- 1African Centre for Food Security, School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences, College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

- 2Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Resource Management, School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences, College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

- 3Centre for Transformative Agricultural and Food Systems, School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences, College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

Introduction: Food insecurity remains a pressing challenge in developing nations, including South Africa, where many households depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. Integrating forestry emerging forestry commercial farmers into private sector investment frameworks offers potential to improve food security, yet empirical evidence on this relationship is limited. This study examines the relationship between private-sector investment interventions and food security outcomes among emerging forestry commercial farmers.

Methods: Using a quantitative design, data from 121 emerging forestry commercial farmers selected through simple random sampling analysis using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) and a parametric marginal treatment effects (MTEs) model with local instrumental variable (IV) estimation.

Results and discussion: Results showed that 97.5% of the sampled population experienced food insecurity, while only 2.5% demonstrated food security. For treated farmers, educational attainment and farm association membership were positively associated with improved food security, while for untreated farmers, training duration and satisfaction with training had similar positive effects. These findings highlight the role of education, collective organization, and effective training in reducing food insecurity among emerging forestry commercial farmers.

Conclusion: The study concludes that improving food security among emerging commercial farmers requires their greater inclusion in private sector strategic partnerships and recommends that extension officers adopt inclusive, participatory training approaches that accommodate farmers with limited literacy.

1 Introduction

Food security remains a pressing global challenge, particularly in developing countries where most of the population relies on agriculture for their livelihoods (Pawlak and Kołodziejczak, 2020). South Africa is among the developing countries that are affected by household vulnerability to food insecurity. A report by Statistics South Africa (2025) on food security revealed that in South Africa, household continue to experience challenges related to both moderate to severe and severe food insecurity. And attributes these challenges to “triple challenge” associated with poverty, inequality, and unemployment interrelated to socio-economic issues confronting the household food insecurity crisis in the country. While the objectives of the government’s food and nutrition strategies are to decrease food insecurity, hunger, and malnutrition, there are currently no coordinated implementation strategies for the food and nutrition security intervention programs in the country. This in turn affects the desired outcomes of these plans, which ideally are to contribute toward a nation that is food and nutrition secure.

According to Statistics South Africa (2025), out of almost 17.9 million households in SA in 2021, almost 15% (2.6 million) and 6% (1.1 million) stated that they had inadequate and severe inadequate access to food, respectively. Additionally, the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) (2024) revealed that 17.5% of households indicated severe food insecurity, 26.7% of households were moderately food insecure and 19.3% were mildly food insecure. This shows that South Africa is still facing challenges of high unemployment and prevalent poverty levels which further worsens food insecurity.

Evidence from literature showed that rural households are most affected by food insecurity (Galeana-Pizaña et al., 2021; Thanh et al., 2022). The rural household’s category includes emerging forestry commercial farmers who are engaged in agriculture primarily for profit through the sale of produce in formal markets. They typically have access to financial resources, whether through loans, government grants, or personal funds. According to Neves (2020), these farmers are commonly involved in the production of large-scale or bulk agricultural commodities. In contrast to small-scale farmers, who usually cultivate plots ranging from 0.1 to 20 hectares on land allocated through traditional authorities, emerging commercial farmers operating on farms larger than 20 hectares (Mnikathi et al., 2025). However, they often face constraints associated with limited resources, lack of market access, low levels of education, income inequality and insufficient government support (Khapayi and Celliers, 2016). These farmers play a significant role in improving food security through job creation, improved livelihoods and increased agricultural income (Giller et al., 2021).

The private sector is defined broadly as all non-state actors engaged in the agricultural economy for profit, ranging from smallholder entrepreneurs to large multinational agribusinesses, with key roles in production, processing, marketing, financing, and retail. This includes commercial farmers, agribusinesses, input suppliers, processors, retailers, private financiers, and service providers. The sector plays a central role in investment, innovation, and value chain development (Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, 2018). In this study, private sector strategic investment interventions are defined as investments made by businesses and individual investors aimed at promoting agricultural growth, reducing poverty, and improving quality of life. Private sector investment interventions can help improve the production and productivity of emerging forestry commercial farmers, thereby creating more livelihood opportunities. Private sector investment has emerged as a potential catalyst for agricultural development, aiming to empower farmers through access to capital, technology, and knowledge (Ensslin et al., 2022). These strategic interventions can take various forms, including direct investments, partnerships, and the provision of services that enhance productivity and provide opportunities for market access.

Despite the potential advantages of private sector investments in improving food security, little is known about how they really affect emerging forestry commercial farmers. Many forestry commercial farmers still encounter constraints that restrict their potential to benefit from the fruits of their investments. These constraints, as outlined by Khan et al. (2024) include poor infrastructure, restricted information availability, and susceptibility to market fluctuations. While it is clear that there are potential advantages associated with private sector investment interventions, it remains unclear how well these interventions work to advance sustainable agricultural practices. This is why understanding the effects of private sector investment on food security is essential for policymakers, investors, and other related stakeholders in the agricultural sector.

This suggests, therefore, an urgent need to assess how the different investment interventions can be best positioned to boost the capacity of emerging commercial farmers in general. One of the main interventions that can be used to bridge the gap between emerging farmers and larger markets is through the effective use the private sector resources, innovation, and efficiencies to fostering a more resilient agricultural sector (Manyise and Dentoni, 2021). However, the actual effects of such investments on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers remain underexplored, raising questions about their effectiveness and sustainability.

Existing literature reveals a notable gap in research examining the direct relationship between private sector strategic investment interventions and food security outcomes among emerging commercial farmers, particularly those involved in forestry production. While related studies exist, most focus broadly on smallholder farmers or other aspects of agricultural development. For instance, Raidimi and Kabiti (2017) explored public-private partnerships and extension services in food security; Simon (2012) analyzed private sector effects on rural livelihoods in Zimbabwe; and Gagné (2017) examined private agricultural investment in Senegal. Although valuable, these studies do not specifically investigate how private sector investments influence food security outcomes among emerging forestry commercial farmers in South Africa.

To address this gap, the present study investigates the link between private sector investment interventions and food security outcomes within this specific farming group. It aims to provide empirical evidence that can guide future investment strategies and inform policies promoting resilience and sustainability in the sector. Specifically, this study aims to assess the impact of private sector strategic investment interventions on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers in South Africa. The central research question guiding this investigation is: How do private sector strategic investment interventions influence the food security status of emerging forestry commercial farmers in KwaZulu Natal Province of South Africa?

2 Research methodology

2.1 Description of the study area

The study was conducted across six districts in KwaZulu-Natal province, characterized by progressive agricultural practices, with forestry and sugarcane production serving as substantial contributors to provincial economic output and employment generation. And the six regions were selected based on the presence of emerging forestry commercial farmers engaged in private-sector strategic investment intervention. The geographical scope encompassed Harry Gwala, uGu, Amajuba, uMgungundlovu, uMzinyathi, Zululand, and King Cetshwayo districts as illustrated in Figure 1. These districts were selected due to their significant concentration of emerging farmers involved in commercial forestry and timber production operations.

Figure 1. Map of the municipalities in KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, with all municipalities named and district municipalities shaded in different colors (2023).

The forestry sector demonstrated early recognition of the mutual advantages inherent in enterprise and supplier development initiatives, acknowledging that business sustainability necessitated strategic investment in emerging forestry commercial farmers in forestry (Forestry South Africa, 2021). The sector implemented an economic development program aimed at expanding the timber resource base and enhancing the availability of sustainable, competitively priced fiber for pulp and paper processing facilities. These strategic partnerships facilitated comprehensive enterprise development, encompassing access to inputs, technical support, extension services, financial assistance, and market linkages.

Commercial forestry plantations occupy approximately 1.26 million hectares nationally, with over 80% concentrated in Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Eastern Cape provinces (Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, 2018). The two dominant forest industry entities, Sappi and Mondi, maintain their primary operations in KwaZulu-Natal, with additional operational presence in Mpumalanga and the Eastern Cape. These enterprises lead the pulp and paper production sector, with their products primarily serving international markets. KwaZulu-Natal’s agricultural productivity is enhanced by annual precipitation exceeding 1,000 mm, predominantly during summer months, combined with fertile soil conditions that position agriculture as a central economic sector, which are conducive environmental factors for forestry production in South Africa.

The province is particularly suited for the cultivation of Eucalyptus spp. and Acacia spp., though Eucalyptus spp. represents the predominant plantation species in South Africa (Laubscher et al., 2022). The country’s primary timber processing facilities are strategically concentrated in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga (Forestry South Africa, 2021). The agricultural landscape of the province exhibits considerable diversity, reflecting the heterogeneous topographical characteristics of the region.

2.2 Sampling technique

The Department of Forestry and Fisheries in KwaZulu-Natal province was used to identify the emerging forestry commercial farmers. The provided data included the contact details of the emerging forestry commercial farmers contracted to the private sector. The selection of the emerging forestry commercial farmers was on the basis that, firstly, they had been in a strategic partnership investment intervention with the private sector for over 12 months. Secondly, within the same period, there has been some form of investment by a strategic partner, which also included receiving financial assistance and market access among other things.

2.3 Sample size

The sample size determination was calculated using the 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error based on the sampling frame of 250 emerging forestry commercial farmers, with each farmer having an equal chance of being selected. Only 135 emerging forestry commercial farmers met the selection criteria of having registered land ownership comprising of 20 ha farm size and being in a strategic investment intervention with the private sector. Participants were either the farm representative or the individual responsible for the farm’s overall management and operations.

2.4 Data collection technique

The study used a quantitative research method, and questionnaires were used to collect data across 8 of the 11 districts in KwaZulu-Natal. The questionnaire underwent pre-testing among non-participating emerging forestry commercial farmers before conducting actual testing on the farmers identified in the selection criteria. The pre-testing was crucial in refining the questionnaire and verifying the farmers’ understanding of their participation in the strategic intervention with the private sector and to comprehensively capture all necessary information. As the study aimed at gathering an accurate interpretation of practices of the participating emerging forestry commercial farmers in the forestry sector. The ethical considerations were equally considered, as informed consent and confidentiality were undertaken throughout the data collection.

A simple random sampling technique was used for a selection of participants. The sampling technique used ensured each participating member had an equal chance of being selected. This method is considered the most straightforward among probability sampling approaches (Pelser and Pelser, 2021; Hlatshwayo, 2022). Data collection of the emerging forestry commercial farmers was conducted through face-to-face interviews (Neves, 2020).

To enhance the respondent rate of understanding, the use of local language (isiZulu) was adopted to improve response. The research technique comprehended critical areas of the study objective related to participants’ demographic information, contract participation and capacity building, productivity inputs, marketing and credit access, income status, and food security indicators. The approach aided an extensive inspection of participants’ knowledge and perspective toward strategic partnership benefits, while also capturing farmers’ perceptions of success in their agricultural endeavors. This process allowed the researchers to get the participants’ understanding and their attitude toward partnership benefits. The process/method farmers’ perception of being successful.

3 Data analysis methods

Primary data from respondents were collected using Microsoft Excel and processed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and the STATA Version 15 statistical analysis software, where descriptive and econometric analyses were conducted. Descriptive statistics such as mean, percentage, frequency, and standard deviation were used to compute the socio-demographic variables of the sample under study.

3.1 Econometric analysis

The effects of private sector investment interventions on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers were analyzed using the Parametric Marginal Treatment Effects (MTE) model. The food security assessment used the internationally accepted food measurement tool: Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS).

The “access component of household food insecurity” was assessed using the HFIAS, considering the data supplied in a month (Coates et al., 2007). There are approximately nine questions on this scale that are based on a person’s anxiety and unpredictability about food access. A household’s consumption of high-quality food was the basis for the queries. The survey’s primary goal was to determine if respondents had experienced any difficulties getting food during the previous 30 days. The questions were broken down into three sections to illustrate the extent of food insecurity: question 1, poor quality (questions 2–4), and inadequate consumption (questions 5–9). The participants were asked to indicate if the scenario had happened infrequently or never (one or twice).

3.1.1 Parametric MTE model

Typically, the Marginal Treatment Effects model (MTE) with local Instrumental Variables (IV) is used to account for treatment effect heterogeneity as well as the unobserved dimension, also referred to as treatment resistance (Moler-Zapata et al., 2022). It is based on a potential outcomes model and a latent variable discrete choice model for selection into treatment (Heckman and Vytlacil, 2005, 2007; Brinch et al., 2017). This model links the unobserved heterogeneity in the treatment effect to the unobserved heterogeneity in the propensity to take the treatment. In other words, the treatment effect depends on each individual’s unobserved taste or distaste for treatment (resulting from a net benefit/cost of treatment). Following Andresen (2018), the MTEs model specification is based on the generalized Roy model. This is specified as:

Y₁ and Y₀ are the potential outcomes in the treated and untreated state; that is, farmers’ food security status with and without the treatment (adoption of private sector investment interventions), which are modeled as functions of observables and covariates. This, may have the possibility of fixed effects. Equation 3 represents the selection equation, which contains the latent index of I as an indicator function.

This also presents selection modeling into the treatment equation in an implicit form conditioned on the observable’s covariates and instruments Z, which does not influence potential outcomes but the probability of treatment.

The treatment selection process is modeled by an index threshold-crossing model that captures the latent net benefit of choosing the treatment (D*). It depends on observed determinants of selection into treatment (X, Z) (where Z is an instrument and is therefore excluded from the outcome), and on an unobserved component (V) such that:

Where denotes the propensity score given (X, Z) (i.e., the probability a farmer will receive treatment), with being the cumulative distribution function of , and (standard uniform distribution) and corresponds to different quantiles of , that is, here, the propensity not to be treated. The unobserved component is modeled as a negative shock that reduces the likelihood of treatment and can be interpreted as unobserved “resistance” (or “distaste”) to take treatment. The treatment assignment Equation 4 suggests that farmers choose to be treated whenever the propensity score exceeds the quantile of the distribution of V; in other words, whenever “observed encouragement” exceeds “unobserved resistance” to treatment (Cornelissen et al., 2016).

Given this framework, the marginal treatment effect is defined as the expected treatment effect conditional on covariates and unobserved resistance to treatment (Heckman and Vytlacil, 2007):

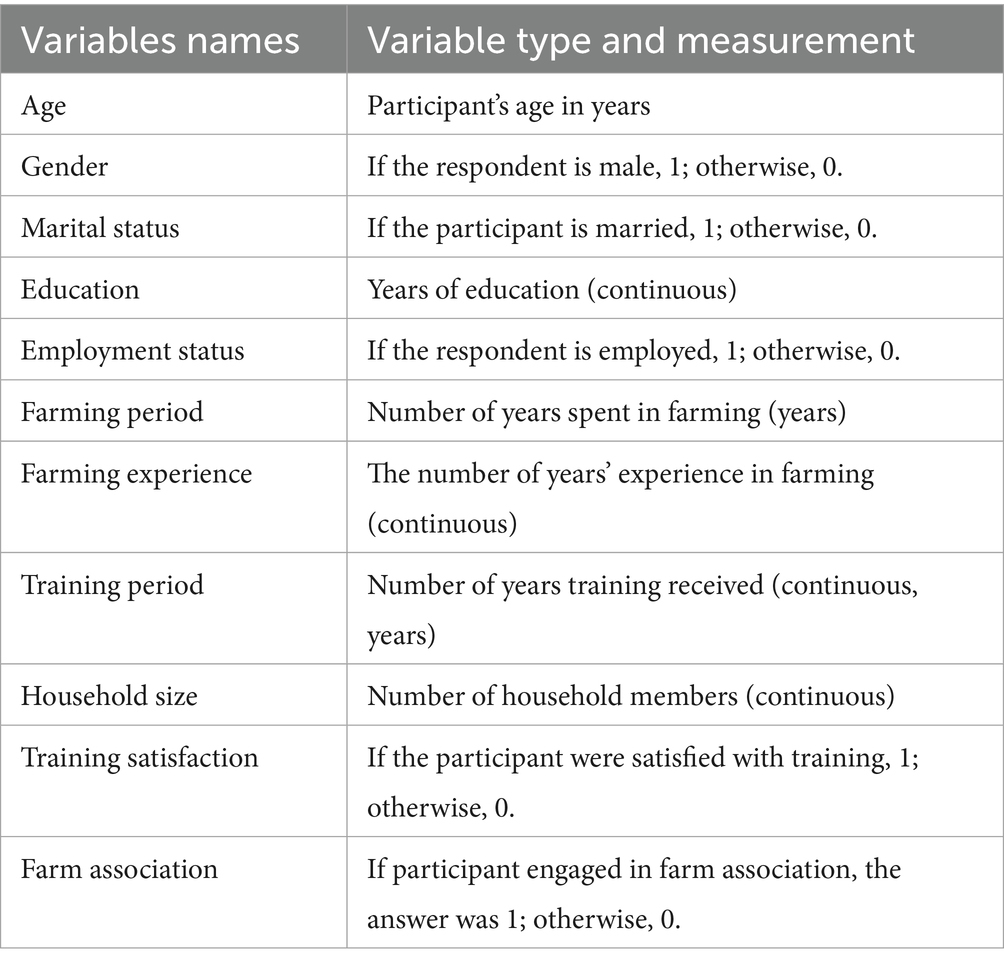

Where k(u) ≡ E(∪_1-∪_0\∪_D = u is the component of the treatment effect that varies across the unobserved resistance to treatment. The MTE function described by Equation 2 implies that the treatment effect for farmers with the same observed characteristics X = ₓ may differ if they experience different unobserved resistance to treatment ∪_D = u. For instance, given X, farmers with lower values of ∪_D are more likely to take treatment, regardless of the realization of Z. An MTE function that is declining in ∪ would therefore indicate that farmers who are more likely to choose D = 1 (in this application, to adopt private sector intervention) also experience larger gains in outcome Y from receiving the treatment (Mogstad and Torgovitsky, 2018). Table 1 represents the explanatory variable that affects adoption of private sector investment interventions.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Descriptive results

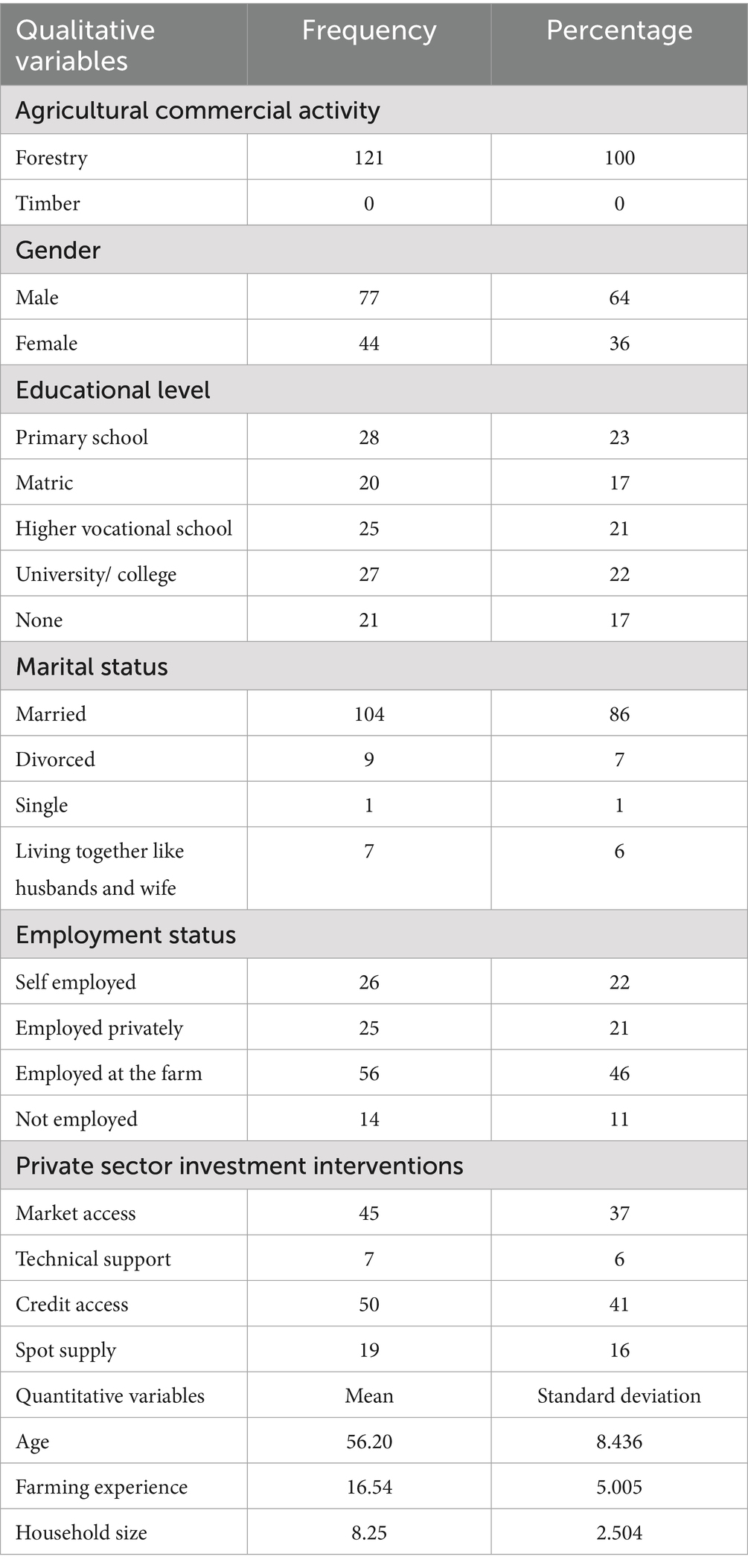

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of socio-demographic characteristics among the sampled emerging farmers (Mnikathi et al., 2025). The analysis indicates that all respondents (100%) were engaged in forestry production and were in strategic intervention with the private sector. The gender distribution revealed a predominance of male farmers (64%) compared to female farmers (36%), reflecting the typical gender composition in forestry farming in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

The demographic profile indicates a mean age of 56.20 years among respondents, with a significant majority (86%) reporting marital status as married, 7% as divorced, 6% living together like husband and wife, while only 1% identified as single. Educational attainment analysis revealed that 23% of respondents had completed primary education, 22% had attained tertiary education (university or college level), and 17% reported no formal education. This distribution indicates that approximately half of the sample population had received formal education.

Employment status analysis demonstrated that 46% of respondents were employed within their farming operations, while 11% reported unemployment. Regarding access to private sector investment interventions, the distribution was as follows: credit access (41%), market access (37%), and technical support (6%). The mean farming experience among respondents was 16.54 years, indicating substantial agricultural expertise within the sample population.

4.2 Occurrence of food insecurity by household characteristics based on HFIAS categories

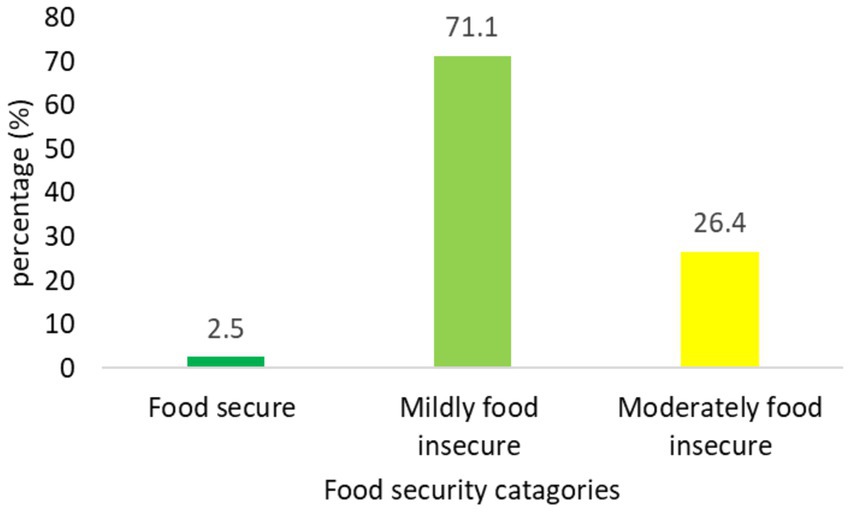

Figure 2 presents the status of household food insecurity among the sampled emerging forestry commercial farmers, as measured using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS). The HFIAS was chosen for this study because it is an experience-based tool that effectively captures both the behavioral and psychological dimensions of food insecurity within households. Specifically, it assesses the degree to which households face challenges in accessing sufficient, safe, and nutritious food, while also identifying changes in food security conditions over time (Masa and Sharma, 2015). The analysis of the full sample (n = 121) revealed that a significant majority (97.5%) of these emerging forestry commercial farmers, were experiencing a level of food insecurity, while only 2.5% were classified as food secure. This suggests that, despite their engagement in commercial agriculture, most farmers continue to struggle with consistent and adequate access to food, potentially undermining their health and productivity.

When examining the disaggregated categories of the HFIAS, it was found that 71.1% of the farmers’ households were classified as mildly food insecure, indicating occasional concerns about food availability and the quality of their diet. Meanwhile, 26.4% were moderately food insecure, showing more frequent compromises in food quality and quantity, including reductions in meal sizes or frequency. Interestingly, none of the households fell into the severely food insecure category, meaning there were no cases of farmers going entire days and nights without eating due to lack of food. Only the small minority (2.5%) were considered fully food secure, facing no significant challenges with food access.

This pattern deviates from findings in previous studies (Bhebhe et al., 2023; Ngidi, 2023; Gwacela et al., 2024; Shelembe et al., 2024), which reported a much higher prevalence of severe food insecurity among similar or comparable populations, including smallholder or emerging farmers. The absence of severe food insecurity in this study may suggest that while these farmers are far from being fully food secure, they might still have minimal access to some food sources, possibly through subsistence farming, informal markets, or social networks. Alternatively, it could reflect underreporting or seasonal variation in food access during the survey period.

4.3 The impact of private sector investment interventions on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers

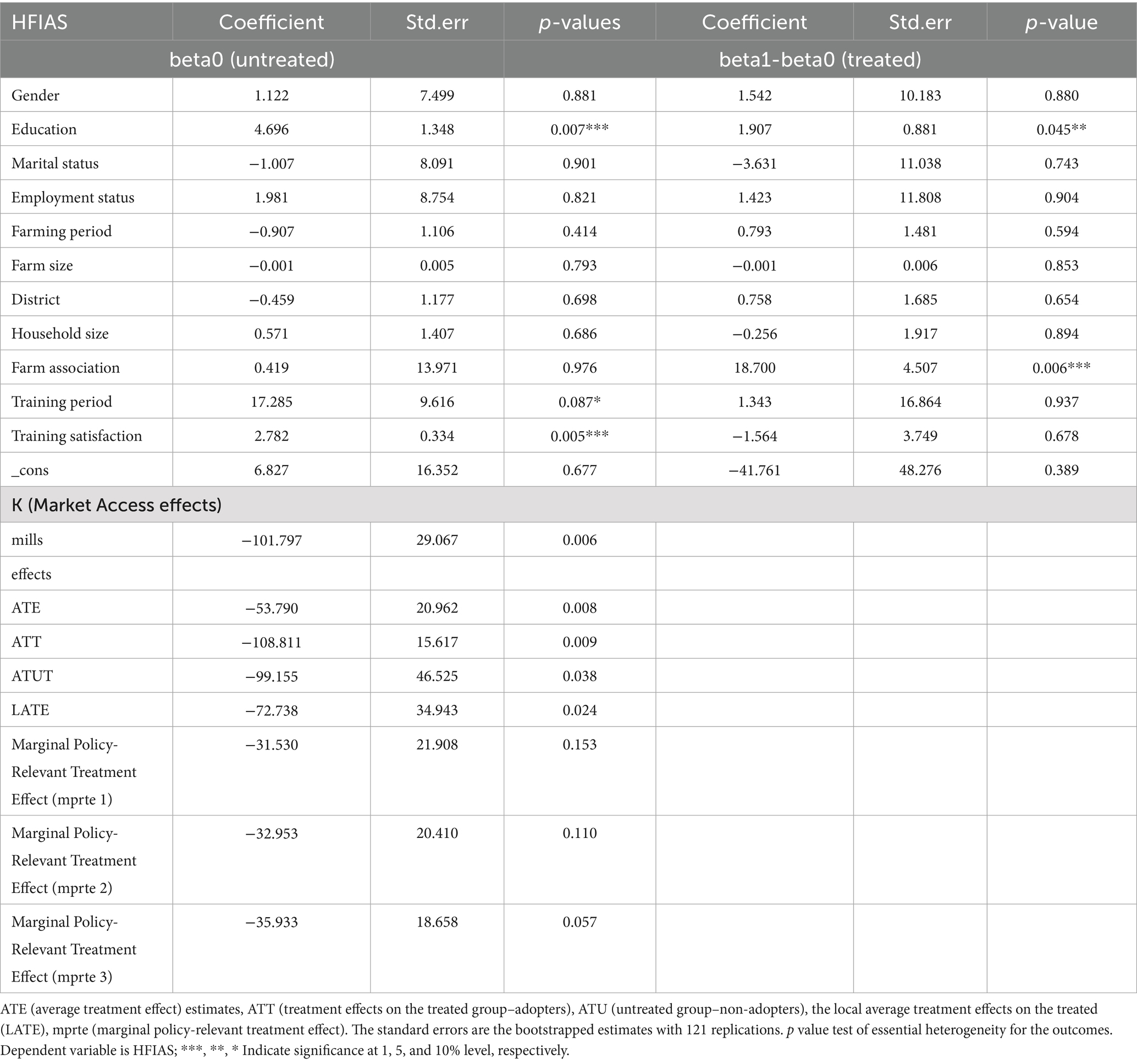

The MTE model estimation was fitted through local IV and separate approach estimators regarding parametric assumptions. However, the local IV was favored due to the model’s performance. The output from this estimation, as shown in Table 3, highlights the impact of private sector investment interventions on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers. Likewise, the differences in the average outcomes across the fitted covariates could be inferred directly from the first panel of the output as indicated by β₀ (untreated). However, there is a need to account for the strong exogeneity assumption, which is required on the fitted covariates. Therefore, the second panel of the output with β₁— β₀ (treated) in Table 3 explains the observed differences in treatment effects across covariate values, which also indicates treatment status and covariate interactions. Also, since the dependent variable, HFIAS, increases with food insecurity severity, positive coefficients indicate the possibility of more severe food insecurities, and negative coefficients indicate otherwise. The dependent variable is HFIAS presented as follows in the table ***, **, *. Indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10% level, respectively.

Table 3. Determine the impact of private sector strategic investment interventions on the food security of emerging forestry commercial farmers_parametric normal MTE model.

For the untreated farmers, the results showed that the training period and training satisfaction are positively and significantly influenced HFIAS. This means that as the training period increases, the food insecurity status of farmers increases. The possible explanation can be that farmers do not receive adequate training as the number of years increases. This also led them to be dissatisfied with the training that they were receiving and negatively affected their food security status. However, the results were not statistically significant on the treated farmers, which means that it is difficult to confidently infer that it is the actual effects of the training period and training satisfaction that increased food insecurity if the exogeneity assumption is not observed as required on the fitted covariates. Many factors affect emerging farmers; therefore, it is important to account for the strong exogeneity assumption (Olawuyi and Mushunje, 2019).

The results showed that education positively and significantly influences HFIAS of treated and untreated farmers. This means that by holding other factors constant, the educational status of farmers leads to increased food insecurity. This could be attributed to the fact that most of the farmers in this study had primary schooling; therefore, they did not have much knowledge on the adoption of the private sector investment interventions associated with modern commercial forestry, which will improve their food security status. When involved in commercial forestry farmers need to adopt modern forestry practices to achieve sustainable yields from their timber. Emerging forestry commercial farmers must have knowledge to comprehend adopted technology and modern forest management practices to improve mean annual increment. The results were in line with Kara and Kithu (2020), who found that the household heads who had attained primary education and those who had attained secondary education were food insecure and experienced hunger. The authors clarified that this was caused by a lack of knowledge about professions and employment opportunities, a lack of funds to start a business, a skills mismatch that hindered the transfer from education to income, and negative views toward agricultural and informal employment. However, the results were contrary to Mutisya et al. (2016) who found that the probability of being food insecure decreased by an increase in the average years of schooling for a given household.

The results revealed that the farm association has a positive and significant influence on the food insecurity situation of treated emerging farmers. This means that, holding other factors constant, the involvement of emerging farmers in the in-farm association led to increase in their food insecurity status. The results imply that farmers who participated in farmers’ associations did not adopt private sector investment interventions, which affected their food security status. The results contradicted the findings of Nugusse et al. (2013), who found that cooperative societies were key determinants of household food security in the study areas. The authors justified that the expansion of cooperative societies was an important tool to minimize the food insecurity problem in the country. Gebremichael (2014) also reported that being a member of a farm association contributed significantly toward improving the standards of living of the rural residents, enabling them to participate in various economic activities, which helped in the promotion of food security.

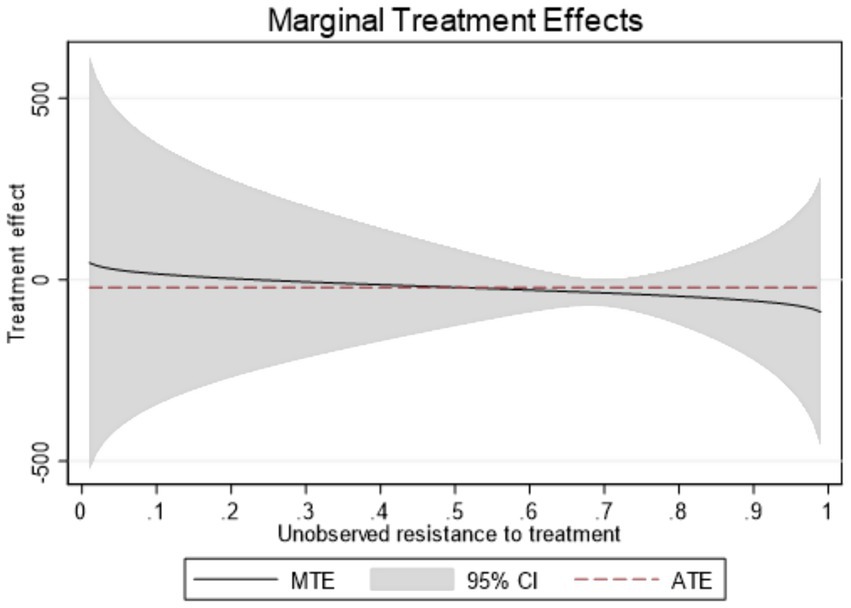

4.4 The MTE curve plot

For the parametric joint normal assumption using local IV, Figure 3 shows the MTE curve plot, as well as the associated confidence intervals for the treated and untreated farmers. This will permit making necessary inferences about the common support. In this case, the downward sloping of the estimated MTE plot is observed, with relatively high treatment effects at the beginning of the UD distribution (addressing propensity not to be treated), which eventually declines to negative effects at the right end of the distribution. This pattern of slope (downward) is in tandem with the Roy model, which predicts a positive selection on unobservable benefits. The results show that farmers who are most inclined/least resistant to adopt private sector investment interventions (those with low values of UD) had high food security, positive marginal treatment effects. By contrast, farmers with particularly high values of UD who are most reluctant to adopt private sector investment interventions showed negative values, indicating that they had high food insecurity.

Figure 3. Marginal treatment effects plot for joint normal assumption computed through Stata version 18.

5 Conclusions and policy recommendations

The integration of emerging forestry commercial farmers into private-sector investment interventions represents a strategic approach for enhancing both agricultural development capacity and household food security outcomes. This investigation aimed to examine the relationship between private sector strategic investment interventions and food security status among emerging forestry commercial farmers. A notable empirical finding was the absence of severe food insecurity cases within the sampled emerging forestry commercial farmers. Statistical analyses revealed that educational attainment and agricultural association membership exhibited positive and statistically significant relationships with food insecurity status among participants who received interventions (treated farmers). For non-intervention participants (untreated farmers), both the duration of the training program and reported satisfaction with training initiatives demonstrated positive and significant associations with food insecurity status. The findings suggest that insufficient formal education, limited participation in farm associations, and inadequate training contribute substantially to food insecurity among emerging forestry commercial farmers.

The research indicates that the adoption of private-sector strategic intervention is associated with food security outcomes. Therefore, the study concludes that integrating emerging commercial farmers into private-sector strategic interventions will likely improve their food security status. The process will likely improve impactful modern technology access to improve emerging farmers’ scale of productivity and market access, which are essential for food security status. Therefore, harnessing the growth of a sustainable economy, building capabilities, and comprehensive and sustainable strategic partnerships for emerging farmers in KwaZulu-Natal and South Africa in general.

Furthermore, Policymakers and stakeholders should prioritize formalizing strategic partnerships with the private sector to have sustainable market-integrated initiatives that formally incorporate emerging commercial farmers into formal and profitable markets. The integration will assist farmers to access the value chain, participating in improving their income opportunities and sustainable forestry and agricultural practices. Investing in the education and training of farmers can lead to better agricultural and financial management practices and productivity diversification, which can possibly contribute to improved food security.

5.1 Limitations

The study is based on data collected in the KZN province of South Africa and may not be applicable as a general representation of emerging forestry commercial farmers on a national and international scale. There is a need for similar studies to be conducted across all nine provinces of South Africa. The study used quantitative research to identify correlations, which often reduces complex social phenomena to numerical data. The limitations of this research method are that it potentially loses the richness and complexity of the real-world situations, and its findings may not be easily transferable to other populations or contexts, especially if the sample is not representative of the broader audience. This study specifically examined the impact of private sector strategic interventions on emerging forestry commercial farmers; however, future research could expand to include other types of farmers, such as smallholder and subsistence farmers. Additionally, this study focused on a single food security indicator, the HFIAS. The study proposes that future studies should incorporate the nutritional aspects of food security as well.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the UKZN Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee HSSREC/00005928/2023. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM: Writing – original draft. SH: Writing – review & editing. MN: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andresen, M. E. (2018). Exploring marginal treatment effects: flexible estimation using Stata. Stata J. 18, 118–158. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1801800108

Bhebhe, Q. N., Ngidi, M. S., Siwela, M., Ojo, T. O., Hlatshwayo, S. I., and Mabhaudhi, T. (2023). The contribution of trees and green spaces to household food security in eThekwini metro, Kwa Zulu-Natal. Sustainability 15:4855. doi: 10.3390/su15064855

Brinch, C., Mogstad, M., and Wiswall, M. (2017). Beyond LATE with a discrete instrument. J. Polit. Econ. 125, 985–1037. doi: 10.1086/692712

Coates, J., Swindale, A., and Bilinsky, P. (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide: version 3. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project Academy for Educational Development.

Cornelissen, T., Dustmann, C., Raute, A., and Schönberg, U. (2016). From LATE to MTE: alternative methods for the evaluation of policy interventions. Labour Econ. 41, 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.004

Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries (2018). State of the forests report. South Africa department of forestry, fisheries, and the environment. Canberra, ACT: Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries.

Ensslin, S. R., Welter, L. M., and Pedersini, D. R. (2022). Performance evaluation: a comparative study between public and private sectors. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 71, 1761–1785. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-04-2020-0146

Forestry South Africa (2021). Corporate social Investments CSI narrative 2021 corporate social investment. South Africa: Forestry South Africa.

Gagné, M. (2017). Is private investment in agriculture the solution? An evaluation of the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Senegal. Washington, DC: Food Security Policy Group.

Galeana-Pizaña, J. M., Couturier, S., Figueroa, D., and Jiménez, A. D. (2021). Is rural food security primarily associated with smallholder agriculture or with commercial agriculture? An approach to the case of Mexico using structural equation modeling. Agric. Syst. 190:103091. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103091

Gebremichael, B. A. (2014). The role of agricultural cooperatives in promoting food security and rural women’s empowerment in eastern Tigray region, Ethiopia. Dev. Country Stud. 4, 96–109.

Giller, K. E., Delaune, T., Silva, J. V., Descheemaeker, K., van de Ven, G., Schut, A. G., et al. (2021). The future of farming: who will produce our food? Food Secur. 13, 1073–1099. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01184-6

Gwacela, M., Ngidi, M. S. C., Hlatshwayo, S. I., and Ojo, T. O. (2024). Analysis of the contribution of home gardens to household food security in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Sustainability 16:2525. doi: 10.3390/su16062525

Heckman, J. J., and Vytlacil, E. (2005). Structural equations, treatment effects, and econometric policy evaluation 1. Econometrica 73, 669–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00594.x

Heckman, J. J., and Vytlacil, E. J. (2007). Econometric evaluation of social programs, part II: Using the marginal treatment effect to organize alternative econometric estimators to evaluate social programs, and to forecast their effects in new environments. Handbook Econom. 6, 4875–5143. doi: 10.1016/s1573-4412(07)06071-0

Hlatshwayo, S. I. (2022). Impact of Crop Productivity and Market Participation on Rural Households’ Food and Nutrition Security Status: The Case of Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces, South Africa. Available at: https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/21711 (accessed 08/2024).

Kara, A. M., and Kithu, L. M. (2020). Education attainment of head of household and household food security: a case for Yatta Sub-County, Kenya. Am. J. Educ. Res. 8, 558–566. doi: 10.12691/education-8-8-7

Khan, F. U., Nouman, M., Negrut, L., Abban, J., Cismas, L. M., and Siddiqi, M. F. (2024). Constraints to agricultural finance in underdeveloped and developing countries: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 22:2329388. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2024.2329388

Khapayi, M., and Celliers, P. R. (2016). Factors limiting and preventing emerging farmers to progress to commercial agricultural farming in the king William’s town area of the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 44, 25–41. doi: 10.17159/2413-3221/2016/v44n1a374

Laubscher, J. M., Bekker, J., and Ackerman, S. (2022). Base models for simulating the South African forestry supply chain. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 33, 47–59. doi: 10.7166/33-4-2732

Manyise, T., and Dentoni, D. (2021). Value chain partnerships and farmer entrepreneurship as balancing ecosystem services: implications for Agri-food systems resilience. Ecosystem Serv. 49:101279. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101279

Masa, R., and Sharma, A. (2015). Invariance of the household food insecurity access scale across different groups of adolescents and young adults. Food Nutr. Bull. 42, 437–450. doi: 10.1177/03795721211019634

Mnikathi, S. J., Hlatshwayo, S. I., Temitope, O., and Ngidi, M. S. C. (2025). Participation of emerging commercial farmers in the strategic private-sector investment interventions. Agriculture 15:450. doi: 10.3390/agriculture15050450

Mogstad, M., and Torgovitsky, A. (2018). Identification and extrapolation of causal effects with instrumental variables. Annu. Rev. Econ. 10, 577–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-101617-041813

Moler-Zapata, S., Grieve, R., Basu, A., and O’Neill, S. (2022). How does a local instrumental variable method perform across settings with instruments of differing strengths? A simulation study and an evaluation of emergency surgery. Available online at: http://www.york.ac.uk/economics/postgrad/herc/hedg/wps/ (accessed June 6, 2025).

Mutisya, M., Ngware, M. W., Kabiru, C. W., and Kandala, N. B. (2016). The effect of education on household food security in two informal urban settlements in Kenya: a longitudinal analysis. Food Secur. 8, 743–756. doi: 10.1007/s12571-016-0589-3

Neves, D. (2020). Thematic study: agricultural value chains in south africa and the implications for employment-intensive land reform. Bellville, South Africa: University of The Western Cape.

Ngidi, M. S. C. (2023). The role of traditional leafy vegetables on household food security in Umdoni municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Foods 12:3918. doi: 10.3390/foods12213918

Nugusse, W. Z., Van Huylenbroeck, G., and Buysse, J. (2013). Household food security through cooperatives in northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Coop. Stud. 2, 34–45. doi: 10.11634/216826311302299

Olawuyi, S. O., and Mushunje, A. (2019). Social capital and adoption of alternative conservation agricultural practices in South-Western Nigeria. Sustainability 11:66. doi: 10.3390/su11030716

Pawlak, K., and Kołodziejczak, M. (2020). The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability 12:5488. doi: 10.3390/su12135488

Pelser, A. S., and Pelser, T. (2021). The analysing factors that contribute to the growth of emerging farmers in the agricultural sector, Northwest Province South Africa. Proceedings of the 14th International Business Conference (Virtual), South Africa, 20–21.

Raidimi, E. N., and Kabiti, H. M. (2017). Agricultural extension, research, and development for increased food security: the need for public-private sector partnerships in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 45, 49–63. doi: 10.17159/2413-3221/2017/v45n1a414

Simon, M., (2012). Welfare impact of private sector interventions on rural livelihoods: the case of Masvingo and Chiredzi smallholder farmers. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 10, 3–9.

Shelembe, N., Hlatshwayo, S. I., Modi, A., Mabhaudhi, T., and Ngidi, M. S. C. (2024). The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Agriculture, 14, 415. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14030415e.net/10520/ejc-indeng_v33_n4_a5

Statistics South Africa (2025). Food Security in South Africa in 2019, 2022 and 2023: Evidence from the General Household Survey/Statistics South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

Keywords: food security, food insecurity, private sector, strategic intervention, parametric marginal treatment effects, emerging forestry commercial farmers

Citation: Mnikathi SJ, Hlatshwayo SI and Ngidi MSC (2025) Analyzing the relationship between private sector strategic investment interventions and food security outcomes of emerging forestry commercial farmers. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1644072. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1644072

Edited by:

Justice Gameli Djokoto, Dominion University College, GhanaReviewed by:

Zenzile Peter Khetsha, Central University of Technology, South AfricaPunlork Men, National Institute of Science, Technology, and Innovation (NISTI), MISTI, Cambodia

Tesfalegn Yonas, Wachemo University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 Mnikathi, Hlatshwayo and Ngidi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. J. Mnikathi, MjAxNTA0MjE4QHN0dS51a3puLmFjLnph; M. S. C. Ngidi, bmdpZGltQHVrem4uYWMuemE=

S. J. Mnikathi

S. J. Mnikathi S. I. Hlatshwayo

S. I. Hlatshwayo M. S. C. Ngidi

M. S. C. Ngidi