- Department of Physical and Inorganic Chemistry, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, Lithuania

The use of biological additives often enhances plant fertilization efficiency and reduces the environmental impact of fertilizers; however, their effectiveness varies depending on the context. It is particularly important that such additives are compatible with mineral fertilizers and remain viable and effective during industrial production. The aim of this study was to develop bulk NPK compound fertilizers supplemented with the biological additive Fosfix, a commercial product from the Lithuanian company Bioenergy LT. This product contains bacteria that help absorb phosphorus from insoluble soil compounds. The study also aimed to evaluate their agronomic effectiveness under field conditions. The fertilizer formulations incorporating the biological additive were developed at Kaunas University of Technology, with the goal of adapting the additive for industrial fertilizer production. Laboratory tests demonstrated that optimal fertilizer characteristics – commercial fraction content of 64–78%, granule strength of 28–41 N per granule, and moisture content of 15–16.5% – were achieved using a raw material mixture containing up to 60% recycled product. These laboratory conditions were successfully applied at pilot scale in industry, and a pilot batch of the developed product was produced in a fertilizer manufacturing company. Agrochemical tests were conducted at the Rumokai Experimental Station, a branch of the Lithuanian Agricultural and Forestry Research Centre. Field tests showed that the biological additive improved the performance of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) variety Severa KWS compared to spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) variety Triso: initial germination increased by 6%, root yield by 5.78 t·ha1, and basic sugar yield by 5.16 t·ha−1. In conclusion, the newly developed fertilizer formulations promote plant physiological processes, support the expression of genetic potential, and ensure minimal nutrient loss.

1 Introduction

Considering current global challenges such as the growing world population, rising food demand, intensive agriculture, and climate change (Loiko and Islam, 2024), one of the most critical objectives in crop production is to achieve high yields of high-quality, environmentally friendly produce while optimizing input costs. Numerous long-term scientific studies indicate that approximately 30–35% of crop yield increases can be attributed to fertilizer effectiveness. However, fertilizer efficiency is affected by multiple factors, including physical and chemical properties of soil, fertilization levels, nutrient ratios, timing and method of application, and precision of application (Zaib et al., 2023). A global meta-analysis covering nearly 2,500 observations found that fertilizer application increased crop yields by an average of 30.9%, with variations depending on fertilizer type and crop species (Ishfaq et al., 2023). Long-term studies also highlight that excessive or imbalanced fertilizer application often leads to diminishing returns and reduced efficiency, emphasizing the importance of balanced nutrient management for maintaining both yield stability and soil health (Yokamo et al., 2023). Therefore, researchers and fertilizer industry specialists are continuously seeking innovative approaches to improve fertilizer efficiency and sustainability. In crop production, it is important not only to prepare the soil and sow crops properly, but also to understand and implement full range of practices necessary for successful cultivation. One of the most important measures is fertilization. Nutrient application must be balanced, as both macronutrients and micronutrients act in combination, not in isolation. If the soil contains a deficiency or excess of one nutrient or microelement, the plant may struggle to absorb others (Fan et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2024).

Proper nutrient uptake by plants is also influenced by the soil itself, which consists of mineral particles, water, air, and organic matter, containing living organisms. Soil is a complex, dynamic, and living system which performs many vital functions. It is a source of biomass and a medium in which plant nutrients accumulate, are filtered, and undergo transformations (Turner, 2021; Cotrufo and Lavallee, 2022). Furthermore, organic matter of the soil is essential for nutrient availability and soil structure enhances fertility and resilience. However, soil quality is under threat from degradation, largely driven by intensive agricultural practices, which progressively undermine its ecological functions (Nikolaidis and Bidoglio, 2013; Singh et al., 2024).

Farmers and scientists have observed that intensive and unbalanced use of fertilizers and plant protection products accelerates soil degradation and reduces fertility, while low biological activity of the soil allows undecomposed plant residues to promote pathogen accumulation. Long-term field trials and meta-analyses indicate that mineral fertilizers, although initially increasing microbial biomass by around 15%, eventually disrupt the soil’s biological balance. This leads to dependency on higher fertilizer inputs, declining crop quality, rising costs, and weakened soil ecosystems and microbial functions (Geisseler and Scow, 2014; Šimanský et al., 2022).

European policymakers responsible for agricultural output have recognized the risks associated with unregulated fertilizer use. Under the EU Fertilizer Regulation (EU Regulation, 2019/1009), only products listed in the official European Fertilizer Register may be placed on the market, ensuring compliance with safety and quality standards. In parallel, the evolving Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) increasingly supports soil-conserving practices. Future subsidies are expected to focus on certified eco-schemes and farming systems that prevent soil degradation and promote sustainability (EUR-Lex, 2019; EU CAP Network, 2023; Transport and Environment, 2020). One of the most advanced approaches to enhancing fertilizer efficiency while maintaining sustainability of agroecosystem is microbiology of the soil. Soil’s biological activity, characterized by indicators such as microbial biomass carbon content, respiration, and enzyme activity, is a key indicator of soil health (Bhaduri et al., 2022; Mącik et al., 2020). Biofertilizers, i.e., microbial inoculants designed to diversify soil microbiota and activate natural processes, are strongly recommended for restoring degraded soils. These products significantly improve nutrient cycling and soil structure without polluting the environment or negatively impacting plants, animals, or humans (Kumar et al., 2021; Ammar et al., 2023). Biological preparations are regarded as soil improvement materials rather than fertilizers, as they have been created using natural processes that have successfully been going on in nature for millions of years. Environmental stresses caused by climate change and human activity limit plant growth and yields. The results show that the application of microbial fertilizers significantly increases soil’s microbial diversity, maintains its microecological balance, and effectively improves its quality (Wei et al., 2024; Yusuf et al., 2025). The Use natural, nontoxic bio-stimulants to strengthen plants’ natural defense systems offers a sustainable solution to improve crop performance under unfavorable conditions (Posmyk and Szafrańska, 2016).

The production and use of biological products in agriculture have significantly increased in recent decades, and this trend is expected to continue (Pisante et al., 2012; FAO, 2021; Zapka, 2023; National Research Council, 2002). This growth is largely driven by the need to remain competitive, improve depleted natural soil fertility, meet the demands of increasingly selective consumers, and address challenges related to intensive farming. The use of microbiological products provides opportunities to enhance farm productivity through environmentally friendly and cost-effective approaches. Each type of microorganism (bio-activator) performs a specific function in the soil, for example, by improving nutrient absorption or reducing the required amount of chemical fertilizers. In recent years, the most effective strategies have focused on incorporating biologically active substances into fertilizers, thereby advancing sustainable farming practices (Bargaz et al., 2018; Rashid et al., 2016; Stamenkovic and Beškoski, 2018; Sinkevičienė and Pekarskas, 2019; Díaz-Rodríguez et al., 2025). On the other hand, microorganisms grown under laboratory conditions can be sensitive to temperature fluctuations or competition with native soil microbes, which may limit their effectiveness under real field conditions (Zhao et al., 2024; Gonzalez and Aranda, 2023; Kapinusova et al., 2023).

Farmers and representatives of agribusiness s are encouraged to stay informed about current scientific advances in agriculture, follow expert recommendations, and adopt more sustainable and cost-effective practices. Partnerships between business and science are beneficial for both parties, as well as for nature (Kindangen et al., 2023; European Commission, 2025; SAI Platform, 2015; Masquelier et al., 2025).

Considering these challenges, the aim of this work is to develop a bulk NPK compound fertilizer with the biological additive Fosfix in the laboratory, scale up its production to industrial levels, and test it under field conditions. It is assumed that the use of this fertilizer will improve efficiency ofnutrient use by plantsand minimize the environmental impact of fertilization. The results of this study will contribute to expanding the range of bulk compound fertilizers with bioactivators and support the sustainability of agroecosystems.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Production of bulk compound NPK fertilizers with Fosfix in the laboratory

Technical salts were used to produce bulk compound NPK fertilizers with micronutrients (5–15–30 + S + Zn for spring wheat and 12–11–22 + Na + S + B for sugar beets): potassium chloride (KCl) with a K2O concentration of 60.0% (Belaruskalij Belarus); ammonium dihydrogen phosphate ((NH4)2HPO4) with P2O5 concentration of 46.0% and N content of 18.0% (UAB “Lifosa,” Lithuania); ammonium hydrogen phosphate (NH4H2PO4) with P2O5 concentration of 52.0% and N content of 12.0% (UAB Lifosa, Lithuania); ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) with N concentration of 21.0% and S concentration of 23.0% (Yara, Norway); and zinc sulfate monohydrate (ZnSO4·H2O) with Zn concentration of 35.0% (Haida, China), sodium chloride (NaCl) with Na concentration of 39.3% (Belaruskalij, Belarus), boric acid (H3BO3) with B concentration of 17.5% (Eti Maden, Turkey).

The biological preparation Fosfix was used as a bioactive component, with Bacillus sp. bacteria as its active ingredient. The main purpose of the preparation is to release phosphorus into the soil and, with the help of bacteria, convert phosphorus compounds which are difficult to absorb into forms available to plants. The preparation is soil-friendly, with a pH of 6.5 (Bioenergy LT, 2018).

Compound NPK + S + Zn fertilizers were granulated in the laboratory using a drum granulator, the geometric parameters of which correspond to the dimensional proportions of granulators of this type used in industry. Granulation was carried out using the wet granulation method. The concentration of macro plant nutrients (N, P2O5, and K2O) and physical properties of the resulting product were examined using standard fertilizer testing methods.

2.2 Properties of bulk compound NPK fertilizers with Fosfix prepared in the laboratory

Total nitrogen (N) concentration in both NPK fertilizers was determined using the Kjeldahl method with a Turbodog mineralizer and an automatic Vapodest 45 s distillation system (Gerhardt).

Sample digestion was performed with 96% sulfuric acid following the DIN EN ISO 9001 standard. The method provides an accuracy of ±0.5%. To determine the content of ammonium nitrogen, results were reported to the nearest 0.1% and expressed as the arithmetic mean of two parallel measurements, provided that the difference between them did not exceed 0.5% at a 95% confidence level. Potassium (K2O) concentration in NPK fertilizers was analyzed using flame photometry with the PFP-7 device (Jenway). The flame was produced by burning a natural gas–air mixture at temperatures ranging from 1,500 to 2000 °C. Potassium levels were quantified based on a calibration curve prepared from aqueous KCl solutions of known concentrations. Phosphorus (P2O5) concentration was determined by the photocolorimetry method, involving the formation of a complex with molybdenum and measurement of UV–VIS absorbance at 440 nm, using a 10.0 mm cuvette. All measurements were carried out with a T70/T70 + spectrophotometer (PG Instruments Limited). The standard error of the absorbance values was ±0.004 Abs.

Granular fertilizers were fractionated using RETSCH woven sieves (DIN-ISO 3310/1), with mesh sizes: 1.0; 2.0; 3.15; 4.0; 5.0 mm, and the fraction amount was determined by weighing with an electronic balance WPS 210/C KERN ABJ (balance accuracy ±0.001 g).

To determine the static strength of granules, tests were performed using a device (IPG–2), with a maximum compressive strength of 200 N/granule (error ±1.6%). The strength was determined by crushing 20 granules and calculating the arithmetic mean, relative, standard and absolute errors according to the interval estimate.

The moisture content was determined using the electronic moisture analyzer HG53, which operates on the thermogravimetric principle, i.e., calculates weight loss upon heating the sample to constant mass.

The bulk density of fertilizer granules was determined using a graduated 100 cm3 cylinder, which was filled with granules and by weighing with the electronic balance WPS 210/C KERN ABJ (balance accuracy ±0.001 g).

The hygroscopicity of NPK granular fertilizers was evaluated under controlled moisture conditions. Samples were stored in a desiccator for 9 days under two different environments: at 55–60% relative humidity maintained by saturated sodium nitrite (NaNO2) and at 100% relative humidity maintained by distilled water, both at 20–25 °C.

To assess the viability of Bacillus sp. bacteria, a 2 g sample of fertilizer was dissolved in 100 mL of 0.9% NaCl solution. Then, 0.1 mL of this solution was inoculated onto a Petri dish and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. During this period, bacterial growth occurred, and the number of viable colonies was subsequently counted (Mažylytė et al., 2022; ASTM International, 2020).

2.3 Field experiments of compound NPK fertilizer with Fosfix

A two-year field experiment (2022–2023) was conducted on deep gleyic, carbonate-leached soil. The agrochemical properties of the soil were as follows: pHKCl – 6.4, organic carbon – 0.76%, P2O5–156 mg/kg, K2O – 182 mg·kg−1. The spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) of Triso variety and the sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) of Severa KWS variety were grown at the Rumokai Experimental Station, which is part of the Lithuanian Research Center for Agriculture and Forestry (LAMMC). The station is located in Klausučiai village, Vilkaviškis district, in the southwestern part of Lithuania (54.6211° N, 22.8470° E), near the town of Kybartai and close to the border with Poland. It plays an important role in agricultural research and technology development and is one of the key national facilities for long-term agronomic research and crop trials.

The spring wheat variety Triso was developed in Germany by the DSV seed company, and was registered in Lithuania in 2005. The grain is of a food type, medium-early, the plants of medium height, and resistant to lodging. The wheat grains of this variety mature in an average of 93 days. Severa KWS is a diploid, medium-yielding. This diploid sugar beet variety was developed in Germany by the KWS SAAT AG seed company. According to the breeder, sugar beets of this variety are resistant to rhizomania (a necrotic vein yellowing virus).

The indicators characterizing the quality of the spring cereal and sugar beet harvests were determined according to the standard methodologies used by LAMMC, which are based on Commission Regulation (EU) No 742/2010 and the guidelines of the International Commission for Uniform Methods of Sugar Analysis (ICUMSA).

2.4 Statistical analysis of results

All data are reported as means with measures of dispersion. For physical properties of the granular product (static strength, moisture, bulk density), results are presented as the mean with the 95% confidence interval (CI). Agronomic and quality traits for wheat and sugar beet are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD); standard error (SE) is additionally reported in tables to indicate the precision of the mean.

Because only two fertilizer treatments were compared (NPK vs. NPK + F), between-group differences were evaluated using two-sample (independent) t-tests, with α = 0.05 taken as the threshold for statistical significance. Where relevant, non-overlapping 95% CI was also interpreted as supportive evidence of a meaningful difference. Sample size for field traits was n = 30 per treatment unless stated otherwise.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Different methods of incorporating bacterial preparations into granular NPK fertilizers

For this study, a widely used and commercially available compound NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn fertilizers were selected, with the expectation that, if results were positive, the laboratory findings could be applied to real-world production processes. To assess the feasibility of incorporating a bacterial preparation into the fertilizer and ensuring bacterial viability, experiments with bacterial additives were carried out under laboratory conditions. The experiment was structured into several approaches to determine the most effective method of incorporating the bacterial preparation.

First, an attempt was made to introduce the bacterial preparation into the wax hardener and to assess bacterial viability by simulating the actual conditions of wax preparation and application. The mixture of wax and bacteria was maintained in the laboratory for 12 h at a temperature of 90–100 °C. This method proved ineffective, as the bacteria did not survive exposure to wax at the working temperature.

Further studies were conducted by attempting to spray the bacterial preparation and wax onto granulated product through a single nozzle, with the reagents supplied from separate containers. The wax-to-bacteria ratio and drying temperature were adjusted to simulate real production conditions. However, the number of viable bacteria after application was found to be only 103 CFU·g−1, which is significantly lower than the commonly recommended range of 106–109 CFU·g−1 (Dos Reis et al., 2024; Agake et al., 2022; Fusco et al., 2022).

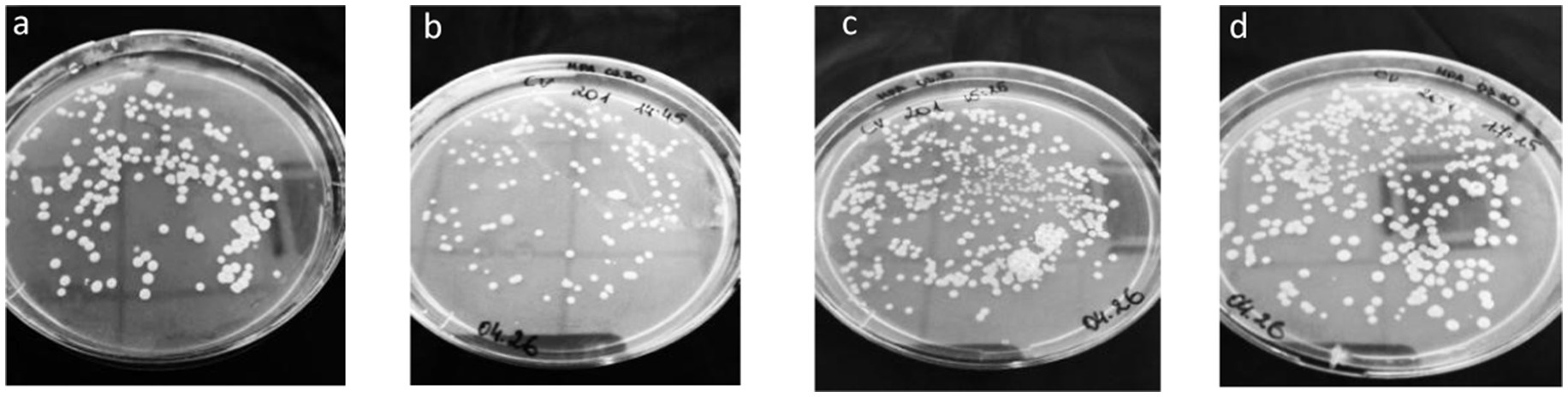

Then another method of introducing the bacterial preparation was chosen – introduction into the raw material mixture and granulation of the entire mixture together. When granulating NPK fertilizers under laboratory conditions, a mixture of 100 g of dry raw materials, calculated according to the material balance (KCl, (NH4)2HPO4, NH4H2PO4, (NH4)2SO4, ZnSO4·H2O), and the bacterial preparation Fosfix (rate 1.5 L·t−1) was prepared, which was moistened with water (8 cm3/100 g H2O or 7.4%) and granulated (each experiment was performed in triplicate) using a laboratory drum granulator. Before that, the raw materials, which are in the form of granules (ammonium dihydrogen phosphate and ammonium hydrogen phosphate), were ground. In NPK fertilizers with the Fosfix additive produced in this way and thermostated at 80 °C for 24 h, the viability of Bacillus sp. bacteria was tested, The results showed that the bacteria remained viable under the tested conditions with the quantity of 4.5·107 CFU·g−1 (Figure 1a).

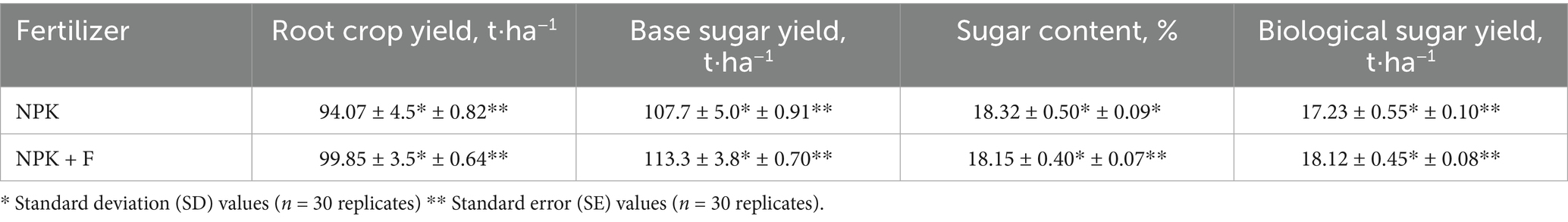

Figure 1. Bacillus sp. in NPK fertilizer 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix: (a) after 24 h of incubation at 80 °C (laboratory-manufactured fertilizer), (b) after the granulator, (c) after the dryer, (d) after the coating drum.

Having evaluated the results obtained on the viability of Bacillus sp. bacteria when added to the fertilizer raw material mixture before granulation together with the water used for irrigation, this wet granulation method was chosen for further studies.

3.2 Wet granulation and characterization of NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers

Since the granulated fertilizer samples from the bacterial viability study lacked high quality from a granulometric point of view, in order to improve the granulometric composition (which largely depends on the moisture of the raw materials), granulation was carried out using different amounts of water, constantly increased from 7.4 to 18%. To ensure the reliability of the results, mixtures with each different moisture content were granulated 3 times and the standard deviation of the results obtained was estimated. The granulated samples were dried under static conditions in an oven for 8 h at a temperature of 80 °C and classified according to the size of the granules. The commercial fraction of fertilizers, typically consisting of granules size from 2 to 5 mm, was separated. This size range is widely adopted in industrial practice and supported by existing European standards for physical characteristics (EN 1235 for sieve analysis) and optimal application (e.g., for modern spreading equipment). Afterwards, the most important properties of the bulk fertilizers’ commercial fraction were examined, including granule strength, moisture, bulk density, and hygroscopicity. Granuleswhich did not fall within the mentioned (2–5 mm) range, had to be returned to the granulation process at the raw material mixing stage as recycle.

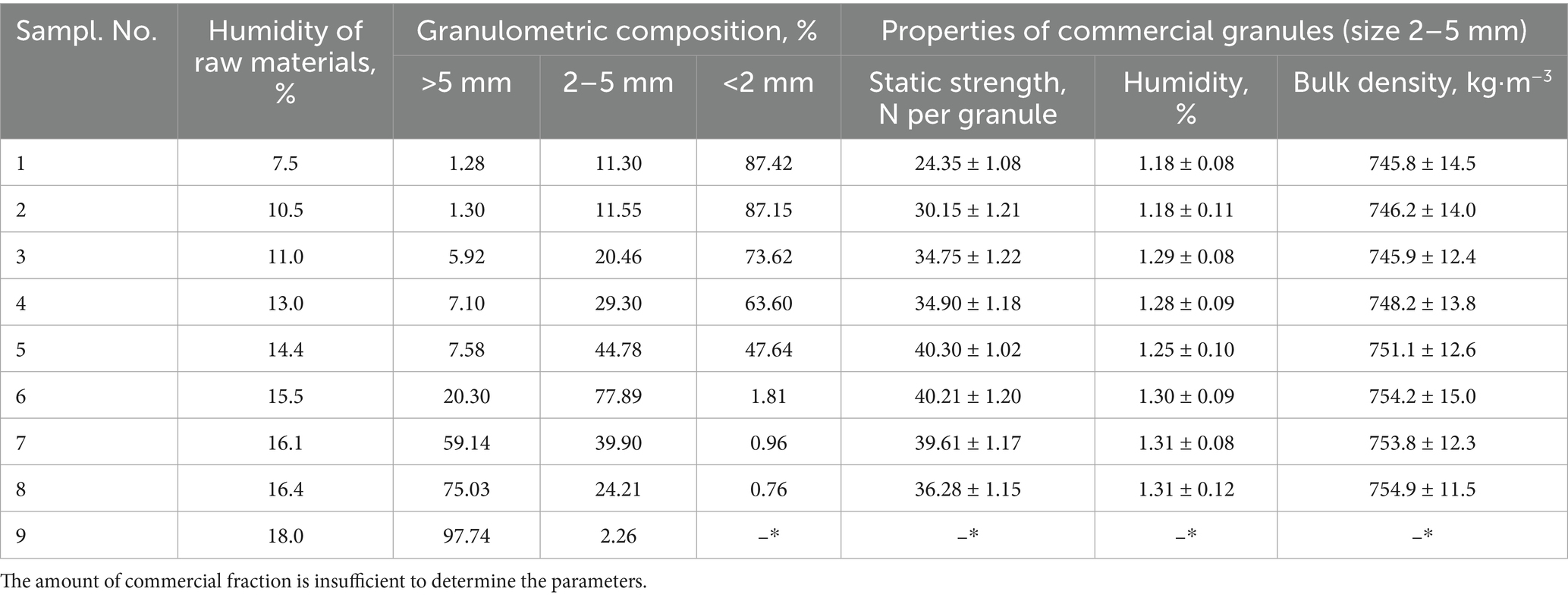

The properties of the granulated product are determined by many factors (such as the type of raw materials, their ratio, moisture content, amount of recycle, granulation conditions, etc.), but these factors cannot all be changed simultaneously. Therefore, to obtain a better-quality product, the initial tests were carried out without using a recycle and with varying moisture contents in the raw material mixtures. The selection of optimal moisture content is best indicated by the proportion of the commercial fraction in the granulated product, which is calculated as a percentage after determining the granulometric composition of the entire sample. The data from the laboratory samples produced without recycle are presented in Table 1.

This table presents the data by which the physical properties (static strength, moisture, bulk density) of granular NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers were determined. The figures represent the average of the measured values and the 95% confidence interval (CI) with a probability of 95%. The results of granulometric composition show that in samples 1–4, most granules (63.6–87.42%) were smaller than 2 mm, indicating that the selected moisture content of 7.5–13% in the raw material mixture was unsuitable. During granulation, raw material mass was too dry, so few granules of commercial size were produced, mainly resulting in a fine, dry fraction.

In sample 5, where the moisture content was 14.4%, a large amount (47.64%) of fine fraction was also determined. However, the proportion of the commercial fraction was similar (44.78%) suggesting that the moisture content was close to optimal. When the moisture content was too high (samples 7–9), most granules (75.03–97.74%) exceeded 5 mm in diameter. Such oversized granules are hazardous to equipment and pose safety risks to operators. Therefore, selecting the optimal amount of water is very important. Otherwise, the granulation process must be stopped, all oversized agglomerates removed, and the equipment restarted. The highest part of commercial fraction (77.89%) was achieved at 15.5% moisture content (sample 6). Therefore, it can be stated that this amount of moisture was optimal for wetting the raw material mixture.

The discussed results showed sufficient measurement reliability, as narrow confidence intervals (CI) were obtained. Overall, the static strength of the commercial fraction granules in the samples ranged from 24.35 ± 1.08 to 40.30 ± 1.02 N per granule, and the narrow CI indicates that the measurements are quite accurate. The observed differences between the samples are statistically significant. The moisture values were low and stable (1.18 ± 0.08 to 1.31 ± 0.12%), although in relative terms (due to the small absolute values), they had the widest CI and showed the largest relative fluctuation (6–9%). Bulk density was the most constant property, ranging from 745.8 ± 14.5 to 754.9 ± 11.5 kg·m−3, and the narrow CI indicates high reproducibility of the measurements.

When assessing the quality of a granular product, the following properties of commercial granular fertilizers are very important: granule strength, bulk density, and moisture content. Granule strength describes the compressive force that granules can resist and serves to evaluate the potential for disintegration into a fine powder, which can generate handling and application issues (e.g., dust formation, spreader clogging) during transport, storage, and field use (Fulton and Port, 2016). Bulk density indicates the volume occupied by a given mass of granules. Therefore, this value helps estimate transportation costs and provides an indirect indication of the granule’s roundness and flowability, as denser and more spherical granules tend to pack and flow better. Higher values (closer to 1 g·cm−3or 1,000 kg·m−3) generally correspond to more uniform, spherical particles and improved mechanical behavior during handling. Additionally, higher density indicates fewer pores, greater uniformity, enhanced pellet strength, and a lower risk of dust formation (Lillerand et al., 2021; Ulusoy, 2023; Zhou et al., 2017).

The data presented in Table 1 show that at the optimal moisture content (15.5%), the highest crushing strength of the granules in the commercial fraction was recorded, reaching 41.41 N per granule. This crushing strength is sufficiently high and is consistent with the findings of other researchersclaiming that fertilizer particle strength is influenced by moisture of granules (Xin et al., 2023; Macák and Krištof, 2016). The numerical values of the bulk density of the granules depend slightly on the moisture content of the granules of the commercial fraction but they differ by no more than 10 kg·m−3. This is expected, as bulk density is primarily influenced by granule shape and the type of raw materials used. The moisture content of the granulated product in all samples remained below 2%, which complies with standard requirements for bulk fertilizers.

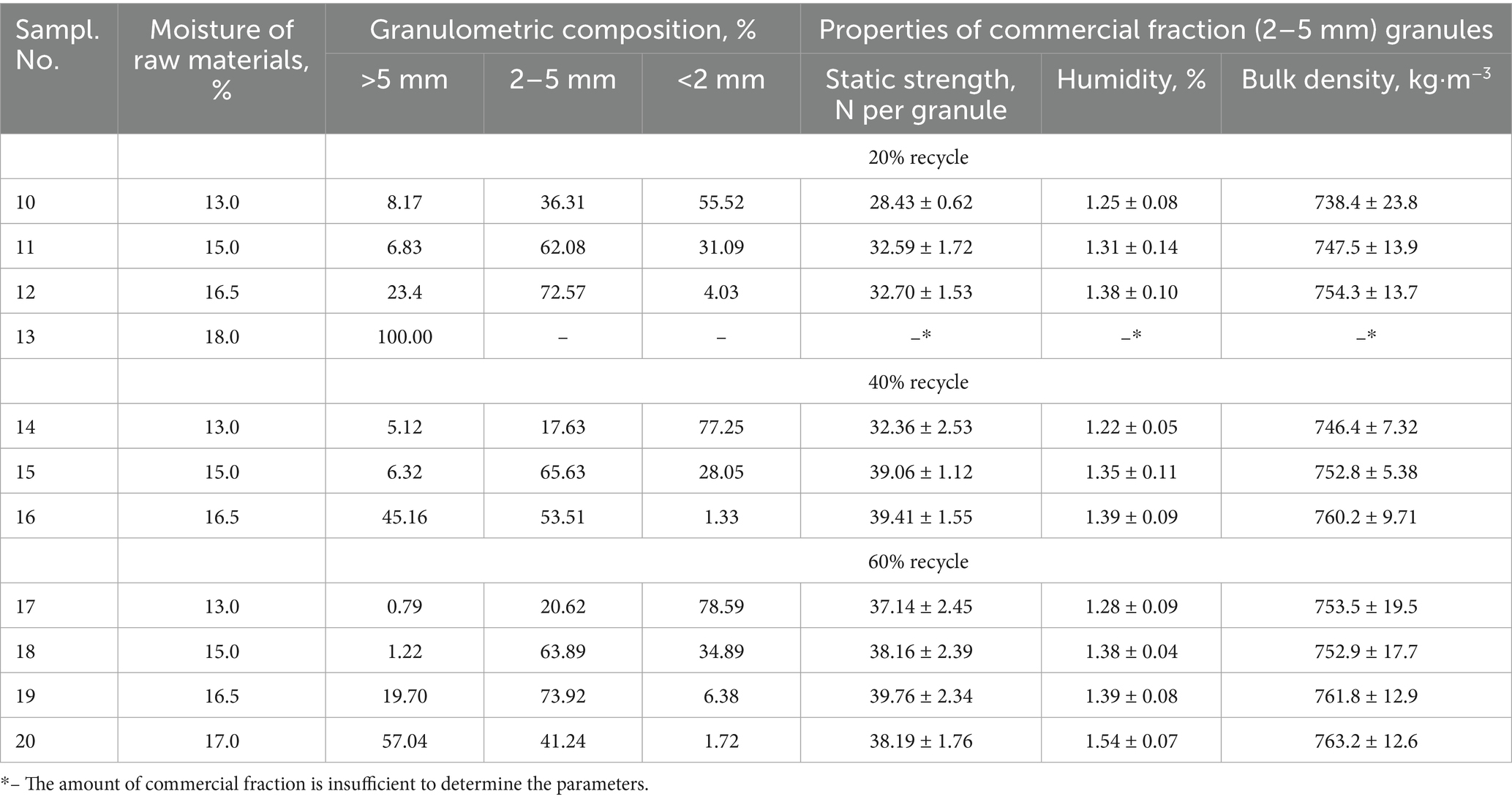

Next, to determine the best granulation conditions, the influence of the recycle fraction on the properties of the granulated product was investigated. Since, under real production conditions, a certain amount of recycle is required to maintain process stability (ensuring a balance between the raw material feed and the recycle flow, while preventing equipment overload), 20, 40, and 60% recycle fractions (consisting of particles smaller than 1 mm) were added to the raw material mixture. The initial moisture content of the raw materials was selected based on previous granulation results, while all other conditions were kept constant. However, like in other studies, using recycle in this study required adjustments to the moisture content to prevent excessive fines or agglomeration (Mefteh et al., 2013; Hidayat et al., 2025). At this stage of the study, the moisture content of the raw material mixtures and the resulting properties of the granulated product are presented in Table 2 as the average of the measured values and the 95% confidence interval (CI) with a probability of 95%.

Table 2. Parameters of NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix granulated fertilizers with the use of recycle (with ±CI data).

The data presented in Table 2 show that when using 20, 40, or 60% recycle, a moisture content of 13% in the raw material mixture is insufficient for successful granulation, as a very large amount (55.52–78.59%) of fine fraction is formed. When using 20 and 40% recycle, the best granulometric composition results were obtained with a raw material moisture content of 15.0–16.5%. In such cases, the commercial fraction constituted 54–74% of the total sample mass. When 18% moisture was used for hydration of raw materials with 20% recycle (sample 13), extremely large and round balls formed during granulation; therefore, this moisture level was not used in further studies. A 17% moisture content was also too high, as the amount of commercial fraction decreased significantly in sample 20. When using 60% recycle, the highest amount of commercial fraction (73.92%) was obtained with a 16.5% raw material moisture content.

The data characterizing the commercial fraction properties (Table 2) show that when the commercial fraction yield is highest, high-quality granules are obtained, as their static strength ranges from 26.06 to 37.41 N per granule. The numerical values of bulk density are very similar in all cases but remain relatively low. The moisture content of the final product with the use of return is slightly higher than when granulating without return but does not exceed 2%.

Analyzing statistical reliability of the presented granule properties, it can be stated that the static strength of the commercial fraction increased significantly when the amount of recycle was increased from 20% (28.43 ± 0.62 N per granule) to 40–60% (36.00 ± 2.53 to 39.76 ± 2.34 N per granule). However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the 40 and 60% recycle groups due to overlapping confidence intervals. Moisture content remained stable across all groups, but the highest value (1.54 ± 0.07) was obtained when using 60% recycle, the CI of which almost did not overlap with the lower values of the 20% group, indicating a potentially significant increase in moisture content. Bulk density values (738.4 ± 23.8 to 763.2 ± 12.6 kg·m−3) showed substantial overlap in the confidence intervals of the groups, suggesting no statistically significant differences and that the addition of different amounts of recycle (20, 40, or 60%) does not affect the bulk density of the granules.

When summarizing the influence of recycle on the granulated product, it can be stated that adding the recycle had a positive effect on the granulometric composition, but other product properties did not change. It was determined that to obtain the highest yield of the commercial fraction when using recycle (especially at 60%), more moisture had to be added to the raw materials. From a practical perspective, a higher moisture content in the raw materials extends the drying time and complicates operation of the equipment. Therefore, when granulating NPK fertilizers under real production conditions, it is advisable to use less than 60% recycle.

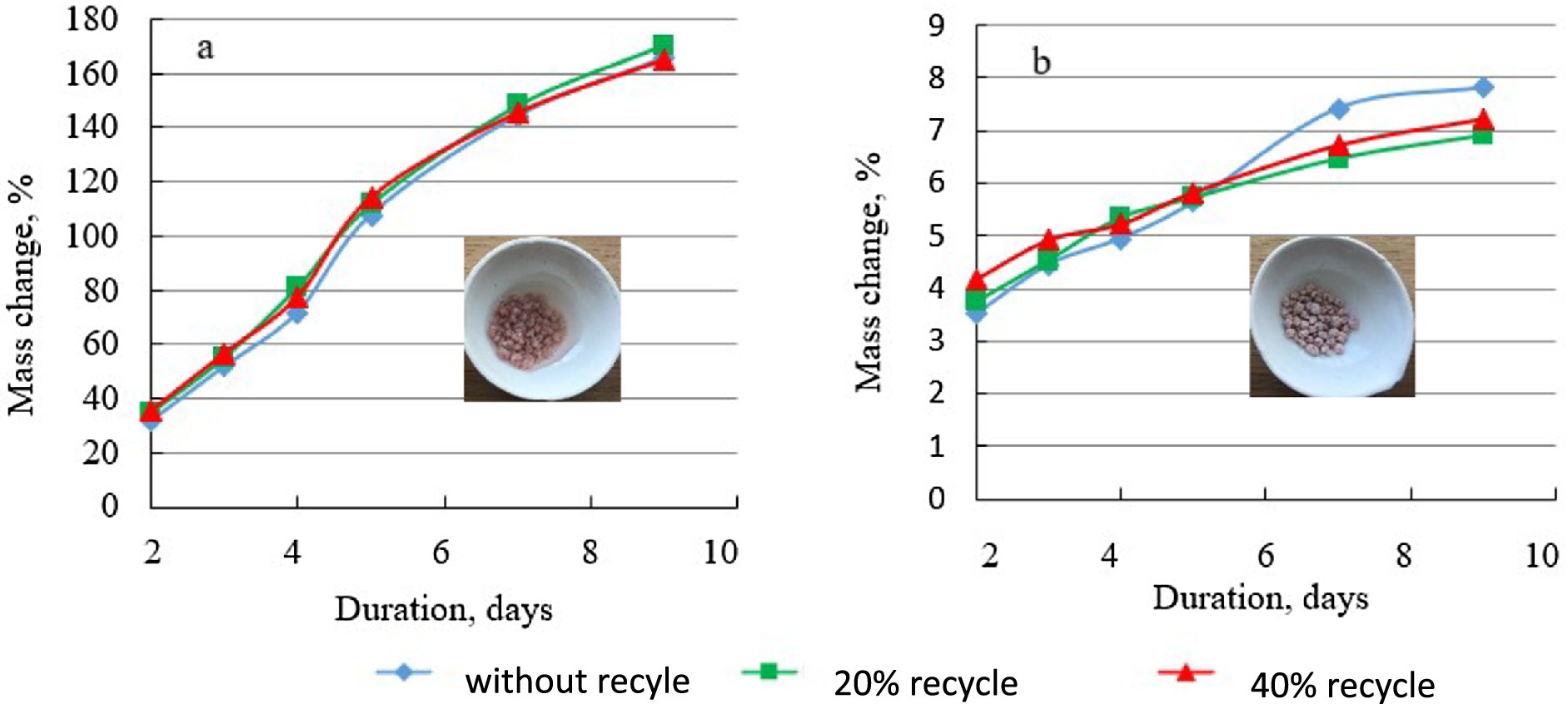

In addition to the previously discussed properties of granular fertilizers, hygroscopicity (the tendency of a substance to absorb moisture from air) is also an important parameter (YARA, 2025; Baird et al., 2023). It was evaluated by storing the granules under two controlled humidity conditions: in a desiccator above water (extreme conditions, i.e., 24.8–25.8 °C, equilibrium relative humidity 100%) and above a saturated sodium nitrite solution (favorable conditions, i.e., 24.8–25.8 °C, equilibrium relative humidity 59–62%). The results obtained are presented in Figure 2. They show that in all cases, fertilizers produced with and without recycle are highly hygroscopic when stored above water (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. Hygroscopicity of granular NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers: (a) above water, (b) above saturated sodium nitrite solution.

Under these conditions, the fertilizer mass increased by more than 160% within 9 days and continued to rise, causing the granules to lose their shape as they began to dissolve due to the large amount of absorbed water vapor. This is not as fast a process as in the case of calcium nitrate or ammonium nitrate, which was studied and described by Ch. Sigtryggsson, but it is still very obvious (Sigtryggsson et al., 2020) When stored above a saturated sodium nitrite solution, NPK fertilizers exhibited a mass change of only 7–8% within 9 days, and the granules maintained their shape (Figure 2b).

Thus, under favorable conditions, the granules are less hygroscopic; however, even a 7–8% mass increase from absorbed water vapor can compromise granule quality. These data must be considered. Therefore, during the process of fertilizer production moisture-protection measures (e.g., by applying coating materials such as wax, adding polyhalite or other materials to fertilizer) are recommended to ensure safe storage and transportation (Albadarin et al., 2017; Baird et al., 2023). Additionally, in real conditions, storage conditions must be continuously monitored, as increased relative humidity can cause the fertilizer to absorb excessive moisture and become unsuitable for use (Moore and González-León, 2020). The concentration of the main elements in the granulated NPK fertilizers produced under laboratory conditions was also determined to assess the compliance of the fertilizer composition with the specified formula (5–15–30). The analysis results of all samples varied slightly, and the following average values were obtained: 4.7% N, 14.9% P2O5, and 30.1% K2O, which confirm the composition of the target product.

3.3 Bacterial survival during the industrial production of NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers

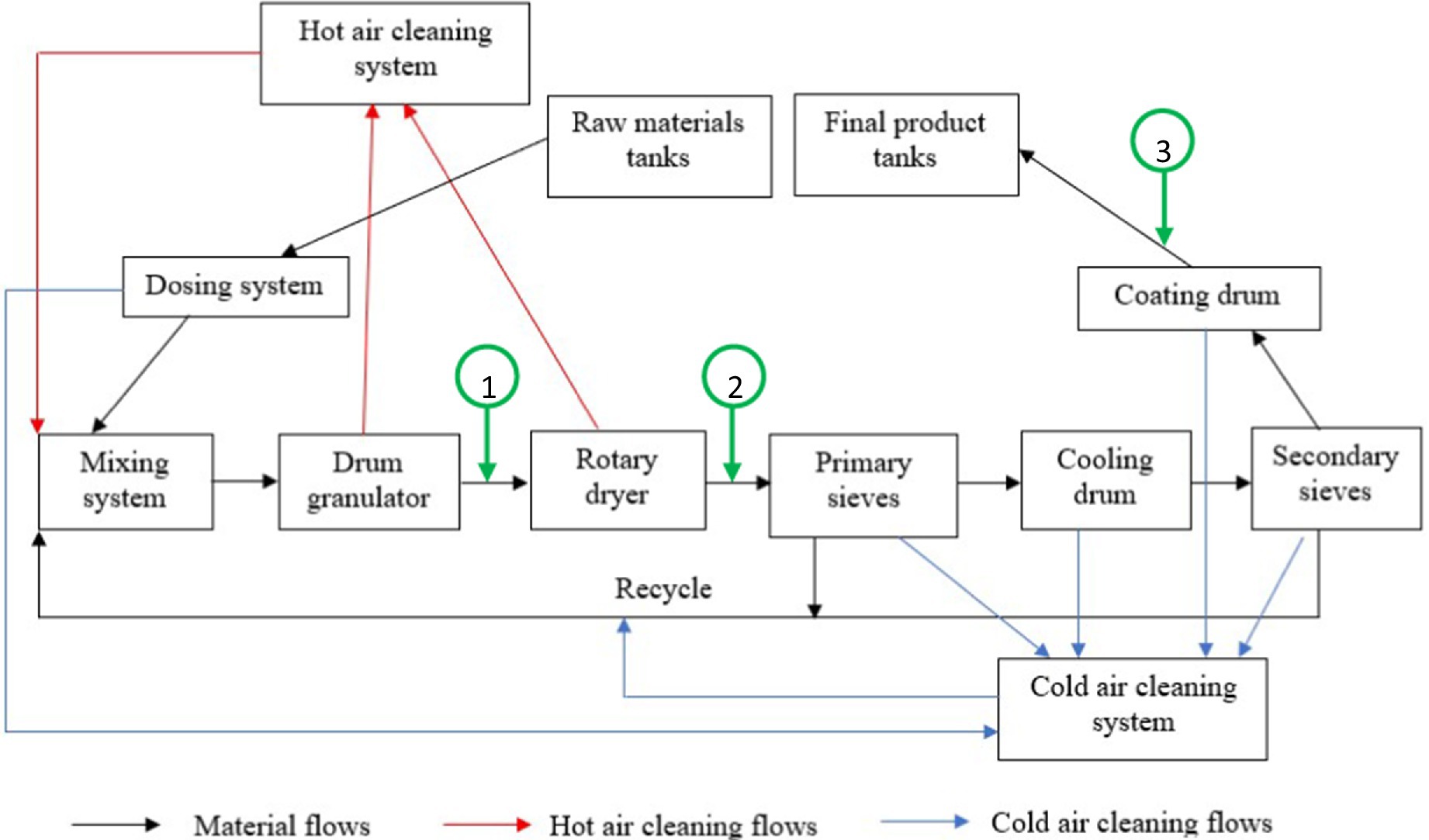

The results discussed show that, by using the wet granulation method and adding a bacterial preparation to the raw material mixture, it was possible to granulate NPK fertilizer with viable bacteria that meet the indicators of bulk fertilizers in accordance with EC Regulation 2003/2003 under laboratory conditions. Therefore, after evaluating the available data, trial granulation was carried out under real production conditions at a fertilizer production plant. Figure 3 presents a block diagram of the process line, showing the main equipment and the movement of three types of flows – materials, hot air, and cold air – throughout the entire production cycle. This flow management is essential for both technological efficiency and environmental protection. The technological process of granular fertilizer production integrates the stages of raw material preparation, granulation, drying, sieving, cooling, coating, and air cleaning. The process begins with the supply of raw materials from tanks, followed by a mixing system designed to homogenize the components. The resulting mixture is directed to a drum granulator, where granules are formed. In the next stage, the granules enter a rotary dryer, where they are dried with hot air. After being used, hot air is collected and cleaned through a hot air cleaning system, thereby ensuring compliance with environmental requirements. The dried granules pass through primary sieves, where they are separated into a commercial fraction (2–5 mm) and a recycle fraction (less than 2 mm), the latter being returned to the mixing system for further processing.

Figure 3. Schematic block diagram of NPK fertilizer production with main processes, flows and sample control points: 1 – after the granulator; 2 – after the dryer 3 – after the coating drum.

The selected commercial granules enter cooling sieves, where they are cooled with cold air. This is followed by secondary sieving, and the finished product is further processed with wax in a coating drum to improve its physical properties and storage stability. The final product is then stored in containers designated for the final product. Cold air used in the cooling, sieving, and coating processes is collected through a cold air cleaning system, thus reducing the emission of dust and other particulates into the environment.

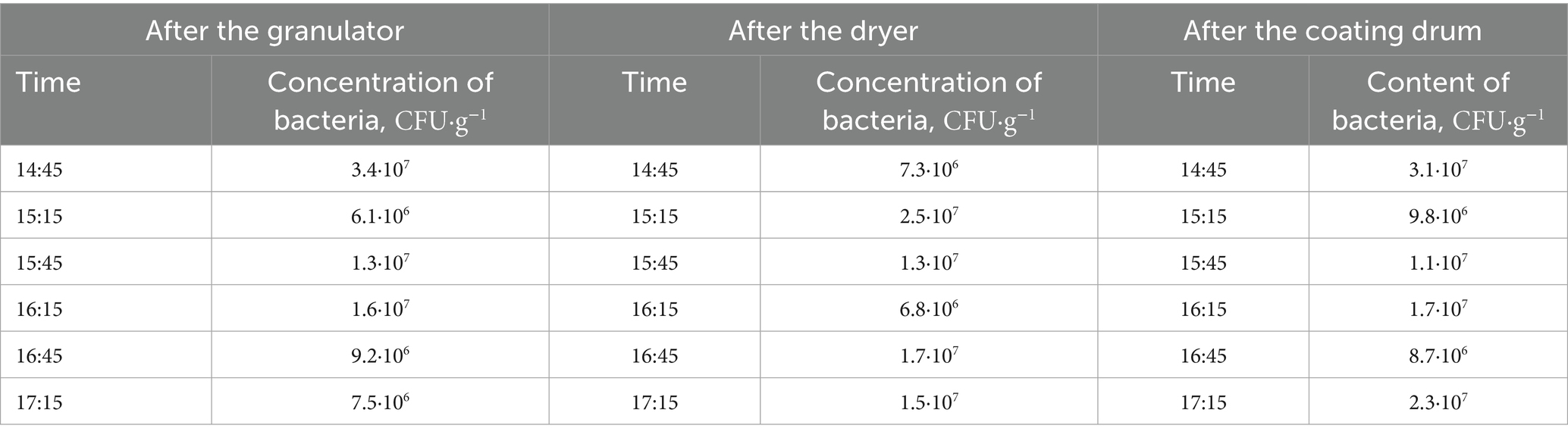

Since temperature fluctuations occur during the process of granulating NPK fertilizers under industrial conditions, and other external factors influence the process, the activity of bacteria in the product granulated under industrial conditions was additionally analyzed. For this analysis, samples were taken at three points along the technological line: after the granulator; from the belt conveyor after the dryer, where the highest temperature (300–350 °C) is maintained for 15–20 min; and from the belt conveyor after the coating drum, where the final product is already located. The results obtained from the bacterial survival study are presented in Figure 1 and Table 3.

Table 3. Viable bacterial counts at different processing stages and time points in NPK 5–15– 30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizer samples.

To manufacture bioinoculants, microbial biomass must be produced in high concentrations under aseptic conditions, typically reaching a minimum of 1·108 CFU·mL−1 (this means that 0.1 mL of the solution contains approximately 1·107 CFU, i.e., 10 million viable cells). According to a patent description, application rates of Bacillus subtilis inoculants range from 1·106 to 5·1015 CFU·ha−1, with an optimal spore density falling between 1·107 and 1·1011 CFU·ha−1 (Seevers et al., 2014) Literature sources recommend applying Bacillus spp. to soil at concentrations of approximately 1·107 CFU·g−1 of soil to ensure effective colonization (Qian et al., 2023; Mawarda et al., 2022). Additionally, healthy arable soils typically contain bacterial populations ranging from 106 to 109 CFU·g−1, suggesting that inoculation should aim to reach or exceed the upper end of this natural range (TerraSoil, 2024).

Based on the data presented in Table 3 and the visual information in Figure 1, it can be concluded that the bacteria survived with a mortality rate of 10–15%.

Since such bacterial viability results are in line with the recommendations, it can be assumed that the industrial wet granulation process, in which the bacteria are introduced into the raw material mixture, is suitable for producing various fertilizers with the bioactive additive Fosfix.

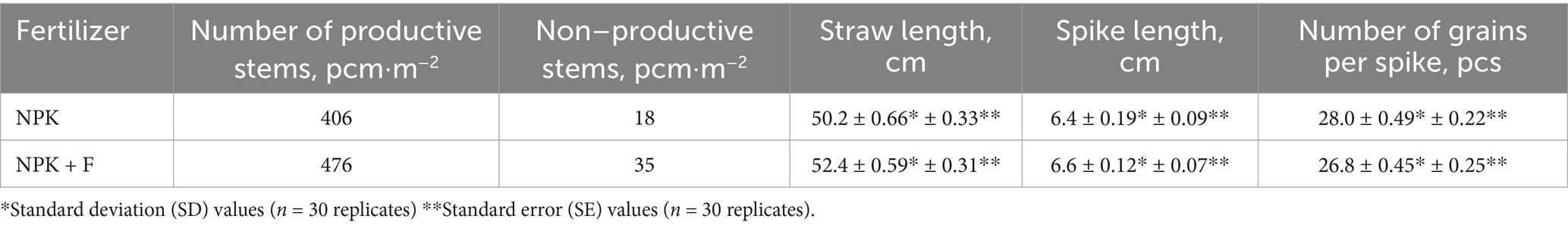

3.4 The effect of a biological additive on the growth and properties of spring wheat

Further studies on industrial granular NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers were conducted to determine the effectiveness of Bacillus sp. bacteria. The research took place at the Rumokai testing station, using Triso variety of spring wheat for the study. Fertilization was carried out using the same rates (350 kg·ha−1) of two fertilizer types: NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn (NPK) and NPK 5–15– 30 + S + Zn + Fosfix (NPK + F). To simulate real conditions of wheat cultivation, herbicides (MCPA super + Sekator) and an additional application of ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) at a rate of 251 kg·ha−1 were also used.

The research results, presented in Table 4, demonstrate that the biological additive Fosfix increased the tillering capacity of spring wheat. The number of productive stems increased from 406 pcm·m−2 in the NPK group to 476 pcm·m−2 in the NPK + F group (17.2%). The number of nonproductive stems increased by 94.4%. Although this increase is higher in the NPK + F group, the increase in the number of productive stems indicates a positive effect. In addition, plants fertilized with NPK + F were generally taller (52.4 cm compared to 50.2 cm) and had slightly longer spikes (6.6 cm compared to 6.4 cm) than the NPK group. The observed increases in straw and spike length were consistent and showed low variability (values of SD ≤ 0.7 cm, and values of SE ≤ 0.35 cm), indicating reliable measurements. The number of grains per spike decreased slightly (26.8 for NPK + F compared to 28.0 for NPK), but the change was small in relation to the variation among replicates.

Similar findings were obtained in a study on the effects of NPK and biofertilizers on the growth, yield, and nutrient uptake of wheat, where a microbial consortium consisting of Azotobacter chroococcum, Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas fluorescens, applied with 75% of the recommended fertilizer dose, significantly enhanced wheat germination, plant growth, nutrient uptake, and yield parameters (Parunandi et al., 2023).

C. Joshi reported that a microbial consortium consisting of Azotobacter, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas spp., applied with 50% of the recommended NPK dose, significantly increased wheat plant height (115.6 cm), tiller number (119.1), and grains per spike (47.3), resulting in the highest grain yield (55.7 kg·ha−1) and nutrient uptake, thus confirming the positive effect of biofertilizers on crop performance under reduced chemical input (Joshi et al., 2024).

After using the biological additive, the yield of spring wheat grains increased by 0.2 t·ha−1 and the weight of 1,000 grains by 0.21 g. The observed increases in grain yield and 1,000 grain mass were consistent and showed low variability (SD ≤ 0.15 t·ha−1 for yield and ≤0.5 g for 1,000 grain mass), indicating a modest positive effect of the additive, while the variations in protein, starch, and gluten content were small in relation to the variability among replicates, suggesting no significant impact on grain quality (Table 5).

Our study observed an increase in grain yield (~5%) and 1,000-grain weight (~0.5%) after application of NPK + F, which is consistent with results from the region of Northwest China, which showed that average increases in grain yield can be achieved using other fertilization technologies. Straw strip mulching increased yield by 13.4%, while whole-ground plastic film mulching increased it by 21.2%. The increase in 1000-grain weight ranged from 1.8 to 5.5%, and minimal changes in protein, starch, and gluten content did not indicate significant differences in grain quality parameters (Chai et al., 2025). However, this contrasts with the findings of Kayin et al. (2015), who noted an increase in protein and gluten content with Bacillus subtilis application, potentially due to differences in bacterial strains, environmental conditions, or fertilizer formulations.

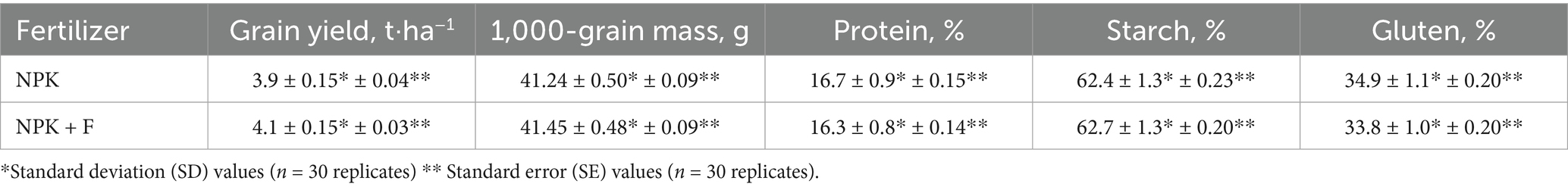

3.5 The effect of a biological additive on the growth and properties of sugar beet

Following the analysis of the influence of NPK 5–15–30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizers on spring wheat, a different brand of fertilizers, NPK 12–11–22 + Na + S + B (NPK) and NPK 12–11– 22 + Na + S + B + Fosfix (NPK + F), was produced by a fertilizer industry company. These fertilizers were then tested at the Rumokai testing station of the LAMMC branch using sugar beets of Severa KWS variety.

Fertilization was carried out in two ways: using a fertilizer rate of 700 kg·ha−1 of NPK and 163 kg·ha−1 of NH4NO3, and using a fertilizer rate of 700 kg·ha−1 of NPK + F and 163 kg·ha−1 of NH4NO3. To maintain realistic growing conditions, herbicides (Kontact, Ethosat, Goltix, and Poweroil), the insecticide Proteus, and the fungicide Maredo were also applied during the sugar beet growing season. The obtained research data are presented in Tables 6–8.

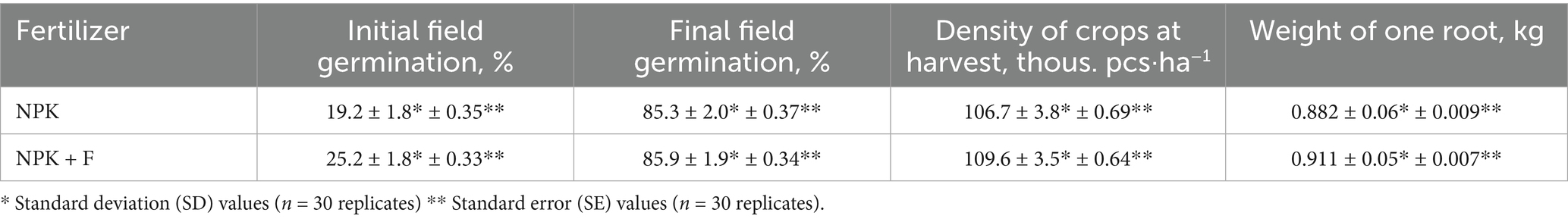

The data presented in Table 6 indicate that the use of the biological additive Fosfix had a positive effect on the germination and plant density of sugar beet. In fields fertilized with NPK + F, initial germination was higher (25.2% ± 1.8 SD; ±0.33 SE) compared to the NPK variant (19.2% ± 1.8 SD; ±0.35 SE), and this difference exceeded the standard error, indicating a reliable increase. Although final germination was similar in both variants (85.3% for NPK and 85.9% for NPK + F), the NPK + F variant exhibited a slightly higher plant density at harvest (109.6 thousand units·ha−1) compared to the NPK variant (106.7 thousand units·ha−1). Furthermore, the average weight of one root was higher in the NPK + F variant (0.911 kg) than in the NPK variant (0.882 kg). These findings align with other studies that observed a significant increase in root dry matter and overall root yield of sugar beet when biofertilizers were applied, highlighting the positive impact of microbial inoculants on sugar beet root biomass development (Amin et al., 2013; Çınar and Ünay, 2021). The observed increase in initial field germination with NPK + F in our study (~31%) is notably higher than the gains reported in studies using bacterial seed treatments, which typically improved germination by about 10–17% under comparable fertilizer regimes, thus underscoring the strong positive effect of the biological additive in our conditions (Demyanyuk et al., 2020).

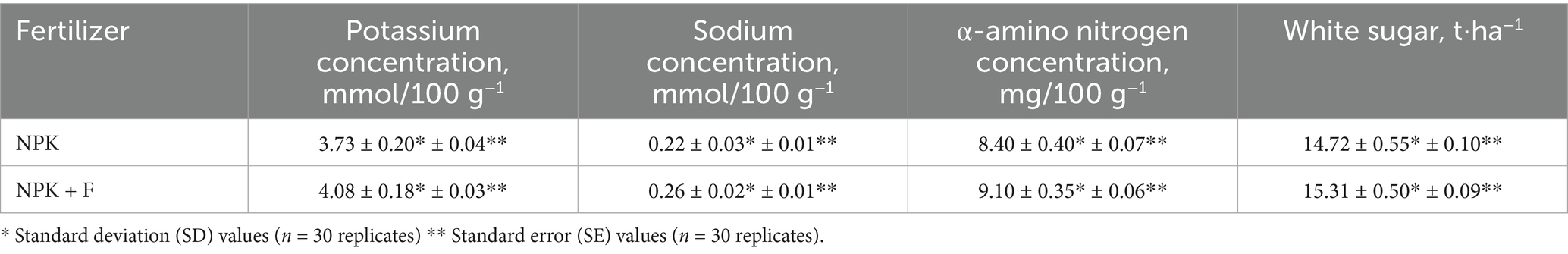

The yield increase of root crops using NPK 12–11–22 + Na + S + B fertilizers with the biological additive Fosfix was 5.78 t·ha−1. The yield increase of root crops with standard sugar content was 5.6 t·ha−1, and the yield increase of biological sugar content was 0.89 t·ha−1. However, sugar content decreased by 0.17% (Table 7). The obtained root crop yields (94.07 t·ha−1for NPK and 99.85 t·ha1 for NPK + F) fall within the upper range of values reported in literature under enhanced fertilization regimes, though they remain below the maximum yield levels of ~132 t·ha−1achieved under optimized potassium fertilization (Xie et al., 2022). These differences exceeded the standard error (SE ≤ 0.1 t·ha−1), indicating that the observed increases are statistically reliable.

Similarly, the biological sugar yield observed in our study (17.23–18.12 t·ha−1) is comparable to the 11–18 t·ha−1 range reported by Varga et al. (2021) under varying nitrogen fertilization and crop density treatments, confirming that the addition of Fosfix produces a competitive impact on sugar beet root and sugar yield. By contrast, the sugar content remained high in both treatments (~18%), exceeding values commonly reported in similar studies (14.9–15.6%), which indicates that the additive improved yield parameters without compromising accumulation of sucrose.

According to the data presented in Tables 7, 8, it can be concluded that incorporating the bacterial additive Fosfix into NPK 12–11–22 fertilizerimproved many indicators of sugar beet quality compared to the treatment without the additive.

The white sugar yield increased from 14.7 to 15.3 t·ha−1, and this difference exceeded the standard error (SE ≤ 0.1 t·ha−1), indicating a statistically reliable effect. Root quality parameters such as potassium, sodium, and α-amino nitrogen also showed slight increases, but all values remained within the typical ranges reported by Varga et al. (2021). Similarly, the white sugar yield in our study (14.7–15.3 t·ha−1) aligns with the 12–16 t·ha−1 interval described by Xie et al. (2022), confirming that the biological additive improved productivity without compromising root quality.

Summarizing the results on the influence of the biological preparation Fosfix on the quality parameters of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Triso and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Severa KWS, it can be stated that this preparation, based on Bacillus sp. bacteria, had a more pronounced effect on sugar beet indicators, particularly improving field germination, root yield, and white sugar output. This can be explained by different yield targets. In the case of sugar beet, the harvested product is the root crop, which is directly located in the rhizosphere; therefore, any improvement of the root zone (e.g., P/K mobilization, hormone production) directly contributes to the yield. In contrast, the final product of wheat is grain, which is often limited by light, heat, or moisture factors, so improvements in the rhizosphere do not always fully translate into higher grain yield.

Furthermore, the microbiota of sugar beet is usually weakly or not at all mycorrhizal, making it more dependent on the availability of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria such as Bacillus sp. Wheat, on the other hand, often already hosts an abundant natural microbiota, so the additional effect of Bacillus sp. is typically smaller than in sugar beet.

4 Conclusion

Laboratory experiments demonstrated that optimal conditions for granulating NPK 5–15– 30 + S + Zn + Fosfix fertilizer were achieved when the raw material mixture contained 15–16.5% moisture and up to 40% return material. Under these conditions, strong and uniform granules were produced, and the biological additive Fosfix did not interfere with the granulation process. Importantly, Bacillus sp. bacteria remained viable throughout wet granulation, indicating that this technology can be successfully scaled to industrial production without compromising product quality.

Field trials revealed that the effect of Fosfix was crop-specific. In spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L. Triso), the additive increased the number of productive tillers, plant height, and spike length, leading to modest gains in grain yield (+0.2 t·ha−1) and thousand kernel weight (+0.21 g), while quality parameters such as protein and gluten content were slightly reduced. In sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. severa KWS), the additive showed a stronger and more consistent effect: initial field germination, root weight, plant density, and total root yield all increased, resulting in an additional 5.78 t/ha of roots and 0.89 t·ha−1 of biological sugar yield, without compromising sucrose accumulation.

Overall, these results indicate that incorporating Bacillus-based bioadditives into compound mineral fertilizers is a feasible and effective strategy. By maintaining bacterial viability during granulation and improving crop productivity under field conditions, such fertilizers combine technological robustness with agronomic benefits. The stronger effect observed in sugar beet suggests that root crops, which are more directly influenced by rhizosphere processes, may benefit more than cereals. In this way, Fosfix-enriched fertilizers contribute both to sustainable crop intensification and to improving soil–plant interactions, aligning with the goals of environmentally friendly and efficient agriculture. Future research should focus on optimizing the efficiency of bacterial utilization and ensuring their viability and activity during incorporation into fertilizers, in order to maximize both agronomic effectiveness and sustainability.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

RŠ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the researchers at the Rumokai Experimental Station, a branch of the Lithuanian Research Center for Agriculture and Forestry (LAMMC), for their assistance in conducting the field trials and analyzing the obtained results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agake, S.-i., Ohwaki, Y., Kojima, K., Yoshikawa, E., Artigas Ramirez, M. D., Bellingrath-Kimura, S. D., et al. (2022). Biofertilizer with Bacillus pumilus TUAT1 spores improves growth, productivity, and lodging resistance in forage rice. Agronomy 12:2325. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12102325

Albadarin, A. B., Lewis, T. D., and Walker, G. M. (2017). Granulated polyhalite fertilizer caking propensity. Powder Technol. 308, 193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2016.12.002

Amin, G. A., Elsayed, E. A. E. B., and Afifi, M. H. M. (2013). Root yield and quality of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) in response to biofertilizer and foliar application with micronutrients. World Appl. Sci. J. 27, 1385–1389. doi: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.27.11.13732

Ammar, E. E., Rady, H. A., Khattab, A. M., Amer, M. H., Mohamed, S. A., Elodamy, N. I., et al. (2023). A comprehensive overview of eco-friendly bio-fertilizers extracted from living organisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 113119–113137. doi: 10.1007/s11356023-30260-x

ASTM International. (2020). ASTM E104-20a: standard practice for maintaining constant relative humidity by means of aqueous solutions. ASTM International Standard. Available online at: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/astm/d696120b-b490-4eb8-a817-6000a9b72fbb/astme104-20a.

Baird, R. J., Kabiri, S., Degryse, F., da Silva, R. C., Andelkovic, I., and McLaughlin, M. J. (2023). Hydrophobic coatings for granular fertilizers to improve physical handling and nutrient delivery. Powder Technol. 424:118521. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118521

Bargaz, A., Lyamlouli, K., Chtouki, M., Zeroual, Y., and Dhiba, D. (2018). Resources for improving fertilizers efficiency in an integrated plant nutrient management system. Front. Microbiol. 9:1606. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01606

Bhaduri, D., Sihi, D., Bhowmik, A., Verma, B. C., Munda, S., and Da, B. (2022). A review on effective soil health bio-indicators for ecosystem restoration and sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 13:938481. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.938481

Bioenergy LT. (2018) Homepage. Bioenergy LT. Available online at: https://www.bioenergy.lt/.

Chai, Y., Li, Y., Li, R., Chang, L., Cheng, H., Ma, J., et al. (2025). Increased spike density and enhanced vegetative growth as primary contributors to improvement of dryland wheat yield via surface mulching. Field Crop Res. 326:853. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2025.109853

Çınar, V. M., and Ünay, A. (2021). The effects of some biofertilizers on yield, chlorophyll index and sugar content in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris var. saccharifera L.). J. Agric. Fac. Ege Univ. 58, 163–170. doi: 10.20289/zfdergi.714633

Cotrufo, M. F., and Lavallee, J. M. (2022). Chapter one – soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: a synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration. Adv. Agron. 172, 1–66. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2021.11.002

Demyanyuk, O. S., Mudrak, O. V., Masloyid, A. P., and Mudrak, G. V. (2020). Ecologically comparative effect of bacterial preparations on field germination of sugar beets. Ecology 2:208810. doi: 10.33730/2310-4678.2.2020.208810

Díaz-Rodríguez, A. M., Parra Cota, F. I., Cira Chávez, L. A., García Ortega, L. F., Estrada Alvarado, M. I., Santoyo, G., et al. (2025). Microbial inoculants in sustainable agriculture: advancements, challenges, and future directions. Plants 14:191. doi: 10.3390/plants14020191

Dos Reis, G. A., Martínez-Burgos, W. J., Pozzan, R., Pastrana Puche, Y., Ocán-Torres, D., de Queiroz Fonseca Mota, P., et al. (2024). Comprehensive review of microbial inoculants: agricultural applications, technology trends in patents, and regulatory frameworks. Sustainability 16:8720. doi: 10.3390/su16198720

EU CAP Network. (2023). Eco-schemes: evolving the common agricultural policy’s green architecture. Policy insights. Available online at: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/202312/policy-insights-eco-schemes-evolving-the-ca-ps-green-architecture.pdf

EUR-Lex. (2019). Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products. Access to European Union law. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009.

European Commission. (2025). Food, bioeconomy, natural resources, agriculture and environment. Horizon Europe work Programme 2025, decision C (2025) 2779 of 14 may 2025. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/horizon/wpcall/2025/wp-9-food-bioeconomy-natural-resources-agriculture-and-environment_horizon2025_en.pdf.

Fan, X., Zhou, X., Chen, H., Tang, M., and Xie, X. (2021). Cross-talks between macro- and micronutrient uptake and signalling in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12:663477. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.663477

FAO. (2021) The role of technology. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/4/y3557e/y3557e09.htm#TopOfPage

Fulton, J., and Port, K. (2016). Physical properties of granular fertilizers and impact on spreading. Ohioline Fact Sheet FABE-550.1, College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences, Ohio State University Extension. Available online at: https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/fabe-5501.

Fusco, G. M., Nicastro, R., Rouphael, Y., and Carillo, P. (2022). The effects of the microbial biostimulants approved by EU regulation 2019/1009 on yield and quality of vegetable crops. Foods 11:2656. doi: 10.3390/foods11172656

Geisseler, D., and Scow, K. M. (2014). Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 75, 54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.03.023

Gonzalez, J. M., and Aranda, B. (2023). Microbial growth under limiting conditions—future perspectives. Microorganisms 11:1641. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071641

Hidayat, J. P., Kusuma, M. A., Putri, N. A., and Hariyadi, A. (2025). Granulator performance for urea granule quality: a study on material balance and recycle seed ratio. Int. J. Mar. Eng. Innov. Res. 10:562. doi: 10.12962/j25481479.v10i1.22562

Ishfaq, M., Wang, Y., and Xu, J., and others (2023). Improvement of nutritional quality of food crops with fertilizer: a global meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43:74. doi: 10.1007/s13593023-00923-7

Joshi, C., Zala, V., Pandya, A., Zala, H., Zala, V., Zala, P., et al. (2024). The effect of commercial NPK consortia (Ami NPK) on wheat productivity and nutrient uptake. Acta Sci. Microbiol. 7:1446. doi: 10.31080/ASMI.2024.07.1446

Kapinusova, G., Lopez Marin, M. A., and Uhlik, O. (2023). Reaching unreachables: obstacles and successes of microbial cultivation and their reasons. Front. Microbiol. 14:1089630. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1089630

Kayin, G. B., Öztüfekçi, S., Akın, H. F., Karaata, E. U., Katkat, A. V., and Turan, M. A. (2015). Effect of Bacillus subtilis Ch-13, nitrogen and phosphorus on yield, protein and gluten content of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Agric. Fac. Ege Univ. 29, 19–28.

Kindangen, J. G., Kairupan, A. N., Joseph, G. H., Rawung, J. B. M., and Indrasti, R. (2023). Sustainable agricultural development through agribusiness approach and provision of location specific technology in North Sulawesi. E3S Web of Conf. 444:01003. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202344401003

Kumar, S., Diksha,, Sindhu, S. S., and Kumar, R. (2021). Biofertilizers: an ecofriendly technology for nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 3:100094. doi: 10.1016/j.crmicr.2021.100094

Lillerand, T., Virro, I., Maksarov, V. V., and Olt, J. (2021). Granulometric parameters of solid blueberry fertilizers and their suitability for precision fertilization. Agronomy 11:1576. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11081576

Loiko, N., and Islam, M. N. (2024). Plant–soil microbial interaction: differential adaptations of beneficial vs. pathogenic bacterial and fungal communities to climate-induced drought. Agronomy 14:1949. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14091949

Macák, M., and Krištof, K. (2016). The effect of granulometric structure and moisture of fertilizer on its static strength. Res. Agric. Eng. 62, S1–S7. doi: 10.17221/31/2016-RAE

Mącik, M., Gryta, A., and Frąc, M. (2020). Biofertilizers in agriculture: an overview on concepts, strategies and effects on soil microorganisms. Adv. Agron. 162, 31–87. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2020.02.001

Masquelier, C., Petersen, C., and Lobley, M. (2025). When farmers and scientists collaborate, biodiversity and agriculture can thrive – here’s how. The conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/when-farmers-and-scientists-collaborate-biodiversity-andagriculture-can-thrive-heres-how-250333.

Mawarda, P. C., Mallon, C. A., Le Roux, X., Van Elsas, J. D., and Falcão Salles, J. (2022). Interactions between bacterial inoculants and native soil bacterial community: the case of sporeforming Bacillus spp. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 98:121. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiac121

Mažylytė, R., Kaziūnienė, J., Orola, L., Valkovska, V., Lastauskienė, E., and Gegeckas, A. (2022). Phosphate solubilizing microorganism Bacillus sp. MVY-004 and its significance for biomineral fertilizers’ development in agrobiotechnology. Biology 11:254. doi: 10.3390/biology11020254

Mefteh, H., Kebaïli, O., Oucief, H., Berredjem, L., and Arabi, N. (2013). Influence of moisture conditioning of recycled aggregates on the properties of fresh and hardened concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 54, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.009

Moore, L. R., and González-León, J. A. (2020). Solving moisture absorption challenges. World Fertilizers. Available online at: https://fertiliser-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Solving-Moisture-Absorption-Challenges-World-Fertilizer-NovDec-2020.pdf.

National Research Council. (2002). Committee on environmental impacts associated with commercialization of transgenic plants. Environmental effects of transgenic plants: The scope and adequacy of regulation. National Academies Press. Available online at: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/10258/environmental-effects-of-transgenic-plants-thescope-and-adequacy-of.

Nikolaidis, N. P., and Bidoglio, G. (2013). Soil organic matter dynamics and structure. Sustain. Agric. Rev. 12, 175–119. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5961-9_6

Parunandi, S. S., Murumkar, D. R., Navale, A. M., and Shelke, S. R. (2023). Unveiling the consortial role of heterotrophic nitrogen fixing, phosphate solubilizing and potash mobilizing bacteria: augmenting soil health, and growth and yield of wheat crop (T. aestivum) through integrated nutrient management strategy. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 12, 138–167. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2023.1211.013

Pisante, M., Stagnari, F., and Grant, C. A. (2012). Agricultural innovations for sustainable crop production intensification. Ital. J. Agron. 7:40. doi: 10.4081/ija.2012.e40

Posmyk, M. M., and Szafrańska, K. (2016). Biostimulators: a new trend towards solving an old problem. Front. Plant Sci. 7:748. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00748

Qian, J., Wang, Y., Hu, Z., Shi, T., Wang, Y., Ye, C., et al. (2023). Bacillus sp. as a microbial cell factory: advancements and future prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 69:108278. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108278

Rashid, M. I., Mujawar, L. H., Shahzad, T., Almeelbi, T., Ismail, I. M., and Oves, M. (2016). Bacteria and fungi can contribute to nutrients bioavailability and aggregate formation in degraded soils. Microbiol. Res. 183, 26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.007

SAI Platform. (2015). Partnering with farmers towards sustainable agriculture: overcoming the hurdles and leveraging the drivers. Lausanne, Switzerland: SAI Platform. Available online at: https://saiplatform.org/uploads/SAI_Platform_publications/SAI_Platform_Farmer_Partnership_Practitioners_Guide-_May_2015.pdf.

Seevers, K., Reinot, E., and Jabs, T. (2014). Synergistic compositions comprising a Bacillus subtilis strain and a pesticide. Australian patent AU 2014233858 C1. Available online at: https://patents.google.com/patent/AU2014233858C1/en.

Sigtryggsson, C., Hamnér, K., and Kirchmann, H. (2020). Laboratory studies on dissolution of nitrogen fertilizers by humidity and precipitation. Agric. Environ. Lett. 5:16. doi: 10.1002/ael2.20016

Šimanský, V., Jonczak, J., Horváthová, J., Igaz, D., Aydın, E., and Kováčik, P. (2022). Does longterm application of mineral fertilizers improve physical properties and nutrient regime of sandy soils? Soil Tillage Res. 215:105224. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2021.105224

Singh, K., Gupta, S., and Singh, A. P. (2024). Nutrient–nutrient interactions governing underground plant adaptation strategies in a heterogeneous environment. Plant Sci. 342:112024. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112024

Singh, T. C., Rathinaguru, E., Nakhate, P. S., Kumar, P. P., Verma, L. P., Malviya, S., et al. (2024). Impact of soil organic matter on soil dynamics: a comprehensive review with a focus on Indian contexts. Int. J. Res. Agron. 7, 914–920.

Sinkevičienė, J., and Pekarskas, J. (2019). Bioproduktų poveikis ekologiškai auginamiems žieminiams kviečiams [the effect of bioproducts on organically grown winter wheat]. Žemės Ūkio Moksl. 26, 13–21. Available online at: https://lmaleidykla.lt/ojs/index.php/zemesukiomokslai/article/view/3965

Stamenkovic, S., and Beškoski, V. (2018). Microbial fertilizers: a comprehensive review of current findings and future perspectives. Spanish J. Agric. Res. 16:e09R01. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2018161-12117

TerraSoil. (2024). Understanding bacteria to fungi ratios in soil health. Available online at: https://www.terrasoil.eu/news/bacteria-to-fungi-ratios---a-terrasoiloverview?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Transport and Environment. EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 – bringing nature back into our lives. Position paper (2020). Available online at: https://www.akeuropa.eu/sites/default/files/2020-10/EN_EUBiodiversit%C3%A4tsstrategie%202030.pdf.

Turner, B. L. (2021). Soil as an archetype of complexity: a systems approach to improve insights, learning, and management of coupled biogeochemical processes and environmental externalities. Soil Syst. 5:39. doi: 10.3390/soilsystems5030039

Ulusoy, U. (2023). A review of particle shape effects on material properties for various engineering applications: from macro to nanoscale. Minerals 13:91. doi: 10.3390/min13010091

Varga, M., Pepó, P., Nagy, J., and Kovács, G. (2021). Sugar beet root yield and quality with leaf seasonal dynamics in different crop year types. Agriculture 11:407. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11050407

Wei, X., Xie, B., Wan, C., Song, R., Zhong, W., Xin, S., et al. (2024). Enhancing soil health and plant growth through microbial fertilizers: mechanisms, benefits, and sustainable agricultural practices. Agronomy 14:609. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14030609

Xie, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, J., Wang, H., Lv, X., and Yu, J. (2022). Potassium determines sugar beet yield and sugar content. Sustainability 14:12520. doi: 10.3390/su141912520

Xin, M., Jiang, Z., Song, Y., Cui, H., Kong, A., Chi, B., et al. (2023). Compression strength and critical impact speed of typical fertilizer grains. Agriculture 13:2285. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13122285

YARA. (2025). Crop nutrition. Fertilizer handling and safety. Physical properties of fertilizers. Available online at: https://www.yaracanada.ca/crop-nutrition/fertilizer-handling-and-safety/physical-properties-offertilizers/.

Yokamo, S., Irfan, M., Huan, W., Wang, B., Wang, Y., Ishfaq, M., et al. (2023). Global evaluation of key factors influencing nitrogen fertilization efficiency in wheat: a recent meta-analysis (2000–2022). Front. Plant Sci. 14:1272098. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1272098

Yusuf, A., Li, M., Zhang, S.-Y., Odedishemi-Ajibade, F., Luo, R.-F., Wu, Y.-X., et al. (2025). Harnessing plant–microbe interactions: strategies for enhancing resilience and nutrient acquisition for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1503730. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1503730

Zaib, M., Zubair, M., Aryan, M., Abdullah, M., Manzoor, S., Masood, F., et al. (2023). A review on challenges and opportunities of fertilizer use efficiency and their role in sustainable agriculture with future prospects and recommendations. Curr. Res. Agric. Farming 4, 1–14. doi: 10.18782/2582-7146.201

Zapka, O. (2023). Biologicals: what the perspectives are. DLG – German agricultural society. Available online at: https://www.dlg.org/en/magazin/knowledge-skills/biologicals-what-the-perspectives-are.

Zhao, J., Xie, X., Jiang, Y., Li, J., Fu, Q., Qiu, Y., et al. (2024). Effects of simulated warming on soil microbial community diversity and composition across diverse ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 911:168793. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168793

Keywords: bio-fertilizers, microorganisms, granulation technology, soil, agricultural efficiency, Bacillus sp.

Citation: Šlinkšienė R and Grodickas M (2025) A biological additive in granulated mineral compound fertilizer improves productivity of spring wheat and sugar beet. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1680939. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1680939

Edited by:

Naïma El Ghachtouli, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, MoroccoReviewed by:

Mohamed Ferioun, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, MoroccoKhadija El Moustaqim, Ibn Tofail University, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Šlinkšienė and Grodickas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rasa Šlinkšienė, cmFzYXNsaUBrdHUubHQ=

†Present address: Marijus Grodickas, UAB “Fertis”, Kaunas, Lithuania

Rasa Šlinkšienė

Rasa Šlinkšienė Marijus Grodickas†

Marijus Grodickas†