- 1Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 2Institute of Geography, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 3Alliance of Bioversity International and International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Lima, Peru

- 4Department of Environmental Systems Science, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Improving farmer wellbeing presents a key focus for improving the sustainability in cocoa value chains, both as a goal in itself and given the role of farmers as key agents in wider sustainability transformations. While evidence on the effects of private sustainability governance strategies abounds, much less is known about the causal mechanisms producing or inhibiting such effects. Research in organizational psychology and management studies points to the importance of whether farmers feel treated in a fair manner by their buyers and the extent to which such fairness and justice are institutionalized in governance strategies. Our study therefore draws on theoretical insights from the interdisciplinary justice literature to develop hypotheses on the role of distributive, procedural and recognition justice in moderating wellbeing effects in key private sustainability governance strategies: cooperatives, corporate sustainability programmes, and social entrepreneurship. We conduct process tracing utilizing both qualitative and quantitative data to compare three case studies in a main cocoa producing region in the Peruvian Amazon. Our results support the hypothesized positive influence of justice attributes in all three dimensions as we elicit distinct causal mechanisms through which practices institutionalizing distributive, procedural and recognition justice enhance farmers’ wellbeing, satisfaction and commitment. In contrast to some earlier work, the results suggest that most farmers consider distributive attributes as more important than procedural or recognitional elements. An emergent theme from the research further suggests that farmers expectations in terms of just treatment are differentiated by the type of buyer, with cooperatives being held to a higher standard than private companies.

Introduction

Globally consumed tropical agricultural goods such as cocoa and its derivates are often in the focus of debates about the social and environmental (un)sustainability of food systems (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). A main social sustainability issue of agricultural value chains concerns the wellbeing of small-scale farmers, many of whom are affected by poverty, livelihood insecurity, exploitative working conditions, and social inequalities (Gneiting and Arhin, 2023; Charry et al., 2025). Improving farmers’ wellbeing and the social sustainability of agricultural value chains overall thereby also demonstrate important connections to the global sustainability agenda, and specifically, several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 1 (No Poverty), 2 (Zero Hunger), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), 13 (Climate Action) and 15 (Life on Land). Similarly, in response to increasing pressure from consumers, civil society, and governments to ensure the sustainability of their sourcing operations, firms have developed and adopted various sustainability strategies, i.e., distinct approaches to pursue sustainability goals in their value chains (Kuit and Waarts, 2014; Thorlakson, 2018). Key private-sector strategies to promote sustainability outcomes in agricultural value chains include third-party certification, corporate sustainability programmes, and social and solidarity economy initiatives associated with cooperatives and social entrepreneurship (Bager and Lambin, 2020; Oberlack et al., 2023).

While research on main features and effects of different strategies abound (e.g., Blackman and Rivera, 2011; Donovan et al., 2017; Ruben, 2017; Wright et al., 2024), much less is known about the causal mechanisms that link such strategies with sustainability outcomes. This is problematic as many studies have demonstrated limited, mixed, or even adverse effects of private-sector strategies (Oya et al., 2018; Meemken et al., 2019; Middendorp et al., 2020; Sellare et al., 2020). In light of such results, studies that tried to “dig deeper” have demonstrated that even where interventions generate positive outcomes, such as in terms of increased yield and productivity, they can leave farmers dissatisfied where interventions elicited perceptions of unfair treatment (Thorpe, 2018). Such findings resonate with studies in the organizational and psychology literature which show that within firms and in supply chain relationships, satisfaction and behavior of employees and chain partners are shaped not only by received benefits, but also – and importantly – based on whether they experience the distribution of rewards and burdens, processes defining such distributions, and their treatment overall, as fair (Colquitt et al., 2001; Fearne et al., 2004; Hornibrook et al., 2009). While bearing potentially important lessons for studying the effects of governance strategies in agricultural value chains, insights from this organizational and supply chain justice literature have only seldom been considered by sustainability governance scholars (Kröger and Schäfer, 2014; Thorpe, 2018).

The present article proposes to draw on this literature to examine the role of justice in moderating wellbeing effects of sustainability strategies on cocoa farmers. Our main research question is: How does justice in cooperatives, company programmes and social enterprises influence farmers’ wellbeing? Building on existing theory on the effects of justice in organizational and supply chain settings, we employ a comparative case study design using process tracing (Beach, 2017) to examine potential causal mechanisms linking sustainability strategies with the wellbeing of cocoa farmers. We compare three key strategies – cooperatives, corporate sustainability programmes and social enterprises – combining quantitative data from a household survey with qualitative interview data on three cases located in a main cocoa production area in Peru, a major producer and exporter of raw cocoa with a significant presence of all three strategies under investigation (Oberlack et al., 2023).

Our study adds to the existing literature in sustainability governance of agricultural value chains by elucidating how the institutionalization of fair distribution, just procedures and recognition of farmers in sustainability strategies distinctly enhance farmers’ wellbeing. Somewhat in contrast to an earlier study which emphasized the role of procedural justice for farmer satisfaction (Thorpe, 2018), we find that farmers perceive distribution in general, and prices and material services in particular, as most important for their wellbeing. Finally, our findings speak to the organizational, supply chain and value chain justice literature by demonstrating that farmers’ satisfaction and perception of buyers are importantly shaped by their expectations about buyers based on the latter’s nature, with cooperatives seemingly being held to higher standards than private companies (Colquitt et al., 2013; Gimenes et al., 2022).

Theoretical framework

Wellbeing of farmers in cocoa value chains

Improving the living conditions of small-scale farmers who produce the vast majority of cocoa and most of the world’s food, remains a key focus of sustainability efforts in these sectors – both as a goal in itself, and as farmers are considered key agents for wider sustainability transformations (Mills et al., 2021; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). Yet, interventions and strategies to include farmers in more sustainable value chains remains a challenge, both from a societal perspective – in light of inconsistent results on the effects of different strategies (Bernard and Spielman, 2009; Meemken, 2020) – and from the viewpoint of firms and cooperatives, who struggle to keep farmers committed to their organizations (Hansen et al., 2024).

Addressing this double challenge requires, as a first step, conceiving of farmer-level outcomes holistically in terms of their overall life satisfaction or wellbeing, rather than, e.g., measures on their income and productivity (White, 2010; Talukder et al., 2020; Valizadeh and Hayati, 2021). A move away from a compartmentalized and outsider ascription of what positive outcomes represent, a wellbeing focus fundamentally centers in the person and recognizes the multiplicity and integrity of people’s lives (White, 2010). Established wellbeing frameworks therefore go beyond material aspects to encompass relational and subjective dimensions of wellbeing (McGillivray, 2007). Indeed, one of the most widely used frameworks in wellbeing research – the Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) is entirely based on subjective assessments of life satisfaction with regard to a variety of aspects, such as standard of living, health, life achievements, personal relationships, personal safety, community integration, and future outlook (International Wellbeing Group, 2013).

Work satisfaction, or the experienced relationship quality with employers, and in the case of farmers, with powerful buyers to whom they sell their produce, plays a key role for wellbeing (Stahlmann-Brown et al., 2025). Satisfaction with value chain partners also importantly shapes commitment and continued investment into the chain relationship (Hernandez-Espallardo et al., 2013). Where satisfaction is low, and other options are available, farmers may disengage from cooperatives or company programmes, and potentially forego positive long-term effects from continued commitment, if not hampering their trust in “more sustainable” value chains altogether (Thorpe, 2018).

Justice in organizations and supply chains

The “million-dollar question” for sustainability transformations of food value chains therefore boils down to: what is it that truly shapes farmers wellbeing, satisfaction and commitment? Research in psychology, management and organizational studies highlights the important role of perceptions of fair treatment, or justice, operating as a mediator between employers’ or supply chain partners’ performance in terms of outputs (such as received benefits) on the one hand, and outcomes (such as satisfaction and wellbeing) and behavior (such as commitment) among employees and weaker chain partners on the other (Colquitt et al., 2001; Yilmaz et al., 2004). Similarly, research on indicators of agricultural sustainability have repeatedly demonstrated that indicators for farmers’ wellbeing and equity are closely strongly linked to each other and agricultural sustainability overall (Talukder et al., 2020; Valizadeh and Hayati, 2021, 2025). These subjective or “micro-level” effects of justice may be of particular importance in supply chains with stark power asymmetries, as weaker parties – often lacking alternative strategies such as vertical integration – fundamentally rely on chain partners’ sense of fairness (Kumar et al., 1995).

Such power asymmetries also apply to most value chains for food and agricultural products (Grabs and Ponte, 2019). Food and agriculture have historically also been at the forefront of calls for justice at a more macro-level put forward by writings and activism on food and environmental justice (Schlosberg, 2007; Allen, 2008; Matthews and Silva, 2024). For cocoa and other tropical food value chains, these calls are perhaps most prominently embodied in the Fair Trade movement (Fridell et al., 2021). Responding to inequalities and poverty of farmers, the movement emerged to “re-embed” global supply chains in institutional arrangements and farmer-buyer relationships built quite explicitly on justice principles (Jaffee, 2007). Whereas the success of the modern-day Fairtrade label and other certifications in realizing such principles has been a long-standing topic of debate (Kröger and Schäfer, 2014; Bennett, 2017), this perspective suggests conceiving of strategies of sustainability governance also beyond certification as efforts to “institutionalize” justice differently and to various degrees, such as cooperatives, corporate sustainability programmes and social entrepreneurship. Tying these considerations on the “macro-level” back to theoretical and empirical insights on the role of justice in subjective terms may suggest, in turn, that those strategies that most strongly reflect justice principles also achieve the highest wellbeing effects. In the remainder of this section, we elaborate on this overarching conjecture and break it down into hypotheses on causal mechanisms for empirical examination.

Theoretical perspectives on the role of justice for farmer wellbeing

Most studies across disciplines conceptualize justice as multi-dimensional. The two dimensions that have received most attention are distributive justice, i.e., fairness in terms of how rewards and burdens are distributed, and procedural justice which refers to the fairness of the processes determining those distributions (Leventhal, 1980). A third commonly used dimension is recognition justice, which encompasses respect toward individuals, but also broader, e.g., cultural and group-level recognition in contexts marked by social inequalities as particularly prevalent in a post-colonial context (Schlosberg, 2007; Lyon, 2009; Birthwright, 2023).1 For the purpose of this research, we therefore use this multi-dimensional conceptualization and, building on the various disciplinary perspectives introduced, we define value chain justice chains as the institutional design and management of private sustainability governance strategies according to principles of distributive, procedural, and recognition justice (Matthews and Silva, 2024).

Corporate sustainability programmes, cooperatives and social enterprises may institutionalize principles of distributive, procedural and recognition justice in different ways and to varying degrees. While such institutionalizations differ from case to case, a recent survey comparing institutional practices among strategies in the cocoa and coffee sector (Montoya-Zumaeta et al., in press) revealed that corporate programmes predominantly address distributive aspects, such as premiums paid on top of market prices, and services aimed at supporting production, such as trainings, technical assistance, and subsidized inputs. Cooperatives typically provide similar distributive benefits (though their quality and quantity may often be limited by resource constraints; Bernard et al., 2008), but are fundamentally based on co-ownership and elements of democratic governance of farmers reflecting principles of procedural justice (Bruelisauer et al., in press). Social enterprises, i.e., businesses that have been established typically with a primary purpose of promoting societal objectives (Defourny and Nyssens, 2023; Bennett and Grabs, 2024), often incorporate particularly strong aspects of both distributive and procedural justice, such as fixed above-market prices and including wider communities in decision-making (Bruelisauer et al., in press). Moreover, cooperatives and social enterprises often also address recognition-related injustices, e.g., by linking farmers directly with consumers and challenging post-colonial farmer imagery (Lyon, 2013).

Theory drawn from the organizational and supply chain literature suggests that practices perceived as just within all three dimensions will positively influence farmer wellbeing, satisfaction and commitment (Colquitt et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2006). Although studies measuring the effects of justice directly on wellbeing are rare (Sora et al., 2021), relevant literature provides sufficient insights to derive hypotheses on the mechanisms through which justice dimensions may affect different wellbeing components within the PWI framework. Attributes of distributive justice – such as remuneration, support systems and investment opportunities – can be expected to particularly influence wellbeing associated with standard of living, health, life achievements, and future outlook (Bloom and Hinrichs, 2011; Kröger and Schäfer, 2014). Procedural justice attributes – including long-term commitment of buyers, bilateral communication and shared decision-making, and transparency – may predominantly enhance personal safety and future outlook (Kumar et al., 1995; Thorpe, 2018). Recognition-related elements, finally, may most strongly impact life achievements, personal relationships community integration, and religious or spiritual life (Brown et al., 2006; Stevenson and Pirog, 2008). Based on the theoretical predictions developed above, we can develop the following hypothesis on the causal mechanisms through which justice institutionalized in these strategies moderates their effects on wellbeing:

H1: Attributes of distributive justice have a positive effect on wellbeing by improving farmer satisfaction on living standard, health, life achievements and future outlook.

H2: Attributes of procedural justice have an additional positive effect on wellbeing by improving farmer satisfaction on personal safety and future outlook.

H3: Attributes of recognition justice have an additional positive effect on wellbeing by improving farmer satisfaction on life achievements, personal relationships, community integration, and religious or spiritual life.

More disagreement exists in the literature about which justice dimensions are most important, and how they may interact. For instance, an early model stipulates that justice in distributive attributes, such as price, are generally more important than procedures, particularly where actors are simply concerned with their short-term survival (Brown et al., 2006). This may often be the case with small-scale farmers who are often short on liquidity and may be forced to seek whatever highest price and disregard expected long-term commitments (Jaffee, 2007). Many studies have, however, challenged this “distributive dominance” (Colquitt et al., 2001), suggesting that in longer-term relationships, procedural concerns may, as time goes by, trump distributive ones (Yilmaz et al., 2004; Hornibrook et al., 2009). Moreover, where outcomes depends on various factors beyond the control of the value chain partner, as is the case in agricultural supply chains dominated by global market prices, buyers may not be at the center of the blame for distributive injustices (Fearne et al., 2004; Thorpe, 2018). Procedures, in contrast, are “longer-lasting” and perceived to be under more direct control of the buyer (Tyler and Lind, 1992; Kumar et al., 1995). Taken together, procedural justice concerns may therefore gain importance for wellbeing, commitment and satisfaction over time, and may more strongly “backfire” than distributive concerns of farmers. To explore these contrasting predictions on the “dominance” of either distributive or procedural justice attributes, we also test the following hypothesis:

H4: Attributes of distributive justice have a higher effect on wellbeing than attributes of procedural justice.

Methodology

Given that our focus does not lie on the wellbeing effects of strategies themselves, but on the moderating role of justice institutionalizations and perceptions as potential causal mechanisms producing those effects, we use theory-testing process tracing in a comparative mixed-methods case study design drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data (Lieberman, 2005; Beach, 2017). Compared to other methods used to establish causality, such as statistics or experiments, process tracing draws on within-case evidence which allows to exploit the temporal sequence of events (such as wellbeing improvements before and after joining an organization), the combination of factors leading up to a certain result, and explicitly account for intermediate and moderating effects (Beach and Pedersen, 2013; Méndez-Lemus and Vieyra, 2014). While within-case evidence may provide valuable insights on causal mechanisms, establishing causality that can be generalized beyond cases requires systematic comparison to other cases that are most or least similar in terms of contextual factors (Bennett and George, 1997; Beach, 2017) and further benefits from a combination of quantitative data with qualitative insights to obtain a more in-depth analysis of causality (Méndez-Lemus and Vieyra, 2014).

Case selection

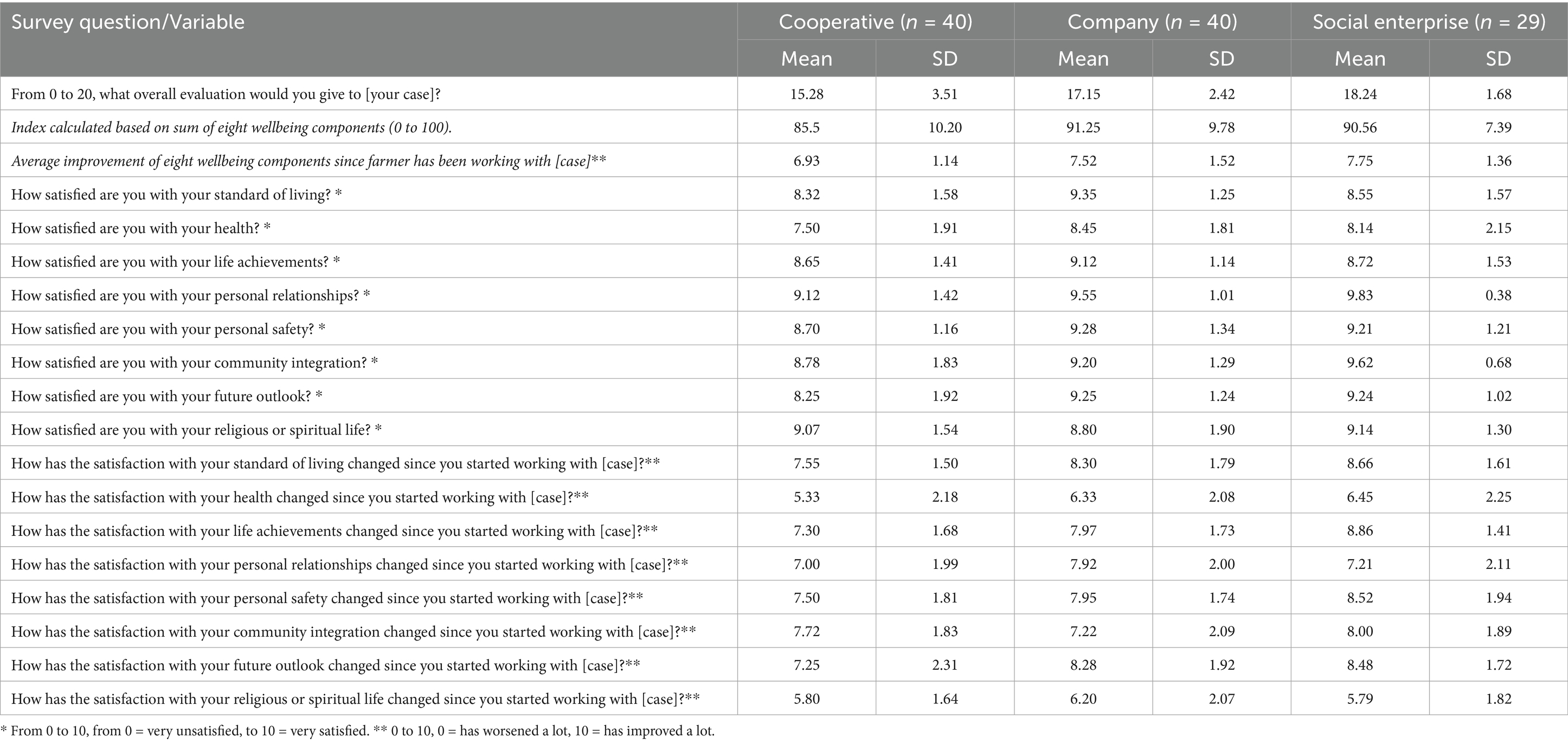

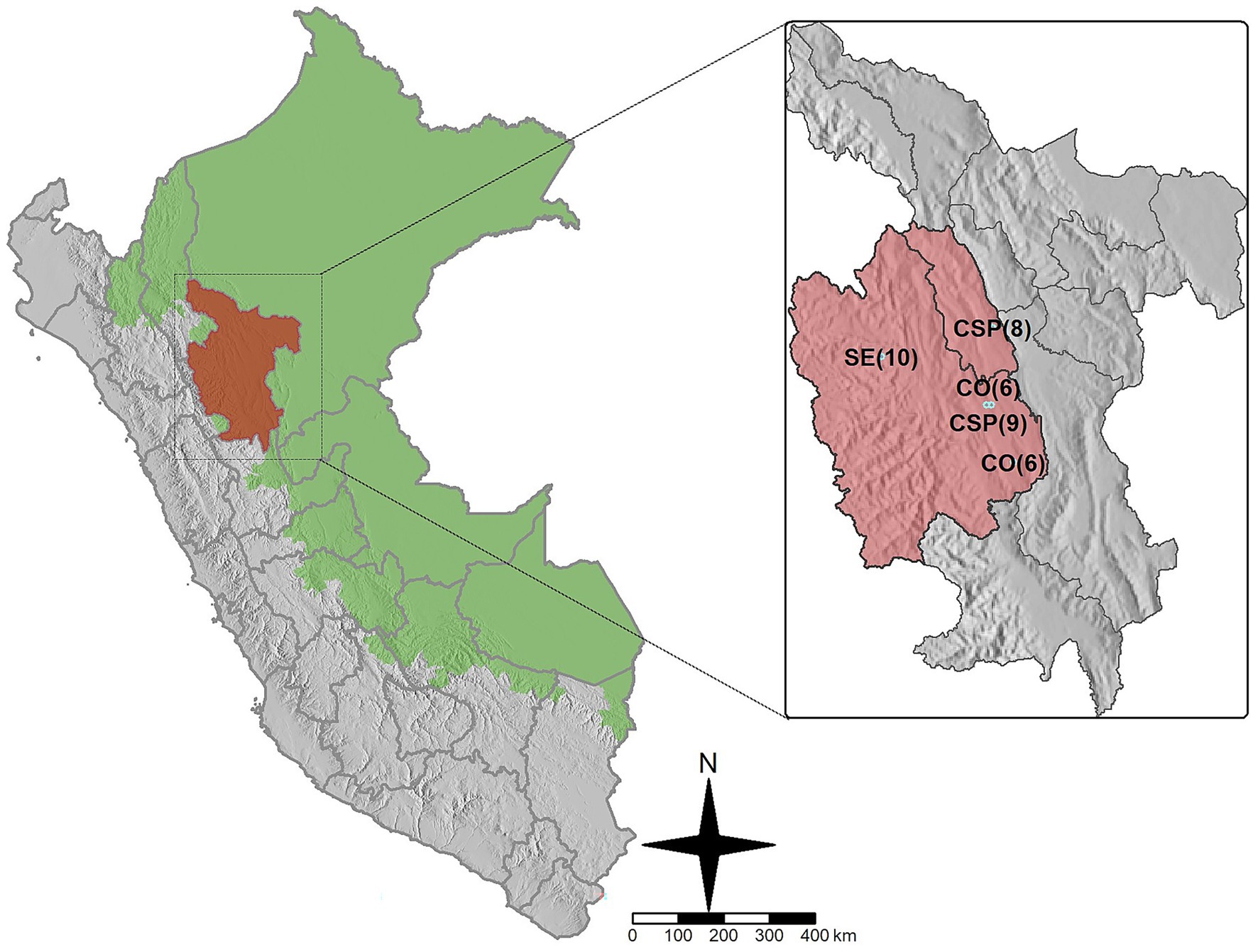

The empirical evidence in this paper was collected in the frame of the COMPASS project2 which aimed to compare wellbeing effects of different governance strategies on coffee and cocoa farmers’ wellbeing. The case selection for the process tracing could benefit from prior large-N studies on the institutional characteristics of actors and strategies in the Peruvian cocoa sector (April 2022–March 2023; for detailed sampling procedure see Bruelisauer et al., in press), and on a household survey on the wellbeing of farmers affiliated with a subset of 18 cases representing cooperatives, corporate programmes and social enterprises (August–October 2024; for detailed sampling procedure see Montoya-Zumaeta et al., in press). Our case selection for the qualitative case study comparison draws on methodological recommendations for nested analysis, a mixed-method strategy for deeper case comparison on a subset of observations (Lieberman, 2005; Gerring and Cojocaru, 2016). We therefore first selected a study region that allowed for comparison across cases that were located near each other in the San Martín department, Peru (see Figure 1). We then used data from both surveys to identify three cases that are representative of each strategy and analytically relevant for process tracing following Beach (2017) who suggests to consider both positive and deviant cases regarding the hypothesized causal links. We therefore selected cases with different degrees of justice institutionalization (Table 1) corresponding to varying wellbeing results (Table 2) which in one case support the hypothesized links (a social enterprise with high wellbeing and improvement and justice institutionalization in all three dimensions), but does so only to a limited extent in the other two cases (a company programme with high wellbeing and wellbeing improvement, but justice institutionalization in mainly the distributive dimension, and a cooperative with comparably lower wellbeing and wellbeing improvement and justice institutionalization mainly in the distributive and procedural dimensions). Interestingly, however, and highlighting the need for deeper engagement with the cases in qualitative fashion, the picture seems more aligned when focusing not on wellbeing or wellbeing improvements, but the extent to which farmers reported that they attributed a certain change to their case, where cooperative members reported a relatively high influence of the cooperative on several wellbeing aspects (Table 3). Finally, several farmers in the company and the social enterprise are former members of the cooperative, allowing for tracing the temporal sequence of justice and wellbeing perceptions. Similarly, data collection took place few months after a historical surge in cocoa prices (i.e., between August and November 2024), which facilitated understandings of wellbeing effects derived by farmers before and after the surge.

Figure 1. Location of study sites with number of interviews conducted for each case in different producer communities within San Martín department, Peru. CO, cooperative; CSP, corporate sustainability programme; SE, social enterprise.

Case study overview

The cooperative was established in 1997 with significant support of international cooperation aimed at substituting the then very prevalent production of coca in the area with cocoa in what has become known as Alternative Development Programmes. In 2024, it counted 1,500 members, approximately 25% less than in 2022. Its core business is the collection and export of Organic and Fairtrade-certified cocoa beans, while it sells non-Organic produce to a national buyer. The cooperative’s manager has overseen all managerial and commercial activities since its inception, while presidents and members of elected councils overseeing operations change on a regular basis. The cooperative is organized in 50 local committees consisting of 20–50 farmer members located in different areas in San Martín. Each committee twice a year elects a representative number of delegates to the Delegate’s Assembly, the formally highest body of the cooperative, comprising 100 delegates elected for a maximum of 2 years. The Delegate’s Assembly is in charge of electing the administrative councils, approving the budget and deliberating on the use of the Fairtrade premium as foreseen by Fairtrade regulations. Its main services for farmers include regular production-related trainings, on-farm technical assistance, small credits, and various forms of mutual insurance. The cooperative typically also runs several time-bound projects funded by government, international development agencies, or clients. Farmers are expected to deliver their entire harvest to the cooperative where it is screened for quality and rejected only in case of significantly subpar quality. Entry into the cooperative is open to new members, each of whom must go through a two- to three-year transition period before they receive the Organic premium, paid twice a year as a fixed amount per kilogram of delivered cocoa. The cooperative maintains a strict regime, however, on excluding members who have been found to use non-permitted inputs without a warning.

The corporate sustainability programme was developed in 2018 by a Peruvian company with majority ownership by a Swiss cocoa trader with financial support from a large Swiss client. Farmers in the programme benefit from regular trainings and on-farm technical assistance, as well as so-called “incentives” or benefits in the form of fertilizer or equipment given to farmers for free in exchange for their loyal delivery of quality cocoa beans. Several staff members and many farmers in San Martín were members/workers of the cooperative before switching to the company in the past years. The company requires affiliated farmers to deliver their entire cocoa harvest and also accepts subpar quality. Prices roughly follow international market prices with no fixed premium paid to farmers. The company and the programme do not maintain any elected boards or participative structures; farmers are invited to make their complaints vis-à-vis staff or through an anonymous suggestion box at the collection centre.

The social enterprise consists of a shareholder company based in Switzerland and a Peruvian cooperative that owns approximately a third of the shareholder company’s shares. It has been established in 2015 by two European social entrepreneurs together with a group of farmer families, most of whom were once organized as a local committee of the large cooperative described above, which was discontinued in light of several disagreements with management. From its inception, the social enterprise has pursued a social mission aimed at improving the wellbeing of its farmer members. This mission is enshrined in the farmers’ co-ownership in the Switzerland-based company and far-reaching decision-making by farmers, including on price setting. The core business model of the social enterprise is the marketing of high-quality chocolate using the cocoa of its farmer-members. The social enterprise has for a long time delivered an exceptional amount and quality of services to its members, as it benefited from the inflow of project and startup funds. Similarly, for years it paid one of the highest prices paid to farmers in Peru, sometimes exceeded the local market price by more than 50%. With the historical price hike in 2024, however, several members exited the social enterprise as members initially decided to not match the rising market price given emerging financial constraints. As a result, the social enterprise lost around a quarter of its membership and in November 2024, counted only 29 remaining farmer-member families.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Qualitative data for the purpose of the process tracing was collected in November 2024 through 43 interviews conducted with farmers and managers of the three cases, as well as additional non-participant observation and documentation. The interviews with farmers were based on an interview guide comprising questions on producers’ evaluations and importance given to various attributes of distributive, procedural and recognition-related justice for their wellbeing, satisfaction and commitment. Interviews with farmers were with few exceptions conducted in farmers’ homes. Interviews with managers, documentation and non-participant observation during assemblies and meetings were used to complement data from the organizational survey and integrated managers’ perspectives.

Interviews were transcribed and coded by the same two co-authors who had conducted the interviews, one Peruvian national and Spanish native speaker, the other fluent in Spanish and with repeated exposure to the study sites. Transcripts were coded using MaxQDA 24 (Verbi Software, 2023), a software to link qualitative data to research codes and themes. We followed standard recommendations for qualitative content analysis as has been applied to process tracing in other cases (Mayring and Fenzl, 2019; Silva and Strong, 2025). In a first round, we coded interviews using a set of a priori codes that covered (a) to what extent farmers considered different attributes as just and (b) the importance of different justice attributes for their wellbeing. While doing so, we identified additional emergent themes which we applied to all transcripts in a second round of coding. We also leveraged responses from the household survey on farmers’ justice perceptions, which are presented alongside the interview data.

In presenting results, we refrain from providing quantitative assessments of the interview data (such as the percentage of respondents) who discussed a certain theme to avoid the risk of misrepresenting its overall prevalence, unless there was a striking majority that did so (Silva and Strong, 2025). We selected quotes based on clarity and representativeness; quotes are contextualized with an explanation describing the case, gender and role (F for farmer, M for manager) of the interviewee, and a unique identifier (e.g., F3-7). To focus on the specific contributions of the distributive, procedural and recognition attributes, we present the findings in three sections corresponding to these dimensions.

Results

Mechanisms associated with distributive justice

The majority of farmers within and across organizations highlighted the price they receive for their cocoa as the single most important factor for improving wellbeing. Besides generally improving their wellbeing, interviewees also explained the different specific benefits it provided to them, covering basic needs, health, education for children, better housing, investing in the farm and paying laborers, as well as savings for the future.

“Of course, the price is important. All the work that we do is for [the price], for money, to have a better quality of life, so that it is enough for all your necessities. And it’s just this that is our primary motive to work” (female farmer of social enterprise, F3-7).

Some members of the cooperative mentioned this importance in a way to justify their side-selling through the higher price received elsewhere, notably for the same or lower qualities. Further, farmers across cases mentioned that low prices in the past had made them divest from cocoa, arguing that prices simply did not suffice. Indeed, more than three quarters of interviewed farmers indicated that before the price surge that occurred in early 2024, prices were neither just nor sufficient to cover costs, several reporting that they had or were planning to reduce investments in cocoa. A notable exception, three farmers responded that prices were already just or sufficient before 2024, all from the social enterprise.

Interviewed farmers were also asked what they consider a just way of defining prices. Many of them kept referring to a specific level, with some of them also arguing that it could be lower than at the time, though it would generally have to be “rentable,” roughly translatable to profitable. Several farmers in turn explained this logic by referring to the rising costs of input and labor, calling for a price-setting mechanism based on costs rather than a global market price, as is typically the case. Others also pointed to the problem of high volatility of market-based prices, and wished for prices stabilize at a level that producers benefit sufficiently.

“I couldn’t say value chains are currently just, because one day the price goes up, goes down, goes up, goes down so that one doesn’t recover” (male farmer of cooperative, F1-2).

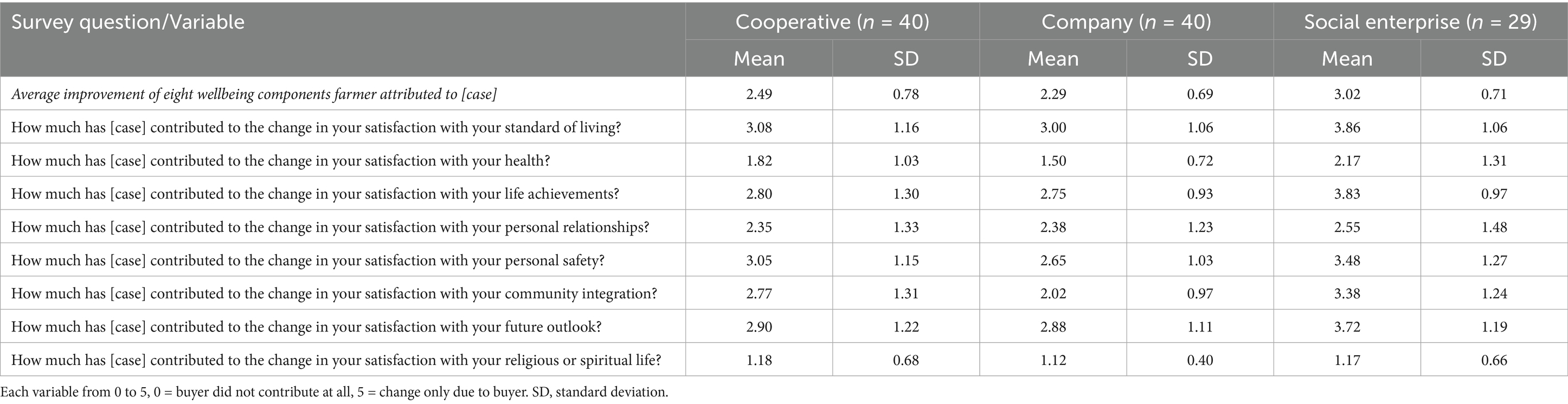

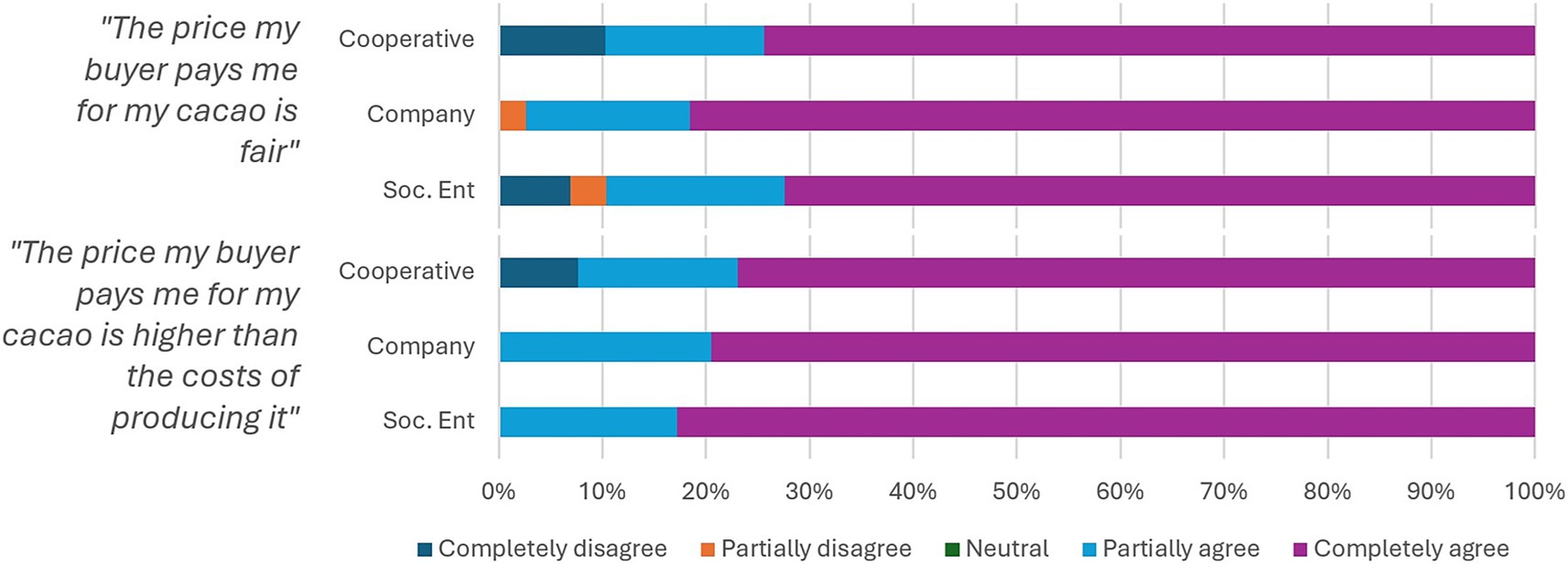

The only ones not suffering from such ups-and-downs, farmers affiliated with the social enterprise emphasized the positive effect of receiving a fixed above-market price, but also of the bottom-up price mechanism itself. The emergent patterns on the link between remuneration on the one hand, and wellbeing, satisfaction and commitment on the other, are also reflected in the farmers’ responses in the household survey, where discontent with prices are most pronounced in the cooperative, with 8 and 10 percent considering the price not high enough to cover costs, or not just, respectively (see Figure 2). However, large majorities of farmers across farmers partially or completely agree that prices currently do cover costs and are just. Interviews make sense of these responses in so far as farmers often responded by referring to the price being just or high enough as it was at the time of research, i.e., after the price surge.

Figure 2. Agreement with statements on price among farmers associated with cooperative (n = 39/n = 39), company programme (n = 38/n = 39), and social enterprise (n = 29/n = 29).

When discussing the quality and justice of different services and benefits, farmers affiliated with the social enterprise revealed the highest satisfaction, closely followed by the company. Whereas company- and social-enterprise-affiliated farmers explained how much they benefitted from trainings and technical assistance by gaining knowledge and improving their standard of living through better farming practices, several cooperative members were rather critical. Whereas some reported that they felt technical assistants were either badly trained or mostly came to control rather than help, or that they felt trainings were repetitive and rarely useful.

In the company and the social enterprise which also provided material benefits to farmers, responses from many farmers reveal they associated the strongest wellbeing effects from these as compared to trainings and assistance, such as free or subsidized inputs and equipment. Interestingly, among farmers that had left the cooperative these were – besides price motives – also the most-often mentioned reason for joining the company programme, and for leaving the cooperative. As several members of the cooperative and former members now affiliated to the company pointed out, the quality and quantity of services delivered had decreased in recent years. Farmers who stayed with the cooperative reported that this led to some disenchantment whereas farmers now affiliated to the company explained as the primary reason for their change of affiliation.

Other interesting mechanisms on wellbeing effects of services emerged from the interviews with farmers of the cooperative and the social enterprise. These mechanisms focus not so much on the delivery of support by the organization itself, but rather the coordination of mutual support among farmers. In the social enterprise, one farmer emphasized the importance of the labor sharing practices (faenas) whereby members coordinate among each other who and when they would help other members in conducting farm work. This would allow for larger production and the certainty to be able to harvest and sell cocoa which they associated with general standard of living. Similarly, farmers of the cooperative and the social enterprise to the importance of health and social insurance schemes based on mutual support. This was strongly associated by farmers with improvements in health and future outlook. One farmer from the cooperative explains the mechanism as follows, attributing the mechanism as something truly peculiar about cooperatives in general:

“If A or B has an accident, the cooperative coordinates with members to make a collection to support. This can be for anything, for when a member passes away or for health reasons […]. Because if you are part of another organization that is not a cooperative, there is no [such support] … it’s just about selling your grain” (female farmer of cooperative, F1-3).

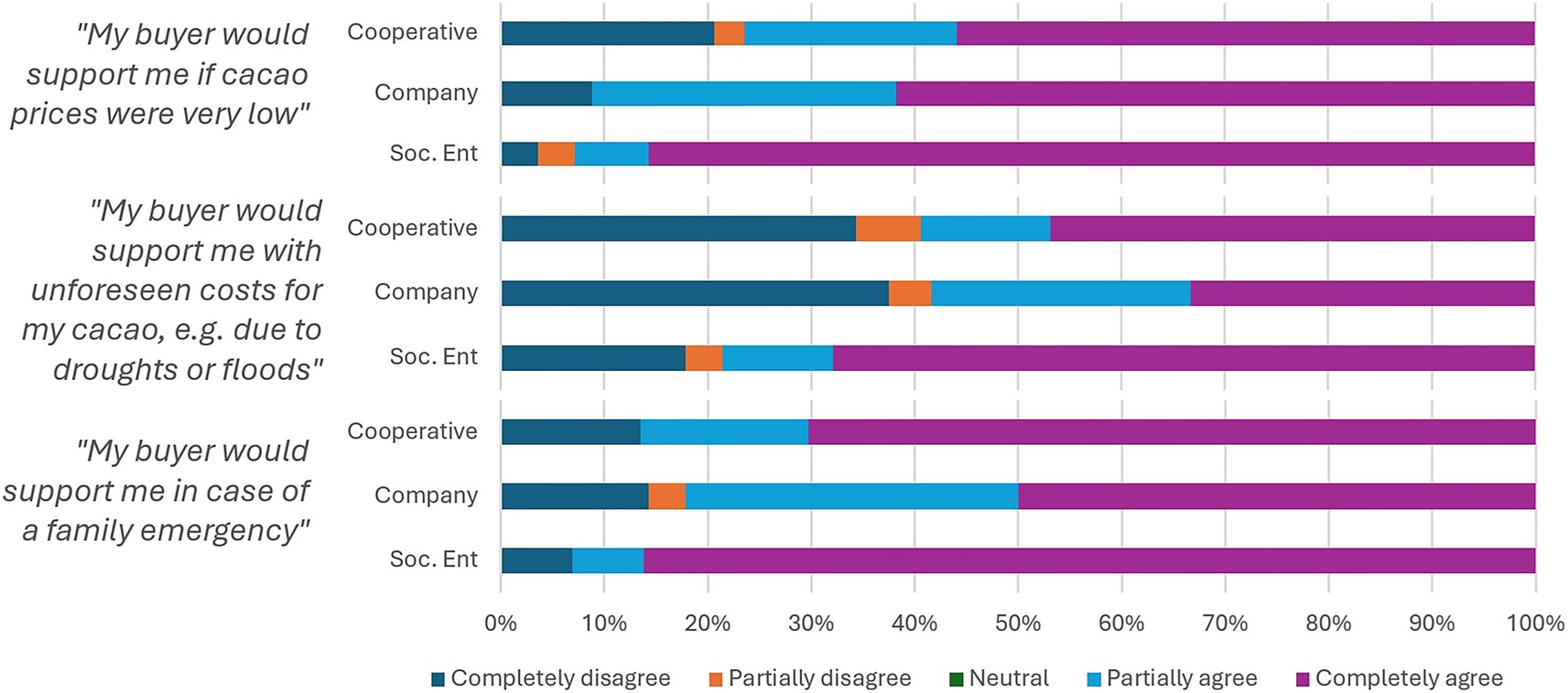

Another – generally very critical – member of the cooperative, associates this mutual support further with the community integration and personal relationships fostered by the cooperative. “If something happens, we are all there united to support this member” (F1-5). The security derived from these mutual support schemes in the cooperative and the social enterprise were also reflected in the household survey, where the feeling of being supported by the buyer was inquired through three items: about felt support in case of a sudden price drop, in case of sudden cost increases, or in case of (other) emergencies occurring. Here we observe that farmers affiliated with the social enterprise respond most affirmative about their buyer’s support, followed by cooperative members who are more confident that they would be supported in case of a sudden cost shock or an emergency than company-affiliated farmers (see Figure 3). As one of the latter put it, he indeed would welcome an element in the company’s practices that would allow for some sort of insurance in case of sickness.

Figure 3. Agreement with statements on support from buyer among farmers associated with cooperative (n = 34/n = 32/n = 37), company programme (n = 34/n = 24/n = 28), and social enterprise (n = 29/n = 28/n = 29).

An emergent theme pointed to the potential role of distributive attributes in terms of providing for investment opportunities outside of farming. One long-standing member described how for them this led to a more general “lever” effect, as the cooperative supported them throughout the years in growing production and income from cocoa, but also to diversify their income through credits and small projects received from the cooperative which were strongly associated with improvements in terms of life achievements and standard of living.

Mechanisms associated with procedural justice

Farmers emphasized various wellbeing benefits from being associated with an organization or enterprise through a formal or informal long-term agreement (an attribute of procedural justice in itself), including related to their standard of living, improved personal safety and future outlook. Particularly members of the cooperative who had on average been affiliated for a longer time expressed a strong sense of gratitude toward the organization as they felt that it had played a significant role in promoting their overall wellbeing. This was due to various reasons, as several members reported. Importantly, the cooperative had provided farmers with a perspective to replace coca leaf with cocoa production, leading to a higher sense of personal safety. Further, the importance of organizations being rooted in the region historically and/or by having permanent facilities emerged during interviews. Two farmers put this as having your harvest and sales “insured,” as the buyer is always around and will always buy the produce; in contrast, other buyers would come and go – as another farmer put it, like pájaros de volada, or “birds in flight” (F1-6).

In the social enterprise, several interviewed members expressed that being able to decide collectively made them feel treated in a just way, and made them accept it when prices in turn could not keep up with the market. Moreover, farmers would not only take their own benefit into account but feel responsible for the cooperative’s survival as well. In line with this sense of responsibility, interviews also revealed a clear negative judgment of farmers who “abandoned” the cooperative when prices surged.

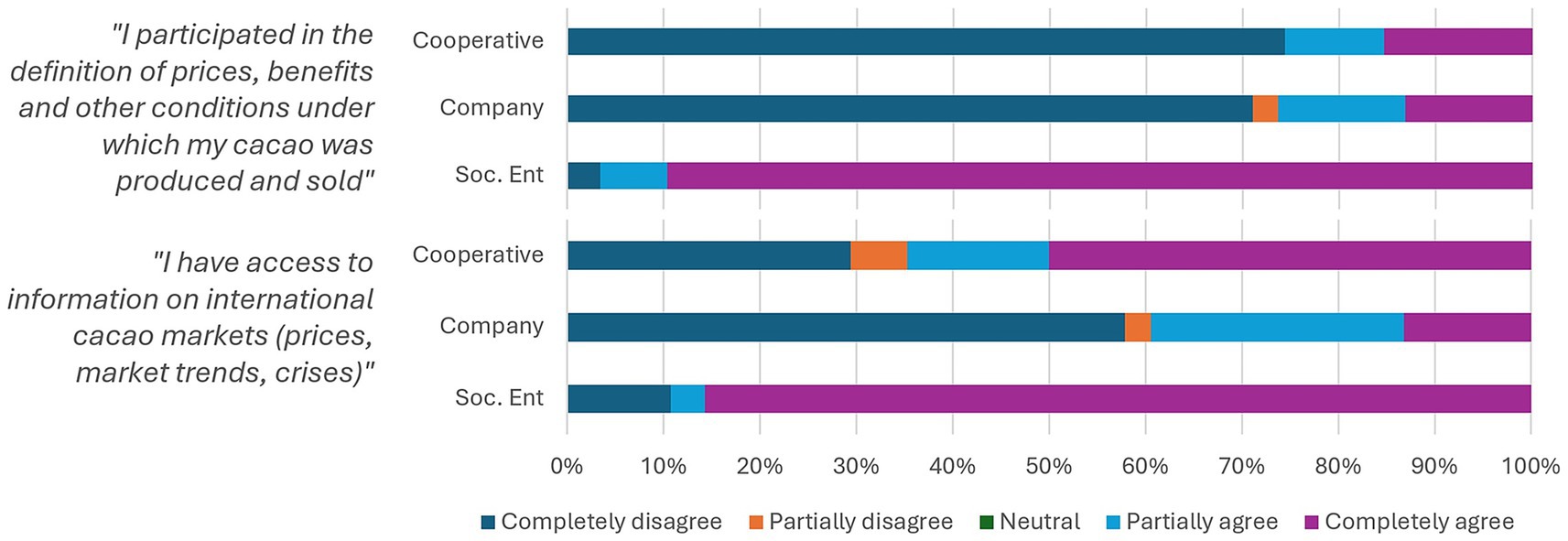

Despite the democratic governance also enshrined in the cooperative, no similar theme emerged from the interviews with cooperative members, most of which also reported in the household survey that they could not participate in the definition of prices, benefits and other conditions under which their cocoa was produced (see Figure 4). This may be plausible if interpreting the question literally, as at least prices are factually decided by management, whereas decision-making on services by the delegates’ assembly may not be felt by producers. Farmers from the cooperative, however, largely confirm a general lack of shared decision-making and resulting dissatisfaction in this regard, as several members point out that power lies almost entirely with the cooperative’s long-standing manager. This was strikingly confirmed by all but one member who denied feeling as an owner of the cooperative (see also below on mechanisms regarding recognition).

Figure 4. Agreement with statements on participatory decision-making and access to information among farmers associated with cooperative (n = 39/n = 34), company programme (n = 38/n = 38), and social enterprise (n = 29/n = 28).

Interestingly, farmers of the social enterprise who were formerly members of the cooperatives also primarily emphasized issues of procedural justice as a reason for this switch – a striking difference to company-affiliated farmers who invoked mostly distributive aspects, as mentioned above.

“I was member of [the cooperative] for ten years. The difference between [the cooperative] and [the social enterprise] … I would say I didn’t receive the consideration that we have in [the social enterprise]. They say that you are a member of [the cooperative], but you don’t have the power. If you are a member of [the cooperative] and you would like to take decisions, you can’t (male farmer of social enterprise, F3-1).

When the company-affiliated farmers were asked whether they miss possibilities to influence decisions, most farmers did feel that the company would nonetheless take into account farmers’ needs and perspectives which could be shared informally with staff during meetings. However, one company-affiliated farmer – a former member of the cooperative – argued that the procedural means of the cooperative were still important. Even though in the company they also have a suggestion box, he felt that in the cooperative it was different, “we had possibilities to complain” (F2-1). Similar to other farmers, he however signaled that this lack of participation was not in itself unjust, “because [it] is a private company,” and not a cooperative.

Regarding information- and transparency-related attributes of procedural justice, interviews with farmers shed light on the process through which the social enterprise provides information, as well as how transparency and information contributed to their wellbeing:

“Of course, members need to know perfectly about their company and about the cooperatives. There should be nothing to hide. In the past in [the cooperative], nobody knew who and to whom the cooperative would export, how much was sold and earned […] And in [the social enterprise] you know everything, sales, where the cocoa goes, how much chocolate was sold, how much was earned, how much as lost. Everything is integrated because at every assembly we receive information” (male farmer of social enterprise, F3-1).

Interviews across cases similarly highlighted the importance of being well-informed for a sense of control improving their future outlook. In contrast with the survey responses (see Figure 4), however, several company-affiliated farmers did generally feel that the company generally informs them sufficiently. However, a number of farmers in both the company and the cooperative criticized that the distribution of benefits, which they felt were attributed based on unjustified reasons and favoritism.

Linking several elements of procedural justice, an interesting theme emerged during the interview process with farmers from different cases: that cooperatives played an important role in the areas as a price regulator: without the presence of the cooperative, local intermediaries would drop their prices whenever they could. Indeed, one particularly critical member of the cooperative highlighted that this was the single most important feature of the organization. According to interviewees, this aspect would provide them with a certain sense of security, overall increasing their standard of living and future outlook. Although none of the interviewees explicitly connected this function to the procedural elements of cooperative governance, their emphasis that all other, private buyers would engage in such abusive behavior if they could, points to such a conjecture.

“[A private buyer] comes and imposes. Suddenly, in one month they pay you 20 Soles and in the next month less. So, there is no security. The cooperative in some way takes care of these aspects so that price is always just. […] If you want it or not, but [the cooperative] are the ones who determine the price here, otherwise intermediaries would be able to pay whatever they want” (female farmer of cooperative, F1-4).

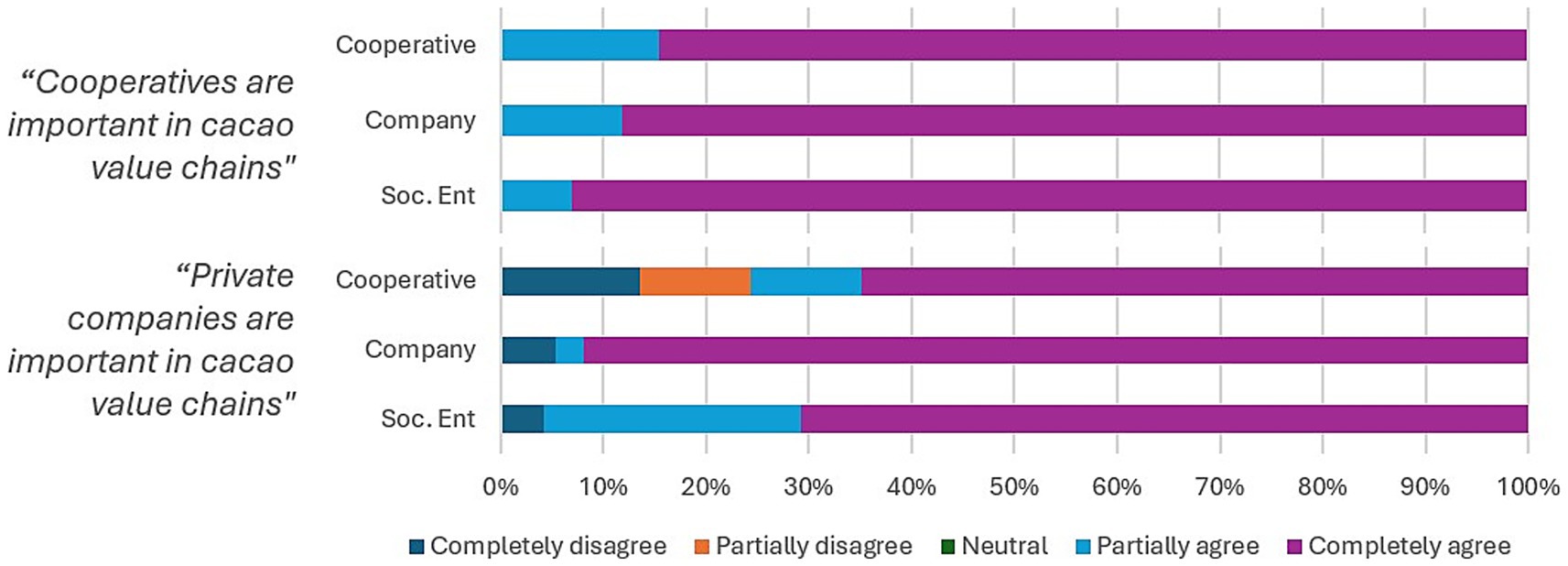

When confronting a manager of the company this claim, they emphatically rejected it, arguing that this may have been true in the past, but was the case anymore today since there are so many, also high-quality buyers, present in the region. Two survey questions shed some light on farmers’ beliefs on the role of cooperatives and private enterprises (Figure 5). Interestingly, almost all farmers across organizations completely agree with the statement “cooperatives are important,” whereas the picture is much more mixed for the same question on private enterprises, where only company-affiliated farmers are in strong agreement, with only roughly two-thirds of the cooperative and social enterprise members.

Figure 5. Agreement with statements on the importance of cooperatives and private enterprises among farmers associated with cooperative (n = 39/n = 34), company programme (n = 34/n = 37), and social enterprise (n = 29/n = 24).

Mechanisms associated with recognition justice

Asked about the role of recognition and respect, interviewed farmers of all three cases pointed to it being very important for their felt wellbeing in general, and their broader satisfaction with the case to whom they were affiliated. In fact, famers affiliated with the company and the social enterprise only responded positively about the recognition and respect they were shown from staff and the organization as a whole. One of them emphasized this with a theme that can be associated with satisfaction regarding life achievements in his role as a farmer:

“The treatment that they give to us as farmers is very important to me. They do not think better of themselves because they have studied or are engineers. Not at all, they are like us. This is very important for me” (male farmer of company programme, F2-15).

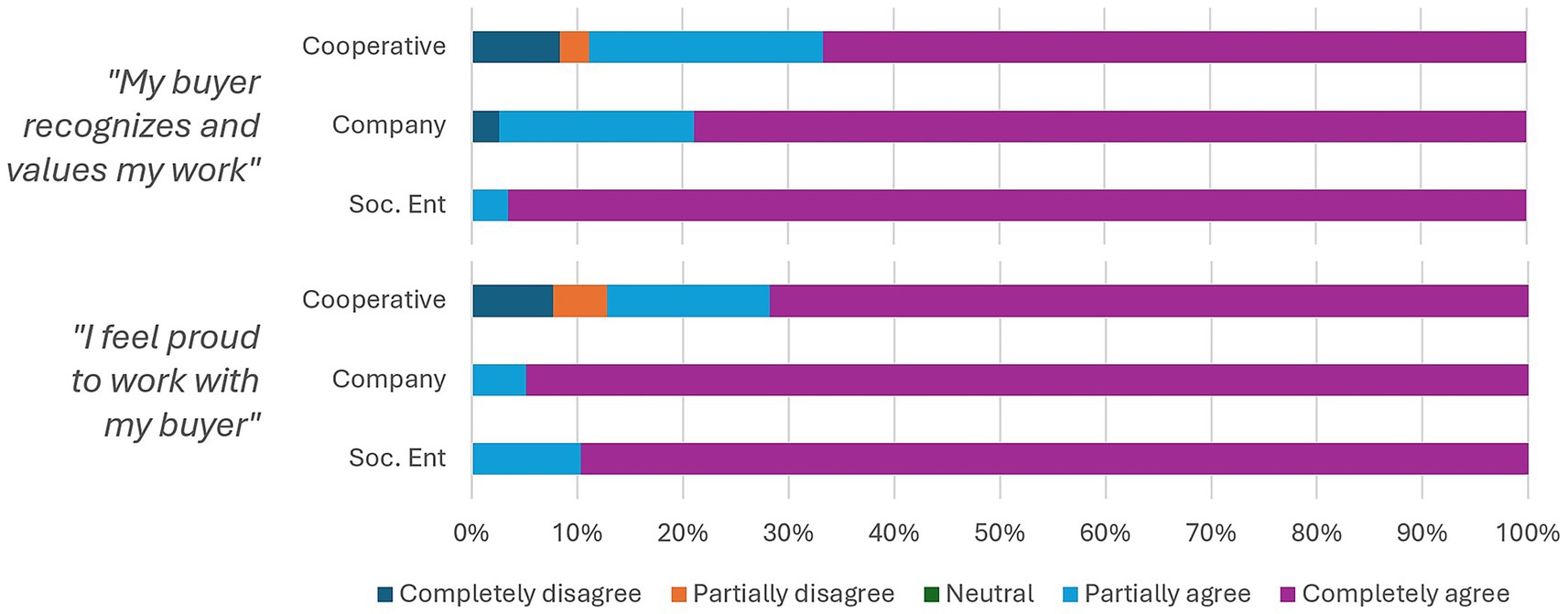

Recognition of the hard work producers do was also emphasized as an important factor of wellbeing. Particularly farmers in the social enterprise, with the attention they receive from staff, but also other aspects including the visibility and respect that is brought were themes that emerged throughout interviews. This tendency is also reflected in the survey responses, where all farmers in the social enterprise except one completely agreed with the statement that they felt their work was recognized by their buyer (see Figure 6). In a related question, whether they felt proud to be working with their buyer, social enterprise farmers still reported very strong agreement, but here the farmers affiliated to the company even more positive.

Figure 6. Agreement with statements on recognition among farmers associated with cooperative (n = 36/n = 39), company programme (n = 38/n = 39), and social enterprise (n = 29/n = 29).

The picture was more mixed for members of the cooperative. Interestingly, several farmers emphasized that some misrecognition derived from a feeling of not being heard and listened to as described under procedural mechanisms. One cooperative member also pointed to both procedural and distributive elements as key for demonstrating respect: the gifts members traditionally receive at the end of the year, which in many cases of Peruvian farmer cooperatives, include a panettone (a type of cake) and festive food hamper. Asked whether she felt as an owner of the cooperative, she – as almost all other members – denied, adding:

“Do I consider myself as an owner? No. They would have to listen to me much more. For instance, I complained about the panettones. They give you a cheap one of bad quality, how is that possible? We make organic cocoa, we make an effort. I want a panettone of decent quality. […] I told them they need to change this. They need to have more respect for the members” (female farmer of cooperative, F1-4).

For the social enterprise, which is also co-owned by farmers, differed dramatically from those of cooperative members, with all of them agreeing that they felt it strongly through the control and information they had over the enterprise, but also the recognition derived from it. Even more so, they emphasized how the visibility on the chocolate’s packaging and travels to Switzerland that the social enterprise had organized for them and which allowed them to learn about the chocolate production and meet consumers filled them with pride and recognized for their hard work but also made them truly feel as co-owners of the chocolate company.

Discussion

How does justice in cooperatives, company programmes and social enterprises influence farmers’ wellbeing? We embarked on answering this question to make sense of responses provided by farmers affiliated with a case of each strategy by means of comparative process tracing. Building on theory drawn from multiple disciplines, we developed multiple hypotheses on potential causal mechanisms linking attributes of distributive, procedural and recognition justice with eight subjective wellbeing dimensions. In the following paragraphs, we discuss each of these hypotheses in light of the explored qualitative and quantitative material and draw on additional theory to make sense of some surprising results.

Wellbeing effects associated with each justice dimension (H1-3)

Wellbeing effects associated with distributive justice attributes

Throughout cases and farmers, a fair price paid by buyers has emerged as the most recurrent important factor for farmer wellbeing and satisfaction. Many farmers indeed reported a significant and visible improvement in their wellbeing since the price hike in 2024, and for farmers affiliated with the social enterprise who received a higher-than-market price already before. Farmers report that prices are key for the wellbeing due to its fungibility: according to their specific needs, they can use their income for covering health costs, investing in the education of their children, or improving their farm, themes corresponding to wellbeing dimensions of standard of living, health, and future outlook, as hypothesized in H1. When prices do not cover even for production costs, as was recalled being the case by many farmers in the cooperative and the company before the price hike, prices were considered unjust. Similarly, the ups and downs of market price prevented planning and certainty for future investments.

The manifold purposes of monetary income also corresponds with research from other settings which demonstrate the centrality of economic factors in general, and fair prices in particular, for agricultural sustainability (Talukder et al., 2020; Valizadeh and Hayati, 2021, 2025). They also coincide with findings by Kröger and Schäfer (2014) on German organic farming networks who described the strong feeling of farmers that their value chain partners must take into account their needs and that economic conditions were largely considered unfair. At the same time, the fact that a significant share of the farmers and the social enterprise exited during the price hike points to prices being also an important driver of farmers’ commitment, as was confirmed by several interviews. Interestingly, farmers generally seem to acknowledge that price volatility lies beyond the control of their buyer and, in consequence, put their blame for low prices directly on them, as has been suggested in the literature (Colquitt et al., 2001; Hornibrook et al., 2009). At the same time, they expect their buyer to keep up with market prices during price hikes, even if they benefited from premiums in the past.

Further, when asked about services that were particularly appreciated, many farmers pointed to material benefits received, i.e., the subsidized or free provision of inputs and equipment. They were also invoked as the most important reason for exiting the cooperative and joining the company among farmers who had changed affiliation. Also, among remaining cooperative members and social-enterprise-affiliated farmers, material benefits were particularly highlighted which were not provided by the company, such as mutual support schemes for health (in both cases) and mechanisms for labor and equipment sharing (in the social enterprise). For these, farmers suggest a causal mechanism that particularly addresses health and future outlook-related wellbeing dimensions. Similarly, credits – particularly for non-farm investments – and projects for income diversification, were also only received by members in the cooperative and the social enterprise. The provision of such services only by the cooperative and social enterprise case may point to the relevance of a broader producer-oriented mission of these organization types, and the appreciation of enabling avenues for quality-of-life improvements beyond cocoa production (Gimenes et al., 2022). This may point to a particular feature of cooperative and social enterprises: whereas private companies are primarily concerned with increasing farmers commitment not only to their organization but to cocoa production, the social enterprise or cooperative character may be more directly guided toward a more holistic idea of wellbeing, and may also engage in activities that ultimately reduce dependency from cocoa production (Thorpe, 2018).

Wellbeing effects associated with procedural justice attributes

In terms of wellbeing effects of procedural justice, several themes regarding procedural justice emerged during interviews which largely confirm H2. One theme that only emerged during the interviews highlights the importance of having a buyer from the region, or that is firmly established in the region. This long-term presence was described as providing a sort of insurance that one will be able to sell the harvest at good conditions, supporting the hypothesis of wellbeing effects particularly in terms future outlook and in line with arguments about the benefits of long-term commitment (Stevenson and Pirog, 2008; Thorpe, 2018). Moreover, farmers associated with the cooperative emphasized the importance of the cooperative on their personal safety, given the role they attributed to it in the region’s shift from a coca-producing region to a cocoa hub, supporting findings from research on the potential of cooperatives in supporting long-lasting peace in conflict- and drug-trafficking-affected areas (Coscione, 2019). This would also explain the relatively high contribution to their personal safety members attributed to the cooperative in the household survey.

In a somewhat related vein, farmers referred repeatedly to an important (or even the most important) benefit of the cooperative and its governance structure: that it would operate as price regulator in the region. Whereas private buyers would offer prices as low as they can, the cooperative would have to answer to its members if it did and cannot afford to lose members. Importantly, procedural justice institutionalized in some larger buyers may as a result benefit also non-affiliated farmers in the region. This may be corroborated by farmers across cases responding positively about the importance of cooperatives for farmers, whereas the importance of private buyers more strongly differentiated between the company and the other cases. This finding speaks to a long-standing theoretical argument about the potential of farmer cooperatives to mitigate market failures in rural areas (Rhodes, 1985). For more direct wellbeing effects of procedural justice, social enterprise-affiliated farmers emphasized how participative decision-making and strong transparency would create important possibilities to raise concerns and put forward suggestions. This confirms observations from earlier studies on the key role of procedural justice in agricultural supply chains also observed in other geographical contexts (Fearne et al., 2004; Thorpe, 2018). Importantly, many farmers linked the feeling of being listened to with a sense of feeling recognized by and identified with the buyer, as we discuss in the next section.

Wellbeing effects associated with recognition justice attributes

In the household survey, farmers in the company programme and the social enterprise strongly agreed when asked whether they felt that their buyer recognized and valued their work, and similarly whether they felt proud to be working with it. These affirmations were less pronounced in the cooperative, which also performed lowest in terms of wellbeing. In the interviews, farmers described what made them feel this way, and why this was important to them. Practices that seemed to foster such a sense of recognition and being respected included “small things,” such as the panettone received at the end of year or the attention they received from staff during visits and meetings. However, some interviewees were also adamant about emphasizing that what matters is the quality of such practices: a cheap panettone may just as much convey disrespect, as one farmer pointed out, while feeling treated as equals and in a not-condescending way by qualified staff was emphasized. Such examples support the perspective established in the organizational justice literature (though only rarely demonstrated for value chains) that respectful treatment – or “inter-personal justice” is a key factor for satisfaction (Colquitt et al., 2001, 2013; Yilmaz et al., 2004).

Farmers affiliated with the social enterprise, who on average felt most strongly recognized by their buyer, further highlighted travels to Switzerland, the treatment received during their stay, as well as the visibility the enterprise granted them by putting their names on the chocolates, as important sources of recognition and pride, and wellbeing related to their life achievements. Statements by some farmers who benefited from these offers also emphasized a broader, group-related element of respect that applied not only to them personally, but the work of cocoa farmers in general, as suggested in the environmental and food justice literature (Tribaldos et al., 2020). Moreover, members of the cooperative and the social enterprise spontaneously mentioned the importance of the social activities and sense of community integration that was fostered by their organizations. This was also notable in survey responses on buyers’ contributions to different wellbeing dimensions, where the cooperative and the social enterprise significantly outperform the company in terms of contributions to personal relationships and community integration. These elements largely confirm H3; although no significant contribution on religious or spiritual aspects could be identified.

“All the work we do is for the price” – a case of distributive dominance? (H4)

This emphasis of many farmers on the price and primarily material benefits derived from the case as most important for their wellbeing may support H4 and the “distributive dominance” paradigm (Colquitt et al., 2001), in contrast with theory and evidence suggesting that procedural justice may instead be more powerful to explain outcomes than distributive justice (Kumar et al., 1995; Thorpe, 2018). The most straightforward explanation for why price and material benefits were considered most important by farmers across cases lies in farmers’ often dire socioeconomic situation and lacking livelihood security, as introduced earlier. In this line of reason, distributive concerns are at the forefront of farmers’ concerns simply because among small-scale farmers, basic needs are generally not sufficiently or safely covered yet, so that elements directly increasing their income or lowering their costs are too important for survival than other considerations (Brown et al., 2006).

Beyond the general affirmation on the importance of material benefits, there are, however, also other observations that may suggest a case of “distributive dominance” (Leventhal, 1980). First, the importance of procedural justice is significantly challenged by the fact that company-affiliated farmers exhibit very high wellbeing and report a high satisfaction with their buyer while benefitting from the lowest institutionalization of procedural justice attributes. There are several potential explanations for this. One may have to do with self-selection, i.e., that those farmers who left the cooperative for the company may put higher priority on distributive rather than the procedural aspects granted by the democratic setting in the cooperative (which was indeed highlighted as lacking by only one former member in the company). This self-selection argument would be supported by the observation that ex-cooperative members now affiliated with the social enterprise predominantly referred to feelings of being treated in an unjust way in terms of procedures as a reason to leave.

Other explanations for this potential “distributive dominance” focus more on the substitutability and temporal dimension moderating the relevance of procedural justice. Importantly, company-affiliated farmers reported no procedural concerns, and instead affirmed that in general they felt that the company’s staff listens to them, despite a lack of instruments to hold staff or the company accountable to their complaints. This may point to a possibility that with strong informal means for sharing concerns, companies can – at least to a certain extent – compensate the need for justice in formal procedures. Perhaps more likely, however, it may be related to an explanation on the temporal dimension of the effects of justice in the literature which suggests that in the early stages of a supply chain relationship, distributive concerns dominate, whereas with time, the importance of procedural justice increases (Kumar et al., 1995). This argument would be supported by findings on the company programme, to which most farmers had been affiliated only for a few years whereas on average, members of the cooperative had been part of it for significantly longer.

Two further explanations concern the quality and potential reach of procedural justice in the cooperative, and supply chains more generally. Strikingly, survey responses showed that cooperative members felt even slightly less included in decision-making than company-affiliated farmers. This finding was corroborated by interview responses on the lacking effectiveness of their democratic procedures given the powerful role of the cooperative’s manager point to the limitations of formal procedures, a finding widely supported by research on cooperative governance (Bernard and Spielman, 2009). Finally, a more structural explanation that might reduce procedural justice concerns may be due to the fact that a key determinant – the price – is typically beyond the reach of their buyers’ control, particularly if the latter predominantly operates in B-to-B markets which are typically referenced to global market prices. This is the case for almost all firms and cooperatives buying directly from farmers, including the cooperative and the company under study. The social enterprise, in contrast, which uses the farmers’ produce for chocolate directly marketed to consumers (which was also an important factor enhancing farmers’ recognition), does not primarily depend on global cocoa market prices for their economic survival. In fact, it is primarily this precondition that not only enabled them to pay fixed above-market prices, but also to have these determined by farmers themselves. Interestingly, it is also the social-enterprise-case that provides some arguments against H4: when the fixed price was suddenly outcompeted by the market price, remaining farmers initially stuck with their pricing model based on their understanding of it being just, even though “distributively” speaking, they were worse off than farmers around them.

Different justice expectations for different actors and strategies

Interviews with farmers and managers of all cases revealed a theme that emerged repeatedly, so that it could not be excluded from a discussion of the role of justice in supply chain strategies: the role of differentiated expectations and justice judgements – or the observation that farmers hold higher or lower expectations in terms of justice institutionalization based on the type of organization. In other words: might the lowest satisfaction with the cooperative reported by farmers in the survey not so much emerge from an objective standard to which they would hold accountable any buyer, but because of the highest disappointment, or perceived gap between how the cooperative should function, or functioned in the past, and how it actually does today? In explaining their views of the cooperative, several members repeatedly alluded to such perceived gaps, while several company-affiliated farmers tellingly emphasized that they would have no expectation whatsoever about participating in the company’s decision-making, because it is private. Interviews with managers of both cases confirmed such an impression that farmers generally hold the cooperative to higher expectations than private buyers.

The role of expectations in shaping “justice judgements,” i.e., whether and why some behavior is considered just, whereas another is not (Leventhal, 1980), and how such judgements in shaping outcomes corresponds with a theoretical paradigm that gained significant traction in the organizational justice literature in recent decades: social exchange theory (Colquitt et al., 2013; Blau, 2017). Social exchange theory suggests that rather than “objective” evaluations of practices, people’s perceptions of “just” treatment are importantly shaped by a subjective sense of reciprocity, but also expectations based on experiences, the promises made by their counterparts, as well as comparisons to others (Blau, 2017). Regarding reciprocity, it was striking how farmers expressed their relationship with their buyer differently between cases. Many farmers across cases discussed their relationship with their buyer as indeed one of reciprocity, expressing that their commitment was also shaped by a sense of loyalty to their buyer. However, closer analysis of the way farmers in the cooperative and the social enterprise discussed these themes revealed slight differences in their way of justifying this sense of loyalty. Whereas company-affiliated farmers mostly discussed their sense of commitment by means of expressing gratitude for benefits received in the past (“they give you training, so what you do in return is selling only to them,” int. F2-12), cooperative members variously invoked reasoning beyond their individual exchange they experienced with their organization, such as ideals of cooperativism, but also belonging. This was most impactfully expressed by one (notably rather disenchanted) member:

“Commitment to the cooperative requires giving life to it. Because if we are unloyal, it doesn’t work. In some ways it is like with your spouse, you are committed, and even if a more beautiful women comes around, you stay with your wife. It’s for commitment, not because it’s always better, but for commitment. You need to give life to the cooperative” (male farmer of cooperative, F1-2).

Both farmers of the cooperative rejecting a sense of ownership, as well as social-enterprise-affiliated ones who unanimously affirmed such a feeling, farmers in these more bottom-up structures justified their commitment also through a sense of responsibility for making the organization work and standing by even in more difficult times. As a result of such a more “socialized” understanding of their relationships, members may also have higher expectations toward the cooperative than company-affiliated ones did toward their buyer. These findings point to a theoretically suggested (Gimenes et al., 2022) but so-far understudied finding that commitment, satisfaction and – to some extent – wellbeing perceptions in cooperatives may be driven by a much more “socialized” relationship compared to private buyers, in line with Blau’s fundamental work on expectations in social exchange (Blau, 2017), and Leventhal (1980)’s emphasis on selective and context-based “justice judgements.”

Conclusion

Improving the wellbeing of farmers in the cocoa sector remains a key focus of sustainability efforts, both as a goal in itself, and as farmers are considered key agents for wider sustainability transformations (Mills et al., 2021; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). In light of often-limited effects of sustainability governance strategies, the presented paper drew on theoretical and empirical insights from organizational psychology and management studies to study how the institutionalization and perceptions of justice in cooperatives, company programmes, and social entrepreneurship strategies may moderate the effect of such strategies on farmer wellbeing in the Peruvian Amazon.

Results from the process tracing illuminate findings from a parallel investigation based on quantitative methods (Montoya-Zumaeta et al., in press) which showed that, compared to conventional value chains, each of these strategies provide for important improvements on wellbeing. In this light, the presented study presents three key findings: First, it demonstrates that key causal mechanisms relate to the extent to which strategies institutionalize attributes of distributive, procedural, and recognition justice. Second, the study finds that while all justice dimensions importantly moderate sustainability strategies effects on wellbeing, distributive attributes are perceived as most impactful by farmers, somewhat challenging earlier findings highlighting the importance of procedural justice (Thorpe, 2018). Farmers across cases explained this “distributive dominance” with their continued struggle to cover basic needs which, up to a certain extent, trumps other concerns. Third and finally, an emergent theme in our findings suggests that justice judgements may significantly differ between organizations, with cooperatives being held against higher “justice standards” than private firms. This corresponds with a more recent generation of studies on organizational justice based on social exchange theory (Blau, 2017) and theoretical propositions suggesting that justice perceptions importantly differ between cooperatives and other types of firms (Gimenes et al., 2022).

Overall, however, the causal mechanisms identified for all three cases and justice dimensions suggest that institutionalizing justice in all value chains – not only more niche or alternative ones – may be key to truly improve farmer wellbeing and create long-term commitment to sustainability strategies. As a result, orienting sustainability governance toward justice may also more broadly enhance agri-food value chains’ contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals. Most practically, and particularly in light of regulatory trends where farm-level traceability and, thus, long-term relations with farmers, are in high demand, firms and cooperatives may be well-advised to take into account factors that increase the satisfaction of their counterparts, including by institutionalizing justice.

Despite these promising findings, the study also suffers from some limitations which could be addressed in future research. First, future studies could aim at drawing an even clearer distinction between the importance of different benefits obtained from the farmer, and the perceived justice of these benefits, such as by drawing more directly on survey items validated in the organizational justice literature (Kumar et al., 1995; Colquitt, 2001). Second, study designs could from the outset incorporate potentially differentiating justice expectations based on regional differences or the types of buyers (as has been observed in this study, though as an unexpected finding). Overall, however, the results suggest that sustainability governance research may importantly benefit from incorporating farmers’ justice perceptions more systematically to understand the impacts of value chain strategies on farmers wellbeing.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the focus of questions, the emphasis on voluntary participation, and prior, careful information using Informed Consent Forms applied to each individual and organization ensured that ethical risks were sufficiently addressed. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JM-Z: Writing – review & editing. JJ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (COMPASS project, Grant agreement No. 949852).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In the organizational and supply chain literature, the term inter-personal justice is more commonly used for this ‘third dimension’, due to the discipline’s predominant focus on the respect among individuals in the often-personal treatment in interactions, e.g., with value chain partners (Colquitt et al., 2001). For the purpose of this article, we use the term recognition justice to also account for perceptions of and practices geared not only at individual respect towards farmers, but also group-level recognition.

2. ^See https://www.cde.unibe.ch/research/projects/environmental_justice_for_human_well_being_compass/index_eng.html. The project was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 949852).

References

Allen, P. (2008). Mining for justice in the food system: perceptions, practices, and possibilities. Agric. Hum. Values 25, 157–161. doi: 10.1007/s10460-008-9120-6

Bager, S. L., and Lambin, E. F. (2020). Sustainability strategies by companies in the global coffee sector. Bus. Strat. Environ. 29, 3555–3570. doi: 10.1002/bse.2596

Beach, D. (2017) “Process-tracing methods in social science,” In D. Beach, Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.176

Beach, D., and Pedersen, R. B. (2013). Process-tracing methods: Foundations and guidelines. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Bennett, E. A. (2017). Who governs socially-oriented voluntary sustainability standards? Not the producers of certified products. World Dev. 91, 53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.010

Bennett, A., and George, A. L. (1997). “Process tracing in case study research” in MacArthur Foundation workshop on case study methods, Cambridge, Massachussets: MacArthur Program on Case Studies. 21. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139858472

Bennett, E. A., and Grabs, J. (2024). How can sustainable business models distribute value more equitably in global value chains? Introducing ‘value chain profit sharing’ as an emerging alternative to fair trade, direct trade, or solidarity trade. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 34, 581–601. doi: 10.1111/beer.12666

Bernard, T., Collion, M.-H., de Janvry, A., Rondot, P., and Sadoulet, E. (2008). Do village organizations make a difference in African rural development? A study for Senegal and Burkina Faso. World Dev. 36, 2188–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.10.010

Bernard, T., and Spielman, D. J. (2009). Reaching the rural poor through rural producer organizations? A study of agricultural marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia. Food Policy 34, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.08.001

Birthwright, A.-T. (2023). Negotiating politics and power: perspectives on environmental justice from Jamaica’s specialty coffee industry. Geogr. J. 189, 653–665. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12465

Blackman, A., and Rivera, J. (2011). Producer-level benefits of sustainability certification. Conserv. Biol. 25, 1176–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01774.x