- Department of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, Aydin Adnan Menderes University, Aydin, Türkiye

This study aimed to identify consumers in Türkiye's attitudes toward consuming cultured beef, a new and sustainable food product, their willingness to pay, and the factors influencing these consumption. A face-to-face survey was conducted with 386 individuals. In the study, the Critic method was used to determine the sensory factors in consumers' traditional beef consumption preferences, and the fuzzy paired comparison method was used to rank the priorities of the reasons for not consuming cultured meat. In addition, consumers' desire to consume cultured beef was determined by the conditional evaluation method, and the general price they wanted to purchase was determined by the lower bound mean method. Multidimensional scaling was used to create perception maps of consumers, and multiple correspondence analysis were used to determine consumption preferences according to demographic characteristics. A significant portion of participants were initially reluctant to consume cultured beef. The reluctant group had a higher tendency to fear consuming new foods (food neophobia) than the willing group. However, attitudes toward cultured beef consumption changed when different alternatives were presented and were positively influenced by the social environment, market availability, and price of the product. Consumers' willingness to pay for this product was $13.716/kg. At this price threshold, a significant portion of the population was willing to accept the product (29.27%). The consumer profile that wants to buy a product when its price drops is composed of male, middle-income and middle-aged people. Health concerns and taste expectations are the most significant sensory barriers to consumption motivation. The order of importance attributed to these factors varied by gender. The results of this study will guide the success of cultured meat, an alternative food product.

1 Introduction

It is thought that in the near future, humanity will experience significant problems in accessing food (Grafton et al., 2015). The most important reason for this is population growth, consumption patterns and insufficient animal and agricultural production. Moreover, research has shown that there is an upward trend in global meat consumption, especially in developing economies with fast-growing incomes (Whitton et al., 2021; Wang, 2022).

It is estimated that to meet world food demand by 2050, meat production will need to be increased to approximately 110 million tons (Van Der Weele and Tramper, 2014). Due to limited arable land and water resources, it is thought that it is difficult to meet the increasing demand for meat with traditional production methods (Biscarra-Bellio et al., 2023). In addition, animal agriculture is thought to cause a number of critical global problems, including high greenhouse gas emissions, infectious diseases and the depletion of freshwater resources and land (Bellarby et al., 2013; Bhat et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2020; Kozicka et al., 2023). Furthermore, research has highlighted that using animals as food products raises societal concerns about their rights and welfare (Fernandes et al., 2019; Alonso et al., 2020).

A variety of issues concerning the rapid increase in the demand for animal protein, the limited resources available to producers, the population density, animal welfare and global warming have led scientists to seek alternative solutions. One solution to ensure the sustainability of protein demand could be the consumption of cultured meat (Moritz et al., 2015; Siddiqui et al., 2022a, 2025). This product may be called “in vitro meat,” “cell-based meat,” “artificial meat” or “cultivated meat.” This product is produced by extracting cells from the animal through a harmless biopsy and converting them into meat cells. In this research, what is meant by artificial meat or cultured meat is cultured beef.

Cultured meat is a new product that can shed light on sustainable production issues such as environmental protection, emissions, land use, animal welfare, and the prevention of slaughter. In fact, the number of scientific studies on this subject has increased significantly in recent years, suggesting that these issues will be discussed more in the future (Siddiqui et al., 2022c). The commercialization of cultured meat largely depends on consumers' attitudes toward these products (Mancini and Antonioli, 2020; Siddiqui et al., 2022b).

While information on the individual trends influencing the acceptance of cultured meat is valuable, evidence from cross-country studies suggests that consumers' responses vary widely (Lewisch and Riefler, 2023).

Therefore, there is a need for research on the perceptions of consumers in different geographical regions regarding cultured meat consumption (Bryant and Barnett, 2018; Tsvakirai, 2024).

Increasing interest in this product can help solve many different issues such as sustainable meat production, sustainable environment, animal welfare and epidemic diseases that can be transmitted from animals. Understanding consumer attitudes, knowledge, concerns, beliefs, preferences, and trust is crucial for further growth of the sustainable food market. Accurately understanding consumers' perceptions of sustainability-oriented changes in food production systems and the role of sensory factors in purchasing motivations will facilitate the marketing of the product. Furthermore, establishing the right pricing policy is essential to ensure the market share of this sustainable product. Unlike the literature, a net price request has been determined for this product. Additionally, a different technique was used in this study to determine consumers' willingness to pay for this product. Moreover, sensitive decision-making techniques were used to reveal consumers' perceptual attitudes toward the product.

In general, some of the consumer research on cultured meat has focused on environmental and animal welfare issues, some on the perception of naturalness, some on the willingness to purchase, some on the impact of cultural differences, and some on familiarity. The increasing trend in meat production and consumption in developing countries will pose a more serious problem in terms of the environment, global health and food security in the future. Research shows that more information is needed in this area, especially in developing countries (Bryant and Barnett, 2018). However, consumer perceptions of cultured meat in developing and Muslim countries remain unclear. As far as is known, there is not enough information in the literature about the perceptions of consumers and Muslims in Türkiye about cultured beef. Few studies appear in the literature (Gençer Bingöl and Agagündüz, 2025). As a developing country, consumer perception of this product is of great importance to the region. Additionally, the literature has not established a clear demand price for this product. This research has established a clear consumer expectation price for cultured meat, providing a different perspective from the literature. Finally, more sensitive decision-making techniques were used to reveal consumers' perceptual attitudes toward the product. This research provides important support to the literature in these aspects.

Therefore, this research aimed to reveal the attitudes of consumers in Türkiye toward consuming cultured beef, a new and sustainable alternative meat, willingness to pay and the factors affecting these. The research results have applications in many disciplines, including social and natural sciences, humanities, business and culinary arts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample selection

The main data analyzed in this research were obtained from survey forms. The survey participants were required to fulfill two criteria. The first was that they consumed beef, and the second was that they had never consumed cultured beef. Therefore, everyone who participated in the survey was first given a definition of artificial beef (cultured beef). The statement said, “Artificial beef (Cultured beef) is produced by growing cells taken from live cattle in the laboratory. This practice does not harm the cattle.” In Türkiye, cultured meat is produced in its plant-based form. However, cultured meat is not produced in a laboratory setting from cells taken from live cattle. Therefore, cell cultured meat production is not yet a licensed, commercialized, or supported activity in Türkiye. This research presents a hypothetical consumer market for this product.

This study was conducted in Izmir Province, located in the west of Türkiye and extending to the Aegean coast. Izmir is the third-largest city in Türkiye and represents a region in itself according to its code, TR31. Considering the city's population density, development level, status as a trade center and capacity to influence the market, it was selected as the research area.

With its strategic location on the Aegean Sea, Izmir is a major port city and commercial center in Türkiye. It also hosts trade fairs, congresses, and economic events. Furthermore, Türkiye's leading universities are located in the city. Therefore, Izmir, a cosmopolitan city that receives immigration from all cities, is an important center within Türkiye.

The sample volume formula used in this study was as follows (Newbold, 1995):

Here,

n: sample size

N: 4,479,525

p: probability level

σp represents the confidence interval (95% confidence interval, 1.96; σp: 0.05 for a 0.05 margin of error; σp: 0.02551). Probability (p) was taken as 50%.

The surveys were conducted face to face with 386 consumers. The survey work was completed between January 2024 and March 2025. Ethics committee approvals were obtained.

2.2 Critic method

In this study, the Critic method was used to weight the sensory criteria affecting the participants' beef consumption preferences. Consumers have consumed beef before and continue to buy it. Since consumers have not tasted cultured beef before, their opinions about conventional beef are evaluated in this section. Consumers' sensory expectations of conventional beef may also guide the development of cultured beef. That is why this section was included in the survey. The sample size of this section was 386 people.

This method can subjectively weight criteria and determine the relationship between them. Therefore, we chose to use it. A data set was created for a total of 6 different sensory criteria that may affect beef selection, which were determined by reviewing the literature. These encompassed the hardness, odor, texture, surface appearance, color and fat content. The sample for this portion of the research included all the survey participants (n = 386), and the method used can be outlined in five stages (Diakoulaki et al., 1995).

Stage 1: The creation of the decision matrix.

The decision matrix, denoted as Xij, was created.

X = [xij] is created, where:

i = 1, 2, …, 386 (participants)

j = 1, 2, …, 6 (criteria)

xij = the score of participant i for criterion j.

Stage 2: The normalization of the decision matrix.

The values were normalized so that they ranged between 0 and 1. Two different equations were used for maximization and minimization.

Stage 3: The creation of the relationship coefficient matrix. It is done to measure how independent or contradictory a criterion is with respect to others.

Where:

= mean of normalized values for criterion j

ρjk = correlation coefficient between criteria j and k.

Stage 4: The calculation of the Cj values.

The Cj values, which combined the contrast intensity and contradictions, were calculated.

Where:

σj = standard deviation of criterion j (contrast intensity)

1 – ρjk = conflict between criterion j and criterion k

Higher Cj → the criterion is more informative and independent.

Stage 5: The calculation of the criteria weights.

The criteria's weight values (wj) were obtained by dividing the Cj values of each criterion by the sum of the ck values of all the criteria.

All weights are between 0 and 1. Sum of weights = 1. Wj represents the relative importance of each sensory criterion for beef selection.

2.3 Fuzzy pairwise comparison

The choice of the participants not to consume cultured beef may have been due to reasons with very similar levels of importance. Therefore, uncertainty could have occurred when ranking the importance levels. In this study, the fuzzy paired comparison method was used as it is frequently implemented in consumer studies and explains importance levels with unclear boundaries more successfully than classical rankings.

While the degree of membership indicates whether or not a member belongs to a set in classical sets, it expresses the value of the change between 0 and 1 for each element in fuzzy sets. Thus, more realistic results can be achieved in determining the hierarchy of reasons why consumers do not consume the product. Accordingly, 6 criteria that may constitute the reasons why consumers do not consume cultured beef were determined to be used in survey studies by using the literature. The six criteria were disgust, expectations regarding the taste and texture of cultured beef, health concerns, beliefs, and ethical and moral values. Each consumer made 15 different comparisons for these six criteria. For example, consumers compared health concerns with disgust. Whichever criterion is marked closer is more important than the other criterion in the range of 0–1. If there is an equidistant (0.5) preference, the two criteria are equally important to the consumer.

This method has also been used in different consumer research (Ozcan and Çinar, 2024). With this method, the main factors that cause consumers not to want to consume cultured beef were listed. The sample size consisted of 354 people who did not want to consume cultured beef in the first stage.

The following steps can be followed (Boender et al., 1989).

First, pairwise comparisons were made to indicate individual preferences. For example, the difference in the degree of preference for criteria K and H, GKH, was measured according to the distance between them. The change in the value was between 0 and 1 for each element, and the total distance was equal to the following.

If GKH = 0.5, then K ≈ H; if GKH > 0.5, then K > H; and if GKH < 0.5, then K < H.

The number of pairwise comparisons of the criteria (C) was determined using C = [(Z.(Z – 1))/2]. In the formula, Z represents the number of preferred criteria. The factors were ordered from the most to the least influential according to their weight. The degree of preference, Gcr, was obtained for each pairwise comparison, with the formula calculating the degree of preference for r over c expressed as gcr = 1 – grc. Then, a fuzzy preference matrix was created. The following expression was used for this.

In this study, a 6 × 6 fuzzy preference matrix (G) was created as follows: G = [gcr]Z×z.

The preference intensity (μj) of each individual criterion was obtained using the following equation. The μj value varied between 0 and 1.

2.4 Conditional valuation and lower-bound average methods

The conditional valuation method was applied in this study to determine consumers' willingness to pay for cultured beef. In this method, a hypothetical market is created for any goods or services that cannot be bought and sold on the market, the benefits of the goods or services in question are explained to the participants, and the amount of money that they are willing to pay in return for these benefits is learned. The participants consumed beef; however, they had never tasted cultured beef. The product does not yet have a market. Therefore, this method was deemed appropriate. The sample for this portion of the research consisted of participants who stated that they might consume the product if the price of cultured beef was lower (n = 113).

These consumers were asked, “How much cheaper would you be willing to buy artificial meat (cultured beef) than beef?” They were requested to answer with a percentage (%). The figures obtained from each consumer were used to determine the general purchase intention using the method given below Blaine et al. (2003).

where Π0 is the cumulative purchase intention, P0 is the lowest bound of the prices that the consumers suggested and K is the number of bounds.

3 Results

3.1 Description of this study's population

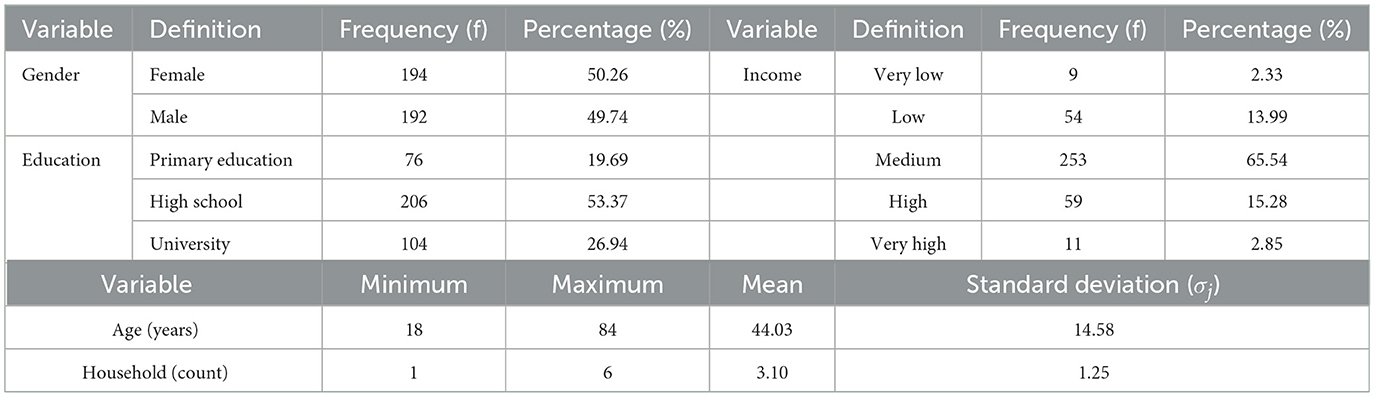

Table 1 presents various demographic data for the survey participants, such as their gender, age and education and income levels. A total of 50.26% of the survey participants were female; 49.74% were male. When their level of education was examined, it was observed that the majority were high school graduates, followed by university and primary school graduates. Their ages ranged from 18 to 84, with an average age of approximately 44. The average household size was 3.10, and the vast majority of participants defined their income as medium. The demographic data of the participants were consistent with the sociological structure of Izmir Province.

3.2 Sensory factors in traditional beef consumption

In this study, the Critic method was used to weight the sensory criteria affecting the participants' beef consumption preferences. Consumers' sensory expectations of real beef can also guide the development of cultured beef. Because they had never tasted cultured beef before, their opinions of standard beef were used. Having similar sensory properties to conventional meat has generally emerged as a determinant of consumer acceptance in previous studies (To et al., 2024).

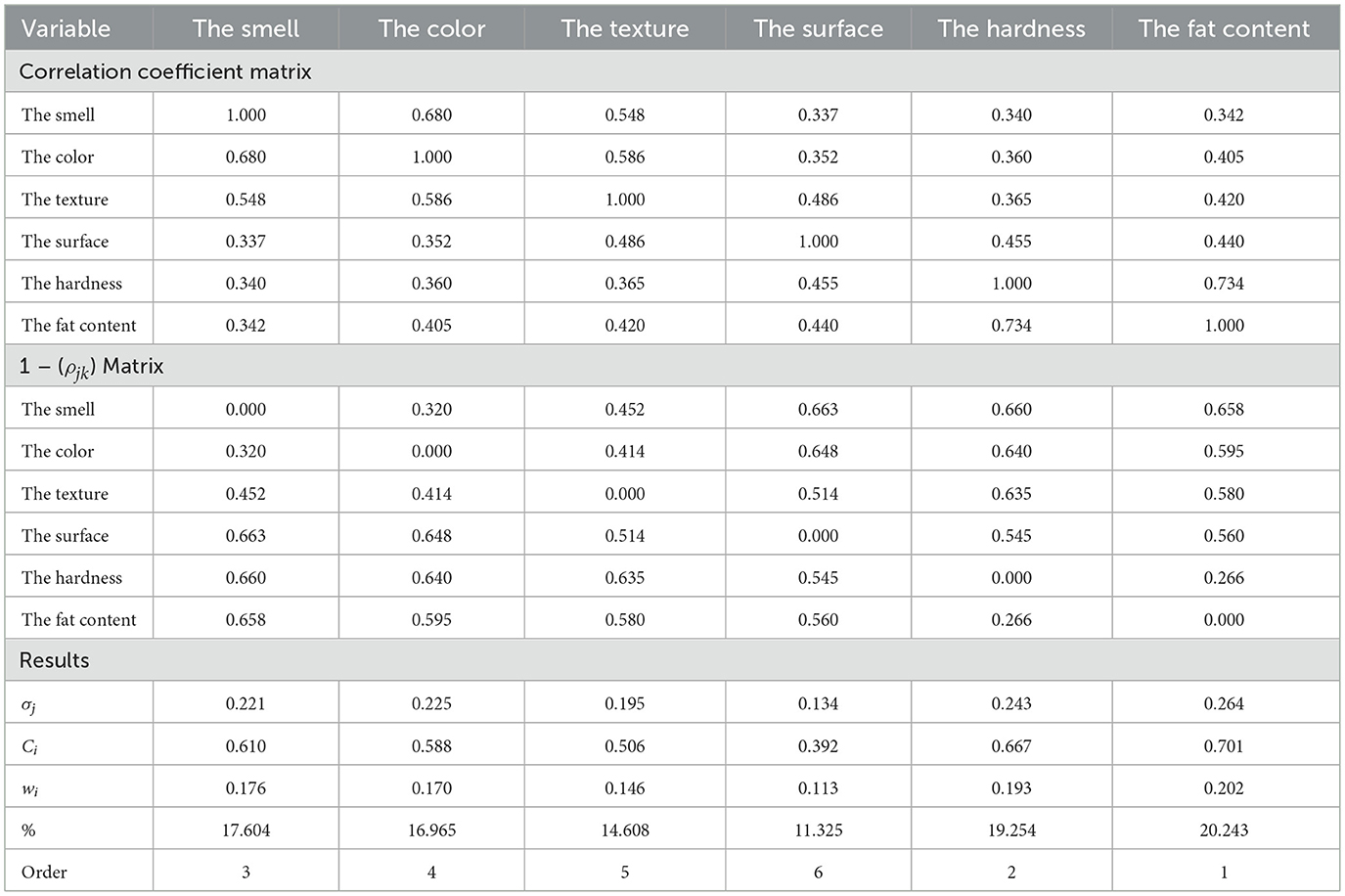

Six sensory attributes were selected based on literature. A data set was created for a total of 6 different sensory criteria that may affect beef consumption preferences, and the findings obtained using this method are presented in Table 2. With this method, correlation and importance ranking between data are obtained. The correlation between the smell and the color, the hardness and the fat content is high for consumers. The importance levels of the criteria were calculated as percentages using the standard deviation values. Accordingly, the fat content had an importance of 20.243%, the hardness had 19.254%, the smell had 17.604%, the color had 16.965%, the texture had 14.608% and the surface appearance had 11.325% regarding beef consumption.

3.3 Expected features of cultured beef

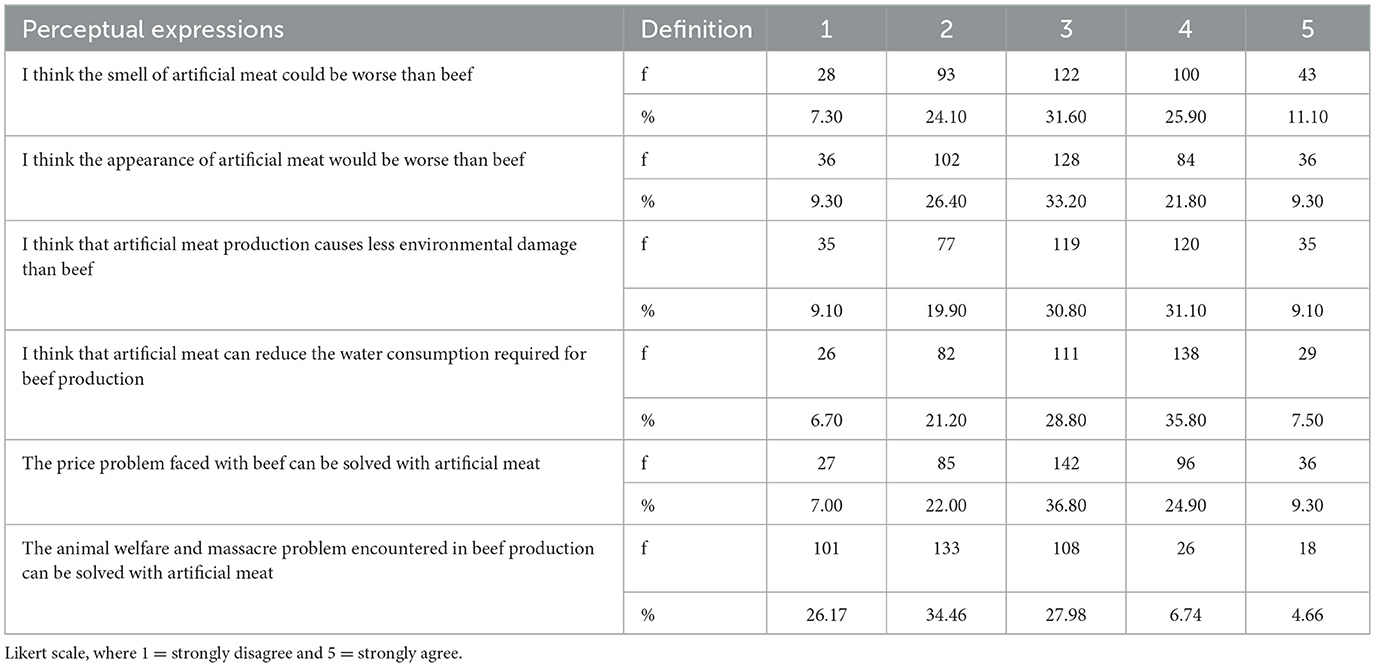

The participants' general attitudes regarding cultured beef are presented in Table 3. A significant proportion of the participants thought that cultured beef production would cause less damage to the environment and reduce water consumption compared to beef production.

However, there is a widespread view in Türkiye that cultured beef cannot solve the animal welfare problems encountered in beef production and that massacre problems cannot be overcome. The reason for this may be the religious holiday celebrated by Muslims once a year with the sacrifice of an animal. Consumers' attitudes toward social problems were similar to Arabs (Chriki et al., 2024). On the other hand, a significant portion shows an ambiguous judgment about the smell and appearance of cultured beef compared to that of beef. Agreement with the idea that beef would be a solution to the price problem was uncertain.

In general, the consumers' attitudes toward the product were complex. The main reason for their hesitation may be that they have not purchased or consumed cultured beef before.

3.4 Attitudes that increase the desire to try cultured beef

All the consumers participating in the survey were first given a brief definition of artificial meat (cultured beef) and information on how it is obtained. In this part of the survey, the consumers were asked whether they wanted to consume artificial meat (cultured beef). A total of 32 participants stated that they would consume cultured beef, and 354 people stated that they would not want to. When considered proportionally, 8.29% of the participants would consume cultured beef and 91.71% would not. Similarly, it is stated that the acceptance level of animal cell culture meat, especially among Chinese consumers, is low (Pareti et al., 2025).

We tried to determine whether unfamiliarity with this food affected the consumers' choice to consume cultured beef. For this purpose, the food neophobia scale developed by Pliner and Hobden (1992) was used. Food Neophobia can be defined as the reluctance to eat unfamiliar foods. The Cronbach's Alpha coefficient used to test the scale's reliability for the survey conducted was 75.1. As the scale score increased, the consumer's tendency toward food neophobia increased.

The average food neophobia scale score for the 32 people (8.29%) who stated that they would consume cultured beef was 31.72, while for the 354 people (91.71%) who would not, it was 39.24. There was a statistical difference between these two groups (p < 0.01). It can be stated that the group who did not want to consume cultured beef exhibited greater food neophobia than the group who were open to eating it.

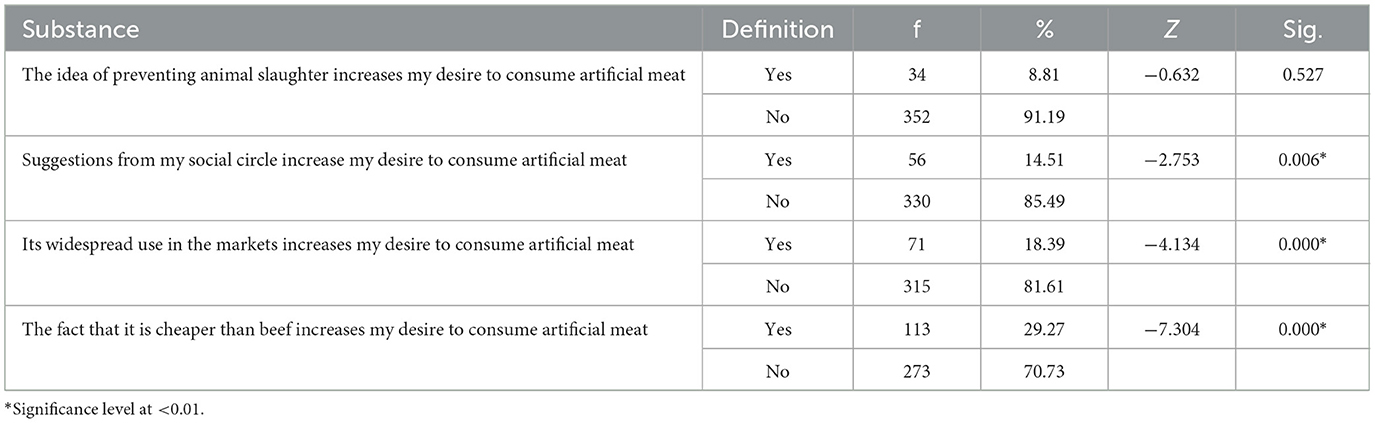

We examined whether there was a change in cultured beef consumption preferences when survey participants were presented with different statements. The first group was formed by 32 people who wanted to consume cultured beef. This group formed the reference for statistical comparisons in the following stages of the research. There have been changes in the desire to consume with new propositions. It was examined whether there was a statistical difference between the first group and the other groups (Table 4).

Table 4. External factors affecting consumers' attitudes toward artificial meat (cultured beef) consumption.

The statements were as follows (listed according to their level of significance):

• The idea of preventing animal slaughter increases my desire to consume artificial meat.

In this case, 34 participants stated that they would consume artificial meat, and 352 people stated that they would not want to. When examined as a percentage, 8.81% of the participants would consume artificial meat, while 91.19% would not. No statistically significant difference was found compared to the first situation (p > 0.01).

• Suggestions from my social circle increase my desire to consume artificial meat.

In this case, 56 participants stated that they would consume artificial meat, while 330 people stated that they would not want to. When examined proportionally, 14.51% of the participants would consume artificial meat, while 85.49% would not. A statistically significant difference was found compared to the first situation (p < 0.01).

• Its widespread use in the markets increases my desire to consume artificial meat.

In this case, 71 participants stated that they would consume artificial meat, while 315 people stated that they would not want to. When examined in terms of percentages, 18.39% of the participants would consume artificial meat, while 81.61% would not. A statistically significant difference was found compared to the first situation (p < 0.01).

• The fact that it is cheaper than beef increases my desire to consume artificial meat.

In this case, 113 participants stated that they would consume artificial meat, while 273 people stated that they would not want to. When examined in percentage terms, 29.27% of the participants would consume artificial meat, while 70.73% would not. A statistically significant difference was found compared to the first situation (p < 0.01).

According to Jacobs et al. (2024), the perception that artificial meat is environmentally friendly in Germany increases motivation. Similarly, animal welfare appears to be important to German consumers (Weinrich et al., 2020). Animal welfare and environmental protection are not a motivation for increased consumption of the product in Türkiye.

As the product becomes more widespread, consumption motivation increases. This finding is consistent with studies demonstrating a positive relationship between familiarity and consumption (Mancini and Antonioli, 2019; Wang and Scrimgeour, 2023).

Similarly, it is consistent with studies showing that lower prices increase motivation toward the product (Verbeke et al., 2015; Gómez-Luciano et al., 2019).

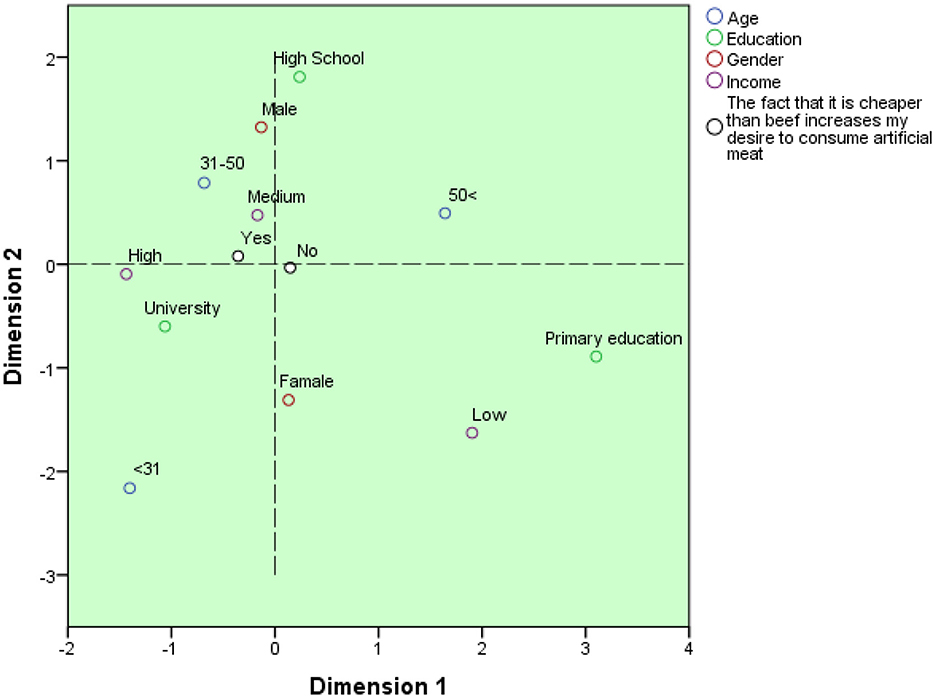

In this part of the research, multiple correspondence analysis was conducted to determine the demographic characteristics of the groups that said yes and no to the statement “The fact that it is cheaper than beef increases my desire to consume artificial meat.” This method was preferred because it allows visual interpretation of relationships between categorical variables. The findings are presented in Figure 1. The variance explanatory power of the first dimension is 29.955%, and the variance explanatory power of the second dimension is 24.209%. The eigenvalue for the first dimension is 1.498 and for the second dimension is 1.210. The dimensions are divided into four parts: the positive and negative areas of the first dimension and the positive and negative areas of the second dimension. According to the first dimension, if the price is low, those who want to buy are in the negative zone, while those who say no are in the other zone. Related categories are located in the same region. Accordingly, it is seen that consumers who want to buy the product when its price decreases are predominantly male, middle-income and middle-aged (31–50 years old).

Figure 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and purchase intention (multiple correspondence analysis).

3.5 Sensory barriers to cultured beef consumption

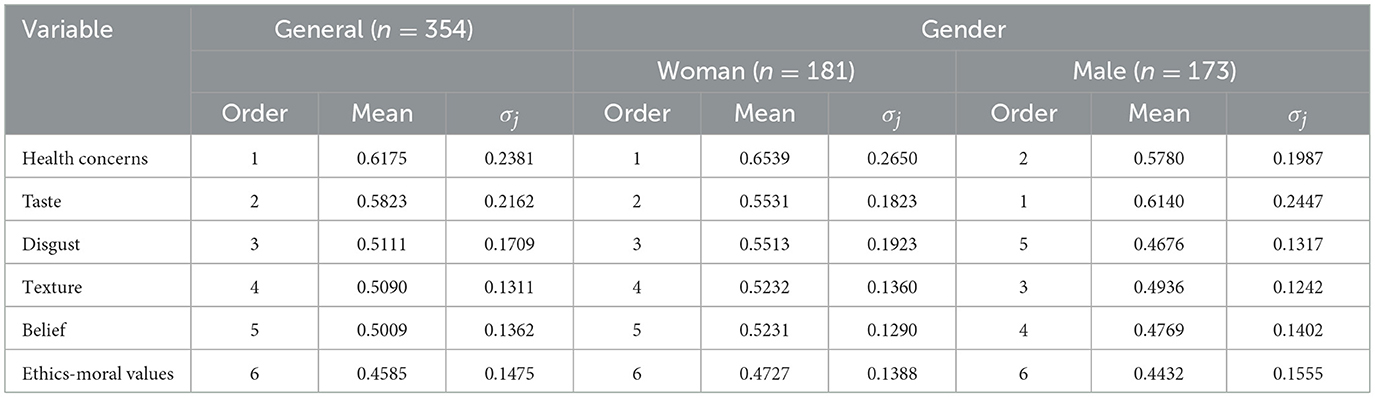

While 32 participants were inclined to consume cultured beef, 354 people were not. In this part of the survey, the fuzzy pairwise comparison method was used to evaluate the reasons why these 354 people did not want to consume cultured beef. A total of six criteria selected using previous consumer research were presented to the survey participants to determine these reasons, and pairwise comparisons were requested. The six criteria were disgust, expectations regarding the taste and texture of the cultured beef, health concerns, beliefs, and ethical and moral values. Fifteen comparisons were made for these six criteria.

The means obtained from the comparison were ranked from the largest to the smallest according to their weights, i.e., their importance levels (Table 5). The most important reason why the consumers did not want to consume cultured beef was health concerns, followed by their expectation of its taste and feelings of disgust, respectively. Their expectation of cultured beef's texture and beliefs were in fourth and fifth place, while ethical and moral values were in last place. When the rankings were examined according to the participants' gender, it was seen that the rankings differed in males. A total of 181 female consumers and 173 male consumers did not want to consume cultured beef. The most important reason why men did not want to was their expectation of its taste. Health concerns were in second place, their expectation of cultured beef's texture was in third place, and their beliefs were in fourth place. Feelings of disgust and ethical–moral values were in the last two places. One of the biggest obstacles to consumers accepting cultured beef is the perception that it is unhealthy and unnatural (Siegrist and Sütterlin, 2017; Siegrist et al., 2018; Siegrist and Hartmann, 2020). Consumers see the product as unhealthy because it is not natural. The findings support this emotional barrier. Especially in women, the feeling of disgust arises after the perception of being unhealthy. This stands out as a separate sensory barrier for female consumers.

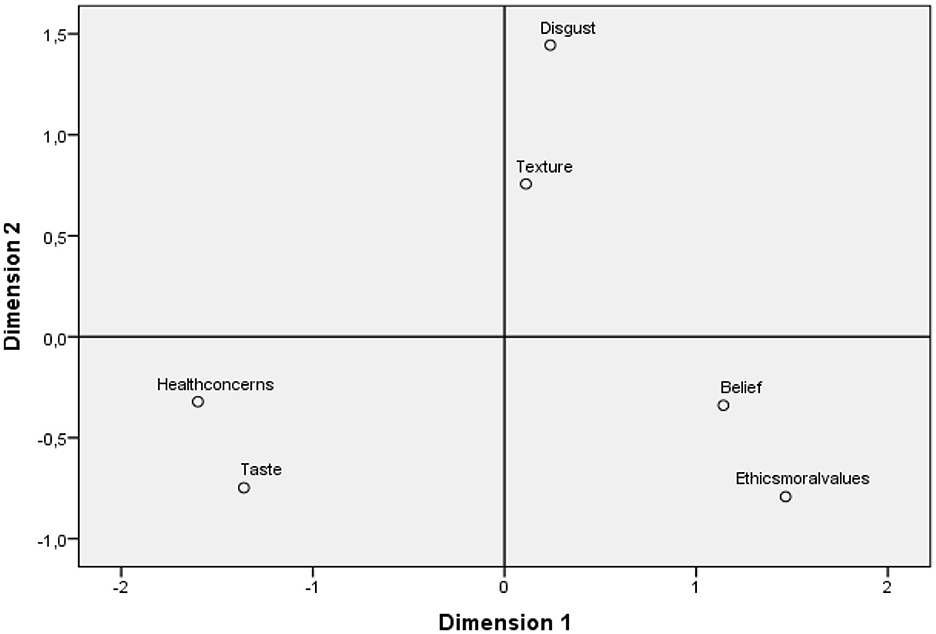

In this study, a perceptual map was created for the reasons for not consuming cultured beef. Multidimensional scaling analysis was used for this purpose. The perception map of those who do not consume cultured meat is presented in Figure 2. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is a powerful tool for visualizing similarities and differences between objects. The multidimensional scaling stress value was found to be 0.01902, and the R2 value was 0.99744. The data distances and representation distances were fully consistent, and the findings were interpretable.

Figure 2 shows the perceptual maps of consumer cultured beef generated from fuzzy paired comparison data. Accordingly, consumers' perceptions of the similarities and differences regarding the reasons for not consuming the product were determined. According to the positioning matrix findings, the first sensory reasons perceived as close to each other were beliefs and ethical/moral concerns, with a matrix distance of 0.557. The second reason was health concerns and taste, with a matrix distance of 0.603. The third reason was disgust and the texture perception of cultured meat, with a matrix distance of 0.603. The most distant perceptions are between ethical and moral values and health concerns (matrix value 3.103), taste (matrix value 2.827), disgust (matrix value 2.545), and the texture of cultured meat (matrix value 2.062). Similar distances were found between beliefs and other sensory factors.

These distances indicate that beliefs, ethical and moral values are perceived as close to each other, while their relationship with other sensory factors is perceived as quite different.

3.6 Willingness to pay for cultured beef

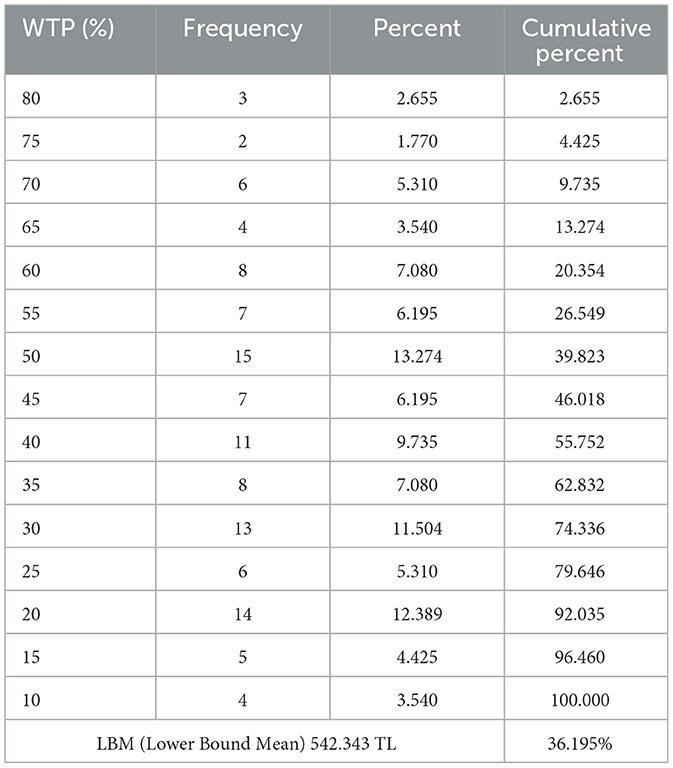

A total of 29.27% people responded positively to the statement “Being cheaper than beef increases my desire to consume artificial meat (cultured beef).” This group was asked, “How much cheaper would you buy artificial meat (cultured beef) than beef?” Consumers were asked to express their responses as a percentage.

Consumers were willing to pay anywhere from 10 to 80% less than the price of beef per kilogram. These rates were converted to the general purchase intention using the lower-bound mean (LBM) method.

As a result of this method, it was revealed that consumers were willing to pay an average of 36.195% less for cultured beef than for conventional beef. The price of conventional beef is 850 TL per kg. The approximate price per kg in US dollars is USD 21.497. The approximate price per kg in US dollars is $21.497. The findings suggest that if cultured beef is 36.195% cheaper than conventional beef, there could be a potentially significant increase in purchase intention (Table 6). In other words, the price that the consumers were willing to pay (WTP) for this product was 36.195% cheaper than the price of beef. Therefore, the consumers expected the price of cultured beef to be TRY 542.343. The price per kg in US dollars was approximately USD 13.716.

4 Discussion and conclusions

This research was conducted to investigate the attitudes of consumers toward the consumption of cultured beef as an alternative protein product and revealed important results. This research provides novel results on the potential acceptance of cultured beef in Türkiye.

The price was an important factor in Turkish consumers' willingness to accept cultured beef. A total of 29.27% of the respondents were inclined to consume cultured beef if it cost less than beef. The importance of cultured meat's price has been emphasized in various studies. For example, it was found that Greek, Croatian and Spanish consumers would buy cultured meat if it was sold at a reasonable price (Franceković et al., 2021). There are other studies that emphasize the importance of price (Gómez-Luciano et al., 2019; Chriki et al., 2021).

Red meat is known to be relatively expensive in Türkiye. Even in European Union countries where the national income per capita is much higher than Türkiye's, the average price of beef is close to that in Türkiye. That's why annual beef consumption is quite low. Beef has ceased to be a staple food and has become inaccessible to large segments of society.

In many different countries, consumers were willing to pay less for cultured meat than for real meat (Chriki et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Kombolo Ngah et al., 2023). These results were confirmed.

The findings suggest that if cultured beef is 36.195% cheaper than conventional beef, there could be a potentially significant increase in purchase intention. In other words, the price that the consumers were willing to pay (WTP) for this product was 36.195% cheaper than the price of conventional beef. Moreover, in this research, we found that Turkish consumers expected a price of 542.343 TL for cultured beef. The price per kg in US dollars was approximately USD 13.716. The rates given by individual consumers were converted into general rates using the lower bound average method. Consumers' average price expectation for cultured beef is 36.195% lower than standard beef.

Motivation to consume increases at low prices. This data confirms previous studies that found that a lower price can significantly increase consumers' willingness to accept cultured meat (Verbeke et al., 2015; Gómez-Luciano et al., 2019). Some studies have found that consumers are less willing to pay higher prices (Rolland et al., 2020; Van Loo et al., 2020).

A second important result obtained in this research was the change in the participants' willingness to consume cultured meat when presented with various statements. Limiting animal suffering and the environmental impact of meat consumption were among the main motivations for Polish consumers' acceptance of cultured meat (Sikora and Rzymski, 2023). Similarly, for French consumers, the main drivers of acceptance are ethical and environmental concerns (Hocquette et al., 2022). According to Van Loo et al., 2020, environmental and technical information provided to American consumers may affect their preference for cultured meat to a certain extent. This issue is also important for German consumers (Weinrich et al., 2020).

However, in Türkiye, ending the slaughter of animals were not significant factors determining consumer acceptance. Unlike developed countries, it is possible to observe an attitude. This may be expected, as Türkiye has a religious holiday where cattle and sheep are sacrificed once a year. Chinese consumers are less likely to consume cultured meat. The main reason for this is not ethical or environmental issues but emotional factors related to its unnaturalness (Liu et al., 2021). While price reductions in Türkiye provide motivation, the perception of the product as unhealthy and tasteless creates a barrier. The trends of Chinese consumers are similar to those of Turks (Liu et al., 2021).

Another important result of the research concerns familiarity. The food neophobia scale scores of the group that tended to accept the product without tasting it at the first stage were different from the other group. It can be said that the tendency to accept the product faster is in individuals who are more prone to consuming new foods. Studies have shown that emotional biases such as unfamiliarity cause significant resistance from consumers (Yu et al., 2025; Siddiqui et al., 2022b; Wilks et al., 2019). In this study, it is observed that there is resistance to this situation.

Positive information about cultured meat increases consumers' interest in the product (Van Loo et al., 2020; Min et al., 2024). Similarly, easy access to cultured meat products has increased acceptance among German consumers (Dupont et al., 2022). In this study, the tendency to consume has changed positively in various propositions that can increase familiarity. For example, recommendations from others in their social circles and the prevalence of products on the market positively influenced participants' willingness to purchase cultured meat.

Finally, another important result was related to sensory factors. It can be said that one of the biggest obstacles to acceptance is the perception of health. The product is artificial and developed in a laboratory environment. Therefore, it is quite normal for consumers to think that the product may have a negative effect on their health and not want to consume it. On the other hand, as in other studies, health anxiety emerged as one of the most important factors affecting consumer acceptance (Gousset et al., 2022). In particular, the artificial nature of this product runs counter to the increasing demand for natural products in many countries (Chriki et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Min et al., 2024). Ensuring trust in the product is one of the important motivations for consumers to accept the product. The product's features, naming and the context in which it will be introduced must be chosen correctly (Melios et al., 2025). As Weinrich (2018) noted, cultured meat messages focusing on antibiotics and food safety can increase interest in the product.

Disgust and taste perception were also important factors for Turkish consumers in not accepting artificial cultured meat products. For women, disgust was one of the biggest obstacles to acceptance compared to male. Other research, sensory factors such as cultured meat's aroma, texture, taste and appearance, as well as feelings of disgust associated with these, were also shown to be important factors limiting acceptance (Siegrist and Hartmann, 2020; Boereboom et al., 2022; Pakseresht et al., 2022; Deliza et al., 2023).

This research has provided some tips for success for entrepreneurs who will commercialize the product.

Generally speaking, even if cultured meat is sustainable, the consumer's perception seems to be different. In the first stage, the consumer profile that wants to buy a product when its price drops is composed of male, middle-income and middle-aged people. Therefore, this group can be selected as the target audience.

In the second stage, the target audience can be selected as those who enjoy novel food consumption. Product labeling features should be prioritized for this group. The social environment has been observed to have a positive impact on product acceptability. Therefore, the use of social media networks in marketing channels is recommended.

Behind, mentioning the product's name differently and making the right promotions that it is a sustainable product can change the interest in the product. In addition, the right pricing policy, mass production and a taste close to traditional meat can easily make consumers adopt this product. Furthermore, increased accessibility, increased applicability, commercial availability, advertising strategies, and taste testing will lead to greater adoption of cultured meat in the future.

This research provides novel results on the potential acceptance of cultured meat in Türkiye. The entry of this product into the market of a developing country is especially important for the rapid expansion of the market in the region. As Escobar et al. (2025) noted, a targeted marketing strategy is needed to popularize cultured meat globally. These results are very important for companies and other interested organizations aiming to enter the Türkiye cultured meat market in the future.

4.1 Limitations

This research has several limitations. First, it assesses attitudes in a hypothetical market setting. In Türkiye, cultured meat is produced in its plant-based form. However, cultured meat is not produced in a laboratory setting from cells taken from live cattle. Therefore, cell cultured meat production is not yet a licensed, commercialized, or supported activity in Türkiye. Because cultured meat is currently not accessible to most consumers, it is not possible to measure consumer reactions to cultured meat in terms of actual purchasing behavior. Therefore, consumer attitudes were assessed using a hypothetical market. Therefore, consumer attitudes can only indicate intention. While consumer behavior is related to intention at the purchase stage, it can also differ. This research provides the basis for evaluating actual consumer behavior in the event that cultured beef becomes widespread in the future.

Secondly, the consumer group is limited to a certain scope. The research was conducted with a sample of Turkish consumers. Similarly, the study was conducted in a specific region of the country. While care was taken to create data that was as closely representative of the general population as possible in terms of socio-demographic characteristics such as gender and age, the possibility of sampling bias cannot be excluded.

Perceptions of cultured meat are likely to continue to change as it approaches commercialization. Therefore, more research measuring consumer behavior in this area is needed. Future research could aim to test behavioral economics-based approaches that present different choice environments.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethics committee approval was obtained from Aydin Adnan Menderes University Social and Human Sciences Research Ethics Committee with the decision number 31906847/050.04.04-08-300. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GC: Methodology, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SB: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Resources, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alonso, M. E., González-Montaña, J. R., and Lomillos, J. M. (2020). Consumers' concerns and perceptions of farm animal welfare. Animals 10:385. doi: 10.3390/ani10030385

Bellarby, J., Tirado, R., Leip, A., Weiss, F., Lesschen, J. P., and Smith, P. (2013). Livestock greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential in Europe. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02786.x

Bhat, Z. F., Kumar, S., and Bhat, H. F. (2017). In vitro meat: a future animal-free harvest. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 782–789. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.924899

Biscarra-Bellio, J. C., De Oliveira, G. B., Marques, M. C., and Molento, C. F. (2023). Demand changes meat as changing meat reshapes demand: the great meat revolution. Meat Sci. 196:109040. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.109040

Blaine, W. T., Lichtkoppler, F. R., and Standbro, R. (2003). An assessment of residents' willingness to pay for green space and farmland preservation conservation easements using the contingent valuation method (CVM). J. Ext. 41, 1–4

Boender, C. G. E., De Graan, J. G., and Lootsma, F. (1989). Multi-criteria decision analysis with fuzzy pairwise comparisons. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 29, 133–143. doi: 10.1016/0165-0114(89)90187-5

Boereboom, A., Mongondry, P., De Aguiar, L. K., Urbano, B., Jiang, Z. V., De Koning, W., et al. (2022). Identifying consumer groups and their characteristics based on their willingness to engage with cultured meat: a comparison of four European countries. Foods 11:197. doi: 10.3390/foods11020197

Bryant, C., and Barnett, J. (2018). Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: a systematic review. Meat Sci. 143, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.008

Chriki, S., Alhujaili, A., Hallman, W. K., Payet, V., Ellies-Oury, M. P., and Hocquette, J. F. (2024). Attitudes toward artificial meat in Arab countries. J. Food Sci. 89, 9711–9731. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.17559

Chriki, S., Payet, V., Pflanzer, S. B., Ellies-Oury, M.-P., Liu, J., Hocquette, É., et al. (2021). Brazilian consumers' attitudes towards so-called “cell-based meat”. Foods 10:2588. doi: 10.3390/foods10112588

Deliza, R., Rodríguez, B., Reinoso-Carvalho, F., and Lucchese-Cheung, T. (2023). Cultured meat: a review on accepting challenges and upcoming possibilities. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 52:101050. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2023.101050

Diakoulaki, D., Mavrotas, G., and Papayannakis, L. (1995). Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems: the critic method. Comput. Oper. Res. 22, 763–770. doi: 10.1016/0305-0548(94)00059-H

Dupont, J., Harms, T., and Fiebelkorn, F. (2022). Acceptance of cultured meat in Germany—application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Foods 11:424. doi: 10.3390/foods11030424

Escobar, M. I. R., Han, S., Cadena, E., De Smet, S., and Hung, Y. (2025). Cross-cultural consumer acceptance of cultured meat: a comparative study in Belgium, Chile, and China. Food Qual. Prefer. 127:105454. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2025.105454

Fernandes, J., Blache, D., Maloney, S. K., Martin, G. B., Venus, B., Walker, F. R., et al. (2019). Addressing animal welfare through collaborative stakeholder networks. Agriculture 9:132. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9060132

Franceković, P., García-Torralba, L., Sakoulogeorga, E., Vučković, T., and Perez-Cueto, F. J. (2021). How do consumers perceive cultured meat in Croatia, Greece, and Spain? Nutrients 13:1284. doi: 10.3390/nu13041284

Gençer Bingöl, F., and Agagündüz, D. (2025). From tradition to the future: analyzing the factors shaping consumer acceptance of cultured meat using structural equation modeling. Food Sci. Nutr. 13:e70435. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.70435

Gómez-Luciano, C. A., De Aguiar, L. K., Vriesekoop, F., and Urbano, B. (2019). Consumers' willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Qual. Prefer. 78:103732. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103732

Gousset, C., Gregorio, E., Marais, B., Rusalen, A., Chriki, S., Hocquette, J. F., et al. (2022). Perception of cultured “meat” by French consumers according to their diet. Livest. Sci. 260:104909. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2022.104909

Grafton, R. Q., Daugbjerg, C., and Qureshi, M. E. (2015). Towards food security by 2050. Food Secur. 7, 179–183. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0445-x

Hocquette, É., Liu, J., Ellies-Oury, M. P., Chriki, S., and Hocquette, J. F. (2022). Does the future of meat in France depend on cultured muscle cells? Answers from different consumer segments. Meat Sci. 188:108776. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108776

Jacobs, A. K., Windhorst, H. W., Gickel, J., Chriki, S., Hocquette, J. F., and Ellies-Oury, M. P. (2024). German consumers' attitudes toward artificial meat. Front. Nutr. 11:1401715. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1401715

Kombolo Ngah, M., Chriki, S., Ellies-Oury, M. P., Liu, J., and Hocquette, J. F. (2023). Consumer perception of “artificial meat” in the educated young and urban population of Africa. Front. Nutr. 10:1127655. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1127655

Kozicka, M., Havlík, P., Valin, H., Wollenberg, E., Deppermann, A., Leclère, D., et al. (2023). Feeding climate and biodiversity goals with novel plant-based meat and milk alternatives. Nat. Commun. 14:5316. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40899-2

Lewisch, L., and Riefler, P. (2023). Cultured meat acceptance for global food security: a systematic literature review and future research directions. Agric. Food Econ. 11:48. doi: 10.1186/s40100-023-00287-2

Liu, J., Hocquette, É., Ellies-Oury, M. P., Chriki, S., and Hocquette, J.-F. (2021). Chinese consumers' attitudes and potential acceptance toward artificial meat. Foods 10:353. doi: 10.3390/foods10020353

Mancini, M. C., and Antonioli, F. (2019). Exploring consumers' attitude towards cultured meat in Italy. Meat Sci. 150, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.12.014

Mancini, M. C., and Antonioli, F. (2020). To what extent are consumers' perception and acceptance of alternative meat production systems affected by information? The case of cultured meat. Animals 10:656. doi: 10.3390/ani10040656

Melios, S., Gkatzionis, K., Liu, J., Ellies-Oury, M. P., Chriki, S., and Hocquette, J. F. (2025). Potential cultured meat consumers in Greece: attitudes, motives, and attributes shaping perceptions. Future Foods 11:100538. doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2025.100538

Min, S., Yang, M., and Qing, P. (2024). Consumer cognition and attitude towards artificial meat in China. Future Foods 9:100294. doi: 10.1016/j.fufo.2023.100294

Moritz, M. S., Verbruggen, S. E., and Post, M. J. (2015). Alternatives for large-scale production of cultured beef: a review. J. Integr. Agric. 14, 208–216. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60889-3

Newbold, P. (1995). Statistics for Business and Economics. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

Ozcan, H. N., and Çinar, G. (2024). Investigation of consumers' attitudes towards seaweeds and insects. Turk. J. Agric. Nat. Sci. 11, 311–320. doi: 10.30910/turkjans.1379287

Pakseresht, A., Kaliji, S. A., and Canavari, M. (2022). Review of factors affecting consumer acceptance of cultured meat. Appetite 170:105829. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105829

Pareti, M., Guo, J., Yin, J., Liu, Q., Abudurofu, N., Bulibuli, A., et al. (2025). Exploring Chinese consumers' perception and potential acceptance of cell-cultured meat and plant-based meat: a focus group study and content analysis. Foods 14:1446. doi: 10.3390/foods14091446

Pliner, P., and Hobden, K. (1992). Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 19, 105–120. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-W

Richter, B. D., Bartak, D., Caldwell, P., Davis, K. F., Debaere, P., Hoekstra, A. Y., et al. (2020). Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production. Nat. Sustain. 3, 319–328. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0483-z

Rolland, N. C. M., Markus, C. R., and Post, M. J. (2020). The effect of information content on acceptance of cultured meat in a tasting context. PLoS ONE 15:e0231176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231176

Siddiqui, S. A., Alvi, T., Sameen, A., Khan, S., Blinov, A. V., Nagdalian, A. A., et al. (2022a). Consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: a systematic review of current alternative protein sources and interventions adapted to increase their acceptability. Sustainability 14:15370. doi: 10.3390/su142215370

Siddiqui, S. A., Khan, S., Farooqi, M. Q. U., Singh, P., Fernando, I., and Nagdalian, A. (2022b). Consumer behavior towards cultured meat: a review since 2014. Appetite 179:106314. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106314

Siddiqui, S. A., Khan, S., Murid, M., Asif, Z., Oboturova, N. P., Nagdalian, A. A., et al. (2022c). Marketing strategies for cultured meat: a review. Appl. Sci. 12:8795. doi: 10.3390/app12178795

Siddiqui, S. A., Pandith, J. A., Yunusa, B. M., Ayivi, R. D., and Castro-Muñoz, R. (2025). A comparative assessment of the economic, technological, sustainability and ethical aspects of lab-grown beef and traditional beef. Food Rev. Int. 1–39. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2025.2491548

Siegrist, M., and Hartmann, C. (2020). Perceived naturalness, disgust, trust and food neophobia as predictors of cultured meat acceptance in ten countries. Appetite 155:104814. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104814

Siegrist, M., and Sütterlin, B. (2017). Importance of perceived naturalness for acceptance of food additives and cultured meat. Appetite 113, 320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.019

Siegrist, M., Sütterlin, B., and Hartmann, C. (2018). Perceived naturalness and evoked disgust influence acceptance of cultured meat. Meat Sci. 139, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.02.007

Sikora, D., and Rzymski, P. (2023). The heat about cultured meat in Poland: a cross-sectional acceptance study. Nutrients 15:4649. doi: 10.3390/nu15214649

To, K. V., Comer, C. C., O'Keefe, S. F., and Lahne, J. (2024). A taste of cell-cultured meat: a scoping review. Front. Nutr. 11:1332765. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1332765

Tsvakirai, C. Z. (2024). The valency of consumers' perceptions toward cultured meat: a review. Heliyon 10:e27649. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27649

Van Der Weele, C., and Tramper, J. (2014). Cultured meat: every village its own factory? Trends Biotechnol. 32, 294–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.04.009

Van Loo, E. J., Caputo, V., and Lusk, J. L. (2020). Consumer preferences for farm-raised meat, lab-grown meat, and plant-based meat alternatives: does information or brand matter? Food Policy 95:101931. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101931

Verbeke, W., Sans, P., and Van Loo, E. J. (2015). Challenges and prospects for consumer acceptance of cultured meat. J. Integr. Agric. 14, 285–294. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60884-4

Wang, H. H. (2022). The perspective of meat and meat-alternative consumption in China. Meat Sci. 194:108982. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108982

Wang, O., and Scrimgeour, F. (2023). Consumer segmentation and motives for choice of cultured meat in two Chinese cities: Shanghai and Chengdu. Br. Food J. 125, 396–414. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-09-2021-0987

Weinrich, R. (2018). Cross-cultural comparison between German, French and Dutch consumer preferences for meat substitutes. Sustainability 10:1819. doi: 10.3390/su10061819

Weinrich, R., Strack, M., and Neugebauer, F. (2020). Consumer acceptance of cultured meat in Germany. Meat Sci. 162:107924. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.107924

Whitton, C., Bogueva, D., Marinova, D., and Phillips, C. J. (2021). Are we approaching peak meat consumption? Analysis of meat consumption from 2000 to 2019 in 35 countries and its relationship to gross domestic product. Animals 11:3466. doi: 10.3390/ani11123466

Wilks, M., Phillips, C. J., Fielding, K., and Hornsey, M. J. (2019). Testing potential psychological predictors of attitudes towards cultured meat. Appetite 136, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.01.027

Keywords: artificial meat, beef, food choice motivations, in vitro meat, sustainable food, alternative protein, consumer attitudes and preferences, multi-criteria decision-making methods

Citation: Cinar G and Bozkiran Yilmaz S (2025) A new and sustainable alternative food product: willingness to pay for cultured beef. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1688117. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1688117

Received: 18 August 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025;

Accepted: 18 November 2025; Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Behzad Mosalla Nezhad, Tec de Monterrey, MexicoReviewed by:

Ramadas Sendhil, Pondicherry University, IndiaPavan Kumar, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, India

Copyright © 2025 Cinar and Bozkiran Yilmaz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gokhan Cinar, Z29raGFuLmNpbmFyQGFkdS5lZHUudHI=

Gokhan Cinar

Gokhan Cinar Sidika Bozkiran Yilmaz

Sidika Bozkiran Yilmaz