- 1School of Economics, Lanzhou University of Finance and Economics, Lanzhou, Lanzhou, China

- 2School of Public Administration, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, Xi’an, China

To reduce the threat of natural disasters and promote human well-being, Shaanxi Province, China, relocated 2.4 million people from three cities in the south in 2011. As the largest disaster resettlement project ever implemented in China, its scale, investment, extent, and impact deserve the continuous attention of policy researchers and practitioners. The impact of this project on rural-scale livelihoods and well-being especially needs more empirical evidence and comprehensive assessment. This article refers to the MA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) indicator system to measure the sustainable household well-being (SHWB) of disaster resettlement households using survey data from Southern Shaanxi, China. To explore the determinants of the SHWB of disaster resettlement households, this paper employs a quantile regression model for analysis. The results show that, compared to voluntary relocation households, long-distance relocation households, and medium or short-term relocation households, the SHWB of involuntary relocation households, short-distance relocation households, and long-term relocation households, respectively, is not only significantly higher, but also fluctuates greatly. In addition, voluntary relocation has a significant negative impact on SHWB, while short-distance relocation and medium and long-term relocation have a significant positive impact on SHWB. Furthermore, the education level of household members demonstrates a significant positive impact on SHWB. These findings have extensive implications for disaster resettlement and management in China and other developing nations. They are critical to improving the quality of farmers’ livelihoods and promoting sustainable well-being for rural households.

1 Introduction

Climate change, environmental degradation, and severe natural disasters are occurring globally, creating dilemmas and challenges for human beings in terms of economy, resources, and living environment (Zhang et al., 2022). Resettlement constitutes a comprehensive social intervention encompassing population displacement, spatial relocation, and socio-economic restructuring. It denotes the process by which residents, motivated by a variety of factors, relocate in an orderly fashion from their original residences to new settlements. Among the various forms of resettlement, disaster resettlement—a targeted intervention primarily aimed at reducing disaster risk and advancing environmental protection and regional poverty alleviation—constitutes a pivotal instrument for global disaster risk reduction and mitigation, as well as regional sustainable development. While displacing and relocating residents should be a last resort (Tang et al., 2022), there has been an increase in resettlement programs (Barua et al., 2017; Manatunge and Abeysinghe, 2017). There are many reasons for governments to relocate residents (Vanclay, 2017), from alleviating poverty (Lo and Wang, 2018) to responding to natural disasters (Khattri, 2021) and protecting the environment (See and Wilmsen, 2020). For example, the Chinese government has promoted an urban migration model to alleviate ecological poverty in regions (Guo et al., 2022). There are also regions where ecosystems have been destroyed, leading to ecological or environmental resettlement (Chen and Tsai, 2021). In addition, development is an important cause of displacement and resettlement, such as resettlement in the Three Gorges Dam area in China (Hwang et al., 2011; Wilmsen et al., 2011; Tilt and Gerkey, 2016). At present, many studies have made significant contributions to understanding the impact of development-induced resettlement on social ecology and population economics (Reddy, 2018; Liu et al., 2019). Similarly, many demographic and ecological studies related to disaster resettlement have been conducted globally for rebuilding the livelihoods and improving the well-being of resettled people (Barua et al., 2017; Guo and Kapucu, 2018). In fact, the livelihood perspective provides a central entry point for analyzing the sustainability of disaster resettlement. The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) proposed by DFID posits that farm household livelihoods depend on the allocation and transformation of five forms of capital: natural, physical, financial, human, and social. Disaster resettlement essentially involves the restructuring of livelihood capital under external intervention (Scoones, 1998; DFID, 2000; Ellis, 2000). As participants and key stakeholders in disaster resettlement, farm households’ livelihood choices are directly modified by this capital restructuring, which in turn prompts adjustments to their livelihood strategies and practices and ultimately enhances their well-being and the sustainable development of their households. As a result, this paper shows on farm household survey data, focusing on rural well-being and the process of livelihood transformation. It helps to contribute theoretically to the analysis of the mechanisms by which disaster resettlement affects household well-being from the perspective of sustainable livelihoods, thus enriching and deepening the literature on community livelihoods in the context of disaster resettlement.

Disaster resettlement program has become an important way for countries around the world to improve the livelihoods and well-being of affected farmers (Chen et al., 2017; Galarza-Villamar et al., 2018; Savari and Shokati Amghani, 2022). The largest disaster resettlement project in contemporary China was started in 2011 by Shaanxi Province as part of a disaster avoidance and preparedness initiative (Li et al., 2015). There are differences in the relocation characteristics of the relocated households. According to nature, distance, and time of relocation, relocated households are divided into voluntary, involuntary, short-distance, long-distance, short-term, medium-term, and long-term relocation households (Liu et al., 2024). Previous studies have empirically examined the impacts of this project on household livelihoods. For instance, Li et al. (2018) argued that relocation and settlement programs (RSP) generally achieve the goals of increasing ecosystem services and restoring livelihoods (Li et al., 2018). Liu and Wu (2023) proposed that resettlement can successfully lessen household’s reliance on local natural resources, leading to ecological improvement (Liu and Wu, 2023). Similarly, Li et al. (2021) explored that relocated families are closer to achieving the “high well-being, low dependency” mode (Li et al., 2021). Guo et al. (2023) argued that family capabilities and empowerment are effective ways to ensuring integration, and that follow-up support measures can help to improve those elements (Guo et al., 2023). Further, they also analyze the complexity of disaster resettlement integration, highlighting how resettled households can strategically move between rural and urban areas in the face of rapid change (Guo et al., 2024). It is noticeable that sometimes disaster resettlement policies negatively affect farmers’ livelihoods (Rogers and Xue, 2015; Khan et al., 2022). For example, Liu et al. (2020b) concluded that disaster resettlement significantly reduces the resilience of household livelihoods, while Xu et al. (2022) also believe that disaster resettlement policies reduce the adaptability of farmers and have a significant negative impact on their adaptability (Liu et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2022).

Farmers’ livelihoods and well-being have a profound impact on sustainable development in poor and resource-dependent regions (Liu et al., 2020a; Defe and Matsa, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to study the impact of disaster resettlement on rural household’s well-being. A few studies have analyzed the impact of government-led disaster resettlement programs on the livelihoods of affected groups by examining and quantifying the well-being of rural households (Li et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2024). Following the designs and ideas, this study attempts to add empirical evidence related to the impacts of disaster resettlement.

Improving the quality of life of disaster resettlement farmers requires first understanding the connection between farmer well-being and disaster resettlement (Sina et al., 2019). In order to clarify and interpret the household well-being of disaster resettlement farmers, it is necessary to understand and grasp the concept and dimension of well-being more accurately. Well-being is a subjective expression of an individual’s current situation and satisfaction degree, which reflects an individual’s cognition and emotion toward their current overall quality of life (Li et al., 2013). It is a broad idea, and therefore, it is critical to examine its variants and determine the appropriate metrics (King et al., 2014). Numerous studies have shown that well-being is multi-dimensional, so the indicators selected are different with different research contents (Wang and Tang, 2016; Qiu et al., 2021). For example, Kassouri et al. (2020) conducted a study using subjective and objective dimensions as indicators of well-being (Kassouri and Altintas, 2020). Subjective well-being and objective well-being have received more attention in many research domains (Fang et al., 2024). In practice, a wide range of frameworks, metrics, and techniques have been employed to examine rural household’s well-being (Fulford et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023).

As mentioned earlier, Li et al. (2021) developed a coupled model of “household well-being and ecosystem dependence” in rural China that offers fresh perspectives regarding the connection between ecosystem services (ES) and household well-being (Li et al., 2021). In recent years, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) (2005) issued by the relevant United Nations agencies has received extensive attention from scholars. The report recognizes five dimensions of human well-being: “basic material needs for a good life, health, social relation, security, and freedom of choice and action” (Assessment, 2005). Peng et al. (2022) developed the Sustainable Household Well-Being (SHWB) Index based on the principles presented in this report (Peng et al., 2022). The SHWB index takes into account five dimensions of human well-being identified in the report. It provides a comprehensive perspective for measuring household well-being and can more fully reflect the overall well-being of household members in the social environment. The index provides a better measure of household well-being at the perimeter scale and integrates sustainable household livelihoods. The above literature provided us with a rich basis for the present study. Considering the above measures of well-being and the reality of the study area, this paper carefully constructed a set of indicators of the SHWB in the context of disaster resettlement, then quantified and measured them.

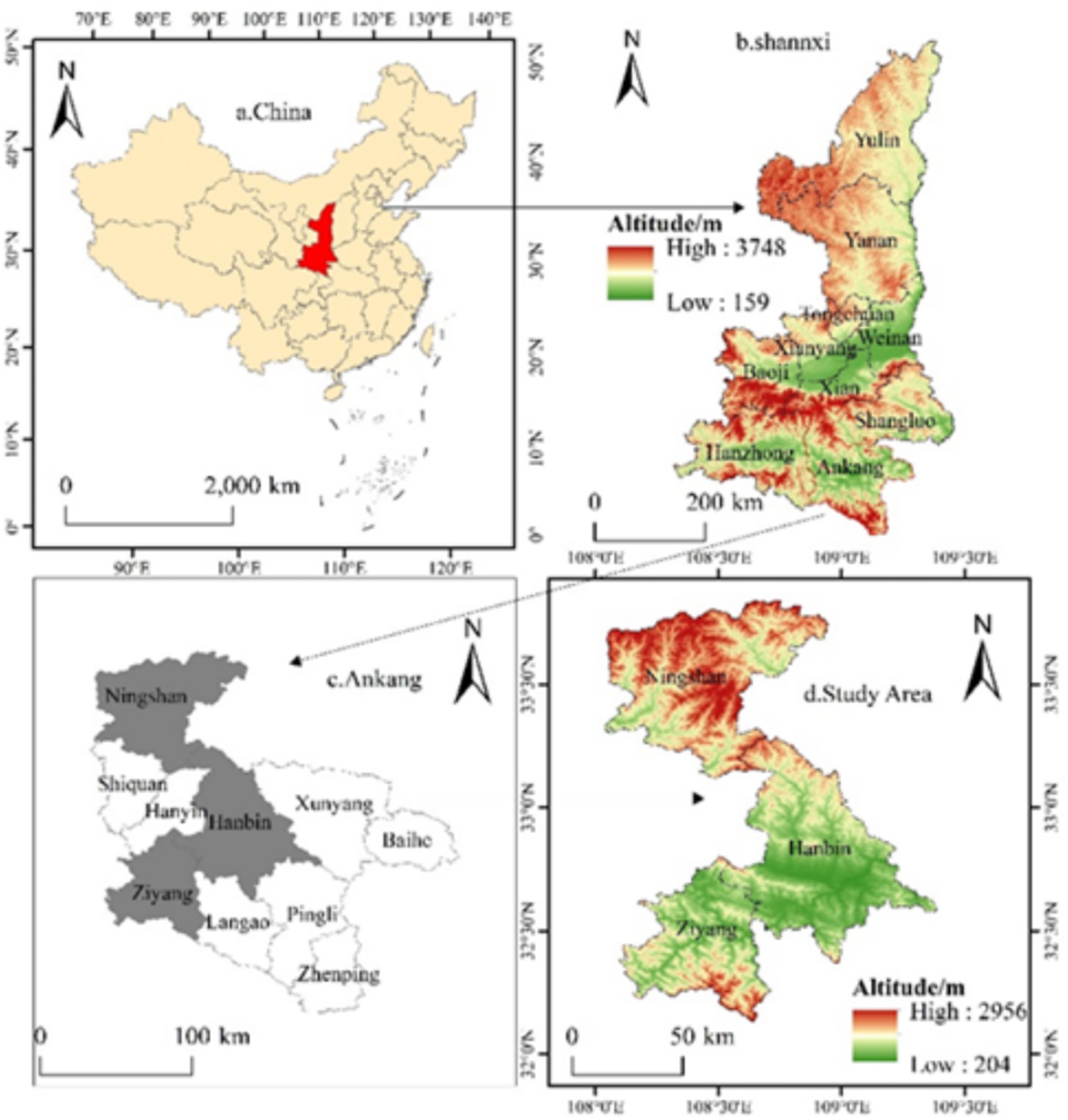

This paper focuses on the Ankang Prefecture in southern Shaanxi Province, China, one of the main areas in which the Shaanxi Provincial Government has carried out the “Disaster Shelter and Resettlement” program for disaster mitigation and preparedness. The massive scale of migration and dramatic changes in the living environment are bound to have far-reaching impacts on farmers, and coupled with the objective constraints of capital, land, etc., some of the relocated farmers will fall into new difficulties (Guo et al., 2022; UN-ILibrary, 2025). Therefore, the level of well-being as well as the sustainability of the relocated rural families in the region needs to be looked at.

The primary objective of this study is to supply a systematic analysis of the subjective well-being (SHWB) of disaster-resettlement households, addressing the following aspects: (1) Drawing on the methodological framework proposed by Peng et al. (2022) and constructing an SHWB indicator system based on five dimensions, with reference to MA (2005), (2) Subsequently, we use principal component analysis to derive the weights of the indicators used to measure SHWB, and we apply a quantile regression method to calculate the determinants of SHWB among disaster-resettlement households, (3) this study compares SHWB levels across distinct resettlement characteristics and describe the density distribution of SHWB among different forms of resettled farmers. In addition, we apply a t-test to assess whether there are significant differences between relocation households (RHhs) with dissimilar relocation timings and types.

Next, this paper discusses the limitations of our study. The results may be more accurate if the analysis can be combined with different methods to determine the weights. Further improvements with more advanced statistical models cannot be ruled out. Future studies could also delve deeper into relocation policies from different contexts for a wider discussion. This paper then presents its conclusions. The scope of this research is specified as follows: (1) This paper measures and compares the sustainable well-being levels of farmers with different relocation characteristics and discusses the influencing factors of farmers’ sustainable well-being, which constitutes a significant analytical content for sustainable household well-being (SHWB) research at the rural household level (2) The disaster resettlement area in southern Shaanxi is taken as the research area of this paper, and the results show an expansive range of reference scope for disaster resettlement and management in Chinese rural areas and other low- and middle-income countries. This study helps to solve the following two essential questions: (1) How does disaster resettlement contribute to examine applicability of the Sustainable Household Well-being (SHWB)? (2) How does using the SHWB, rather than indicators such as poverty, income, capital endowment, or resource dependence, help characterize the livelihood status of farmers in disaster resettlement contexts?

2 Theoretical framework

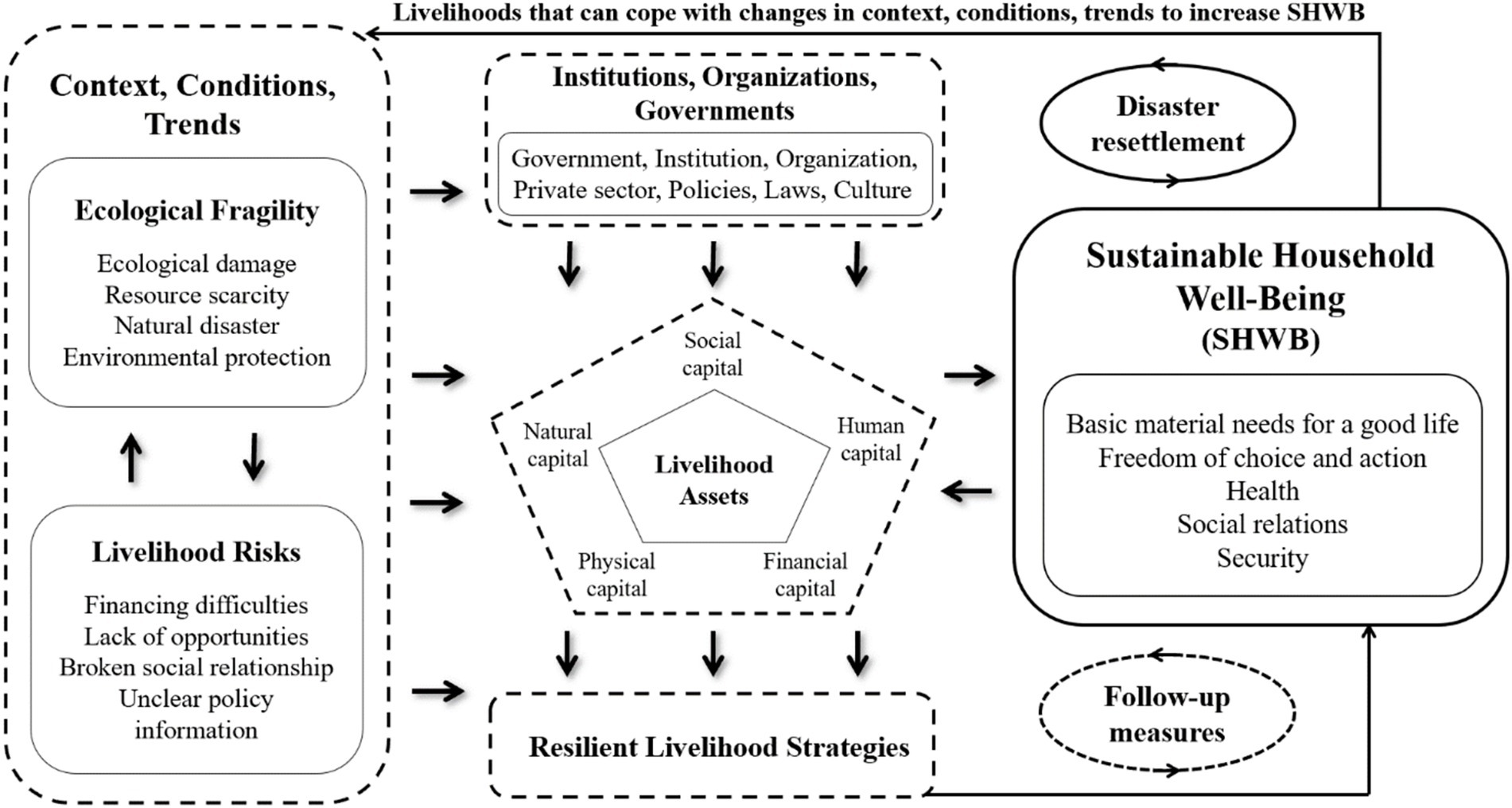

Disaster resettlement composes a strategic intervention designed to solve the developmental constraints arising from the interaction between ecological fragility and livelihood risk. Drawing on the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) proposed by the Department for International Development (DFID) in 1999, and building on the analyses of Liu et al. (2020a, 2020b) and Li et al. (2021), we identify two primary mediating pathways through which resettlement affects sustainable household well-being (SHWB): (1) the acquisition of livelihood assets facilitated by institutional, organizational, and governmental frameworks; and (2) the adoption of resilient livelihood strategies. Within this framework (Figure 1), institutions, organizations, and governments play as central catalysts for asset acquisition, encompassing a range of components—including government bodies, agencies, the private sector, policies, regulations, and cultural norms—that collectively establish the rules and enabling environments enabling households to access essential capital. Livelihood assets, comprising natural, social, human, financial, and physical capital, constitute the fundamental resources upon which households base their productive activities and daily subsistence, and are essential for sustaining livelihoods and increasing well-being. The role of institutions, organizations, and governments in facilitating asset acquisition, thus making households able to develop and pursue resilient livelihood strategies. Concurrently, disaster resettlement, as a vital external shock, may exert a direct influence on processes such as asset acquisition.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework for analyzing the impact of Disaster Resettlement on Sustainable Household Well-Being (SHWB).

Sustainable household well-being is conceptualized as a multidimensional construction that encompasses the satisfaction of basic material requirements for a decent standard of living, freedom to choice and action, health status, positive social relations, and security. The adoption of resilient livelihood strategies, together with subsequent adaptive measures, contributes to sustainable household well-being. Moreover, sustainable household well-being increases a household’s capacity to respond to contextual shifts, conditional fluctuations, and evolving trends, thereby generating a feedback loop that fosters ongoing household development.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area and data source

Ankang Prefecture in Southern Shaanxi Province (Figure 2) is situated in the Qinling Mountains’ hinterland, beyond the Han River’s upstream. The region’s history of frequent natural disasters makes it important for the regional government to prioritize disaster mitigation. The Shaanxi government introduced a disaster reduction relocation program in 2011 with the goal of achieving ecological stability and reducing the impact of natural disasters. This is the largest disaster relief and resettlement project in modern Chinese history (Li et al., 2015). The disaster reduction relocation program will move residents from the mountainous areas of southern Shaanxi, where natural disasters are frequent and infrastructure is inadequate, to safer towns and parks with improved infrastructure. Since the plan began, 267,300 households and 937,800 people have been relocated in Ankang, representing 39.7% of all people relocated in the province (Liu et al., 2020b). The primary resettlement methods include centralized and non-centralized resettlement. In centralized resettlement, an entire village is relocated as a new, customized community. In contrast, non-centralized resettlement involves dispersing residents into smaller units within their original settlements (Xu et al., 2022).

The data were gathered using household survey carried out in Ankang by our research team. For several administrative villages and resettlement communities, convenience sampling was used in this survey. Randomly chosen household members aged 18 to 65 were chosen for interviews (76% are household heads and the remaining 24% are other family respondents). To enhance the feasibility and representativeness of the samples, three large-scale resettlement communities located in Ziyang County and eight villages in Ningshan County and Hanbin District were selected. These areas not only participated in disaster resettlement projects but also had households that urgently needed to adopt appropriate strategies to enhance their well-being. The contents of the survey included demographic characteristics, the consumption behavior of rural households, and information related to relocation. The research team consisted of experienced teachers and students, and full support from the local government, which significantly enhanced the quality of field research. Once the questionnaires were completed, valid responses were input into the dataset for data processing In the end, 670 questionnaires were collected, of which 657 were valid, with an effective rate of 98.1%; in terms of sample composition, there were 198 responses from local households (accounting for 30.2%) and 459 from relocated households (accounting for 69.8%). Statistical tests confirmed that this sample size is sufficient to meet the requirements for correlation analysis of the core research variables and regression model estimation. Samples of local households serve solely as a regional benchmark reference, used to compare differences in livelihood levels among relocated households before and after relocation; by adding an additional local control dimension, it enables more accurate identification of the impact of relocation policies on livelihoods. Since the objective of this article is to explore the livelihood of relocated households, relocated samples were selected from the original data for empirical study.

The questionnaire consists of three main parts: (1) Basic household information, including household size, dependency ratio, education level, non-agricultural income, per capita income, and other related factors; (2) Household livelihood capital, which encompasses various indicators such as financial, material, natural, human, and social aspects; (3) Relocation-related information, including whether a household has been relocated, the relocation time, type, distance, and nature.

3.2 Research method

3.2.1 Multi-dimensional index of sustainable household well-being (SHWB)

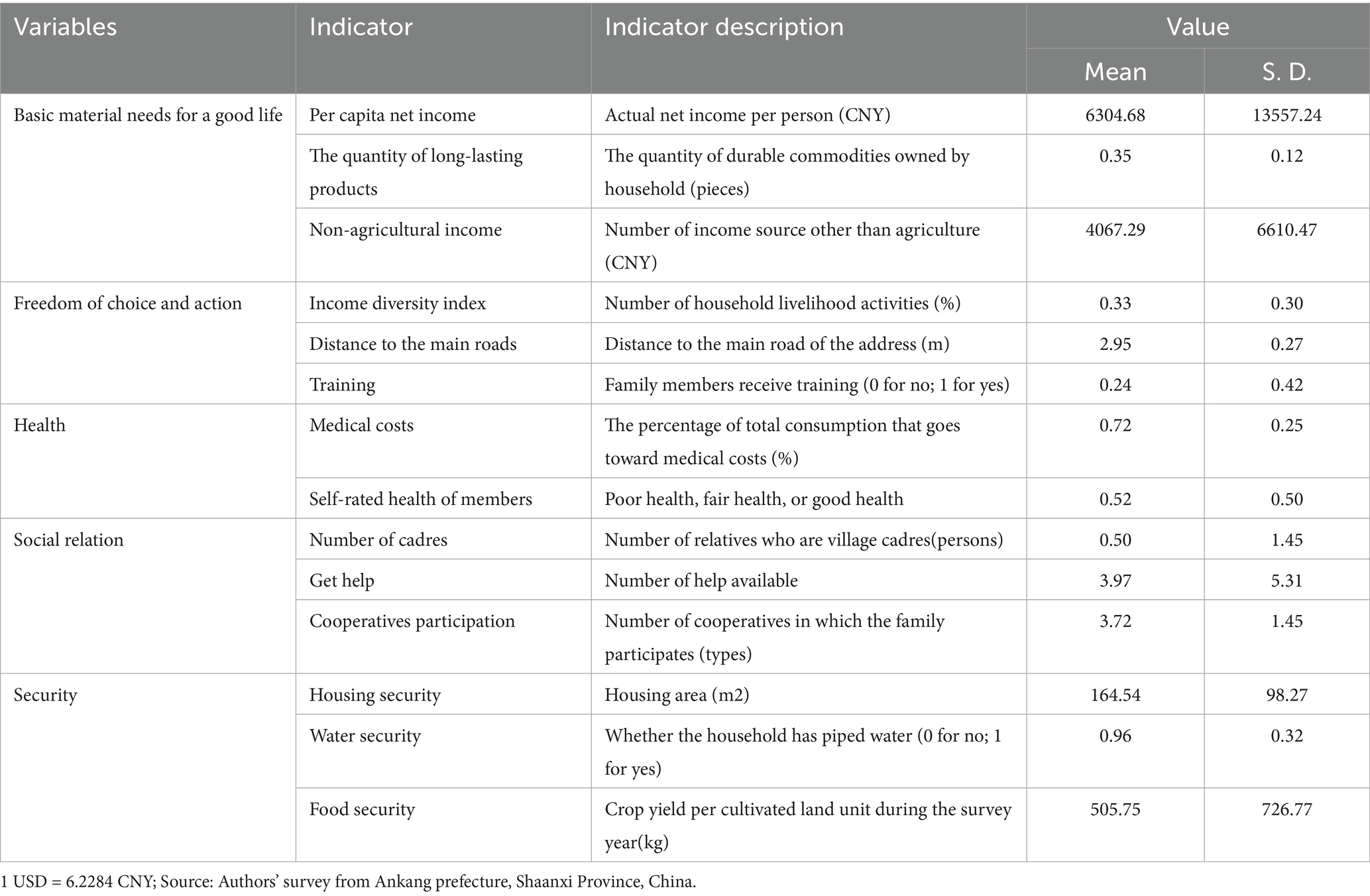

Recently, more research has focused on multidimensional well-being and Well-being is not just about household income. Based on the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) and the study of Peng et al. (2022), and combined with the concept of Sustainable Household, which refers to a household achieving sustainability in economic, social, and environmental dimensions, balancing the needs of the present generation with the development of future generations, and integrating the long-term sustainability of resource management, social relations, and quality of life (Smith et al., 2018). This study separated sustainable household well-being into five categories: (1) basic material needs for a good life; (2) freedom of choice and action; (3) health; (4) social relation; and (5) security. Next, based on earlier research (Liu et al., 2020b; Peng et al., 2022), a number of indicators were chosen for every dimension (Table 1).

In this study, the quantity of long-lasting products, per capita net income, and non-agricultural income made up the majority of the dimension of basic material needs for a good life. Typically, income is used as a gauge to assess the well-being of households (Li et al., 2021). Household well-being increases with the aforementioned income levels. In addition, long-lasting household products, such furniture and appliances, are also commonly used as markers to assess the standard of family life. The more long-lasting products, the higher the standard of living (Liu et al., 2020b). This dimension reflects the economic and material foundation of a sustainable household, and its sustainability lies in the diversification of income structure and the long-term use value of material assets. The dimensions of choice and freedom of action mainly indicate whether farmers have convenient transportation conditions and can successfully realize the livelihood transition from agriculture to non-agriculture. As a result, the freedom of choice and action aspects were represented using the income diversity index, the distance to the main roads, and training. Household income diversity refers to the fact that the sources of household income are not limited to one or two but include many different types of income sources. The degree of household income diversity is how the income diversity index is defined; the greater the index, the better the SHWB. The closer it is to the main road, the more convenient it is for residents to get around. At the same time, households with more training have better career opportunities, which are more favorable for better SHWB (Liu et al., 2020a, 2022). The health of the family members directly affects the happiness of a family. The indicators of the health dimension were selected from the members’ self-rated health status and medical costs. Self-rated health is a subjective assessment of one’s own state of health, and family members with high medical bills typically have poorer health (Liu et al., 2019). The dimensions of social relations include the quantity of village cadres, cooperative participation, and financial assistance. If a family has a village cadre, participation in cooperatives, and access to financial assistance, the family can lessen their vulnerability to outside shocks (Liu et al., 2022). This dimension shows the stock of social capital of a sustainable household. Through networks, trust, and norms, social capital enhances the household’s social adaptability and resource mobilization capacity (Putnam, 2000). Homes that can supply sufficient food, water, and decent shelter are considered to be part of the security aspect. Therefore, we employed food, water, and housing security were employed as indicators for this dimension (Liu et al., 2014).

3.2.2 Sustainable household well-being (SHWB) assessment model

Because the selected variable data have different dimensions, orders of magnitude, and amplitudes of change, the data were first handled using the range standardization approach. The processed data were dimensionless variables so that the different units of data could be compared. All of the metrics processed have values between 0 and 1. A suitable equation to employ is the one below Equation (1):

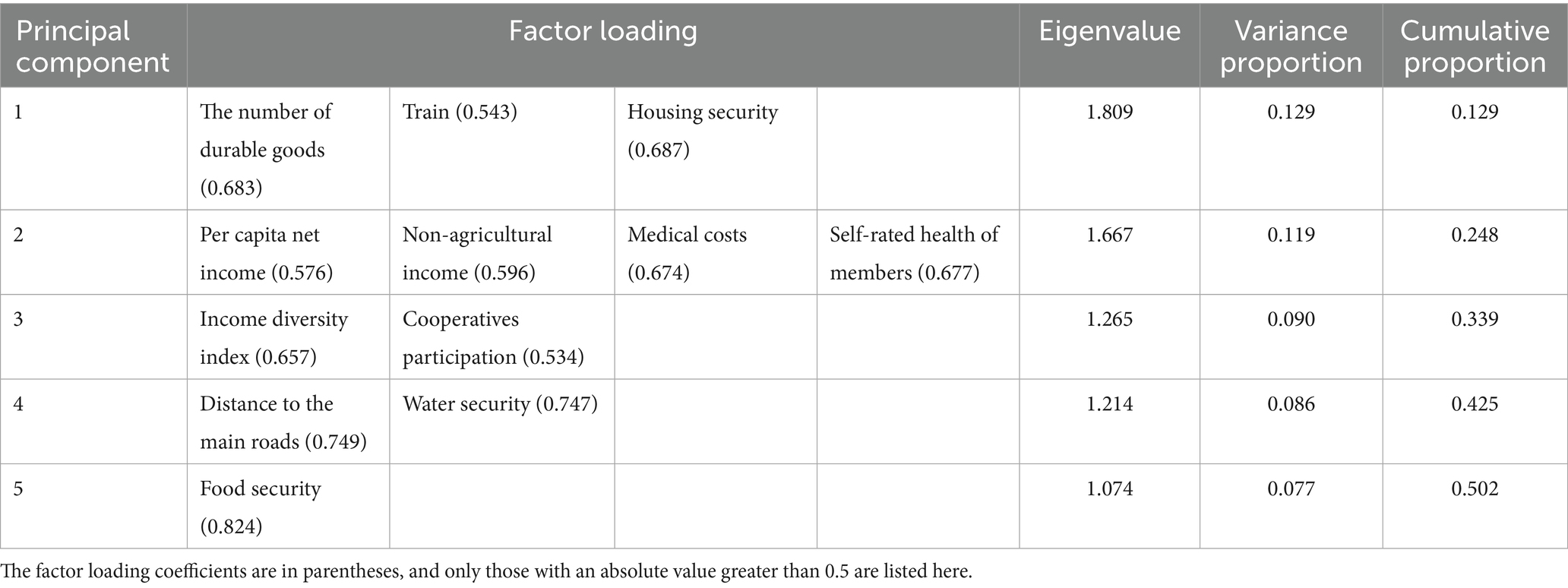

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed in this study to further identify the key variables influencing sustainable household well-being (Peng et al., 2022). The value of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) is 0.648, indicating that the sampling adequacy of this paper is reasonable and suitable for factor analysis (Liu et al., 2023). The statistics of the Bartlett spherical test is 1416.943, which is significant at a 1% level of significance. This shows that there is a notable distinction between the unit matrix and the correlation coefficient matrix and the data are appropriate for principal component analysis. Therefore, five principal components were extracted based on the principle that the eigenvalues were greater than 1 and accounted for the largest proportion. The cumulative variance contribution of these principal components was 50.21%, indicating that these five principal components explained 50.21% of the overall variance (Table 2). Specifically, according to the results of PCA, this paper takes the variance proportion as the weights and five principal component scores as the variables to construct the index of SHWB. The calculation formula is as follows Equation (2):

3.2.3 Regression model

The traditional linear regression model is essentially mean regression, where the only information acquired is the explanatory variable’s effect on the explained variable’s mean. However, it is not possible to characterize in detail the effect of the explanatory variables on the entire conditional distribution of the explanatory variables, and mean regression tends to be confounded by extreme values (Geoffrey et al., 2023). In order to further analysis, the determinants of farmers’ well-being against the background of disaster resettlement, quantile regression is used for quantitative analysis in this paper. The core idea of quantile regression is as follows: The interpreted variable is treated as a distribution function by minimizing the sum of the absolute values of the weighted residues, like the objective function. Then, the influence coefficient of the explanatory variable at the decimal point of the explained variable condition is estimated (Ng and Lew, 2009). Compared to the mean regression model, the quantile regression model is insensitive to extreme values, heteroscedasticity, and non-normal distribution, and the obtained estimated results are more robust (Korkmaz and Chesneau, 2021). At the same time, it can effectively capture the nonlinear impact of disaster resettlement on the well-being of farmers and help to mine rich information on distribution characteristics.

Previous studies have confirmed that factors affecting farmers’ livelihood and well-being include household size, household members’ education level, dependence ratio, per capita income, livelihood diversification index, credibility to others, access to loans, risk shock, etc. (Liu et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2024). Based on the above research findings, the authors of this paper took the household population characteristics and relocation characteristics as explanatory variables. The sustainable household well-being index was used as the explained variable. Regional variables were introduced to analysis the influence of different relocation characteristics on SHWB. We used Stata 14.1 statistical software to estimate the results for the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles.

All of the variables included in the regression analysis are listed in Table 3. Among them, the relocation characteristics included relocation nature, relocation distance, and relocation time. There were two categories of relocation nature: involuntary relocation and voluntary relocation, with a total of 395 farmers, and the voluntary relocation of farmers accounted for 86.057% of the total relocation. The distinction between involuntary and voluntary relocation is primarily based on the intention and reasons for the move. Involuntary relocation refers to the necessary relocation of residents due to decisions and actions imposed by external forces. The voluntary relocation of farmers may be due to serious ecological damage, disaster avoidance, poverty, or other reasons. The majority of the households in this article relocated to get away from the hazard such disasters posed. Zhou et al. (2021) found that the intensification of natural disasters increased residents’ desire to relocate (Zhou et al., 2021). Relocation distance consists of long-distance relocation and short-distance relocation. Long-distance relocation usually involves resettling individuals in new towns, often far from their original villages. In contrast, short-distance relocation typically places individuals in villages located within or near the existing administrative boundaries of their original communities. The relocation time refers to the entire phase of the actual relocation process, from the beginning of relocation preparation to the completion of relocation and settling. This phase does not include the preparation and house construction phases. Three categories were used to categorize the relocation times: short-term (less than 3 years), medium-term (three to 5 years), and long-term (more than 5 years). The most common was the short-term (46.37%), followed by the long-term (30.99%) and the medium-term (22.64%). Education level is human capital, and the SHWB increases with education level. Household size also affects household well-being to some extent (Rogers et al., 2020). A family’s economic status can be investigated through per capita income, with higher per capita income correlated with higher household well-being (Liu et al., 2020b). The percentage of old people and children in the labor force as a whole is known as the dependence ratio. The family’s financial burden will increase if the dependency ratio is higher than the value. The livelihood diversification index belongs to material capital and refers to the variety of ways that farmers earn a living. More types are more beneficial to household well-being (Liu et al., 2020a). Trust in others constitutes a component of social capital. Higher levels of credibility facilitate access to employment information and improve neighborhood mutual aid. Through this process, the supportive functions of social networks are strengthened, which increase households’ capacity to manage livelihood changes after relocation and mitigates exposure to external risks (Adger et al., 2005).

Finally, loans are a form of financial capital, mainly reflected manifested as the possibility of obtaining loans. Relocated households frequently need financial support to rebuild their livelihoods, and access to loans directly influences their resource allocation and risk-management capabilities.

4 Results

4.1 Comparison of SHWB of different types of relocation farmers

Disaster resettlement is a proactive measure to prevent natural disasters and improve the quality of life of farmers. By comparing the SHWB values of different types of relocated farmers, the impacts of different types of relocations were explored. The SHWB value can be positive or negative. The greater the SHWB values, the greater the life satisfaction of the relocated households. According to Table 4, compared to involuntarily relocated households (0.305), the overall SHWB of voluntarily relocation households (0.276) was substantially lower. Among them, the basic material needs for a good life, freedom of choice and action, and security well-being of voluntary relocation households were significantly lower than those of involuntary relocation households. However, in the dimension of social relation, voluntary relocation households scored higher than involuntary relocation households. Compared to short-distance relocation households (0.297), long-distance relocation households had a substantially lower overall SHWB (0.265). This is mainly reflected in the three dimensions of basic material needs for a good life, freedom of choice and action, and social relations. Meanwhile, medium or short-term relocation households had significantly lower scores than long-term relocation households in the five sub-dimensions of SHWB, in addition to having significantly lower overall SHWB (0.283) than the long-term relocation households (0.339). This reflects the “adaptation-improvement” process after relocation: in the short or medium term, farmers are at the stage of adapting to the new environment, with insufficient material accumulation and social relationship reconstruction. In the long term, they gradually complete resource integration and psychological adaptation, and the sense of happiness in all dimensions increases accordingly.

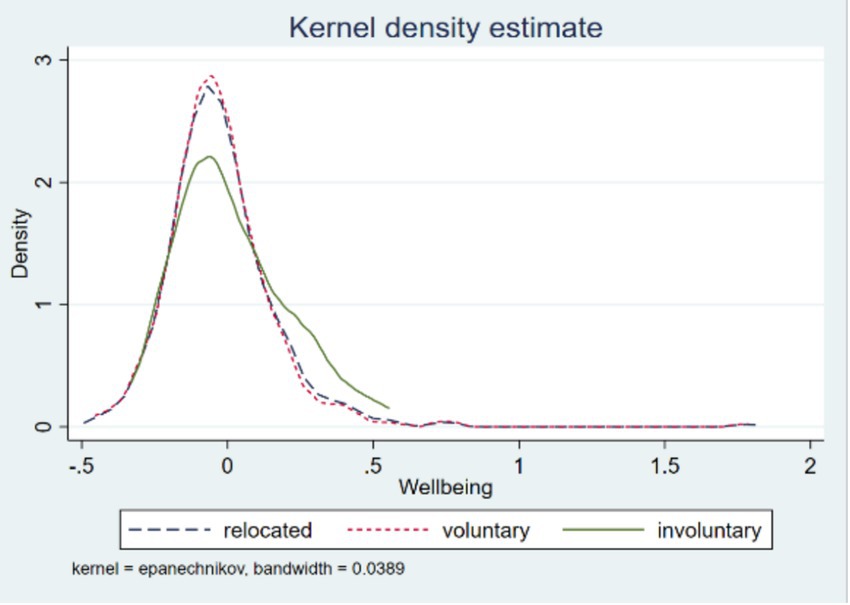

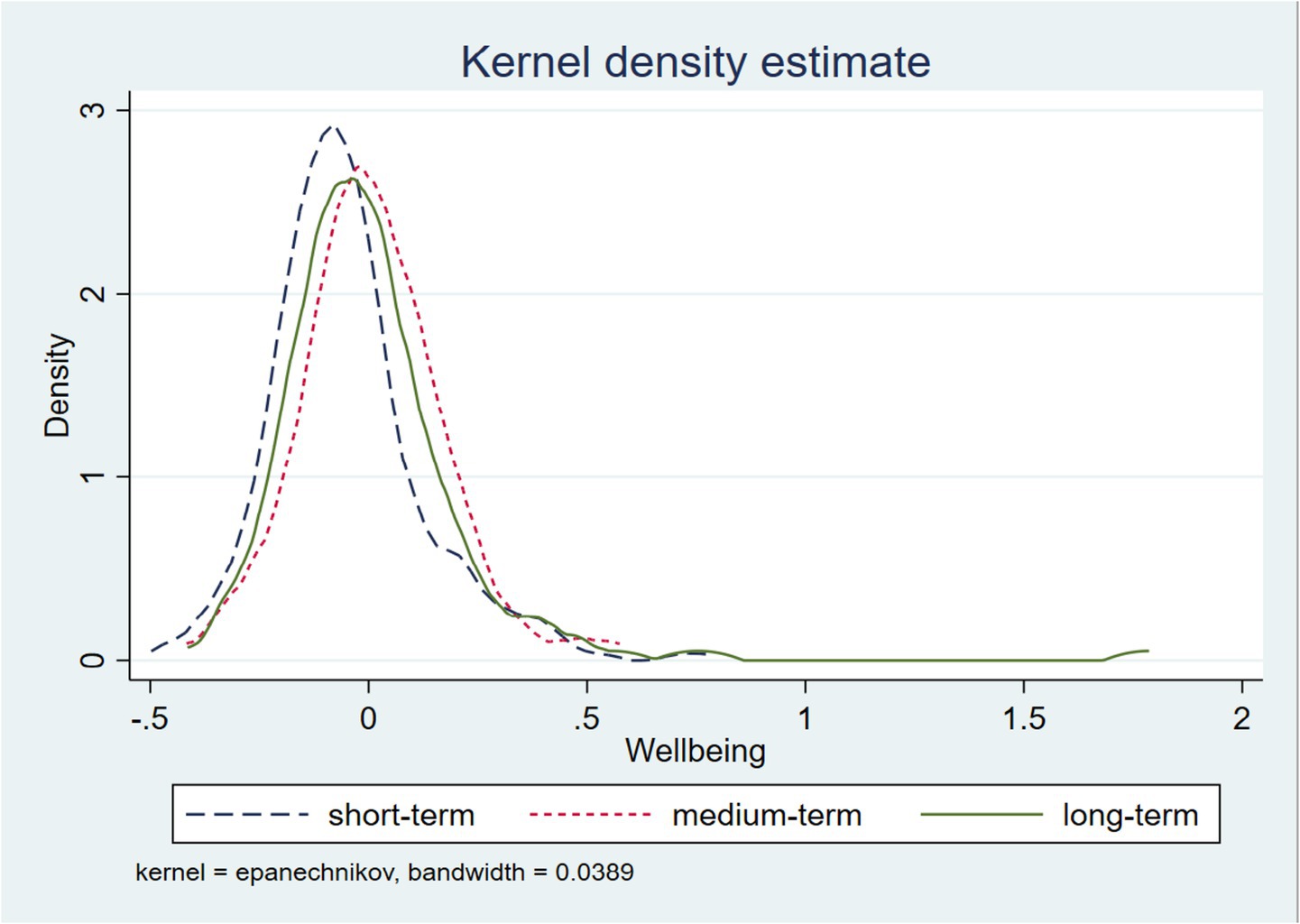

Furthermore, Figures 3–5 illustrate the distribution patterns of SHWB by relocation characteristics using kernel density estimation (KDE). KDE is a widely used nonparametric method for estimating the density function of a variable and visualizing its distribution; a higher peak indicates a greater concentration of observations at that SHWB level. As illustrated in Figure 3, the density peak for voluntarily relocated households is higher than that for involuntarily relocated households, and the density curve for involuntary relocations is flatter, indicating greater dispersion and thus more volatility in SHWB among involuntarily relocated households. Figure 4 shows the density for long-distance relocation households is slightly higher than that for short-distance relocation households, while the short-distance relocation curve is markedly flatter, recommending that SHWB levels among short-distance relocation households are more volatile and that long-distance relocation households show comparatively more stable SHWB. Figure 5 also exhibits dissimilarity in the density distributions among short-term, medium-term, and long-term relocations: the density for short-term relocations is mor than for medium-term and long-term relocations, while the curves for medium-term and long-term relocations are flatter, implying greater volatility in SHWB for those groups. In contrast, the curve for short-term relocations is steeper, indicating that SHWB levels among short-term relocations are less volatile.

4.2 Rural household characteristics in Ankang prefecture

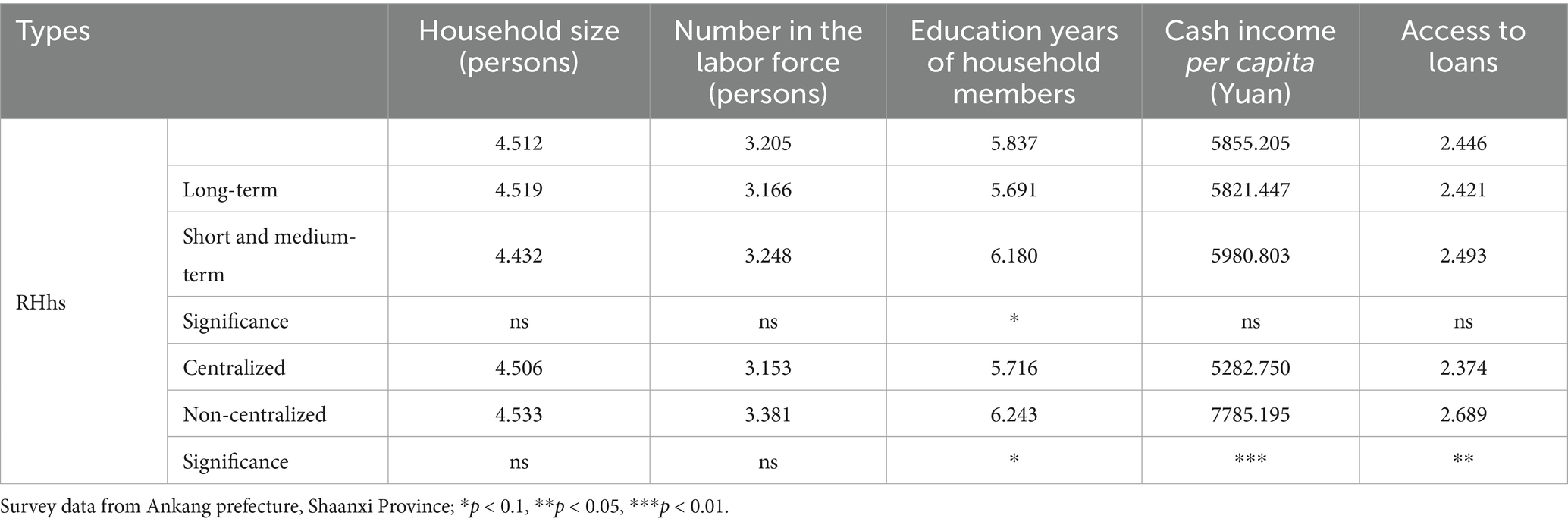

As demonstrated in Table 5, the authors employed the T-test to investigate if there were any significant differences between relocation households (RHhs) at different relocation times and relocation types. The primary relocation types include centralized and non-centralized relocations. In centralized relocation, an entire village is relocated as a new, customized community. By contrast, non-centralized relocation involves dispersing residents into smaller units within their original settlements. The survey found that the households with different relocation features had distinct characteristics in some ways, such as the education years of household members, cash income per capita and access to loans. For relocation time, the education years of household members in long-term relocation was 5.691 years, and that of short and medium-term relocation was 6.180 years. For relocation type, the cash income per capita in non-centralized relocation was CNY 5,282.750, while that of those in centralized relocation was relatively high, which was CNY 7,785.195; the numbers of education years of household members in centralized relocation and non-centralized relocation were about 5.716 and 6.243 years, respectively; and the levels of access to loans were 2.374 and 2.689, respectively. Table 6 shows that there was a significant difference between the education years of household members in long-term and short and medium-term relocation. There were significant differences in the education years of household members, access to loans, and cash income per capita in centralized and non-centralized relocation, and the significance gradually increased.

4.3 Quantile regression

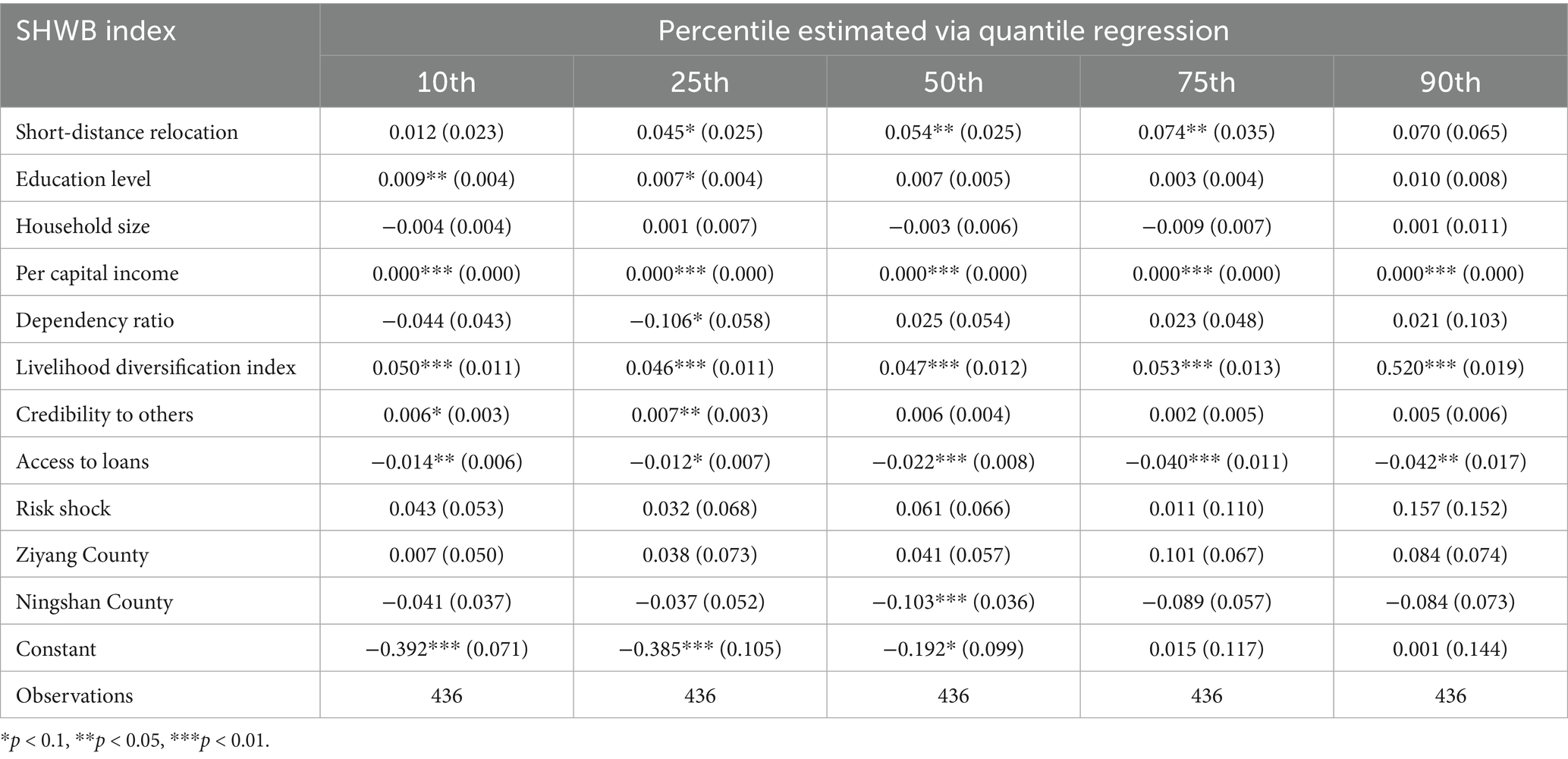

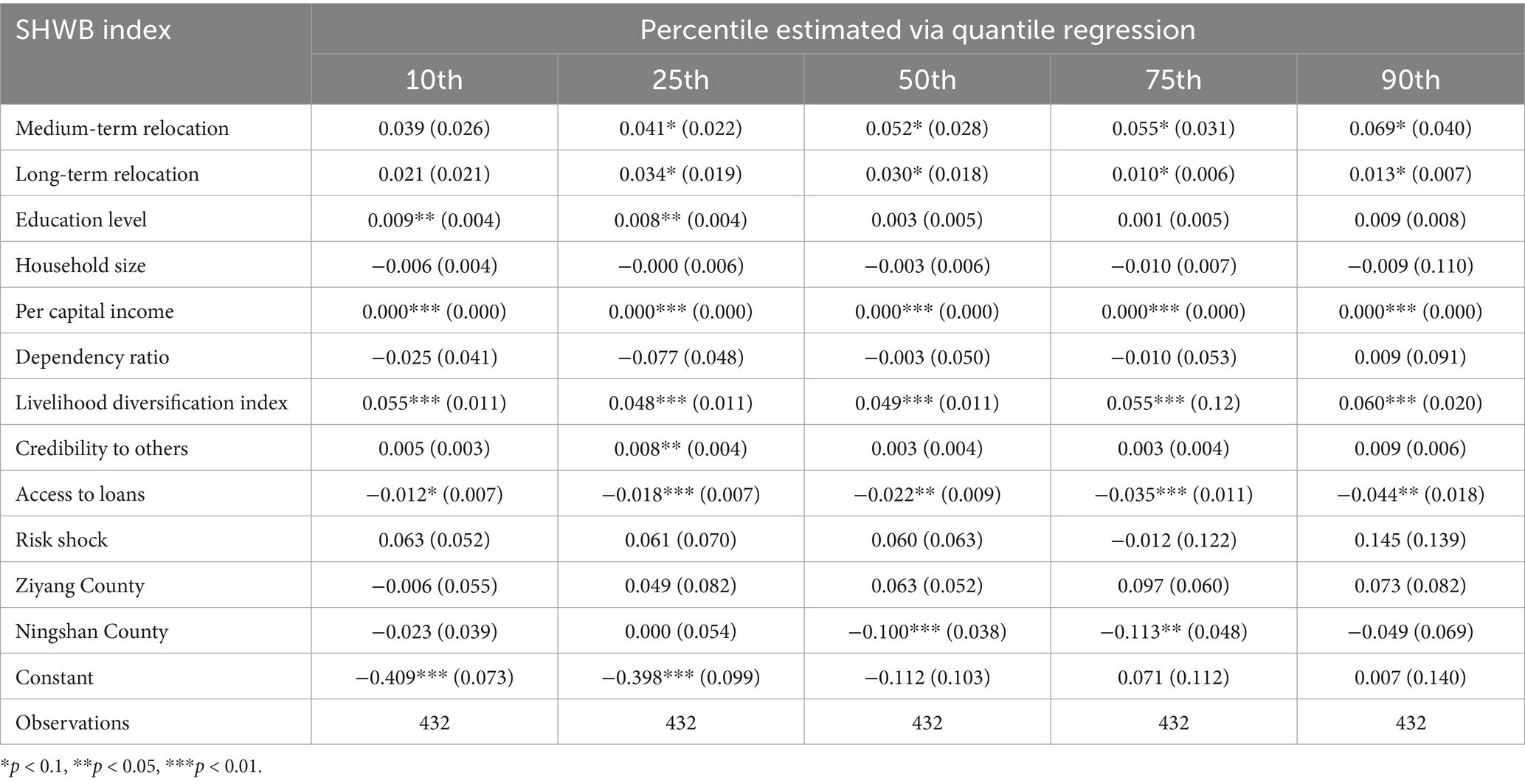

Tables 6–8 illustrates the following results: First, voluntary relocation has a significant negative impact on SHWB at the 75th and 90th percentiles but shows no significant effect at other percentiles. Second, short-distance relocation significantly enhances SHWB at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, with the impact generally increasing as the SHWB percentile rises. Third, medium-term relocation positively affects SHWB at the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles, while long-term relocation shows a similar positive impact at the same percentiles. Fourth, the educational level of household members has a positive impact on the 20th and 25th percentiles. Fifth, a number of additional household attributes seem to be crucial as well, for instance, per capital income and the livelihood diversification index significantly improve SHWB across all distribution percentiles.

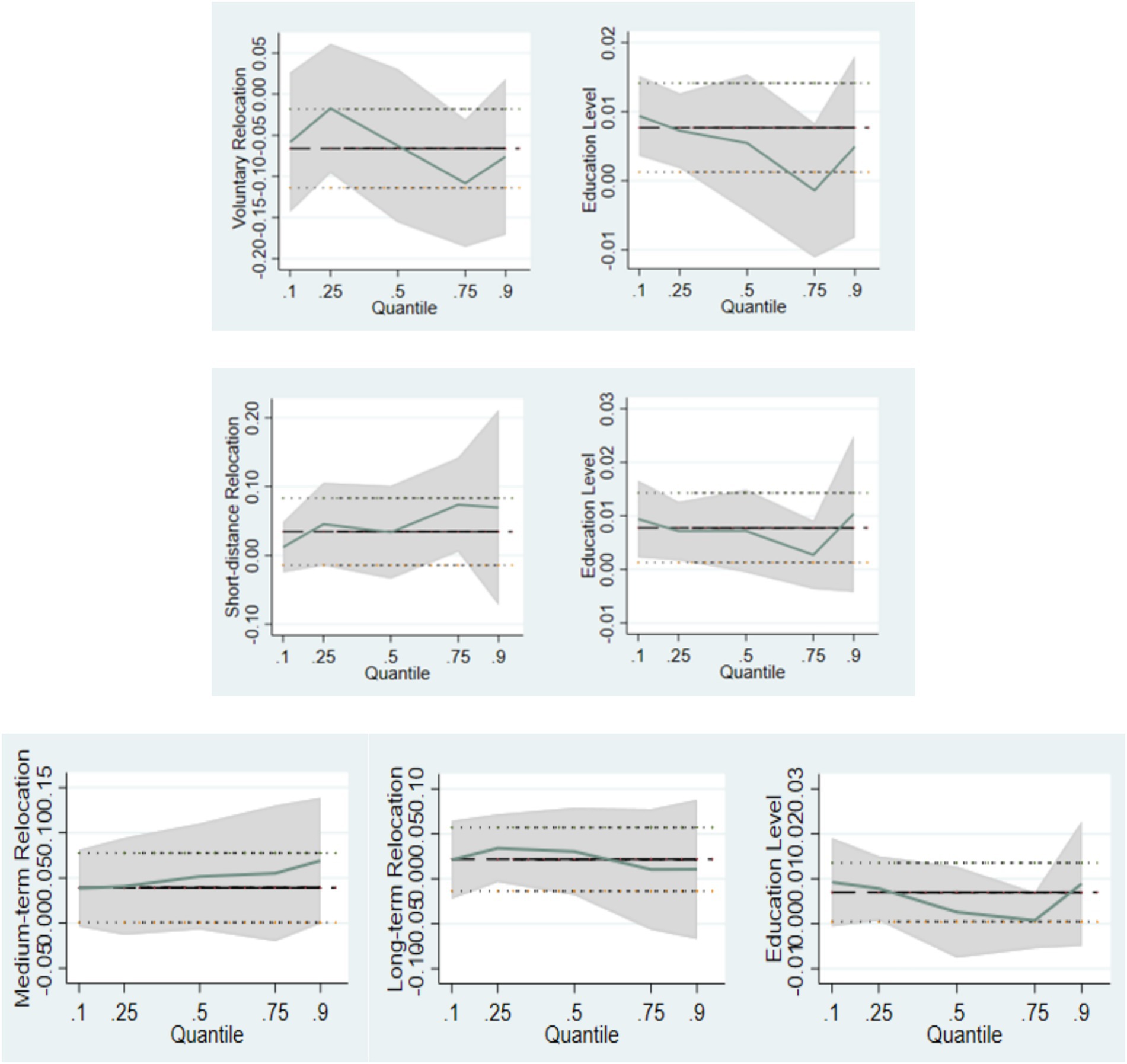

Figure 6 successively plots the coefficient estimates of relocation nature, relocation distance, relocation time, and their respective percentiles of education level. The results show that with increases in the quantile level, the following occurred: (1) In general, the impact of education level on the SHWB shows a “U-shaped” change characteristic, which decreases first and then increases. First, it slowly drops to the 50th percentile, then rapidly drops to the 70th percentile, reaching the lowest value, and then presents an upward trend to the 90th percentile. (2) The trend of growing, reducing, and then increasing was observed in the effect of voluntary relocation on the SHWB. It first increased to the 25th percentile and reached the highest value, then continued to decline to the 75th percentile and reached the lowest value and finally showed an increasing trend at the 75th percentile. (3) The impact of short-distance relocation on the SHWB generally increased first, then decreased, and then increased. It first rose to the 25th percentile and then showed a downward trend to the 50th percentile, but the value was not lower than the 10th percentile at this time. Then, there was an upward trend in the 50th -70th percentiles, and finally, there was a slow downward trend after the 70th percentile, and it tended to flatten out to the 90th percentile. (4) Medium-term relocation had a significant positive effect on SHWB. (5) The effects of long-term relocation on SHWB demonstrated a trend of first growing and then declining. It reached the highest value at the 25th percentile and the lowest value at the 75th percentile, and then tended to be flat, but the overall change was small.

4.4 Heterogeneity analysis

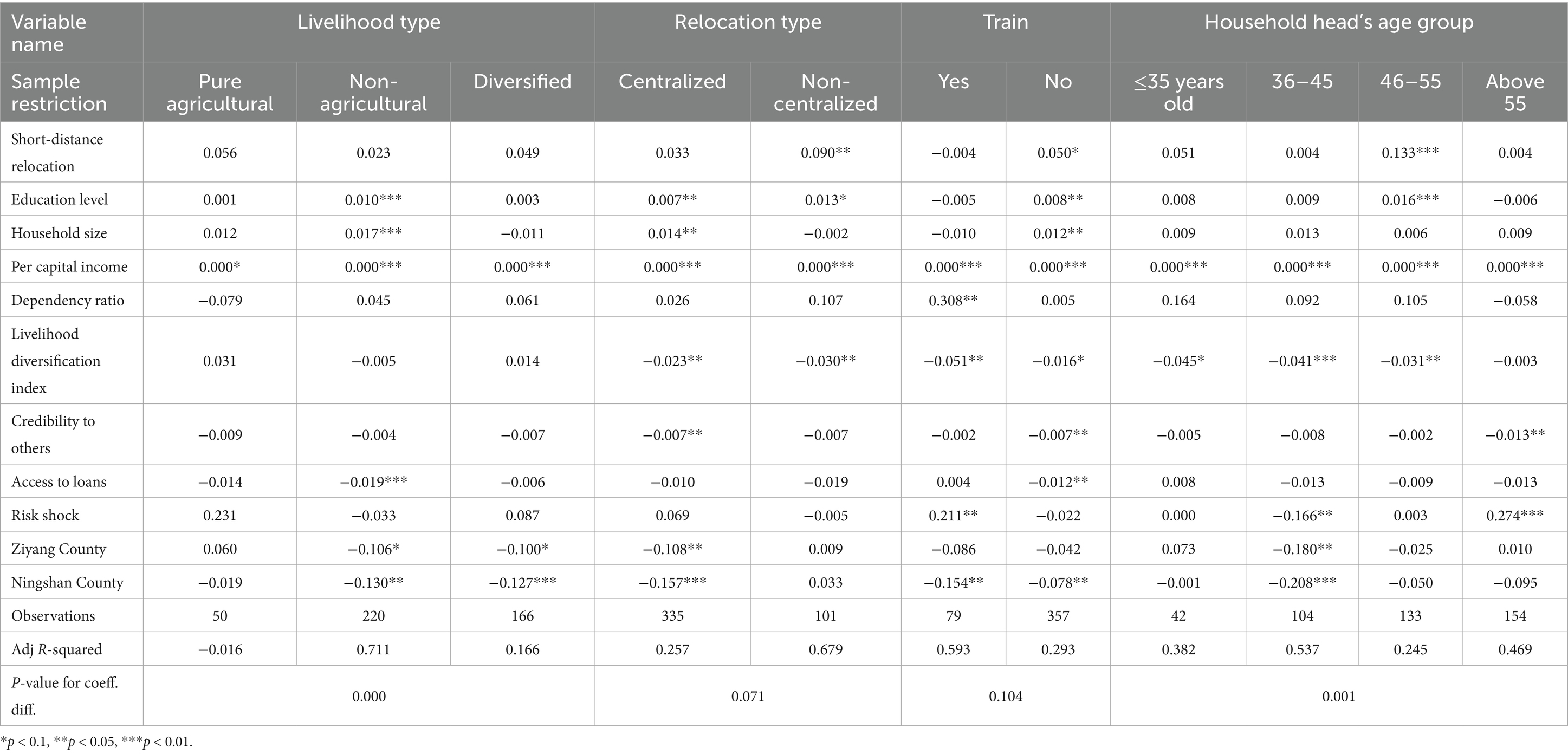

Heterogeneity analysis shows marked variation in how relocation characteristics and household capital affect Sustainable Household Well-being (SHWB) across unlike groups (Tables 9–11). Concerning livelihood types, educational attainment and household size show significantly positive effects on SHWB among non-agricultural households, underscoring the crucial role of human capital in facilitating successful livelihood transitions. In contrast, most variables are not important for purely agricultural households, indicating their particular vulnerability to relocation shocks. Regarding resettlement approaches, centralized households rely more on internal capital accumulation like education, whereas non-centralized households benefit more from the locational advantages of short-distance relocation, consistent with the main regression results. From the perspective of the age structure of the household head, the 46–55 age group shows the strongest effects of relocation distance and educational attainment on SHWB, reflecting their superior adaptive capacity. Interestingly, among those aged 55 and older, risk exposure is positively associated with SHWB, possibly indicating a protective effect of policy safeguards for elderly households. Taken together, these results validate the robustness of the main regression findings and recommend the need for tailored policy interventions, including promoting employment in non-agricultural sectors, optimizing resettlement models, and strengthening support for middle-aged and elderly households to holistically increase the sustainable well-being of relocated families.

5 Discussion

This paper focuses on exploring the sustainable household well-being (SHWB) of rural households and its influencing factors, using the example of the disaster resettlement project in the Ankang area of Shaanxi Province. The results reveal that the nature of relocation, relocation distance, and relocation duration are all important determinants of the SHWB of relocated households, indicating distinct pathways across the sub-dimensions of well-being. These findings align with prior research suggesting that different relocation attributes are able to pose challenges to the well-being and sustainability of relocated households (Liu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2023). Such variation can be attributed to dissimilar in the types and magnitudes of livelihood capital possessed by rural households with different relocation characteristics, as well as the differential expressions of their livelihood endowments and attributes (Guo and Kapucu, 2018; Guo et al., 2022).

Further, regarding the nature of relocation, the results show that voluntarily relocated households report significantly lower SHWB compared with involuntarily relocated households, particularly in the dimensions of basic material needs, freedom of choice and action, and security. Notably, the regression results indicate that voluntary relocation displays a significantly negative impact on SHWB. This finding contrasts with the view proposed by Rogers et al. (2020), who posited that voluntary relocation could improve human well-being. In this paper, we argue that Rogers et al. (2020) overestimate the positive impact of voluntary relocation on human well-being. In practice, voluntary relocation in Ankang often represents a “passive-active” choice made by households facing substantial livelihood pressures in their original locations. Although they actively adapt to their new lives, they frequently begin from a position of relative disadvantage in terms of human and financial capital (Chen and Wang, 2015; Thulstrup, 2015). This inherent vulnerability constrains their capacity to withstand the risks associated with relocation. These patterns underscore the need for policy measures that address the vulnerabilities of households undergoing voluntary relocation.

As Tang et al. (2021) pointed out, disaster resettlement not only incurs substantial relocation expenses but also heightens the livelihood vulnerability of relocation households, exposing them to greater risks compared to residents in their communities (Tang et al., 2021). Second, short-distance relocation has significant positive impact on SHWB. On the one hand, this is because of the public services, workforce training programs, and employment opportunities of the government (Zhou et al., 2021). However, the targeting-discrepancy in policy support cannot be overlooked. Within the framework of China’s large-scale, state-led policy initiatives, government-mobilized relocation is treated as a systematic undertaking, providing households with comprehensive policy guarantees, including housing assistance, skills training, and industrial support (Rogers et al., 2020). Empirical evidence from western China and Shaanxi Province demonstrates that such systematic state support directly enhances rural households’ well-being, decrease their reliance on fragile ecosystems, and lays a foundation for sustainable livelihoods (Li et al., 2018, 2021).

In contrast, voluntary relocation households are often regarded as having made individual choices and are thus frequently excluded from this systematic support network. This imbalance in policy coverage undermines the intended benefits of resettlement programs, since participation in such initiatives is closely associated with improved subjective well-being and successful integration (Tang et al., 2021, 2022). Consequently, the most vulnerable groups, who are in greatest need of support, struggle to obtain sufficient public resources, resulting in significantly lower well-being levels across multiple dimensions, including material conditions and sense of security. Therefore, the key factor determining the success of relocation may not be the “voluntary” attribute itself, but rather the intensity and precision of policy intervention. Strong state support can transform relocation into an effective pathway for improving livelihoods, whereas relocation without systematic policy backing may leave vulnerable households to face multiple shocks from market and environmental challenges alone, ultimately undermining their sustainable well-being. Regarding relocation distance, short-distance relocation has significant positive effect on SHWB, especially in dimensions of basic material needs, freedom of choice and action, and social relationships, the well-being level of short-distance relocated households is significantly higher than that of long-distance relocated households. On the one hand, this is because of the public services, workforce training programs, and employment opportunities of the government (Zhou et al., 2021).

Rogers and Xue (2015) also confirmed this perspective, finding that short-distance relocation expands household income opportunities and enhances SHWB for rural households. On the other hand, the current residence of short-distance relocation households is closer to their original residence, and the original living environment and social network have less impact. Meanwhile, the resettlement subsidy provided by the government also facilitates the faster integration of relocated households into the new environment (Khan et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2024). Chen et al. (2017) and Galarza-Villamar et al. (2018) support this view. They found that long-distance relocation destroys the physical and social capital of rural households, resulting in a reduction in the diversity of their livelihoods. In addition, it can lead to the separation of rural households from relatives and neighbours, which is not conducive to enhancing the well-being of rural households (Chen et al., 2017; Galarza-Villamar et al., 2018).

In the terms of relocation time, both medium-term and long-term relocation have a crucial positive effect on SHWB, and further, long-term relocated households scored significantly higher than medium- or short-term ones in the five sub-dimensions of well-being. This is because the government has provided sustained subsidies and follow-up support to medium and long-term relocation households (Xu et al., 2022). These measures lessen the suffering of relocated households devoid of requisite resources and social rights (Khan et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2023). This result is consistent with the opinions of Lo et al. (2016); they found that if short-term relocation is carried out, the government will only focus on the relocation process and tends to ignore subsequent support (Lo et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2024). It is undeniable that short-term relocation also optimizes the household livelihood strategy and achieves self-development. However, the short-term relocation households have not absorbed and digested the disturbance and intervention of the external environment in a short time (Li et al., 2017). Additionally, Liu et al. (2024) found that children from short-term relocation households face challenges in adapting to the new education system and teaching methods within a limited time frame, which adds further pressure and risk for these households(Liu et al., 2024). These are similar to the findings of this paper; the medium and long-term relocation process is longer, so that relocation households have sufficient time to adapt to the new environment. Meanwhile, follow-up support policies can also play a full role in this process, helping relocated households to achieve economic and psychological integration by developing their capacity (Guo et al., 2023).

In addition, the degree of education of household members also has a significant positive impact on SHWB. The more educated the individuals of the household, the greater their organizational learning capacity and the better able they are to take full advantage of the policy opportunities brought about by relocation, leading to rapid livelihood transformation (Xu et al., 2022). Members of households with greater educational backgrounds are abler to master organizing skills. They are often more able to make full use of policy opportunities brought by relocation, seize employment opportunities, and quickly realize livelihood transformation (Liu et al., 2020b). Su et al. (2023) also found that household members with higher education levels tend to have better employment opportunities and earn higher salaries (Su et al., 2023). This directly enhances the economic foundation of households, facilitating their ability to meet basic needs more effectively. In addition, the level of education of household members is part of human capital, and the quality and quantity of human capital are important endowments for relocation households to reduce livelihood risks (Gao et al., 2022). The higher the education level of household members, the more significantly they can reduce the total level of social risks and livelihood risks (Guo and Kapucu, 2018). Relocating households can better handle a range of risks, and SHWB rises as a result.

6 Limitations

There may be some limitations in this study that cussed more attention in subsequent research. Firstly, regarding data collection, the convenience sampling method may limit sample representativeness and create sampling bias. Meanwhile, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to dynamically track changes in rural household well-being over time.

Secondly, in terms of indicator construction, the subjective well-being (SHWB) weights were derived using principal component analysis, which relies on objective data to determine the weights by ignoring subjective empirical knowledge. Future research could improve the scientific nature of the weighting system by integrating multiple methods such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Although the SHWB measurement framework improved in this study is applicable in the current context, whether it can be applied to other regions, especially developing countries with significantly different socio-cultural backgrounds, requires further validation through cross-cultural and cross-regional comparative research. Thirdly, related to data limitations, this study employed quantile regression analysis to scientific examine as much as possible. However, further improved research with more advanced statistical models cannot be ruled out. In addition, the factors affecting subjective well-being are complex (Assessment, 2005). Although this study introduced relevant relocation characteristics, it cannot cover all relevant variables. Fourthly, the resettlement of disaster victims in other areas of Shaanxi was not considered, which has some geographical limitations. Additionally, further research should obtain rural household data from multiple time periods to enable broader for discussion. Finally, the impacts vary across relocation contexts, and the findings of this study may be more applicable to disaster resettlement as a preventative measure. Future studies could also delve deeper into relocation policies from different contexts for a wider discussion.

7 Conclusions and recommendations

7.1 Conclusions

This study employs a quantile regression model to empirically examine sustainable household well-being (SHWB) and its determinants under disaster resettlement. The results show that compared to voluntary relocation households, long-distance relocation households, and medium or short-term relocation households, the SHWB of involuntary relocation households, short-distance relocation households, and long-term relocation households, respectively, is not only significantly higher, but also fluctuates greatly. In addition, voluntary relocation has a significant negative impact on SHWB, while short-distance, medium, and long-term relocation has a significant positive impact on SHWB. At the same time, there was a noteworthy positive link seen between the education level of household members and SHWB. Based in the disaster-prone and ecologically vulnerable rural areas of western China, this study establishes a paradigm for enhancing farmers’ livelihood quality and improving sustainable household well-being. The key determinants of Sustainable Household Well-being (SHWB) identified in this context, particularly the role of relocation characteristics and human capital—offer transferable insights and policy lessons for other rural regions in China, as well as for low- and middle-income countries facing similar developmental challenges elsewhere.

7.2 Recommendations

To address the well-being issues arising from the implementation of disaster resettlement policies, stakeholders and policymakers must collaborate. The government should prioritize coordinating well-being enhancement and ecological protection when formulating policies. This can assist in improving the quality of life of relocated households by providing employment information, skills training, adequate arable land, and non-agricultural employment opportunities. In addition, the government should continue to implement the compulsory education policy and provide strong educational subsidies and support (Liu et al., 2020b). Achieving sustainable livelihoods for relocated households is crucial. Relocated households must also actively adapt to their new surroundings and accumulate livelihood capital in order to cope with risks (Guo et al., 2023). Although regional variations may exist in the study’s results, improving the well-being of rural households is a long-term process (Su et al., 2023). This paper has tried to draw a link between disaster resettlement policies and SHWB, thus enhancing the standard of living for rural households and fostering sustainable livelihoods. We look forward to more theoretical and empirical studies in the future to provide clear guidance on how to enhance the well-being of rural households after disaster resettlement.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

QZ: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XL: Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YD: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. WL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71803149; No.72474173; No. 72503176; No.72574182), the Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2023R010), the Long yuan Young Talents, Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Gansu Province (Grant No. 2024YB070), and the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2025KG-YBXM-113).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the local government and the patient cooperation of the interviewees during the data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adger, W. N., Hughes, T. P., Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., and Rockström, J. (2005). Social-ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 309, 1036–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1112122,

Assessment, M. E. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Wetlands and water. Washington, D.C.: World resources institute.

Barua, P., Rahman, S. H., and Molla, M. H. (2017). Sustainable adaptation for resolving climate displacement issues of south eastern islands in Bangladesh. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manage. 9, 790–810. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2017-0026

Chen, Y., Tan, Y., and Luo, Y. (2017). Post-disaster resettlement and livelihood vulnerability in rural China. Disaster Prev Manag 26, 65–78. doi: 10.1108/DPM-07-2016-0130

Chen, T.-L., and Tsai, C.-E. (2021). Coping with extreme disaster risk through preventive planning for resettlement. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 64:102531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102531

Chen, Y., and Wang, J. (2015). Social integration of new-generation migrants in Shanghai China. Habitat Int. 49, 419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.06.014

Defe, R., and Matsa, M. (2021). The contribution of climate smart interventions to enhance sustainable livelihoods in Chiredzi district. Clim. Risk Manag. 33:100338. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2021.100338

DFID (2000). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: Department for International Development.

Ellis, F. (2000). Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fang, Z., Liao, Y., Ma, C., and Wu, R. (2024). Examining the impacts of urban, work and social environments on residents’ subjective wellbeing: a cross-regional analysis in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1343340. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1343340

Fulford, R. S., Smith, L. M., Harwell, M., Dantin, D., Russell, M., and Harvey, J. (2015). Human well-being differs by community type: toward reference points in a human well-being indicator useful for decision support. Ecol. Indic. 56, 194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.04.003

Galarza-Villamar, J. A., Leeuwis, C., Pila-Quinga, G. M., Cecchi, F., and Párraga-Lema, C. M. (2018). Local understanding of disaster risk and livelihood resilience: the case of rice smallholders and floods in Ecuador. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 31, 1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.08.009

Gao, B., Li, C., and Li, S. (2022). Follow-up supportive policy, resource endowments, and livelihood risks of anti-poverty relocated households: evidence from Shaanxi province. Econ. Geogr. 42, 168–177. doi: 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2022.04.019

Geoffrey, S. Z., Obamiyi, S. E., Badeji-Ajisafe, B., Ayogu, B., Abiola, K., and Abiola, O. B.. 2023. Analysis of quantile regression as an alternative to multiple linear regression: (a case study of birth weight data) 2023 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG), 1–7.

Guo, X., and Kapucu, N. (2018). Examining the impacts of disaster resettlement from a livelihood perspective: a case study of qinling mountains, China. Disasters 42, 251–274. doi: 10.1111/disa.12242,

Guo, H., Li, J., and Li, X. (2023). Enhancing capabilities and promoting empowerment: how do follow-up support measures affect urban resettled household integration in China? Habitat Int. 140:102905. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102905

Guo, M., Li, C., Wang, G., and Innes, J. L. (2022). Examining the links between livelihood sustainability and environmental protection in the anti-poverty relocation and settlement program areas: an empirical analysis of Shaanxi, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1047223. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1047223

Guo, H., Rogers, S., Li, J., and Li, C. (2024). Farmers to urban citizens? Understanding resettled households’ adaptation to urban life in Shaanxi, China. Cities 145:104667. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2023.104667

Hwang, S.-S., Cao, Y., and Xi, J. (2011). The short-term impact of involuntary migration in China’s three gorges: a prospective study. Soc. Indic. Res. 101, 73–92. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9636-1

Kassouri, Y., and Altintas, H. (2020). Human well-being versus ecological footprint in MENA countries: a trade-off? J. Environ. Manag. 263:110405. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110405,

Khan, M. A., Hasan, K., and Kabir, K. H. (2022). Determinants of households’ livelihood vulnerability due to climate induced disaster in southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Prog. Disaster Sci. 15:100243. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2022.100243

Khattri, M. B. (2021). Differential vulnerability and resilience of earthquake: a case of displaced Tamangs of Tiru and Gogane villages of Central Nepal. Prog. Disaster Sci. 12:100205. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100205

King, M. F., Renó, V. F., and Novo, E. M. L. M. (2014). The concept, dimensions and methods of assessment of human well-being within a socioecological context: a literature review. Soc. Indic. Res. 116, 681–698. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0320-0

Korkmaz, M. C., and Chesneau, C. (2021). On the unit burr-XII distribution with the quantile regression modeling and applications. Comput. Appl. Math. 40:29. doi: 10.1007/s40314-021-01418-5

Li, C., Guo, M., Li, S., and Feldman, M. (2021). The impact of the anti-poverty relocation and settlement program on rural households’ well-being and ecosystem dependence: evidence from western China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 34, 40–59. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2020.1728455

Li, M., Huo, X., Peng, C., Qiu, H., Shangguan, Z., Chang, C., et al. (2017). Complementary livelihood capital as a means to enhance adaptive capacity: a case of the loess plateau, China. Glob. Environ. Change 47, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.10.004

Li, C., Li, S., Feldman, M. W., Li, J., Zheng, H., and Daily, G. C. (2018). The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of a major relocation and settlement program: a case in Shaanxi, China. Ambio 47, 245–259. doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-0941-7,

Li, Y., Li, S., Gao, Y., and Wang, Y. (2013). Ecosystem services and hierarchic human well-being: concepts and service classification framework. Acta Geograph. Sin. 68, 1038–1047. Available online at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130187122

Li, C., Zheng, H., Li, S., Chen, X., Li, J., Zeng, W., et al. (2015). Impacts of conservation and human development policy across stakeholders and scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 7396–7401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406486112,

Liu, W., Cheng, Y., Li, J., and Feldman, M. (2022). Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 6:1067649. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.1067649

Liu, W., He, L., Xu, J., and Xu, D. (2023). Linking natural resource dependence to sustainable household wellbeing: a case study in western China. Agriculture 13:1935. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13101935

Liu, W., Li, J., Ren, L., Xu, J., Li, C., and Li, S. (2020a). Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 150, 977–998. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02347-2

Liu, W., Li, J., and Xu, J. (2020b). Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 49:101649. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101649

Liu, W., Liu, J., Xu, J., Li, J., and Feldman, M. (2024). Examining the links between household livelihood resilience and vulnerability: disaster resettlement experience from rural China. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1340113–1340126. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1340113

Liu, W., and Wu, X. (2023). Poverty alleviation resettlement and household natural resources dependence: a case study from Ankang prefecture, China. Agriculture 13:1034. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13051034

Liu, W., Xu, J., and Li, J. (2018). The influence of poverty alleviation resettlement on rural household livelihood vulnerability in the western mountainous areas, China. Sustainability 10:2793. doi: 10.3390/su10082793

Liu, W., Xu, J., Li, J., and Li, S. (2019). Rural households’ poverty and relocation and settlement: evidence from western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:2609. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142609,

Liu, X., Zhang, B., Zheng, Q., He, X., Zhang, T., Jia, Y., et al. (2014). Study on the effect of returning farmland to forest on farmers’ welfare in the loess plateau: a case study of Ningwu County. Resour Sci 36, 397–405. Available online at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130611810

Lo, K., and Wang, M. (2018). How voluntary is poverty alleviation resettlement in China? Habitat Int. 73, 34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.01.002

Lo, K., Xue, L., and Wang, M. (2016). Spatial restructuring through poverty alleviation resettlement in rural China. J. Rural. Stud. 47, 496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.006

Manatunge, J. M. A., and Abeysinghe, U. (2017). Factors affecting the satisfaction of post-disaster resettlers in the long term: a case study on the resettlement sites of tsunami-affected communities in Sri Lanka. J. Asian Dev. 3, 94–124. doi: 10.5296/jad.v3i1.10604

Ng, P. T., and Lew, A. A. 2009. Quantile regression analysis of visitor spending: an example of mainland Chinese tourists in Hong Kong: Working paper series–09-06. NAU W.A. Franke College of Business.

Peng, W., Robinson, B. E., Zheng, H., Li, C., Wang, F., and Li, R. (2022). The limits of livelihood diversification and sustainable household well-being, evidence from China. Environ. Dev. 43:100736. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100736

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. J. Democr. 11, 22–36.

Qiu, J., Liu, Y., Yuan, L., Chen, C., and Huang, Q. (2021). Research progress and prospect of the interrelationship between ecosystem services and human well-being in the context of coupled human and natural system. Prog. Geogr. 40, 1060–1072. doi: 10.18306/dlkxjz.2021.06.015

Reddy, A. A. (2018). Involuntary resettlement as an opportunity for development: the case of urban resettlers of the new Tehri town. J. Land Rural Stud. 6, 145–169. doi: 10.1177/2321024918766590

Rogers, S., Li, J., Lo, K., and Guo, H. (2020). Moving millions to eliminate poverty: China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement. Dev. Policy Rev. 38:541–554. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12435

Rogers, S., and Xue, T. (2015). Resettlement and climate change vulnerability: evidence from rural China. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 35, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.005

Savari, M., and Shokati Amghani, M. (2022). Swot-fahp-tows analysis for adaptation strategies development among small-scale farmers in drought conditions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 67:102695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102695

Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis. IDS working paper 72. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

See, J., and Wilmsen, B. (2020). Just adaptation? Generating new vulnerabilities and shaping adaptive capacities through the politics of climate-related resettlement in a Philippine coastal city. Glob. Environ. Change 65:102188. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102188

Sina, D., Chang-Richards, A. Y., Wilkinson, S., and Potangaroa, R. (2019). What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 34, 173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.11.015

Smith, J., Johnson, L., and Williams, K. (2018). Sustainable household: a conceptual framework for integrating economic, social, and environmental sustainability across generations. J. Fam. Stud. 25, 412–430. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2018.1485086

Su, Y., Qiu, Y., Xuan, Y., Shu, Q., and Li, Z. (2023). A configuration study on rural residents’ willingness to participate in improving the rural living environment in less-developed areas-evidence from six provinces of western China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1104937. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1104937

Tang, J., Xu, Y., Ma, W., and Gao, S. (2021). Does participation in poverty alleviation programmes increase subjective well-being? Results from a survey of rural residents in Shanxi, China. Habitat Int. 118:102455. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102455

Tang, J., Xu, Y., and Qiu, H. (2022). Integration of migrants in poverty alleviation resettlement to urban China. Cities 120:103501. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103501

Thulstrup, A. W. (2015). Livelihood resilience and adaptive capacity: tracing changes in household access to capital in Central Vietnam. World Dev. 74, 352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.019

Tilt, B., and Gerkey, D. (2016). Dams and population displacement on China’s upper Mekong River: implications for social capital and social–ecological resilience. Glob. Environ. Change 36, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.008

UN-ILibrary (2025). Resettlement and the impact of climate change. New York: United Nations Publications.

Vanclay, F. (2017). Project-induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to an opportunity for devel. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 35, 3–21. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671

Wang, B., and Tang, H. (2016). Human well-being and its applications and prospects in ecology. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 32, 697–702. doi: 10.11934/j.issn.1673-4831.2016.05.002

Wilmsen, B., Webber, M., and Yuefang, D. (2011). Development for whom? Rural to urban resettlement at the three gorges dam, China. Asian Stud. Rev. 35, 21–42. doi: 10.1080/10357823.2011.552707

Xu, J., Liu, W., Li, J., Li, C., and Feldman, M. (2022). Disaster resettlement and adaptive capacity among rural households in China. Soc. Nat. Resour. 35, 245–259. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2022.2048329

Zhang, L., Xu, M., Chen, H., Li, Y., and Chen, S. (2022). Globalization, green economy and environmental challenges: state of the art review for practical implications. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:870271. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.870271

Keywords: sustainable household well-being, disaster resettlement, rural households, southern Shaanxi, China

Citation: Zhu Q, Luo X, Zhao S, Duan Y and Liu W (2025) Unraveling sustainable household well-being in disaster resettled areas: multidimensional measurement and determinants. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1653946. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1653946

Edited by:

A. Amarender Reddy, National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE), IndiaReviewed by:

Peng Jiquan, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, ChinaSonia Islam, University of the Philippines Diliman, Philippines

Hang Zhang, Lanzhou University, China

Weixin Wang, Zhejiang Gongshang University, China

Jie Xu, Xi'an University of Finance and Economics, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhu, Luo, Zhao, Duan and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Liu, bHdlaUB4YXVhdC5lZHUuY24=

Qiantao Zhu1

Qiantao Zhu1 Yuting Duan

Yuting Duan Wei Liu

Wei Liu