- 1Department of Agroindustrial Engineering, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad del Cauca, Popayán, Colombia

- 2Faculty Barberi of Engineering, Design and Applied Sciences, Universidad Icesi, Cali, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

Introduction: Coffee mucilage is an abundant by-product generated during wet coffee processing, with potential applications as a natural ingredient due to its bioactive compounds. However, its high moisture content and intrinsic instability require technological processes such as spray drying (SD) to obtain a stable powdered ingredient. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of different SD operational conditions on the physicochemical, thermal, and microstructural properties of Coffea arabica L. cv. ‘Castillo’ mucilage powder.

Methods: Coffee mucilage was obtained through enzymatic hydrolysis using commercial pectinases to facilitate polysaccharide breakdown. A mixed factorial approach was initially used to define hydrolysis conditions, followed by a central composite rotatable design that evaluated two SD factors: inlet air temperature (115.85–144.14 °C) and feed flow rate (0.23–0.66 L/h). Response variables included total phenolic content, antioxidant capacity (FRAP, ABTS, DPPH), glass transition temperature (Tg), particle size and morphology (SEM), zeta potential (PZ), hydrodynamic particle diameter (HPD), and sorption isotherms (BET and GAB).

Results: SD conditions significantly influenced the retention of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity, with higher inlet temperature promoting increased bioactive concentration compared to feed flow rate. Phenolic content ranged from 135.53 to 165.88 mg GAE/100 g. CMP exhibited Tg values between 61.09 and 62.18 °C, with no significant inter-treatment effect. SEM images revealed predominantly spherical microparticles with corrugated surfaces, ranging from 14.93 to 22.03 μm2. where lower feed flow produced smaller particle size. Sorption isotherms indicated high hygroscopic behavior, and temperature significantly affected the monolayer moisture content (Xm) and sorption energy (C).

Discussion/Conclusion: Temperature was the most influential SD factor for the preservation of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity, while feed flow primarily impacted particle size. These findings provide technological insights for optimizing SD of coffee mucilage while preserving bioactive functionality and microparticle integrity, supporting its potential use in food formulations and the valorization of coffee by-products.

1 Introduction

Colombia is currently the third largest coffee producer in the world, after countries like Brazil and Vietnam (Statista, 2024). In 2024, a 20% increase in the exportation of dry coffee beans from Colombia to other countries was reported, equivalent to approximately 13 million 60 kg sacks (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, 2024). The increase in coffee production and exportation, aimed at meeting the demand of international markets, has simultaneously led to an increase in the generation of byproducts derived from the conventional transformation process used in the Colombian coffee industry (Ministerio de Hacienda et al., 2015; Sierra-López et al., 2023).

Unlike other countries, Colombia uses a wet processing method for coffee cherries. This process consists of six main stages: harvest and selection of the fruits at their optimal maturity stage, depulping, mucilage removal, drying, milling, and commercialization of the dry, peeled beans (Ministerio de Hacienda et al., 2015).

Within these processing stages, there is a critical point of contamination during the mucilage removal stage, as during this operation, the depulped coffee beans are immersed in running water so that, through spontaneous fermentation catalyzed by the microbiota present in the fruit and processing environment, the coffee mucilage is biocatalytically degraded. This mucilage can represent between 7% and 13% of the fruit’s weight and consists primarily of water and carbohydrates, with a high presence of pectins with a high degree of methylation. This material is characterized by being a viscous liquid, either cream-colored or brown, depending on the coffee variety and the process applied to the beans, and is known for its sweet and mild taste. This material is mainly composed of carbohydrates (82–85% d.b.), proteins (6.37–9.52% d.b.), ash (2.95–4.62% d.b.), crude fiber (up to 7.30% d.b.), and lipids (0.86–1.45% d.b.) (Inés Puerta-Quintero and Ríos-Arias, 2011). Additionally, phenolic compounds are also present, with reports of up to 728 mg GAE/100 g (d.b) (Machado and de Oliveira, 2023). During the spontaneous fermentation process that seeks to remove the mucilage, the secretion of pectinolytic enzymes derived from the metabolism of bacteria and yeasts present in the process is promoted. These enzymes allow the mucilage and its polymeric network to weaken sufficiently to be washed away later (Evangelista et al., 2015; Janne Carvalho Ferreira et al., 2023).

However, once the process is completed, the waters contaminated with organic matter resulting from fermentation and mucilage residues are typically discharged directly into water sources or onto the soil of the plantation (Cortés et al., 2020), rendering coffee mucilage an unusable material for industries like the food industry. Given this, the use of exogenous enzymes in the traditional coffee fruit processing has been studied in various research works, including by the authors of this manuscript, allowing for mucilage removals of over 80% without the need for water during the mucilage removal operation (Peñuela-Martínez et al., 2011; Pardo et al., 2022).

Coffee mucilage contains bioactive compounds such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and dietary fiber, which have been associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prebiotic activities (Magoni et al., 2018; Otálora et al., 2024; Ríos-Hernández et al., 2024). These properties provide functional potential for its incorporation into the development of value-added products, including functional beverages, dietary supplements, and bakery goods, as well as acting as a natural source of hydrocolloids for textural modification in food systems (Otálora et al., 2024; Yadav et al., 2021). Therefore, stabilizing coffee mucilage through spray drying not only could extends its shelf life but also preserves these functional attributes, facilitating its possible utilization as an ingredient in the functional food market (Pyrzynska, 2024; Sierra-López et al., 2023). However, as mentioned earlier, coffee mucilage is a material with a considerably high moisture content, reaching values close to 85% (Inés Puerta-Quintero and Ríos-Arias, 2011). This high moisture content proportionally represents a high water activity, making coffee mucilage a highly perishable material, susceptible to rapid deterioration due to chemical reactions that occur when the water activity is above 0.7.

In this sense, drying strategies, such as spray drying, have been widely used to stabilize the moisture content of coffee mucilage and similar materials, achieving safe water activity levels and allowing the preservation of important compounds, such as phenolic and antioxidant compounds, which are present before the drying process, by the addition of wall materials as maltodextrin, gums, modified starch, proteins, and others (Braga et al., 2020; León-Martínez et al., 2010; Medina-Torres et al., 2019; Zotarelli et al., 2017, 2022; Roa et al., 2017; Ríos-Hernández et al., 2024). However, the existing information on the use of coffee mucilage in drying operations such as spray drying is quite limited, and it is unknown whether this material can be successfully dehydrated using such technologies and how process variables like air inlet temperature and feed flow can affect the final characteristics of the powder obtained from coffee mucilage.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to evaluate the changes that occur in coffee mucilage as a result of the spray drying conditions, seeking to expand the knowledge about the potential uses of one of the most important byproducts of the coffee industry in Colombia.

2 Methodology

2.1 Coffee mucilage enzymatic remotion

The fresh coffee cherries were supplied by Miraflores Farm, located in Tambo Cauca, Colombia. After the depulping process, the coffee beans were packed in plastic bags and transported under refrigeration conditions (4 °C) to the Agroindustrial Biotechnological Center (ABC) at Cauca University.

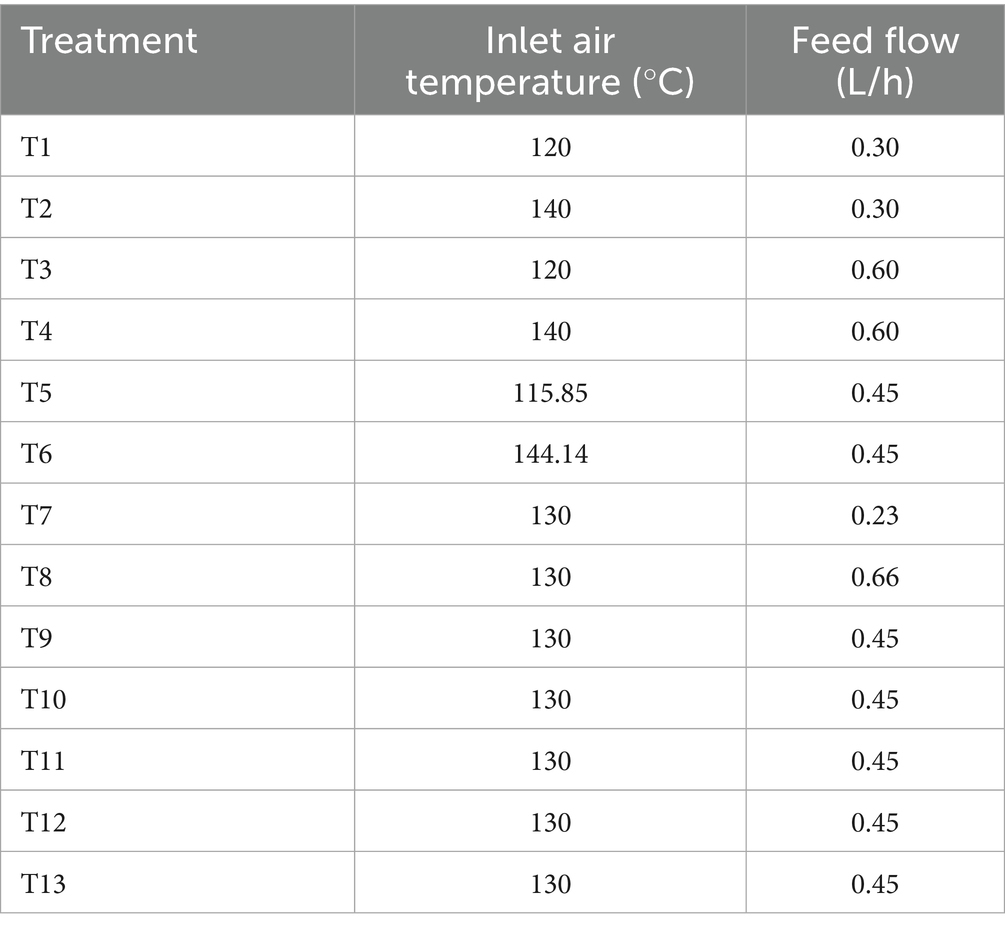

First, a factorial design was used to evaluate the best hydrolysis condition that promote the posterior remotion of coffee mucilage, this design is described in Table 1. In that way, three experimental factor was proposed, the commercial pectinolytic cocktail Naturalzyme 40XL (N40XL) obtained from proenzymas-Colombia and Esseym flavor (EF) provide by Essedielle-Francia. In second place, the concentration of enzyme added to the hydrolysis (0.012, 0.015 and 0.018% for N40XL and 0.001, 0.002 and 0.003% for EF); those concentrations were established by preliminary experimental procedures taking in count the recommended dosage of the fabricants. Finally, the hydrolysis time were evaluated (1.5 and 3.0 h). Additionally, three extra treatments were used to evaluated the influence of experimental condition on the final extraction percentage, those treatments had not the addition of any type of enzyme during the experimental process, and were named B1, B2 and B3. For the validation of this experimental 25 g of depulped coffee grains were weighed in 50 mL reactor (Falcon of 50 mL) conditioned with a perforated barrier at the bottom, this barrier allows to separate the hydrolyzed coffee mucilage by centrifugation at 1700 rpm for 5 min when the reaction time of each treatment was over.

Once the enzymatic hydrolysis parameters were established, 102 kg of coffee beans were hydrolyzed to obtain the amount of mucilage required for this investigation. This process was carried out by using the commercial pectinolytic cocktail, concentration of it and time of hydrolysis defined by the experimental design. This process took place in horizontal reactor (200 L) at constant agitation. Once the hydrolysis was complete, the coffee beans were centrifuged at 1,700 rpm for 5 min using a pilotscale centrifuge to remove the mucilage. Next, the coffee mucilage was pasteurized at 85 °C for 15 min. Then, the mucilage was placed in aseptic glass bottles (1 L) and underwent a commercial sterilization process, where it was heated to 90 °C for 30 min and subsequently cooled to 4 °C using a cool water bath. The hydrolysis conditions described above were established using experimental data developed by the authors. However, that experimental data are not reported in this manuscript as they are not the focus of this investigation. It is important to clarify that the total mucilage content (MAX) of the sample under analysis was determined by adding an amount of enzyme EF five times greater than the upper limit established in the experimental design. This process was carried out in triplicate for 30 min under the same agitation and centrifugation conditions previously described. In this way, the mucilage extraction percentage for each treatment was determined, and subsequently, these results were converted to express the amount of coffee mucilage removed relative to the total mucilage content in the depulped coffee beans used.

2.2 Spray drying process

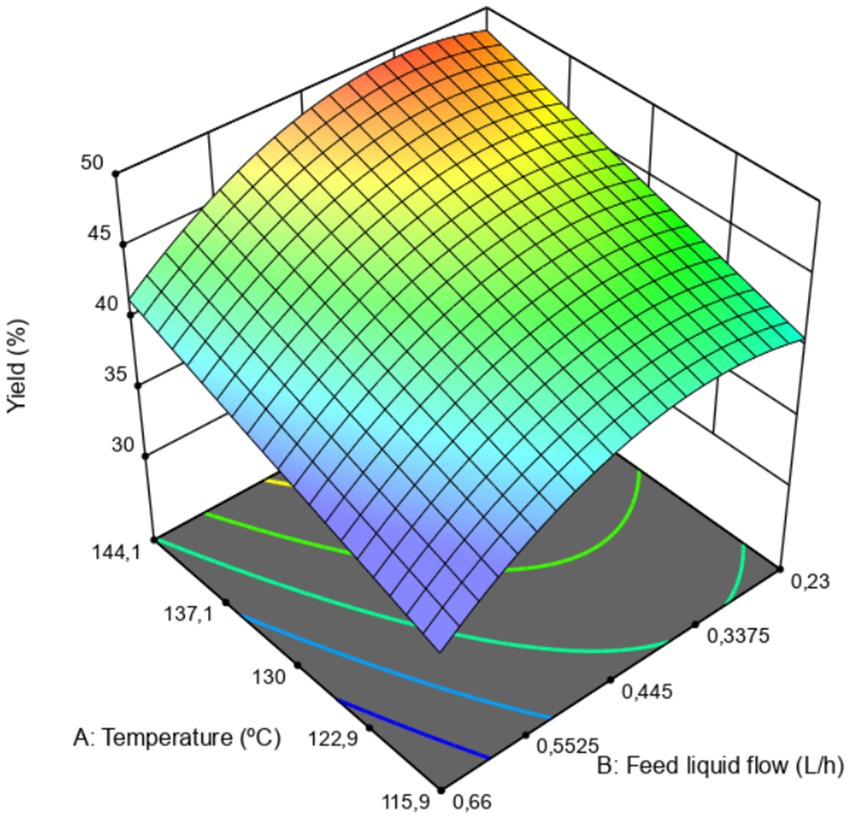

The spray drying process (SD) was carried out in a pilot-scale spray dryer equipped model SD-7 L from PSE Colombia (Process Solutions and Equipment) with a control panel that allows precise adjustment of inlet temperature, feed flow rate, and outlet airflow. The temperature control system has a precision of ±0.01 °C. The process required a total of 600 mL of coffee mucilage mixed with maltodextrin (10–12 DE) in a 1:1 ratio relative to the coffee mucilage soluble solids, until a final total soluble solid content of 20% was achieved. A central composite rotatable design, described in Table 2, was then used to evaluate the effect of the inlet air temperature (ranging from 115.85 to 144.14 °C) and the feed flow rate (ranging from 0.23 to 0.66 L/h) on the physicochemical, thermal, and microstructural characteristics of HCM by SD.

2.3 Extracts preparation to quantify phenolic compounds and the antioxidant capacity presents in CMP

The extraction of phenolic compounds present in coffee mucilage powder was determined using the method described by Cheng et al. (2019) with some modifications. First, 0.2 g of CMP were weighed into 50 mL Falcon tubes, then 8 mL of methanol solution (80%) acidified with formic acid (0.1%) were added, and the extraction was carried out under continuous agitation (250 rpm) and temperature (30 °C) for 15 min. After the extraction time had ended, the tubes were centrifuged at 3800 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was then collected and filtered through Whatman no. 1 filter paper; this first extract was named “Extract A.” The pellet, a product of the first extraction process, was resuspended with 8 mL of acetone solution (70%) acidified with formic acid (0.1%). The tubes were again maintained under continuous agitation and temperature, then centrifuged using the same conditions described previously. The supernatant was collected and named “Extract B.” Both Extract A and B were mixed, and the final volume was adjusted to 20 mL and the final extract was named Extract C. It is important to highlight that the extraction process described previously was used to prepare an extract of the hydrolyzed coffee mucilage (HCM) obtained after the enzymatic extraction process. In this case, 2.0 g of HCM were used.

2.4 Phenolic compounds quantification

The phenolic content present in CMP was determined by using the method used by Cheng et al. (2019) with some modifications. 20 μL of the previously prepared Extract C were transferred to a spectrophotometric cuvette, and 260 μL of distilled water were added. Subsequently, 26 μL of NaCO3 (7.5%) were added, and finally, 20 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent were added. The sample was mixed using a micro shaker, and the reaction was kept under constant agitation and in complete darkness for 2 h. After this time, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a VarióScan UV–Visible spectrophotometer.

2.5 Antioxidant capacity quantification

To determine the antioxidant capacity of coffee mucilage, the methodology proposed by García-Parra et al. (2021) was used, with some modifications. This method evaluates three key parameters that define the antioxidant capacity of a food: ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), antioxidant activity equivalent to ascorbic acid (ABTS), and free radical scavenging capacity (DPPH).

• Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

A total of 10 μL of the previously prepared Extract C was transferred into a spectrophotometric cuvette, followed by the addition of 30 μL of distilled water and 280 μL of FRAP reagent. The mixture was gently shaken using a micro shaker and maintained under constant agitation and complete darkness for 30 min. After this period, the absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a VarioScan UV–Visible spectrophotometer.

• Antioxidant activity determined by ABTS

A total of 10 μL of the previously prepared Extract C was transferred into a spectrophotometric cuvette, followed by the addition of 290 μL of ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) reagent. The mixture was gently shaken using a micro shaker and maintained under constant agitation and complete darkness for 30 min. After this period, the absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a VarioScan UV–Visible spectrophotometer.

• Antioxidant activity determined by DPPH

A total of 15 μL of the previously prepared Extract C was transferred into a spectrophotometric cuvette, followed by the addition of 300 μL of DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) reagent. The mixture was gently shaken using a micro shaker and maintained under constant agitation and complete darkness for 30 min. After this period, the absorbance was measured at 515 nm using a VarioScan UV–Visible spectrophotometer.

For each of the reactions described above, a corresponding calibration curve was constructed using different concentrations of analytical-grade ascorbic acid, applying the respective reagent for each method (ABTS, FRAP, and DPPH).

2.6 Determination of the final process yield

The final process yield was determined by using equation 1, were Wp corresponds to the final dry mass of powder obtained after the SD process of each treatment described on the experimental design, and Ws that corresponds to the dry mas content present on the liquid solution used for the SD process. Ws was determined by measurement of dry mater content present in the solution using a moisture balance METTLER TOLEDO HE73 (Equation 1).

2.7 Determination of the color of CMP

The methodology used by Muñoz-Pabon et al. (2022) with some modifications was used to determine color changes. Measurements were carried out using a Konica Minolta Spectrophotometer CM-5 with D65 illuminant and an observer angle of 10°. The cuvette was carefully filled to volume with each of the powder samples, and the parameters of luminosity (L) and b* (−b* indicating a bluish tendency and +b* indicating yellowish tones) were measured. Each of these parameters was analyzed individually, with the aim of verifying the existence of changes associated with the processing conditions used in spray drying.

2.8 Determination of the mean particle size and its morphology on CMP

To determine the microstructural characteristics of the powder obtained by SD, the methodology proposed by Rincón-Barón and Andrés Torres-Rodríguez (2023) with some modifications was followed. Initially, a small amount of the sample was dispersed on a sample holder, which was covered with a carbon film. The coating with gold and palladium was carried out in a Denton Vacuum desk IV ion coater for 11 min. Once the samples were coated, they were observed using a JEOL JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope. The results obtained from the observation were analyzed using the Image J software tool, where 500 measurements of the individual area of each particle observed in the photographs were taken. This information was used to construct graphs adjusted to the Poisson normal distribution, where the mean particle size values were obtained. In this way, it was possible to describe the observable morphologies and the particle size distribution in each treatment.

2.9 Determination of glass transition temperature of CMP

For this assay, a DSC 25 DISCOVERY SERIES differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments) was used, equipped with a Refrigerated Cooling System (RCS) and operating with nitrogen gas at 150 mL/min. The equipment features a temperature control precision of ± 0.01 °C. Calibration was performed using indium (Tm = 156.6 °C), with helium as the purge gas at a constant flow of 25 mL/min. Approximately 0.5 mg of each sample was weighed into aluminum heating pans. The samples were initially cooled to −20 °C and then heated to 120 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. This cycle was then repeated in reverse to confirm the Tg values.

2.10 Evaluation of the behavior of CMP dispersed in water at different pH values

According to the results obtained in the previous sections of the manuscript, one treatment was selected based on the maximization of phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity measured by the FRAP method, and, finally, the final yield of the SD process. To achieve this objective, a numerical optimization process was carried out. Once the predicted responses were obtained, the desirability of each treatment was calculated to select the treatment that best met the objective of the optimization process.

Once the treatment was selected, the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential were determined using the method described by Zotarelli et al. (2017, 2022). First, a solution containing 0.1% CMP was prepared using sodium phosphate buffer solutions (0.01 M) ranging from pH 3.0 to 9.0. The samples were then measured in quintuplicate using an Anton Paar Litesizer 500, under the conditions recommended by the software.

2.11 Water absorption isotherms of CMP

The methodology proposed by Domínguez-Chávez et al. (2023) with some modifications was used. Initially, 0.5 g of the sample selected in section 3.10 were weighed on a Vapor Sorption Analyzer VSA, Aqualab; subsequently, the analysis conditions on the equipment were adjusted as follows: aw ranging from 0.25 to 0.75 and temperatures of 25, 35, and 45 °C. An isotherm was obtained at each set temperature. The first mathematical model used, due to its ability to fit experimental data, was the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model, described in Equation 2, for values of aw ranging between 0.1 and 0.6. Additionally, the Guggenheim-Anderson-de Boer (GAB) mathematical model, described in Equation 3, was also used to contrast the results, modeling the data for values of aw ranging from 0.0 to 0.95.

Where M is the equilibrium moisture content, M₀ and Xm are the monolayer moisture content, aw is the water activity in the moisture content, C is the absorption constant, and K is the interaction constant in upper layers.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Results of the enzymatic extraction of coffee mucilage and selection of hydrolysis parameters

The “MAX” treatment, as described in the methodology, determined that mucilage accounted for 24.34% ± 0.0172 of the initial coffee mass, which was set as 100% mucilage content for reference. Table 3 describes the results of the experimental design, in first place treatment B1, involving immediate centrifugation after depulping, showed a removal of 27.5% ± 0.012, attributed solely to mechanical action and fruit characteristics. Reactors B2 and B3 reached mucilage removal rates of 31.9% ± 0.006 and 35.7% ± 0.011 after 1.5 and 3.0 h, respectively, results that are lower than the once obtained by using the lowest enzyme concentration in the design. The increased removal observed in B2 and B3 may be due to grain agitation weakening the mesocarp’s polymeric layer. Additionally, since the beans were not disinfected, the native microbiota (yeasts and pectinolytic bacteria) remained active throughout the process, contributing to mucilage degradation, as occurs in traditional Colombian fermentation practices (Sierra-López et al., 2023). In contrast, the mucilage extraction percentages obtained in the treatments where enzymes were applied, relative to the total mucilage content in the coffee beans, ranged from 43.0% ± 0.023 to 77.5% ± 0.023. The latter value corresponds to treatment number 12, which used the highest concentration of enzyme N40XL and a 3 h reaction time prior to initiating mechanical separation. However, comparing this treatment with treatment number 11 (75.6% ± 0.002), no statistically significant difference was observed; thus, this process condition was selected to carry out the hydrolysis of the depulped coffee beans obtained from the “Mira Flores” farm. Finally, the MAX concentration of mucilage present in the102 kg of coffee was 22.37%, This result is lower than the estimated total mucilage content present in the beans used to carry out the previously described experimental design. This behavior may be attributed to differences in harvest timing, agroclimatic conditions, agronomic management, postharvest handling, fruit ripeness stage, among other factors that can affect the mucilage content (Avallone et al., 2000; Inés Puerta-Quintero and Ríos-Arias, 2011).

Therefore, hydrolysis process of 102 kg of coffee grains and its posterior centrifugation, allowed to obtain 19.07 kg of liquid mucilage, corresponding to a final removal efficiency of 83.42% ± 0.045. The use of a pilot-scale centrifuge likely enhanced mucilage extraction due to its higher operational power compared to the extraction percentage of treatment 11 of the experimental design. These results are comparable to those reported by Tai et al. (2014), who achieved complete detachment of coffee mucilage after 3 h of enzymatic hydrolysis at room temperature, without requiring water for separation.

3.2 Effect of the SD conditions on the phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of CMP

Spray drying is a process characterized by high operating temperatures and short residence times within the equipment. This type of technology has been widely used in various studies as it largely helps preserve the bioactive compounds present in the material (Hernández-Nava et al., 2020; León-Martínez et al., 2010; Medina-Torres et al., 2016; Zotarelli et al., 2017).

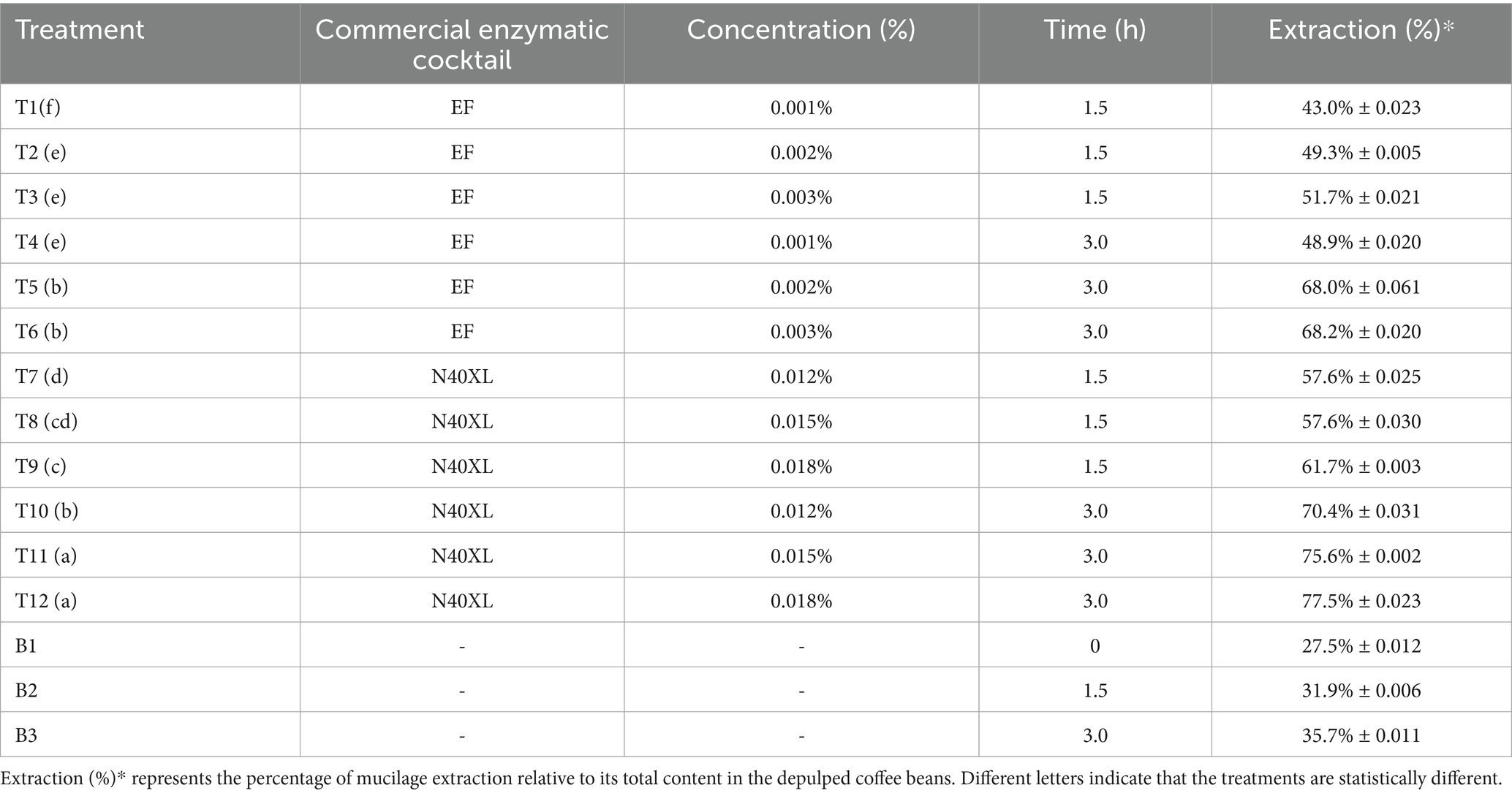

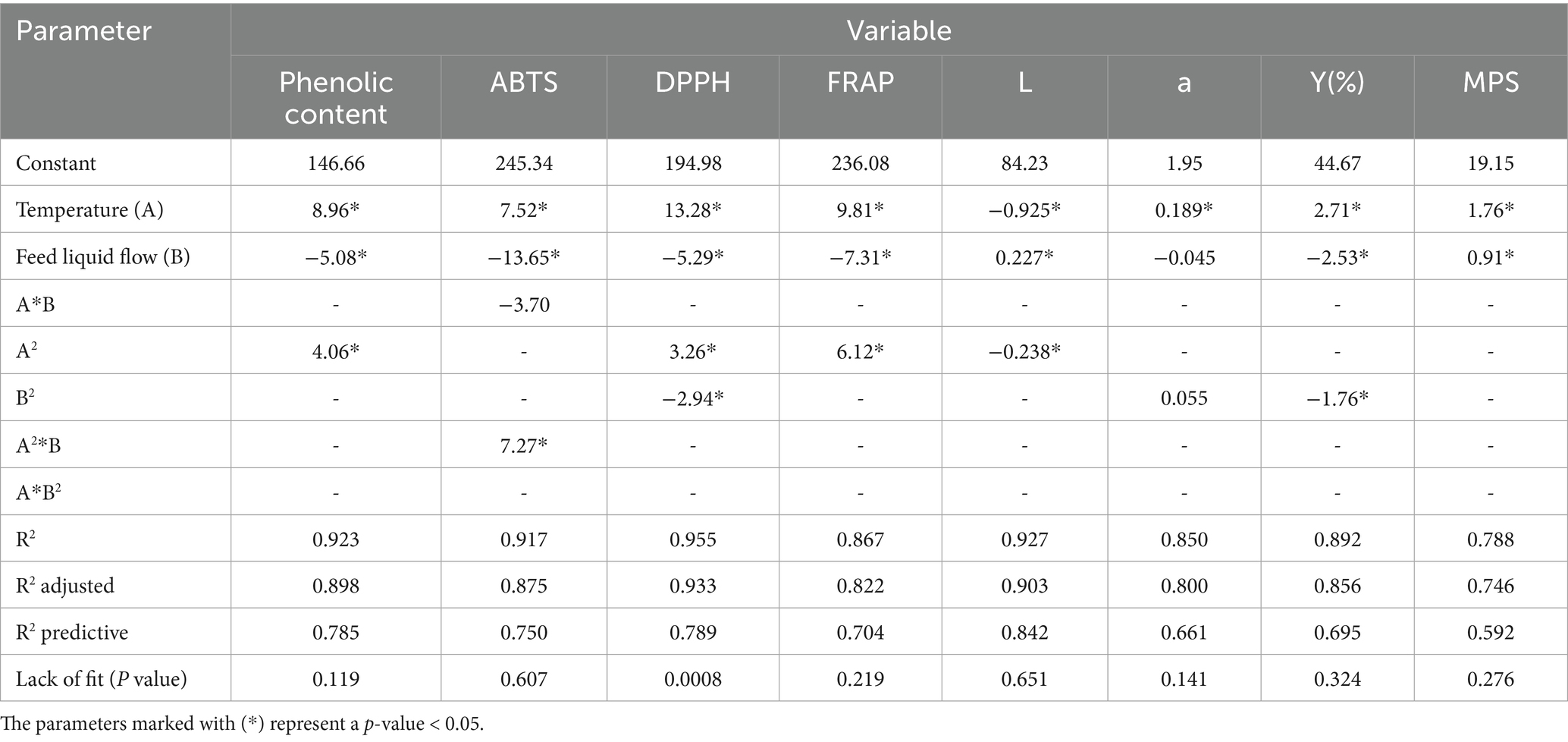

In the case of the dehydrated coffee mucilage samples, the phenolic content and antioxidant capacity reported in Table 4 were significantly affected by both factors, Inlet air temperature and Feed flow (p < 0.05). However, Inlet air temperature had a greater relevance in the variability of the results obtained. The final mathematical model for each variable is described in Table 3.

Based on the information presented in Table 4, where the phenolic content and antioxidant capacity for coffee mucilage are reported, and highlighting that the formulation made before the drying process is in a 1:1 proportion in terms of soluble solids between the mucilage and the wall material (maltodextrin), which theoretically represents a dilution factor of 0.5 for the bioactive compounds originally present in HCM. Analyzing the information described in Figure 1 and Table 4, it can be observed that in all treatments, the results exceeded the theoretical phenolic content and the theoretical final antioxidant capacity. Additionally, as the process temperature increases, the phenolic content and the final antioxidant activity also significantly increases; this effect is enhanced when the feed flow decreases, approaching the lower limit of the experimental design (0.23 L/h).

Figure 1. Response surface of phenolic content and antioxidant capacity in CMP. Phenolic content expressed as mg equivalents of gallic acid per 100 g of CMP in dry basis (mg GAE/100 g) (A); Antioxidant capacity measured by ABTS (B); Antioxidant capacity measured by FRAP (C); Antioxidant capacity measured by DPPH (D). The results of antioxidant capacity are expressed as mg equivalents of ascorbic acid per 100 g of CMP in dry basis (mg AAE/100 g).

This behavior is similar to that reported by Baysan et al. (2019), Chong and Wong (2017), and Zhang et al. (2020), who described an increase in phenolic compound content as the dehydration process temperature increased in the production of chicozapote, cranberry, and propolis encapsulated powders, respectively.

Firstly, Chong and Wong (2017) suggests that this increase could be related to the rapid dehydration of the material caused by the high drying temperatures; this reduces the residence time and exposure of the particles in the drying chamber as the temperature increases. Thus, the material flows more quickly through the system to cooler areas of the equipment, where these compounds may not be significantly affected. On the other hand, Chong and Wong (2017), Mishra et al. (2014), and Vargas et al. (2024) argue that high temperatures could promote the depolymerization and synthesis of phenolic compounds in dehydrated samples.

However, Zhang et al. (2020) clarifies that this depolymerization and synthesis phenomenon depends on the type of phenolic compounds present in the sample, as some, such as flavonoids, may exhibit high thermal stability. In this context, certain phenolic compounds may undergo changes in their conformation, which could increase their solubility in certain solvents and even enhance their reactivity with the reagent used for the quantification, potentially resulting in a higher total phenolic content measured by the Folin Ciocalteu method in the obtained powders (Robert et al., 2015; Vargas et al., 2024). Therefore, the use of high process temperatures could promote the formation of Maillard reaction derivatives, which have been investigated for their ability to exhibit antioxidant activity after the drying process (Horuz et al., 2012). Likewise, the molecules derived from the Maillard reaction could act as interferents during the quantification of phenols with the Folin Ciocalteu reagent. However, Do and Nguyen (2018) clarify that although in some cases the processing temperature may positively influence the antioxidant response of spray dried materials, there is a thermal limit beyond which this behavior may be reversed, possibly promoting a reduction in phenolic compounds content and antioxidant molecules when the drying temperature its above 140 °C.

On the other hand, it is observed that the feed flow also influences the final phenolic compound content and final antioxidant capacity in the powder. However, this effect is the inverse of the one observed with the temperature factor, as a lower feed flow results in a higher polyphenol content. This phenomenon could be directly related to the dehydration rate, as lower feed flows generate finer droplets during the atomization stage in the drying chamber crown, compared to larger droplets produced when the feed flow is higher (Miguel, 2013). Finer droplets facilitate more efficient and homogeneous dehydration (Tontul and Topuz, 2017), which could help preserve a higher phenolic compound content and its final antioxidant capacity in the final powder due to the possible reduction in the residence time of the mucilage powder particles inside the drying chamber.

3.3 Effect of the SD conditions on the final yield of the process

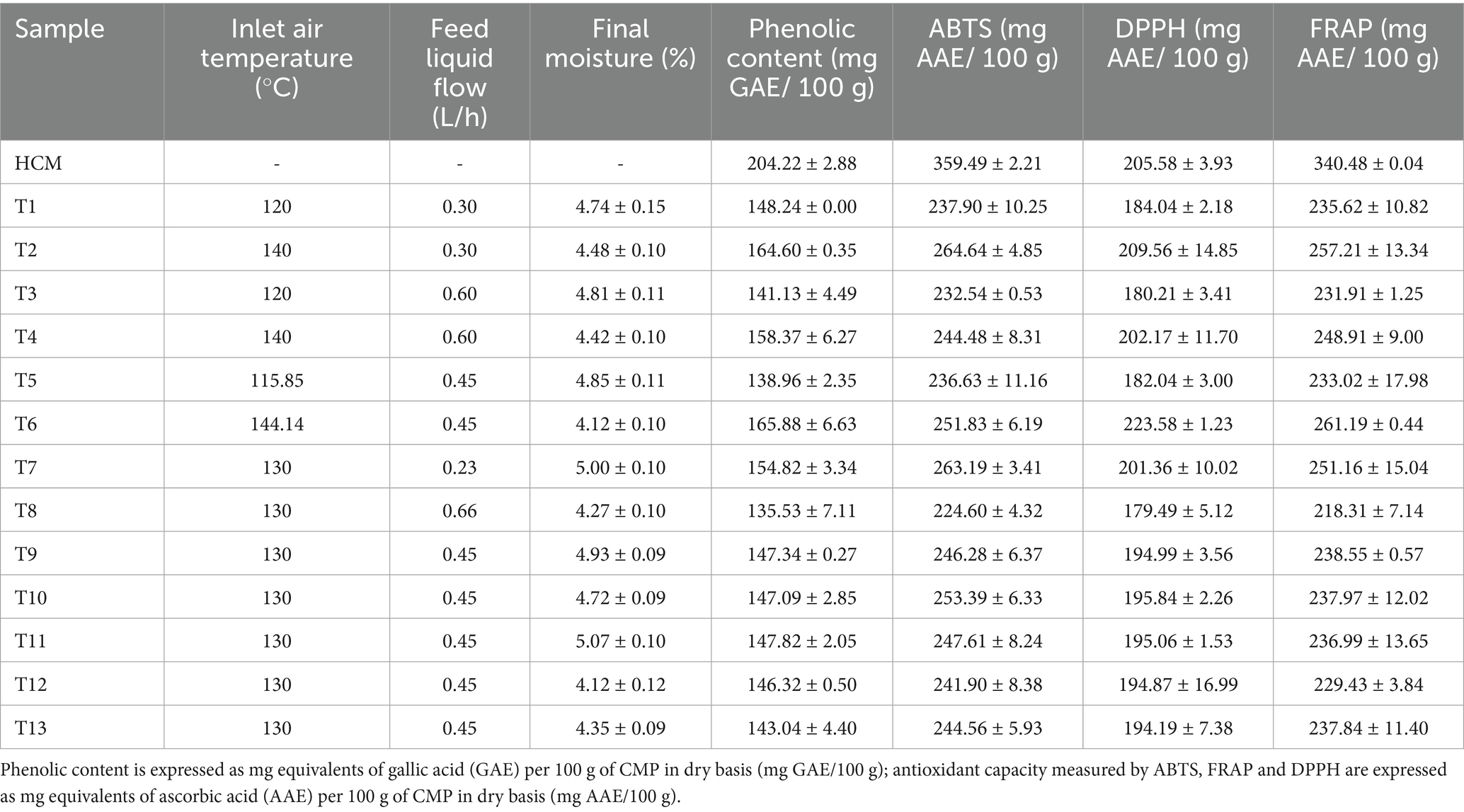

In the case of spray drying of coffee mucilage, the final yield achieved ranged from 37% to 50%. Additionally, Table 5 shows that the statistical model indicated that both the process temperature and the feed flow had a significant effect on the response variable. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 89.18%, indicating that the model explained a high proportion of the variance in the experimental data. Furthermore, the lack-of-fit was not significant, suggesting that the model adequately described the experimental observations.

Table 5. Mathematical models obtained from the statistical analysis of the central composite design used.

Spray dehydration of coffee mucilage, like fruit pulps with similar physicochemical characteristics, presented adhesion to the walls of the equipment in preliminary tests, where attempts were made to dehydrate the material without the presence of a wall material, such as maltodextrin (Zotarelli et al., 2017, 2022). For this reason, it was necessary to add the wall material (Maltodextrin 10–12 DE) in order to improve the thermal characteristics of the material, aiming to obtain a higher product yield at the end of the process (Fazaeli et al., 2012; León-Martínez et al., 2010; Tonon et al., 2008).

According to Figure 2, higher process temperatures during dehydration combined with slow feed flows resulted in a higher yield at the end of the process. As mentioned in previous sections, the combination of these two conditions within the equipment can favor a much faster and more efficient dehydration compared to processes carried out under lower drying temperatures and higher feed flows, conditions that could cause an increase in humidity within this space as a result of excess water vapor inside the system (León-Martínez et al., 2010; Tonon et al., 2008; Tontul and Topuz, 2017). In this regard, the conditions that maximized the yield could promote rapid dehydration of the material, improving mass transfer processes from inside the atomized droplets, possibly preventing the material from adhering to the equipment walls and reducing the final amount of powder collected in the cyclone collector of the drying equipment (Fazaeli et al., 2012). Similarly, establishing a condition of slow feed flow could favor the formation of small droplets, which dehydrate quickly compared to larger droplets that may form when the feed flow increases. These larger droplets could undergo slower dehydration, allowing them to adhere to the drying chamber walls during the drying process and becoming adhesion points for particles still inside the drying chamber, thus reducing the production yield at the end of the process.

Authors such as Fazaeli et al. (2012), León-Martínez et al. (2010), Tonon et al. (2008), Tontul and Topuz (2017), and Vivek et al. (2021) state in their research that increasing the feed flow and reducing the process temperature decreases the production yield in spray dryers due to the adhesion of particles to the internal walls of the equipment.

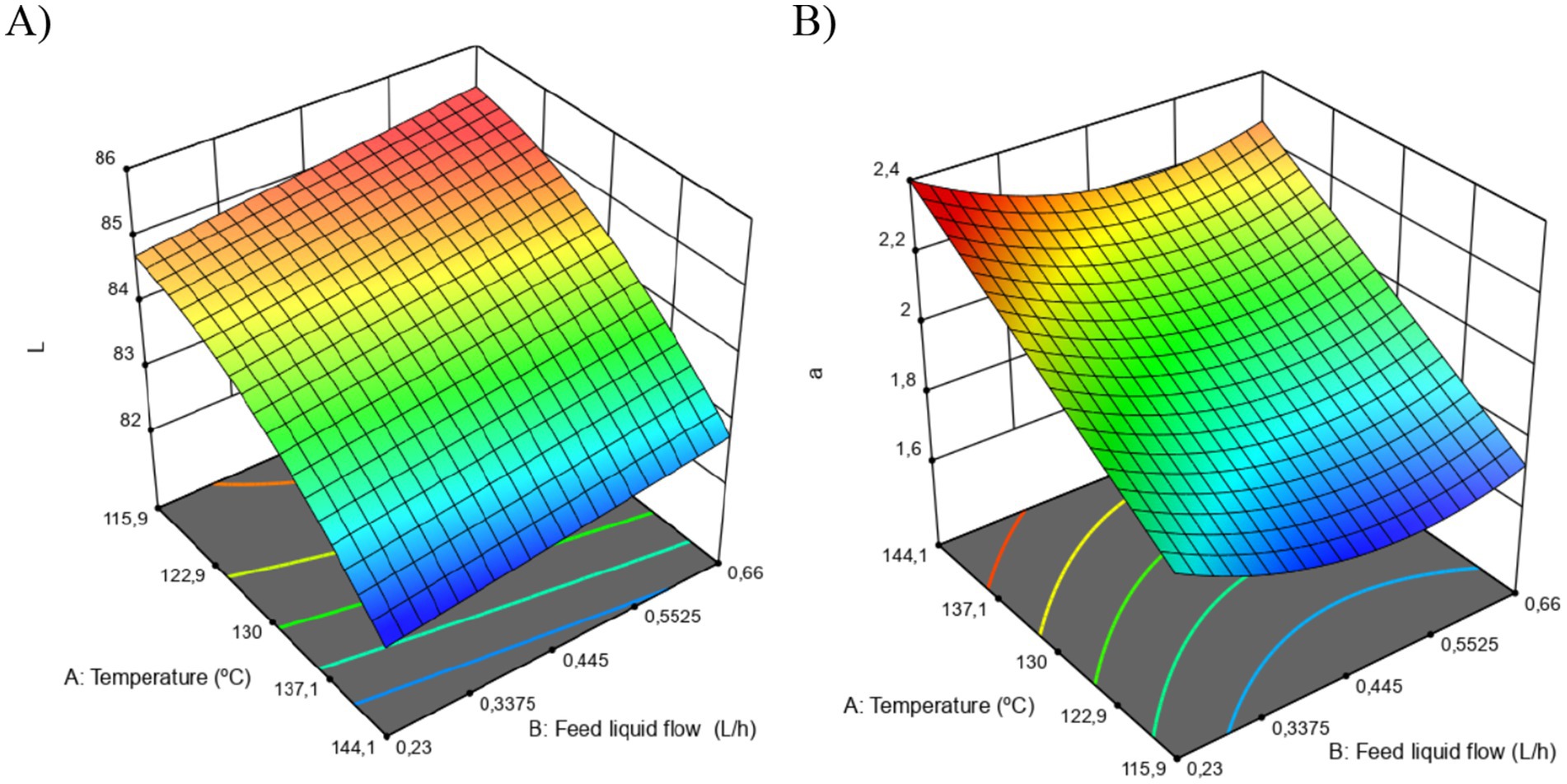

3.4 Effect of the SD conditions on the color of the CMP

The results of this test are presented in Figure 3. First, the L values (luminosity) ranged from 82.25 to 84.98, showing a significant effect of both experimental factors (temperature and feed flow). The mathematical model showed an R2 of 92.70% with an no significant lack of fit.

Figure 3. Color change in CMP obtained by SD. Change on Luminosity of the sample (A); changes on ±a color component (B).

On the other hand, the +a values (green to red tones) ranged from 1.68 to 2.32, where only the temperature factor had a significant effect on this variable. In this case, the mathematical model reached an R2 fit of 85.00%, with no evidence of a significant lack of fit.

Firstly, the process temperature had a greater statistical relevance on these response variables, showing a slight reduction in L towards slightly darker colors and an increase in +a values towards more reddish colors according to the CIELAB scale. This was observed in samples dehydrated at process temperatures close to the upper limit of the experimental design (144.14 °C). Authors such as Ferrari et al. (2012) state that these changes may be associated with the interaction of sugars present in fruit juices with other compounds, such as proteins, during the Maillard reaction. These types of reactions can lead to a darkening of the material’s color, causing the luminosity (L) values to be lower compared to processes carried out under low temperature conditions during drying. However, in some cases, this behavior is reversed depending on the type of material being dehydrated and the concentration of the wall material used. In some cases, high inclusion levels of wall materials such as maltodextrin can favor the production of much lighter powders (George et al., 2023; Pui et al., 2020; Villegas-Santiago et al., 2020).

3.5 Effect of the SD conditions on the particle mean size and microstructural characteristics

According to the photographs captured of the obtained mucilage powders, Figure 4B that corresponds to treatment 4, shows that most of the particles are spherical and have a corrugated surface; this could be associated with rapid dehydration of the mucilage droplets and their subsequent collapse due to internal tensions in the particle. In general, the mucilage powders have a morphology similar to the reports in the scientific literature (Pui and Saleena, 2022).

Figure 4. Results of mean particle size (MPS) of CMP and its morphology. Response surface of mean particle size change (A); SEM photography of CMP (B).

On the other hand, the results analyzed as mean particle size values ranged from 14.93 to 22.03 (μm2); these are within the normal ranges for powders obtained through spray drying (Vargas et al., 2024). These results had an R2 of 78.80% with a linear model (see Table 5). In addition, statistical analysis showed that both process temperature and feed flow had significant effects on the particle size distribution of the obtained mucilage powders. The results are described in Figure 4.

Initially, it can be observed that, under high feed flow conditions, the particle size increases compared to treatments where this process condition was reversed. As mentioned previously, processing plant materials like coffee mucilage with the inclusion of a wall material such as maltodextrin, under slow flow conditions, can promote the atomization of smaller droplets, resulting in much smaller powder particles (Pui and Saleena, 2022).

On the other hand, in Figure 4A, it is observed that as the process temperature increases, there is a noticeable increase in the size of the obtained particles. Authors such as Dantas et al. (2018), Ferrari et al. (2012), and Tonon et al. (2008) mention that drying conditions at high temperatures can increase the dehydration rate, rapidly evaporating the water inside the droplets. This phenomenon could promote the formation of a crust on the outer wall of the droplet, slowing the release of water vapor and causing the droplet to expand like a balloon. Once the water is evaporated, the rigid crust initially formed could weaken as a result of a reduction in internal pressure, which would likely result in larger particles with a corrugated surface (Figure 4B) (Ferrari et al., 2012).

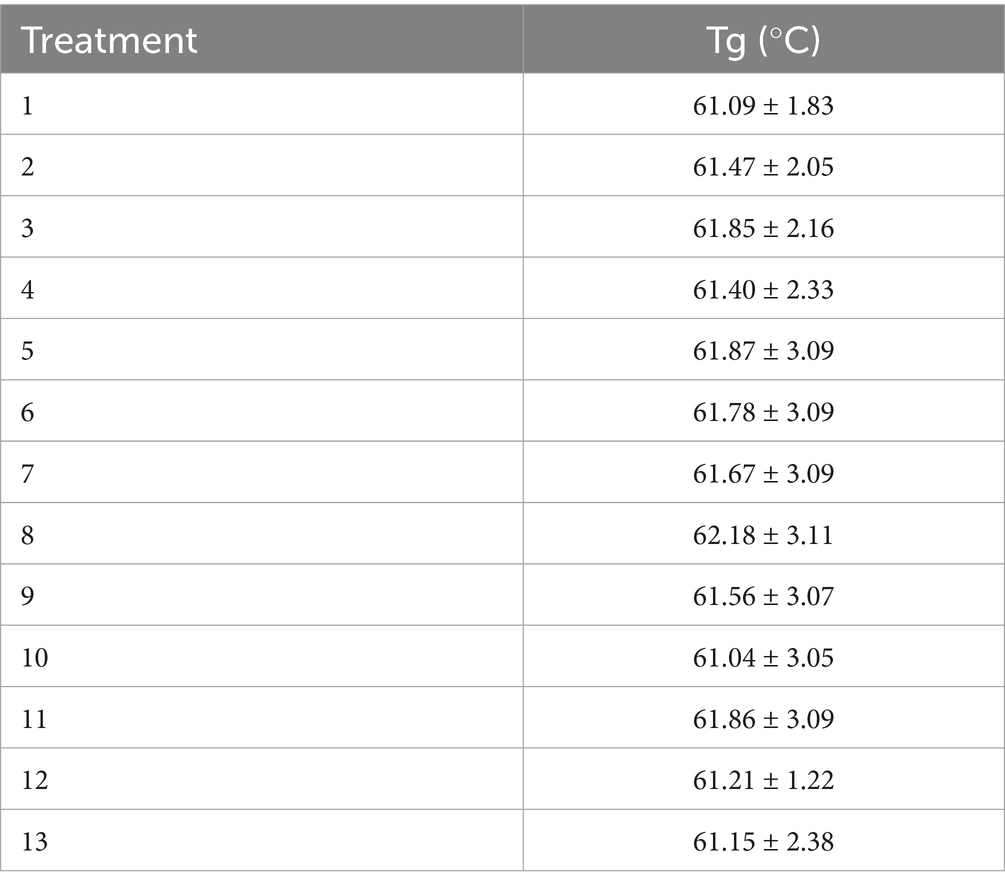

3.6 Effect of the SD conditions on the glass transition temperature of CMP

In the case of coffee mucilage powder obtained by SD, the Tg values measured by DSC are reported in Table 6. Initially, it is important to highlight that the raw materials separately have considerably different Tg values, with 35.80 ± 1.790 °C for HCM and 138.44 ± 5.537 °C for maltodextrin (MD). On the other hand, in the analysis of the points of the experimental design used to evaluate the effect of drying conditions on the final characteristics of the CMP, it was observed that the Tg values ranged from 61.09 ± 1.83 to 62.18 ± 3.11 °C, with no statistically significant differences observed between treatments.

Authors such as Shrestha et al. (2007) report that the inclusion of maltodextrin in a 1:1 ratio with respect to the soluble solids in fruit juice results in a powder material with a Tg value of 66.40 °C, noting that this value significantly increased as the maltodextrin inclusion level increased (Shrestha et al., 2007; Vargas et al., 2024). However, in the case of coffee mucilage, the goal was to obtain a thermally stable powder matrix, with a mucilage inclusion level corresponding to at least 50% of the final product composition. In this sense, the behavior of the treatments analyzed could be directly related to the fact that each one was formulated under the same 1:1 ratio of soluble solids provided by HCM and MD, allowing the resulting powder from the drying process to have a considerably higher Tg value compared to the characterization of HCM alone, without the drying process conditions having any significant relevance.

3.7 Statistical analysis of the desirability observed in the spray dry treatments

Initially, according to the method described in the book published by Gutiérrez Pulido and de la Vara Salazar (2008), the observed desirability (do) of each treatment was calculated based on the degree of achievement of the optimization objectives for each response variable, using the StatGraphics Centurion 19 statistical analysis software. This information is reported in Table 7. Gutiérrez Pulido and de la Vara Salazar (2008) state in their book that (do) can vary between 0 and 1, with the latter being the maximum desirable value for a response variable. As these values approach 1, it means that the objectives of the optimization are met to a greater extent, i.e., the results obtained under the process conditions of treatments yielding (do) values close to 1 closely resemble the responses resulting from the optimized calculation.

Table 7. Desirability calculated for each treatment based on the achievement of the optimization objectives.

Considering the above, and analyzing the information reported in Tables 7, 8, it is observed that the highest (do) value was obtained for the responses of treatment 2 (T2), which was equal to 0.954. This translates to a 95.4% similarity between the results obtained under the operating conditions described in T2 and the responses obtained from the optimization. On the other hand, treatment 6 (T6) had an observed desirability (do) of 0.878; however, this treatment yielded a lower result in the percentage of final yield achieved. This translates to 87.8% achievement of the optimization objectives for the corresponding response variable; compared to T2, this result is considerably lower, as the latter treatment obtained a desirability close to 100%.

In this regard, treatment 2 (T2) was selected as the process condition that allowed for the maximization of phenolic compound content, antioxidant capacity, and the final yield of the coffee mucilage drying process. This treatment was used to perform the Z Potential, hydrodynamic diameter and water sorption isotherms analysis.

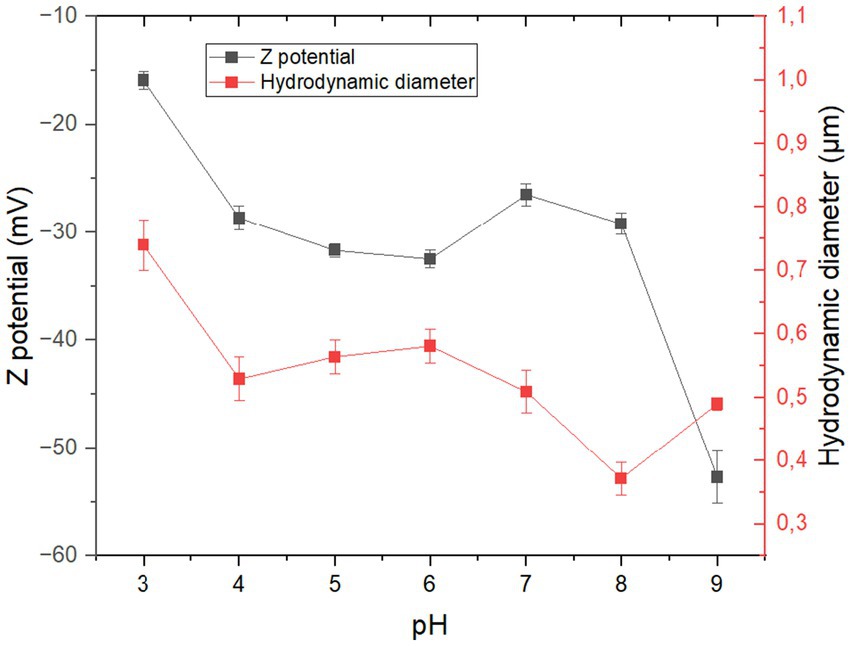

3.8 Evaluation of the effect of pH on the Z potential and hydrodynamic particle diameter (HPD) of the mucilage powder

The results of the analysis of the effect of pH on the Z potential and hydrodynamic particle size are reported in Figure 5. First, the Z potential expressed in mV was −15.92; −28.65; −31.68; −32.48; −26.48; −29.20; and −52.72 for pH values of 3.0; 4.0; 5.0; 6.0; 7.0; 8.0; and 9.0, respectively. On the other hand, the hydrodynamic particle diameter expressed in μm was 0.74; 0.52; 0.56; 0.58; 0.51; 0.37; and 0.49 for pH values of 3.0; 4.0; 5.0; 6.0; 7.0; 8.0; and 9.0, respectively.

Initially, when the pH of the dispersing medium was 3.0, it was observed that the Z potential was −15.92 mV. This represents instability in the dispersed phase, likely due to the possible aggregation of particles with similar surface charges (Joshi et al., 2018; Koetz and Kosmella, 2007). Additionally, it is observed that the hydrodynamic particle diameter (DHP) under this pH condition was 0.74 μm, a result that is higher than the values obtained at pH 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0, where the Z potential increased in magnitude to values close to −30 mV (Joshi et al., 2018). These values are associated with the threshold that marks the onset of particle stability. It is in this region that a greater degree of repulsion between the particles occurs, and consequently, the HPD could decrease considerably.

Finally, when the pH was 9.0, the results again show an increase in the magnitude of the Z potential and a reduction in HPD; this behavior is much more evident at pH 9.0, where the Z potential was −52.72, which can be related to a high degree of repulsion between the particles dispersed in the aqueous medium.

In this sense, coffee mucilage powder, obtained by spray drying, presents reduced stability in aqueous media where the pH is between 4.0 and 8.0; however, at pH 3.0, the powder particles could tend to aggregate and separate through the formation of phases or flocs. This phenomenon is undesirable if the material were to be used in the formulation of foods with pH values close to 3.0 like some fruit juices. Finally, the mucilage powder showed great stability at pH values above 8.0; however, it is uncommon to find foods in such an alkaline range in the food industry. Tough, the values of Z potential observed at pH 5 and 6 represents a medium stability stage, that could represent the possibility to use this raw material in the development and formulation of new foods or products that aim to leverage residual biomass from the major agroindustries in the department and, on a larger scale, from Colombia. This mean that there is a new area of exploration to promote the increase of the stability of the powder dispersed in aqueous media in that pH range.

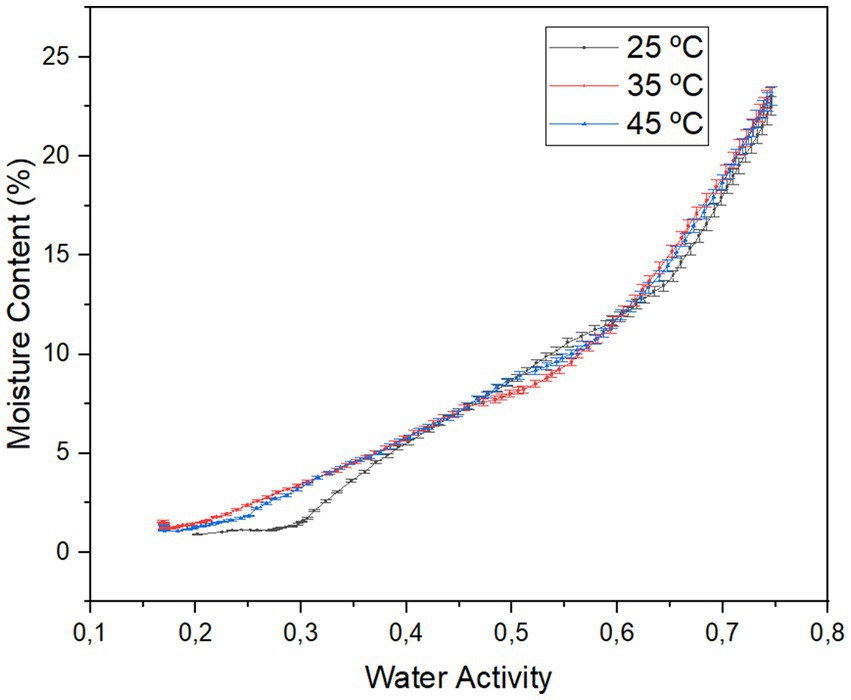

3.9 Water absorption isotherms of CMP

The results of constructing three water absorption isotherms for coffee mucilage powder and their respective mathematical modeling are recorded in Figure 6 and Table 9. Each of them was adjusted using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Guggenheim-Anderson-de Boer (GAB) mathematical models, using the analysis intervals described in the methodology. The modeling results are reported in Table 9, where all the generated isotherms showed an R2 above 94%. These results showed statistically significant differences among them.

Table 9. Results of the mathematical modeling using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Guggenheim-Anderson-de Boer (GAB) models.

Initially, in Figure 6, a slight plateau phase is observed in aw values lower than 0.28 when the test temperature was 25 °C, which contrasts with the results obtained at 35 and 45 °C. This could be understood as an increase in water activity without a significant gain in moisture. This behavior describes the way carbohydrates hydrate, where water activity (Wa) may remain constant at low values, allowing surrounding water to only interact with polar sites available on the particle surface. However, as these available binding sites become saturated, an increase in aw could occur, causing these carbohydrates to begin dissolving, allowing moisture content to increase rapidly (León-Martínez et al., 2010).

However, in all the isotherms, it is observed that there is an increase in moisture content in the Wa range between 0 and 0.5. This translates to a high hygroscopicity of the mucilage powder; this affinity for water could promote rapid material deterioration, causing clumping and darkening due to the rapid moisture gain (Domínguez-Chávez et al., 2023).

On the other hand, if we analyze the information described in Table 9, it can be seen that the results obtained for monolayer moisture content (Xm), an important parameter for evaluating material stability, as it defines the moisture content at which a food is most stable against chemical deterioration (Braga et al., 2020), ranged from 7.667 ± 0.383 to 11.23 ± 0.561 for the BET model, and from 10.040 ± 0.502 to 13.300 ± 0.665 for the GAB model. These values showed statistically significant differences between them.

First, when the test temperature was 25 °C, higher values for Xm were obtained, being 11.23 ± 0.561 (BET) and 13.300 ± 0.665 (GAB); these values decreased considerably when the isotherms were evaluated at higher temperatures, reaching 7.667 ± 0.383 and 10.040 ± 0.502, respectively, for each model.

Authors such as Junior et al. (2024) and León-Martínez et al. (2010) argue that when the test temperature increases, there may be a reduction in the number of active sites on the material surface, which is why Xm decreases as the environment warms. Since the increase in temperature can modify the mobility of water between the vapor phase and the absorbent phase, leading to a reduction in Xm (Junior et al., 2024). This idea is reinforced when analyzing the values of C, a parameter that describes the water absorption energy in the monolayer (Domínguez-Chávez et al., 2023) and indicates how strongly water binds to the active sites on the material surface.

In Table 9, it can be observed that the values of C ranged from 0.561 ± 0.028 to 1.081 ± 0.054 for the BET model and from 0.617 ± 0.030 to 0.768 ± 0.038 for the GAB model. It is clear that C increases as the test temperature increases in both mathematical models; which could be interpreted as an increased difficulty for water to bind to the active sites on the monolayer and remain stable. Braga et al. (2020) and Junior et al. (2024) describe that this phenomenon can be related to a decrease in the material’s affinity for water as the test temperature increases, making it more stable against chemical reactions that could occur as aw increases. Finally, the values obtained for K, in the GAB mathematical model, which describes the stability of water in the layers above the monolayer, ranged from 0.895 ± 0.044 to 0.961 ± 0.048, and no statistically significant differences were observed among them. However, when K is close to 1, it is associated with highly hygroscopic materials, since the layers above the monolayer behave similarly to the monolayer, allowing the material to interact strongly with surrounding water (Junior et al., 2024). In this sense, coffee mucilage powder is highly hygroscopic, it could be related due to presence of low molecular weight sugars, making it prone to moisture absorption and deterioration during storage. To counteract this, high molecular weight carrier agents such as maltodextrin, natural gums, and proteins are commonly used during spray drying (Sarabandi et al., 2018). These materials cloud increase the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the mixture, reducing stickiness and improving powder stability. Additionally, they form a protective matrix around the particles, isolating them from environmental moisture. The use of such coatings enhances flowability, reduces hygroscopicity, and extends the shelf life of the powder. This strategy has been widely applied in similar matrices rich in sugars and bioactive compounds. Overall, these encapsulating agents enable the production of more stable and higher quality powders (Lee et al., 2018).

4 Conclusion

The spray drying process applied to coffee mucilage demonstrated that high inlet temperatures combined with low feed flow rates favor the preservation and, in some cases, the enhancement of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity, surpassing the theoretically expected values. These conditions also led to the highest process yield. However, although elevated temperatures were beneficial under the conditions studied, further research is needed to establish the upper thermal limits to prevent possible degradation of sensitive compounds in other matrices or formulations. Despite the use of maltodextrin to increase the glass transition temperature of the resulting powder, the material remains highly hygroscopic and exhibits a strong affinity for moisture. Therefore, the implementation of packaging systems with very low water vapor permeability is essential to ensure stability during storage. Complementary stabilization strategies, such as the use of high molecular weight biopolymers or hydrophobic coatings, may further reduce moisture sensitivity and extend shelf life. In terms of colloidal behavior, the powder exhibited moderate stability across most of the tested pH range, with good dispersion stability observed only at pH values above 8, based on Zeta potential and hydrodynamic particle diameter analyses. These findings suggest potential applicability in alkaline formulations; however, additional studies are required to assess its performance in real beverage systems, including ingredient interactions and storage-related stability.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JR: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JH: Investigation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DR-A: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. VR-B: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. GT: Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universidad del Cauca and Universidad Icesi for providing the facilities and institutional support to carry out this research. We also express our gratitude to the researchers and collaborators who contributed to the development of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Avallone, S., Guiraud, J.-P., Guyot, B., Olguin, E., and Brillouet, J.-M. (2000). Polysaccharide constituents of coffee-bean mucilage. 1308 J. Food Sci. 65, 1308–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb10602.x

Baysan, U., Elmas, F., and Koç, M. (2019). The effect of spray drying conditions on physicochemical properties of encapsulated propolis powder. J. Food Process Eng. 42, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13024

Braga, V., Guidi, L. R., de Santana, R. C., and Zotarelli, M. F. (2020). Production and characterization of pineapple-mint juice by spray drying. Powder Technol. 375, 409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2020.08.012

Cheng, K., Dong, W., Long, Y., Zhao, J., Hu, R., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). Evaluation of the impact of different drying methods on the phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and in vitro digestion of green coffee beans. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 2543–2548. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.948

Chong, S. Y., and Wong, C. W. (2017). Effect of spray dryer inlet temperature and maltodextrin concentration on colour profile and total phenolic content of sapodilla (Manilkara zapota) powder. J. Homep. 24, 1084–1095. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326675842_Effect_of_spray_dryer_inlet_temperature_and_maltodextrin_concentration_on_colour_profile_and_total_phenolic_content_of_Sapodilla_Manilkara_zapota_powder

Cortés, Y. F., Rodríguez, K. D. S., and Marín, L. A. V. (2020). Environmental impacts from coffee production and to the sustainable use of the waste generated. Produccion y Limpia 15, 93–110. doi: 10.22507/PML.V15N1A7

Dantas, D., Pasquali, M. A., Cavalcanti-Mata, M., Duarte, M. E., and Lisboa, H. M. (2018). Influence of spray drying conditions on the properties of avocado powder drink. Food Chem. 266, 284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.06.016

Do, H. T. T., and Nguyen, H. V. H. (2018). Effects of spray-drying temperatures and ratios of gum arabic to microcrystalline cellulose on antioxidant and physical properties of mulberry juice powder. Beverages 4, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/beverages4040101

Domínguez-Chávez, A. N., Garcia-Amezquita, L. E., Pérez-Carrillo, E., Serna-Saldívar, S. R. O., and Welti-Chanes, J. (2023). Water adsorption isotherms and phase transitions of spray-dried chickpea beverage. LWT 187, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115323

Evangelista, S. R., Miguel, M. G. d. C. P., Silva, C. F., Pinheiro, A. C. M., and Schwan, R. F. (2015). Microbiological diversity associated with the spontaneous wet method of coffee fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 210, 102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.06.008

Fazaeli, M., Emam-Djomeh, Z., Kalbasi Ashtari, A., and Omid, M. (2012). Effect of spray drying conditions and feed composition on the physical properties of black mulberry juice powder. Food Bioprod. Process. 90, 667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2012.04.006

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (2024). Al finalizar el año cafetero 2023—2024 colombia se consolida como el 2° productor de café arábica en el mundo—federación nacional de cafeteros caldas. Available online at: https://caldas.federaciondecafeteros.org/listado-noticias/al-finalizar-el-ano-cafetero-2023-2024-colombia-se-consolida-como-el-2-productor-de-cafe-arabica-en-el-mundo/

Ferrari, C. C., Germer, S. P. M., and de Aguirre, J. M. (2012). Effects of spray-drying conditions on the physicochemical properties of blackberry powder. Dry. Technol. 30, 154–163. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2011.628429

García-Parra, M., Roa-Acosta, D., García-Londoño, V., Moreno-Medina, B., and Bravo-Gomez, J. (2021). Structural characterization and antioxidant capacity of quinoa cultivars using techniques of ft-mir and uhplc/esi-orbitrap ms spectroscopy. Plants 10. doi: 10.3390/plants10102159

George, S., Thomas, A., Kumar, M. V. P., Kamdod, A. S., Rajput, A., T, J. J., et al. (2023). Impact of processing parameters on the quality attributes of spray-dried powders: a review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 249, 241–257. doi: 10.1007/s00217-022-04170-0

Gutiérrez Pulido, H., and de la Vara Salazar, R. (2008). Análisis y diseño de experimentos. Available online at: www.FreeLibros.org

Hernández-Nava, R., López-Malo, A., Palou, E., Ramírez-Corona, N., and Jiménez-Munguía, M. T. (2020). Encapsulation of oregano essential oil (Origanum vulgare) by complex coacervation between gelatin and chia mucilage and its properties after spray drying. Food Hydrocoll. 109, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106077

Horuz, E., Altan, A., and Maskan, M. (2012). Spray drying and process optimization of unclarified pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice. Dry. Technol. 30, 787–798. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2012.663434

Inés Puerta-Quintero, G., and Ríos-Arias, S. (2011). Composición química del mucílago de café, según el tiempo de fermentación y refrigeración. In Cenicafé 62(2).

Janne Carvalho Ferreira, L., Souza Gomes, M.de, Maciel Oliveira, L., and Diniz Santos, L. 2023 Coffee fermentation process: a review Food Res. Int. 169:112793 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112793

Joshi, N., Rawat, K., and Bohidar, H. B. (2018). pH and ionic strength induced complex coacervation of pectin and gelatin a. Food Hydrocoll. 74, 132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.08.011

Junior, J. M. L., Ferreira, A. P. R., Afonso, M. R. A., and da Costa, J. M. C. (2024). Sorption isotherms of powdered cajá-manga pulp in different drying processes. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 55, 1–9. doi: 10.5935/1806-6690.20240029

Lee, J. K. M., Taip, F. S., and Abdulla, H. Z. (2018). Effectiveness of additives in spray drying performance: a review. Food Res. 2, 486–499. doi: 10.26656/fr.2017.2(6).134

León-Martínez, F. M., Méndez-Lagunas, L. L., and Rodríguez-Ramírez, J. (2010). Spray drying of nopal mucilage (Opuntia ficus-indica): effects on powder properties and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 81, 864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.03.061

Machado, D. B., and de Oliveira, R. A. (2023). Functional and technological properties of coffee mucilage (Coffea arabica) and its application in edible films. Quim Nova 46, 778–784. doi: 10.21577/0100-4042.20230052

Magoni, C., Bruni, I., Guzzetti, L., Dell’Agli, M., Sangiovanni, E., Piazza, S., et al. (2018). Valorizing coffee pulp by-products as anti-inflammatory ingredient of food supplements acting on IL-8 release. Food Res. Int. 112, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.026

Medina-Torres, L., Calderas, F., Minjares, R., Femenia, A., Sánchez-Olivares, G., Gónzalez-Laredo, F. R., et al. (2016). Structure preservation of Aloe vera (barbadensis miller) mucilage in a spray drying process. LWT 66, 93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.10.023

Medina-Torres, L., Núñez-Ramírez, D. M., Calderas, F., González-Laredo, R. F., Minjares-Fuentes, R., Valadez-García, M. A., et al. (2019). Microencapsulation of gallic acid by spray drying with aloe vera mucilage (aloe barbadensis miller) as wall material. Ind. Crop. Prod. 138:111461. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.06.024

Miguel, C. (2013). Secado por aspersion de jugos de frutas: efecto de las variables de proceso sobre el producto final miguel angel casanova libreros

Ministerio de Hacienda, M., Público, C., Santamaría, M. C., Valencia, A. I., Fernando, J., Ortega, M., et al. (2015). Beneficio del café en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público.

Mishra, P., Mishra, S., and Mahanta, C. L. (2014). Effect of maltodextrin concentration and inlet temperature during spray drying on physicochemical and antioxidant properties of amla (Emblica officinalis) juice powder. Food Bioprod. Process. 92, 252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2013.08.003

Muñoz-Pabon, K. S., Parra-Polanco, A. S., Roa-Acosta, D. F., Hoyos-Concha, J. L., and Bravo-Gomez, J. E. (2022). Physical and paste properties comparison of four snacks produced by high protein quinoa flour extrusion cooking. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.852224

Otálora, M. C., Wilches-Torres, A., and Gómez Castaño, J. A. (2024). Physicochemical and bioactive characterization of pink guava pulp microcapsules prepared by freeze-drying using coffee mucilage as a wall material. LWT 207, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116665

Pardo, L. M. F., Castillo, N. V., Durán, Y. M. V., Rosero, J. A. J., and Lozano Moreno, J. A. (2022). Comprehensive analysis of ethanol production from coffee mucilage under sustainability indicators. Chem. Eng. Proc. Intens. 182, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2022.109183

Peñuela-Martínez, A.E., Pabón, J.P., and Oliveros-Tascón, C.E., (2011). ENZIMAS: una alternativa para remover rápida y eficazmente el mucílago del café.

Pui, L. P., Karim, R., Yusof, Y. A., Wong, C. W., and Ghazali, H. M. (2020). Optimization of spray-drying parameters for the production of ‘Cempedak’ (Artocarpus integer) fruit powder. J. Food Meas. Charact. 14, 3238–3249. doi: 10.1007/s11694-020-00565-3

Pui, L. P., and Saleena, L. A. K. (2022). Effects of spray-drying parameters on physicochemical properties of powdered fruits. Foods and Raw Materials 10, 235–251. doi: 10.21603/2308-4057-2022-2-533

Pyrzynska, K. (2024). Useful extracts from coffee by-products: a brief review. Separations 11, 1–27. doi: 10.3390/separations11120334

Rincón-Barón, E. J., and Andrés Torres-Rodríguez, G. (2023). Microsporogénesis y micromorfología del polen de la planta Alcea rosea (Malvaceae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 69, 852–864. doi: 10.15517/rbt

Ríos-Hernández, J., Chávez-Salazar, A., Restrepo-Montoya, E. M., Castellanos-Galeano, F. J., and Ospina-López, D. Y. (2024). Obtaining coffee mucilage microcapsules by spray drying using chemically modified banana starch. Ing. Compet. 26, 1–20. doi: 10.25100/iyc.v26i2.13502

Roa, D. F., Buera, M. P., Tolaba, M. P., and Santagapita, P. R. (2017). Encapsulation and stabilization of β-carotene in Amaranth matrices obtained by dry and wet assisted ball milling. Food Bioprocess Technol. 10, 512–521. doi: 10.1007/s11947-016-1830-y

Robert, P., Torres, V., García, P., Vergara, C., and Sáenz, C. (2015). The encapsulation of purple cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) pulp by using polysaccharide-proteins as encapsulating agents. LWT 60, 1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.10.038

Sarabandi, K., Peighambardoust, S. H., Sadeghi Mahoonak, A. R., and Samaei, S. P. (2018). Effect of different carriers on microstructure and physical characteristics of spray dried apple juice concentrate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 3098–3109. doi: 10.1007/s13197-018-3235-6

Shrestha, A. K., Ua-Arak, T., Adhikari, B. P., Howes, T., and Bhandari, B. R. (2007). Glass transition behavior of spray dried orange juice powder measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermal mechanical compression test (TMCT). Int. J. Food Prop. 10, 661–673. doi: 10.1080/10942910601109218

Sierra-López, L. D., Hernandez-Tenorio, F., Marín-Palacio, L. D., and Giraldo-Estrada, C. (2023). Coffee mucilage clarification: a promising raw material for the food industry. Food and Humanity 1, 689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.foohum.2023.07.019

Statista (2024). Principales productores de café del mundo en 2024| Statista Available online at: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/600243/ranking-de-los-principales-productores-de-cafe-a-nivel-mundial/

Tai, E. S., Hsieh, P. C., and Sheu, S. C. (2014). Effect of polygalacturonase and feruloyl esterase from aspergillus tubingensis on demucilage and quality of coffee beans. Process Biochem. 49, 1274–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.05.001

Tonon, R. V., Brabet, C., and Hubinger, M. D. (2008). Influence of process conditions on the physicochemical properties of açai (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) powder produced by spray drying. J. Food Eng. 88, 411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.02.029

Tontul, I., and Topuz, A. (2017). Spray-drying of fruit and vegetable juices: effect of drying conditions on the product yield and physical properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 63, 91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.03.009

Vargas, V., Saldarriaga, S., Sánchez, F. S., Cuellar, L. N., and Paladines, G. M. (2024). Effects of the spray-drying process using maltodextrin on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of the pulp of the tropical fruit açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Heliyon 10:e33544. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33544

Villegas-Santiago, J., Gómez-Navarro, F., Domínguez-Niño, A., García-Alvarado, M. A., Salgado-Cervantes, M. A., and Luna-Solano, G. (2020). Effect of spray-drying conditions on moisture content and particle size of coffee extract in a prototype dryer. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quim. 19, 767–781. doi: 10.24275/rmiq/Proc767

Vivek, K., Mishra, S., and Pradhan, R. C. (2021). Optimization of spray drying conditions for developing nondairy based probiotic sohiong fruit powder. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 21, 193–204. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2020.1864567

Yadav, K. C., Subba, R., Shiwakoti, L. D., Dhungana, P. K., Bajagain, R., Chaudhary, D. K., et al. (2021). Utilizing coffee pulp and mucilage for producing alcohol-based beverage. Fermentation 7, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/fermentation7020053

Zhang, J., Zhang, C., Chen, X., and Quek, S. Y. (2020). Effect of spray drying on phenolic compounds of cranberry juice and their stability during storage. J. Food Eng. 269, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.109744

Zotarelli, M. F., da Silva, V. M., Durigon, A., Hubinger, M. D., and Laurindo, J. B. (2017). Production of mango powder by spray drying and cast-tape drying. Powder Technol. 305, 447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2016.10.027

Keywords: coffee by-products, drying process, bioactive compounds, phenolic compounds, SEM, zeta potential, moisture sorption isotherms

Citation: Rivera�Escobar JD, Hoyos Concha JL, Roa-Acosta DF, Delgado JC, Rosero-Benavides VH and Torres GA (2025) Effect of spray drying conditions on the physicochemical, thermal, and microstructural properties of coffee mucilage powder (Coffea arabica–Castillo). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1654857. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1654857

Edited by:

Ashish Rawson, National Institute of Food Technology, Entrepreneurship and Management, Thanjavur (NIFTEM-T), IndiaReviewed by:

Miroslav Jůzl, Mendel University in Brno, CzechiaVictor Vicent, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Copyright © 2025 Rivera Escobar, Hoyos Concha, Roa-Acosta, Delgado, Rosero-Benavides and Torres. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan David Rivera Escobar, amRyaXZlcmFAdW5pY2F1Y2EuZWR1LmNv

Juan David Rivera Escobar

Juan David Rivera Escobar Jose Luis Hoyos Concha

Jose Luis Hoyos Concha Diego Fernando Roa-Acosta

Diego Fernando Roa-Acosta Jhan Carlos Delgado

Jhan Carlos Delgado Victor Hugo Rosero-Benavides

Victor Hugo Rosero-Benavides Gerardo Andres Torres

Gerardo Andres Torres