf-life, and uniformity, has led to the exclusion of diverse local crops that do not fit industrial criteria for processing or exportability (Revoredo-Giha et al., 2022; Mariani et al., 2021).

Moreover, UC-based food systems hold promise not only for sustainability but also for equity and inclusion. In several European regions, these crops are cultivated by smallholders, peasant farmers, or actors engaged in community-based seed systems, and thus represent both an agricultural and social heritage. Therefore, producers need to better communicate the quality attributes of UCs, as this is a category that consumers are currently unfamiliar with and struggle to recognize within the market (Bayudan et al., 2024). Label claims are the tool par excellence used by producers to bridge the information gap, build trust with consumers, and differentiate themselves from other producers (Tonkin et al., 2015). This is particularly true because consumers mostly make purchasing decisions in “mute markets,” where they are not assisted in their choices but are instead informed (and influenced) by labeling and advertising (Tregear and Giraud, 2011). As a consequence, producers have been increasingly taking advantage of the legal tools developed by public regulators, such as geographical indications (Cardoso et al., 2022). At the same time, new logos have been registered as individual, collective, or certification trademarks. In sum, logos on labels can serve both to increase consumer awareness of the quality attributes that characterize UCs and to ensure that UCs are preferred in the competitive market. A well-designed UC label could therefore become a tool not only for market differentiation but also for empowering custodians of agrobiodiversity and enhancing seed and food sovereignty (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004; Nicita et al., 2023).

Beyond their ecological and cultural significance, UCs play a crucial role in enhancing nutrition and promoting human health. Many UCs are rich in micronutrients, dietary fibre, and phytochemicals that contribute to preventing non-communicable diseases and improving overall dietary quality (Mabhaudhi et al., 2022; Bayudan et al., 2024). Their reintroduction into contemporary diets can help combat both micronutrient deficiencies and the overreliance on calorie-dense but nutrient-poor staple crops, which are increasingly associated with diet-related diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions (Petrescu et al., 2020; Bravo et al., 2024). Several studies in the European context have highlighted that consumers are open to exploring unfamiliar crops when these are framed around health benefits and dietary diversification (Bayudan et al., 2024; Petrescu et al., 2020). Importantly, dietary diversification through UCs also aligns with sustainability goals, as it can reduce pressure on overexploited species and promote agricultural landscapes rich in both biodiversity and nutritional outputs (Nicita et al., 2023).

Despite growing interest in food biodiversity, consumers often remain unfamiliar with UCs and their added value is not readily visible to them on the market. Indeed, a key bottleneck lies in the lack of appropriate communication tools to convey the benefits of UCs to consumers and differentiate them from mainstream products (Bayudan et al., 2024). In this landscape, labeling schemes are increasingly recognized as effective mechanisms for transmitting complex credence attributes, such as environmental impact, health benefits, and social value to consumers (Petrescu et al., 2020).

However, no dedicated label currently exists for UCs. There are currently several quality schemes that allow quality attributes to be communicated that partially coincide with those of the UC. We refer in particular to Protected Designations of Origin (PDOs) and Protected Geographical Indications (PGIs), instituted by the European Union to enable consumers to trust and distinguish quality products while also supporting agricultural and processing activities as well as farming systems associated with high-quality products.1 In fact, they are a type of intellectual property right that protects the name of a product which originates from a specific geographical area and whose qualities, reputation, or characteristics are essentially linked to that place. In some cases, these can help promote the quality of UCs, but at the same time they have a number of limitations, related to costs and organizational efforts which are required for registration and management of the scheme. There are also examples of trademarks registered by private entities, such as the well-known Slow Food presidia (Peano et al., 2014), which contribute to protecting agricultural biodiversity and promoting sustainable production systems. However, there is no logo that uniformly communicates the quality of UCs, and therefore ensures that consumers recognize them as such and are willing to reward them in the competitive market. In other words, existing tools are fragmented in scope and not embedded in a holistic framework tailored to the unique values of UCs. This leaves both producers and consumers without a coherent mechanism to communicate or identify UCs in the market.

The communication around the distinctiveness of UCs, especially their taste, tradition, and sustainability aspects, requires tailored messaging strategies and potentially new forms of participatory guarantee systems or traceability tools to establish trust and visibility (Mabhaudhi et al., 2022). In several case studies, labels emphasizing origin, breeding networks, or agrobiodiversity have improved consumer understanding and willingness to pay (Bayudan et al., 2024; Petrescu et al., 2020). Yet much of this success hinges on the alignment of label design with cultural values, clear messaging, and consumer education efforts, particularly in short supply chains or local markets where verbal and relational trust plays a key role.

Given the above-mentioned challenges and opportunities, this study aims to explore the consumers’ perceptions and attitudes toward a potential underutilized crops (UCs) labeling concept across three different European countries, in a cross-national framework. Specifically, the main aims of the study were:

1. to assess consumers’ knowledge of underutilized crops (UCs) and their perceived social, environmental, and economic benefits;

2. to analyse consumers’ interest in a UC label and identifying the socio-demographic, behavioral, and value-based factors influencing their willingness to buy UC-labeled products.

Moreover, to deepen the analysis, the study also examined two specific minor aspects related to the second main objective:

• (2a) whether consumers perceive the UC label as overlapping with existing certifications, such as Organic, PDO and PGI schemes;

• (2b) how different logo designs affect consumer perceptions and willingness to buy across countries.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Questionnaire

A survey was developed to assess the consumers’ perception of and attitude toward a labeling concept for UCs. The survey was initially developed in English and therefore translated into the three languages of the three countries chosen for its dissemination. The three chosen European countries for the dissemination and data gathering of the survey, represent three different pedo-climatic zones: Mediterranean (Italy) Atlantic (Portugal) and Continental (Germany).

The survey was distributed in the three countries through the professional panel provider “Scenari srl”,2 which used the Computer Assisted Web Interviewing technique (with questionnaires posted online and sent via email to respondents who completed them independently). Participants who answered the survey received points that can be redeemed for shopping vouchers to spend online.

About 1,000 respondents had been gathered for each of the three countries under study. The respondents from each country had been selected based on gender (female–male 50–50).

The survey has been developed through a literature review process, and structured into four sections: the sociodemographic variables, the attention to logo information, the consumers’ attitude toward UCs logo concept, and the consumers’ perception of and attitude toward UC logo prototypes. All detailed questions and response options are available in the English version in the Supplementary material 1.

2.1.1 Sociodemographic variables

The survey collected key socio-demographic variables to characterize the participants. Gender identity was assessed with four response options: male, female, other, and prefer not to say. Participants also reported their country of residence, with predefined options for Italy, Portugal, and Germany, while the “other” option was available for those residing elsewhere that led to the end of the survey. Nationality was recorded using a dropdown menu listing all world countries.

Educational attainment was categorized into four levels: lower secondary school, upper secondary school, bachelor’s degree, and post-degree/PhD (Cela et al., 2024). Additionally, participants were asked to indicate the type of context in which they lived, categorized as rural (<10,000 inhabitants), town (10,000–70,000 inhabitants), or city (more than 70,000 inhabitants) (Piochi et al., 2022). Finally, dietary habits were self-reported and classified into four categories: omnivorous, flexitarian, vegetarian, and vegan (Nervo et al., 2024). These socio-demographic variables were included to explore potential relationships between participants’ background characteristics and their attitude toward UCs.

2.1.2 Attention to product information

The survey assessed participants’ attention to product information when purchasing packaged food through three key variables. First, participants reported how often they read food labels over the past 12 months, on a scale with five response options ranging from “1 = never” to “5 = always.” A similar question evaluated the frequency of attention to logos on food packaging, using the same five-point scale. These two questions were adapted by those used by Jefrydin et al. (2019). Additionally, participants were asked to rate the importance of various extrinsic characteristics when choosing food products. These characteristics included low environmental impact, ethical concerns, sensory appeal, health, familiarity, and economic sustainability. The list of characteristics was adapted based on the works of Van Loo et al. (2017) and Cela et al. (2025). Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = totally disagree” to “5 = totally agree.”

2.1.3 UC knowledge and perception

The survey evaluated participants’ familiarity with underutilised crops, their knowledge of the UC concept, and their perceptions of its associated benefits. Participants were first asked whether they had ever heard of the term “underutilised crops,” with a binary response (yes/no). Those who answered “yes” were then presented with three potential definitions and asked to select the one they considered most accurate (UC_definition). Following this, participants were shown the formal definition of underutilised crops, adapted from the Food and Agriculture Organization and the RADIANT project,3 to ensure a common understanding of the term: “Underutilised crops are neglected but valuable species, landrace, variety or cultivar that has limited current use in a given geographic, social, and economic context and that holds great promise to diversify agricultural systems, create resilient agroecosystems, diversify diets, and create economically viable dynamic value chains (for feed, food, and non-food uses).” To direct respondents’ attention to the written definition of UC, the survey page displaying this information was intentionally locked for 10 s, preventing participants from skipping over the text.

To assess participants’ perceptions of the benefits of underutilised crops, they were asked to rate their agreement with 11 potential benefits using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = totally disagree” to “5 = totally agree.” The list of benefits was initially derived from the work of Bayudan et al. (2024) and subsequently refined through additional literature sources (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004; Revoredo-Giha et al., 2022). These benefits covered various dimensions, including health and nutrition (providing nutrients with positive health effects, diversifying diets), cultural aspects (supporting gastronomic and cultural diversity), environmental impact (enhancing environmental resilience, protecting and enhancing agrobiodiversity, preserving landscapes, supporting climate change adaptation and mitigation), and economic factors (improving economic resilience, farm income, product diversification, and reducing external input dependency).

2.1.4 Attitude toward UCs logo concept

This section aimed to provide insights into consumers’ attitudes toward a UC certification, its potential role within the existing labeling system, and the factors influencing consumers’ trust and purchasing decisions regarding underutilised crops. This section assessed participants’ interest in a logo indicating products made from underutilised crops (UCs), their perception of its potential overlap with existing certification logos, and their trust in its reliability. First, respondents rated their interest in a UC logo on a five-point scale ranging from “1 = not at all interested” to “5 = extremely interested.”

To explore the relationship between a UC logo and existing certification schemes, participants were asked to rate the perceived overlap between a UC logo and the organic logo on a five-point scale (1 = not at all overlapping; 5 = extremely overlapping). Those who perceived some level of overlap (scores 2–5) were further asked to identify the shared benefits between the two logos from a predefined list, including aspects such as nutritional benefits, environmental resilience, agrobiodiversity protection, and economic resilience (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004; Bayudan et al., 2024; Revoredo-Giha et al., 2022). Additionally, they were asked to specify which of the previously presented benefits were unique to a UC logo compared to the organic certification. A similar set of questions was presented regarding the overlap between the UC logo and the PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication) logos, to assess the potential positioning of the UC certification within the existing food labeling landscape.

Participants’ trust in the UC logo was further evaluated through seven statements regarding their expectations of its credibility, regulatory framework, environmental impact, product quality assurance, and control system reliability. This question regarding the consumers’ trust toward a potential UC logo was adapted from the work of Zander et al. (2015) who investigated trust toward the organic logo. The seven used statements were: (1) The logo of Underutilized crop will fulfil strict rules; (2) In terms of underutilized crops, I do have a good feeling; (3) I am confident that products labeled as being made from underutilized crops will genuinely be so; (4) The logo of underutilized crops will guarantee that the products are really made of Underutilized crops; (5) The Underutilized crop logo would meet my expectations of protecting the environment; (6) The underutilized crop logo would meet my expectations of high quality products; (7) I would have great trust in the control system behind the underutilized Crops logo. Responses were recorded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = totally disagree” to “5 = strongly agree.” Finally, to measure the potential impact of the UC logo on consumers’ behavior, respondents indicated their willingness to buy food products bearing the UC logo in the future on a seven-point scale ranging from “1 = not at all willing” to “7 = absolutely willing” (Torri et al., 2024).

2.1.5 Perception of and attitude toward UC logo prototypes

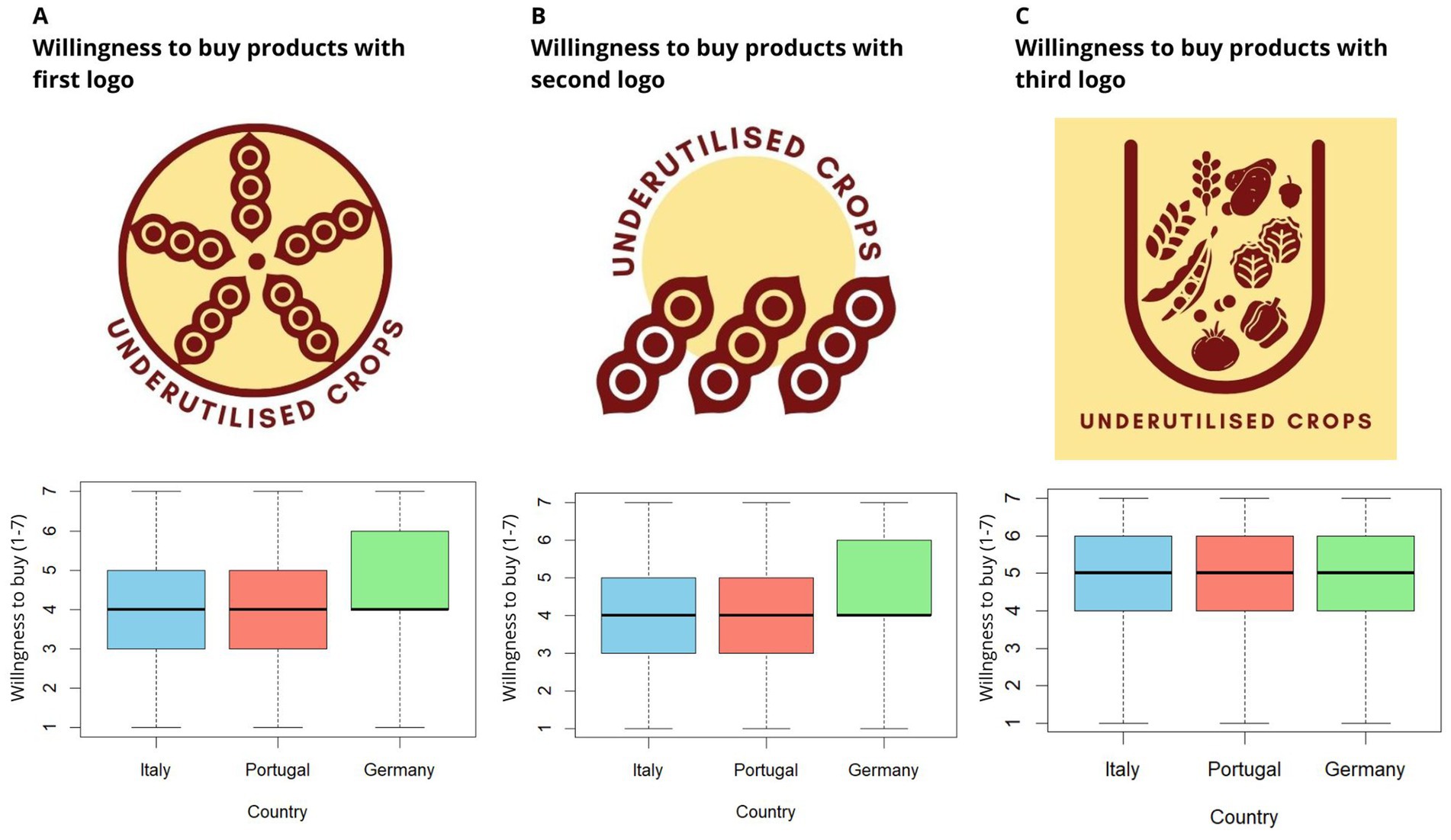

This section presents the survey questions on participants’ perception and willingness to buy products associated with three different prototypes of a future potential UC logo specifically designed for this study and displayed in the Supplementary material 1. The prototypes share the same colors and fonts but differ in terms of image components. The survey aimed to assess whether each logo effectively conveyed key benefits associated with UCs and to evaluate participants’ willingness to buy products displaying these logos.

For each logo, participants were asked two questions presented in a randomized order across participants. Firstly, participants rated the benefits, covering the multiple dimensions already presented in subsection 2.1.3 on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree). Secondly, participants were asked to indicate their willingness to buy food products featuring each of the three logos on a seven-point scale (1 = Not at all willing to buy in the future; 7 = Absolutely willing to buy in the future).

2.2 Statistical analysis

Firstly, the chi-squared test was performed to confront the differences in distribution of the socio-demographic characteristics among the three countries, in order to test if the three countries were comparable.

Secondly, in order to assess the relationship between consumers’ UC knowledge and the perceived benefits associated with UCs, a Mann–Whitney U test (also known as Wilcoxon rank-sum test) was used. This non-parametric test was selected due to the ordinal nature of the data and the violation of normality assumptions, comparing the economic, environmental and social benefit indices between respondents who demonstrated knowledge of the UC concept and those who did not.

Therefore, we tested the differences in distribution of the following two variables between the three countries under study: interest in a UC logo, willingness to buy food products labeled with a UC logo. This test was performed with a Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the Dunn post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction, since the hypothesis of normality of the data distribution was not met.

To identify the socio-demographic and cultural-economic factors influencing consumers’ interest in and willingness to buy products with a UC logo a two-step approach was applied. Firstly, a correlation matrix was constructed to explore associations between the five key outcome variables: interest in a UC logo, willingness to buy a generic UC logo, and willingness to buy each of the three logo design variants. This analysis was then extended to assess correlations between these five outcome variables and a set of socio-demographic characteristics, namely: country, gender, context, educational level, and diet.

To construct a trust index based on the seven related items, two approaches were applied: the first consisted in calculating the row-wise mean of the item scores, and the second involved conducting a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the polychoric correlation matrix, extracting the first principal component (PC1). The PCA results indicated a strong unidimensional structure, with high loadings (0.84–0.88) and 73% of the variance explained by the first component. The individual scores on PC1 were then compared with the mean-based index, yielding an almost perfect correlation (r = 0.999). Given this near-identical outcome, and for reasons of interpretability and simplicity, the mean score was adopted as the reference measure of trust in the analysis.

Subsequently, an ordinal logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the relative contribution of various independent variables to the dependent variable willingness to buy a product with a UC logo. The ordinal logistic regression analysis was firstly performed for all the participants together and then for each of the three countries separately. The regression was structured integrating the socio-demographic variables (country, gender, context, educational level, and diet), the respondents’ familiarity with the term “underutilized crops” and their ability to recognize a correct definition, the mean scores for perceived environmental, economic, and social benefits associated with UCs, the consumers’ label-reading habits and attention to food logos and the six items from the food choice motives question. The categorical variables were transformed into ordinal variables in order to perform regression modeling. This approach allowed us to evaluate both the individual and combined effects of knowledge, values, and socio-demographic traits on consumer willingness to engage with a potential UC label.

To assess consumers’ perceptions of the UC logo in relation to existing certifications—namely the organic label and the PDO/PGI labels—a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted. This non-parametric test was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the data and the non-normal distribution of responses. Specifically, we compared responses to two survey questions that assessed the perceived overlap between the UC logo and the organic logo, and the perceived overlap between the UC logo and PDO/PGI labels. The test was run on the full sample as well as separately by country.

Finally, in order to compare consumers’ responses to three different UC logos across the three countries, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed, a non-parametric alternative to ANOVA, suitable for ordinal data and non-normal distributions. This was followed by Dunn’s post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction to identify pairwise differences between countries. Additionally, Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s tests were applied within each country to assess whether willingness to buy varied significantly between the three proposed logos.

3 Results

3.1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants across the three countries

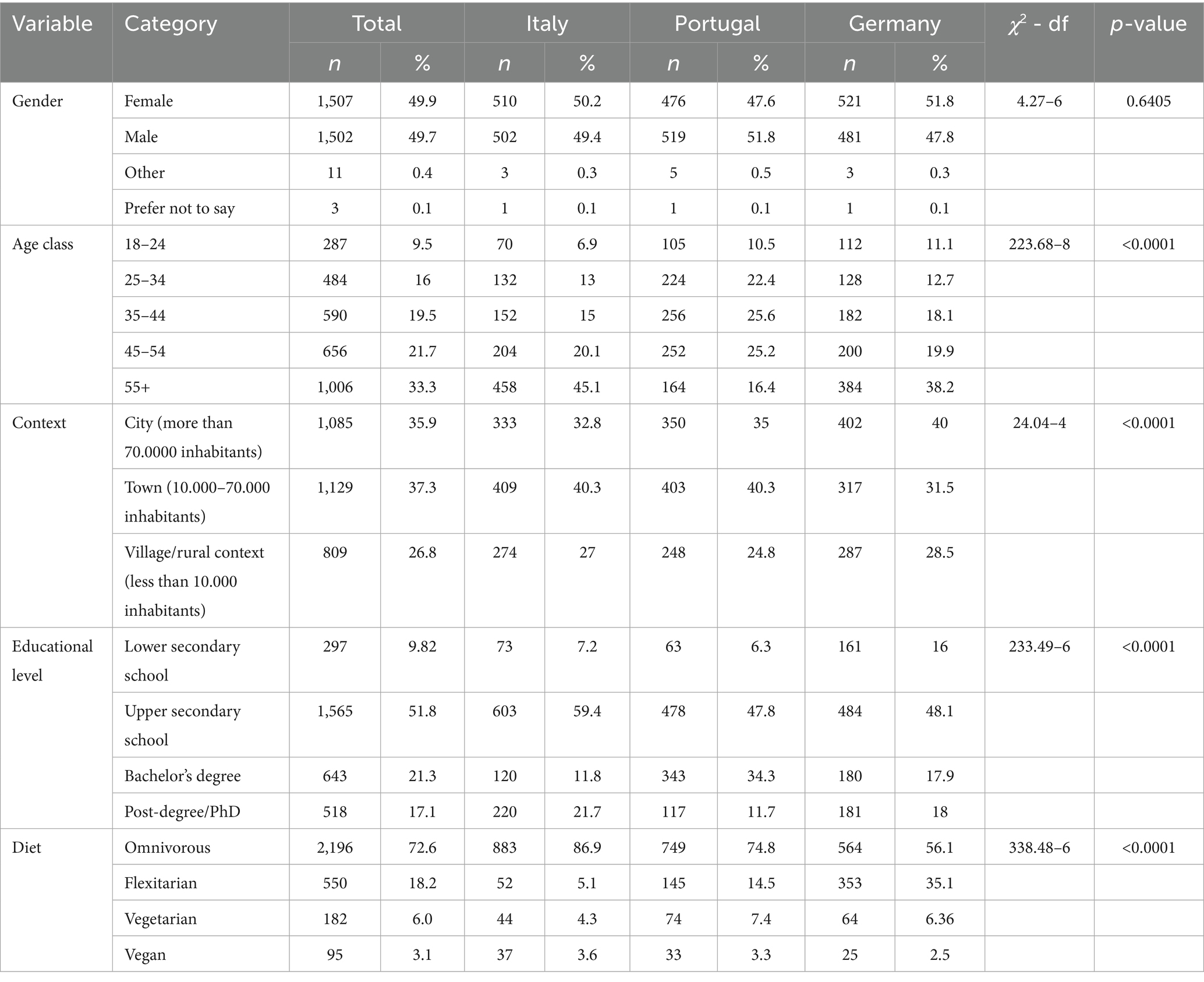

A total of 3,023 people accessed and completed the survey from Italy (n = 1,016), Portugal (n = 1,001), and Germany (n = 1,006) (Table 1).

The sample was balanced by gender and encompassed a wide range of age groups, with a notable representation of older adults. Respondents were drawn from varied residential settings, including urban, suburban, and rural areas, and exhibited diverse educational backgrounds, with a majority having completed at least upper secondary education and a considerable proportion holding university or postgraduate qualifications. Dietary patterns were similarly varied, although omnivorous diets predominated, accompanied by meaningful shares of flexitarian, vegetarian, and vegan respondents.

The results of the Chi-squared test, conducted to compare the distribution of socio-demographic characteristics across the three countries and assess their comparability, indicate that the countries differ significantly for all socio-demographic variables except for gender (Table 1). In all three countries, the proportions of male and female respondents were almost equal, with minimal variation (Italy: 49.4% male, 50.2% female; Portugal: 51.8% male, 48.1% female; Germany: 47.8% male, 51.8% female).

Significant differences emerged in age distribution (p < 0.0001). The Italian sample was older overall, with 45.1% of respondents aged 55 or older. In contrast, Portugal had a higher proportion of younger respondents, with the largest share falling in the 35–44 and 45–54 brackets (25.6 and 25.2% respectively). Germany had a more even distribution, with 38.2% in the 55 + age group and other age classes ranging between 11 and 22%.

Regarding place of residence (p < 0.0001), Italians and Portuguese participants were more likely to live in towns (40.3% each), while Germans were slightly more urban, with 40% residing in cities (more than 70,000 inhabitants). A higher proportion of German respondents also lived in rural areas (28.5%) compared to their Italian and Portuguese counterparts (27 and 24.8%, respectively).

Educational attainment also varied significantly across countries (p < 0.0001). Italian respondents were more likely to have completed upper secondary education (59.4%), while Portugal had the highest percentage of respondents with a bachelor’s degree (34.3%). Germany showed a relatively balanced distribution across upper secondary (48.1%) and post-graduate levels (18%), slightly ahead of Italy and Portugal in the latter category.

Substantial differences were also found in dietary habits (p < 0.0001). While the majority of respondents in all three countries followed an omnivorous diet, this was particularly dominant in Italy (86.9%), followed by Portugal (74.8%). In contrast, Germany had a significantly more diverse dietary profile: only 56.1% were omnivores, while 35.1% identified as flexitarian. Vegetarian and vegan respondents were also more common in Germany (6.4 and 2.5%, respectively) than in the other countries.

3.2 Consumer knowledge of UCs and their associated benefits

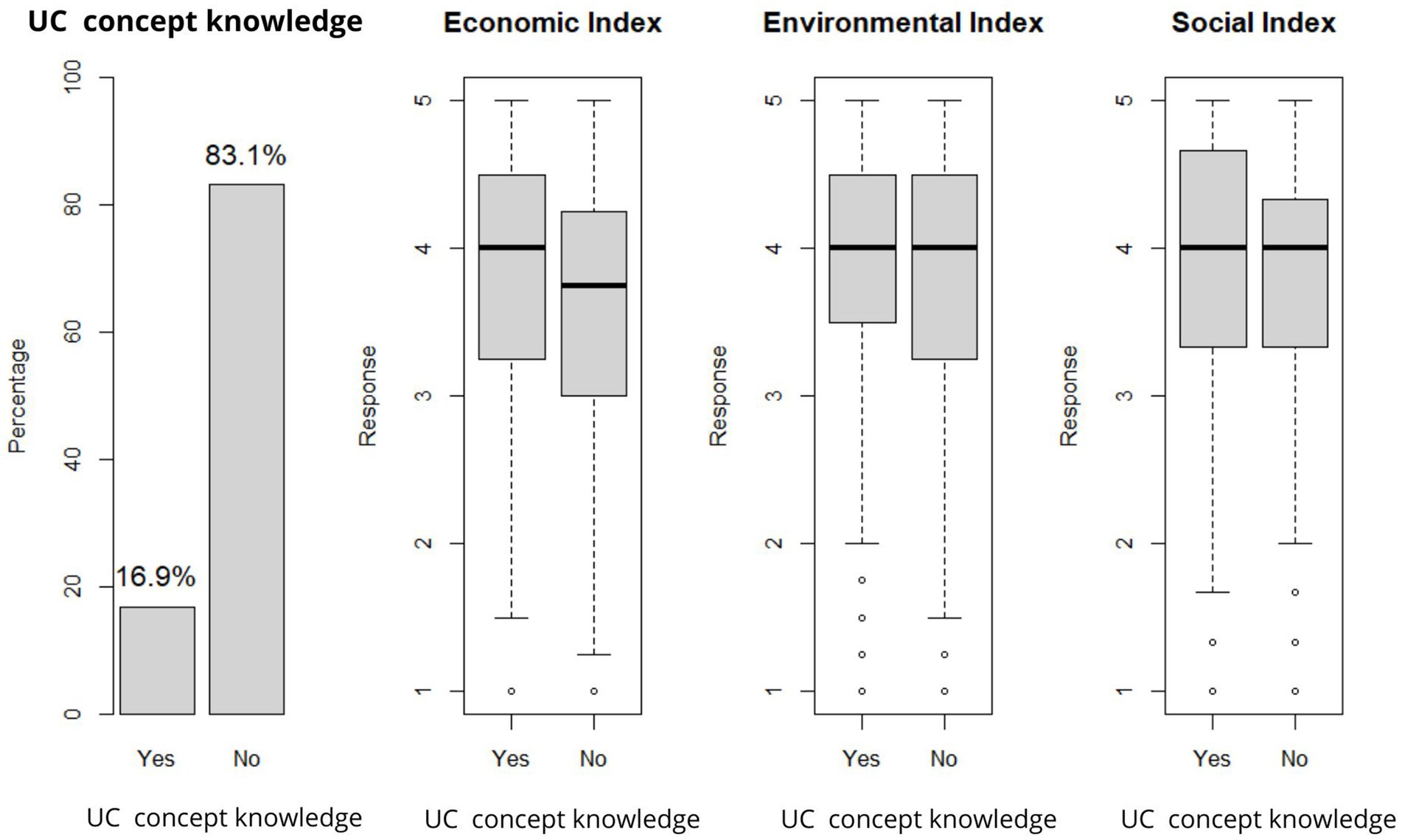

Out of the total sample, 16.9% declared to have heard the term UC before (Figure 1), while the proportion was 27.9% for Germany, 14.2% for Italy and 8.7% for Portugal (Figure 2). To assess the alignment between declared and actual knowledge of the UC concept, we compared participants’ declared knowledge with their ability to correctly identify its definition. Specifically, we calculated the percentage of respondents who selected the correct definition of UCs among those who had previously heard the term. Overall, only 47.2% of participants who declared to know UC selected the correct definition, corresponding to 8.0% of the total sample. When disaggregated by country, the percentage was highest in Portugal (60.2%; corresponding to 5.2% of Portuguese participants), followed by Italy (56.9%; corresponding to 8.1% of Italian participants), and lowest in Germany (38.0%; corresponding to 10.6% of German participants).

Figure 1. General consumer knowledge of UCs and their associated social, environmental, and economic benefits.

Figure 2. Consumer knowledge of UCs and their associated social, environmental, and economic benefits for each country.

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test, conducted to assess whether knowledge of the underutilized crops concept was associated with differing perceptions of their economic, environmental, and social benefits, indicate statistically significant differences across all three benefit indices (Economic index: W = 722,408, p < 0.0001; Environmental index: W = 705,371, p < 0.0001; Social index: W = 722,086, p < 0.0001). Specifically, participants familiar with the UC concept assigned higher scores on average to the economic, environmental, and social value of UCs than those who were unfamiliar with the term.

The economic benefit index showed the clearest divergence: participants who knew the UC concept had a higher median score (4.00) than those who did not (3.75). While the medians for the environmental and social indices were both equal at 4.00 across the two groups, the Mann–Whitney test revealed differences in their underlying distributions. This suggests that beyond central tendency, variability or skewness in responses differed depending on UC knowledge—highlighting nuanced distinctions in how benefits are perceived.

Despite the majority of respondents (83.1%) stated they were unfamiliar with the UC concept, those who declared to know it consistently attributed greater benefit scores to UCs. This pattern suggests that knowledge of UCs is positively associated with more favorable perceptions of their contribution to economic viability, environmental sustainability, and social value (Figure 1).

Across the three countries analysed, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were conducted to compare index scores (Economic, Environmental and Social indices) between respondents who recognized the UC logo and those who did not. Alongside the statistical tests, effect sizes were computed using Rosenthal’s r, a standardized measure that quantifies the magnitude of the difference between groups. In Italy, no statistically significant differences were found (Economic: W = 67,137, p = 0.179, r = 0.042; Environmental: W = 66,289, p = 0.280, r = 0.034; Social: W = 66,035, p = 0.314, r = 0.032) and all effect sizes were negligible. In contrast, Portugal showed significant differences for the Economic (W = 48,474, p = 0.002, r = 0.099) and Social indices (W = 49,585, p = 0,000, r = 0.112), with small effect sizes, while the Environmental index did not reach significance (W = 44,504, p = 0.112, r = 0.050). In Germany, none of the comparisons were statistically significant (Economic: W = 106,921, p = 0.128, r = 0.048; Environmental: W = 107,114, p = 0.116, r = 0.050; Social: W = 105,400, p = 0.248, r = 0.037) and all effect sizes were very small. Overall, these results suggest that in Portugal, UC knowledge was modestly associated with differences in the economic and social dimensions, while in Italy and Germany, both statistical and practical differences appear negligible (Figure 2).

These findings suggest that overall UC knowledge positively shapes perceptions of the benefits of underutilized crops, though the strength of this association may vary across national contexts. This underlines the importance of targeted communication and education strategies to enhance consumer understanding, which in turn may foster more favorable attitudes toward UCs and related sustainability goals.

3.3 Consumers’ interest in a potential UC label and their willingness to buy products bearing such a label

The distributions of the two variables interest in a UC label and willingness to buy products with a UC label were compared across Italy, Portugal, and Germany.

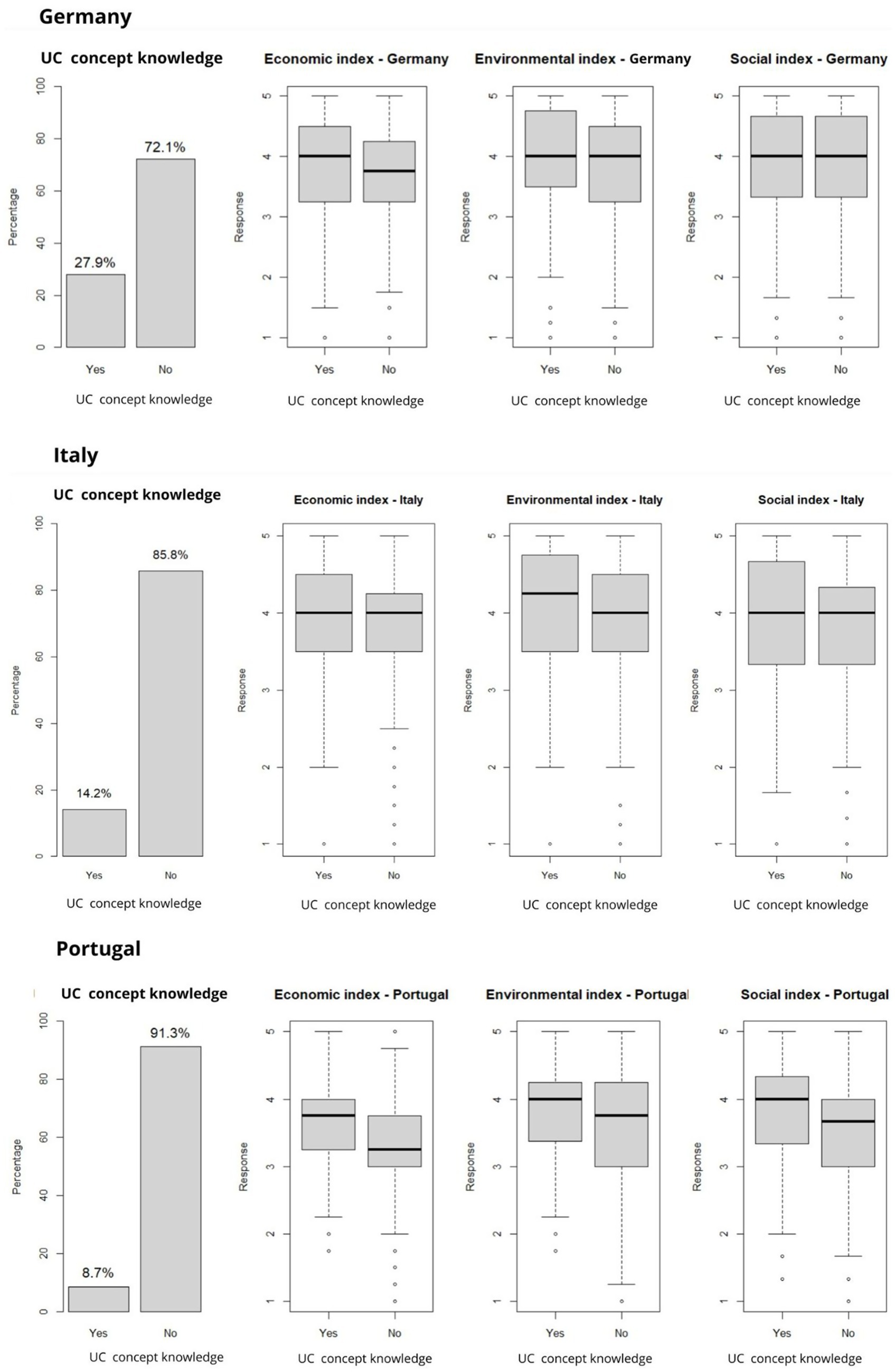

For interest in the UC label, the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a statistically significant difference between countries (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 113.05, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Post-hoc comparisons showed that the Portuguese sample differed significantly from both Italy (p < 0.0001) and Germany (p < 0.0001), with Portuguese respondents reporting a lower median level of interest (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Differences in interest toward and willingness to buy a UC logo between the respondents of Italy, Portugal and Germany.

No statistically significant difference was found between the Italian and German samples (p = 0.46). The mean interest scores were 3.56 for Italy, 3.05 for Portugal, and 3.62 for Germany.

Similarly, for willingness to buy products with a UC label, the Kruskal–Wallis test again showed a significant difference across countries (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 19.37, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Dunn’s test confirmed that Portugal differed significantly from both Italy (p < 0.0001) and Germany (p = 0.004), while no significant difference was observed between the latter two (p = 0.283). Mean willingness scores were 4.92 in Italy, 4.56 in Portugal, and 4.84 in Germany, indicating an overall high level of willingness across all three countries, but with a notably lower value in Portugal.

3.4 Socio-demographic and cultural-economic factors influencing the interest in and willingness to buy products with a UC logo

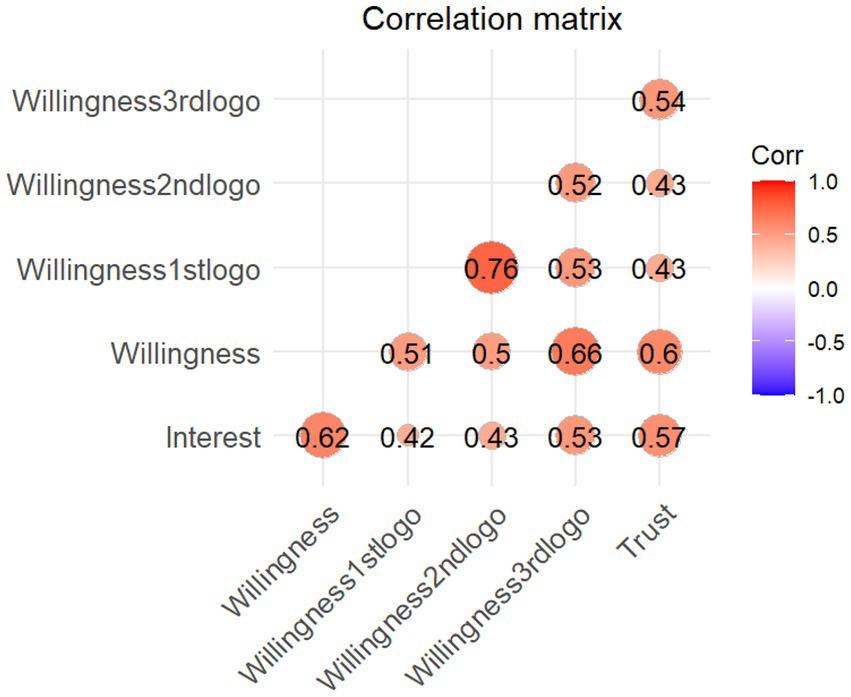

The correlation matrix among interest in a UC logo, willingness to buy products with a UC logo, and willingness to buy products featuring each of the three proposed UC logo designs is reported in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Correlation matrix between the five variables: interest in a UC logo, willingness to buy products with UC logo, and the willingness to buy products with the three proposed UC logo designs.

As these variables were positively correlated, we selected willingness to buy products with a UC logo as the dependent variable for further analysis of the influence of socio-demographic factors.

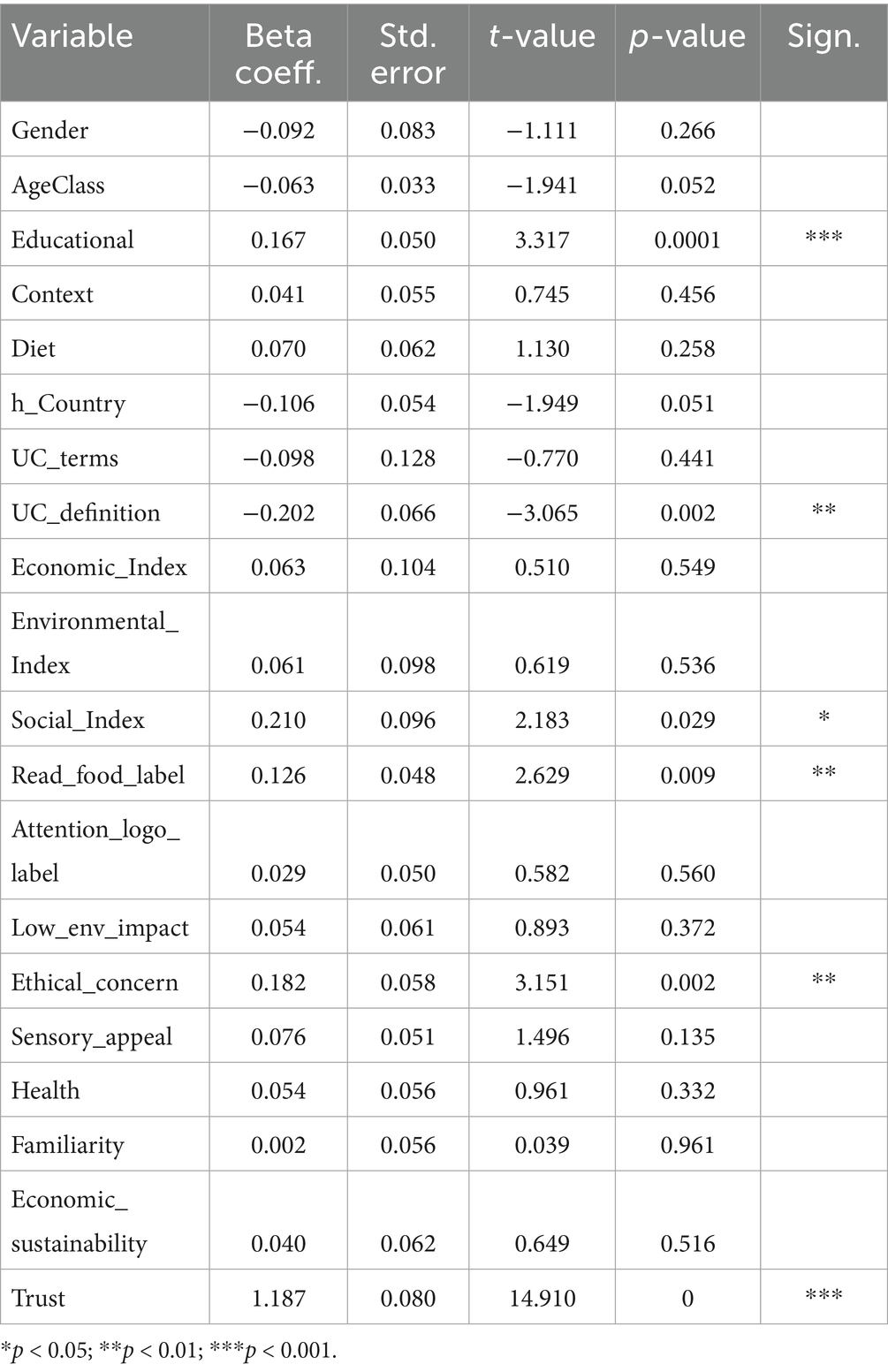

In the overall sample, the most significant predictors of willingness to buy a product with a UC logo were the perceived social benefits of UCs (beta = 0.210, p = 0.029), the knowledge of the UC definition (beta = −0.202, p = 0.002), trust in the UC logo (beta = 1.187, p < 0.0001), educational level (beta = 0.167, p < 0.0001), ethical concern (beta = 0.182, p = 0.002), and habitual reading of food labels (beta = 0.126, p = 0.009) (Table 2). The negative beta coefficient value of UC_definition (−0.202) suggests that respondents who choose definitions 2 and 3 were more willing to buy than those who choose definition 1. Given that the second definition was the correct one for UCs, results suggest that respondents who know the UC definition are more likely to buy a product with a UC logo than those who provided the first wrong definition. The overall Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of the regression model was 4791.81, while for the individual country the values were 1656.62 for Germany, 1444.98 for Italy, and 1694.97 for Portugal. These regression models were chosen because the AIC values were low, both for the overall model and for the countries taken individually, indicating that these models well represent the dependent variable.

Table 2. Ordinal logistic regression model explaining the willingness to buy a product with a UC logo of the total sample.

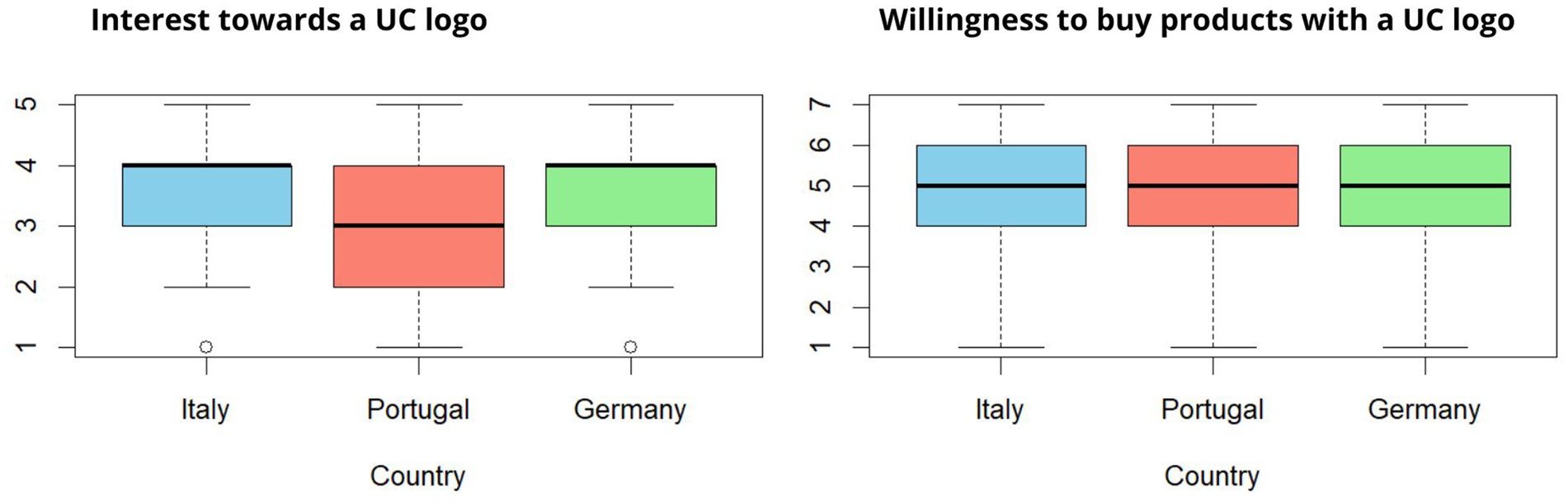

3.5 Consumer perceptions of the UC logo in relation to organic, PDO, and PGI schemes

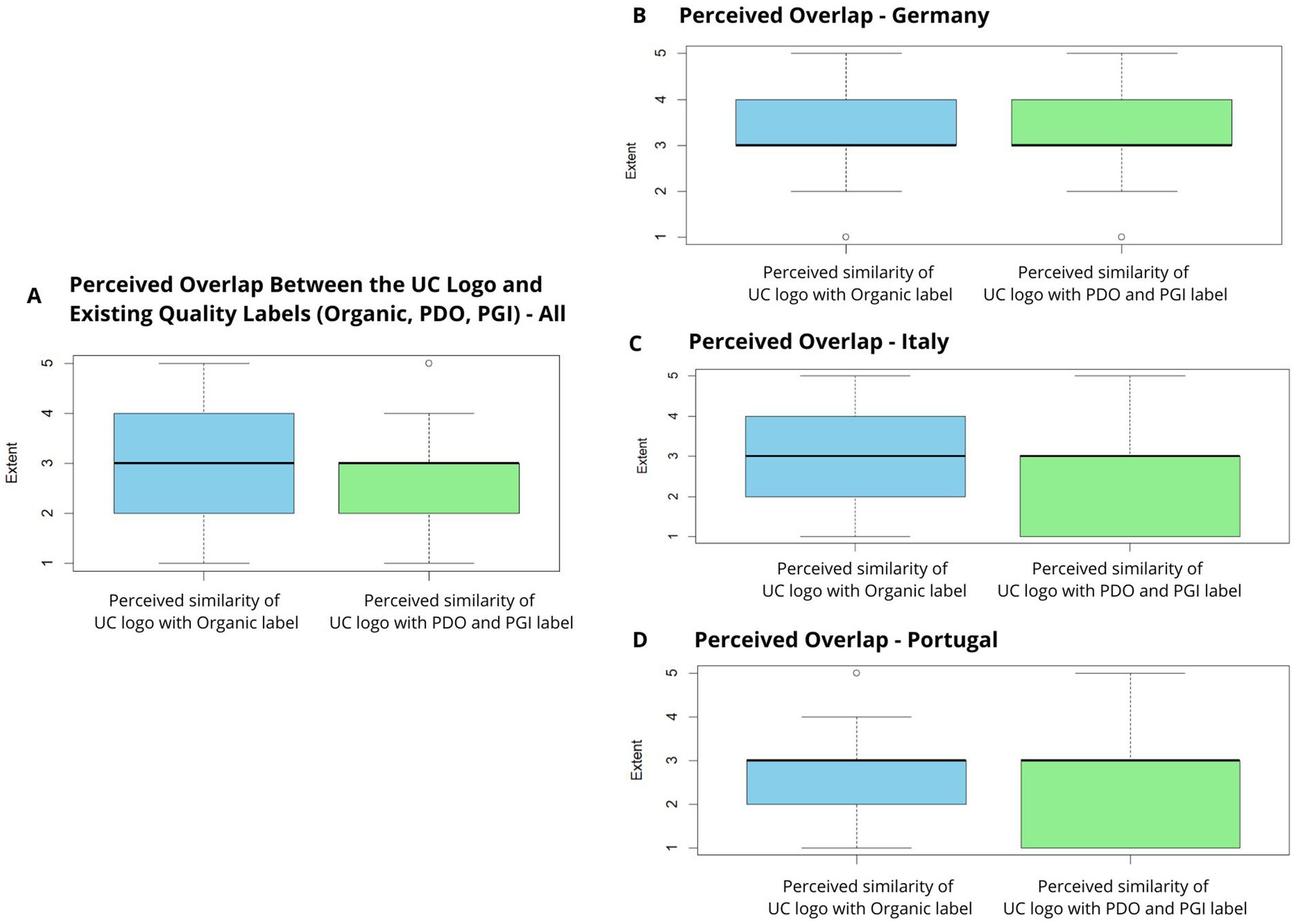

The results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (W = 656,311, p < 0.0001) revealed a statistically significant difference in how participants perceived the extent of similarity between a potential underutilized crops (UC) logo and existing food schemes. Specifically, participants generally perceived the UC logo to overlap more with the organic certification (mean = 2.98; median = 3) than with the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) labels (mean = 2.71; median = 3) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Perceived overlap between the UC logo and existing quality labels (Organic, PDO, PGI). (A) All countries combined. (B) Germany. (C) Italy. (D) Portugal.

As illustrated in the boxplots B, C, D, the median rating for the similarity between the UC logo and the organic label was higher compared to that of the UC logo and the PDO/PGI certifications across all three countries. For Germany specifically, the mean rating for the UC–Organic similarity was 3.31, with a median of 3 and for the UC-PDO/PGI similarity was 3.09, with a median of 3. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded W = 58,370 and a p < 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant difference between perceptions of the UC logo’s alignment with Organic versus PDO/PGI certifications. For Italy specifically, the mean rating for the UC–Organic similarity was 2.96, with a median of 3 and for the UC-PDO/PGI similarity was 2.54, with a median of 3. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded W = 89,796 and a p < 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant difference between perceptions of the UC logo’s alignment with Organic versus PDO/PGI certifications. For Portugal specifically, the mean rating for the UC–Organic similarity was 2.68, with a median of 3 and for the UC-PDO/PGI similarity was 2.50, with a median of 3. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded W = 71,535 and a p < 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant difference between perceptions of the UC logo’s alignment with Organic versus PDO/PGI certifications. This indicates a more frequent association of the UC logo with organic principles, such as environmental sustainability and natural production methods, than with quality schemes like PDO and PGI.

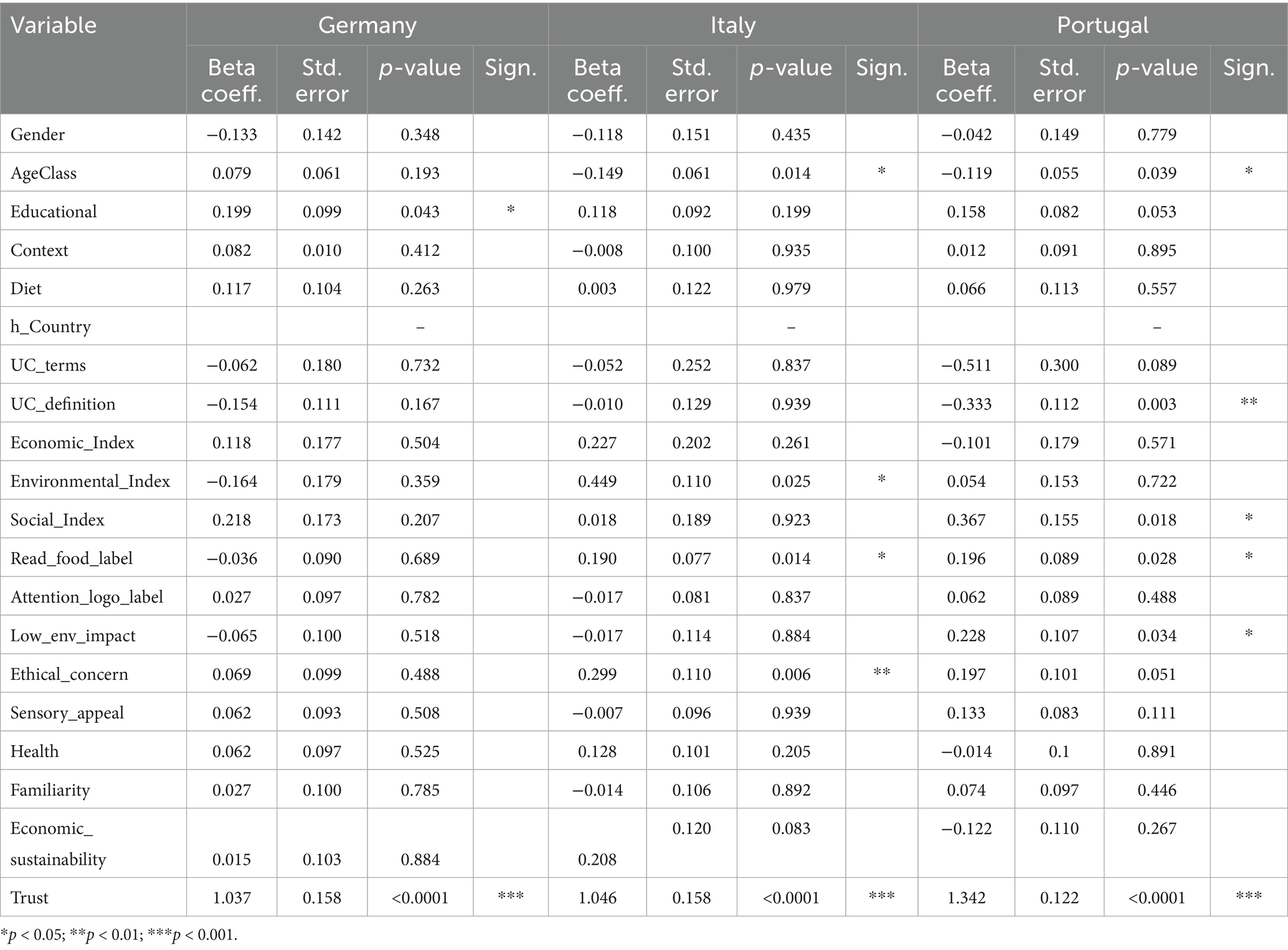

Country-level models revealed important differences (Table 3). In Germany, educational level (beta = 0.199, p = 0.043) and trust (beta = 1.037, p < 0.0001) were again the strongest predictors. In Italy, environmental benefit perception (beta = 0.499, p = 0.025) were the most important, followed by ethical concern (beta = 0.299, p = 0.006), habitual reading of food labels (beta = 0.190, p = 0.014), the age class (beta = 0.149, p = 0.014), and trust (beta = 1.046, p < 0.0001). In Portugal, significant predictors included social benefit perception (beta = 0.367, p = 0.018), knowledge of UC definition (beta = −0.333, p = 0.003), low environmental impact (beta = 0.228, p = 0.034), ethical concern (beta = 0.197, p = 0.051), reading food labels (beta = 0.196, p = 0.028), educational (beta = 0.158, p = 0.053), trust (beta = 1.342, p < 0.0001), and age class (beta = 0–0.119, p = 0.039). These results suggest that predictors of willingness to buy across countries variables varies by national context.

Table 3. Ordinal logistic regression model explaining the willingness to buy products with a UC logo of each country.

This trend was consistent across Italy, Germany, and Portugal. However, while the perceived similarity with the organic label showed greater variability, suggesting a broader range of interpretations among respondents, the responses regarding the overlap with PDO/PGI labels were more tightly clustered. This suggests more consensus in viewing the UC logo as less aligned with these origin-based certifications. A few outliers were observed in the PDO/PGI responses, indicating some divergent perspectives on this point.

Overall, these findings suggest that consumers conceptually link underutilized crops more closely with environmentally and ethically motivated labels like Organic than with territorially anchored schemes like PDO or PGI. This underscores the importance of carefully positioning and communicating a UC label to ensure its distinct identity within the crowded landscape of food certification schemes.

3.6 Cross-country comparison of consumers’ responses to three UC logo designs

Figure 6 shows the boxplots of the willingness to buy products labeled with the three logo designs across the three countries. The analysis revealed significant differences in willingness to buy across countries for each of the three UC logo designs 1st logo: Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 79.59, df = 2, p < 0.0001; 2nd logo: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 86.53, df = 2, p < 0.0001; 3rd logo: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 7.65, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons confirmed statistically significant differences in willingness to buy between Italy, Portugal, and Germany for the first (Italy-Portugal: p < 0.0001; Portugal-Germany: p < 0.0001; Italy-Germany: p = 0.003) and second logos (Italy-Portugal: p < 0.0001; Portugal-Germany: p < 0.0001; Italy-Germany: p = 0.007). For the third logo, significant differences emerged between Italy and Portugal (p = 0.002), and between Portugal and Germany (p < 0.0001).

Figure 6. Willingness to buy products displaying the three logos across the three countries. (A) Willingness to buy products with the first logo. (B) Willingness to buy products with the second logo. (C) Willingness to buy products with the third logo.

When exploring willingness to buy the different logos within each country, significant differences were found across all three logos in Italy (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 96.39, df = 2, p < 0.0001), Portugal (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 136.08, df = 2, p < 0.0001), and Germany (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 48.41, df = 2, p < 0.0001). Specifically, post-hoc Dunn tests showed that the third logo consistently stood out: in all three countries, it differed significantly from the first and second logos (Italy: 1st-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 2nd-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 1st-2nd logo: p = 0.370; Portugal: 1st-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 2nd-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 1st-2nd logo: p = 0.360; Germany: 1st-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 2nd-3rd logo: p < 0.0001; 1st-2nd logo: p = 0.430). The third logo received the highest willingness to buy scores across all countries, suggesting it may have greater consumer appeal than the other two designs. These findings indicate that while national contexts influence the perception of individual logos, there is a consistent preference for the third logo design across all three countries, making it a potentially strong candidate for broader adoption.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to assess consumers’ perceptions of a potential label for underutilized crops (UCs) across three European countries (Italy, Portugal, and Germany) by analysing knowledge, perceived benefits, willingness to buy, and the influence of socio-demographic and value-based factors. The findings reveal a number of significant insights that contribute to ongoing debate on food labeling, consumers’ engagement, and the mainstreaming of agrobiodiversity. The diversity of respondents across the three countries allowed for a comparative understanding of consumers’ perceptions.

4.1 Consumers’ knowledge of UCs and their associated social, environmental, and economic benefits

Our results showed that knowledge of the concept of underutilized crops positively influences the perception of their associated economic, environmental, and social benefits. Even though the majority of respondents reported being unfamiliar with the UC term, those who had prior knowledge consistently rated their benefits more highly. Interestingly, the clearest difference emerged around economic benefits, perhaps suggesting that consumers who are more informed associate UCs not only with sustainability but also with opportunities for local economic revitalization and food system resilience.

The emerged limited knowledge of UC limits the potential effectiveness of a certifying label. Indeed, labels can only influence consumer choices when there is sufficient understanding of what they represent (Cook et al., 2023). Therefore, before implementing labeling strategies, efforts should focus on raising public awareness about UCs, emphasizing their environmental, nutritional, and agronomic benefits. Educational campaigns and targeted communication initiatives are essential to build a foundation of knowledge that allows consumers to recognize and value labels (Pilon et al., 2017), such as UCs label. In this context, a certifying label should be seen not as a standalone solution, but as part of a broader strategy to increase consumer familiarity and understanding. Future work should explore the most effective ways to communicate the benefits of UCs to diverse audiences and support their integration into the mainstream food system.

4.2 Consumers’ interest in a potential UC label and their willingness to buy products bearing such a label

Participants across all three countries expressed moderate to high interest in a potential UC logo and a general willingness to purchase UC-labeled products. However, both interest and willingness to buy were significantly lower in Portugal compared to Italy and Germany. This may reflect either lower public exposure to sustainability-oriented food communication or cultural differences in consumer trust and engagement with certification schemes.

The results of the ordinal logistic regression analyses showed that certain socio-demographic characteristics, such as education level, habitual reading of food labels, ethical concern and perceived social benefits, significantly influenced respondents’ willingness to buy UC-labeled products. Thus, these characteristics played a crucial role in shaping responses, in agreement with previous literature on consumers’ perception of food labeling. For instance, it was reported that consumers who pay attention to organic labeling and those considering the ethical dimension when shopping were more likely to be willing to buy organic food products (De Magistris and Gracia, 2025). Moreover, research investigating the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and the influence of eco-labels on consumer decision making, showed that age and education level were significant in shaping consumers’ consideration of and expectations for environmentally sustainable food packaging (Chirilli et al., 2022).

Trust emerged as one of the significant predictors of willingness to buy, across all models and countries. In this study, trust was conceptualized as a construct encompassing participants’ expectations and beliefs about the reliability, credibility, and integrity of the information signaled by the label. This framing aligns with definitions proposed in a previous work where trust in organic food and its certification was explored (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004) or in other researches (Truong et al., 2021), where trust is seen as a psychological mechanism that reduces perceived complexity and risk, especially in contexts where consumers have limited direct experience or knowledge — such as with novel food products or labeling schemes. For instance, it was emphasized that trust in food industry mediates the willingness to purchase functional foods labeled with health claims (Siegrist et al., 2008). In the context of organic labels, previous research found that the highest price premiums were associated with logos that were widely recognized and trusted, particularly those perceived as adhering to rigorous organic standards and supported by a strict control system (Janssen and Hamm, 2012). Building on this literature, we argue that trust plays a similar role in shaping consumer responses to UCs, acting as a filter for label information processing.

The country-specific models highlight how consumer willingness to engage with a UC label is shaped by national context. In Italy, environmental values, age, ethical concern, and food label-reading habits stood out. In Portugal, social value perception, knowledge of the term UC, and environmental sustainability emerged as key drivers. These findings suggest that while trust is universally important, messaging and policy efforts should be tailored to local cultural values and consumer profiles.

Participants perceived the potential UC logo as more closely aligned with the organic label than with PDO/PGI schemes. This suggests that UCs are conceptually associated with principles of ecological sustainability and natural production methods, rather than with territorial origin or authenticity. This positioning, while useful for aligning with environmental values, also presents a challenge: how to distinguish the UC logo from existing organic certifications without causing confusion. Importantly, participants recognized unique features of UCs, such as biodiversity enhancement and climate resilience, which are currently underrepresented in mainstream labels.

Across the three logo prototypes tested, one design consistently received the highest willingness-to-buy scores in all countries, indicating a strong and replicable visual appeal. However, there were significant differences in the mean scores of the other two logos across countries, highlighting the role of cultural preferences in visual interpretation. The preferred logo likely succeeded in visually communicating values, such as naturalness, ecological commitment, or tradition, that resonate across contexts. This insight can inform the participatory refinement of a future UC logo design. Indeed, it should be recognized that the three logo prototypes were designed without applying an experimental plan with specific variables varying in different levels, with the purpose to obtain some preliminary consumers’ insights. In the future, it will be useful to develop a UC logo based on the application of a discrete choice experiment (Lizin et al., 2022).

4.3 Mapping opportunities and constraints for the development of a UC label

This study contributes to the growing body of research advocating for the strategic reintegration of underutilized crops (UCs) into mainstream food systems, not only for their agronomic potential, but also for their environmental, nutritional, and socio-cultural significance (Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004; Mabhaudhi et al., 2022; Bayudan et al., 2024). UCs are increasingly recognized as vital contributors to agroecological transition pathways, thanks to their adaptability to marginal environments, low input requirements, and links to traditional knowledge systems (Jenkins et al., 2023; Dawson et al., 2019). By diversifying production and consumption, UCs help counter the ongoing erosion of agrobiodiversity and reduce dependency on a narrow set of high-yield crops that currently dominate the global food supply (Khoury et al., 2014; FAO, 2019).

The introduction of a dedicated UC label could be a key tool for increasing visibility and market recognition of these crops. As our findings suggest, a well-designed label can enhance consumer trust, trigger value-based purchasing decisions, and foster better understanding of the multidimensional benefits UCs provide, including contributions to ecosystem services, cultural heritage, and nutritional diversity (Petrescu et al., 2020). At the same time, the development of such a label must address existing challenges in the European labeling landscape, which is currently fragmented, often oriented around territorial identity, and insufficiently equipped to capture the agroecological and socio-cultural values embodied by UCs (Revoredo-Giha et al., 2022; Mariani et al., 2021).

Consumers respond positively when the communication of quality and sustainability attributes is embedded in clear, credible, and culturally resonant messages, yet labeling alone is not enough. The success of a UC logo depends on participatory governance, transparent criteria, and complementary strategies such as education campaigns, short supply chains, and support for community seed systems (Nicita et al., 2023).

Importantly, the role of UCs extends beyond the marketplace. These crops are often cultivated by small-scale farmers, many of whom are stewards of local agrobiodiversity and holders of traditional knowledge (Jenkins et al., 2023; Padulosi and Hoeschle-Zeledon, 2004). A UC label, if inclusively designed, could empower these actors by providing them with a legitimate channel to communicate the unique value of their products, supporting not only environmental sustainability, but also food sovereignty and social equity (Mabhaudhi et al., 2022; Bayudan et al., 2024).

In this sense, the design of a UC label must be situated within a broader vision of food system transformation, one that centres biodiversity, justice, and resilience. Future research could deepen this work by involving producers and civil society in co-designing labeling criteria, testing the logo in real-world market settings, and exploring legal pathways for official recognition. Moreover, in the future it will be necessary to reflect on the entity that would be supposed to release the UC logo. Given that it would be probably difficult for EU (or national) institutions to promote such a scheme, it seems much more plausible that the UC logo would fall within the category of voluntary certification schemes managed by private operators (following the model of fair trade or Slow Food presidia). In any case, it will be interesting to investigate if and how the institution releasing the UC logo can influence consumers’ perception of the truthfulness of the logo itself.

The findings of this study offer a foundation for such efforts, suggesting that with the right design, communication, and institutional support, a UC label could serve as a bridge between consumer values and the systemic changes needed to sustain agrobiodiversity and culturally appropriate diets.

4.4 Limitations of the study

Several limitations of this study should be recognized. Initially, it should be noted that the samples from the three countries were neither entirely representative of their national populations nor completely comparable in terms of sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, educational level, dietary habits), a limitation frequently associated with online survey researches (Torri et al., 2024; Grasso et al., 2019; Migliavada et al., 2022). Secondly, the survey was open to all potential participants. However, given the inclusion of questions regarding willingness to buy, restricting participation to individuals responsible for grocery shopping within their household could have provided more accurate insights into the prospective impact of the UC logo on consumers’ responses to food products that may be introduced to the market in the future. Thirdly, an explanation of the meaning of organic and PDO/PGI logos was not included in the survey, thus there was not the certainty that respondents correctly understood or knew what kind of label the survey was referring to. Overall, these limitations highlight the exploratory nature of the study, suggesting that the results should be interpreted with caution and that future research is needed to better understand consumers’ attitudes toward a potential specific label for underutilized crops.

5 Conclusion

This study explored consumer knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward a potential label for underutilized crops (UCs) across three European countries: Italy, Portugal, and Germany. The findings highlight a generally positive orientation toward UCs and their associated benefits, particularly among participants who demonstrated prior knowledge of the concept. Consumers who were aware of UCs tended to perceive higher social, economic, and environmental benefits, and expressed greater willingness to purchase products bearing a dedicated UC logo.

Trust emerged as a critical determinant of purchase intention, strongly influencing willingness to buy across all contexts. In the absence of trust, factors such as perceived social and environmental benefits, ethical concern, food label engagement, and education became key predictors. Cross-country differences also surfaced, suggesting that communication strategies must be tailored to national cultural and consumer contexts.

The potential UC logo was perceived as more closely aligned with the organic label than with PDO or PGI schemes, indicating an opportunity to position UCs within the sustainability narrative, but also a risk of confusion with existing schemes. Among the three proposed designs, one logo consistently elicited higher willingness to buy scores, underscoring the importance of visual identity and cultural resonance.

Overall, these findings support the feasibility and value of a dedicated UC label to enhance consumer awareness, guide informed food choices, and support biodiversity-based agricultural systems. However, for such a label to succeed, it must be embedded in transparent governance, culturally attuned communication, and inclusive co-design processes that reflect the diverse values underpinning underutilized crops.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committee of the University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo (Ethics Committee Proceeding no. 120225), prior dissemination and conducted in accordance with the international ethical guidelines for research involving humans established in the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. VB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article has been funded by the Project Realizing Dynamic Value Chains for underutilized Crops (RADIANT), a Research and Innovation Action supported by European Commission’s Horizon 2020 program (Grant number 101000622).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1629395/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

References

Bayudan, S., De Steur, H., and Schouteten, J. J. (2024). From niche to noteworthy: a multi-country study on consumer views towards neglected and underutilized crops. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 38:101052. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2024.101052

Bravo, I., Colamatteo, I., Balzano, S., Cappelli, L., and Iannucci, E. (2024). Consumer behaviour regarding certified food. Sustainability 16:757. doi: 10.3390/su16093757

Cardoso, V. A., Lourenzani, A. E. B. S., Caldas, M. M., Bernardo, C. H. C., and Bernardo, R. (2022). The benefits and barriers of geographical indications to producers: a review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 37, 707–719. doi: 10.1017/S174217052200031X

Cela, N., Fontefrancesco, M. F., and Torri, L. (2024). Fruitful brewing: exploring consumers’ and producers’ attitudes towards beer produced with local fruit and Agroindustrial by-products. Foods. 13:2674. doi: 10.3390/foods13172674

Cela, N., Fontefrancesco, M. F., and Torri, L. (2025). Predicting consumers’ attitude towards and willingness to buy beer brewed with agroindustrial by-products. Food Qual. Prefer. 126:105414. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2024.105414

Chirilli, C., Molino, M., and Torri, L. (2022). Consumers’ awareness, behavior and expectations for food packaging environmental sustainability: influence of socio-demographic characteristics. Foods. 11:2388. doi: 10.3390/foods11162388

Cook, B., Costa Leite, J., Rayner, M., Stoffel, S., van Rijn, E., and Wollgast, J. (2023). Consumer interaction with sustainability labelling on food products: a narrative literature review. Nutrients 15:387. doi: 10.3390/nu15173837

Dawson, I. K., Park, S. E., Attwood, S. J., Jamnadass, R., Powell, W., Sunderland, T., et al. (2019). Contributions of biodiversity to the sustainable intensification of food production. Glob. Food Sec. 21, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.07.002

De Magistris, T., and Gracia, A. (2025). Do consumers pay attention to the organic label when shopping organic food in Italy? London: INTECH Open Access Publisher.

Grasso, A. C., Hung, Y., Olthof, M. R., Verbeke, W., and Brouwer, I. A. (2019). Older consumers’ readiness to accept alternative, more sustainable protein sources in the European Union. Nutrients 11:904. doi: 10.3390/nu11081904

Janssen, M., and Hamm, U. (2012). Product labelling in the market for organic food: consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Qual. Prefer. 25, 9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.12.004

Jefrydin, N., Md Nor, N., and Abd Talib, R. (2019). Nutrition labelling: an exploratory study on personal factors that influence the practice of reading nutrition labels among adolescents. Malays. J. Nutr. 25, 143–153. doi: 10.31246/mjn-2018-0123

Jenkins, T., Landschoot, S., Dewitte, K., Haesaert, G., Reade, J., and Randall, N. (2023). Evidence of development of underutilised crops and their ecosystem services in Europe: a systematic mapping approach. CABI Agric. Biosci. 4, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s43170-023-00194-y

Khoury, C. K., Bjorkman, A. D., Dempewolf, H., Ramirez-Villegas, J., Guarino, L., Jarvis, A., et al. (2014). Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4001–4006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313490111

Lizin, S., Rousseau, S., Kessels, R., Meulders, M., Pepermans, G., Speelman, S., et al. (2022). The state of the art of discrete choice experiments in food research. Food Qual. Prefer. 102:104678. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104678

Mabhaudhi, T., Hlahla, S., Chimonyo, V. G. P., Henriksson, R., Chibarabada, T. P., Murugani, V. G., et al. (2022). Diversity and diversification: ecosystem services derived from underutilized crops and their co-benefits for sustainable agricultural landscapes and resilient food systems in Africa. Front. Agron. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2022.859223

Mariani, M., Cerdan, C., and Peri, I. (2021). Origin food schemes and the paradox of reducing diversity to defend it. Sociol. Ruralis 61, 465–490. doi: 10.1111/soru.12330

Migliavada, R., Coricelli, C., Bolat, E. E., Uçuk, C., and Torri, L. (2022). The modulation of sustainability knowledge and impulsivity traits on the consumption of foods of animal and plant origin in Italy and Turkey. Sci. Rep. 12:20036. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24325-z

Nervo, C., Ragazzini, C., and Torri, L. (2024). Effect of jellyfish body parts and presentation form on consumers liking, sensory perception, emotions, and food pairings. Foods. 13:872. doi: 10.3390/foods13121872

Nicita, L., Bosello, F., Standardi, G., and Mendelsohn, R. (2023). An integrated assessment of the impact of agrobiodiversity on the economy of the Euro-Mediterranean region. Ecol. Econ. 2024:108125. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108125

Padulosi, S., and Hoeschle-Zeledon, I. (2004). Underutilized plant species: what are they? Leisa-Leusden. 20, 5–6.

Peano, C., Migliorini, P., and Sottile, F. (2014). A methodology for the sustainability assessment of Agri-food systems: an application to the slow food presidia project. Ecol. Soc. 19:424. doi: 10.5751/ES-06972-190424

Petrescu, D. C., Vermeir, I., and Petrescu-Mag, R. M. (2020). Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: a cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:169. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010169

Pilon, C., Moore, P. A., Pote, D. H., Martin, J. W., and DeLaune, P. B. (2017). Effects of grazing management and buffer strips on metal runoff from pastures fertilized with poultry litter. J. Environ. Qual. 46, 402–410. doi: 10.2134/jeq2016.09.0379

Piochi, M., Fontefrancesco, M. F., and Torri, L. (2022). Understanding Italian consumers’ perception of safety in animal food products. Foods. 11:739. doi: 10.3390/foods11223739

Revoredo-Giha, C., Toma, L., Akaichi, F., and Dawson, I. (2022). Exploring the effects of increasing underutilized crops on consumers’ diets: the case of millet in Uganda. Agric. Food Econ. 10, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s40100-021-00206-3

Siegrist, M., Stampfli, N., and Kastenholz, H. (2008). Consumers’ willingness to buy functional foods. The influence of carrier, benefit and trust. Appetite 51, 526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.003

Tonkin, E., Wilson, A. M., Coveney, J., Webb, T., and Meyer, S. B. (2015). Trust in and through labelling – a systematic review and critique. Br. Food J. 117, 318–338. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2014-0244

Torri, L., Tuccillo, F., Alejandro Puente-Tapia, F., Carrara Morandini, A., Segovia, J., Nevarez-López, C. A., et al. (2024). Jellyfish as sustainable food source: a cross-cultural study among Latin American countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 117:105166. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2024.105166

Tregear, A., and Giraud, G. (2011). Geographical indications, consumers and citizens. Labels of origin for food: local development, global recognition. Wallingford: CAB International. doi: 10.1079/9781845933524.0063

Truong, V. A., Conroy, D. M., and Lang, B. (2021). The trust paradox in food labelling: an exploration of consumers’ perceptions of certified vegetables. Food Qual. Prefer. 93:104280. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104280

Van Loo, E. J., Hoefkens, C., and Verbeke, W. (2017). Healthy, sustainable and plant-based eating: perceived (mis)match and involvement-based consumer segments as targets for future policy. Food Policy 69, 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.03.001

Keywords: underutilized crops (UCs), food labeling, consumer perceptions, agrobiodiversity, sustainable food systems, willingness to buy

Citation: Bassignana CF, Bairati L, Bruno V and Torri L (2025) Consumers’ perceptions and attitudes toward a novel labeling framework for underutilized crops: a cross-national comparison. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1629395. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1629395

Edited by:

Amélia Delgado, University of Algarve, PortugalReviewed by:

Aiko Hibino, Hirosaki University, JapanGiulia Sesini, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Bassignana, Bairati, Bruno and Torri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luisa Torri, bC50b3JyaUB1bmlzZy5pdA==

Chiara Flora Bassignana

Chiara Flora Bassignana Lorenzo Bairati

Lorenzo Bairati Valentina Bruno

Valentina Bruno Luisa Torri

Luisa Torri