- 1School of Economics and Management, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China

- 2Business School, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3School of Economics, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, China

- 4School of Systems Science and Engineering, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

Introduction: Farmers’ own risk attitudes are important for e-commerce operations and digital transformation of rural economy.

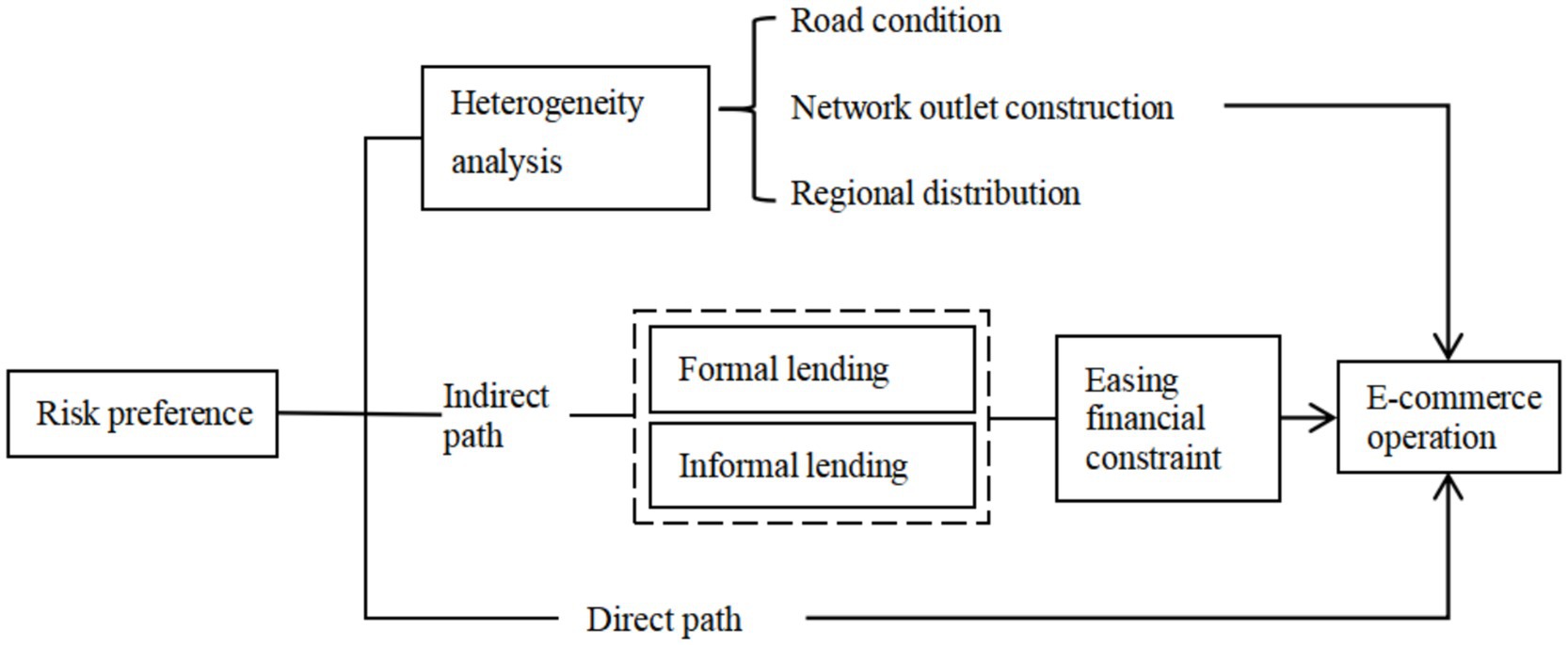

Methods: Based on the 3,670 farmers data of China Rural Revitalization Survey, using binary logit model and mediation effect model, this paper discusses the impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations and its mechanism, and examines the heterogeneous impact of road condition, network outlet construction and regional distribution. Building on this analysis, it further discusses differences in the impact across operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations and product types.

Results and discussion: The results indicate that risk preference significantly increases the likelihood of farmers’ participation in e-commerce operations, and this finding remains robust after both robustness and endogeneity tests. Mechanism analysis reveals that risk preference promotes e-commerce operations through both formal and informal lending channels. Heterogeneity analysis shows that the effect is stronger for farmers with favorable road condition, well-developed network outlet, and in the central and western regions. Further analysis demonstrates that the promoting effect of risk preference is particularly pronounced for large-scale e-commerce, social e-commerce, and live-streaming e-commerce, and is especially strong in transactions involving primary processed products. The findings suggest the need to establish a hierarchical support mechanism that accommodates differences in farmers’ risk preference, while simultaneously advancing innovations in rural financial services and strengthening the development of e-commerce infrastructure. In addition, differentiated guidance should be provided to foster innovative e-commerce models and to optimize the overall e-commerce ecosystem, thereby unlocking the full development potential of rural e-commerce and contributing to sustainable rural revitalization.

1 Introduction

The key to rural revitalization lies in industrial revitalization, which drives rural economic growth, increases employment opportunities and raises farmers’ incomes, thereby promoting the overall development of the countryside (Zhou et al., 2022). Farmers’ entrepreneurship is an important way to realize rural industrial revitalization (Li F. et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). In today’s digital wave sweeping the world, information and communication technology is gradually becoming popular in rural areas, and Internet infrastructure is increasingly improving. E-commerce, as an emerging form of entrepreneurship and business model, is profoundly reconfiguring the traditional agricultural economic pattern (Li et al., 2021). E-commerce breaks through time and space limitations and information barriers (Xu et al., 2022). It not only injects new kinetic energy into the transformation and upgrading of the rural economy, but also broadens the market boundary for farmers by building a multi-dimensional market channel, becoming a key engine driving the implementation of the rural revitalization strategy (Cen et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2023). More and more farmers are relying on digital platforms to deeply participate in the e-commerce ecosystem, enhance their market bargaining power and risk resistance through the innovation of agricultural product distribution channels, and reshape their own articulation mechanism with the modern market system to enhance their market competitiveness. Under the strategic synergistic framework of rural revitalization and digital village construction, the Chinese government has elevated the development of rural e-commerce to the height of national strategy, such as the Implementation Opinions on Promoting the High-Quality Development of Rural E-Commerce, which marks the fact that rural e-commerce support policies have shifted from superficial hardware construction to deep-level reforms of industrial and value chain reconstruction. However, e-commerce operations still face problems such as small total volume and low efficiency. As the direct decider and implementer of e-commerce operation, it is necessary to further explore the decision-making mechanism of their e-commerce operation from their own endowment, so as to stimulate the endogenous dynamics of farmers’ e-commerce operations and promote the digital transformation of rural economy.

Risk preference refers to an individual’s tolerance and inclination toward risk in decision-making situations, typically manifested as a proactive pursuit of risk and a preference for volatile returns over stable ones (Mata et al., 2018). As a key factor influencing farmers’ decisions, risk preference broadly affects multiple aspects of agricultural production and management, including production planning, technology adoption, financing choices, and entrepreneurial decisions, forming a systematic driving force from production to innovation. Specifically, in terms of production decisions, risk preference is closely linked to farmers’ crop choices and influences the allocation of agricultural planting structures, with risk-preferring farmers more inclined to move beyond traditional grain cultivation and expand the scale of cash crops (Chen et al., 2023b). In technology adoption, risk preference significantly shapes farmers’ willingness to adopt new crop varieties, innovative production practices, and low-carbon agricultural technologies (Hui and Yong, 2023; Sun et al., 2024). In financing and risk management, farmers with higher risk tolerance are more likely to utilize formal financing services or those provided by e-commerce platforms, whereas risk-averse farmers tend to rely on agricultural insurance to manage potential risks (Lyu and Barré, 2017). Regarding entrepreneurial decisions, risk preference influences farmers’ entrepreneurial behavior and increases the likelihood of engaging in entrepreneurial activities (Knapp et al., 2021; Peng H. et al., 2023; Tran and Pham, 2024). Risk preference is considered a critical psychological trait driving entrepreneurial behavior: on one hand, it reduces individuals’ sensitivity to uncertainty, strengthens opportunity recognition, and facilitates the translation of entrepreneurial intentions into actual actions (Yang et al., 2023); on the other hand, risk-preferring individuals tend to view potential risks as opportunities, prompting more proactive resource allocation to seize innovative prospects (Giaccone and Magnusson, 2022). Moreover, a higher tolerance for risk supports the expansion of social networks, providing access to essential resources and information, and further enhancing the likelihood of entrepreneurial success (Daskalopoulou et al., 2023).

Although existing studies have systematically examined the influence of risk preference on traditional entrepreneurial behavior of farmers, providing a solid theoretical foundation, the advent of the digital economy has brought profound transformations to entrepreneurial forms. In this context, farmers’ e-commerce operations, as a typical manifestation of the digital economy in rural areas, remain an underexplored theoretical domain, particularly regarding the role of risk preference. Most of the existing literature focuses on traditional entrepreneurship, with limited attention to e-commerce operations and, more specifically, to the heterogeneity across different types of e-commerce activities. To address this research gap, this study employs data from the China Rural Revitalization Comprehensive Survey to empirically examine the driving effect of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations and its underlying mechanisms. On this basis, we further analyze the differences in effects across operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations, and product types, aiming to precisely identify the boundary conditions under which risk preference influences e-commerce engagement, thereby providing a robust theoretical and empirical basis for the formulation of differentiated and targeted rural e-commerce support policies.

2 Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

2.1 The direct impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations

Risk preference promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations by reducing the perception of uncertainty, increasing tolerance, and reducing the cost of trust, enhancing the ability to identify market opportunities and utilize social capital.

First, risk preference enhances the probability of e-commerce operations for farmers by reducing the perception of uncertainty and increasing entrepreneurial willingness. Uncertainty perception refers to an individual’s subjective feelings and perceptions of uncertainty in the surrounding environment (Zayadin et al., 2023). In actual agricultural production and management, farmers encounter various uncertainties, including the adoption of new technologies, the threat of natural disasters, and fluctuations in market prices (Chavas and Nauges, 2020; Gupta et al., 2023; Khatri et al., 2024). For risk-preferring farmers, decision-making places greater value on long-term stable returns and treats these uncertainties as potential opportunities for growth. This positive cognitive approach reduces their perception of uncertainty about future outcomes (Findlater et al., 2019; Khanal et al., 2022), and significantly enhances their entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, risk-preferring farmers have a higher probability of engaging in e-commerce operations.

Secondly, risk preference improves the ability to identify opportunities, capture potential market opportunities, and enhance farmers’ e-commerce operations probability by tolerating uncertainty. The essence of entrepreneurship is the process of recognizing opportunities in uncertainty (Foss and Klein, 2020). Market demand fluctuations, technological innovation iterations and policy environment adjustments can lead to difficulties in accurately capturing business opportunities for entrepreneurial entities. Farmers’ limited ability to acquire and analyze information exacerbates the information asymmetry between them and the market, and their inability to adjust product or service supply in time to match market demand can lead to a significant increase in revenue uncertainty (Peng Y. et al., 2023). In addition, entrepreneurship is often accompanied by a shift in the application of technology, and the adoption of new technologies is often accompanied by risk costs (Wu, 2022), and there is a high degree of uncertainty about its actual effects and market acceptance, but risk preference people have a higher tolerance for market fluctuations, technological innovations, and other uncertainties, and are more willing to invest resources in exploring potential entrepreneurial opportunities, so the probability of a risk preference farmer engaging in e-commerce operations is higher.

Finally, risk preference enhances the probability of e-commerce operations for farmers by reducing trust costs and expanding entrepreneurial network resources. On the one hand, risk preference people have lower sensitivity to the potential costs such as time and economic investment required to maintain interpersonal trust and the risks they may face (Daskalopoulou et al., 2023), and this psychological trait makes them more inclined to show a higher level of trust in interpersonal interactions with acquaintances and even strangers (Pegram et al., 2022). Interpersonal trust, as an important component of social capital, provides critical support for entrepreneurial decision-making by enhancing the efficiency and reliability of information transfer in social networks (Pathan, 2022). Specifically, the social network of rural households is a key channel for information acquisition and resource integration (Li Q. et al., 2023), and risk preference promotes the identification of entrepreneurial opportunities by enhancing the level of trust, the truthfulness of information acquisition and willingness to cooperate. This advantage is particularly significant in tacit information flow, where high trust networks are more likely to transmit non-public knowledge such as market trends and technological experience, helping risk preference households capture potential entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). On the other hand, an increased level of trust also breaks through geographical constraints (Choi et al., 2024), and helps risk preference individuals to access a wider range of external networks and key resources such as finance and technology. Therefore, risk-preferring farmers are more likely to integrate supply chain resources and establish customer cooperative relationships through the trust network, to obtain the potential benefits of e-commerce, and to actively participate in e-commerce entrepreneurial practices.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H1: Risk preference significantly promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations.

2.2 The impact mechanism of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations

2.2.1 Formal lending mechanism

Risk preference enhances farmers’ access to formal lending by increasing their acceptance of risk-control clauses and willingness to seek financing, thereby effectively alleviating funding constraints and supporting the sustained development of their e-commerce operations. Specifically, risk-preferring farmers tend to prioritize long-term operational returns over short-term risks when making financing decisions, making them more willing to accept collateral, guarantees, and higher interest rates imposed by banks or other formal financial institutions (Hui and Yong, 2023). Such choices reflect rational behavior under a risk–return trade-off: they believe that potential high returns can offset financing uncertainties, and are therefore willing to provide asset collateral and sign strict contracts to overcome the risk-screening thresholds of formal lending and obtain larger loan amounts (Knight, 1921; Kihlstrom and Laffont, 1979). Moreover, when applying for large loans to fund infrastructure construction, brand promotion, warehousing and logistics, or the purchase of digital equipment for e-commerce operations, risk-preferring farmers exhibit stronger financing initiative. They are more willing to disclose detailed business plans and financial information to reduce information asymmetry with financial institutions, thereby improving credit evaluation efficiency and approval rates (Yu and Xiang, 2021). In this process, risk preference not only strengthens farmers’ ability to secure funds but also fosters longer-term cooperative relationships with financial institutions, forming a virtuous cycle for subsequent financing.

The “large-scale and stable” nature of formal lending aligns closely with the rigid investment demands of e-commerce operations (Zhao et al., 2024). E-commerce requires continuous investments in platform participation, brand development, supply chain integration, cold-chain logistics, and information system upgrades, with concentrated upfront capital needs and a relatively long payback period. Farmers obtaining formal financial support can make larger investments in brand building and technological upgrading, enhancing their bargaining power in platform competition and market expansion. At the same time, structured loan contracts provide greater flexibility in capital allocation, helping smooth cash flows during off-season periods and preventing operational disruptions caused by short-term liquidity shortages. More importantly, the risk management, credit record accumulation, and follow-up financial services provided by formal financial institutions improve farmers’ operational standardization and risk management capabilities, offering sustained credit backing for future business expansion and additional financing (Yu and Xiang, 2021).

Overall, risk preference not only directly drives farmers to overcome the entry barriers of formal lending, but also improves financing conditions and capital allocation efficiency, providing critical financial support for the initiation and expansion of their e-commerce operations and strengthening their long-term market viability. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H2: Risk preference facilitates farmers’ e-commerce operations by driving formal lending.

2.2.2 Informal lending mechanism

Risk preference drives farmers to use social networks for informal borrowing by reducing the cost of personal connections and the sensitivity to risks of informal contracts, thereby alleviating financial constraints. On the one hand, risk-preferring farmers are less sensitive to the cost of favors in rural acquaintance societies and are more likely to view social networks as a low-cost financing channel (Zhang et al., 2020). While traditional rural lending is often accompanied by the stress of complex human interactions, risk preference individuals are more concerned with the immediate benefits of capital availability for entrepreneurial opportunities. For example, when facing a short-term financial gap, risk-preferring farmers will take the initiative to ask their friends and relatives for loans, and prioritize the need for entrepreneurial capital by weakening the psychological expectation of “pressure of repayment of favors.” On the other hand, risk-preferring farmers are more tolerant of the risks of informal contracts and are more willing to accept the flexibility of informal lending. In the case of insufficient formal financial credit, farmers usually lack the guarantee of standardized contracts and face higher risks of financial security when they raise funds through channels such as family and friends lending and mutual aid associations (Anh et al., 2022). However, based on their confidence in their own risk-taking ability, risk preference people will actively reduce the requirements for contract completeness and place more emphasis on the timeliness of the availability of funds. For example, in order to seize market opportunities, some farmers choose to accept verbal agreements or simple written covenants even though they are aware of the risk of information asymmetry that may exist in informal lending, in order to quickly obtain funds to invest in production.

The “convenience and flexibility” characteristics of informal lending make it an important tool for farmers to meet their short-term capital needs. First of all, when farmers are faced with unexpected financial needs such as e-commerce promotions and logistics emergency purchases, they can quickly raise funds through the network of friends and relatives to avoid missing market opportunities due to cumbersome processes. Especially in the peak season of the live broadcast with goods, farmers need to raise funds in a short period of time to expand inventory, informal lending “borrow and get” characteristics can quickly ease the liquidity constraints, to ensure the smooth implementation of promotional activities. Second, informal lending relies on the implicit guarantee mechanism of neighborhood reputation (Li Q. et al., 2023), which significantly reduces transaction costs through credit constraints. Risk-preferring farmers are more willing to take on potential social credit risks in exchange for the immediate availability of funds. Although the amount of this type of financing is usually small, the approval process is simple and the time for funds to be available is short, which can effectively respond to the high-frequency and small-amount capital needs in entrepreneurial operations and enhance operational flexibility. Although informal lending is difficult to scale up due to geographic constraints, its advantages in short-term financing and flexible risk sharing make it an important complementary mechanism to the formal financial system (Phan et al., 2024).

It is thus evident that informal lending plays an irreplaceable buffering role in meeting the flexible funding needs of e-commerce operations, providing critical support for risk-preferring farmers to seize short-term market opportunities. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis:

H3: Risk preference facilitates farmers’ e-commerce operations by driving informal lending.

2.3 Heterogeneous impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations

The sustained development of rural e-commerce depends not only on farmers’ individual business decisions but also on the broader external environment. While risk preference strongly influences farmers’ willingness to undertake the uncertainties of e-commerce entrepreneurship, its effect is not exerted in isolation; rather, it is embedded within specific infrastructure conditions and regional development contexts. Well-developed road networks and logistics service network outlets can reduce transportation costs and enhance expected returns, thereby amplifying the positive impact of risk preference. Conversely, when infrastructure is weak and market accessibility is limited, even farmers with a high risk preference may lower their entrepreneurial intentions due to constrained profit expectations. Likewise, regional differences in policy support, industrial foundations, and market potential can reshape the mechanism through which risk preference translates into actual business behavior. Guided by this logic, this study further examines heterogeneity along three dimensions: road condition, network outlet construction, and regional distribution.

As a key infrastructure element of rural e-commerce logistics system, road conditions are directly related to the circulation efficiency and market accessibility of agricultural products (Lin et al., 2022). The optimization of road infrastructure has a dual effect, on the one hand, by improving the layout of transportation channels and nodes, it can significantly improve the operational efficiency of the logistics system, realize the effective control of operating costs, so as to continue to strengthen the competitiveness of the market; on the other hand, it provides infrastructural support for the integrated development of logistics and e-commerce industry, and fosters the formation of a new type of productive forces with the characteristics of technological innovation through the construction of a modern circulation system. Shape. However, some remote areas are limited by low-grade road infrastructure and poor road conditions, resulting in low efficiency of logistics transportation vehicles (Guo and Chen, 2022). The bottleneck constraint of road facilities reduces the expected returns of entrepreneurial activities, which in turn inhibits the entrepreneurial willingness of risk-preferring farmers.

As a key node of the rural e-commerce logistics system, the construction of network outlet plays a fundamental role in solving the “last kilometer” distribution problem (Mucowska, 2021). The construction of network outlet improves the warehousing and logistics capacity (Yang and Wu, 2021), facilitates resource sharing and synergistic development, and can enhance the overall competitiveness of rural e-commerce (Wei et al., 2020). However, some rural areas face structural problems such as insufficient county-level distribution centers, lagging construction of cold chain logistics systems, insufficient sorting and processing facilities, and inefficient operation of logistics network, which leads to inefficient transportation and weakened market competitiveness (Guo and Chen, 2022). In addition, the spatial characteristics of rural areas, which are “sparsely populated,” further aggravate the difficulty of logistics network layout, and there are problems such as decentralization of network outlet, high distribution costs, and poor timeliness in terminal distribution. Therefore, the shortcomings of network outlet construction will significantly inhibit the enthusiasm of e-commerce entrepreneurship of risk-preferring farmers.

Rural e-commerce shows an unbalanced situation among regions (Lin et al., 2022). Eastern rural e-commerce is mostly a spontaneous formation of “e-commerce villages,” mainly standardized light industrial products, relying on large-scale production and brand effect, and e-commerce operations is mainly youth entrepreneurship, the threshold is high, while the central and western regions have good policy support, through improving logistics and other infrastructure, incentives to return to their hometowns to start their own businesses and social governance to promote the countryside industry development, and develops regional characteristic industries based on natural endowments (Wei et al., 2020), which has scarcity and competitiveness under the trend of consumption upgrading and diversification, and provides more market opportunities for risk-preferring farmers, which is conducive to their e-commerce operations activities.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H4: The impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations is heterogeneous in terms of road condition, network outlet construction, and regional distribution.

The theoretical analysis framework is shown in Figure 1.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data sources

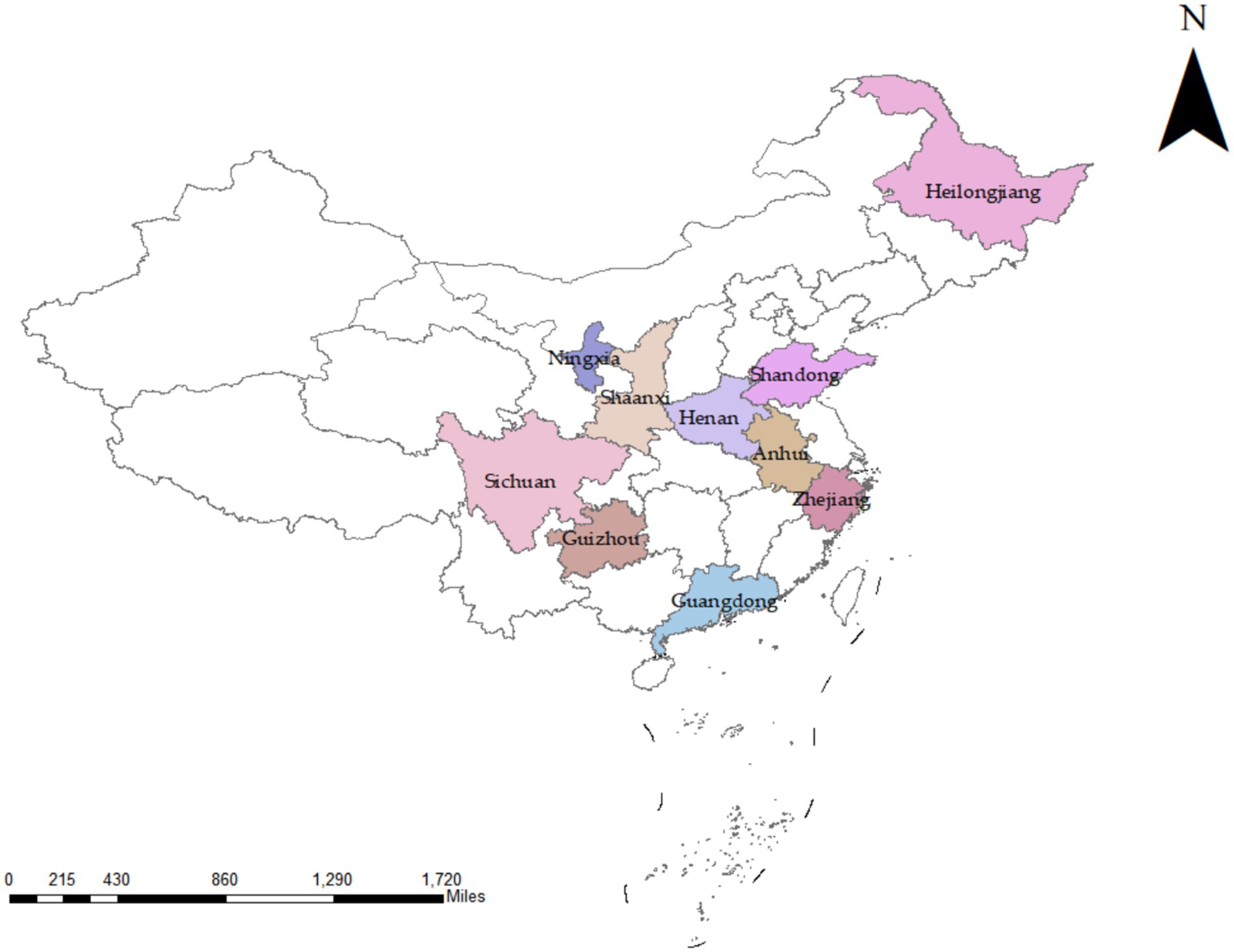

The data in this paper comes from the China Rural Revitalization Survey (CRRS), a comprehensive survey conducted by the Institute of Rural Development of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2020. The database contains information at the level of individuals, farm households, and administrative villages. The CRRS survey used stratified sampling to survey farm households in a total of 50 counties, 156 townships, and 300 villages in 10 provinces, including Shandong, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Henan, Heilongjiang, Shaanxi, Guizhou, Ningxia, Anhui, and Sichuan, with a geographic coverage covering developed areas along the eastern seaboard, the main grain-producing areas in central China, and ecologically fragile areas in western China, with a significant spatial heterogeneity. The distribution of sampling areas is shown in Figure 2. A total of 3,833 farm household samples were collected, and 3,670 valid samples were obtained after removing the samples of farm households with missing or abnormal key indicators.

3.2 Variable selection

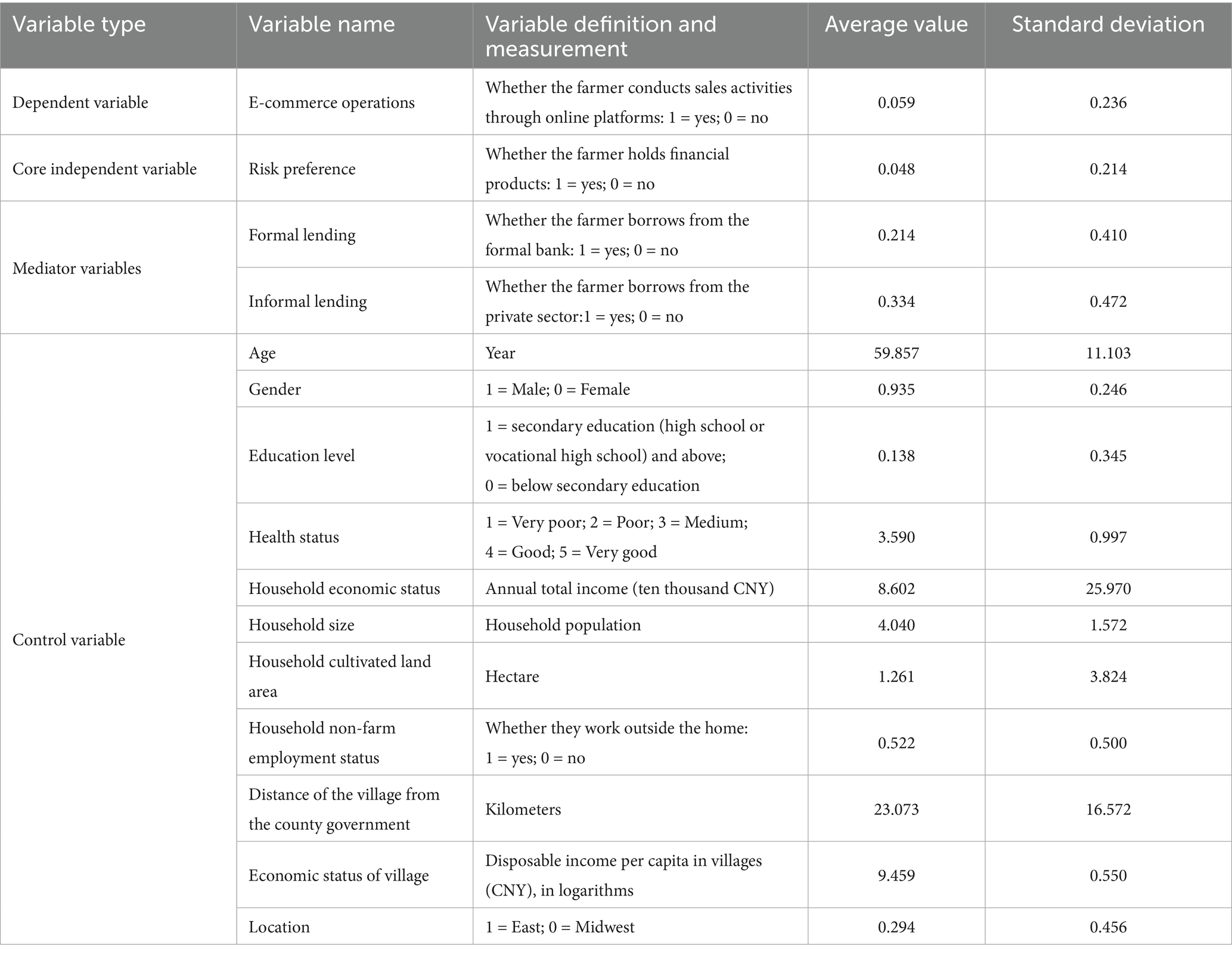

3.2.1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this paper is the e-commerce operations of farmers. Referring to the study of Qiu et al. (2025a), farmers’ sales activities through online platforms are regarded as having e-commerce operations and assigned the value of 1; conversely, the value is 0. This variable directly captures whether farmers have adopted e-commerce operations as a new business model, serving as the core decision and key behavioral outcome in this study.

3.2.2 Core independent variable

The core independent variable of this paper is risk preference. Referring to the existing research (Aren and Nayman Hamamci, 2020), the risk preference is measured by the holdings of farmers’ financial products. The use of financial product holdings to measure risk preference is based on the following theoretical considerations. First, according to the theory of revealed preference, an individual’s true preference are reflected in their actual behavior. Farmers’ real investment decisions in the financial market provide a more objective and authentic representation of their inherent risk tolerance. Farmers who hold high-risk financial products have, in effect, demonstrated through their behavior that they possess a higher risk preference. Second, e-commerce operations share similar decision-making characteristics with financial investments, such as facing uncertainty and pursuing potentially high returns. Therefore, using risk preference in the financial domain to predict farmers’ adoption of e-commerce offers strong validity. Based on this logic, farmers are defined as having a high risk preference if they hold any of the specified financial products, which is recorded as a value of 1, and as having a low risk preference if they do not, which is recorded as a value of 0.

3.2.3 Mediating variables

Based on the theoretical analysis, risk preference promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations by driving both formal and informal lending. Referring to the study of Phan et al. (2024), the questionnaire “whether farmers borrowed from formal banks” was selected to measure formal lending, and if they did, it was assigned a value of 1; on the contrary, the value is 0. Formal lending reflects a farmer’s proactive entry into the formal credit market and the use of external capital to expand business scale, demonstrating an “active financing capacity” based on risk tolerance. Meanwhile, the questionnaire “whether farmers borrowed from the private sector” was selected to measure informal lending, and if they did, it was assigned a value of 1; on the contrary, the value is 0. Informal lending relies more heavily on social networks and trust relationships, representing the farmer’s “mutual-assistance financing capacity.” Together, these two variables capture, from the perspectives of both formal and informal institutions, how risk preference shapes farmers’ resource-mobilization strategies, making them ideal mechanism variables to connect risk preference with e-commerce operations decisions.

3.2.4 Control variables

In addition to the core independent variable, to accurately identify the net effect of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations. Combining the existing data indicators and referring to the research of Rizwan et al. (2020), this paper selects the age, gender, education level and health status to describe the individual characteristics of farmers; household economic status, household size, household cultivated land area and household non-farm employment status are selected to reflect family characteristics; Select distance of the village from the county government, economic status of village and location to reflect the regional characteristics. The descriptive statistics of all variables are shown in Table 1.

3.3 Model construction

3.3.1 Benchmark regression model

As the e-commerce operations of farmers is a binary variable, this paper uses the binary logit model to empirically test the impact of risk preference on the e-commerce operations of farmers, and constructs the regression model as follows:

In Equation (1), represents farmers’ e-commerce operations; is the risk preference; is a series of control variables; is a constant term; , are the coefficient of the model to be estimated; is the error term.

3.3.2 Mechanism test model

On the basis of exploring the impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations, this paper further examines its mechanism of action. With reference to Baron and Kenny (1986), constructed the following mechanism effect model. The model Equations (2–4) are as follows.

In equation: , , are for the e-commerce operations, risk preference and mechanism variables, respectively, n is taken as 1 and 2, is formal lending and is informal lending; denote the control variables; , , are the constant term; , , , , , , are the coefficients of the model to be estimated; , , are the error term.

4 Results and analysis

Prior to the benchmark regression, the paper conducted a multicollinearity test on all independent variables. The VIF was up to 1.15, which were all less than 10, indicating that there was no serious multicollinearity problem among the variables.

4.1 Benchmark regression results

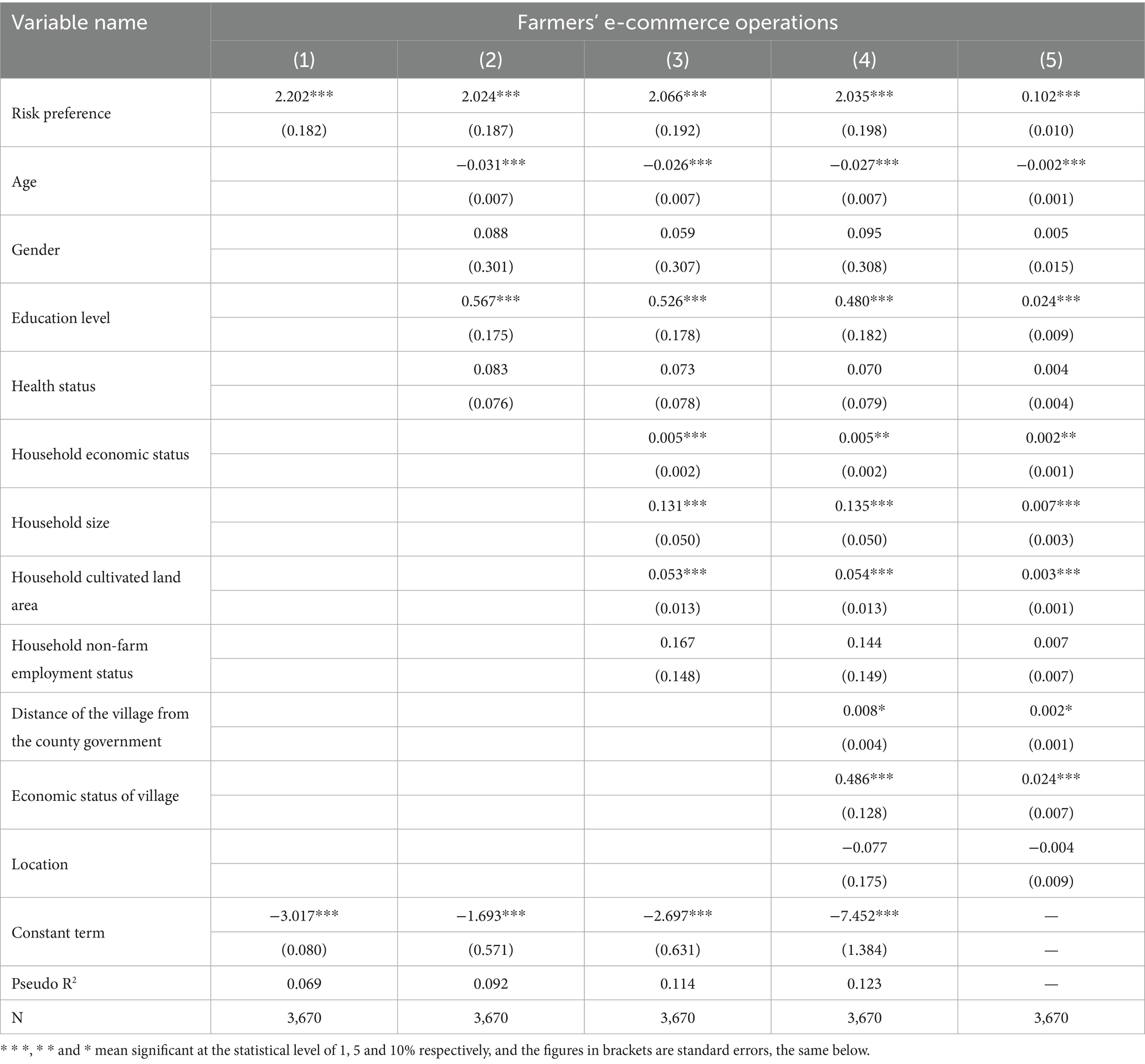

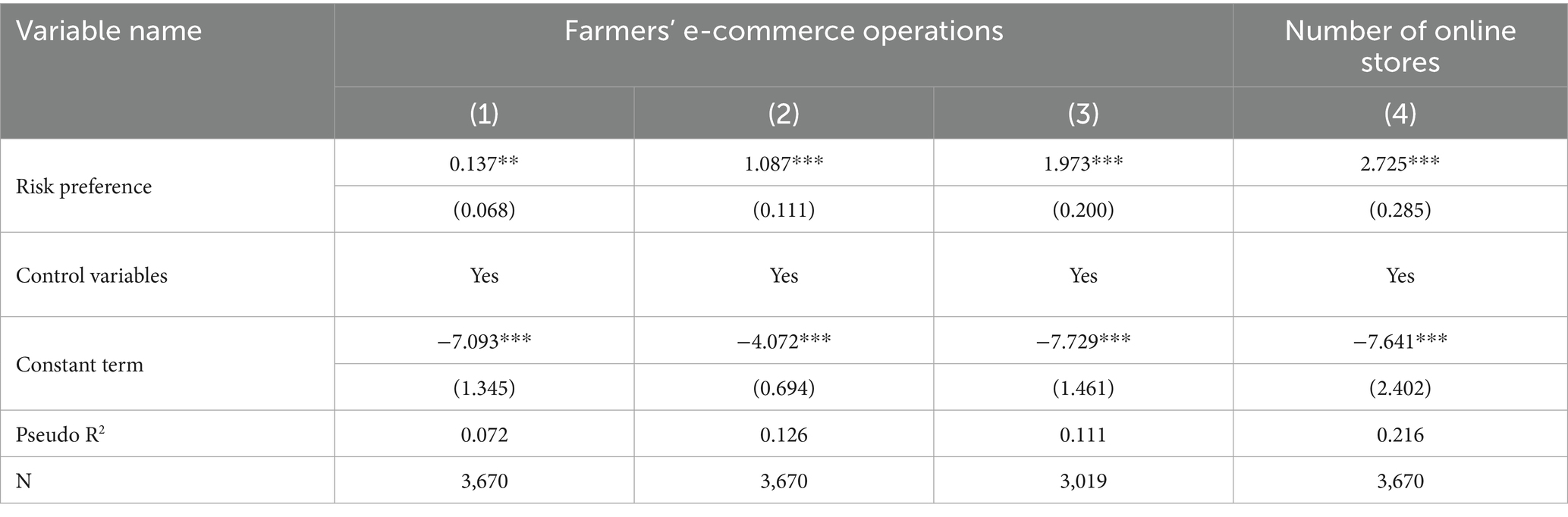

The results of the empirical analysis of the impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations are shown in Table 2, where columns (1), (2), (3), and (4) denote the regression results of gradually adding the variables of the core independent variables, individual characteristics, household characteristics, and village characteristics, respectively, and column (5) denotes the marginal effect of adding all control variables, which indicates that, with all other variables unchanged, for every one-unit increase in risk preference, the farmers’ e-commerce operations probability increases by 10.2%.

The results show that risk preference has a significant positive effect on farmers’ e-commerce operations and promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations, and research hypothesis 1 is tested. The underlying reason may lie in the fact that risk preference provides farmers with crucial psychological capital, allowing them to reinterpret the inherent market, technological, and financial uncertainties of e-commerce not as pure survival threats but as potential development opportunities. Unlike risk-averse farmers, who tend to overestimate the probability of failure and adopt avoidance strategies, risk-preferring farmers are better able to assess and embrace risk. Their willingness to take risks aligns closely with the “high-risk, high-reward” nature of e-commerce business models. This alignment is reflected not only in initial entrepreneurial decisions but also in the ongoing management of e-commerce operations, which requires continuous trial-and-error and rapid iteration, thereby serving as a key driver for farmers to engage in and persist with e-commerce activities.

Among the control variables, age has a significant negative effect on farmers’ e-commerce operations, and education level, household economic status, household size, household cultivated land area, distance of the village from the county government, and economic status of village have a significant positive effect on farmers’ e-commerce operations. The possible reasons for this are that senior farmers’ acceptance of e-commerce operations is lower due to their relatively weaker cognitive ability and ability to adapt to new technologies; farmers with a high level of education strengthen the efficiency of e-commerce skill learning and technology adoption by virtue of the advantage of their human capital; a better economic situation indicates the possession of abundant household capital, which buffers the business risk and guarantees the economic viability for e-commerce entrepreneurship; a large size of the household population The large family size means abundant labor resources and heterogeneous knowledge reserves, which can form a good synergy effect of division of labor in e-commerce operations; large-scale agricultural production provides stable supply chain support for farmers’ e-commerce; the distance from the county government will lead to the restriction of the traditional economic development of the region, insufficient access to resources and lagging news, etc., so the risk-preferring farmers are more inclined to break through the spatial and resource constraints by e-commerce, and strengthen the efficiency of e-commerce. The good economic condition of the village can reduce the cost of information search and logistics through the effect of industrial agglomeration, and improve the operational efficiency of farmers’ e-commerce.

4.2 Robustness test

4.2.1 Replacement of core independent variable

In order to investigate whether the previous regression results are robust, this paper uses the amount of financial products purchased to measure risk preference and conduct regression. In order to avoid the interference of outliers, a 1% bilateral tailing treatment was applied to the risk preference index. The regression results are shown in column (1) of Table 3. The results show that risk preference still has a significant positive impact on Farmers’ e-commerce operations, and promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations. The above regression results are robust.

4.2.2 Replacement of regression method

Considering that farmers’ e-commerce operations is a binary variable, this paper adopts Probit model instead of logit model for re-estimation, and the results, as shown in column (2) of Table 3, the risk preference is still significantly positive at 1% statistical level, indicating the robustness of the above regression results.

4.2.3 Deletion of samples

Considering the special characteristics of old farmers in physical ability and cognition, in order to avoid the interference of special samples, this paper deletes the sample of farmers over 70 years old for re-regression, and the regression results, as shown in column (3) of Table 3, show that the risk preference still has a significant positive impact on the e-commerce operations of farmers, which confirms that the previous results are robust.

4.2.4 Replacement of the dependent variable

Referring to existing research (Qiu et al., 2025b), this paper uses the number of online stores to measure the e-commerce operations of farmers and conducts a re-regression. The regression results are shown in column (4) of Table 3. The impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations is significantly positive at the 1% statistical level, further verifying the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

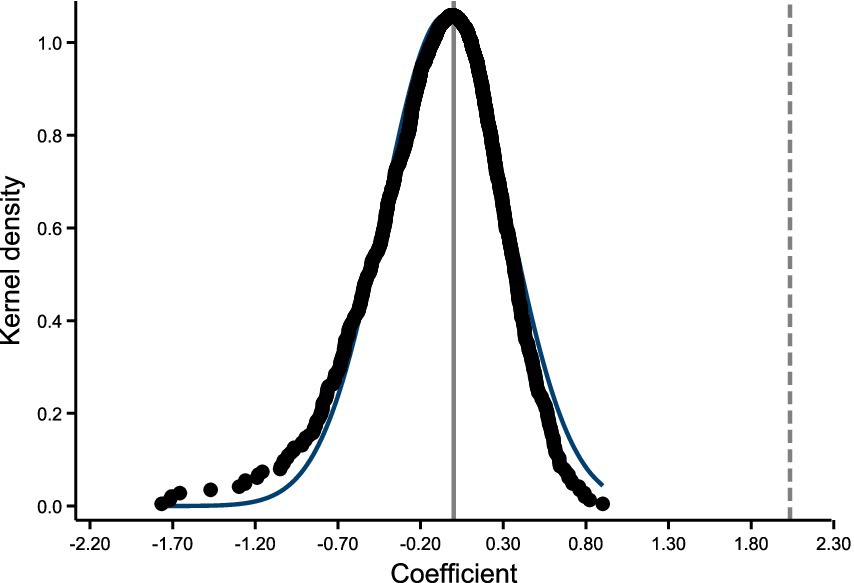

4.2.5 Placebo test

In order to determine whether the unobserved randomization factor affects the regression results, this paper sets up an experimental group for the placebo test with reference to the study of Niu et al. (2022), and the results are shown in Figure 3. After repeating this randomization process 1,000 times, the distribution of the regression coefficients of risk preference is concentrated around zero, which is approximately normally distributed, in line with the expectation of “no true effect.” At the same time, the coefficients of the benchmark regression are much higher than the distribution of the coefficients generated by random replacement, indicating that the significant positive impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations is not caused by random noise, and the placebo test passes, eliminating the potential impact of unobserved factors, indirectly proving that risk preference has a significant positive impact on farmers’ e-commerce operations, and verifying the reliability of the results of the previous paper.

4.3 Endogenous test

4.3.1 Reverse causation

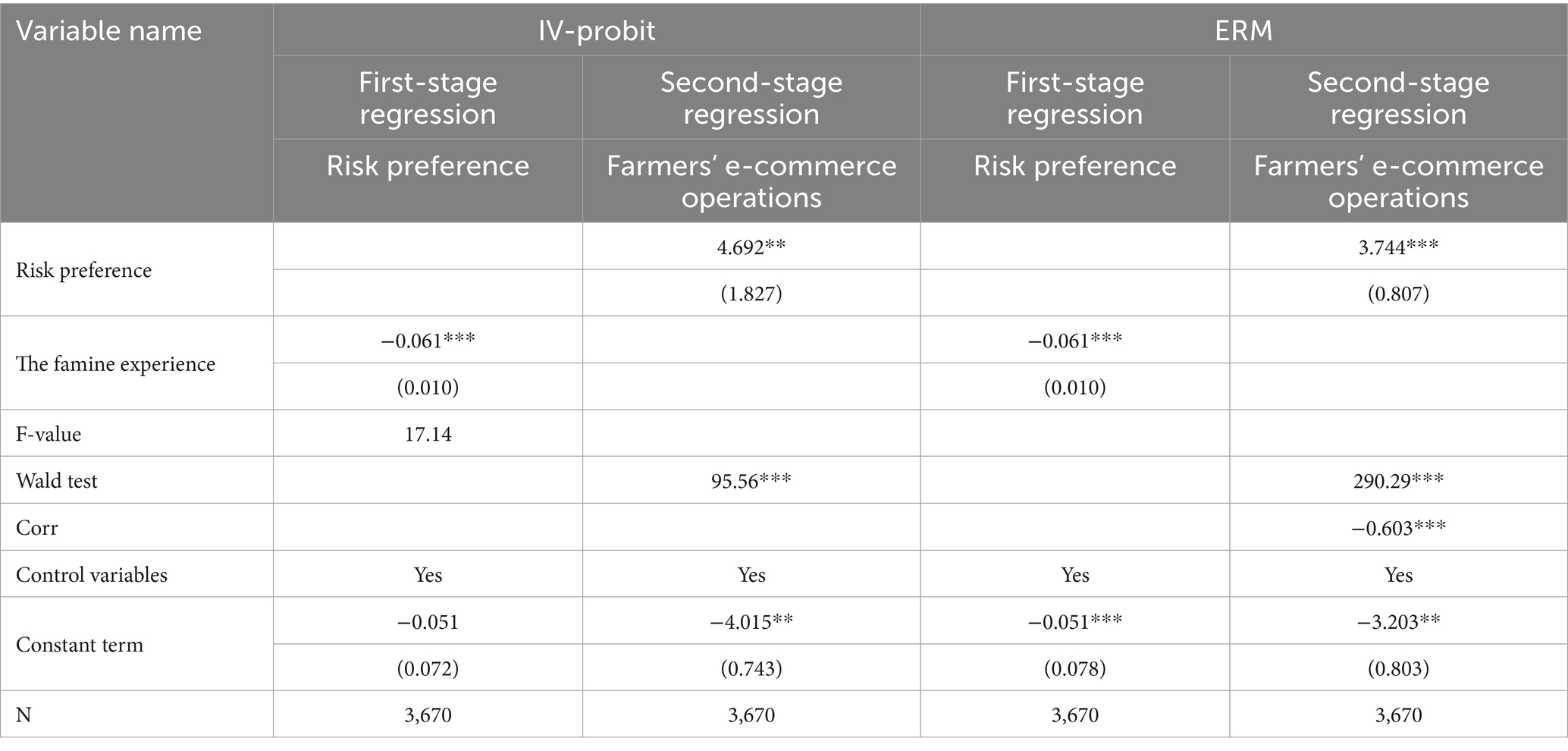

Possible endogeneity of reverse causality between risk preference and farmers’ e-commerce operations. On the one hand, farmers with a high risk preference are more inclined to choose e-commerce operations in pursuit of high returns from entrepreneurship; on the other hand, fluctuations in returns from e-commerce operations may in turn reverse the shaping of farmers’ risk preference. Therefore, in this paper, we refer to the study of and use the instrumental variables approach to address the potential endogeneity problem (Qiu et al., 2024b).

Imprinting Theory suggests that childhood experiences influence an individual’s character formation, cognitive attitudes, and behavioral patterns, among other things (Daines et al., 2021). In terms of physiological and psychological theories, the brain nerves are extremely sensitive to personal experiences, and the feelings generated by the events people experience create memory anchors and are internalized into a belief (Wing et al., 2018), which serves as information that influences preference and decision-making judgments. The Great Famine of 1959–1961 in China was a major exogenous event that caused a large number of population deaths (Cheng et al., 2021). Individuals’ early fear of famine trauma carries over into adulthood, creating a negative impact that stays with them throughout their lives (Arage et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2024). It has been found that early famine experiences profoundly affect farmers’ perceptions and risk preference (Chen et al., 2023a; Wang et al., 2024), leading to higher savings rates (Ding et al., 2022; Guo and Chen, 2025), and that farmers who have experienced a famine are more likely to seek stable returns that manifests itself in risk-averse tendencies. It’s clear that famine experiences meet both the exogeneity and correlation requirements by shaping risk preference. Therefore, this paper chooses famine experience as an instrumental variable and measures it according to the age of the survey respondents. If the respondent was born in 1961 and before, he/she is considered to have experienced the Great Famine and is assigned a value of 1. If he/she was born in 1962 and after, he/she is considered not to have experienced the Great Famine and is assigned a value of 0.

The results of the endogeneity test of the effect of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations are shown in Table 4. From the Wald and Corr values, the original hypothesis that the variables are exogenous is rejected, i.e., there is an endogeneity problem. The results of the first-stage regressions of the IV-Probit model and the ERM model show that the effect of famine experience on the risk preference of the farmers is significantly negative at the 1% statistical level and the F-value of the joint test of significance is greater than 10, which suggests that there is no problem of weak instrumental variables. Meanwhile, the second-stage regression results of both the IV-Probit model and the ERM model show that risk preference still has a significant positive impact on farmers’ e-commerce operations after the introduction of instrumental variables, which further validates the reliability of the findings of this paper.

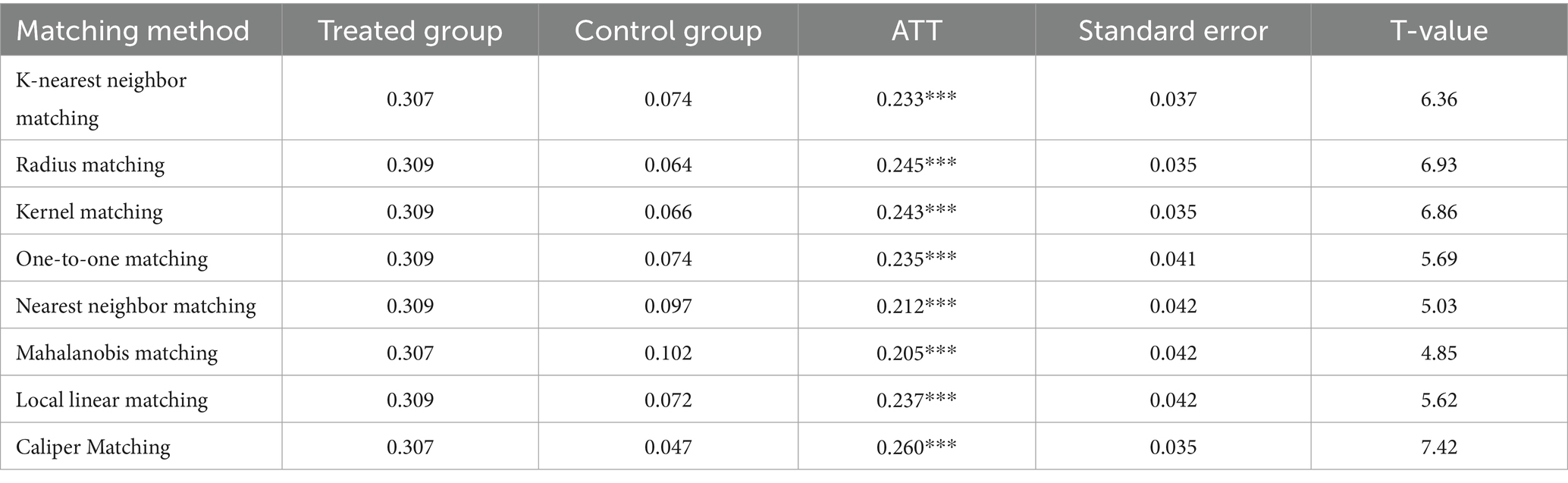

4.3.2 Self-selection bias

Risk preference, as a subjective psychological characteristic of farmers, may be influenced by certain unobserved factors, leading to a non-random selection of the sample and creating endogeneity problems. In order to effectively solve the endogeneity problem caused by self-selection bias, this paper adopts the propensity score matching (PSM) method to compensate for the limitations of traditional regression analysis methods. Referring to the study of Qiu et al. (2024a), eight different matching techniques, namely k-nearest-neighbor matching, radius matching, kernel matching, one-to-one matching, nearest-neighbor matching, mahalanobis matching, local linear matching, and caliper matching, were used in this study to re-run the regression analysis, and the results are shown in Table 5. The results of the analysis show that risk preference has a significant positive impact on farmers’ e-commerce operations, which further validates the robustness of the study’s findings.

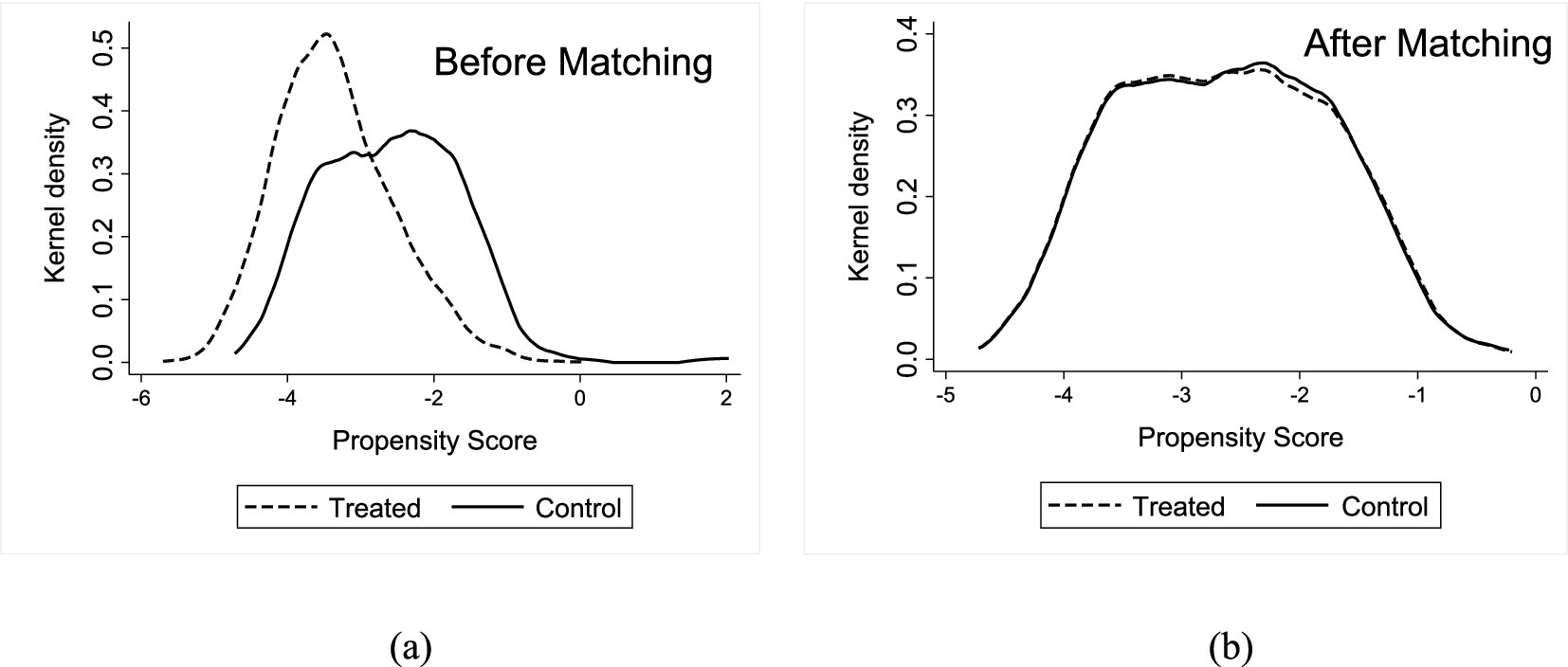

PSM model specification needs to meet the two preconditions of overlapping assumption and balance characteristics (Caliendo and Kopeinig, 2008). For the overlapping hypothesis that the public support domain needs to be tested, Figure 4 shows the distribution of propensity scores for testing the public support domain. After matching, the high-risk preference sample group and the low-risk preference sample group almost overlap in the propensity score, and there is a large common support interval, which indicates that the matching is more reasonable.

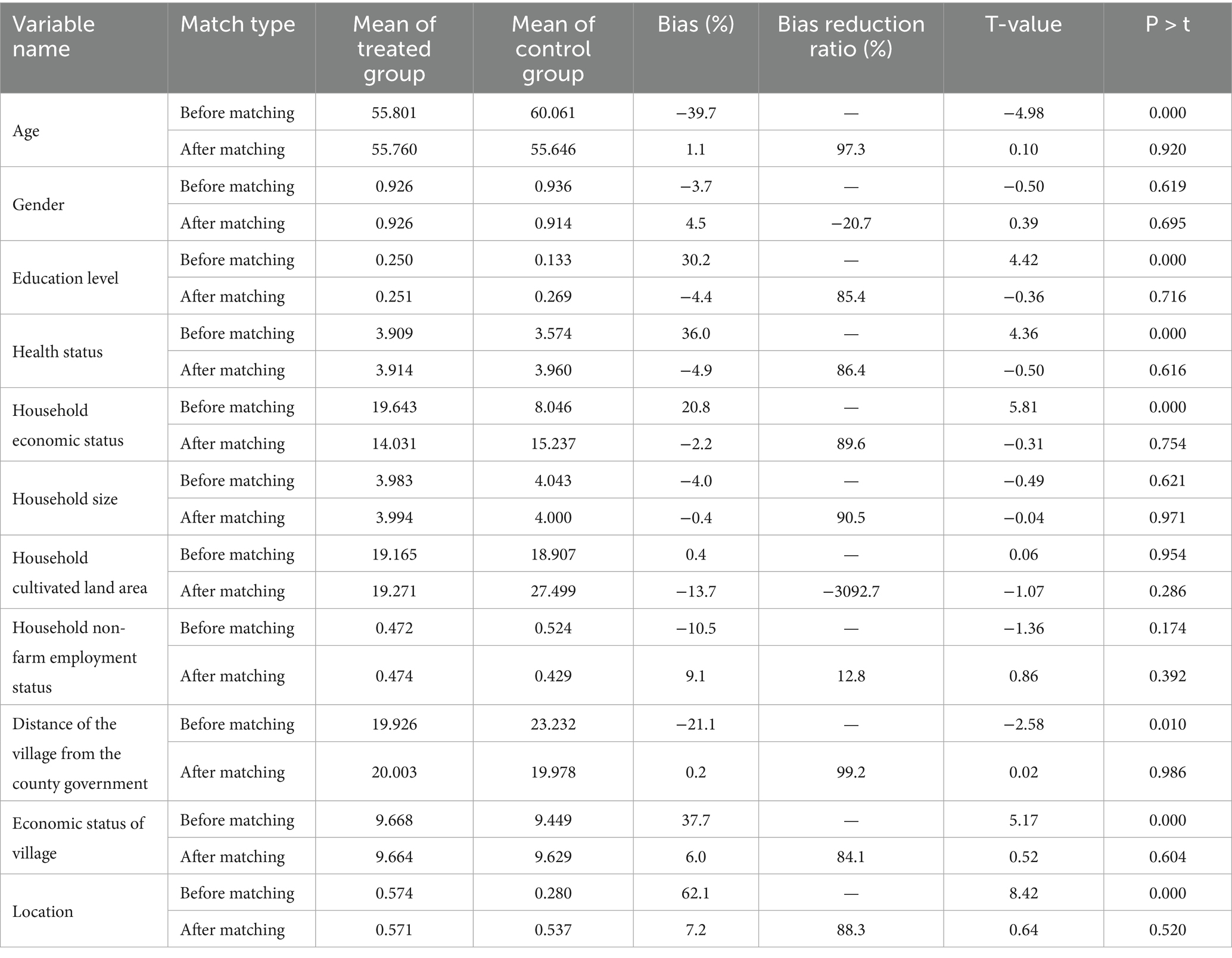

In order to check whether the above propensity score matching estimation results balance the data well, it is necessary to conduct a balance test. The balance test results are shown in Table 6. In this paper, the one-to-one matching method is taken as an example. Compared with before matching, the standardized deviation rate of control variables is reduced after matching, and the standard deviation rate of most control variables is less than 10%. At the same time, the t-test results of most control variables do not reject the original hypothesis that there is no systematic difference between the treated group and the control group, and effectively balance the differences in the distribution of covariates between the treated group and the control group. Therefore, the propensity score matching results passed the balance test.

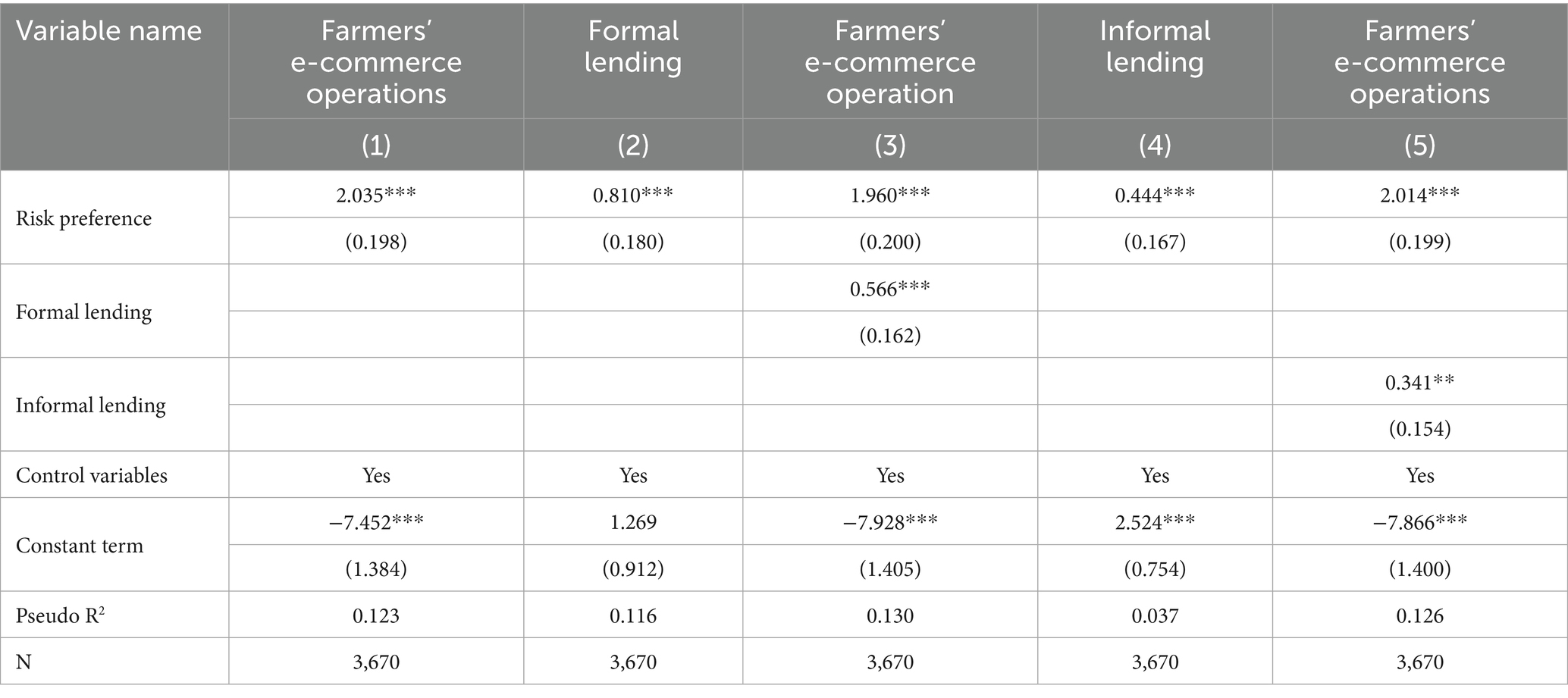

4.4 Mechanism analysis

Based on the previous theoretical analysis, in order to verify whether risk preference indirectly affects farmers’ e-commerce operations through two paths: formal lending and informal lending, this paper tests the mechanism role of formal lending and informal lending, respectively. Combined with the regression results in columns (1), (2) and (3) of Table 7, these findings show that risk preference boosts farmers’ e-commerce operations by driving formal lending, supporting research hypothesis 2. Formal lending becomes an important tool for farmers to alleviate financial constraints due to its normative and low-cost characteristics. Meanwhile, combining the regression results of columns (1), (4) and (5) in Table 7, the findings show that risk preference promotes farmers’ e-commerce operations by driving informal lending, supporting research hypothesis 3. This suggests that informal lending, as an alternative financing channel, can alleviate short-term liquidity pressure and promote farmers’ e-commerce operations through flexible lending and relationship trust.

Specifically, this study confirms that farmers with higher risk preference are more likely to seek loans to initiate or expand their e-commerce operations, with both formal and informal lending serving as significant mediating channels. In terms of formal lending, the widespread adoption of the Internet, coupled with improvements in farmers’ financial literacy and digital skills, provides a crucial foundation for their participation in e-commerce entrepreneurship. These factors not only enhance farmers’ understanding of and willingness to adopt e-commerce operations, but, more importantly, higher financial literacy enables them to more accurately assess the risks and returns associated with formal loans and to understand relevant terms, thereby strengthening their confidence and capability to access formal financial markets. Empirical evidence further indicates that policy support from the government and financial institutions—such as loan guarantees, interest subsidies, and dedicated credit products—can effectively reduce financing barriers and perceived risks, thereby reinforcing the transmission mechanism through which risk preference promotes e-commerce engagement via formal lending. Regarding informal lending, risk preference also plays a significant role. For farmers who have difficulty accessing formal credit or prefer more flexible arrangements based on familiar networks, higher risk preference encourages greater reliance on informal loans, such as borrowing from relatives and friends. Compared with formal financial institutions, informal lending generally involves fewer approval procedures and no collateral requirements, substantially reducing transaction costs and improving financing efficiency, making it an important complementary channel for some farmers’ e-commerce entrepreneurship financing.

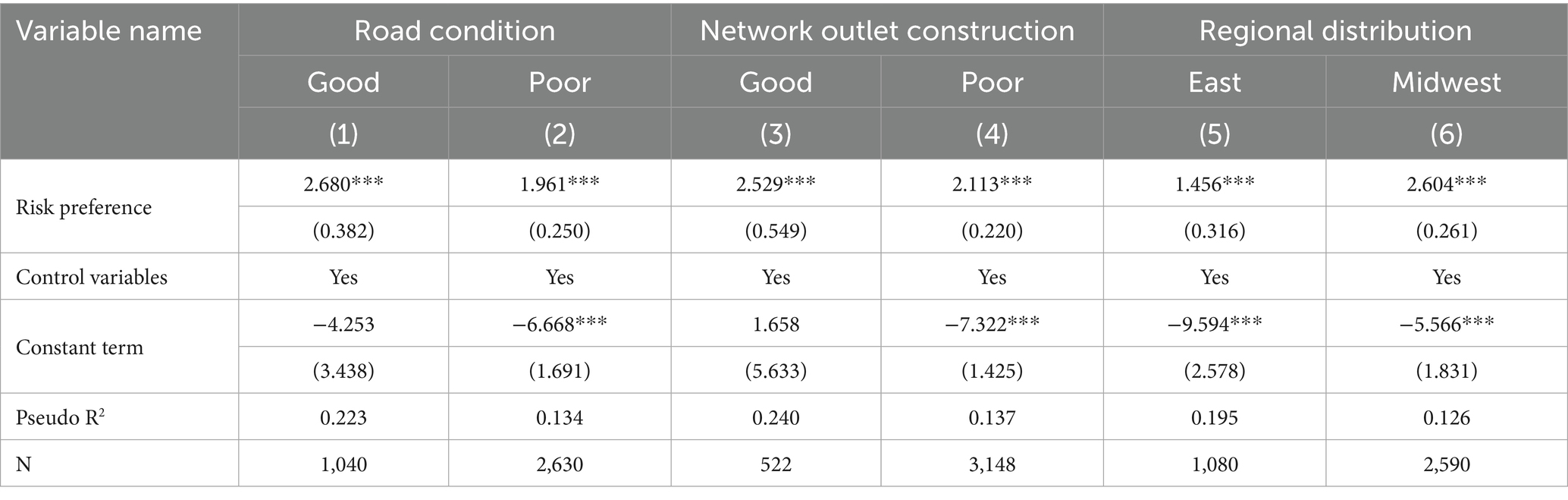

4.5 Heterogeneity test

1. Road condition. Road infrastructure conditions are important external conditions for e-commerce operations, which may affect the e-commerce operations effect of risk preference. Based on whether the roads between the villages and groups where the farmers are located are hardened or not, the sample is divided into two groups: good road condition and poor road condition. The regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8. The results show that the road conditions strengthen the role of risk preference in promoting farmers’ e-commerce operations. The underlying reason may lie in the fact that well-developed road infrastructure directly improves the accessibility, timeliness, and reliability of logistics, significantly reducing operational risks and expected losses caused by transportation delays or product damage. This not only expands the geographical coverage of e-commerce services and increases the potential customer base, but also enhances farmers’ trust and sense of control over e-commerce operations. For risk-preferring farmers, the reduction of external risks generates a “synergistic effect” with their inherent propensity for risk-taking, enabling them to more clearly anticipate the potential returns of e-commerce operations and more decisively transform entrepreneurial intentions into concrete actions.

2. Network outlet construction. E-commerce service outlets provide important support for the construction of rural e-commerce ecology, which may affect the e-commerce operations effect of risk preference. According to whether there is an e-commerce service station or a product consignment point in the village where the farmers are located, the sample is divided into two groups: good network outlet construction and poor network outlet construction. The regression results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 8. The results show that e-commerce service network outlets strengthen the role of risk preference in promoting farmers’ e-commerce operations. The underlying reason may lie in the dual pathways through which e-commerce service network outlets empower farmers. On the one hand, they provide information consultation, technical training, and operational guidance, effectively compensating for farmers’ shortcomings in digital skills and significantly lowering the technical and knowledge barriers to e-commerce operations, thereby translating abstract entrepreneurial intentions into actionable steps. On the other hand, as trusted third-party institutions, these outlets enhance market credibility through standardized quality control, brand building, and logistics coordination, alleviating distant consumers’ distrust toward individual farmers. By sometimes functioning as intermediaries, such service network outlets substantially increase risk-preferring farmers’ expectations of business success, encouraging them to transform their willingness to take risks into concrete e-commerce entrepreneurial activities.

3. Regional distribution. Regional resource endowment and market opportunities are important considerations for e-commerce operations, which may affect the e-commerce operations effect of risk preference. In this paper, we refer to Qiu et al. (2024a, 2024b) study, which divides the sample into two groups: eastern and central and western based on the province where the farmers are located, and the regression results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 8. The results show that compared with the eastern region, risk preference can promote farmers in the central and western regions to conduct e-commerce business. The underlying reason may lie in the fact that regional differences essentially reflect variations in opportunity costs and the inclusive value of digital technology. In the eastern region, a mature market economy provides abundant non-agricultural employment options, resulting in high opportunity costs for farmers to engage in e-commerce operations; meanwhile, the highly saturated online market diminishes the marginal returns of e-commerce operations, reducing the attractiveness of risky ventures. In contrast, the central and western regions feature relatively simple traditional economic structures and limited non-agricultural employment opportunities, making e-commerce a “low-threshold opportunity” whose inclusive digital value is particularly pronounced. For risk-preferring farmers in these regions, the opportunity cost of engaging in e-commerce operations is relatively low, while the potential to leverage digital technologies to overcome geographic constraints and access larger markets for higher returns is strong. Consequently, their propensity for risk-taking is more readily channeled into e-commerce operations.

Based on the above analysis, the results indicate that research hypothesis 4 is supported.

4.6 Further analysis

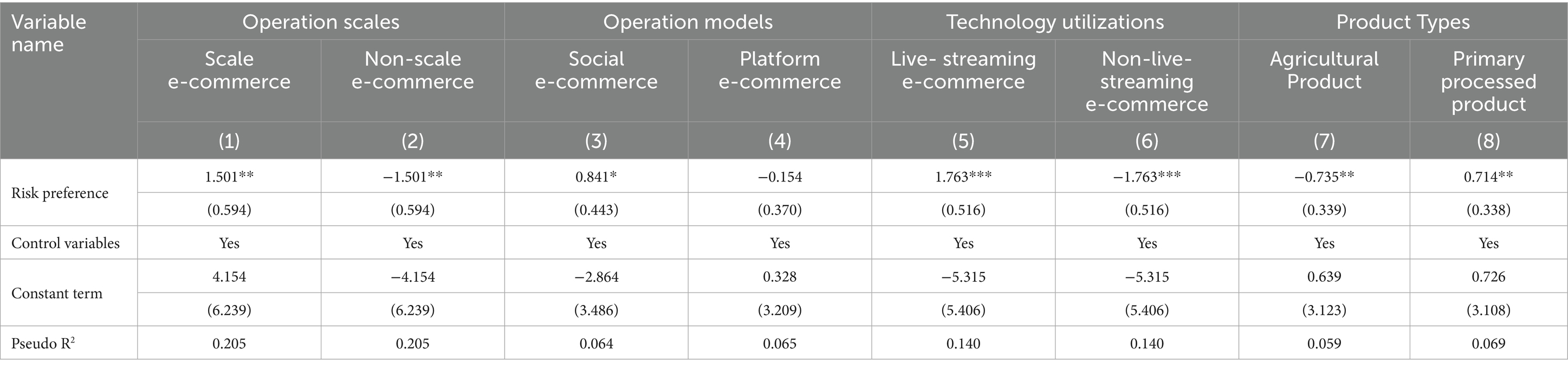

In order to further investigate the impact of risk preference on Farmers’ e-commerce operations, this paper discusses the operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations and product types.

4.6.1 Differences in operation scales

There are differences in the bargaining power and capital constraints of different e-commerce scales, which may lead to differences in the e-commerce operation effects of risk preference. Therefore, this paper takes the number of online stores as a measure of e-commerce business scale, and regards the situation that the number of online stores is greater than 1 as a scale e-commerce, on the contrary, it is a non-scale e-commerce, and, respectively, discusses the impact of risk preference on different e-commerce operation scales. The results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9. The results show that risk preference can better promote farmers’ scale e-commerce operation. Under the non-scale e-commerce operation mode, the resource allocation is concentrated on basic operation, the capital and technology threshold is low, and the risk is controllable, but the market expansion has structural bottlenecks, which is difficult to fit the decision-making characteristics of risk-preferring farmer. In contrast, scale e-commerce operations involve higher sunk costs and longer return cycles, presenting a typical high-risk, high-return profile. This model is better aligned with the traits of risk-preferring farmers, namely their higher tolerance for uncertainty and long-term income expectations. Moreover, by leveraging economies of scale, farmers can reduce unit operating costs, thereby achieving synchronous improvement in both operational scale and economic benefits. Therefore, risk-preferring farmer are more inclined to operate scale e-commerce.

4.6.2 Differences in operation models

At this stage, there are two main types of e-commerce operation models: social e-commerce and platform e-commerce (Liu et al., 2021), and there are differences in the adaptation rules and business strategies of different e-commerce models. This paper further explores the differences in the impact of risk preference on different e-commerce models, and the results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 9. The results show that risk preference are more likely to promote farmers to operate social e-commerce model. The possible reasons for this are that, on the one hand, platform e-commerce has a high degree of operational threshold and standardization, which usually requires high initial investment, such as store decoration, deposit, operating costs and continuous professional management ability, and the fixed costs and complexity of platform e-commerce also offset the incentive effect of risk preference to a certain extent; on the other hand, it lies in the fact that social e-commerce relies mainly on personal social networks such as the promotion of WeChat circle of friends. The start-up costs are low, the operation mode is more flexible, and the form of return is more direct. Therefore, risk-preferring farmer are more inclined to choose the social e-commerce model.

4.6.3 Differences in technology utilizations

As a new technological approach, live-streaming is gradually being used in e-commerce operation activities (Zhang et al., 2024). This paper further examines the differences in the impact of risk preference on different e-commerce technology utilization methods, and the results are shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 9. The results show that risk preference significantly contributes to live-streaming e-commerce operations. The possible reason is that live broadcasting, as an emerging business mode, on the one hand, breaks the geographical and time limitations of the traditional sales model, can directly face the vast consumer groups, and the sales of the products may be explosive growth, which will bring lucrative profits; on the other hand, live-streaming e-commerce has a high degree of uncertainty and risk, and the live-streaming effect is subject to multiple factors such as the anchor’s personal ability, market trends, audience preferences, etc. The effect of the live broadcast is affected by multiple factors such as the anchor’s personal ability, market trends, audience preferences, etc., and may face risks such as no one watching the live-streaming and poor sales. Therefore, risk-preferring farmers are more inclined to choose live-streaming e-commerce.

4.6.4 Differences in product types

Products with different attributes are differentiated in terms of market strategies and business objectives due to differences in their type characteristics. Therefore, this paper further examines the differences in the impact of risk preference on different types of products operated and the results are shown in columns (7) and (8) of Table 9. The results show that risk preference significantly contributes to farmers’ operation of primary processed products. The possible reason is that, on the one hand, the production of agricultural products is greatly affected by natural factors, the yield and price fluctuations are relatively large, the operational risk is difficult to control by themselves, and the return is relatively limited, the farmers’ willingness to operate agricultural products e-commerce operation is lower; on the other hand, the primary processed products are simply processed, with high added value and profit margins, and the market demand is more stable, and the shelf life is longer, the storage and transportation conditions are more flexible, which is more suitable for the pursuit of high returns by risk-preferring farmers. Therefore, risk-preferring farmers are more inclined to choose to operate primary processed products e-commerce.

5 Discussion

Against the backdrop of the “Digital Commerce for Agriculture” strategy and the rapid development of rural e-commerce, e-commerce platforms have become deeply embedded in farmers’ production activities and daily lives, emerging as a critical channel connecting them to broader markets. In this context, risk preference—a core psychological trait of farmers—plays a profound and decisive role in shaping whether and how farmers engage in e-commerce operations. This study utilizes 3,670 micro-survey observations from 10 provinces in China, employing a binary logit model combined with mediation effect analysis to systematically examine the impact of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations and its underlying mechanisms, while also investigating the heterogeneous effects across different types of e-commerce activities. On this basis, the study further compares effects across variations in operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations, and product types, providing empirical evidence for a deeper understanding of farmers’ e-commerce operations and the formulation of targeted policy recommendations.

Specifically, the study finds that risk preference has a significant positive impact on farmers’ e-commerce operations, consistent with existing literature (Li F. et al., 2023), confirming its active role in promoting engagement. Similarly, Tran and Pham (2024) also found that risk preference stimulates entrepreneurial behavior, but this study innovates by isolating e-commerce entrepreneurship from general entrepreneurship research and examining it separately. Given that e-commerce entrepreneurship possesses distinct characteristics compared to traditional entrepreneurial activities, focusing on farmers’ e-commerce operations allows for clearer causal relationships and more in-depth mechanism analysis, leading to more precise and actionable policy insights.

In terms of mechanisms, this study builds on the consensus that credit financing is an important channel for alleviating capital constraints and further explores the mediating roles of formal and informal lending in how risk preference influences farmers’ e-commerce operations. Unlike prior research that often treats lending as a single, undifferentiated factor, this study distinguishes between formal and informal financing channels. The empirical results indicate that both types of lending play significant mediating roles. Notably, informal lending demonstrates a unique financing function within rural social networks. Relationships based on kinship, friendship, and community ties can effectively reduce information asymmetry and transaction costs, providing start-up capital and improving access to funding for resource-constrained farmers (Liu and Yin, 2024; Ding and Elahi, 2025), remaining an important complement to formal financial systems in rural areas. Based on this, future policies should continue to strengthen formal financial systems while also considering how to gradually integrate informal financial activities into standardized management and risk monitoring frameworks, thereby retaining their flexibility in easing capital constraints while mitigating potential financial risks.

Furthermore, this study examines differences in the effects of risk preference across operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations, and product types, thereby extending and deepening the understanding of its influence on farmers’ e-commerce operations. Unlike existing studies that focus primarily on operational environments and resource endowments, this study innovatively incorporates risk preference into the analytical framework, examining its differentiated impact on various aspects of e-commerce activities. Risk preference reflects farmers’ trade-offs between potential gains and losses under uncertainty, and farmers with different levels of risk tolerance exhibit distinct operational strategies (Bai and Jia, 2022; Tian and Zhao, 2024). The results show that risk-preferring farmers are more likely to engage in large-scale e-commerce, social e-commerce, live-streaming e-commerce, and the sale of minimally processed products. The likely explanation is that risk-averse farmers tend to adopt conservative strategies, maintaining smaller operations to minimize market fluctuations and operational pressures, prioritizing stable returns and avoiding uncertainties associated with overexpansion (Lin et al., 2024). In contrast, social e-commerce relies on social networks and word-of-mouth, offering lower operational costs and high user retention but posing challenges in market expansion and trust-building. Farmers with higher risk preference are more willing to pursue its low-cost, high-return potential and accept the associated market risks (Shirazi et al., 2022). Live-streaming e-commerce, as an emerging mode, offers real-time interaction, rich content, and enhanced marketing effectiveness (Zhou et al., 2024), yet requires higher technical investment and operational capabilities; risk-preferring farmers are more inclined to leverage live streaming to showcase product features and attract consumers. Minimally processed products typically carry higher added value and market competitiveness (Barrett et al., 2022), but also demand stricter production techniques and quality control, which risk-preferring farmers are willing to tackle in pursuit of higher returns and growth potential.

The theoretical contribution of this study lies in revealing the influence and underlying logic of farmers’ risk preference on e-commerce-based digital economic models, expanding the analytical perspective on the intersection of the digital economy and farmer behavior, and providing new theoretical foundations for understanding operational decision-making under uncertainty. By linking psychological attitudes with digital economic practices, this study demonstrates that risk preference is not only a crucial determinant of whether farmers engage in e-commerce, but also a key factor influencing their operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations, and product types. These findings provide a theoretically grounded and empirically supported framework for developing rural e-commerce in developing countries and fostering new drivers of the digital economy, highlighting the importance of accounting for farmers’ psychological differences and risk tolerance in policy design to more effectively unlock the potential of rural digital economic development.

6 Conclusions and policy implications

6.1 Conclusion

Based on the 3,670 farmers data of China Rural Revitalization Survey, this paper explores the impact and mechanism of risk preference on farmers’ e-commerce operations, and examines its heterogeneity in road conditions, network outlet constructions, and regional distributions, based on which, it further analyzes the differences in the effects of different e-commerce operation scales, operation models, technology utilizations, and product types. Based on the above analysis, the following four conclusions are drawn.

1. Risk preference significantly promotes farmers’ e-commerce operation, and this finding remains consistent after a series of robustness and endogeneity tests. This suggests that risk preference is a key driver of farmers’ e-commerce operation.

2. Risk preference indirectly facilitates farmers’ e-commerce operation by driving both formal and informal lending. The results show that formal lending offers farmers stable financial support, while informal lending relies on social networks to alleviate liquidity constraints, both of which play a positive role in alleviating the financial bottleneck of e-commerce entrepreneurship among farmers.

3. The e-commerce operation effect of risk preference is more obvious for farmers with good road condition, good network construction and in the central and western regions. This indicates that farmers’ e-commerce operation is dependent on the external support environment.

4. The promotion effect of risk preference is more obvious for scale e-commerce, social e-commerce, live e-commerce and primary processed goods e-commerce. This also reflects the adaptability of risk-preferring farmers to emerging business methods.

6.2 Policy implications

1. Establish a tiered support mechanism to stimulate the effectiveness of risk preference. On one hand, for farmers with high risk preference, efforts should focus on pilot incentives for emerging e-commerce models. For example, a Rural Emerging E-commerce Innovation Fund can be created to support high-risk farmers in exploring social e-commerce, live-streaming e-commerce, and large-scale e-commerce. Farmers trying live-streaming e-commerce for the first time can receive platform entry subsidies and technical training to lower innovation and trial-and-error costs. Those engaged in large-scale e-commerce can be offered supply chain docking services to help expand their procurement and sales scale. For farmers operating primary processed products via e-commerce, agricultural technology extension departments can jointly provide technical packages for primary processing and offer subsidies for the purchase of processing equipment. On the other hand, for farmers with low risk preference, risk protection in traditional e-commerce should be strengthened. Since these farmers tend to favor platform-based e-commerce, the coverage of e-commerce insurance should be expanded. A rural e-commerce market early-warning system can be built using big data to monitor the supply, demand, and price trends of agricultural products in real time, and targeted alerts can be sent to low-risk farmers to help them avoid the risk of unsold products.

2. Innovate rural financial services to match funding needs precisely. On one hand, formal financial institutions should develop dedicated credit products tailored to different e-commerce types and guide commercial banks and rural credit cooperatives to offer differentiated loans. For example, for large-scale e-commerce, long-term and large-amount credit products can be introduced, using e-commerce platform transaction records as collateral to simplify the approval process. For social and live-streaming e-commerce, short-term liquidity loans can be provided to meet temporary capital turnover needs. For primary processing e-commerce, farmers can be allowed to use processing equipment as collateral and repay principal and interest in installments. On the other hand, informal finance should be standardized and empowered through social networks, using rural cooperatives and village collective economic organizations as carriers. For instance, cooperatives can establish internal lending guarantee mechanisms, providing credit endorsement and setting interest rate ceilings for member-to-member informal loans to prevent high-interest traps. For social e-commerce farmers who rely on acquaintance-based borrowing, special financial literacy training can be carried out, and a Rural Informal Lending Guide can be issued to help farmers understand legitimate borrowing procedures.

3. Improve e-commerce infrastructure with a focus on regional weaknesses. On one hand, priority should be given to upgrading core infrastructure in rural areas of central and western regions. A Central–Western Rural E-commerce Infrastructure Fund can be established to finance road and logistics construction. A three-tier cold-chain logistics distribution system—covering counties, townships, and villages—should be built in these regions. To meet the storage needs of primary processing e-commerce, constant-temperature storage units can be installed. Rural roads can be adapted for e-commerce logistics, and dedicated transportation routes for agricultural products from the central and western regions can be opened with freight subsidies for logistics enterprises. On the other hand, rural e-commerce outlets should be upgraded in a differentiated manner. In areas with good road conditions, village-level e-commerce outlets can be upgraded into smart service stations equipped with agricultural product testing devices and live-streaming equipment to support farmers in “origin live-streaming + quality traceability.” In central and western villages with weak outlet construction, a government–enterprise cooperation model can be adopted, with the government subsidizing construction costs and introducing e-commerce platforms to establish village-level service points that provide basic services such as agency operations and logistics docking.

4. Guide innovation in e-commerce models through differentiation. On one hand, efficient e-commerce models should be promoted by type. For social e-commerce, training programs can be launched jointly with platforms such as WeChat and Xiaohongshu to teach community management and content marketing skills. For live-streaming e-commerce, partnerships with platform-based e-commerce projects can provide farmers in central and western regions with live-stream traffic support and subsidies for setting up origin live-streaming studios. For large-scale e-commerce, a “E-commerce + Cooperative” model can be advanced to encourage cooperatives to integrate scattered farmers’ resources and achieve unified procurement, packaging, and sales, thereby reducing operating costs. On the other hand, the differentiated competitiveness of primary processing e-commerce should be prioritized. An Innovation Fund for Primary Processing E-commerce can be established to subsidize farmers developing differentiated products. Agricultural research institutes can offer technical guidance on primary processing to help improve product quality. A dedicated primary processing e-commerce matchmaking platform can be built to connect directly with supermarkets and community group-buying platforms, addressing sales challenges and strengthening the motivation of high-risk farmers to explore emerging products.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee affiliated with Jiangxi Agricultural University. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RP: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. BS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 22CGL027).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anh, N. T., Gan, C., and Anh, D. L. T. (2022). Multi-market credit rationing: the determinants of and impacts on farm performance in Vietnam. Econ. Anal. Policy 75, 159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2022.05.008

Arage, G., Belachew, T., Hajmahmud, K., Abera, M., Abdulhay, F., Abdulahi, M., et al. (2021). Impact of early life famine exposure on adulthood anthropometry among survivors of the 1983–1985 Ethiopian great famine: a historical cohort study. BMC Public Health 21, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09982-x

Aren, S., and Nayman Hamamci, H. (2020). Relationship between risk aversion, risky investment intention, investment choices: impact of personality traits and emotion. Kybernetes 49, 2651–2682. doi: 10.1108/K-07-2019-0455

Bai, S., and Jia, X. (2022). Agricultural supply chain financing strategies under the impact of risk attitudes. Sustainability 14:8787. doi: 10.3390/su14148787

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Barrett, C. B., Reardon, T., Swinnen, J., and Zilberman, D. (2022). Agri-food value chain revolutions in low-and middle-income countries. J. Econ. Lit. 60, 1316–1377. doi: 10.1257/jel.20201539

Caliendo, M., and Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J. Econ. Surv. 22, 31–72.

Cen, T., Lin, S., and Wu, Q. (2022). How does digital economy affect rural revitalization? The mediating effect of industrial upgrading. Sustainability 14:16987. doi: 10.3390/su142416987

Chavas, J. P., and Nauges, C. (2020). Uncertainty, learning, and technology adoption in agriculture. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 42, 42–53. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13003

Chen, X., Hu, X., and Xu, J. (2023a). When winter is over, its cold remains: early-life famine experience breeds risk aversion. Econ. Model. 123:106289. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2023.106289

Chen, X., Xia, M., Zeng, D., and Fan, X. (2023b). Citrus specialization or crop diversification: the role of smallholder’s subjective risk aversion and case evidence from Guangxi, China. Horticulturae 9:627. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae9060627

Cheng, Z., Guo, W., Hayward, M., Smyth, R., and Wang, H. (2021). Childhood adversity and the propensity for entrepreneurship: a quasi-experimental study of the great Chinese famine. J. Bus. Venturing 36:106063. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106063

Choi, J.-K., Moon, K.-K., Kim, J., and Jung, G. (2024). Examining the impact of local government competencies on regional economic revitalization: does social trust matter? Systems 13:5. doi: 10.3390/systems13010005

Daines, C. L., Hansen, D., Novilla, M. L. B., and Crandall, A. (2021). Effects of positive and negative childhood experiences on adult family health. BMC Public Health 21, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10732-w

Daskalopoulou, I., Karakitsiou, A., and Thomakis, Z. (2023). Social entrepreneurship and social capital: a review of impact research. Sustainability 15:4787. doi: 10.3390/su15064787

Ding, X., and Elahi, E. (2025). Social networks, household entrepreneurship, and relative poverty in rural China: the role of information access and informal funding. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Communic. 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-04562-z

Ding, Y., Min, S., Wang, X., and Yu, X. (2022). Memory of famine: the persistent impact of famine experience on food waste behavior. China Econ. Rev. 73:101795. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101795

Findlater, K. M., Satterfield, T., and Kandlikar, M. (2019). Farmers’ risk-based decision making under pervasive uncertainty: cognitive thresholds and hazy hedging. Risk Anal. 39, 1755–1770. doi: 10.1111/risa.13290

Foss, N. J., and Klein, P. G. (2020). Entrepreneurial opportunities: who needs them? Acad. Manage. Perspect. 34, 366–377. doi: 10.5465/amp.2017.0181

Giaccone, S. C., and Magnusson, M. (2022). Unveiling the role of risk-taking in innovation: antecedents and effects. R&D Manag. 52, 93–107. doi: 10.1111/radm.12477

Guo, N., and Chen, H. (2022). Comprehensive evaluation and obstacle factor analysis of high-quality development of rural e-commerce in China. Sustainability 14:14987. doi: 10.3390/su142214987

Guo, J., and Chen, J. (2025). Living through the great Chinese famine: the long-term effects of early-life experiences on household consumption. Appl. Econ. Lett. 106, 1–6. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4557194

Guo, L., Sang, B., Li, S., Xia, Z., Li, M., Yang, M., et al. (2024). From starvation to depression: unveiling the link between the great famine and late-life depression. BMC Public Health 24:3096. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-20604-8

Gupta, S., Rikhtehgar Berenji, H., Shukla, M., and Murthy, N. N. (2023). Opportunities in farming research from an operations management perspective. Prod. Oper. Manag. 32, 1577–1596. doi: 10.1111/poms.13967

Hui, M., and Yong, F. (2023). Risk preferences and the low-carbon agricultural technology adoption: evidence from rice production in China. J. Integr. Agric. 22, 2577–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.jia.2023.07.002

Khanal, A. R., Mishra, A. K., and Lien, G. (2022). Effects of risk attitude and risk perceptions on risk management decisions: evidence from farmers in an emerging economy. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 47, 495–512.