- 1Department of Social Science and Agribusiness, International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

- 2Department of Entomology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

Postharvest losses in staple crops such as maize continue to undermine food security and farmers’ incomes in sub-Saharan Africa, despite the availability of safe and effective storage innovations like hermetic bags. Understanding how institutional support mechanisms influence the adoption of these technologies is critical for designing interventions that promote their widespread use. Among these mechanisms, training and access to credit play a vital role by helping to overcome knowledge gaps and financial constraints that often hinder the adoption of agricultural innovations. This study assessed how access to training and credit—individually and in combination—affects adoption intensity, measured as the proportion of maize stored in Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bags, among smallholder farmers in Tanzania. We applied a multivariate inverse probability weighting approach and Tobit model to household survey data from 908 households in two regions of Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. Results show that 45.4% of households used PICS bags for maize storage. Access to either training or credit increased PICS bag adoption intensity by 15.6 and 12.9%, respectively, compared with households that received no intervention. However, when both training and credit were provided together, adoption intensity rose by 36.6%. These findings highlight the importance of integrating training and credit to increase the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags. Efforts to promote hermetic storage technologies should include improving access to finance through both traditional and non-traditional approaches to optimize adoption intensity and further reduce postharvest losses.

1 Introduction

Postharvest storage losses (PHL) are a major challenge among smallholder farmers in developing countries, including Tanzania (Abass et al., 2014; Kumar and Kalita, 2017). These losses reduce the market value of maize by approximately 15% in Tanzania (MoA, 2019). While Tanzania’s domestic food production is generally sufficient to meet its population’s consumption needs, PHL still contributes to periodic food shortages, leading the country to import food valued at over USD 200 million annually (Mutungi and Affognon, 2013). The Government of Tanzania recognizes that reducing PHL offers an excellent opportunity to reduce hunger. This is part of its commitment to the 2014 Malabo Declaration, specifically the third resolution, which commits Member States of the African Union to “halve the current levels of PHL by 2025” and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which call for reducing food losses along production and supply chains by 2030 (AUC, 2014; UN, 2015).

Hermetic storage technologies (HSTs) have proven effective in minimizing maize PHLs (Villers et al., 2006; Mlambo et al., 2017; Abass et al., 2018). Prior to their introduction, farmers primarily relied on traditional storage methods such as woven sacks or local granaries, which provided limited protection against pests and often required the use of chemical pesticides. While these pesticides help reduce storage losses, they pose serious risks to human health and the environment due to their misuse and overuse. Moreover, traditional storage methods limit farmers’ ability to store maize for extended periods, leading to both economic and food security challenges. Hermetic storage technologies, including hermetic bags, are a viable alternative to traditional storage and chemical use. These technologies not only extend storage duration but also improve food safety by reducing reliance on harmful pesticides and mitigating aflatoxin accumulation (Walker et al., 2018).

To promote the adoption of hermetic bags, various interventions have been implemented across sub-Saharan Africa (Tefera et al., 2011; Foy and Wafula, 2016; Tanager, 2018; Baributsa, 2024), many of which focus on training to ensure proper and effective usage. Training has been particularly effective in addressing key barriers by enhancing farmers’ knowledge of postharvest management and promoting chemical-free storage solutions, such as Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) bags. Studies have shown that training significantly increases farmers’ awareness, knowledge, and confidence in using hermetic storage methods (Moussa et al., 2011; Muriuki et al., 2016; Dhehibi et al., 2022). Training also leads to higher adoption rates and increases grain storage volumes (Moussa et al., 2014; Zacharia et al., 2024).

Beyond training, access to credit also plays a critical role in facilitating the adoption of postharvest technologies (PHTs), hence improving food availability for household consumption and market sale (Rasanjali et al., 2021; Dube-Takaza et al., 2023; Esnaashariyeh et al., 2023; Rayhan et al., 2023; Regassa et al., 2023; Abate, 2024). Training and credit are complementary institutional mechanisms that address distinct yet interconnected barriers to adoption. Training enhances human capital by improving knowledge, reducing uncertainty about technology use, and lowering perceived risks. It may also reduce farmers’ reluctance to apply for loans. However, even trained farmers may face financial constraints. In such cases, credit acts as a financial enabler, allowing them to purchase PICS bags and alleviate time constraints associated with attending training, such as lost labor time. When provided together, training and credit can generate a synergistic effect. Training raises awareness and increases the willingness to adopt, while credit enhances the capacity to act. Therefore, examining their combined effect offers valuable insights into how integrated institutional support influences not only the decision to adopt a technology but also the extent of its use.

Despite this potential, few studies have examined the combined effects of training and credit on adoption intensity, measured not only by whether farmers adopt a technology but also by the extent to which they utilize it. Most previous adoption studies relied on binary adoption indicators, which can obscure meaningful variation in usage levels. This study addresses that gap by assessing how access to training, credit, and their combination affects PICS bag adoption intensity among maize farmers in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. Adoption intensity is defined as the proportion of maize stored using PICS bags, providing a more nuanced measure than binary indicators. To account for potential selection bias, we applied a Multivariate Inverse Probability Weighting (MIPW) estimator within a treatment effect framework, followed by a Tobit model to address the censored nature of the outcome variable (Manda et al., 2024). This approach allows us to estimate the causal impact of various intervention combinations—training only, credit only, both, or neither—on continuous adoption levels.

The study focuses on maize because it is a key staple crop and source of income for smallholder farmers in Tanzania. Moreover, it is widely cultivated, heavily stored, and particularly susceptible to postharvest losses. Since smallholder farmers primarily use PICS bags for maize storage, this crop provides the most relevant measure of adoption intensity. Focusing on maize also provided sufficient observations of PICS bag usage in the study area. Since the introduction of PICS technology, many maize farmers in the region have received training and gained access to both formal and informal credit sources. This provided an ideal context for evaluating the combined effects of these interventions.

This study contributes to the literature in two key ways. First, it introduces a novel methodological approach by combining MIPW with a Tobit model, which improves estimation by addressing both selection bias and outcome censoring. Second, it offers a substantive contribution by moving beyond binary adoption metrics. It explores how institutional support—specifically training and credit—interacts to influence the depth of technology adoption among smallholder farmers. The findings have important implications for the design of policies and programs aimed at improving food security and reducing postharvest losses through broader and more intensive adoption of hermetic storage technologies.

The PICS bag is a triple-layer hermetic storage system that preserves maize without chemicals (Murdock et al., 2012). Since its introduction, the PICS bag has gained popularity due to its effectiveness in preserving maize quality and quantity (Mlambo et al., 2017; Baributsa, 2024). PICS bags are favored over traditional storage methods as they require no chemicals, reducing health and environmental risks and preventing aflatoxin accumulation (Lane and Woloshuk, 2017; Dodds, 2020; Mutambuki and Likhayo, 2021). In addition, PICS bags reduce PHLs, increase farmers’ income (Adams et al., 2024), and minimize insect damage and weight loss (Dijkink et al., 2022; Odjo et al., 2022). With PICS bags, smallholder farmers can store their maize for extended periods, sell at higher prices, and improve food security (Alemu et al., 2021).

PICS bags have been widely disseminated across sub-Saharan Africa, including in Tanzania (Baributsa, 2024). Although adoption has increased, it varies by region, reaching 48% in Niger and 40% in Tanzania (Kotu et al., 2019; Rabé et al., 2021; Zacharia et al., 2024). Despite these gains, adoption remains below its potential due to limited awareness, unavailability in rural areas, high costs, and inadequate knowledge of proper usage (Moussa et al., 2014; Baributsa and Ignacio, 2020; Martey et al., 2023; Nakoma et al., 2025). Importantly, measuring adoption solely by the number of users provides an incomplete picture, as it overlooks differences in storage intensity. For example, suppose farmer A has 10 tons of maize and stores 1 ton in PICS bags, while farmer B has 1 ton of maize and stores the entire amount in PICS bags. Although both farmers store the same quantity, farmer A’s adoption intensity is 10%, while farmer B’s is 100%. This example underscores the importance of measuring adoption intensity, or the proportion of grain stored in hermetic bags, rather than simply the adoption rate, which counts the number of farmers using the technology.

The role of training in increasing maize storage in PICS bags is well-documented. Previous studies found that maize storage increased by 20% in Niger and 40% in Tanzania among PICS bag users, with training identified as a key driver of adoption (Moussa et al., 2014; Zacharia et al., 2024). Additionally, in Tanzania, providing loans to smallholder farmers increased the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags by 29% (Channa et al., 2022). To our knowledge, these are the only studies that specifically examine the effect of training or credit on maize storage in PICS bags. Building on this evidence, our study examines the effects of training and/or credit access on PICS bag adoption intensity. Using the MIPW method, we provide empirical insights into how these factors influence PICS bag adoption intensity among smallholder farmers in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. The following sections cover methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and sampling strategy

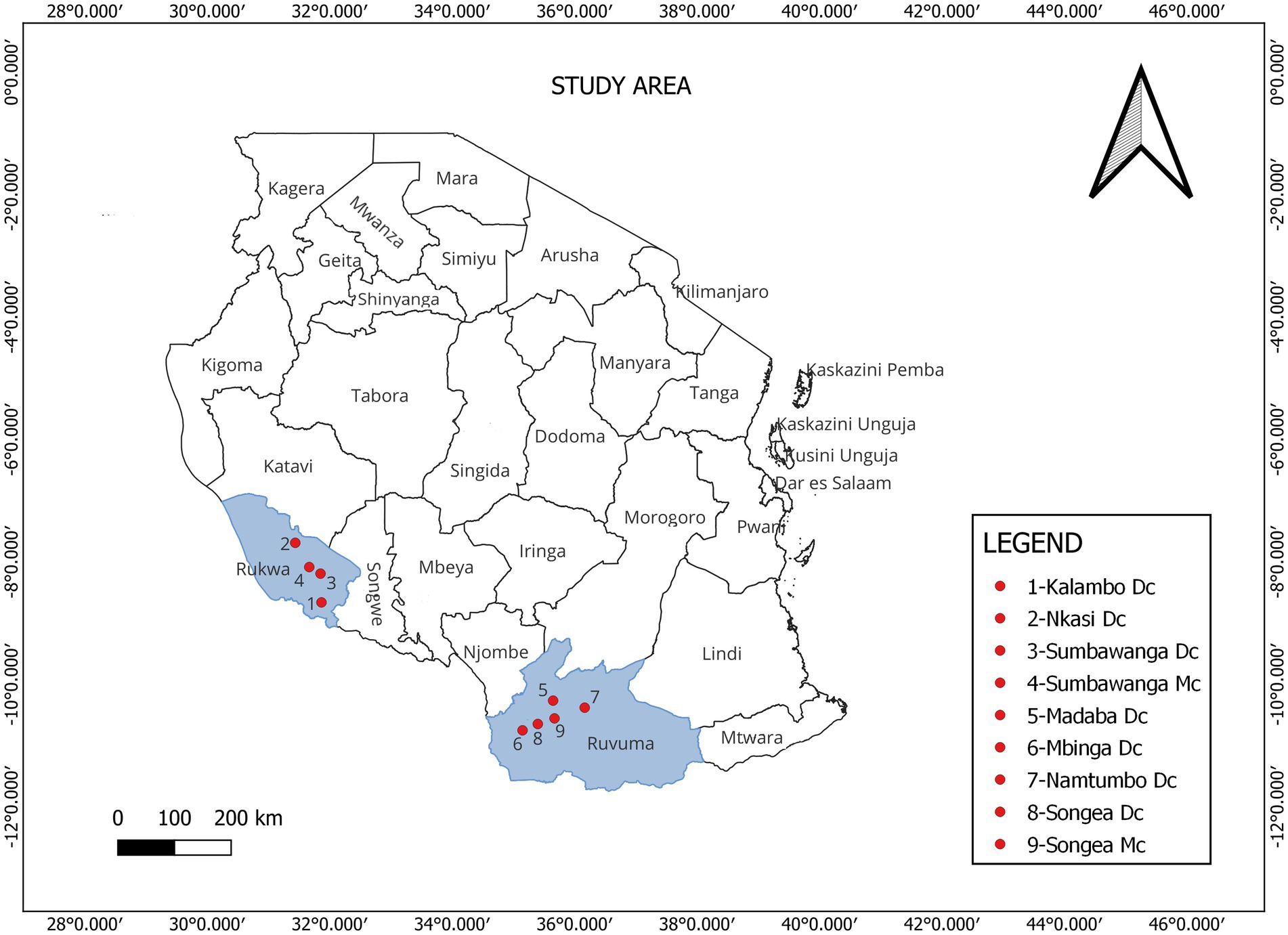

This study was conducted in the Rukwa and Ruvuma regions of Southern Tanzania in March 2024 (Figure 1). Each dot in Figure 1 represents a district where the study was implemented. The figure was created using QGIS 3.26.2, a free and open-source Geographic Information System (GIS) software used for mapping and spatial data analysis. In this study, QGIS was employed to visualize the study area by importing the current shapefile of Tanzania to display regional and district boundaries. The software allowed for accurate layering and customization of geographic features relevant to the research. The GPS coordinates used in the map were collected during fieldwork using the SurveyCTO Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) tool, which includes a built-in GPS locator. SurveyCTO, a digital data collection platform widely used in field research, facilitated the efficient and accurate capture of both survey responses and geographic location data. The coordinates were then added to the QGIS environment to mark the specific locations of the surveyed districts, resulting in a detailed and georeferenced map of the study area.

Figure 1. Study area in the Rukwa and Ruvuma regions of Tanzania. Each dot represents a district where the study was implemented.

The selection of Rukwa and Ruvuma regions was deliberate and based on their relevance to the study’s focus on maize storage. These regions are among the top maize producers in Tanzania. According to the 2019/2020 Tanzania Agriculture Census, Ruvuma ranked first with a production volume of 498,685 tons, followed by Rukwa with 338,988 tons (MOA, 2021). Since PICS bags are promoted for maize storage, these regions were considered ideal for capturing meaningful data on their adoption and use. Districts were selected based on the presence of well-organized producers’ organizations (POs) and their members’ willingness to participate in the study. The target population consisted of household members of POs and those in villages (non-PO members) in both regions, who were predominantly smallholder farmers. This aligns with the typical profile of maize producers in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The study used cross-sectional data to analyze the effect of access to training and credit on maize storage in PICS bags. Some households participated in a project that offered training on hermetic technologies to reduce storage losses and/or linked them to financial institutions for loan access.

Sampling was conducted in two stages. First, 60 eligible POs or villages (30 per region) were purposively selected with input from cooperative officers. In the second stage, 15 households per PO or village were randomly selected. To account for unequal probabilities of selection, sampling weights were applied in the analysis. These weights adjust for the fact that POs or villages may differ in size, ensuring that the resulting estimates are representative of the broader population. In addition, this approach helps control for institutional and geographical heterogeneity in the analysis, thereby enhancing the analytical balance and comparability of results across regions. Inclusion of sampling weights in regression analysis is widely recommended to correct for potential sampling bias. For example, Deaton (2019) emphasizes the importance of incorporating sampling weights when using survey data. Similarly, Winship and Radbill (1994) recommended using the appropriate weights in regression models. Solon et al. (2015) also provide a detailed discussion on when and how to use weights in regression analysis, emphasizing the importance of weights in achieving population-representative inferences.

Using sampling weights to correct for unequal sampling proportions is a common practice in health research. For example, a research by Mizinduko et al. (2020) who studied HIV prevalence and associated risks among female sex workers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, applied sampling weights to control for network size and clustering. Another study by Spittal et al. (2016) used sampling weights to adjust for varying population sizes across cities included in their survey. Following this approach, we calculated sampling weights as the inverse probability of selection from a PO or village, thereby correcting for differences in population size and ensuring representative results.

The household was the unit of analysis, reflecting decision-making practices in rural Tanzania. Surveys were administered to household heads rather than individuals, who are typically responsible for farm management and storage. When the household head was unavailable, the most knowledgeable adult involved in farming and storage decisions was interviewed as a proxy. While our target sample size was 900 households (15 per each of the 60 POs or villages), the final usable sample consisted of 908 households. The inclusion of 8 additional households was a precautionary measure to safeguard against possible non-responses, refusals, or data loss during the cleaning process. During the analysis, we conducted robustness checks to assess the impact of including the additional 8 households by re-estimating our models using alternative samples. In both scenarios, households were randomly excluded from POs or villages where the extra sampling had taken place. The distribution of households across treatment groups remained consistent, and the estimated treatment effects showed minimal variation in both magnitude and statistical significance. The results confirm that our findings are robust to the inclusion or exclusion of the additional households.

The data were collected using an interview guide administered by trained and experienced enumerators who speak the local language and are familiar with the maize farming system. To ensure a logical flow and consistency, the interview guide was coded in SurveyCTO and pretested with a small sample of households from nearby villages with characteristics similar to the study areas. It gathered information on household types or “treatment”—variables (training and/or credit access), the outcome variable (proportion of maize stored in PICS bags), and household, farm, demographic, and institutional characteristics.

Households were categorized into four groups based on farmers’ choices rather than through a controlled (randomized) assignment. Classification was based on respondents’ self-reported answers to two key survey questions: (1) “Did you receive formal training on postharvest management?” and (2) “Did you receive credit for agriculture in the previous season (year before the survey)?” Based on responses to these questions, households were categorized into the following four groups: T0C0—those who received no training or credit, T1C0—those who received only training, T0C1—those who received only credit, and T1C1—those who received both training and credit.

2.2 Theoretical framework

This paper applies the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF), developed by DFID (1999), to explore how access to training and credit, as key institutional interventions, impacts the adoption intensity of the PICS bag. The SLF provides a comprehensive theoretical foundation for examining the multidimensional factors influencing the adoption intensity of agricultural innovations such as PICS among smallholder farmers. Within a broader vulnerability context and institutional environment, the SLF suggests that rural livelihoods are shaped by the interaction of five types of capital assets, which are human, financial, physical, natural, and social.

While the SLF provides a valuable lens for understanding livelihood dynamics, this study also draws on the capacity-building framework proposed by Lartey and Glaser (2024) to enrich the theoretical interpretation of training, credit, and institutional engagement in the PICS environment. In this context, capacity building refers to the process of strengthening the abilities of individuals, organizations, and systems to perform their functions, solve problems, and achieve sustainable outcomes. The framework identifies four interrelated levels of capacity building—individual, organizational, institutional, and environmental—that collectively determine the effectiveness and sustainability of technology adoption interventions.

At the individual level, capacity building focuses on enhancing farmers’ knowledge, skills, and decision-making competencies. Training represents a key investment in human capital, as it improves farmers’ technical understanding and cognitive capacity for effective postharvest management. Using PICS bags effectively requires proper grain drying, correct sealing, and good storage hygiene. Training enables farmers not only to become aware of these practices but also to internalize their value, translating knowledge into improved postharvest behaviors. This progression—from awareness to behavioral change—supports more consistent and sustained use of the technology, rather than one-time adoption. Moreover, trained farmers often act as informal trainers within their communities, facilitating horizontal knowledge transfer and collective learning. In this way, individual capacity building extends into the social sphere, reinforcing community-level knowledge and skills. Capacity building extends beyond individual skill acquisition to include organizational and institutional strengthening (Pearson, 2011).

At the organizational level, capacity building involves reinforcing local structures that support technology dissemination and service delivery. Farmers’ groups, cooperatives, and community-based organizations play critical roles in coordinating training, managing bulk purchases of PICS bags, and serving as local distribution channels. Organizational capacity influences the efficiency of training delivery and the administration of credit schemes. Well-organized farmers’ groups, for instance, can negotiate better access to credit or establish vendor partnerships, thereby fostering economies of scale and greater trust in technology distribution system. Such organizational strengthening complements the human and financial capital dimensions of the SLF by institutionalizing support systems that sustain adoption beyond individual efforts.

At the institutional level, capacity building addresses the enabling systems—such as public extension services, private sector actors, NGOs, and community organizations—that shape the rules, incentives, and coordination mechanisms governing technology adoption. Access to credit is a critical element, as it directly enhances financial capital and mitigates one of the main barriers to PICS technology adoption among resource-constrained smallholders. Although PICS bags generate long-term savings by reducing losses and eliminating the need for chemical use, their initial cost can be prohibitive for some farmers. Credit access relaxes these financial constraints, enabling farmers to purchase multiple bags and potentially invest in complementary technologies such as elevated platforms or improved storage facilities. The integration of vendors, training institutions, and financial service providers reflects institutional capacity building, as these actors collectively establish reliable value chains and supportive infrastructure. Importantly, the interaction between financial and human capital is synergistic; farmers with access to both training and credit are more likely to make informed and financially viable decisions regarding the use of technology.

At the environmental (or systemic) level, capacity building pertains to the broader policy, market, and socioeconomic context that shapes the long-term sustainability of technological innovations. Natural capital, particularly landholding size and grain production volume, determines the scale of storage need and, consequently, the demand for PICS bags. Physical capital, including storage facilities and transportation infrastructure, affects the feasibility of hermetic storage. Social capital, expressed through participation in farmers’ groups, cooperatives, or informal networks, facilitates information sharing, credit access, and trust in new technologies. Coordinating these elements requires a supportive policy environment that promotes public–private partnerships and integrates PICS technologies into national extension systems. Strengthening systemic capacity at this level ensures that adoption is not only widespread but also resilient to market and institutional disruptions.

Integrating the capacity-building framework within the SLF provides a more holistic understanding of how different dimensions of capacity interact to influence adoption intensity. The SLF emphasizes the role of assets and institutions in shaping livelihood outcomes, while the capacity-building approach highlights the dynamic processes through which these assets and institutions are strengthened, aligned, and mobilized for sustainable change. Together, they demonstrate that the adoption intensity of PICS bags among smallholder maize farmers is not merely a function of access to training or credit, but rather a reflection of how these interventions build capacity across individual, organizational, institutional, and systemic levels.

From a policy perspective, this integrated view underscores that capacity building should be treated as a deliberate, multilevel strategy within public programs promoting postharvest technologies—such as Tanzania’s National Postharvest Management Strategy (2019–2029). Embedding training, credit, and vendor participation within a structured capacity-building approach can enhance both the effectiveness and sustainability of PICS adoption initiatives.

2.3 Empirical model

Households with access to training and credit may differ systematically, as those seeking training might have decided to do so because they are more educated and motivated to seek knowledge (Wonde et al., 2023). Failing to account for these differences may lead to biased estimates. The treatment variable has four levels: no training or credit, training only, credit only, and both training and credit. We apply the MIPW with a Tobit model to address the selection bias, thus ensuring the validity of the effect estimates. The choice of the MIPW approach, followed by a Tobit model, was guided by the specific characteristics of our data, namely, a treatment variable with four levels and a left-censored outcome variable (Smale et al., 2018; Manda et al., 2021). Applying the Tobit model also enables the inclusion of non-users in the analysis, which help maintain the integrity and representativeness of the sample.

We estimate the effects of access to training and/or credit on the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags using a three-step MIPW. First, we estimate the parameters of the propensity score model using the multinomial logit model. The propensity score approach handles non-random treatment assignment and multilevel treatment variables (Smale et al., 2018; Manda et al., 2021). We then calculate the Inverse Probability Weights (IPW) for each treatment level. The propensity score—the probability of accessing training and/or credit given observed characteristics ( )—is denoted in Equation (1):

Where denotes the status of a household having access to neither training nor credit, training only, credit only, or both (training and credit), i.e., .

In the second step, we use the Tobit model for each treatment level to identify factors influencing the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags at that level, while adjusting for left censoring. The censoring arises due to limitations in measuring the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags for non-users. This censoring indicates that non-users have no observed maize stored in PICS bags, rather than being related to the treatment itself (training only, credit only, or both). In addition, the IPW is incorporated into the Tobit model for each treatment level to weight the maximum likelihood estimator.

In the final step, we computed treatment-specific predicted mean outcomes of the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags. The average treatment effects (ATE) are computed as the differences in these outcomes using Equation (2):

Where represents the potential outcome (proportion of maize stored in PICS bags) for a household that has accessed either training, credit, or both and denotes the outcome for the control category (no access to training and credit). We obtain the Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT) by restricting the analysis to households that received training and credit.

The ATT can be defined using Equation (3):

Three treatment levels are required for the ATT: represents the potential outcome of the treated; the potential outcome of the control is denoted by 0, and denotes the outcome restricted for individuals who received the treatment only . Identifying the treatment effects relies on three assumptions: (i) conditional independence (CI), ensuring that observed covariates account for confounding factors, (ii) sufficient overlap, meaning all households have a probability of receiving any treatment level, and (iii) correct model specification, ensuring appropriate adjustment for left censoring. The overlap assumption is tested using density distributions to determine whether balancing has been achieved.

A Tobit regression model handles censored outcomes, such as the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags, which is only observed when a household adopts the PICS bag technology. Unlike standard linear regression, which assumes a continuous and uncensored outcome, the Tobit model appropriately accounts for partially observed or limited outcomes. Applying standard regression to censored outcome data will produce biased parameter estimates since it cannot fully account for the missing information on the outcome variable. While the MIPW-Tobit approach used in this study helps mitigate bias from observed confounding effects and accounts for censoring in the outcome variable, it does not fully eliminate the potential bias arising from unobserved heterogeneity. Factors such as farmers’ risk preferences, motivation, or unmeasured access to networks may influence both the decision to access training and/or credit and the intensity of PICS bag adoption. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted as associational rather than strictly causal, given the observational nature of the data. This limitation underscores the need for future research to validate these findings using experimental designs that can better account for endogeneity arising from unobserved factors.

The joint analysis of training and credit in this study is conceptually grounded in the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (DFID, 1999), which emphasizes that access to multiple forms of capital, particularly human capital (e.g., training) and financial capital (e.g., credit) is essential for enabling sustainable livelihood outcomes. In the context of PICS bag adoption, training enhances farmers’ knowledge and awareness of storage technology, while credit eases liquidity constraints and boosts risk-bearing ability in using the technology. The synergistic effect of training and credit on the intensity of technology adoption stems from the financial management skills, insights, and knowledge acquired through training, which allows them to use their credit efficiently, leading to optimized adoption outcomes. As such, these two forms of capital are complementary, not merely additive: training without credit may increase awareness without the means to act, while credit without training may lead to misuse or underutilization of the technology. This conceptual relationship is supported by empirical studies that demonstrate how bundled interventions improve adoption outcomes. For example, Feder et al. (1985) highlight the importance of combining extension with financial support; Kassie et al. (2013) show that adoption of sustainable agricultural practices is significantly enhanced when farmers have access to both knowledge and capital; and Addison et al. (2016) find that access to credit reinforces the effects of training among women adopters of improved rice technologies.

The selection of explanatory variables in our model was informed by existing literature on the adoption intensity of agricultural technologies (Table 1). Household characteristics such as age, gender, education level of the household head, and household size are commonly associated with adoption behavior (Wasiu and Adebayo, 2015; Beshir et al., 2022). Several studies have shown that older household heads are less likely to adopt technologies intensively, possibly due to risk aversion or lower adaptability (Acheampong et al., 2021; Chigeto and Angelo, 2021). Household size, which reflects the availability of labor, is generally associated with higher adoption intensity. A larger plot size increases the likelihood of surplus production, thereby raising the demand for improved storage solutions, such as PICS bags. Similarly, livestock ownership enhances economic capacity, making it easier for households to afford multiple storage bags (Bekele et al., 2024).

Institutional factors, such as membership in farmer saving groups (e.g., VICOBA), promote adoption through collective action and social learning (Ghimire et al., 2015). Access to information, facilitated by tools like radio, cellphones, and television, also plays a role in technology uptake (Moussa, 2009; Muriuki et al., 2016; Milkias, 2020; Baributsa, 2022). The use of recommended agricultural inputs—such as improved seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides—can lead to higher yields, thereby increasing the need for effective postharvest storage solutions. Financial indicators, such as bank account ownership or cash savings, reflect the ability to invest in technologies like PICS bags.

Awareness of aflatoxins is another important driver, as concerns about food safety often motivate the adoption of safer storage practices (Udomkun et al., 2018). Availability of PICS bag vendors enhances adoption intensity by ensuring easy access and reducing transaction costs (Moussa et al., 2014; Omotilewa and Baributsa, 2022). Finally, ownership of transport assets (i.e., bicycles and motorcycles) can minimize travel time and costs, improving farmers’ access to markets, training, and input suppliers—including PICS bag vendors—which may further influence adoption decisions (Matous et al., 2015).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the four treatment groups. Nearly half of the households had no access to either training or credit, while about one-third had access to only one of the two. Notably, only 7% of households accessed both training and credit, highlighting a significant imbalance in the distribution of treatment groups. To address this imbalance and reduce potential estimation bias, we applied Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) using multinomial propensity scores. The distribution of the treatment groups before and after weighting is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. The chart illustrates that IPW substantially improved balance across the four treatment groups, supporting the validity of our estimation strategy by mitigating the effects of unequal group sizes.

Table 2. Credit and/or training access among 908 households (HH) surveyed in the Rukwa and Ruvuma regions of Tanzania in 2024.

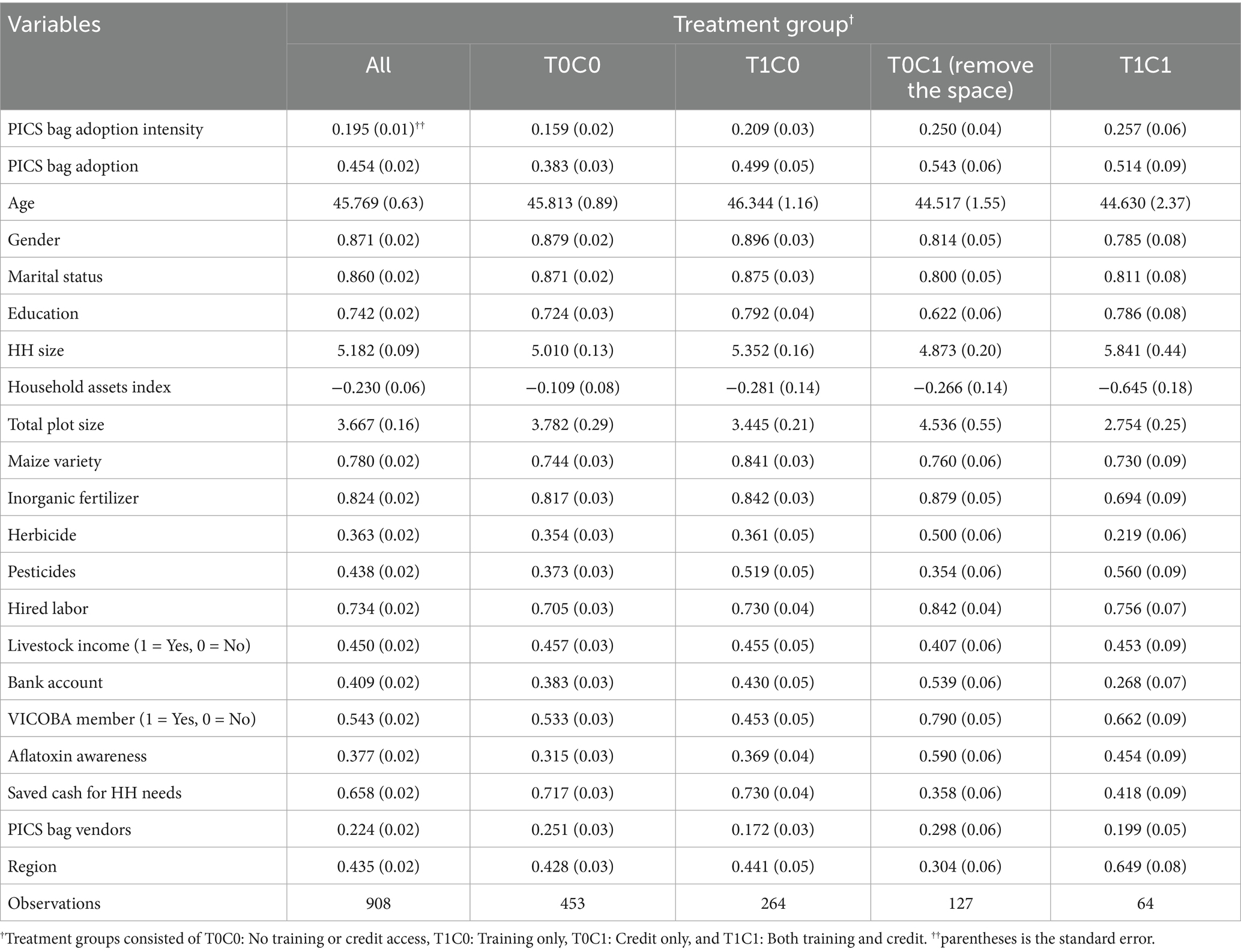

Table 3 provides summary statistics by treatment groups. The results indicate that households without training or credit had the lowest proportion of maize stored in PICS bags. Households with access to training only or credit only had 20.9 and 25% of their maize stored in PICS bags, respectively. In contrast, those with both interventions stored higher proportions in hermetic bags, averaging 25.7%. The adoption rate of PICS bags among households was 45.4%. On average, 87.1% of households were male-headed, 86.0% were married, and 74.2% had completed primary education. Households had an average of 5 members and farmed 3.67 acres. Most households used improved maize varieties (78%) and inorganic fertilizer (82.4%), while the use of herbicides and pesticides was relatively low at 36.3 and 43.8%, respectively. Additionally, 73.4% of households relied on hired labor. Overall, asset ownership by the surveyed households was relatively low.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of 908 households (HH) surveyed in the Rukwa and Ruvuma regions of Tanzania in 2024.

Regarding financial access, 45% of households earned income from livestock, 40.9% had a bank account, and 54.3% were members of Village Community Banks (VICOBA). Aflatoxin awareness was 37.7%, the highest among those with access to credit only. While 65.8% of households reported having sufficient cash savings, this was the lowest among those who had access to credit. Only 22.4% of households had access to PICS bag vendors, with the highest percentage among those who received credit only.

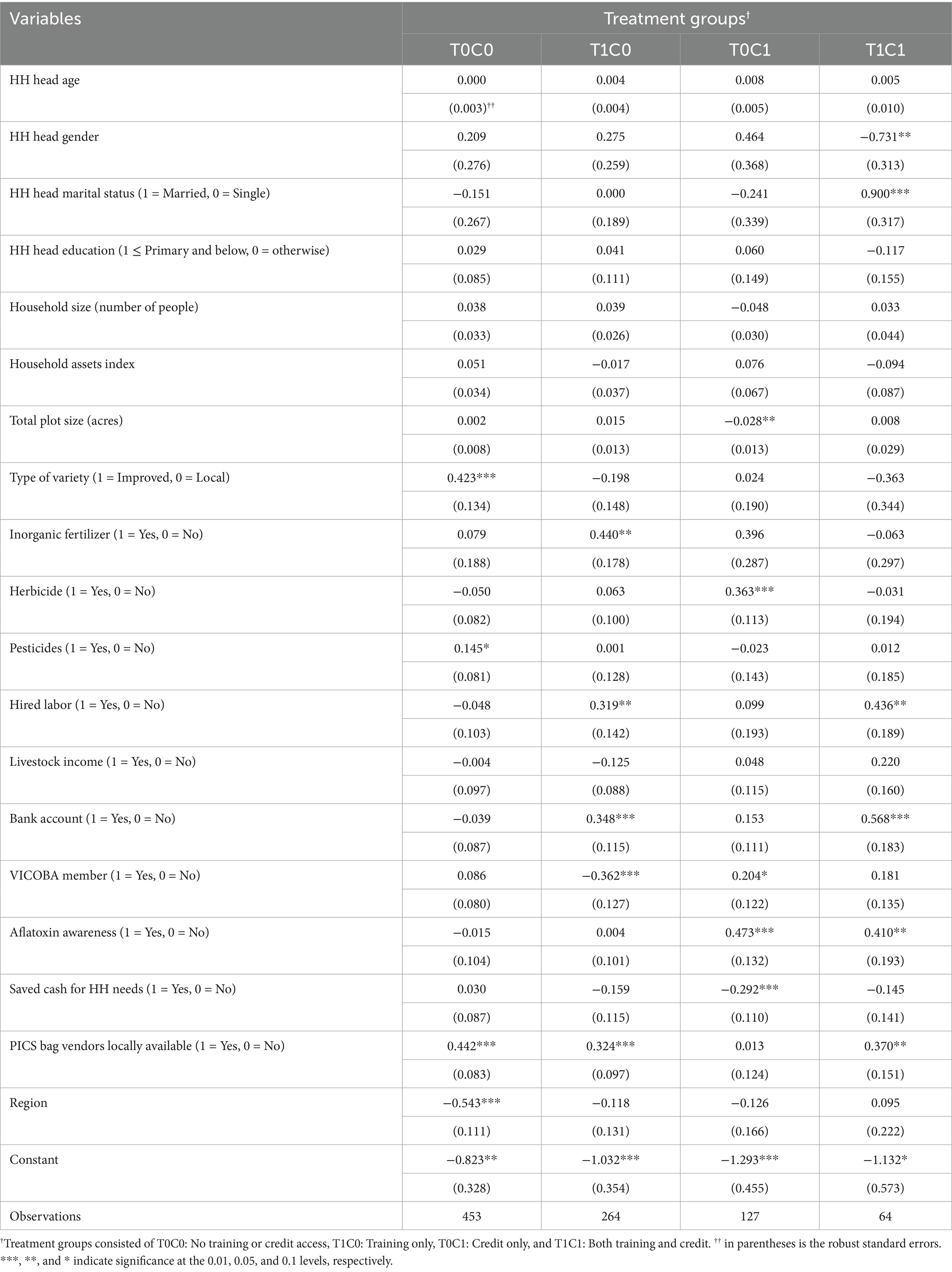

3.2 Determinants of the PICS bag adoption intensity

Table 4 presents the second-stage Tobit model estimates, while Supplementary Table S1 shows the first-stage multinomial logit results. The Tobit model results are valid when derived from observationally similar groups after propensity score reweighting. As shown in Figure 2, the overlap assumption holds after propensity score reweighting, confirming the appropriateness of the Tobit model for effect estimation. In addition, the model was correctly specified, with no evidence of multicollinearity, as the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values calculated using an OLS regression with the same set of independent variables were all below 5 across the different model specifications (no training or credit, training only, credit only, and both training and credit). We also assessed the potential risk of overfitting by comparing model fit across specifications with and without the binary variables. The full models that included the binary variables consistently exhibited higher pseudo-R2 values, indicating better explanatory power, and lower log-pseudolikelihood values, suggesting an improved model fit.

Table 4. Determinants of the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags among 908 households (HH) surveyed in the Rukwa and Ruvuma regions of Tanzania in 2024.

Figure 2. Balanced plots for the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags based on treatment groups consisted of no training or credit access, training only, credit only, and training and credit.

Since this study focuses on the effects of the explanatory variables and treatment groups on the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags, we do not interpret the first-stage results. Instead, we analyze the findings separately for the four groups: no training or credit, training only, credit only, and both (training and credit).

Table 4 shows the factors influencing the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags. Households without training or credit tend to store a higher proportion of maize in PICS bags if they use improved maize varieties, apply pesticides on their maize farms, and have access to PICS bag vendors. Among those with training only, the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags increases for households that use inorganic fertilizers, utilize hired labor, have bank accounts, and have vendor access. At the same time, VICOBA membership reduces it. For credit-only households, the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags rises with herbicide use, VICOBA membership, and aflatoxin awareness, but declines as plot size increases and sufficient savings. For households with training and credit, the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags increases when the household head is female and married, the household utilizes hired labor, has a bank account, is aware of aflatoxins, and has access to a PICS bag vendor.

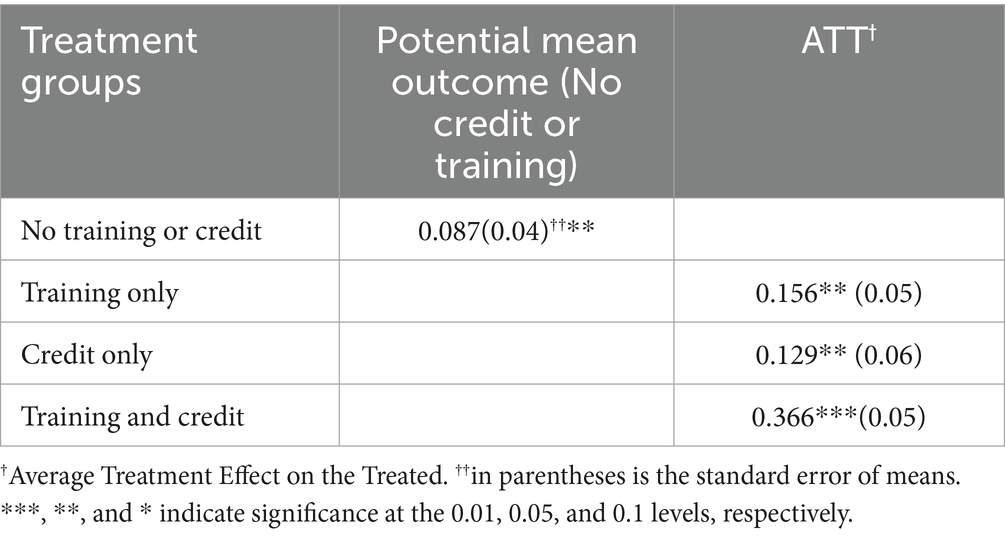

3.3 Effects of training and credit on adoption intensity

Table 5 shows the effects of access to training, credit, or both on the household’s proportion of maize stored in PICS bags, measured as the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT). If a household did not access training or credit, which serves as the baseline, the average proportion of maize stored in PICS bags was 8.7 percentage points. However, if a household accessed training only, the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags would increase by 15.6 percentage points compared to the baseline. If a household accessed credit only, the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags would also increase by 12.9 percentage points relative to the baseline. The joint effect of training and credit resulted in the largest increase, raising the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags by 36.6 percentage points over the baseline.

Table 5. Effects of training and credit on PICS bags adoption intensity among 908 households (HH) surveyed in both Rukwa and Ruvuma in 2024.

3.4 OLS and fractional logit effects estimation results

To assess the robustness of the MIPW-Tobit model results, we estimated Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Fractional Logit models, as presented in Table 6. For conciseness, we focus on the treatment variables. The OLS results show that access to training and credit increases PICS bag adoption intensity by only 0.045 and 0.024, respectively, but neither estimate is statistically significant. In contrast, access to both training and credit increases it by 0.105, which is statistically significant. The final two columns of Table 6 report the coefficients and marginal effects from the fractional logit model. We interpret the results using the marginal effects. The marginal effect for training is 0.056, statistically significant, indicating that households with access to training have an adoption intensity that is 5.6 percentage points higher than those without. Similarly, households with access to both training and credit show an increase of 13.4 percentage points in adoption intensity compared to those without access. Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by estimating parsimonious versions of the OLS and fractional logit models, excluding control variables. These results in Supplementary Table S2 are consistent with those in Table 6, further supporting the robustness of our findings and suggesting that selection bias is unlikely to be a major concern.

4 Discussion

This study examined the impact of training and credit on the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags among smallholder farmers in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. Among households without training or credit, those using improved maize varieties and pesticides, as well as those with access to local PICS bag vendors, stored more maize in PICS bags. This suggests that households using improved seeds and pesticides were more likely to store larger quantities of maize in hermetic bags. Previous research showed that PICS bag users were 10 percentage points more likely to use improved seeds in the following season (Omotilewa et al., 2018). This use of PICS bags may be driven by the higher susceptibility of improved seeds to pests during storage (Ricker-Gilbert and Jones, 2015). Access to PICS bag vendors is a critical factor influencing adoption intensity. Vendors located in or near local communities eliminate transportation barriers and reduce the time and cost of acquiring PICS bags (Omotilewa and Baributsa, 2022). Their presence in villages ensures a steady supply of hermetic storage technologies (HSTs); underscoring the importance of an effective supply chain for adoption (Dodds, 2020).

Among households that received training only, adoption intensity increased with the use of inorganic fertilizers, hired labor, bank account ownership, and access to PICS vendors. This finding suggests that training enhances farmers’ capacity to apply knowledge of improved postharvest practices, reflecting its role in individual-level capacity building. Access to PICS vendors complements this process by strengthening supply-side capacity and ensuring that farmers can translate acquired knowledge into actual adoption decisions. Beyond the individual level, vendor participation contributes to organizational capacity building by improving local distribution systems, fostering business networks, and enhancing the responsiveness of the supply chain to farmers’ needs. Vendors serve as key intermediaries who not only supply PICS bags but also facilitate institutional learning by sharing product knowledge, providing demonstrations, and maintaining regular engagement with farmers. The interaction between training and vendor access underscores the importance of linking knowledge transfer with market availability. Together, these elements strengthen the institutional infrastructure necessary for sustained technology diffusion. This integrated approach fosters a more resilient and adaptive market system in which trained farmers are supported by capable organizations that can reliably supply, promote, and sustain the use of improved storage technologies.

In addition, commercially oriented farmers who use productivity-enhancing technologies, such as inorganic fertilizers, are more likely to store larger quantities of maize in PICS bags. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that input-using households are more likely to adopt improved storage technologies, thereby increasing their storage intensity and enhancing food security (Omotilewa et al., 2018; Zacharia et al., 2024). The negative relationship between VICOBA membership and PICS bag adoption in the training-only group may reflect competing financial priorities. Although VICOBA membership offers financial benefits and promotes inclusion (Frisancho and Valdivia, 2020; Mponzi et al., 2023), the obligation to make regular contributions may limit time for training and reduce liquidity for investments such as PICS bags. This is consistent with evidence that savings obligations can limit technology adoption among resource-constrained households (Carter et al., 2016).

Although access to credit alone is associated with an increase in the use of hermetic bags, its impact varies depending on household characteristics and resource constraints. Some households allocated credit to immediate production costs, while others expanded their storage capacity. Households using herbicides and those with VICOBA membership were more likely to benefit from credit, as these complementary resources maximized its effectiveness for storage investments. These findings underscore the need for targeted policy interventions that address specific household barriers, as credit is most effective when paired with access to input markets and productive assets.

Beyond financial constraints, aflatoxin awareness also plays a key role in maize storage decisions, particularly among households with access to training or credit. Training not only increases farmers’ understanding of aflatoxin-related health risks but also strengthens their technical capacity to identify, prevent, and manage contamination through improved storage practices. This capacity building enhances farmers’ confidence and motivation to invest in PICS bags to ensure food safety and protect household health (Udomkun et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2018). Similarly, access to credit is more likely to enhance financial flexibility for storage investments, especially for households already aware of aflatoxin risks, even without formal training.

Gender and marital status significantly influenced PICS bag adoption intensity among households with access to both training and credit. Married female-headed households exhibited higher adoption rates than unmarried male-headed households. This pattern reflects the complementary nature of these interventions: training enhances awareness and technical knowledge, while credit relaxes liquidity constraints, enabling households to act on knowledge gained. Female-headed households often prioritize food security and postharvest loss reduction, making them particularly responsive to technologies that ensure grain safety and income stability (Doss, 2001; Moussa et al., 2014; Moussa, 2009; Ragasa et al., 2013; Ibro et al., 2014; Swamy, 2014). Credit access empowers women to make independent financial decisions and invest in productive technologies (Swamy, 2014). When combined with training, this empowerment effect is further reinforced (Kassie et al., 2014; Gartaula et al., 2025).

Beyond these household characteristics, social and cultural dynamics such as intra-household bargaining, labor allocation norms, peer influence, and community-level expectations likely shape adoption decisions in significant ways. Intra-household bargaining influences technology adoption by affecting how resources are negotiated and household needs are prioritized (Miura et al., 2020; Shibata et al., 2020), while social capital and community networks facilitate access to information and uptake of innovations (Ntume et al., 2015; Crudeli et al., 2022). Community norms and expectations also shape farmers’ perceptions of acceptable practices, reinforcing adoption behaviors (Ninsiima et al., 2025). Collectively, these dynamics underscore that both household characteristics and broader socio-cultural factors are key determinants of PICS bag adoption.

Although descriptive statistics show a modest increase in the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags (25.7%) with training and credit, the ATT estimates reveal a stronger effect. Households receiving both interventions stored 36.6% more maize in PICS bags than those with neither, demonstrating a strong synergistic effect. While each intervention individually increases maize storage in PICS bags, their combined effect is significantly greater. This finding suggests that financial support alone is insufficient without the accompanying knowledge and skills imparted through training. Training serves as a critical capacity-building mechanism, enhancing farmers’ technical understanding, confidence, and ability to correctly use improved storage technologies. Conversely, training without access to finance may limit adoption if farmers lack resources to act on acquired knowledge (Harou et al., 2022). Consistent with previous studies, farmers are more likely to adopt and sustain innovations when they receive both training and financial support (Musara et al., 2010; Dhehibi et al., 2018; Dhehibi et al., 2022; Adhikari et al., 2024). Our results reinforce the theoretical proposition of the SLF that access to multiple, complementary livelihood capitals is necessary for technology adoption and sustainable behavior change (Feder et al., 1985; Kassie et al., 2013; Addison et al., 2016).

Access to finance is crucial for increasing maize storage in PICS bags, as financial constraints hinder investment in improved storage technologies. Farmers face challenges obtaining loans due to high borrowing costs, limited access to financial institutions, lengthy loan processing times, and strict collateral requirements (Balana et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024). Policies that promote financial inclusion, lower interest rates, and streamline loan application processes can improve credit access and increase PICS bag adoption. Credit may be accessed through both formal and informal channels, such as banks and savings groups, which provide liquidity to smallholder farmers.

Beyond traditional credit, subsidies can enhance maize storage in PICS bags, especially when combined with training. A study in Tanzania found that well-targeted financial interventions led to a 29% increase in maize storage in PICS bags (Channa et al., 2022). Development programs should integrate training with access to finance or subsidies to maximize the adoption of hermetic storage technologies. Smart input subsidies can mitigate financial risks and information gaps among farmers. They can accelerate the adoption of high-productivity technologies while avoiding market distortions and fostering innovation in the hermetic supply chain (George, 2011; Amaglobeli et al., 2024).

5 Conclusion

This study examined the impact of training and/or credit on PICS bag adoption intensity (i.e., the proportion of maize stored in PICS bags) among smallholder farmers in the Ruvuma and Rukwa regions of the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Households with access to training or credit stored more maize in PICS bags than those without, whereas those with both interventions stored significantly higher proportions, indicating a strong synergistic effect. These findings suggest that although training or credit alone can enhance maize storage, their combination generates greater and more sustained adoption by simultaneously building capacity at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels. Regression results further support this relationship: as farmers strengthen their storage capacity, they tend to purchase more PICS bags in subsequent seasons, thereby reinforcing adoption.

Policy interventions should prioritize integrating technical training with financial services to strengthen farmers’ ability to adopt and sustain the use of improved storage technologies. Expanding access to affordable credit and savings can help smallholders overcome liquidity constraints while reinforcing organizational capacity through stronger vendor networks and service delivery systems. To ensure efficiency and long-term sustainability, scaling such interventions should be guided by detailed cost and impact analyses covering training delivery, vendor expansion, and credit facilitation. A coordinated approach will help in designing interventions that simultaneously build farmers’ skills, institutional linkages, and market infrastructure, ensuring widespread PICS bag adoption.

Providing subsidies—either directly to smallholder farmers or indirectly through supply chain actors—can further improve access to PICS bags. Strengthening rural distribution networks is particularly important to reduce transportation costs, minimize delays, and ensure consistent product availability during peak demand periods. The proximity of vendors to farming communities not only lowers access barriers but also supports regular use of hermetic storage technologies. Additionally, bundling PICS bags with complementary inputs such as improved seeds can create synergies that boost productivity, reduce postharvest losses, and improve household food security. Addressing supply chain constraints alongside training and credit access is therefore essential to achieving long-term, scalable adoption.

Integrating these insights into Tanzania’s National Postharvest Management Strategy (2019–2029) could enhance program effectiveness by aligning farmers’ capacity financial access, and input availability. Strengthening coordination among training, credit, and vendor systems would build resilience and long-term adaptability across the postharvest sector. Methodologically, this study’s approach—combining propensity score reweighting, selection bias correction, and censoring adjustments—provides a useful reference for future research on technology adoption using censored outcomes in quasi-experimental contexts. Nonetheless, its observational design leaves room for unobserved confounding. Future research should employ experimental designs to validate these findings and strengthen causal inference.

This study relied on a cross-sectional dataset with treatment groups based on self-reported access to training and credit facilities. Only a small proportion of households (7%) had access to both services, limiting the statistical power of interaction estimates. The study design also precluded independent verification of service quality and measurement of potential spillover effects. Although sample weights and rigorous estimation procedures were applied, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal inference. Future research should employ randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to strengthen causal identification and assess social diffusion effects more accurately. Incorporating spatial or network-based approaches would further enable researchers to capture geographic and social linkages among households, providing deeper insights into how training and credit interventions spread within communities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by IITA Review Board of IITA, based in Nigeria. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MN: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by USAID (Award no. 720BHA21CA00012) through Purdue University under the program “Expanding Credit Access to Scale up the Use of Hermetic Storage in Tanzania (CASH-Tz).”

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the rural urban development initiative (RUDI) and building rural incomes through entrepreneurship (BRiTEN) for their support in accessing maize producers’ organizations. We also appreciate the district and local extension officers for coordinating the meetings with sampled farmers in the Ruvuma and Rukwa regions.

Conflict of interest

DB was a co-founder of PICS Global Inc., a company that commercializes PICS bags around the world.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI was used to improve flow, clarity and check grammar errors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1677385/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | Sample distribution by treatment (Unweighted vs Weighted).

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S1 | Determinants of training and credit among 908 households (HH) surveyed in both Rukwa and Ruvuma in 2024.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S2 | Estimation results using OLS and fractional logit models without explanatory variables.

References

Abass, A. B., Fischler, M., Schneider, K., Daudi, S., Gaspar, A., Rüst, J., et al. (2018). On-farm comparison of different postharvest storage technologies in a maize farming system of Tanzania central corridor. J. Stored Prod. Res. 77, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2018.03.002

Abass, A. B., Ndunguru, G., Mamiro, P., Alenkhe, B., Mlingi, N., and Bekunda, M. (2014). Post-harvest food losses in a maize-based farming system of semi-arid savannah area of Tanzania. J. Stored Prod. Res. 57, 49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2013.12.004

Abate, T. W. (2024). Analysis of agricultural technology adoption: the use of improved maize seeds and its determinants in Ethiopia, evidence from eastern Amhara. J. Innov. Entrepren. 13:61. doi: 10.1186/s13731-024-00421-4

Acheampong, E. O., Sayer, J., Macgregor, C. J., and Sloan, S. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of agricultural practices in Ghana’s forest-fringe communities. Land 10:266. doi: 10.3390/land10030266

Adams, F., Donkor, E., Quaye, J., Jantuah, A. A., and Etuah, S. (2024). Sustainable maize storage technology adoption in Ghana: implications for postharvest losses, farm income, and income inequality. Food Energy Secur. 13:70011. doi: 10.1002/fes3.70011

Addison, M., Ohene-Yankyera, K., and Fredua-Antoh, E. (2016). Gender role, input use and technical efficiency among rice farmers at Ahafo Ano North District in Ashanti region of Ghana. J. Food Secur. 4, 27–35. doi: 10.12691/jfs-4-2-1

Adhikari, S. P., Timsina, K. P., Rola-Rubzen, M. F., Timsina, J., Brown, P. R., Ghimire, Y. N., et al. (2024). Determinants of conservation agriculture-based sustainable intensification technology adoption in smallholder farming systems: empirical evidence from Nepal. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 118, 31–50. doi: 10.36253/jaeid-14682

Alemu, G. T., Nigussie, Z., Haregeweyn, N., Berhanie, Z., Wondimagegnehu, B. A., Ayalew, Z., et al. (2021). Cost-benefit analysis of on-farm grain storage hermetic bags among small-scale maize growers in northwestern Ethiopia. Crop Prot. 143:105478. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105478,

Amaglobeli, D., Benson, T., and Mogues, T. (2024). Agricultural producer subsidies, International Monetary Fund notes. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

AUC (2014). Malabo declaration on accelerated agricultural growth, Malabo declaration on accelerated agricultural growth. Malabo: Equatorial Guiniea.

Balana, B. B., Mekonnen, D., Haile, B., Hagos, F., Yimam, S., and Ringler, C. (2022). Demand and supply constraints of credit in smallholder farming: evidence from Ethiopia and Tanzania. World Dev. 159:106033. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106033

Baributsa, D. (2022). Potential of Bluetooth wireless technology as a tool for agricultural extension. J. Agric. Sci. 14:28. doi: 10.5539/jas.v14n12p28

Baributsa, D. (2024). “Commercialization of hermetic bags in sub-Saharan Africa: the PICS experience” in Imagining African Agrifood systems: Looking forward. eds. M. W. Gitau, et al. (St. Joseph, MI: American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers), 14–24.

Baributsa, D., and Ignacio, M. C. C. (2020). “Developments in the use of hermetic bags for grain storage” in Advances in postharvest management of cereals and grains. ed. D. E. Maier (Cambridge, UK: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing), 171–198.

Bekele, E., Abera, G., and Temesgen, H. (2024). Factors influencing adoption and intensity of agroforestry systems for mitigating land degradation (MLD) in Gilgel gibe I catchment, southwestern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 10:782. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2024.2380782

Beshir, M., Tadesse, M., Yimer, F., and Brüggemann, N. (2022). Factors affecting adoption and intensity of use of Tef-Acacia decurrens-charcoal production agroforestry system in northwestern Ethiopia. Sustainability 14:4751. doi: 10.3390/su14084751

Carter, M. R., Laajaj, R., and Yang, D. (2016). Savings, subsidies, and sustainable technology adoption: Field experimental evidence from {M}ozambique. Cham: Springer.

Channa, H., Ricker-Gilbert, J., Feleke, S., and Abdoulaye, T. (2022). Overcoming smallholder farmers’ post-harvest constraints through harvest loans and storage technology: insights from a randomized controlled trial in Tanzania. J. Dev. Econ. 157:102851. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102851

Chigeto, A. D., and Angelo, A. (2021). Farmers’ technology adoption decision and use intensity in the agricultural sector: case of Masha District (double hurdle model). Int. J. Commer. Financ. 6, 31–40.

Crudeli, L., Mancinelli, S., Mazzanti, M., and Pitoro, R. (2022). Beyond individualistic behaviour: social norms and innovation adoption in rural Mozambique. World Dev. 157:105928. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105928

Deaton, A. (2019). The analysis of household surveys (reissue edition with a new preface): A microeconometric approach to development policy. London: World Bank.

DFID (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets, section 2.1. Department for International Development (DFID). London: Departement for International Development.

Dhehibi, B., Dhraief, M. Z., Ruediger, U., Frija, A., Werner, J., Straussberger, L., et al. (2022). Impact of improved agricultural extension approaches on technology adoption: evidence from a randomised controlled trial in rural Tunisia. Exp. Agric. 58:e13. doi: 10.1017/S0014479722000084

Dhehibi, B., Werner, J., and Qaim, M. (2018). Designing and conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for impact evaluations of agricultural development research: A case study from ICARDA’S “mind the gap” project in Tunisia’. Manuals and guidelines 1. Beirut, Lebanon: The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

Dijkink, B., Broeze, J., and Vollebregt, M. (2022). Hermetic bags for the storage of maize: perspectives on economics, food security and greenhouse gas emissions in different sub-Saharan African countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:767089. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.767089

Dodds, B. (2020). Advances in postharvest management of cereals and grains. Cambridge: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing.

Doss, C. (2001). How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana. Agric. Econ. 25, 27–39. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5150(00)00096-7

Dube-Takaza, T., Maumbe, B. M., and Parwada, C. (2023). Agricultural technology adoption for smallholder small grain farmers in Zimbabwe. Implications for food system transformation and sustainability. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 26, 882–903. doi: 10.22434/ifamr2022.0114

Esnaashariyeh, A., Kirti, C., Anthony, R., and Suresh, R. (2023). Impact of education and training on technology adoption by Agri producers. J. Survey Fisheries Sci. 12:316.

Feder, G., Just, R. E., and Zilberman, D. (1985). Adoption of agricultural innovations in developing countries: a survey. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 33, 255–298. doi: 10.1086/451461

Foy, C., and Wafula, M. (2016). Scaling up of hermetic bag technology (PICS) in Kenya: Review of successful scaling of agricultural technologies, report for USAID: Contracted under AID-OAA-M-13-00017. E3 analytics and evaluation project. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development.

Frisancho, V., and Valdivia, M. (2020). Savings Groups Reduce Vulnerability, but have Mixed Effects on Financial Inclusion Los grupos de ahorro reducen la vulnerabilidad, pero tienen efectos mixtos en la inclusión financiera. Available online at: https://eulacfoundation.org/system/files/digital_library/2023-07/savings_groups_reduce_vulnerability_but_have_mixed_effects_on_financial_inclusion.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed October 15, 2025).

Gartaula, H. N., Atreya, K., Sapkota, A., Mukhopadhyay, P., Chadha, D., and Puskur, R. (2025). A systematic review of agricultural projects’ contributions to women’s empowerment. NPJ Sustain. Agric. 3:22. doi: 10.1038/s44264-025-00061-5

George, M. L. C. (2011). Effective grain storage for better livelihoods of African farmers project. Completion report, June 2008 to February 2011. El Batan: International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Ghimire, R., Huang, W. C., and Pouled, M. P. (2015). Adoption intensity of agricultural technology: empirical evidence from smallholder maize farmers in Nepal. Int. J. Agric. Innov. Res. 4, 139–146.

Harou, A. P., Madajewicz, M., Michelson, H., Palm, C. A., Amuri, N., Magomba, C., et al. (2022). The joint effects of information and financing constraints on technology adoption: evidence from a field experiment in rural Tanzania. J. Dev. Econ. 155:102707. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102707

Ibro, G., Sorgho, M. C., Idris, A. A., Moussa, B., Baributsa, D., and Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. (2014). Adoption of cowpea hermetic storage by women in Nigeria, Niger and Burkina Faso. J. Stored Prod. Res. 58, 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2014.02.007

Kassie, M., Jaleta, M., Shiferaw, B., Mmbando, F., and Mekuria, M. (2013). Adoption of interrelated sustainable agricultural practices in smallholder systems: evidence from rural Tanzania. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80, 525–540. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.08.007

Kassie, M., Ndiritu, S. W., and Stage, J. (2014). What determines gender inequality in household food security in Kenya? Application of exogenous switching treatment regression. World Dev. 56, 153–171. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.025

Khan, F. U., Nouman, M., Negrut, L., Abban, J., Cismas, L. M., and Siddiqi, M. F. (2024). Constraints to agricultural finance in underdeveloped and developing countries: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 22:9388. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2024.2329388

Kotu, B. H., Abass, A. B., Hoeschle-Zeledon, I., Mbwambo, H., and Bekunda, M. (2019). Exploring the profitability of improved storage technologies and their potential impacts on food security and income of smallholder farm households in Tanzania. J. Stored Prod. Res. 82, 98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2019.04.003

Kumar, D., and Kalita, P. (2017). Reducing postharvest losses during storage of grain crops to strengthen food security in developing countries. Foods 6:8. doi: 10.3390/foods6010008,

Lane, B., and Woloshuk, C. (2017). Impact of storage environment on the efficacy of hermetic storage bags. J. Stored Prod. Res. 72, 83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2017.03.008,

Lartey, D., and Glaser, M. A. (2024). Towards a sustainable transport system: exploring capacity building for active travel in Africa. Sustainability 16:313. doi: 10.3390/su16031313

Manda, J., Azzarri, C., Feleke, S., Kotu, B., Claessens, L., and Bekunda, M. (2021). Welfare impacts of smallholder farmers’ participation in multiple output markets: empirical evidence from Tanzania. PLoS One 16:e0250848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250848,

Manda, J., Feleke, S., Mutungi, C., Tufa, A. H., Mateete, B., Abdoulaye, T., et al. (2024). Assessing the speed of improved postharvest technology adoption in Tanzania: the role of social learning and agricultural extension services. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 202:123306. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123306

Martey, E., Maxwell Etwire, P., Mohammed Suraj, M., and Goldsmith, P. (2023). PICS or poly sack: traders’ willingness to invest in storage protection technologies. J. Agric. Food Res. 14:100691. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100691

Matous, P., Todo, Y., and Pratiwi, A. (2015). The role of motorized transport and mobile phones in the diffusion of agricultural information in Tanggamus regency, Indonesia. Transportation 42, 771–790. doi: 10.1007/s11116-015-9646-6

Milkias, D. (2020). Factors affecting high yielding Teff varieties adoption intensity by small holder farmers in west Showa zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Econ. Energy Environ. 5:6. doi: 10.11648/j.ijeee.20200501.12

Miura, K., Kijima, Y., and Sakurai, T. (2020) Intrahousehold bargaining and agricultural technology adoption: experimental evidence from Zambia. Kyoto, Japan.

Mizinduko, M. M., Moen, K., Likindikoki, S., Mwijage, A., Leyna, G. H., Makyao, N., et al. (2020). HIV prevalence and associated risk factors among female sex workers in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: tracking the epidemic. Int. J. STD AIDS 31, 950–957. doi: 10.1177/0956462420917848,

Mlambo, S., Mvumi, B. M., Stathers, T., Mubayiwa, M., and Nyabako, T. (2017). Field efficacy of hermetic and other maize grain storage options under smallholder farmer management. Crop Prot. 98, 198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2017.04.001

Moussa, B. (2009). Evaluating the effectiveness of alternative extension methods: Triple-bag storage of cowpeas by small-scale farmers in West Africa, selected paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association 2009, AAEA & ACCI joint annual meeting, July 26–29, 2009. Milwaukee, WI: ACCI.

Moussa, B., Abdoulaye, T., Coulibaly, O., Baributsa, D., and Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. (2014). Adoption of on-farm hermetic storage for cowpea in west and Central Africa in 2012. J. Stored Prod. Res. 58, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2014.02.008

Moussa, B., Otoo, M., Fulton, J., and Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. (2011). Effectiveness of alternative extension methods through radio broadcasting in West Africa. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 17, 355–369. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2011.576826

Mponzi, W. P., Msaky, D. S., Binyaruka, P., and Kaindoa, E. W. (2023). Exploring the potential of village community banking as a community-based financing system for house improvements and malaria vector control in rural Tanzania. PLoS Glob. Public Health 3:e0002395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002395,

Murdock, L. L. L., Murdock, L. L., Margam, V., Baoua, I., Balfe, S., and Shade, R. E. (2012). Death by desiccation: effects of hermetic storage on cowpea bruchids. J. Stored Prod. Res. 49, 166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2012.01.002

Muriuki, N., Munyua, C., and Wanga, D. (2016). Communication channels in adoption of technology with a focus on the use of Purdue improved crop storage (PICS) among small scale maize farmers in Kenya. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 6:18.

Musara, J., Chikuvire, T., and Moyo, M. (2010). Determinants of micro irrigation adoption for maize production in smallholder irrigation schemes: case of Hama Mavhaire irrigation scheme, Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 10:51483. doi: 10.4314/ajfand.v10i1.51483

Mutambuki, K., and Likhayo, P. (2021). Efficacy of different hermetic bag storage technologies against insect pests and aflatoxin incidence in stored maize grain. Bull. Entomol. Res. 111, 499–510. doi: 10.1017/S0007485321000213,

Mutungi, C., and Affognon, H. (2013). Fighting food losses in Tanzania. The way forward for postharvest research and innovations, ICIPE policy brief. Nairobi: ICIPE.

Nakoma, T. N., Leslie, J. F., Kaengeza, S. P., Gama, A. P., Mvumi, B. M., Chamboko, T., et al. (2025). Barriers to hermetic bag adoption among smallholder farmers in Malawi. Sustainability 17:1231. doi: 10.3390/su17031231

Ninsiima, R., Mshenga, P., and Okello, D. (2025). Influence of social norms on blockchain technology adoption: a structural equation modelling approach among smallholder barley farmers in Uganda. Discover Agric. 3:89. doi: 10.1007/s44279-025-00254-z

Ntume, B., Nalule, A. S., and Baluka, S. A. (2015). The role of social capital in technology adoption and livestock development. Livest. Res. Rural. Dev. 27:181. Available at: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd27/9/balu27181.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

Odjo, S., Bongianino, N., González Regalado, J., Cabrera Soto, M. L., Palacios-Rojas, N., Burgueño, J., et al. (2022). Effect of storage technologies on postharvest insect Pest control and seed germination in Mexican maize landraces. Insects 13:878. doi: 10.3390/insects13100878,

Omotilewa, O. J., and Baributsa, D. (2022). Assessing the private sector’s efforts in improving the supply chain of hermetic bags in East Africa. Sustainability 14:12579. doi: 10.3390/su141912579

Omotilewa, O. J., Ricker-Gilbert, J., Ainembabazi, J. H., and Shively, G. E. (2018). Does improved storage technology promote modern input use and food security? Evidence from a randomized trial in Uganda. J. Dev. Econ. 135, 176–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.006,

Pearson, J. (2011). Training and beyond: seeking better practices for capacity development. OECD development co-operation working papers, no. 1. Paris: OECD publishing.

Rabé, M. M., Baoua, I. B., and Baributsa, D. (2021). Adoption and profitability of the Purdue improved crop storage technology for grain storage in the south-central regions of Niger. Agronomy 11:2470. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11122470

Ragasa, C., Berhane, G., Tadesse, F., and Taffesse, A. S. (2013). Gender differences in access to extension services and agricultural productivity. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 19, 437–468. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2013.817343

Rasanjali, W. M. C., Wimalachandra, R. D. M. K. K., Sivashankar, P., and Malkanthi, S. H. P. (2021). Impact of agricultural training on farmers’ technological knowledge and crop production in Bandarawela agricultural zone. Appl. Econ. Bus. 5, 37–50. doi: 10.4038/aeb.v5i1.27

Rayhan, S. J., Rahman, M. S., and Lyu, K. (2023). The role of rural credit in agricultural technology adoption: the case of Boro rice farming in Bangladesh. Agriculture 13:179. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13122179

Regassa, M. D., Degnet, M. B., and Melesse, M. B. (2023). Access to credit and heterogeneous effects on agricultural technology adoption: evidence from large rural surveys in Ethiopia. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 71, 231–253. doi: 10.1111/cjag.12329

Ricker-Gilbert, J., and Jones, M. (2015). Does storage technology affect adoption of improved maize varieties in Africa? Insights from Malawi’s input subsidy program. Food Policy 50, 92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.10.015

Shibata, R., Cardey, S., and Dorward, P. (2020). Gendered intra-household decision-making dynamics in agricultural innovation processes: assets, norms and bargaining power. J. Int. Dev. 32, 1101–1125. doi: 10.1002/jid.3497

Smale, M., Assima, A., Kergna, A., Thériault, V., and Weltzien, E. (2018). Farm family effects of adopting improved and hybrid sorghum seed in the Sudan savanna of West Africa. Food Policy 74, 162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.01.001,

Solon, G., Haider, S. J., and Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). What are we weighting for? J. Hum. Resour. 50, 301–316. doi: 10.3368/jhr.50.2.301

Spittal, M. J., Carlin, J. B., Currier, D., Downes, M., English, D. R., Gordon, I., et al. (2016). The Australian longitudinal study on male health sampling design and survey weighting: implications for analysis and interpretation of clustered data. BMC Public Health 16, 1062–1022. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3699-0,

Swamy, V. (2014). Financial inclusion, gender dimension, and economic impact on poor households. World Dev. 56, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.019

Tanager (2018). AgResults Kenya on farm storage pilot project: Airtight (hermetic) devices. Summary project report. Nairobi, Kenya: Report prepared by Tanager.

Tefera, T., Kanampiu, F., De Groote, H., Hellin, J., Mugo, S., Kimenju, S., et al. (2011). The metal silo: an effective grain storage technology for reducing post-harvest insect and pathogen losses in maize while improving smallholder farmers’ food security in developing countries. Crop Prot. 30, 240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2010.11.015

Udomkun, P., Wossen, T., Nabahungu, N. L., Mutegi, C., Vanlauwe, B., and Bandyopadhyay, R. (2018). Incidence and farmers’ knowledge of aflatoxin contamination and control in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Food Sci. Nutr. 6, 1607–1620. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.735,

UN (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York, NY, US: UN.

Villers, P., Bruin, T., and Navarro, S. (2006). “Development and applications of the hermetic storage technology” in 9th international working conference on stored product protection, 15 to 18 October 2006. eds. V. M. S. I. Lorini, B. Bacaltchuk, H. Beckel, D. Deckers, and E. Sundfeld (Campinas, São Paulo: Brazilian Post-harvest Association - ABRAPOS), 719–729.