- 1College of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China

- 2Beijing-Dublin International College at BJUT, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China

- 3College of Engineering, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

China’s prepared dishes industry has experienced rapid development and is undergoing a transformative shift from industrialized production to public recognition and acceptance. This study examines the discursive dynamics surrounding the development and promotion of prepared dishes and food in China, exploring the interaction between policy makers and consumers. Through a discourse analysis of 21 government policy documents published by official government websites, over 1000 comments from social medias, and 55 depth consumer interviews face to face and via phone call, this paper identifies three key discourses, cultural, distrust, and industrialization, that consumers have developed regarding prepared dishes and food. This study finds that: Initially, the government’s top-down promotion of prepared dishes encountered heated public opinion due to unclear definition of the terminology and lack of consumer education, as well as widespread consumer concerns over food safety, quality, and transparency. The cultural discourse centered on traditional food values and the perceived artificiality of processed foods, while the distrust discourse linked prepared dishes to past food safety scandals, eroding public trust. As consumer opposition grew, government discourse adapted, incorporating more stringent regulations, official definition and clarification of terminology and consumer-friendly measures, such as a ban on preservatives, distinguishing the terminology between “prepared dishes and food” and “central kitchen”, in response to consumer demands. By examining these shifting discourses and their impact on policy changes, the study provides insights into the role of discourse in the governance of new food initiatives and institutionalization of food industry regulation, and highlights the need for responsive, inclusive policymaking that integrates consumer perspectives to foster trust and legitimacy in emerging food industries.

1 Introduction

Currently, the diet, consumption pattern and lifestyle of consumers have undergone great changes with rapid industrialization, urbanization and fast-pace daily life. New food initiatives have emerged as innovative responses to these shifts by integrating advanced technologies with evolving consumer demands and regulatory practices—among which prepared dishes have garnered particular attention. These initiatives are not only essential for adapting to modern lifestyles but also play a significant role in broader national objectives such as modernization of food sector, rural revitalization, sustainable development (Fröhlich, 2024) and high-quality economic development. The governance of new food initiatives involves a dynamic process in which novel concepts and terminologies are introduced, conflicts and contradictions from different stakeholders arise, and through continuous consumer communication and education and institutional refinement to establish a stable regulatory framework.

A prominent illustration of these transformative food initiatives is the rapid growth of prepared dishes and food, which has been a vital component of the global food market, particularly in China. In China, the rise of prepared dishes is not only a matter of market growth but also a site of tension between narratives of modernization, efficiency, and industrial upgrading on the one hand, and consumer concerns about health, authenticity, and modern food practices on the other. Prepared dishes firstly emerged in Japan and the United States in the 1940s and 1950s and have experienced rapid development since then. In China, the industry has gained significant momentum due to urbanization and the expansion of the fast-food sector. The saturated traditional catering market and the shrinking of the catering industry due to COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) have further accelerated development of the prepared dishes industry in China. Additionally, central kitchen for industrial-scale production underscores how urbanization, socioeconomic shifts, evolving family structures, and pandemic impacts are collectively reshaping the food landscape in China (Hasani et al., 2022).

As the market for prepared dishes evolves, so too does the discourse surround them. The emergence of this sector has stimulated varying public responses and controversial discussion in China, from enthusiastic adoption by some young generations in urban areas to skepticism and resistance in more traditional consumer segment. Notably, in September 2023, a news about “Wuxi School Prepared Vegetables on Campus” ignited drastic public opinion. On China’s mainstream social media, Weibo, the topic received more than 2 million views and numerous comments. Prepared dishes have received mixed reactions from the public, with both support and criticism. Furthermore, consumers’ concerns over food safety, the use of artificial additives, and the perceived departure from traditional culinary practices (Chen et al., 2023; Sahin and Gul, 2023) also lead to concerns and public debates on prepared dishes and food in China. However, how policy and consumers’ discourses surrounding prepared dishes are discursively constructed and contested and the broader debates on governance, consumer trust, and the institutionalization of food practices in the Chinese context has not yet been sufficiently studied.

This study aims at contributing new insights on the dynamic evolution of consumers’ discourses and actions on prepared dishes and examining the formation and evolution of the prepared dishes discourse as a representative case of new food initiatives in China. Firstly, the study investigates how conflicts and contradictions in the early stages of the new food initiative were addressed and resolved through a process of policy and regulatory adjustment and institutional improvement. Then, by analyzing consumer narratives from initial controversies to the eventual consensus with the policies and practices, this research seeks to illuminate the mechanisms by which new food initiatives are integrated into national food governance framework with consumer perspective taken into consideration. This study addresses the following questions:

How do government documents and consumers represent and construct prepared dishes? What discourses emerge from these discursive representations?

How do consumers’ representations of prepared dishes contest or align with government discourses? What are the dynamic relations between consumer discourses and government discourses?

How do government discourses of prepared dishes address consumers’ skepticism toward prepared dishes?

Through addressing these questions, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of the interplay between policy, consumer, and industrial development in the context of governance for new food initiatives.

2 Literature review

2.1 Consumer preferences

The prepared dishes and food industry has garnered increasing attention as a growing sector within the food industry while consumers’ perception and attitudes toward them has triggered heated debate (Xiong et al., 2023; Yi and Hengyi Xu, 2023; Jia Y. et al., 2024), yet literature on this topic remains relatively limited. However, there exists substantial research on consumer behavior and preferences for processed and ready-to-eat foods to paint a detailed picture. Researchers have emphasized the importance of understanding the psychological and cultural factors that influence consumer decisions in food markets and convenience (Sahin and Gul, 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Personal characteristics, taste, food safety and trust are main factors that drives consumer preference.

Many scholars have studied the consumer preferences based on consumers’ personal characteristics. Geeroms et al. (2008) found that consumers’ own characteristics influence the purchase of prepared dishes, and that energetic experimenters and conscious experts showed more positive attitudes, stronger beliefs, and higher penetration and consumption frequency than harmonious hedonists, norm-setters, and rationalists. Jia S. et al. (2024) found that social factors such as the herd effect would increase the consumption of premade food. Judy Graham found that consumers are increasingly choosing pre-made meals to save time, and pre-made meals have gradually become a modern trend (Graham et al., 2022). Studies indicates that parents play a key role in the consumption of prepackaged processed foods. It is found that since lower cooking self-efficacy and meal planning abilities are associated with the majority of reported reasons for purchasing prepackaged processed foods, strategies to increase these attributes for parents of all backgrounds can reduce dependence on prepackaged processed foods at family meals (Horning et al., 2017). It is also found that income induced parental indifference to dietary health is an important factor leading to an increase in prepackaged meal consumption (Lovelace and Rabiee-Khan, 2015).

Taste is studied to be one of the key elements for consumer’s preference toward prepared food. It is revealed that the tenderness and juiciness of beef, overall taste, overall preference and purchase intention would all influence consumers’ consumption of pre-packaged beef foods (Sorenson et al., 2011). Studies also found that young people have a higher tolerance for low quality, and the type of food is related to complaints and perception of food quality; the taste and smell of food are the main reasons that influence the purchase of prepared goods (Djekic et al., 2022).

Food safety and trust toward prepared food also one of the concerns for consumes (Liu et al., 2023; Lam et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2025). It is found that consumers are highly concerned about the authenticity of meat in ready-to-eat foods and have a strong desire to know where the ingredients come from, providing practical guidance on reducing consumers’ perception of food risk (Agnoli et al., 2016).

2.2 Consumer discourse and food discourses in China

Public discourse of prepared foods in China reflects deep-rooted concerns about health, transparency, and authenticity. Research using large-scale social media reveals overwhelmingly negative sentiment toward prepared dishes in China, with debates dominated by production processes, raw materials, and additives. Shu et al., (2024) analyzed hundreds of thousands of social-media comments and reported that a majority carried negative sentiment, with top topics relating to production processes, raw materials, packaging, and additives. A notable demand for informed consumption rights has emerged, particularly regarding the introduction of prepared dishes in school canteens, highlighting tensions between convenience and trust (Shu et al., 2024). Survey-based studies complement social media analyses by unpacking psychological mechanisms behind discourse. Zhang et al. (2024) apply the Expectation-Confirmation Model to Chinese consumers of prepared dishes and identify perceived risk (health, quality, social, psychological, purchase) and trust (ability, integrity, benevolence, government trust) as central determinants of consumption intention. Trust mitigates perceived risk, though unevenly across risk dimensions, while perceived quality risk strongly suppresses continuance (Zhang et al., 2024). Research on food safety liability in Qingdao, China suggests that consumers see strict punishments for illegal practices, stronger legislation, and enhanced law enforcement as more effective solutions to food safety risks than liability insurance, though insured food still enjoys greater consumer preference (Liu and Liu, 2015).

2.3 The governance and institutionalization processes of food system

Policy responses to consumer discourses emphasize behaviorally informed, context-sensitive interventions. Reisch (2021) argues that behavioral food policy should be people-centric and context-sensitive, highlighting the importance of interventions that reshape consumption routines and decision contexts. The study highlights the centrality of the human factor in behavior-oriented policymaking: without consumer and citizen acceptance, participation, and engagement, even the most advanced technologies or innovative products and processes are unlikely to achieve success (Reisch, 2021).

Discursive institutionalism foregrounds how ideas and communicative processes shape institutions. Institutionalization is conceptualized as a spiral in which discourses are generated, embedded in policy documents and practices, then re-opened for repositioning in the urban food policy (Sibbing and Candel, 2021). For example, short food supply chains (SFSCs) in China leverage transparency and proximity to rebuild trust, addressing information asymmetry as a primary source of distrust in industrialized food. It is found that contextual factors, information availability, and trust are key determinants of consumers’ willingness to engage with local channels (Herzig and Zander, 2025).

The existing research provides valuable insights into the evolution of this emerging industry, revealing that consumers generally prioritize attributes such as traceability, taste, and food safety. However, Current studies primarily focus on consumer preferences, they rarely delve into the underlying representation and discourses behind these preferences. Existing research on the food policy governance mostly directs its attention to the background and main objectives of policy document issuance, while research on the discursive arguments in policy texts and their legitimization effects remains relatively rare. Research on the public discourse of prepared dishes mainly relies on one-dimensional perspective and descriptions from social media and lacks in-depth analysis of the linguistic means and strategies in consumer and policy discourses, and also fails to comprehensively consider the interactive relationships and dynamic evolution between consumer and policy discourses. To address these gaps, this study aims to examine how consumer discourses and actions shape the governance of prepared dishes, and investigate the institutionalization process within this sector.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Data and material

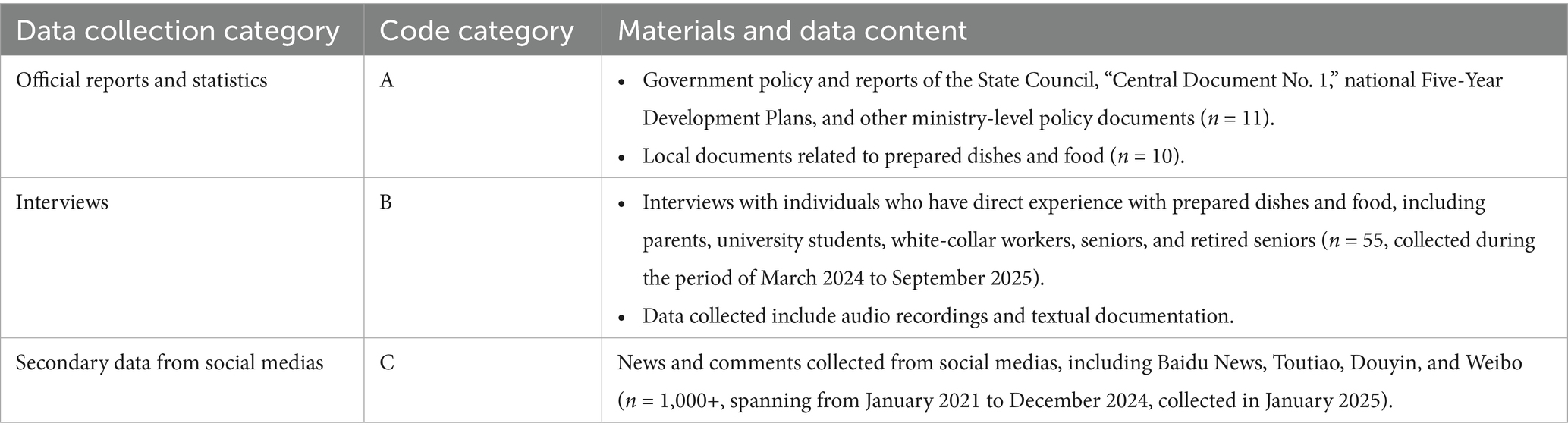

This study conducts a policy and consumer-based discourse analysis of China’s prepared dishes and food by examining both institutional policy frameworks and consumer perspectives. All the data and material are listed in Table 1.

To establish the policy context, we prioritized official documents published between 2021 and 2024, a period marked by significant regulatory developments of prepared dishes and food in China. Through targeted searches on government portals, including the websites of the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and provincial and municipal government websites. We identified and analyzed 11 national-level policies and 10 provincial and municipal-level policies (from Shanghai and Guangzhou) in details as shown in Table 1.

Consumer discourse was captured via mixed methods: First, primary data comprised 55 depth semi-structured and face-to-face interviews with urban residents in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Zhengzhou, Shenyang and other tier 1 and tier 2 cities of China (Interviewed in March 2024 to September 2025), focusing on perceptions of consumption, concerns, trust and cultural acceptance of prepared dishes and food. This study concentrates on consumers in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities, given that these urban centers constitute the core market for prepared dishes in China, where higher disposable incomes and accelerated lifestyles have fueled greater demand for convenience-oriented food products.1 All the interviews are conducted anonymously. Interviewees were selected by age, income, and frequency of prepared food consumption based on theoretical sampling (Flick, 2018) to ensure demographic diversity. We selected different consumer groups including university students, parents, white-collar workers, seniors, and retired seniors. Second, secondary data was sourced from 1000 + social media posts (Weibo, Douyin, Toutiao) spanning January 2021–December 2024, collected using keyword algorithms targeting terms like “预制菜” (prepared dishes and food) and “中央厨房” (central kitchen). This dual approach allowed triangulation of qualitative insights (e.g., interviewees’ perceptive and attitudes) with quantitative trends (e.g., a high surge in social media mentions during event and policy debates). All data was anonymized, and validated using triangulation methods.

Texts of interview notes and recordings, social media posts and policy documents were analyzed for evidence of ideas, involved actors and accounts of discursive interactions, balancing policy intent with lived consumer experiences to reveal gaps and interactions between institutional narratives and public reception. We reconstructed discourses, coalitions and the different phases of the discursive-institutional spiral, through a sequence analytic, iterative comparison of the insights obtained through the three data sources.

3.2 Methodological approach: a discourse analysis and discourse institutionalism

Following the linguistic turn in public policy research, language is no longer viewed as a neutral medium mirroring the reality, but as an active force which profoundly shapes our view of reality. Discourse analysis provides a theoretical perspective that explains how discourse is involved in shaping decision-making process, practice and policy. This study adopts a discourse-analytic approach that combines insights from Hajer’s discourse coalition and institutionalization framework, and Schmidt’s discursive institutionalism to trace how ideas, representations and practices are articulated, contested, and embedded within governance of prepared dishes and food in China and to narrate and explain the government’s policy shift on the topic of prepared dishes and food by digging deeper into the discourses of consumers.

Foucault provides the methodological starting point: discourses are historically contingent systems of statements and practices that delimit what can be said, thought and acted upon in a given field (i.e., discursive formations), and they produce observable effects in institutions and everyday practices (Foucault, 1976). Hajer (1993) defined discourse as “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities”. Discourse encompasses not only the substantive content of ideas but also the interactive processes by which ideas are conveyed. Discourse is not just ideas or “text” (what is said) but also context (where, when, how, and why it was said). The term refers not only to structure (what is said, or where and how) but also to agency (who said what to whom) (Schmidt, 2008).

According to Hayer, “A discourse coalition is basically a group of actors who share a social construct,” plural discourses build up specific story line, and the actors who receive the story line form a discourse coalition. Discourse structuration occurs when a particular discourse begins to shape how a society conceptualizes the world. A discourse coalition emerges when a group that includes a collection of storylines, the individuals who express these storylines, and the practices that align with them, all centered around a particular discourse. The discourse coalition framework proposes that politics is a process where diverse actors from different backgrounds come together to form coalitions around particular storylines. These storylines serve as the means through which actors attempt to impose their perception of reality on others, promote certain positions and practices, and challenge alternative social arrangements.

Schmidt’s (2008, 2010) discursive institutionalism complements this approach by distinguishing between coordinative discourse (internal dialogs among policymakers, experts, and industry actors) and communicative discourse (public debates between political actors and citizens). This distinction enables us to trace how narratives about prepared dishes circulate between policy and public opinions and how they influence institutional change.

When a large number of people adopt this discourse as their framework for conceptualizing the world, it becomes embedded within institutions to manifest either as organizational practices or as traditional ways of reasoning. This process is defined as discourse institutionalization (Hajer, 1993). Discourse institutionalization facilitates the reproduction of a given discourse. Actors who have been socialized to work within the frame of an institutionalized discourse will leverage their positions to influence or compel others to interpret and approach reality according to their institutionalized insights and convictions (Schmidt, 2010).

This study applies a three-step analytical strategy to investigate consumer and policy discourses about prepared dishes in China. First, data were collected from three complementary sources: (a) policy documents to capture coordinative discourse among policymakers; (b) social media datasets to analyze communicative discourse in the public sphere; and (c) semi-structured interviews with consumers to provide contextual depth. Second, the material was coded at multiple levels. Consumer’s ideas and practices were grouped into broader storylines (e.g., industrial modernization, culture and distrust). The findings reveal three dominant consumer discourses, namely, culture discourse, distrust discourse, and industrialization discourse, which compete to define and interpret the meaning of prepared dishes within specific social and policy contexts. Actors mobilizing overlapping storylines were subsequently mapped into discourse coalitions. Third, institutionalization analysis was conducted to assess whether and how particular discourses became embedded in organizational practices, legislation, or policy strategies. Drawing on this framework, the study reconstructs how discourses and interactive processes around prepared dishes have dynamically shaped aims, scope, and strategies in China’s food sector.

3.3 Coding, categorization and discursive analysis

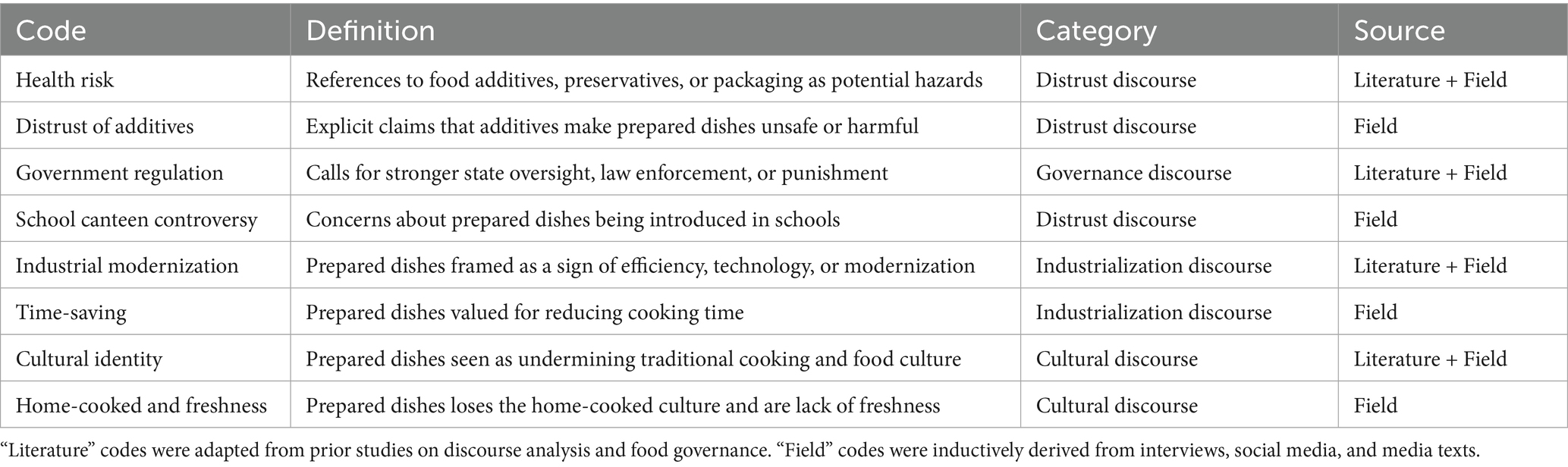

The discourse analysis followed an iterative process of developing codes, categories, and themes, combining both deductive and inductive approaches. As shown in Table 2, In the first stage, we generated an initial list of codes from the literature on discourse analysis, food governance, and consumer perceptions. These literature-derived codes provided a theoretical anchor for the analysis, such as health risk, industrial modernization, and cultural identity. In the second stage, we engaged in open coding of empirical material (policy documents, media articles, social media posts, and interviews) to identify field-derived codes that emerged directly from the data, such as distrust of additives, school canteen controversy, freshness, and time-saving. In the third stage, related codes were grouped into broader categories (i.e., distrust discourse, industrialization discourse, and cultural discourse) that represent discourses shaping consumers’ perception of prepared dishes in China.

Coding was conducted iteratively by two researchers, with intercoder discussions to ensure consistency. Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

As researchers trained in economics and policy analysis, but also embedded in the Chinese sociopolitical context, our perspectives inevitably shaped how we framed research questions and interpreted discourses. To strengthen validity and mitigate bias, we used methodological triangulation with multiple data types and respondent validation by selecting interviewees reviewed preliminary findings. However, social-media data bias (platform demographics and censorship effects), and challenges in inferring causality between discourse and policy are main limitations. We remain cautious to interpret Chinese consumers’ narratives in prepared dishes especially those regarding traditional culture to ensure our analysis respects both theoretical methodology and China-specific context.

4 Analysis and results

4.1 Policy discourse on prepared dishes and food

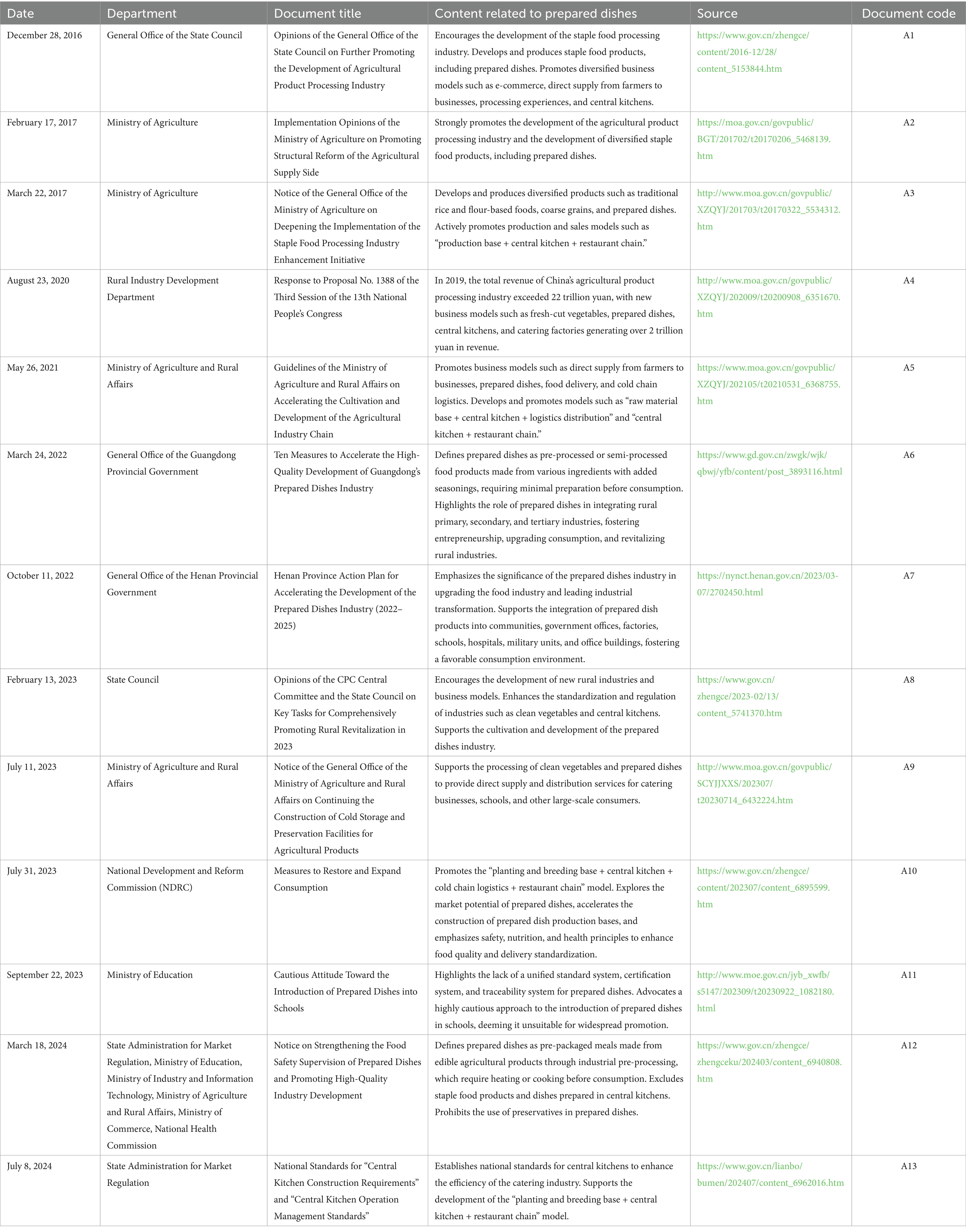

Government documents are the main evidence of ideas and discourses to manifest the prepared dishes and food. Table 3 lists the representative policies issued by central and provincial governments.

The first markable signs of the prepared dishes and food discourse emerging in China date back to 2016, with the terminology appeared in the “Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Further Promoting the Development of Agricultural Product Processing Industry,” marking a clear starting point.

“Encourage the Development of Staple Food Processing (鼓励主食加工业发展。)......Develop and produce a series of products such as traditional rice and flour foods, coarse grains, and prepared dishes and food (研制生产一批传统米面、杂粮、预制菜肴等产品)” (A1)

However, at that time, the term “prepared dishes and food” referred exclusively to processed staple food products, and the industry had yet to achieve the development typically driven by research and development efforts. The policy document employs positive wording by using terms such as “encourage” as modal verbs to frame policy implementation yet non-coercive with overall tone as cautiously supportive, which constructs a permissive rather than mandatory regulatory stance. Positive framing through words like “develop” served to legitimate state intervention. The concept of “prepared dishes and food” was initially positioned as a subset of “Stable Food Processing” (主食加工业), creating a discursive link to established agricultural practices while limiting conceptual expansion.

Besides, the terminology “central kitchens” was first appeared in this document as new business format with positive policy tone: “Actively develop new business formats such as e-commerce, direct farmer-to-business supply, processing experience centers, and central kitchens (积极发展电子商务、农商直供、加工体验、中央厨房等新业态)” (A1). The co-occurrence of “central kitchens” (中央厨房) as a “new business format” (新业态) introduced through evaluative language (“actively develop”) established a dual strategy of legitimizing both product innovation and systemic transformation.

In 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture further exemplified this cautious approach in its “Implementation Opinions of the Ministry of Agriculture on Promoting Structural Reform of the Agricultural Supply Side” and the subsequent “Notice of the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture on Deepening the Implementation of the Staple Food Processing Industry Enhancement Initiative”.

“Support major grain production areas in developing grain—particularly corn—deep processing, and develop diversified staple food products and functional foods that integrate food and medicine such as...... prepared dishes. (支持粮食主产区发展粮食特别是玉米深加工,开发......预制菜肴等多元化主食产品和药食同源的功能食品。)” (A2)

“Develop and produce a batch of traditional rice and flour products, coarse grains, pre-prepared dishes, etc. (研制生产一批传统米面、杂粮、预制菜肴等产品)”

“Actively promote the model of "production base + central kitchen + dining outlets"(大力推广“生产基地+中央厨房+餐饮门店”)”

“Take staple food processing industry and central kitchen construction as key support directions (将主食加工业、中央厨房建设作为重点支持方向)”

This document refined these strategies. The shift from “encourage” (2016) to “support” (2017) in “support grain-producing areas to develop grain deep processing” (支持粮食主产区发展粮食深加工) marked a strengthened policy commitment. This was coupled with prescriptive framing in “take staple food processing and central kitchen construction as key support directions” (将主食加工业和中央厨房建设作为重点支持方向), where “key support” (重点支持) functioned as a legitimating device for resource allocation. The “生产基地+中央厨房+餐饮门店” (production base + central kitchen + dining outlets) model operated as a spatial metaphor, conceptually mapping agricultural supply chains onto urban consumption networks. This interdiscursive strategy blended policy, logistics, and consumption discourse to construct a unified narrative of systemic efficiency. The repeated use of “develop and produce a series of products” (研制生产一批产品) across documents created a presuppositional framework where “prepared dishes” were implicitly framed as standardized, scalable commodities.

Although these documents employed positive words such as “support,” “develop,” “key support,” and regarding prepared dishes, they maintained a measured tone and allocated only limited emphasis to the concept of “prepared dishes and food” while “actively promote” word was used for central kitchen, which signaled high-priority innovation.

Prepared dishes regained attention after 2020. A government document from 2020 frames prepared dishes within an economic success narrative through precise numerical framing:, “In 2019, the total revenue of China’s agricultural product processing industry exceeded 22 trillion yuan, with new business models such as fresh-cut vegetables, prepared dishes, central kitchens, and catering factories generating over 2 trillion yuan in revenue.” At this point, the definition of “prepared dishes and food” had expanded beyond simply “a type of processed staple food product” to encompass “a category of processed dishes.” Economic data here functions not merely as descriptive statistics but as presuppositional evidence—implicitly framing prepared dishes as proven economic contributors. As prepared dishes demonstrated significant economic success, the industry quickly emerged as a reliable solution for boosting consumption and revitalizing the economy in the pandemic era. In 2022, both Henan and Guangdong provinces issued provincial-level documents that exemplify interdiscursive policy layering with the theme of “accelerating the development of the prepared dishes industry,” reflecting strong government support and proactive promotion at the provincial level. “Accelerating” functions as a directional modal verb that intensifies policy commitment beyond mere “support” (2020), creating a tiered policy hierarchy where provincial governments act as implementers of central directives. Prepared dishes started to be as standalone industry status.

In 2023, the statement “Supports the cultivation and development of the prepared dishes industry.” appeared in the Central No. 1 Document of the Chinese government, marking the formal establishment of policy discourse on prepared dishes and food at the national level. “Supports,” and “cultivation and development” operate as a high-modality verb and phrases that codifies prepared dishes within central policy frameworks, transforming regional experiments into national strategy. This discourse strategy rapidly and substantially expanded the visibility and influence of prepared dishes to the public, especially to consumers, aligning policy narratives under the authoritative framework of a central government document. As a result, the promotion of prepared dishes became an undeniable trend with series government policy documents being released at ministry level, provincial level, and city levels.

As an intermediary link between agriculture and the food service industry, prepared dishes and food hold dual legitimacy within policy discourse. On one hand, the industry extends the agricultural supply chain to rural residents and enhances the added value of agricultural products with order-based agriculture and contract farming models, enterprises establish direct procurement relationships with farmers. This not only ensure stable raw material supplies but promotes rural agricultural development and enhances agricultural value through standardized processing. This contributes to farmers’ income growth, aligning closely with the central government’s rural revitalization agenda. On the other hand, prepared dishes are deeply connected to urban food consumption, driving cost reduction and efficiency improvements in the restaurant industry while catering to consumer demand for upgraded dining experiences. This aligns with China’s broader goals of economic recovery and development.

4.2 Consumers’ discourses of prepared dishes and food

For consumers, “prepared food and dishes” is not a term derived from everyday life but rather an unfamiliar concept introduced through media and government documents. While the government has used policy discourse to guide macro-level food industrial planning, consumer discourse has not emerged before.

Some interviewees mentioned that before media coverage of prepared dishes, they had purchased frozen meals that required heating but had not realized they were part of a new industry. In other words, there is a discrepancy between consumer actions and discourse. Additionally, the concept of prepared dishes itself was ambiguous at first, as it encompassed ready-to-eat meals, canned foods, and convenience foods, further complicating the establishment of a clear consumer narrative.

4.2.1 Cultural discourse

There is an old Chinese saying, “Food is the necessity of the people and foundation of life.” (“Min yi shi wei tian,” 民以食为天), which highlights the fundamental importance of food in Chinese cultural tradition. The first discourse is emerged and rooted in the history and culture of the Chinese nation, and we label it as cultural discourse. Prepared dishes are perceived as a driving-out force to the traditional and natural dietary practices for consumers. “Prepared dishes can serve as an emergency solution, but if most of our daily food are made of prepared dishes, I believe it would be a forgetting of our culinary culture.” (B36) They are considered “not fresh” and unnatural because the journey from preparation to consumption involves a complex processing cycle, resembling a black box.

The cultural discourse against prepared dishes centers on evaluative language that constructs moral and health-based narratives. One of the primary arguments against prepared dishes in cultural discourse is the lengthy list of additives in their ingredient labels. Consumers use phrase “composed of obscure chemical terms” that operates as a framing device, positioning additive lists not as neutral information but as evidence of industrial malfeasance. Almost all the interviewees emphasize these chemicals are “unnatural,” “unfamiliar,” and “potentially harmful to human health.” These adjectives create a negative evaluation system and function as presuppositional triggers that implicitly assume that industrial processing which uses chemical additives is inherently opposite to “natural” and “healthy” food. The introduction of prepared dishes into school meals is viewed as a “harmful” and even “toxic” dietary practice on the next generation. This metaphorical escalation transforms prepared dishes from mere food products into symbolic threats to generational health, particularly when framed through school meal contexts.

As one interviewee put it:

“I’m an adult, so of course I can eat prepared dishes. But my child cannot. They are still growing and need genuinely healthy, freshly cooked and nutritious dishes and food. When I was young, I grew up eating fresh vegetables and freshly cooked dishes”. (B1)

The positive evaluation terms like “genuinely healthy” and “freshly cooked,” serve as cultural counterpoints to industrial prepared dishes. Here, “genuinely” does not refer to any actually existing nutrient that would appear on a package’s ingredient list. Instead, “genuinely” signifies a lifeway that is close to the land and nature, as well as the emotional process of personally participating in cooking. The phrase “When I was young, I grew up eating fresh vegetables” employs temporal framing to construct a nostalgic narrative of “authentic” childhood nutrition. This nostalgia functions as a legitimating device for rejecting contemporary industrial food practices.

Beyond concerns about food safety, cultural discourse also encompasses the defense of “taste.” Respondents of in-depth interview stated that prepared meals often contain too many spices that do not align with their personal preferences and overshadow the natural flavors of the ingredients. The phrase “overshadow the natural flavors” employs the overshadow metaphor to frame industrial spicing as a dominant force masking authentic taste. This metaphor constructs a zero-sum relationship between processed spices and natural ingredients, positioning prepared dishes as taste disruptors rather than enhancers. “Taste” relies on a unique, irreplaceable regional culture and family tradition, while the homogenization of dishes and food by industrial production, process and cooking procedures is perceived as a negative and a sign of disrespect toward traditional culinary culture.

Consumers also establish a connection between freshness and sentiment:

“It is more about sentiment: the appeal of freshly-cooked restaurants lies in the claim of using fresh meat and fresh vegetables” (B35)

The phrase “more about sentiment” introduces emotional label as a counterpoint to industrial efficiency. By contrasting “freshly-cooked restaurants” (framed through “fresh meat and fresh vegetables”) with prepared dishes, opponents emphasize emotional authenticity that privileges traditional cooking as emotionally superior.

Consumer practices reveal a conditional acceptance framework that mediates cultural values with pragmatic needs: When cultural discourse is expressed through practice, consumers typically “only purchase prepared meals when they are too busy with work to cook” (B3-B7), which introduces temporal constraints as cultural safeguards. This conditional acceptance preserves traditional cooking as the default while permitting prepared dishes as temporary exceptions, namely, a framing device that maintains cultural continuity. At the same time, they state their attention to the shelf life of prepared dishes and food, and tend to choose those with shorter shelf lives to minimize the impact of preservatives and other additives. The emphasis on “shorter shelf lives” and “minimize preservatives” demonstrates active risk management. By prioritizing products with shorter shelf lives, consumers enact a counter-discourse that challenges industrial norms of longevity over freshness. This practice transforms selection criteria into cultural statements about health and authenticity.

4.2.2 Distrust discourse

The challenges raised by cultural discourse were quickly absorbed into a broader narrative of distrust. Thus, we label the second discourse of consumers as distrust discourse. In China, with the high ownership rate of smartphones and high coverage of mobile networks, citizens actively engage in discussions on social issues through social media and other online platforms. Large-scale discussions on social media shape public opinion, making it a crucial channel for conveying ideas, opinions and for expression of policy criticism. Opponents construct distrust through intertextual scandal referencing, linking prepared dishes to past food safety scandals and food fraud in China, constructing a continuous narrative of cause and effect. They portray prepared dishes as a further erosion of consumers’ right to information and oversight, while also criticizing the government for its ongoing absence in regulatory and food law enforcement and forceful food safety governance. They predominantly employ terms such as “food safety” and “hard to trust” to frame prepared dishes as inherently untrustworthy due to perceived information asymmetry (“we have no idea under what production environment”). They emphasize that these dishes are not safe through the use of words like “mysterious” to underscore the information asymmetry they perceive. The word “mysterious” functions as a linguistic marker of epistemic uncertainty, amplifying distrust through semantic ambiguity.

“Even infant formula can be adulterated with melamine, and a rat's head mixed in the meals can be called a duck's neck. In such a food safety environment, it is hard for me to trust the food safety of prepared dishes and food. Compared to the factories produced prepared dishes and food, the kitchens of canteens and restaurants are more accessible to consumers for information. However, prepared dishes and food cut off this avenue for information symmetry; we have no idea under what production environment and hygiene conditions they are produced. I trust the meals and dishes I prepare by myself or by a real chef rather than those with “mysterious” seasoning packets”. (B4)

Phrases like “infant formula adulterated with melamine” and “rat’s head called duck’s neck” operate as metonymic devices, transferring negative associations from past scandals to contemporary prepared dishes. This creates a presuppositional chain where prior regulatory failures presuppose future risks.

Prepared dishes and food quickly became synonymous with “products without a brand, quality certificates, or production date, (“三无产品”)” implying that they originated from underground, unhygienic workshops that had evaded government regulation. Radical opponents swiftly identified schools and catering enterprises and restaurant that used prepared dishes and called on people on social platforms to avoid purchasing specific dishes from them and boycotted these enterprises. “Avoid purchasing specific dishes and boycotted these enterprises” exemplify performative distrust that transforms individual skepticism into collective action. This mobilization relies on intertextual scandal narratives to legitimize boycotts as moral imperatives.

4.2.3 Industrialization discourse

The industrialization discourse on prepared dishes and food conveys the ideas that prepared dishes and food is the conceptual starting point for explaining institutional change for food and catering industry. It associates prepared dishes and food with the concept of “modernization” and efficiency narratives, portraying the increasingly complex food processing industry as a process of dietary modernization and regards prepared dishes and food as the modernization of culinary practices. Prepared dishes and food are embodied as efficiency, standardization and convenient for consumption. They are produced and packaged in a high-hygiene, clean, standardized and precise manner in large factories, replacing chaotic individual food workshop and inefficient kitchens. Ultimately, they appear on consumers’ dining tables at the fastest speed with their flavor and appeal preserved.

“In many supermarkets in China and abroad, after purchasing prepared dishes, consumers can have them heated on-site, which is quite common. The outer packaging often indicates that the preparation instructions are ‘for reference only’. In practice, these products already achieve a heating completion rate of over 80%. Japan does well in this area”. (B35)

Phrases like “quite common” and “over 80%” employ statistical validation to frame on-site heating as a normalized market practice. The phrase “Japan does well” operates as intertextual legitimacy device, borrowing authority from international benchmarks to validate domestic practices.

By incorporating prepared dishes and food within a broader socio-historical context, the industrialization discourse explains them as an embodiment of “inevitable modernization” of food sector:

“The United States and Japan already have mature prepared meal industries, and the prepared meal model has been in operation for decades. With China's ongoing modernization and urbanization, the development of the prepared meal industry in China is also inevitable”. (B20)

The phrase “mature prepared meal industries” in US/Japan contexts functions as presuppositional evidence for China’s “inevitable” modernization. By anchoring discourse in “decades” of operational experience, industrialization proponents construct a teleological narrative where prepared dishes embody progressive modernity.

The industrialization discourse employs science to justify the use of additives in prepared dishes and food and to counter distrust while acknowledging regulatory importance. By precisely regulating the dosages of additives, those exceeding the limit are identified as “harmful,” while those within the limit are deemed “safe.” One respondent articulates in this way:

“As long as the additives are clearly listed on the packaging of prepared meals and their dosages comply with regulations, there is no reason why prepared meals should not be trusted”. (B30)

The phrase “clearly listed. Dosages comply with regulations” constructs scientific legitimacy through procedural transparency. The double-negative “no reason why. Should not be trusted” transforms compliance into moral imperatives, framing distrust as irrational when science is properly applied.

However, the industrialization discourse is also susceptible to challenges from distrust discourse. The modernization scenarios depicted by the industrialization discourse are perceived as overly optimistic. Compared with the good traits and characteristics of the industrialization of food and catering industry that remain largely invisible to most consumers, the food safety issues exposed by the media are far more tangible. Data and standards by enterprises are not entirely accepted by consumers, “the development of prepared dishes is being driven primarily by large enterprises” (B35), whose regulations are not stringent enough to gain consumer trust. The admission that regulations are “not stringent enough” and development is “driven by large enterprises” introduces critical realism that advocates for political intervention. Therefore, the industrialization discourse requires actors beyond “science” to gain legitimacy. In other words, the industrial discourse needs the government to engage the public in a communicative discourse about the necessity and appropriateness of the industrialization of food and catering industry, i.e., it needs to be in synergy with policy discourse.

4.3 Story line and discourse coalition

Marked by the introduction of the National Standard for prepared dishes, the discourse debate can be divided into two stages, in which the dominant discourse coalition is different.

4.3.1 The first stage: consumer internal discourse coalition is stronger than policy discourse coalition (Feb 2023- June 2024)

Even before “prepared meals on campus” made the news in early September 2023, the promotion of prepared meals in schools was documented in government documents:

“Carry out the processing of pure vegetables and prepared vegetables and provide direct supply and distribution services for catering enterprises, schools and other terminal customers”. (A15)

“Support prepared food products into communities, institutions, factories, schools, hospitals, military camps, office buildings, etc., to create excellent atmosphere for prepared food consumption”. (A16)

For policy makers, the industrial development and economic growth is taken into consideration for the promotion of prepared dishes and food, so policy is set accordingly and implemented in a top-down manner by the government. In the policy discourse for prepared dishes, the arrows of discursive interaction go from the top down by policy. Enterprises and policy makers generate ideas, then policy makers communicate to the public by presenting policy documents and corresponding strategies and measures. The master discourse represented by various policy documents provides a vision of where the polity is, where it is going, and where it ought to go. The key discourse is to foster central kitchen and facilitate the progress for food industrialization. While the use of government authority to introduce prepared dishes into campuses, a potential consumption setting, is another process of implementing policy discourse.

For consumers, however, the commercial success of prepared dishes does little to alleviate concerns. “The concept of prepared food has emerged suddenly. There is few authoritative explanation as to what it exactly is, nor are there any authoritative regulations specific for it, at least I did not know.” (B38) The respondent’s comments were echoed by other interviewees. So, the government did not successfully implement the communicative discourse with the public opinion, as few direct discussion between government and consumers was set and less favorable aspects of prepared dishes were framed by the mass media after the year of 2023 when Central Document No. 1 officially introduced the concept of prepared dishes, thus preventing the public from viewing prepared dishes in a positive light. Unlike the macro perspective of policy discourse, consumer discourse is rooted in individual consumer behavior. The “prepared food into the campus” implemented without effective communication and consultation with the stakeholders, is perceived as the policy bypassing the formulation of a successful communicative discourse directed to consumers, thereby failing to capture the sustained interest and acceptance of consumers. Some consumers regard it as reducing consumer’s chance to make independent choices and exercise oversight.

“Consumers typically buy prepared dishes, and if they don’t like them after trying once, they simply don’t buy them again. However, once prepared dishes are introduced into schools, students and parents have less chances to make choices”. (B17)

The school canteen has drawn continuous attention of parents and media due to its particular serviced consumers: minors. The students’ food safety issues involve the broader well-being of future generations, making it a matter of both emotional concern and ethical responsibility. A photo of a “prepared dishes in the school cafeteria with a shelf life of 1 year” has been widely circulated on social media, further causing widespread anxiety among consumers. In this context, the image of “prepared dishes” has shifted, from an emerging and modern food industry as described in government documents, to being perceived by consumers as poorly made products from small, unregulated workshops, and as unhealthy meals full of additives, created through “technology and extreme methods” with a lack of freshness. The industrialization discourse characterized by efficiency and scientific discourse has been suppressed, while cultural discourse and distrust discourse have quickly coalited to resist prepared dishes and food at early stage.

Centered around cultural discourse and distrust discourse, the storyline that “prepared dishes use non-fresh ingredients, contain large amounts of harmful additives, and should be consumed as little as possible” has facilitated the emergence of an internal consumer discourse coalition. The consumer coalition constructs distrust through intergenerational protectionism and historical trauma narratives:

“Chinese parents want to give their children the best dishes and food, just for their children to have a good health. Prepared dishes and food has such a long shelf life that it's literally overnight leftovers. Experts say that overnight food is not fresh, why do we have to let the child have prepared dishes and food?” (C3)

“We Chinese have finally got rid of the title of the sick man of East Asia, and this prepared dishes and food might weaken the physical fitness of our future generation”. (B10)

The phrase “overnight leftovers” operates as a presuppositional device, framing long-shelf-life prepared dishes not as convenient solutions but as degraded food products. This metaphor leverages expert discourse (“overnight food is not fresh”) to create epistemic authority, transforming personal anxiety into collective distrust. The invocation of “sick man of East Asia” employs intertextual trauma narratives to amplify health anxieties.

The coalition employs precautionary logic to challenge industrialization narratives. One respondent from school put it this way: “Prepared dishes and food is a new thing and cannot be experimented on children (C10)”. If radical scientism holds that “something is safe to eat as long as it has not been proven harmful,” then the conservative discourse coalition among consumers against prepared dishes and food argues that “if it cannot be proven harmless, it should not be promoted”.

However, although the industrialization discourse and the policy discourse at this time formed the story line of “prepared dish is a product of modern food industry that meets scientific and food safety standards and is also an inevitable result of development of food and catering sectors,” and the discourse coalition was formed around the story line, due to the lack of unified standards and definitions for prepared dishes and food, the industrialization discourse could not be effectively combined with the policy discourse, and the communicative discourse to the public was weak. Many consumers accepted and understood the development of the food industry but argued that the corresponding government regulations were insufficient and it was difficult to build trust. Furthermore, the early policy discourse lacks the explanation of the terminology of prepared dishes and food from the perspective of consumers.

“The process and production standards are not fully disclosed. It is also unclear whether the state will issue regulations requiring enterprises that produce or use prepared dishes to follow a specific regulatory process. If the state enforces a policy mandating that prepared dishes adhere to a defined set of standards, with proper supervision in place, I would have no concerns. However, the issue is that I am unsure whether such regulations exist”. (B19)

Therefore, compared to policy discourse, the internal discourse coalition between consumers’ cultural discourse and distrust discourse dominates. Amid intensifying public debate, on September 22 2023, the Ministry of Education issued a statement titled “A Cautious Attitude toward Prepared Dishes in Schools”. The statement explicitly asserted that prepared dishes should not be promoted in schools, directly addressing consumer concerns and moderating the previously radical practice. At the same time, it repositions prepared dishes as lacking adequate regulation, thereby laying the groundwork for the future introduction of more standardized policy and regulation.

However, the controversy over prepared dishes has not stopped. The field of discourse debate has gradually shifted from the specific consumption scenarios of prepared dishes such as school canteen to the whole catering industry. Since the government had not clearly defined prepared dishes at that time, the widely circulated definition came from industry standards at that time is:

“Prepared dishes are pre-packaged finished or semi-finished meals made from agricultural, livestock, poultry, and aquatic products through pre-processing or pre-cooking. Based on factors such as the extent of pre-processing, subsequent treatment, seasoning, whether the dish is served cooked or raw, and shelf life, these meals can be categorized into four types: ready-to-eat, ready-to-heat, ready-to-cook, and ready-to-assemble”.

For restaurant businesses, using prepared dishes is a cost-cutting and efficiency-boosting option. Standardized industrial processes not only reduce labor costs but also ensure prompt service and stringent quality control. However, due to the lack of transparency in restaurant kitchens, consumers find it difficult to gage the extent of pre-processing used in these dishes. Dining out is about more than just the food, it’s also about the overall dining experience, including the expectation that dishes are prepared and stir-fried fresh on the spot in the kitchen. Consequently, the use of prepared dishes by restaurants and canteens is often seen as an undisclosed form of corner-cutting by restaurants. A respondent said in this way:

“Restaurants that use prepared dishes merely reheat them in the kitchen before serving, yet still charge the prices of freshly cooked meals—this is simply unacceptable. Dining out is all about enjoying the freshness and authentic wok flavor; substituting prepared dishes for freshly prepared food completely undermines the experience and are hard for me to accept”. (B39)

Opponents of prepared dishes and food quickly identified restaurants that used prepared dishes and took to social platforms to urge people to avoid buying specific dishes they offered. The primary reason for the failure of communicative discourse on prepared dishes and food is that, while the government has been actively promoting the prepared food industry, it has not provided consumers with any guidance or clear explanation on prepared dishes and food, such as the “Prepared Dishes and Food Consumption Guide.” As a result, the negative story line of the consumer internal discourse coalition has put pressure on the catering sector.

4.3.2 The second stage: policy discourse adjustment, policy discourse storyline dominated (from June 2024 onwards)

In March 2024, the State Administration for Market Regulation, along with five other government departments, jointly issued the “Notice on Strengthening the Supervision of Prepared Dishes and Food Safety and Promoting the High-quality Development of the Industry” and hosted a corresponding Press Q&A, marking a significant adjustment and shift in policy discourse. The definition of prepared dishes and food is defined clearly as follows:

Prepared dishes and food are pre-packaged meals made from one or more edible agricultural products and their derivatives, with or without added seasonings or auxiliary ingredients, and without preservatives. They undergo industrial pre-processing—such as mixing, marinating, tumbling, molding, stir-frying, deep-frying, roasting, boiling, or steaming—and may be accompanied by seasoning packets. These dishes must meet the storage, transportation, and sales conditions specified on their labels and can only be consumed after heating or further cooking. However, staple foods such as frozen noodle and rice products, instant foods, boxed meals, rice bowls, steamed buns, pastries, roujiamo, bread, hamburgers, sandwiches, and pizzas are excluded from this category.

Considering that chain restaurants widely adopt the central kitchen model, the fresh-cut ingredients, semi-finished, and finished dishes they produce and distribute to their own outlets must comply with food safety laws, regulations, and standards for the restaurant industry. However, dishes prepared in central kitchens are not classified as prepared dishes and food.

It is clear that the official definition of prepared dishes is much narrower than the previous industry definition. This may be because the policy discourse has abandoned the use of “prepared dishes and food” as a unifying concept for the industrialization of catering and has sought to refine the definition of “prepared dishes and food” as much as possible to limit the proliferation of distrust discourses. Prior to this, a series of restaurants using prepared dishes were boycotted by consumers due to the negative assumptions implied by the term “prepared dishes and food”. Posts titled “How to tell if a restaurant uses prepared dishes” and “Restaurants that refuse to use prepared dishes” gained a lot of attention on social media.

In order to support catering enterprises, the policy discourse uses the expression “central kitchen” to rename “prepared dishes of qualified catering enterprises,” distinguishes standardized and large-scale enterprises and restaurants from small and scattered catering workshops, and guides consumers to re-establish trust in the former. The government’s redefinition employs prescriptive modality through phrases like “must comply with food safety laws” to construct regulatory legitimacy. This framing transforms compliance into a mandatory requirement, embedding policy discourse within existing regulatory frameworks. The phrase “not classified as prepared dishes” operates as a categorical exclusion device, creating a semantic boundary between central kitchen outputs and industrial prepared dishes. This move can also be understood as a shift in the focus of policy discourse from “prepared dishes and food” to “central kitchens,” boosting support for the latter and weakening the negative impact of the former.

By specifying “fresh-cut ingredients, semi-finished, and finished dishes” must adhere to restaurant industry standards, the policy aligns central kitchen production with established food safety norms. This intertextual borrowing leverages existing regulatory credibility to legitimize central kitchen practices while distinguishing them from industrial prepared dishes. The exclusion clause (“not classified as prepared dishes”) functions as a risk-mitigation strategy. By separating central kitchen products from the negative associations of industrial prepared dishes (e.g., additives, long shelf life), the policy attempts to preserve consumer trust in chain restaurant freshness while maintaining regulatory control. Neutral evaluation terms like “fresh-cut ingredients” and “semi-finished” avoid negative connotations associated with “prepared dishes,” enabling the policy to navigate consumer distrust without directly confronting it.

At the same time, the policy discourse also uses “no preservatives” as a new discourse strategy to cater for cultural discourse and align with industrialization discourse.

Although prepared dishes have been industrialized, they still belong to the category of dishes. Consumers generally do not add preservatives in their own cooking process of dishes, and the provision of no preservatives in prepared dishes is more in line with consumer’s expectations. For food additives, “if unnecessary, then not to add” and “minimize the use of food additives in dishes and food as much as possible while ensuring the desired effect” have gradually become the consensus of the prepared dish and food industry. After undergoing storage processes such as freezing and refrigeration, as well as post-processing sterilization, prepared dishes have no technical necessity for the use of preservatives.

An important element of cultural discourse is consumers’ concern on food additives. “No preservatives” responds precisely to the demands of consumers, shaking up the original narrative produced by cultural discourse that “prepared dishes are not healthy.” Notably, the government’s ban on preservatives in the prepared dishes and food is not driven solely by public concern, but is legitimized by catering for consumers’ industrialization discourse and scientific discourse of food sector. By enforcing “minimizing the use of additives” as the industry consensus of the prepared dishes and food, and defining “cold chain transportation” as the future development direction of the prepared dishes industry, “no preservatives” becomes an inevitable requirement for the upgrading and modernization of the food industry.

At this stage, policy discourse has been adjusted and strategically combined with cultural discourse and industrialization discourse to form a new story line, that is, “Prepared dishes are industrially processed dishes, and the entire industry is under the strict supervision of the state and can be purchased with confidence.” The new story line has effectively convinced the majority of consumers and catering enterprises. With the introduction of national standards and the implementation of regulatory measures, the institutionalization of discourse has been realized.

5 Discussion

5.1 The discourse evolution of prepared dishes in China

5.1.1 Three key stages of the dynamic relations between consumer discourses and government discourses

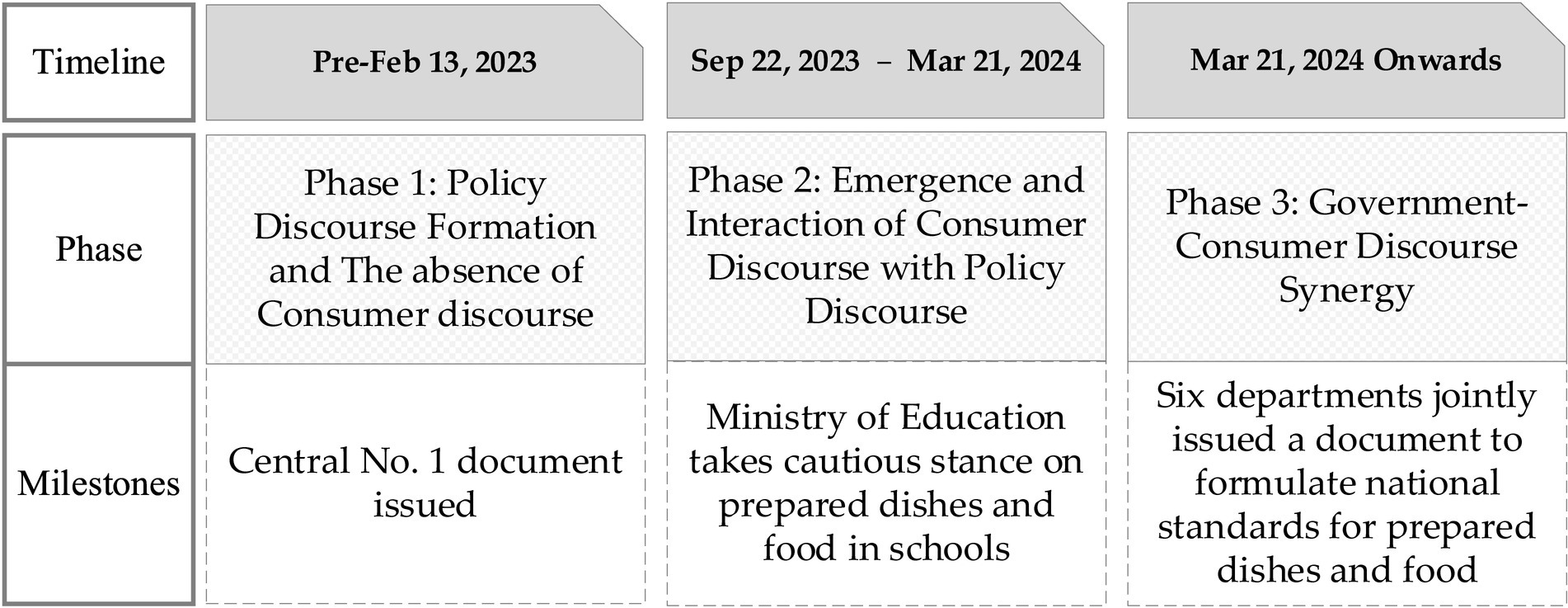

According to the empirical analysis, the discourse evolution of prepared dishes in China could be divided into three stages as shown in Figure 1.

5.1.1.1 Stage 1 (pre-February 13, 2023): policy discourse formation and consumer discourse absence

Prior to February 13, 2023, the discourse emerges for the prepared dishes industry was predominantly shaped by policy-driven narratives marked by the issuance of central No.1 document in 2023. During this phase, governmental and regulatory agencies and enterprises were the primary architects of the discourse, establishing sketchy frameworks related to food safety, quality assurance, traceability and other related elements for food industrialization discourse. At this stage, government policy discourse, as seen in public released policy documents, embeded prepared dishes with “the development staple food processing” and mixed with the terminology of “central kitchen.” Policies emphasize centralized production facilities and food processing. This constructs a general discourse of industrial progress and new food initiative, which positioned prepared food as solutions to time-scarce lifestyles.

However, regulatory standards were not clearly communicated in theses policy discourse. At this stage, consumer discourse was notably absent as prepared dishes and food are a new concept to them, indicating that the public’s perspective had not yet been integrated. This top-down approach reflects an early developmental stage where industry norms and practices were defined mainly by enterprises and policy imperatives rather than by consumer needs or preferences.

5.1.1.2 Stage 2 (September 22, 2023 – march 21, 2024): emergence and interaction of consumer discourse with policy discourse

Between September 22, 2023, and March 21, 2024, a significant shift occurred as consumer discourse began to emerge and interact with the existing policy narratives. During this period, consumers increasingly voiced their opinions, concerns, and preferences regarding prepared dishes through various channels. This emerging consumer discourse introduced new dimensions to the debate, highlighting issues such as product authenticity, traceability, taste, and overall food safety from the consumer’s perspective. The interaction between consumer and policy discourses catalyzed a re-evaluation of existing regulatory measures and policies, prompting policymakers to integrate consumer’s discourses into their policy frameworks. This phase is marked by a dynamic exchange where consumer experiences and expectations started to influence policy refinement, aligning regulatory objectives more closely with market and public sentiment.

At this stage, consumer discourse, derived from Medias and online platforms posts and in-depth interviews, reveals a contrasting narrative from policy discourses. Users frequently describe prepared dishes as “processed = unhealthy, loss of traditional catering culture,” linking them to “additives,” “preservatives,” and “loss of wok styles,” cultural discourse and distrust discourse emerge as consumers’ main representations of prepared dishes that contest government discourse. These dual representations create a discourse of paradox that government promotes food industry development, while consumers prioritize traditional catering culture and information symmetry for cooking process. However, at this stage, certain consumers, such as urban professionals and time-pressed households, exhibit discursive alignment with government agendas, where their industrialization discourse such as “standardized production ensures safety” and efficiency-seeking behaviors such as using prepared dishes to save cooking time converge with state-driven narratives promoting prepared dishes as pillars of modern food industrial progress.

5.1.1.3 Stage 3 (from march 21, 2024 onwards): formation of a government-consumer discourse synergy

Starting on March 21, 2024, the government’s formalization of an official definition for prepared dishes and food and its explicit separation from “central kitchen” constituted a pivotal policy milestone in addressing consumer skepticism, which is through coordinative discourses that clarify regulatory standards that emphasize it “must meet the storage, transportation, and sales conditions specified on their labels” and communicative discourses that emphasize transparency, taking public opinions as consultations, and labeling, thereby directly countering distrust by aligning policy frameworks with consumer demands for safety, authenticity, and accountability of prepared dishes and food industry. At this stage, the policy document explicitly emphasizes the compliance of central kitchen-produced dishes with stringent food safety laws, industry regulations, and restaurant standards, which is a critical mechanism by which government discourses directly counter consumer skepticism by institutionalizing accountability, ensuring traceability, and aligning dishes made in central kitchen with empirical benchmarks for hygiene and transparency. This is the discourse institutionalization stage in which both government and consumers actively collaborate in shaping the industry’s narrative. Policy makers act with consumer insights taking into decision-making processes, thereby enhancing transparency, responsiveness, and trusts of consumers.

5.1.2 Ideas, presentations, and practices of governments and consumers

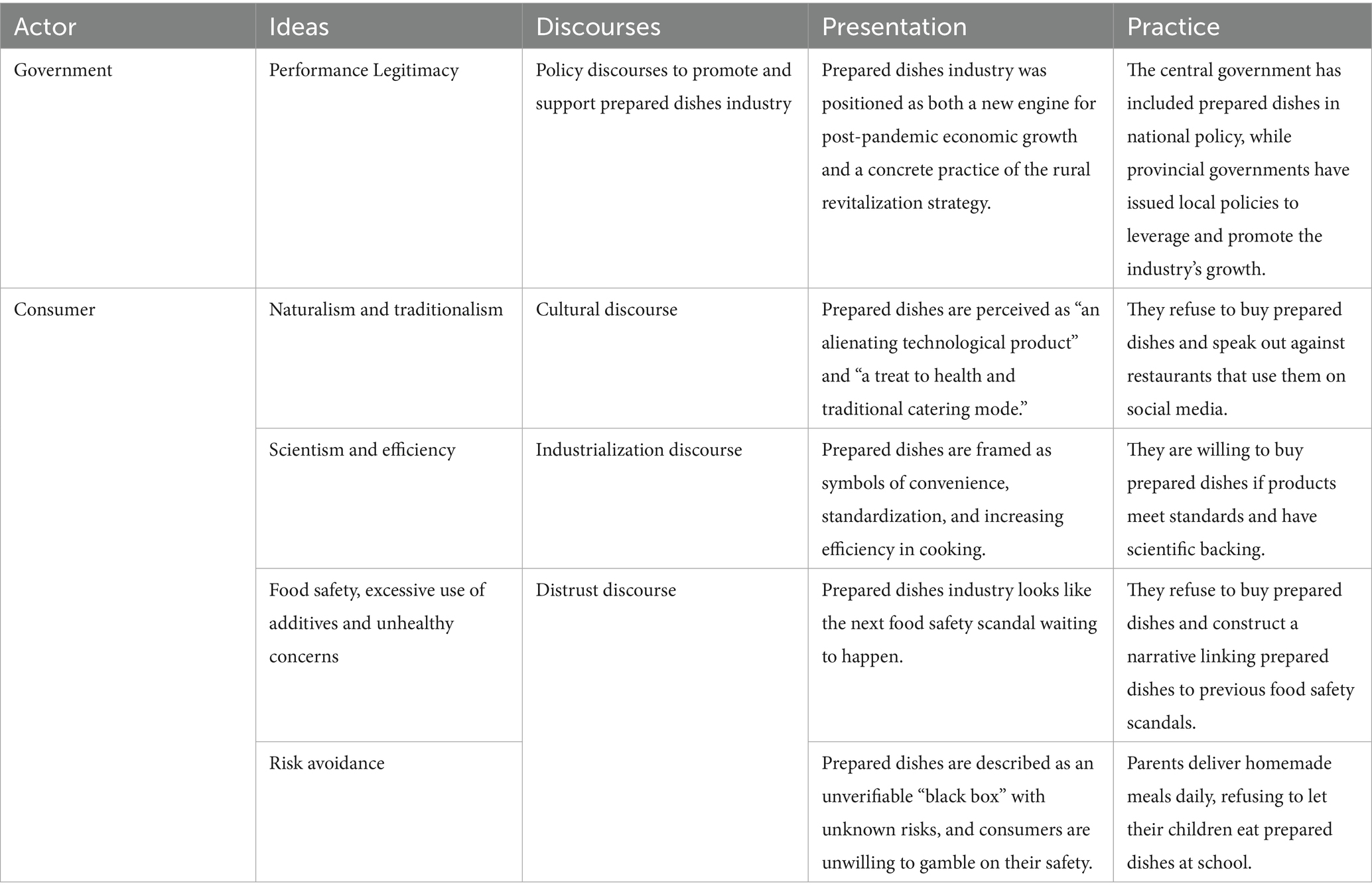

Table 4 shows the ideas, presentations and practices of governments and consumers.

There is a complex interplay of ideologies and practices on prepared dishes from the perspective of governments and consumers.

Consumer discourses are characterized by a diversity of perspectives, reflecting varying degrees of trust, risk perception, and cultural values. A typical consumer group, influenced by naturalist and traditionalist ideologies, perceives prepared dishes as a technological intrusion that undermines Chinese traditional food culture. Their opposition is voiced through social media platforms, where they actively boycott prepared dishes and criticize restaurants that incorporate them into their menus, thereby constructing a counter-discourse that challenges the industry’s legitimacy. A segment of consumers exhibits risk-averse behavior, conceptualizing prepared dishes with unknowable dangers. In practical actions, parents opt to deliver homemade meals to their children’s schools, thereby rejecting the perceived safety risks associated with prepared dishes. Some consumers even view the prepared dishes industry as a potential breeding ground for future food safety scandals. This distrust is rooted in historical precedents and is perpetuated through narratives that link prepared dishes to past incidents of food contamination, thereby constructing a distrust discourse with skepticism and caution. Conversely, proponents of scientism and efficiency embrace prepared dishes as emblematic of convenience, standardization, and efficiency. Their discourse emphasizes the importance of scientific validation and adherence to established standards, suggesting a conditional acceptance of prepared dishes under the condition that these criteria being met. This reflects a broader societal shift toward efficiency and rationality in food consumption choices and forms industrialization discourse.

The government, leveraging the concept of performance legitimacy, has positioned the prepared dishes industry as a cornerstone for post-pandemic economic recovery and a practical food initiative of the Rural Revitalization. This ideology is framing through policy instruments, with the central government embedding prepared dishes within national policy agendas, while provincial governments devise and implement localized strategies to catalyze growth and development of prepared dishes and food industry.

5.2 Findings from empirical analysis

On the side of discursive interaction, we have seen how such ideas and policy may be consciously or unconsciously reflected in key actors of governments’ discourse as they coordinate agreements in the policy sphere and as they communicate to the markets and the public. Therefore, the bottom-up collective ideas and “everyday practices and norms” of the consumers and the markets are important for the institutionalization of prepared dishes and food. By separating out the different discourses of consumers and different stages of interaction between consumers and policy makers regarding prepared dishes and food, we also better understand the difficulties that governments may have in arriving at institutions of food industry that satisfy the markets and the consumers.

The core contribution of this paper lies in revealing how, within the policymaking and policy communication process, the introduction and promotion of new food initiative in the industrialization of food sector are facilitated through discourses, fostering interaction and consensus-building between consumers and policymakers (Fröhlich, 2024; Wang et al., 2022). Firstly, similar to previous studies on consumer trust and food consumption (Fröhlich, 2024; Wang et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; László et al., 2024), this study further evidenced that consumers and the government interact in a mutually embedded way within the discourse narrative. While the initial promotion of prepared dishes and food for the industrialization of food sector was largely driven by promotion-oriented considerations of the government, the policymaking process has nonetheless been shaped by ongoing trial and error, evaluation, refinement, and various discourse narratives and practices aimed at facilitating its promotion, thus further validating that China’s food governance not only through coercion but also through steering and citizen responsibility (Fröhlich, 2024).

Secondly, the narratives and understandings of prepared dishes and food among different consumer discourses, as well as the relationship between consumer discourse and policy discourse, can be interpreted through the concept of discourse coalitions. For the theoretical approach adopted in this study, we found that the discourse analysis theory and discourse institutionalism proved to be useful for studying new food initiatives and policies (Fischer and Forester, 1993; Hajer, 1993; Schmidt, 2008; Sibbing and Candel, 2021). In this study, discourse serves not only as a vehicle for consensus-building between the government and consumers, influencing policy outcomes, but also as a key arena for the subtle negotiation, persuasion, and debates between the two (Schmidt, 2008). On one hand, the results of this study add new empirical evidence from China’s food sector to the consistence in the scholarship of food governance and indicates the importance of governments’ actions toward new food initiatives (Chen et al., 2023; Taufik et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2025; Fröhlich, 2024), and the government continuous regulation and guidance on prepared dishes and food. On the other hand, this study justifies conclusions drawn by previous studies on consumer’s trust, attitudes and perspectives on different food and food fraud (Feng et al., 2023; Hristov et al., 2023; Macready et al., 2025; Morosan et al., 2025; Sahin and Gul, 2023; Xing et al., 2022), and further finds out that consumers leverage discourse as a means to advocate for broader culture, food safety and trust in consumption and stringent regulation measures from government for a new food initiative and for the industrialization of food sector.

5.3 Prepared dishes within sustainable food system discourse

In this analysis, consumer discourses about prepared dishes, particularly concerns about additives, processing methods, and freshness, highlight a tension between the convenience offered by these products and the public demand for health, safety, and nutritional integrity (Shu et al., 2024). These concerns align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that emphasize the promotion of healthy diets. If unresolved, persistent distrust may limit the role of prepared dishes in contributing to dietary transitions toward more balanced, accessible, and safe food options in urban China. At the same time, the negative framing of prepared dishes may obscure opportunities to reformulate such products with healthier ingredients, improved traceability, and clearer nutritional information. Therefore, policy discourses that respond to distrust discourse, align with industrialization discourse, and find a niche to interact with cultural discourse would be vital for legitimating and institutionalization of prepared dishes in China. Besides, the skepticism expressed by consumers contrasts with the governments’ initial aim of promotion of prepared dishes as a modern and efficient food solution. This discursive misalignment underscores the need for participatory governance mechanisms that can reconcile consumer expectations with policy ambitions. Incorporating sustainability solutions into both policy narratives and consumer communication strategies could help bridge this gap and foster public trust.

Moreover, the governance and institutionalization of prepared dishes, currently propelled by large enterprises and supported by policy initiatives, have direct consequences for food system sustainability. Large-scale production can reduce costs, standardize quality, and potentially minimize household food waste by offering portion-controlled and shelf-stable products. On the other hand, industrialization raises concerns about environmental sustainability, including packaging waste, energy use in processing, and carbon emissions from cold-chain logistics. Policy discourses that predominantly frame prepared dishes as an industrial or economic growth strategy risk should pay more attention to these environmental dimensions. Therefore, separating the term prepared dishes with central kitchen has been a vital step for the governance of sustainable food system in China.

6 Conclusion

6.1 The discourse evolution of prepared dishes in China

The discourse surrounding prepared dishes and food in China reflects a complex dialog between state-driven industrialization, consumer concerns, and the evolving food policy landscape. This study reveals that: